Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

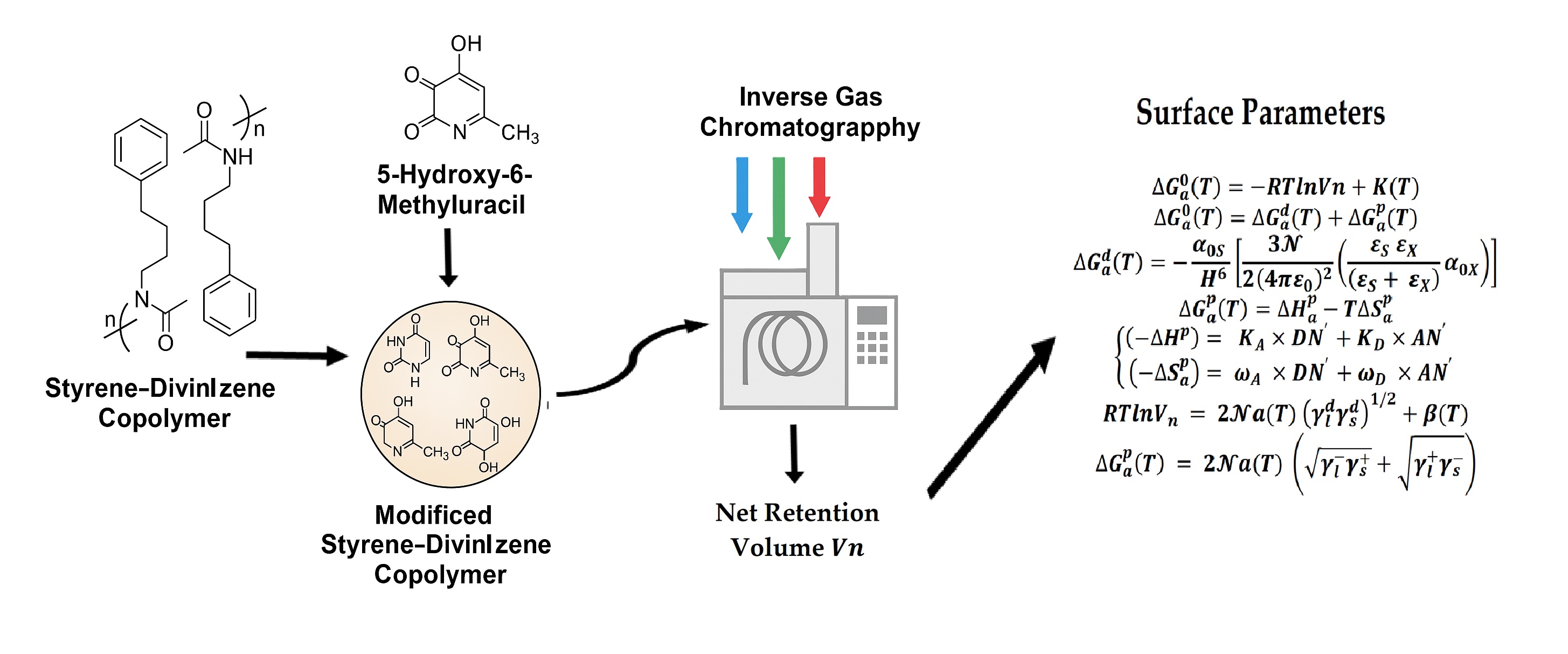

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Adsorbent and Materials

2.2. Inverse Gas Chromatography

2.3. Thermodynamic Methods

2.3.1. Dispersive and Polar Energies, and Lewis Acid–Base Parameters

