1. Introduction

Preoperative laboratory testing plays a critical role in diagnosing underlying conditions, assessing patient risk, and guiding perioperative management. However, routine testing in otherwise healthy individuals often provides limited clinical benefit and can lead to unnecessary healthcare costs and resource utilization. Despite guidelines advising against routine testing for ASA I or II patients undergoing low-risk, minimally invasive procedures, many clinicians continue to order these tests due to a lack of guideline awareness, concern about medico-legal issues, institutional mandates, and financial incentives [

1,

2]. While guidelines provide a framework for clinical practice, they do not replace the need for clinical judgment. A more effective approach would be to selectively conduct laboratory tests based on patient history, physical examination, and medical records, particularly when there are concerning findings or significant changes in the patient’s condition [

1].

Neuraxial blockade is increasingly used as an effective treatment for pain management, particularly in the aging population with a high prevalence of degenerative diseases. While this procedure is generally safe and can be performed on an outpatient basis, it carries potential risks such as bleeding, infection, and neurological complications, making pre-procedural evaluation crucial [

3]. Despite the importance of pre-procedural blood tests (PBTs) in identifying risk factors and ensuring patient safety [

4,

5], there is a lack of clear evidence and guidelines on their use specifically for neuraxial procedures in outpatient settings. This ambiguity in clinical practice may lead to both overuse and underuse of PBTs, potentially impacting patient outcomes. This study aims to address this gap by evaluating the necessity and utility of routine PBTs in patients undergoing neuraxial blockade. We conducted a retrospective analysis of pre-procedural blood tests performed at our outpatient pain clinic from January 2020 to August 2023. Our objective is to determine whether these tests provide significant clinical value in predicting and preventing complications associated with neuraxial procedures, and to identify patient factors that may be associated with abnormal test results.

Through this study, we seek to answer the following questions: Do routine PBTs offer substantial clinical value in the context of neuraxial blockade? Can specific patient factors predict abnormal test results that might alter clinical management? By addressing these questions, we hope to contribute to the development of more evidence-based guidelines for pre-procedural evaluation, ultimately reducing unnecessary testing and focusing resources on patients who would benefit most from targeted assessments. Our findings could play a crucial role in improving the safety and efficiency of neuraxial procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

After obtaining a waiver for the requirement of consent from our Institutional Review Board (HP IRB 2024-06-010), due to the retrospective nature of the study, we gathered data from the medical records of outpatients who visited a pain clinic between 2020.1 and 2023.8 and underwent blood tests for a neuraxial procedure. At our clinic, prior to conducting neuraxial procedures, blood tests are performed with patient consent to ensure the safety of the intervention. We reviewed patient records obtained through an initial electronic search, which included patient demographics, comorbidities, and pain-specific information from our electronic medical records. The patient demographics encompassed age, gender, height, weight, body mass index (BMI) and the presence of comorbidities such as a history of diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), coronary artery obstructive disease (CAOD) or arrhythmia, chronic renal insufficiency (CRI), or cancer. We excluded cases where patients were considered cured after five years of cancer treatment from the comorbidity list. We recorded pain-specific information as the underlying diagnosis for neuraxial blockade, classifying the underlying diagnoses into categories such as spinal disorders like stenosis and disc disease based on their location, herpes zoster, postherpetic neuralgia, and other pain conditions. Postherpetic neuralgia was defined as pain persisting for more than three months following the rash onset. In this study, PBTs were identified based on blood work performed within two weeks prior to the procedure. The laboratory parameters collected included hemoglobin, white blood cell count (WBC), platelets (PLT), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), blood glucose, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), sodium, potassium, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratio (INR). Abnormal results from the PBTs were identified, and factors associated with these abnormalities were determined.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

In

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3, continuous variables were represented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (%). T-tests were applied to continuous variables that followed a normal distribution; otherwise, Mann-Whitney U tests were utilized. For categorical variables, analyses were conducted using either the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the data’s distribution. Univariate logistic regression was employed to analyze primary variables. The effects of patient variables on abnormal PBT results were assessed using multivariate regression with backward elimination (

p < 0.05). The SPSS software (version 25.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform these analyses.

