1. Introduction

Postoperative neck hematoma is an uncommon but potentially fatal complication following thyroidectomy. Its occurrence rate, according to what is reported in the literature, reaches up to 6.5% [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

This complication can lead to acute airway obstruction, therefore if its onset is not managed promptly and adequately, serious neurological complications or even the death of the patient may occur. Neck hematoma with airway compromise requires immediate surgical revision of the hemostasis. However, it is important to emphasize that, in most cases, this complication can be managed conservatively [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

In terms of timing of onset, neck hematoma generally occurs within 24 hours after surgery, particularly in the first 6 hours, and is quite rare after 24 hours [

1,

6,

7,

8,

12,

13,

15,

17,

18,

19].

Since the occurrence of this complication is not common, an accurate statistical evaluation of the risk factors is challenging. To date, various risk factors for the onset of postoperative neck hematoma have been reported in the literature: male gender, older age, high blood pressure, higher body mass index, active smoking, postoperative coughing and vomiting, extent of the operation (bilateral thyroid surgery, neck dissection), previous thyroidectomy, low-volume hospitals, low surgeon experience, large thyroid gland, retrosternal goiter, and Graves’ disease [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

As for the impact of antithrombotic drugs, namely antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants, on the occurrence of this complication, studies in the literature report discordant results [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Moreover, in various analyses, antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants are grouped together and considered as a single variable [

6,

8,

9,

10]. Furthermore, with regard to anticoagulants, and specifically direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), to our knowledge, there are only two studies in the literature that take them into consideration [

7,

19]. However, in the study by Oltmann et al. [

19] DOACs were grouped together with traditional oral anticoagulants (vitamin K antagonists), while in the other study, which is our previous multicenter analysis on risk factors for neck hematoma after thyroid surgery, DOACs were considered but did not represent the main subject of the investigation [

7].

The main aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of direct oral anticoagulants on the occurrence of postoperative neck hematoma following thyroidectomy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This is a retrospective, multicenter, international study on patients submitted to thyroidectomy between January 2020 and December 2022.

Data were collected from nine high-volume thyroid surgery centers in Europe:

- General Surgery Unit, Cagliari University Hospital, Monserrato, Italy;

- Endocrine Surgery Unit, University Hospital of Pisa, Pisa, Italy;

- Endocrine and Metabolic Surgery Unit, “Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli

IRCCS”, Rome, Italy;

- Thoracic and Endocrine Surgery Division, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland;

- Minimally Invasive Surgery Unit, Euromedica Kyanous Stavros, Thessaloniki, Greece;

- General Surgery Unit, “Santo Stefano” Hospital, Prato, Italy;

- Endocrine Surgery Unit, Verona University Hospital, Verona, Italy;

- Multifunctional Center of Endocrine Surgery, “Cristo Re” Hospital, Rome, Italy;

- Endocrine Surgery Unity, “San Carlo di Nancy” Hospital - GVM Care and Research, Rome, Italy.

Patients who underwent conventional open thyroidectomy, with or without neck dissection or simultaneous parathyroidectomy, were included in this investigation.

As exclusion criteria, the following were considered: age < 18 years, patients with coagulation disorders (involving platelets and/or coagulation factors), patients taking antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants different from DOACs, and incomplete data.

Based on taking direct oral anticoagulants, patients were divided in two groups: DOAC Group and Control Group.

Demographic and preoperative information, details on the surgical procedure, postoperative hospital stay, histopathologic findings, and complications were evaluated.

2.2. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was to assess the impact of direct oral anticoagulants on the occurrence of postoperative neck hematoma. For this purpose, the incidence of this complication (overall, for neck hematomas managed conservatively, and for those that required surgical revision of hemostasis), the rate of readmission for its occurrence, and the timing of onset of hematomas that required surgical revision of hemostasis were evaluated.

