1. Introduction

Flavivirus (renamed Orthoflavivirus) is a genus of the family

Flaviviridae which includes well-known five arthropod-borne viruses: Dengue virus (DENV), West Nile virus (WNV), Zika virus (ZIKV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and Yellow fever virus (YFV) [

1,

2]. They are transmitted by mosquitos and can cause severe diseases in humans and pose a great threat to public health [

3,

4]. Flaviviruses contain a single positive-stranded RNA genome of 10-11 kb, which is translated to a single large polypeptide (~3,400 aa) containing three structural proteins: capsid (C), membrane protein (prM), and envelope protein (E); and seven non-structural (NS) proteins: NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5 [

5,

6]. Non-structural protein 5 (NS5) consists of two enzymes, an N-terminal methyltransferase (MTase) and a C-terminal RNA polymerase, which is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [

6,

7,

8,

9] . The RdRp is the key enzyme for viral genome replication, playing a critical role in the viral life cycle. Consequently, RdRp has become a principal drug target for blocking viral replication to inhibit viral infection [

10,

11,

12,

13]. RdRp is the most conserved RNA component in the viral genomes of flaviviruses since it carries the important function of viral RNA replication [

11,

14,

15]. Based on this exceptional property, we have analyzed different RdRps from five major viral species in the

genus of flaviviruses, including DENV, WNV, and ZIKV, and built up a common 3D-structure of RdRps for drug screening. In this report, we have described our first test in this approach and identified three compounds, and one of them showed potent activities against the three major flavivirus species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compounds, viruses, and cells

All screening compounds were purchased from the ChemBridge Corporation (San Diego, CA). Each compound was dissolved at 20 mM concentration in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and was used for stock solutions. The flaviviruses used are: Zika virus strain (MR766), which was described previously [

23] and Dengue Virus Serotype 2 New Guinea C strain (DENV-2, VR-1584) were purchased from the ATCC. West Nile virus (strain CT2741) was provided by Dr. John F. Anderson at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. All viral titers were determined by plaque assay using Vero cells (African green monkey kidney cells of Vero cells ATCC CCL-81 or Vero E6 cells, ATCC CRL-1586).

2.2. Virus Inhibition assay

2.2.1. Determining EC50 by Plaque Assay (ZIKV)

All Vero-E6 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate with a density of 105 cells per well and incubated for two days. Cells were infected with virus at 0.05PFU/cell (MOI 0.05), then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1h shaking the plate every 10 mins. The viral solution was removed after that. For screening, one concentration of compounds at 6 μM were loaded to the wells of the plate. After 48-72 h, the culture media were collected for Plague assay.

For EC50 assay, Vero-E6 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate with a density of 105 cells per well. Cells were infected with viruses at 0.05 PFU/cell (MOI 0.05) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1 h. Serial 2x diluted compound solutions were added to the cells and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 48 h. Cell culture media were collected and assayed for infectious virus by plaque assay.

2.2.2. Determining EC50 by Plaque Assay (WNV)

Vero-E6 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a concentration of 6 × 105 cells per well. The compound (OFB3) was 2-fold serially diluted (10 μM to 0.02 μM) and applied to Vero cells for 4 h. Approximately 100 PFU of WNV were added to each well and incubated for 1h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After incubation, the compound-containing medium was removed, and the cells were covered with an overlay medium containing 1% SeaPlaque Agarose (Lonza). The plates were incubated for 4 days till the plaques were observed. Plaques were stained with Neutral Red and counted. The EC50 value of the compound was determined by using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.0).

2.2.3. RT-qPCR for WNV

Vero-E6 cells were seeded in six-well plates at a concentration of 5 × 10

5 cells per well. After overnight incubation, Vero cells were treated with 5 μM of OFB1, OFB3, OFB15, and the control (0.1% DMSO) for 2 h. Compounds and DMSO-treated cells were then infected by 1 MOI (Multiplicity of Infection) of WNV (strain CT2741) for 24 h. After 24 h, infected cells were collected, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent. cDNA was synthesized using Iscript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad), WNV-envelope (WNV-E) RNA copy numbers were quantified using probe-based qPCR and normalized to cellular β-actin as a housekeeping gene [

23].

2.2.4. Plaque Reduction neutralization test (PRNT) for DENV

Vero-E6 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 6 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight. Triplicate wells of cells were treated with 10µM of each compound OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15, while negative control wells were treated with 0.1% DMSO for 2 h. Following treatment, all cells were infected with 100 plaque-forming units (PFU) of DENV-2 and incubated for 1 hour at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After removing the virus inoculum, the cell monolayers were overlaid with 1% SeaPlaque agarose (Lonza) and incubated for 9 days at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to allow plaque formation. The plaques were stained with Neutral Red for 3 h, counted, and the percentage reduction in plaque formation was calculated relative to the control to evaluate the antiviral activity of the test compounds.

2.2.5. Focus forming assay (FFA) for DENV

Vero-E6 cells were plated at of 6 × 10

5 cells/well in 6-well plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO

2. The cells were treated with 10 µM of OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15 and 0.1% DMSO for negative control for 2 h at 37 °C. Then the medium was replaced with 2 ml/well of 1 x Opti MEM GlutaMAX (Gibco) medium supplemented with 1% Methylcellulose (Sigma), 10% FBS, and 1% P/S, and incubated for 5 days. After the incubation, the overlay medium was removed and washed gently with PBS. The plates were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X for 20 min at RT, and blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h. The cells were then probed with 4G2 antibody diluted with 5% skim milk in a 1:50 ratio, incubated at 4 °C overnight in the dark, followed by two 5-minute washes with 0.1% PBST. The cells were then probed with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Abcam, catalog number ab97023), diluted with 5% skim milk in 1:500 ratio, incubated at 4 °C in the dark for 2 h, followed by two 5-min washes with 0.1% PBST, and air dried for 20 min at RT. The Immuno-positive foci were developed with TrueBlue peroxidase substrate (KPL, Sera care) 70. The foci were counted, and the percentage reduction in foci was calculated and compared to the control to evaluate the antiviral activity of the test compounds. The method is adopted from a previous study [

25].

2.3. Cytotoxicity assay

The Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. The VERO-E6 cells (3000/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24h at 37 °C. Media was removed and replaced with 100 μl of compound solution in triplicates for two days, and then replaced the compound solution with 100 μl complete DMEM for continued culturing for one more day. The cultured media were removed, and the cells were washed once with PBS for analysis. A 50 μl solution of 5 mg/ml MTT [3-4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm and at 650 nm (background) wavelength.

