Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Biomass Measurement

2.3.2. Measurement of Photosynthetic Characteristics

2.3.3. Measurement of Physiological Indicators

2.3.4. NPK Content Estimation

2.3.5. Biochemical Analysis Assays

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

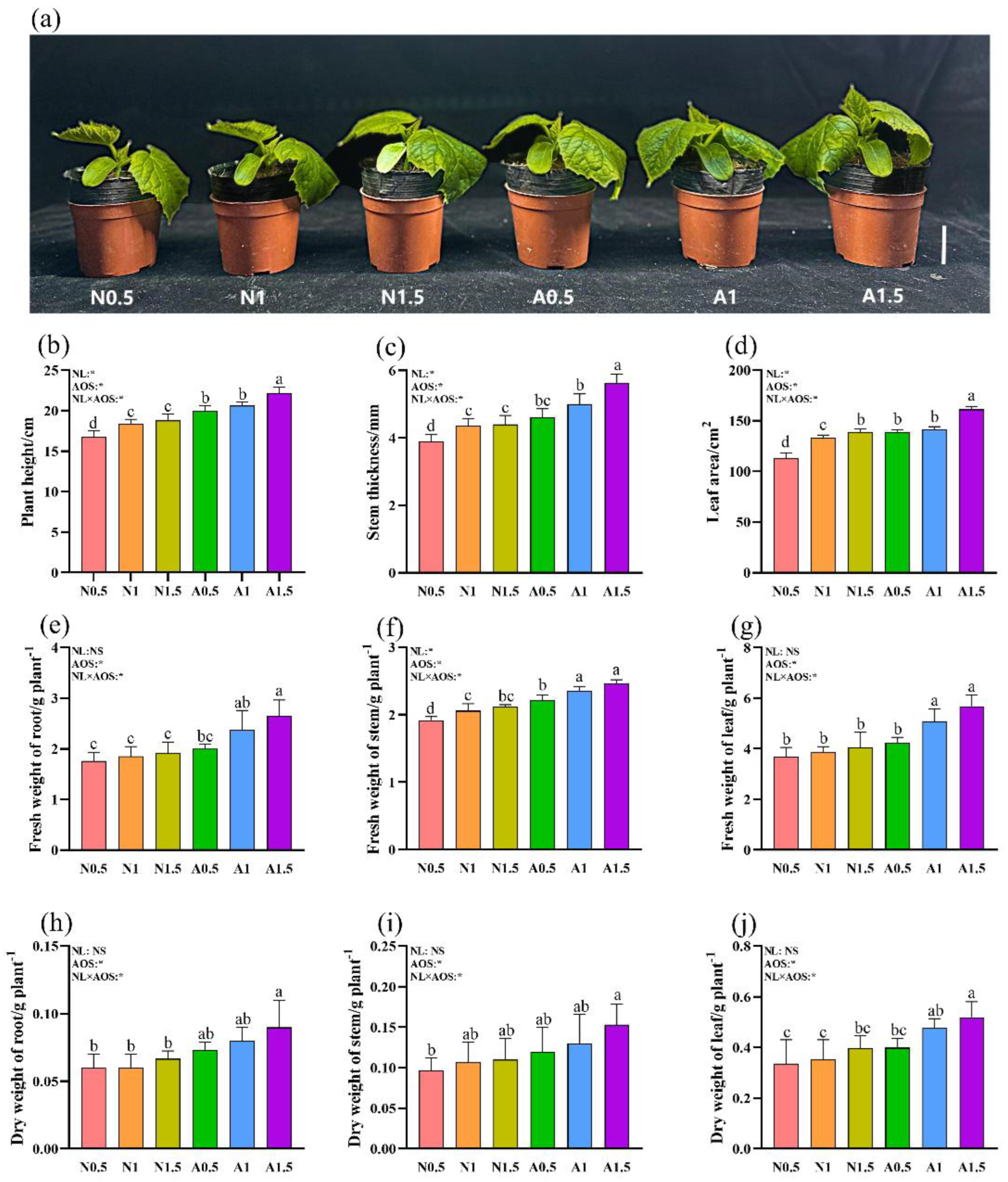

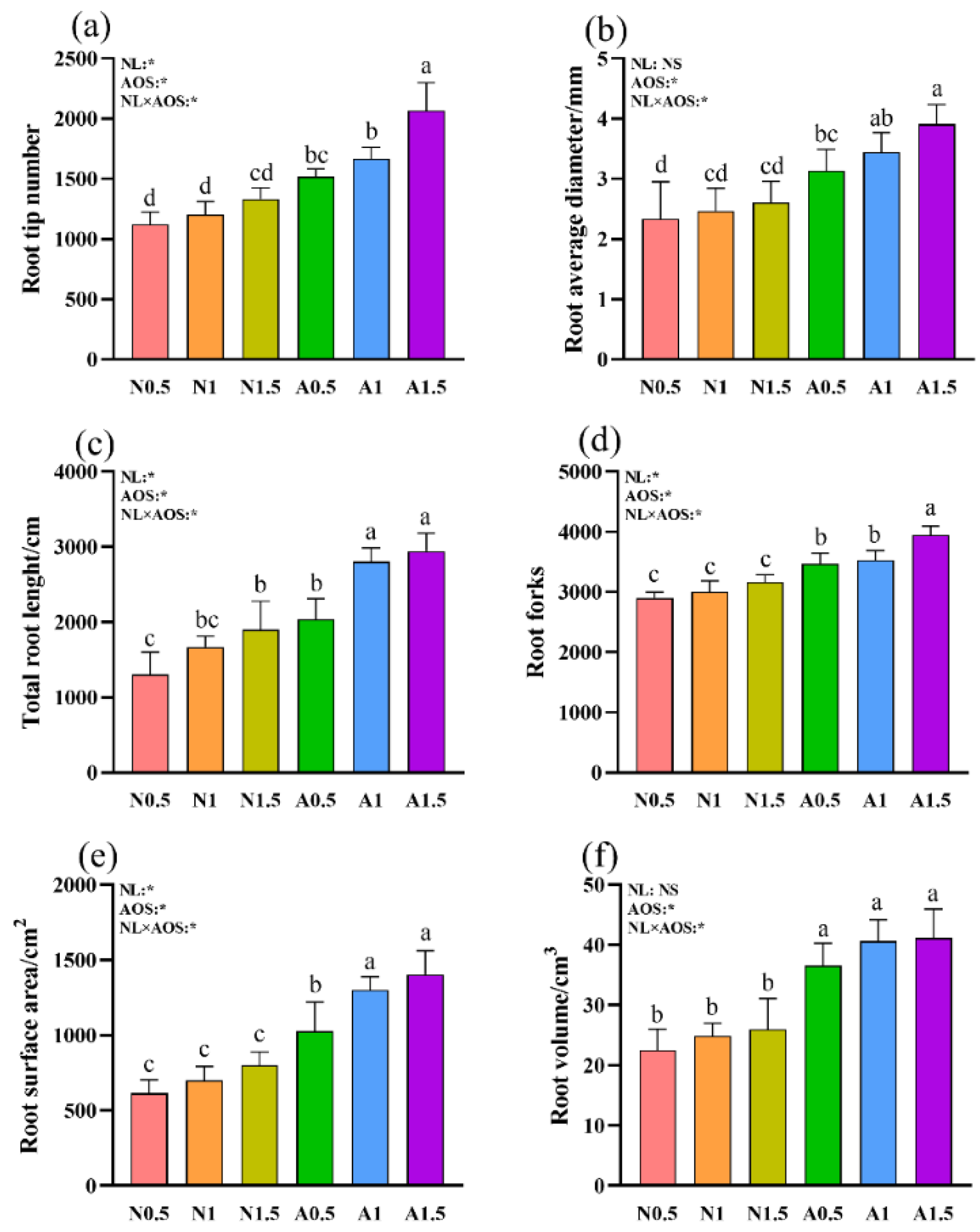

