Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

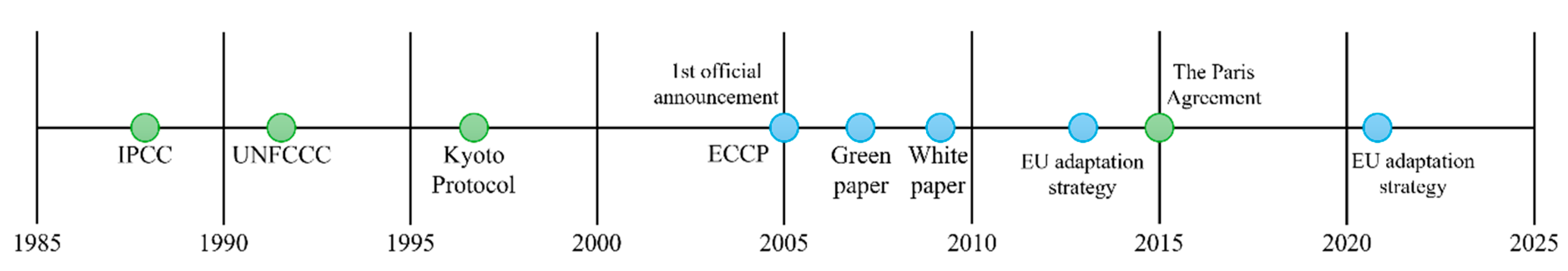

1.1. Background in the European Union

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

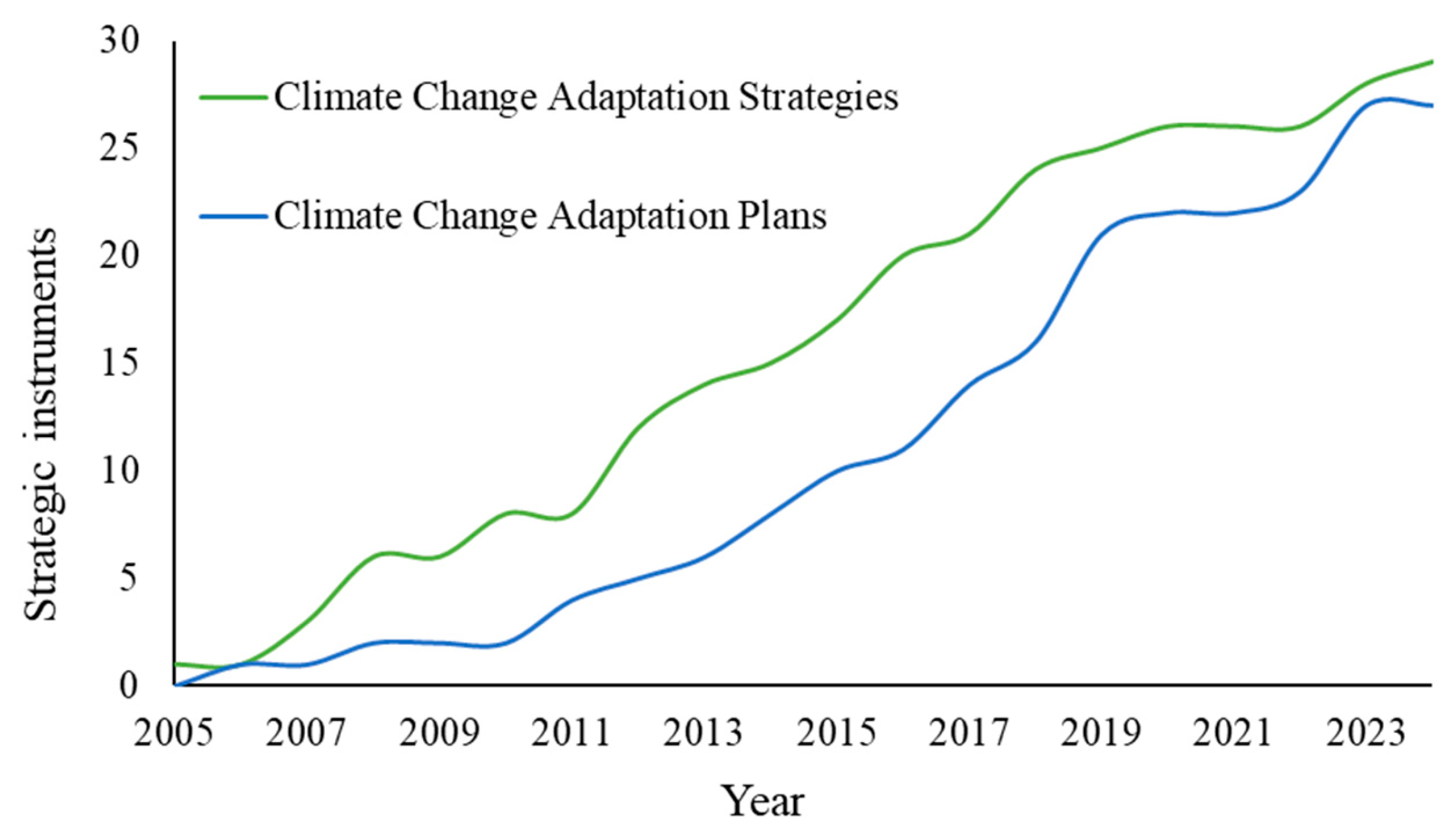

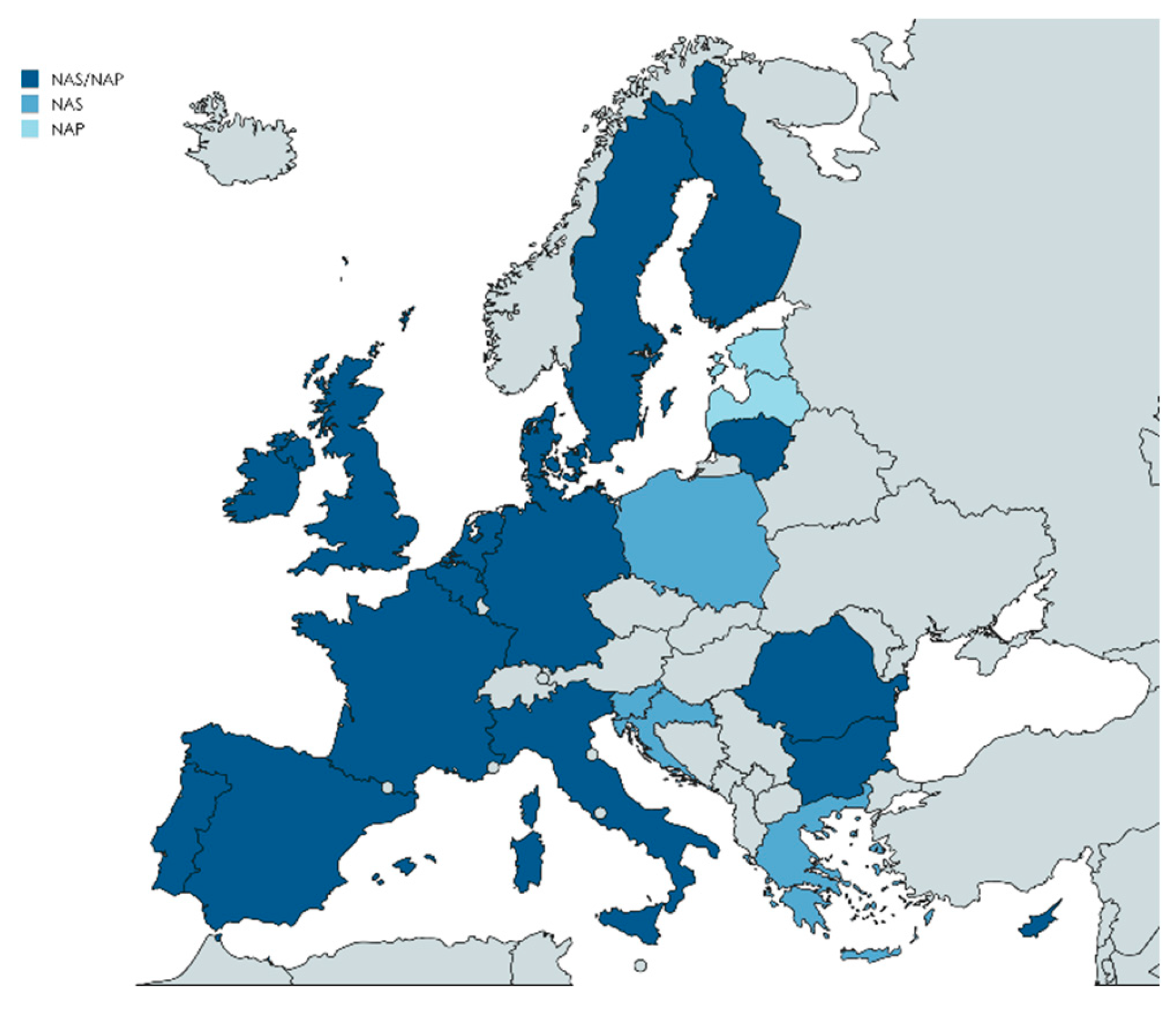

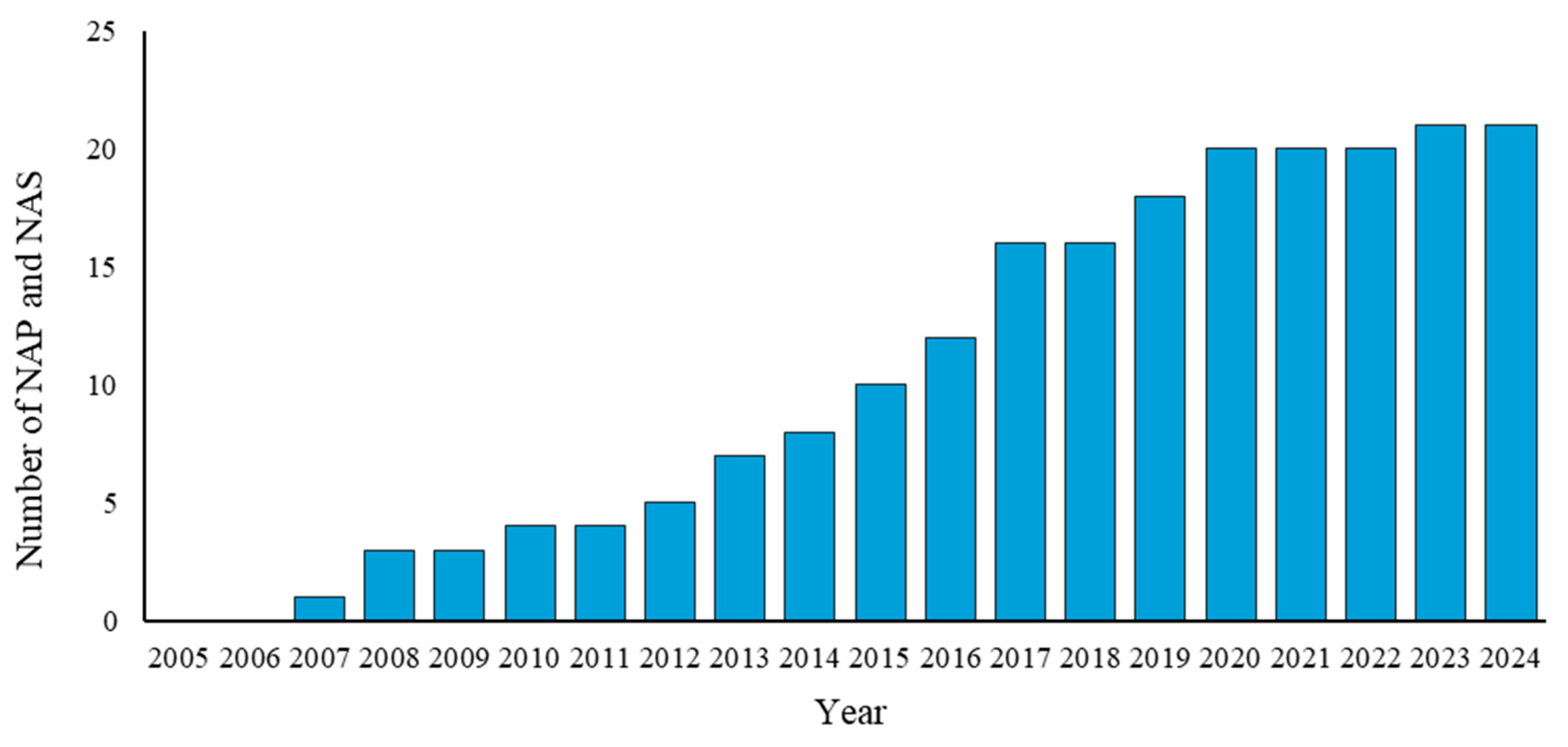

3.1. Analysis of the Climate Change Plans and Strategies of Coastal Countries in the European Union (EU)

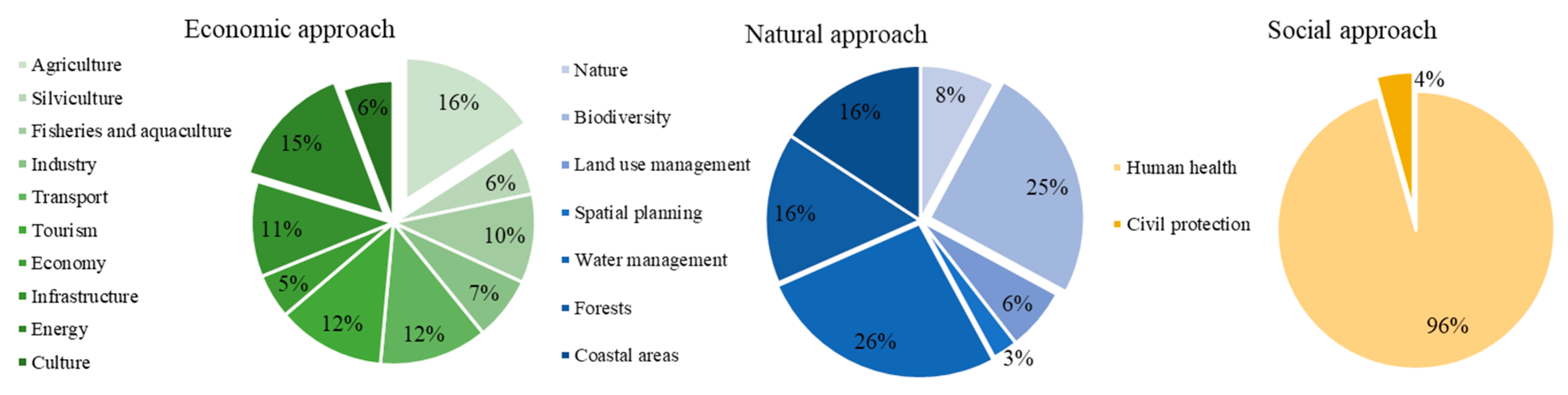

3.2. Adaptation Measures of Strategic Instruments in Coastal Countries of the European Union

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nimma, D., Devi, O.R., Laishram, B., Ramesh, J.V.N., Bouddupalli, S., Ayyasamy, R., Tirth, V., and Arabil, A. Implications of climate change on freshwater ecosystems and their biodiversity. Desalination and Water Treatment 2025, 321, 100889. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023, 184 pp.

- Beca-Carretero, P., Winters, G., Teichberg, M., Procaccini, G., Schneekloth, F., Zambrano, R., Chiquillo, K., and Reuter, H. Climate change and the presence of invasive species will threaten the persistence of the Mediterranean seagrass community. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 910, 168675. [CrossRef]