As secondary endpoints, use of drains, operative time, postoperative hospital stay and the other early complications of thyroid surgery (hypoparathyroidism, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, and wound infection) were assessed.

2.3. Perioperative Management of Direct Oral Anticoagulants

Direct oral anticoagulants were discontinued 48-72 hours before surgery (in consideration of renal function) and reintroduced 24-48 hours after the operation (based on the center's practices), without using bridging anticoagulation.

2.4. Surgical Procedure

All thyroidectomies (which included total thyroidectomies, hemithyroidectomies, and completion thyroidectomies) were performed by conventional open approach.

Intermittent or continuous intraoperative nerve monitoring (IONM), energy-based devices (working by means of advanced bipolar, ultrasonic or hybrid energy), and topical hemostatic agents were used according to the preference of the operating surgeon or depending on their availability.

The use of drains was at the surgeon's discretion.

The duration of the surgical procedure was estimated, in minutes, from skin incision to skin closure.

2.5. Assessment of Complications

Postoperative neck hematomas were categorized according to whether or not surgical revision of hemostasis was required. The timing of onset of neck hematomas that required surgical revision of hemostasis was evaluated, in hours, from the end of the operation to the diagnosis of the complication. In this respect, three time intervals have been distinguished: within six hours after the end of surgical procedure, between 7 and 24 hours, and after 24 hours.

Postoperative hypoparathyroidism was defined in the case of iPTH values below the normal range after the surgical procedure (normal range: 10-65 pg/mL).

Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury was diagnosed by means of postoperative fibrolaryngoscopy. After surgery, fibrolaryngoscopy was performed in patients with suspected recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, due to loss of signal at intraoperative nerve monitoring or hoarseness.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistic® (version 30.0.0.0).

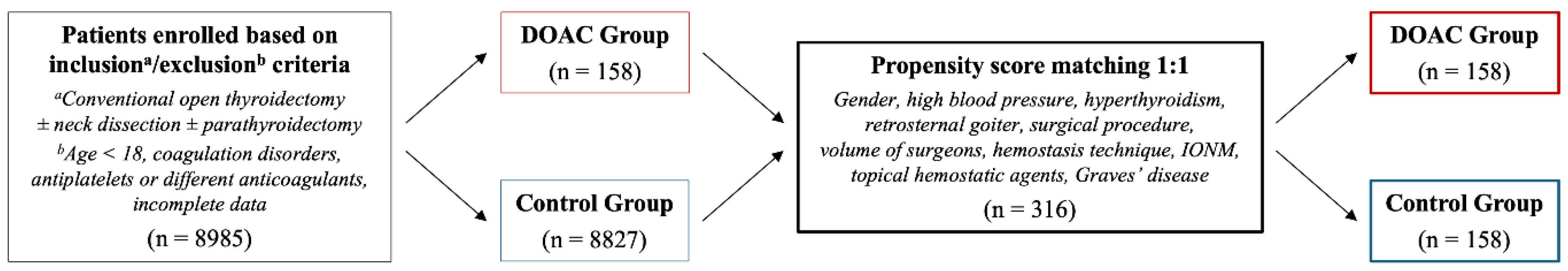

Propensity score matching 1:1 was performed between the two groups. The match tolerance was set at 0.050. “Without replacement” and “Randomize case order when drawing matches” functions were applied. The variables included in this statistical technique were the following: gender, high blood pressure, hyperthyroidism, retrosternal goiter, surgical procedure, volume of surgeons, hemostasis technique, IONM, topical hemostatic agents, and Graves’ disease.

Univariate analysis was employed to compare the two groups. Chi-squared test or Fisher exact test were used, as appropriate, for categorical variables. The presence of a normal distribution of continuous variables was evaluated by means of the Shapiro-Wilks test. Based on the results obtained through the latter test, Mann-Whitney U test was utilized for continuous variables, which were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR).

P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Patients enrolled based on inclusion/exclusion criteria were 8985: 158 in DOAC Group and 8827 in Control Group. Following propensity score matching, the study population consisted of 316 patients: 158 in DOAC Group and 158 in Control Group.

