Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

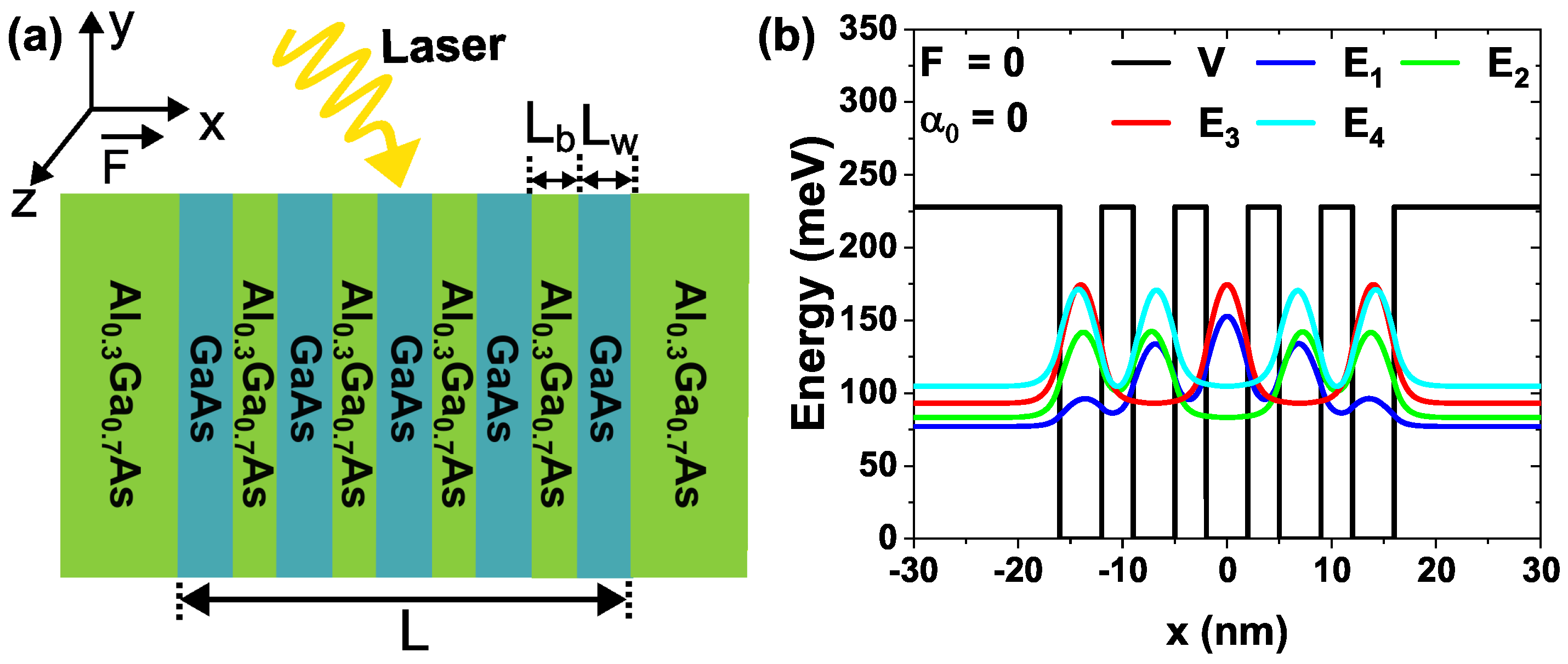

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Laser Dressed Potential Energy