- Kroeker, K.I., Bell, L.E., Donham, E.M., Hoshijima, U., Lummis, S., Toy, J.A., and Willis-Norton, E. Ecological change in dynamic environments: Accounting for temporal environmental variability in studies of ocean change biology. Global Change Biology 2020, 26, 54–67. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Coastal Cities and Climate Change. OECD Publishing, Paris, France, 2010, 275 pp. https://www.oecd.org/env/cities-and-climate-change-9789264091375-en.htm.

- WEF (World Economic Forum). The Global Risks Report 2019, 14th Edition. World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland, 2019, pp. 114.

- Barragán, J.M. and de Andrés, M. Analysis and trends of the world’s coastal cities and agglomerations. Ocean & Coastal Management 2015, 114, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022, 3-33.

- Pietrapertosa, F., Khokhlov, V., Salvia, M. and Cosmi, C. Climate change adaptation policies and plans: A survey in 11 South East European countries. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 3041. [CrossRef]

- Presicce, L. Buscando instrumentos de coordinación para la gobernanza climática multinivel en España. Actualidad Jurídica Ambiental 2020, 101, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, R., Swart, R. J., Carter, T. R., Cowan, C., Henrichs, T., Mela, H., Morecroft, M.D. and Rey, D. Europe adapts to climate change: Comparing National Adaptation Strategies. Global Environmental Change. [CrossRef]

- Baills, A., Garcin, M. and Bulteau, T. Assessment of selected climate change adaptation measures for coastal areas. Ocean & Coastal Management 2020, 185, 105059. [CrossRef]

- Dovie, D.B.K. Case for equity between Paris climate agreement’s co-benefits and adaptation. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 656, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D., Salvia, M., Heidrich, O., Church, J. M., Pietrapertosa, F., De Gregorio-Hurtado, S., D’Alonzo, V., Foley, A., Simoes, S. G., Lorencová, E. K., Orru, H., Orru, K., Wejs, A., Flacke, J., Olazabal, M., Geneletti, D., Feliu, E., Vasilie, S., Nador, C., Krook-Riekkola, A., Matosović, M., Fokaides, P. A., Ioannou, B. I., Flamos, A., Spyridaki, N.A., Balzan, M.V., Fülöp, O., Paspaldzhiev, I., Grafakos, S., and Dawson, R. How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 191, 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Enríquez-de-Salamanca, A., Díaz-Sierra, R, Martín-Aranda, R. M. and Santos, M. J. Environmental impacts of climate change adaptation. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2017, 64, 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. Co-benefits and synergies between urban climate change mitigation and adaptation measures: A literature review. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 750, 141642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA (European Environment Agency). Adaptación en Europa. Abordar los riesgos y oportunidades del cambio climático en el contexto de los desarrollos socioeconómicos (No. 3/2013). EEA, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013, pp. 136.

