1. Introduction: Coastal Restoration Deficit, Barriers and Enablers

Coastlines and the communities that live behind them are becoming increasingly vulnerable under future climate scenarios. Rising ocean water temperatures and acidification, compounded by sea level rise (SLR) are exacerbating the frequency and intensity of storm-induced damages [

55,

63] while decreasing the protection offered by coastal ecosystems [

4,

25,

57,

69]. Such decrease is linked to an adaptation deficit that will be hard to bridge unless suitable technical, economic and management advances (in short restoration enablers) are applied to overcome current barriers to restoration and its upscaling [

58].

In response to climate change in general and SLR in particular, many ecosystems provide resilient bio-physical responses that allow them to evolve at a rate similar to climatic pressures, illustrated by wetland response under increasing SLR, temperature and decreasing pH [

44,

73]. Salt marsh accretion and lateral expansion are driven by seasonal cycles of plant growth [

67]. In sandy beach environments, longshore transport facilitates the movement of riverine solid discharges into nearshore processes [

25,

26]. Accelerating climatic and anthropogenic pressures are progressively limiting these bio-physical processes and act as barriers that hinder natural coastal resilience. This resilience is further threatened by pollution, land reclamation, draining, and damming [

50,

74].

These and other typical human activities on coastal zones, linked to altered water, sediment, and nutrient fluxes, deliver socioeconomic benefits, but lead to artificial coasts that have lost, at least in part, their natural resilience to SLR and wave storms. This amplifies risks due to erosion, flooding and salinization, leading to vulnerable coasts that present high climate risk levels for present and future coastal communities. By way of illustration more than 70% of beaches now face a negative sediment budget [

47] leading to erosion, which is thus becoming a global problem. The combination of climate change and anthropogenic stresses have worsened coastal hazards, and 4.6% of the global population is expected to experience annual coastal flooding by 2100 [

47].

This has created a need to protect coastal populations from erosion, flooding and other climatic risks under present and future conditions, which will grow to unacceptable levels unless suitable enablers are applied to fill the coastal restoration deficit at a rate commensurate with climate change acceleration. This challenge defines the core of the paper, which investigates how coastal risks can be curbed in the mid- to long-term through the implementation of coastal restoration agreements that combine the required technical, economic, social and governance enablers. These contracts aim to fill the present implementation gap by answering the following research question: How may restoration barriers and enablers be embedded in co-designed agreements to enhance restoration success? Drawing on literature, existing restoration contracts in forest and river ecosystems, together with incipient work for coastal systems, will provide the basis to develop upscaled coastal restoration agreements, with supporting evidence from the pilot restorations carried out within the REST-COAST research project, developed as part of the European Green Deal.

2. Costal Restoration Framing: Questions and Answers

2.1. Why Restore Coastal Ecosystems?

Coastal hazards have been traditionally addressed through grey infrastructure, designed and built within a top-down designed plan, as a reaction to short term needs [

3]. The mainstreaming of grey infrastructure is linked to its short-term efficiency in mitigating hazardous events, but future climate change scenarios predict events surpassing the static safety factors for which such grey infrastructure is built [

10,

25,

47]. Updating and repairing this infrastructure to meet future requirements presents significant costs and uncertain performance under prospective scenarios, often leading to the degradation of coastal ecosystems, weakening their ability to mitigate storm impacts [

26,

66]. This is exemplified in seawalls which provide short-term protection against waves and surges but lead to enhanced mid-term erosion when reflected waves increase longshore transport and produce wall toe scouring [

36]. This has led to a shift in present coastal protection practice, favoring green or hybrid infrastructure as a more adaptive means of reducing coastal risks from increasing human and climatic stresses [

64]. In addition, such green protection presents a lower carbon footprint for implementation and contributes to coastal blue carbon for climate mitigation.

Restored coastal ecosystems means they can become dynamic ecotones to offer supporting, regulating, provisioning, and cultural services. Restoration can align coastal protection with climate mitigation, illustrated by wetlands or seagrass meadows that provide efficient carbon sinks, a regulating service. For coastal adaptation to climate hazards, restored ecosystems can regulate shocks and stresses [

13], where natural coastal dynamics provide a wide range of regulating services to curb natural hazards [

10,

47]. For example, beach profile adaptation, involving wetland and dune migration, enhances surge and wave attenuation and reduces land loss to sea level rise. Subtidal habitats can cause localized shoaling, forcing wave breaking and reducing storm-induced erosion and flooding. Coastal vegetation and reefs enable sedimentation processes that result in accretion and higher adaption potential under sea level rise [

63]. Coastal ecosystems thus provide both abiotic and biotic services that reduce coastal hazards with a low carbon footprint and must be restored at a rate and scale commensurate with climate change.

2.2. How to Restore Coastal Ecosystems

The combination of anthropogenic pressures and changes to shorelines through traditional engineering have left coastal ecosystems degraded and unable to adequately provide their ecosystem services. However, ecosystems and their ability to deliver beneficial services [

5,

72] can be repaired through ecological restoration (ER), which is the “process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed” [

22] (p. S7). Effective ER should not only focus on the renewal of ecosystem services, but on the long-term increase of ecological integrity as well as on the benefits to society [

32].

To decide on how to restore ecosystem services and societal benefits, an end-point must be defined to determine “restoration success.” Although it has been argued that it is hard to co-define a standard of success [

32], best practices have been put forward [

7,

22]. The Society for Ecological Restoration suggests setting a target based on biophysical parameters and stakeholder goals [

22,

32,

53]. This means that ER success will change depending on location, climate, and stakeholders involved.

Ecological engineering is a subset of ER that aims to use combined adaptation strategies to efficiently meet the ecological and societal principles of ER through engineering practice [

10]. In coastal ecosystems, ER can be accomplished across a range of interventions, where natural regeneration is the most passive form of restoration and assisted or active regeneration is the more active [

32]. Ecological engineering embodies this scale from hard to soft interventions that incorporate conservation principles in the design and implementation of solutions [

47], which are often termed nature-based solutions (NbS), building with nature, or living shorelines [

38].

Restoration success metrics in coastal environments have traditionally been defined by the measures associated with hard, grey solutions such as seawalls or groynes. Ecological engineering defines success metrics based on the dynamic goals of restoration projects, which often form a matrix of increasing protection, ecological integrity, and social benefit [

47]. These restoration goals are ideally defined by a platform of collaborating stakeholders including coastal managers, scientists, engineers, and members of the local communities.

2.3 Which Barriers to Overcome for Restoration Success

Ecological conservation and restoration, not identical [

32], have increasingly become a global policy topic as demonstrated by the United Nations’ adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GDF) in 2022 [

37]. Under this framework, member states have pledged to conserve 30% of land, freshwater, and sea areas by 2030. In the European Union (EU), ecological conservation and restoration first appeared in policy with the 1979 Birds Directive, and this was followed by the 1992 Habitat Directive [

17]. These directives aimed to protect selected bird, flora, and fauna species by developing Special Protected Areas (SPA) and Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), respectively. The SACs formed an ecological network of over 27800 sites, named the Natura 2000. As of 2020, more than half of the areas and species covered by the bird and habitat directives faced unfavorable conditions. In response to the lack of success with the directives and the GDF, the European Commission developed the Biodiversity Strategy 2030 under the European Green Deal [

17,

37]. The strategy expands on the Natura 2000 network and aims to protect at least 30% of land and sea target areas by 2030. To make the strategy enforceable, the European Commission recently legislated the Nature Restoration Law (NRL) which binds European Union members to the targets of the strategy [

29].

While the NRL offers strong legislation at a regional scale to support restoration, restorationists will still face barriers to implementation from the national to the local level. In a review of restoration experts’ experiences with project implementation, “insufficient funding, conflicting interest among stakeholders, and low political priority given to restoration [at the local level]” were identified as major barriers to restoration [

11]. Thirty additional barriers were identified and grouped into six categories: financial, environmental, legal (including landownership), managing planning and implementation, policy and governance, and the socio-cultural context. These categories can be generalized into technical, financial, governance, and social barriers to restoration. The study found that the technical barriers to restoration were overshadowed by the financial, governance, and social barriers, stating that restoration would not be furthered in the EU until they are addressed [

11,

30]. Contrarily, practitioners identified effective restoration as a process that considers biodiversity, ecosystem function and ecosystem services with a goal of reaching a self-sustaining ecosystem for a continued delivery of ecosystem services. Restoration success is based on an initial site assessment for design and deployment, supplemented by a continued monitoring and adaptive management for maintenance and sustainability [

58].

2.4. Where to Implement Restoration Agreements and Platforms

While legislation is one tool through which ER is supported, it is not the only one since conservation and restoration agreements can be applied to overcome barriers and solidify enablers during the project planning, implementation, monitoring, and maintenance. Such agreements are most commonly seen in forestry restoration for carbon sequestration among other purposes, but they are also being formulated in other ecosystems [

2,

9]. The five main types of contracts can be grouped into: a) “Conservation Concession Agreements” which develop lease agreements for land that organizations are then able to restore [

2] (p. 449); b) “Conservation Performance Payments” which are similar to concession agreements, but they create a payment for an ecosystem service as long as habitat protection or restoration outcomes are achieved; c) “Carbon Agreements” which are common in forests and coastal environments, here termed Blue Cabon Agreements; d) “Private Protected Area Agreements” which are parcels of habitat owned by a company or other private entity who are paid to conserve the parcel; e) “Debt-for-Nature Swaps” which are contracts that purchase foreign debt in exchange for restoration efforts or conserved areas. In the field of restoration, long-term contracts are preferable to short-term ones, to ensure that monitoring efforts and adaptive management can be properly enacted [

15].

