Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Technique

2.2. Thermodynamic Methods

2.2.1. Polar Free Energy of Adsorption and Lewis Acid-Base Equations

2.2.2. Surface Energetics of the modified copolymers

3. Results

3.1. Variations of the Free Energy of Adsorption

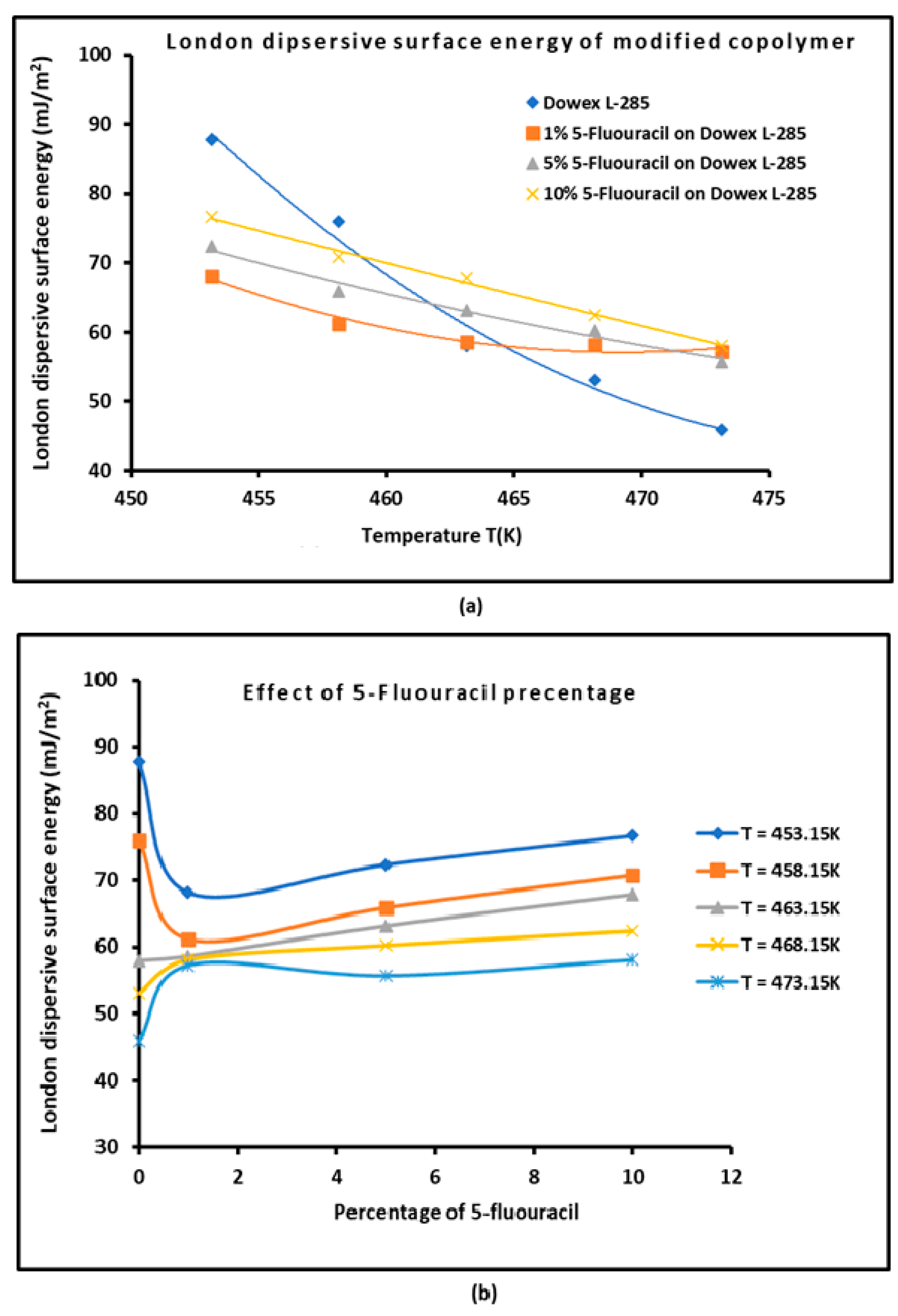

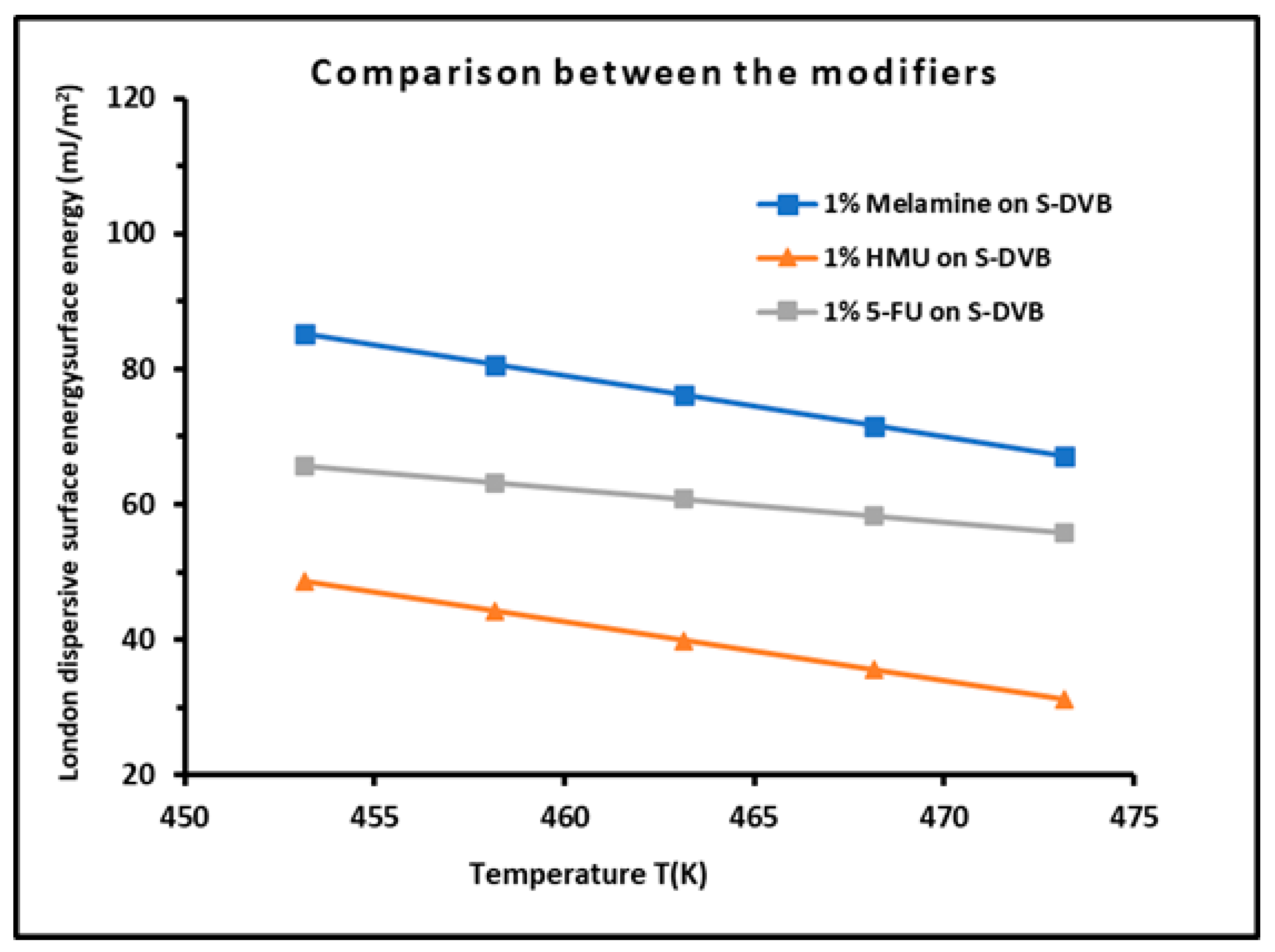