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2014, 833-868.

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5 °C, An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2018, 32 pp.

- Toimil, A., Losada, I.J., Nicholls, R.J., Dalrymple, R.A. and Stive, M.J.F. Addressing the challenges of climate change risks and adaptation in coastal areas: A review. Coastal Engineering 2020, 156, 103611. [CrossRef]

- Ferro-Azcona, H., Espinoza-Tenorio, A, Calderón-Contreras, R., Ramenzoni, V.C., Gómez-País, M. M. and Mesa-Jurado, M.A. Adaptive capacity and social-ecological resilience of coastal areas: A systematic review. Ocean & Coastal Management 2019, 173, 36–51. [CrossRef]

- Sheaves, M., Sporne, I., Dichmont, C.M., Bustamante, R., Dale, P., Deng, R., Dutra, L., van Putten, I., Savina-Rollan, M. and Swinbourne, A. Principles for operationalizing climate change adaptation strategies to support the resilience of estuarine and coastal ecosystems: An Australian perspective. Marine Policy 2016, 68, 229–240. [CrossRef]

- Sinay, L. and Carter, R. W. Climate Change Adaptation Options for Coastal Communities and Local Governments. Climate 2020, 8(1), pp. 7-15. [CrossRef]

- Vousdoukas, M.I., Mentaschi, L., Voukouvalas, E., Verlaanand, M. and Feyen, L. Extreme sea levels on the rise along Europe’s coasts. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 304–323. [CrossRef]

- Olcina., J. Adaptación a los riesgos climáticos en España: algunas experiencias. Nimbus 2012, 29-30, 461–474.

- Antunes do Carmo, J.S. The changing paradigm of coastal management: The Portuguese case. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 695, 133807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidrich, O., Reckien, D., Olazabal, M., Foley, A., Salvia, M., de Gregorio Hurtado, S. Orru, H., Flacke, J., Geneletti, D., Pietrapertosa, F., Hamann, J.J.-P., Tiwary, A., Feliu, E. and Dawson, R.J. National climate policies across Europe and their impacts on cities strategies. Journal of Environmental Management 2016, 168, 36–45. [CrossRef]

- European Court of Auditors Climate adaptation in the EU. Action not keeping up with ambition. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2024, pp. 63. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/ECAPublications/SR-2024-15/SR-2024-15_EN.pdf.

- Rayner, T. and Jordan, A. Adapting to a changing climate: an emerging European Union policy? Climate Change Policy in the European Union, Open University Press, Oxford, UK, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, R. and Delaney, A. Mapping the evidence of climate change adaptation policy instruments in Europe. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15(8), 083005. [CrossRef]

- EC (European Commission). Libro Verde de la Comisión al Consejo, al Parlamento Europeo, al Comité Económico y Social Europeo y al Comité de las Regiones. Adaptación al cambio climático en Europa: Opciones para la acción de la UE. Reporte técnico. European Commission, Bruselas, Bélgica, 2007.

- EC. Libro Blanco sobre la Adaptación al Cambio Climático: Hacia un Marco de Acción Europeo. 147 Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas, Bruselas, Belgica, 2009.

- EC. Una estrategia de la UE sobre adaptación al cambio climático SWD. 132 Comisión Europea, Bruselas, Bélgica, 2013.

- Massey, E., Biesbroek, R., Huitema, D. and Jordan, A. Climate policy innovation: The adoption and diffusion of adaptation policies across Europe. Global Environmental Change 2014, 29, 434–443. [CrossRef]

- Berrang-Ford, L., Biesbroek, R., Ford, J.D., Lesnikowki, A., Tanabe., A., Wang, F.M., Chen, C., Hsu, A., Hellmann, J.J., Pringle, P., Grecequet, M., Amado, J.C., Hug, A., Lwasa, S. and Heymann, S.J. Tracking global climate change adaptation among governments. Nature Climate Change 2019, 9, 440–449. [CrossRef]

- EEA (European Environment Agency). Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2016 An indicator-based report (No. 1/2017). EEA, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017, pp. 424.