3. Results

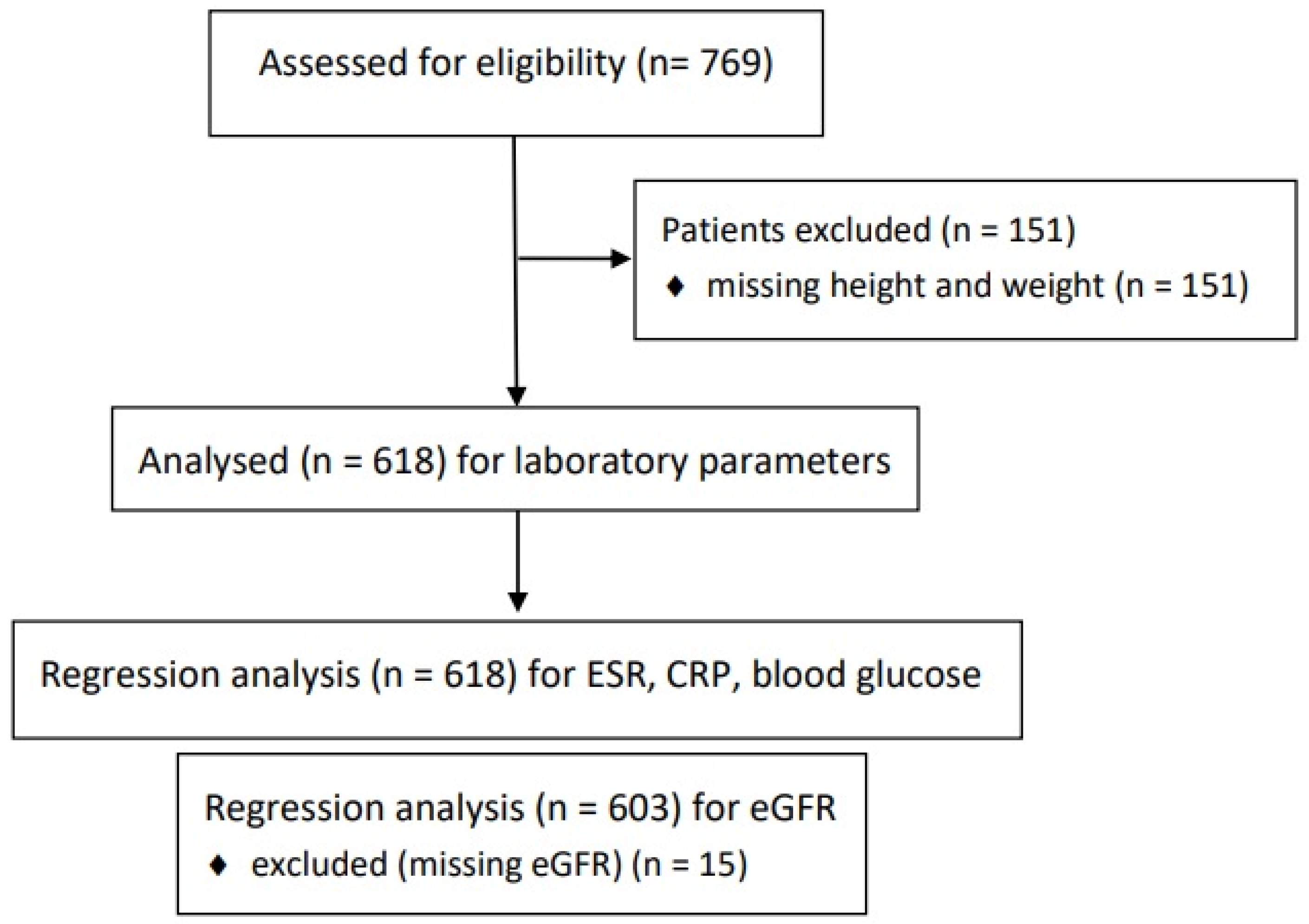

In total, 769 patients were initially selected. Initially, 151 patients lacked height and weight data, resulting in 618 cases of patients who had received PBTs (

Figure 1).

Table 1 displays patient characteristics and clinical data.

Table 2 provides a summary of cases that showed abnormal findings in blood tests. Ten patients were confirmed to have additional diagnoses related to abnormal results identified during the follow-up period (

Table 3).

