Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Drugs

2.3. Measurement of Nociceptive Activity

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistics

3. Results

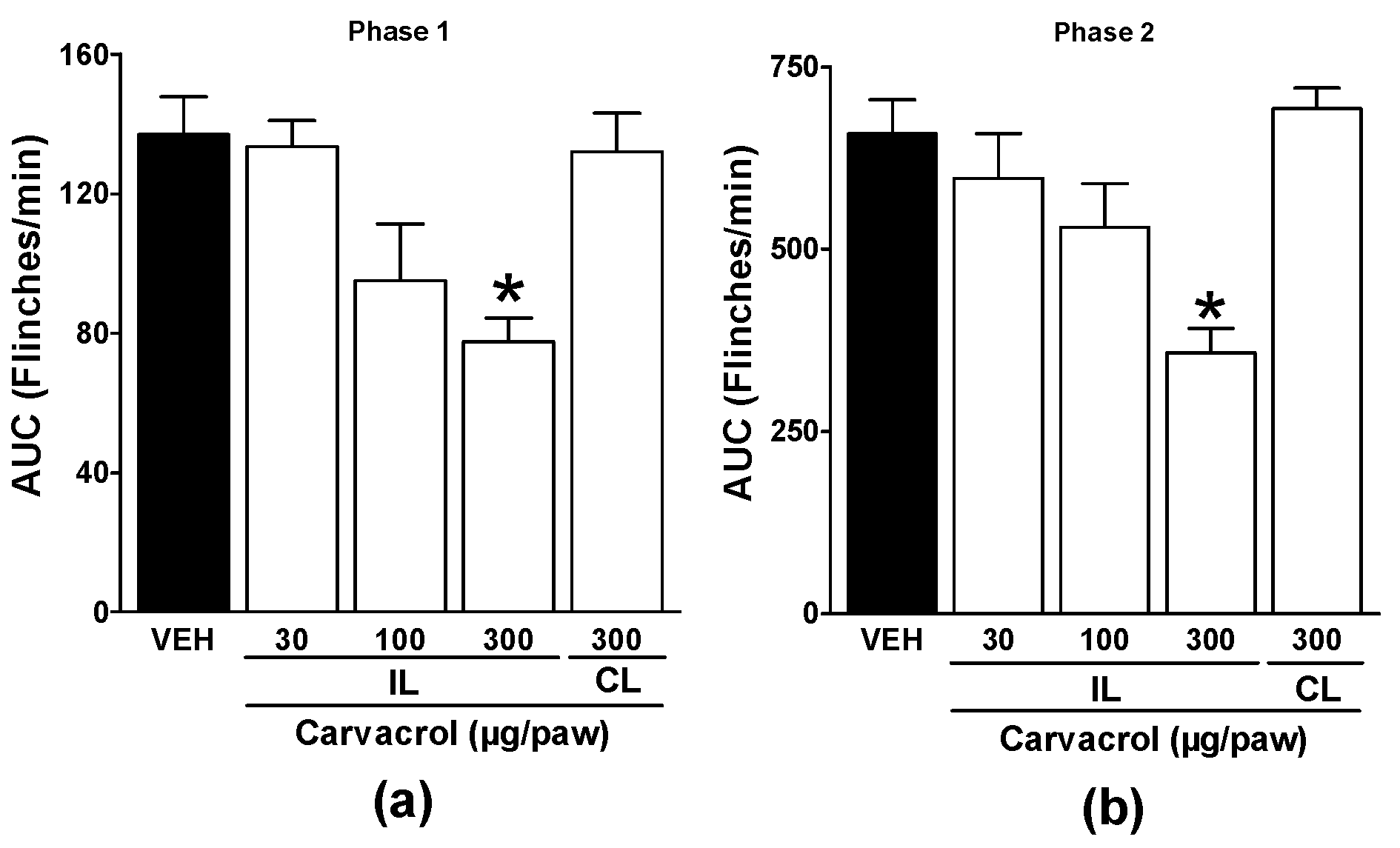

3.1. Antinociceptive Activity Produced by Carvacrol

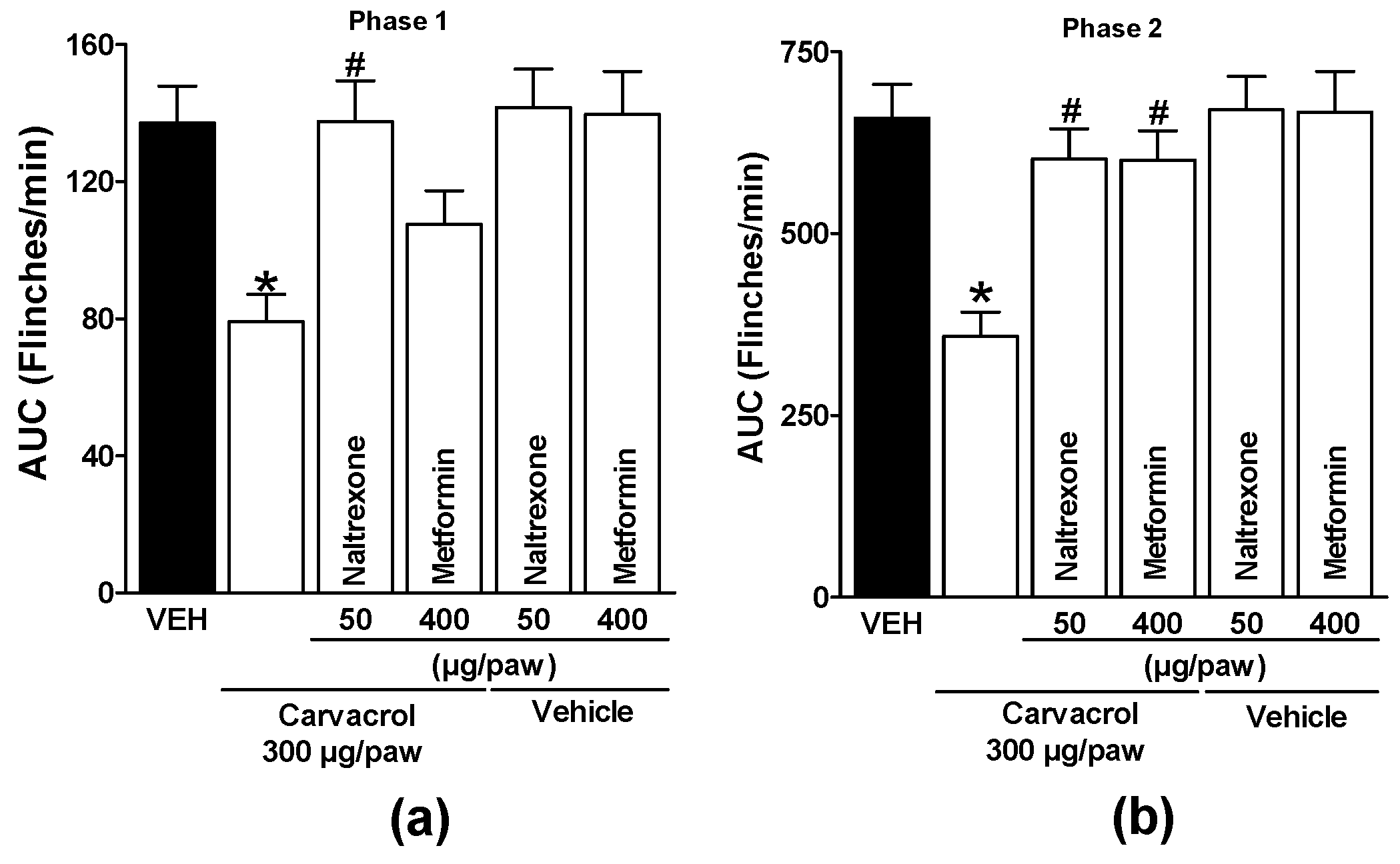

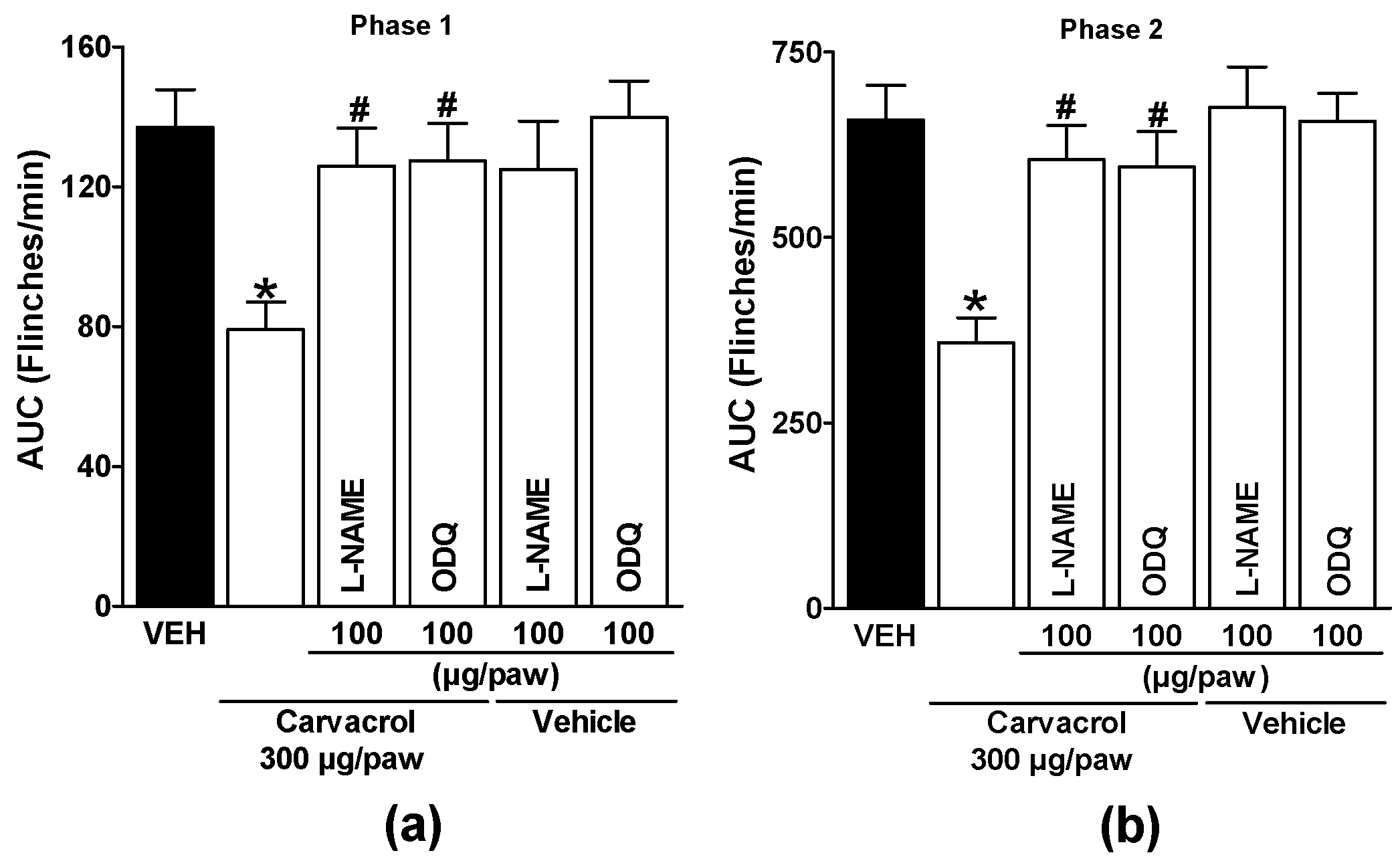

3.2. Effect of Naltrexone, Metformin, and NO-cGMP Pathway Inhibitors on Carvacrol Antinociception

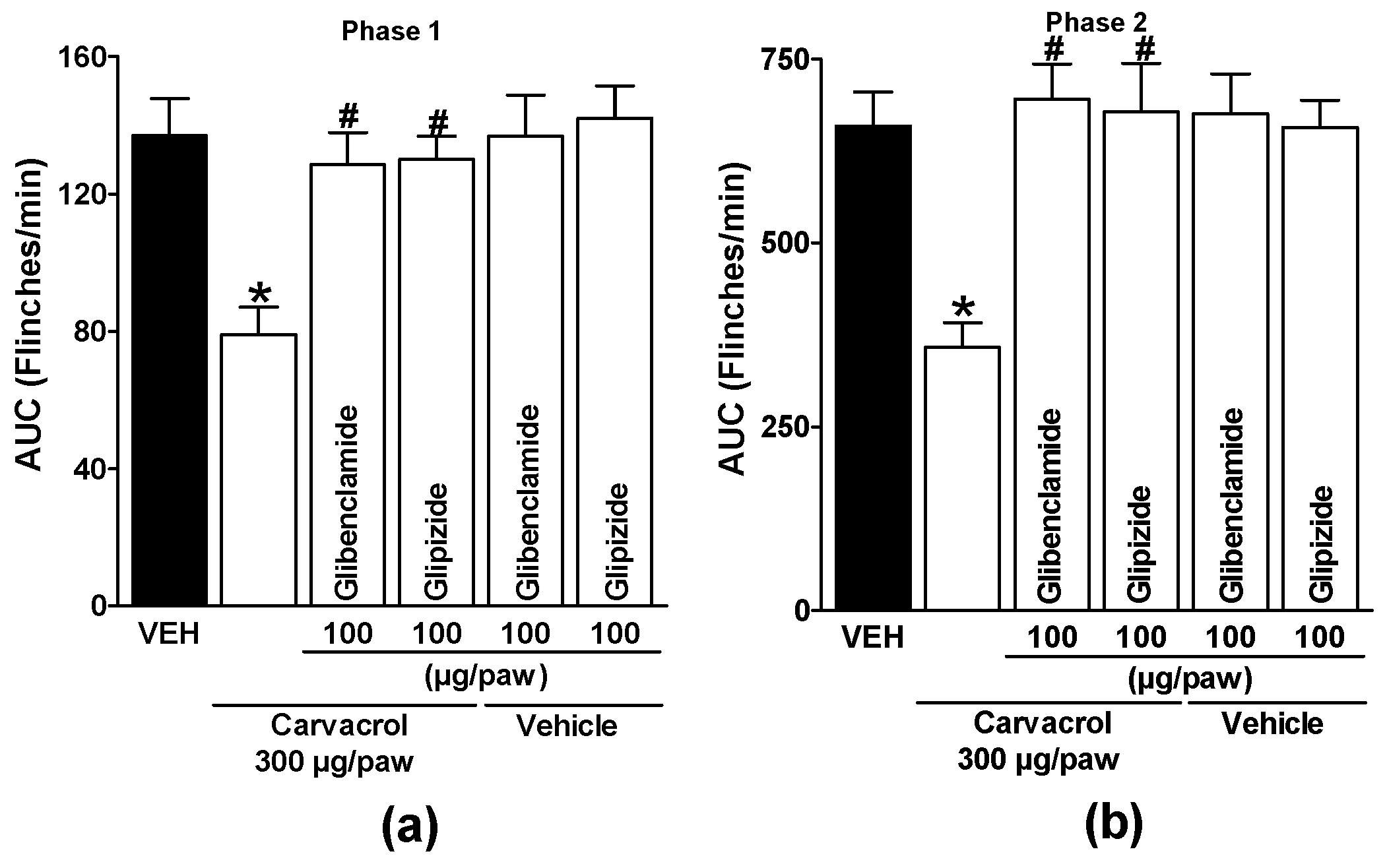

