Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

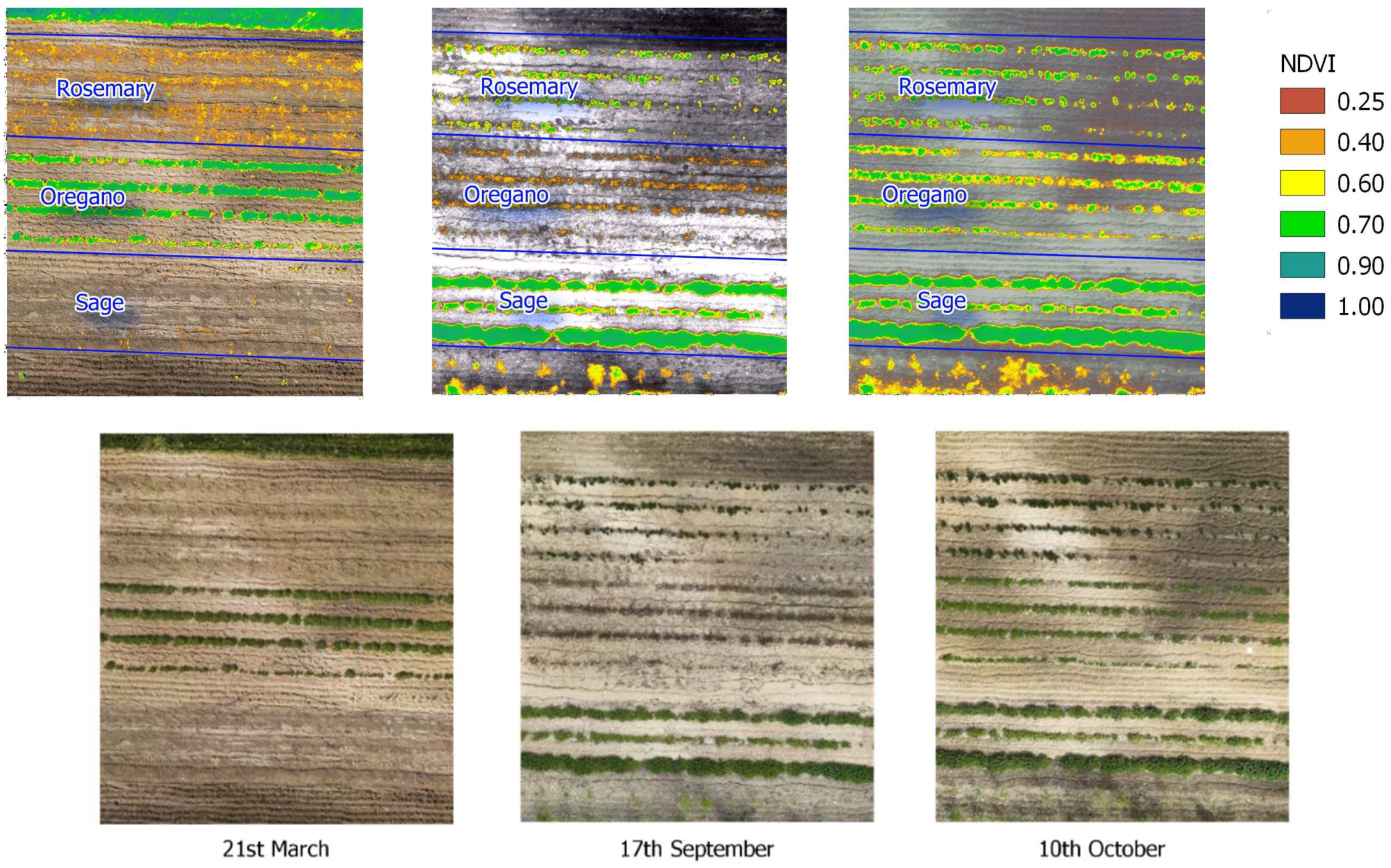

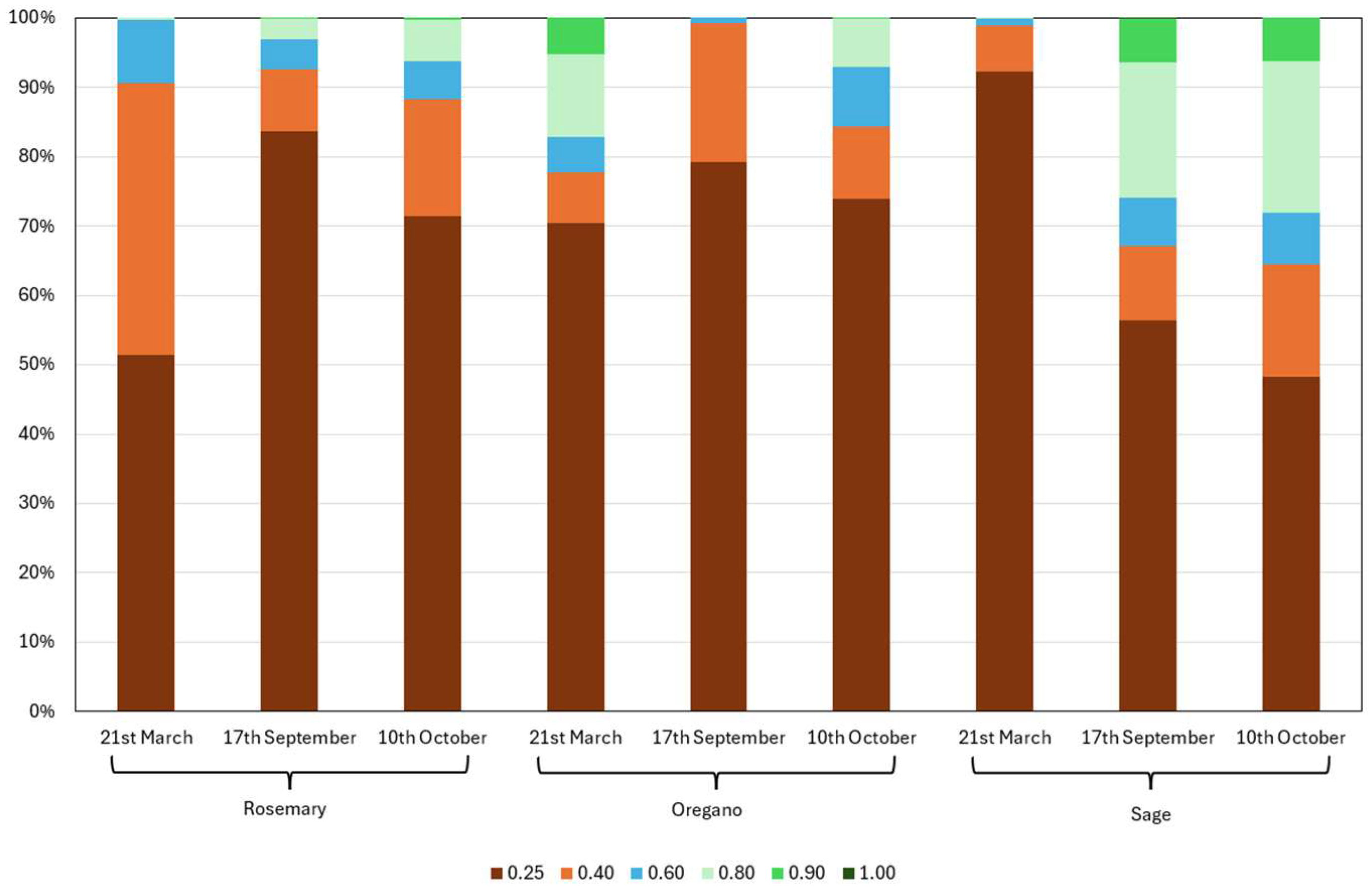

2.1. Precision Aromatic Crop (PAC) Techniques

2.2. Analyses of Essential Oils

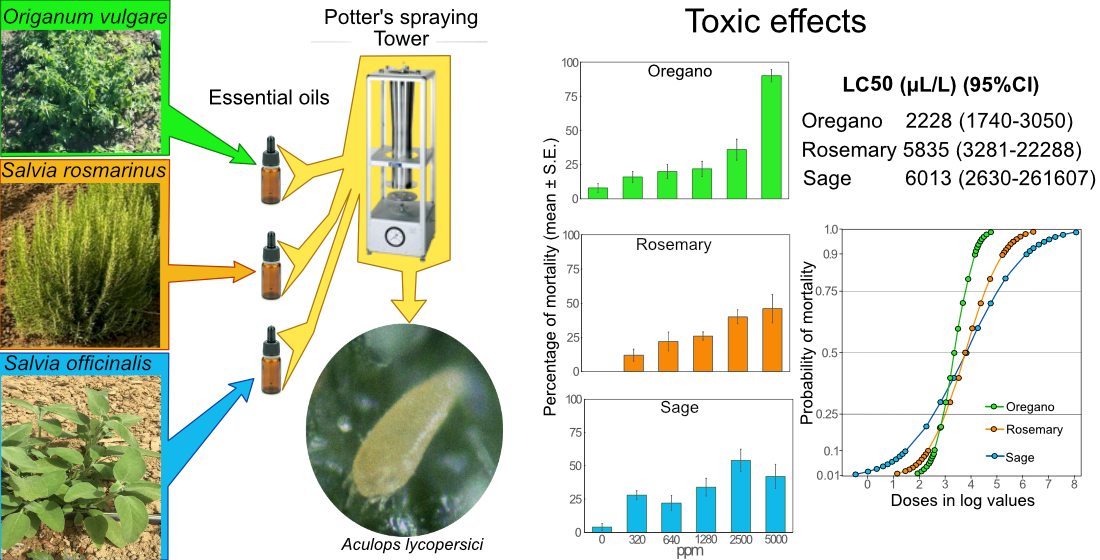

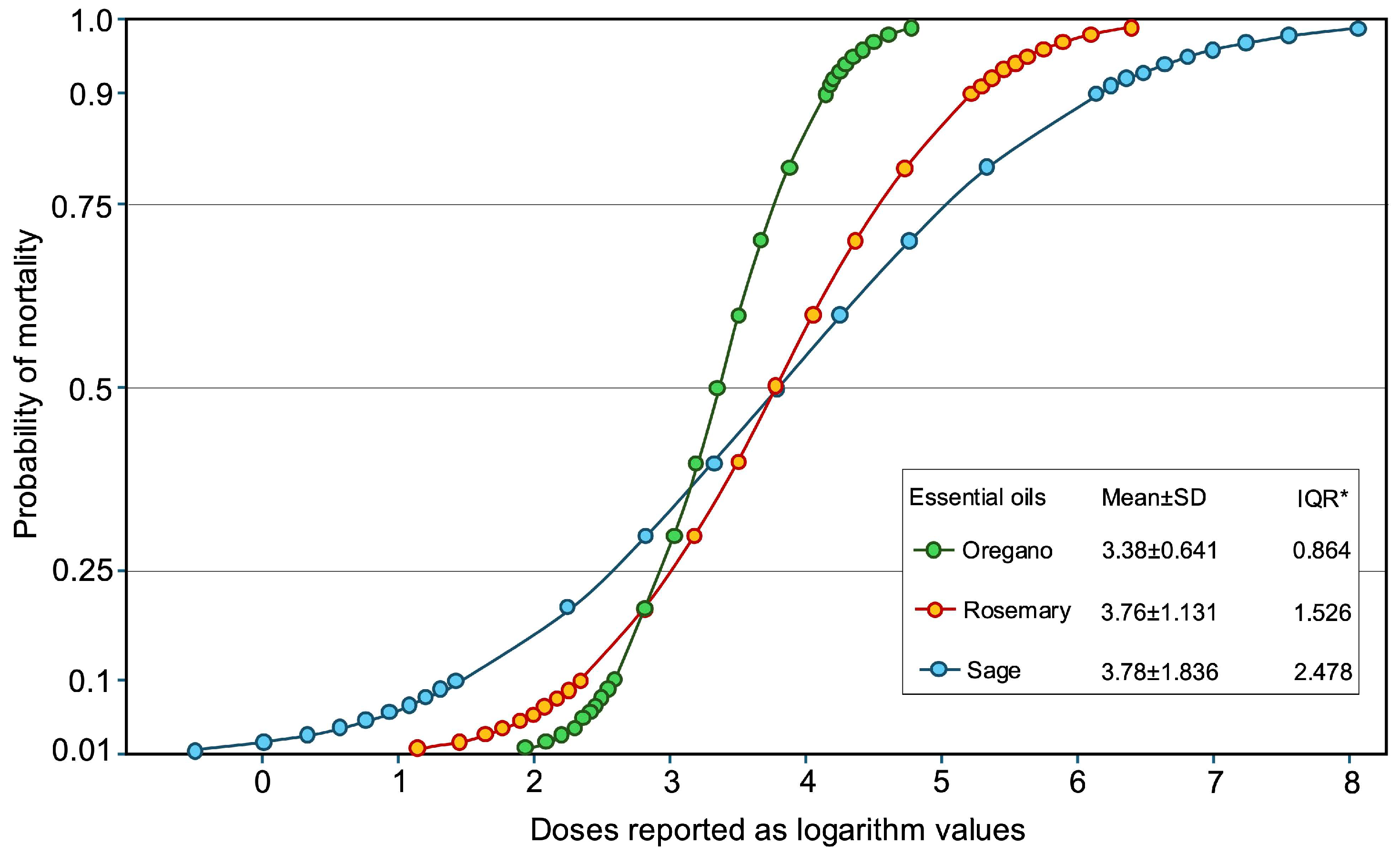

2.3. Toxicity of O. vulgare, S. rosmarinus, and S. officinalis EOs Against A. lycopersici

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cultivation of Officinal Plants with Precision Aromatic Crops (PAC) Techniques, and Essential Oil Extraction Methods

4.1.1. Plants Cultivation Method

4.1.2. Precision Aromatic Crop (PAC) Techniques

4.1.3. Extraction and Analyses of Essential Oils

4.2. Aculops lycopersici Experimental Set-Up

4.2.1. Solanum nigrum Seedlings for A. lycopersici Breeding

