1. Introduction

Mandibular tori are asymptomatic bulges of the jawbone that commonly occur between the canines and premolars on the lingual side of the mandible [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The prevalence of mandibular tori varies by region and age, with incidences of 5.2%-18.8% in Europeans [

5,

6], 12.1% in Africans [

7], and 9.2–29.9% in Asians [

5,

8], with most cases affecting people aged 30–50 years. In Japan, 26.5% of the studies on mandibular tori targeted people over 60 years of age, whereas 58.3% of the studies targeted young dentate adults [

9,

10]. Mandibular tori usually present with few symptoms; therefore, treatment is usually limited to follow-up and observation. However, depending on their size, shape, and area of occurrence, they may interfere with dental treatment and daily living [

11,

12]. Specifically, the mandibular tori can interfere with the design or removal of mandibular dentures [

13,

14], and plaque control. Mandibular tori have also been reported to cause sleep apnea [

15,

16]. Surgical resection was performed in these patients. Mandibular torus is usually diagnosed via inspection and palpation of the oral cavity [

17,

18]. X-ray examinations are also commonly used but are not very effective. Indeed, studies and classifications of the morphology of the mandibular tori by Jainkittivong et al., Eggen et al., and Monica et al. made diagnoses based on inspection and palpation during intraoral examinations [

19,

20,

21].

However, the mandibular tori are typically covered by oral mucosa. Therefore, when a mandibular torus is located beneath the mucosa lining the floor of the mouth or develops into a pedunculated shape, accurately characterize the protuberance becomes difficult. Incorrect determination of the torus shape may lead to inaccurate information being obtained during preoperative examination prior to surgical resection [

22,

23] and treatment planning or improper setting of the incision line. Therefore, developing an appropriate method to accurately determine the location, size, and morphology of mandibular tori is essential. We utilized the computed tomographic (CT) image analysis software SIMPLANT

® by Dentsply Sirona, which offers accurate three-dimensional image construction and detailed image resolution. This software, frequently used in treatment planning for dental implants, can recognize the three-dimensional morphology of hard tissue and calculate bone volume and density [

24,

25]. This information is related to the position and size of the gingival incision used for flap deployment during the resection of the mandibular torus.

This study aimed to provide a clinically relevant reference for determining the necessity of investigation and interventions in the treatment of mandibular tori and to obtain information that would help in concluding whether the presence of teeth and occlusal forces is associated with the appearance of mandibular torus. To date, no studies have applied CT analysis software to large-scale surveys of the incidence, size, and shape of mandibular tori. Therefore, we used a CT image analysis software to investigate the location, size, morphology, and bone density of the mandibular tori in more detail. The investigators hypothesized that this large-scale investigation, using CT analysis software, would enable a more accurate epidemiological study regarding the shape, size, and location of mandibular prominences, especially when located deep in the floor of the mouth. The specific aim of this study was to investigate the appearance rate of mandibular tori by morphological type, accurate size, location in terms of vertical position, and CT values, which are difficult to diagnose accurately by visual inspection of the oral cavity alone. Based on this information, they determined the depth of the mandibular tori at which oral functioning was affected and the likelihood of protuberance during resectioning. Another aim of this study was to compare the tooth loss and residual occlusal support rates.

