Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- For surveying and mapping. Autonomous vehicles equipped with LiDAR and SLAM systems navigate the mine to generate 3D maps for planning and operational purposes [8];

- Transportation. Autonomous haul trucks navigate predefined routes to transport ore, minerals, or waste material between loading and dumping points in underground mines [9];

- Drilling and Blasting Operations. Navigation systems guide autonomous drilling machines to precise coordinates within the mine for efficient drilling [10];

- Inspection and Maintenance. Autonomous robots navigate mine tunnels to detect structural integrity issues and gas leaks [11];

- Search and Rescue Operations (SAR). Navigation enables unmanned vehicles to explore hazardous or collapsed mine areas where human entry is unsafe [12].

- Underground navigation in autonomous vehicle applications involves several key steps to ensure safe and efficient operation. It begins with Localization, where the vehicle determines its position and orientation within its environment using techniques like SLAM, or Dead-reckoning. Next is Perception, which involves sensing and mapping the surroundings using Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), cameras, or radar to detect obstacles and terrain features. Then Path planning determines the optimal route to reach a destination while avoiding obstacles and adapting to environmental changes. Finally, Motion control executes the planned path by steering, accelerating or braking, ensuring precise and smooth movement. These steps are supported by sensor integration and real-time decision-making to handle dynamic conditions effectively [13].

- In the context of autonomous underground navigation, a variety of platforms assume significant roles in enhancing efficiency, safety and productivity. Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are among the key technologies driving automation in underground mining operations. Both of them are essential for surveying, exploration, inspection and SAR tasks, where human intervention is either constrained or infeasible. UGVs with high power and payload capacity have advantages in long-duration missions and transportation, but they are limited in mobility. UAVs, on the other hand, are good at quick inspections and can reach areas that are difficult to access [14]. Beyond unmanned vehicles, many mining machines, including LHDs, are being redesigned for full automation, further enhancing the efficiency and safety of underground operations [15].

- As one of the crucial components of navigation, path planning might be modified or enhanced with optimization strategies to achieve efficient and accurate navigation in the underground mining environment. While extensive research has been conducted on surface-level path planning [16], underground navigation remains a critical and evolving research area due to its unique environmental challenges and constraints. This paper provides a comprehensive review of recent advancements in underground UGV path planning, highlighting emerging trends, methodological improvements, and existing gaps in the field. The analysis aims to offer insights into current limitations and identify opportunities for future research and development in optimizing autonomous navigation for underground mining applications.

2. Requirement Analysis for Path Planning for UGV in Underground Mining Environment

- UGV must operate autonomously in GPS-denied environments;

- Performing effectiveness in low-light, high-dust and uneven terrain conditions with help of advanced sensors such as LiDAR, cameras, radars, IMUs and motor encoders for accurate environmental mapping and obstacle detection;

- UGV must be compatible with Robot Operating System (ROS) framework, enabling modular communication, multi-sensor integration and scalability;

- UGV must be reliably detect and avoid both static and dynamic obstacles, generating accurate and efficient paths in real-time while incorporating recovery behaviors to handle unexpected environmental changes;

- Adaptability to environmental complexity, such as dynamic obstacles and sudden changes in tunnel structures, is necessary for reliable underground navigation

- Energy-efficient operation is also essential to prolong the operational lifespan of UGVs in underground mine [17].

3. Materials

3.1. Sensors to Perceive Environment

- LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging);

- Depth Camera;

- Radar;

- IMU (Inertial Measurement Units);

- Motor encoders.

3.2. ROS as Main Operation System

- ROS is open source that can be augmented by developers;

- Modular and flexible framework allows researchers to customize and adapt it for a wide range of applications.

- Cross-platform compatibility and hardware-agnostic design supports diverse robotic systems from drones and robotic arms to autonomous vehicles.

- Robust built-in libraries for computer vision, motion planning and navigation;

- Simulation tools such as Gazebo and RViz, allowing researchers to efficiently prototype, test and refine robots.

- Integration with AI and machine learning technologies extends its usefulness in creating intelligent and autonomous systems [28].

- Packages - is the fundamental unit of software organization in ROS. It contains all the necessary files for a specific functionality, such as nodes, libraries, configurations and launch files. Each package is self-contained, enabling easy reuse and sharing;

- Metapackages - are collections of related packages grouped together under a common purpose, such as ros_base or desktop_full;

- Workspaces - are directories where ROS packages are developed and built.

- Each package has a standardized directory structure:

- src/: Source code for nodes and other scripts;

- launch/: Launch files to start nodes and set parameters;

- config/: Configuration files of the robot descriptions to manage its behavior;

- msg/ and srv/: Definitions for custom message and service types;

- CMakeLists.txt and package.xml: Build system and package metadata files.