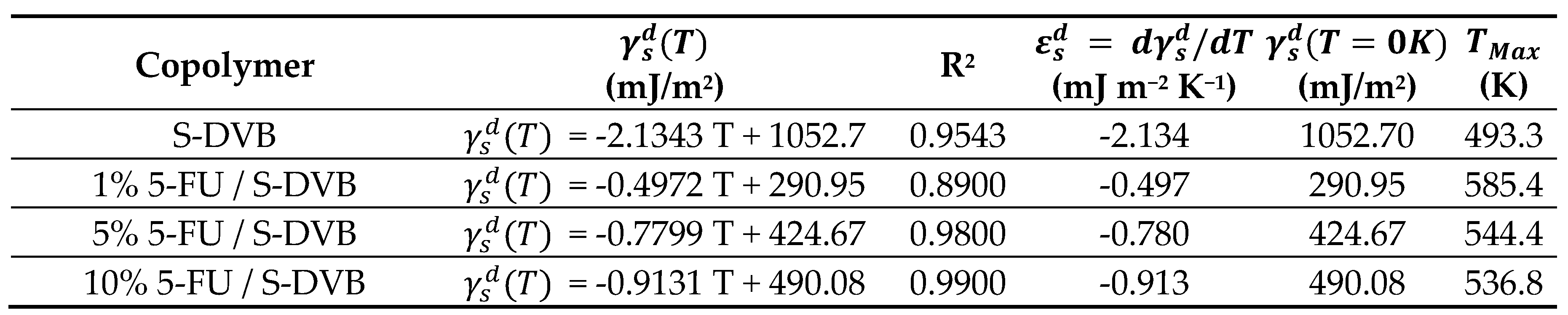

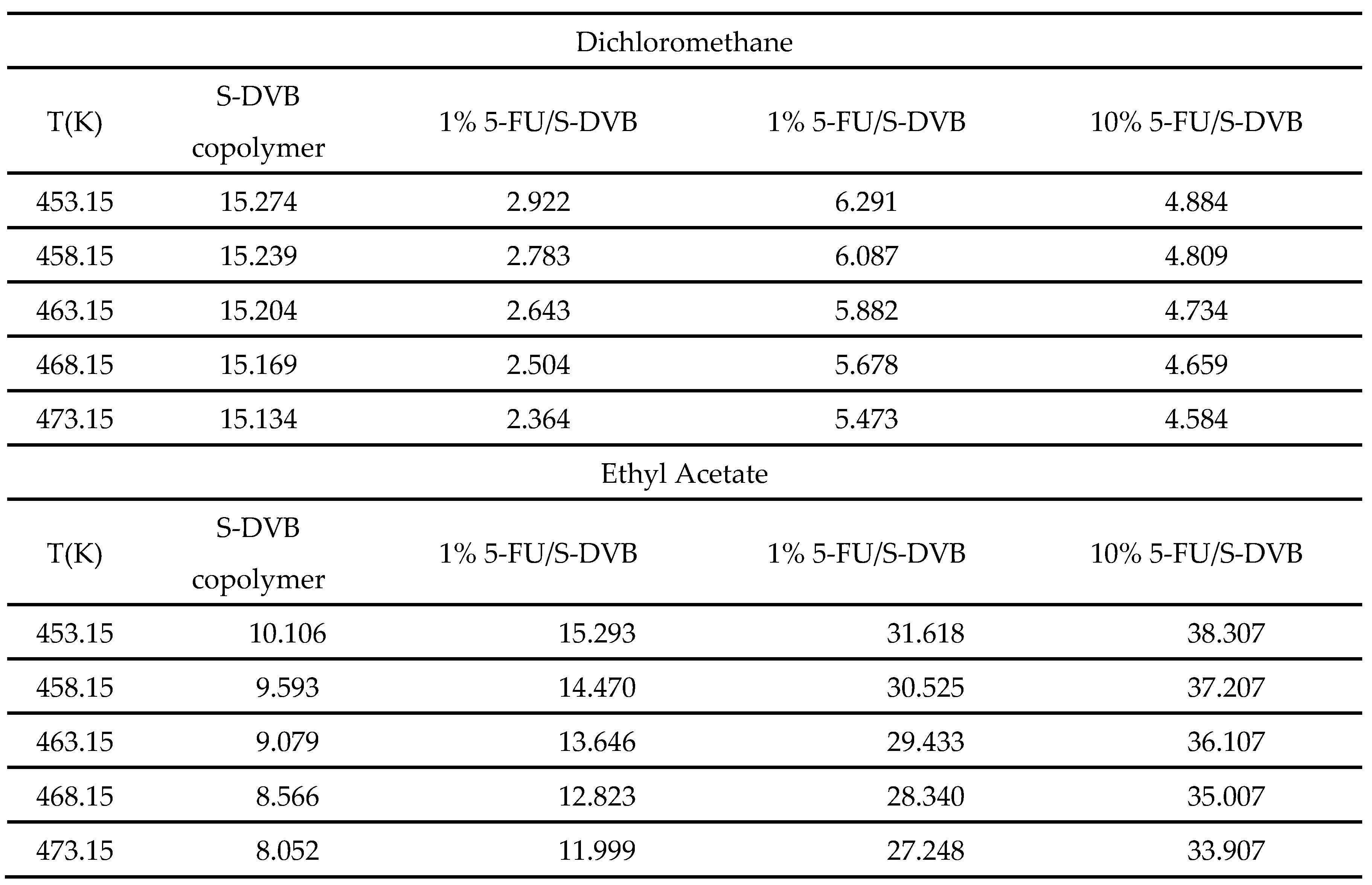

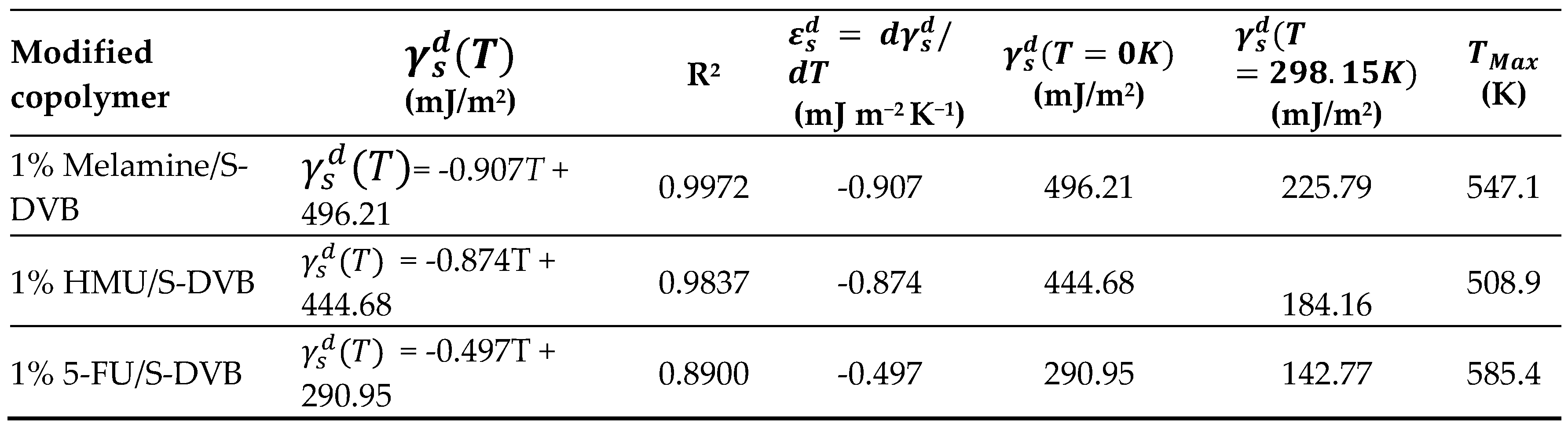

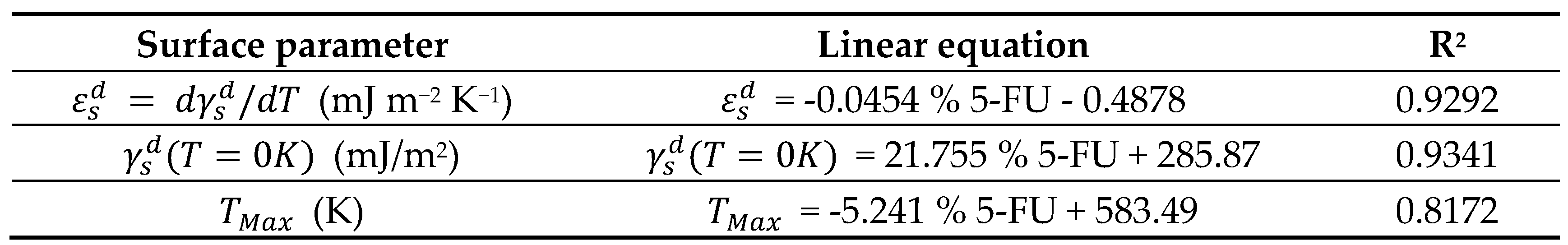

3.2. Determination of the London Dispersive Surface Energy

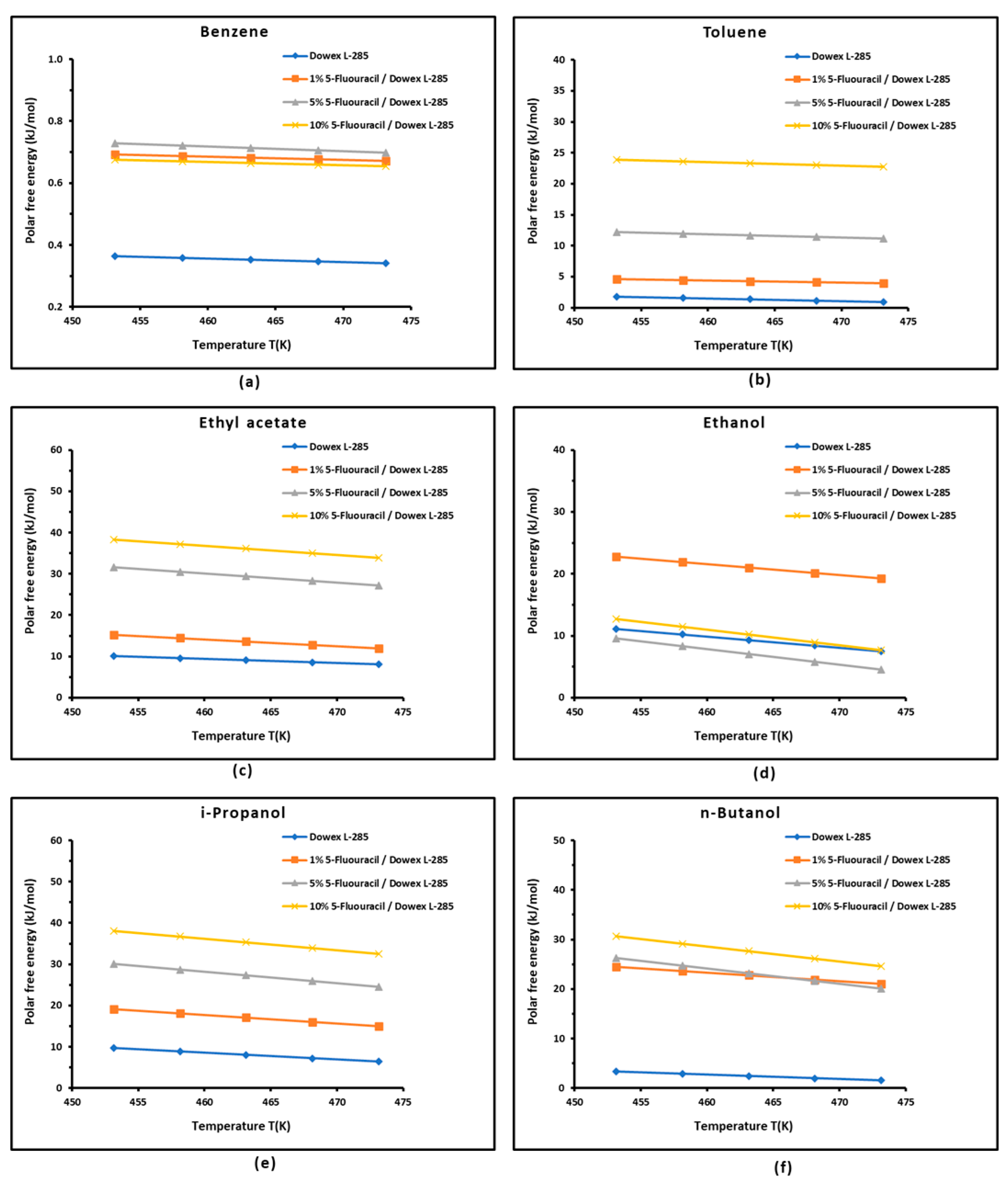

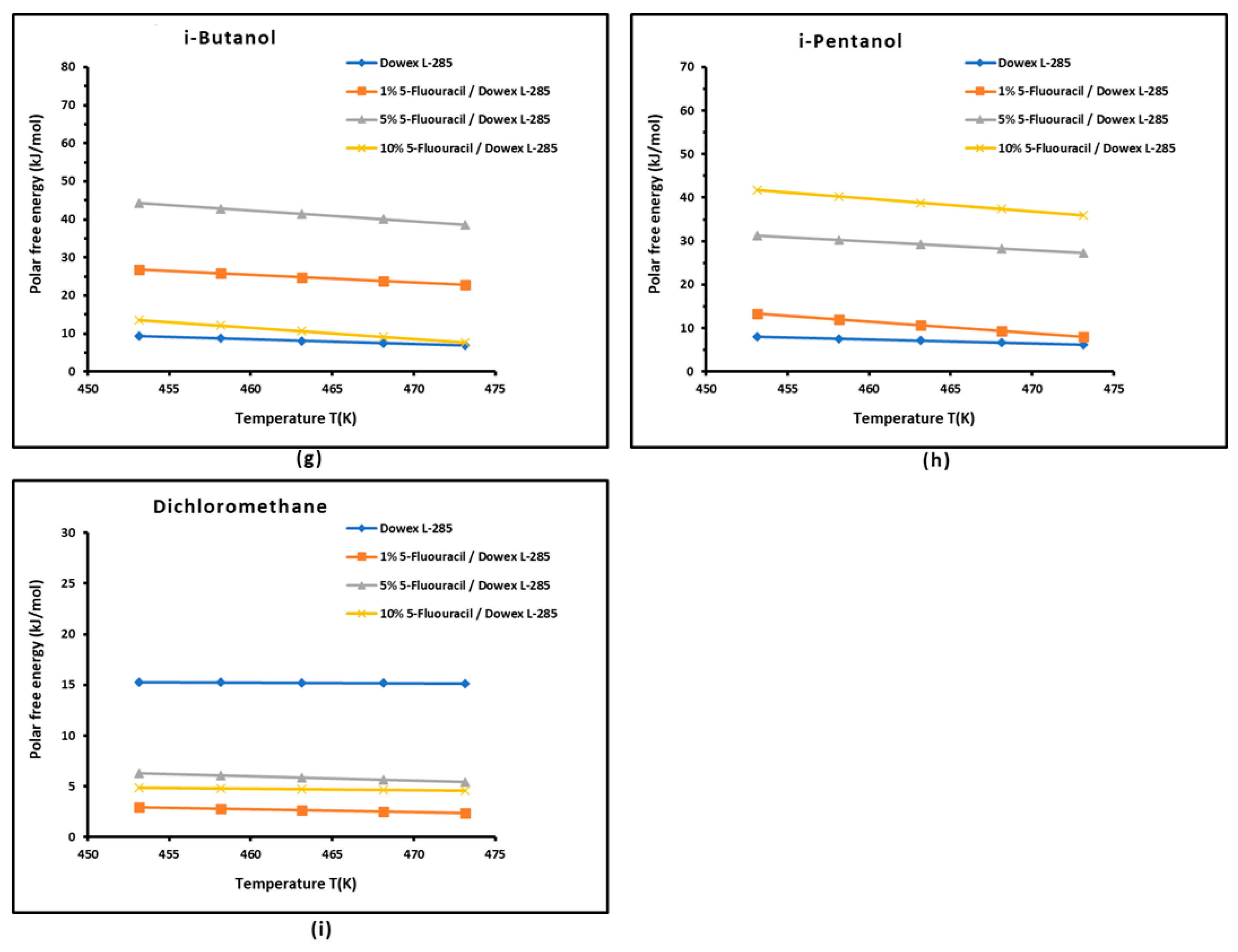

