1. Introduction

The mandible has an intricate internal structure. Within it lies a network of canals that accommodate arteries, veins, and nerves, forming the vascular and nervous plexuses that supply both the teeth and the mandible itself. These vessels originate from major arteries such as the sublingual, subgenial, and mylohyoid arteries, entering the mandible through foramina located on its posterior surface, typically between the first premolars. These openings are collectively known as the lingual foramina.

Two groups of lingual foramina have been described in relation to their location in the mandible, namely the median lingual foramina (MLF) and the lateral lingual foramina (LLF). Furthermore, the MLF have been further categorized as superior (s-MLF) and inferior (i-MLF) in relation to the genial tubercle. The associated to a lingual foramen vascular canal is called lingual vascular canal (LC); in keeping with the terminology proposed for lingual foramina, a LC could be either median (MVC) or lateral (LVC) [

1].

Lingual foramina have been widely studied due to their clinical significance, particularly the medial lingual foramen, which is positioned above the genial tubercle. While most research has focused on this foramen, smaller foramina in the interpremolar region have received less attention. This may be due to their diminutive size, which makes them more difficult to detect, especially in cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans, where smaller foramina may go unnoticed. Consequently, their presence and clinical importance are often underestimated [

1,

2,

3].

Arterial branches pass through the lingual foramina, either entering or exiting the mandibular cortex. The diameter of these branches ranges from 0.2 mm to 1 mm, reflecting the size of the accompanying neurovascular bundle. During surgical procedures in this region, these vessels are at risk of injury, which can lead to varying degrees of hemorrhage. Severe bleeding may result in a hematoma capable of obstructing the airway, while less significant hemorrhage can compress nearby nerves, causing ischemia and sensory deficits in the mandibular teeth or gingivae [

1].

In this observational study, we analyzed the number and diameter of lingual foramina in dry mandibles housed in the osteological collection of the Laboratory of Anatomy, Department of Medicine, Democritus University of Thrace, Greece. We mapped the foramina relative to specific anatomical landmarks, including the genial tubercle, alveolar process, and alveolar ridge, and examined the positioning of the genial tubercle on the posterior surface of the mandible. By identifying a potential bleeding risk zone, this study aims to provide valuable anatomical insights for surgeons, aiding in preoperative planning to minimize complications and reduce the risk of patient mortality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Selection

The present observational study examined dry mandibles from the Laboratory of Anatomy, Department of Medicine, Democritus University of Thrace, Greece. The mandibles originated from an undefined population of Greek ancestry, with no available data on age or sex. All dentate mandibles had at least one well-defined alveolus. Mandibles exhibiting fractures, erosion, or deformities were excluded from the study. The study focused on determining the number, diameter, and anatomical position of lingual foramina relative to the genial tubercle and alveolar process. Additionally, the position of the genial tubercle on the posterior surface of the mandible was assessed.

The quality of the present study, based on the potential risk of bias due to the methods used and the reporting of results was judged using the Anatomical Quality Assessment (AQUA) tool [

4].

An ethics committee approval was not applicable due to the cadaveric material studied.

2.2. Measurements

The study objectives were to measure the number, location, diameter, as well as the distance between lingual foramina and the genial tubercle, alveolar ridge/superior border, and inferior border.

The foramina located on the posterior surface of the mandible between the first premolars were included in the analysis. The number of lingual foramina was determined through careful inspection of the lingual surface under physical lighting. Their diameters were measured using a flexible stainless steel wire with a diameter ranging from 0.2 mm to 1.2 mm (UA218893; Zhejiang, China), as described elsewhere [

5]. Any foramen with a diameter smaller than 0.2 mm was not recorded. If a wire could not be inserted into a foramen, its diameter (d

i) was recorded as the next smaller available size. As such, the absolute maximum error (d

e) introduced in each measurement is 0.1 mm, while the mean relative error is represented by the mean of the ratios d

e / (d

i + d

e) for every i-th foramen.

All measurements were performed using a digimatic caliper (Mitutoyo Co., Japan) of 0.01 mm accuracy.