2.4. Bioinformatic analysis and molecular modeling

The sequence comparison, alignment and dendrogram built used BioEdit (BioEdit.exe). Molecular modeling was conducted using Modeller [

26] and Discovery Studio Visualizer (Dassault Systemes BIOVIA). The consensus protein sequence of POLcon was generated from all five RdRp protein sequences, and then POLcon 3D structure was created. A conserved three Aspartic acids (Triple-D) structural motif was identified for targeting. Since non-structural protein 5 (NS5) of the DENV genome consists of two functional domains, the N-terminal methyltransferase (MTase) domain (1-272aa) and C-terminal RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) domain (273-900aa) [

27,

28]. In the POLcon model, only the RdRp protein sequence is used and numbered, so the Triple-D motif residue positions should be D261 (D535), D391(D665), and D392(D666).

2.5. Molecular docking

Molecular docking and analysis were performed using AutoDock Vina [

29,

30] and Open-Source PyMOL [

31]. AutoDock Vina is an open-source tool for effective ligand-receptor docking by estimating the standard chemical potentials between receptors and ligands [

29]. Open-Source PyMOL is a free version of the molecular analysis software PyMOL maintained by Schrödinger, LLC, providing tools for creating molecular graphics and analyzing molecular interactions.

Specifically, the receptor and ligands were first preprocessed using Open-Source PyMOL. Then, AutoDock Vina was employed to estimate the docking results. The receptor used for docking was the POLcon with preprocessing including the addition of hydrogens and the removal of water molecules. The grid box for active site was positioned based on the Triple-D motif locations of POLcon. The ligands used for docking were OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15 with preprocessing including the addition of hydrogens.

2.6. Statistics assay

GraphPad Prism software (version 10.0) was used for all statistical analyses for making the neutralization and cytotoxicity figures and determining average values, standard errors, and values of IC50 or CC50. Statistical significance analysis was performed using a parametric unpaired t-test.

3. Results

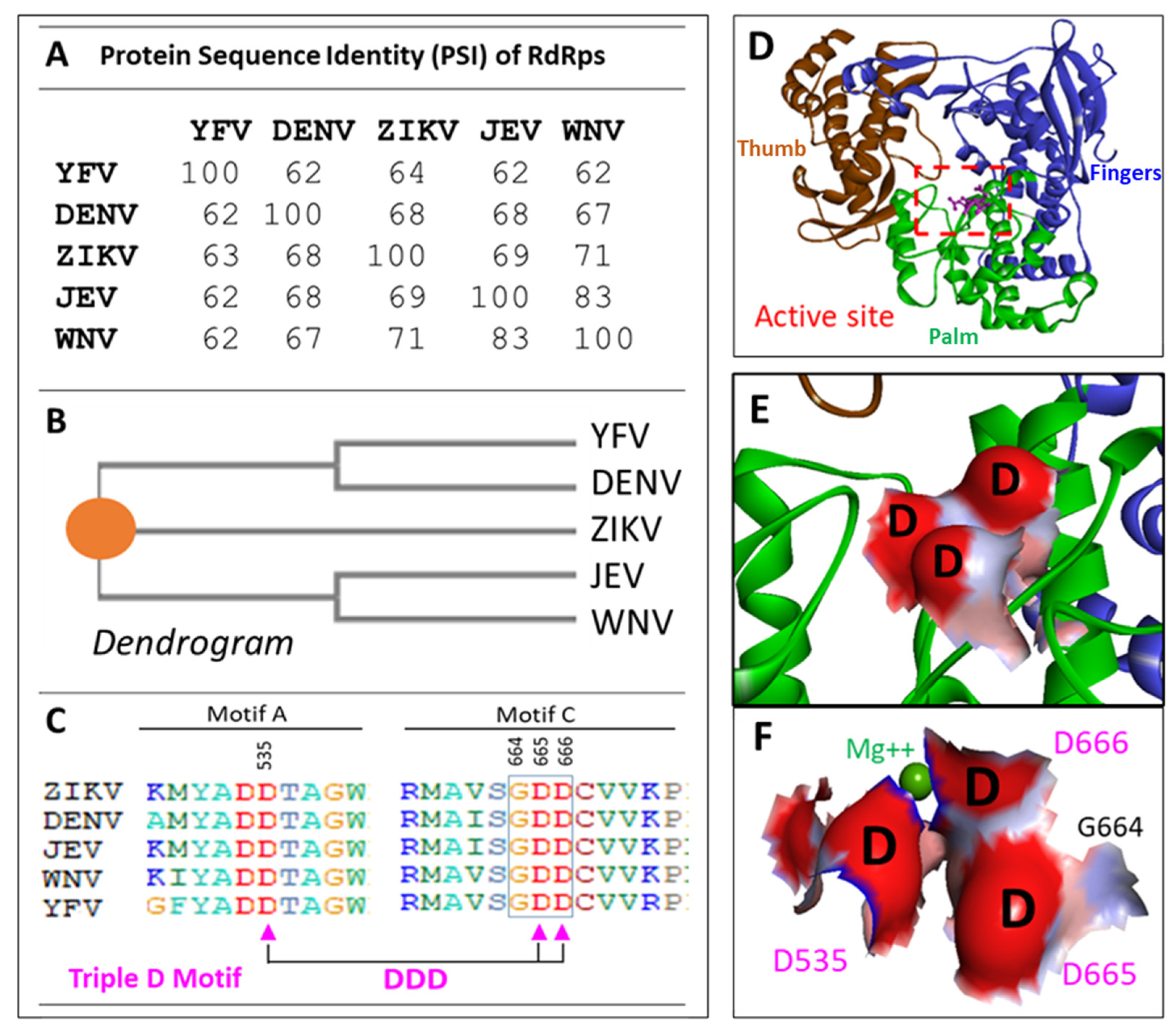

3.1. Building up the consensus RdRp structure (POLcon) for compound screening

By comparing protein sequences of RdRps of the major human pathogenic flaviviruses, we found that their sequence identities are from 62% to 83% (

Figure 1A). From the dendrogram, ZIKV actually is in the middle of two closed groups of DENV-YFV, and JEV-WNV (

Figure 1B). From the sequence and structural analyses of the active-site, we have identified a conserved three Aspartic acids (D535-D665-D666), name Triple-D motif. Unlike the GDD motif (G664-D665-D666) described previously [

8], which is a linear motif and only located the Motif-C; the Triple-D motif is composed of sequences from Motif A and Motif C (

Figure 1C), which is 3-dimensional structural motif and has a negatively charged surface (

Figure 1E,F). We utilized their consensus sequence of the five RdRp sequences to build up a common RdRp structural model called POLcon (

Figure 1D). In this model, we found the Triple-D motif appeared to be more evident in the activate site as it forms a negatively charged inner surface right at the RNA exit (

Figure 1E,F), which provides a perfect drug target. Then, we evaluated this model by conducting virtual compound screening against the Triple-D motif at the active site of POLcon to identify compounds that may have activities for anti-flaviviruses.

