Introduction

In the era of precision medicine, RNA therapeutics have emerged as a powerful approach to correct genetic errors, modulate gene expression, and influence cellular pathways with high specificity. Since the discovery of small nuclear RNAs in the 1960s (Hadjiolov et al., 1966) and RNA interference (RNAi) in 1998 RNA has evolved from a passive messenger to a key regulatory molecule. The success of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 highlighted RNA’s clinical scalability and safety, positioning it as a versatile therapeutic platform. Once considered unstable, RNA is now valued for its regulatory and catalytic roles, enabling interventions across diverse diseases (Jones et al., 2024). Advances in mRNA vaccines, RNAi, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), ribozymes, and small activating RNAs (saRNAs) have made RNA-based interventions clinically viable (Sparmann & Vogel, 2023). RNA therapies are now being developed for genetic, oncological, neurodegenerative, and rare metabolic diseases, especially where traditional small molecules and biologics fall short (Niazi, 2023). These breakthroughs have energized the global pursuit of RNA medicine.

Several RNA modalities—ASOs, siRNAs, miRNAs, mRNAs, and aptamers—target gene expression through distinct mechanisms. Yet challenges remain in the form of RNA instability, immune activation, delivery specificity, and manufacturing complexity (Paunovska et al., 2022). Innovations in nanoparticle carriers, chemical modification, and AI-assisted design are now driving progress (X. Sun et al., 2024). As technology converges with clinical need, RNA therapeutics are shaping the future of personalized medicine. This review explores key RNA platforms, delivery strategies, clinical progress, and future directions.

Classes of RNA Therapeutics

RNA therapies offer precise, gene-level interventions for a broad range of diseases. Unlike traditional drugs that modulate protein function, RNA-based therapeutics act upstream—either silencing harmful genes or enabling therapeutic protein production (Chery, 2016). These can be classified by structure and mechanism into antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), messenger RNAs (mRNAs), aptamers, and RNA-targeting small molecules. While their mechanisms vary—from gene silencing to protein replacement—all exploit RNA’s central role in gene regulation. Below outlined are the major classes, highlighting their therapeutic applications and limitations.

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs)

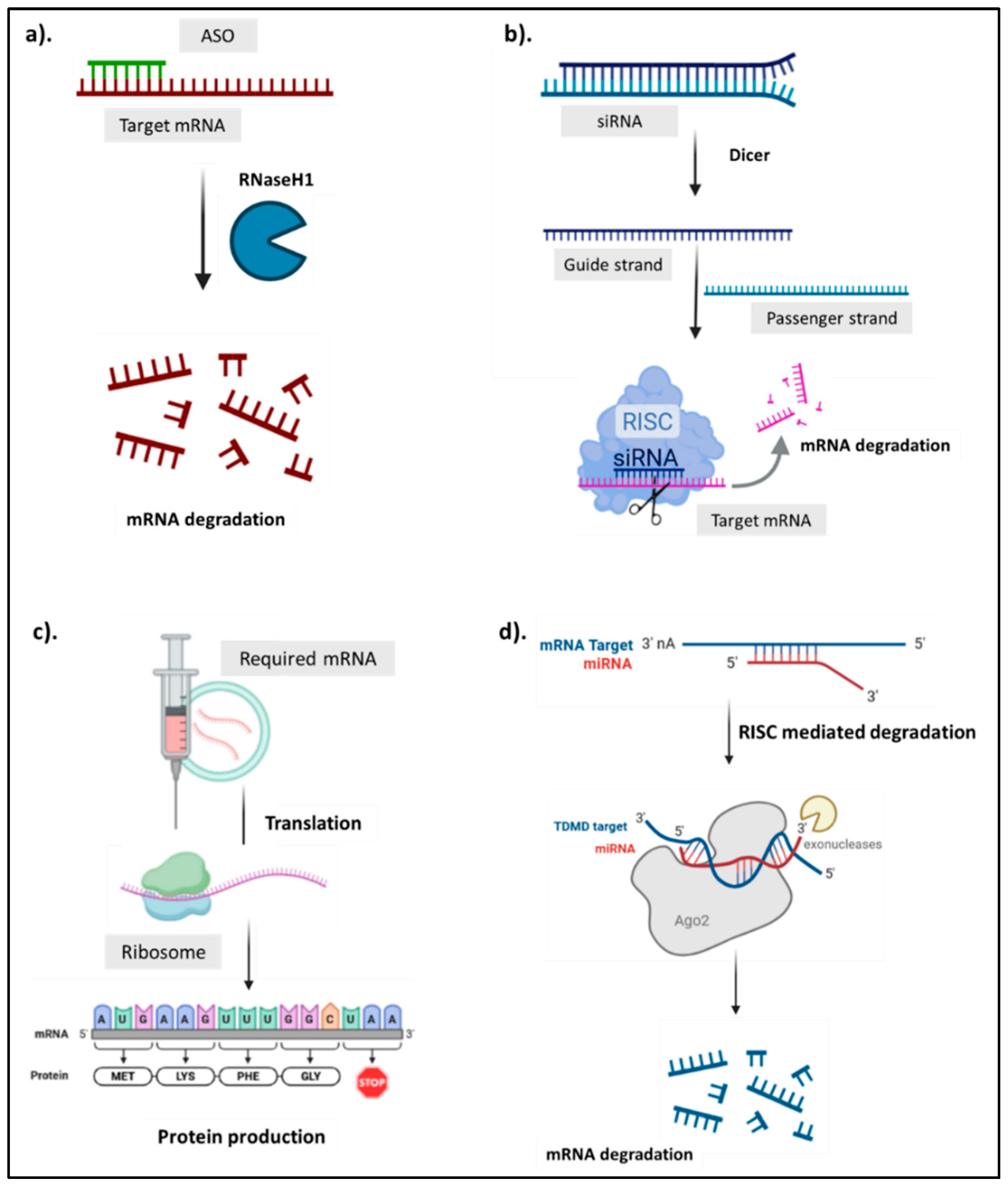

ASOs are short synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that bind target mRNA via complementary base pairing, modulating gene expression through mechanisms such as RNase H-mediated degradation or steric blockade (

Figure 1a). The most common strategy uses RNase H1, an endogenous enzyme that cleaves the RNA strand of an RNA–DNA hybrid, leading to mRNA degradation and protein silencing (Vickers & Crooke, 2014). This is particularly effective in conditions involving toxic gain-of-function mutations or protein overexpression (Crooke et al., 2018). Alternatively, steric-blocking ASOs bind to mRNA regions—like splice junctions or translation start sites—to alter splicing or inhibit translation without degradation. This approach is used in spinal muscular atrophy, where correcting aberrant splicing restores functional protein expression (Bennett et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2024; Rigo et al., 2014).

ASOs offer high sequence specificity and modularity with relatively low off-target risk (Roberts et al., 2020). However, delivery remains a barrier—especially beyond the liver and CNS. Immune activation and patient-to-patient variability also limit broad utility Notable examples include- Eplontersen, in development for hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR), a disorder involving misfolded proteins that damage nerves and the heart (Brannagan et al., 2022), and Vutrisiran (Amvuttra), an FDA-approved ASO for hATTR with reduced dosing frequency and sustained efficacy (Planté-Bordeneuve & and Perrain, 2024). These demonstrate ASOs’ potential in genetic and neurodegenerative conditions, though long-term safety and accessibility remain under evaluation.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) Therapies

Unlike ASOs, siRNAs are double-stranded RNA molecules (~21–23 nucleotides) that induce post-transcriptional gene silencing via the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. Once delivered into cells, siRNAs are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which uses one strand to target and degrade complementary mRNA (

Figure 1b). After cellular uptake, synthetic siRNAs are released into the cytoplasm, where RISC discards the passenger strand and retains the guide strand as a molecular GPS. Upon binding its target, the Argonaute 2 (Ago2) protein cleaves the mRNA, preventing translation and silencing the encoded protein (Alshaer et al., 2021). This allows siRNAs to act upstream of protein synthesis, targeting even “undruggable” genes. However, they are vulnerable to nuclease degradation and can activate innate immune responses. Chemical modifications (e.g., PEGylation, GalNAc conjugation) have improved stability and targeting, but concerns remain around off-target effects and dose-related toxicity (Choi et al., 2025). Compared to ASOs, siRNAs are more potent in hepatocytes, but less effective in extra-hepatic tissues.