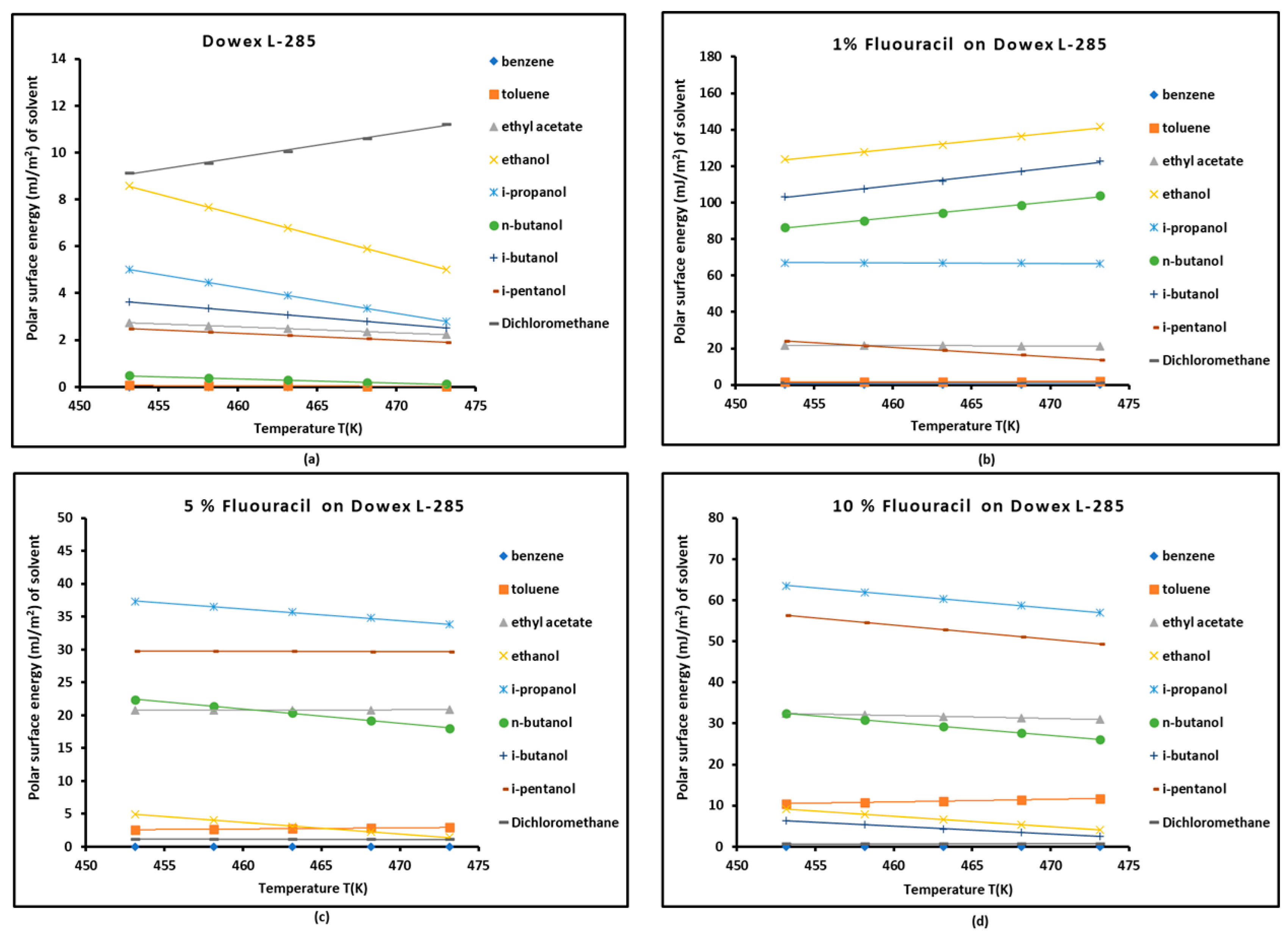

3.3. Polar Free Energy of Adsorption

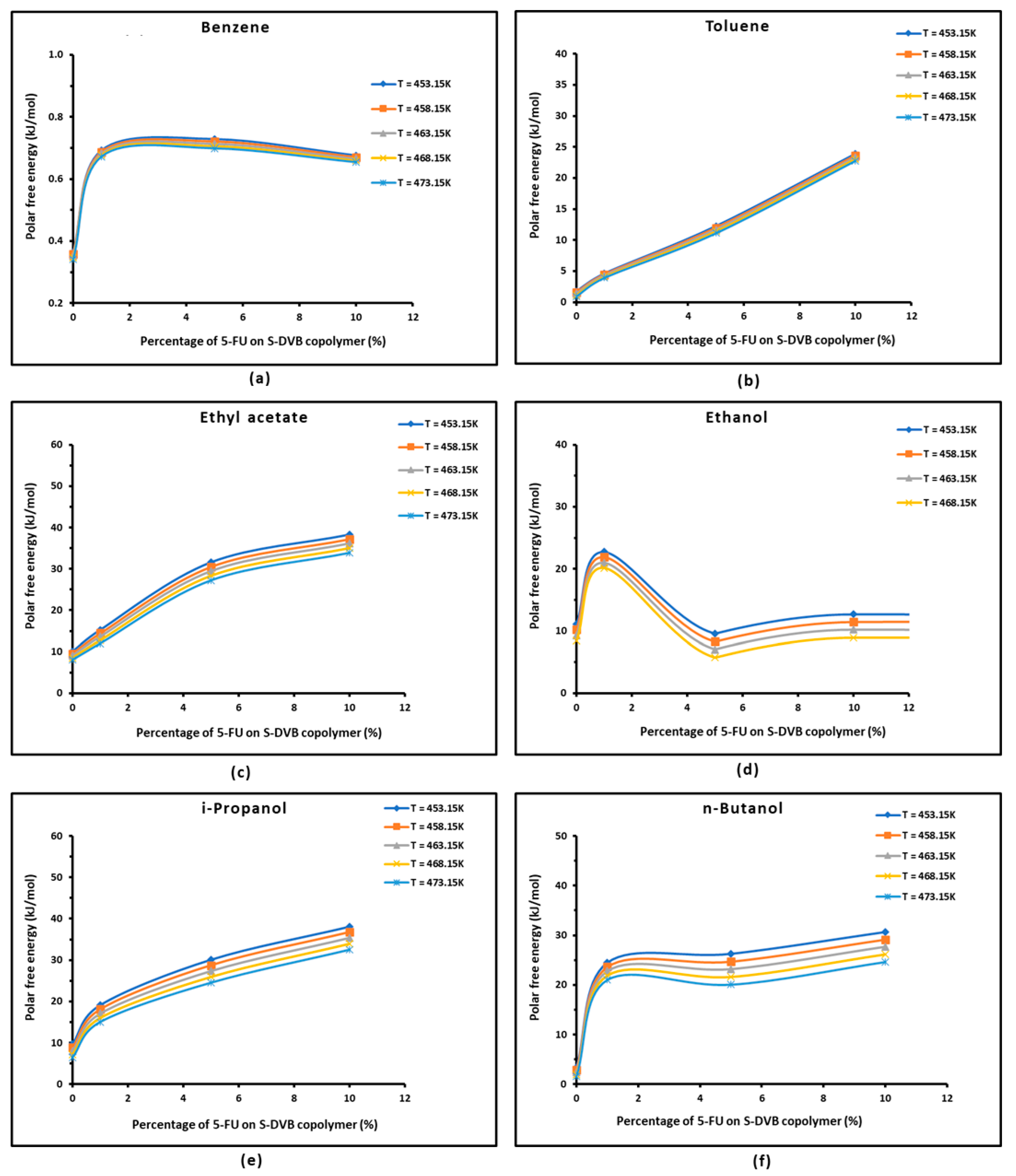

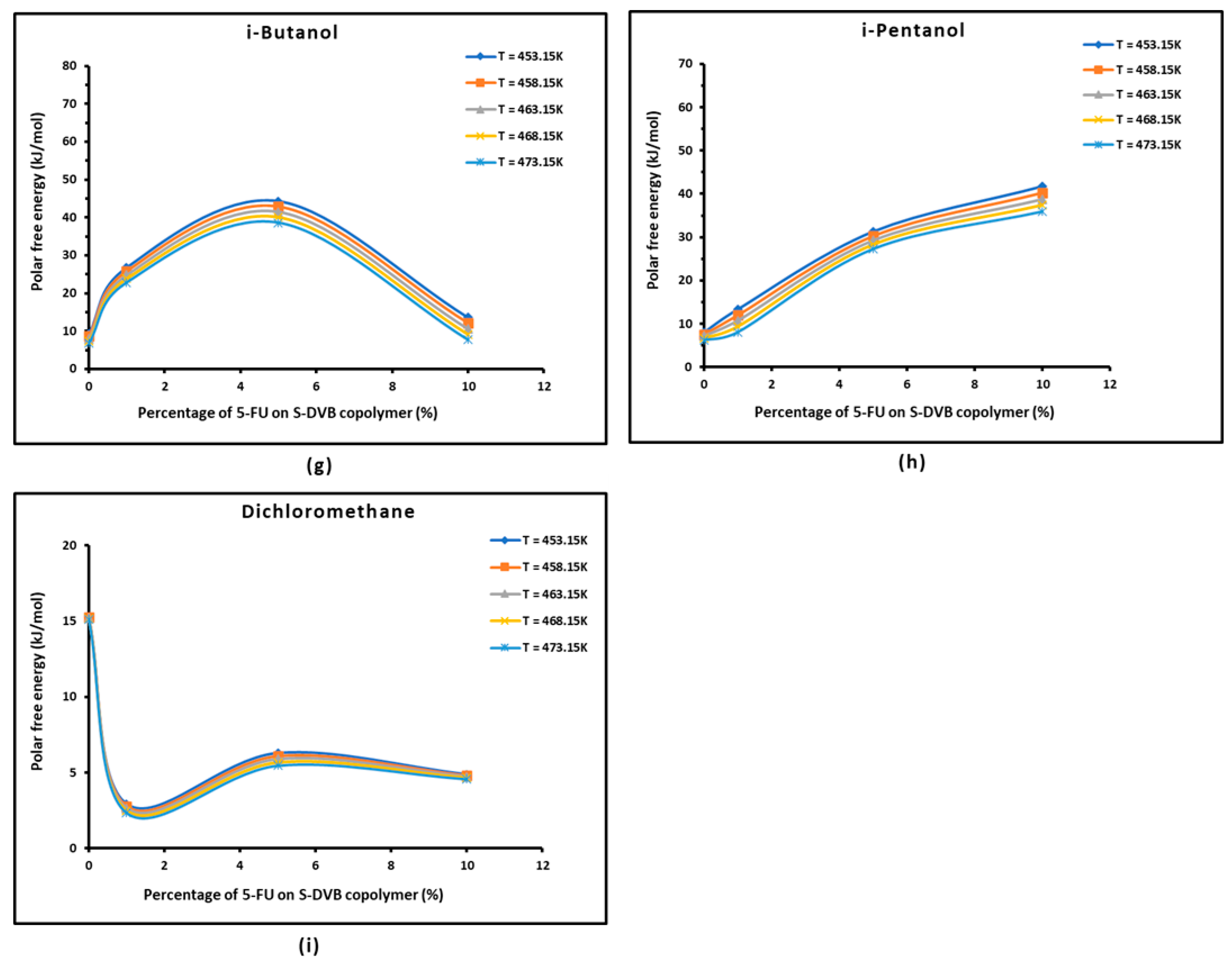

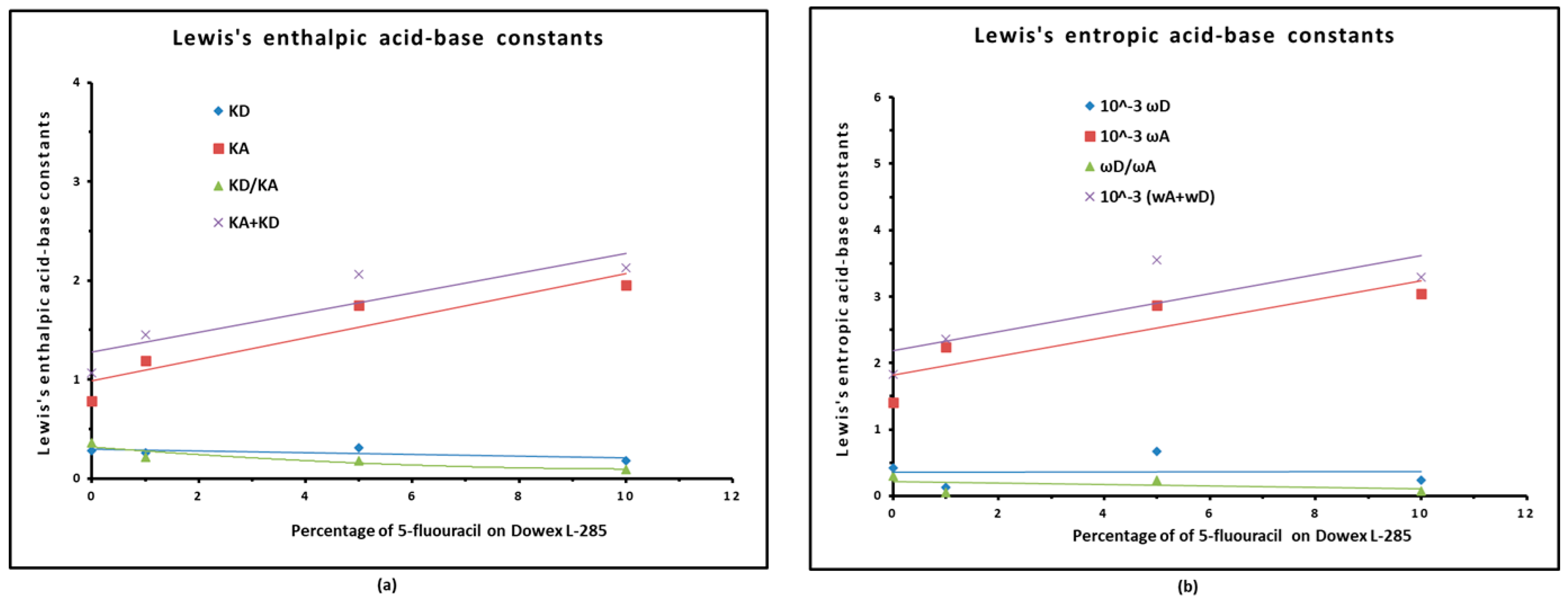

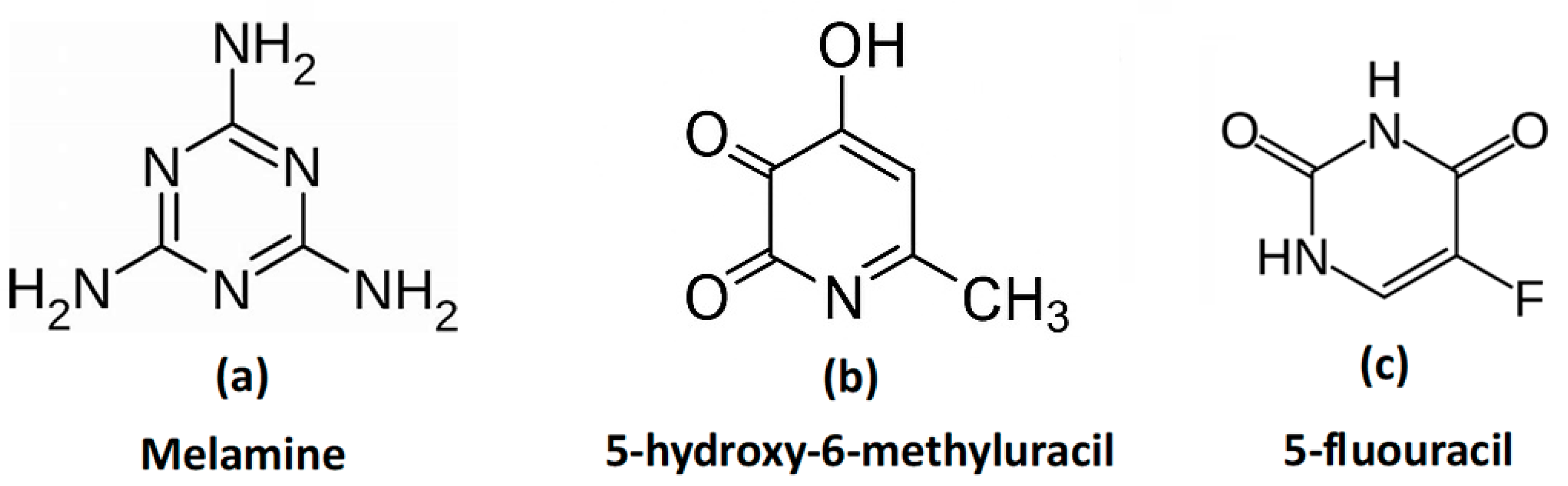

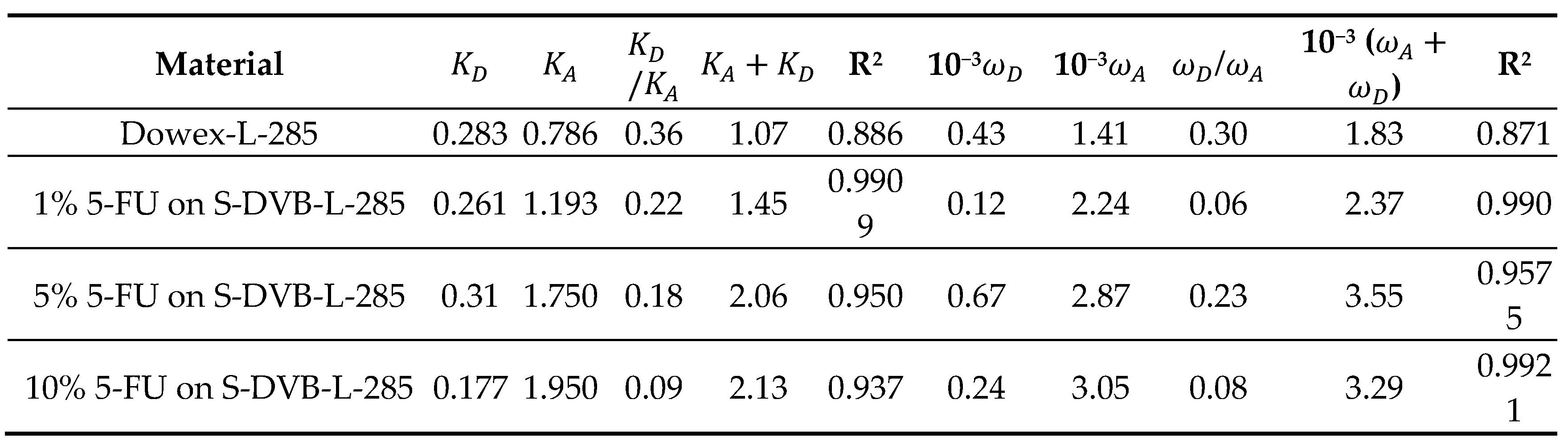

3.4. Lewis Acid–Base Properties

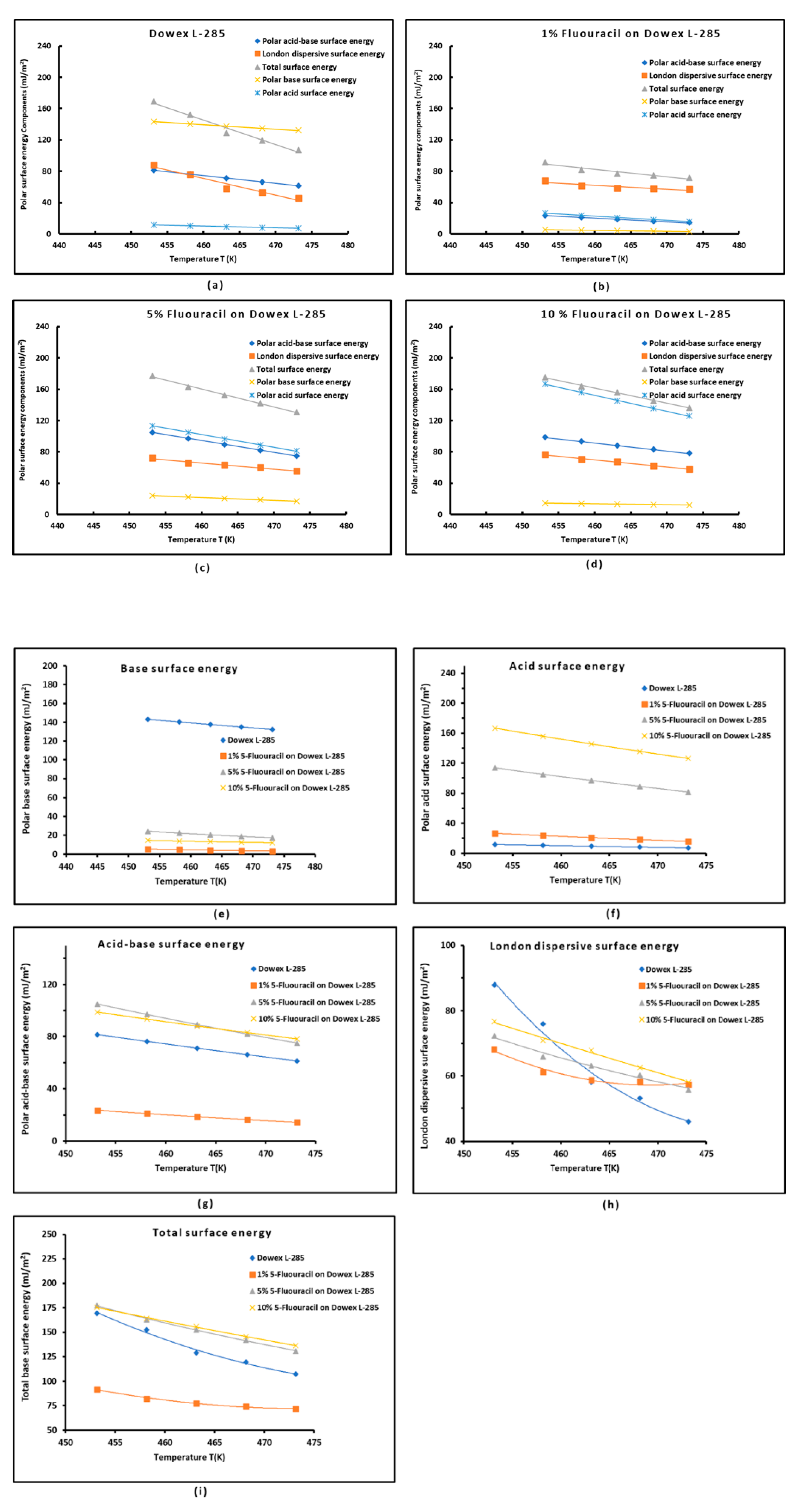