2.2. Nonlinear Optical Response

3. System and Parameters

4. Results and Discussion

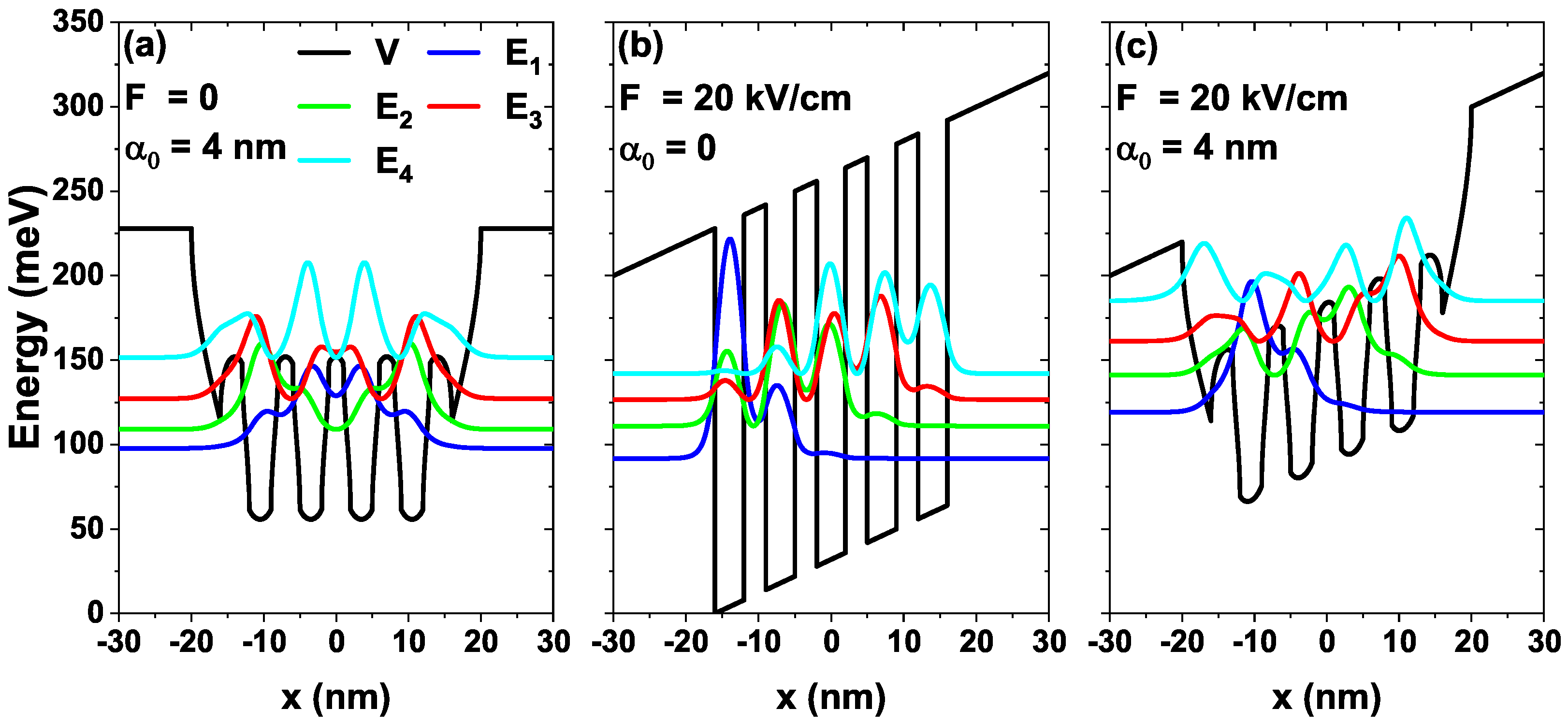

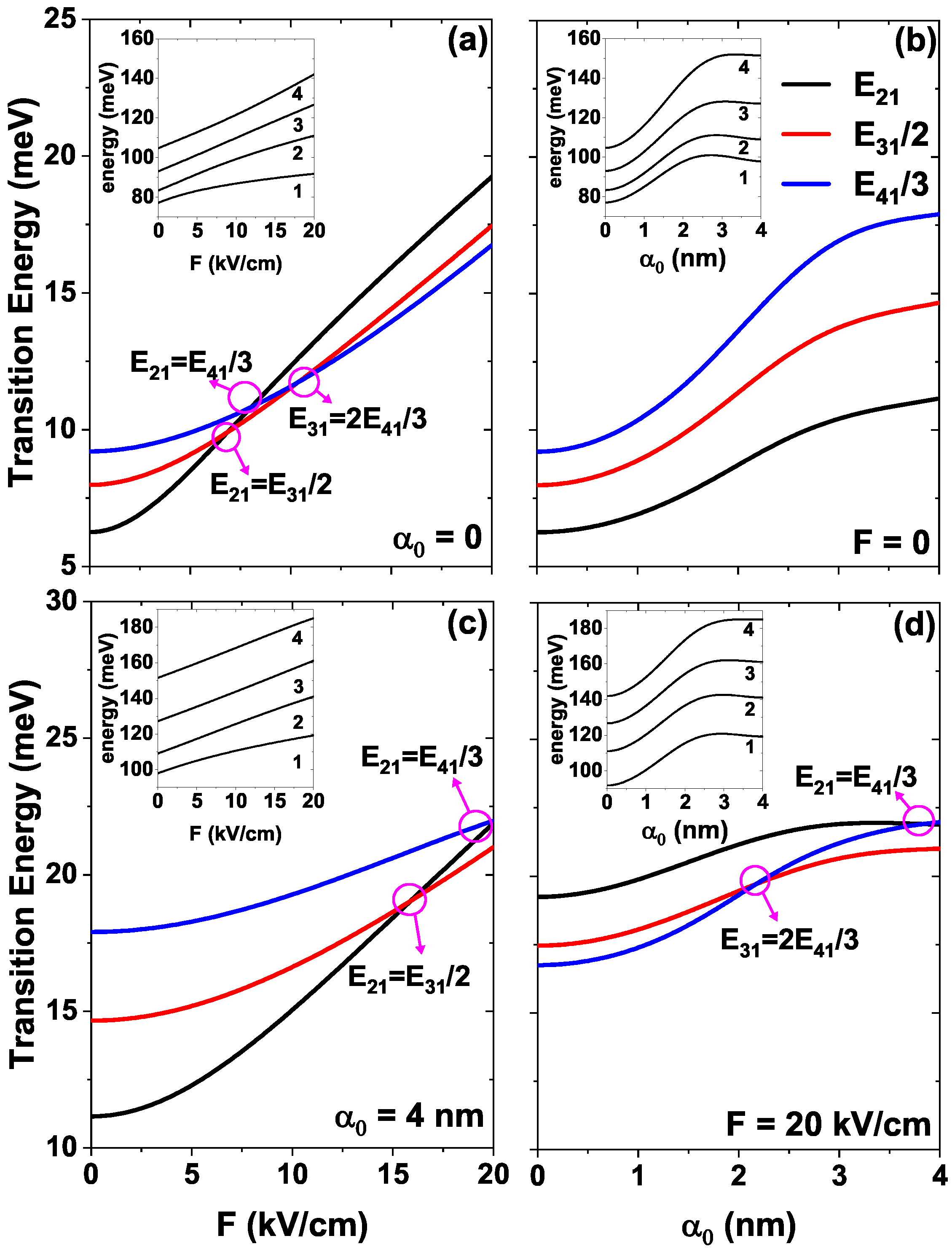

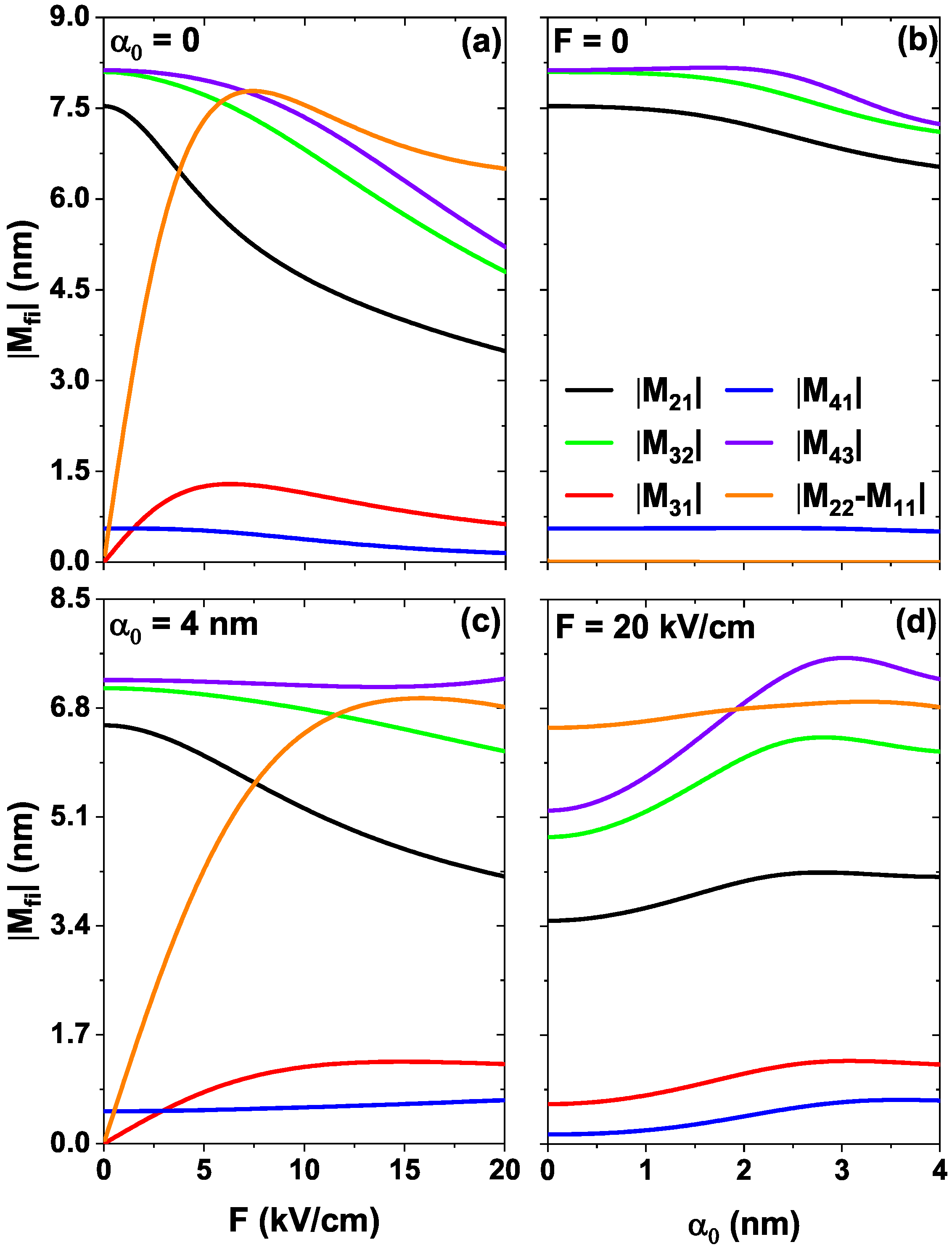

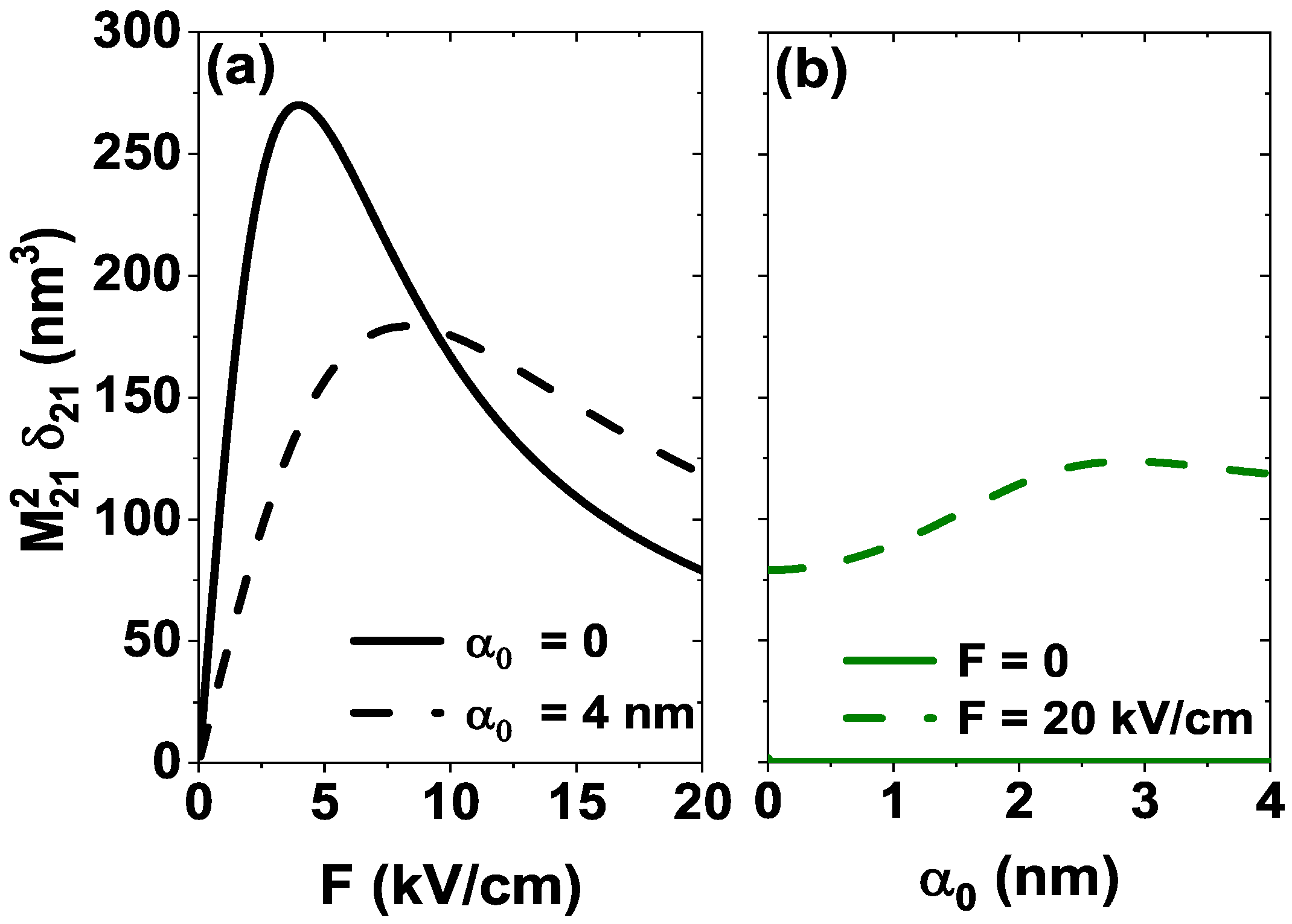

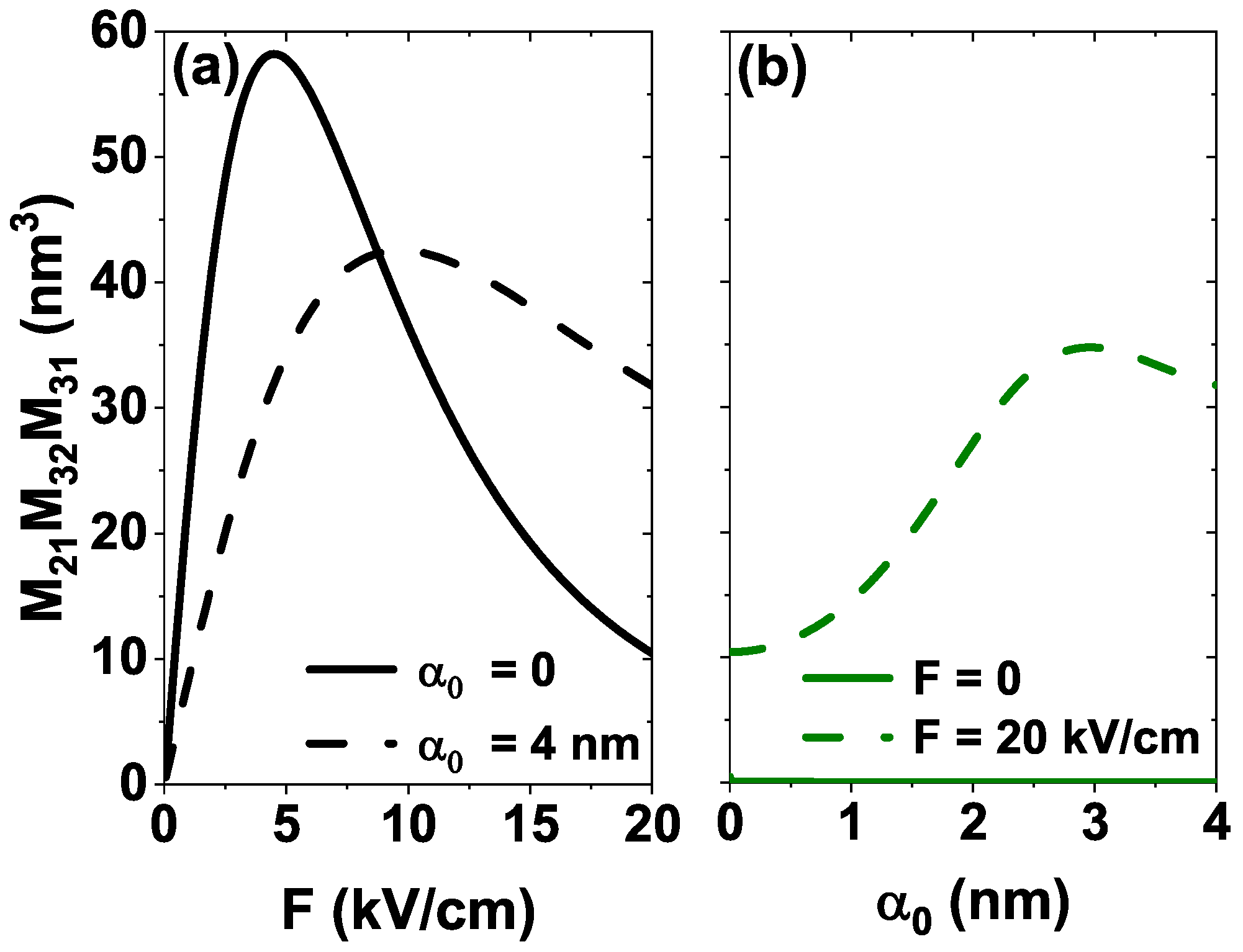

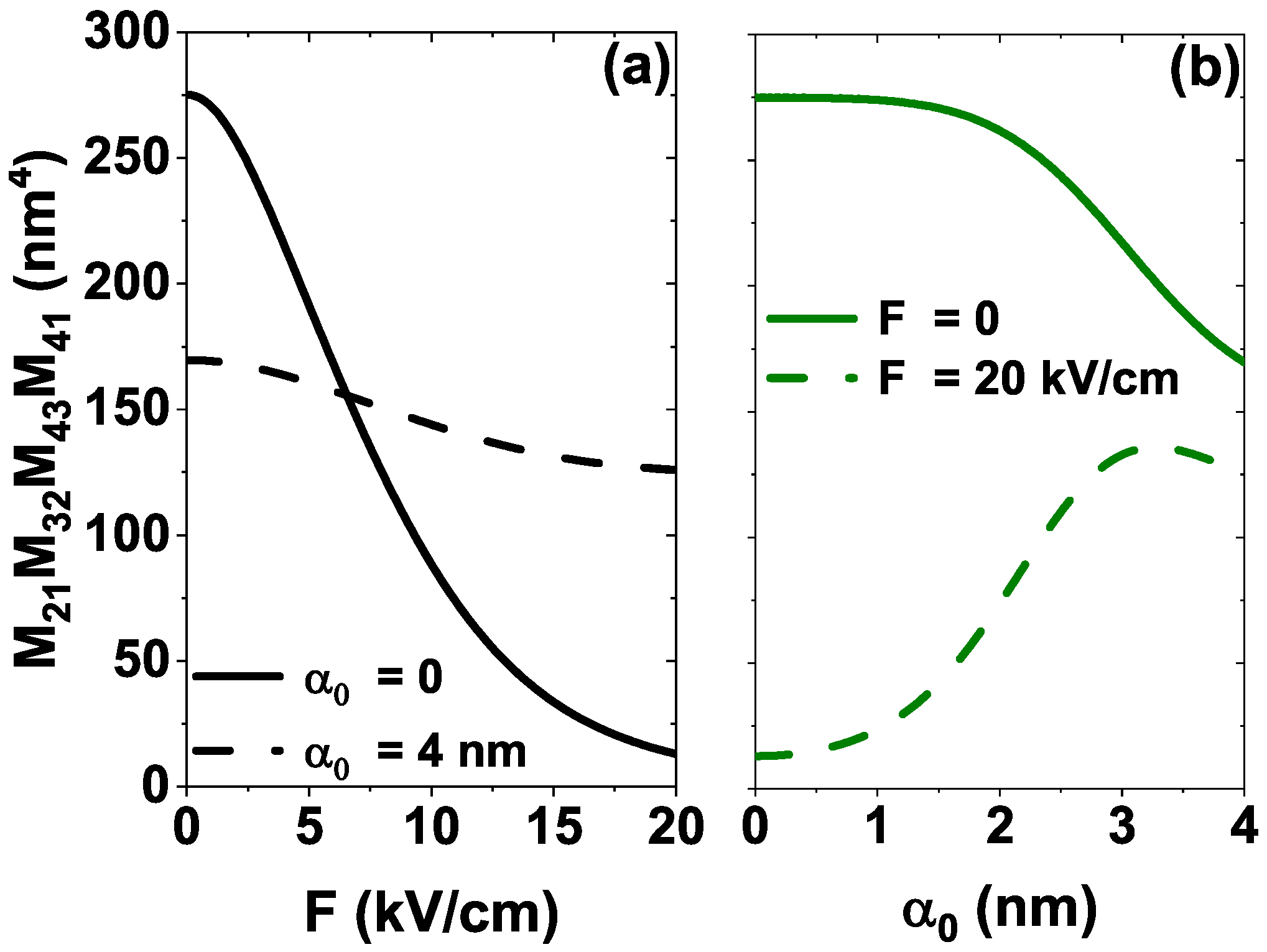

4.1. Influence of the External Fields on the DMMEs and the ISBT

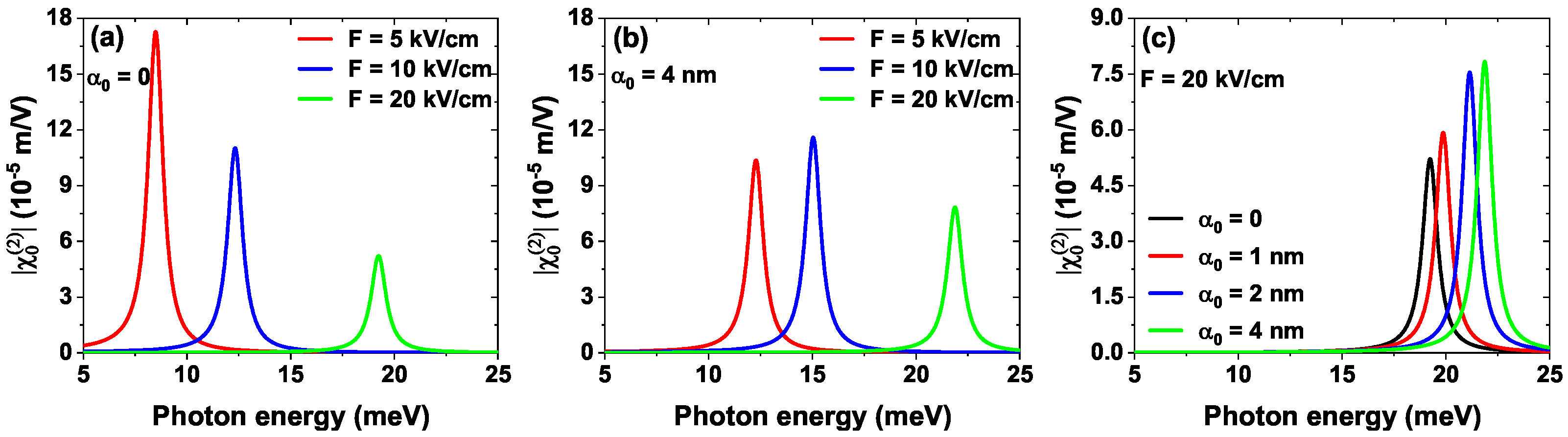

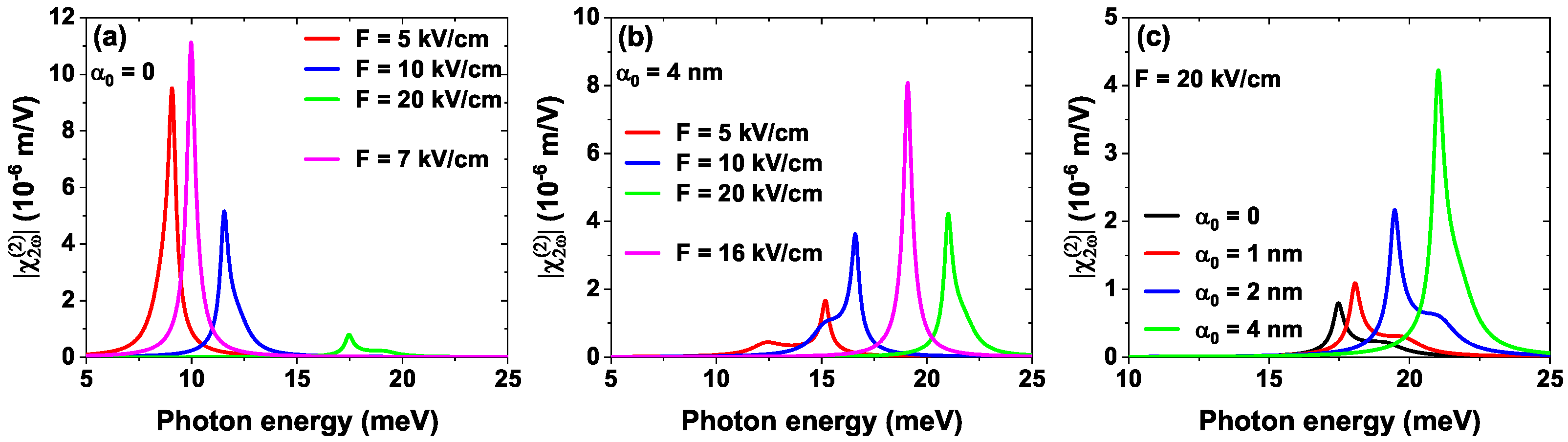

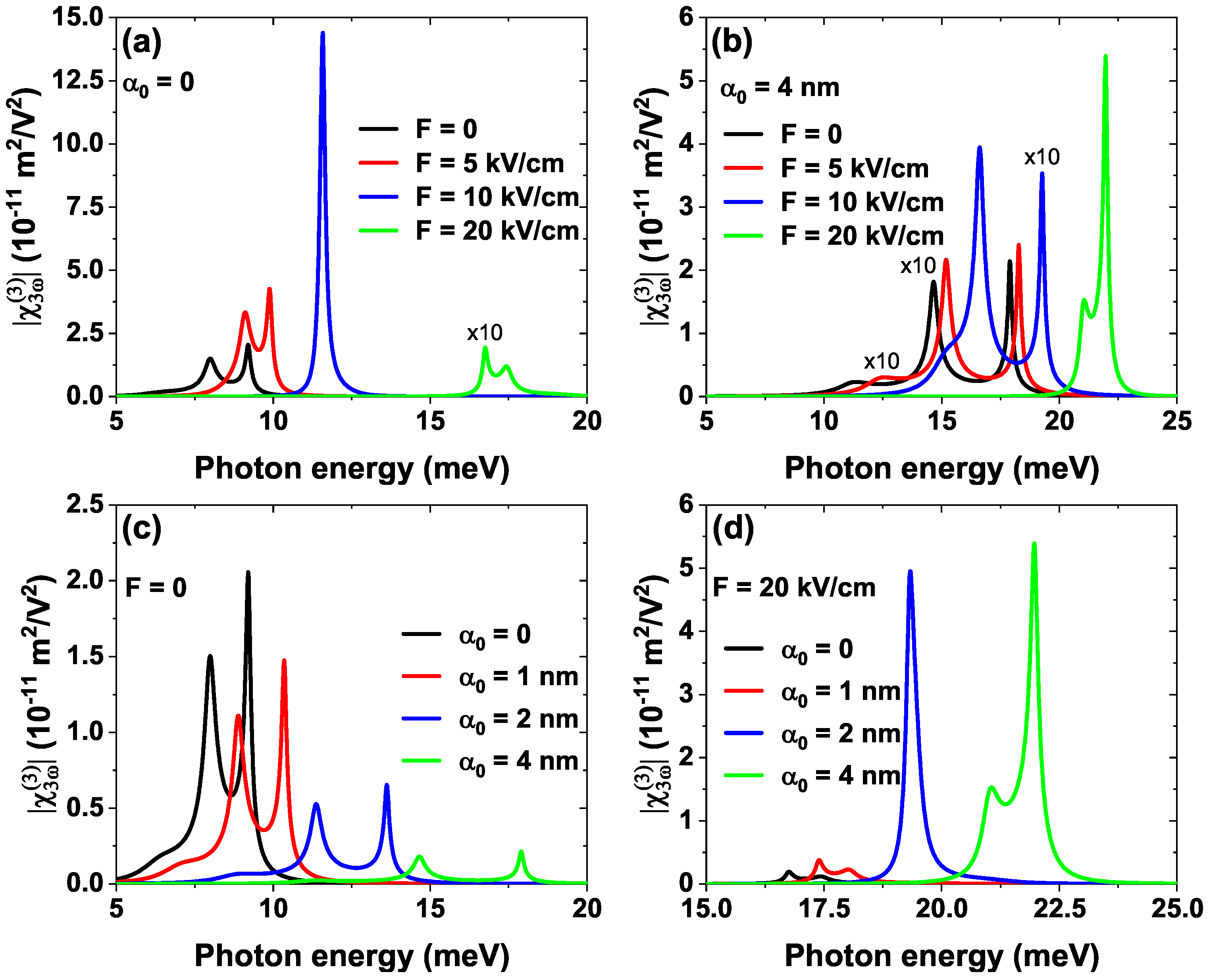

4.2. External Fields Control Nonlinear optical response

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Solaimani, M.; Morteza, I.; Arabshahi, H.; Reza, S. M. Study of optical non-linear properties of a constant total effective length multiple quantum wells system. J. Lumin. 2013, 134, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilgul, U.; Ungan, F.; Kasapoglu, E.; Sari, H. ; Sökmen, I. Linear and nonlinear optical properties in asymmetric double semi-V-shaped quantum well. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2015, 475, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Aqiqi, S.; You, J.-F.; Kria, M.; Guo, K.