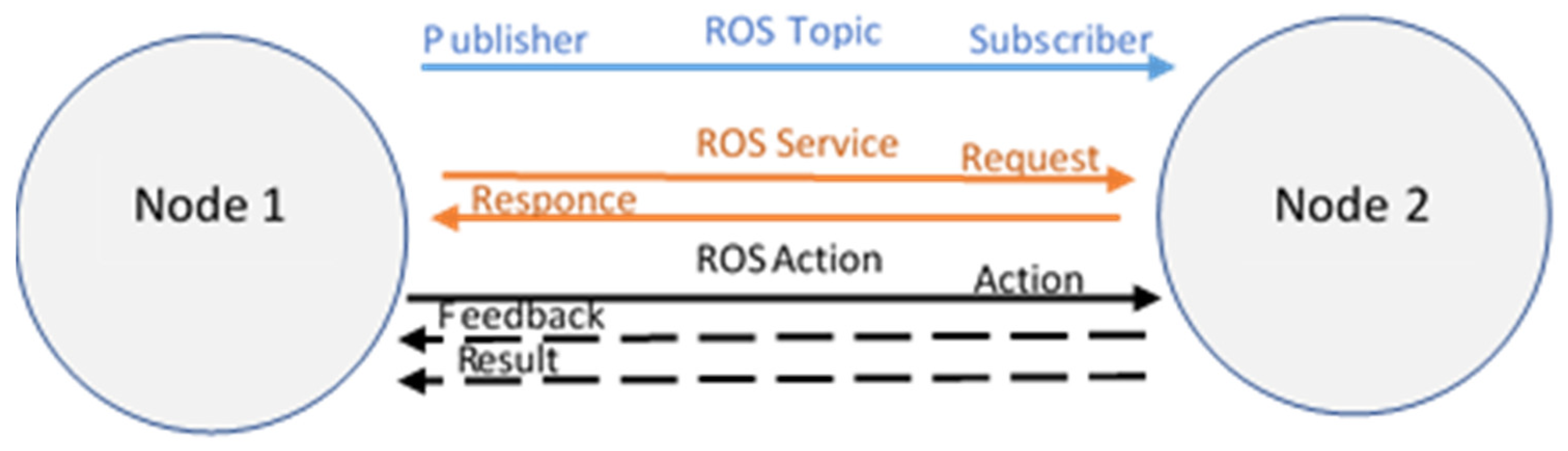

- ROS defines specific file types for communication as Figure 1:

- Messages: Define data structures for node-to-node communication;

- Services: Specify request-response structures for synchronous interactions;

- Actions: Provide a framework for long-running tasks with feedback.

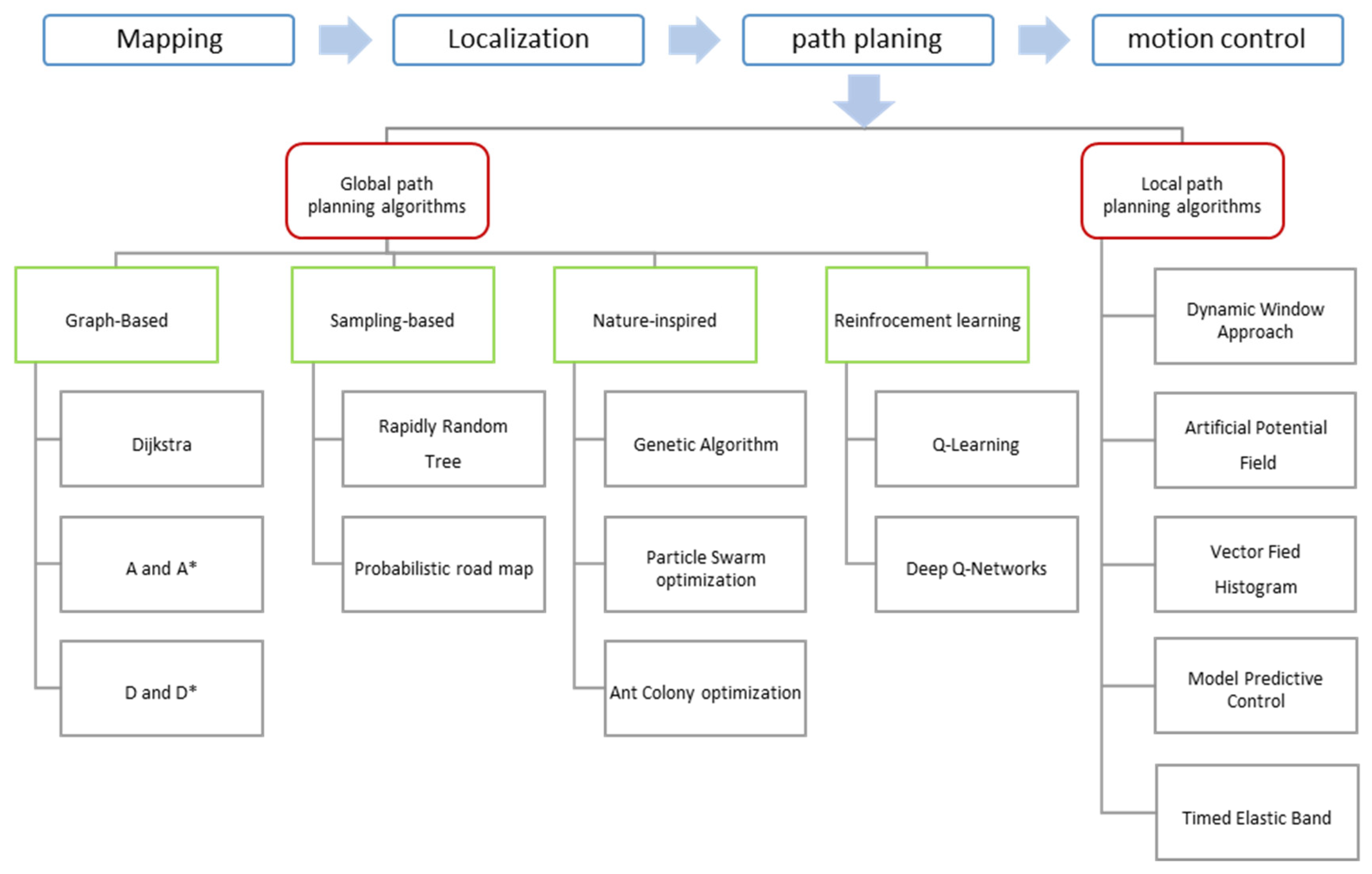

4. Path Planning Framework

4.1. Global Path Planning Algorithms

-

Graph-Based algorithms. These algorithms model the environment as a graph and find the shortest path using various search techniques. Sample algorithms:

