Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

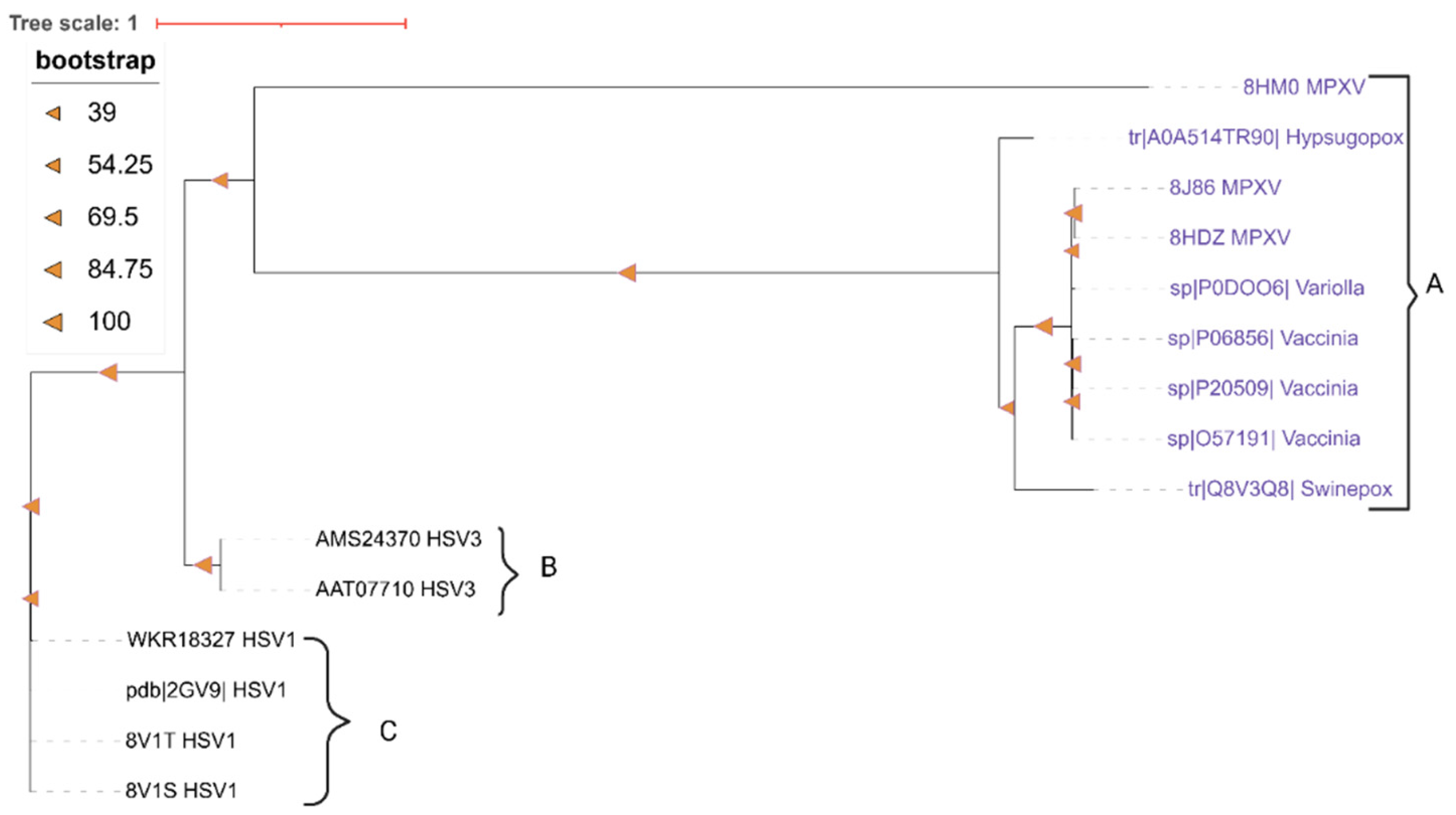

2.1. Concise Comparative Analysis of the DNA Polymerase Enzyme Chain A