Despite these caveats, siRNA therapeutics have progressed significantly in clinical translation. Lepodisiran, developed by Eli Lilly, reduces lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] levels—a key cardiovascular risk factor—by 93.9% Similarly, Nedosiran (Rivfloza) has been approved for primary hyperoxaluria, a rare metabolic disorder caused by excessive oxalate production (Syed, 2023). Another investigational drug, Zerlasiran, has achieved up to 99% reduction in Lp(a) levels in early trials (Nissen et al., 2024). These results are promising, but the long-term clinical benefits of extreme biomarker reduction still need validation in diverse patient populations.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) Therapies

mRNA therapies differ from ASOs and siRNAs by introducing synthetic genetic instructions that enable cells to produce therapeutic proteins, rather than silencing gene expression. This approach gained global attention during the COVID-19 pandemic, when mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech demonstrated rapid, effective protection (Tenforde et al., 2021).

Synthetic mRNA is typically delivered into the cytoplasm via lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), where it is translated by ribosomes into proteins (

Figure 1c). These proteins can serve as antigens (in vaccines), or exert direct therapeutic effects (Hassett et al., 2024) or replace missing or defective proteins (Vavilis et al., 2023). Unlike DNA-based or genome-editing approaches, mRNA does not enter the nucleus or alter the genome, making it transient, controllable, and safer. Once its function is complete, it is naturally degraded, minimizing long-term risks. Recent innovations have enhanced the stability and translational efficiency of mRNA, such as the incorporation of modified nucleotides (e.g., N1-methyl-pseudouridine) (Svitkin et al., 2017), optimized codon usage (Presnyak et al., 2015), and untranslated region (UTR) engineering (Reshetnikov et al., 2024). These modifications reduce innate immune responses while increasing protein yield and duration of expression. In vaccine applications, for instance, these mechanisms enable the body to recognize and mount an immune response to a pathogen’s antigen, thereby "training" the immune system without using a live virus (Cao et al., 2024).

Beyond vaccines, mRNA is now being explored for a wide range of diseases. One particularly exciting area is cancer treatment, where personalized mRNA vaccines are being developed to help the immune system recognize and attack tumor cells (Heine et al., 2021). Clinical trials in Europe are testing this approach, known as Individualized Neoantigen Therapy (Weber et al., 2024). Another promising mRNA therapy, ARCT-032, is designed as an inhalable treatment for cystic fibrosis. It delivers mRNA directly to lung cells, instructing them to produce the missing CFTR protein, which is essential for normal lung function (Geller et al., 2024; Rowe et al., 2023). As delivery systems improve, organ-targeted mRNA platforms could transform treatment of genetic and chronic diseases, expanding mRNA’s therapeutic reach.

MicroRNA Based Therapies

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous small non-coding RNAs (~20–24 nucleotides) that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation or translational repression (Bartel, 2018). Unlike siRNAs, which bind with perfect complementarity, miRNAs typically have partial complementarity, allowing them to regulate multiple mRNAs and affect entire gene networks. This makes them attractive for complex, multifactorial diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative disorders (Calin & Croce, 2006; Rupaimoole & Slack, 2017). For example, miR-34a, a well-known tumor-suppressive miRNA, targets multiple oncogenes and has been shown to induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in various cancers (Trang et al., 2011). Conversely, oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs) like miR-21 are upregulated in several malignancies and contribute to chemoresistance, proliferation, and metastasis by suppressing tumor suppressor genes (Rhim et al., 2022). These insights have led to the development of miRNA mimics and antagomiRs—chemically modified oligonucleotides that restore or inhibit specific miRNA functions, respectively.

However, broad target reach poses translational challenges. A single miRNA can affect hundreds of genes, raising concerns about off-target effects and toxicity (van Rooij & Kauppinen, 2014). Also, miRNA expression is highly tissue- and context-specific, complicating delivery. Unlike ASOs or siRNAs—where targeting is more predictable—miRNA therapies require precise validation and controlled delivery. Despite these complexities, early clinical trials have offered cautious optimism. MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, was the first miRNA-based therapy to enter clinical testing for solid tumors. Although it showed signs of tumor suppression, the trial was terminated due to immune-related adverse events (Beg et al., 2017). More recently, anti-miR-132 therapy demonstrated improvement in heart failure models by modulating pathological cardiac remodeling (Foinquinos et al., 2020). Additionally, miRNA signatures are being actively explored as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers due to their stability in circulation and disease-specific expression patterns. Despite limited approvals, miRNA therapeutics may excel in diseases driven by dysregulated networks rather than single mutations. Progress in delivery systems and target profiling will be key to their success.

RNA Editing Technologies

RNA editing is an emerging approach that allows precise, reversible modification of RNA sequences, enabling therapeutic correction of mutations without altering DNA (Booth et al., 2023). This offers a safer alternative to permanent genome editing tools like CRISPR.

The most studied method involves adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) editing, catalyzed by ADAR enzymes. Inosine is interpreted as guanosine during translation, potentially restoring normal protein function (Jimeno et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021). Therapeutic strategies recruit endogenous ADAR using engineered guide RNAs or antisense oligonucleotides, which bind target RNA to create double-stranded structures recognized by ADAR, enabling site-specific editing (Y. Sun et al., 2025).

Key developments include Wave Life Sciences using RNA editing to restore alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) production in patients with AAT deficiency (Philippidis, 2025), and development of Korro Bio’s OPERA™ platform in collaboration with Novo Nordisk to target heart and metabolic diseases using RNA editing (Grinstein, 2024). These platforms highlight growing momentum around RNA editing as a scalable, tissue-specific therapeutic strategy.

Alternative Approaches to RNA Targeting

Beyond editing, several non-coding RNA-targeting strategies have emerged, including aptamers, RNA-binding small molecules, and riboswitches. Each leverages RNA structure and function for selective modulation, expanding therapeutic possibilities.

Aptamers: These are short single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that fold into unique 3D structures, enabling high-affinity binding to proteins, small molecules, or RNAs. Selected via SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment), they offer antibody-like specificity with advantages in size, synthesis, and immunogenicity (J. Zhou & Rossi, 2017).

A notable therapeutic example is Pegaptanib (Macugen), an RNA aptamer approved for age-related macular degeneration (AMD), binds and inhibits VEGF165 to prevent retinal neovascularization (Ng et al., 2006). Aptamers are also being explored as delivery vehicles. For instance, aptamers targeting PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen) have been conjugated to siRNAs, achieving tumor-specific delivery and gene silencing (McNamara et al., 2006).

RNA-targeting small molecules: These agents bind RNA structural motifs (bulges, loops, G-quadruplexes) to modulate stability, splicing, or translation. Historically challenging due to RNA’s dynamic structure, recent advances in high-throughput screening and structural modeling are accelerating discovery (Childs-Disney et al., 2022).

One promising case is Risdiplam (Evrysdi), a small molecule approved for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Risdiplam modulates alternative splicing of the SMN2 pre-mRNA, promoting the production of functional SMN protein—a strategy that circumvents the need for direct gene replacement or RNAi (Ratni et al., 2018). Risdiplam has shown both clinical efficacy and oral bioavailability, underscoring the therapeutic potential of RNA-targeting small molecules. Similarly, the small molecule branaplam, also developed for SMA, demonstrated potent RNA splicing modulation, although its development was paused due to concerns around long-term toxicity (Novartis, 2022).

Riboswitches: Naturally occurring in bacterial mRNAs, riboswitches regulate gene expression by binding small ligands that trigger conformational changes, affecting transcription, translation, or RNA stability (Breaker, 2012). Inspired by this natural mechanism, synthetic biologists have engineered synthetic riboswitches or aptazymes that respond to small molecules like theophylline or tetracycline to control gene expression in eukaryotic cells (Bowlby, 2023). In a study, a theophylline-responsive riboswitch was engineered into mammalian cells to conditionally regulate transgene expression, demonstrating a potential tool for gene therapy where spatial or temporal control is required (Win & Smolke, 2007). Although no riboswitch-based therapeutics are currently approved, their inherent ligand-responsiveness and modularity make them attractive candidates for programmable and self-regulating RNA devices in synthetic biology and future therapeutic applications.