4. Discussion

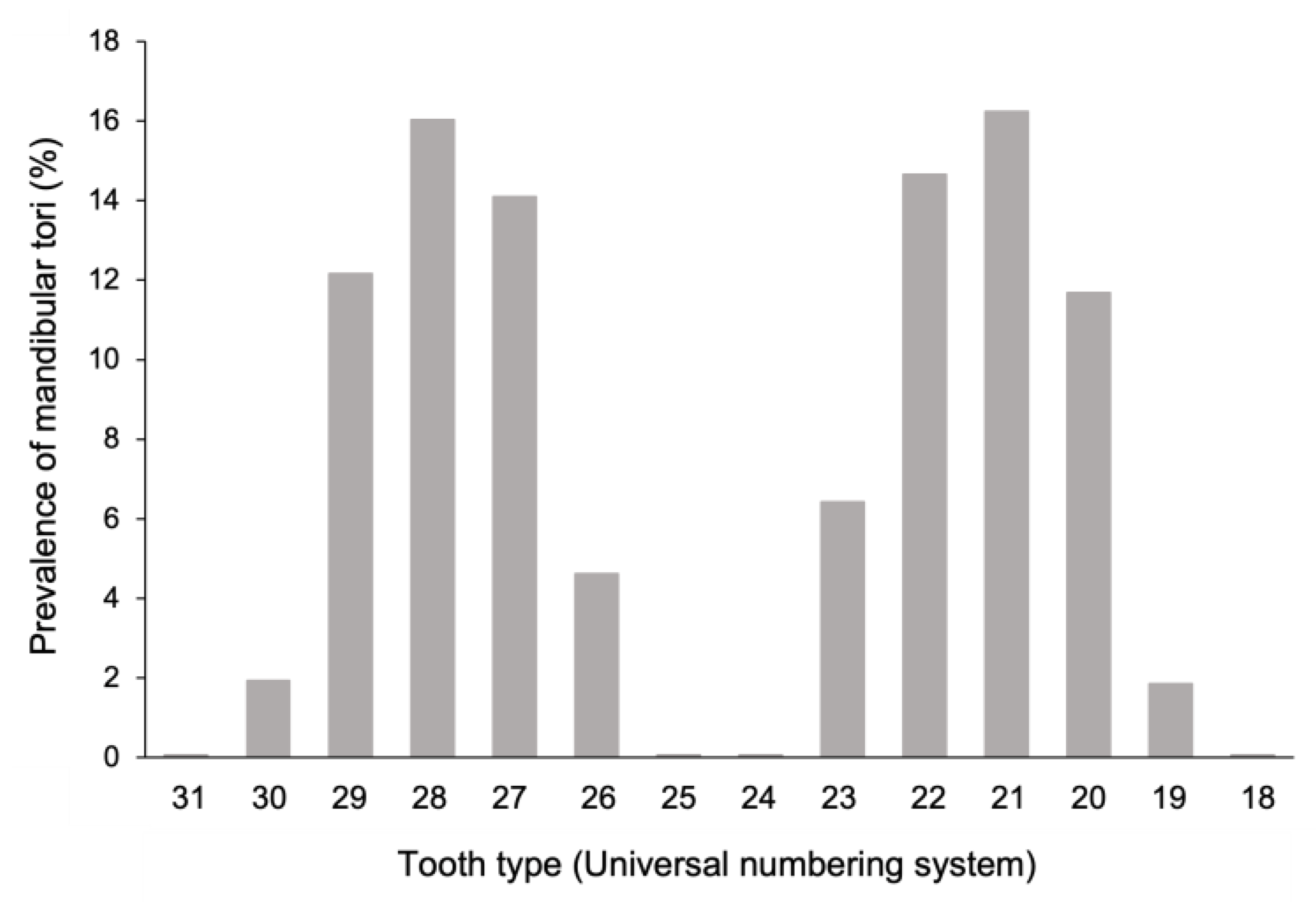

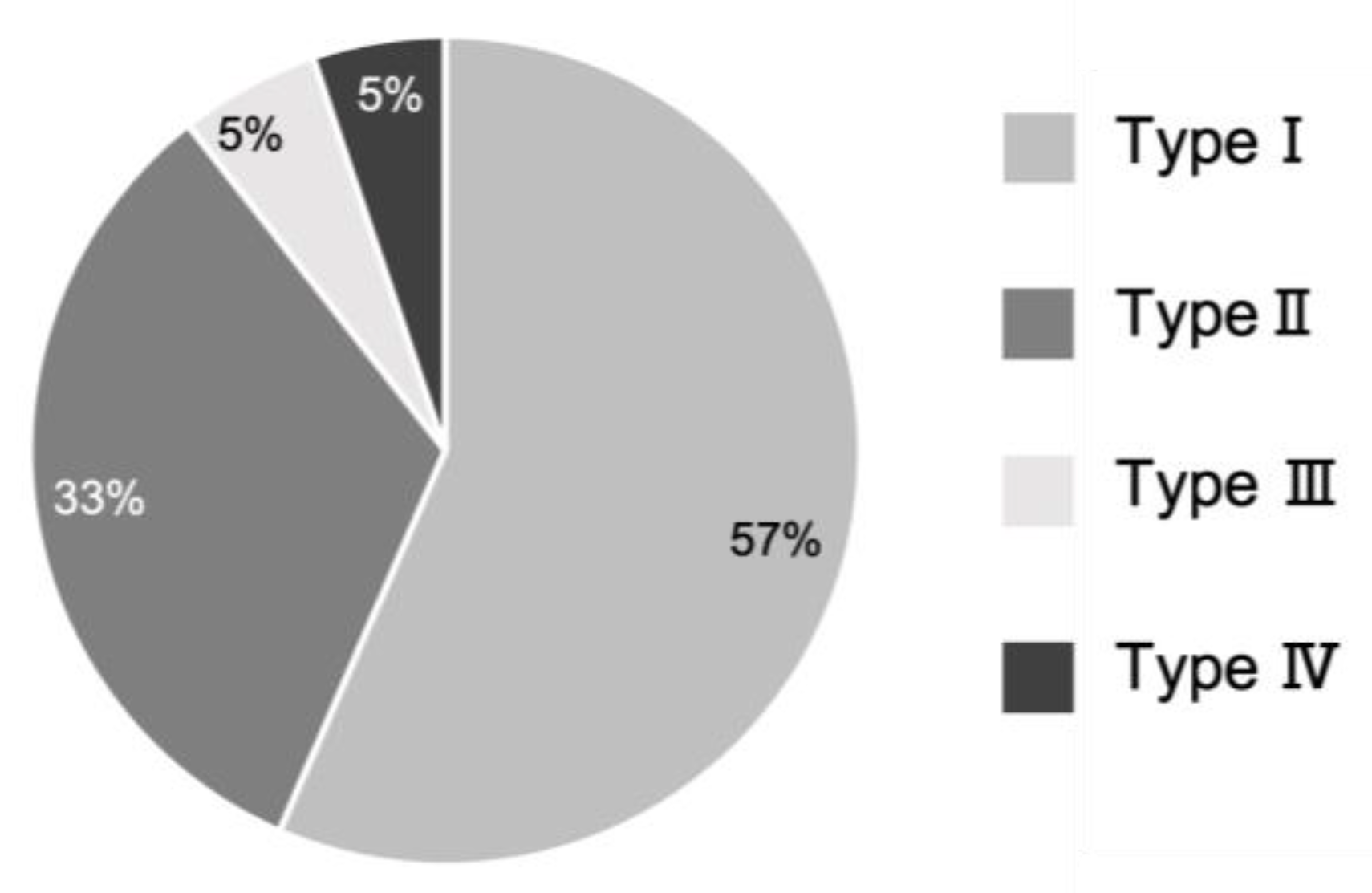

This study aimed to evaluate the incidence, site of occurrence, shape, volume, and CT values of mandibular tori in 1,176 patients using CT analysis software. The main reason is the difficulty in accurately characterizing the mandibular ridge when it is beneath the mucous membrane of the floor of the mouth; therefore, detailed characterization by three-dimensional analyses is considered necessary. In this study, three-dimensional analyses were performed using CT analysis software to obtain accurate information regarding the shape, size, and location of each mandibular torus at the bone level. Of all tori, 10.5% were of the

pedunculated type. Regarding vertical position, more than 80% of the lesions were localized in the alveolar bone. The incidence was the highest in the first premolar region, accounting for 32.3% of all cases. The most prominent mandibular tori had a bulge of 10.5 mm, and a maximum volume of 1826 mm

3. Accurately diagnosing this condition through visual inspection of the oral cavity alone is challenging. However, mandibular tori can be excised relatively easily by resecting them at the base. However, if the torus is not pedunculated or is located from the alveolar bone area to the body of the mandible, a larger incision surface area is required to fully resect the torus, which increases the technical difficulty of the procedure and burden on the patient. The extent of gingival mucosa required for resection may vary from case to case. Therefore, the results of our study emphasize the importance of using CT analysis software for preoperative examinations when performing mandibular torus resection. A notable component of this study was that the CT analysis software was applied to over 1,000 participants. This allowed us to accurately classify the size and morphology of the tori and compare the bone density between the torus and healthy bone in the same patient. Jean-Daniel et al. performed a morphological analysis of the mandibular tori using micro-CT [

27]; however, the sample size was very small (n=16). Conversely, in this study, morphological analysis via CT was performed on 334 patients with mandibular tori. Our larger sample size increased the statistical validity of our findings. In a systematic review of the incidence of mandibular tori by Garcia-Garcia et al. [

1], all 13 cited studies used visual inspection and palpation to diagnose mandibular tori [

6,

7,

18,

19,

26,

28]. Thus, no previous studies have investigated the incidence and common sites of mandibular tori in a large patient pool using CT analysis software. Furthermore, in our image analysis pipeline, we extracted and calculated only the volumes of the mandibular tori. In previous studies, most methods for estimating torus size involved measuring the distance to the maximum bulge point of the torus [

10,

13,

17,

21,

27]. In this study, in addition to the measurement method, mandibular tori were digitally extracted, and the volume of this portion was calculated. Therefore, this method proved valid for determining the scale of the entire mandibular torus. CT image analysis can also be used to accurately determine the bone density using CT values [

25,

29]. Youna et al. investigated the thickness and CT values of the mandibular tori using CT image analysis [

24]. However, in our study, we compared the densities of the mandibular tori and healthy bones. Therefore, from a radiological perspective, we could discern whether each mandibular torus was merely a swelling of the cortical bone or a tumor with a distinct tissue structure.