2.2. Ligand and Receptor Preparation and Molecular Docking

3. Results

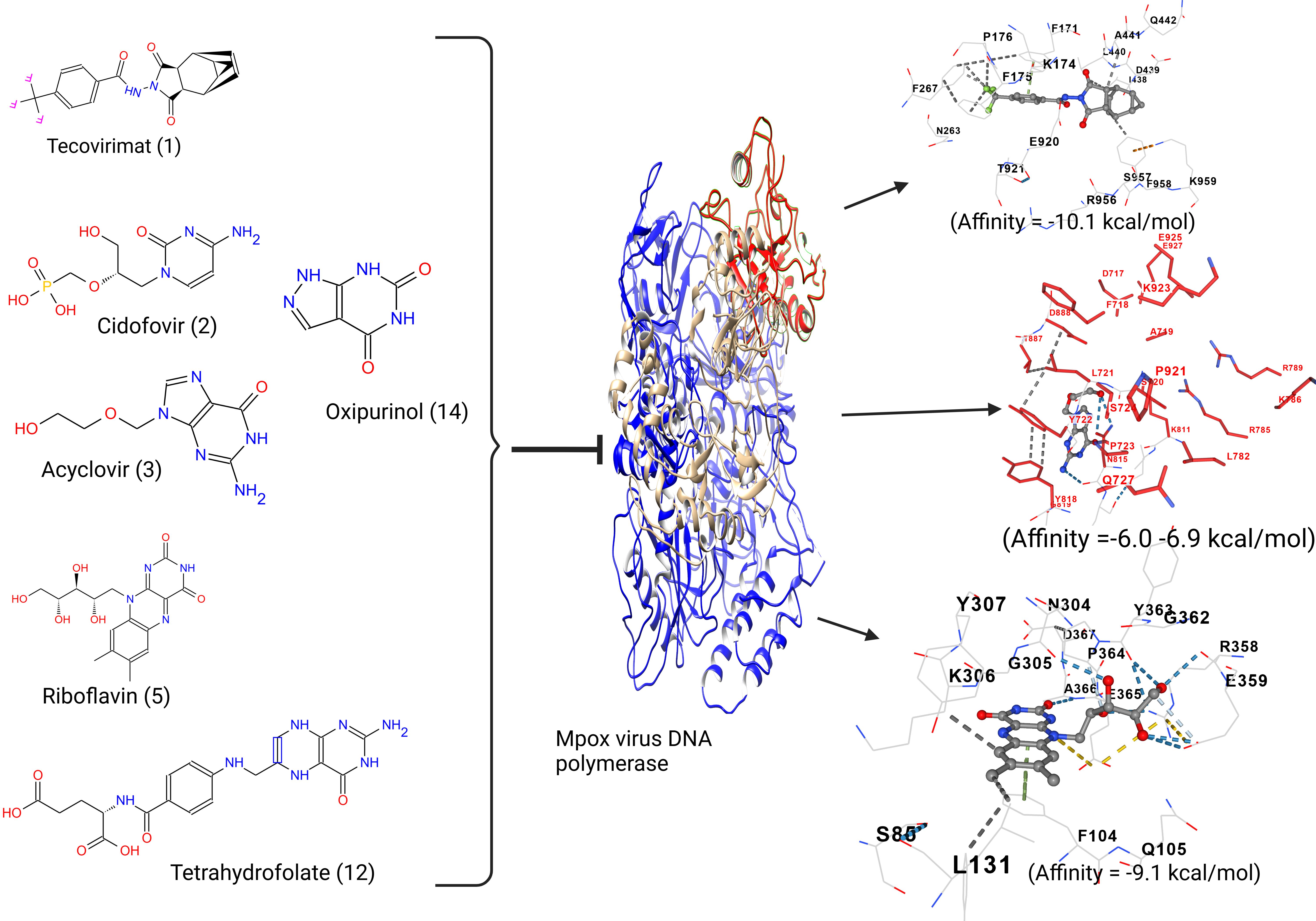

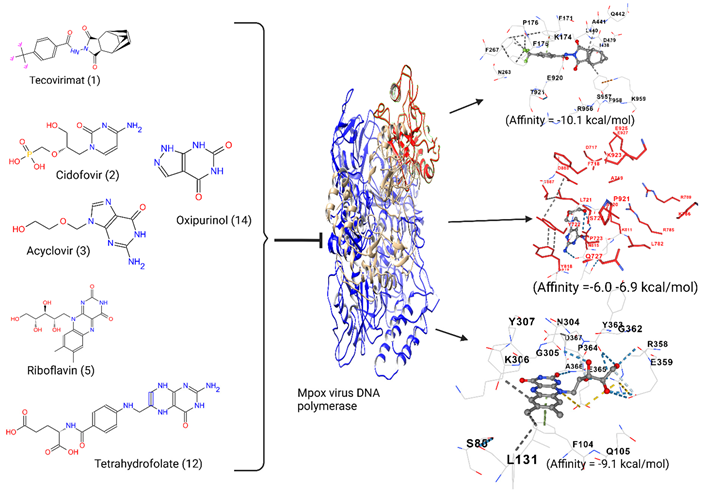

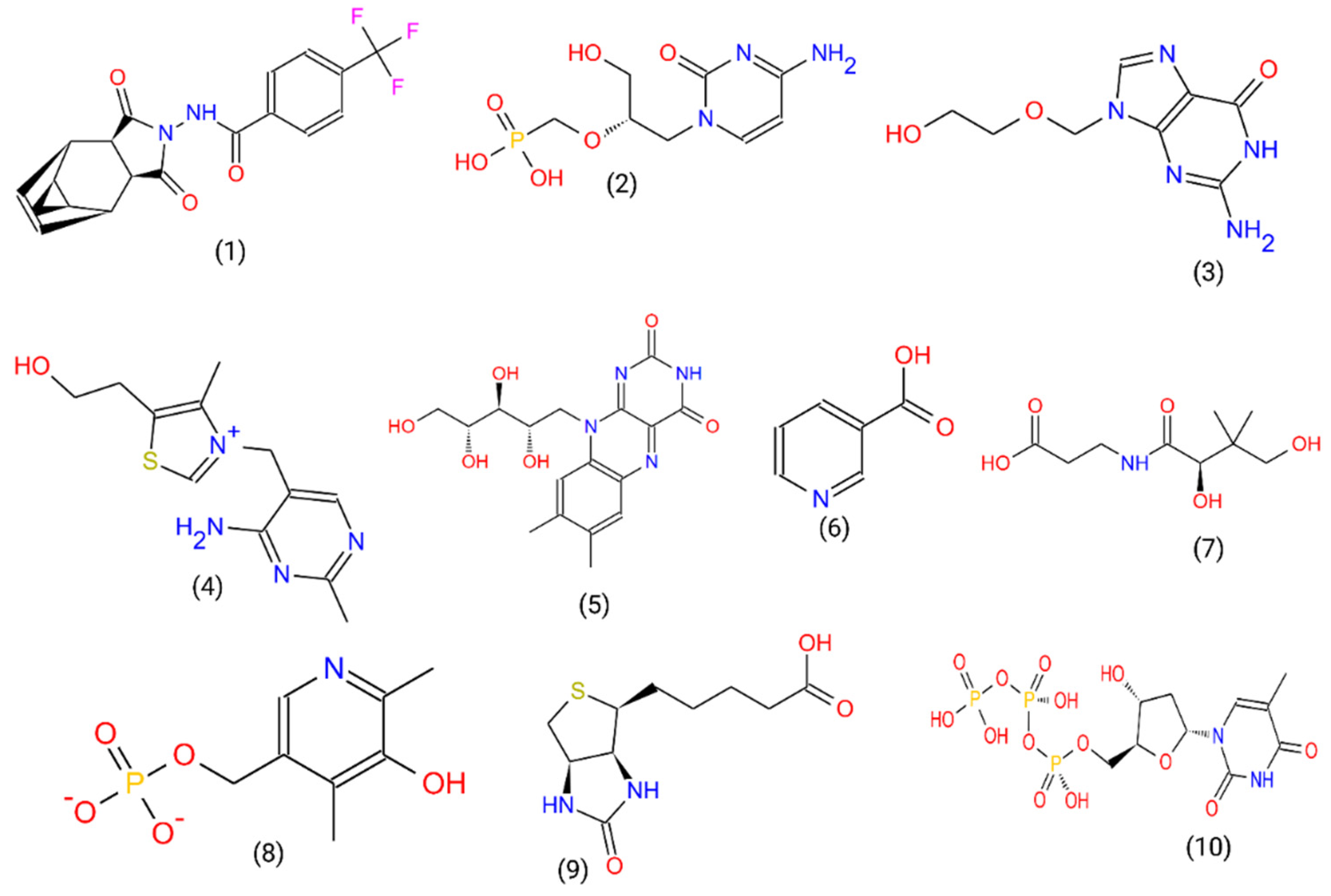

