2. Materials and Methods

The retrospective study was conducted at the Maxillofacial Unit of the Magna Grecia University of Catanzaro. The data analyzed concern patients who underwent submandibular sialoadenectomy (1 January 2014 to 31 Dicember 2023) with the use of IFNM compared with those of patients who did not undergo monitoring. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Magna Graecia University of Catanzaro (protocol number 146/2016) and informed consent was obtained from the patients. To mitigate the risk of selection bias, only cases undergoing surgical treatment by two experienced senior surgeons (MGC and IB) were included in the analysis and the choice of device use was random.

Patients were divided into two groups:

- Group 1 (G1), surgical procedures were performed without the use of IFNM and identification and clamping of facial vessels;

- Group 2 (G2), surgical procedures were performed with the use of IFNM and without identification and clamping of facial vessels.

The information, obtained from the medical records and histological examinations, was organized in a database using Microsoft Excel (Version 2017 (Redmond, WA, USA) and included personal data, tobacco/alcohol habits, comorbidities, other interventions performed, histological diagnosis, presence or absence of facial paralysis with involvement of the MMB and surgical timing. Clinical and telephone follow-up collected data on resolution or persistence of paralysis. In this context, the term “permanent paralysis” is used to describe any degree of facial weakness that persists for a minimum of six months following surgery.

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- patients of both sexes and without age limits, undergoing surgery of the submandibular gland for the presence of submandibular lodge pathologies;

- patients with post-operative histological diagnosis of benign pathology (siaolithiasis, chronic recurrent sialadenitis, benign tumors);

- patients undergoing sialodenectomy of the submandibular gland.

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

- patients with incomplete documentation;

- patients operated on in the same location for other pathology;

- patients with previous deficits affecting the facial nerve;

- patients with malignant tumor

The analysis of the FN function was based on a daily evaluation del MMB and was carried out preoperatively, postoperatively on the first day, and remotely, with photographic documentation. To categorize the FN function the modified House–Brackmann classification system [

10] we use a scoring system of levels I to IV of dysfunction, where I indicated no dysfunction, II indicated mild dysfunction, III indicated moderate dysfunction, and IV indicated severe dysfunction (

Table 1).

2.1. Surgical Technique

In both patient groups, submandibular sialodenectomy was performed under general anesthesia, with standard practice procedures previously established in our clinical setting. One hour before the start of surgery, patients were administered intravenous midazolam at a dose of 1 to 5 mg. After adequate preoxygenation and denitrogenization, anesthesia was induced with propofol 2 mg/kg intravenously (i.v.) as a bolus (for sedation) in combination with a single reduced dose of rocuronium (0.3 mg/kg). Analgesia was provided by continuous infusion of remifentanil at a rate of up to 1 mcg × kg/min. The surgical technique used was transcervical submandibular sialodenectomy. The cervical skin incision was made 3 cm from the lower margin of the mandible, parallel to it and about 4-5 cm long, in a natural crease of the neck. The incision runs from the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the submental area, the skin and platysma are incised and the upper and lower flaps are raised respectively to the lower margin of the mandible and below the submandibular gland [

11]. The dissection then proceeds from the superficial cervical fascia to the gland, the facial vessels are identified and tied and clamped to ensure protection of the MMB of the FN. In the subjects of G2 the mapping or “blind” stimulation

of the surrounding tissues the MMB was performed by using the probe (Medtronic) at no more than 2mA, without proceeding with the identification al clamp of the facial vessel. A blunt dissection of the gland is performed from back to front, identifying the lingual nerve, Wharton’s duct and hypoglossal nerve. The Wharton’s duct is then ligated, the gland is removed, hemostasis is carefully checked and sutured in layers. In G2 the device used for IFNM was the Nerve Integrity Monitor (NIM

®) (Medtronic, Fridley, MN, USA), which is one of the most widely used monitoring devices in thyroid surgery. The device provides audiovisual information based on electromyographic (EMG) activity resulting from intraoperative nerve stimulation. It consists of a recording electrode and a monopolar or bipolar nerve stimulation probe connected to a pulse generator. In parotid surgery four recording electrodes are used, while in submandibular gland surgery a single channel is sufficient to monitor the muscular response of the orbicularis oris, innervated by the MMB of the FN. Immediately after intubation to verify that the facial electrode is correctly placed we perform a tapping test of this muscle and observing a response wave in the monitor due to this stimulation.