3.1. Effects of Different Nutrient Solution Concentration with AOS on the Growth of Cucumber Seedlings under Suboptimal Temperature

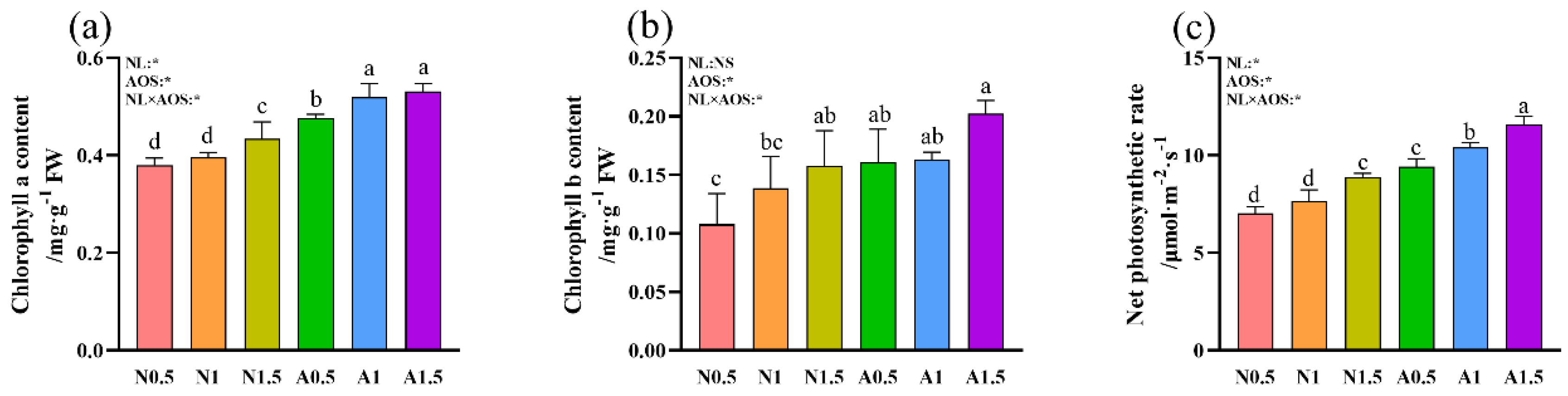

3.2. Effects of AOS and Different Nutrient Solution Levels on the Chlorophyll Content and Net Photosynthetic rate of Cucumber Seedlings Under Suboptimal Temperature