3.1. WBC, ESR, CRP

Forty-three patients exhibited WBC > 10.0×10

9/L. Seventy-six patients showed an ESR increase exceeding 20 mm/h. Ninety-three patients presented with CRP levels beyond 0.30 mg/dL. No significant difference was observed among the groups with elevated WBC. In cases involving ESR and CRP, predictive factors associated with elevated levels were identified through multivariate regression analysis. Advanced age (

p = 0.001) and a history of CRI (

p = 0.038) correlated significantly with increased ESR (> 20 mm/h). Advanced age (p = 0.026) and a history of cancer (

p = 0.016) were significantly correlated with heightened CRP levels (> 0.30 mg/dL) (

Table 4).

3.2. Glucose

Out of a total of 618 individuals, 96 were identified with high random blood glucose (≥ 140 mg/dL). Among these, 51 had no history of DM. Remarkably, 24 (3.88%) exhibited glucose levels (≥ 200 mg/dL), of whom eight had no prior diagnosis of DM, while sixteen were receiving treatment for known DM. Multivariate regression analysis revealed that a history of cancer (p < 0.001) was significantly associated with severe hyperglycemia (≥ 200 mg/dL) alongside DM history (

p < 0.001) (

Table 4). In univariable analyses, a cancer history was associated with elevated blood glucose (≥ 140 mg/dL) although it was not significant in multivariate analyses (

p = 0.052). Additionally, two cases of previously unrecognized DM were diagnosed with diabetic neuropathy following incidentally discovered hyperglycemia (

Table 3).

3.3. PLT, PT/PTT

Of the 618 individuals, five presented with PLT levels that decreased to below 100 × 10

9/L. One patient, specifically with a count of 51 × 10

9/L, had liver cirrhosis; additionally, among the other four with PLT counts ranging between 70 and 100 × 10

9/L, two had a history of liver disease (cirrhosis, had undergone liver transplantation). There were no significant findings or medical histories in the other cases, and other PBTs were unremarkable. No cases of abnormal INR or significant deviations in PT and aPTT were noted in patients without hereditary bleeding disorders or prior bleeding events (

Table 2).

3.4. eGFR

Out of 618 patients, 603 were analyzed after excluding 15 patients with missing eGFR. Fifty-nine patients exhibited decreased eGFR (< 60mL/min/1.73m

2), among whom 52 (88.14%) had no history of CRI. While this was an isolated case, one male required emergency treatment due to severe unexpected hyperkalemia (

Table 3). The multivariate regression analysis demonstrated that variables such as advanced age (

p < 0.001), history of HTN (

p = 0.012), cancer (

p = 0.019), and CAOD or arrhythmia (p < 0.001) significantly predicted decreased eGFR (

Table 4). Three patients were identified with severe kidney function loss (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m

2): A 64-year-old male and an 85-year-old female with no previous renal insufficiency (

Table 3), while the other patient (eGFR = 11 mL/min/1.73m

2) had been previously treated for HTN and CRI.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

The primary contraindications for neuraxial procedures include sepsis, fever, viral infections, coagulopathy, and preexisting central nervous system disorders [

6]. The rationale for performing PBTs before neuraxial blockade is to detect systemic illnesses, assess coagulation status, evaluate thrombocytopenia, and check renal function, thereby ensuring safe and effective analgesia by identifying potential risk factors. We present significant findings from PBTs based on retrospective results. This population-based study of outpatients indicates that PBTs can selectively identify safety issues that may not be evident from patient history alone.

Do routine PBTs offer substantial clinical value in the context of neuraxial blockade?

This study suggests that routine PBTs before neuraxial blockade can provide significant clinical information in certain patient groups. Abnormalities in inflammatory markers such as ESR and CRP were found to help identify undiagnosed infectious conditions, and previously undiagnosed diabetes was discovered through abnormal glucose levels. This indicates that routine PBTs can enhance patient safety and optimize pre-procedural planning in specific situations. However, performing routine PBTs for all patients is not clinically justified, and a selective approach is necessary.

Can specific patient factors predict abnormal test results that might alter clinical management?