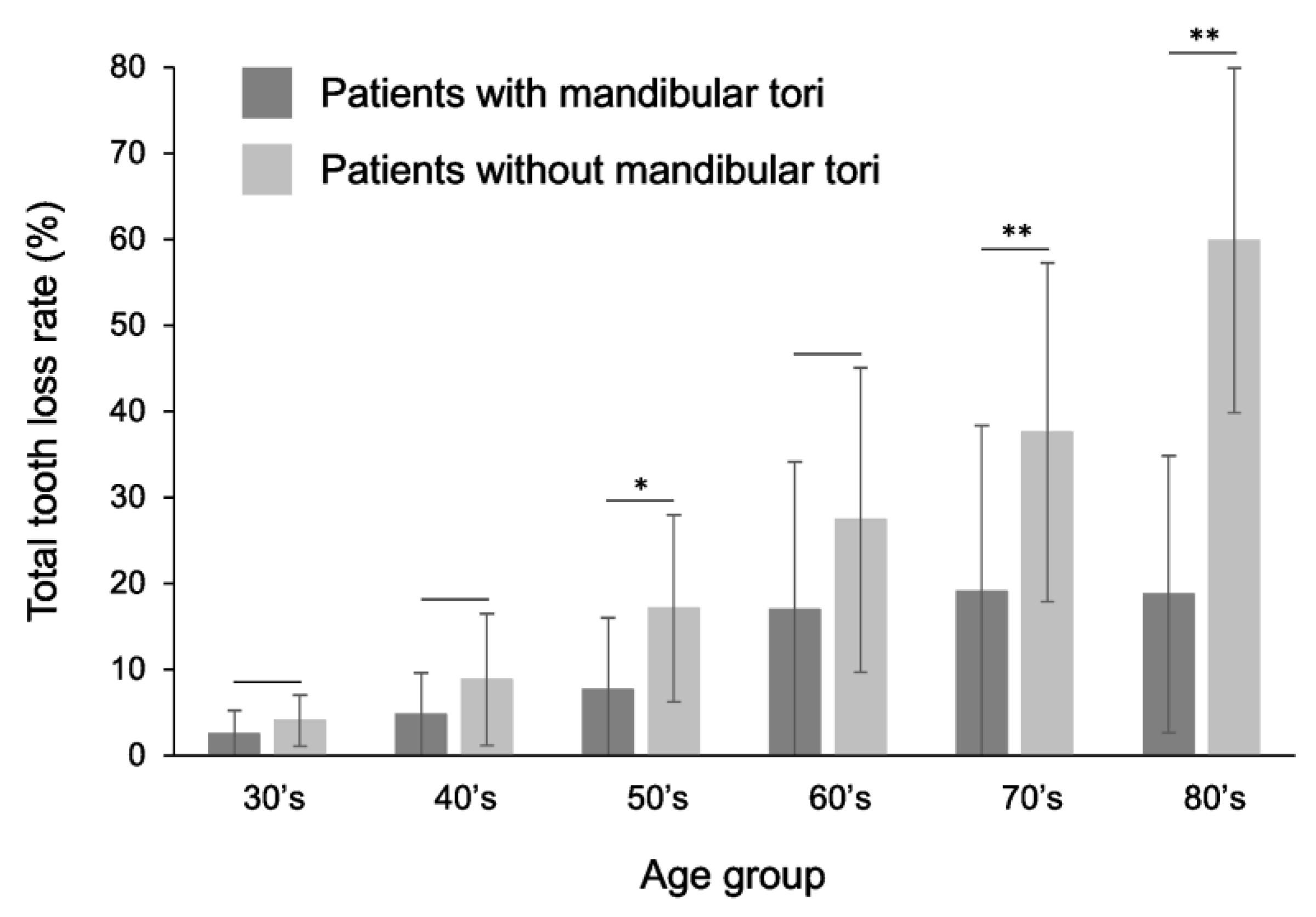

In this study, the mandibular torus occurred within the range of the canine to the premolar, and over 80% of cases occurred within the range of the alveolar bone. In addition, the rate of tooth loss was significantly lower in patients with mandibular torus in their 40s and older. This suggests that the occurrence of mandibular torus may be closely related to the presence of the remaining teeth and alveolar bone. Consequently, the conclusions of previous studies [

6,

27] were confirmed more concretely through this survey. The older the age group, the greater the difference in the proportion of missing teeth between patients with torus and healthy subjects. This may be because the proportion of people with missing teeth was low in younger age groups; therefore, the difference in the proportion of missing teeth between torus patients and healthy subjects was small, and the proportion of people with missing teeth generally increased as the age group increased. The rate at which the occlusal support relationship was maintained was significantly higher in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy subjects, suggesting a relationship between the development of mandibular torus and occlusal support. Previous research has shown that the occurrence of mandibular torus is significantly related to the wear of the remaining teeth and position of the occlusal contacts [

9], which may support the findings of this study.

The novelty of this study is that it examined the relationship between the appearance of the mandibular torus and the remaining teeth when examining all tooth types as the target area and when examining only the canine to premolar area, where the mandibular torus is most likely to appear. As a result, similar trends were observed when examining the entire oral cavity, and when examining only the canine to premolar area, a statistically significant difference was observed. This tendency was observed both when comparing the appearance rate of the mandibular torus with the rate of tooth loss and when comparing the appearance rate of the mandibular torus with the presence of occlusal support. In other words, it was suggested that similar results were obtained when examining the presence or absence of remaining teeth in the area where mandibular torus is most likely to appear and when examining the presence or absence of remaining teeth in the entire oral cavity. This can also be explained by the importance of examining the number of remaining teeth and the presence or absence of occlusal relationships in the entire oral cavity. Therefore, investigating the occurrence rate of mandibular torus and the number of remaining teeth in the entire oral cavity will support the findings of previous studies that have pointed out the possibility of a relationship between mandibular torus and the remaining teeth, occlusal relationship, and biting force [

6,

30]. Recent studies have explored the relationship between parafunctional activities, such as bruxism, and the incidence of mandibular torus [

8,

31]. Previous reports have shown that tooth loss eliminates the stimulation of the alveolar bone, causing a loss of bone width and height [

32,

33]. A follow-up study of edentulous patients showed that the mandible underwent greater resorption than the maxilla [

34].