- Dijkstra: Dijkstra’s algorithm is designed to determine the minimum-cost path from a source vertex to all other vertices in a directed graph. The algorithm operates by iteratively selecting the closest unvisited node, updating the shortest known distances to its neighboring vertices and continuing this process until the destination node is reached or all reachable nodes have been explored. Since Dijkstra’s algorithm follows a breadth-first search-like approach, it systematically expands the search from the starting node outward. However, this leads to relatively high time and space complexity, especially in large graphs, as it requires maintaining and updating distance information for multiple vertices throughout the execution [36];

- A and A* algorithms: A algorithm, often linked to Dijkstra’s approach, identifies the shortest path between nodes in a weighted graph by evaluating all possible routes based on cumulative cost. However, it lacks heuristic guidance, which can make it inefficient in larger environments. The A* algorithm improves upon this by integrating a heuristic function with cost-based search, allowing it to prioritize more promising paths. It evaluates the total estimated cost from the start node and estimates the remaining cost to the goal [37];

- D* and D* lite: The D* algorithm is an incremental path-planning method designed for dynamic environments, where obstacles or terrain conditions may change over time. It initially computes an optimal path from the start position to the goal under the assumption of a static environment. When the robot moves and encounters updated information, D* efficiently recalculates only the affected portions of the path instead of recomputing from scratch, making it suitable for real-time applications in navigation and robotics. D* Lite, a simplified version of D*, follows a similar approach but computes paths in reverse, from the goal to the start. This backward search allows for efficient path updates when obstacles appear or disappear. By maintaining a cost-efficient priority queue and selectively updating affected nodes, D* Lite reduces computational complexity while preserving optimality [38].

-

Sampling-Based Algorithms. These algorithms generate a path by randomly sampling points in the environment. Sample algorithms:

- Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT). It is designed to efficiently navigate complex, high-dimensional spaces. It incrementally builds a tree by randomly sampling points within the search space and connecting them to the nearest existing node, effectively exploring feasible paths in environments with numerous obstacles. While RRT is proficient at quickly finding a viable path, it doesn’t guarantee optimality [39]. To address this limitation, RRT* was developed as an extension of the original algorithm. RRT* enhances the path quality by incorporating a process of iterative refinement, where it rewires the tree structure to explore shorter or more efficient paths as new samples are added. This approach guarantees that, under sufficient conditions and with an adequate number of samples, RRT* will reach an optimal solution. It achieves this by balancing the rapid exploration capabilities of RRT with optimality [40];

- Probabilistic Roadmap (PRM). This method efficiently navigates high-dimensional spaces. It works in two phases: first, the construction phase generates random collision-free nodes and connects them to form a roadmap, and second, the query phase links the start and goal positions to the roadmap, using graph search algorithms like Dijkstra to determine the optimal path. PRM is particularly effective in static environments where multiple queries are needed, as the roadmap can be reused, reducing computational complexity [41].

-

Nature-Inspired Algorithms. These algorithms are modelled after biological processes and use mathematical optimization techniques to find the best path. Sample algorithms:

- Genetic Algorithm (GA) is an evolutionary optimization technique inspired by the principles of natural selection. It begins with a randomly generated population of candidate solutions, which evolve over multiple iterations through selection, crossover and mutation. A fitness function evaluates each candidate, favoring the best solutions for reproduction. The algorithm applies crossover to combine parent solutions and mutation to introduce small variations, ensuring diversity in the search space. This iterative process continues until an optimal or near-optimal solution is found. GA is widely used in complex optimization problems where traditional methods struggle with large or nonlinear search spaces [42];

- Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm is a population-based optimization technique inspired by the collective movement of birds and fish. It initializes a group of candidate solutions, called particles, which explore the search space by updating their positions based on both their individual best-known solution and the globally best-known solution within the swarm. This dynamic adjustment allows particles to converge toward optimal solutions over multiple iterations. PSO is particularly useful for solving high-dimensional and nonlinear optimization problems due to its simplicity and efficiency in navigating complex search spaces [43];

- Ant Colony Optimization (ACO). It mimics the foraging behavior of ants to find optimal paths in a graph. Artificial ants explore potential routes, depositing virtual pheromones that influence the decisions of subsequent ants. Over successive iterations, paths with stronger pheromone trails become more favorable, leading the swarm toward efficient solutions [44].

-

Reinforcement learning (RL)-based algorithms. RL-based methods learn optimal paths through trial-and-error interactions with the environment, refining their policies over time based on cumulative rewards and don’t require a predefined model [45]. Sample algorithms:

- Q-Learning algorithm. It builds a Q-table where each state-action pair is assigned a value, updated iteratively using the Bellman equation. By maximizing cumulative rewards, the algorithm ensures efficient obstacle avoidance and goal-reaching, making it particularly useful in dynamic or uncertain environments [46];

- Deep Q-Networks (DQN) employs a Deep Neural Network (DNN) to approximate Q-values for state-action pairs, enabling the robot to learn an optimal policy through continuous interaction with the environment. This approach is particularly beneficial in dynamic, uncertain, or partially observable settings where traditional methods struggle. Additionally, experience replay and target networks stabilize training, mitigating the overestimation of Q-values and improving convergence [47].

- Hybrid Algorithms. These algorithms combine two or more approaches to improve efficiency and robustness. Sample combinations: A-RRT*, D-lite with RRT* [48].

