Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Synthesis of Co3O4 NPs

2.2. Characterization of the Cobalt Oxide

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

2.4. Biological Activities

2.4.1. Well-Diffusion Inhibition Assays

2.4.2. Spread Plate Technique for Antifungal Assay

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Characterization

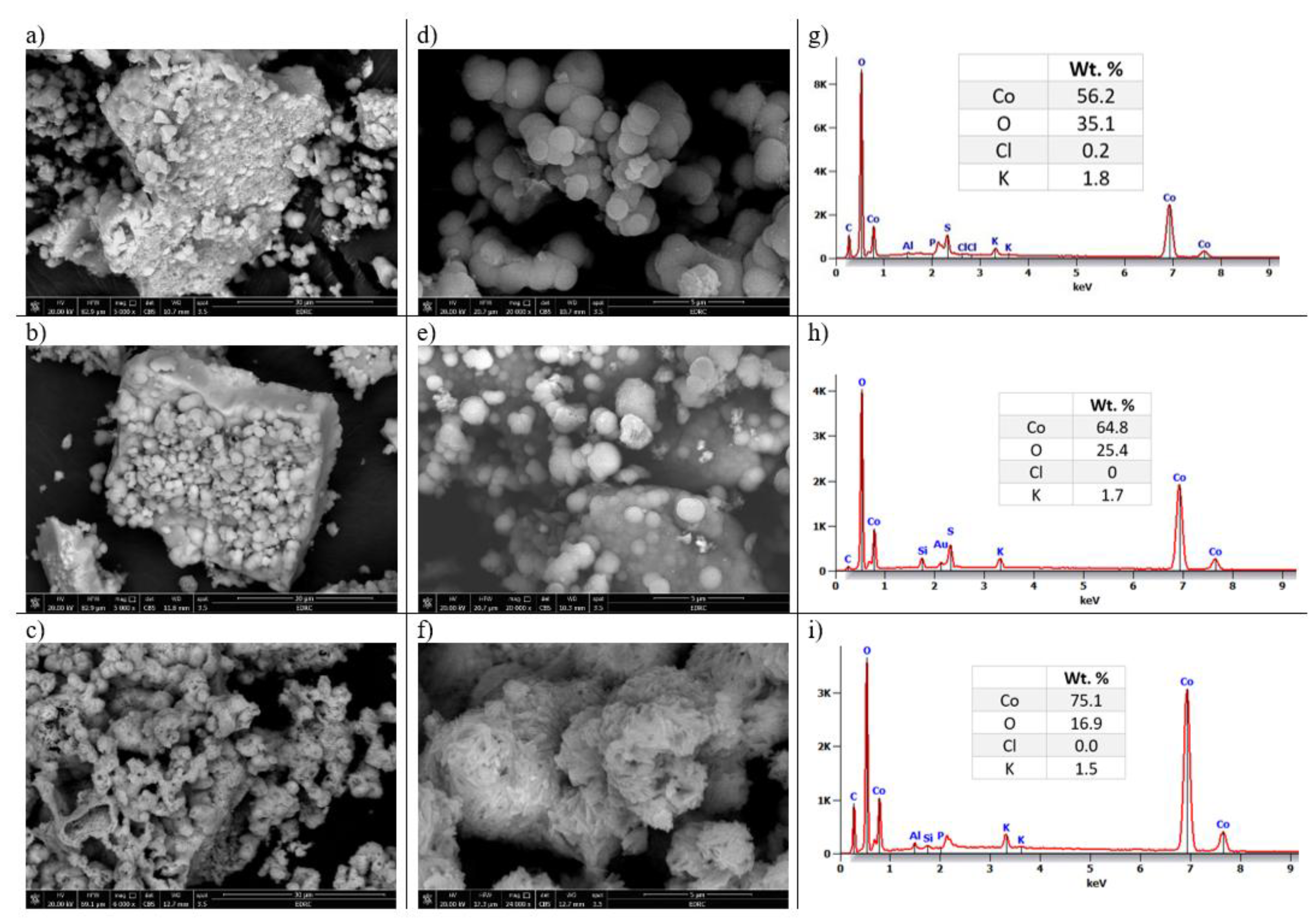

3.1.1. SEM and EDS