The study found that specific patient factors, such as advanced age, history of cancer, and diabetes, were significantly associated with abnormal blood test results, and these factors can have a substantial impact on clinical management. For example, elevated ESR and CRP levels were more likely in patients with advanced age or a history of cancer, indicating a higher risk of infection or inflammatory conditions. Additionally, patients with a history of diabetes often exhibited hyperglycemia, highlighting the need for careful glucose monitoring following steroid injections. These findings suggest that patient-specific factors are important considerations when deciding whether to perform routine PBTs.

4.1. WBC, ESR, CRP

Fulminant sepsis or massive site infection are absolute contraindications against neuraxial blockade [

6]. Spinal infection can occur by entry into the epidural space from a contiguous infection (e.g., psoas abscess, osteomyelitis, skin infection), hematogenous spread, or through direct inoculation (e.g., steroid injection, surgery, nerve block, acupuncture) [

7]. Hematogenous spread in bacteremic patients during spinal needle insertion can lead to bleeding into the subarachnoid space, thereby increasing the risk of meningitis [

8]. Experts have advised against performing neuraxial procedures in patients with untreated systemic infection [

9]. However, the level of systemic infection that constitutes a risk factor for infection via hematogenous spread remains undefined. Several markers are considered crucial for diagnosing infectious diseases [

10]. Infections may present with leukocytosis and elevated ESR and CRP levels [

7]. However, the limited sensitivity of the WBC count makes it the least informative [

7]. ESR is a sensitive marker, but it has low specificity. A CRP level can rise dramatically in response to injury, infection, and inflammation, serving both as a marker and an active participant in the inflammatory process [

11]. In previous research, infection was identified as the most frequent cause of elevated CRP levels (55.1%), followed by rheumatologic diseases, other inflammatory conditions, and malignancy [

12]. Specially, CRP is a reliable indicator of spinal infections [

7]. Although there are limitations in diagnosing infectious diseases based solely on blood test results, meticulous evaluation—such as tracking changes through additional tests or other thorough assessments—is often necessary when abnormalities are detected. In our study, various infectious disorders were identified through routine PBTs (

Table 3). Infectious diseases often accompany pain syndromes: cellulitis near prosthetic leg in stump pain, diabetic foot in diabetic neuropathy, pneumonia in elderly and herpes zoster in immunocompromised patients, and septic arthritis or spondylodiscitis in degenerative disorders. As the interventional pain management grows, surgical site infections risks increase [

13]. All identified diseases based on infection-related markers were not considered absolute contraindications for neuraxial blockade, yet the findings provided unexpected clinical insights that could guide the diagnosis and management of patients before procedures. There was a single case of infectious spondylodiscitis identified early based on inflammatory markers: A 47-year-old male with pain radiating to the upper limb presented for a cervical injection. A CT scan conducted two days before his visit showed foraminal stenosis, and laboratory tests indicated leukocytosis (12.95 × 10

9/L) and elevated CRP (2.08 mg/dL). Subsequent tests on the day of his visit confirmed an escalation in inflammatory markers (

Table 3). The patient had no underlying medical conditions but had undergone an invasive neck procedure at another clinic one week prior. An MRI scan confirmed infectious spondylodiscitis with phlegmon and abscess formation. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the blood cultures. The patient recovered following antibiotic treatment.

4.2. Glucose

Preoperative blood glucose testing is considered reasonable in diabetic, obese patients, and those on long-term steroid therapy because there is a correlation between elevated blood glucose postoperative poor outcomes [

14]. Specifically, elevated blood glucose levels have been associated with an increased risk of infections among patients scheduled for various orthopedic surgery [

1]. Maintaining perioperative blood glucose levels below 200 mg/dL is crucial in preventing surgical site infections, regardless of diabetes status, as supported by strong recommendations [

10]. Therefore, pre-procedural glucose testing might be of critical importance, as the elderly population might also be prone to undiagnosed DM.