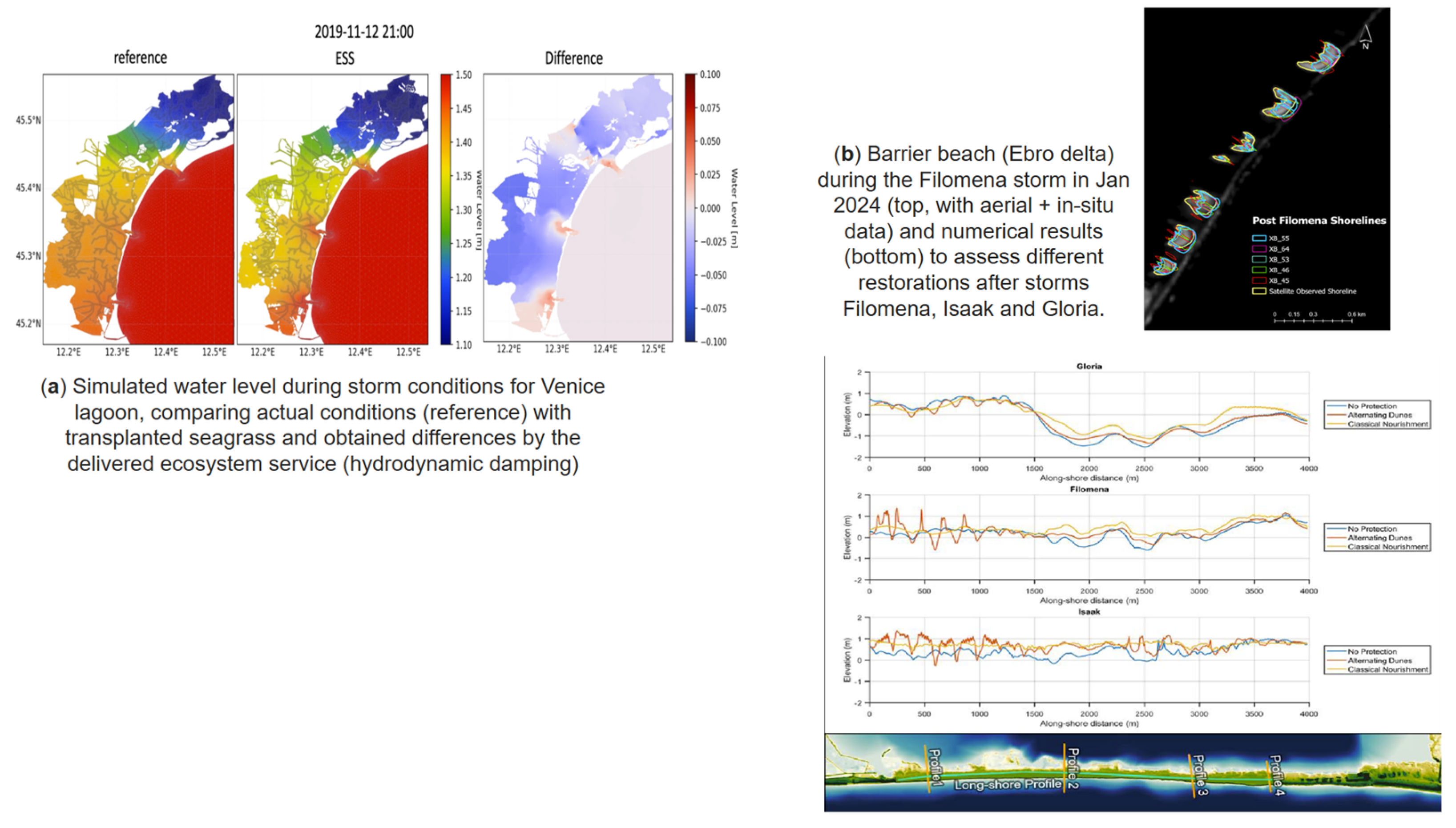

These contracts can be supported by restoration platforms, aggregating all relevant stakeholders to promote consensus and long-term aims. These platforms help overcome barriers and secure enablers by capturing the dynamic nature of the protected ecosystems. They accommodate mechanisms for adjustment, setting parameters for how disputes may be settled [

39], where dispute settlement and consensus building normally benefit from long-term agreements. Restoration platforms can be better bound by such contracts, which foster agreement among stakeholders based on limited uncertainties and explicit shared benefits. Coastal restoration agreements should define the barriers and enablers that must be addressed as a function of time and space to ensure a sustained risk reduction and improved livelihood based on the delivered ecosystem services.

In coastal ecosystems, agreements should be implemented in locations with high social and ecological vulnerability [

56], promoting nature-based solutions for a long-term coastal protection aligned with climate mitigation. Such a decarbonized protection requires a governance system that is mature enough to coordinate policy, legislation, and administrative action to implement large-scale restoration projects [

70]. Although agreements can be used to foster communication and knowledge building, they may best be implemented where there is a baseline, or willingness to collaborate on an effective co-design, implementation, and monitoring. This should lead to upscaled restoration, at a pace and scale commensurate with the projected climate change acceleration [

20,

56,

57].

3. Systemic Restoration: River-Coast Connectivity and Dynamics

The delivery of coastal ecosystem services requires, given the progressive degradation of many coastal habitats worldwide [

14,

45,

48,

51], large scale interventions that restore their functions and structure. This implies reconnecting river basins to downstream coasts and recovering the natural dynamics of nearshore areas, promoting services such as flooding and erosion risk reduction, water quality enhancement, biological productivity [

14,

24] and coastal blue carbon, which is among the most efficient carbon sinks on the planet [

42].

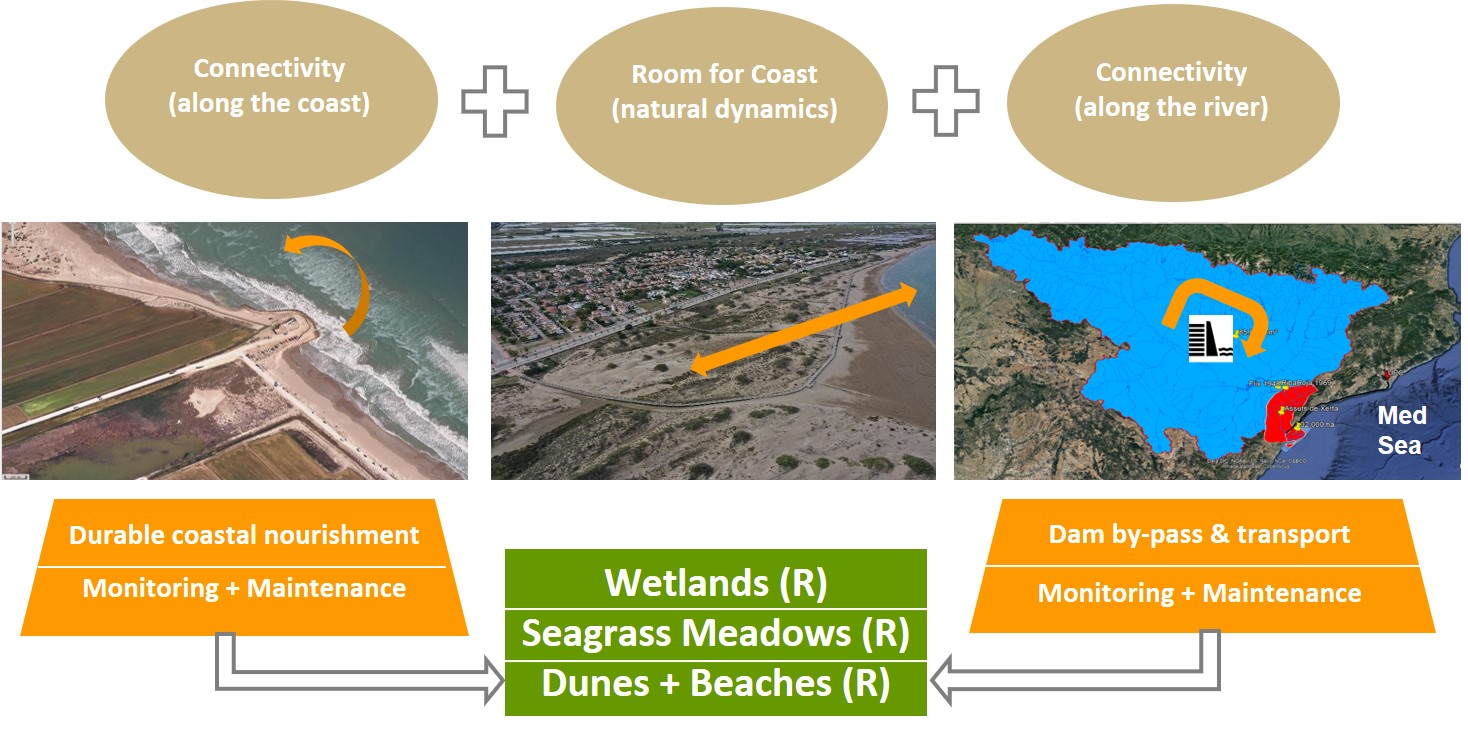

A systemic approach is therefore required, overcoming the current deficit in restoration implementation [

19,

57]. Available restoration evidence, from pilot interventions such as the ones in the REST-COAST project (

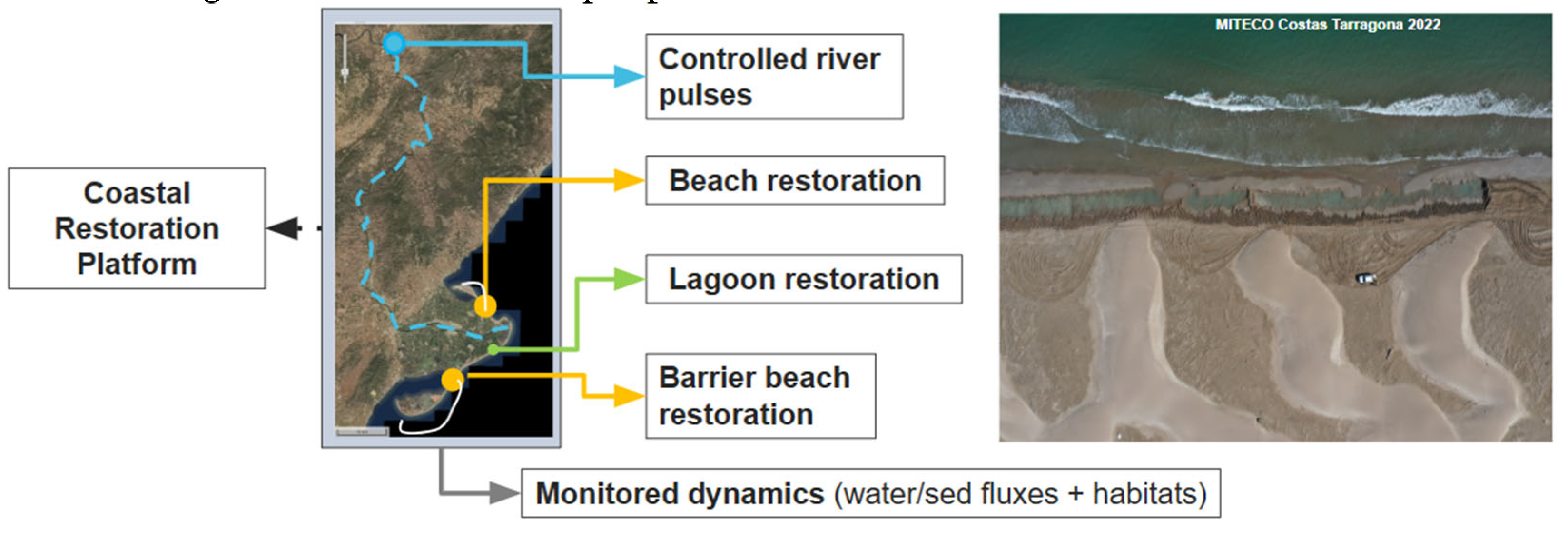

https://rest-coast.eu), demonstrate across a set of social-ecological conditions (

Figure 1) how upscaled restoration can align coastal adaptation with climate mitigation through blue carbon, natural hazard reduction, biodiversity gains, and improved environmental status [

57]. These pilot initiatives pave the way to implement landscape-scale restoration, combining river-coast connectivity with nature-based solutions to recover coastal resilience through natural sediment and nutrient fluxes.