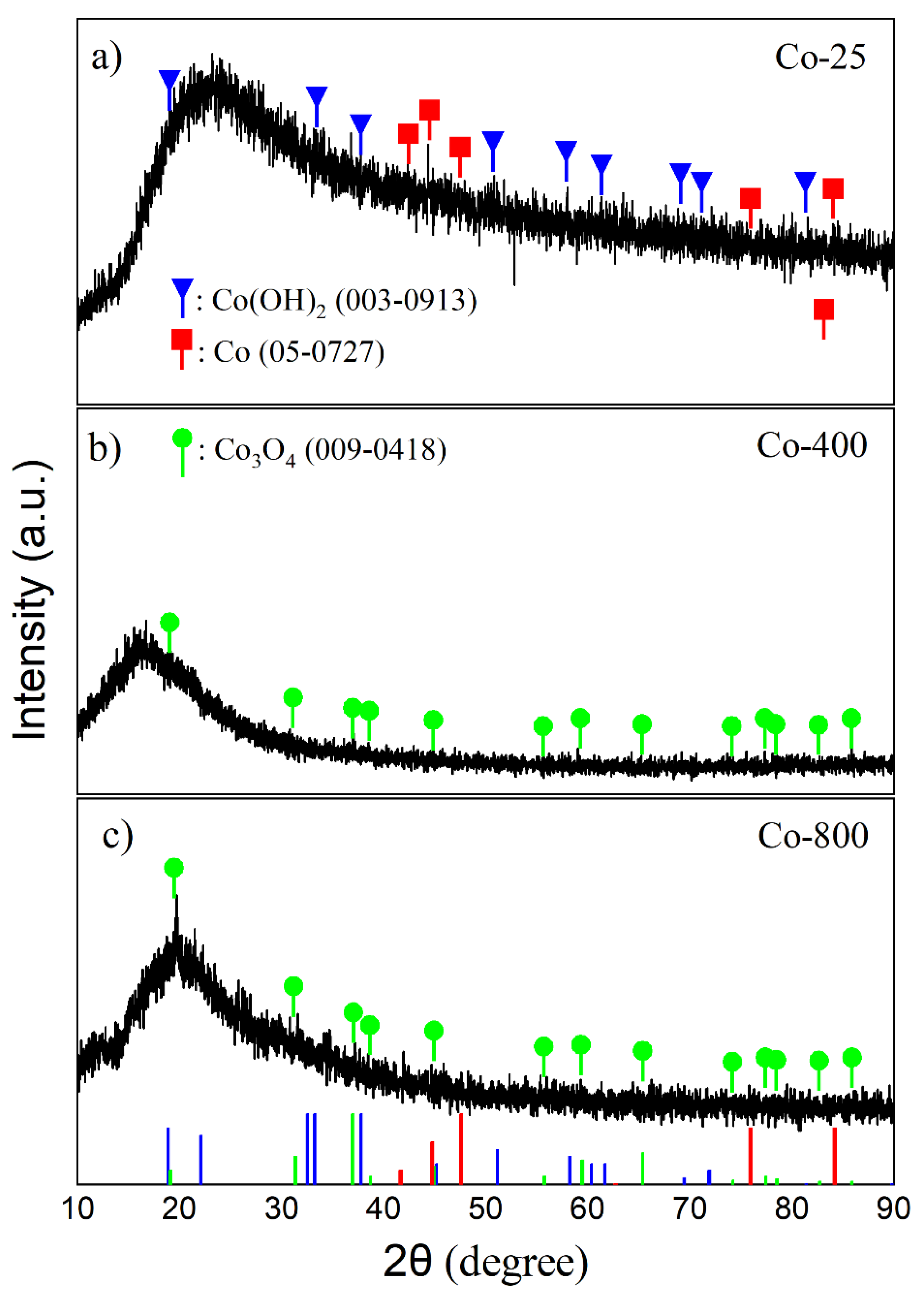

3.1.2. XRD

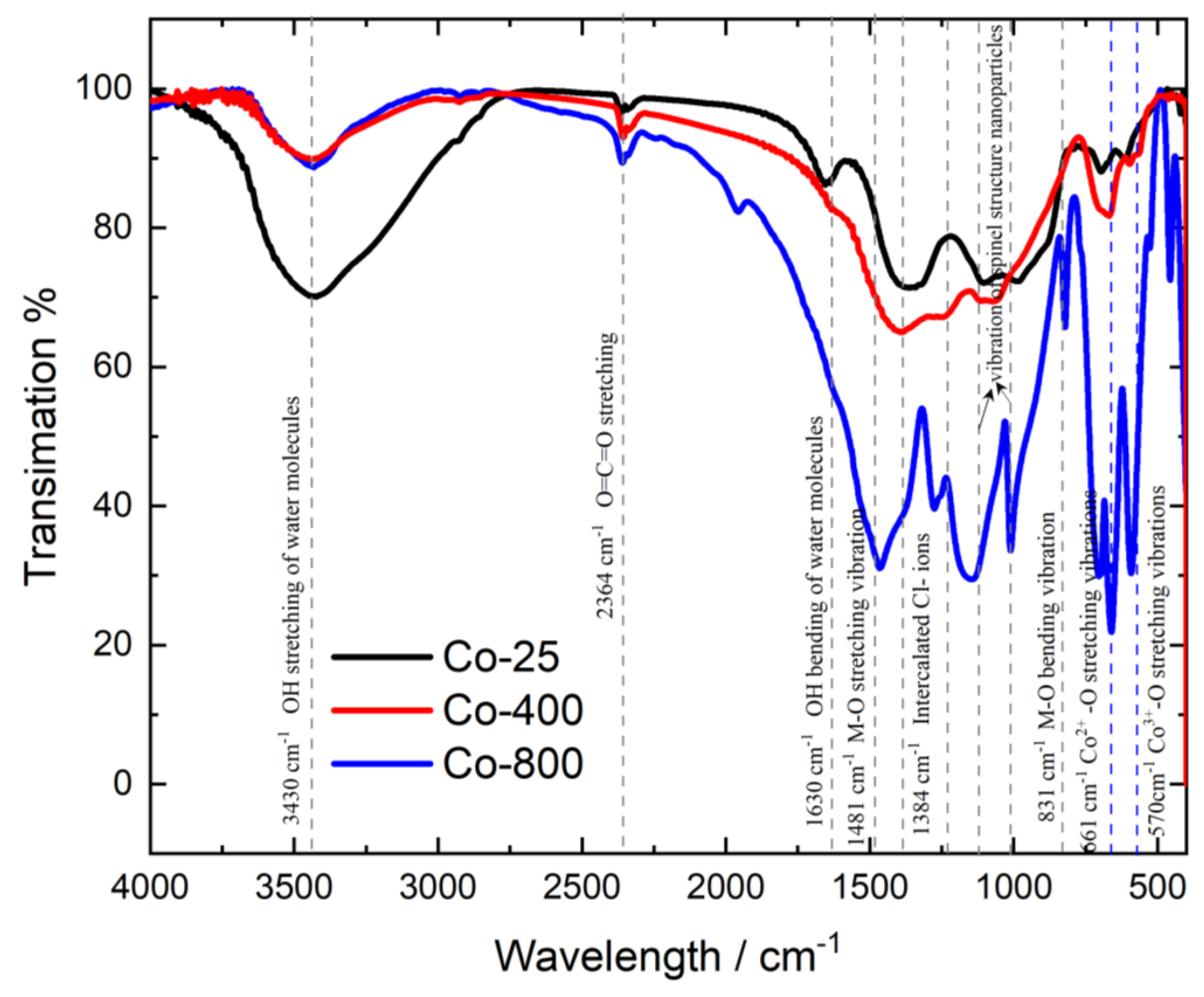

3.1.3. FTIR

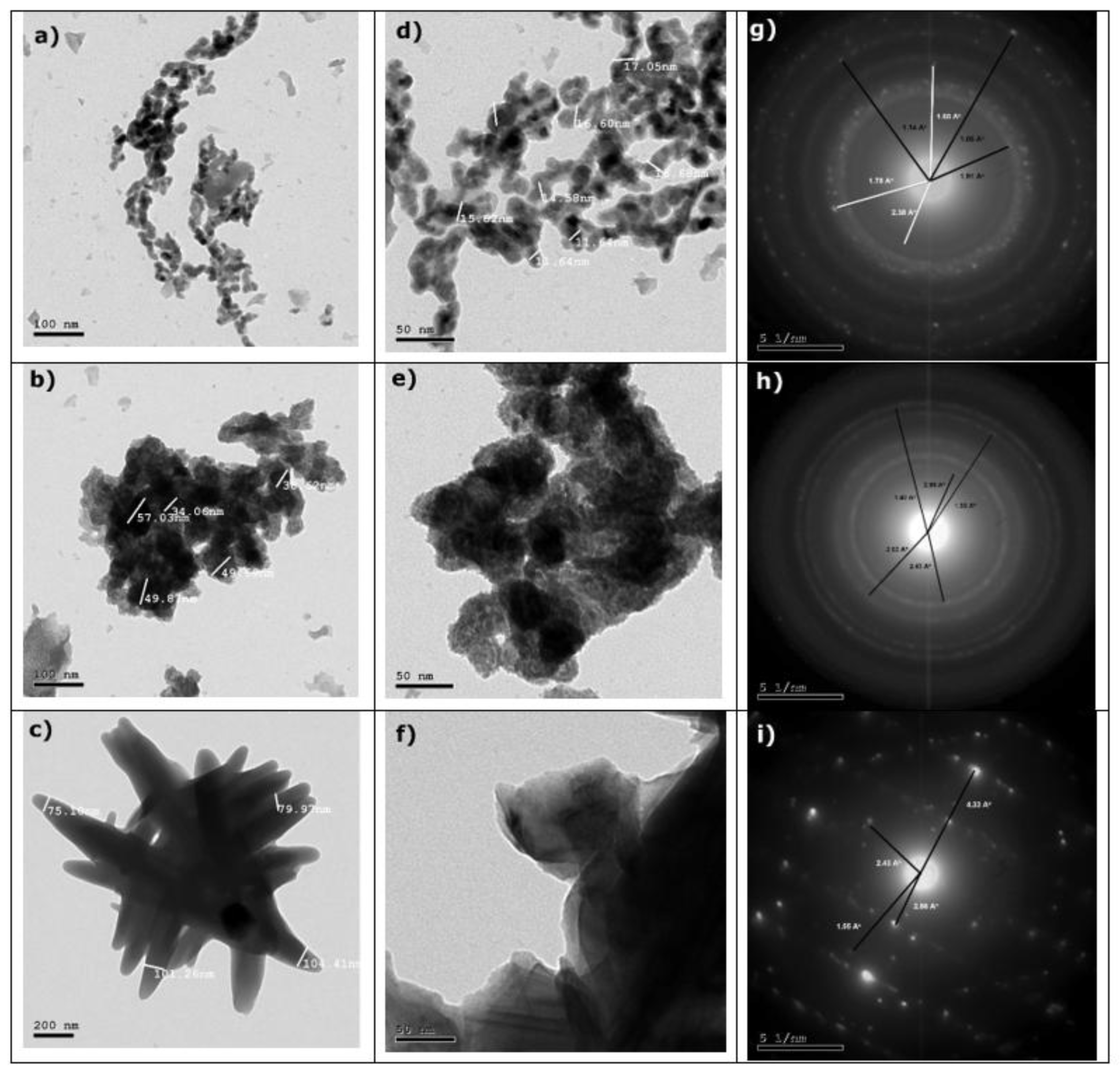

3.1.4. HRTEM

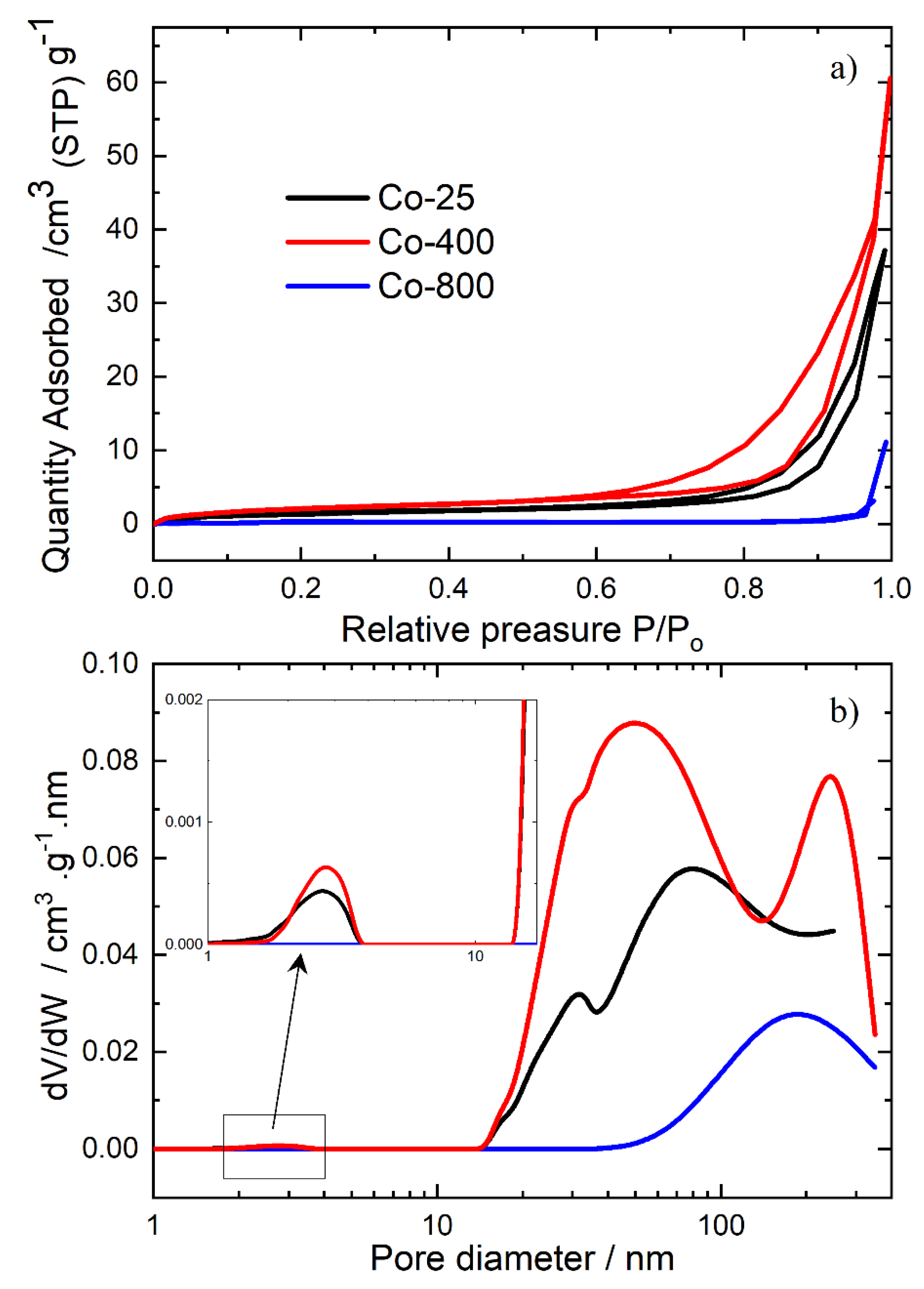

3.1.4. Analysis of Surface Area and Pore Size

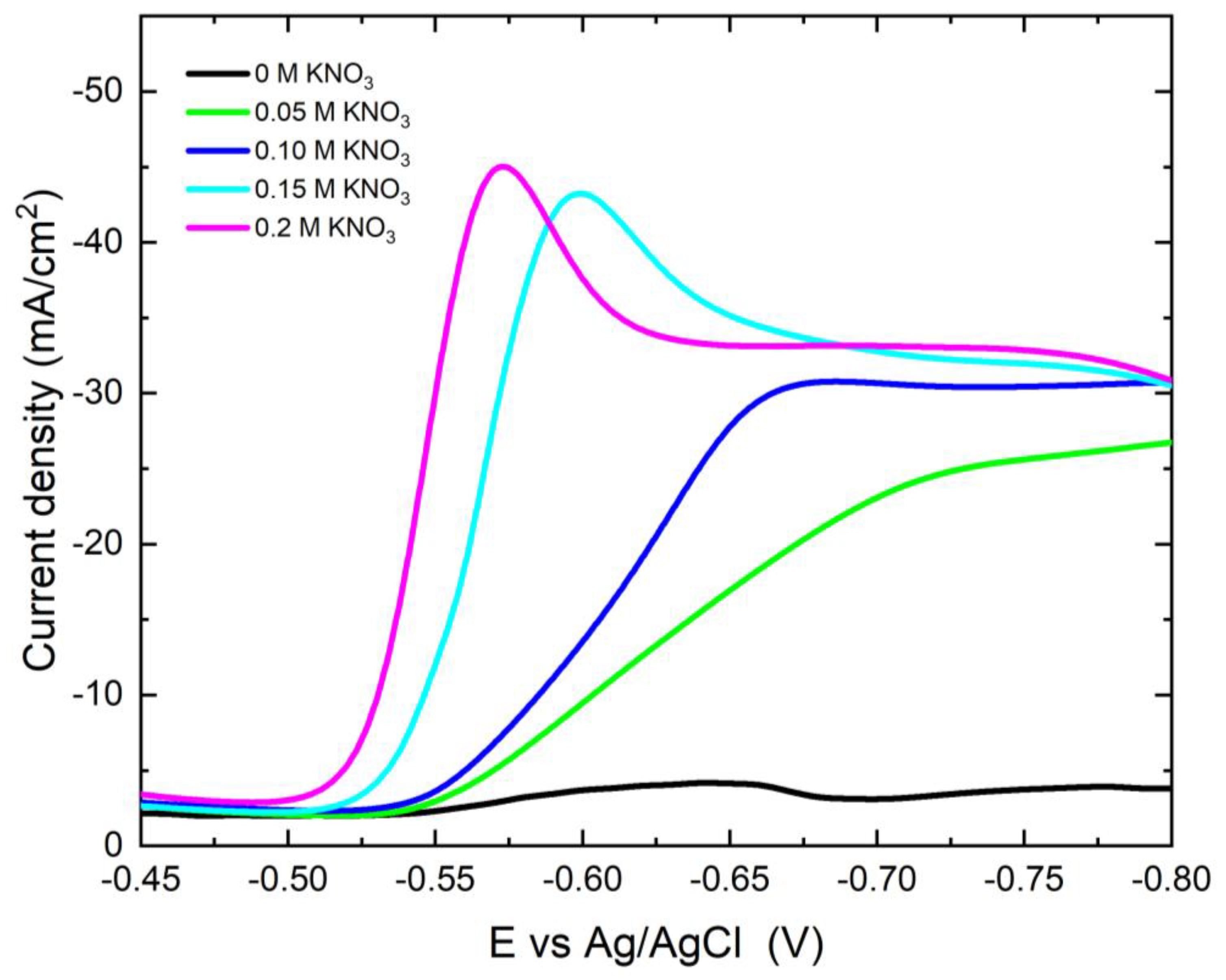

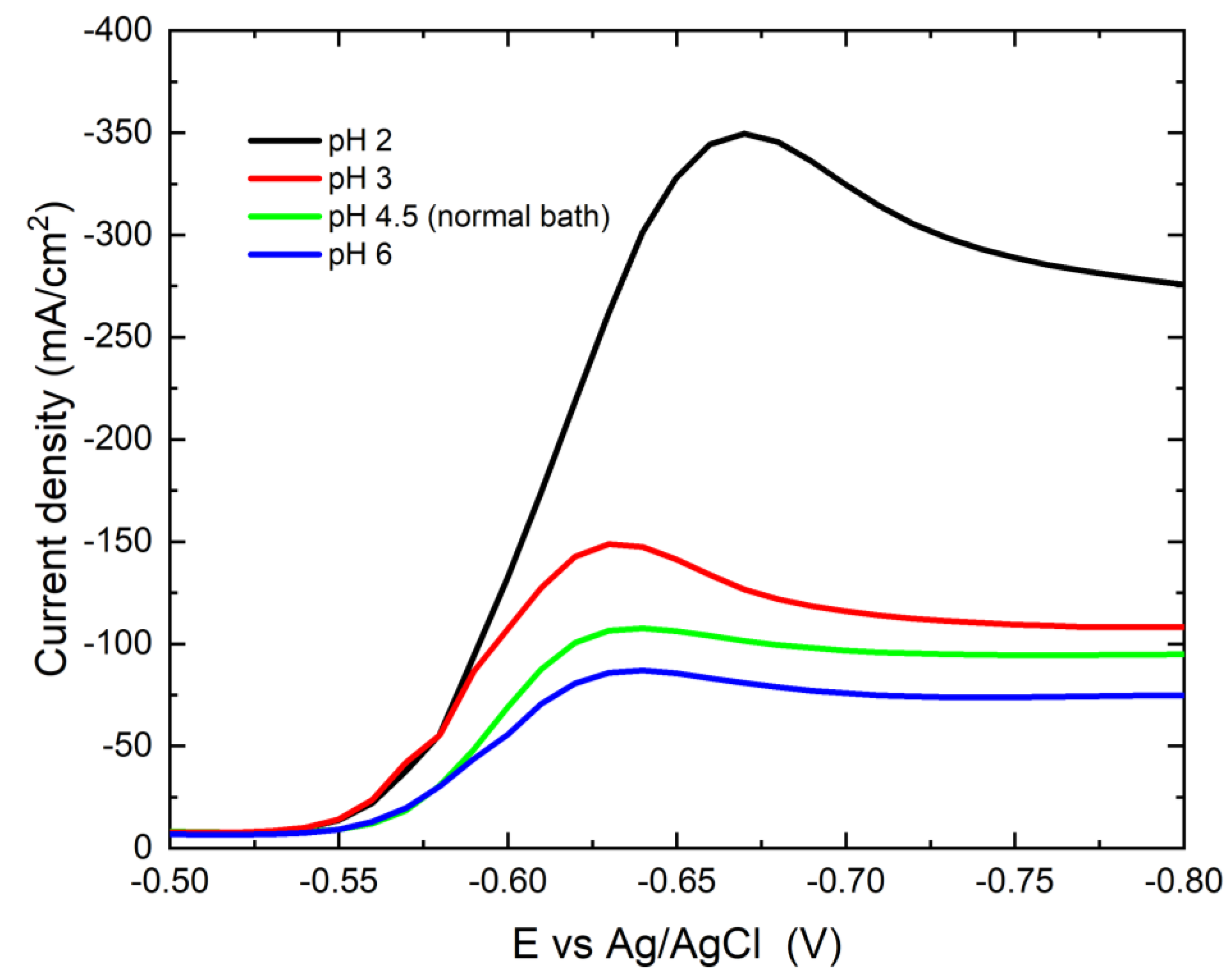

3.2. Electrochemical Studies

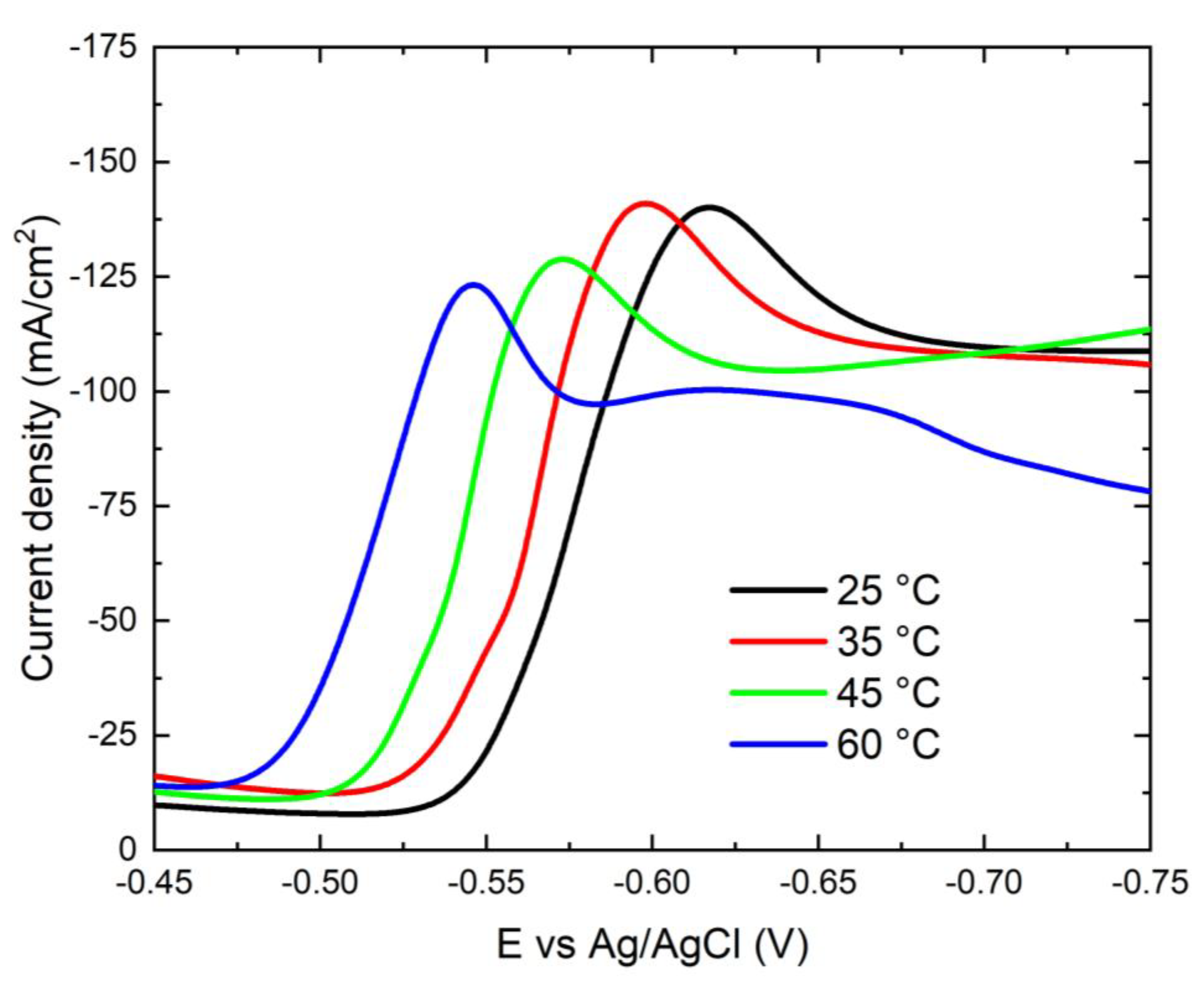