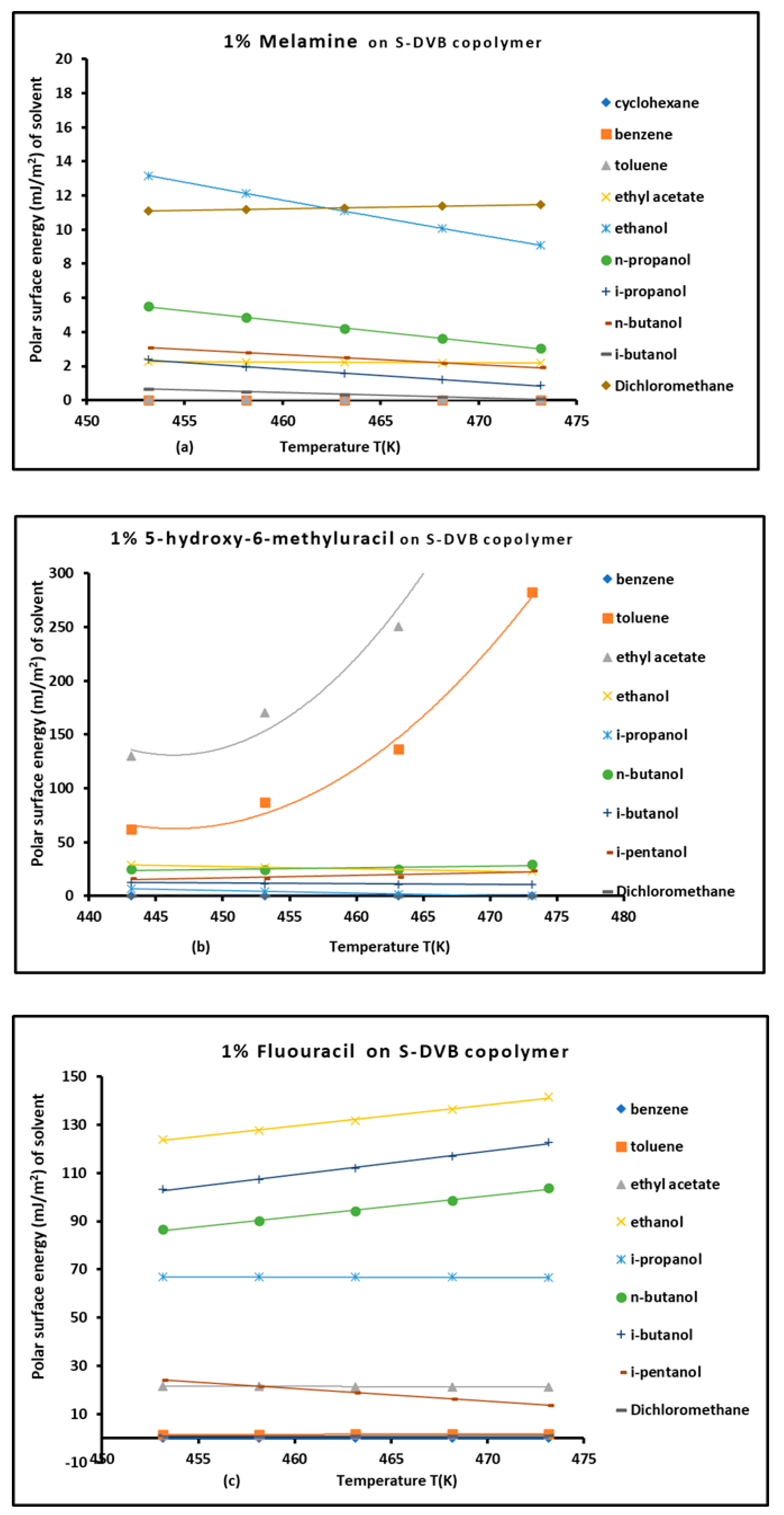

3.5. Polar surface energies

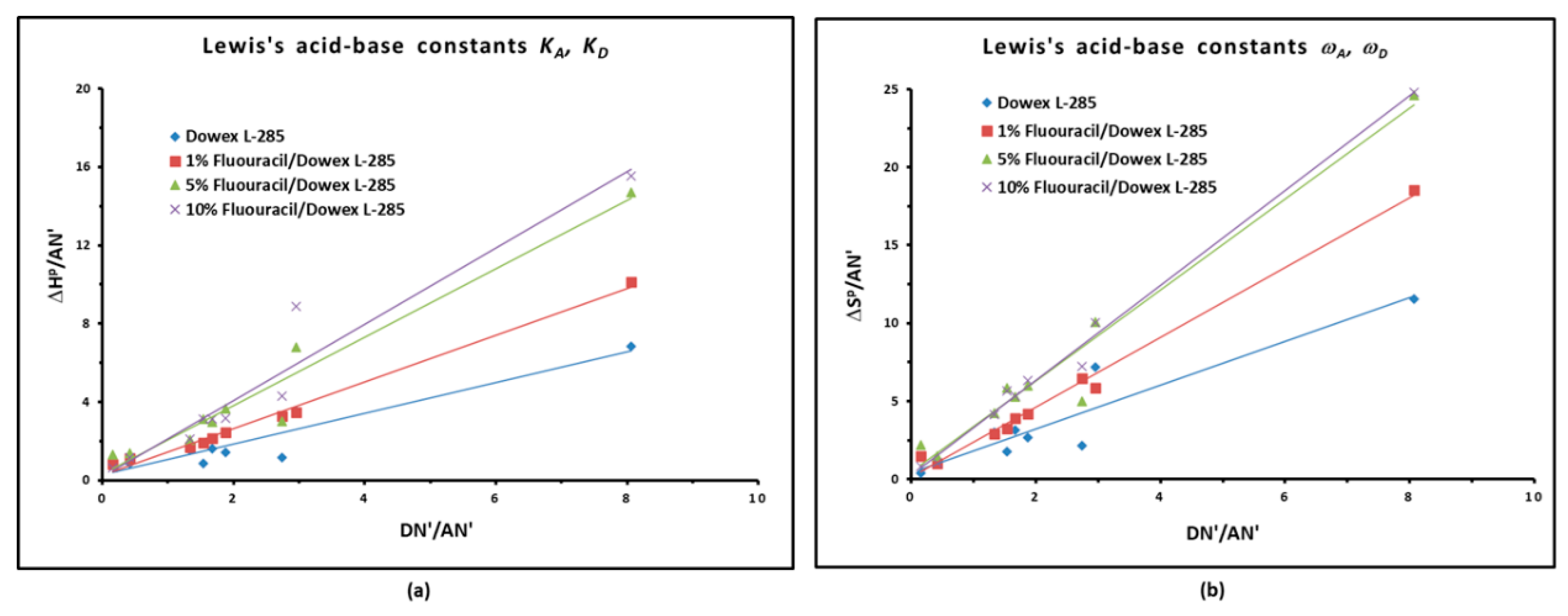

3.6. Determination of the Average Separation Distance H

3.7. Comparison with Previous Works and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Oliveira Reis, M.; de Sousa, R.G.; de Souza Medeiros Batista, A. Synthesis and characterization of poly(styrene-co-divinylbenzene) and nanomagnetite structures, Methods X, 2022, 9, 2022, 101764. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.S.M.; Mendes, M.S.L.; Neves, M.A.F.S.; Pedrosa, M.S.; Silva, M.R. Experimental design to evaluate the efficiency of maghemite nanoparticles incorporation in styrene-divinylbenzene copolymers, J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138(18), 50318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, R.; Toro, C.A.; Cuellar, J. Morphological characteristics of poly(styrene-co-divinylbenzene) microparticles synthesized by suspension polymerization, Powder Technol. 247 (2013) 279–288.