2.3.2. London Dispersive Surface Energy, and Lewis Acid–Base Surface Energies

3. Results

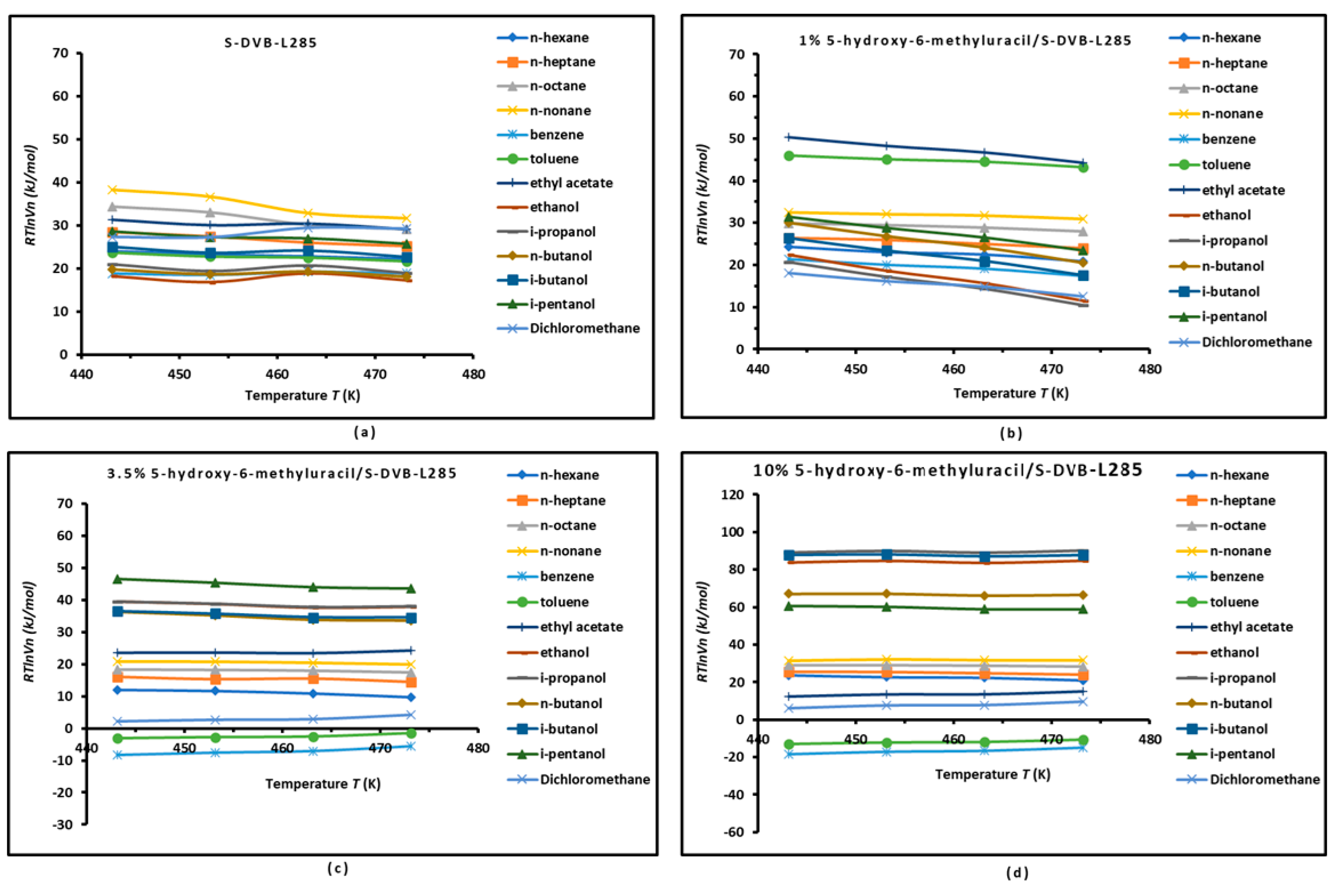

3.1. Variations of the Free Energy of Adsorption

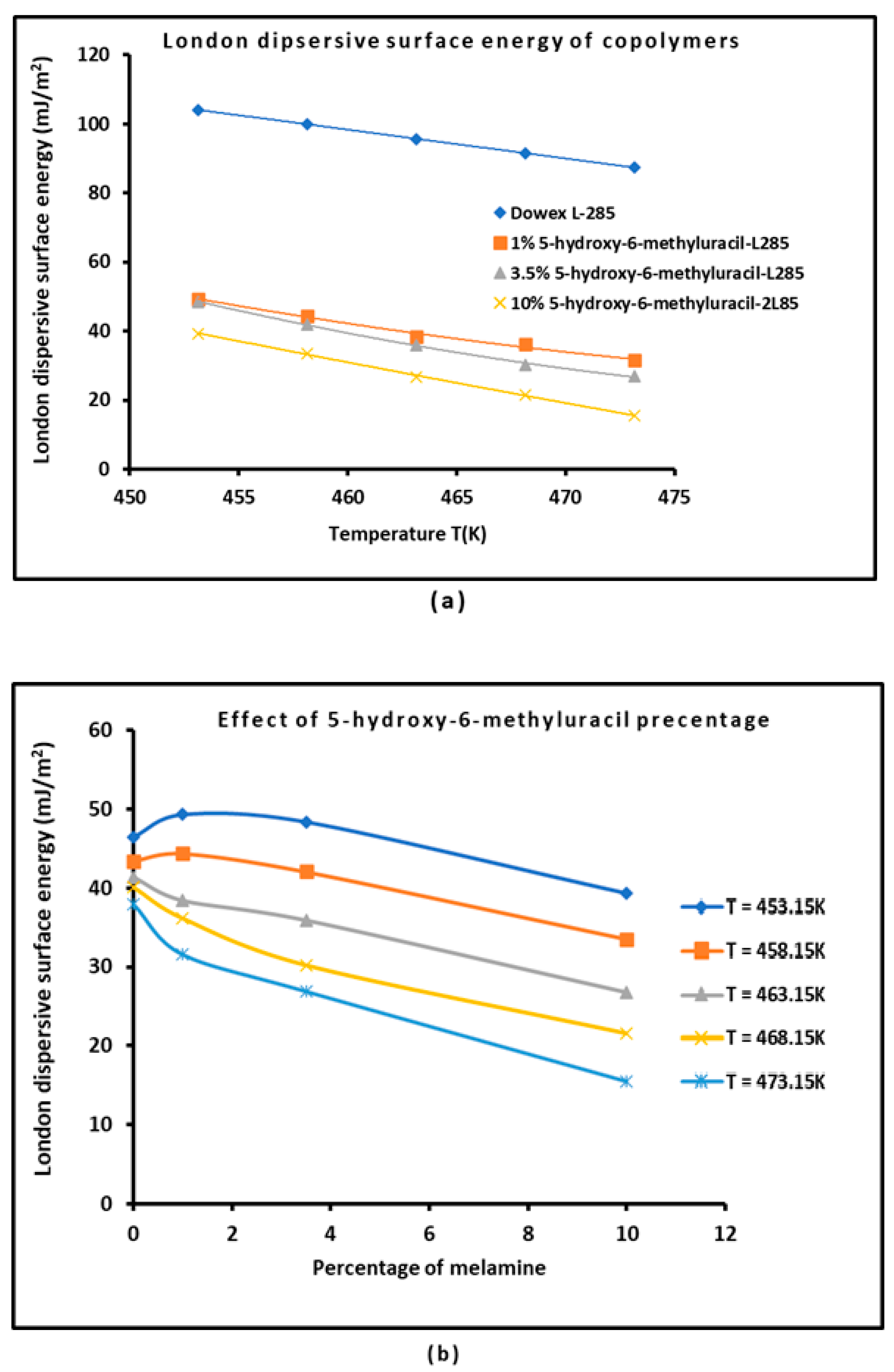

3.2. London Dispersive Surface Energy of the System S-DVB-L285 with Different Percentages 5-hydroxy-6-methyluracil Percentages