Table 1 summarizes the key properties, mechanisms, and clinical relevance of major RNA therapeutic classes discussed above. Together, all these strategies illustrate the expanding toolkit for targeting RNA with methods including traditional base-pairing and beyond. By exploiting structural features and conformational plasticity, they pave the way for novel modes of action in RNA-based therapeutics. While each modality operates through a unique mechanism, they share a common goal: to precisely modulate gene expression and restore normal biological function.

Clinical Applications and Recent Advances in RNA Therapeutics

RNA therapeutics are reshaping treatment across diverse diseases, offering precision strategies for conditions previously deemed untreatable. This section highlights key clinical advances and the expanding impact of RNA technologies.

Cardiovascular Diseases

As the leading global cause of mortality, cardiovascular disease is a key target for RNA therapeutics. siRNAs and ASOs are being used to modulate lipid metabolism and reduce cardiovascular risk at the genetic level (Liao et al., 2024; Katzmann et al., 2020). Inclisiran, an siRNA targeting PCSK9, lowers LDL cholesterol with twice-yearly dosing, improving adherence over daily statins and has already been approved for use (Luo et al., 2023). Lepodisiran and Zerlasiran significantly reduce lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], a key risk factor. Effects persist for months post-injection (Nissen et al., 2023, 2024). These therapies signal a paradigm shift—moving beyond symptom management toward durable, gene-targeted interventions.

Genetic Disorders

RNA therapeutics are transforming treatment for rare genetic diseases by directly targeting pathogenic mutations. Platforms include ASOs, siRNAs, and emerging RNA editing technologies. Vutrisiran (Amvuttra), an FDA-approved siRNA for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), silences mutant TTR expression, slowing disease progression (Planté-Bordeneuve & and Perrain, 2024). Eplontersen, an ASO in late-stage trials for the same condition, offers a complementary approach (Coelho et al., 2023). Nedosiran (Rivfloza), approved for primary hyperoxaluria, inhibits a key enzyme in oxalate overproduction, offering a novel therapeutic route (Goldfarb et al., 2023).

Emerging RNA editing technologies are also gaining momentum. Wave Life Sciences’ ADAR platform shows promise for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, enabling reversible, transcript-level correction without altering DNA (Erion et al., 2025). These advances demonstrate the clinical reach and flexibility of RNA-based interventions in monogenic disorders.

Oncology: RNA-Based Cancer Therapies

RNA therapeutics are reshaping cancer treatment through mRNA vaccines, RNA interference, and antisense strategies. Among the most promising are individualized neoantigen vaccines, which use patient-specific tumor mutations to train the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells (Weber et al., 2024).

Beyond vaccines, RNAi therapies silence oncogenic drivers, suppressing tumor growth (Sousa & Videira, 2025), ASOs correct aberrant splicing and restore normal gene expression (Leclair et al., 2025). Biotech leaders such as Alnylam and Moderna are advancing RNA-based cancer therapeutics, with early-phase trials showing encouraging efficacy and safety.

Neurological Disorders

Treating neurological diseases is challenging due to the complexity of the brain and the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Yet, ASOs have shown progress in neurodegenerative conditions, offering targeted silencing of disease-causing genes. For instance, Tofersen, an ASO for ALS with SOD1 mutations, slows neurodegeneration and improves function (Miller et al., 2022). ASOs have also shown efficacy in Huntington’s disease and spinocerebellar ataxia, reducing toxic protein production (McLoughlin et al., 2018; Southwell et al., 2018). Advancements in intrathecal delivery have improved CNS targeting Looking ahead, exosome-based RNA carriers could enable non-invasive, brain-specific delivery, expanding therapeutic reach.

Infectious Diseases

The most high-profile success of RNA therapeutics is the rapid development of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19. Vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna demonstrated the platform’s speed, safety, and immune efficacy (Tenforde et al., 2021). These vaccines not only highlighted the speed and flexibility of mRNA technology but also demonstrated its capacity to elicit strong, durable immune responses. Building on this success, companies like Moderna and BioNTech are now leveraging mRNA platforms to develop vaccines for other infectious threats, including influenza, HIV, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (Matarazzo & Bettencourt, 2023). Next-generation approaches feature self-amplifying RNA (saRNA), which enhances vaccine potency while lowering the required dosage (Silva-Pilipich et al., 2024). In parallel, inhalable mRNA formulations are emerging as game-changers for respiratory infections. Notably, ARCT-032—an inhalable mRNA therapy for cystic fibrosis—is in clinical trials and could mark a significant breakthrough in treating chronic pulmonary diseases (Geller et al., 2024). These developments show the adaptability of mRNA for both preventive and therapeutic infectious disease applications.

Expanding the Scope of RNA Therapeutics

Beyond their proven efficacy in genetic, oncological, neurological, and infectious diseases, RNA therapeutics are now being explored in a growing range of clinical areas. In autoimmune conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Guo et al., 2016) and rheumatoid arthritis (Rai et al., 2019), RNA-based therapies may offer more targeted immunomodulation compared to traditional biologics, minimizing systemic side effects. In regenerative medicine, mRNA is being investigated for its ability to stimulate tissue repair and wound healing (Antony et al., 2023), Studies show that mRNA encoding growth factors may accelerate bone and cartilage regeneration (Tejedor et al., 2024), opening up new possibilities for orthopedic and trauma-related treatments.

These novel applications highlight RNA’s versatility across medical domains, extending its reach far beyond rare diseases or vaccines. However, delivery remains the primary bottleneck to broader adoption—particularly for targeting non-liver tissues, crossing barriers, and avoiding immune responses.

Challenges in RNA Delivery

Despite their potential, RNA therapeutics face significant delivery barriers that impact clinical success. Key challenges include:

RNA stability and degradation: RNA molecules—especially mRNA and siRNA—are highly unstable in physiological conditions due to rapid nuclease degradation. Naked RNA has a short half-life in circulation. Chemical modifications (e.g., 2′-O-methylation, phosphorothioate linkages) improve stability, but further innovations are needed to ensure sustained delivery and therapeutic efficacy (Fàbrega et al., 2022).

Immune activation and off-target effects: Unmodified RNA can trigger innate immune responses through Toll-like receptors (TLRs)—particularly TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8—leading to cytokine storms and toxicity (Karikó et al., 2005). Modified nucleotides, such as pseudouridine, have reduced this risk, as seen in COVID-19 vaccines.