3.2.1. Potentiodynamic Polarization Behavior

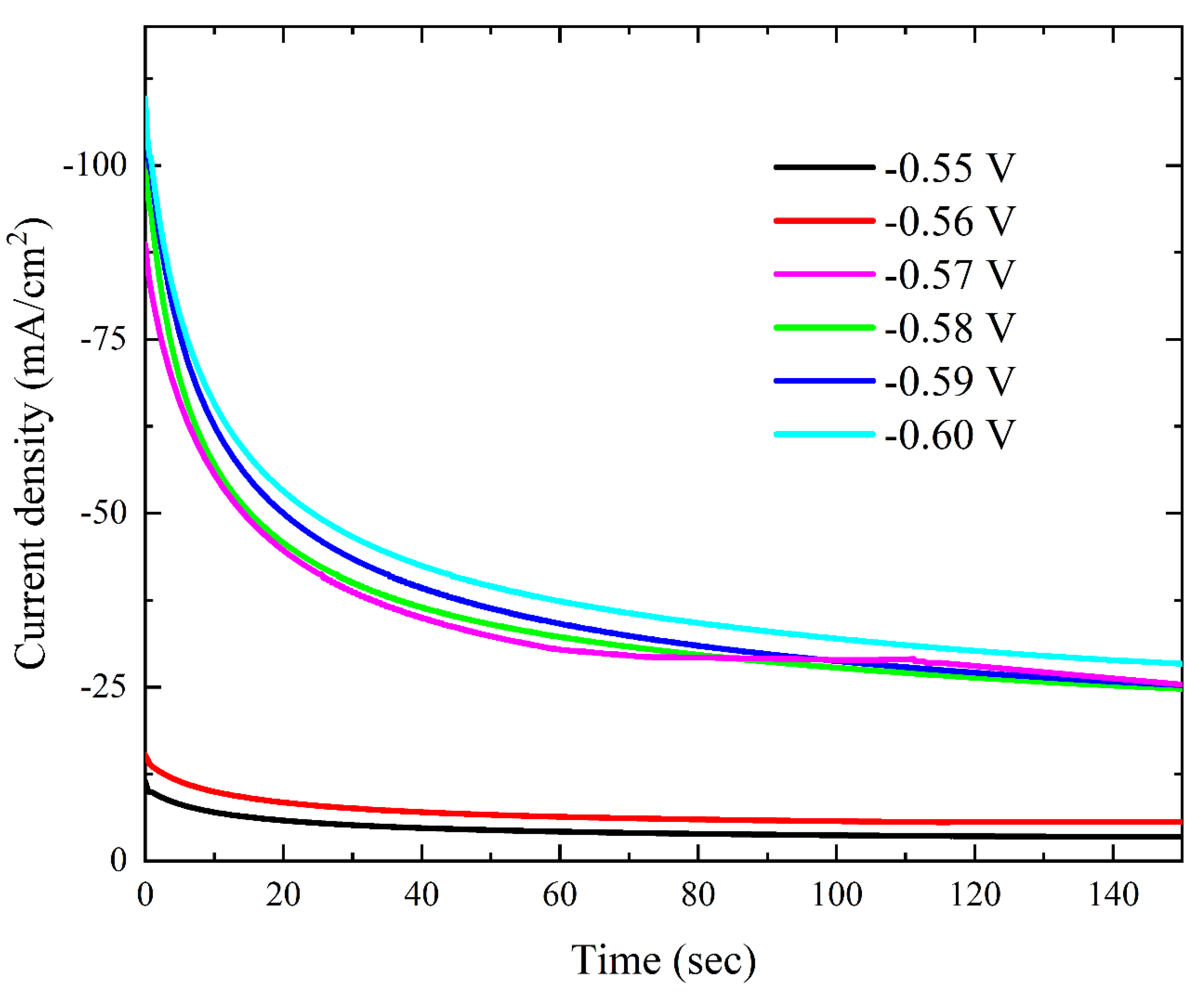

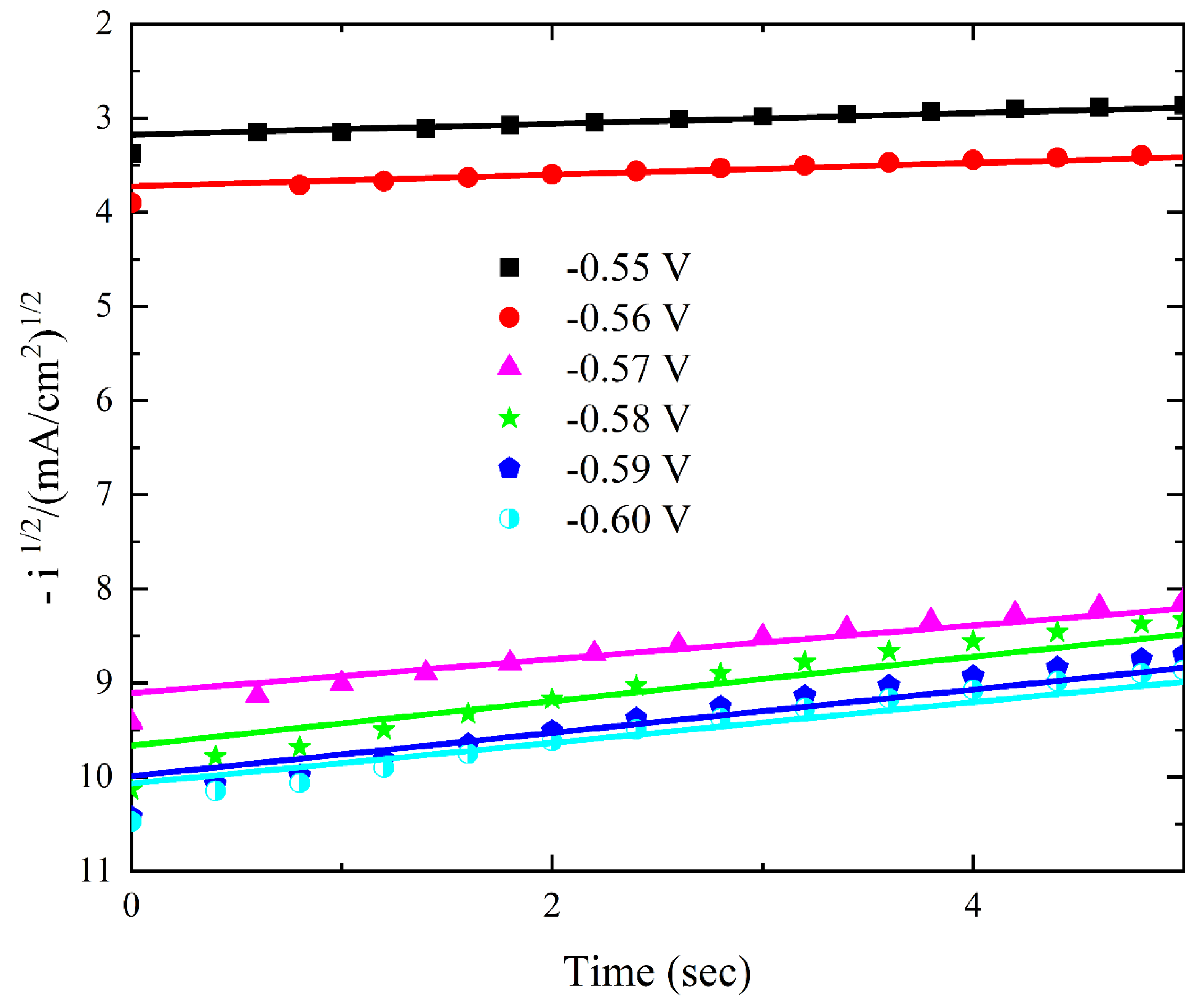

3.2.2. Chronoamperometric Analysis

3.3. Biological Activities of Co3O4 NPs

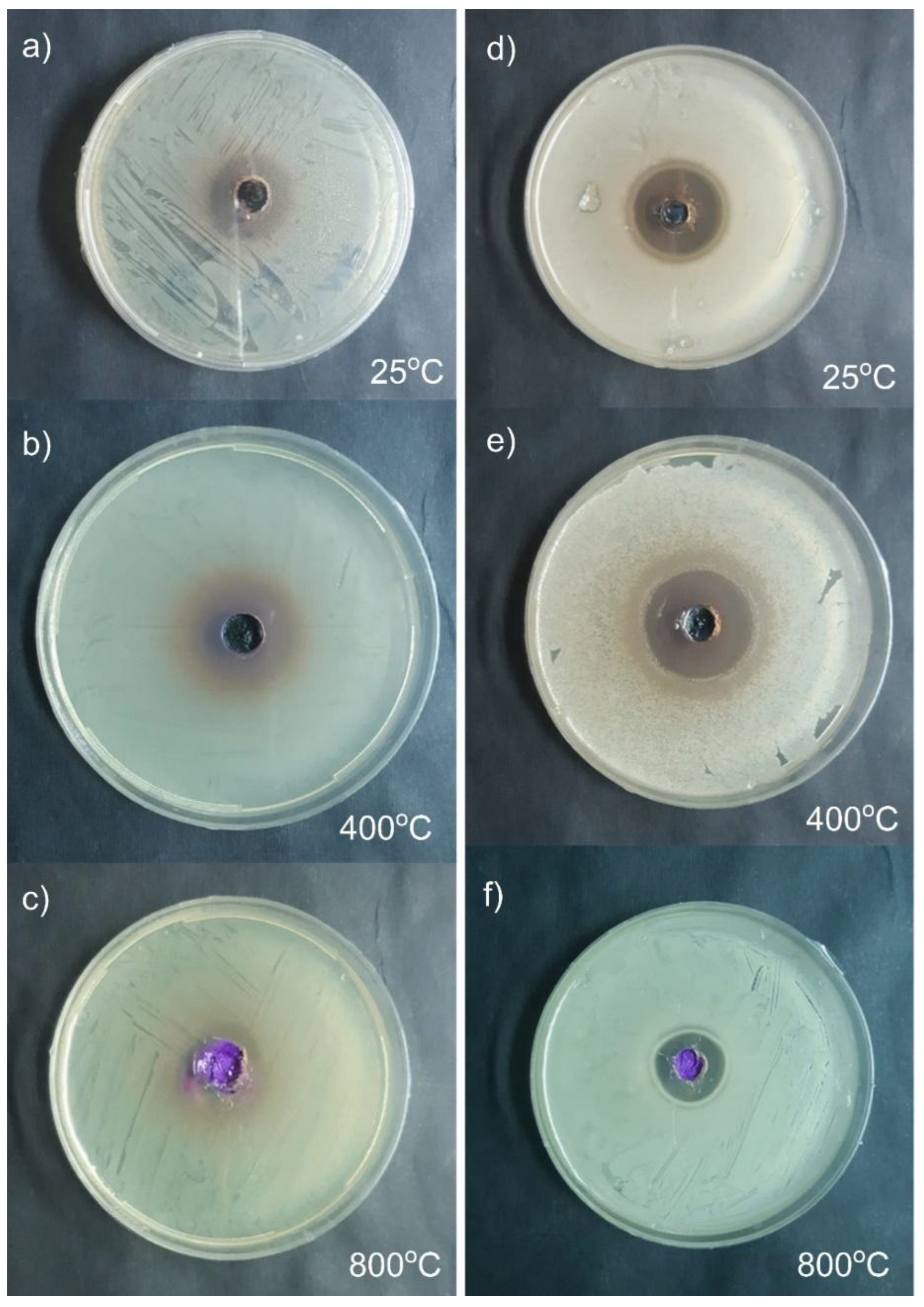

3.3.1. Anti-Bacterial Activity

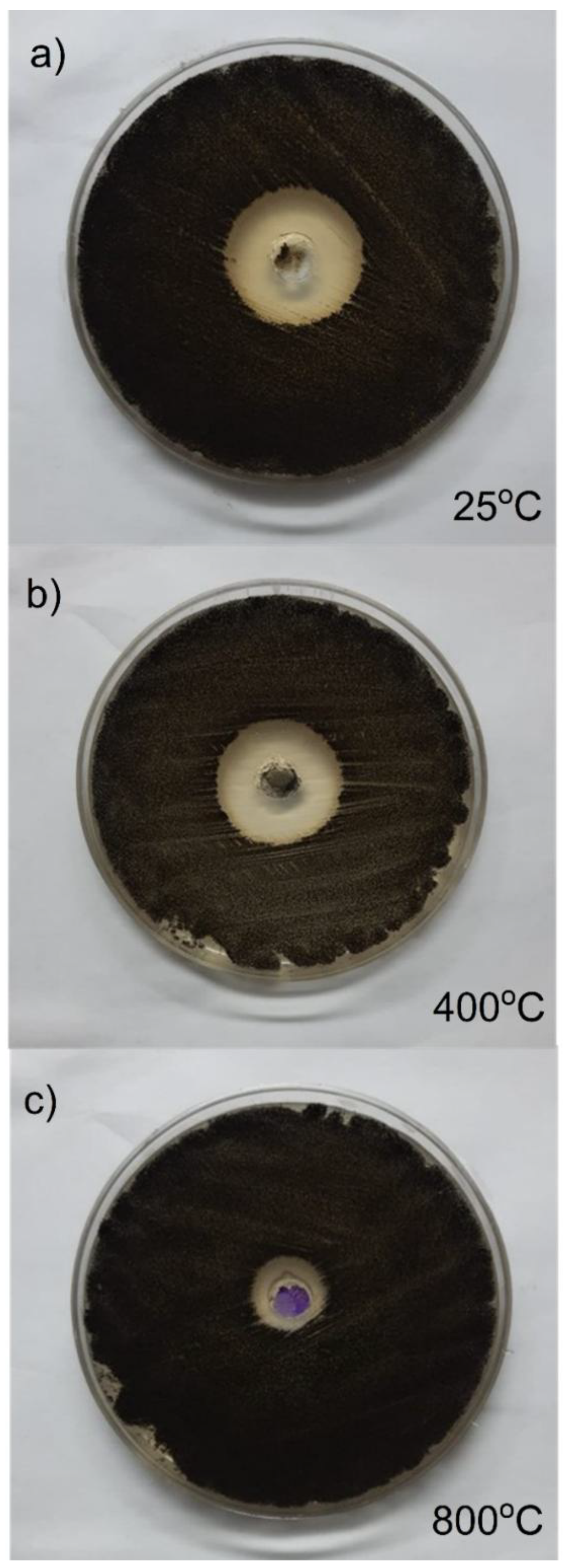

3.3.2. Anti-Fungal Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

References