At the end of the intervention in the patients of the G2, the system generated a report containing the electromyographic tracings that was inserted in the medical record. In the post-operative period, the patients were monitored for possible complications, including deficits of the FN, in particular of its MMB. Patients who developed a FN injury were referred to a rehabilitation program in collaboration with the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department of the “Renato Dulbecco” University Hospital in Catanzaro and subsequently subjected to follow-up checks.

Statistical Analysis

The dataset was subjected to statistical analysis using R software. A descriptive analysis was performed, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine the likelihood of patients developing a postoperative deficit depending on whether or not they underwent IFNM. In addition, univariate and multivariate linear regression models were used to examine the impact of monitoring on surgical time. The level of statistical significance was set at p value<0.05.

The dataset included demographic information and details of surgical procedures performed, comorbidities, histological diagnoses, and postoperative FN function. Subsequently, data on the recovery or permanence of facial paralysis were collected through clinical and/or telephone follow-up. In this context, the term “permanent paralysis” is used to describe any degree of facial weakness that persists for a minimum of six months following surgery.

Results

From 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2023, 104 patients underwent submandibular sialodenectomy at the Maxillofacial Unit of the Magna Grecia University of Catanzaro, of which 101 met the inclusion criteria, while 3 patients were excluded because they had been operated on in the same location for another pathology.

Of the 101 patients, 45 (44,5%) were female and 56 (55,4%) were male. Of these 101 patients, 50 (49,5%) were G1 and 51 (50,5%) patients were G2.

Of the 50 G1 patients, 24 (48 %) were female and 26 (52%) were male, while of the 51 G2 patients, 21 (41%) were female and 30 (59%) were male.

The mean age was 55 ± 16 years in the entire patient cohort, 56 ± 16 years in G1, and 54 ± 15 years in G2.

All patients underwent submandibular sialoadenectomy (100%), of which 50 were in G1 ( 49.5 % of the total patients in G1) and 51 in G2 (50.5 % ), according to the surgical technique described.

The length of hospital stay is 5.19 ± 1.93 days considering the entire cohort of patients, while it is equal to 5.24 ± 2.20 days for G1 and 5.14 ± 1.64 for G2 (

Figure 1).