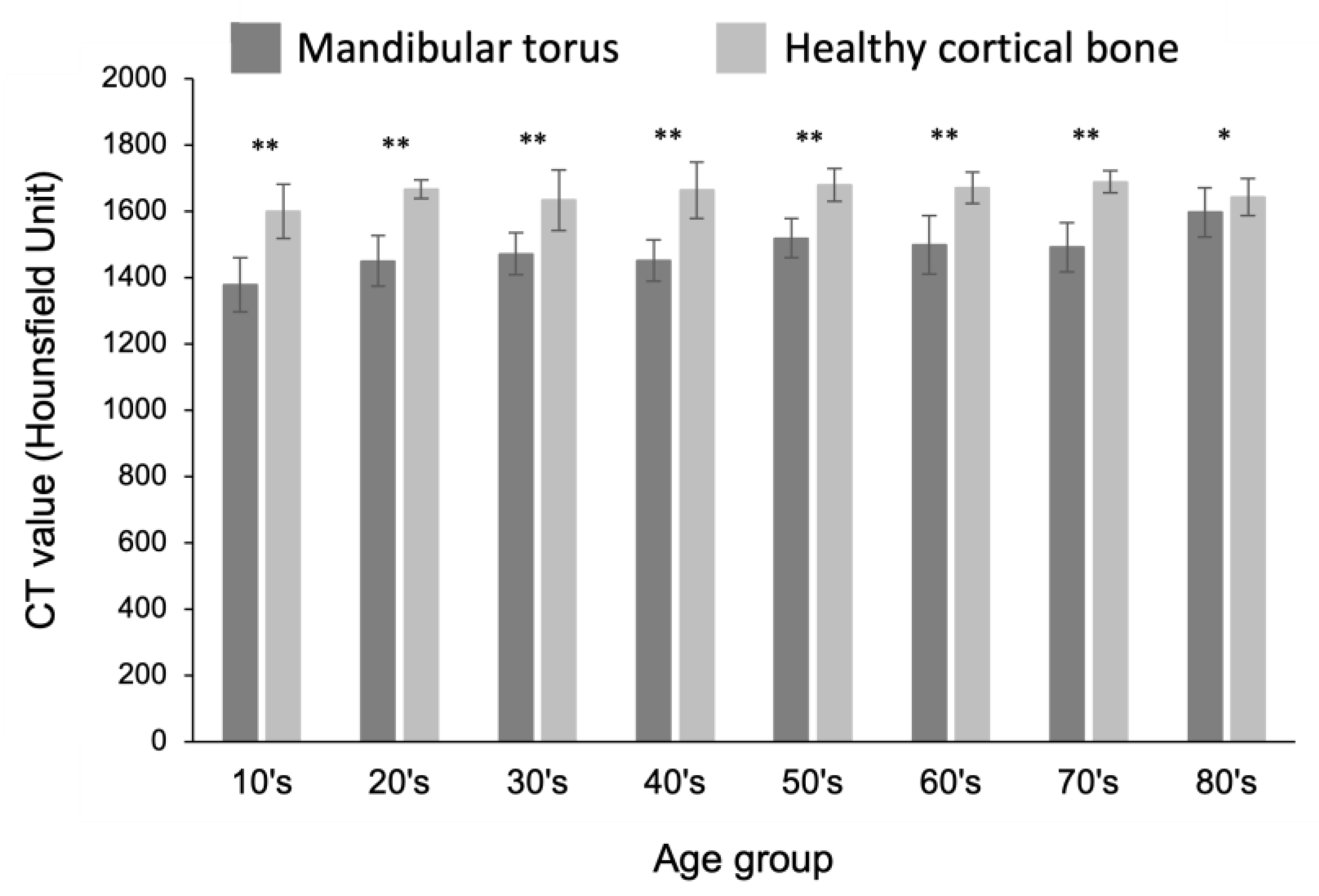

The excised mandibular tori are usually discarded. However, in recent years, they have also been used for the pretreatment of prosthetics at sites scheduled for implantation surgery [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. In addition, some case reports have described the use of excised tori as autogenous bone grafts to treat the vertical alveolar bone density, which is important for determining the extent of bone recovery from autogenous bone grafting. Histological evaluation of the mandibular tori has been reported to indicate autologous bone graft material [

40]. However, a detailed radiological investigation of mandibular tori has not yet been conducted. Hounsfield unit (HU) is a radiographic measure of bone density [

29]. The CT values of the mandibular tori were significantly lower than those of the healthy cortical bone in each age group; however, the average value was over 1350 HU. This corresponds to “Grade: D1” (1250 HU or more), considered the most predictable in Misch’s bone quality classification [

29]. Therefore, it was suggested that the mandibular tori have densities that are considered normal on radiography. Thus, our findings provide a scientific basis for the application of mandibular tori as bone graft material.

The retrospective design of this study, which used data collected from past patient records and CT images, may have introduced patient selection bias and limited the reliability of the data collection methods and patient characteristics. In addition, the study included patients who underwent plain mandibular CT scans, which limits its generalizability and excluded cases of mandibular tori diagnosed using methods other than CT. Thus, the results do not reflect the true prevalence of mandibular tori. Furthermore, a monomodal diagnostic approach does not consider other diagnostic methods or clinical evaluations that may provide complementary information. In addition, in cases in which CT scans were performed within a short period after the loss of the remaining teeth located at the site where the mandibular torus developed, the mandibular torus was considered to have developed at the site where the teeth were missing. Therefore, the validity of analyzing the relationship between the presence of mandibular torus and the presence of remaining teeth or the presence or absence of occlusal support may be reduced. However, due to the limited number of studies employing this research design, this information is important in considering the possibility that mechanical factors, such as the presence of remaining teeth and occlusal support, are involved in the development and maintenance of the mandibular torus. Furthermore, the number of remaining teeth and the presence or absence of occlusal support in the area from the canine to the premolar, which is the most common site for mandibular torus, represents a highly novel aspect of this study.

This study allowed us to investigate the shape-positional relationship of the mandibular tori in more detail. More detailed information is required to understand this relationship, and the importance of CT analysis in software-based investigations has been emphasized. Furthermore, although radiological bone density was evaluated in this study, we need to conduct further histological evaluations and investigate the differences in constituent cells and gene expression when considering the application of excised mandibular tori as an autogenous bone graft material.

Using a CT analysis software, we obtained detailed information on the shape, size, and location of the mandibular tori. Approximately 10% of all cases include pedunculated tori, the morphology of which is difficult to characterize by visual inspection and palpation alone. This emphasizes the importance of preoperative testing and epidemiological surveys using CT image analysis software. The bone density of the mandibular tori was significantly lower than that of the healthy cortical bone; however, the average bone density was over 1350 HU, which is sufficient for implant placement. Thus, the results of this study reinforce the scientific validity of using resected tori as bone graft material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T. M. and K. S.; methodology, K. S.; software, K. M.; validation, K. S., K. M., and Y. M.; formal analysis, K. S. and K. M.; investigation, K.S., K.M., and Y. M.; resources, T. K.; data curation, K. S.; writing—original draft preparation, K. S.; writing—review and editing, K.S., and T. M.; visualization, K. S.; supervision, T. M.; project administration, K. S.; funding acquisition, T. M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