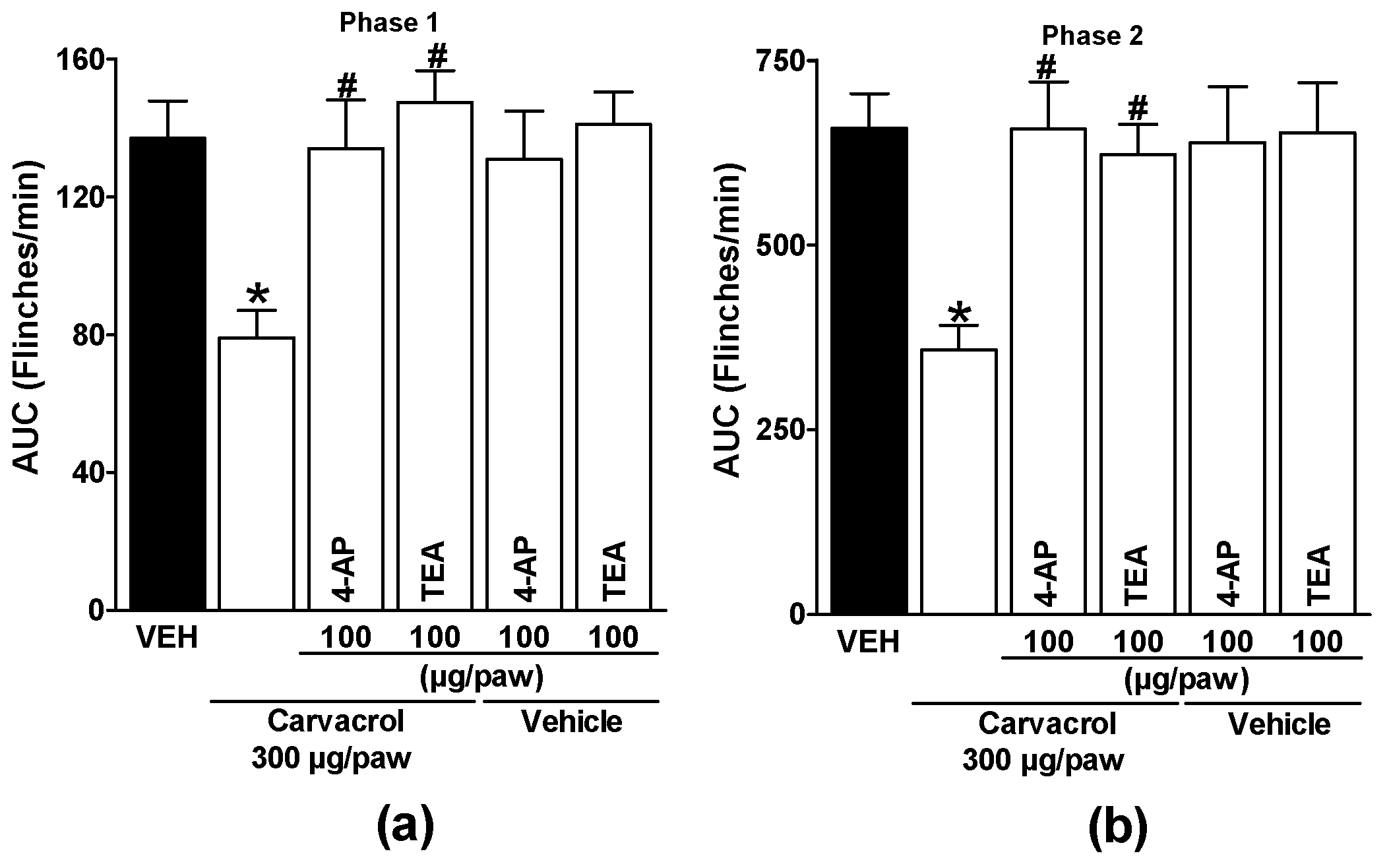

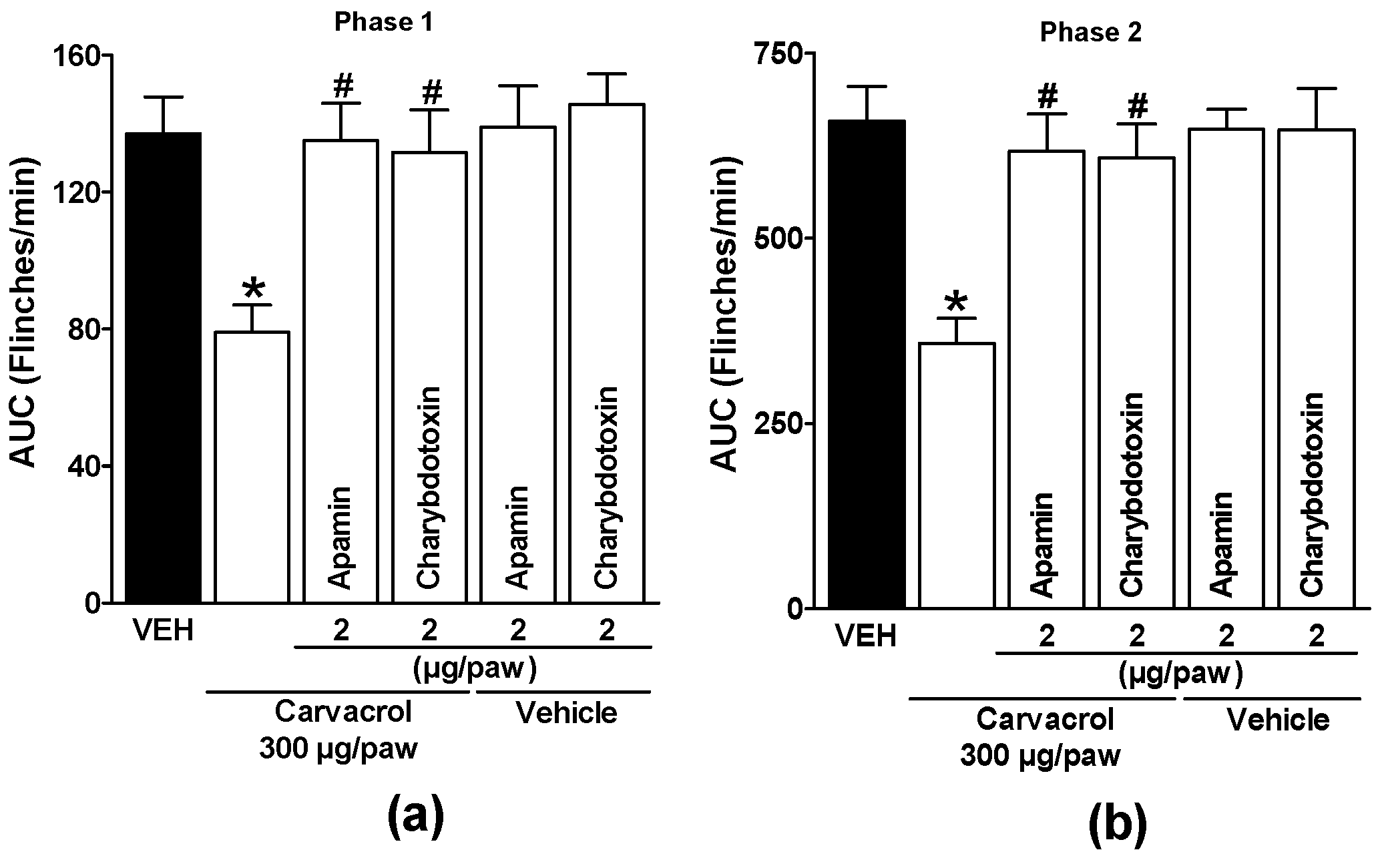

3.3. Effect of the Administration of K+ Channel Blockers on the Antinociception of Carvacrol

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| cGMP | Cyclic Guanosine monophosphate |

| CINVESTAV | Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional |

| CL | Contralateral |

| IL | Ipsilateral |

| IPN | Instituto Politécnico Nacional |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| L-NAME | NG-L-nitro-arginine