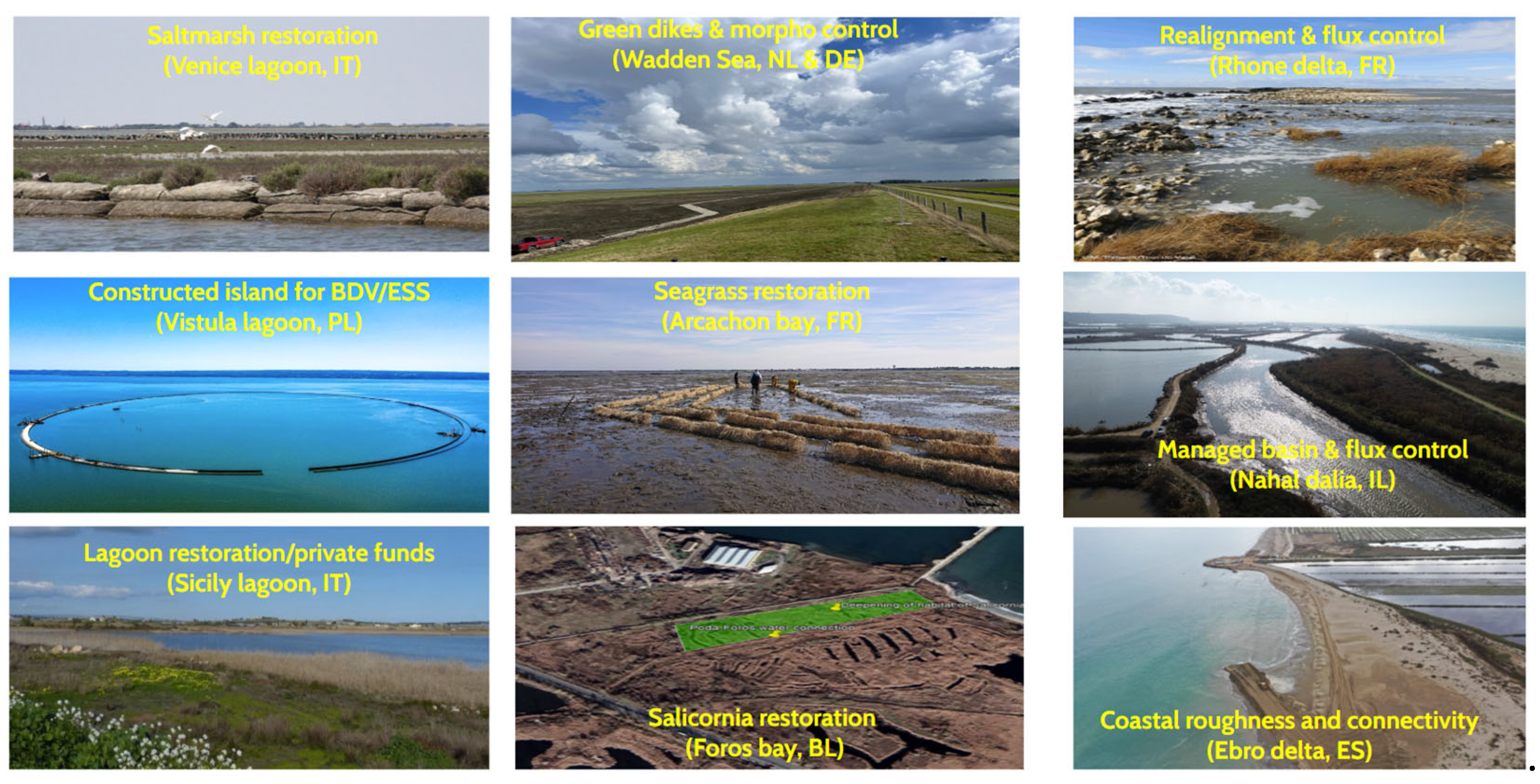

The pursued restoration upscaling is based on overcoming current barriers by suitable “enablers” (

Figure 2), which increases the scale and pace of the implementation, commensurate with the projected acceleration of climate change for the remaining decades in this century [14; 61]. The pilot interventions refer to a variety of coastal vulnerability hotspots, including deltas, estuaries, and lagoons over nine sites that sweep a large enough set of social-ecological conditions to facilitate deriving exportable criteria and metrics. The targeted habitats are dunes (emerged area), wetlands (intertidal area) and seagrass meadows (submerged area), under complex constraints for the integration of governance, social, economic, and technical requirements. The pilot restorations carried out have served to develop a set of enablers, based on best practices for active and passive restoration techniques, supported by business plans and financial arrangements. Such an approach must be associated to a transformative governance, based on an increased engagement by all relevant coastal actors [

43].

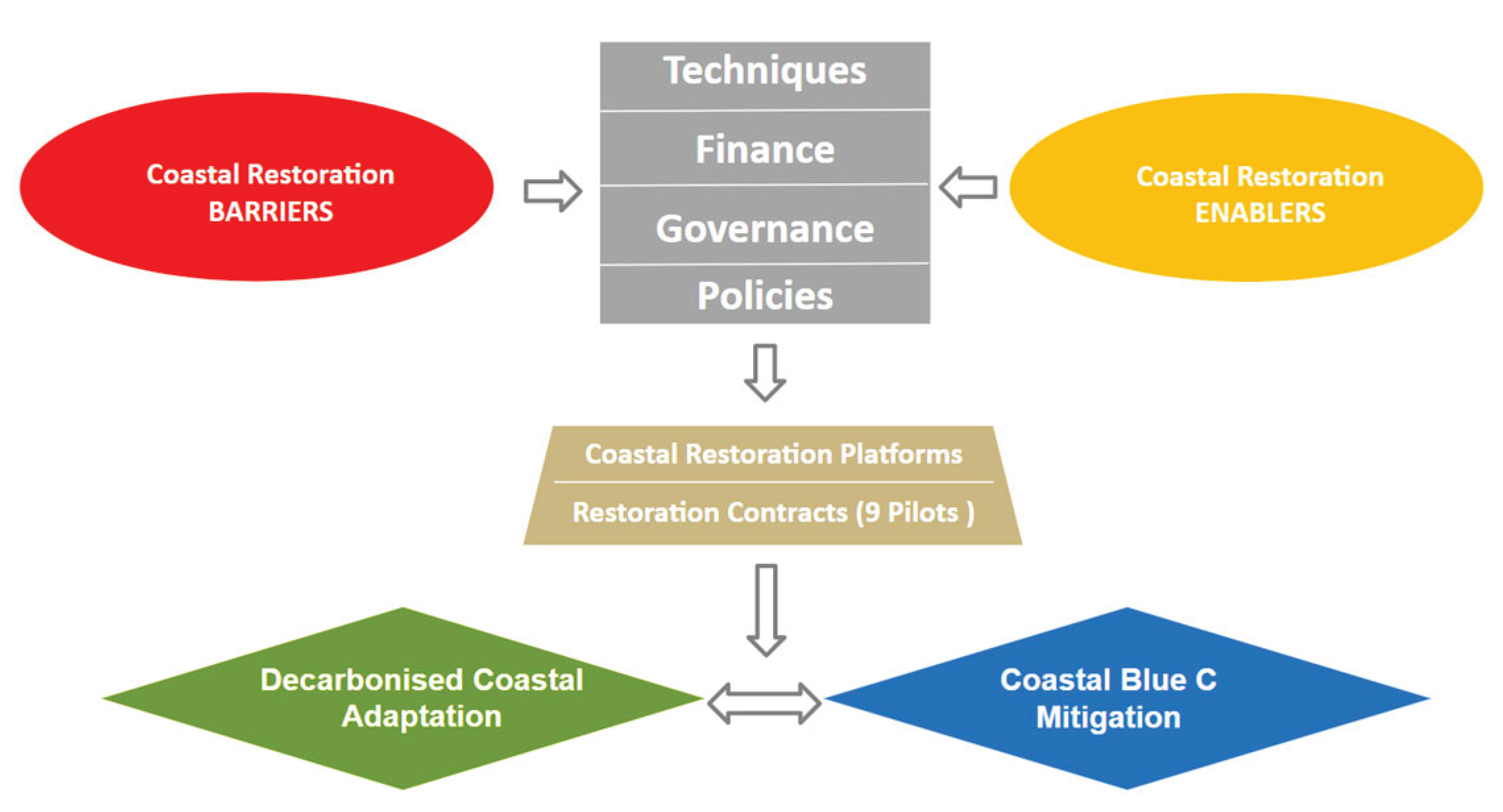

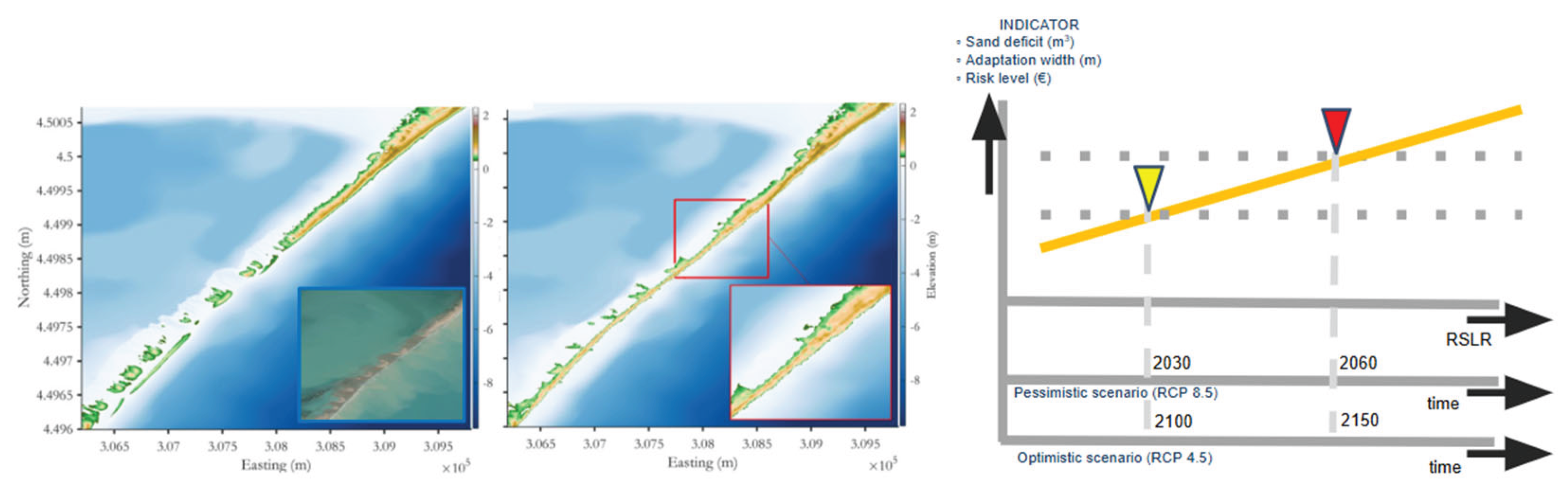

Restoration upscaling can only be deployed and maintained through continued monitoring from which key performance indicators, co-selected by all relevant stakeholders, can be evaluated as a measure of restoration efficiency and limits. Monitoring must be carried out at sufficient resolution to characterize different ecosystem services, but also maintained for long enough periods, commensurate with the time required by some ecosystems to recover or develop (e.g., seagrass transplantation or passive restoration). Observations should be supplemented by numerical simulations that predict the short-term impact of storm events (

Figure 3) and project the long-term evolution (

Figure 4) driven by climate change. Such a combination of observed and simulated data enables an objective ranking of restoration interventions and their sequencing, providing quantitative information on feasibility, initial costs, maintenance expenditure and benefits from the delivery of ecosystem services.