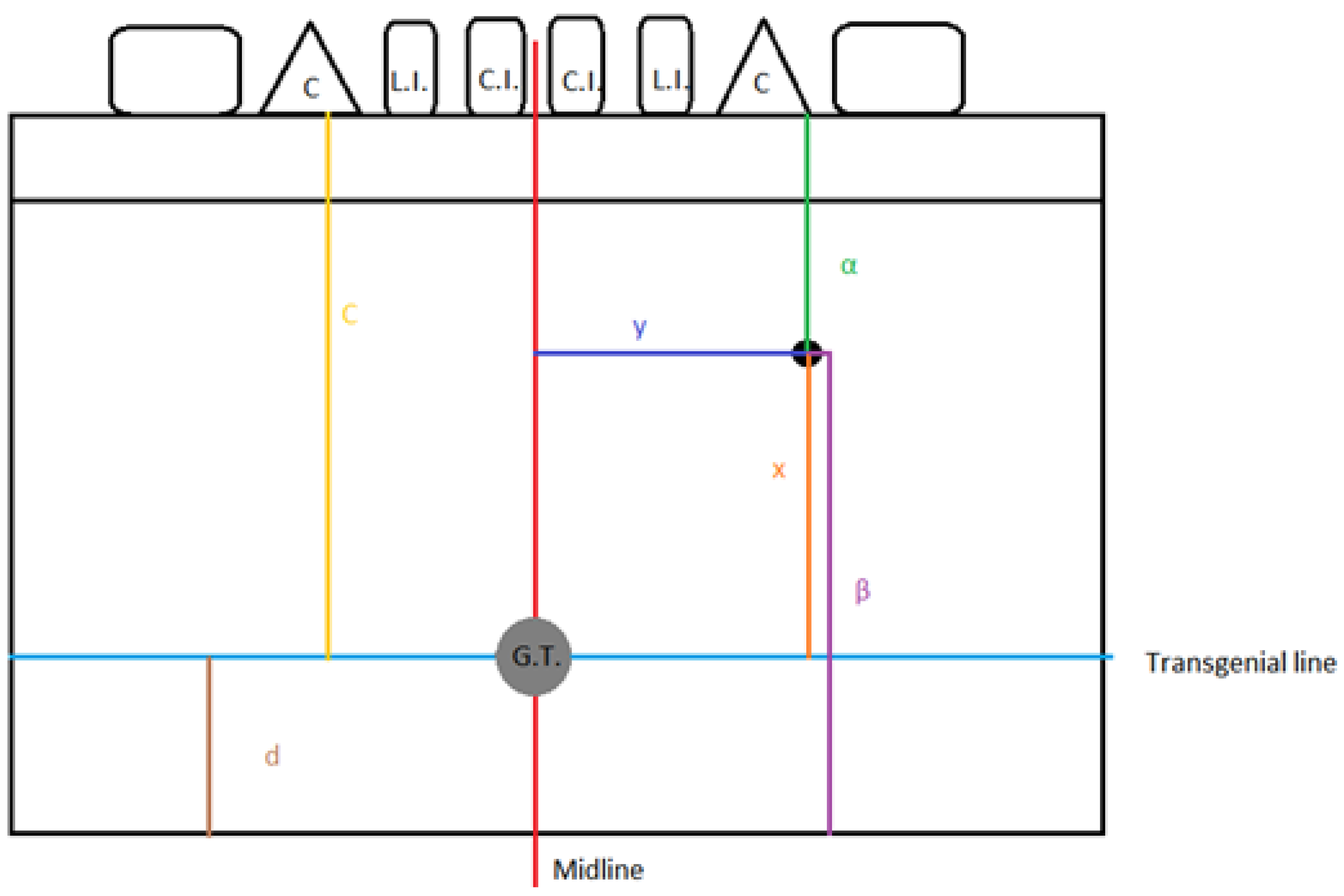

Each distance was measured from the center of each lingual foramen. The location of each lingual foramen was determined using two imaginary lines (horizontal and vertical) intersecting at the genial tubercle, dividing the area into four quadrants: anterior superior, posterior superior, anterior inferior, and posterior inferior. In detail, to determine the position of each foramen, the following distances were measured: i) Height, namely the vertical distance between the genial tubercle and the foramen (x); ii) Length, namely the horizontal distance between the genial tubercle and the foramen (y); iii) Radius, namely the distance between the genial tubercle and the foramen (represented by the square root of x

2 + y

2); iv) Distance from the foramen to the alveolar ridge/superior border (α); and v) Distance from the foramen to the inferior border (β). Similarly, to determine the position of the genial tubercle on the posterior surface of the mandible, the following measurements were taken: i) Distance from the genial tubercle to the alveolar ridge/superior border (c); Distance from the genial tubercle to the inferior border (d) (

Figure 1).

We defined the transgenial line as the horizontal line that traverses the middle of genial tubercle. The morphology of the tubercle does not have an impact on the position of the line.

In dentate mandibles, the superior margin of the alveolar process was used as a reference landmark. In contrast, for edentulous mandibles, the superior border of the mandible served as the reference for determining the positions of the lingual foramina and genial tubercle.

2.3. Quality Assessment

Using the Anatomical Quality Assessment (AQUA) tool, we assigned a high risk of bias to Domain 1 (Objective(s) and subject characteristics) due to the lack of information regarding sex, age, and medical history of the cadavers. On the contrary, all other Domains, namely Domain 2 (Study Design), Domain 3 (Methodology Characterization), Domain 4 (Descriptive Anatomy), and Domain 5 (Reporting of Results) were considered as having low risk of introducing bias.

2.4. Statistics

Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard errors (SE), and compared using Student’s t-test in case that equal variances could be assumed; else, the Welch’s t-test was alternatively preferred. Discrete variables were expressed as percentages and compared using chi-square test; in case of expected frequencies <5 in ≥25% of cells, the Fisher’s exact test was applied. For the purpose of goodness-of-fit analysis in quadrants, chi square test was used. ANOVA along with Tuckey’s HSD post-hoc test were implemented to compare means along clusters. Two-step cluster analysis was further used to discriminate lingual foramina according to their direction and distance from genial tubercle. The level of statistical significance was set to 0.05. All tests were two-tailed, and performed using SPSS 26.0.