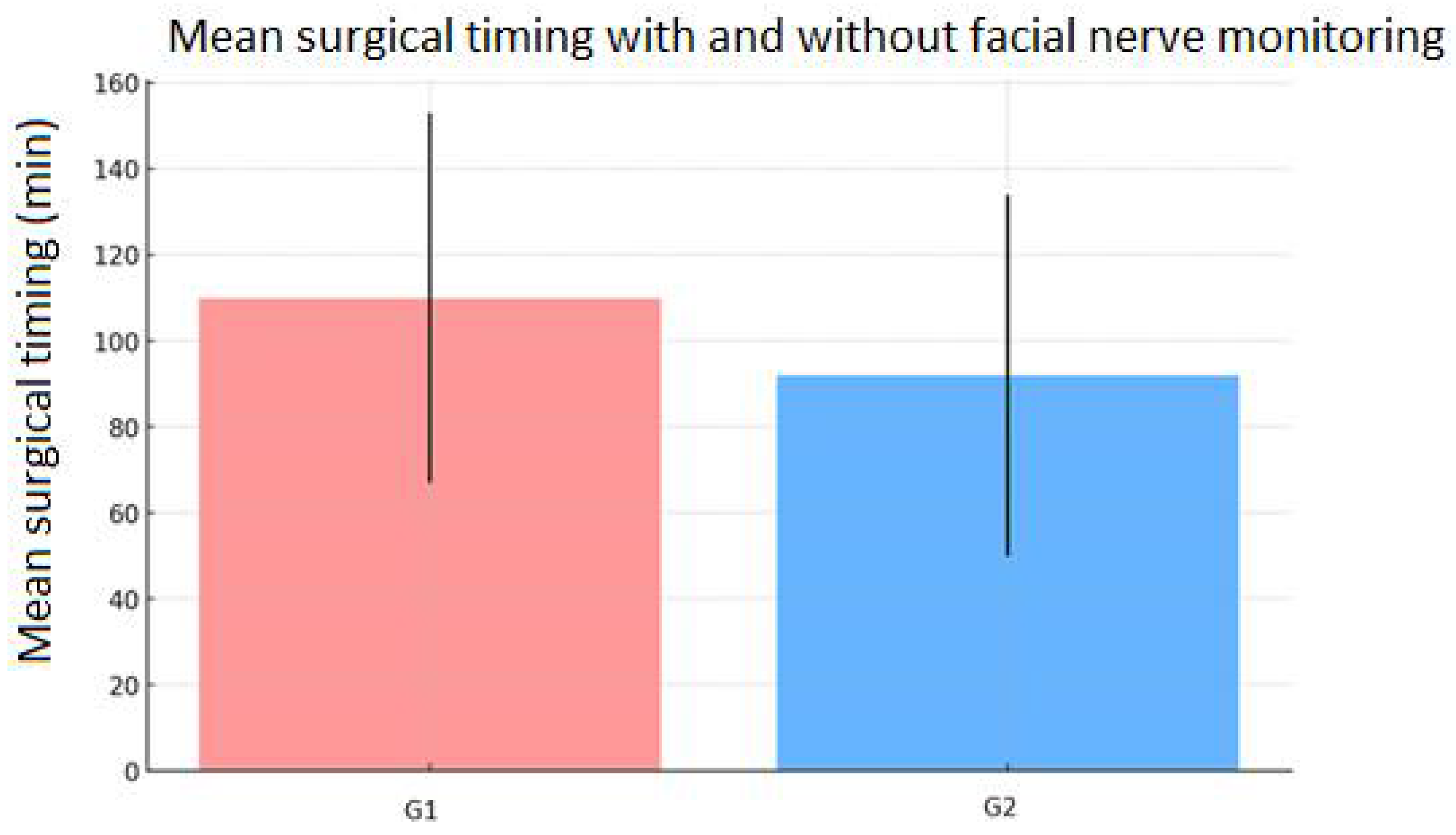

The surgical timing was found to be 99 ± 44 minutes considering the entire cohort of patients, 110 ± 43 minutes for G1 and 92 ± 42 minutes for G2 (

Figure 2).

As regards smoking status, in the entire cohort of patients, 53 (52%) were non-smokers, 14 (14%) were ex-smokers and 34 (34%) were smokers; in G1, 32(64%) patients were non-smokers, 5 (10%) were ex-smokers and 13 (26%) were smokers; while for G2, 21 patients (41%) were non-smokers, 9 (18%) were ex-smokers and 21 (41%) were smokers. (

Figure 3).

The diagnosis was divided into three categories: sialolithiasis, benign tumour and other pathologies (sialadenitis, follicular hyperplasia, Kuttner tumor). Patients operated for sialolithiasis were a total of 78 (77%), of which 46 belonged to G1 (59% of the total patients in G1) and 32 to G2 (41% of the total patients in G2). Patients operated for neoplasia were 10 (10%), of which 4 belonging to G1 (40%) and 6 (60 %) to G2, larger than 2 cm in size, with intraparenchymal localization, with preoperative cytological diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma confirmed with postoperative histological examination. Patients with another diagnosis were a total of 13 (12 % of the total patients), of which 5 of G1 (38% of the total patients in G1), while the remaining 8 belonged to G2 (61% of the total patients in G2). (

Table 2)

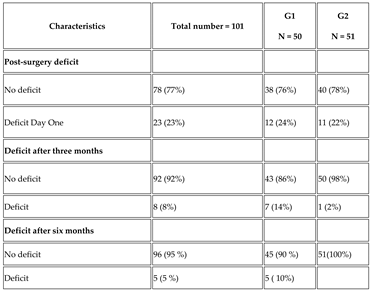

The descriptive analysis of the postoperative paralysis demonstrated that 78 patients (77%) of the entire cohort did not report paralysis, in particular 38 (76%) of G1 and 40 (78%) of G2.

Twenty-three patients (23%) of the entire cohort exhibited varying degrees of paralysis, in particular 12 patients (24%) of G1 and in 11 patients (22%) of G2, but none of the patients reported permanent paralysis.(

Table 3)

On the day following surgery 12 subjects of G1 exhibited varying degrees of paralysis and in particular four demonstrated grade I dysfunction while eight exhibited grade II dysfunction. Of the 11 subjects of G2, eight exhibited grade I dysfunction, while three demonstrated grade II dysfunction.