- El-Shafie, A.S.; Ahsan, I.; Radhwani, M.; Al-Khangi, M.A.; El-Azazy, M. Synthesis and Application of Cobalt Oxide (Co3O4)-Impregnated Olive Stones Biochar for the Removal of Rifampicin and Tigecycline: Multivariate Controlled Performance. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, A.S.; Oyekunle, J.A.; Durosinmi, L.M.; Oluwafemi, O.S.; Olayanju, D.S.; Akinola, A.S.; Obisesan, O.R.; Akinyele, O.F.; Ajayeoba, T.A. Potential of cobalt and cobalt oxide nanoparticles as nanocatalyst towards dyes degradation in wastewater. Nano-Structures Nano-Objects 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Boraei, N.; Ibrahim, M. Black binary nickel cobalt oxide nano-powder prepared by cathodic electrodeposition; characterization and its efficient application on removing the Remazol Red textile dye from aqueous solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 238, 121894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Boraei, N.F.; Ibrahim, M.; Kamal, R. Facile synthesis of mesoporous ncCoW powder via electrodeposition; characterization and its efficient application on hydrogen generation and organic pollutants reduction. Surfaces Interfaces 2023, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, R.; Ahmad, N.; Alam, M.; Ahmad, J. The development of cobalt oxide nanoparticles based electrode to elucidate the rapid sensing of nitrophenol. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, R.; Biswal, A.; Dash, B.; Sanjay, K.; Subbaiah, T.; Shin, S. Samal, R.; Biswal, A.; Dash, B.; Sanjay, K.; Subbaiah, T.; Shin, S. In Preparation and characterization of cobalt oxide by electrochemical technique, XIII International Seminar on Mineral Processing Technology (MPT-2013), 2013.