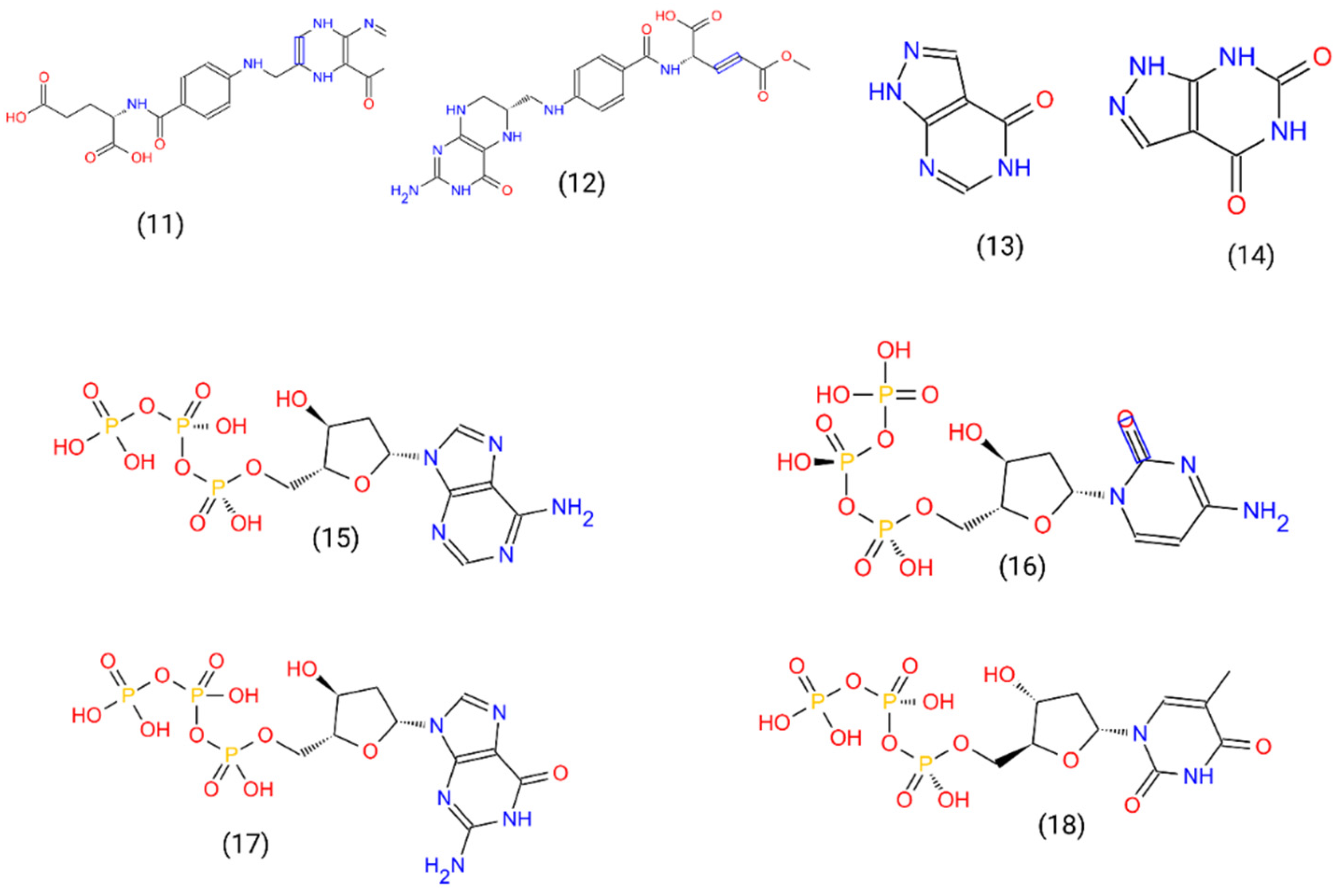

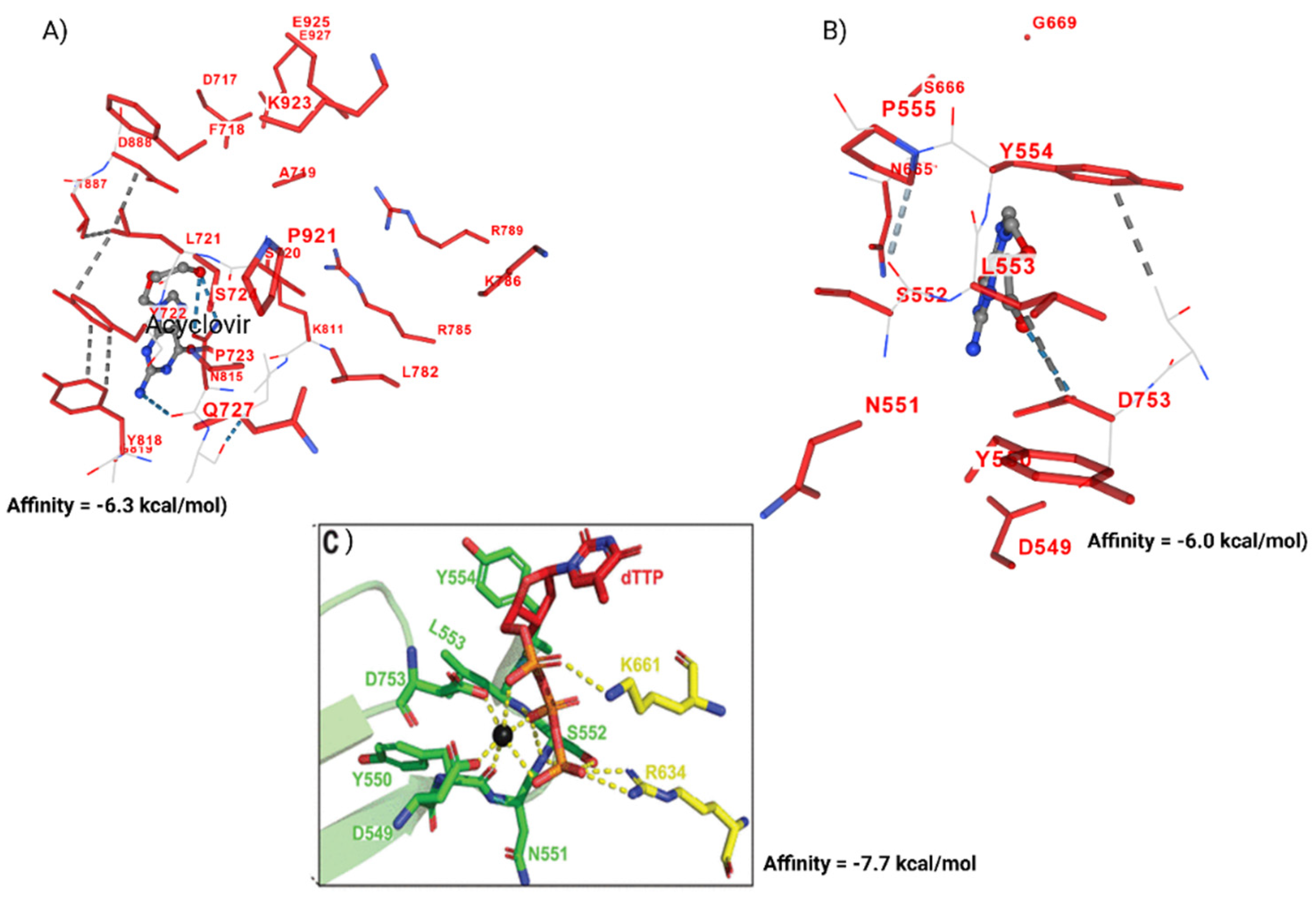

3.1. Acyclovir Interacts with Mpox DNA Polymerase Chain A at the Binding Cavity Specific for dTTP