-X.; Feddi, E.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Yuan, J.-H. Influence of position-dependent effective mass on the nonlinear optical properties in AlxGa1-xAs/GaAs single and double triangular quantum wells. Phys. E: Low- Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2020, 115, 113707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, N. D. Linear and nonlinear optical properties in quantum wells. Micro and Nanostructures 2022, 170, 207372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, D.; Ozturk, O.; Alaydin, B. O.; Ozturk, E. Linear and nonlinear optical properties of a superlattice with periodically increased well width under electric and magnetic fields. Micro and Nanostructures 2022, 166, 207225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Hazra, R.; Borgohain, N. Controlling behavior of transparency and absorption in three-coupled multiple quantum wells via spontaneously generated coherence. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Corrales, J. A.; Morales, A. L.; Behiye Yücel, M.; Kasapoglu, E.; Duque, C. A. Electronic Transport Properties in GaAs/AlGaAs and InSe/InP Finite Superlattices under the Effect of a Non-Resonant Intense Laser Field and Considering Geometric Modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Magdaleno, K. A.; Demir, M.; Ungan, F.; Nava-Maldonado, F. M.; Martínez-Orozco, J. C. Third harmonic generation of a 12–6 GaAs/Ga 1-xAlxAs double quantum well: effect of external fields. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasapoglu, E.; Sari, H.; Sökmen, I.; Vinasco, J. A.; Laroze, D.; Duque, C. A. Effects of intense laser field and position dependent effective mass in Razavy quantum wells and quantum dots. Physica E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2021, 126, 114461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzemen, A. T.; Dakhlaoui, H.; Mora-Ramos, M. E.; Ungan, F. The nonlinear optical properties of GaAs/GaAlAs triple quantum well: role of the electromagnetic fields and structural parameters. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2022, 646, 414286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosencher, E.; Bois, P.; Nagle, J.; Costard, E.; Delaitre, S. Observation of nonlinear optical rectification at 10.6 μm in compositionally asymmetrical AlGaAs multiquantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1989, 55, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, A.; Tomassini, N.; Ferrari, L.; Righini, M.; Selci, S.; Bruni, M.R.; Schiumarini, D.; Simeone, M.G. Second harmonic generation in stepped InAsGaAs/GaAs quantum wells. Phys. Status Solidi A 1997, 164, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirtori, C.; Capasso, F.; Sivco, D. L.; Cho, A. Y. Giant, triply resonant, third-order nonlinear susceptibility χ3ω(3) in coupled quantum wells. PRL 1992, 68, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ido, T.; Tanaka, S. , Suzuki, M.; Koizumi, M.; Sano, H.; Inoue, H. Ultra-high-speed multiple-quantum-well electro-absorption optical modulators with integrated waveguides. J. Lightwave Technol. 1996, 14, 2026–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. A.; Chemla, D. S.; Damen, T. C.; Gossard, A. C.; Wiegmann, W.; Wood, T. H.; Burrus, C. A. Band-edge electroabsorption in quantum well structures: The quantum-confined Stark effect. PRL 1984, 53, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Corrales, J. A.; Dagua-Conda, C. A.; Mora-Ramos, M. E.; Morales, A. L.; Duque, C. A. Shape and size effects on electronic thermodynamics in nanoscopic quantum dots. Physica E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2025, 170, 116228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazeki, Y.; Yokohashi, H.; Kodama, S.; Murata, H.; Arakawa, T. InGaAs/InAlAs multiple-quantum-well optical modulator integrated with a planar antenna for a millimeter-wave radio-over-fiber system. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 11583–11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ni, S.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Yuan, J.; Li, D.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. AlInGaAs multiple quantum well-integrated device with multifunction light emission/detection and electro-optic modulation in the near-infrared range. ACS omega 2021, 6, 8687–8692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, M. M. K.; Emami, F. Optimized design and simulation of optical section in electro-reflective modulators based on photonic crystals integrated with multi-quantum-well structures. Optics 2023, 4, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, N. K.; Wang, Q. Semiconductor optical amplifiers. World Scientific, 2006.