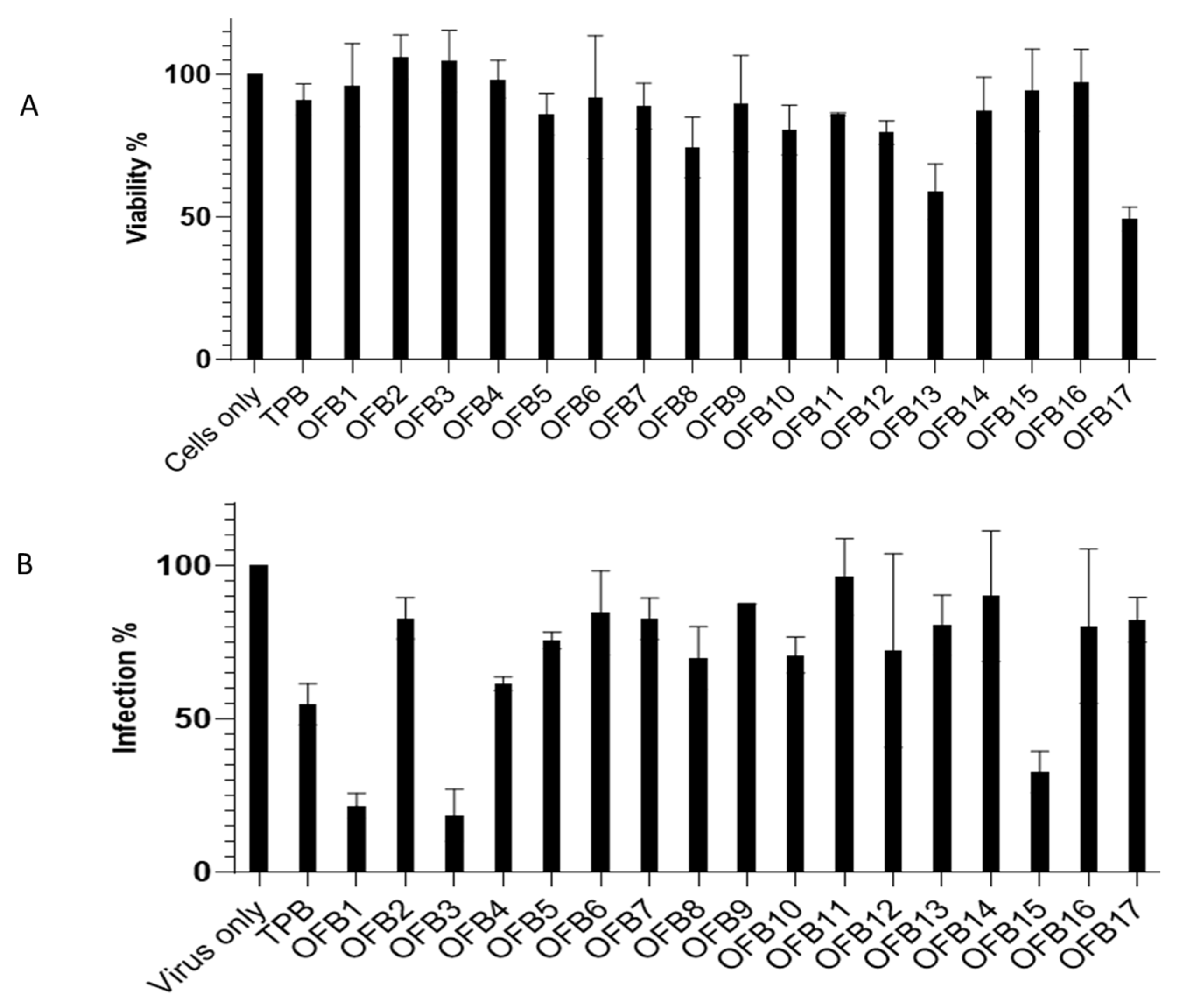

3.2. Screening of compounds against ZIKV infection

Seventeen compounds from virtual screening were purchased and applied for the first experimental screening against ZIKV replication in a cell-based system. Vero-E6 cells were used for compound inhibition test using a plaque forming assay in a 24-well plate. The cytotoxicity of the compounds was also evaluated using an MTT assay at 6 μM concentration. The results are presented in

Figure 2A for cytotoxicity assay (MTT) and

Figure 2B for inhibition against ZIKV with a plaque forming assay. It was observed that compounds OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15 showed strong inhibitions against ZIKV infection at a concentration of 6 μM without showing any cytotoxicity. They are better than compound TPB, which was previously identified as a ZIKV inhibitor that was used as the position control in our experiments.