3. Results

3.1. Primary Data

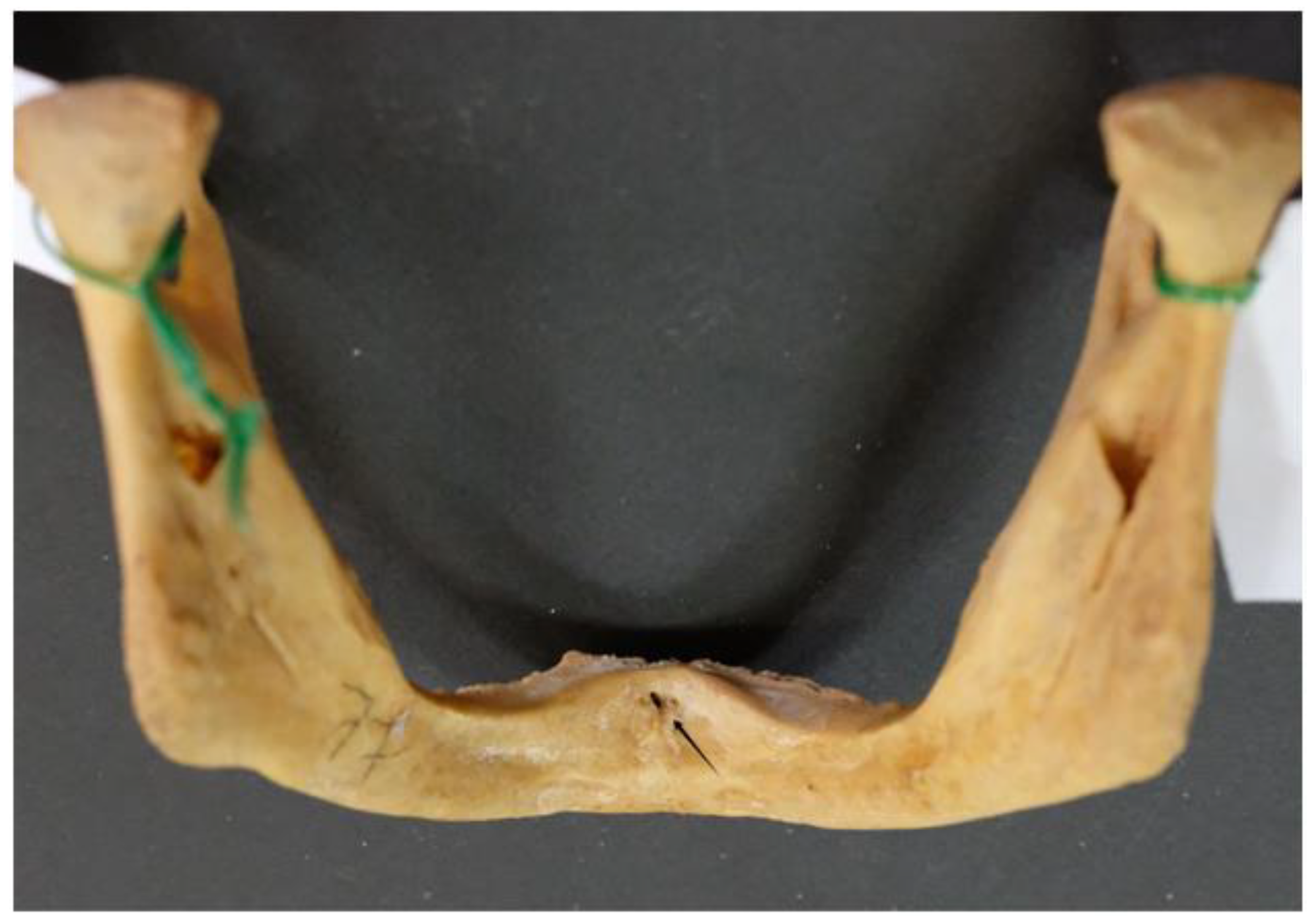

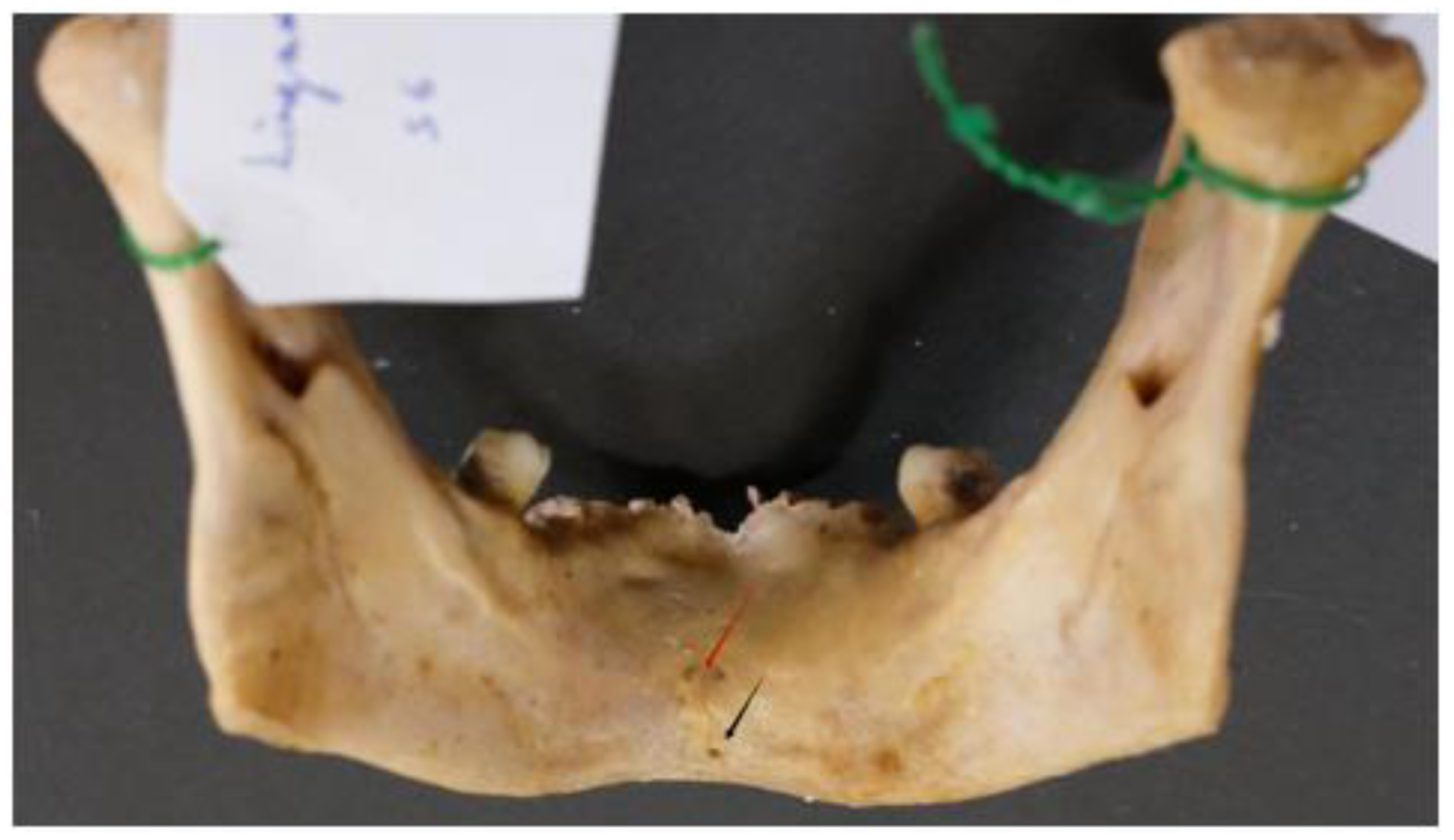

A total of 100 dry mandibles were initially analyzed for the presence of lingual foramina with a diameter of ≥2 mm. In 96 of them (50 dentate and 46 edentulous), 387 lingual foramina (mean: 4.03 per mandible) were recognized. In these mandibles, the genial tubercle was found to be located 15.27 ± 1.11 mm from alveolar ridge, and 14.42 ± 0.37 from inferior border (

Figure 2).