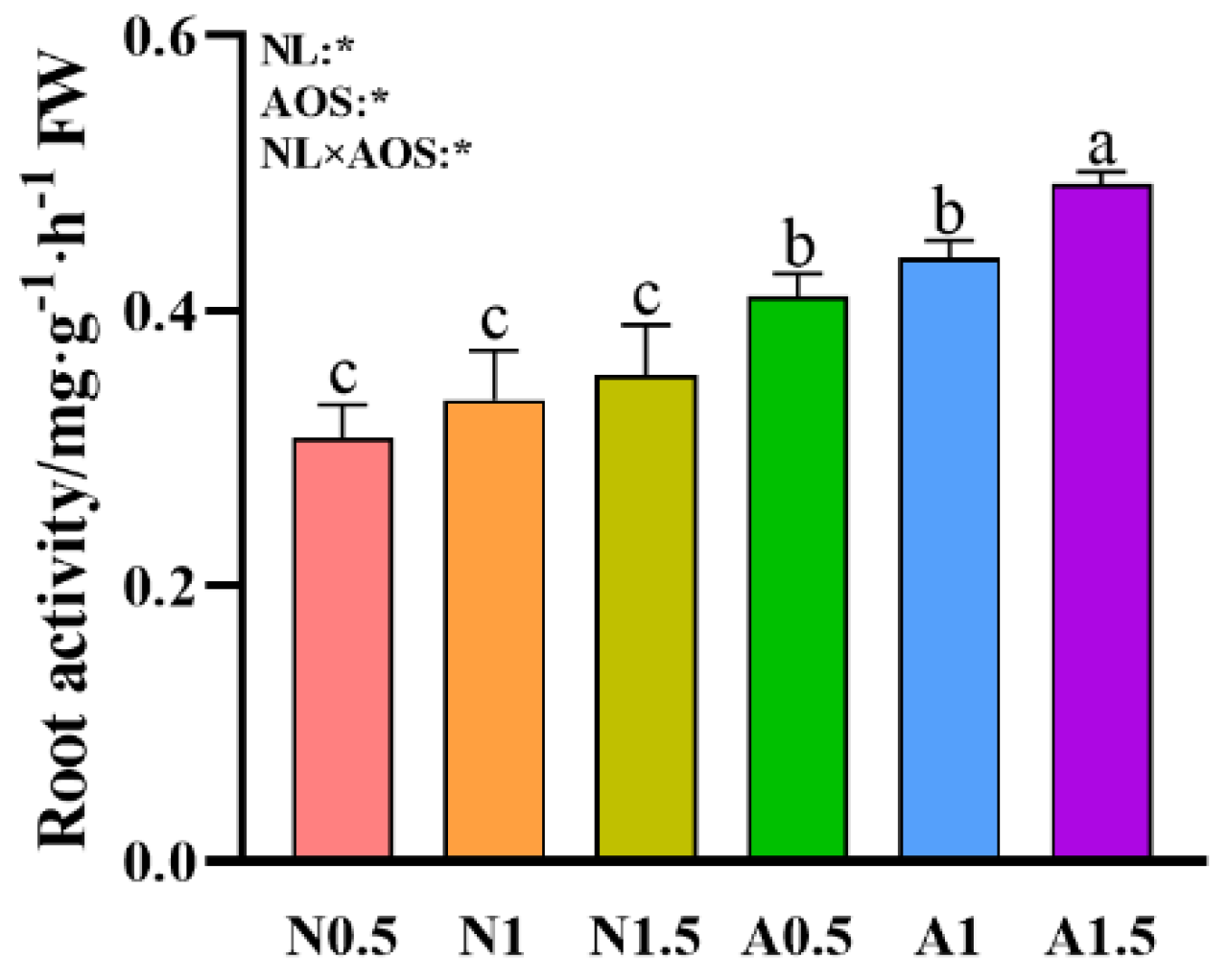

3.3. Effects of AOS and Different Nutrient Solution Levels on the Root Activity of Cucumber Seedlings Under Suboptimal Temperature