The most common side effect of steroids used in neuraxial analgesia is elevated blood glucose. Hyperglycemia after epidural injection has been observed in patients both with and without DM [

15], although this glucose elevation has been shown to persist longer in DM than in non-DM patients [

16]. DM patients experience pronounced systemic effects from glucocorticoids due to diminished clearance and extended exposure [

15]. This typically results in an average increase of 125.96 ± 100.97 mg/dL in blood glucose after an epidural injection [

17]. Therefore, DM patients can reasonably expect a temporary elevation of blood glucose by 100 mg/dL or more for approximately 48 to 72 hours following an epidural steroid injection [

17]. This response also depends on the steroid dose used [

18]. It is advisable to exercise caution when administering a neuraxial steroid injection to patients with DM, and frequent glucose monitoring is highly recommended [

19]. If not assessed beforehand, patients with unrecognized hyperglycemia might experience reactions similar to those observed in diabetic patients after steroid injection.

In our study, some patients were not diagnosed with DM but exhibited confirmed hyperglycemia, and there were patients who, while undergoing treatment for DM, were confirmed to have elevated glucose levels. Notably, those with a history of cancer were found to have a risk of elevated blood glucose. Although the underlying mechanisms vary and require further investigation, the relationship between hyperglycemia and tumor development has been previously documented [

20]. Patients who are candidates for neuraxial steroid injection should be informed that an increase in blood glucose may occur post-procedure [

17]. There is no definitive evidence concerning the potential systemic effects of transient hyperglycemia on patients. However, awareness of the patient’s blood glucose level prior to the procedure can reduce steroid use and complications such as hyperglycemia and infection. Effective pain control via neuraxial blockade can occur regardless of steroid administration in some cases [

21]. Physicians should also recognize that, whether in cases of treated DM or undiagnosed DM, well-controlled blood glucose levels cannot always be ensured.

4.3. PLT, PT/PTT

A systematic review indicates that routine coagulation tests, such as PT and PTT, are not effective in predicting postoperative bleeding risk in unselected patients and are therefore not recommended [

1]. These preoperative coagulation studies should be reserved for patients taking anticoagulants, those with a history of bleeding abnormalities, or those with conditions that predispose them to coagulopathy, such as liver disease or malnutrition.

Neuraxial blockade inherently carries some risk of inducing bleeding, especially in patients with pre-existing bleeding diatheses (e.g., thrombocytopenia, coagulation factor deficiencies, renal dysfunction), or those with medically induced coagulation dysfunction. Although bleeding complications are extremely rare with neuraxial procedures, certain bleeding types can lead to severe complications [

22]. Specifically, bleeding within the vertebral column has the potential to cause permanent paralysis if not managed within 8 to 12 hours [

22,

23]. This concern may drive some physicians to routinely order coagulation screening prior to performing neuraxial blockade, although the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of this practice are debatable from the perspectives of evidence-based medicine. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia recommends evaluating the need for coagulation tests (complete blood count, PT, PTT) individually for each patient [

24]. In our study, no patients exhibited abnormal PT or PTT that affected the procedure, even those with comorbidities. PT and PTT screening in low-risk patients was deemed unnecessary. A PLT < 100×10

9/L is generally considered a risk factor for spinal hematoma, but when there are indications for a neuraxial blockade, the risks and benefits to the patient must be weighed [

25]. If the PLT is ≥ 70×10

9/L, there is likely to be a low risk of neuraxial hematoma, allowing for a neuraxial procedure if clinically indicated [

4]. Our results also indicate that patients without underlying disease may have hematologic and coagulation indices within an acceptable range for performing neuraxial blockade. Conducting routine coagulation studies before the blockade may be beneficial if a patient currently has a history of taking anticoagulants (warfarin), suffers from coagulopathy, or has chronic liver disease [

1]. Specifically, hepatic failure results in factor deficiencies and thrombocytopenia [

26].

4.4. eGFR

Kidney function is widely recognized as a crucial determinant of prognosis in various surgical settings [

1,

27]. Several factors underscore the necessity of assessing renal function before administering neuraxial blockade. Firstly, renal dysfunction is identified as a risk factor for vertebral hematoma, along with preexisting coagulopathy, the use of anticoagulation medications, aging, gender, spinal abnormalities, the use of larger needles, and multiple needle attempts [

23]. Uremia is linked to spontaneous hemorrhage, partly due to PLT dysfunction [

5]. Moreover, renal impairment can influence drug metabolism and clearance. Patients with moderate renal impairment encounter an increased risk of spontaneous hemorrhage due to delayed excretion of anticoagulants [