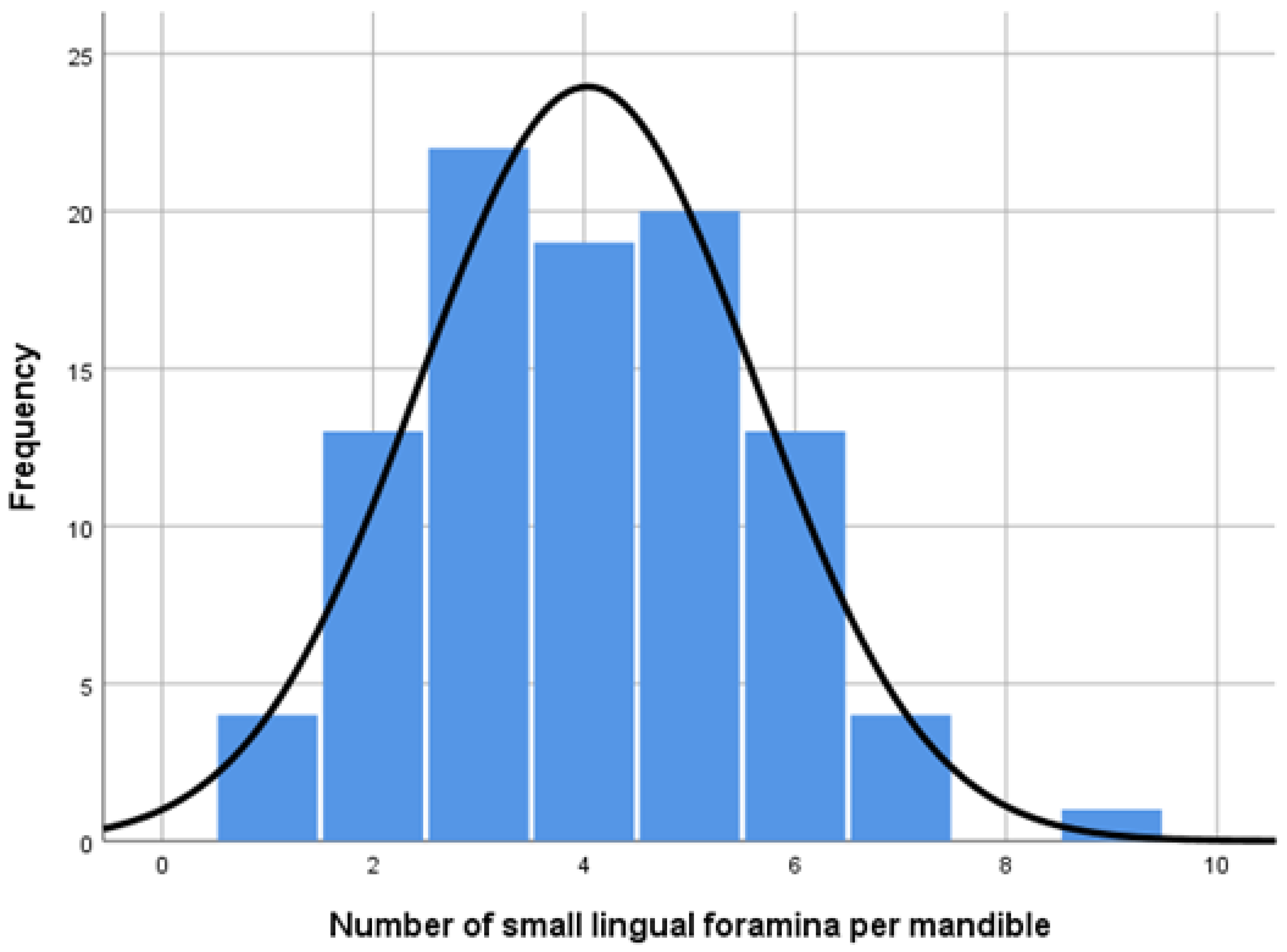

A total of 387 small lingual foramina of diameter ≥ 2 mm were recorded (mean 4.03 per mandible); only 4 mandibles (4.2%) had a single lingual foramen (

Figure 3).

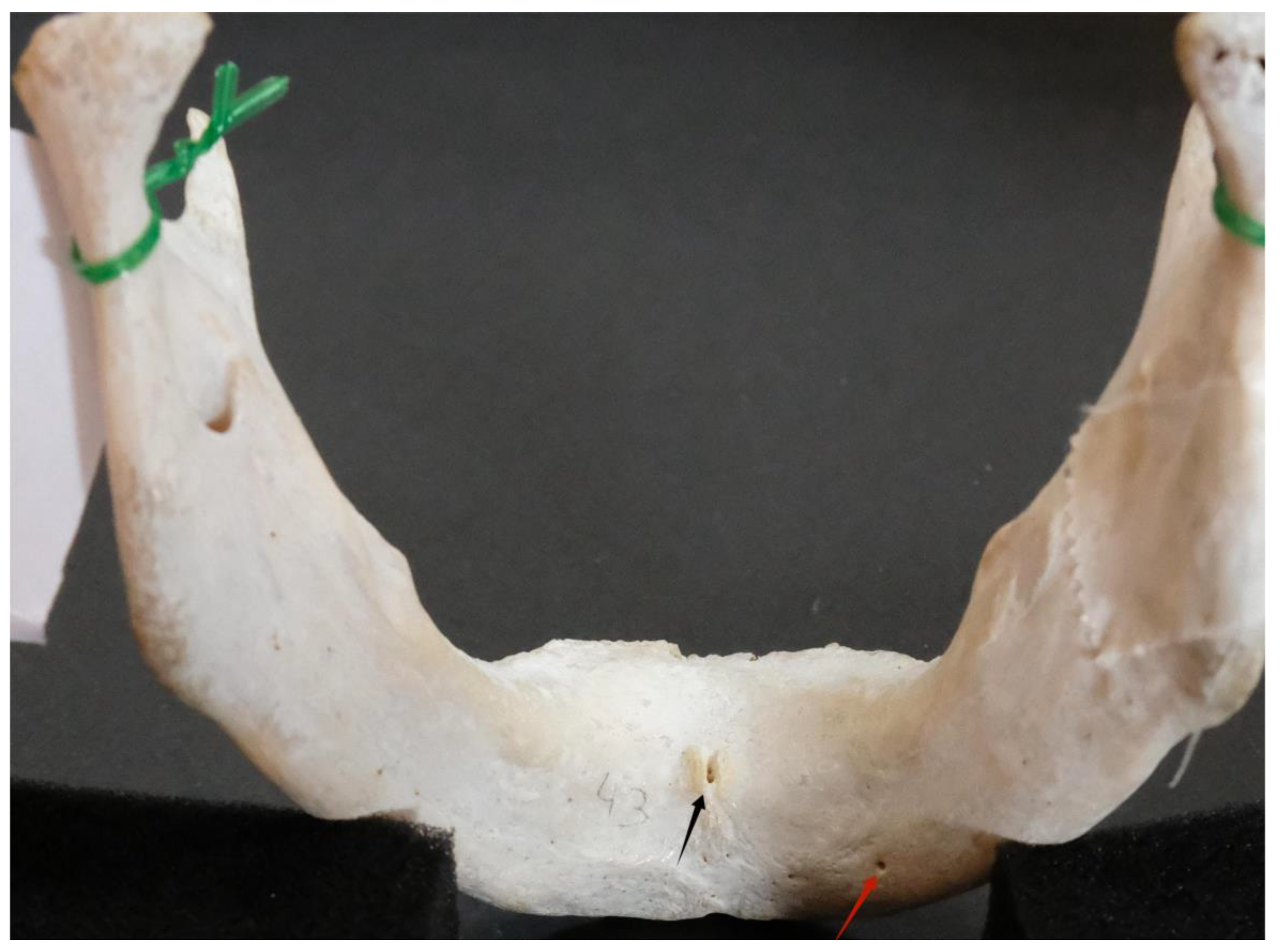

The majority of the mandibles examined (92; 95.8% of the sample) had multiple lingual foramina (up to 9) (

Figure 4;

Figure 5).

The distribution of the number of lingual foramina among the mandibles examined is depicted in

Figure 6.

The lingual foramina observed varied in size, ranging from 0.2 to 1.5 mm (

Figure 7).

The foramina had a diameter of 0.44 ± 0.02 mm; the mean relative error of these measurements was 0.210 (95% CI: 0.202 – 0.218).

The foramina were located 8.74 ± 0.54 mm far from genial tubercle (height 7.57 ± 0.56 mm; length 4.24 ± 0.54 mm). They were 14.19 ± 0.87 mm far from the alveolar ridge, and 14.53 ± 0.84 mm from the inferior border of the mandible.

The lingual foramina observed were located mostly in the left hemimandible (left vs right: 218 vs 169; p = 0.013); however, small lingual foramina were comparable when the level of the genial tubercle was considered (upwards vs. downwards: 196 vs 191; p = 0.799) (

Figure 8).

Taken together, small lingual foramina were more prevalent in the upper left quadrant, in relation with genial tubercle (p = 0.043) (

Table 1).

Overall, the 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90% of lingual foramina could be traced at a distance of 4.56, 9.03, 16.56, and 20.86 mm respectively; these distances vary according to the quadrant (

Table 2).