- Abdel-Samad, H.S.; El-Jemni, M.A.; El Rehim, S.S.A.; Hassan, H.H. Simply prepared α-Ni(OH)2-based electrode for efficient electrocatalysis of EOR and OER. Electrochimica Acta 2024, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jemni, M.A.; Abdel-Samad, H.S.; AlKordi, M.H.; Hassan, H.H. Normalization of the EOR catalytic efficiency measurements based on RRDE study for simply fabricated cost-effective Co/graphite electrode for DAEFCs. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jemni, M.A.; Abdel-Samad, H.S.; Essa, A.S.; Hassan, H.H. Controlled electrodeposited cobalt phases for efficient OER catalysis, RRDE and eQCM studies. Electrochimica Acta 2019, 313, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Ponnalagi, A.K.; Nagamuthu, S.; Muralidharan, G. Microwave assisted synthesis of Co3O4 nanoparticles for high-performance supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2013, 106, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Huang, Q.; Li, X.-Y.; Yang, S. Iron nanoparticles: Synthesis and applications in surface enhanced Raman scattering and electrocatalysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001, 3, 1661–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.K.; Shah, D.V.; Roy, D.R. Green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica and its antibacterial activity for medicinal applications. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 095033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliani, M.; Jalal, R.; Goharshadi, E.K. Effects of pH and Temperature on Antibacterial Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanofluid Against E. coliO157:H7 and Staphylococcus aureus. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2015, 8, e17115–e17115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayanwale, A.P.; Estrada-Capetillo, B.L.; Reyes-López, S.Y. Evaluation of Antifungal Activity by Mixed Oxide Metallic Nanocomposite against Candida spp. Processes 2021, 9, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, C.; Raji, P. Facile-synthesis and characterization of cobalt oxide (Co3O4) nanoparticles by using Arishta leaves assisted biological molecules and its antibacterial and antifungal activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Saikia, B.J. Synthesis, characterization and biological applications of cobalt oxide (Co3O4) nanoparticles. Chem. Phys. Impact 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, S.; Safabakhsh, J.; Zaringhadam, P. , Synthesis, characterization, and investigation of optical and magnetic properties of cobalt oxide (Co 3 O 4) nanoparticles. Journal of Nanostructure in Chemistry 2013, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradpoor, H.; Safaei, M.; Rezaei, F.; Golshah, A.; Jamshidy, L.; Hatam, R.; Abdullah, R.S. Optimisation of Cobalt Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesis as Bactericidal Agents. Open Access Maced. J. Med Sci. 2019, 7, 2757–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetim, N.K. Hydrothermal synthesis of Co3O4 with different morphology: Investigation of magnetic and electrochemical properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1226, 129414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Chong, M.N.; Phuan, Y.W.; Ocon, J.D.; Chan, E.S. Effects of electrodeposition synthesis parameters on the photoactivity of nanostructured tungsten trioxide thin films: Optimisation study using response surface methodology. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 61, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.M.; Slipper, I.J.; Antonijević, M.D.; Nikolić, G.S.; Mitrović, J.Z.; Bojić, D.V.; Bojić, A.L. Characterization of a Bi2O3 coat based anode prepared by galvanostatic electrodeposition and its use for the electrochemical degradation of Reactive Orange 4. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 50, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, I. G.; Di Fonzo, D. A. , Anodic electrodeposition of cobalt oxides from an alkaline bath containing Co-gluconate complexes on glassy carbon. An electroanalytical investigation. Electrochimica acta 2011, 56, (22), 7536–7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisnund, S.; Blay, V.; Muamkhunthod, P.; Thunyanon, K.; Pansalee, J.; Monkrathok, J.; Maneechote, P.; Chansaenpak, K.; Pinyou, P. Electrodeposition of Cobalt Oxides on Carbon Nanotubes for Sensitive Bromhexine Sensing. Molecules 2022, 27, 4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moridon, S.N.F.; Salehmin, M.I.; Mohamed, M.A.; Arifin, K.; Minggu, L.J.; Kassim, M.B. Cobalt oxide as photocatalyst for water splitting: Temperature-dependent phase structures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 25495–25504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Krishnan, K.M. Preparation of functionalized and gold-coated cobalt nanocrystals for biomedical applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 293, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya, K.U.; Govindaraju, K.; Kumar, V.G.; Dhas, T.S.; Karthick, V.; Singaravelu, G.; Elanchezhiyan, M. Blue green alga mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles and its antibacterial efficacy against Gram positive organisms. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 47, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, N.J.; Vali, D.N.; Rani, M.; Rani, S.S. Evaluation of antioxidant, antibacterial and cytotoxic effects of green synthesized silver nanoparticles by Piper longum fruit. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 34, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, J. H. , Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi: approved standard. (No Title) 2008.

- Frost, R.L.; Kristof, J.; Paroz, G.N.; Kloprogge, J. Role of Water in the Intercalation of Kaolinite with Hydrazine. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1998, 208, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-A.; Xie, Y.-L.; Wang, Y.-X.; Xie, L.-J.; Fu, G.-R.; Jin, X.-Q.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Wu, H.-Y. , Synthesis of α-cobalt hydroxides with different intercalated anions and effects of intercalated anions on their morphology, basal plane spacing, and capacitive property. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2009, 113, (28), 12502–12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nethravathi, C.; Viswanath, B.; Sebastian, M.; Rajamathi, M. Exfoliation of α-hydroxides of nickel and cobalt in water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 345, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ma, W.; Wang, L.; Xue, J. Preparation of α-Co(OH)2 monolayer nanosheets by an intercalation agent-free exfoliation process. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2015, 78, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W. , The magnetic structure of Co3O4. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 1964, 25, (1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, M.; Subramani, A.; Ubaidullah, M.; Shaikh, S.F.; Pandit, B.; Jesudoss, S.K.; Kamalakannan, M.; Yuvaraj, S.; Subudhi, P.S.; Dash, C.S. Synthesis, Characterization and In Vitro Cytotoxic Effects of Cu:Co3O4 Nanoparticles Via Microwave Combustion Method. J. Clust. Sci. 2022, 33, 1821–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaedini, G.; Muhammad, A. Study of influential factors in synthesis and characterization of cobalt oxide nanoparticles. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-C.; Lu, A.-H.; Guo, S.-C. Characterization of the microstructures of organic and carbon aerogels based upon mixed cresol–formaldehyde. Carbon 2001, 39, 1989–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, J.; Avnir, D.; Fairbridge, C.W.; Everett, D.H.; Haynes, J.M.; Pernicone, N.; Ramsay, J.D.F.; Sing, K.S.W.; Unger, K.K. Recommendations for the characterization of porous solids (Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 1994, 66, 1739–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Ding, J.; Liu, T.; Shi, G.; Li, X.; Dang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, R. Pore Structure and Fractal Characteristics of Different Shale Lithofacies in the Dalong Formation in the Western Area of the Lower Yangtze Platform. Minerals 2020, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Boraei, N.F.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Naghmash, M.A. Nanocrystalline FeNi alloy powder prepared by electrolytic synthesis; characterization and its high efficiency in removing Remazol Red dye from aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2022, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, T.; Zaib, M.; Riaz, T.; Shehzadi, S.; Abbasi, M.A.; Shahid, M. Synthesis of Eco-friendly Cobalt Nanoparticles Using Celosia argentea Plant Extract and Their Efficacy Studies as Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Hemolytic and Catalytical Agent. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 6435–6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriniwas, P. P.; Subhash, T. K. , Antioxidant, antibacterial and cytotoxic potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized using terpenes rich extract of Lantana camara L. leaves. Biochem. Biophys. Rep 2017, 10, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Munir, S.; Zeb, N.; Ullah, A.; Khan, B.; Ali, J.; Bilal, M.; Omer, M.; Alamzeb, M.; Salman, S.M.; et al. Green nanotechnology: a review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles — an ecofriendly approach. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, ume 14, 5087–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, C.T.; Raji, P. Facile synthesis and characterization of Co3O4 nanoparticles for high-performance supercapacitors using Camellia sinensis. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Abad, W.; Roomy, H.; Abd, A. , Rapid synthesis of SeO2 nanoparticles and their activity against clinical isolates (gram positive, gram negative, and fungi). NanoWorld J. 2023, 9, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, E. M.; Rasool, K. H.; Abad, W. K.; Abd, A. N. In Green Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial activity of CuO nanoparticles (NPs) Derived from Hibiscus sabdariffa a plant and CuCl, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2021; IOP Publishing: p 012092.

| Sample | Specific surface area (SBET) | Average pore width |

Total pore volume (Vp) |

| m2 g-1 | nm | cm3 g-1 | |

| Co-25 | 4.9892 | 45.589 | 0.056863 |

| Co-400 | 8.0094 | 40.49 | 0.081076 |

| Co-800 | 0.81478 | 77.912 | 0.01587 |

| ID Sample | Inhibition zone (cm) on agar plate | ||

| Gm (-ve) bacteria Esherichia coli ATCC25922 | Gm (+ve) bacteria Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 |

Aspergillus niger MT103092 |

|

| 25 oC | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| 400 oC | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| 800 oC | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).