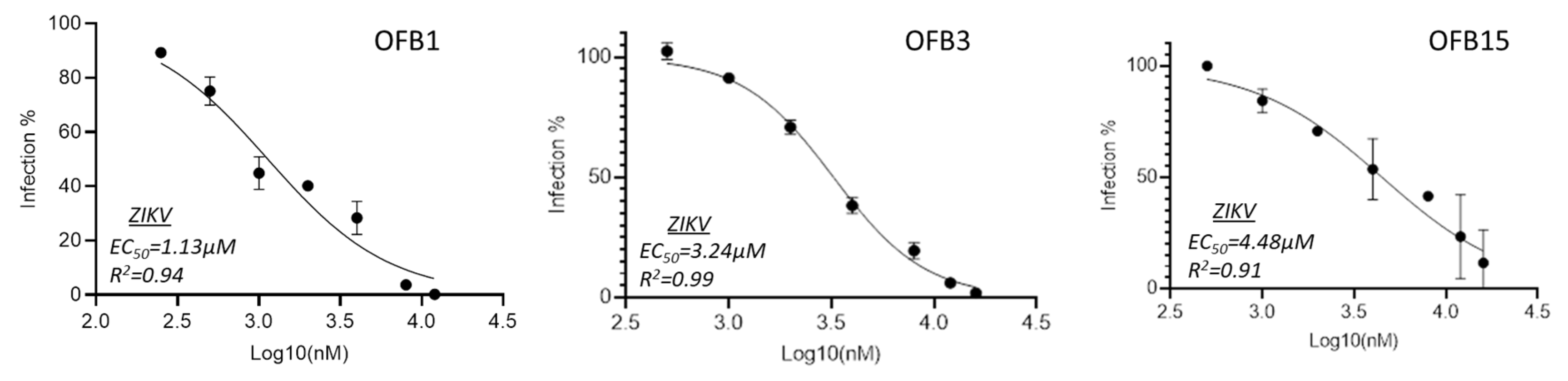

3.3. Inhibition IC50 analysis against ZIKV

To evaluate the inhibition potency of these three compounds , we conducted inhibition analysis using a serial concentration of compounds ranging from 0.5 μM to 16 μM to determine their EC

50 values. The data indicated that all three compounds, OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15 showed the EC

50 values are in the lower micromolar range, which are 1.13 μM, 3.24 μM, and 4.48 μM, respectively (

Figure 3).

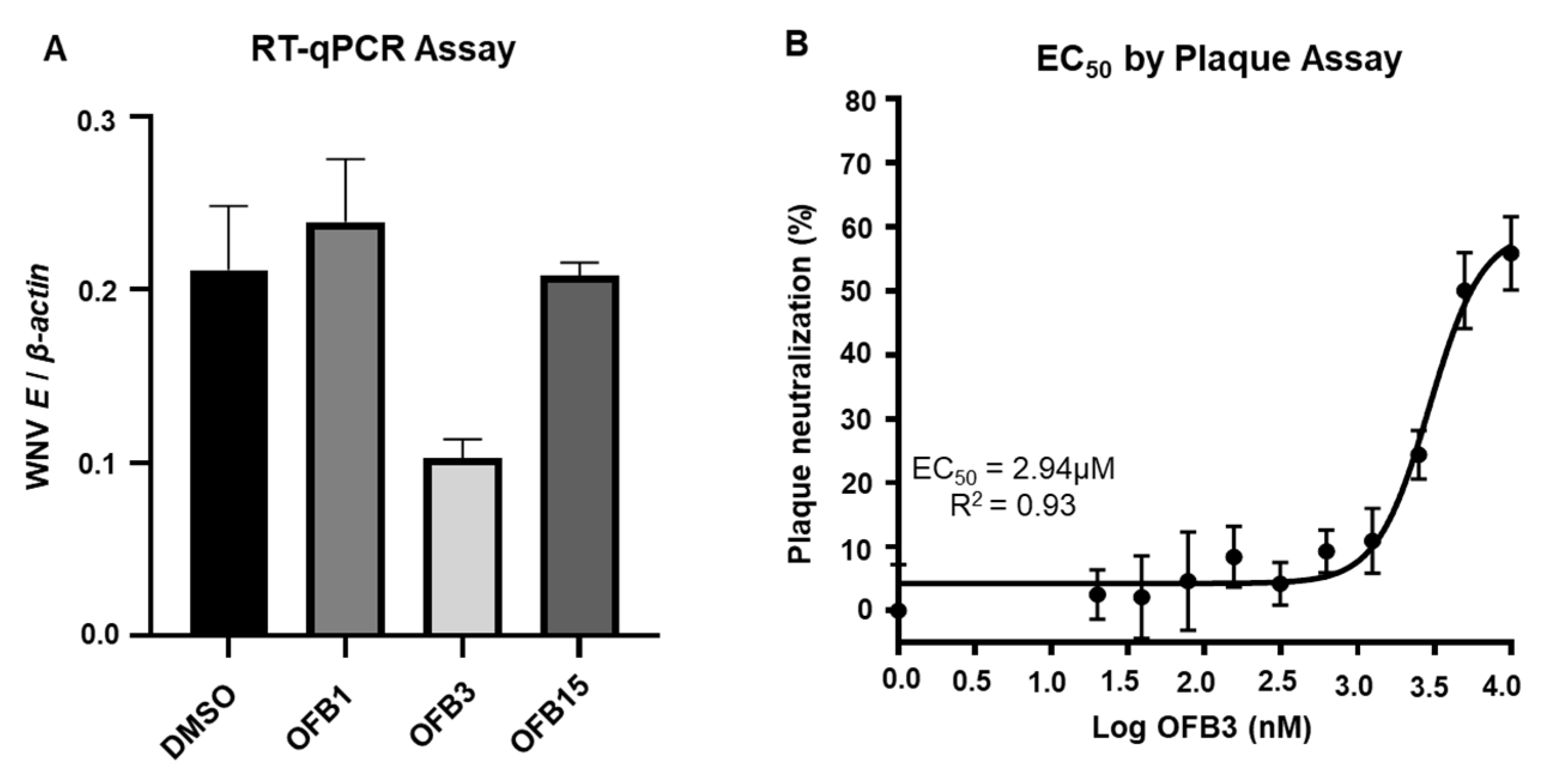

3.4. Inhibition analysis against WNV

To determine whether these three compounds have activity against WNV infection, we conducted an inhibition analysis. Interestingly, the screening assay at 5 μM using RT-qPCR and the results indicated that only OFB3 showed significant inhibition, but not OFB1 or OFB15 (

Figure 4A). In addition, the EC

50 analysis for compound OFB3 with plaque assay showed that the EC

50 value is 2.94 μM (

Figure 4B). It is confirmed that compound OFB3 has comparable inhibiting activity to WNV as to ZIKIV.