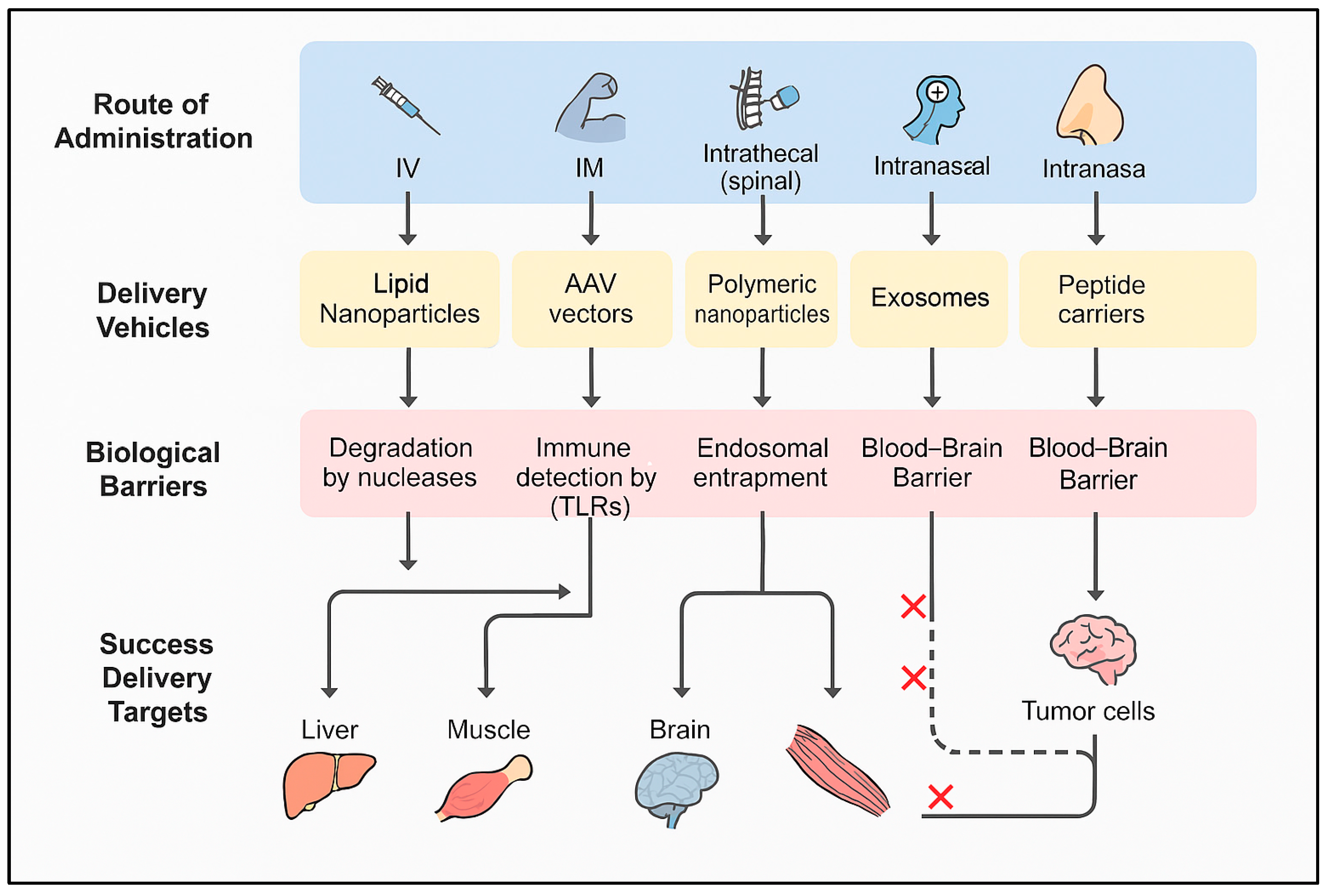

Crossing biological barriers: Some RNA therapies, especially those targeting the brain, eyes, and muscles, require delivery across highly selective barriers: a) The Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) prevents most molecules, including RNA, from entering the central nervous system (CNS). This limits the effectiveness of RNA-based treatments for neurodegenerative diseases like Huntington’s and ALS. b) The Blood-Retinal Barrier (BRB) hinders RNA-based interventions for ocular diseases. c) Muscle Tissue Barriers of skeletal and cardiac muscles pose unique challenges due to their extracellular matrix and limited RNA uptake. Emerging solutions include exosomes and focused ultrasound, offering non-invasive penetration of these barriers (Ravichandiran et al., 2024).

Endosomal escape: After endocytosis, many RNA payloads become trapped in endosomes and degraded. This step is a major bottleneck. Current approaches to improve escape include the use of pH-sensitive lipids, membrane-disruptive peptides, and responsive polymeric carriers (Chatterjee et al., 2024).

Scalability and manufacturing constraints: RNA drug production requires stringent processes and cold-chain logistics, raising costs and limiting access. Current research is exploring the development of thermostable formulations, room-temperature-stable delivery platforms, and self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) systems to address these limitations (Whitley et al., 2022).

Despite these formidable challenges, the field of RNA therapeutics is advancing at an unprecedented pace. Researchers and industry leaders are actively working on innovative delivery strategies to overcome these limitations. With continued breakthroughs in formulation science and molecular engineering, the future of RNA delivery looks increasingly promising.

Prospects and Innovations in RNA Delivery

As RNA therapeutics advance, delivery strategies are evolving from basic protection and uptake toward precision targeting, efficiency, and tissue selectivity.

Advanced Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): LNPs have become the clinical standard for RNA delivery, proven during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. Composed of ionizable lipids, they remain neutral at physiological pH but become positively charged in endosomes, enhancing endosomal escape and cytoplasmic release. Recent findings emphasize the importance of rational lipid design—fine-tuning chemical structure for both safety and transfection efficiency (Xu et al., 2025).This underscores the importance of rational lipid design—tailoring chemical structures to maximize both safety and transfection efficiency.

However, conventional LNPs show preferential liver accumulation, limiting non-hepatic applications. To address this constraint, researchers are now engineering organ-specific LNPs, particularly for challenging targets like the central nervous system (CNS). Crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) has been a long-standing obstacle for RNA delivery, but novel strategies are emerging. For example developed peptide-functionalized LNPs capable of selectively targeting neurons and endothelial cells while bypassing hepatic uptake—dramatically enhancing brain-specific mRNA delivery (Han et al., 2025). Similarly, Bian et al. (2025) introduced a berberine-derived ionizable lipid that facilitates BBB penetration via self-assembly and π–π interactions, achieving efficient RNA transfection in neural tissues in vivo (Bian et al., 2025). These innovations move LNPs beyond the liver, enabling spatial control and broader disease targeting.

Peptide-based carriers: Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) and tumor-homing peptides (THPs) offer targeted, non-viral RNA delivery with lower immunogenicity. CPPs cross membranes and even the blood-brain barrier, making them promising for neurodegenerative diseases (Pirhaghi et al., 2024). In these contexts, CPP-mediated RNA delivery has been shown to mitigate pathogenic protein expression and improve neuronal outcomes in preclinical models. THPs bind overexpressed markers in tumors, enabling precise RNA or drug delivery (Bottens & Yamada, 2022). The iRGD peptide, which binds integrins, is cleaved to expose a C-end Rule (CendR) motif, enhancing deep tissue penetration and co-delivery(Milewska et al., 2024).

Challenges include serum stability, protease degradation, and receptor heterogeneity, but advances like peptide cyclization and multifunctional conjugation are addressing these issues.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) and exosomes for RNA transport: Exosomes—a subtype of extracellular vesicles—have gained attention as natural RNA carriers, offering biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and the ability to cross biological barriers, including the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Derived from endosomal pathways, exosomes carry RNAs, proteins, and lipids between cells, mimicking natural intercellular communication. Their endogenous origin facilitates efficient uptake and tolerogenic responses. In oncology, engineered exosomes have been successfully loaded with therapeutic RNAs (e.g., siRNAs or miRNAs) to selectively target tumor cells, reducing systemic toxicity and enhancing therapeutic efficacy (Huyan et al., 2020). Similar applications are being explored in cardiovascular diseases, where exosomes derived from stem cells have demonstrated the capacity to deliver pro-angiogenic RNAs, promoting vascular repair and cardiac regeneration (Neves et al., 2023).

In the neurological domain, exosomes offer a rare advantage shared by few platforms: the natural ability to cross the BBB. This has fueled research into exosome-mediated RNA delivery for neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, where conventional delivery vectors often fall short (Singh et al., 2024). Despite these advantages, the field faces substantial challenges like scalable production, standardized purification protocols, and efficient RNA loading techniques remain significant bottlenecks. Tissue specificity and off-target effects are still being actively addressed through advanced engineering approaches—such as surface modification with targeting ligands, exosomal membrane fusion with viral-like envelopes, and endogenous exosome tropism modulation.

RNA nanostructures and self-assembling carriers: RNA nanostructures, including RNA origami, represent a next-gen delivery platform. These engineered 3D assemblies leverage RNA’s programmability and structural versatility for controlled release, targeted delivery, and immune stealth. For instance, RNA origami nanovaccines have induced strong antitumor immunity in vivo (Yip et al., 2024). RNA-based nanorobots can perform stimulus-responsive drug release, adapting to environmental cues like pH or enzymatic activity (Vallina et al., 2024). These nanodevices can be tailored to respond to environmental triggers such as pH, temperature, or specific enzymatic activity, enabling dynamic interaction with complex biological environments.

A comparative summary of key strategies currently explored to achieve RNA delivery is presented in

Table 2. Despite these advancements, key translational barriers persist. RNA nanostructures are inherently susceptible to nuclease degradation and often face challenges in systemic stability, in vivo tracking, and large-scale production. Moreover, regulatory pathways for such novel RNA-based constructs remain underdeveloped, posing hurdles for clinical adoption. Still, advances in chemical modification, scaffold stabilization, and modular design are accelerating their translational potential.