The proposed systemic restoration must be co-designed by stakeholders from the river-coast continuum, combining technical, economic and governance criteria from various disciplines (biophysical and socioeconomic) across sectors (e.g., irrigation in the river catchment basin and tourism in the coastal zone) and scales (e.g., compatible short-term interventions to reduce coastal erosion with long-term plans to enhance resilience for the wider coastal fringe). To achieve the required convergence of criteria across stakeholders and maintenance across river to sea domains and scales, it is convenient to establish restoration agreements, backed by site-specific restoration platforms, tailored to the local governance structure, and complying with applicable legislation. These restoration platforms and contracts, including technical, financial and governance suggestions for a successful restoration, form the core of this paper. They are acting as enablers that increase the implementation pace and scale of restoration projects in the REST-COAST pilots and should be able to play the same role in worldwide coastal restorations.

4. Ecosystem Restoration Agreements In Different Domains: Experiences And Enablers

Technical, financial, governance, and social barriers have been identified as frequent impediments to restoration success and upscaling [

11]. Co-designed agreements, framed by a common stencil, can be used as an enabler to overcome these barriers because they provide a consensus structure to embed restoration into coastal protection interventions and planning, linking the design, implementation, monitoring and maintenance stages.

This section explores case studies of existing restoration contracts in a variety of ecosystems, examining how they embedded enablers to overcome barriers. The outcomes of these case studies are next compared and applied to coastal restoration pilots from the REST-COAST project, presenting how these pilots are implementing similar contracts to circumvent the main barriers for restoration upscaling.

4.1. Privately-Owned Forest Conservation Contracts, Germany

Germany was one of the first countries in “western science” to consider conservation. German foresters first coined the term sustainability as a solution to degrading forest conditions, increasing populations and intensifying industry [

21]. Today, forest conservation in Germany has been legislated [

15], although regulation-enforced conservation has been found to result in a negative financial impact on private foresters, so the German Federal Nature Conservation Act prioritises voluntary conservation contracts over additional regulation.

The German National Strategy on Biodiversity aims to secure “contract-based nature conservation in 10% of privately-owned forest land” [BMU, as cited in 15] (p. 90). This study identifies a catalogue of private forests where conservation contracts would be suitable, highlighting the barrier that the majority of high value conservation projects are often already relatively well protected. This leaves threatened forests economically vulnerable, while the effect of conservation on downstream solid transport, which directly affects coastal sustainability, is not normally considered. The focus on local economic valuation and financial barriers in this study is associated to a profit-oriented governance system that does not consider larger scale implications. Disregarded implications, for instance on the “receiving” coast, as well as broad social and technical implications, are critical to the success of a restoration project.

Of the REST-COAST coastal pilots, Sicily’s Lagoons (Mediterranean Sea) restoration, reflects some of the patterns in Germany’s private forest conservation contracts. Much of this Mediterranean Island’s restoration is funded by the Artenvielfalt Stiftung, a private foundation that funds biodiversity projects. This relationship establishes a financial enabler for the project, where the co-designed restoration includes local organizations like conservation associations, farmers, and tourist operators [

49]. Furthermore, the restoration includes social-ecological interactions, such as mitigating coastal flooding, maintaining biochemical characteristics of the lagoon, and protecting the habitats that support the delivery of ecosystem services. A contract for this type of restoration project should consider the duration of the financial relationship, and it must ensure that relevant aspects related to social, technical, and governance barriers and enablers are included as well.

4.2. Tropical Forest Restoration Through Regenerative Agriculture, Panama

Tropical Forest Restoration has been promoted by the Panamanian Government to meet international commitments, improve water security, and protect biodiversity. In Panama, ranching has turned about 70% of the country’s native forests to pastures [

23]. This prompted a project to attempt a native species forest restoration in the Azuero Peninsula working with farmers. This project accounts for existing tree planting practices that farmers already engaged in, while planted tree species serve purposes such as fruit harvesting, that some of the project’s selected native species did not provide [

23]. The lack of engagement with local landholders led to the project's failure in achieving long-term success.

Large scale transplantation efforts have been known to fail, especially in agricultural areas, due to landowner resistance [

31]. To overcome this barrier, such as for tropical forests, restoration must be bottom-up, using multistakeholder engagement to plan, implement, and evaluate the project benefits. For the Panama case, a new reforestation project in the Azuero Peninsula has begun, working with local landholders and communities to establish agroforestry and silvopastoral model farms to expand regenerative agriculture in the area, while promoting reforestation [

62]. These regenerative agriculture systems increase local yields from small areas, enabling a secondary forest regeneration, associated to continued ranching practices, traditional to the area. Such a reforestation approach has served to identify the needs of ranchers, fostering technological, financial, and societal enabling conditions. While this example still lacks the co-design of forest restoration contracts, it highlights the importance of stakeholder engagement to secure the long-term success of a restoration project.

The importance of stakeholder engagement, particularly if included in restoration contracts, can be illustrated by the REST-COAST pilot case in Arcachon Bay, France. A key pressure degrading sea grass meadows in the bay’s semi-closed coastal lagoon, is oyster farming, an important activity in the local economy [

12]. Even though the restoration initial focus is on repairing the lagoon’s hydrological regime, local stakeholders have been involved in the restoration design, compromising on locations where oyster farming may be maintained. This includes the development of regenerative aquaculture sites in the lagoon, where the regional committee for oyster farming could be included as a signing party in the contract. This would act as an enabler for the long-term success of this restoration, achieving a sustainable compatibility between the future protection of the lagoon’ ecosystem and historical farming practices.

Another illustration of stakeholder engagement for the compatibility between short-term needs and long-term sustainability can be derived from the REST-COAST pilot in the Ebro Delta, Spain. This case also targets the compatibility between ongoing aquaculture practices in the deltaic bays (mussels, oysters, and other bivalves) with coastal morphodynamic evolution and environmental health status. The involvement of stakeholders in the Restoration Platform aims for sufficient water quality in the coastal bays, as required by aquaculture, by means of a smart co-management of these bays that considers the pressure of longshore sediment transport to close the bay, transforming it into a brackish lagoon [

46]. By including bivalve harvesters in the restoration contract, continued collaborative decision making can be used to develop long-term regenerative aquaculture, benefitting the bay’s ecosystem and enabling the short to long term compatibility between aquaculture and the morphodynamic evolution of deltaic bays.

4.3. The White Mountain Stewardship Contract, USA

Restoration contracts in the USA, usually termed “Stewardship Contracts”, aim to connect natural resource management to local communities and develop a landscape approach to restoration [

68]. The White Mountain case highlights the importance of contract development, which can be used to build capacity and enable relationships between the various actors involved in the restoration. This development for this case resulted in a ten-year contract to treat 150,000 acres of federal forests, enacted in 2004 [

1]. To set up the contract, a working group was established ten years before the contract was put in place, bringing together representatives from all relevant sectors to create a collaborative forum. They iterated project changes through each member and worked within the applicable legislation to plan a shared restoration project. The working group also built community capacity for restoration practice, which was integral to developing the stewardship contract [

1]. The working group still exists as a managing body of White Mountain.

An important outcome of the working group was the establishment of a demonstration site, used to teach a variety of restoration skills which ultimately built social trust and a better understanding of the science behind restoration. It was in these demonstration sites where compromises between social needs, economic needs, and ecological needs were struck. One compromise was limiting the plot diameters of silvicultural treatment, where a flexible mechanism was put in place for these plots to be expanded in the future [

1]. The ability of all stakeholders to arrive at a flexible “zone of agreement” was an enabler for the contract signature. It is likely that this zone will be challenged as restoration and climate evolve, needing adjustment and change, where dispute settling mechanisms (e.g., [

39]) can be applied as enablers to overcome disagreements.

Such a stewardship contract with a demonstration site could be applied to any of the REST-COAST pilot restorations and even to future upscaling projects. The flexibility that stewardship contracts provide foster necessary compromise when working with the multiple actors and various governing systems involved in coastal management. Such contracts, supported by the consensus stemming from demonstration site joint work, can also accommodate updates to technical and financing requirements as ecosystems and their services shift. Demonstration sites with this type of contracts may thus provide a robust enabler to overcome restoration technical, financial, social and governance barriers.

4.4. River Contracts, Italy

River contracts in Italy tackle the general management of their catchment basins, illustrated by a total of sixty-seven contracts in process, of which twelve were signed already in 2012 [

27]. In Italy, the main driver of these contracts are the provinces, although they may not necessarily be in the implementing body once the contract is in place. The implementation of river contracts follows a specific set of steps: first, a preliminary agreement is signed to work toward a contract; second, a phase of site assessments and knowledge creation is conducted; third, a participatory process agrees on measures delineated in the contract; fourth, a defined action plan is put in place; fifth, the final contract is signed. River Contracts thus act as an enabler for participatory restoration, including its monitoring.

This form of contract could be expanded to river-coast continuums in REST-COAST, particularly the Venice Lagoon pilot in the Po river-delta system. The targeted restoration focuses on river-coast ecosystem connectivity, illustrated for the Venice case by the heavy impact of nutrient and pollutant loads from upstream [

8]. As Italy’s governance structure is already adapted to such river contracts, they could be expanded to include river-delta continuums and affected coastal ecosystems.

4.5. Voluntary Wetland Contracts, European Mediterranean

The EU WETNET project (2016-1019) implemented Wetland Contracts to facilitate voluntary stakeholder agreements for the management of protected wetlands [

28]. The purpose of contracts in this case is to build a common strategy for the integrated management of wetlands, coordinating between spatial planning bodies and wetland managers and reducing conflict between economic and conservation targets. The steps of contract development outlined by WETNET can be summarized by: first integrating the knowledge of each stakeholder; second clarifying restoration goals and concerns; and third, agreeing on a site-specific contract. An important enabler has been the role of an international body, like WETNET, to foster a collaboration base across different countries [

16]. Wetland contracts have been accepted as a tool for all Ramsar sites, but contracts have mainly been adopted in countries where initiatives like WETNET took place. This indicates the need to improve supportive governance, as an enabler to the implementation of restoration contracts, adaptable to the context where they are implemented.

In the Mediterranean, managers of Marine Protected Areas (MPA) are challenged by the lack of long-term restoration contracts [

65]. This has led to financial and technical barriers like funding, staffing, data, and equipment constraints. While legislation like the new European Nature Restoration Law can alleviate some of these constraints, the management of available funds, as well as the collaboration between MPA managers, could profit from a contractual body like the one here proposed. This contractual body could secure technical enablers by establishing periodic restoration trainings, communication between MPA managers, and improved baselining methods.