4.2. Local Path Planning Algorithms

- Dynamic Window Approach (DWA) is a real-time motion planning algorithm that ensures both collision avoidance and adherence to dynamic constraints. It evaluates a range of possible velocities within a short time horizon and selects the trajectory that optimally balances safety, efficiency and goal direction. By considering the kinematic limitations of the robot and environmental obstacles, DWA enables smooth and reactive navigation in dynamic environments [50];

- Artificial Potential Field (APF). In this approach, the robot is influenced by an artificial force field composed of attractive forces pulling it toward the goal and repulsive forces pushing it away from obstacles. The robot navigates by following the resultant force vector, aiming for a collision-free path to the target. While APF is computationally efficient and straightforward to implement, it can encounter issues such as local minima, where the robot becomes trapped in a position that is not the goal. Various modifications have been proposed to address these limitations and enhance the effectiveness of this method [51];

- Vector Field Histogram (VFH) constructs a two-dimensional Cartesian histogram grid using range sensor data. This grid is continuously updated to reflect the environment of the robot. The algorithm reduces this grid to a one-dimensional polar histogram centered on the current position of the robot, where each sector represents the obstacle density in a specific direction. By analyzing these sectors, VFH identifies obstacle-free paths and determines the most suitable steering direction, allowing the robot to navigate toward its target while avoiding collisions. This method effectively balances reactive obstacle avoidance with goal-oriented navigation [52];

- Model Predictive Control (MPC) is an advanced control strategy that utilizes a dynamic model of a system to predict and optimize its future behavior over a specified time horizon. In the context of mobile robot local path planning, MPC involves formulating an optimization problem that accounts for the kinematic constraints of the robot, environmental obstacles and a predefined cost function. At each time step, the controller solves this optimization problem to determine the optimal control inputs, resulting in a trajectory that guides the robot toward its target while avoiding collisions. This process is repeated in a receding horizon manner, allowing the robot to adapt its path in real-time to dynamic changes in the environment. MPC’s ability to handle multivariable control problems and incorporate constraints makes it particularly effective for complex path planning tasks in uncertain environments [53];

- Timed Elastic Band (TEB) algorithm optimizes the trajectory of the robot by considering both spatial and temporal constraints. Starting with an initial path, TEB refines it into a time-parametrized trajectory by adjusting the positions and velocities of intermediate points, ensuring adherence to the kinematic constraints of the robot and obstacle avoidance. This optimization process allows the robot to navigate efficiently in dynamic environments, responding adaptively to changes while maintaining smooth and feasible motion [54].

5. Related Works on Underground Mine Path Planning with UGVs

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- A. Kokkinis: T. Frantzis, K. Skordis, G. Nikolakopoulos, and P. Koustoumpardis, “Review of Automated Operations in Drilling and Mining,” Machines 2024, Vol. 12, Page 845, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 845, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Saleh and A. M. Cummings, “Safety in the mining industry and the unfinished legacy of mining accidents: Safety levers and defense-in-depth for addressing mining hazards,” Saf Sci, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 764–777, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Li and K. Zhan, “Intelligent Mining Technology for an Underground Metal Mine Based on Unmanned Equipment,” Engineering, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 381–391, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- “Navigation: Principles of Positioning and Guidance - B. Hofmann-Wellenhof, K. Legat, M. Wieser - Google Books.” Accessed: Feb. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dMXcBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR21&dq=Autonomous+Navigation+book&ots=uo1iWq71W5&sig=TTbM49kTej2P8pRFlHhZ9H-9vlw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- J. M. Roberts, E. S. Duff, and P. Corke, “Reactive navigation and opportunistic localization for autonomous underground mining vehicles,” Inf. Sci., vol. 145, pp. 127–146, 2002, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:1925516.

- K. Ebadi et al., “Present and Future of SLAM in Extreme Underground Environments,” ArXiv, vol. abs/2208.01787, 2022, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:251280074.

- L. Ojeda and J. Borenstein, “Personal Dead-reckoning System for GPS-denied Environments,” in 2007 IEEE International Workshop on Safety, Security and Rescue Robotics, IEEE, Sep. 2007, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Benndorf, J. & Trybała, P. Quantitative analysis of different SLAM algorithms for geo-monitoring in an underground test field. Int J Coal Sci Technol 12, 7 (2025). [CrossRef]

- H. Mäkelä, “Overview of LHD navigation without artificial beacons,” Rob Auton Syst, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 21–35, Jul. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, P. Peng, H. Li, J. Xie, L. Liu, and J. Xiao, “Drilling Path Planning of Rock-Drilling Jumbo Using a Vehicle-Mounted 3D Scanner,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim and Y. Choi, “Development of Autonomous Driving Patrol Robot for Improving Underground Mine Safety,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 3717, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, W. Dong, Y. Su, D. Wu, and Z. Du, “Development of Search-and-rescue Robots for Underground Coal Mine Applications,” J Field Robot, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 386–407, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- “Indoor Wayfinding and Navigation - Google Books.” Accessed: Feb. 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=I3oZBwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Underground+navigation+&ots=yzAGTE7jg8&sig=5ZnjDg4hnXcrh6Z-qbov4UGJwyk&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Underground%20navigation&f=false.