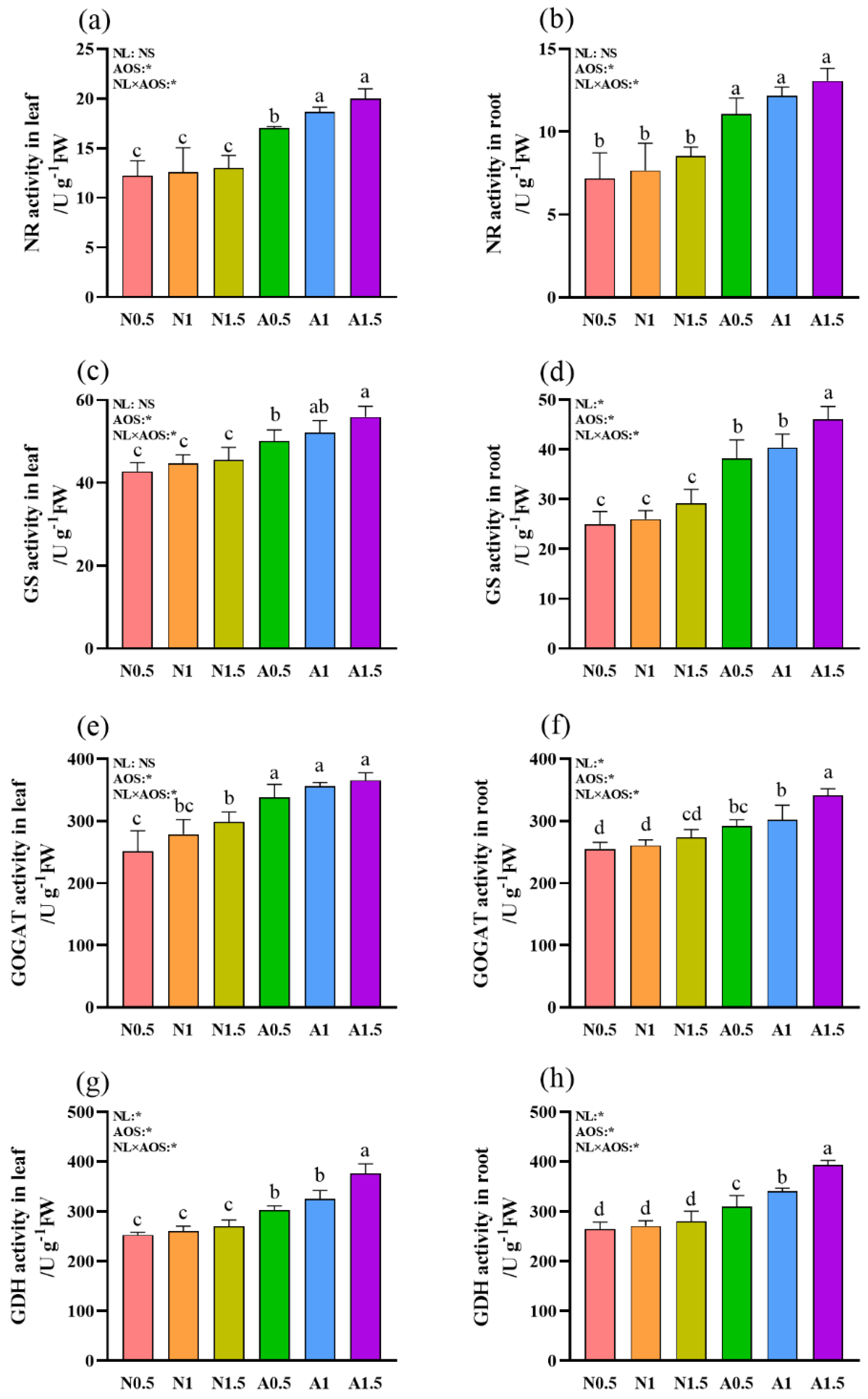

3.4. Effects of AOS and Different Nutrient Solution Levels on the Nitrogen Metabolism Enzymes Activities in Cucumber Seedlings Under Suboptimal Temperature