4.2.2. Adult Cohort for the Experiments

4.2.3. Experimental Units

4.2.4. Effects of Essential Oils on A. lycopersici

4.2.5. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindquist, E.E.; Sabelis, M.W.; Bruin, J. Eriophyoid Mites. Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control; Elsevier Science Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996.

- Pfaff, A.; Gabriel, D.; Böckmann, E. Observation and Restriction of Aculops lycopersici Dispersal in Tomato Layer Cultivation. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2024, 131, 155–166. [CrossRef]

- Royalty, R.N.; Per Ring, T.M. Morphological Analysis of Damage to Tomato Leaflets by Tomato Russet Mite (Acari: Eriophyidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 1988, 81, 816–820. [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M. Population Growth of Tomato Russet Mite, Aculops Lycopersici (Acari: Eriophyidae) and Its Injury Effect on the Growth of Tomato Plants. J. Acarol. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Luigi, M.; Tiberini, A.; Taglienti, A.; Bertin, S.; Dragone, I.; Sybilska, A.; Tarchi, F.; Goggioli, D.; Lewandowski, M.; Simoni, S. Molecular Methods for the Simultaneous Detection of Tomato Fruit Blotch Virus and Identification of Tomato Russet Mite, a New Potential Virus–Vector System Threatening Solanaceous Crops Worldwide. Viruses 2024, 16, 806. [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, A.L. Aculops Lycopersici Tryon (Acari: Eriophyoidea) Monitoring, Control Options and Economic Relevance in German Tomato Cultivation. Bad Hersfeld, Deutschland, April 2023.