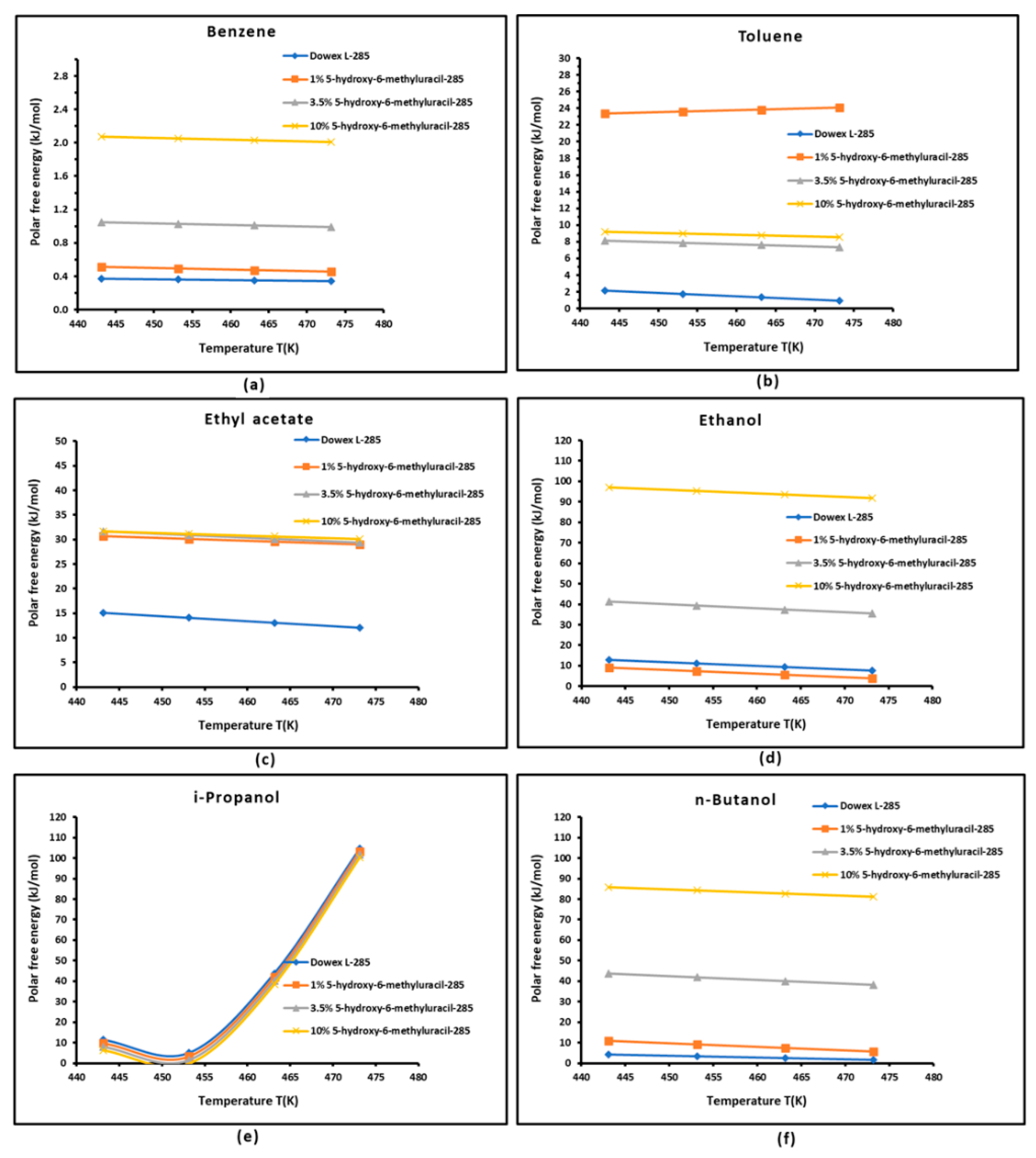

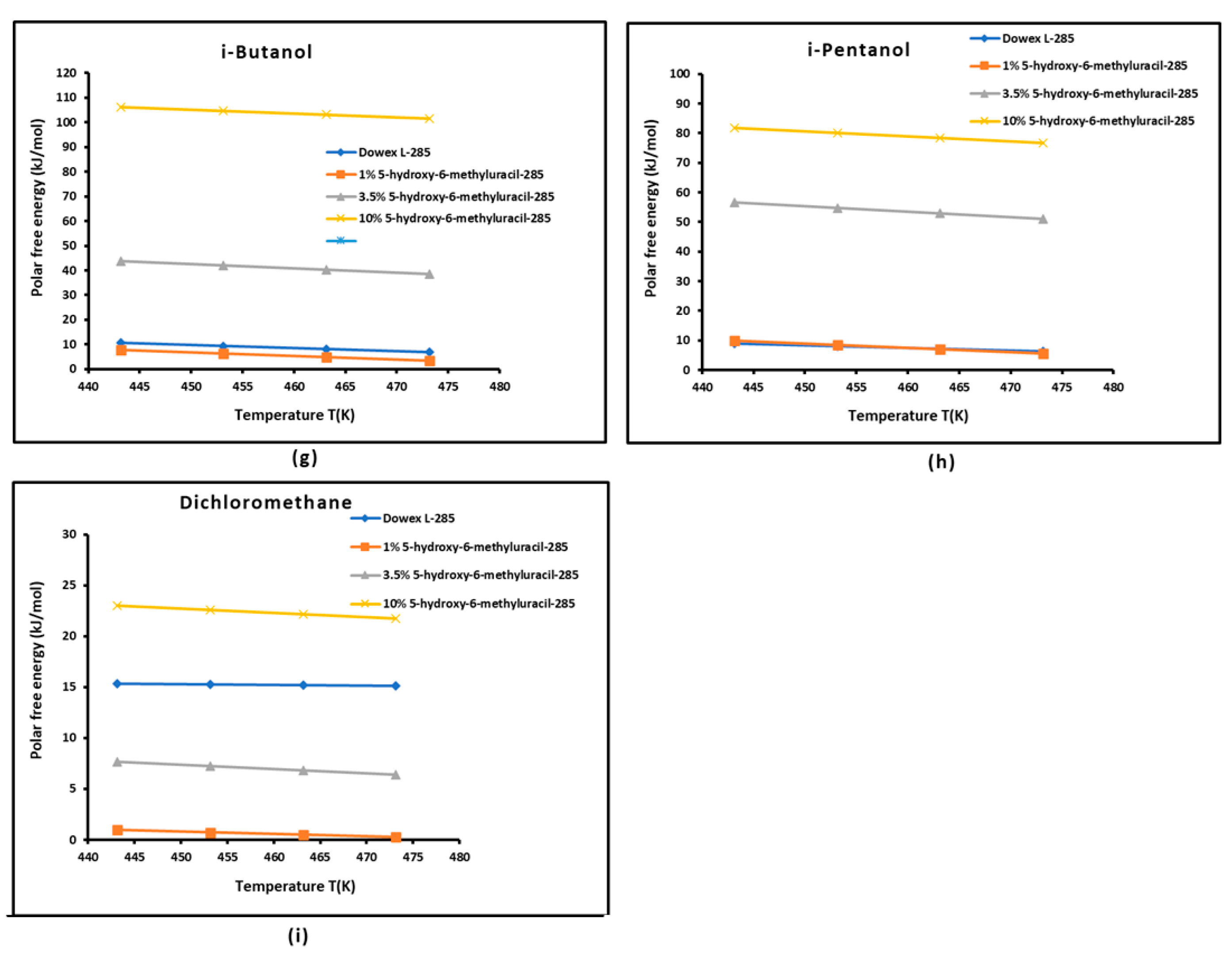

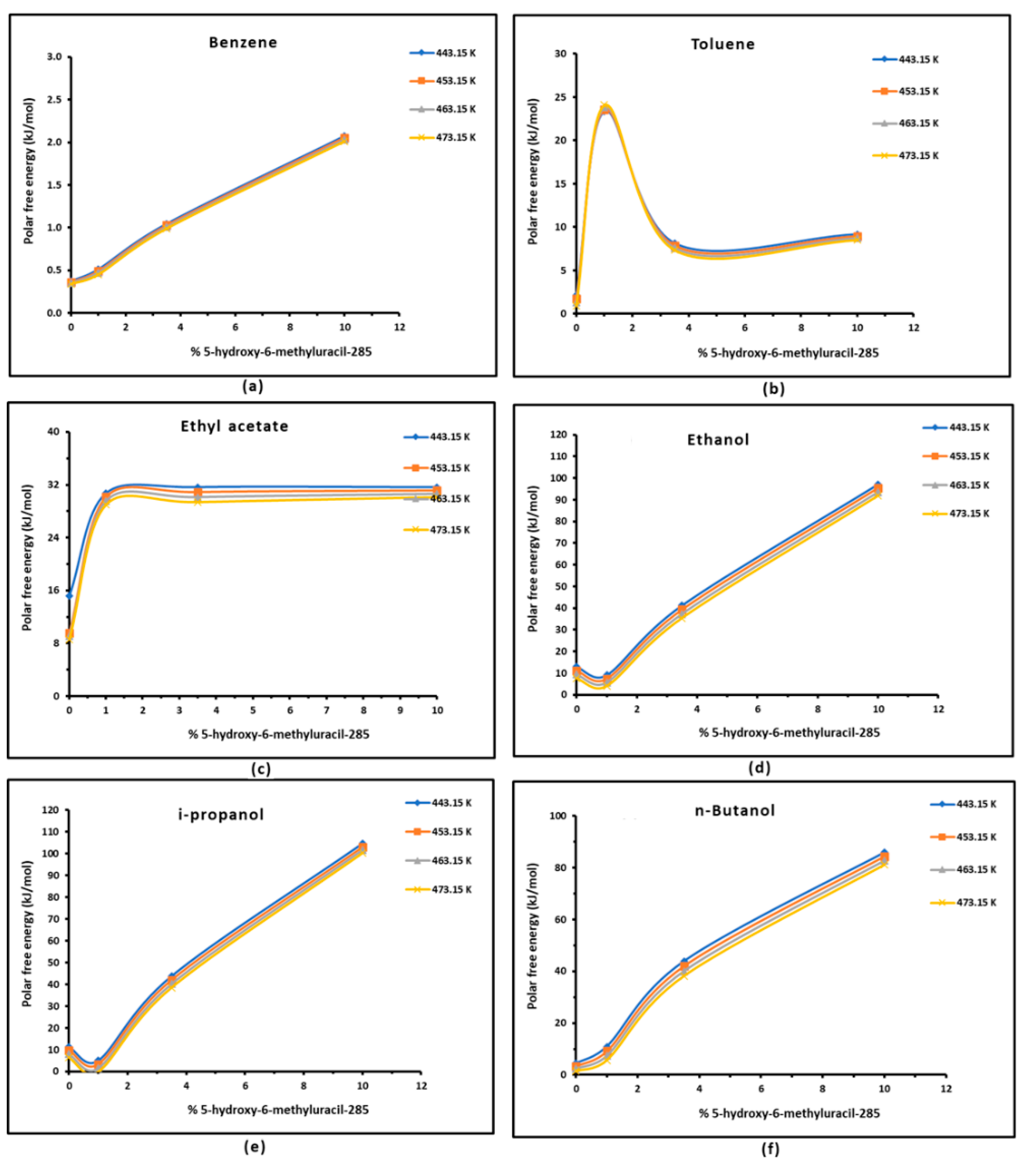

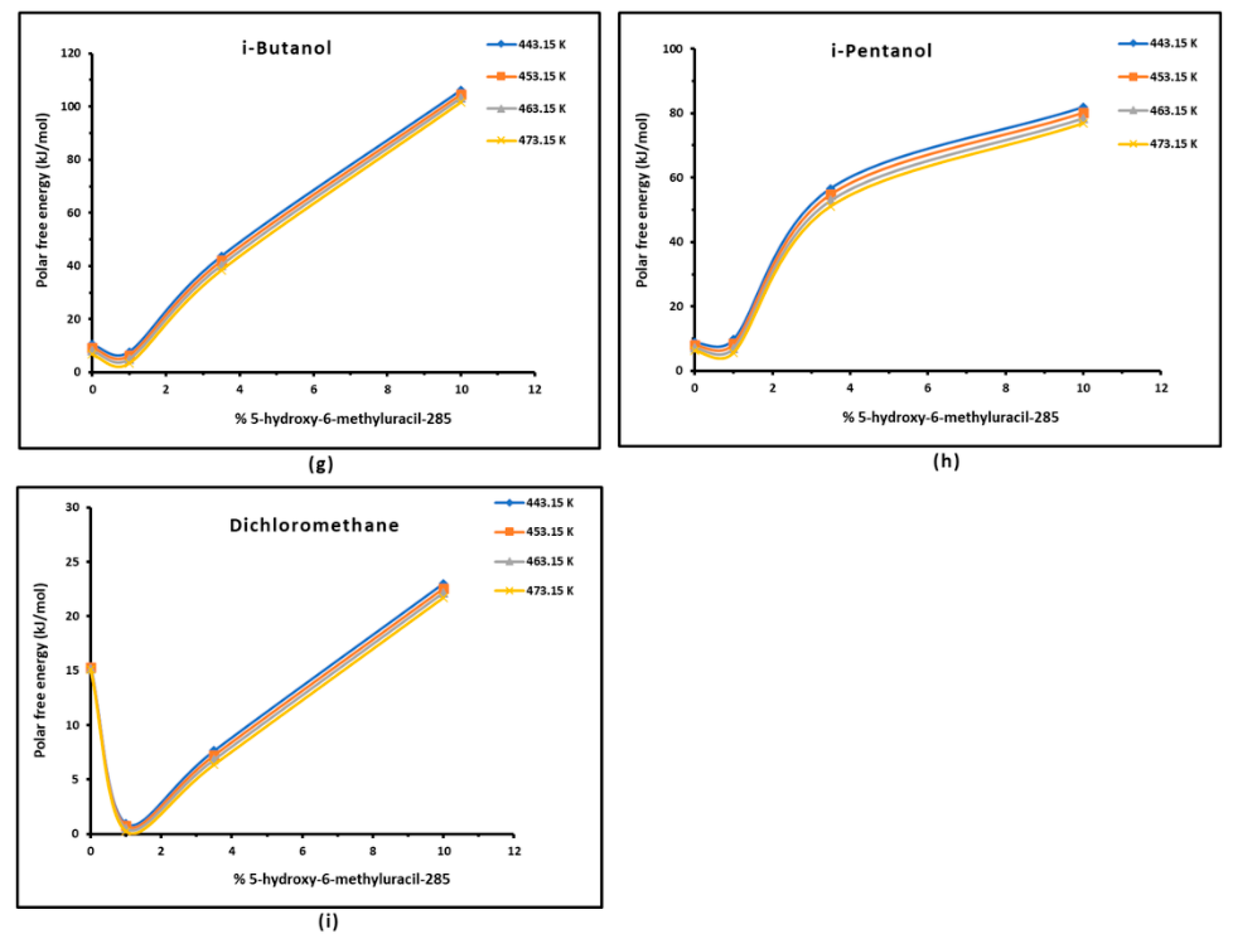