- Panchadhyayee, P.; Dutta, B. K. Spatially structured multi-wave-mixing induced nonlinear absorption and gain in a semiconductor quantum well. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Ramos, M. E.; Duque, C. A.; Kasapoglu, E.; Sari, H.; Sökmen, I. Electron-related nonlinearities in GaAs–Ga1-xAlxAs double quantum wells under the effects of intense laser field and applied electric field. J. Lumin. 2013, 135, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilgul, U.; Al, E.B.; Martínez-Orozco, J. C.; Restrepo, R.L. Mora-Ramos, M. E. Duque, C. A.; Ungan, F.; Kasapoglu, E. Linear and nonlinear optical properties in an asymmetric double quantum well under intense laser field: effects of applied electric and magnetic fields. Opt. Mater. 2016, 58, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, R. L.; González-Pereira, J. P.; Kasapoglu, E.; Morales, A. L.; Duque, C. A. Linear and nonlinear optical properties in the terahertz regime for multiple-step quantum wells under intense laser field: Electric and magnetic field effects. Opt. Mater. 2018, 86, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, M. K.; Rodríguez-Magdaleno, K. A.; Martinez-Orozco, J. C.; Mora-Ramos, M. E.; Ungan, F. Optical properties of a triple AlGaAs/GaAs quantum well purported for quantum cascade laser active region. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, O.; Alaydin, B. O.; Altun, D.; Ozturk, E. Intense laser field effect on the nonlinear optical properties of triple quantum wells consisting of parabolic and inverse-parabolic quantum wells. Laser Phys. 2022, 32, 035404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaydin, B. O.; Altun, D.; Ozturk, O.; Ozturk, E. High harmonic generations triggered by the intense laser field in GaAs/AlxGa1-xAs honeycomb quantum well wires. Mater. Today Phys. 2023, 38, 101232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. A.; Chemla, D. S.; Damen, T. C.; Gossard, A. C.; Wiegmann, W.; Wood, T. H.; Burrus, C. A. Electric field dependence of optical absorption near the band gap of quantum-well structures. Phys. Rev. B 1985, 32, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasapoglu, E.; Yücel, M. B.; Duque, C. A. Harmonic-gaussian symmetric and asymmetric double quantum wells: magnetic field effects. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, E.; Sari, H.; Sokmen, I. Electric field and intense laser field effects on the intersubband optical absorption in a graded quantum well. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2005, 38, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungan, F.; Yesilgul, U.; Sakiroglu, S.; Mora-Ramos, M.E.; Duque, C.A.; Kasapoglu, E.; Sari, H.; Sökmen, I. Simultaneous effects of hydrostatic pressure and temperature on the nonlinear optical properties in a parabolic quantum well under the intense laser field. Opt. Commun. 2013, 309, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungan, F.; Restrepo, R. L.; Mora-Ramos, M. E.; Morales, A. L.; Duque, C. A. Intersubband optical absorption coefficients and refractive index changes in a graded quantum well under intense laser field: effects of hydrostatic pressure, temperature and electric field. Semicond. 2014, 434, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-Dahmouny, A.; Sali, A.; Es-Sbai, N.; Arraoui, R.; Jaouane, M.; Fakkahi, A.; El-Bakkari, K.; Duque, C. A. Combined effects of hydrostatic pressure and electric field on the donor binding energy, polarizability, and photoionization cross-section in double GaAs/Ga1-xAlxAs quantum dots. EPJ B 2022, 95, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barseghyan, M.G.; Hakimyfard, A.; López, S.Y.; Duque, C.A.; Kirakosyan, A.A. Simultaneous effects of hydrostatic pressure and temperature on donor binding energy and photoionization cross section in Pöschl–Teller quantum well. Physica E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2010, 42, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilgul, U.; Al, E.B.; Martínez-Orozco, J. C. Restrepo, R.L. Mora-Ramos, M. E. Duque, C. A. Ungan, F. and Kasapoglu, E. Linear and nonlinear optical properties in an asymmetric double quantum well under intense laser field: effects of applied electric and magnetic fields. Opt. Mater. 2016, 58, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Guo, K.; Liu, G.; He, X.; Lan, J.; Zhou, Z. Exciton effect on the linear and nonlinear optical absorption coefficients and refractive index changes in Morse quantum wells with an external electric field. Thin Solid Films 2020, 710, 138286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Störmer, H. L.; Gossard, A. C.; Wiegmann, W. Observation of intersubband scattering in a 2-dimensional electron system. Solid State Commun. 1982, 41, 707–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqiqi, S.; Duque, C. A.; Radu, A.; Gil-Corrales, J. A.; Morales, A. L.; Vinasco, J. A.; Laroze, D. Optical properties and conductivity of biased GaAs quantum dots. Physica E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2022, 138, 115084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrod, D.; Auyang, S. Y.; Wolff, P. A.; Sugimoto, M. Observation of third order optical nonlinearity due to intersubband transitions in AlGaAs/GaAs superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1991, 59, 2932–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiri, N.; Sfina, N.; Nasrallah, S. A. B.; Lazzari, J. L.; Said, M. Intersubband transitions in quantum well mid-infrared photodetectors. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2013, 60, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagua-Conda, C. A.; Gil-Corrales, J. A.; Hahn, R. V. H.; Restrepo, R. L.; Mora-Ramos, M. E.; Morales, A. L.; Duque, C. A. Tuning Electromagnetically Induced Transparency in a Double GaAs/AlGaAs Quantum Well with Modulated Doping. Crystals 2025, 15, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yu, J.; Boehm, G.; Belkin, M. A.; Lee, J. Electrically tunable third-harmonic generation using intersubband polaritonic metasurfaces. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigand, H.; Vogler-Neuling, V. V.; Escalé, M. R.; Pohl, D.; Richter, F. U.; Karvounis, A.; Timpu, F.; Grange, R. Enhanced electro-optic modulation in resonant metasurfaces of lithium niobate. ACS Photonics 2021, 8, 3004–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Cen, Q.; Ding, Y.; Tao, S.; Zeng, C.; Xia, J.; Xu, K.; Dai, Y.; Li, M. Virtual-state model for analyzing electro-optical modulation in ring resonators. PRL 2024, 132, 123802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R. V. H.; Duque, C. A.; Mora-Ramos, M. E. Electron-impurity states in concentric double quantum rings and related optical properties. Phys. Lett. A 2025, 534, 130226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fang, Y.; Cheng, M.; Lü, T. Y.; Cao, X.; Zhu, Z. Z.; Wu, S. Large second-harmonic generation and linear electro-optic effect in the bulk kagome lattice compound Nb3MX7 (M= Se, S, Te; X= I, Br). Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 115118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F. M. S.; Amato, M. A.; Olavo, L. S. F.; Nunes, O. A. C.; Fonseca, A. L. A.; da Silva Jr, E. F. Intense laser field effects on the binding energy of impurities in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 073201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiroglu, S.; Kasapoglu, E.; Restrepo, R. L.; Duque, C. A.; Sökmen, I. Intense laser field-induced nonlinear optical properties of Morse quantum well. Phys. Status Solidi B 2017, 254, 1600457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Van Duppen, B.; Van der Donck, M.; Peeters, F. M. Magnetopolaron effect on shallow-impurity states in the presence of magnetic and intense terahertz laser fields in the Faraday configuration. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 064108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladugin, M. A.; Yarotskaya, I. V.; Bagaev, T. A.; Telegin, K. Y.; Andreev, A. Y.; Zasavitskii, I. I.; Padalitsa, A. A.; Marmalyuk, A. A. Advanced AlGaAs/GaAs heterostructures grown by MOVPE. Crystals 2019, 9, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobini, E.; Espinosa, D. H.; Vyas, K.; Dolgaleva, K. AlGaAs nonlinear integrated photonics. Micromachines 2022, 13, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberger, W. C. Perturbation method for atoms in intense light beams. PRL 1968, 21, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrila, M.; Kamiński, J. Z. Free-Free Transitions in Intense High-Frequency Laser Fields. PRL 1984, 52, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, N.; Yang, H.; Han, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Qu, F.; Hao, N.; Fu, J.; Zhang, P. Intense high-frequency laser-field control of spin-orbit coupling in GaInAs/AlInAs quantum wells: A laser dressing effect. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 155420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanyao, Q.; Fonseca, A. L. A.; Nunes, O. A. C. Hydrogenic impurities in a quantum well wire in intense, high-frequency laser fields. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 16405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastard, G. Superlattice band structure in the envelope-function approximation. Phys. Rev. B 1981, 24, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, M.; Gavrila, M. Stabilization of atomic hydrogen in superintense, high-frequency laser fields of circular polarization. PRL 1990, 65, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, M.; Potvliege, R. M.; Proulx, D.; Shakeshaft, R. Multiphoton processes in an intense laser field. V. The high-frequency regime. Phys. Rev. A 1991, 43, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Piazza, A.; Müller, C.; Hatsagortsyan, K. Z.; Keitel, C. H. Extremely high-intensity laser interactions with fundamental quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 1177–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multiphysics, COMSOL. (2022). Version 6.1. COMSOL AB: Stockholm, Sweden.