- Duso, C.; Castagnoli, M.; Simoni, S.; Angeli, G. The Impact of Eriophyoids on Crops: Recent Issues on Aculus schlechtendali, Calepitrimerus vitis and Aculops lycopersici. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010, 51, 151–168. [CrossRef]

- Marcic, D. Acaricides in Modern Management of Plant-Feeding Mites. J. Pest Sci. 2012, 85, 395–408. [CrossRef]

- Hessein, N.A.; Perring, T.M. Feeding Habits of the Tydeidae with Evidence of Homeopronematus Anconai (Acari: Tydeidae) Predation on Aculops lycopersici (Acari: Eriophyidae). Int. J. Acarol. 1986, 12, 215–221. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-H.; Shipp, L.; Buitenhuis, R. Predation, Development, and Oviposition by the Predatory Mite Amblyseius swirkii (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on Tomato Russet Mite (Acari: Eriophyidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2010, 103, 563–569. [CrossRef]

- van Houten, Y.; Glas, J.; Hoogerbrugge, H.; Rothe, J.; Bolckmans, K.; Simoni, S.; Van Arkel, J.; Alba, J.; Kant, M.; Sabelis, M. Herbivory-Associated Degradation of Tomato Trichomes and Its Impact on Biological Control of Aculops lycopersici. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2013, 60, 127–138. [CrossRef]

- Pijnakker, J.; Hürriyet, A.; Petit, C.; Vangansbeke, D.; Duarte, M.V.; Arijs, Y.; Moerkens, R.; Sutter, L.; Maret, D.; Wäckers, F. Evaluation of Phytoseiid and Iolinid Mites for Biological Control of the Tomato Russet Mite Aculops lycopersici (Acari: Eriophyidae). Insects 2022, 13, 1146. [CrossRef]

- Gard, B.; Bardel, A.; Douin, M.; Perrin, B.; Tixier, M.-S. Laboratory and Field Studies to Assess the Efficacy of the Predatory Mite Typhlodromus (Anthoseius) recki (Acari: Phytoseiidae) Introduced via Banker Plants to Control the Mite Pest Aculops lycopersici (Acari: Eriophyidae) on Tomato. BioControl 2024, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzazy, M.M.; Al-Rehiayani, S.M.; Abdel-Baky, N.F. Life Tables of the Predatory Mite Neoseiulus cucumeris (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on Two Pest Mites as Prey, Aculops lycopersici and Tetranychus urticae. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2018, 51, 637–648. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, F.S.; Ferreira, M.M.; Lofego, A.C. Neoseiulus tunus (De Leon, 1967)(Acari: Phytoseiidae): Is This a Potential Natural Enemy of Aculops lycopersici (Massee, 1937)(Acari: Eriophyidae)? Entomol. Commun. 2021, 3, ec03033–ec03033. [CrossRef]

- Castagnoli, M.; Simoni, S.; Liguori, M. Evaluation of Neoseiulus californicus (McGregor) (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a candidate for the control of Aculops lycopersici (Tryon) (Acari: Eriophyoidea): A preliminary study. Redia 2003, 86, 97–100.

- Trottin-Caudal, Y.; Fournier, C.; Leyre, J.M. Biological control of Aculops lycopersici (Massee) using the predatory mites Neoseiulus californicus McGregor and Neoseiulus cucumeris (Oudemans) on tomato greenhouse crops. In Colloque international tomate sous abri, protection intégrée - agriculture biologique, Avignon, France, 17-18 et 19 septembre 2003; Roche, L.; Edin, M.; Mathieu, V.; Laurens, F. Eds.; Centre de Balandran, BP 32, 30127 Bellegarde, France, 2003; pp. 153–157.

- Fischer, S.; Klötzli, F.; Falquet, L.; Celle, O. An Investigation on Biological Control of the Tomato Russet Mite Aculops lycopersici (Massee) with Amblyseius andersoni (Chant). In Proceedings of the IOBC/WPRS Working Group "Integrated Control in Protected Crops, Temperate Climate", Turku, Finland, 10-14 April, 2005; Enkegaard, A. Ed.; Finland 2005 IOBC/WPRS Bull 28:99–102.

- Aysan, E.; Nabi, A.K. Tritrophic Relationships among Tomato Cultivars, the Rust Mite, Aculops lycopersici (Massee)(Eriophyidae), and Its Predators. Acarologia 2018, 58, 5–17. 10.24349/acarologia/20184283.

- Isman, M.B.; Grieneisen, M.L. Botanical Insecticide Research: Many Publications, Limited Useful Data. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 19, 140–145. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.11.005.

- Jacobson, M. Botanical pesticides. Past, present, and future. In Insecticides of Plant Origin; Arnason, J.T., Philogène, B.J.R., Morand, P., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/ doi/pdf/10.1021/bk-1989-0387.ch001.

- Regnault-Roger, C.; Vincent, C.; Arnason, J.T. Essential Oils in Insect Control: Low-Risk Products in a High-Stakes World. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012, 57, 405–424. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, R.; Ragusa, E.; Benelli, G.; Lo Verde, G.; Zeni, V.; Maggi, F.; Petrelli, R.; Spinozzi, E.; Ferrati, M.; Sinacori, M. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Carlina Oxide on Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) and Neoseiulus californicus (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 80, 967–977. [CrossRef]

- Marčić, D.; Döker, I.; Tsolakis, H. Bioacaricides in Crop Protection—What Is the State of Play? Insects 2025, 16, 95. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-L.; Tak, J.-H. Chapter 6—Essential oils for arthropod pest management in agricultural production systems. In Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor and Safety, 1st ed.; Preedy, V.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 61–70. [CrossRef]

- Koul, O.; Walia, S.; Dhaliwal, G. Essential Oils as Green Pesticides: Potential and Constraints. Biopestic. Int 2008, 4, 63–84.