Overcoming the blood-brain barrier (BBB): The blood–brain barrier (BBB) remains a major obstacle for delivering RNA therapeutics to the central nervous system (CNS). While it protects the brain from toxins, it also blocks most macromolecules, including RNA drugs.

To overcome this, researchers are developing non-invasive and receptor-mediated strategies.

a) Ligand-modified nanoparticles: Nanoparticles are functionalized with ligands (e.g., transferrin, antibodies) that exploit receptor-mediated transcytosis. These ligands bind to receptors on BBB endothelial cells, allowing vesicular transport into the brain (Ulbrich et al., 2009). This approach enables CNS delivery while minimizing systemic toxicity.

b) Intranasal RNA delivery: Intranasal administration bypasses the BBB entirely via the olfactory and trigeminal pathways, allowing direct CNS access without invasive procedures.

It has successfully delivered siRNAs and mRNAs in models of neurodegeneration and inflammation (Hanson & Frey, 2008).

Figure 2 illustrates a comparative overview of RNA delivery routes, biological barriers, and major delivery platforms used to achieve targeted therapeutic outcomes. While each approach has its limitations—such as variability in nasal absorption or receptor saturation—ongoing optimization of formulation chemistry and delivery routes is steadily improving their clinical viability.

Personalized RNA therapies using AI and machine learning: Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are accelerating the development of personalized RNA therapeutics, enabling precise design based on individual genomic profiles AI platforms can predict optimal RNA sequences, identify disease-specific targets, and tailor interventions to patient-specific mutations or expression patterns. In oncology, AI helps uncover dysregulated gene networks, informing the design of tumor-specific RNA drugs (Bhinder et al., 2021). For rare diseases—where data is limited—ML models can detect hidden patterns to suggest viable RNA targets (Brasil et al., 2019). Additionally, AI contributes to predictive modeling of treatment responses, enhancing the safety and personalization of RNA therapeutics. These tools enhance both therapeutic specificity and development speed.

Scaling up and cost-effective manufacturing: To ensure global accessibility, RNA manufacturing must be scalable, cost-effective, and logistically feasible. Notable advancements include the creation of room-temperature-stable RNA formulations, which reduce the need for cold-chain logistics, thereby facilitating distribution in resource-limited settings. Additionally, continuous-flow RNA synthesis technologies are being optimized to enable high-throughput, automated production processes that significantly cut down manufacturing time and cost (Ouranidis et al., 2021), Another transformative innovation is the development of self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) platforms, which require lower doses while achieving prolonged therapeutic effects, enhancing both cost-efficiency and clinical efficacy (Bloom et al., 2021). While RNA therapeutics represent a paradigm shift in modern medicine, their widespread clinical adoption hinges on overcoming several delivery and stability-related barriers. Breakthroughs in nanotechnology, peptide engineering, and the use of extracellular vesicles are expanding the toolkit for efficient RNA delivery, improving tissue targeting, and reducing immunogenicity. Moreover, AI-driven drug design continues to play a vital role in optimizing therapeutic RNA sequences and predicting outcomes, streamlining the development pipeline.

Conclusions and Outlook

RNA therapeutics are no longer confined to theoretical promise—they’re becoming tangible solutions, with siRNA, ASO, and mRNA platforms gaining regulatory approval. The ability to modulate gene expression with such precision feels like a turning point in how we understand and treat disease. Still, significant hurdles remain—particularly in ensuring delivery to non-liver tissues, mitigating immune responses, and making these therapies globally accessible. The road ahead is as challenging as it is inspiring.

Looking ahead, innovations in circular RNAs and self-amplifying RNAs offer improved stability, durability, and translational efficiency, reducing dosing frequency—particularly for vaccines and chronic diseases (Bloom et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). A key priority is optimizing delivery systems. While lipid nanoparticles remain dominant, the need for biodegradable, tissue-targeted, and non-immunogenic vectors is growing. Advances in polymer-based carriers, exosome-mediated delivery, and peptide-functionalized vectors show potential for enhancing pharmacokinetics and reducing off-target effects. For example, exosomes offer high stability, biocompatibility, and intrinsic targeting capabilitie (Lu et al., 2023).

Computational tools, including AI and machine learning, are now streamlining RNA design, structural modeling, and off-target prediction, accelerating preclinical development. These platforms are also driving progress in RNA-small molecule interaction modeling, opening new possibilities for RNA-targeted drug discovery (Y. Zhou & Chen, 2024). Importantly, RNA-based drugs can access “undruggable” targets such as non-coding RNAs, transcription factors, and regulatory elements—expanding therapeutic options in oncology and rare genetic disorders where conventional drugs fall short.

However, long-term success will depend on both scientific and structural progress. Global accessibility requires scalable, cost-effective manufacturing, robust supply chains, and adaptive regulatory frameworks. Initiatives like the Gates Foundation’s mRNA production investment in Africa highlight the urgency of localized RNA manufacturing to address health equity and pandemic preparedness (AP News, 2023). Regulatory pathways must also adapt to accommodate platform-based drug designs and novel RNA constructs.

In conclusion, RNA therapeutics are redefining the treatment landscape, enabling precision interventions at the genetic level. The next decade will be shaped by advances in RNA chemistry, delivery technologies, and computational biology, driving these therapies from bench to bedside at global scale.

Author Declarations

The author declares no conflict of interest and received no external funding for this work. No new data were created or analysed in this study. The author is solely responsible for the conceptualization, literature review, writing, and editing of the manuscript.