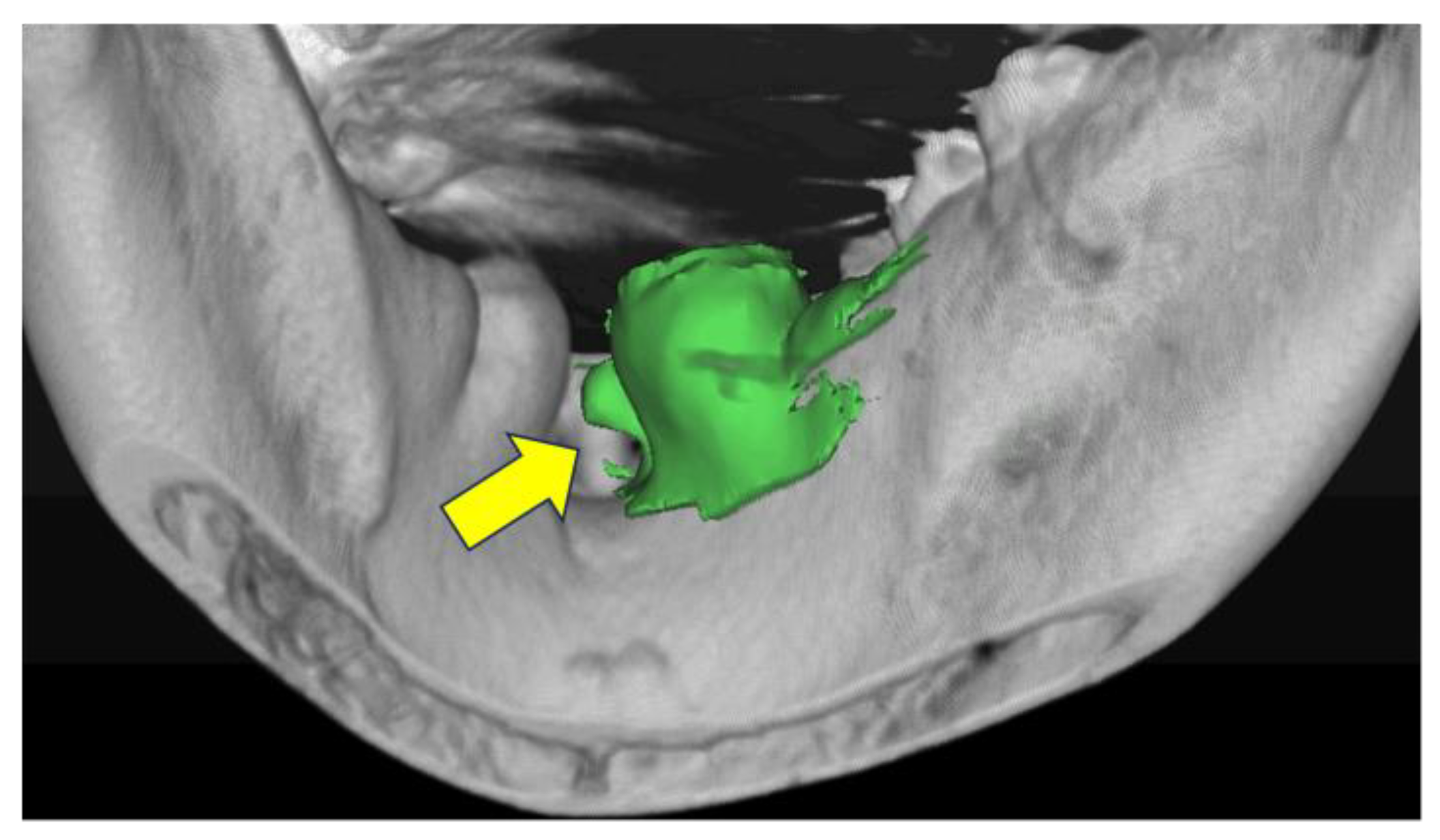

Figure 1.

Identification and analysis of mandibular tori using computed tomography analysis software. The arrow points to the identified mandibular tori. This allows for the evaluation of morphology, size, bone density, etc., at specific locations.

Figure 1.

Identification and analysis of mandibular tori using computed tomography analysis software. The arrow points to the identified mandibular tori. This allows for the evaluation of morphology, size, bone density, etc., at specific locations.

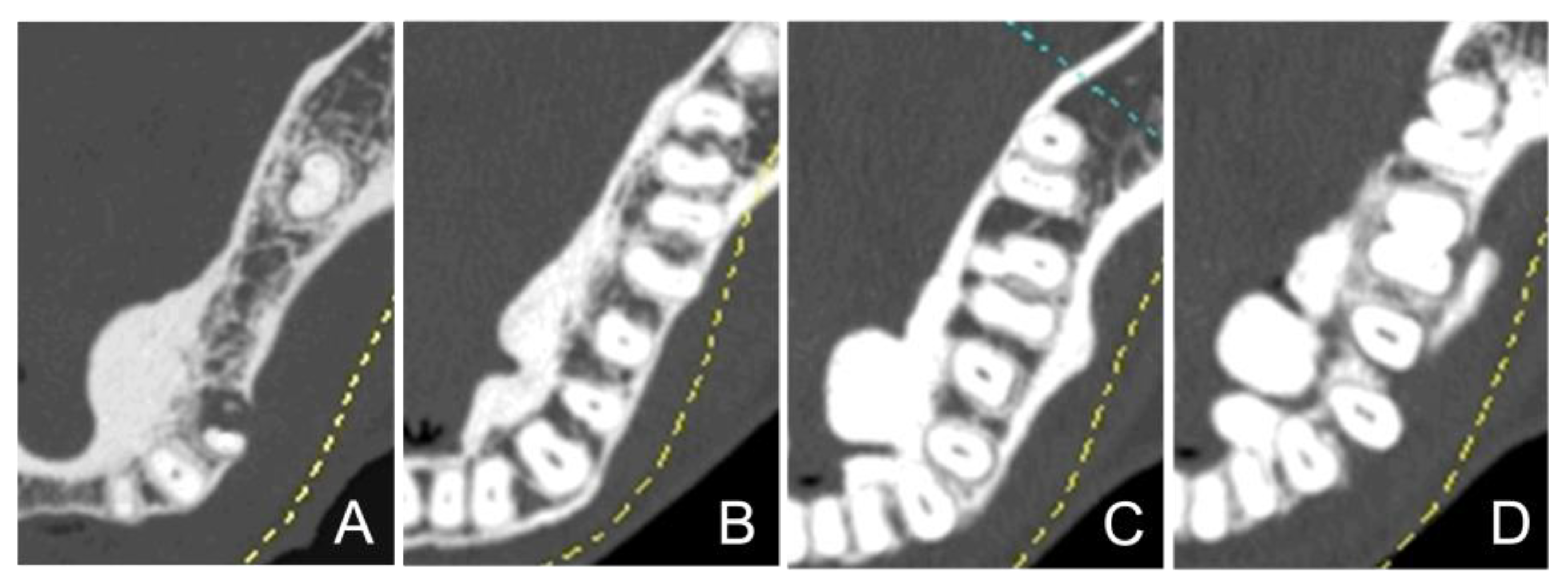

Figure 2.

Morphological classification of mandibular tori by computed tomography images. Mandibular tori were categorized into four types based on their morphology. The examples are displayed in sequence from Type I to Type IV, starting from the left. Type I: Monocystic and stemless (A). Type II: Multivesicular and stemless (B). Type III: Monocystic and pedunculated (C). Type IV: Multivesicular and pedunculated (D).

Figure 2.

Morphological classification of mandibular tori by computed tomography images. Mandibular tori were categorized into four types based on their morphology. The examples are displayed in sequence from Type I to Type IV, starting from the left. Type I: Monocystic and stemless (A). Type II: Multivesicular and stemless (B). Type III: Monocystic and pedunculated (C). Type IV: Multivesicular and pedunculated (D).