- Tsolakis, H.; Ragusa Di Chiara, S. Laboratory Evaluation of the Effect of Plant Extracts on Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acariformes, Tetranychidae). In Acarina biodiversity in the natural and human sphere; Luxograph, 2004; pp. 539–548.

- Greco, C.; Comparetti, A.; Fascella, G.; Febo, P.; La Placa, G.; Saiano, F.; Mammano, M.M.; Orlando, S.; Laudicina, V.A. Effects of Vermicompost, Compost and Digestate as Commercial Alternative Peat-Based Substrates on Qualitative Parameters of Salvia officinalis. Agronomy 2021, 11, 98. [CrossRef]

- Hardman, J.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Moreau, D.L.; Bostanian, N.J. An Index for Selective Toxicity of Miticides to Phytophagous Mites and Their Predators Based on Orchard Trials. Pest Manag. Sci. Former. Pestic. Sci. 2003, 59, 1321–1332. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Berkay Yılmaz, Y.; Antika, G.; Salehi, B.; Tumer, T.B.; Kulandaisamy Venil, C.; Das, G.; Patra, J.K.; Karazhan, N.; Akram, M. Phytochemical Constituents, Biological Activities, and Health-promoting Effects of the Genus Origanum. Phytother. Res. 2020, 35, 95–121. [CrossRef]

- Lombrea, A.; Antal, D.; Ardelean, F.; Avram, S.; Pavel, I.Z.; Vlaia, L.; Mut, A.-M.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Dehelean, C.A.; Soica, C. A Recent Insight Regarding the Phytochemistry and Bioactivity of Origanum vulgare L. Essential Oil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9653. [CrossRef]

- Cousyn, G.; Dalfrà, S.; Scarpa, B.; Geelen, J.; Anton, R.; Serafini, M.; Delmulle, L. Harmonizing the Use of Plants in Food Supplements in the European Union: Belgium, France and Italy-a First Step. Eur. Food Feed Law Rev. 2013, 3, 187–196.

- Orhan, F.; Ölmez, M. Effect of Herbal Mixture Supplementation to Fish Oiled Layer Diets on Lipid Oxidation of Egg Yolk, Hen Performance and Egg Quality. Ank. Üniversitesi Vet. Fakültesi Derg. 2011, 58, 33–39. [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.; Greco, G.; Salsi, G.; Garofalo, G.; Gaglio, R.; Barbera, M.; Greco, C.; Orlando, S.; Fascella, G.; Mammano, M.M. Effect of the Gellan-Based Edible Coating Enriched with Oregano Essential Oil on the Preservation of the ‘Tardivo Di Ciaculli’Mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco Cv. Tardivo Di Ciaculli). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1334030. [CrossRef]

- Cetin, H.; Cilek, J.E.; Aydin, L.; Yanikoglu, A. Acaricidal Effects of the Essential Oil of Origanum minutiflorum (Lamiaceae) against Rhipicephalus turanicus (Acari: Ixodidae). Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 160, 359–361. [CrossRef]

- Dolan, M.C.; Jordan, R.A.; Schulze, T.L.; Schulze, C.J.; Cornell Manning, M.; Ruffolo, D.; Schmidt, J.P.; Piesman, J.; Karchesy, J.J. Ability of Two Natural Products, Nootkatone and Carvacrol, to Suppress Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) in a Lyme Disease Endemic Area of New Jersey. J. Econ. Entomol. 2009, 102, 2316–2324. [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Gross, A.D.; Dolan, M.C.; Coats, J.R. The Phenolic Monoterpenoid Carvacrol Inhibits the Binding of Nicotine to the Housefly Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 69, 775–780. [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B. Plant Essential Oils for Pest and Disease Management. Crop Prot. 2000, 19, 603–608. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, E.; Batool, R.; Akhtar, W.; Shahzad, T.; Malik, A.; Shah, M.A.; Iqbal, S.; Rauf, A.; Zengin, G.; Bouyahya, A. Rosemary Species: A Review of Phytochemicals, Bioactivities and Industrial Applications. South Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 151, 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Wanna, R.; Bozdoğan, H. Activity of Rosmarinus officinalis (Lamiales: Lamiaceae) Essential Oil and Its Main Constituent, 1, 8-Cineole, against Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Entomol. Sci. 2025, 60, 86–106.

- Napoli, E.M.; Curcuruto, G.; Ruberto, G. Screening of the Essential Oil Composition of Wild Sicilian Rosemary. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 659–670. [CrossRef]

- Allenspach, M.; Steuer, C. α-Pinene: A Never-Ending Story. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112857. [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.; Rogalska, J.; Wyszkowska, J.; Stankiewicz, M. Molecular Targets for Components of Essential Oils in the Insect Nervous System—a Review. Molecules 2017, 23, 34. [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological Effects of Essential Oils–a Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [CrossRef]

- Dunan, L.; Malanga, T.; Benhamou, S.; Papaiconomou, N.; Desneux, N.; Lavoir, A.-V.; Michel, T. Effects of Essential Oil-Based Formulation on Biopesticide Activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 202, 117006. [CrossRef]

- Pierozan, M.K.; Pauletti, G.F.; Rota, L.; Santos, A.C.A. dos; Lerin, L.A.; Di Luccio, M.; Mossi, A.J.; Atti-Serafini, L.; Cansian, R.L.; Oliveira, J.V. Chemical Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils of Salvia L. Species. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 29, 764–770. [CrossRef]