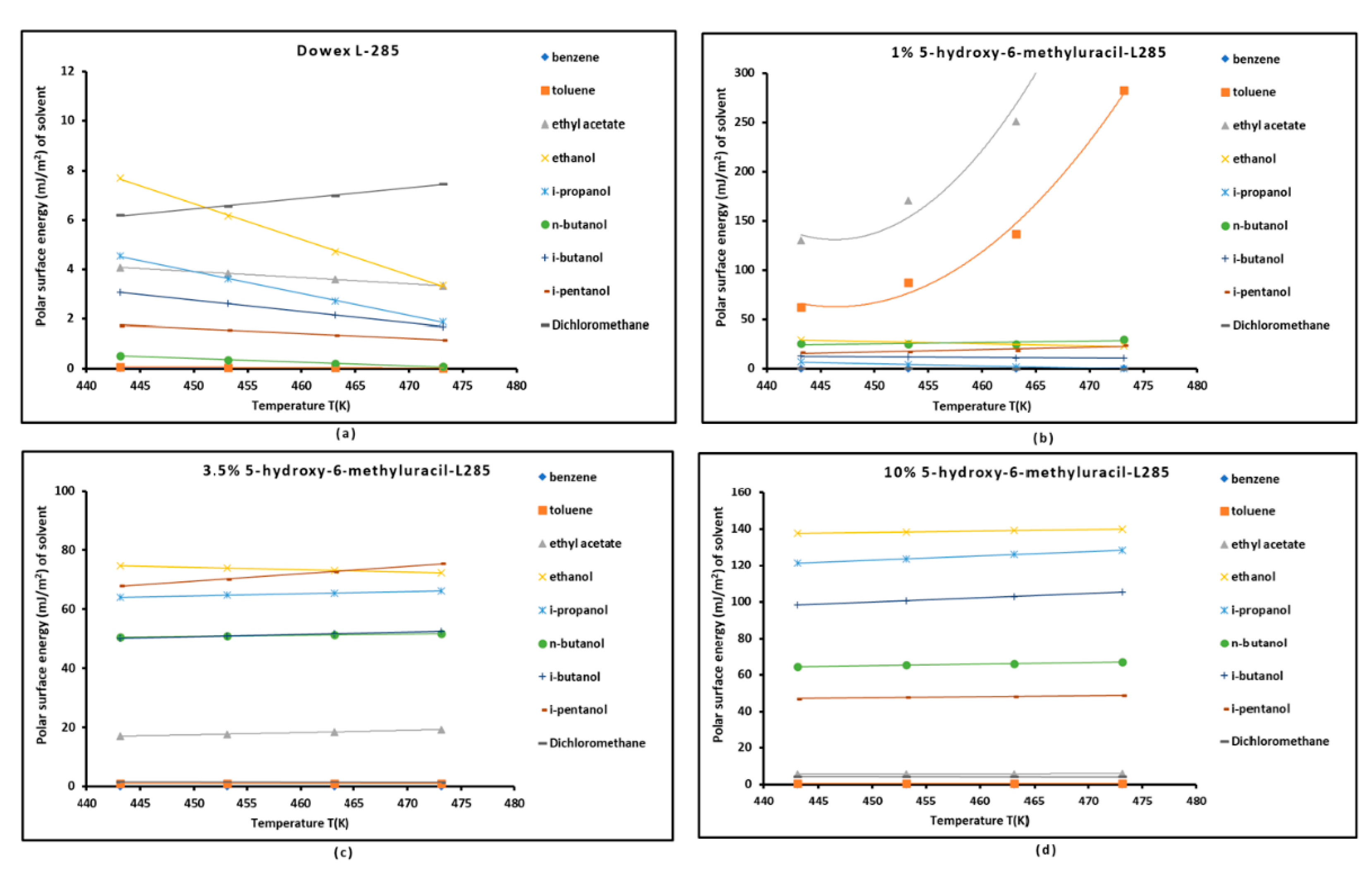

3.3. Polar Free Interaction Energy of Dowex L-285 Modified by 5-hydroxy-6-methyluracil with the Polar Probes