5]. Therefore, extended discontinuation times are recommended before neuraxial blockade. Spinal hematomas have occurred in individuals taking antiplatelet agents, despite adherence to discontinuation protocols [

28]. Consequently, renal function could be considered a critical parameter when evaluating a patient’s bleeding risk. Secondly, contrast media are used both to verify accurate tissue targeting and to confirm the exclusion of flow to non-target tissues in various neuraxial procedures. Assessing renal function beforehand is essential to prevent contrast-induced nephropathy [

29]. Furthermore, although indirectly related to neuraxial blockade, measuring renal function provides valuable insights that can inform the appropriate dosages of gabapentinoids, commonly used as first-line treatments for neuropathic pain in pain clinics. Evaluating renal function might influence the selection and dosage of these medications.

eGFR is known to be effective as a predictor of renal dysfunction [

1] and serves as a reliable test for detecting subclinical renal failure [

27]. Low eGFR is associated with clinical risk factors such as DM, HTN, aging, malignancy, and obesity, yet fewer than 5% of early CRI patients are aware of their condition [

30]. It is also noted that many patients with decreased eGFR demonstrated no prior history of renal dysfunction in this study.

Our study has several limitations. As a cross-sectional analysis, it does not assess the adverse effects of neuraxial blockade in patients with abnormal primary blood tests. Various cases involved additional diagnoses through follow-up tests, resulting in discontinued or improved outcomes. We did not evaluate whether abnormal test results influenced complications or outcomes. Clinical management was adjusted based on the findings, including postponing procedures, further evaluations, or modifying the injectate, as guided by clinical judgment. The absence of established guidelines makes proceeding with abnormal results controversial, necessitating large-scale studies to clarify the associated benefits and risks. Additionally, pre-existing medical information may not adequately explain a patient’s condition in outpatient settings. PBTs can selectively provide valuable predictive information. The retrospective design of our study introduces additional limitations. Patient histories are often self-reported, reducing reliability, and we did not explore comorbidities beyond medical records. The timing of blood tests may not align perfectly with procedures, especially in cases where glucose levels are influenced by meals, as we used random plasma glucose levels.

5. Conclusions

PBTs can provide valuable clinical information that may not be identified through patient informatics and comorbidities prior to performing neuraxial blockade in an outpatient setting. Patient medical comorbidities can serve as a reference for selective blood test screening, although they may not fully account for the patient’s condition.

Author Contributions

Data curation, methodology, investigation, resources, writing—original draft; Sh.M. conceptualization, formal analysis, software, validation, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; D.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Republic of Korea (Protocol code HP IRB 2024-06-010, date of approval 14 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

This retrospective study did not require informed consent by Institutional Review Board because patient recontact was not established.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by “Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Edwards AF, Forest DJ. Preoperative Laboratory Testing. Anesthesiol Clin. 2018;36(4):493-507.

- Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, Pasternak LR, Arens JF, Caplan RA, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(3):522-38.

- Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, Brown KM, Han Y, Townsend CM, Jr., et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;256(3):518-28.

- Bauer ME, Arendt K, Beilin Y, Gernsheimer T, Perez Botero J, James AH, et al. The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Interdisciplinary Consensus Statement on Neuraxial Procedures in Obstetric Patients With Thrombocytopenia. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(6):1531-44.

- Breivik H, Norum H, Fenger-Eriksen C, Alahuhta S, Vigfusson G, Thomas O, et al. Reducing risk of spinal haematoma from spinal and epidural pain procedures. Scand J Pain. 2018;18(2):129-50.

- Jane, C. Ballantyne SMF, James P. Rathmell. Bonica’s Management of Pain. Fifth edition ed. Jane C. Ballantyne NB, DavidJ. Copenhaver. Emad N. Eskandar, editor. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business; 2019.

- Long B, Carlson J, Montrief T, Koyfman A. High risk and low prevalence diseases: Spinal epidural abscess. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;53:168-72.

- Hutter, C.D. Face masks, spinal anaesthesia and meningitis. Anaesthesia. 2008;63(7):781-2; author reply 2.

- Gimeno AM, Errando CL. Neuraxial Regional Anaesthesia in Patients with Active Infection and Sepsis: A Clinical Narrative Review. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2018;46(1):8-14.