- Li, T.; Liu, H.; Zeng, L.; Yang, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z. Macroporous magnetic poly(styrene–divinylbenzene) nanocomposites prepared via magnetite nanoparticles-stabilized high internal phase emulsions, J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 12865–12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuurman, H.W., Köhler, J., Jansson, S.O. et al. Characterization of some commercial poly (styrene-divinylbenzene) copolymers for reversed-phase HPLC1 . Chromatographia 23, 341–349 (1987). [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, L., Coutinho, F.M.B., Teixeira, V.G. et al. Surface modification of styrene-divinylbenzene copolymers by polyacrylamide grafting via gamma irradiation . Polym. Bull. 61, 319–330 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Lazcano, A.A.; Hassan, D.; Pourmadadi, M.; shamsabadipour,A.; Behzadmehr, R.; Rahdar, A.; Medina, D.I.; Díez-Pascual,A.M. 5-Fluorouracil nano-delivery systems as a cutting-edge for cancer therapy, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2023, 246, 114995. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; El Hadad, S.; Aldahlawi, A. The development of a novel oral 5-Fluorouracil in-situ gelling nanosuspension to potentiate the anticancer activity against colorectal cancer cells, Int. J. Pharm., 2022, 613, 121406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olukman, M.; Sanli, O.; Solak, E.K.; Release of Anticancer Drug 5-Fluorouracil from Different Ionically Crosslinked Alginate Beads. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2012, 03, 469–479.

- Ortiz, R.; Cabeza, L.; Arias, J.L.; Melguizo, C.; Alvarez, P.J.; Velez, C.; Clares, B.; Aranega, A.; Prados, J. 2015. Poly(butylcyanoacrylate) and Poly(epsilon- caprolactone) Nanoparticles Loaded with 5-Fluorouracil Increase the Cytotoxic Effect of the Drug in Experimental Colon Cancer. AAPS J. 2015, 17, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishu, G. N.; Aggarwal, N. Stomach-specific drug delivery of 5-fluorouracil using floating alginate beads. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2007, 8, E143–E149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemiaszko, G.; Niemirowicz-Laskowska, K.; Markiewicz, K.H.; Dudź, E.; Milewska, S.; Misiak, P.; Kurowska, I.; Sadowska, A.; Car, H.; Wilczewsk, A.Z. Synergistic effect of folate-conjugated polymers and 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of colon cancer. Cancer Nano 12, 31 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kopeček, J. Smart and genetically engineered biomaterials and drug delivery systems, European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2003, 20 (1), 1-16.

- Singh P, Tyagi G, Mehrotra R, Bakhshi AK. Thermal stability studies of 5-fluorouracil using diffuse reflectance infrared spectroscopy. Drug Test Anal. 2009, 1(5), 240-244. [CrossRef]

- Bergbreiter, D.E. Polymer-supported reagents and catalysts in organic synthesis, Chemical Reviews, 2002, 102 (10), 3345-3384.

- Parisi, E.; Garcia, A.M.; Marson, D.; Posocco, P.; Marchesan, S. Supramolecular Tripeptide Hydrogel Assembly with 5-Fluorouracil. Gels. 2019, 5(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Xing, B. Adsorption mechanisms of organic chemicals on carbon nanotubes, Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42 (24), 9005-9013.

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Guo, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Yao, S.; Lin; X.; Chen, X. Preparation of Polar-Modified Styrene-Divinylbenzene Copolymer and Its Adsorption Performance for Comprehensive Utilization of Sugarcane Bagasse Dilute-Acid Hydrolysate. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 190, 423–436 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Vashurin, A. S.; Barabanov, V. M. Coordination and Sorption Capabilities of 5-fluouracil-Based Compounds. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2015, 85, 2287–2292. [Google Scholar]

- Pałasz, A.; Cież, D. In search of uracil derivatives as bioactive agents. Uracils and fused uracils: Synthesis, biological activity and applications, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2015, 97, 582–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuilov, P. Modified uracils in medicinal chemistry. Russian Chemical Reviews, 2016, 85(4), 374–390.

- Epure, E.L.; Moleavin, I.A.; Taran, E. Nguyen, A.V.; Nichita, N.; Hurduc, N. Azo-polymers modified with nucleobases and their interactions with DNA molecules. Polym. Bull. 2011, 67, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Yu.; Vereschetin, V.P.; Gromov, S.P.; Fedorova, O.A.; Alfimov, M.V.; Huesmann, H.; Möbius, D. Photosensitive supramolecular systems based on amphiphilic crown ethers, Supramol. Sci. 1997, 4, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gus’kov, V.Y.; Bilalova, R.V.; Kudasheva, F.K. Adsorption of organic molecules on a 5-fluouracil -modified porous polymer. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2017, 66, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainullina, Y.Y.; Gus’kov, V.Y.; Timofeeva, D.V. Polarity of Thymine and 6-Methyluracil-Modified Porous Polymers, According to Data from Inverse Gas Chromatography. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 2019, 93, 2477–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gus’kov, V.Y.; Gainullina, Y.Y.; Ivanov, S.P.; Kudasheva, F.K. Thermodynamics of organic molecule adsorption on sorbents modified with 5-fluouracil by inverse gas chromatography. Journal of chromatography. A, 2014, 1356, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gus’kov, V.Y.; Ivanov, S.P.; Khabibullina, R.A.; Garafutdinov, R.R.; Kudasheva, F.K. Gas chromatographic investigation of the properties of a styrene-divinylbenzene copolymer modified by 5-fluouracil. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 86, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T.; Gus'kov, V.Y. Surface Thermodynamic Properties of Styrene–Divinylbenzene Copolymer Modified by Supramolecular Structure of Melamine Using Inverse Gas Chromatography. Chemistry 2024, 6, 830–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T.; Gus’kov, V. Y. London Dispersive and Polar Surface Properties of Styrene–Divinylbenzene Copolymer Modified by 5-Hydroxy-6-Methyluracil using Inverse Gas Chromatography. Preprints 2025, 2025040852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conder, J.R.; Locke, D.C.; Purnell, J.H. Concurrent solution and adsorption phenomena in chromatography. I. J. Phys. Chem. 1969, 73, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conder, J.R.; Purnell, J.H. Gas chromatography at finite concentrations. Part 2.—A generalized retention theory. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1968, 64, 3100–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conder, J.R.; Purnell, J.H. Gas chromatography at finite concentrations. Part 1.—Effect of gas imperfection on calculation of the activity coefficient in solution from experimental data. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1968, 64, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, D.T.; Brookman, D.J. Thermodynamically based gas chromatographic retention index for organic molecules using salt-modified aluminas and porous silica beads. Anal. Chem. 1968, 40, 1847–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T.; Schultz, J. New approach to characterise physicochemical properties of solid substrates by inverse gas chromatography at infinite dilution. I. Some new methods to determine the surface areas of some molecules adsorbed on solid surfaces. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 969, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Flour, C.; Papirer, E. Gas-solid chromatography. A method of measuring surface free energy characteristics of short carbon fibers. 1. Through adsorption isotherms. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 1982, 21, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Flour, C.; Papirer, E. Gas-solid chromatography: Method of measuring surface free energy characteristics of short fibers. 2. Through retention volumes measured near zero surface coverage. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 1982, 21, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnet, J.-B.; Park, S.; Balard, H. Evaluation of specific interactions of solid surfaces by inverse gas chromatography. Chromatographia 1991, 31, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehimi, M.M.; Abel, M.-L.; Perruchot, C.; Delamar, M.; Lascelles, S.F.; Armes, S.P. The determination of the surface energy of conducting polymers by inverse gas chromatography at infinite dilution. Synth. Met. 1999, 104, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehimi, M.M.; Pigois-Landureau, E. Determination of acid–base properties of solid materials by inverse gas chromatography at infinite dilution. A novel empirical method based on the dispersive contribution to the heat of vaporization of probes. J. Mater. Chem. 1994, 4, 741–745. [Google Scholar]

- Brendlé, E.; Papirer, E. A new topological index for molecular probes used in inverse gas chromatography for the surface nanorugosity evaluation, 2. Application for the Evaluation of the Solid Surface Specific Interaction Potential. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 194, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendlé, E.; Papirer, E. A new topological index for molecular probes used in inverse gas chromatography for the surface nanorugosity evaluation, 1. Method of Evaluation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 194, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. Surface acid-base properties of carbon fibres. Adv. Powder Technol. 1997, 8, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Vu, H.; Nguyen, S.H.; Dang, K.Q.; Pham, C.V.; Le, H.T. The Effect of Oxidation Temperature on Activating Commercial Viscose Rayon-Based Carbon Fibers to Make the Activated Carbon Fibers (ACFs). Mater. Sci. Forum 2020, 985, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, M. Optimization for testing conditions of inverse gas chromatography and surface energies of various carbon fiber bundles. Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Kondor, A.; Mitra, S.; Thua, K.; Harish, S.; Saha, B.B. On surface energy and acid–base properties of highly porous parent and surface treated activated carbons using inverse gas chromatography. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 69, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. Study of the temperature effect on the surface area of model organic molecules, the dispersive surface energy and the surface properties of solids by inverse gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1627, 461372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamieh, T.; Ahmad, A.A.; Roques-Carmes, T.; Toufaily, J. New approach to determine the surface and interface thermodynamic properties of H-β-zeolite/rhodium catalysts by inverse gas chromatography at infinite dilution. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamieh, T. New methodology to study the dispersive component of the surface energy and acid–base properties of silica particles by inverse gas chromatography at infinite dilution. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2022, 60, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. New Physicochemical Methodology for the Determination of the Surface Thermodynamic Properties of Solid Particles. AppliedChem 2023, 3, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.; Meyer, R.; Czihal, S.; Bertmer, M.; Decker, U.; Naumov, S.; Uhlig, H.; Steinhart, M.; Enke, D. Functionalization of porous siliceous materials, Part 2: Surface characterization by inverse gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1603, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Wu, D.; Heng, J.Y.Y.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Hadjittofis, E.; Su, W.; Tang, J.; Zhao, H.; Wu, W. Comparative study of surface properties determination of colored pearl-oyster-shell-derived filler using inverse gas chromatography method and contact angle measurements. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2017, 78, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidqi, M.; Balard, H.; Papirer, E.; Tuel, A.; Hommel, H.; Legrand, A. Study of modified silicas by inverse gas chromatography. Influence of chain length on the conformation of n-alcohols grafted on a pyrogenic silica. Chromatographia 1989, 27, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyda, M.M.; Guiochon, G. Surface properties of silica-based adsorbents measured by inverse gas–solid chromatography at finite concentration. Langmuir 1997, 13, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. Serious irregularities and errors in the determination of the surface free energy and acido-basicity of MXene materials, Carbon, 2025, 120209. [CrossRef]