- D. Galar, U. Kumar, and D. Seneviratne, Robots, Drones, UAVs and UGVs for Operation and Maintenance. CRC Press, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Inostroza, I. Parra-Tsunekawa, and J. Ruiz-del-Solar, “Robust Localization for Underground Mining Vehicles: An Application in a Room and Pillar Mine,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 19, p. 8059, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu, X. Wang, X. Yang, H. Liu, J. Li, and P. Wang, “Path planning techniques for mobile robots: Review and prospect,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 227, p. 120254, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Biggie et al., “Flexible Supervised Autonomy for Exploration in Subterranean Environments,” Field Robotics, vol. 3, pp. 125–189, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “Control Theoretic Splines: Optimal Control, Statistics, and Path Planning - Magnus Egerstedt, Clyde Martin - Google Books.” Accessed: Mar. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=crNiMAsPex8C&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Control+theoretic+splines+:+optimal+control,+statistics,+and+path+planning&ots=HPlQKvlHol&sig=zMPZKFWJX-OrCBlJwaO6WDE9yNs#v=onepage&q=Control%20theoretic%20splines%20%3A%20optimal%20control%2C%20statistics%2C%20and%20path%20planning&f=false.

- P. Trybała et al., “MIN3D Dataset: MultI-seNsor 3D Mapping with an Unmanned Ground Vehicle,” PFG – Journal of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Geoinformation Science, vol. 91, no. 6, pp. 425–442, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Peng, J. Pan, Z. Zhao, M. Xi, and L. Chen, “A Novel Obstacle Detection Method in Underground Mines Based on 3D LiDAR,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 106685–106694, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Nielsen, Robust LIDAR-Based Localization in Underground Mines, vol. 1906. Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N.-B. Jing, X. Ma, W. Guo, and M. Wang, “3D Reconstruction of Underground Tunnel Using Depth-camera-based Inspection Robot,” Sensors and Materials, 2019, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:203068830.

- F. Cunha and K. Youcef-Toumi, “Ultra-Wideband Radar for Robust Inspection Drone in Underground Coal Mines,” in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, May 2018, pp. 86–92. [CrossRef]

- N. Ahmad, A. R. Ghazilla, N. M. Khairi, and V. Kasi, “Reviews on Various Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) Sensor Applications”. [CrossRef]

- M. Rodrigues, “Ground Mobile Vehicle Velocity Control using Encoders and Optical Flow Sensor Fusion,” 2016. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:202662013.

- K.-Q. Liu, S.-S. Zhong, K. Zhao, and Y. Song, “Motion control and positioning system of multi-sensor tunnel defect inspection robot: from methodology to application,” 123AD. [CrossRef]

- M. Quigley, “ROS: an open-source Robot Operating System,” in IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2009. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:6324125.

- M. Aljamal, S. Patel, and A. Mahmood, “Comprehensive Review of Robotics Operating System-Based Reinforcement Learning in Robotics,” Applied Sciences, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 1840, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Al-Batati, A. Koubaa, and M. Abdelkader, “ROS 2 in a Nutshell: A Survey,” Oct. 16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Mastering ROS for Robotics Programming: Design, build, and simulate complex ... - Lentin Joseph, Jonathan Cacace - Google Books.” Accessed: Mar. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MulODwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=ROS+(Robot+operation+system)+evolution+and+versions&ots=Cmk4PZqYpN&sig=h0r8m5qs0X8cTNqax9UzVsi8nf8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=ROS%20(Robot%20operation%20system)%20evolution%20and%20versions&f=false.

- Agha et al., “NeBula: Quest for Robotic Autonomy in Challenging Environments; TEAM CoSTAR at the DARPA Subterranean Challenge,” Mar. 2021.

- R. Losch, S. Grehl, M. Donner, C. Buhl, and B. Jung, “Design of an Autonomous Robot for Mapping, Navigation, and Manipulation in Underground Mines,” in 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, Oct. 2018, pp. 1407–1412. [CrossRef]

- S. Thrun, “Learning metric-topological maps for indoor mobile robot navigation,” Artif Intell, vol. 99, no. 1, pp. 21–71, Feb. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Gil, Ó. Reinoso, A. Vicente, C. Fernández, and L. Payá, “Monte Carlo Localization Using SIFT Features,” 2005, pp. 623–630. [CrossRef]

- L. Yang et al., “Path Planning Technique for Mobile Robots: A Review,” Machines, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 980, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Javaid, “Understanding Dijkstra Algorithm,” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. E. Hart, N. J. Nilsson, and B. Raphael, “A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths,” IEEE Transactions on Systems Science and Cybernetics, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 100–107, 1968. [CrossRef]

- S. Koenig and M. Likhachev, “D*lite,” AAAI/IAAI, 2002.

- S. M. LaValle, “Rapidly-exploring random trees: a new tool for path planning,” The annual research report, 1998, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:14744621.

- S. Karaman and E. Frazzoli, “Optimal kinodynamic motion planning using incremental sampling-based methods,” in 49th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), IEEE, Dec. 2010, pp. 7681–7687. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Kavraki, P. Švestka, J. C. Latombe, and M. H. Overmars, “Probabilistic roadmaps for path planning in high-dimensional configuration spaces,” IEEE Trans. Robotics Autom., vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 566–580, 1996. [CrossRef]

- “Genetic algorithms in search, optimization, and machine learning: Goldberg, David E. (David Edward), 1953-: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet Archive.” Accessed: Feb. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://archive.org/details/geneticalgorithm0000gold.

- J. Kennedy and R. Eberhart, “Particle Swarm Optimization-Neural Networks, 1995. Proceedings., IEEE International Conference on,” 2004.

- M. Dorigo and L. M. Gambardella, “Ant colony system: A cooperative learning approach to the traveling salesman problem,” IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 53–66, 1997. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Sutton and A. G. Barto, “Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction Second edition, in progress”.

- J. C. H. Watkins and P. Dayan, “Q-learning,” Machine Learning 1992 8:3, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 279–292, May 1992. [CrossRef]

- V. Mnih et al., “Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning,” Nature 2015 518:7540, vol. 518, no. 7540, pp. 529–533, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Al-Ansarry and S. Al-Darraji, “Hybrid RRT-A*: An Improved Path Planning Method for an Autonomous Mobile Robots,” Journal of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, vol. 17, pp. 1–9, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:236371326.