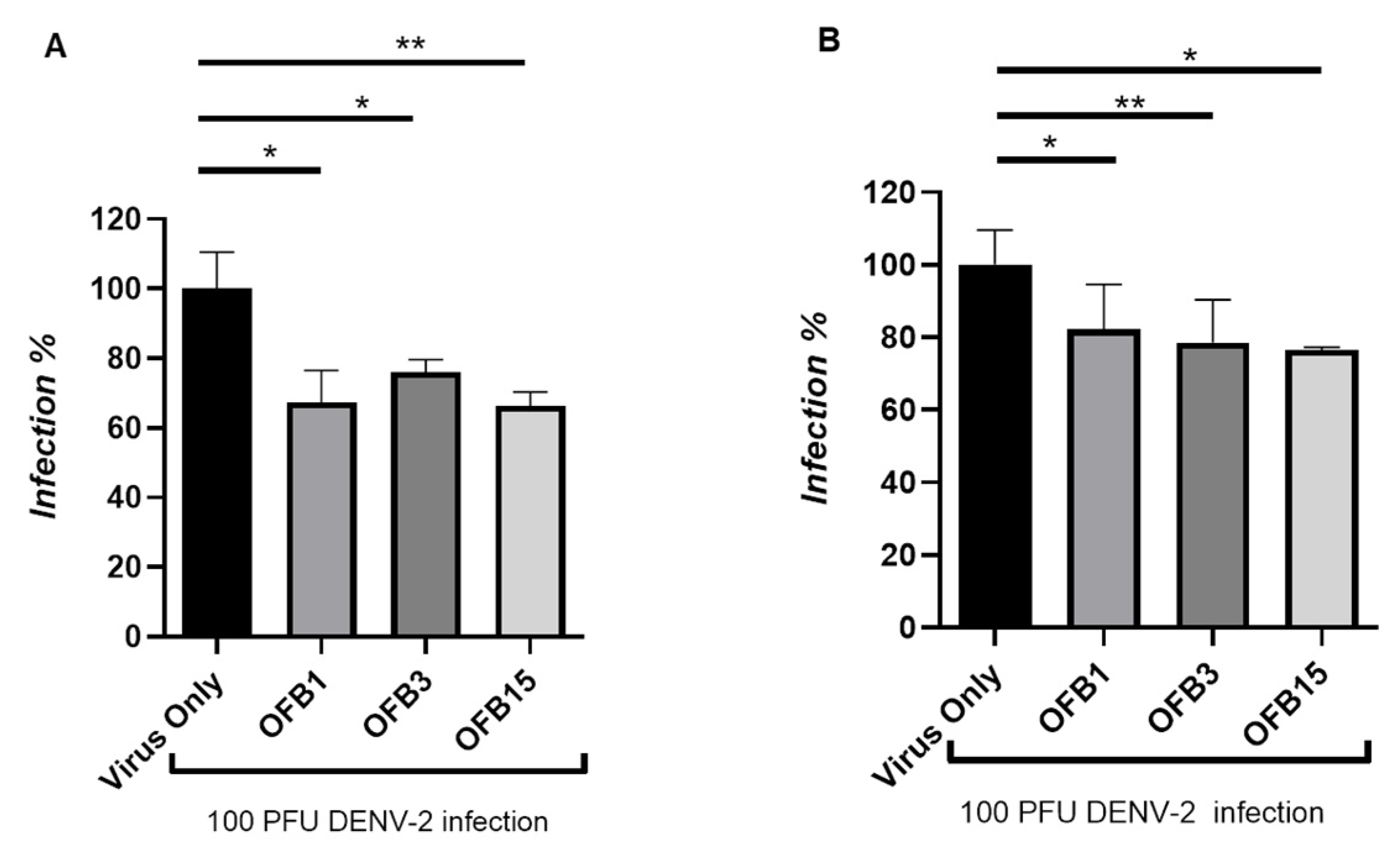

3.5. Inhibition analysis against DENV

DENV has four serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4), and all of these four serotype viruses are capable of inducing severe disease. In this report, we tested serotype 2 (DENV-2). From the plaque reduction assay, the data has indicated that all three compounds OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15 did considerably inhibit DENV-2, but not as potent as for ZIKV at 6 μM concentration of compounds, and the OFB3 was not as potent as for WNV, but OFB1 and OFB15 also have certain activities for WNV (

Figure 5A). To confirm these data, we then used another method called Focusing forming assay (FFA) which is an immunostaining-based method by detecting DENV glycoprotein with anti-flavivirus antibody 4G2. The data actually are very similar to the plaque assay data, which demonstrated that all these three compounds (OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15) inhibit replication of DENV-2 virus but with less potency than against ZIKV and WNV (

Figure 5B).

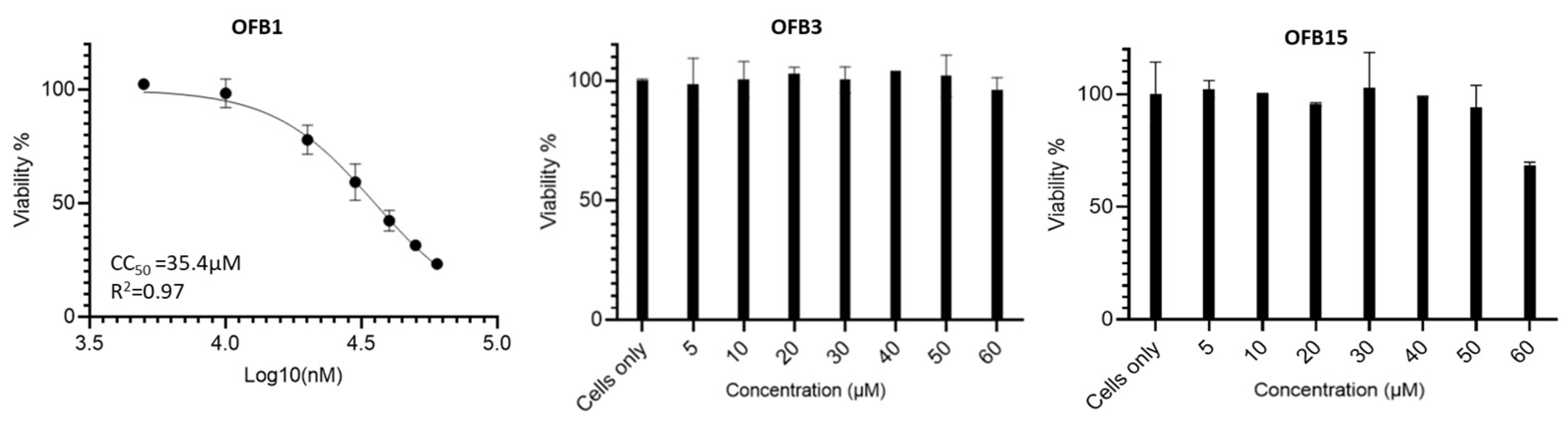

3.6. CC50 assay of the compounds OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15

To determine the selectivity indexes of these compounds, we conducted the cytotoxicity analysis to obtain CC

50 values, which indicate the concentration that reduces the number of viable cells by 50% compared with the control. The CC

50 value for OFB1 is 35.4 μM, but OFB15 started showing cytotoxicity when the concentration reached 60 μM. In contrast, OFB3 did not show any cytotoxicity when 60 μM was used, indicating that OFB3 is the safest molecule among these three compounds (

Figure 6).