- Thielmann, F.; Baumgarten, E. Characterization of Microporous Aluminas by Inverse Gas Chromatography. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 229, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onjia, A.E.; Milonjić, S.K.; Todorović, M.; Loos-Neskovic, C.; Fedoroff, M.; Jones, D.J. An inverse gas chromatography study of the adsorption of organics on nickel- and copper-hexacyanoferrates at zero surface coverage. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 251, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyszewska, M.; Krzywania, A.; Zaborski, M.; Szynkowska, M.I. Surface properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles studied by inverse gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 5284–5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Heng, J.; Nikolaev, A.; Waters, K. Introducing inverse gas chromatography as a method of determining the surface heterogeneity of minerals for flotation. Powder Technol. 2013, 249, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Bertóti, I.; Pukánszky, B.; Rosa, R.; Lazzeri, A. Structure and surface coverage of water-based stearate coatings on calcium carbonate nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 362, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamieh , T. Comment on “New Method to Probe the Surface Properties of Polymer Thin Films by Two-Dimensional (2D) Inverse Gas Chromatography (iGC)”, Langmuir, 2024, 40 (44), 23562–23569. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Gong, M. Preparation of Toluene-Imprinted Homogeneous Microspheres and Determination of Their Molecular Recognition Toward Template Vapor by Inverse Gas Chromatography. Chromatographia 2017, 80, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenhofer, E.; Cho, J.; Yu, J.; Al-Saigh, Z.Y.; Kim, J. Adsorption of hydrocarbons commonly found in gasoline residues on household materials studied by inverse gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1594, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloglou, A.; Martakidis, K.; Gavril, D. An inverse gas chromatographic methodology for studying gas-liquid mass transfer. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1480, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. Inverse Gas Chromatography to Characterize the Surface Properties of Solid Materials. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 2231–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. Some Irregularities in the Evaluation of Surface Parameters of Solid Materials by Inverse Gas Chromatography. Langmuir 2023, 39, 17059–17070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, T. New Progress on London Dispersive Energy, Polar Surface Interactions, and Lewis’s Acid–Base Properties of Solid Surfaces. Molecules 2024, 29, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamieh, T. London Dispersive and Lewis Acid-Base Surface Energy of 2D Single-Crystalline and Polycrystalline Covalent Organic Frameworks. Crystals 2024, 14, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oss, C.J.; Good, R.J.; Chaudhury, M.K. Additive and nonadditive surface tension components and the interpretation of contact angles. Langmuir. 1988, 4, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorris, G.M.; Gray, D.G. Adsorption of n-alkanes at zero surface coverage on cellulose paper and wood fibers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1980, 77, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Copolymer | (mJ/m2) | R2 | (mJ m−2 K−1) | (mJ/m2) | (K) |

| S-DVB | = -3.048 T + 1515 | 0.9986 | -3.048 | 1515.0 | 497.1 |

| 1% 5-FU / S-DVB | = -0.107 T + 145.05 | 0.9276 | -0.107 | 145.1 | 1351.8 |

| 5% 5-FU / S-DVB | = 0.337 T - 50.531 | 0.986 | 0.337 | -50.5 | 149.9 |

| 10% 5-FU / S-DVB | = 0.826 T - 266.14 | 0.9947 | 0.826 | -266.1 | 322.1 |

| Parameter | Equation | R² |

| = 0.109 % 5-FU + 0.986 | 0.8804 | |

| = -0.009 % 5-FU + 0.293 | 0.8655 | |

| = -0.022 % 5-FU + 0.300 | 0.8048 | |

| =0.100 % 5-FU + 1.279 | 0.8025 | |

| = 0.142 % 5-FU + 1.824 | 0.7003 | |

| = 0.001 % 5-FU + 0.363 | 0.7541 | |

| / | / = -0.011 % 5-FU + 0.211 | 0.7647 |

| = 0.143 %5-FU + 2.187 | 0.8592 |

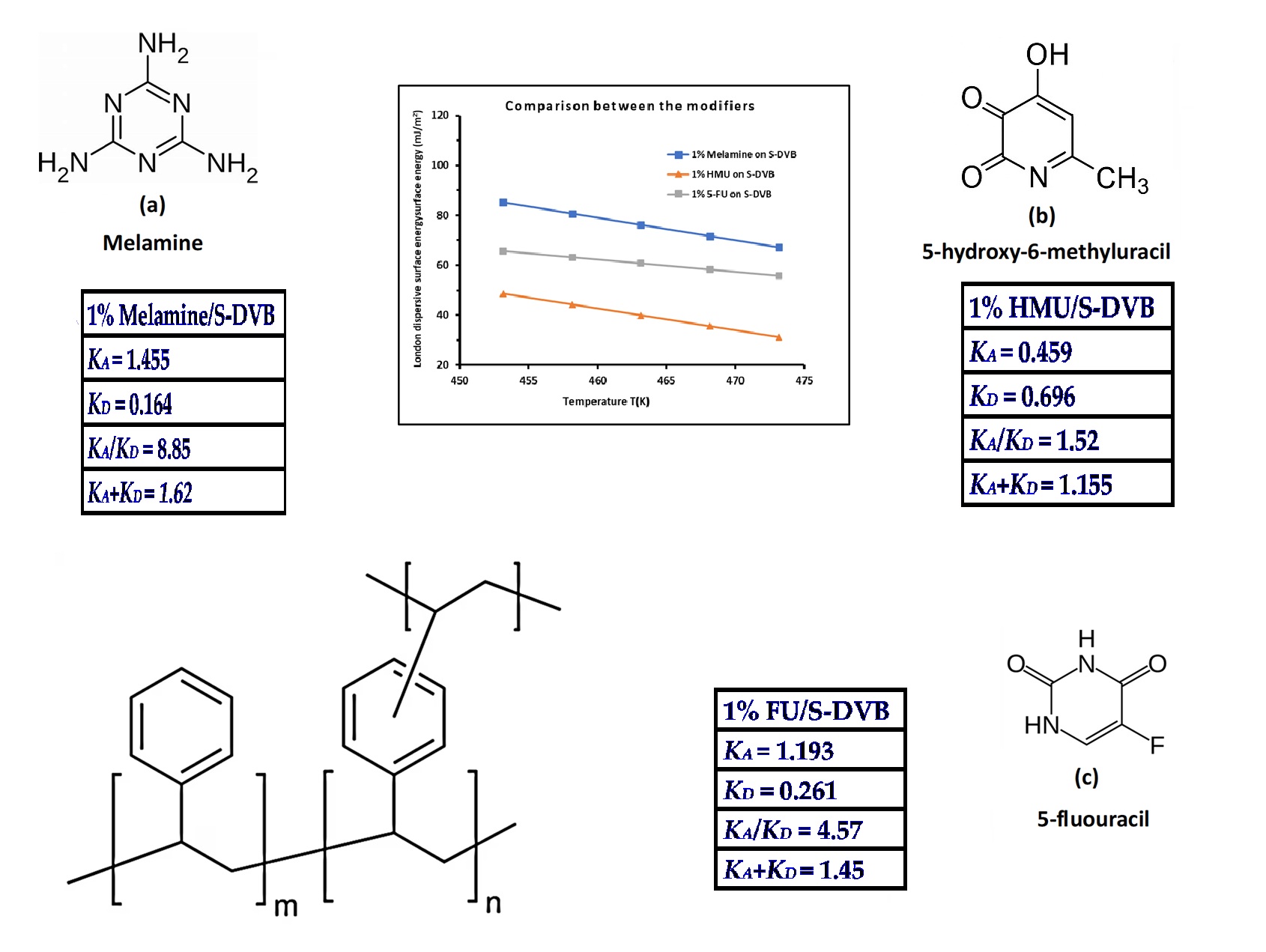

| Modified copolymer | KA | KD | KA/KD | KA+KD | R2 | 10−3ωA | 10−3ωD | ωA/ωD | 10−3 (ωA+ ωD) | R2 |

| 1% Melamine/S-DVB | 1.455 | 0.164 | 8.85 | 1.620 | 0.9783 | 0.09 | 2.81 | 0.03 | 2.90 | 0.9316 |

| 1% HMU/S-DVB | 0.459 | 0.696 | 1.52 | 1.155 | 0.9561 | 0.81 | 1.64 | 0.49 | 2.45 | 0.975 |

| 1% 5-FU/S-DVB | 1.193 | 0.261 | 4.57 | 1.45 | 0.9909 | 2.24 | 0.12 | 2.37 | 18.1 | 0.9904 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).