5. Coastal Restoration Agreements: Experiences and Enablers in the REST-COAST Pilot Cases

The REST-COAST pilots are a first step in upscaling coastal restoration to achieve shared benefits such as coastal protection, ecosystem conservation, and livelihood preservation. Governance, economic, social, and technical barriers and enablers have been identified in previous works (e.g., [

11]) and reinforced in the context of coastal ecosystems [

57], where the developed enablers should be applied to overcome restoration barriers at short to long term scales. Applied active and passive techniques, supported by observations and simulations, lead to an improved funding and social engagement, based on the quantified restoration co-benefits. These demonstrated benefits should in turn promote a governance shift to overcome present fragmentation and limited long-term plans for coastal restoration, thereby reducing the current implementation gap. This section will discuss how two REST-COAST pilots are using restoration agreements as a tool to leverage enablers against current barriers, which hamper the adaptation potential of the analyzed coastal systems. The remaining REST-COAST pilots already have the basis for such contracts, which are at different levels of development and always discussed within the Coastal Restoration Platforms established at each of the study sites.

5.1 Declaration of Intent for a Growing Coast, The Netherlands

The Wadden Sea pilot case in REST-COAST, provides an excellent example on how to tackle cross border restoration, where here we shall focus on the restoration of the Ems Estuary near Groningen (

Figure 5). This estuary faces a variety of pressures, including sea level rise, which has placed the surrounding intertidal ecosystems at risk [

71]. Furthermore, navigation pathways and land reclamation have increased water turbidity and influenced tidal dynamics, under the need to dredge surplus sediments. The major risks addressed by the estuarine restoration stem from flooding, erosion and coastal habitat loss, quantitatively assessed from combined observations and simulations (

Figure 6).

This pilot case opted to use a legal contract as the restoration agreement, signed for a ten-year period, with a part of the agreement extending twenty-five years into the future. The contract is divided into five main articles that outline: (a) main actors affected by the restoration; (b) goals of the restoration contract; (c) measures through which these goals will be accomplished; (d) interests of the participating actors; and (e) main intents of the contract. The contract is signed by eight actors, identified in the first article, where the first three are the Province of Groningen, the Emsdelta Municipality, and the Oldambt Municipality. These are the governing bodies tied to the estuary and that set the governance regime. The fourth actor is a local water authority that affects and is affected by the water quality of the estuary. The port authority is included for its role in planning and improving dredging projects. The contract has also involved a regional farming association because sea level rise and the estuary’s soil subsidence put surrounding agricultural fields at risk. Finally, there are two actors that advocate for ecosystem integrity in Groningen, the Groningen Landscape Foundation, and an alliance of climate and nature organizations.

Article 4 outlines each party’s interests and what they expect to gain from the proposed restoration, which can be used as a basis for compromise and conflict solving. Articles 1 and 4 embed social enablers into the contract by developing sufficient communication and agreement between all relevant actors. Article 2 outlines the scope of the contract and what the actors are aiming to achieve by signing it. This article also defines the broader policy goals that will be met by accomplishing the restoration project. These goals are made concrete in Article 3 by defining the main quantifiable actions. Two of these actions address the beneficial use of dredged sediment to (1) raise 300-500 ha of agricultural land safely above sea level and (2) use 2 million cubic meters of clay from the dredged sediment to renovate the Dollard dike. The third restoration measure is to create inland and tidal habitats that promote sedimentation, reduce erosion and promote vertical accretion. A fourth restoration measure concerns the long-term integration of restoration efforts into the desired surrounding landscape evolution. This section embeds technical enablers into the contract by identifying the key biophysical adjustments that must be made to the ecosystem. Article 2, together with Articles 1 and 4, tackle governance enablers by ensuring that relevant governing bodies are included in the contract and that their policy goals are addressed by the restoration.

Article 5 outlines the next steps that must happen to efficiently implement the co-selected measures and achieve the contracts goals. An important section of this article is the description of funding arrangements, identifying existing funding commitments and proposing additional funding as enabler to enhance restoration implementation. Article 5 also highlights the main expected barriers, such as organizational challenges, identifying future steps to overcome them. A similar method is taken to reduce technical barriers, stating the main requirements for ecological plans, together with their monitoring and evaluation for controlled adjustments. In essence, Article 5 plays a pivotal role in the contract, addressing potential governance, social, financial, and technical barriers. Moreover, it introduces a mechanism for adaptability, thereby facilitating future challenges to be reframed and leveraged as enablers.

5.2 Agreement on Cooperation for the Vistula lagoon, Poland

The Vistula Lagoon in Poland is a Natura 2000 site with thirteen endangered migratory bird species that rely on the ecosystem the lagoon provides. The lagoon faced a planned shock in 2020 when a passage to the Baltic Sea was opened on the Polish side of the lagoon [

54]. To compensate for essential habitats lost in the passage construction, a Vistula Lagoon restoration plan was launched, which included building an artificial island in the lagoon (

Figure 7) that can support endangered bird species and lead to biodiversity gains.

The restoration agreement for this lagoon pilot was comparatively simpler to establish, because there are fewer actors involved and, therefore, the existing governance was better suited for the implementation of restoration interventions. The governance structure enabled the implementation of more integrated decisions, all of them coordinated by the Maritime Office, with full responsibility for this task. Thus, the agreement made between the Polish Maritime Office and the Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Hydro-Engineering has acted as an enabler to start filling the implementation gap for all restoration activities, coordinating planning, implementation and monitoring stages of the deployment.

The agreement outlines the roles and responsibilities of the two signing actors, which refer to: (a) restoration aims; (b) restoration responsibilities; (c) supporting cooperation agreements. The document also refers to the technical enablers required, conditioning the building methodology to the soil bearing capacity and the constructed ecosystems to the local climate (

Figure 7), all framed by the available space on the artificial island. Furthermore, there is a clause in the contract that establishes a formal pathway for alterations or renewals of the agreement, depending on the evolution of boundary conditions. This is a provision for flexibility that could be used to resolve future conflicts and is thus an enabler that should be of application in many other restoration contracts. Ultimately, this document is used to formalize the relationship between the governing body and the research institute, securing an efficient governance enabler.

6. Coastal Restoration Platforms: Living Labs to Steer Adaptation Evolution

The set of restoration agreements, either signed or at different levels of development, share a common structure, co-designed by all stakeholders participating in the 9 on-going coastal restoration platforms (COREPLATS) at the 9 pilot sites in the REST-COAST project. The agreements’ contents can be grouped in ten blocks: (a) restoration aims, defining the present and future (target) states; (b) participating stakeholders, describing their roles and legally established competences; (c) adaptation-through-restoration plans, which delineate adaptation pathways with tipping points and consensus sequence of restoration interventions; (d) co-selected metrics to assess coastal risk evolution under changing climate and human pressures, establishing an objective ranking for restoration success; (e) portfolio of co-designed solutions at preliminary design level, including initial and maintenance costs, estimated delivery of ecosystem services and main expected impacts; (f) business models and plans detailing the required funding (mainly public sector) and financing (private investors or joint public-private ventures), based on the monetization of ecosystem services and the initial/maintenance costs; (g) co-selected thresholds to activate initial (yellow warning) and urgent (red warning) interventions to curb increasing risks for natural and socioeconomic assets in the most vulnerable coastal sectors; (h) monitoring and associated maintenance plans, incorporating if available early warning systems (EWS) for short term decisions and climate warning systems (CWS) for long-term decisions; (i) recommendations for a more integrated and proactive governance, together with suggestions for more supportive policies for restoration upscaling; (j) co-designed recommendations to increase the pace and scale of restoration, overcoming site-specific barriers (as found in the project pilot cases).

These restoration agreements, developing the sequenced application of interventions that combine technical, economic and governance advances, share a common structure supplemented by Pilot specific clauses. Such a common structure contains the following headings: a) Coastal risk reduction under evolving climate and human pressures; b) Target socioeconomic and environmental status; c) Portfolio of interventions to enhance resilience and limit negative impacts; d) Adaptation plan for compatible short to long term interventions; e) Climatic justice plan for an ethical use of scarce natural resources such as accommodation space [

35] or freshwater volume); f) Circular economy plan to enhance the restoration financial sustainability under a limited coastal carrying capacity. These chapters are tailored to the specific needs of each study case, as set out by each COREPLAT, a co-management table that regularly assembles all key stakeholders to monitor, evaluate and maintains restoration by consensus agreements and joint work. The COREPLATS aim to accelerate the scale and pace for co-designed interventions, supported by engineering and financial provisioning to make restoration commensurate with climatic acceleration. These platforms, structured as living labs, integrate the needs and criteria of participating stakeholders, which include public ones (coastal protection, land planning or river regulation administrations), NGOs, citizen groups dealing with scarce resources, biodiversity organizations and private groups (e.g. tackling risks or finance).

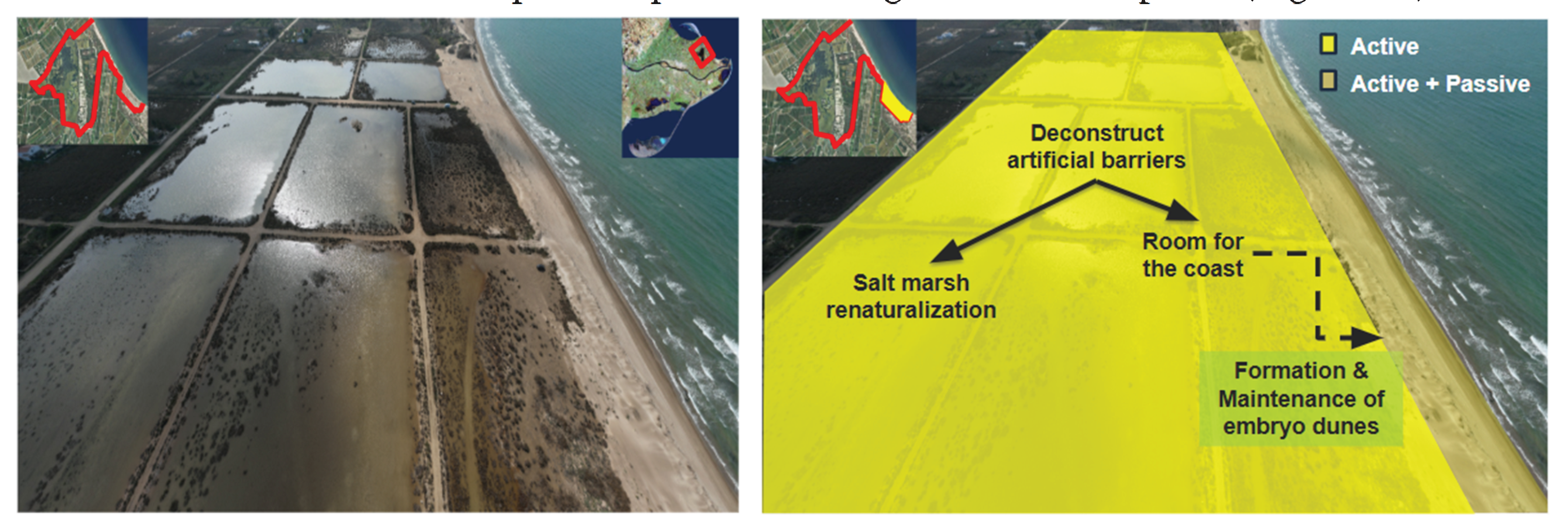

The COREPLATS running in all Pilot sites promote adaptation-through-restoration plans, which favor restoration for degraded coastal environments to achieve an adaptation that is effective and that reduces the carbon footprint of traditional coastal protection. These plans, supported by the technical, financial and governance advances achieved [

34,

52,

58], are framed within adaptation pathways and steered by consensus metrics. Consensus metrics enable a regular assessment of implementation effectiveness and maintenance needs to enhance the delivery of short to long-term ecosystem services. These metrics refer to key variables for biophysical drivers (e.g. temperature, wave energy, sea-level, pollutant/nutrient concentrations), responses (e.g. erosion rates, flood extent/duration, water quality, biodiversity status, ecosystem service delivery) and socioeconomic impacts (e.g. risk levels, investment needs, revenue generation). Restoration plans, supported by these metrics, are being deployed in time and space according to the co-selected adaptation pathways with consensus change stations and tipping points, informed by regular assessments of the implemented interventions in terms of impact, cost and effectiveness. The proposed interventions, illustrated for the Ebro river-coast pilot case (

Figure 8) by controlled river pulses, enhanced coastal roughness and natural conveyor belts for coastal sand fluxes [

58], have the overarching aim of reconnecting rivers to coasts and people to nature.