References

- Adams, D.; Gonzalez-Duarte, A.; O’Riordan, W. D.; Yang, C.-C.; Ueda, M.; Kristen, A. V.; Tournev, I.; Schmidt, H. H.; Coelho, T.; Berk, J. L.; Lin, K.-P.; Vita, G.; Attarian, S.; Planté-Bordeneuve, V.; Mezei, M. M.; Campistol, J. M.; Buades, J.; Brannagan, T. H.; Kim, B. J.; Suhr, O. B. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379(1), 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshaer, W.; Zureigat, H.; Al Karaki, A.; Al-Kadash, A.; Gharaibeh, L.; Hatmal, M. M.; Aljabali, A. A. A.; Awidi, A. siRNA: Mechanism of action, challenges, and therapeutic approaches. European Journal of Pharmacology 2021, 905, 174178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antony, J. S.; Birrer, P.; Bohnert, C.; Zimmerli, S.; Hillmann, P.; Schaffhauser, H.; Hoeflich, C.; Hoeflich, A.; Khairallah, R.; Satoh, A. T.; Kappeler, I.; Ferreira, I.; Zuideveld, K. P.; Metzger, F. Local application of engineered insulin-like growth factor I mRNA demonstrates regenerative therapeutic potential in vivo. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2023, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, L. R.; Sahly, H. M. E.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S. A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C. B.; McGettigan, J.; Khetan, S.; Segall, N.; Solis, J.; Brosz, A.; Fierro, C.; Schwartz, H.; Neuzil, K.; Corey, L.; Zaks, T. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384(5), 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D. P. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell 2018, 173(1), 20–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, M. S.; Brenner, A. J.; Sachdev, J.; Borad, M.; Kang, Y.-K.; Stoudemire, J.; Smith, S.; Bader, A. G.; Kim, S.; Hong, D. S. Phase I study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, administered twice weekly in patients with advanced solid tumors. Investigational New Drugs 2017, 35(2), 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C. F.; Kordasiewicz, H. B.; Cleveland, D. W. Antisense Drugs Make Sense for Neurological Diseases. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2021, 61, 831–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M. D.; Waddington-Cruz, M.; Berk, J. L.; Polydefkis, M.; Dyck, P. J.; Wang, A. K.; Planté-Bordeneuve, V.; Barroso, F. A.; Merlini, G.; Obici, L.; Scheinberg, M.; Brannagan, T. H.; Litchy, W. J.; Whelan, C.; Drachman, B. M.; Adams, D.; Heitner, S. B.; Conceição, I.; Schmidt, H. H.; Coelho, T. Inotersen Treatment for Patients with Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379(1), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhinder, B.; Gilvary, C.; Madhukar, N. S.; Elemento, O. Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Research and Precision Medicine. Cancer Discovery 2021, 11(4), 900–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Guo, Q.; Yau, L.-F.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Wu, S.; Qin, X.; Jiang, Z.-H.; Li, C. Berberine-inspired ionizable lipid for self-structure stabilization and brain targeting delivery of nucleic acid therapeutics. Nature Communications 2025, 16(1), 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, K.; van den Berg, F.; Arbuthnot, P. Self-amplifying RNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Gene Therapy 2021, 28(3), 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, B. J.; Nourreddine, S.; Katrekar, D.; Savva, Y.; Bose, D.; Long, T. J.; Huss, D. J.; Mali, P. RNA editing: Expanding the potential of RNA therapeutics. Molecular Therapy 2023, 31(6), 1533–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottens, R. A.; Yamada, T. Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs) as Therapeutic and Diagnostic Agents for Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14(22), 5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, B. Synthetic riboswitches detect biomarker proteins. BioTechniques. 9 June 2023. Available online: https://www.biotechniques.com/diagnostics-preclinical/synthetic-riboswitches-detect-biomarker-proteins/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Brannagan, T. H.; Berk, J. L.; Gillmore, J. D.; Maurer, M. S.; Waddington-Cruz, M.; Fontana, M.; Masri, A.; Obici, L.; Brambatti, M.; Baker, B. F.; Hannan, L. A.; Buchele, G.; Viney, N. J.; Coelho, T.; Nativi-Nicolau, J. Liver-directed drugs for transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System 2022, 27(4), 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil, S.; Pascoal, C.; Francisco, R.; dos Reis Ferreira, V.; A. Videira, P.; Valadão, G. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Rare Diseases: Is the Future Brighter? Genes 2019, 10(12), 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaker, R. R. Riboswitches and the RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2012, 4(2), a003566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calin, G. A.; Croce, C. M. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nature Reviews. Cancer 2006, 6(11), 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Fang, H.; Tian, H. mRNA vaccines contribute to innate and adaptive immunity to enhance immune response in vivo. Biomaterials 2024, 310, 122628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kon, E.; Sharma, P.; Peer, D. Endosomal escape: A bottleneck for LNP-mediated therapeutics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121(11), e2307800120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Heendeniya, S. N.; Le, B. T.; Rahimizadeh, K.; Rabiee, N.; Zahra; ul ain, Q.; Veedu, R. N. Splice-Modulating Antisense Oligonucleotides as Therapeutics for Inherited Metabolic Diseases. Biodrugs 2024, 38(2), 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chery, J. RNA therapeutics: RNAi and antisense mechanisms and clinical applications. Postdoc Journal: A Journal of Postdoctoral Research and Postdoctoral Affairs 2016, 4(7), 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs-Disney, J. L.; Yang, X.; Gibaut, Q. M. R.; Tong, Y.; Batey, R. T.; Disney, M. D. Targeting RNA structures with small molecules. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 2022, 21(10), 736–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.-W.; Kim, J. H.; Kang, D. W.; Cho, H.-Y. A journey into siRNA therapeutics development: A focus on Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2025, 205, 106981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, T.; Marques, W.; Dasgupta, N. R.; Chao, C.-C.; Parman, Y.; França, M. C.; Guo, Y.-C.; Wixner, J.; Ro, L.-S.; Calandra, C. R.; Kowacs, P. A.; Berk, J. L.; Obici, L.; Barroso, F. A.; Weiler, M.; Conceição, I.; Jung, S. W.; Buchele, G.; Brambatti, M. NEURO-TTRansform Investigators. (2023). Eplontersen for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis With Polyneuropathy. JAMA 330(15), 1448–1458. [CrossRef]