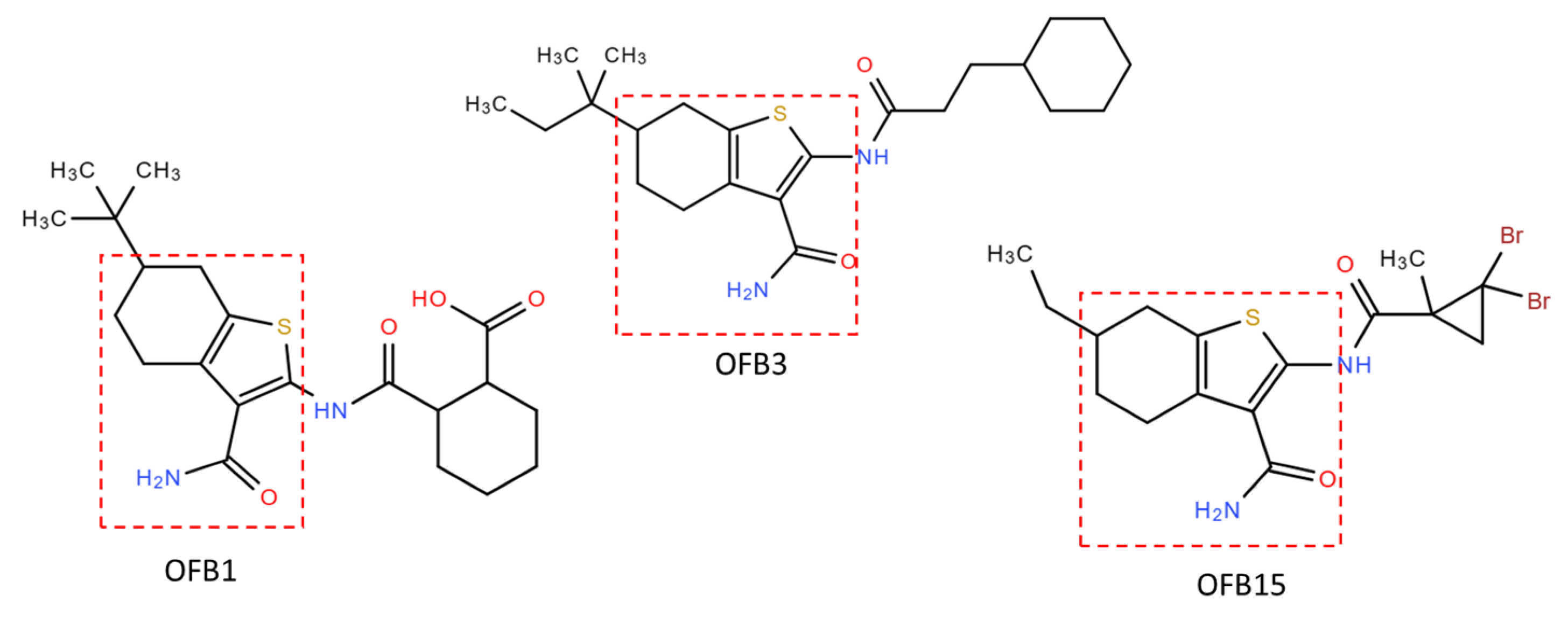

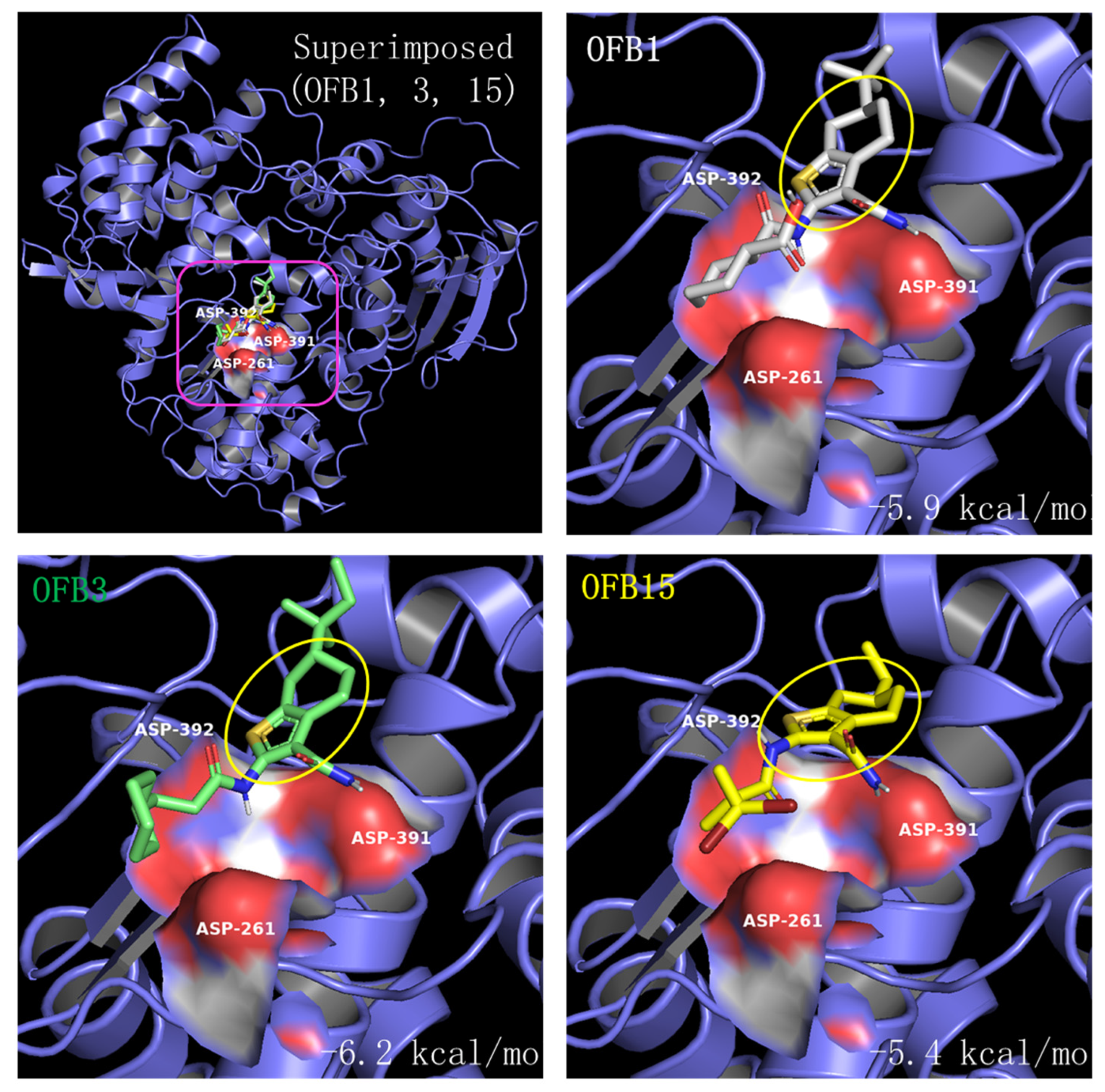

3.7. Molecular docking of OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15

Comparing the structures of these three inhibitors, they all have a common structure of Benzothiophene (

Figure 7). The molecular docking of OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15 was conducted using AutoDock Vina program, and the results are shown in

Figure 8. According to Molecular docking, all these three compounds could dock to Triple-D motif in the activate site of RdRp. The Benzothiophene appears to be playing a major role in contact with the Triple-D motif. The differences at the position-6 group of Benzothiophene may have contributed to the activity differences among these compounds against different viruses. It is suggested that Benzothiophene derivates could bind to the Triple-D motif at the activate site of RdRp to block viral replication. To our knowledge, there are no reports of Benzothiophene derivatives for anti-flavivirus infection.

4. Discussion

Based on the virtual screening against the target of the Triple-D motif, the Benzothiophene-derived compounds OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15 are expected to target the Triple-D motif in the active site of RdRp to interfere with viral genome replication. Further molecular docking analysis demonstrated that these compounds have a high affinity for binding to the Triple-D motif and preventing viral RNA synthesis and replication. This finding will provide a new class of compounds for drug design and development against flavivirus infections.

According to the structures of these three compounds, we observed a common element of Benzothiophene. These S-bicyclic rings may play a vital role in interacting with the binding site in the RdRps. From Molecular docking, it has been revealed that OFB compounds could interact with the negative charge surface of the Triple-D motif through electrostatic force, such as forming hydrogen bonds. These electrostatic attractive interactions will be helpful for conducting the Benzothiophene-based design to get potent compounds against flaviviruses. For example, the extended methyl group or cyclohexane ring or both of compound OFB3 may have contributed to the role of inhibiting WNV. More extensive screening against this Trible-D motif of POLcon will be conducted to find more potent common lead compounds for drug development against flaviviruses.

Benzothiophene is a natural aromatic organic compound with a molecular formula C

8H

6S and has a bioactive structure property used as a scaffold for chemical synthesis. Benzothiophene derivatives have been widely used as pharmaceutical drugs [

1][

18], but there are few reports for antivirals [

19,

20]. Interestingly, a similar class of pyridobenzothiazole derivatives was reported to have activities against HCV, DENV, and WNV, which are also by targeting the RdRp at the active site [

21,

22].

The OFB compounds exhibited activities against different flaviviruses. All these three OFB compounds (OFB1, OFB3, and OFB15) showed strong inhibition for ZIKV, but weaker for DENV (DENV-2), and only OFB3 can neutralize WNV. Although we have not tested JEV and YFV, this report has provided a proof-of-concept that developing common or shared drugs is possible. The conserved common structure of POLcon has offered a substantial base for drug targeting, and especially the negatively charged Triple-D motif, which may have the advantages for those positively charged binders.