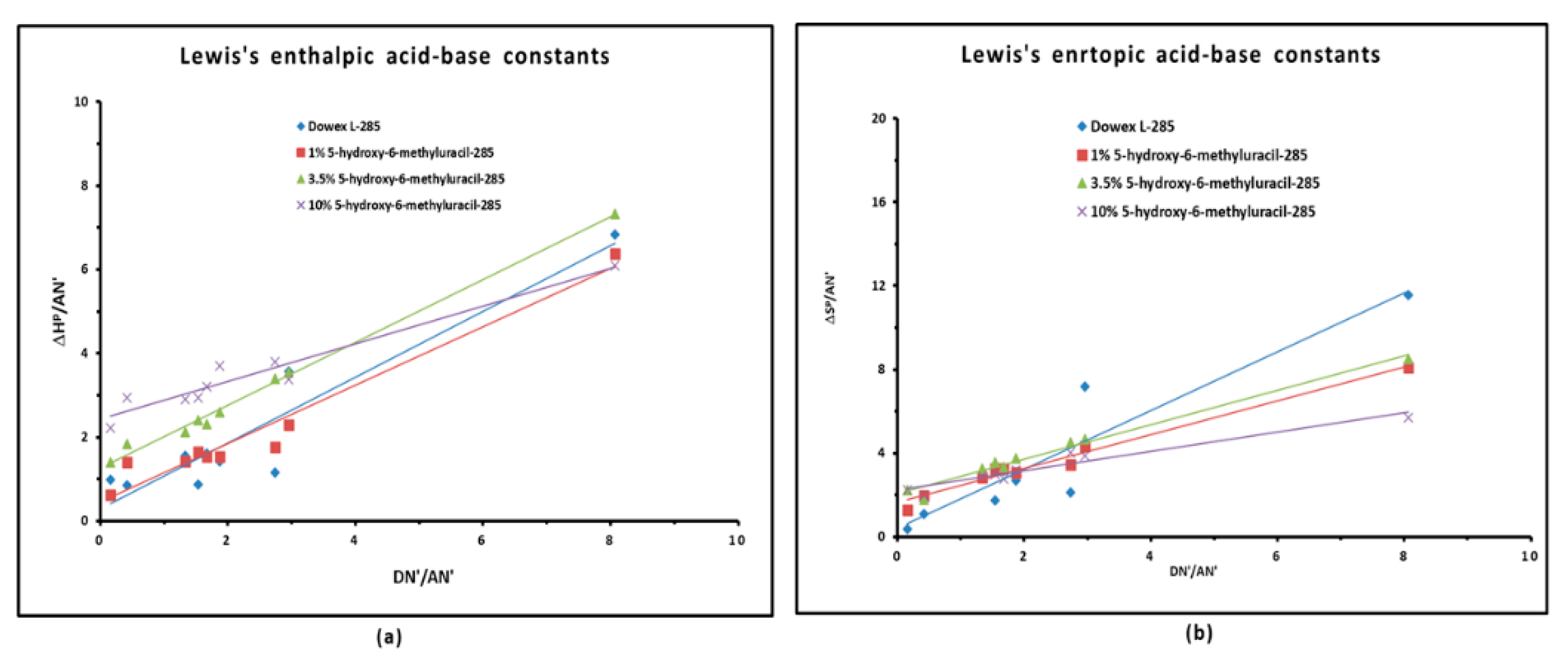

3.4. Polar Enthalpy and Entropy of Adsorption, and Lewis Acid–Base Parameters of Dowex L-285 Modified by 5-hydroxy-6-methyluracil