- V. Lu, D. Hershberger, and W. D. Smart, “Layered costmaps for context-sensitive navigation,” IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, pp. 709–715, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Fox, W. Burgard, and S. Thrun, “The Dynamic Window A pproach t o C o llision Avoidance”.

- Khatib, “REAL-TIME OBSTACLE AVOIDANCE FOR MANIPULATORS AND MOBILE ROBOTS.,” International Journal of Robotics Research, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 90–98, 1986. [CrossRef]

- J. Borenstein, Y. Koren, and S. Member, “THE VECTOR FIELD HISTOGRAM-FAST OBSTACLE AVOIDANCE FOR MOBILE ROBOTS,” IEEE Journal of Robotics and Automation, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 278–288, 1991.

- J. Li, J. Sun, L. Liu, and J. Xu, “Model predictive control for the tracking of autonomous mobile robot combined with a local path planning,” Measurement and Control, vol. 54, no. 9–10, pp. 1319–1325, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yongzhe, B. Ma, and C. K. Wai, “A Practical Study of Time-Elastic-Band Planning Method for Driverless Vehicle for Auto-parking,” 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Autonomous Systems, ICoIAS 2018, pp. 196–200, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chang, Y. Wang, Y. Cai, S. Li, and F. Gao, “Fusion of improved RRT and ant colony optimization for robot path planning,” Engineering Research Express, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 045247, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. D. Sharma, J. Lee, M. Andrews, and I. H. Hadži’c, “Hybrid Classical/RL Local Planner for Ground Robot Navigation,” Oct. 2024, Accessed: Feb. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2410.03066.

- L. Liu, X. Wang, X. Yang, H. Liu, J. Li, and P. Wang, “Path planning techniques for mobile robots: Review and prospect,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 227, p. 120254, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Yang et al., “Path Planning Technique for Mobile Robots: A Review,” Machines, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 980, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Liu, Z. Huang, C. Wang, Z. An, X. Meng, and J. Zheng, “Path planning of underground mining area transportation scene based on improved A * algorithm,” in 2023 7th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), IEEE, Aug. 2023, pp. 2265–2270. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yulong, M. Qingyong, and T. Xu, “Research on Navigation Path Planning for An Underground Load Haul Dump,” Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Review, vol. 8, pp. 102–109, 2015, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:116378442.

- B. A. O. Jiu-sheng et al., “Underground driverless path planning of trackless rubber tyred vehicle based on improved A* and artificial potential field algorithm,” Journal of China Coal Society, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 1347–1360, 2022, [Online]. Available: https://www.mtxb.com.cn/en/article/id/d7bec14d-e1ed-4d3d-9990-eb127b3e130c.

- C. Zhang, X. Yang, R. Zhou, and Z. Guo, “A Path Planning Method Based on Improved A* and Fuzzy Control DWA of Underground Mine Vehicles,” Applied Sciences 2024, Vol. 14, Page 3103, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 3103, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhu, Y. Zhang, J. Wang, K. Ren, and K. Yang, “Evaluation of Motion Planning Algorithms for Underground Mobile Robots,” 2022, pp. 368–379. [CrossRef]

- C. Gu, S. Liu, H. Li, K. Yuan, and W. Bao, “Research on hybrid path planning of underground degraded environment inspection robot based on improved A* algorithm and DWA algorithm,” Robotica, pp. 1–22, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Zhang, Y. Zhang, C. Zhang, J. Cheng, G. Shen, and X. Wang, “Path planning for unmanned load–haul–dump machines based on a VHF_A* algorithm,” Proc Inst Mech Eng C J Mech Eng Sci, vol. 238, no. 13, pp. 6584–6597, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma and R. Mao, “Path planning for coal mine robot to avoid obstacle in gas distribution area,” Int J Adv Robot Syst, vol. 15, no. 1, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Xu and S. Yao, “Research on UGV Path Planning in Tunnel Based on the Dijkstra*-PSO* Algorithm,” in 2022 6th Asian Conference on Artificial Intelligence Technology (ACAIT), IEEE, Dec. 2022, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, “Path Planning Method for Underground Survey Robot in Dangerous Scenarios,” Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology, vol. 43, pp. 207–214, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Ma, J. Lv, and M. Guo, “Downhole robot path planning based on improved D* algorithmn,” in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC), IEEE, Aug. 2020, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, G. Li, J. Hou, L. Chen, and N. Hu, “A Path Planning Method for Underground Intelligent Vehicles Based on an Improved RRT* Algorithm,” Electronics (Basel), vol. 11, no. 3, p. 294, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Hopfenblatt and N. Axel., “A combined RRT*-optimal control approach for kinodynamic motion planning for mobile robots,” 2016. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:203702248.

- J. Wu, L. Zhao, and R. Liu, “Research on Path Planning of a Mining Inspection Robot in an Unstructured Environment Based on an Improved Rapidly Exploring Random Tree Algorithm,” Applied Sciences 2024, Vol. 14, Page 6389, vol. 14, no. 14, p. 6389, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Steinbrink, P. Koch, B. Jung, and S. May, “Rapidly-Exploring Random Graph Next-Best View Exploration for Ground Vehicles,” Aug. 2021, Accessed: Jan. 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2108.01012.