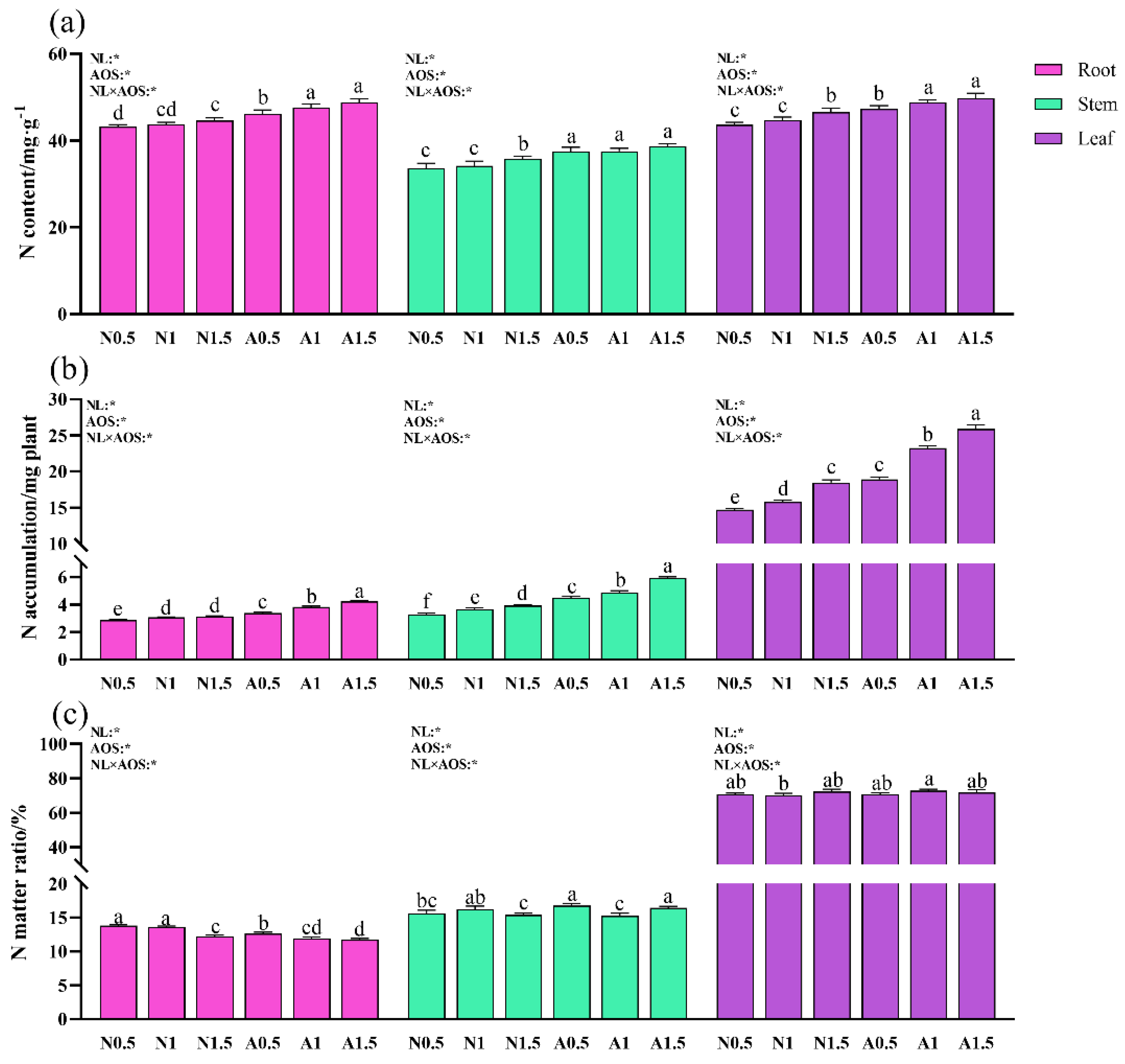

3.5. Effects of AOS and Different Nutrient Solution Levels on Nitrogen Content, Accumulation, and Distribution in Different Cucumber Organs Under Suboptimal Temperature