methyl ester |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NOS | Nitric Oxide synthase |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| ODQ | 1 H-(1,2,4)-oxadiazolo (4,2-a) quinoxalin-1-one |

| PKG | Protein kinase |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| sGC | Soluble guanylate cyclase |

| TEA | Tetraethylammonium chloride |

| VEH | Vehicle |

| 4-AP | 4-aminopyridine |

References

- Imran, M.; Aslam, M.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Saeed, F.; Ahmad, I.; Afzaal, M.; Arshad, M.U.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Khames, A.; et al. Therapeutic application of carvacrol: A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3544–3561. [CrossRef]

- Suntres, Z.E.; Coccimiglio, J.; Alipour, M. The Bioactivity and Toxicological Actions of Carvacrol. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 55, 304–318. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, Z.; Majlessi, N.; Choopani, S.; Naghdi, N. Neuroprotective effects of carvacrol against Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases: A review. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2022, 12, 371–387. [CrossRef]

- Khazdair, M.R.; Ghorani, V.; Boskabady, M.H. Experimental and clinical evidence on the effect of carvacrol on respiratory, allergic, and immunologic disorders: A comprehensive review. BioFactors 2022, 48, 779–794. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.S.; da Silva, F.V.; Viana, A.F.; dos Santos, M.R.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Martins Mdo, C.; et al. Gastroprotective activity of carvacrol on experimentally induced gastric lesions in rodents. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2012, 385, 899-908.

- Balci, C,N.; Firat, T.; Acar, N.; Kukner, A. Carvacrol treatment opens Kir6.2 ATP-dependent potassium channels and prevents apoptosis on rat testis following ischemia-reperfusion injury model. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2021, 62, 179-190.