After three months all the patients of both groups with grade I dysfunction no longer exhibited any dysfunctions. Of the patient with grade II dysfunction in eight persisted the dysfuction (seven of G1 and one of G2), after six months the dysfuction of grade II persisted only in five patients of G1.

Regarding locoregional postoperative complications, edema was observed in 30 subjects ( 29.7 %) which resolved on average after five days and treated with corticosteroids only when considered clinically significant, the minor emorrhages were not treated, wound infection was noted in 5 subjects (4.9%) treated with antibiotics.

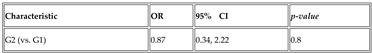

Statistical investigations were conducted to evaluate the correlation between variables of interest. For all analyses performed, a significance level α of 5% and a confidence interval (CI) of 95% were considered. The first test conducted is the univariate and multivariate logistic regression for the baseline deficit. The odds ratio (OR) for G2 (vs. G1) in relation to baseline deficit is 0.87 (p = 0.8), indicating that monitoring does not have a significant association with the reduction in risk of postoperative deficit (

Table 5)

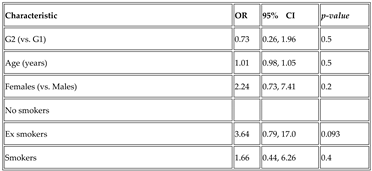

The second test involved the multivariate regression analysis, always considering G2 vs G1, but adjusted for age, sex, smoking status and vascular ligation. The OR remains non-significant with a value of 0.73 and p = 0.5 (

Table 6).

This OR value indicates that patients in G2 have a 27% lower probability ((0.73 – 1) *100) of developing a postoperative deficit compared to those in G1, but this effect is not statistically significant since the resulting p-value is above the pre-set threshold of 0.05. Considering age (expressed in years), the OR value of 1.01 means that each year of age is associated with a 1% increase in the probability of developing a post-operative deficit, but even in this case the effect is minimal since the corresponding p-value = 0.5 indicates that age does not have a significant statistical effect. When considering gender (female vs. male), OR = 2.24 indicates that female patients are 2.24 times more likely to develop a postoperative deficit than male patients. Again, the effect is not statistically significant as the p-value = 0.2 and greater than 0.05. Considering the condition of ex-smoker vs. non-smoker, an OR value of 3.64 is observed, suggesting that ex-smokers are 3.64 times more likely to develop a post-operative deficit compared to non-smokers. The p-value = 0.093, although close to the value of 0.05, does not reach the threshold of significance. As for smoking vs non-smoking status, the OR is 1.66, so smokers have a 1.66 times higher probability of developing a post-operative deficit compared to non-smokers, but the effect is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.4).

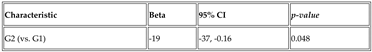

Subsequently, a univariate and multivariate linear regression was performed for surgical timing, which shows that facial nerve monitoring is significantly associated with a shorter surgical time. In the univariate regression, G2 has a surgical time reduced by approximately 19 minutes compared to G1 (with a p-value = 0.048). (

Table 7)

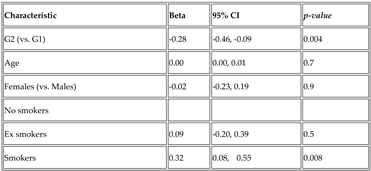

This effect remains statistically significant even in multivariate regression, where the association is even stronger (p-value = 0.004), even after adjusting for variables such as age, sex, smoking status.

Furthermore, among smoking patients, a longer surgical timing was observed compared to non-smokers (always statistically significant with a p-value of 0.008), suggesting that smoking status may influence the duration of the intervention (

Table 8).

Considering G2 vs. G1, Beta is -0.28 indicating that IFNM is associated with an average reduction of 0.28 minutes in surgical timing; the p-value of 0.004 less than 0.05 indicates that this reduction is statistically significant. If, instead, we consider age (in years), Beta is 0.00, it means that age has no effect on surgical timing, but in this case the p-value equal to 0.7 indicates that this data is not statistically significant. Taking into account gender (female vs. male), the Beta coefficient of -0.02 indicates that women have a slightly shorter surgical timing (0.02 minutes) than men, but the effect, in addition to being practically zero, is not statistically significant since p-value = 0.9.