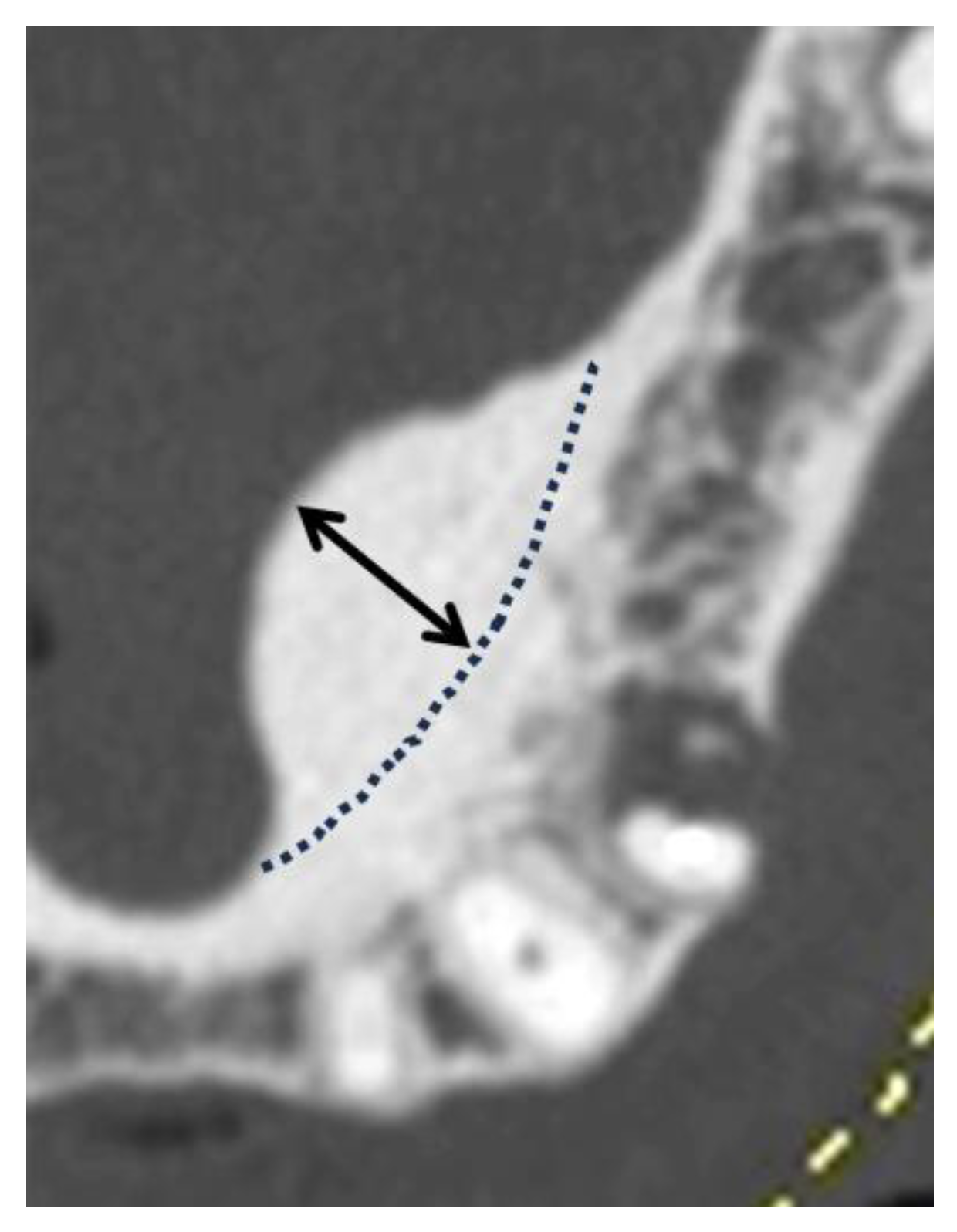

Figure 3.

Measurement points for determining the size of mandibular tori. The distance from the outline of the normal cortical bone (represented by the dotted line in the figure) to the point of maximum protrusion (indicated by the double-headed arrow) was measured. This distance is defined as the size of mandibular tori.

Figure 3.

Measurement points for determining the size of mandibular tori. The distance from the outline of the normal cortical bone (represented by the dotted line in the figure) to the point of maximum protrusion (indicated by the double-headed arrow) was measured. This distance is defined as the size of mandibular tori.

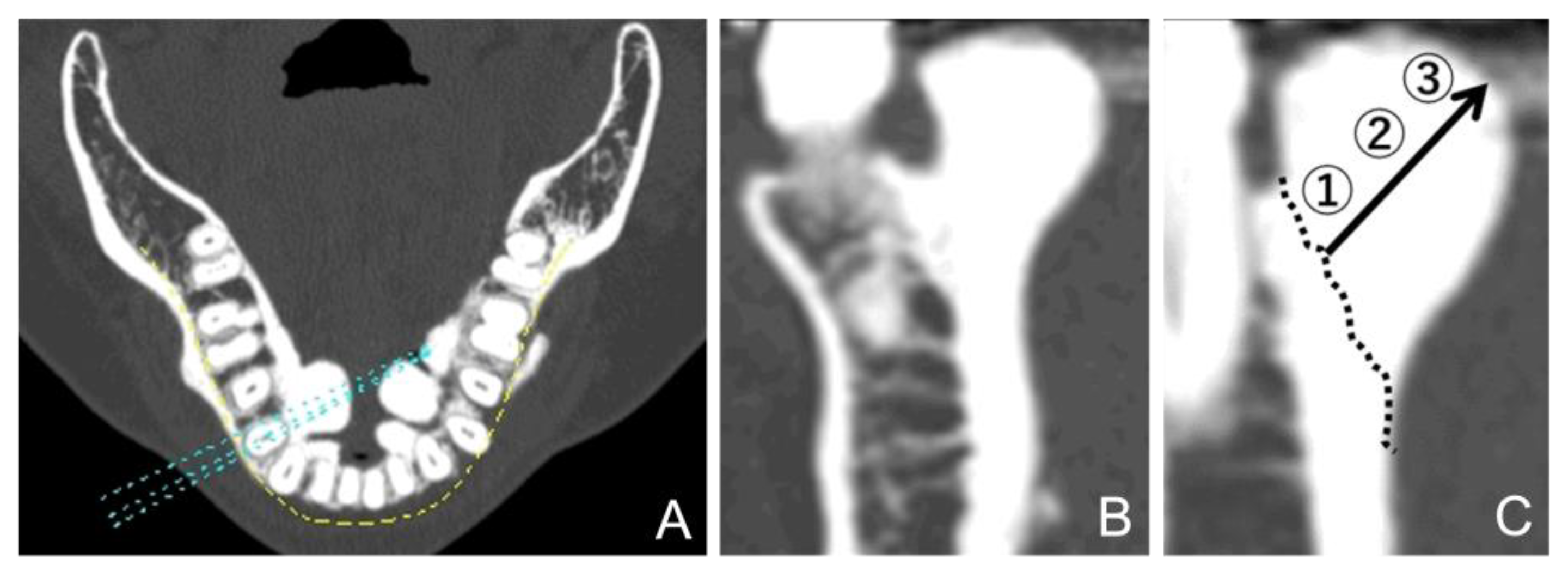

Figure 4.

Computed tomography (CT) value calculation of mandibular tori. (A) A panoramic curve set in the horizontal section of the CT image. (B) A cross-sectional surface in the vertical direction. (C) After setting the boundaries of the expected anatomical cortical bone (dotted line), three areas were defined: 1: The base area, 2: the central area, and 3: the maximum bulge area.

Figure 4.

Computed tomography (CT) value calculation of mandibular tori. (A) A panoramic curve set in the horizontal section of the CT image. (B) A cross-sectional surface in the vertical direction. (C) After setting the boundaries of the expected anatomical cortical bone (dotted line), three areas were defined: 1: The base area, 2: the central area, and 3: the maximum bulge area.

Figure 5.

Prevalence of mandibular tori compared by tooth type area. Values on the horizontal axis indicate the tooth types, presented using the universal numbering system. The vertical axis shows the prevalence (%) of mandibular tori.

Figure 5.

Prevalence of mandibular tori compared by tooth type area. Values on the horizontal axis indicate the tooth types, presented using the universal numbering system. The vertical axis shows the prevalence (%) of mandibular tori.

Figure 6.

Breakdown of mandibular tori by morphological type. Type I indicate Monocystic and stemless type. Type II: Multivesicular and stemless type. Type III: Monocystic and pedunculated type. Type IV: Multivesicular and pedunculated type.

Figure 6.

Breakdown of mandibular tori by morphological type. Type I indicate Monocystic and stemless type. Type II: Multivesicular and stemless type. Type III: Monocystic and pedunculated type. Type IV: Multivesicular and pedunculated type.