- Boyd, R.W.; Gaeta, A.L.; Giese, E. Nonlinear Optics. In Springer Handbook of Atomic, Molecular; Springer International Publishing: Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, D.; Chuang, S. L. Calculation of linear and nonlinear intersubband optical absorptions in a quantum well model with an applied electric field. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1987, 54, 2196–2204. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, K. X.; Gu, S. W. Nonlinear optical rectification in parabolic quantum wells with an applied electric field. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 16322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosencher, E.; Bois, P. Model system for optical nonlinearities: asymmetric quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 11315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirtori, C.; Nagle, J. Quantum Cascade Lasers: the quantum technology for semiconductor lasers in the mid-far-infrared. C. R. Phys. 2003, 4, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S. Properties of semiconductor alloys: group-IV, III-V and II-VI semiconductors; John Wiley & Sons 2009.

- Seilmeier, A.; Hübner, H. J.; Abstreiter, G.; Weimann, G.; Schlapp, W. Intersubband relaxation in GaAs-AlxGa1-x As quantum well structures observed directly by an infrared bleaching technique. PRL 1987, 59, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capasso, F.; Sirtori, C.; Cho, A. Y. Coupled quantum well semiconductors with giant electric field tunable nonlinear optical properties in the infrared. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1994, 30, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F. M. S.; Amato, M. A.; Nunes, O. A. C.; Fonseca, A. L. A.; Enders, B. G.; Da Silva, E. F. Unexpected transition from single to double quantum well potential induced by intense laser fields in a semiconductor quantum well. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 123111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (nm) | F (kV/cm) | (meV) | (meV) | (meV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | |||

| 5 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 20 | ||||

| 4 | 0 | |||

| 5 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 20 |

| (nm) | F (kV/cm) | () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| () | () | |||

| 0 | 0 | |||

| 5 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 20 | ||||

| 4 | 0 | |||

| 5 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).