- Delamare, A.P.L.; Moschen-Pistorello, I.T.; Artico, L.; Atti-Serafini, L.; Echeverrigaray, S. Antibacterial Activity of the Essential Oils of Salvia officinalis L. and Salvia triloba L. Cultivated in South Brazil. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 603–608. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.A.; Coats, J.R. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition by Nootkatone and Carvacrol in Arthropods. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 102, 124–128. [CrossRef]

- Rguez, S.; Daami-Remadi, M.; Cheib, I.; Laarif, A.; Hamrouni, I. Composition Chimique, Activité Antifongique et Activité Insecticide de l’huile Essentielle de Salvia officinalis. Tunis J Med Plants Nat Prod 2013, 9, 65–76.

- Aissaoui, A.B.; Zantar, S.; Elamrani, A. Chemical Composition and Potential Acaricide of Salvia officinalis and Eucalyptus globulus on Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acarina: Tetranychidae). J. Appl. Chem. Environ. Prot. 2019, 4, 1–15.

- Chandler, D.; Bailey, A.S.; Tatchell, G.M.; Davidson, G.; Greaves, J.; Grant, W.P. The Development, Regulation and Use of Biopesticides for Integrated Pest Management. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 1987–1998. [CrossRef]

- Chiasson, H.; Bélanger, A.; Bostanian, N.; Vincent, C.; Poliquin, A. Acaricidal Properties of Artemisia absinthium and Tanacetum vulgare (Asteraceae) Essential Oils Obtained by Three Methods of Extraction. J. Econ. Entomol. 2001, 94, 167–171. [CrossRef]

- Laborda, R.; Manzano, I.; Gamon, M.; Gavidia, I.; Perez-Bermudez, P.; Boluda, R. Effects of Rosmarinus officinalis and Salvia officinalis Essential Oils on Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 48, 106–110. [CrossRef]

- da Camara, C.A.; Akhtar, Y.; Isman, M.B.; Seffrin, R.C.; Born, F.S. Repellent Activity of Essential Oils from Two Species of Citrus against Tetranychus urticae in the Laboratory and Greenhouse. Crop Prot. 2015, 74, 110–115. [CrossRef]