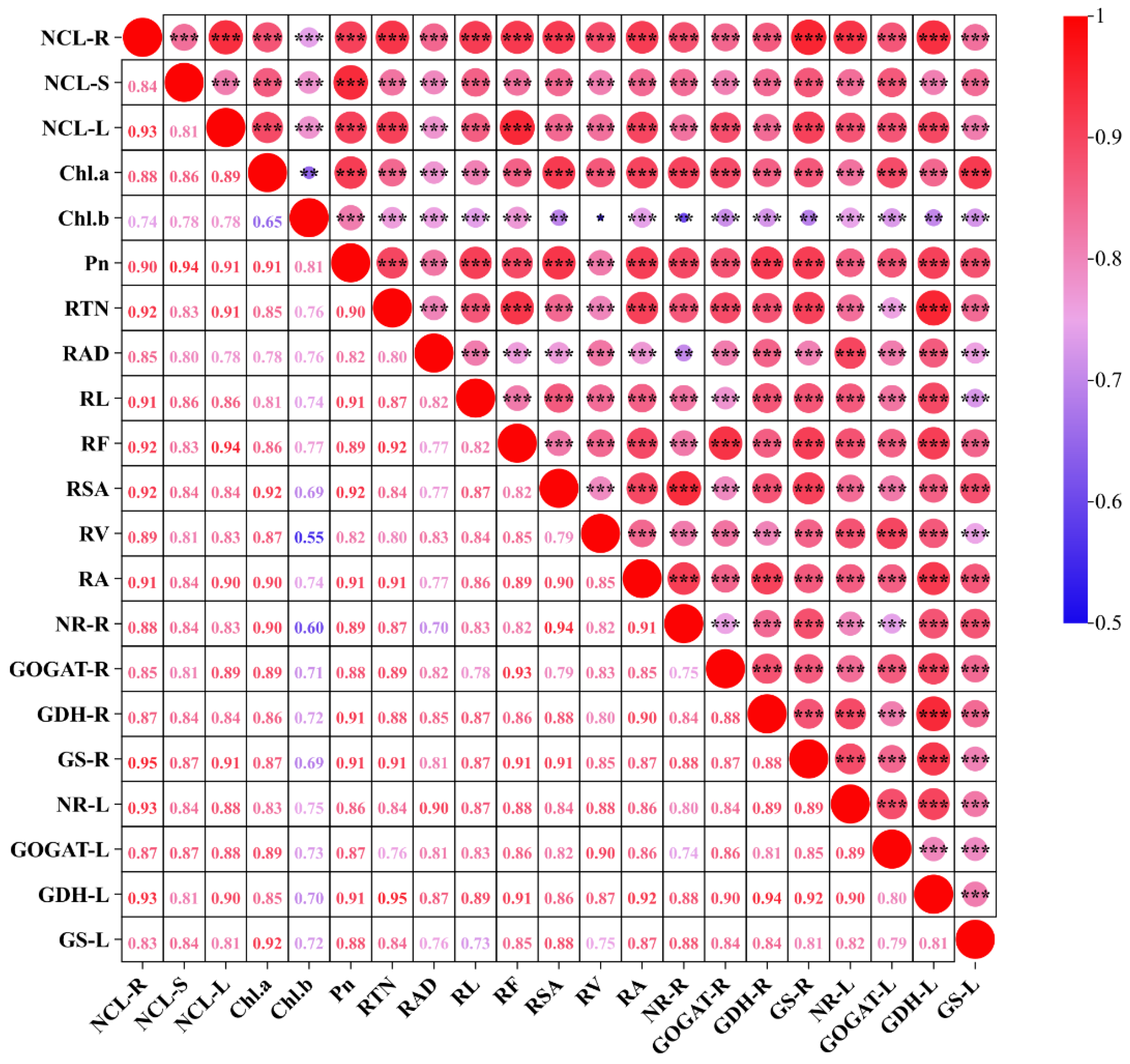

3.6. Correlation Analysis Between Different Traits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOS | Alginate oligosaccharides |

| NR | Nitrate reductase |

| GOGAT | Glutamate synthase |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase |

| GDH | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| NL | Nutrient level |

| NCL-R | Nitrogen content in root |

| NCL-S | Nitrogen content in stem |

| NCL-L | Nitrogen content in leaf |

| Chl. a | Chlorophyll a content |

| Chl. b | Chlorophyll b content |

| Pn | Net photosynthetic rate |

| RTN | Root tip number |

| RAD | Root average diameter |

| RL | Total root length |

| RF | Root forks |

| RSA | Root surface area |

| RV | Root volume |

| RA | Root activity |

| NR-R | Nitrate reductase activity in root |

| GOGAT-R | Glutamate synthase activity in root |

| GDH-R | Glutamate dehydrogenase activity in root |

| GS-R | Glutamine synthetase in root. |

| NR-L | Nitrate reductase activity in leaf |

| GOGAT-L | Glutamate synthase activity in leaf |

| GDH-L | Glutamate dehydrogenase activity in leaf |

| GS-L | Glutamine synthetase in leaf |

| NUE | Nitrogen use efficiency |

References

- Aslam, M.; Fakher, B.; Ashraf, M.A.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, B.; Qin, Y. Plant low-temperature stress: Signaling and response. Agronomy 2022, 12, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajihashemi, S.; Noedoost, F.; Geuns, J.M.C.; Djalovic, I.; Siddique, K.H.M. Effect of cold stress on photosynthetic traits, carbohydrates, morphology, and anatomy in nine cultivars of stevia rebaudiana. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Duan, Z.; Mao, J.; Li, X.; Dong, F. Effects of root-zone temperature and N, P, and K supplies on nutrient uptake of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seedlings in hydroponics. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2012, 58, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, M.; Abdolahipour, B. Rootzone temperature on nitrogen absorption and some physiological traits in cucumber. Journal of Plant Process and Function 2020, 8, 51–59. Available online: https://sid.ir/paper/768371/en.