The flowchart regarding the study population is shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. Baseline Features of the Study Population

A statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of age. The median age in DOAC Group (70, IQR 64-76, years) was significantly higher than in Control Group (58, IQR 49-65, years) (P < 0.001).

The other variables were comparable.

Complete results are reported in

Table 1.

3.2. Occurrence of Postoperative Neck Hematoma

The overall incidence of neck hematoma in the study population was 5.06% (3.48% for neck hematomas managed conservatively, and 1.58% for those that required surgical revision of hemostasis).

In DOAC Group, the overall incidence of neck hematoma was 5.70% (4.43% for neck hematomas managed conservatively, and 1.27% for those that required surgical revision of hemostasis).

In Control Group, the overall incidence of neck hematoma was 4.43% (2.53% for neck hematomas managed conservatively, and 1.90% for those that required surgical revision of hemostasis).

No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of incidence of this complication (

Table 2).

Readmission for this complication was not observed in any patient.

The timing of onset of neck hematomas that required surgical revision of hemostasis in the study population was: within six hours after the end of the surgical procedure in 2 (40%) patients, and between 7 and 24 hours in 3 (60%). No patient developed this complication after 24 hours from the end of surgery.

In DOAC Group, the timing of onset of neck hematomas that required surgical revision of hemostasis was: within six hours after the end of the surgical procedure in 1 (50%) patient, and between 7 and 24 hours in 1 (50%).

In Control Group, the timing of onset of neck hematomas that required surgical revision of hemostasis was: within six hours after the end of the surgical procedure in 1 (33.33%) patient, and between 7 and 24 hours in 2 (66.67%).

No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of timing of onset of neck hematomas that required surgical revision of hemostasis (P = 1.000).

3.3. Secondary Endpoints

No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of use of drains, operative time, postoperative hospital stay, postoperative hypoparathyroidism, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, and wound infection.

Complete results are reported in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first with the specific aim of evaluating the impact of direct oral anticoagulants, considered singularly, on the occurrence of neck hematoma following thyroid surgery [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Nowadays, direct oral anticoagulants, namely apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban and dabigatran, are widely utilized drugs. They exert their effect by means of the inhibition of factor Xa (apixaban, rivaroxaban and edoxaban) or factor IIa (dabigatran) [

20,

21,

22].

DOACs are currently the drugs of choice for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation and for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism [

20,

21,

22].

Unlike traditional oral anticoagulants, such as warfarin and acenocoumarol, DOACs have a lower risk of bleeding, a stable pharmacokinetic profile that allows for standardized dosing with no need for routine monitoring, and fewer potential interactions with other drugs [

20,

21,

22].

In light of these advantages, since their introduction on the market between 2008 and 2015, the prescription of these drugs has progressively increased over the years. Nowadays, in many countries, DOACs have surpassed vitamin K antagonists, becoming the most widely utilized method of oral anticoagulation. In the United States, about 4 million patients are currently in therapy with DOACs. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that about 20% of patients treated with DOACs undergo an elective or urgent procedure every year [

20,

21,

22].

In the case of elective surgery, it is necessary to discontinue these drugs in the perioperative period, without, however, the need for bridging anticoagulation. The timing of the interruption and reintroduction is based mainly on the bleeding risk associated with the operation, but also on the type of anatomical area involved in the surgical procedure. In fact, regarding this last point, it is important to emphasize that bleeding after operations involving closed anatomical spaces, even if the risk of developing this complication is not considered high, as in the case of thyroidectomy, can lead to very serious consequences. Regarding the interruption, it is also necessary to take into account the patient's renal function [

20].

In patients of our study, DOACs were discontinued 48-72 hours before surgery (in consideration of renal function) and reintroduced 24-48 hours after the operation (based on the center's practices).