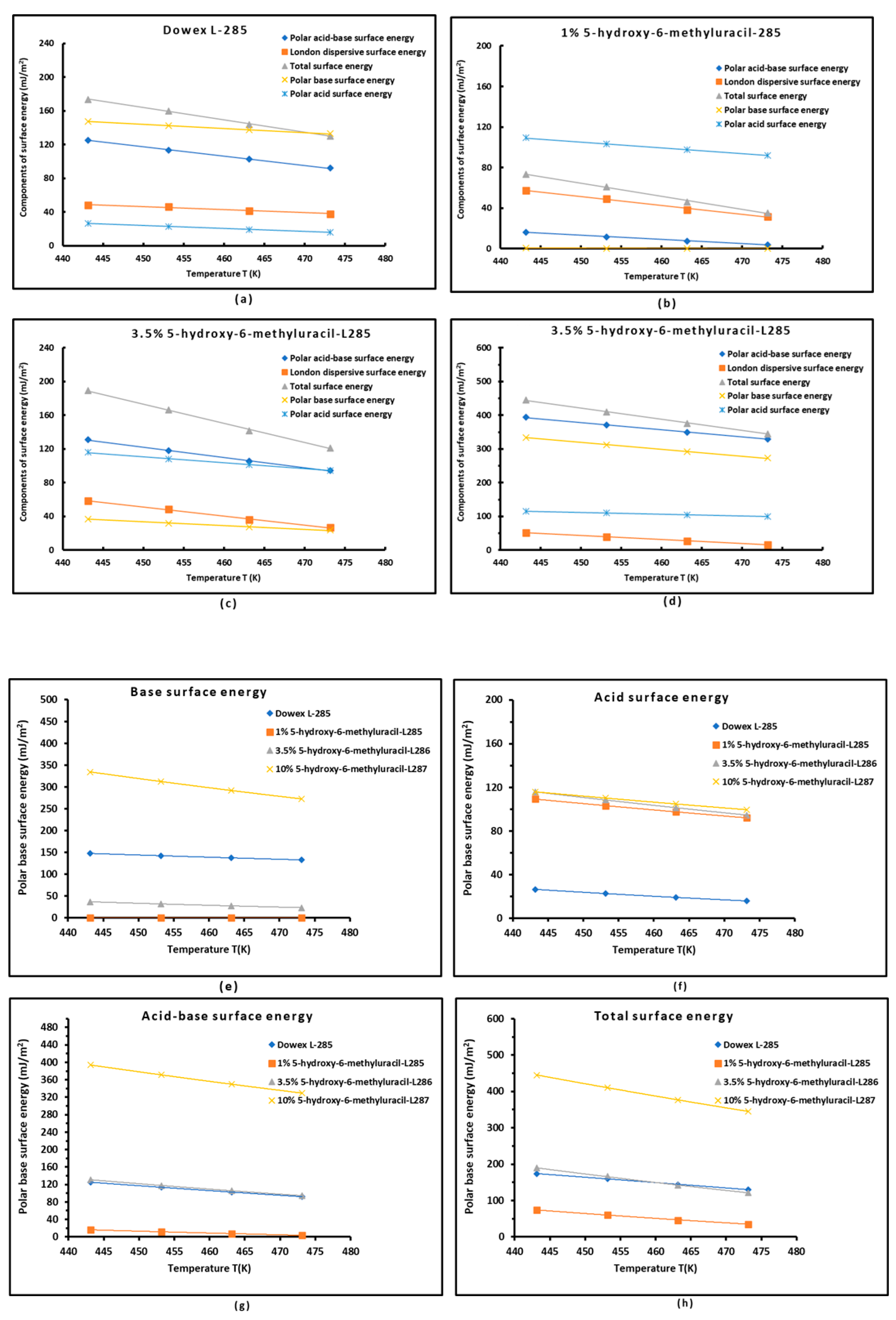

3.5. Polar Acid–Base Surface Energies of S-DVB Copolymer Modified by HMU

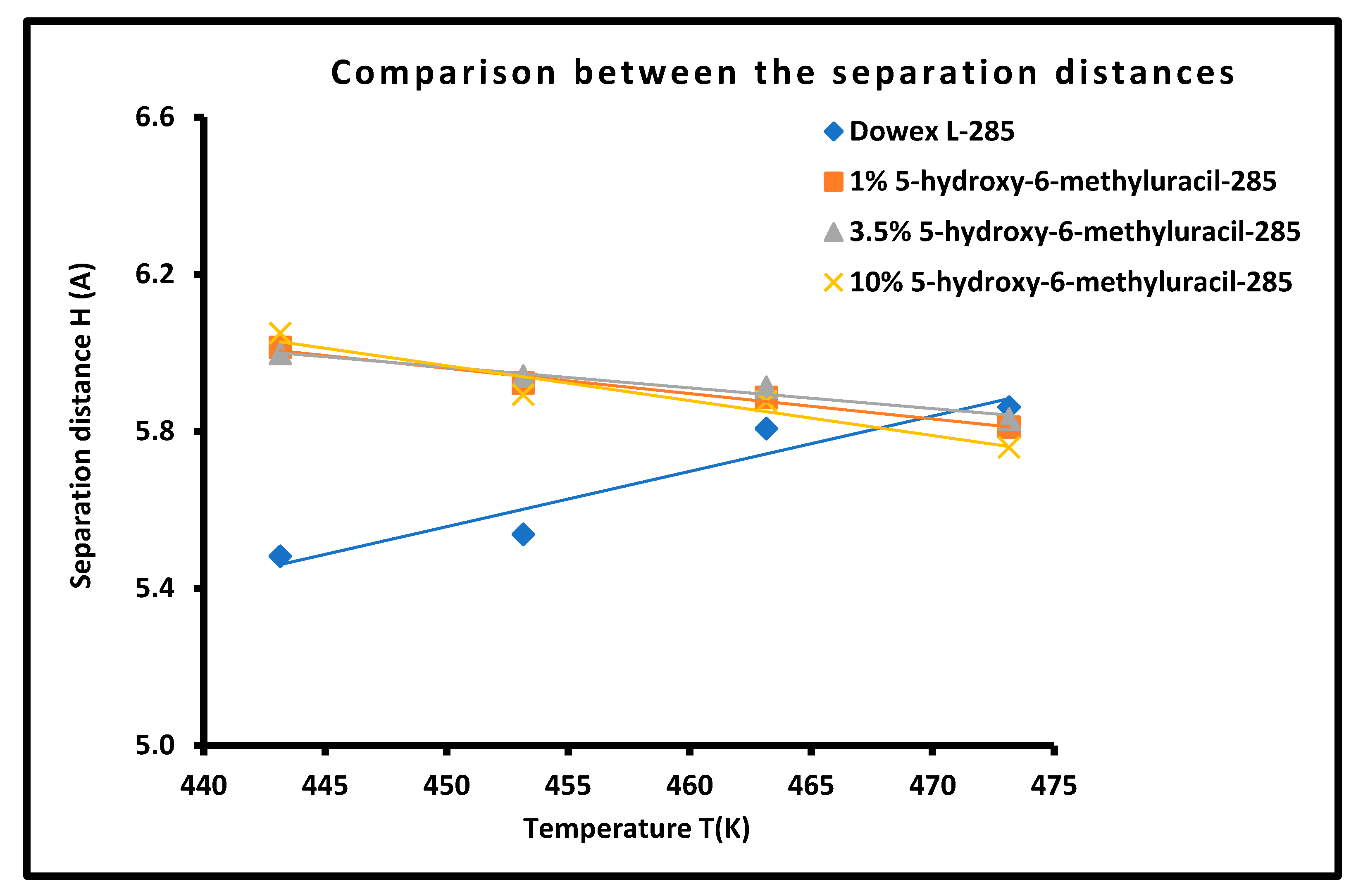

3.6. Determination of the Average Separation Distance H

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Helfferich, F. Ion Exchange. Dover Publications Inc., New York. USA, 624p., 1962.

- Kunin, R. Ion Exchange Resins. Wiley-Interscience. New York. USA 504p., 1972.

- Guo, X.; Zhang, S.; Shan, X. Adsorption of metal ions on lignin, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2008, 151 (1), 134-142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.05.065. [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, A. Adsorption—from theory to practice. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, 2001, 93(1–3), 135–224.

- Vashurin, A. S.; Barabanov, V. M. Coordination and Sorption Capabilities of 5-Hydroxy-6-Methyluracil-Based Compounds. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2015, 85(10), 2287–2292.