3.2. Clustering Small Lingual Foramina Reveals a Lower Bleeding Risk Zone

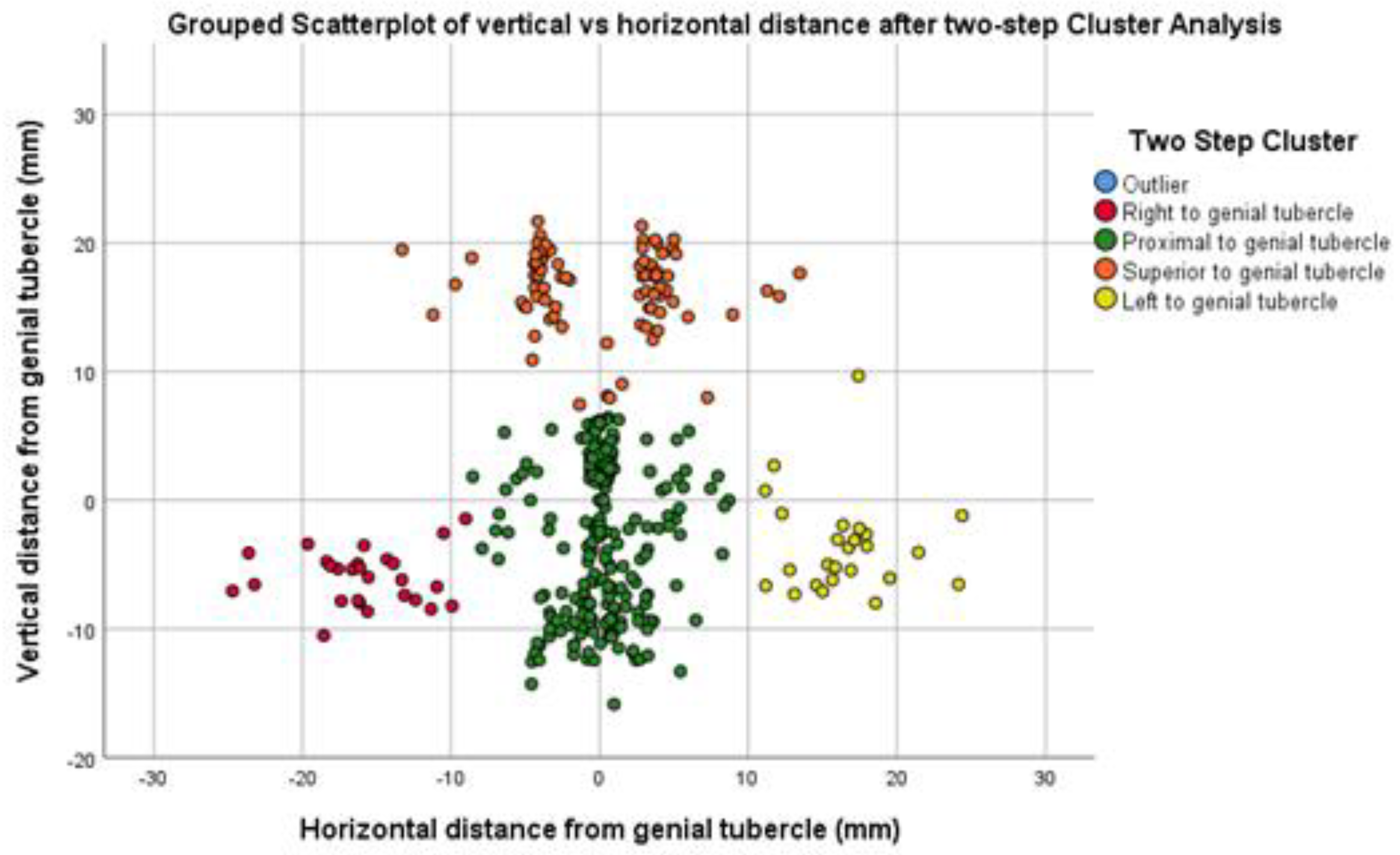

Having detected significant differences in the distribution of lingual foramina in quadrants, we aimed to further analyze the special infrastructure of lingual foramina, thus delineating any potential subgroups among MLF and LLF and investigating their characteristics.

For that purpose, a grouped scattergram depicting vertical vs. horizontal distance of small lingual foramina from genial tubercle is provided as

Figure 9. This scattergram visualizes the results of a two-step cluster analysis, showing four distinct groups of data points corresponding to the 387 small lingual foramina recorded: i) right to genial tubercle (from now on called R-LLF), ii) proximal to genial tubercle (from now on called P-MLF), iii) superior to genial tubercle (S-MLF), and iv) left to genial tubercle (from now on called L-LLF).

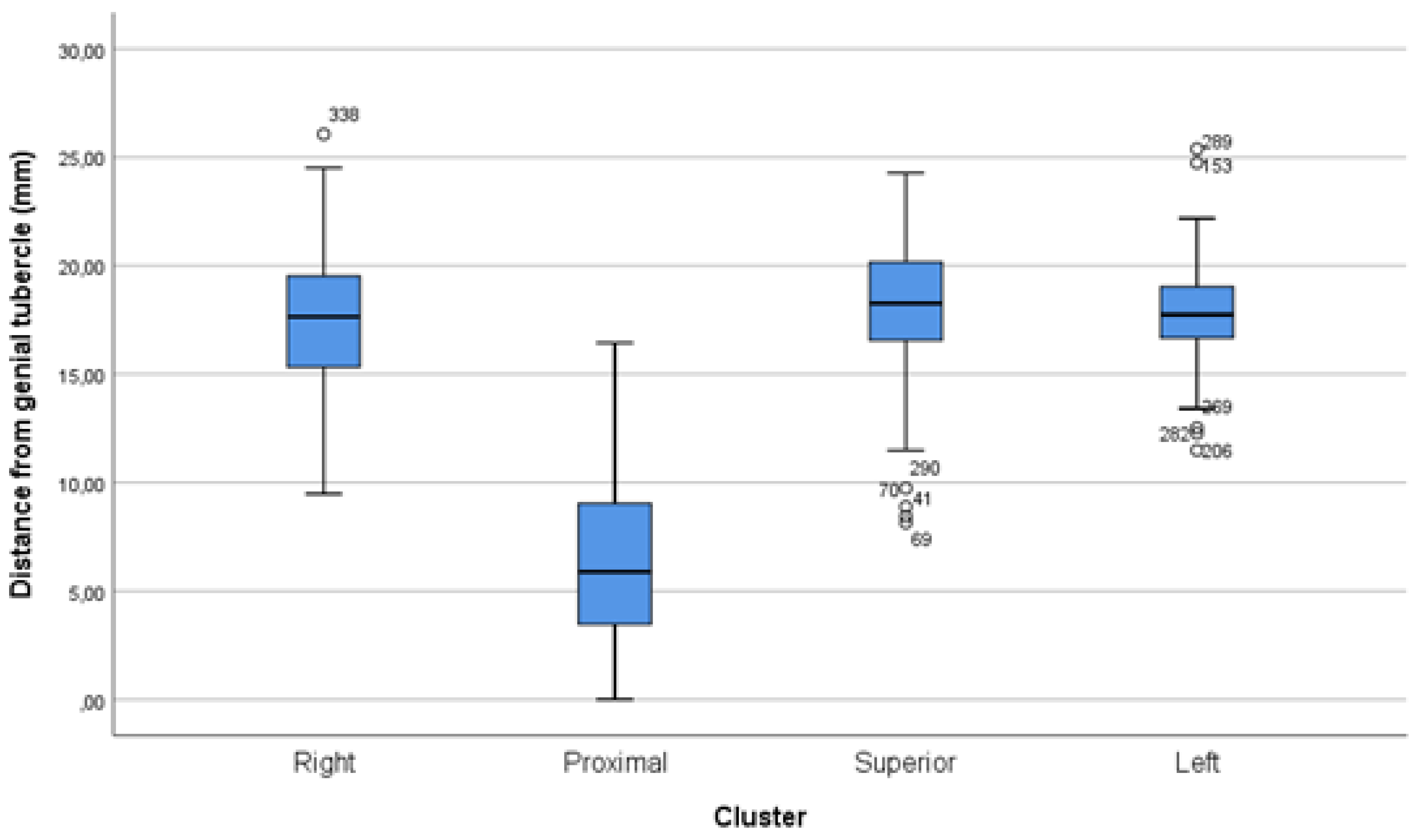

Distances from genial tubercle are provided in

Figure 10.