- Lawlor, P. and Cooper, J.A.G. Analysis of contemporary climate adaptation policies in Ireland and their application to the coastal zone. Ocean & Coastal Management 2024, 259, 107404. [CrossRef]

- Vousdoukas, M.I., Mentaschi, L., Voukouvalas, E., Bianchi, A., Dottori, F. and Feyen, L. Climatic and socioeconomic controls of future coastal flood risk in Europe. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 776–780. [CrossRef]

- Amores, A., Marcos, M., Carrió, D. and Gómez-Pujol, L. Coastal Impacts of Storm Gloria (January 2020) over the Northwestern Mediterranean. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2020, 20(7), 1955–1968. [CrossRef]

- Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Borrasca Gloria. AEMET. Gobierno de España. Available on line: https://www.aemet.es/es/conocermas/borrascas/2019-2020/estudios_e_impactos/gloria (accessed on 11/11/2024).

- Losada, I. J., Toimil, A., Muñoz, A., Garcia-Fletcher, A.P. and Diaz-Simal, P. A planning strategy for the adaptation of coastal areas to climate change: The Spanish case. Ocean & Coastal Management 2019, 182, 104983. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, F. Intervenções de defesa costeira – balanço e perspetivas futuras. Territorium 2020, 27(I), 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltic Sea Region Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (BALTADAPT) Available online: https://www.ecologic.eu/4180 (accessed on 11/03/2025).

- Department of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment of Cyprus. Development of a national strategy for adaptation to the negative impacts of climate change in Cyprus. National Adaptation Plan of Cyprus to Climate Change. Republic of Cyprus, 2017, 281 pp. Available on line: https://www.oeb.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/EN_National-Adaptation-Strategy-CY.pdf.

- Ministry of Environment and Energy of Republic of Croatia. Draft Climate Change Adaptation Strategy in the Republic of Croatia for the period to 2040 with a view to 2070. Republic of Croatia, Zagreb, Croacia, 2017, 101 pp. Available on line: https://mingo.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/KLIMA/Climate%20change%20adaptation%20strategy.pdf.

- Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge of Spain. National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2021-2030). Gobierno de España, Madrid, España, 2020, 164 pp. Available on line: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/cambio-climatico/temas/impactos-vulnerabilidad-y-adaptacion/pnacc-2021-2030-en_tcm30-530300.pdf.

- Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Estonia. Climate Change Adaptation Development Plan until 2030. Republic of Estonia, Tallin, Estonia, 2017, 54 pp. Available on line: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/est178660.pdf.

- Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition of France. National Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2018-2022 (PNACC-2). Republic of France, Paris, France, 2017, 24 pp. Available on line: https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/documents/2018.12.20_PNACC2.pdf.

- Ministry of the Environment and Energy of Greece. National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy. Hellenic Republic, Athens, 2016, 115 pp. Available on line: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/gre190684.pdf.

- Department of the Environment of Government of Ireland. Climate Action Plan 2023 (CAP23). Government of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, 2023, 284 pp. Available on line: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/7bd8c-climate-action-plan-2023/.

- Ministry of the Environment and Protection of Land and Sea of Italy. National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy. Republic of Italy, Roma, Italy, 2015, 195 pp. Available on line: https://www.mase.gov.it/sites/default/files/archivio/allegati/clima/documento_SNAC.pdf.

- Ministry of Environment and Energy Security of Italy. National Climate Change Adaptation Plan. Republic of Italy, Roma, Italy, 2023, 113 pp. Available on line: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/ita218832.pdf.

- Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development. Latvian National Plan for Adaptation to Climate Change until 2030. Latvia, Riga, 2019, 83 pp. Available on https://www.varam.gov.lv/en/media/32915/download?attachment.

- Ministry of Environment. National Energy and Climate Action Plan of The Republic of Lithuania for 2021-2030. Republic of Lithuania, Vilnius, 2019, 273 pp. Available on line: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-08/lt_final_necp_main_en.pdf.

- Resolution of the Council of Ministers. Climate Change Adaptation Programme of Action. Republic of Portugal, Lisbon, 2019, 36 pp.

- Ministry of Environment, Water and Forests. National Action Plan for the implementation of the National Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change for the period 2023-2030 (NSCAP). Republica Populară Română, Bucarest, 2023, 144 pp.

- Van Koningsveld M. and Mulder J.P.M. Sustainable Coastal Policy Developments in The Netherlands. A Systematic Approach Revealed. Journal of Coastal Research 2004, 20(2), 375–385. [CrossRef]

- Bongarts Lebbe, T., Rey-Valette, H., Chaumillon, É., Camus, G., Almar, R., Cazenave, A., Claudet, J., Rocle, N., Meur-Férec, C., Viard, F., Mercier, D., Dupuy, C., Ménard, F., Rossel, B.A., Mullineaux, L., Sicre, M-A., Zivian, A., Gaill, F. and Euzen, A. Designing Coastal Adaptation Strategies to Tackle Sea Level Rise. Frontiers in Marine Science 2021, 8, 740602. [CrossRef]

- Pagán, J.I., López, I., Aragonés, L., and Tenza-Abril, A. J. Experiences with beach nourishments on the coast of Alicante, Spain. In Eighth International Symposium “Monitoring of Mediterranean Coastal Areas. Problems and Measurement Techniques”, Firenze University Press, Florence, Italy, 2020, pp. 441-450.