Considering ex-smoker status (vs. non-smoker), Beta is 0.09, so ex-smokers have a slightly longer surgical timing (by 0.09 minutes), but the effect is small and not statistically significant with a p-value of 0.5.

Considering, instead, the status of smoker vs. non-smoker, Beta is 0.32, therefore smokers have a significantly longer surgical timing of 0.32 minutes compared to non-smokers; this data is instead statistically significant since the p-value is 0.008.

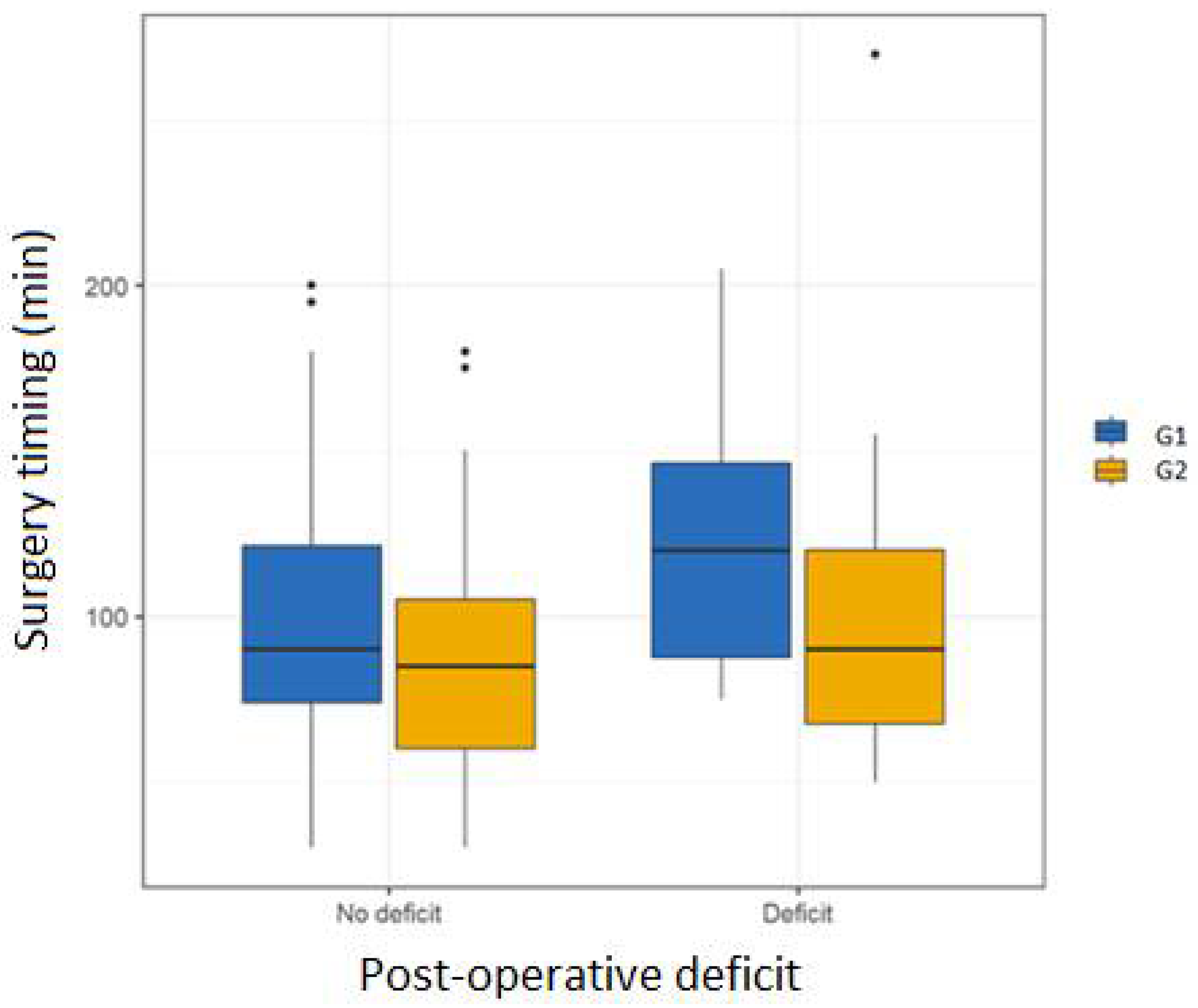

Finally, a boxplot and a scatterplot were constructed to graphically represent the relationships of interest.