- Testai, L.; Chericoni, S.; Martelli, A.; Flamini, G.; Breschi, M.C.; Calderone, V. Voltage-operated potassium (Kv) channels contribute to endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation of carvacrol on rat aorta. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 68, 1177–1183. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, P.M.N.; Brito, M.C.; de Paiva, G.O.; dos Santos, C.O.; de Oliveira, L.M.; Ribeiro, L.A.d.A.; de Lima, J.T.; Lucchese, A.M.; Silva, F.S. Relaxant effect of Lippia origanoides essential oil in guinea-pig trachea smooth muscle involves potassium channels and soluble guanylyl cyclase. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 220, 16–25. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Delling, M.; Jun, J.C.; Clapham, D.E. Oregano, thyme and clove-derived flavors and skin sensitizers activate specific TRP channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 628–635. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.C.R.; Alves, A.d.M.H.; de Araújo, A.E.V.; Cruz, J.S.; Araújo, D.A.M. Distinct effects of carvone analogues on the isolated nerve of rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 645, 108–112. [CrossRef]

- Parnas, M.; Peters, M.; Dadon, D.; Lev, S.; Vertkin, I.; Slutsky, I.; Minke, B. Carvacrol is a novel inhibitor of Drosophila TRPL and mammalian TRPM7 channels. Cell Calcium 2009, 45, 300–309. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.G.; Namer, B.; Reeh, P.W.; Fischer, M.J. TRPA1 and TRPV1 Antagonists Do Not Inhibit Human Acidosis-Induced Pain. J. Pain 2017, 18, 526–534. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.-T.; Fujita, T.; Jiang, C.-Y.; Kumamoto, E. Carvacrol presynaptically enhances spontaneous excitatory transmission and produces outward current in adult rat spinal substantia gelatinosa neurons. Brain Res. 2014, 1592, 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Joca, H.C.; Vieira, D.C.O.; Vasconcelos, A.P.; Araújo, D.A.M.; Cruz, J.S. Carvacrol modulates voltage-gated sodium channels kinetics in dorsal root ganglia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 756, 22–29. [CrossRef]

- Lozon, Y.; Sultan, A.; Lansdell, S.J.; Prytkova, T.; Sadek, B.; Yang, K.-H.S.; Howarth, F.C.; Millar, N.S.; Oz, M. Inhibition of human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by cyclic monoterpene carveol. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 776, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pérez, V.M.; Ortiz, M.I.; Gerardo-Muñoz, L.S.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Salas-Casas, A. Tocolytic Effect of the Monoterpenic Phenol Isomer, Carvacrol, on the Pregnant Rat Uterus. Chin. J. Physiol. 2020, 63, 204–210. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.G.; Oliveira, G.F.; Melo, M.S.; Cavalcanti, S.C.; Antoniolli, A.R.; Bonjardim, L.R.; Silva, F.A.; Santos, J.P.A.; Rocha, R.F.; Moreira, J.C.F.; et al. Bioassay-guided Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antinociceptive Activities of Carvacrol. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 107, 949–957. [CrossRef]

- Melo, F.H.C.; Rios, E.R.V.; Rocha, N.F.M.; Citó, M.D.C.d.O.; Fernandes, M.L.; de Sousa, D.P.; de Vasconcelos, S.M.M.; de Sousa, F.C.F. Antinociceptive activity of carvacrol (5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol) in mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 1722–1729. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.S.; Llanes, L.C.; Nunes, R.J.; Nucci-Martins, C.; de Souza, A.S.; Palomino-Salcedo, D.L.; Dávila-Rodríguez, M.J.; Ferreira, L.L.G.; Santos, A.R.S.; Andricopulo, A.D. Antioxidant Activity, Molecular Docking, Quantum Studies and In Vivo Antinociceptive Activity of Sulfonamides Derived From Carvacrol. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Abed, D.Z.; Sadeghian, R.; Mohammadi, S.; Akram, M. Thymus persicus (Ronniger ex Rech. f.) Jalas alleviates nociceptive and neuropathic pain behavior in mice: Multiple mechanisms of action. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 283, 114695. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadifard, F.; Alimohammadi, S. Chemical Composition and Role of Opioidergic System in Antinociceptive Effect of Ziziphora Clinopodioides Essential Oil. Basic Clin. Neurosci. J. 2018, 9, 357–365. [CrossRef]

- Alizamani, E.; Ghorbanzadeh, B.; Naserzadeh, R.; Mansouri, M.T. Montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist, exerts local antinociception in animal model of pain through the L-arginine/nitric oxide/cyclic GMP/K(ATP) channel pathway and PPARgamma receptors. Int. J. Neurosci. 2020, 131, 1004-1011.

- Amarante, L.H.; Duarte, I.D. The kappa-opioid agonist (+/-)-bremazocine elicits peripheral antinociception by activation of the L-arginine/nitric oxide/cyclic GMP pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 454, 19-23.