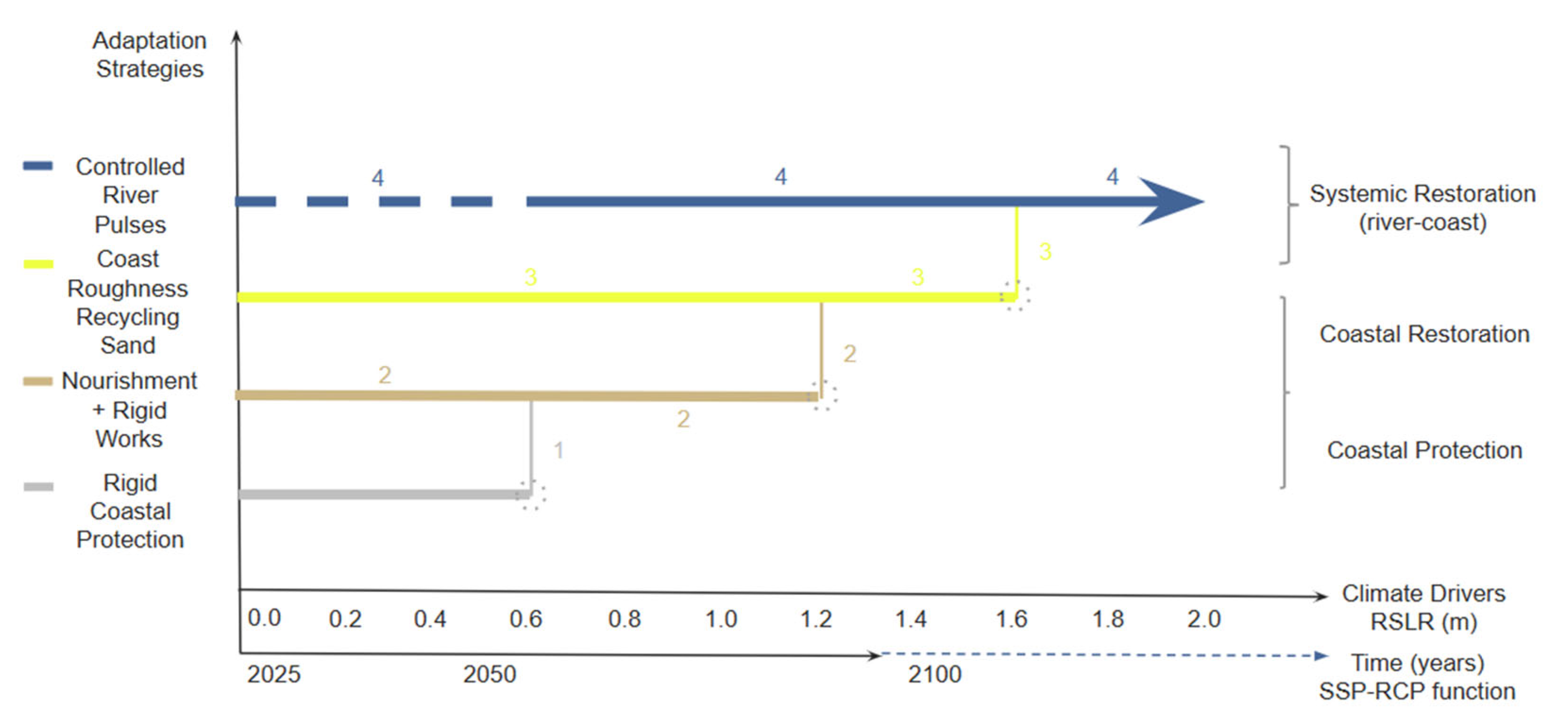

The portfolio of co-selected restoration interventions, prepared at draft-project level but with costs and impacts, should be sequenced along the co-designed adaptation pathways, with deadlines and implementation warnings displayed along the horizontal time axis (

Figure 9). Such interventions should be implemented and maintained according to the predictions and projections provided by the EWS and CWS available in some pilot cases, which should also support the engineering required for the delivery of targeted ecosystem services [

58]. These simulations, nested within Copernicus products which provide high-resolution boundary data for European coasts, should progressively incorporate the error intervals derived from field observations (

Figure 10) [

58].

Figure 10: Sample results from the “What-if Scenario” & CWS for proactive adaptation decisions in the Ebro delta (med Sea) at short to long time scales: (

a) EWS at a barrier beach, showing breaching without embryo dunes (left) and resilience by embryo dunes (right); (

b) CWS built with RSLR as basic independent variable (horizontal axis), translated into time depending on the selected scenarios (right), and a risk/resilience indicator (sand deficit, beach width deficit and risk) in the vertical axis (adapted from [

58])

Adaptation-through-restoration plans must also address the provisioning of funds by public and private means, including business plans for enhanced investment and recommendations to increase and accelerate the contributions by administrations (e.g. enabled land areas, ecological permits, timely impact assessments) and other social actors. Distributed funding, supported by blockchain-based certificates has been explored in a number of sectors, since it provides a transparent and efficient certification system. This funding, already applied in forest restoration and cultural heritage [

33,

40] has also been promoted by finance companies, such as the Priceless Planet Coalition by Mastercard, which in 2024 expanded its portfolio of restoration sites [

41]. Following this course, joint public-private ventures and private investments, including those supported by blockchain electronic ledgers, the restoration pace can be increased based on growing consensus and co-responsibility.

Co-designed adaptation pathways offer a structured solution to increase funding and supportive governance for upscaled restoration, filling the current implementation gap and adaptation deficit that coasts are facing. The business plans proposed for the REST-COAST Pilots contribute to increase and make more specific the social-ecological shared benefits from restoration, setting out the newly generated revenue streams from delivered ecosystem services [

18]. These achievements can be demonstrated by making more explicit the enhanced delivery of ecosystem services and co-benefits for all investors, associated to a proactive implementation and maintenance of restoration interventions. Such plans, supported by socioeconomic engagement and consensus derived from the COREPLATS, should be monitored and maintained by applying the developed EWS and CWS, which enable to sequence and priorities the co-selected solutions within a plan for upscaling restoration (

Figure 11).

Continuous monitoring for maintenance is thus a key element of these plans, where new data register the performance of restoration interventions and delivered co-benefits, regularly discussed within the COREPLATs to increase socio-economic engagement through improved perception and awareness. The resulting engagement supports the shift in governance required for restoration upscaling, supported by the advances in technical practice, financial mechanisms and governance shift embedded in the developed adaptation-through-restoration plans (

Figure 12).

7. Discussion and Conclusions: Restoration Sustainability

Coastal restoration agreements, supported by restoration platforms like the COREPLATS established within the REST-COAST project, can act as enablers to overcome the multiple barriers that hider a wider restoration uptake. By embedding governance, financial, social, and technical enablers directly into the contractual text, these agreements foster collaboration, secure long-term funding, and ensure an adaptive management that leads to restoration upscaling. Such upscaling is key for a sufficient delivery of ecosystem services [

57] that effectively curb coastal risks under the projected climate change acceleration.

The enablers developed to overcome barriers in the different pilots can be illustrated by: a) new techniques for restoration (e.g. biomimetic devices or embryo dunes with wrack cores); b) new management based on proactive interventions and maintenance (e.g. deadlines for interventions derived from monitoring and the warning systems); c) enhanced funding and financing (e.g. co-designed business plans with public-private joint ventures); d) flexible adaptation-through-restoration plans that combine NbS building blocks (e.g. river-coast connectivity or constructed coastal roughness); e) governance transformation with more integration for systemic assessments (e.g. low carbon protection, coasts in Nationally Determined Contributions); e) new policies for coastal restoration based on effectiveness and risk reduction, as directed by the new European Nature Restoration Law [

29], relevant EU Directives, US landscape approach restoration or Australian land-based covenants [

6].

The proposed contracts, tailored to the social-ecological features for each of the REST-COAST pilot cases, address local challenges and incorporate place-based criteria, aligning relevant stakeholders with shared restoration goals. These contracts serve not only as a tool for overcoming specific barriers but also as instruments of opportunity, ensuring that restoration upscaling can evolve alongside changing ecological, social and economic contexts. The lessons learned from contracts developed for forests, rivers, wetlands and other coastal systems, together with the expertise gained in restoration agreements and platforms within REST-COAST, offer valuable insights for upscaling restoration to worldwide coasts to increase preparedness for a global climate change. By applying restoration indicators and the innovative advances in techniques, funding and governance, it should be easier to export the gains in environmental health and socioeconomic livelihood to many vulnerable coastal systems, advancing towards standardized criteria for restoration performance. The proposed contractual approach, supported by platforms organized as living labs for the REST-COAST pilot cases [

57], can steer an efficient restoration upscaling to fill the present implementation deficit, promoting the use of the obtained enablers (referred to techniques, financing and governance) for a proactive coastal restoration worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and A.S-A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.; writing—review and editing, M.D., A.S-A.Jr., A.S-A., X.S-A.; visualization, all co-authors; supervision, A.S-A. and V.G.; project administration, A.S-A., D.G-M and V.G.; funding acquisition, D.G-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Rest-Coast EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation project (grant No. 101037097).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are only available upon request from the corresponding author due to the various sources of origin.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge the support and contributions from all REST-COAST partners.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Funding parties had no role in the writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMU |

Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, und Reaktorsicherheit |

| COREPLATS |

Coastal Restoration Platforms |

| CWS |

Climate Warning System |

| ER |

Ecological Restoration |

| EU |

European Union |

| EWS |

Early Warning System |

| GDF |

Global Biodiversity Framework |

| MPA |

Marine Protected Area |

| NbS |

Nature-based Solution |

| NGO |

Non-governmental Organization |

| NRL |

Nature Restoration law |

| REST-COAST |

Large Scale Restoration of Coastal Ecosystems through Rivers to Sea Connectivity |

| SAC |

Special Area of Conservation |

| SLR |

Sea-level Rise |

| SPA |

Special Protected Area |

| WETNET |

Coordinated Management and Networking of Mediterranean Wetlands Project |

References

- Abrams, J.; Burns, S. Case study of a community stewardship success: The White Mountain Stewardship Contract. Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2007. Available online: https://openknowledge.nau.edu/id/eprint/1294/1/Abrams_Burns_2007_ERIWhitePaper_CaseStudyOfACommunity.pdf.