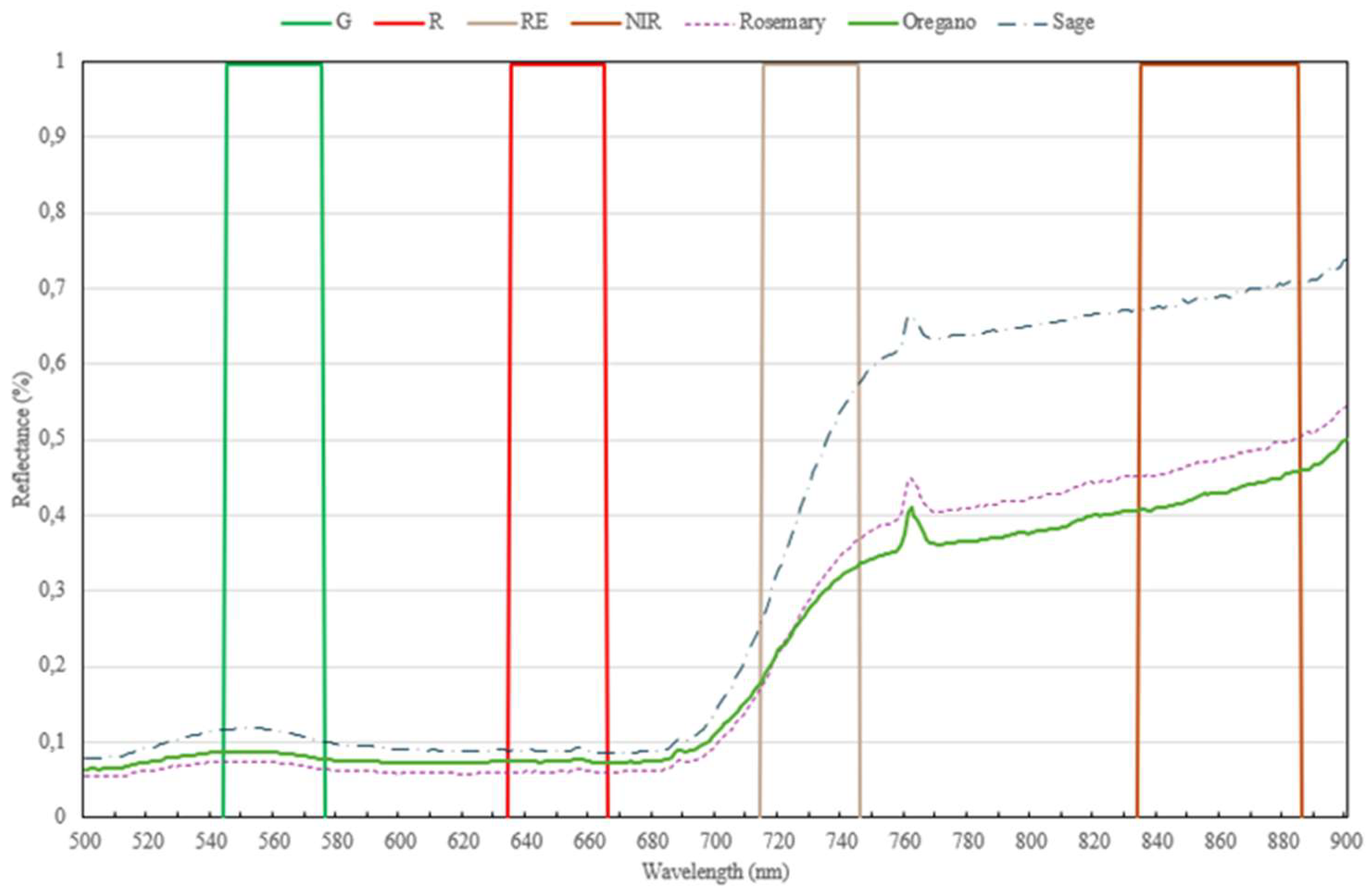

- Greco, C.; Catania, P.; Orlando, S.; Vallone, M.; Mammano, M.M. Assessment of Vegetation Indices as Tool to Decision Support System for Aromatic Crops.; Springer, 2024; pp. 322–331.

- Greco, C.; Gaglio, R.; Settanni, L.; Sciurba, L.; Ciulla, S.; Orlando, S.; Mammano, M.M. Smart Farming Technologies for Sustainable Agriculture: A Case Study of a Mediterranean Aromatic Farm. 2025.

- Greco, C.; Catania, P.; Orlando, S.; Calderone, G.; Mammano, M.M. Rosemary Biomass Estimation from UAV Multispectral Camera. In Biosystems Engineering Promoting Resilience to Climate Change - AIIA 2024 - Mid Term.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer Cham, 2025; Vol. 586.

- Garofalo, G.; Ponte, M.; Greco, C.; Barbera, M.; Mammano, M.M.; Fascella, G.; Greco, G.; Salsi, G.; Orlando, S.; Alfonzo, A. Improvement of Fresh Ovine “Tuma” Cheese Quality Characteristics by Application of Oregano Essential Oils. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1293. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography /Mass Spectrometry, ed. 4.1. 2017. Available online: http://essentialoilcomponentsbygcms.com/ (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- Zito, P.; Sajeva, M.; Bruno, M.; Rosselli, S.; Maggio, A.; Senatore, F. Essential Oils Composition of Two Sicilian Cultivars of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill.(Cactaceae) Fruits (Prickly Pear). Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 1305–1314. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1987, 3, 302–303.

- Johnson, N.; Kotz, S. Discrete Distributions. Their Distributions in Statistics. 1969, Boston, Houghton Mifflin. xvi, 328 p.

| Component/Chemical Class |

Oregano EO (RW%) |

Rosemary EO (RW%) |

Sage EO (RW%) |

| Monoterpene phenol | |||

| Carvacrol | 83.42 | - | - |

| Thymol | 0.89 | - | - |

| Subtotal | 84.31 | - | - |

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons | |||

| ρ-Cymene | 3.06 | 0.80 | - |

| γ-Terpinene | 2.93 | 2.10 | - |

| β-Myrcene | 1.01 | 1.21 | 2.19 |

| α-Terpinene | 0.99 | 0.45 | - |

| Limonene | 0.45 | 2.22 | - |

| Terpinolene | 0.41 | 0.53 | - |

| β-Ocimene | 0.42 | - | - |

| β-Pinene | 0.13 | 4.1 | 2.66 |

| Sabinene | 0.13 | - | - |

| α-Pinene | - | 28.0 | 2.66 |

| Linalyl Acetate | - | 1.12 | - |

| Crisantenone | - | - | 12.87 |

| Camphene | - | 7.00 | 9.26 |

| Subtotal | 9.53 | 47.53 | 29.64 |

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | |||

| Linalool | 0.32 | 3.45 | - |

| Camphor | 0.27 | 6.20 | 21.91 |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 0.18 | - | - |

| 1,8-Cineole (Eucalyptol) | - | 11.00 | 27.67 |

| Borneol | - | 7.72 | 2.59 |

| β-Thujone | - | 0.73 | - |

| α-Thujone | - | - | 5.32 |

| Bornyl Acetate | - | - | 1.45 |

| 4-Caranol | - | - | 0.09 |

| 4-Terpineol | 0.31 | - | 0.54 |

| α-Terpineol | - | 4.40 | - |

| α-Thujene | 0.23 | - | - |

| α-Phellandrene | 0.60 | - | - |

| Subtotal | 1.91 | 33.37 | 59.57 |

| Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | |||

| β-Caryophyllene | 1.07 | 6.64 | 1.46 |

| α-Humulene | 0.70 | 0.75 | - |

| Germacrene | 0.07 | - | - |

| β-Bisabolene | 0.63 | - | - |

| Farnesene | 0.40 | - | - |

| α-Caryophyllene | - | - | 0.89 |

| Alloaromadendrene | - | - | 0.24 |

| α-Gurjunene | - | - | 0.13 |

| Carophyllene oxide | 0.88 | ||

| Subtotal | 2.87 | 8.27 | 2.72 |

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | |||

| Viridiflor | - | - | 1.22 |

| Palustrol | - | - | 0.75 |

| Ledol | - | - | 0.53 |

| Spathulenol | - | - | 0.31 |

| Subtotal | - | - | 2.81 |

| Other compounds | |||

| Camphol | 0.70 | - | - |

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 0.49 | - | - |

| 3-Octanone | 0.36 | - | - |

| Carvacrol Methyl Ether | 0.03 | - | - |

| Maool | - | - | 0.62 |

| Diethyl Phthalate | - | - | 0.53 |

| Naphthalene | - | - | 0.28 |

| Subtotal | 1.58 | - | 1.43 |

| Concentrations |

Cumulative mortality (%) (mean ± SE) |

Survival time (days) | Abbott’s corrected mortality | Toxicity class | ||||

| Plant extracts | (µL L-1) | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | (mean ± SE) | (%) | * |