In detail, the characteristics of small lingual foramina per cluster are shown in

Table 3. The small lingual foramina of the superior cluster are significantly larger when compared with foramina of the right (p = 0.008), proximal (p < 0.001), and left (p = 0.022) clusters.

Of note, 6/387 (1.8 %) foramina presented a diameter ≥ 1.0 mm (3 proximal; 3 superior.

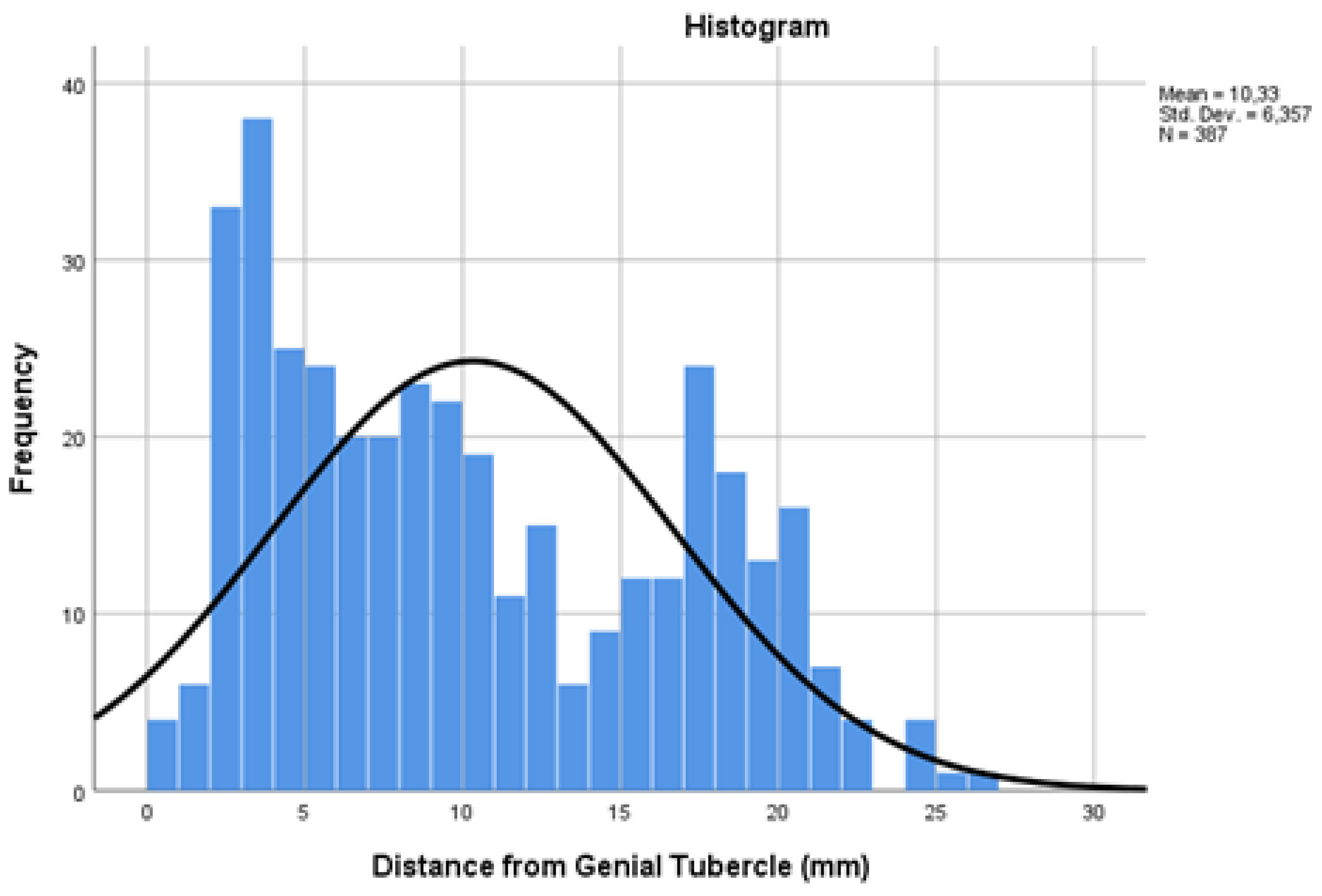

Of note, a bimodal distribution of foramen distances from genial tubercle. The first mode is between mode is between 3.00-4.00 mm, corresponding to the proximal cluster. The second mode is between 17.00-18.00 mm, corresponding to the right, superior, and left clusters. An interstitial, relatively safe “bleeding risk zone” lies between 13.00 ± 0.50 mm (

Figure 11).

3.2. Differences Between Dentate and Edentulous Mandibles

A detailed comparison between dentate and edentulous mandibles is provided in

Table 4.

Lingual foramina that were close to the alveolar ridge (

Figure 12) were more usually detected in dentate mandibles, when compared to edentulous ones.

Interestingly, only one mandible had no central genial lingual foramen (

Figure 13).

4. Discussion

The present observational study included detailed investigation of all lingual foramina of diameter ≥0.2 mm in dry mandibles using stainless steel wires; to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that this approach is followed in cadaveric material.

We have focused on cadaveric material, instead of CBCT, for two reasons: First, the CBCT has lower ability to detect small lingual foramina; second, a lingual duct might be larger than the opening of the related lingual foramen, and thus, more clinically significant. Interestingly though, our results concerning the number of the lingual foramina recognized per mandible (4.03) are in keeping with CBCT-derived data published recently [

6]

In their meta-analysis, Bernardi et al reported that lingual foramina diameters from cadaveric and radiological (CBCT) are comparable; however, the pooled mean diameter is almost double than that of the present study (0.84 mm vs. 0.44 mm). This could be attributed to the different method used [

7].

Silvestri et al. report that the number, diameter, length, and orientation of foramina do not appear to be altered when a patient is edentulous. On the contrary, we have detected significant differences between edentulous and dentate mandibles as far as distance from genial tubercle, alveolar ridge, and inferior border is concerned [

3].

Interestingly, in case of lingual foramina with a diameter ≥ 1.0 mm, both vessel and nerve injury could complicate surgical procedures. Although large lingual foramina are rare, surgeons must be aware of them, especially near the midline.

It is essential to consider lingual foramina during surgical procedures involving the anterior mandibular region. These additional openings in the lingual surface of the mandible host nerves and blood vessels [

8]. Damaging of this neurovascular bundle during surgery, can result in neurosensory disturbances of the mandibular teeth or bleeding.