- Affolder, N. Transnational conservation contracts. Leiden J. Int. Law 2012, 25, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apine, E.; Stojanovic, T. Is the coastal future green, grey or hybrid? Diverse perspectives on coastal flood risk management and adaptation in the UK. Camb. Prisms: Coast. Futures 2024, 2, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkema, K.K.; Guannel, G.; Verutes, G.; Wood, S.A.; Guerry, A.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Kareiva, P.; Lacayo, M.; Silver, J.M. Coastal habitats shield people and property from sea-level rise and storms. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, V.; van de Lageweg, W.I.; Terpstra, T.; Buijs, J.-M.; de Reus, K.; de Groot, F.; van Schaik, R.; Habte, M.A.; Schram, J.; Hoogenboom, T. The impact of coastal realignment on the availability of ecosystem services: Gains, losses and trade-offs from a local community perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell-James, J.; Fitzsimons, J.A.; Lovelock, C.E. Land tenure, ownership and use as barriers to coastal wetland restoration projects in Australia: Recommendations and solutions. Environ. Manag. 2023, 72, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, S.; Dudley, N.; Hall, C.; Keeneleyside, K.; Stolton, S. Ecological Restoration for Protected Areas: Principles, Guidelines and Best Practices; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/10205 (accessed on 31 August 2025)ISBN 978-2-8317-1533-9.

- Campostrini, P.; Dabalà, C.; Coccon, F.; Torresan, S.; Furlan, E.; Horneman, F.; Critto, A.; Pranovi, F.; Rova, S.; Barausse, A.; et al. Venice Lagoon Pilot Fact Sheet. 2024. Available online: https://rest-coast.eu/storage/app/media/pilots/Venice%20Lagoon_2024.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Caneva, G.; Ceschin, S.; Lucchese, F.; Scalici, M.; Battisti, C.; Tufano, M.; Tullio, M.C.; Cicinelli, E. Environmental management of waters and riparian areas to protect biodiversity through River Contracts: The experience of Tiber River (Rome, Italy). River Res. Appl. 2021, 37, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.-M.; Silliman, B.; Wong, P.P.; van Wesenbeeck, B.; Kim, C.-K.; Guannel, G. Coastal adaptation with ecological engineering. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina-Segarra, J.; García-Sánchez, I.; Grace, M.; Andrés, P.; Baker, S.; Bullock, C.; Decleer, K.; Dicks, L.V.; Fisher, J.L.; Frouz, J.; et al. Barriers to ecological restoration in Europe: Expert perspectives. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle, J.; Briere, C. Arcachon Bay Pilot Fact Sheet. Available online: https://rest-coast.eu/storage/app/media/pilots/Arcachon_Bay_english.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Danley, B.; Widmark, C. Evaluating conceptual definitions of ecosystem services and their implications. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 126, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.W.; Rybczyk, J.M. Global change impacts on the future of coastal systems: Perverse interactions among climate change, ecosystem degradation, energy scarcity, and population. In Coasts and Estuaries; Wolanski, E., Day, J.W., Elliott, M., Ramachandran, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demant, L.; Bergmeier, E.; Walentowski, H.; Meyer, P. Suitability of contract-based nature conservation in privately-owned forests in Germany. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 42, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernoul, L.; Vera, P.; Gusmaroli, G.; Muccitelli, S.; Pozzi, C.; Magaudda, S.; Horvat, K.P.; Smrekar, A.; Satta, A.; Monti, F. Use of voluntary environmental contracts for wetland governance in the European Mediterranean region. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2021, 73, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Restoring ecosystems under the Green Deal Call: Recovering biodiversity and connecting to nature; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Favero, F.; Hinkel, J. Key innovations in financing nature-based solutions for coastal adaptation. Climate 2024, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagin, R.A.; Lerner, J.E.; Noyola, C.; Huff, T.P.; Madewell, J.; Balboa, B. Hypersalinity in coastal wetlands and potential restoration solutions, Lake Austin and East Matagorda Bay, Texas, USA. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 50829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandino, G.; Elliff, C.I.; Silva, I.R. Ecosystem-based management of coastal zones in face of climate change impacts: Challenges and inequalities. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 215, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernow, B.E. A Brief History of Forestry: In Europe, the United States and Other Countries; DigiCat: [Online] 2022. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/48874/48874-h/48874-h.htm (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Gann, G.D.; McDonald, T.; Walder, B.; Aronson, J.; Nelson, C.R.; Jonson, J.; Hallett, J.G.; Eisenberg, C.; Guariguata, M.R.; Liu, J.; et al. International principles and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2019, 27(S1), S1–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garen, E.J.; Saltonstall, K.; Ashton, M.S.; Slusser, J.L.; Mathias, S.; Hall, J.S. The tree planting and protecting culture of cattle ranchers and small-scale agriculturalists in rural Panama: Opportunities for reforestation and land restoration. For. Ecol. Manage. 2011, 261, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladstone-Gallagher, R.V.; Thrush, S.F.; Low, J.M.L.; Pilditch, C.A.; Ellis, J.I.; Hewitt, J.E. Toward a network perspective in coastal ecosystem management. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 346, 119007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Oakley, J.A.; Williams, A.T. Use of ecosystems in coastal erosion management. Ocean Coast. Manage. 2018, 156, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, V.; Sierra, J.P.; Caballero, A.; García-León, M.; Mösso, C. A methodological framework for selecting an optimal sediment source within a littoral cell. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmaroli, G. Dieci anni di Contratti di Fiume in Italia: dai risultati del primo censimento alla proposta di un osservatorio. In VII Tavolo Nazione dei Contratti di Fiume, Bologna,; 2012. Available online: https://partecipa.gov.it/assemblies/contratti-di-fiume (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Gusmaroli, G.; Dodaro, G.; Schipani, I.; Perin, C.; Alberti, F.; Magaudda, S. Wetland Contracts: Voluntary-Based Agreements for the Sustainable Governance of Mediterranean Protected Wetlands. In Recent Advances in Environmental Science from the Euro-Mediterranean and Surrounding Regions; Ksibi, M., Ghorbal, A., Chakraborty, S., Chaminé, H.I., Barbieri, M., Guerriero, G., Hentati, O., Negm, A., Lehmann, A., Römbke, J., Costa Duarte, A., Xoplaki, E., Khélifi, N., Colinet, G., Miguel Dias, J., Gargouri, I., Van Hullebusch, E.D., Sánchez Cabrero, B., Ferlisi, S., Naddeo, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 2157–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, D.; Schürings, C.; Wenskus, F.; Blackstock, K.; Borja, A.; Birk, S.; Bullock, C.; Carvalho, L.; Dagher-Kharrat, M.B.; Lakner, S.; et al. Securing success for the Nature Restoration Laws. Science 2023, 382, 1248–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkel, J.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Brown, S.; Jiménez, J.A.; Lincke, D.; Nicholls, R.J.; Scussolini, P.; Sanchez-Arcilla, A.; Vafeidis, A.; Addo, K.A. The ability of societies to adapt to twenty-first-century sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D. Restoring tropical forests from the bottom up. Science 2017, 355(6324), 455–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D. Primer of ecological restoration. Island Press. 2020. ISBN: 9781610919739.

- Howson, P.; Oakes, S.; Baynham-Herd, Z.; Swords, J. Cryptocarbon: The promises and pitfalls of forest protection on a blockchain. Geoforum 2019, 100, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüsken, L.M.; Slinger, J.H.; de Rijk, S.; Altamirano, M.A.; Vreugdenhil, H.S. Overcoming financial barriers to ecological restoration–The case of the Marker Wadden. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 219, 107706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.W.T.; Cooper, J.A.G. Geological control on beach form: Accommodation space and contemporary dynamics. J. Coast. Res. 2009, 69–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25737539.

- Kisacik, D.; Tarakcioglu, G.O.; Cappietti, L. Adaptation measures for seawalls to withstand sea-level rise. Ocean Eng. 2022, 250, 110958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, E.; Pedersen, O.W. Restoring the regulated: The EU’s Nature Restoration Law. J. Environ. Law 2025, eqae032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, S.; Qian, L.; Wang, Z.; Cao, C.; Gao, Q.; Cai, J. Characteristics and evaluation of living shorelines: A case study from Fujian, China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13(7), 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, B. Legal instruments in private land conservation: The nature and role of conservation contracts and conservation covenants. Restor. Ecol. 2016, 24(5), 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, F.; Shui, W. Blockchain in digital cultural heritage resources: Technological integration, consensus mechanisms, and future directions. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.H.M.; Thompson, B.S.; Harris, J.L. Financing forest restoration: The distribution and role of green FinTech in nature-based solutions to climate change. Finance Space 2025, 2(1), 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macreadie, P.I.; Costa, M.D.P.; Atwood, T.B.; Friess, D.A.; Kelleway, J.J.; Kennedy, H.; Lovelock, C.E.; Serrano, O.; Duarte, C.M. Blue carbon as a natural climate solution. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2(12), 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, P.A.; Arroyo, A.; Costa, G. EU Nature Restoration Regulation and REST-COAST: Setting the basis for coastal restoration (Grand Agreement No. 101037097; Deliverable D5.5.). EU Horizon 2020 REST-COAST Project. 2024. https://rest-coast.eu/storage/app/uploads/public/674/583/097/674583097d9ea720789462.pdf#Policy%20Brief.

- Mayes, W.M.; Batty, L.C.; Younger, P.L.; Jarvis, A.P.; Kõiv, M.; Vohla, C.; Mander, U. Wetland treatment at extremes of pH: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407(13), 3944–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentaschi, L.; Vousdoukas, M.I.; Pekel, J.-F.; Voukouvalas, E.; Feyen, L. Global long-term observations of coastal erosion and accretion. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8(1), 12876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestres, M.; Team. Ebro Delta_2024. 2024. https://rest-coast.eu/storage/app/media/pilots/Ebro%20Delta_2024.pdf.

- Morris, R.L.; Konlechner, T.M.; Ghisalberti, M.; Swearer, S.E. From grey to green: Efficacy of eco-engineering solutions for nature-based coastal defence. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24(5), 1827–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta Zanin, G.; Muwafu, S.P.; Máñez Costa, M. Nature-based solutions for coastal risk management in the Mediterranean basin: A literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musumeci, R.E.; Marino, M.; Cavallaro, L.; Foti, E. Does coastal wetland restoration work as a climate change adaptation strategy? The case of the south-east of Sicily coast. Coast. Eng. Proc. 2022, 37, Article 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Icely, J.; Cristina, S.; Perillo, G.M.E.; Turner, R.E.; Ashan, D.; Cragg, S.; Luo, Y.; Tu, C.; Li, Y.; et al. Anthropogenic, direct pressures on coastal wetlands. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Woodroffe, C.; Burkett, V. Chapter 20—Coastline degradation as an indicator of global change. In Climate Change (Second Edition); Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernice, U.; Coccon, F.; Horneman, F.; Dabalà, C.; Torresan, S.; Puertolas, L. Co-developing business plans for upscaled coastal nature-based solutions restoration: An application to the Venice Lagoon (Italy). Sustainability 2024, 16(20).