| O. vulgare | 5000 | 66.00 ± 7.92 | 74.00 ± 8.46 | 80.00 ± 7.30 | 90.00 ± 4.47 a | 0.90 ± 0.203 a | 89.13 | 4 |

| 2500 | 14.00 ± 4.27 | 20.00 ± 2.98 | 34.00 ± 6.00 | 36.00 ± 7.77 bc | 2.96 ± 0.216 bcd | 30.43 | 2 | |

| 1280 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 4.00 ± 2.67 | 12.00 ± 4.42 | 22.00 ± 5.54 efg | 3.62 ± 0.114 ed | 15.22 | 1 | |

| 640 | 2.00 ± 2.00 | 4.00 ± 2.67 | 12.00 ± 3.27 | 20.00 ± 5.16 ef | 3.62 ± 0.124 ed | 13.04 | 1 | |

| 320 | 2.00 ± 2.00 | 6.00 ± 3.06 | 10.00 ± 3.33 | 16.00 ± 4.00 efg | 3.66 ± 0.127 ed | 8.70 | 1 | |

| Control | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 8.00 ± 3.27 fg | 3.92 ± 0.038 e | 0.00 | - | |

| S. rosmarinus | 5000 | 16.00 ± 6.53 | 36.00 ± 9.33 | 42.00 ± 9.17 | 46.00±10.3 b | 2.60 ± 0.234 b | 46.00 | 2 |

| 2500 | 12.00 ± 4.42 | 24.00 ± 4.99 | 34.00 ± 4.27 | 40.00±5.16 bc | 2.90 ± 0.214 bcd | 40.00 | 2 | |

| 1280 | 2.00 ± 2.00 | 12.00 ± 4.42 | 20.00 ± 5.16 | 26.00±3.06 de | 3.40 ± 0.159 cde | 26.00 | 2 | |

| 640 | 2.00 ± 2.00 | 16.00 ± 4.99 | 16.00 ± 4.99 | 22.00±6.96 e | 3.44 ± 0.165 cde | 22.00 | 1 | |

| 320 | 4.00 ± 2.67 | 6.00 ± 3.06 | 6.00 ± 3.06 | 12.00±4.42 efg | 3.72 ± 0.128 cd | 12.00 | 1 | |

| Control | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00±0.00 g | 4.00 ± 0.00 e | 0.00 | - | |

| S. officinalis | 5000 | 12.00 ± 5.33 | 32.00 ± 9.52 | 42.00 ± 9.17 | 42.00 ± 9.17 bc | 2.72 ± 0.225 bc | 39.58 | 2 |

| 2500 | 12.00 ± 6.80 | 32.00 ± 6.80 | 40.00 ± 7.30 | 54.00 ± 8.46 b | 2.62 ± 0.216 bc | 52.08 | 3 | |

| 1280 | 10.00 ± 4.47 | 28.00 ± 6.11 | 32.00 ± 8.00 | 34.00 ± 6.70 bcd | 2.96 ± 0.218 bcd | 31.25 | 2 | |

| 640 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 14.00 ± 4.27 | 22.00 ± 5.54 | 22.00 ± 5.54 cde | 3.42 ± 0.159 cde | 18.75 | 1 | |

| 320 | 4.00 ± 2.67 | 16.00 ± 4.00 | 18.00 ± 4.67 | 28.00±3.27 bcde | 3.34 ± 0.173 bcde | 25.00 | 1 | |

| Control | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 4.00±2.67 e | 3.96 ± 0.028 e | 0.00 | - | |

| Essential oils | LC10 µL L-1 (95% CI) |

LC30 µL L-1 (95% CI) |

LC50 µL L-1 (95% CI) |

LC90 µL L-1 (95% CI) |

LC95 µL L-1 (95% CI) |

Intercept ± SE | Slope ± SE | Goodness of fit χ2 (d.f.) |

| Origanum vulgare | 369.33 (208.57-530.18) |

1,068.17 (799.56-1362.01) |

2,228.90 (1740.28-3050.91) |

13,451.79 (8015.49-31804.60) |

22,391.85 (12084.54-63217.89) |

-5.49 ± 0.71 | 1.64 ± 0.22 | 21.62 (3) p = 0.000 |

| Salvia rosmarinus | 207.16 (33.57-428.25) |

1,488.81 (907.55-2451.9) |

5,835.39 (3281-22288.8) |

164,369.0 (35154.4-10573529.9) |

423,447.9 (67507.2-61877106.9) |

-3.32 ± 0.67 | 0.88 ± 0.21 | 0.53 (3) p = 0.911 |

| Salvia officinalis | 26.62 (0.002-146.38) |

654.53 (80.06-1292.05) |

6,013.81 (2630.4-261607.4) |

1,358,595.0 (74342.1-20,379,803,862,870.6) |

6,315,387.0 (184,714.1-3,651,741,272,548,380.0) |

-2.05 ± 0.61 | 0.54 ± 0.19 | 5.73 (3) p = 0.125 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).