Understanding the location of the lingual foramina is crucial when performing anterior mandible surgery. The lingual foramina are at risk in many dental and oral surgery procedures at the mental region such periapical surgery, genioplasty, implant placement, treatment of symphyseal fractures, preprothetic and grafting procedures, and the removal of cysts or pathologic lesions [

1,

9,

10]. The role and the contribution of these accessory foramina to regional tumourspread has also been documented [

11,

12].

Oral implants are routinely employed in the rehabilitation of the edentulous mandible, with symphyseal implant placement frequently considered a relatively uncomplicated procedure. Despite this assumption, severe complications from implant surgeries in this region are a documented reality. The lingual foramina serve as a conduit for branches of the sublingual and submental arteries, facilitating anastomosis with the central inferior alveolar vessels. Damage to these vessels can lead to significant bleeding, potentially forming a sublingual hematoma in the floor of the mouth. In severe cases, the hematoma can expand, causing swelling that can obstruct the airway [

13,

14,

15]. Hospitalization may be necessary for monitoring and treatment. Severe bleeding can require emergency intervention, including airway management (e.g., intubation or tracheostomy) [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Thorough preoperative imaging, such as CBCT, is crucial. CBCT can help identify the location and size of lingual foramina, allowing for careful surgical planning. Although serious complications are relatively rare, clinicians need to be well prepared to deal with them.

In this study, we assessed lingual foramina locations by measuring distances from the lingual foramina to both the alveolar crest and the inferior border of the mandible. The latter measurement is considered more reliable, as it remains consistent regardless of whether the mandible is dentate or edentulous. In contrast, the distance between the lingual foramina and the alveolar ridge can change due to resorption of the alveolar ridge with age [

22]. However, several studies have demonstrated the superior accuracy and reliability of CBCT, when compared to the conventional imaging techniques for identifying small foramina, as accessory mental foramina [

23]. This enhanced visualization makes CBCT an invaluable tool for presurgical planning and execution, enabling clinicians to minimize potential complications and achieve optimal results.

The major strength of this study is the use of cluster analysis to discriminate subgroups of lingual foramina and investigate their characteristics. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind. As such, it is novel and adds to the already established literature. On the contrary, one can argue that the use of a not widely utilized method, namely that of the stainless steel wires, to determine the diameter of foramina, could be a relative limitation. However, this method has been extensively analyzed elsewhere, while the interrater agreement determined is very close to absolute [5}. Moreover, the data regarding the prevalence of rare anatomic variants, such as multiple (>8) lingual foramina, or the absence of a central lingual foramen, might be considered prone to considerable reporting bias [

24]. Future research could further enlighten the clinical impact of the present anatomical results.

5. Conclusions

This study provides anatomical insights that contribute to appropriate preoperative planning and the minimization of complications during surgical interventions on the mandible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T., and V.P.; methodology, C.T., Z-M.T., and V.P.; software, V.P.; validation, C.T., Z-M.T., and V.P.; formal analysis, V.P.; investigation, C.T., Z-M.T., and V.P.; resources, C.T., Z-M.T., and V.P.; data curation, V.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T., and V.P.; writing—review and editing, C.T., Z-M.T., and V.P.; visualization, C.T., Z-M.T., and V.P.; supervision, V.P.; project administration, V.P.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

An ethics committee approval was not applicable due to the cadaveric material studied.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used can be provided upon reasonal request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, P.; Truong, M.K.; Adeeb, N.; Tubbs, R.S.; Iwanaga, J. Clinical anatomy and surgical significance of the lingual foramina and their canals. Clin Anat. 2017, 30, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murlimanju, B.V.; Prakash, K.G.; Samiullah, D.; Prabhu, L.V.; Pai, M.M.; Vadgaonkar, R.; Rai, R. Accessory neurovascular foramina on the lingual surface of mandible: incidence, topography, and clinical implications. Indian J Dent Res. 2012, 23, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestri, F.; Nguyen, J.F.; Hüe, O.; Mense, C. Lingual foramina of the anterior mandible in edentulous patients: CBCT analysis and surgical risk assessment. Ann Anat. 2022, 244, 151982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, B.M.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Ramakrishnan, P.K.; Roy, J.; Vikse, J.; Loukas, M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Walocha, J.A. Development of the anatomical quality assessment (AQUA) tool for the quality assessment of anatomical studies included in meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Clin Anat. 2017, 30, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaidi, Z.M.; Tsatsarelis, C.; Papadopoulos, V. Accessory Mental Foramina in Dry Mandibles: An Observational Study Along with Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambi TJRD, Nalini Aswath. Evaluation of Lingual Foramen in the South Indian Population Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2024, 16(Suppl 2), S1140–S1146.

- Bernardi, S.; Bianchi, S.; Continenza, M.A.; Macchiarelli, G. Frequency and anatomical features of the mandibular lingual foramina: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Radiol Anat. 2017, 39, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przystanska, A.; Bruska, M. Foramina on the internal aspect of the alveolar part of the mandible. Folia Morphol 2005, 64, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Jacobs, R.; Lambrichts, I.; Vandewalle, G. Lingual foramina on the mandibular midline revisited: A macroanatomical study. Clin Anat 2007, 20, 246–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Perez, A.; Boix-Garcia, P.; Lopez-Jornet, P. Cone-beam CT assessment of the position of the medial lingual foramen for dental implant placement in the anterior symphysis. Implant Dentistry. 2018, 27, 43–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor JA, MacDonald DG, Patterns of spread of squamous carcinoma within the mandible. Head Neck Surg 1989, 11, 457–461.

- Fanibunda, K.; Matthews, J.N. The relationship between accessory foramina and tumour spread on the medial mandibular surface. J Anat 2000, 196, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, L.; J de Lange, E. Baas, and J. van Ingen. Excessive bleeding in the floor of the mouth after endosseus implant placement: a report of two cases. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2010, 39, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, J.; S Kim, and J. Oh. Hemorrhage related to implant placement in the anterior mandible. Implant Dentistry 2011, 20, e33–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpidis, C.D.R.; RM Setayesh. Hemorrhaging associated with endosseous implant placement in the anterior mandible: a review of the literature. J Periodontol. 2004, 75, 631–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givol, N.; Chaushu, G.; Halamish-Shani, T.; Taicher, S. Emergency tracheostomy following life-threatening hemorrhage in the floor of the mouth during immediate implant placement in the mandibular canine region. J Periodontol. 2000, 71, 1893–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiuc, I.; Tarlungeanu, I.; Pauna, M. Cone beam computed tomography observations of the lingual foramina and their bony canals in the median region of the mandible. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2011, 52, 827–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tomljenovic, B.; Herrmann, S.; Filippi, A.; Kühl, S. Life-threatening hemorrhage associated with dental implant surgery: a review of the literature. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015, 27, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiegnitz E, Maximilian Moergel, and Wilfried Wagner. Vital Life-Threatening Hematoma after Implant Insertion in the Anterior Mandible: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Reports in Dentistry 2015, 2015, 531865. [Google Scholar]

- Peñarrocha-Diago M, José Carlos Balaguer-Martí, David Peñarrocha-Oltra, José Bagán, Miguel Peñarrocha-Diago, Dennis Flanagan, Floor of the mouth hemorrhage subsequent to dental implant placement in the anterior mandible. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dentistry 2019, 11, 235–242. [CrossRef]

- Blanc, O.; Krasovsky, A.; Shilo, D.; Capucha, T.; Rachmiel, A. A life-threatening floor of the mouth hematoma secondary to explantation attempt in the anterior mandible. Quintessence Int 2021, 52, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Charalampakis, A.; Kourkoumelis, G.; Psari, C.; Antoniou, V.; Piagkou, M.; Demesticha, T.; Kotsiomitis, E.; Troupis, T. The position of the mental foramen in dentate and edentulous mandibles: Clinical and surgical relevance. Folia Morphol. 2017, 76, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, M.; Koong, C.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M. Prevalence of Accessory Mental Foramina: A Study of 4000 CBCT Scans. Clin. Anat. 2019, 32, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, V.; Filippou, D.; Fiska, A. Prevalence of rare anatomic variants - publication bias due to selective reporting in meta-analyses studies. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2024, 66, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Measurements protocol.