- Prach, K.; Durigan, G.; Fennessy, S.; Overbeck, G.E.; Torezan, J.M.; Murphy, S.D. A primer on choosing goals and indicators to evaluate ecological restoration success. Restor. Ecol. 2019, 27(5), 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różyński, G. Vistula Lagoon Artificial Island Pilot Fact Sheet. 2024. https://rest-coast.eu/storage/app/media/pilots/Vistula_2024.pdf.

- Saintilan, N.; Horton, B.; Törnqvist, T.E.; Ashe, E.L.; Khan, N.S.; Schuerch, M.; Perry, C.; Kopp, R.E.; Garner, G.G.; Murray, N.; et al. Widespread retreat of coastal habitat is likely at warming levels above 1.5 °C. Nature 2023, 621(7977), 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; García-León, M.; Gracia, V.; Devoy, R.; Stanica, A.; Gault, J. Managing coastal environments under climate change: Pathways to adaptation. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 1336–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; Cáceres, I.; Roux, X.L.; Hinkel, J.; Schuerch, M.; Nicholls, R.J.; Otero del, M.; Staneva, J.; de Vries, M.; Pernice, U.; et al. Barriers and enablers for upscaling coastal restoration. Nature-Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; Garrote, L.; Gracia, V.; Cáceres, I.; Sánchez-Artús, X.; Caiola, N.; Espanya, A.; Espino, M.; García, M.Á.; Grassa, J.M.; et al. Trade-offs and synergies in river-coastal restoration for the Ebro case (Spanish Mediterranean). Nature Conserv. 2025, 59, 101–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Artús, X.; Subbiah, B.; Gracia, V.; Espino, M.; Grifoll, M.; Espanya, A.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Evaluating barrier beach protection with numerical modelling. A practical case. Coast. Eng. 2024, 191, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Artús, X.; Gracia, V.; Espino, M.; Grifoll, M.; Simarro, G.; Guillén, J.; … Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Operational hydrodynamic service as a tool for coastal flood assessment. Ocean Sci. 2025, 21(2), 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuerch, M.; Kiesel, J.; Boutron, O.; Guelmami, A.; Wolff, C.; Cramer, W.; Caiola, N., Ibáñez, C., Vafeidis, A. T. (2025). Large-scale loss of Mediterranean coastal marshes under rising sea levels by 2100. Communications Earth & Environment, 6(1), 128. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, T.; Temmerman, S.; Kirwan, M.L.; Wolff, C.; Lincke, D.; McOwen, C.J.; Pickering, M.D.; Reef, R.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Hinkel, J.; et al. Future response of global coastal wetlands to sea-level rise. Nature 2018, 561(7722), 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusser, J.L.; Calle, A.; Garen, E. 1.2 Sustainable ranching and restoring forests in agricultural landscapes, Panama. 2015. https://hdl.handle.net/10088/28940.

- Spalding, M.D.; Ruffo, S.; Lacambra, C.; Meliane, I.; Hale, L.Z.; Shepard, C.C.; Beck, M.W. The role of ecosystems in coastal protection: Adapting to climate change and coastal hazards. Ocean Coast. Manage. 2014, 90, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, A.; Luijendijk, A.P.; van Oudenhoven, A.P.E. The grey–green spectrum: A review of coastal protection interventions. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 311, 114824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, M.; Puig Marti, P. Inventory report on restoration needs, competencies, and capacity building in Mediterranean MPAs. MedPAN. Funded by the EU RESTO-COAST project. 2025. https://medpan.org/sites/default/files/media/downloads/inventory_report_on_restoration_needs.docx.pdf.

- Temmerman, S.; Meire, P.; Bouma, T.J.; Herman, P.M.J.; Ysebaert, T.; De Vriend, H.J. Ecosystem-based coastal defence in the face of global change. Nature 2013, 504(7478), 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmerman, S.; Horstman, E.M.; Krauss, K.W.; Mullarney, J.C.; Pelckmans, I.; Schoutens, K. Marshes and mangroves as nature-based coastal storm buffers. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2023, 15, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA; USFS. Stewardship contracting: Basic stewardship contracting concepts. 2009. https://www.fs.usda.gov/restoration/documents/stewardship/stewardship_brochure.pdf.

- Van Coppenolle, R.; Temmerman, S. Identifying global hotspots where coastal wetland conservation can contribute to nature-based mitigation of coastal flood risks. Glob. Planet. Change 2020, 187, 103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltham, N.J.; Elliott, M.; Lee, S.Y.; Lovelock, C.; Duarte, C.M.; Buelow, C.; Simenstad, C.; Nagelkerken, I.; Claassens, L.; Wen, C.K.-C.; et al. UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2030—What chance for success in restoring coastal ecosystems? Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanke, S.; Baptist, M.; Jacob, B. Wadden Sea/Ems Dollard Pilot Fact Sheet. 2022. https://rest-coast.eu/storage/app/media/pilots/Wadden%20Sea_2022.pdf.

- Weaver, R.J.; Stehno, A.L. Mangroves as coastal protection for restoring low-energy waterfront property. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12(3), 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Biber, P.; Bethel, M. Thresholds of sea-level rise rate and sea-level rise acceleration rate in a vulnerable coastal wetland. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7(24), 10890–10903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wan, L. Coastal ecological and environmental management under multiple anthropogenic pressures: A review of theory and evaluation methods. In Current Trends in Estuarine and Coastal Dynamics; Wang, X.H., Qiao, L., Mitchell, S., Elliott, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Visual summary of the 9 pilot restoration cases in the Rest-Coast project. These pilots provide demonstrators on how to achieve coastal risk reduction under climate change, based on enhanced connectivity and dynamics for a sustained delivery of ecosystem services.

Figure 1.

Visual summary of the 9 pilot restoration cases in the Rest-Coast project. These pilots provide demonstrators on how to achieve coastal risk reduction under climate change, based on enhanced connectivity and dynamics for a sustained delivery of ecosystem services.

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagram linking the proposed Rest-Coast barriers and enablers. The application of these enablers to the 3 targeted ecosystem types serves to overcome current barriers against large scale restorations, contributing to fill the present implementation deficit, projected to increase under climate change.

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagram linking the proposed Rest-Coast barriers and enablers. The application of these enablers to the 3 targeted ecosystem types serves to overcome current barriers against large scale restorations, contributing to fill the present implementation deficit, projected to increase under climate change.

Figure 3.

Sample illustration of the predictions produced in the REST-COAST project for two of the restoration pilot cases, both in the Mediterranean Sea: (

a) Venice lagoon (left); (

b) Ebro delta coast (right), after [

59].

Figure 3.

Sample illustration of the predictions produced in the REST-COAST project for two of the restoration pilot cases, both in the Mediterranean Sea: (

a) Venice lagoon (left); (

b) Ebro delta coast (right), after [

59].

Figure 4.

Sample illustration of the projections produced in the REST-COAST project for two of the restoration pilot cases, in the Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea: (a) Wadden Sea protection with seagrass buffer areas (left); (b) Venice lagoon hypoxia events with seasonal and monthly resolution (right).

Figure 4.

Sample illustration of the projections produced in the REST-COAST project for two of the restoration pilot cases, in the Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea: (a) Wadden Sea protection with seagrass buffer areas (left); (b) Venice lagoon hypoxia events with seasonal and monthly resolution (right).

Figure 5.

Restoration of the Wadden Sea and Ems estuary, implementing the portfolio of co-designed NbS solutions, where researchers and stakeholders from the Rest-Coast coastal restoration platform participate.

Figure 5.

Restoration of the Wadden Sea and Ems estuary, implementing the portfolio of co-designed NbS solutions, where researchers and stakeholders from the Rest-Coast coastal restoration platform participate.

Figure 6.

Sample simulations for: (a) reduction of Hs (significant wave height) along the Ems estuary boundary considering SLR and restoration (top left) and projected habitats for the Wadden Sea (top right) by 2090; (b) reduction of flow velocities over present (left) and restored (right) seagrass areas for a 20-year return period event of moderate energy.

Figure 6.

Sample simulations for: (a) reduction of Hs (significant wave height) along the Ems estuary boundary considering SLR and restoration (top left) and projected habitats for the Wadden Sea (top right) by 2090; (b) reduction of flow velocities over present (left) and restored (right) seagrass areas for a 20-year return period event of moderate energy.

Figure 7.

Constructed island for habitat compensation and biodiversity gains in the Vistula lagoon, where the initial design was based on a geotube-based rim (top) that became too unreliable due to high and uneven subsidence risk and had to be replaced by Larsen sheet piles, with 2 rows of 13 m long units forming a 1192 x 1932 ellipse (bottom left) whose soil properties (level, moisture, organic matter, etc.) are being regularly monitored.

Figure 7.

Constructed island for habitat compensation and biodiversity gains in the Vistula lagoon, where the initial design was based on a geotube-based rim (top) that became too unreliable due to high and uneven subsidence risk and had to be replaced by Larsen sheet piles, with 2 rows of 13 m long units forming a 1192 x 1932 ellipse (bottom left) whose soil properties (level, moisture, organic matter, etc.) are being regularly monitored.

Figure 8.

Systemic restoration plans, deployed across the river-delta-coast continuum according to co-selected adaptation pathways with consensus tipping points for the Ebro river-coast system in the Spanish Mediterranean coast. The adaptation-through-restoration plans combine the recovered river-coast connectivity and natural coastal dynamics based on enhanced coastal roughness, maintained though a systemic monitoring plan that spans river, coastal and sea domains.

Figure 8.

Systemic restoration plans, deployed across the river-delta-coast continuum according to co-selected adaptation pathways with consensus tipping points for the Ebro river-coast system in the Spanish Mediterranean coast. The adaptation-through-restoration plans combine the recovered river-coast connectivity and natural coastal dynamics based on enhanced coastal roughness, maintained though a systemic monitoring plan that spans river, coastal and sea domains.

Figure 9.

Set of co-designed adaptation strategies for the Ebro Pilot as an illustration of vulnerable river-coast systems in the Mediterranean Sea. Sequenced interventions are to be deployed along adaptation pathways, as a function of relative SLR or the combination of climatic drivers considered, where dashed grey circles denote change stations, warning that tipping points (not shown for clarity) are getting closer. These climatic drivers are then translated into time depending on the family of co-selected scenarios (horizontal axis).

Figure 9.

Set of co-designed adaptation strategies for the Ebro Pilot as an illustration of vulnerable river-coast systems in the Mediterranean Sea. Sequenced interventions are to be deployed along adaptation pathways, as a function of relative SLR or the combination of climatic drivers considered, where dashed grey circles denote change stations, warning that tipping points (not shown for clarity) are getting closer. These climatic drivers are then translated into time depending on the family of co-selected scenarios (horizontal axis).

Figure 10.