- Crooke, S. T.; Witztum, J. L.; Bennett, C. F.; Baker, B. F. RNA-Targeted Therapeutics. Cell Metabolism 2018, 27(4), 714–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erion, D. M.; Liu, L. Y.; Brown, C. R.; Rennard, S.; Farah, H. Editing Approaches to Treat Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. CHEST 2025, 167(2), 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fàbrega, C.; Aviñó, A.; Eritja, R. Chemical Modifications in Nucleic Acids for Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications. Chemical Record (New York, N.Y.) 2022, 22(4), e202100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, R. S.; Mercuri, E.; Darras, B. T.; Connolly, A. M.; Kuntz, N. L.; Kirschner, J.; Chiriboga, C. A.; Saito, K.; Servais, L.; Tizzano, E.; Topaloglu, H.; Tulinius, M.; Montes, J.; Glanzman, A. M.; Bishop, K.; Zhong, Z. J.; Gheuens, S.; Bennett, C. F.; Schneider, E.; ENDEAR Study Group. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Infantile-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. The New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377(18), 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foinquinos, A.; Batkai, S.; Genschel, C.; Viereck, J.; Rump, S.; Gyöngyösi, M.; Traxler, D.; Riesenhuber, M.; Spannbauer, A.; Lukovic, D.; Weber, N.; Zlabinger, K.; Hašimbegović, E.; Winkler, J.; Fiedler, J.; Dangwal, S.; Fischer, M.; Roche; de la, J.; Wojciechowski, D.; Thum, T. Preclinical development of a miR-132 inhibitor for heart failure treatment. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangoul, H.; Altshuler, D.; Cappellini, M. D.; Chen, Y.-S.; Domm, J.; Eustace, B. K.; Foell, J.; Fuente; de la, J.; Grupp, S.; Handgretinger, R.; Ho, T. W.; Kattamis, A.; Kernytsky, A.; Lekstrom-Himes, J.; Li, A. M.; Locatelli, F.; Mapara, M. Y.; Montalembert, M. de; Rondelli, D.; Corbacioglu, S. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384(3), 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News, AP. Gates Foundation funding $40 million effort to help develop mRNA vaccines in Africa in coming years. 2023. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/bill-gates-foundation-africa-vaccines-mrna-institut-pasteur-biovac-fa28c0502925a4152df1709cc8f228fe (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Geller, D. E.; Crowley, C.; Froehlich, J.; Schwabe, C.; O’Carroll, M. WS10.03 Inhaled LUNAR®-CFTR mRNA (ARCT-032) is safe and well-tolerated: A phase 1 study. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2024, 23, S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, D. S.; Lieske, J. C.; Groothoff, J.; Schalk, G.; Russell, K.; Yu, S.; Vrhnjak, B. Nedosiran in primary hyperoxaluria subtype 3: Results from a phase I, single-dose study (PHYOX4). Urolithiasis 2023, 51(1), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Jiang, X.; Gui, S. RNA interference-based nanosystems for inflammatory bowel disease therapy. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 5287–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiolov, A. A.; Venkov, P. V.; Tsanev, R. G. Ribonucleic acids fractionation by density-gradient centrifugation and by agar gel electrophoresis: A comparison. Analytical Biochemistry 1966, 17(2), 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E. L.; Tang, S.; Kim, D.; Murray, A. M.; Swingle, K. L.; Hamilton, A. G.; Mrksich, K.; Padilla, M. S.; Palanki, R.; Li, J. J.; Mitchell, M. J. Peptide-Functionalized Lipid Nanoparticles for Targeted Systemic mRNA Delivery to the Brain. Nano Letters 2025, 25(2), 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, L. R.; Frey, W. H. Intranasal delivery bypasses the blood-brain barrier to target therapeutic agents to the central nervous system and treat neurodegenerative disease. BMC Neuroscience 2008, 9 Suppl 3, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, K. J.; Rajlic, I. L.; Bahl, K.; White, R.; Cowens, K.; Jacquinet, E.; Burke, K. E. mRNA vaccine trafficking and resulting protein expression after intramuscular administration. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2024, 35(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, A.; Juranek, S.; Brossart, P. Clinical and immunological effects of mRNA vaccines in malignant diseases. Molecular Cancer 2021, 20(1), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimeno, S.; Prados-Carvajal, R.; Fernández-Ávila, M. J.; Silva, S.; Silvestris, D. A.; Endara-Coll, M.; Rodríguez-Real, G.; Domingo-Prim, J.; Mejías-Navarro, F.; Romero-Franco, A.; Jimeno-González, S.; Barroso, S.; Cesarini, V.; Aguilera, A.; Gallo, A.; Visa, N.; Huertas, P. ADAR-mediated RNA editing of DNA:RNA hybrids is required for DNA double strand break repair. Nature Communications 2021, 12(1), 5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. H.; Androsavich, J. R.; So, N.; Jenkins, M. P.; MacCormack, D.; Prigodich, A.; Welch, V.; True, J. M.; Dolsten, M. Breaking the mold with RNA—a “RNAissance” of life science. Npj Genomic Medicine 2024, 9(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K.; Buckstein, M.; Ni, H.; Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: The impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 2005, 23(2), 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzmann, J. L.; Packard, C. J.; Chapman, M. J.; Katzmann, I.; Laufs, U. Targeting RNA With Antisense Oligonucleotides and Small Interfering RNA in Dyslipidemias: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 76(5), 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, Y. N. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine: First Approval. Drugs 2021a, 81(4), 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y. N. Inclisiran: First Approval. Drugs 2021b, 81(3), 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclair, N. K.; Brugiolo, M.; Park, S.; Devoucoux, M.; Urbanski, L.; Angarola, B. L.; Yurieva, M.; Anczuków, O. Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated TRA2β poison exon inclusion induces the expression of a lncRNA with anti-tumor effects. Nature Communications 2025, 16(1), 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Liu, T.; Yao, Z.; Hu, T.; Ji, X.; Yao, B. Harnessing stimuli-responsive biomaterials for advanced biomedical applications. Exploration 2024, 20230133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Dain, L.; Mei, L.; Zhu, G. Circular RNA: An emerging frontier in RNA therapeutic targets, RNA therapeutics, and mRNA vaccines. Journal of Controlled Release: Official Journal of the Controlled Release Society 2022, 348, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, M.; Zheng, A. Exosome-Based Carrier for RNA Delivery: Progress and Challenges. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15(2), Article 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Huang, Z.; Sun, F.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Kao, S.; Yang, G.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, S.; He, Y. The clinical effects of inclisiran, a first-in-class LDL-C lowering siRNA therapy, on the LDL-C levels in Chinese patients with hypercholesterolemia. Journal of Clinical Lipidology 2023, 17(3), 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, L.; Bettencourt, P. J. G. mRNA vaccines: A new opportunity for malaria, tuberculosis and HIV. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1172691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, H. S.; Moore, L. R.; Chopra, R.; Komlo, R.; McKenzie, M.; Blumenstein, K. G.; Zhao, H.; Kordasiewicz, H. B.; Shakkottai, V. G.; Paulson, H. L. Oligonucleotide therapy mitigates disease in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 mice. Annals of Neurology 2018, 84(1), 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, J. O.; Andrechek, E. R.; Wang, Y.; Viles, K. D.; Rempel, R. E.; Gilboa, E.; Sullenger, B. A.; Giangrande, P. H. Cell type-specific delivery of siRNAs with aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Nature Biotechnology 2006, 24(8), 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milewska, S.; Sadowska, A.; Stefaniuk, N.; Misztalewska-Turkowicz, I.; Wilczewska, A. Z.; Car, H.; Niemirowicz-Laskowska, K. Tumor-Homing Peptides as Crucial Component of Magnetic-Based Delivery Systems: Recent Developments and Pharmacoeconomical Perspective. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(11), 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. M.; Cudkowicz, M. E.; Genge, A.; Shaw, P. J.; Sobue, G.; Bucelli, R. C.; Chiò, A.; Van Damme, P.; Ludolph, A. C.; Glass, J. D.; Andrews, J. A.; Babu, S.; Benatar, M.; McDermott, C. J.; Cochrane, T.; Chary, S.; Chew, S.; Zhu, H.; Wu, F. VALOR and OLE Working Group. (2022). Trial of Antisense Oligonucleotide Tofersen for SOD1 ALS. The New England Journal of Medicine 387(12), 1099–1110. [CrossRef]