In order to evaluate the impact of direct oral anticoagulants on the occurrence of neck hematoma following thyroidectomy, which represents the primary endpoint of this study, an analysis was conducted on the incidence of this complication (overall, for neck hematomas managed conservatively and for those that required surgical revision of the hemostasis), the readmission rate for its occurrence and the timing of onset of hematomas that required surgical revision of the hemostasis. Furthermore, as secondary endpoints, use of drains, operative time, postoperative hospital stay and the other early complications of thyroidectomy (recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, hypoparathyroidism and wound infection) were evaluated.

In order to balance the two groups analyzed, both from a numerical point of view and with regard to the baseline features, propensity score matching (1:1) was performed. The variables included in this statistical technique were the following: gender, high blood pressure, hyperthyroidism, retrosternal goiter, surgical procedure, volume of activity of the surgeons, hemostasis technique, intraoperative neuromonitoring, topical hemostatic agents, and Graves' disease. These variables were included in consideration of their possible impact on the endpoints of the study [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Differently, age was not included despite having been reported by some authors as a risk factor for postoperative neck hematoma [

7,

8,

9,

10,

14]. This variable, in the comparison between the two groups, was significantly higher in patients treated with DOACs. This result can be attributed to the fact that therapy with direct oral anticoagulants is more commonly taken by older patients. This variable was not included in the propensity score matching in order not to exclude from the study population, and in particular from the Control Group, a very relevant category of patients who undergo thyroid surgery, namely that consisting of younger individuals. This methodological choice, in our opinion, makes the obtained results more generalizable.

In our analysis, in the study population, the overall incidence of neck hematoma was 5.06% (3.48% for neck hematomas managed conservatively, and 1.58% for those that required surgical revision of hemostasis). In patients treated with DOACs, the overall incidence of neck hematoma was 5.70% (4.43% for neck hematomas managed conservatively, and 1.27% for those that required surgical revision of hemostasis). Regarding incidence rates, no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups. It is important to emphasize that this result was obtained even though patients in therapy with DOACs were significantly older, and therefore, according to what has been described by some authors, at greater risk for developing postoperative neck hematoma.

With regard to readmission for this complication, it was not observed in any patient in the study population.

The timing of the onset of neck hematomas that required surgical revision of the hemostasis in the study population was: within six hours of the end of surgery in 2 (40%) patients, and between 7 and 24 hours in 3 (60%). No patient developed this complication 24 hours after the end of the surgical procedure. In patients treated with DOACs, the timing of onset of neck hematomas that required surgical revision of hemostasis was: within six hours after the end of the surgical procedure in 1 (50%) patient, and between 7 and 24 hours in 1 (50%). Also with regard to this result, no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups.

Our findings about incidence rates of this complication are comparable to those reported by other authors [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. With regard to the timing of onset of neck hematomas that required surgical revision of the hemostasis, there was not a prevalence of occurrence in the first six hours, as described in other studies. This result was very probably influenced by the small number of cases examined. However, it is important to emphasize that in all patients this complication developed within 24 hours [

1,

6,

7,

8,

12,

13,

15,

17,

18,

19].

Concerning use of drains, operative time, postoperative hospital stay, and the other early complications of thyroidectomy, namely the secondary endpoints, the comparison between the two groups, also in this case, showed no statistically significant differences. The results regarding operative times, but also complications, reveal that there were no particular additional intraoperative difficulties in patients treated with DOACs.

The main limitation of this study is the retrospective nature of our analysis, therefore at risk of bias. However, in this regard, it is important to emphasize that the application of propensity score matching, through which the two groups were balanced, has certainly limited bias, giving greater value to the results obtained. Another limitation, again related to the retrospective nature of the study, concerns the fact that for neck hematomas managed conservatively it was not possible to evaluate the timing of onset, as this information was available only for a very small number of cases.