In conclusion, using a common RdRp structure of POLcon, we have identified a novel class of Benzothiophene derivates as inhibitors for flaviviruses. It has been demonstrated that POLcon is a promising target for finding shared drugs against different flaviviruses. Certainly, we will continue working on this target to identify more potent leading compounds for anti-flavivirus drug development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SHX.; methodology, SHX, LLW, SK, FB, YL.; investigation, LLW, SK, AH, RB, MP, SA, YL, FB and SHX.; resources, LZ.; writing—original draft preparation, SHX and LLW.; writing—review and editing, SHX, LLW, FB, SK, YL, LZ.; supervision, SHX.; funding acquisition, SHX and FB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Institutes of Health 1R15AI178654(FB) and the American Heart Association 23AIREA1051360(FB)..

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nicholas Palermo (Holland Computing Center) for helping with the initial compound screening, Dr. Duan S. Loy, Marijana Bradaric, and Dr. John Dustin Loy (Diagnostic Center) and students Arlie Nghiem and Rebecca Pecora for helping with the qPCR detection method. This research was supported by the internal funding of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and by the University’s Undergraduate Creative Activities and Research Experience program (UACRE). FB was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health 1R15AI178654 and the American Heart Association 23AIREA1051360.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Postler, T.S.; Beer, M.; Blitvich, B.J.; Bukh, J.; de Lamballerie, X.; Drexler, J.F.; Imrie, A.; Kapoor, A.; Karganova, G.G.; Lemey, P.; Lohmann, V.; Simmonds, P.; Smith, D.B.; Stapleton, J.T.; Kuhn, J.H. Renaming of the genus Flavivirus to Orthoflavivirus and extension of binomial species names within the family Flaviviridae. Arch Virol 2023, 168, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, S.M. Flaviviruses. Curr Biol 2016, 26, R1258–R1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, A.K.; Fikrig, E. Zika Virus and Sexual Transmission: A New Route of Transmission for Mosquito-borne Flaviviruses. Yale J Biol Med 2017, 90, 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Diani, E.; Lagni, A.; Lotti, V.; Tonon, E.; Cecchetto, R.; Gibellini, D. Vector-Transmitted Flaviviruses: An Antiviral Molecules Overview. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Structural Biology of the Zika Virus. Trends Biochem Sci 2017, 42, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, N.J.; Campos, R.K.; Liao, K.C.; Prasanth, K.R.; Soto-Acosta, R.; Yeh, S.C.; Schott-Lerner, G.; Pompon, J.; Sessions, O.M.; Bradrick, S.S.; Garcia-Blanco, M.A. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Flaviviruses. Chem Rev 2018, 118, 4448–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, A.S.; Lima, G.M.; Oliveira, K.I.; Torres, N.U.; Maluf, F.V.; Guido, R.V.; Oliva, G. Crystal structure of Zika virus NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.H.; Rossmann, M.G. RNA-dependent RNA polymerases from Flaviviridae. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2009, 19, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.; Sevvana, M.; Kuhn, R.J.; Rossmann, M.G. Structural biology of Zika virus and other flaviviruses. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2018, 25, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazhanskaya, E.; Morais, M.C.; Choi, K.H. Flavivirus enzymes and their inhibitors. Enzymes 2021, 49, 265–303. [Google Scholar]