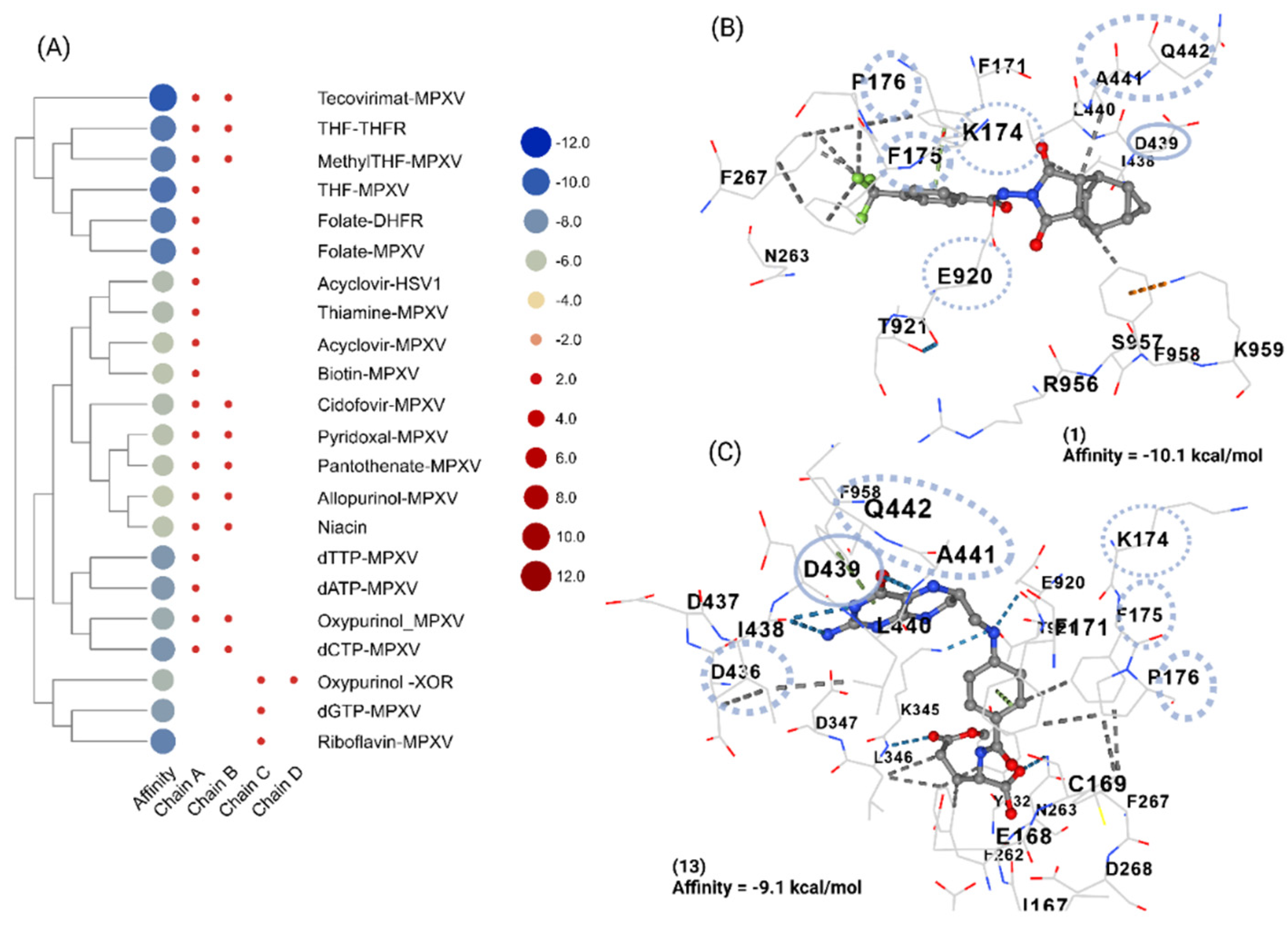

3.2. Oxipurinol, Riboflavin and Folic Acid Express Higher Affinity for Mpox DNA Polymerase Than Cidofovir

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Ethics statement

Conflict of Interest Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Xu Y, Wu Y, Wu X, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Li D, et al. Structural basis of human mpox viral DNA replication inhibition by brincidofovir and cidofovir. Int J Biol Macromol 2024;270:132231. [CrossRef]