- B. Song, H. Miao, and L. Xu, “Path planning for coal mine robot via improved ant colony optimization algorithm,” Systems Science & Control Engineering, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 283–289, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Xu, Y. R. Huang, and G. Y. Xu, “A path optimization algorithm for the mobile robot of coal mine based on ant colony membrane algorithm,” ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Shao, G. Wang, R. Zheng, B. Wang, T. Yang, and S. Liu, “Path Planning for Mine Rescue Robots Based on Improved Ant Colony Algorithm,” in 2022 8th International Conference on Control, Automation and Robotics (ICCAR), IEEE, Apr. 2022, pp. 161–166. [CrossRef]

- K. Liu and M. Zhang, “Path planning based on simulated annealing ant colony algorithm,” Proceedings - 2016 9th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design, ISCID 2016, vol. 2, pp. 461–466, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Fang et al., “Real-time path planning of drilling robot using global and local sensor information fusion: mining-oriented validation,” The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, vol. 135, no. 11–12, pp. 5875–5891, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Li and H. Zhu, “Immune Optimization of Path Planning for Coal Mine Rescue Robot,” 2016. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:13507361.

- Y. Gao, Z. Dai, and J. Yuan, “A Multiobjective Hybrid Optimization Algorithm for Path Planning of Coal Mine Patrol Robot,” Comput Intell Neurosci, vol. 2022, pp. 1–10, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang and Q. Zeng, “Online Unmanned Ground Vehicle Path Planning Based on Multi-Attribute Intelligent Reinforcement Learning for Mine Search and Rescue,” Applied Sciences 2024, Vol. 14, Page 9127, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 9127, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- [Y. Jiang, P. Peng, L. Wang, J. Wang, J. Wu, and Y. Liu, “LiDAR-Based Local Path Planning Method for Reactive Navigation in Underground Mines,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 15, no. 2, p. 309, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Zi-jian, G. A. O. Xue-hao, and Z. Meng-xia, “Path planning based on the improved artificial potential field of coal mine dynamic target navigation,” Journal of China Coal Society, vol. 41, no. S2, pp. 589–597, 2016. [CrossRef]

| Factors | Mine | Indoor | Outdoor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Conditions | Irregular surfaces, narrow passages, mud |

Smooth and structured surfaces | Varied surfaces |

| Obscurants | Dust, smoke, gas | Nearly clear | Rain, fog and snow |

| GPS Availability | GPS denied | Available with extended setups | Widely available and effective |

| Obstacle Density | Relatively high | Low | Moderate |

| Requirements | Evaluation criteria |

|---|---|

| Optimal path | Minimal travel time and path length |

| Smoothness | Spatial and temporal smoothness coefficients [18] |

| High accuracy and safety | Avoids obstacles and ensures collision-free path |

| Success rate | Percentage of successful path completions |

| Computational cost | Processing time and resource consumption |

| Robustness | Ability to handle uncertainties |

| Handling narrow tunnels | Minimum passable width |

| Sensors | Strengths | Weaknesses | Range and frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiDAR 3D [20] | Works well in low-light environments; |

Performance can degrade in dust, smoke or reflective surfaces; | 10 – 300 m; 10 – 100 Hz |

| High accuracy in 3D mapping and obstacle detection. | High power consumption. | ||

| Laser scanner 2D [21] | Works in low-light environments; | Performance may degrade in heavy particulate environments; | 0,5 - 25 m; 10 – 100 Hz |

| Provides precise distance Measurements. |

Computationally Intensive. | ||

| Depth Camera [22] | Provides both color (RGB) and depth (D) information; | Sensitive to reflective and transparent surfaces; |

0.2 – 10 m; 30 – 90 Hz |

| Compact and lightweight | Can be disrupted by dust or fog. | ||

| Radar [23] | Works in harsh environments (Dust, smoke); | Difficult to interpret data without additional processing; |

0.1 – 250 m; 10 – 200 Hz |

| Reliable for detecting dynamic Objects. | Lower resolution. | ||

| IMU [24] | Small, lightweight, and power-efficient; | Susceptible to external vibrations and sensor noise; |

100 – 1000 Hz |

| Provides high-frequency motion data. | Accumulates drift over time. | ||

| Motor Encoder [25] | Simple integration with UGV control systems; | Accumulates drift over long distances (wheel slippage); |

10 – 1000 Hz |

| High frequency data. | Not reliable for rough terrain or slippery surfaces. |

| Algorithms | Strength | Weakness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dijkstra | Guarantees the shortest path; | Computationally intensive; | |

| Works well in static environments. | Inefficiency in dynamic environment. | ||

| A* | Fast and Efficient; | Heuristic sensitivity; | |

| Guarantees optimal path. | Slow in high-dimensional spaces. | ||

| D* | Efficient replanning; | Higher memory usage; | |

| Handles dynamic obstacles well. | Slower with frequent changes. | ||

| RRT* | Efficient in high-dimensional spaces; | Paths are not always smooth; | |

| Incremental path improvement. | Slower in narrow passages. | ||

| PRM | Reusable path for repeated queries; | Paths are not always smooth; | |

| Works well in large, open spaces. | Struggles with dynamic obstacles. | ||

| GA | Efficient in high-dimensional spaces; | Slow convergence; | |

| Works well with noisy data. | No guarantee of finding optimal path. | ||

| PSO | Simple to implement; | Prone to local minima; | |

| Adaptive to dynamic environments. | Sensitive to parameter selection. | ||

| ACO | Good for multi-agent path planning; | Computationally intensive; | |

| Works in dynamic environments. | Slower convergence. | ||

| Q-Learning | Works with Partial Information; | Higher memory usage; | |

| Can Handle Complex Environments. | Slow convergence in large spaces. | ||

| DQN | Suitable for high-dimensional spaces; | Requires high computational power; | |