The boxplot (

Figure 5) is used to visualize the distribution of a data set and its quartiles. In this graph, the vertical axis represents the surgical timing (expressed in minutes), while the horizontal axis shows the variable post-operative deficit with two categories: “No deficit” and “Deficit” and the data are divided into G1 and G2.

Each boxplot shows the distribution of data for a combination of postoperative deficit and nerve monitoring. The horizontal line within each box represents the median surgical timing.

The edges of the box correspond to the first and third quartiles (the length of the box therefore represents the central 50% values of the data). The vertical lines (whiskers) extend to the minimum and maximum values, excluding outliers (represented as black dots outside the whiskers), i.e., values that deviate significantly from the rest of the data. This graph is useful for comparing surgical times between patients with and without deficits, and for examining the effect of intraoperative monitoring. The graph shows that patients subjected to facial nerve monitoring during surgery, had shorter surgical times regardless of postoperative deficit.

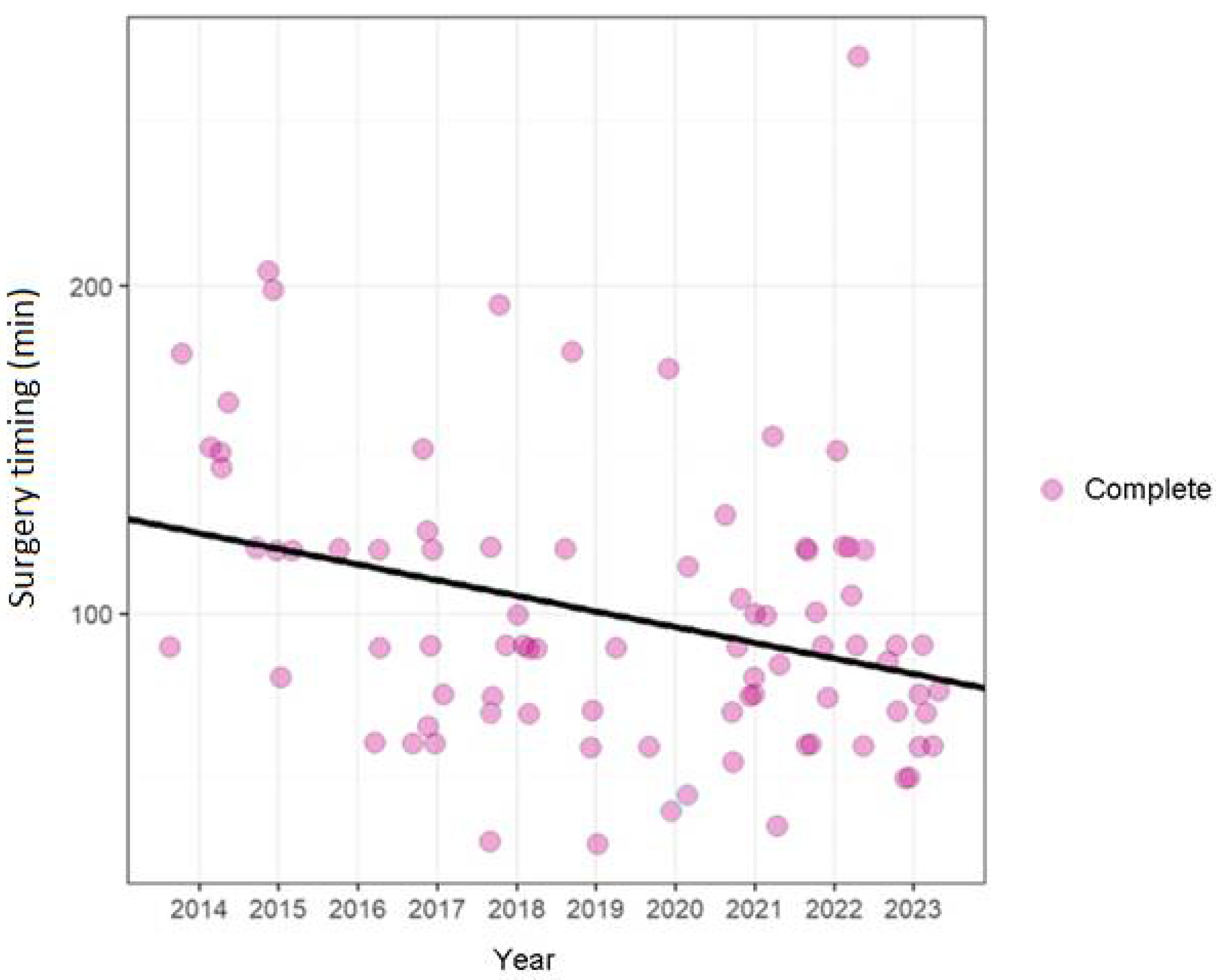

The scatterplot (

Figure 6) displays the duration of surgery over the time period considered (from 2014 to 2023): the vertical axis represents the time of surgery (in minutes) and the horizontal axis shows the year in which the interventions were performed.

Each dot represents a surgery, with the size and color indicating the completion category. The black trend line represents linear regression, which helps visualize the change in surgery duration over time. It is useful for analyzing any trends over time in surgery duration, taking into account the type of surgery. n this scatterplot the points have been slightly shifted to display the entire cohort, given the high number of patients with equal operating time. It is noted that there is a significant decrease in surgical time over the years.

Discussion

The IFNM supports the surgeon in identifying the FN, reporting any accidental manipulation or stimulation, tracing its path and providing indications on the possible functional outcome of the FN after the operation. It is believed that such monitoring helps to reduce temporary paralysis, promptly warning of potential damage such as stretching or compression, which could compromise the nervous microcirculation. [

10,

11]

Although there are several international guidelines and consensus statements on the clinical use of IFNM for the recurrent laryngeal nerve IORLNM) e in otologic and skull base surgery [

12,

13,

14], no such standardized protocols on the use and interpretation of IFNM have been published to date in parotid gland surgery and even less in submandibular gland surgery.