- Beiras CG, Malembi E, Escrig-Sarreta R, Ahuka S, Mbala P, Mavoko HM, et al. Concurrent outbreaks of mpox in Africa—an update. The Lancet 2025;405:86–96. [CrossRef]

- Babkin IV, Babkina IN, Tikunova NV. An Update of Orthopoxvirus Molecular Evolution. Viruses 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Yu Z, Zou X, Deng Z, Zhao M, Gu C, Fu L, et al. Genome analysis of the mpox (formerly monkeypox) virus and characterization of core/variable regions. Genomics 2024;116:110763. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Li S, Liang C, Xiao Q, Luo J. Drug repositioning based on residual attention network and free multiscale adversarial training. BMC Bioinformatics 2024;25:261. [CrossRef]

- Ashburn TT, Thor KB. Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004;3:673–83. [CrossRef]

- Rozewicki J, Li S, Amada KM, Standley DM, Katoh K. MAFFT-DASH: integrated protein sequence and structural alignment. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:W5–10. [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J Chem Inf Model 2021;61:3891–8. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Yang X, Gan J, Chen S, Xiao Z-X, Cao Y. CB-Dock2: improved protein–ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res 2022;50:W159–64. [CrossRef]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 2004;25:1605–12. [CrossRef]

- Peng Q, Xie Y, Kuai L, Wang H, Qi J, Gao GF, et al. Structure of monkeypox virus DNA polymerase holoenzyme. Science 2023;379:100–5. [CrossRef]

- Prévost J, Sloan A, Deschambault Y, Tailor N, Tierney K, Azaransky K, et al. Treatment efficacy of cidofovir and brincidofovir against clade II Monkeypox virus isolates. Antiviral Res 2024;231:105995. [CrossRef]

- Stafford A, Rimmer S, Gilchrist M, Sun K, Davies EP, Waddington CS, et al. Use of cidofovir in a patient with severe mpox and uncontrolled HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2023;23:e218–26. [CrossRef]

- Morrel EM, Spruance SL, Goldberg DI, Iontophoretic Acyclovir Cold Sore Study Group. Topical Iontophoretic Administration of Acyclovir for the Episodic Treatment of Herpes Labialis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Clinic-Initiated Trial. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:460–7. [CrossRef]

- Ahronowitz I, Fox LP. Herpes zoster in hospitalized adults: Practice gaps, new evidence, and remaining questions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:223-230.e3. [CrossRef]

- Pisitpayat P, Jongkhajornpong P, Lekhanont K, Nonpassopon M. Role of Intravenous Acyclovir in Treatment of Herpes Simplex Virus Stromal Keratitis with Ulceration: A Review of 2 Cases. Am J Case Rep 2021;22:e930467. [CrossRef]

- Postal J, Guivel-Benhassine F, Porrot F, Grassin Q, Crook JM, Vernuccio R, et al. Antiviral activity of tecovirimat against monkeypox virus clades 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b. Lancet Infect Dis 2025;25:e126–7. [CrossRef]

- Arasu MV, Vijayaragavan P, Purushothaman S, Rathi MA, Al-Dhabi NA, Gopalakrishnan VK, et al. Molecular docking of monkeypox (mpox) virus proteinase with FDA approved lead molecules. J Infect Public Health 2023;16:784–91. [CrossRef]

- Akasov RA, Chepikova OE, Pallaeva TN, Gorokhovets NV, Siniavin AE, Gushchin VA, et al. Evaluation of molecular mechanisms of riboflavin anti-COVID-19 action reveals anti-inflammatory efficacy rather than antiviral activity. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Gen Subj 2024;1868:130582. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wei ,Jin-lai, Qin ,Rui-si, Hou ,Jin-ping, Zang ,Guang-chao, Zhang ,Guang-yuan, et al. Folic acid: a potential inhibitor against SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Pharm Biol 2022;60:862–78. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).