5. Conclusions

This study showed that, in the field of thyroid surgery, direct oral anticoagulants have no impact on the occurrence of postoperative neck hematoma, nor on other surgical outcomes. Therefore, based on our findings, it can be concluded that thyroidectomy, in patients taking this class of drugs, can be safely performed and without any particular additional technical difficulties.

However, considering the limitations of our investigation, further studies, preferably prospective and with larger populations, are needed to better examine this subject.

Author Contributions

G.L.C. and F.M., conception and design of the study, literature search, and was involved in drafting the manuscript; F.C., G.L. (Giulia Lanzolla), L.R., F.P., G.D.F. and A.C., conception and design of the study and was involved in drafting the manuscript; P.G., A.D.P., C.E.A., I.P., M.M., V.L.-G., B.B., G.S., S.E.T., G.C., A.M., G.L. (Giovanni Lazzari), T.G., and M.I., acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and literature search; F.B., E.M., F.F., E.T., P.P., M.S.D., T.P., M.R., G.M., C.D.C and P.G.C., conception and design of the study and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union—NextGenerationEU through the Italian Ministry of University and Research under PNRR–M4C2-I1.3 Project PE_00000019 “HEAL ITALIA” to Fabio Medas CUPF53C22000750006 University of Cagliari. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee (Independent Ethics Committee, A.O.U. Cagliari; project identification code: NP/2023/953, date of approval: 01 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the RAGNO Study Collaborative Group for their efforts in collecting data. RAGNO Study Collaborative Group: Silvia Corrias, Eugenia Ercoli, Chiara Mura, Erica Ragno, Serena Romano, Matteo Pezzotti, Francesco Giudice, Livia Palmieri, Priscilla Francesca Procopio, Annamaria Martullo, Luca Sessa, Georgios Kotsovolis, Despoina Tsalkatidou, Angeliki Vouchara, Ilaria Di Meglio, Nathalie Massé, Giulia Fiorenza, Giulia Cerino, Luca Romoli, Casimiro Nigro, Sofia Astolfi, Francesco Boscherini, Antonio Evangelista, Chiara Bellantone, Dorin Serbusca, Giulia Gobbo, Giuditta Maulu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- de Carvalho, A.Y.; Gomes, C.C.; Chulam, T.C.; Vartanian, J.G.; Carvalho, G.B.; Lira, R.B.; Kohler, H.F.; Kowalski, L.P. Risk Factors and Outcomes of Postoperative Neck Hematomas: An Analysis of 5,900 Thyroidectomies Performed at a Cancer Center. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 25, e421–e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, H.E.; Wiseman, S.M.; Palazzo, F.F.; Chadwick, D.; Aspinall, S. Post-thyroidectomy bleeding: analysis of risk factors from a national registry. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 108, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Materazzi, G.; Ambrosini, C.E.; Fregoli, L.; De Napoli, L.; Frustaci, G.; Matteucci, V.; Papini, P.; Bakkar, S.; Miccoli, P. Prevention and management of bleeding in thyroid surgery. Gland Surg. 2017, 6, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Cai, Y.; Li, Q.; Cheng, P.; Ni, C.; Jin, L.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, X.; Jin, C. Risk factors target in patients with post-thyroidectomy bleeding. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 1837–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Quimby, A.E.; Wells, S.T.; Hearn, M.; Javidnia, H.; Johnson-Obaseki, S. Is there a group of patients at greater risk for hematoma following thyroidectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.J.; McCoy, K.L.; Shen, W.T.; Carty, S.E.; Lubitz, C.C.; Moalem, J.; Nehs, M.; Holm, T.; Greenblatt, D.Y.; Press, D.; et al. A multi-institutional international study of risk factors for hematoma after thyroidectomy. Surgery 2013, 154, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canu, G.L.; Medas, F.; Cappellacci, F.; Rossi, L.; Gjeloshi, B.; Sessa, L.; Pennestrì, F.; Djafarrian, R.; Mavromati, M.; Kotsovolis, G.; Pliakos, I.; Di Filippo, G.; Lazzari, G.; Vaccaro, C.; Izzo, M.; Boi, F.; Brazzarola, P.; Feroci, F.; Demarchi, M.S.; Papavramidis, T.; Materazzi, G.; Raffaelli, M.; Calò, P.G.; REDHOT Study Collaborative Group. Risk factors for postoperative cervical haematoma in patients undergoing thyroidectomy: a retrospective, multicenter, international analysis (REDHOT study). Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1278696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Yasunaga, H.; Matsui, H.; Fushimi, K.; Saito, Y.; Yamasoba, T. Factors Associated With Neck Hematoma After Thyroidectomy: A Retrospective Analysis Using a Japanese Inpatient Database. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, W.; Dong, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H. Risk factors for post-thyroidectomy haemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 176, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhou, X.; Su, G.; Zhou, Y.; Su, J.; Luo, M.; Li, H. Risk factors for neck hematoma requiring surgical re-intervention after thyroidectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2019, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canu, G.L.; Medas, F.; Cappellacci, F.; Giordano, A.B.F.; Casti, F.; Grifoni, L.; Feroci, F.; Calò, P.G. Does the continuation of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid during the perioperative period of thyroidectomy increase the risk of cervical haematoma? A 1-year experience of two Italian centers. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 1046561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tausanovic, K.; Zivaljevic, V.; Grujicic, S.S.; Jovanovic, K.; Jovanovic, V.; Paunovic, I. Case Control Study of Risk Factors for Occurrence of Postoperative Hematoma After Thyroid Surgery: Ten Year Analysis of 6938 Operations in a Tertiary Center in Serbia. World J. Surg. 2022, 46, 2416–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyre, P.; Desurmont, T.; Lacoste, L.; Odasso, C.; Bouche, G.; Beaulieu, A.; Valagier, A.; Charalambous, C.; Gibelin, H.; Debaene, B.; Kraimps, J.L. Does the risk of compressive hematoma after thyroidectomy authorize 1-day surgery? Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2008, 393, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chereau, N.; Godiris-Petit, G.; Noullet, S.; Di Maria, S.; Tezenas du Montcel, S.; Menegaux, F. Risk Score of Neck Hematoma: How to Select Patients for Ambulatory Thyroid Surgery? World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Tang, P. Risk factors for and occurrence of postoperative cervical hematoma after thyroid surgery: A single-institution study based on 5156 cases from the past 2 years. Head Neck 2016, 38, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; Anabell, L.; Page, D.; Harding, T.; Gnaneswaran, N.; Chan, S. Risk factors for post-thyroidectomy haematoma. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2016, 130 (Suppl. 1), S20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B.H.; Yih, P.C.; Lo, C.Y. A review of risk factors and timing for postoperative hematoma after thyroidectomy: is outpatient thyroidectomy really safe? World J. Surg. 2012, 36, 2497–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkey, S.H.; van Heerden, J.A.; Thompson, G.B.; Grant, C.S.; Schleck, C.D.; Farley, D.R. Reexploration for symptomatic hematomas after cervical exploration. Surgery 2001, 130, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltmann, S.C.; Alhefdhi, A.Y.; Rajaei, M.H.; Schneider, D.F.; Sippel, R.S.; Chen, H. Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications Significantly Increase the Risk of Postoperative Hematoma: Review of over 4500 Thyroid and Parathyroid Procedures. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 2874–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douketis, J.D.; Spyropoulos, A.C. Perioperative Management of Patients Taking Direct Oral Anticoagulants: A Review. JAMA 2024, 332, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindley, B.; Lip, G.Y.H.; McCloskey, A.P.; Penson, P.E. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of direct oral anticoagulants. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2023, 19, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageno, W.; Caramelli, B.; Donadini, M.P.; Girardi, L.; Riva, N. Changes in the landscape of anticoagulation: a focus on direct oral anticoagulants. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e938–e950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).