| Works with Partial Observability. | Sensitive to parameter selection. | ||

| DWA | Smooth and feasible paths; | Prone to local minima; | |

| Computationally lightweight. | Struggles with complex environment. | ||

| APF | Lightweight, fast obstacle avoidance; | Prone to local minima; | |

| Simple, best for reactive navigation. | Struggles with dynamic obstacles. | ||

| VFH | Efficient real-time obstacle avoidance; | Prone to local minima; | |

| Handles noisy sensor data well. | Oscillations in Narrow Spaces. | ||

| MPC | Optimizes performance; | Computationally intensive; | |

| Generates smooth and efficient paths. | Limited real-time application. | ||

| TEB | Generates smooth, time-optimal path; | Computationally intensive; | |

| Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance. | Sensitive to parameter selection. | ||

| Author | Path type | Basic algorithms |

Optimization Strategy | Test field | Advantages | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [59] | Global | A* | Gaussian filtering method; | MATLAB | Safe path; | LHD in mining transportation |

| Quadratic programming method. | Smoother. | |||||

| [60] | Global | A* | Expanding nodes by articulation angle; | Indoor; C++. | Enhanced search efficiency; |

LHD in mining transportation |

| Collision threat cost. | Collision free. | |||||

| [61] | Global Local |

A* + APF | Exponential function weighting; | MATLAB; Indoor. | Smoother path; | Transportation in coal mine |

| Cubic spline interpolation; | More robust; | |||||

| Repulsion potential field correction factor. | Guarantied safety. | |||||

| [62] | Global Local |

A*+ DWA | Key node selection strategy; | MATLAB; Indoor. | Safety; | Vehicle in mine transportation |

| Clamped-B spline; | Smoother path; | |||||

| Fuzzy control. | Optimal path. | |||||

| [63] | Global Local | A*+DWA | - | Indoor | Shortest path; | Mobile robot in inspection |

| Smoothest path. | ||||||

| [64] | Global Local | A*+DWA | Floyd Algorithm; | MATLAB; Indoor. | Local optima solution | Inspection robot in coal mine |

| B-Spline curves. | ||||||

| [65] | Global | VFH-A* | Bezier interpolation; | MATLAB; Mine. |

More efficiency search; | LHD in mining operation |

| Smooth path; | ||||||

| Fast calculation speed. | ||||||

| [66] | Global Local |

Dijkstra -ACO | MAKLINK lines. | Mine | Smooth path | Robot in SAR |

| Shifting locally; | ||||||

| Symmetric polynomial curve. | ||||||

| [67] | Global | Dijkstra- PSO | PSO-based optimization | MATLAB | Shorter path; | Mine mapping and inspection |

| Safety. | ||||||

| [68] | Global | Dijkstra | 3D Environment-based adaptation | MATLAB | Feasible path | Survey robot in mine exploration |

| [69] | Global | D* | Manhattan distances | MATLAB | Safer path; | Downhole robot in mine detection |

| Reduced planning time and cost. | ||||||

| [70] | Global | RRT* | Vectorized map; | Python | Shorter path; | LHD in mining operations |

| Optimal tree reconnection. | Smoother. | |||||

| [71] | Global | RRT* | Line corner | MATLAB; Outdoor. |

Smooth path; | Robotic excavator loader in excavation |

| Better in narrow passages with tight turn; | ||||||

| [72] | Global | RRT- PRM | Fan-shaped goal orientation; | MATLAB; Indoor. |

Higher success rate; | Inspection robot in Mining |

| Adaptive step size expansion; | Smoother path; | |||||

| Third-order Bessel curve. | Shorter path length. | |||||

| [73] | Global | RRG1 | Ray tracing method; | Gazebo | Shorter path; | Mobile Robot in Mine rescue |

| Next-Best View. | Fast calculation. | |||||

| [74] | Global | ACO | Retreat-punishment strategy; | MATLAB | Consumes less costs | Coal mine robot |

| Serial number and Cartesian coordinate methods. | ||||||

| [75] | Local | ACO | Membrane computing | Simulation | Faster convergence; | Mobile robot |

| Better robustness. | ||||||

| [76] | Global | ACO | 16-directional 24-neighbourhood ant search approach; | MATLAB | Improved search efficiency; | Rescue robot in Mine |

| Ant retreat strategy. | U-shaped trap solution; | |||||

| Shorter path. | ||||||

| [77] | Global | ACO | Annealing algorithm; | MATLAB | Strong in robustness; | Mining robot in SAR |

| Entropy increase strategy. | High convergence speed. | |||||

| [78] | Global Local |

ACO+TEB | Pheromone updating model; | MATLAB; Indoor. |

Enhanced search capabilities; | Drilling robot in mining rockburst |

| Faster convergence. | ||||||

| [79] | Global | BFA2-PSA | Tested by traveling salesman problem (TSP) |

MATLAB | Fast convergence speed; | Rescue robot in coal mine |

| Better Robustness | ||||||

| [80] | Global Local |

AFSA3 + DWA | Improved genetic algorithm | MATLAB; Gazebo; Indoor. |

Shorter path; | Patrol robot in mine safety inspection |

| Adaptive trajectory evaluation function | Smoother path. | |||||

| [81] | Global | QLearning | Even gray model; Multi-attribute intelligent. |

MATLAB | Smoother convergence; | UGV in SAR |

| Shorter path; | ||||||

| [82] | Local | Skeleton-Based | Thinning algorithm | Mine | High robustness; | LHD in mining operation |

| Stable; | ||||||

| [83] | Local | APF | Velocity and acceleration fields; | MATLAB; Indoor |

Dynamic collision avoidance; | Mobile robot in coal mine rescue |

| Global potential field line; | ||||||

| Genetic Trust Region Algorithm | Escape local minima. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).