- Malet, H.; Masse, N.; Selisko, B.; Romette, J.L.; Alvarez, K.; Guillemot, J.C.; Tolou, H.; Yap, T.L.; Vasudevan, S.; Lescar, J.; Canard, B. The flavivirus polymerase as a target for drug discovery. Antiviral Res 2008, 80, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddipati, V.C.; Mittal, L.; Mantipally, M.; Asthana, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Gundla, R. A Review on the Progress and Prospects of Dengue Drug Discovery Targeting NS5 RNA- Dependent RNA Polymerase. Curr Pharm Des 2020, 26, 4386–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H.; Saito, A.; Mikuni, J.; Nakayama, E.E.; Koyama, H.; Honma, T.; Shirouzu, M.; Sekine, S.I.; Shioda, T. Discovery of a small molecule inhibitor targeting dengue virus NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13, e0007894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, L.L.; Padilla, L.; Castano, J.C. Inhibitors compounds of the flavivirus replication process. Virol J 2017, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubankova, A.; Boura, E. Structure of the yellow fever NS5 protein reveals conserved drug targets shared among flaviviruses. Antiviral Res 2019, 169, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penthala, N.R.; Sonar, V.N.; Horn, J.; Leggas, M.; Yadlapalli, J.S.; Crooks, P.A. Synthesis and evaluation of a series of benzothiophene acrylonitrile analogs as anticancer agents. Medchemcomm 2013, 4, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Kapoor, N.; Surolia, N.; Surolia, A. Benzothiophene carboxamide derivatives as novel antimalarials. IUBMB Life 2011, 63, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vreese, R.; Van Steen, N.; Verhaeghe, T.; Desmet, T.; Bougarne, N.; De Bosscher, K.; Benoy, V.; Haeck, W.; Van Den Bosch, L.; D'Hooghe, M. Synthesis of benzothiophene-based hydroxamic acids as potent and selective HDAC6 inhibitors. Chem Commun (Camb) 2015, 51, 9868–9871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, S.L.; Bronstein, J.C.; Nordby, E.C.; Weber, P.C. Identification and characterization of a benzothiophene inhibitor of herpes simplex virus type 1 replication which acts at the immediate early stage of infection. Antiviral Res 2001, 51, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, M.; Azuma, M.; Wakamatsu, S.I.; Suruga, Y.; Izumo, S.; Yokoyama, M.M.; Baba, M. Marked suppression of T cells by a benzothiophene derivative in patients with human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1999, 6, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, D.; Cannalire, R.; Mastrangelo, E.; Croci, R.; Querat, G.; Barreca, M.L.; Bolognesi, M.; Manfroni, G.; Cecchetti, V.; Milani, M. Targeting flavivirus RNA dependent RNA polymerase through a pyridobenzothiazole inhibitor. Antiviral Res 2016, 134, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfroni, G.; Meschini, F.; Barreca, M.L.; Leyssen, P.; Samuele, A.; Iraci, N.; Sabatini, S.; Massari, S.; Maga, G.; Neyts, J.; Cecchetti, V. Pyridobenzothiazole derivatives as new chemotype targeting the HCV NS5B polymerase. Bioorg Med Chem 2012, 20, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattnaik, A.; Palermo, N.; Sahoo, B.R.; Yuan, Z.; Hu, D.; Annamalai, A.S.; Vu, H.L.X.; Correas, I.; Prathipati, P.K.; Destache, C.J.; Li, Q.; Osorio, F.A.; Pattnaik, A.K.; Xiang, S.H. Discovery of a non-nucleoside RNA polymerase inhibitor for blocking Zika virus replication through in silico screening. Antiviral Res 2018, 151, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, F.; Wang, T.; Pal, U.; Bao, F.; Gould, L.H.; Fikrig, E. Use of RNA interference to prevent lethal murine west nile virus infection. J Infect Dis 2005, 191, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazneen, F.; Thompson, E.A.; Blackwell, C.; Bai, J.S.; Huang, F.; Bai, F. An effective live-attenuated Zika vaccine candidate with a modified 5' untranslated region. NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.; Sali, A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Protein Sci 2016, 86, 2 9 1-2 9 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, T.; Aoki, M.; Ehara, H.; Sekine, S.I. Structures of dengue virus RNA replicase complexes. Mol Cell 2023, 83, 2781–2791 e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, M.; Yao, W.; Lu, J.; Chen, J.; Morrison, J.; Hai, R.; Song, J. A conformational selection mechanism of flavivirus NS5 for species-specific STAT2 inhibition. Commun Biol 2024, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J Chem Inf Model 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger LLC. 2015. The PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.8.

- Duan, W.; Song, H.; Wang, H.; Chai, Y.; Su, C.; Qi, J.; Shi, Y.; Gao, G.F. The crystal structure of Zika virus NS5 reveals conserved drug targets. EMBO J 2017, 36, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.P.; Noble, C.G.; Seh, C.C.; Soh, T.S.; El Sahili, A.; Chan, G.K.; Lescar, J.; Arora, R.; Benson, T.; Nilar, S.; Manjunatha, U.; Wan, K.F.; Dong, H.; Xie, X.; Shi, P.Y.; Yokokawa, F. Potent Allosteric Dengue Virus NS5 Polymerase Inhibitors: Mechanism of Action and Resistance Profiling. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surana, P.; Satchidanandam, V.; Nair, D.T. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of Japanese encephalitis virus binds the initiator nucleotide GTP to form a mechanistically important pre-initiation state. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 2758–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malet, H.; Egloff, M.P.; Selisko, B.; Butcher, R.E.; Wright, P.J.; Roberts, M.; Gruez, A.; Sulzenbacher, G.; Vonrhein, C.; Bricogne, G.; Mackenzie, J.M.; Khromykh, A.A.; Davidson, A.D.; Canard, B. Crystal structure of the RNA polymerase domain of the West Nile virus non-structural protein 5. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 10678–10689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).