- Yan, Q.; Duan, Z.; Mao, J.; Li, X.; Dong, F. Low root zone temperature limits nutrient effects on cucumber seedling growth and induces adversity physiological response. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2013, 12, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Addabbo, T.; Laquale, S.; Perniola, M.; Candido, V. Biostimulants for plant growth promotion and sustainable management of phytoparasitic nematodes in vegetable crops. Agronomy 2019, 9, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Pan, T.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C. Metabolic responses to combined water deficit and salt stress in maize primary roots. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2021, 20, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Shahzad, B.; Sharma, A.; Khan, E.A. 24-Epibrassinolide application in plants: An implication for improving drought stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2019, 135, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Aziz, T.; Hussain, I.; Ramzani, P.M.A.; Reichenauer, T.G. Silicon: a beneficial nutrient for maize crop to enhance photochemical efficiency of photosystem II under salt stress. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 2016, 63, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Hanif, M.; Abideen, Z.; Sohail, M.; El-Keblawy, A.; Radicetti, E.; Mancinelli, R.; Haider, G. Mechanisms and strategies of plant microbiome interactions to mitigate abiotic stresses. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Maheshwari, D.K. Use of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) with multiple plant growth promoting traits in stress agriculture: Action mechanisms and future prospects. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 156, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Yi, B.; Everaert, N. Alginate oligosaccharides preparation, biological activities and their application in livestock and poultry. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2021, 20, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Rauf, A.; Khalil, A. A.; Shan, Z.; Chen, C.; Rengasamy, K. R.R.; Wan, C. Process and applications of alginate oligosaccharides with emphasis on health beneficial perspectives. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2021, 63, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Han, Y.; Han, W.; Yang, Y.; Saito, M.; Lv, G.; Song, J.; Bai, W. Different oligosaccharides induce coordination and promotion of root growth and leaf senescence during strawberry and cucumber growth. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Yang, L.; Cao, R.; Ye, X. Integrated physiological and transcriptomic analyses revealed improved cold tolerance in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) by exogenous chitosan oligosaccharide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibaeva, T.G.; Sherudilo, E.G.; Titov, A.F. Response of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) plants to prolonged permanent and short-term daily exposures to chilling temperature. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology 2018, 65, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Deng, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, X.; Li, Y. Gibberellin is involved in inhibition of cucumber growth and nitrogen uptake at suboptimal root-zone temperatures. Plos One 2016, 11, e0156188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.L.; Sheard, R.W.; Moyer, J.R. Comparison of conventional and automated procedures for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium analysis of plant material using a single digestion. Agron. J. 1967, 59, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of Plant Physiology 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemensson-Lindell, A. Triphenyltetrazolium chloride as an indicator of fine-root vitality and environmental stress in coniferous forest stands: Applications and limitations. Plant Soil 1994, 159, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkelish, A.; Alhudhaibi, A.M.; Hossain, A.S.; Haouala, F.; Alharbi, B.M.; El, B.M.F.; Badji, A.; AlJwaizea, N.I.; Sayed, A.A.S. Alleviating chromium-induced oxidative stress in Vigna radiata through exogenous trehalose application: Insights into growth, photosynthetic efficiency, mineral nutrient uptake, and reactive oxygen species scavenging enzyme activity enhancement. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, H.R.; Taha, M.A.; Dessoky, E.S.; Selem, E. Exploring the perspectives of irradiated sodium alginate on molecular and physiological parameters of heavy metal stressed Vigna radiata L. plants. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2023, 29, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Qi, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H. Research on the mechanisms of phytohormone signaling in regulating root development. Plants 2024, 13, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zeng, R.; Liao, H. Improving crop nutrient efficiency through root architecture modifications. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2016, 58, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, K.; Matsubara, Y. Purification of alginate oligosaccharides with root growth-promoting activity toward lettuce. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000, 64, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Du, Y.; He, A.; Sun, K. The promoting effects of alginate oligosaccharides on root development in Oryza sativa L. mediated by auxin signaling. Carbohydr Polym. 2014, 113, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shen, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wang, P.; Jiang, X. Growth stimulation activity of alginate-derived oligosaccharides with different molecular weights and mannuronate/guluronate ratio on Hordeum vulgare L. J Plant Growth Regul 2021, 40, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Heng, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Du, Y. Nitric oxide mediates alginate oligosaccharides-induced root development in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013, 71, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Zhang, X.; Chen, P.; Du, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, F.; Yong, T.; Yang, W. Improving maize's N uptake and N use efficiency by strengthening roots' absorption capacity when intercropped with legumes. Peer J 2021, 9, e11658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Weng, B.; Cai, B.; Dong, Y.; Yan, C. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation and phosphorus supply on the growth and nutrient uptake of Kandelia obovata (Sheue, Liu & Yong) seedlings in autoclaved soil. Applied Soil Ecology 2014, 75, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Chu, C. Nitrogen assimilation in plants: Current status and future prospects. J Genet Genomics 2022, 49, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.Q.; Crawford, N.M. Identification and characterization of a chlorate-resistant mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana with mutations in both nitrate reductase structural genes NIA1 and NIA2. Molec. Gen. Genet. 1993, 239, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhang, A.; Yang, S.; Shang, L.; Wang, D.; Ruan, B.; Liu, C.; Jiang, H.; Dong, G.; Zhu. L.; Hu, J.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, D.; Guo, L.; Xu, G.; Teng, S.; Harberd, N.P.; Qian, Q. The indica nitrate reductase gene OsNR2 allele enhances rice yield potential and nitrogen use efficiency. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5207. [CrossRef]