Infact regarding IFNM in submandibular gland surgery, the current literature does not provide conclusive evidence demonstrating a direct link between the use of this monitoring and the reduction in the incidence of post-operative deficits, particularly of the MMB [

15]. Although some studies have suggested that monitoring may be useful in protecting the FN [

7,

16,

17], the available results are not sufficient to establish a statistically significant correlation. Numerous investigations have shown that postoperative rates of facial paresis may be similar for patients undergoing intraoperative facial nerve monitoring and for those who are not.

It is important to note that the authors excluded patients with primary or metastatic malignant tumors of submandibular gland from the study because they can infiltrate the branches of the FN requiring a radical surgical strategy.

Both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses conducted in the study did not highlight a statistically significant correlation between the use of IFNM and a significant reduction in the risk of FN deficiency after submandibular sialodenectomy (OR = 0.87, 95% CI from 0.34 to 2.22 and p = 0.8 in univariate logistic regression, OR = 0.73, 95% CI from 0.26 to 1.96 and p = 0.5 in multivariate logistic regression).

This study presents the most relevant evidence in the scientific literature demonstrating a higher percentage of patients undergoing IFNM (G2) reported a complete resolution of deficits in a short time than G1 patients as well as a statistically significant reduction in surgical timing.

In particular, it was seen that in G2 the percentage of patients with post-operative deficit at three months decreased from 22% (11 patients) of the total patients of G2 (51) to 2% (1 patients), while in G1 the percentage decreased from 24% (12 patients) of the total patients of G1 (50) to 14% (7 patients) and after six months, grade II dysfuction persisted in five patents of G1.

Furthermore, univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses found that IFNM was associated with a statistically significant reduction in surgical timing, with an average of approximately 19 minutes less than operations performed without monitoring, as evidenced by univariate linear regression (Beta = -19, 95% CI -37 to -0.16 and p = 0.048). This surgical timing saving could represent a concrete advantage in terms of operative efficiency, potentially reducing the risk of complications related to longer surgical timing. A longer surgical timing was observed compared to non-smokers (always statistically significant with a p-value of 0.008), suggesting that smoking status may influence the duration of the intervention (Beta = -0,32, 95% CI -0,08 to -0.55 and p = 0.008).

Of course the design of prospective study will allow to identify the potential benefits of IFNM also in the surgery of benign pathology of the submandibular gland in reducing the severity of the lesions and shortening the recovery period from transient post-operative paralysis.