- Pałasz, A.; Cież, D. In search of uracil derivatives as bioactive agents. Uracils and fused uracils: Synthesis, biological activity and applications, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2015, 97, 582-611, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.10.008. [CrossRef]

- Samuilov, P. Modified uracils in medicinal chemistry. Russian Chemical Reviews, 2016, 85(4), 374–390.

- Epure, E.L.; Moleavin, I.A.; Taran, E. Nguyen, A.V.; Nichita, N.; Hurduc, N. Azo-polymers modified with nucleobases and their interactions with DNA molecules. Polym. Bull. 2011, 67, 467–478, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-010-0436-1. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Kim, K.H.; Yoon, H.; Kim, H. Chemical Design of Functional Polymer Structures for Biosensors: From Nanoscale to Macroscale. Polymers 2018, 10, 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10050551. [CrossRef]

- Lehn, J.-M. Supramolecular Chemistry. Concepts and Perspectives; VCH: Weinhiem, Germany, 1995; pp. 271. https://doi.org/10.1002/3527607439.index. [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.P.; Kashyap, S.; Singh, H.J.; Mishra, B.K.; Roy, P.; Chakraborty, A. Effect of adenosine on the supramolecular architecture and activity of 5-fluorouracil. J. Mol. Struct. 2012, 1014, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.01.035. [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Yu.; Vereschetin, V.P.; Gromov, S.P.; Fedorova, O.A.; Alfimov, M.V.; Huesmann, H.; Möbius, D. Photosensitive supramolecular systems based on amphiphilic crown ethers, Supramol. Sci. 1997, 4, 519–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-5677(97)00037-0. [CrossRef]

- Gus’kov, V.Y.; Bilalova, R.V.; Kudasheva, F.K. Adsorption of organic molecules on a 5-hydroxy-6-methyluracil -modified porous polymer. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2017, 66, 857–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11172-017-1818-4. [CrossRef]

- Sukhareva, D.A.; Gus´kov, V.Y.; Karpov, S.I.; Kudasheva, F.K. Adsorption of organic molecules on the highly ordered MCM-41 sorbent modified by different amounts of 5-hydroxy-6-methyluracil. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2017, 66, 958–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11172-017-1838-0. [CrossRef]

- Gainullina, Y.Y.; Gus’kov, V.Y.; Timofeeva, D.V. Polarity of Thymine and 6-Methyluracil-Modified Porous Polymers, According to Data from Inverse Gas Chromatography. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 2019, 93, 2477–2481. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036024419120082. [CrossRef]

- Gus’kov, V.Y.; Gainullina, Y.Y.; Ivanov, S.P.; Kudasheva; F.K. Thermodynamics of organic molecule adsorption on sorbents modified with 5-hydroxy-6-methyluracil by inverse gas chromatography. Journal of chromatography. A, 2014, 1356, 230-235.

- Gus’kov, V.Y.; Gainullina, Y.Y.; Ivanov, S.P.; Kudasheva, F.K. Porous polymer adsorbents modified with uracil. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2014, 50, 55–58.

- Gus’kov, V.Y.; Ivanov, S.P.; Khabibullina, R.A.; Garafutdinov, R.R.; Kudasheva, F.K. Gas chromatographic investigation of the properties of a styrene-divinylbenzene copolymer modified by 5-hydroxy-6-methyluracil. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 86, 475–478.

- Schultz, J.; Lavielle, L.; Martin, C. The Role of the Interface in Adhesion. J. Adhes. 1987, 23, 45–60.

- Mittal, K. L. Contact Angle, Wettability and Adhesion; VSP: Leiden, 2003.

- van Oss, C. J. Interfacial Forces in Aqueous Media, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2006.

- Hamieh, T. Study of the temperature effect on the surface area of model organic molecules, the dispersive surface energy and the surface properties of solids by inverse gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1627, 461372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461372. [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T.; Ahmad, A.A.; Roques-Carmes, T.; Toufaily, J. New approach to determine the surface and interface thermodynamic properties of H-β-zeolite/rhodium catalysts by inverse gas chromatography at infinite dilution. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20894. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78071-1. [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. New methodology to study the dispersive component of the surface energy and acid–base properties of silica particles by inverse gas chromatography at infinite dilution. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2022, 60, 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1093/chromsci/bmab066. [CrossRef]

- Davankov, V. A.; Tsyurupa, M. P. Highly Crosslinked Macroporous Polymers: Synthesis, Properties, Applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2006, 66, 846–856.

- Hamieh, T.; Schultz, J. New approach to characterise physicochemical properties of solid substrates by inverse gas chromatography at infinite dilution. Some new methods to determine the surface areas of some molecules adsorbed on solid surfaces. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 969, 17–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00368-0. [CrossRef]

- Samuilov, P. D. Modified Uracils in Medicinal Chemistry and Biopolymer Functionalization. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2016, 85(4), 374–390.

- Hamieh, T. Inverse Gas Chromatography to Characterize the Surface Properties of Solid Materials. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 2231–2244. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.3c03091. [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. Some Irregularities in the Evaluation of Surface Parameters of Solid Materials by Inverse Gas Chromatography. Langmuir 2023, 39, 17059–17070. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c01649. [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. New Progress on London Dispersive Energy, Polar Surface Interactions, and Lewis’s Acid–Base Properties of Solid Surfaces. Molecules 2024, 29, 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29050949. [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. London Dispersive and Lewis Acid-Base Surface Energy of 2D Single-Crystalline and Polycrystalline Covalent Organic Frameworks. Crystals 2024, 14, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst14020148. [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T.; Gus'kov, V.Y. Surface Thermodynamic Properties of Styrene–Divinylbenzene Copolymer Modified by Supramolecular Structure of Melamine Using Inverse Gas Chromatography. Chemistry 2024, 6, 830-851. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry6050050. [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, V. The Donor-acceptor Approach to Molecular Interactions. Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 279.

- Riddle, F.L.; Fowkes, F.M. Spectral shifts in acid-base chemistry. Van der Waals contributions to acceptor numbers, Spectral shifts in acid-base chemistry. 1. van der Waals contributions to acceptor numbers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 3259–3264. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00165a001. [CrossRef]

- Fowkes, F.M. Volume 1 Surface Chemistry and Physics. In Surface and interfacial aspects of biomedical polymers; Andrade, J.D., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, USA, 1985; pp. 337–372.