- Redinbaugh, M.G.; Campbell, W.H. Glutamine synthetase and ferredoxin-dependent glutamate synthase expression in the maize (Zea mays) root primary response to nitrate (evidence for an organ-specific response). Plant Physiol. 1993, 101, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinsi, B.; Espen, L. Mineral nitrogen sources differently affect root glutamine synthetase isoforms and amino acid balance among organs in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, S.; Meng, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yu, M.; Ma, X. Nitrogen regulating the expression and localization of four glutamine synthetase isoforms in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Oliveira, R.; Oliveira, I.C.; Coruzzi, G.M. Arabidopsis mutant analysis and gene regulation define a nonredundant role for glutamate dehydrogenase in nitrogen assimilation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996, 93, 4718–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiao, B.; Wang, J.; Zhao, P.; Dong, F.; Yang, F.; Ma, C.; Guo, P.; Zhou, S. Identification of wheat glutamate synthetase gene family and expression analysis under nitrogen stress. Genes 2024, 15, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Lawlor, D.W.; Paul, M.J.; Pan, W. Exogenous trehalose improves growth under limiting nitrogen through upregulation of nitrogen metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kchikich, A.; Roussi, Z.; Krid, A.; Nhhala, N.; Ennoury, A.; Benmrid, B.; Kounnoun, A.; Maadoudi, M.E.; Nhiri, N.; Mohamed, N. Effects of mycorrhizal symbiosis and Ulva lactuca seaweed extract on growth, carbon/nitrogen metabolism, and antioxidant response in cadmium-stressed sorghum plant. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2024, 30, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, Tariq; Khan, M. Masroor A.; Idrees, M.; Naeem, M.; Moinuddin; Hashmi, Nadeem; Varshney, Lalit. Enhancing the growth, photosynthetic capacity and artemisinin content in Artemisia annua L. by irradiated sodium alginate. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2011, 80, 833-836. [CrossRef]

- Sarfaraz, Adeeba; Naeem, M.; Nasir, Shafia; Idrees, Mohd; Aftab, Tariq; Hashmi, Nadeem; Khan, M. Masroor; Moinuddin; Varshney, Lalit. An evaluation of the effects of irradiated sodium alginate on the growth, physiological activities and essential oil production of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.). J. Med. Plant. Res. 2011, 5, 15-21. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/JMPR/article-full-text-pdf/3F390BE15764.

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.; Zhao, X.; Du, Y. Alginate oligosaccharides regulate nitrogen metabolism via calcium in Brassica campestris L. var. utilis Tsen et Lee. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2013, 88, 502-508. [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.J.; Canvin, D.T.; Sherrard, J.H.; Hageman, R.H. Assimilation of [15N] nitrate and of [15N] nitrite in leaves of five plant species under light and dark conditions. Plant Physiol 1983, 71, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, P.; Geiger, M.; Walch-Liu, P.; Engels, C.; Krapp, A.; Stitt, M. Elevated carbon dioxide increases nitrate uptake and nitrate reductase activity when tobacco is growing on nitrate, but increases ammonium uptake and inhibits nitrate reductase activity when tobacco is growing on ammonium nitrate. Plant Cell Environ 2001, 24, 1119–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, P.; Geiger, M.; Walch-Liu, P.; Engels, C.; Krapp, A.; Stitt, M. The immediate cause of the diurnal changes of nitrogen metabolism in leaves of nitrate-replete tobacco: a major imbalance between the rate of nitrate reduction and the rates of nitrate uptake and ammonium metabolism during the first part of the light period. Plant Cell Environ 2001, 24, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Stitt, M. Metabolic and signaling aspects underpinning the regulation of plant carbon nitrogen interactions. Mol Plant 2010, 3, 973–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Long, S.; Ort, D.R. What is the maximum efficiency with which photosynthesis can convert solar energy into biomass? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2008, 19, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.; Khan, W.; Khan, M.Z.; Gitari, H.I.; Gbolayori, G.F.; Moussa, A.A.; Mandozai, A.; Rizwan, N.; Anwari, G.; Maroof, S.M. Photosynthetic activities and photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency of maize crop under different planting patterns and nitrogen fertilization. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2021, 21, 2274–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tian, P.; Christensen, M.J.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Nan, Z. Effect of Epichloë gansuensis endophyte on the activity of enzymes of nitrogen metabolism, nitrogen use efficiency and photosynthetic ability of Achnatherum inebrians under various NaCl concentrations. Plant Soil 2019, 435, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, H.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Du, Y.; Wu, L. Enhancement in photosynthesis characteristics and phytohormones of flowering Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris L. var. utilis Tsen et Lee) by exogenous alginate oligosaccharides. Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment 2013, 11, 669-675. Available online: http://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=27243252.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).