Figure 1.

Measurements protocol.

Figure 2.

A typical dry mandible; lingual foramina are indicated by arrows.

Figure 2.

A typical dry mandible; lingual foramina are indicated by arrows.

Figure 3.

Single lingual foramen.

Figure 3.

Single lingual foramen.

Figure 4.

Multiple lingual foramina indicated by arrows.

Figure 4.

Multiple lingual foramina indicated by arrows.

Figure 5.

Multiple lingual foramina indicated by arrows.

Figure 5.

Multiple lingual foramina indicated by arrows.

Figure 6.

Histogram depicting the number of lingual foramina per mandible in the study sample.

Figure 6.

Histogram depicting the number of lingual foramina per mandible in the study sample.

Figure 7.

Large lingual foramen (arrow).

Figure 7.

Large lingual foramen (arrow).

Figure 8.

Lingual foramen in lateral position.

Figure 8.

Lingual foramen in lateral position.

Figure 9.

Grouped scattergram depicting vertical vs horizontal distance of small lingual foramina from genial tubercle after two step cluster analysis: four discrete clusters determine a relatively safe, lower “bleeding risk zone” amongst them.

Figure 9.

Grouped scattergram depicting vertical vs horizontal distance of small lingual foramina from genial tubercle after two step cluster analysis: four discrete clusters determine a relatively safe, lower “bleeding risk zone” amongst them.

Figure 10.

Distance from genial tubercle per cluster.

Figure 10.

Distance from genial tubercle per cluster.

Figure 11.

Histogram depicting bimodal distribution of foramen distances from genial tubercle.

Figure 11.

Histogram depicting bimodal distribution of foramen distances from genial tubercle.

Figure 12.

Lingual foramen detected in alveolar position.

Figure 12.

Lingual foramen detected in alveolar position.

Figure 13.

Mandible lacking central genial lingual foramina.

Figure 13.

Mandible lacking central genial lingual foramina.

Table 1.

Goodness-of-fit chi-square test between frequencies in quadrants.

Table 1.

Goodness-of-fit chi-square test between frequencies in quadrants.

| Foramina location |

n (%) |

p-value |

| Left superior quadrant |

117 (30.2) |

0.043 |

| Right superior quadrant |

79 (20.4) |

| Left inferior quadrant |

101 (26.1) |

| Right inferior quadrant |

90 (23.3) |

Table 2.

Distances in mm from genial tubercle that contain lingual foramina at a giver probability / odds ratio; data for all (2nd column), above genial tubercle (3rd column), and below genial tubercle (4th column).

Table 2.

Distances in mm from genial tubercle that contain lingual foramina at a giver probability / odds ratio; data for all (2nd column), above genial tubercle (3rd column), and below genial tubercle (4th column).

|

Probability /OR for a foramen to be included in the zone

|

All lingual foramina; mm

(n=387)

|

Lingual foramina above genial tubercle; mm

(n=196)

|

Lingual foramina below genial tubercle; mm

(n=191)

|

| 25% / 0.33 |

4.56 |

5.45 |

3.69 |

| 50% / 1.00 |

9.03 |

8.20 |

5.93 |

| 75% / 3.00 |

16.56 |

10.03 |

17.22 |

| 95% / 19.00 |

20.86 |

12.73 |

20.56 |

Table 3.

Small lingual foramina characteristics per cluster.

Table 3.

Small lingual foramina characteristics per cluster.

| |

Right

(R-LLF)

(n=27)

|

Proximal

(P-MLF)

(n=254)

|

Superior

(S-MLF)

(n=81)

|

Left

(L-LLF)

(n=25)

|

p-value |

| Diameter |

0.39±0.10 |

0.42±0.19 |

0.52±0.22 |

0.40±0.16 |

<0.001 |

| Height |

6.41±2.10 |

5.61±3.52 |

16.97±3.12 |

5.01±2.39 |

<0.001 |

| Length |

16.26±3.99 |

2.18±2.02 |

4.89±2.55 |

16.82±3.52 |

<0.001 |

| Distance from genial tubercle |

17.64±3.81 |

6.43±3.67 |

17.83±3.24 |

17.72±3.48 |

<0.001 |

| Distance from alveolar ridge |

22.88±5.70 |

16.62±7.13 |

4.12±4.61 |

19.50±6.37 |

<0.001 |

| Distance from inferior border |

9.71±2.37 |

11.90±5.39 |

27.79±5.35 |

10.21±3.84 |

<0.001 |

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and comparison between dentate and edentulous mandibles; values are expressed in mm.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and comparison between dentate and edentulous mandibles; values are expressed in mm.

| Parameter |

All mandibles(n=96) |

Dentate mandibles(n=50) |

Edentulous mandibles (n=46) |

p-value |

| Foramina number |

|

|

|

|

| Per mandible (n)

|

4.03 ± 0.16 |

4.54 ± 0.23 |

3.48 ± 0.20 |

0.001 |

|

Foramina location (n) |

|

|

|

|

| Right cluster (R-LLF) |

27 |

20 |

7 |

<0.001 |

| Proximal cluster (P-MLF) |

254 |

122 |

132 |

| Superior cluster (S-MLF) |

81 |

69 |

12 |

| Left cluster (L-LLF) |

25 |

16 |

9 |

|

Foramina characteristics (mean ± SE) |

|

|

|

|

| Diameter |

0.44 ± 0.02 |

0.45 ± 0.01 |

0.43 ± 0.02 |

0.094 |

| Height |

7.57 ± 0.56 |

8.81 ± 0.42 |

5.80 ± 0.30 |

<0.001 |

| Length |

4.24 ± 0.54 |

5.03 ± 0.39 |

3.11 ± 0.34 |

0.002 |

| Distance from genial tubercle |

8.74 ± 0.54 |

12.02 ± 0.46 |

7.93 ± 0.36 |

<0.001 |

| Distance from alveolar ridge |

14.19 ± 0.87 |

15.46 ± 0.64 |

12.38 ± 0.53 |

<0.001 |

| Distance from inferior border |

14.53 ± 0.84 |

16.79 ± 0.59 |

11.31 ± 0.48 |

<0.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).