- Karaliūnas, V., Jarmalavičius, D., Pupienis, D., Janušaitė, R., Žilinskas, G., and Karlonienë, D. Shore nourishment impact on coastal landscape transformation: An example of the Lithuanian Baltic Sea coast. Journal of Coastal Research 2020, 95(SI), 840-844. [CrossRef]

- Myatt-Bell, L.B., Scrimshaw, M.D., Lester, J.N., Potts, J.S. Public perception of managed realignment: Brancaster West Marsh, North Norfolk, UK. Marine Policy 2002, 26(1), 45-57. [CrossRef]

- CASCADE: CoAStal and marine waters integrated monitoring systems for ecosystems protection and managemEnt. Italy-Croatia Cross-Border Cooperation Programme. Available online: https://programming14-20.italy-croatia.eu/web/cascade (accessed on 11/03/2025).

- JPI Climate. 2025. CE2COAST. – JPI Climate. Available on line: https://jpi-climate.eu/project/ce2coast/ (accessed on 10/03/2025).

- USAID (United State Agency for International Development). Adapting to coastal climate change: a guidebook for development planners. U.S. Agency for International Development, NY, 2009, 148 pp.

- Geneletti, D. and Zardo, L. Ecosystem-based adaptation in cities: An analysis of European urban climate adaptation plans. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 38–47. [CrossRef]

- FutureMARES. Available online: https://www.futuremares.eu (accessed on 11/03/2025).

- Segura L., M. Thibault & B. Poulin. Nature based Solutions: Lessons learned from the restoration of the former saltworks in southern France. Tour du Valat, France, 2018, pp. 39.

- Davranche, A., Arzel, C., Pouzet, P., Carrasco, A, R., Lefebvre, Thibault, M., Newton, A, Fleurant, C., Maanan, M., Poulin, B. A multi-sensor approach to monitor the ongoing restoration of edaphic conditions for salt marsh species facing sea level rise: An adaptive management case study in Camargue, France. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 908, 168289. [CrossRef]

- Cox, T., Maris, T., De Vleeschauwer, P., De Mulder, T., Soetaert, K., Meire, P. Flood control areas as an opportunity to restore estuarine hábitat. Ecological Engineering 2006, 28(1), 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Ministerie van Infraestructuur en Waterstaat. Houtrib Dike Sandy Foreshore Pilot Project. Public summary. Ecoshape, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018, pp. 6.

- Perk, L., Van Rijn, L., Koudstaal, K., Fordeyn, J. A Rational Method for the Design of Sand Dike/Dune Systems at Sheltered Sites; Wadden Sea Coast of Texel, The Netherlands. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7(9), 324. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Linham, M. M., and Nicholls, R. J. Technologies for Climate Change Adaptation - Coastal Erosion and Flooding. Danmarks Tekniske Universitet, Risø Nationallaboratoriet for Bæredygtig Energi. TNA Guidebook Series, 2010, 167 pp.

- Proyecto CLIMPORT: Sistema de modelado del diseño y construcción de infraestructuras portuarias adaptadas al cambio climático. FCC. Available online: at https://www.fccco.com/-/proyecto-climport (accessed on 10/03/2025).

- BeachTech: Coastal erosion due to climate change: assessment and ways to address it effectively in the tourist areas of the North Aegean and Cyprus. Available online: https://beachtech.eu/ (accessed on 10/03/2025).

- UK Climate Projections (UKCP). Met Office. Available on line: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/approach/collaboration/ukcp/index (accessed on 10/03/2025).

- Rousell, D. and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A. A systematic review of climate change education: Giving children and young people a ‘voice’and a ‘hand’in redressing climate change. Children’s Geographies 2019, 18(2), 191-208. [CrossRef]

- Foundation Euro-Mediterranean Centre on Climate Change. ChangeGame. Available online: https://www.changegame.org/ (accessed on 10/03/2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente. Estrategia de Adaptación al Cambio Climático de la Costa Española. Dirección General de Sostenibilidad de la Costa y del Mar, Madrid, España, 2016, 120 pp. Available on line: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/costas/temas/proteccion-costa/estrategiaadaptacionccaprobada_tcm30-420088.pdf.