- Neves, K. B.; Rios, F. J.; Sevilla-Montero, J.; Montezano, A. C.; Touyz, R. M. Exosomes and the cardiovascular system: Role in cardiovascular health and disease. The Journal of Physiology 2023, 601(22), 4923–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E. W. M.; Shima, D. T.; Calias, P.; Cunningham, E. T.; Guyer, D. R.; Adamis, A. P. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 2006, 5(2), 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S. K. RNA Therapeutics: A Healthcare Paradigm Shift. Biomedicines 2023, 11(5), 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S. E.; Linnebjerg, H.; Shen, X.; Wolski, K.; Ma, X.; Lim, S.; Michael, L. F.; Ruotolo, G.; Gribble, G.; Navar, A. M.; Nicholls, S. J. Lepodisiran, an Extended-Duration Short Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a). JAMA 2023, 330(21), 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, S. E.; Wang, Q.; Nicholls, S. J.; Navar, A. M.; Ray, K. K.; Schwartz, G. G.; Szarek, M.; Stroes, E. S. G.; Troquay, R.; Dorresteijn, J. A. N.; Fok, H.; Rider, D. A.; Romano, S.; Wolski, K.; Rambaran, C. Zerlasiran—A Small-Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a): A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 332(23), 1992–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novartis. Novartis [WWW Document]. 2022. Available online: https://www.novartis.com/home (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Ouranidis, A.; Davidopoulou, C.; Tashi, R.-K.; Kachrimanis, K. Pharma 4.0 Continuous mRNA Drug Products Manufacturing. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13(9), 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovska, K.; Loughrey, D.; Dahlman, J. E. Drug delivery systems for RNA therapeutics. Nature Reviews Genetics 2022, 23(5), 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PhD, J. D. G. Novo Nordisk and Korro Bio Take RNA Editing to Cardiometabolic Diseases [WWW Document]. Inside Precision Medicine. 20 September 2024. Available online: https://www.insideprecisionmedicine.com/topics/precision-medicine/novo-nordisk-and-korro-bio-take-rna-editing-to-cardiometabolic-diseases/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Philippidis, A. Seven Biopharma Trends to Watch in 2025. GEN Edge 2025, 7(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirhaghi, M.; Mamashli, F.; Moosavi-Movahedi, F.; Arghavani, P.; Amiri, A.; Davaeil, B.; Mohammad-Zaheri, M.; Mousavi-Jarrahi, Z.; Sharma, D.; Langel, Ü.; Otzen, D. E.; Saboury, A. A. Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Promising Therapeutics and Drug-Delivery Systems for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2024, 21(5), 2097–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planté-Bordeneuve, V.; Perrain, V. Vutrisiran: A new drug in the treatment landscape of hereditary transthyretin amyloid polyneuropathy. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2024, 19(4), 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presnyak, V.; Alhusaini, N.; Chen, Y.-H.; Martin, S.; Morris, N.; Kline, N.; Olson, S.; Weinberg, D.; Baker, K. E.; Graveley, B. R.; Coller, J. Codon optimality is a major determinant of mRNA stability. Cell 2015, 160(6), 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, M. F.; Pan, H.; Yan, H.; Sandell, L. J.; Pham, C. T. N.; Wickline, S. A. Applications of RNA interference in the treatment of arthritis. Translational Research: The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine 2019, 214, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratni, H.; Ebeling, M.; Baird, J.; Bendels, S.; Bylund, J.; Chen, K. S.; Denk, N.; Feng, Z.; Green, L.; Guerard, M.; Jablonski, P.; Jacobsen, B.; Khwaja, O.; Kletzl, H.; Ko, C.-P.; Kustermann, S.; Marquet, A.; Metzger, F.; Mueller, B.; Mueller, L. Discovery of Risdiplam, a Selective Survival of Motor Neuron-2(SMN2) Gene Splicing Modifier for the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy(SMA). Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 61(15), 6501–6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandiran, V.; Kesharwani, A.; Anupriya; Bhaskaran, M.; Parihar, V. K.; Bakhshi, S.; Velayutham, R.; Kumarasamy, M. Overcoming biological barriers: Precision engineered extracellular vesicles for personalized neuromedicine. Precision Medicine and Engineering 2024, 1(2), 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikov, V.; Terenin, I.; Shepelkova, G.; Yeremeev, V.; Kolmykov, S.; Nagornykh, M.; Kolosova, E.; Sokolova, T.; Zaborova, O.; Kukushkin, I.; Kazakova, A.; Kunyk, D.; Kirshina, A.; Vasileva, O.; Seregina, K.; Pateev, I.; Kolpakov, F.; Ivanov, R. Untranslated Region Sequences and the Efficacy of mRNA Vaccines against Tuberculosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(2), 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, J.; Baek, W.; Seo, Y.; Kim, J. H. From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutics: Understanding MicroRNA-21 in Cancer. Cells 2022, 11(18), 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, F.; Chun, S. J.; Norris, D. A.; Hung, G.; Lee, S.; Matson, J.; Fey, R. A.; Gaus, H.; Hua, Y.; Grundy, J. S.; Krainer, A. R.; Henry, S. P.; Bennett, C. F. Pharmacology of a central nervous system delivered 2’-O-methoxyethyl-modified survival of motor neuron splicing oligonucleotide in mice and nonhuman primates. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2014, 350(1), 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, T. C.; Langer, R.; Wood, M. J. A. Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2020, 19(10), 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, S.; Zuckerman, J.; Dorgan, D.; Lascano, J.; McCoy, K.; Jain, M.; Schechter, M.; Lommatzsch, S.; Indihar, V.; Lechtzin, N.; Mcbennett, K.; Callison, C.; Brown, C.; Liou, T.; Macdonald, K.; Nasr, S.; Bodie, S.; Vaughn, M.; Meltzer, E.; Barbier, A. Inhaled mRNA therapy for treatment of cystic fibrosis: Interim results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1/2 clinical study. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis: Official Journal of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupaimoole, R.; Slack, F. J. MicroRNA therapeutics: Towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2017, 16(3), 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Pilipich, N.; Beloki, U.; Salaberry, L.; Smerdou, C. Self-Amplifying RNA: A Second Revolution of mRNA Vaccines against COVID-19. Vaccines 2024, 12(3), 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Mehra, A.; Arora, S.; Gugulothu, D.; Vora, L. K.; Prasad, R.; Khatri, D. K. Exosome-mediated delivery and regulation in neurological disease progression. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 264, 130728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; Videira, M. Dual Approaches in Oncology: The Promise of siRNA and Chemotherapy Combinations in Cancer Therapies. Onco 2025, 5(1), Article 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, A. L.; Kordasiewicz, H. B.; Langbehn, D.; Skotte, N. H.; Parsons, M. P.; Villanueva, E. B.; Caron, N. S.; Østergaard, M. E.; Anderson, L. M.; Xie, Y.; Cengio, L. D.; Findlay-Black, H.; Doty, C. N.; Fitsimmons, B.; Swayze, E. E.; Seth, P. P.; Raymond, L. A.; Frank Bennett, C.; Hayden, M. R. Huntingtin suppression restores cognitive function in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Science Translational Medicine 2018, 10(461), eaar3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparmann, A.; Vogel, J. RNA-based medicine: From molecular mechanisms to therapy. The EMBO Journal 2023, 42(21), e114760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Setrerrahmane, S.; Li, C.; Hu, J.; Xu, H. Nucleic acid drugs: Recent progress and future perspectives. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Hou, Y.; Huang, W.; Xie, G.; Yang, W.; Zhang, R. Improved RNA base editing with guide RNAs mimicking highly edited endogenous ADAR substrates. Nature Biotechnology 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svitkin, Y. V.; Cheng, Y. M.; Chakraborty, T.; Presnyak, V.; John, M.; Sonenberg, N. N1-methyl-pseudouridine in mRNA enhances translation through eIF2α-dependent and independent mechanisms by increasing ribosome density. Nucleic Acids Research 2017, 45(10), 6023–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, Y. Y. Nedosiran: First Approval. Drugs 2023, 83(18), 1729–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejedor, S.; Wågberg, M.; Correia, C.; Åvall, K.; Hölttä, M.; Hultin, L.; Lerche, M.; Davies, N.; Bergenhem, N.; Snijder, A.; Marlow, T.; Dönnes, P.; Fritsche-Danielson, R.; Synnergren, J.; Jennbacken, K.; Hansson, K. The Combination of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGF-A) and Fibroblast Growth Factor 1 (FGF1) Modified mRNA Improves Wound Healing in Diabetic Mice: An Ex Vivo and In Vivo Investigation. Cells 2024, 13(5), Article 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenforde, M. W.; Olson, S. M.; Self, W. H.; Talbot, H. K.; Lindsell, C. J.; Steingrub, J. S.; Shapiro, N. I.; Ginde, A. A.; Douin, D. J.; Prekker, M. E.; Brown, S. M.; Peltan, I. D.; Gong, M. N.; Mohamed, A.; Khan, A.; Exline, M. C.; Files, D. C.; Gibbs, K. W.; Stubblefield, W. B.; HAIVEN Investigators. Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna Vaccines Against COVID-19 Among Hospitalized Adults Aged ≥65 Years—United States, January-March 2021. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2021, 70(18), 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, P.; Wiggins, J. F.; Daige, C. L.; Cho, C.; Omotola, M.; Brown, D.; Weidhaas, J. B.; Bader, A. G.; Slack, F. J. Systemic delivery of tumor suppressor microRNA mimics using a neutral lipid emulsion inhibits lung tumors in mice. Molecular Therapy: The Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 2011, 19(6), 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, K.; Hekmatara, T.; Herbert, E.; Kreuter, J. Transferrin-and transferrin-receptor-antibody-modified nanoparticles enable drug delivery across the blood–brain barrier (BBB). European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2009, 71(2), 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallina, N. S.; McRae, E. K. S.; Geary, C.; Andersen, E. S. An RNA origami robot that traps and releases a fluorescent aptamer. Science Advances 2024, 10(12), eadk1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rooij, E.; Kauppinen, S. Development of microRNA therapeutics is coming of age. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2014, 6(7), 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilis, T.; Stamoula, E.; Ainatzoglou, A.; Sachinidis, A.; Lamprinou, M.; Dardalas, I.; Vizirianakis, I. S. mRNA in the Context of Protein Replacement Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15(1), 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, T. A.; Crooke, S. T. Antisense oligonucleotides capable of promoting specific target mRNA reduction via competing RNase H1-dependent and independent mechanisms. PloS One 2014, 9(10), e108625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J. S.; Carlino, M. S.; Khattak, A.; Meniawy, T.; Ansstas, G.; Taylor, M. H.; Kim, K. B.; McKean, M.; Long, G. V.; Sullivan, R. J.; Faries, M.; Tran, T. T.; Cowey, C. L.; Pecora, A.; Shaheen, M.; Segar, J.; Medina, T.; Atkinson, V.; Gibney, G. T.; Zaks, T. Individualised neoantigen therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab monotherapy in resected melanoma (KEYNOTE-942): A randomised, phase 2b study. The Lancet 2024, 403(10427), 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.-S.; Thota, N.; John, G.; Chang, E.; Lee, S.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Mei, K.-C. Enhancing RNA-lipid nanoparticle delivery: Organ-and cell-specificity and barcoding strategies. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 375, 366–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, J.; Zwolinski, C.; Denis, C.; Maughan, M.; Hayles, L.; Clarke, D.; Snare, M.; Liao, H.; Chiou, S.; Marmura, T.; Zoeller, H.; Hudson, B.; Peart, J.; Johnson, M.; Karlsson, A.; Wang, Y.; Nagle, C.; Harris, C.; Tonkin, D.; Johnson, M. R. Development of mRNA manufacturing for vaccines and therapeutics: mRNA platform requirements and development of a scalable production process to support early phase clinical trials. Translational Research 2022, 242, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, M. N.; Smolke, C. D. A modular and extensible RNA-based gene-regulatory platform for engineering cellular function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007, 104(36), 14283–14288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gong, F.; Golubovic, A.; Strilchuk, A.; Chen, J.; Zhou, M.; Dong, S.; Seto, B.; Li, B. Rational design and modular synthesis of biodegradable ionizable lipids via the Passerini reaction for mRNA delivery. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2025, 122(5), e2409572122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Okada, S.; Sakurai, M. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing in neurological development and disease. RNA Biology 2021, 18(7), 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, T.; Qi, X.; Yan, H.; Chang, Y. RNA Origami Functions as a Self-Adjuvanted Nanovaccine Platform for Cancer Immunotherapy. ACS Nano 2024, 18(5), 4056–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J. Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: Current potential and challenges. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 2017, 16(3), 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.-J. Advances in machine-learning approaches to RNA-targeted drug design. Artificial Intelligence Chemistry 2024, 2(1), 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).