- Ghorbanzadeh, B.; Kheirandish, V.; Mansouri, M.T. Involvement of the L-arginine/Nitric Oxide/Cyclic GMP/KATP Channel Pathway and PPARγ Receptors in the Peripheral Antinociceptive Effect of Carbamazepine. Drug Res. 2019, 69, 650–657. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, B.; Mansouri, M.T.; Naghizadeh, B.; Alboghobeish, S. Local antinociceptive action of fluoxetine in the rat formalin assay: role of l-arginine/nitric oxide/cGMP/KATP channel pathway. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 96, 165–172. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.I.; Granados-Soto, V.; Castañeda-Hernández, G. The NO-cGMP-K+ channel pathway participates in the antinociceptive effect of diclofenac, but not of indomethacin. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003, 76, 187-195.

- Ortiz, M.I.; Medina-Tato, D.A.; Sarmiento-Heredia, D.; Palma-Martínez, J.; Granados-Soto, V. Possible activation of the NO–cyclic GMP–protein kinase G–K+ channels pathway by gabapentin on the formalin test. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2006, 83, 420–427. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.I.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Castañeda-Hernández, G. Participation of the opioid receptor - nitric oxide - cGMP - K(+) channel pathway in the peripheral antinociceptive effect of nalbuphine and buprenorphine in rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2020, 98, 753-762.

- Ortiz, M.I.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Muñoz-Pérez, V.M.; Salas-Casas, A.; Castañeda-Hernández, G. Role of the NO-cGMP-K+ channels pathway in the peripheral antinociception induced by α-bisabolol. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 99, 1048–1056. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.I.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Muñoz-Pérez, V.M.; Medina-Solís, C.E.; Castañeda-Hernández, G. Citral inhibits the nociception in the rat formalin test: effect of metformin and blockers of opioid receptor and the NO-cGMP-K+ channel pathway. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2022, 100, 306–313. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.I.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Castañeda-Hernández, G.; Medina-Solís, C.E. Effect of nitric oxide-cyclic GMP-K+ channel pathway blockers; naloxone and metformin; on the antinociception induced by the diuretic pamabrom. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2023, 101, 41-51.

- Alexander, S.P.H.; Mathie, A.; Peters, J.A.; Veale, E.L.; Striessnig, J.; Kelly, E.; et al. The Concise Guide to Pharmacology 2019/20: Ion channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, S142–S228.

- Dascal, N.; Kahanovitch, U. The Roles of Gβγ and Gα in Gating and Regulation of GIRK Channels. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2015, 123, 27–85.

- Zimmermann, M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. PAIN® 1983, 16, 109–110. [CrossRef]

- McNamara, C.R.; Mandel-Brehm, J.; Bautista, D.M.; Siemens, J.; Deranian, K.L.; Zhao, M.; Hayward, N.J.; Chong, J.A.; Julius, D.; Moran, M.M.; et al. TRPA1 mediates formalin-induced pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13525–13530. [CrossRef]

- Muley, M.M.; Krustev, E.; McDougall, .J.J. Preclinical Assessment of Inflammatory Pain. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2016, 22, 88–101.

- Ortiz, M.I. Metformin and phenformin block the peripheral antinociception induced by diclofenac and indomethacin on the formalin test. Life Sci. 2012, 90, 8–12. [CrossRef]

- Mónica, F.; Bian, K.; Murad, F. The Endothelium-Dependent Nitric Oxide-cGMP Pathway. Adv. Pharmacol. 2016, 77, 1–27.

- Xiao, S.; Li, Q.; Hu, L.; Yu, Z.; Yang, J.; Chang, Q.; et al. Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulators and Activators: Where are We and Where to Go? Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 1544–1557.

- Koesling, D.; Mergia, E.; Russwurm, M. Physiological Functions of NO-Sensitive Guanylyl Cyclase Isoforms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 2653–2665. [CrossRef]

- Ocaña, M.; Cendán, C.M.; Cobos, E.J.; Entrena, J.M.; Baeyens, J.M. Potassium channels and pain: present realities and future opportunities. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 500, 203–219. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Priego, C.G.; Méndez-Mena, R.; Baños-González, M.A.; Araiza-Saldaña, C.I.; Castañeda-Corral, G.; Torres-López, J.E. Antihyperalgesic Effects of Indomethacin, Ketorolac, and Metamizole in Rats: Effects of Metformin. Drug Dev. Res. 2017, 78, 98–104. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).