- CONAMA. Informe de análisis de las investigaciones científico-técnicas y proyectos en materia de adaptación al cambio climático en costas. Fundación CONAMA, Madrid, España, 2024, pp. 23. Available online: https://www.conama.org/2024/actividades/adaptacion-de-la-costa-al-cambio-climatico/.

- MaCoBioS Project. Available on line: https://macobios.eu/ (accessed on 27/11/2024).

- CoEvolve project. Available on line: https://www.coevolve.eu/ (accessed on 11/12/2024).

- González Domingo, A. and Tonazzini, D. Guía de adaptación de destinos de costa e insulares al cambio climático: Calvià (Mallorca). Ed. eco-union. Barcelona, España, 2019, 42 pp. Available on line: https://www.adaptecca.es/sites/default/files/documentos/guia_adaptur_costa_visual.pdf.

- Araos, M., Berrang-Ford, L., Ford, J. D., Austin, S. E., Biesbroek, R. and Lesnikowski, A. Climate change adaptation planning in large cities: A systematic global assessment. Environmental Science & Policy 2016, 66, 375–382. [CrossRef]

| Category | Type | Title 3 Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Structural/physical | Engineered & built environment |

Coastal protection and flood control structures; improve drainage; flood and cyclone shelters... |

| Technological | New crop varieties; knowledge; hazard and vulnerability monitoring and schemes; early warning systems... | |

| Ecosystem- based | Ecological restoration; Soil conservation; control of overfishing; ecological corridors... | |

| Services | Social safety nets and social protection; essential public health services... | |

| Institutional | Economic | Financial incentives; insurance; payment for ecosystem services; contingency funds in case of disasters... |

| Laws and regulations | Urban planning legislation; building standards and practices; disaster risk reduction legislation; protected areas... | |

| National and government policies and programs | Adaptation plans; urban upgrading programs; disaster planning and preparedness; integrated coastal zone management... | |

| Social | Educational | Awareness raising and mainstreaming in education; participatory action research and social learning; knowledge sharing; knowledge sharing and learning platforms... |

| Informational | Development of hazard and vulnerability schemes; early warning and response systems; surveillance and remote sensing; climate services... | |

| Behavioral | Household preparation and evacuation planning; migration; soil and water conservation... |

| Type | Subtype | Adaptation measure | Instrument/Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural/ Physical |

Engineering | Constructing or reinforcing seawalls, jetties, artificial reefs, fixed/mobile barriers or coastal protection infrastructure | 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13 |

| Beach regeneration and dredging of channels and creation of artificial beaches and dune systems | |||

| Construction of structures to resist saline intrusion | |||

| Developing protection or buffer zones on the seafront | |||

| Adoption of protection systems by increasing the height of sea walls and other infrastructures | |||

| Technology | Develop more effective warning and monitoring systems and tools | 1, 8 | |

| Develop models of coastal morphodynamic and hydrodynamic response | |||

| Ecosystemic | Discharge and contribute solids to rivers | 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13 | |

| Protect, conserve, and renaturalize valuable coastal ecosystems | |||

| Safeguard key species and coastal biodiversity. | |||

| Intervention and management of cliffs | |||

| Natural restoration of sediment transit in river basins | |||

| Service | Modify buildings in low-lying areas to make them more resistant to the weather and the action of the sea | 1, 7 | |

| Adequacy of harbor facilities and jetties data | |||

| Social | Information | Monitoring and tracking of climate variables and coastal conditions | 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13 |

| Assessment of infrastructure and coastal protection measures | |||

| Development of studies, projects, and research on the effects of climate change | |||

| Study on the identification of individuals who are vulnerable to climate change in coastal areas | |||

| Educational | Develop knowledge of the coast and its relationship with climate change at different educational and social levels | 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 13 | |

| Capacity-building and awareness-raising at both human and institutional levels | |||

| Behavioral | Salt-tolerant crops | 5, 6, 8 | |

| Strategic retreat or relocation of coastal urban developments, activities, and anthropogenic uses | |||

| Discouraging coastal urban development | |||

| Institutional | Economic | Increase and promote financial resources for climate change adaptation | 5, 8 |

| Develop coverage strategies (insurance against economic disruptions in ecosystem service provision) | |||

| Develop risk insurance for ecosystem benefit losses and economic losses | |||

| Adopt economic and financial instruments | |||

| Law and regulations | Implement and/or improve climate change or coastal zone laws and regulations | 1, 3, 7, 8, 13 | |

| Enforce compliance and regulatory codes | |||

| Policy and programs | Adopt and/or improve coastal management strategies, plans, and programs at national and local scales | 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 | |

| Integrate coastal conservation, use, and management plans |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).