Figure 7.

Comparison of bone density between mandibular tori and healthy cortical bone in each age group. The horizontal axis represents different age groups, while the vertical axis displays the CT value (Hounsfield Unit). A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

Figure 7.

Comparison of bone density between mandibular tori and healthy cortical bone in each age group. The horizontal axis represents different age groups, while the vertical axis displays the CT value (Hounsfield Unit). A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

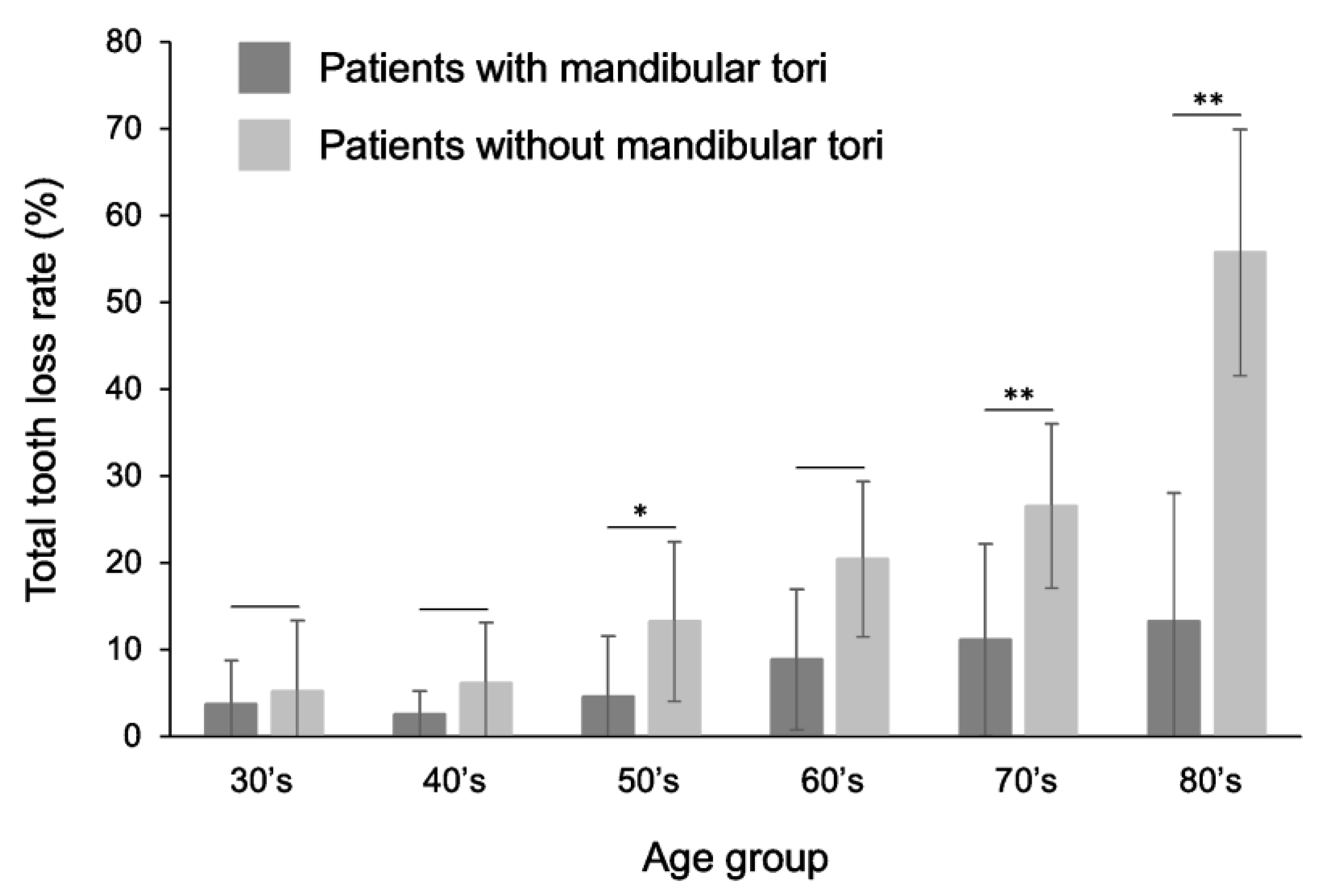

Figure 8.

Comparison of tooth loss rate between patients with mandibular torus and healthy subjects. The rate of tooth loss was lower in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy individuals in all age groups over 30 years old. Statistically significant differences were observed, especially in the 50s, 70s, and 80s. A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

Figure 8.

Comparison of tooth loss rate between patients with mandibular torus and healthy subjects. The rate of tooth loss was lower in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy individuals in all age groups over 30 years old. Statistically significant differences were observed, especially in the 50s, 70s, and 80s. A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

Figure 9.

Comparison of tooth loss rate between patients with mandibular torus and healthy subjects, focusing only on the canine to premolar area. The rate of tooth loss was lower in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy individuals in all age groups over 30 years old. Statistically significant differences were observed, especially in the 50s, 70s, and 80s. A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

Figure 9.

Comparison of tooth loss rate between patients with mandibular torus and healthy subjects, focusing only on the canine to premolar area. The rate of tooth loss was lower in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy individuals in all age groups over 30 years old. Statistically significant differences were observed, especially in the 50s, 70s, and 80s. A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