- Berrios-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, Leas B, Stone EC, Kelz RR, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):784-91.

- Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ. Role of C-Reactive Protein at Sites of Inflammation and Infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:754.

- Landry A, Docherty P, Ouellette S, Cartier LJ. Causes and outcomes of markedly elevated C-reactive protein levels. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(6):e316-e23.

- Lim S, Yoo YM, Kim KH. No more tears from surgical site infections in interventional pain management. Korean J Pain. 2023;36(1):11-50.

- Akhtar S, Barash PG, Inzucchi SE. Scientific principles and clinical implications of perioperative glucose regulation and control. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(2):478-97.

- Stout A, Friedly J, Standaert CJ. Systemic Absorption and Side Effects of Locally Injected Glucocorticoids. Pm r. 2019;11(4):409-19.

- Younes M, Neffati F, Touzi M, Hassen-Zrour S, Fendri Y, Béjia I, et al. Systemic effects of epidural and intra-articular glucocorticoid injections in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74(5):472-6.

- Even JL, Crosby CG, Song Y, McGirt MJ, Devin CJ. Effects of epidural steroid injections on blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes mellitus. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(1):E46-50.

- Hao C, Yin J, Liu H, Cheng Z, Zeng Y, Jin Y. Pain Reduction and Changes in Serum Cortisol, Adrenocorticotropic Hormone, and Glucose Levels after Epidural Injections With Different Doses of Corticosteroid. Pain Physician. 2024;27(1):E119-e29.

- Liu XH, Du YM, Cong HJ, Liu GZ, Ren YE. Effects of Continuous Epidural Injection of Dexamethasone on Blood Glucose, Blood Lipids, Plasma Cortisol and ACTH in Patients With Neuropathic Pain. Front Neurol. 2020;11:564643.

- Li W, Zhang X, Sang H, Zhou Y, Shang C, Wang Y, et al. Effects of hyperglycemia on the progression of tumor diseases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):327.

- Manchikanti L, Malla Y, Cash KA, Pampati V, Hirsch JA. Comparison of effectiveness for fluoroscopic cervical interlaminar epidural injections with or without steroid in cervical post-surgery syndrome. Korean J Pain. 2018;31(4):277-88.

- Neal JM, Barrington MJ, Brull R, Hadzic A, Hebl JR, Horlocker TT, et al. The Second ASRA Practice Advisory on Neurologic Complications Associated With Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine: Executive Summary 2015. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40(5):401-30.

- Shams D, Sachse K, Statzer N, Gupta RK. Regional Anesthesia Complications and Contraindications. Clin Sports Med. 2022;41(2):329-43.

- Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano D, Buvanendran A, De Andres J, Deer T, et al. Interventional Spine and Pain Procedures in Patients on Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications (Second Edition): Guidelines From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(3):225-62.

- Breivik H, Bang U, Jalonen J, Vigfusson G, Alahuhta S, Lagerkranser M. Nordic guidelines for neuraxial blocks in disturbed haemostasis from the Scandinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54(1):16-41.

- Weil IA, Seicean S, Neuhauser D, Schiltz NK, Seicean A. Use and Utility of Hemostatic Screening in Adults Undergoing Elective, Non-Cardiac Surgery. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0139139.

- Mooney JF, Ranasinghe I, Chow CK, Perkovic V, Barzi F, Zoungas S, et al. Preoperative estimates of glomerular filtration rate as predictors of outcome after surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(4):809-24.

- Lagerkranser, M. Neuraxial blocks and spinal haematoma: Review of 166 case reports published 1994-2015. Part 1: Demographics and risk-factors. Scand J Pain. 2017;15:118-29.

- Benzon HT, Maus TP, Kang HR, Provenzano DA, Bhatia A, Diehn F, et al. The Use of Contrast Agents in Interventional Pain Procedures: A Multispecialty and Multisociety Practice Advisory on Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis, Gadolinium Deposition in the Brain, Encephalopathy After Unintentional Intrathecal Gadolinium Injection, and Hypersensitivity Reactions. Anesth Analg. 2021;133(2):535-52.

- Chen TK, Knicely DH, Grams ME. Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Management: A Review. Jama. 2019;322(13):1294-304.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).