- Van Oss, C.J.; Good, R.J.; Chaudhury, M.K. Additive and nonadditive surface tension components and the interpretation of contact angles. Langmuir. 1988, 4, 884. https://doi.org/10.1021/la00082a018. [CrossRef]

- Dorris, G.M.; Gray, D.G. Adsorption of n-alkanes at zero surface coverage on cellulose paper and wood fibers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1980, 77, 353–362.

| Copolymer | (mJ/m2) | R2 | (mJ m−2 K−1) | (mJ/m2) | (mJ/m2) | (K) |

| S-DVB-L-285 | = -0.835 T + 482.43 | 0.9980 | -0.835 | 482.43 | 233.47 | 577.8 |

| 1% HOMU/ S-DVB-L-285 | = -0.874 T + 444.68 | 0.9837 | -0.874 | 444.68 | 184.16 | 508.9 |

| 3.5% HOMU/ S-DVB-L-285 | = -1.096 T + 544.23 | 0.9886 | -1.096 | 544.23 | 217.52 | 496.7 |

| 10% HOMU/ S-DVB-L-285 | = -1.198 T + 582.13 | 0.9973 | -1.198 | 582.13 | 224.95 | 485.9 |

| Copolymer | (mJ/m2) | R2 | (mJ m−2 K−1) | (mJ/m2) | (mJ/m2) | (K) |

| S-DVB-L-285 | = 3.250 T + 1610.5 | 0.9037 | -3.25 | 1610.5 | 641.51 | 495.54 |

| 1% HOMU/ S-DVB-L-285 | = 1.065 T - 416.4 | 0.9855 | 1.065 | -416.4 | -98.87 | 390.99 |

| 3.5% HOMU/ S-DVB-L-285 | = 1.091 T - 421.2 | 0.9493 | 1.091 | -421.2 | -95.92 | 386.07 |

| 10% HOMU/ S-DVB-L-285 | = 1.474 T - 600.3 | 0.9413 | 1.474 | -600.3 | -160.83 | 407.26 |

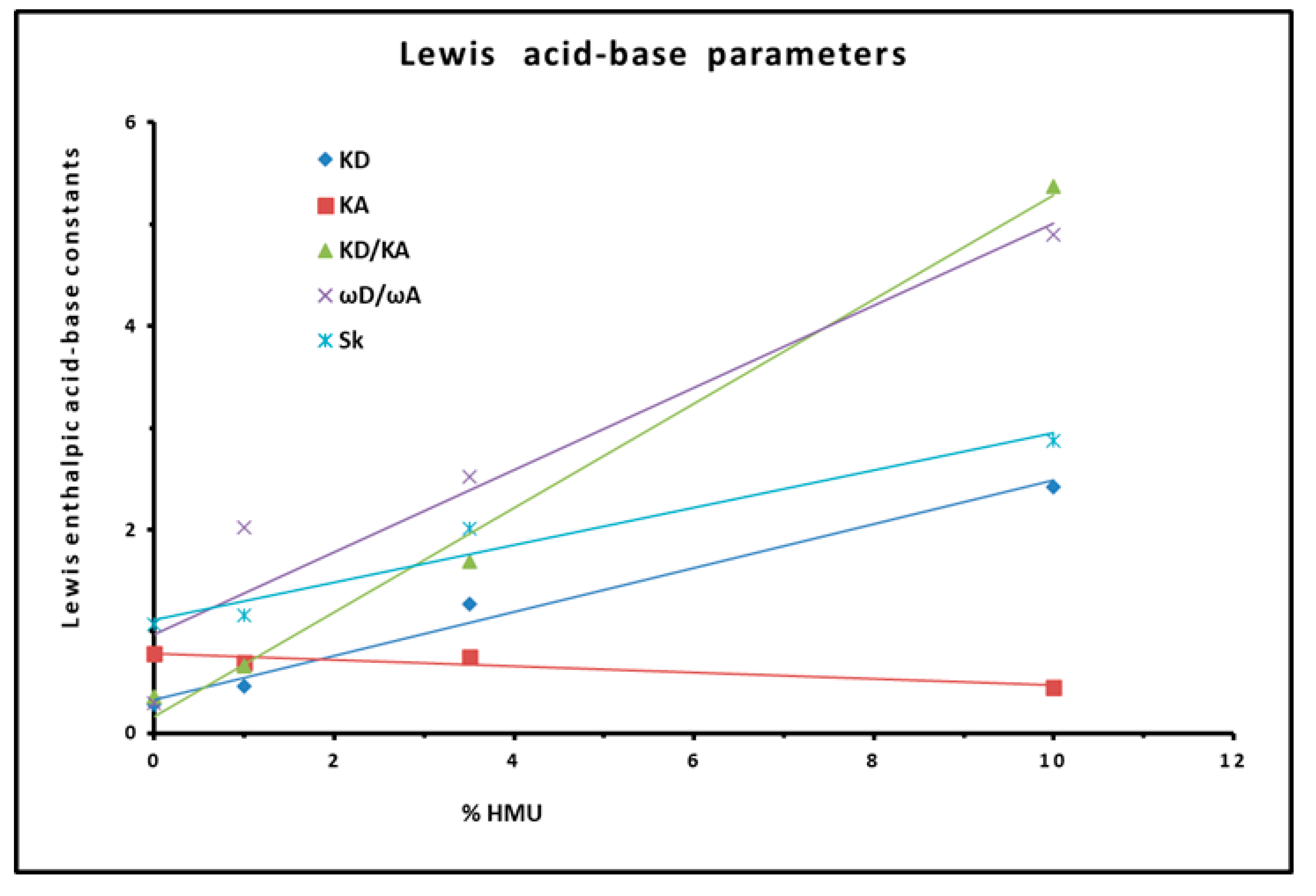

| Material | R2 | 10−3 | 10−3 | / | 10−3 () | R2 | ||||

| S-DVB-L-285 | 0.283 | 0.786 | 0.36 | 1.069 | 0.886 | 0.43 | 1.41 | 0.30 | 1.83 | 0.871 |

| 1% HMU on S-DVB-L-285 | 0.459 | 0.696 | 0.66 | 1.155 | 0.9561 | 1.64 | 0.81 | 2.02 | 2.45 | 0.975 |

| 3.5% HMU on S-DVB-L-285 | 1.265 | 0.75 | 1.69 | 2.015 | 0.994 | 2.07 | 0.82 | 2.52 | 2.89 | 0.9806 |

| 10% HMU on S-DVB-L-285 | 2.425 | 0.451 | 5.38 | 2.876 | 0.9397 | 2.25 | 0.46 | 4.89 | 2.71 | 0.9277 |

| Parameter | Equation | R² |

| Acid constant | = 0.22 %HMU + 0.33 | 0.9839 |

| Basic constant | = -0.031 %HMU + 0.79 | 0.8638 |

| Ratio | = 0.51 %HMU + 0.17 | 0.9926 |

| Ratio / | / = 0.40 %HMU + 0.97 | 0.9165 |

| Parameter | = 0.18 %HMU + 1.11 | 0.9561 |

| Dichloromethane | ||||

| T(K) | Dowex L-285 | 3.5% HOMU/Dowex L-285 | 1% HOMU/Dowex L-285 | 10% HOMU/Dowex L-285 |

| 453.15 | 15.274 | 15.609 | 24.349 | 9.737 |

| 458.15 | 15.239 | 15.559 | 24.294 | 9.352 |

| 463.15 | 15.204 | 15.509 | 24.239 | 8.967 |

| 468.15 | 15.169 | 15.459 | 24.184 | 8.582 |

| Ethyl Acetate | ||||

| T(K) | Dowex L-285 | 3.5% HOMU/Dowex L-285 | 1% HOMU/Dowex L-285 | 10% HOMU/Dowex L-285 |

| 453.15 | 10.106 | 8.503 | 9.667 | 10.567 |

| 458.15 | 9.593 | 8.378 | 9.507 | 10.314 |

| 463.15 | 9.079 | 8.253 | 9.347 | 10.06 |

| 468.15 | 8.566 | 8.128 | 9.187 | 9.807 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).