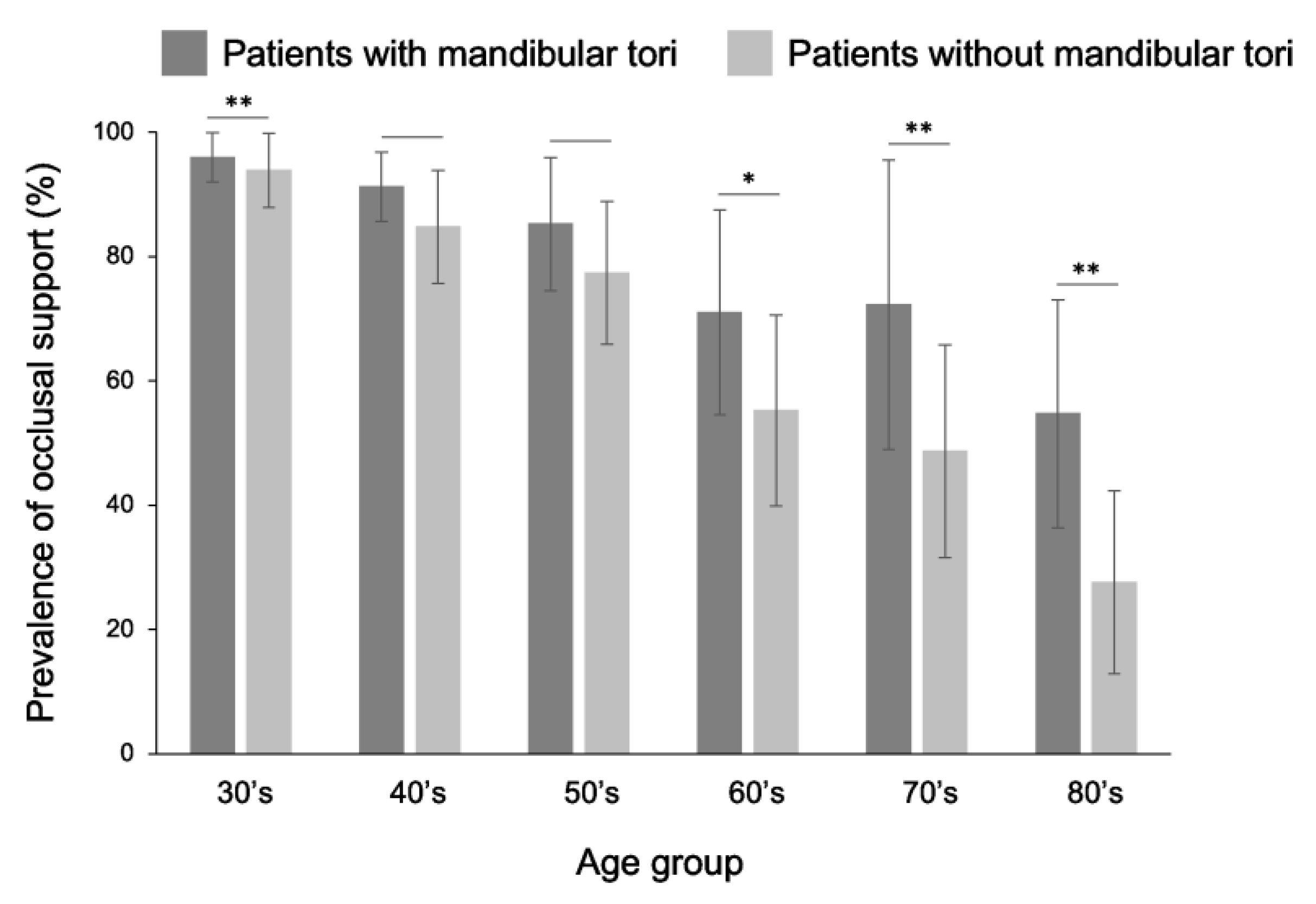

Figure 10.

Comparison of the rate of occlusal support between patients with mandibular torus and healthy subjects. The rate of tooth loss was lower in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy individuals in all age groups over 30 years old. Statistically significant differences were observed, especially in the 50s, 70s, and 80s. A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

Figure 10.

Comparison of the rate of occlusal support between patients with mandibular torus and healthy subjects. The rate of tooth loss was lower in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy individuals in all age groups over 30 years old. Statistically significant differences were observed, especially in the 50s, 70s, and 80s. A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

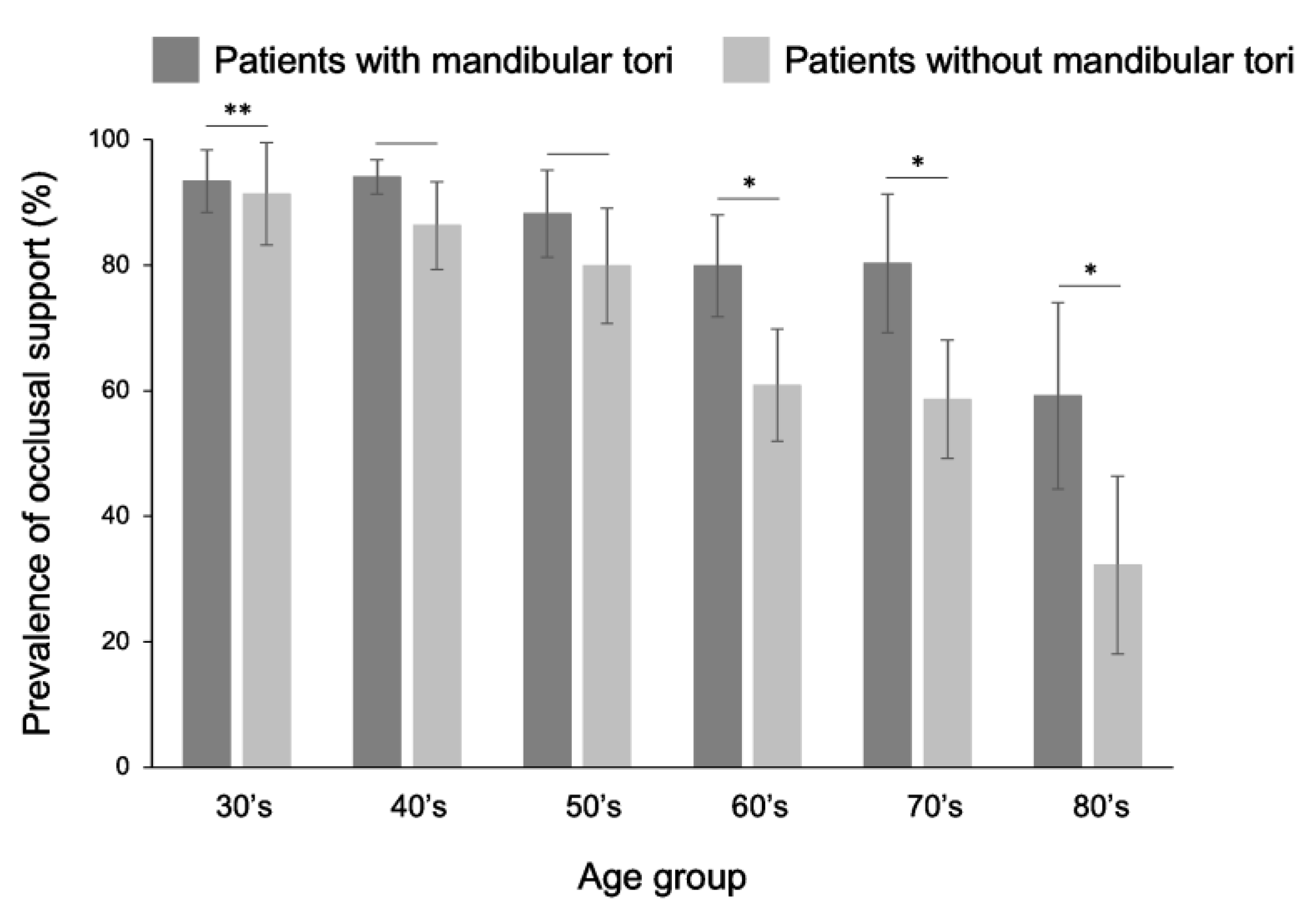

Figure 11.

Comparison of the rate of occlusal support between patients with mandibular torus and healthy subjects, focusing only on the canine to premolar area. The rate of tooth loss was lower in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy individuals in all age groups over 30 years old. Statistically significant differences were observed, especially in the 50s, 70s, and 80s. A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

Figure 11.

Comparison of the rate of occlusal support between patients with mandibular torus and healthy subjects, focusing only on the canine to premolar area. The rate of tooth loss was lower in patients with mandibular torus than in healthy individuals in all age groups over 30 years old. Statistically significant differences were observed, especially in the 50s, 70s, and 80s. A t-test was used for statistical analysis. An asterisk designates network metrics with a significant difference (“*”: p < 0.05, “**”: p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Prevalence of mandibular tori in each age group.

Table 1.

Prevalence of mandibular tori in each age group.

| Age group |

Prevalence (%) |

Number of subjects |

| 10s |

8.2 |

147 |

| 20s |

18.4 |

147 |

| 30s |

39.5 |

147 |

| 40s |

49.7 |

147 |

| 50s |

40.1 |

147 |

| 60s |

33.3 |

147 |

| 70s |

18.4 |

147 |

| 80s and above |

19.7 |

147 |