Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

| Plasmids/Strains | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pRK600 | pRK2013 npt::Tn9. Cmr | [38] |

| pRK415 | Broad host-range vector; Tcr | [39] |

| pRKenvZ | Plasmid pRK415 containing the envZ-like gene (locus tag CIT25_RS09080) from M. mediterraneum UPM-Ca36T; Tcr | This work |

| pMRGFP | Plasmid containing the gfp gene; Kmr | [40] |

| pMP4661 | Plasmid containing the rfp gene; Gmr | [41] |

| E. coli MT616 | Strain harboring the helper plasmid pRK600 | [38] |

| E. coli DH5α | Competent cells | NZYTech |

| Mesorhizobium sp. V-15b | isolated from chickpea root nodules (Portugal) | [32] |

| Mesorhizobium sp. ST-2 | isolated from chickpea root nodules (Portugal) | [32] |

| Mesorhizobium sp. PMI-6 | isolated from chickpea root nodules (Portugal) | [32] |

| Mesorhizobium sp. EE-7 | isolated from chickpea root nodules (Portugal) | [32] |

| M. mediterraneum UPM-Ca36T | isolated from chickpea root nodules (Spain) | [32] |

| V15benvZ+ | Mesorhizobium sp. V-15b harboring pRKenvZ | This work |

| ST2envZ+ | Mesorhizobium sp. ST-2 harboring pRKenvZ | This work |

| PMI6envZ+ | Mesorhizobium sp. PMI-6 harboring pRKenvZ | This work |

| PMI6envZ+gfp | Mesorhizobium sp. PMI-6 harboring pRKenvZ and pMRGFP | This work |

| EE7envZ+ | Mesorhizobium sp. EE-7 harboring pRKenvZ | This work |

| EE7envZ+gfp | Mesorhizobium sp. EE-7 harboring pRKenvZ and pMRGFP | This work |

| Ca36envZ+ | M. mediterraneum UPM-Ca36T harboring pRKenvZ | This work |

| V15bpRK | Mesorhizobium sp. V-15b harboring pRK415 | [42] |

| ST2pRK | Mesorhizobium sp. ST-2 harboring pRK415 | [42] |

| PMI6pRK | Mesorhizobium sp. PMI-6 harboring pRK415 | [42] |

| PMI6pRKgfp | Mesorhizobium sp. PMI-6 harboring pRK415 and pMRGFP | [42] |

| PMI6pRKrfp | Mesorhizobium sp. PMI-6 harboring pRK415 and pMP4661 | This work |

| EE7pRK | Mesorhizobium sp. EE-7 harboring pRK415 | This work |

| EE7pRKgfp | Mesorhizobium sp. EE-7 harboring pRK415 and pMRGFP | This work |

| EE7pRKrfp | Mesorhizobium sp. EE-7 harboring pRK415 and pMP4661 | This work |

| Ca36pRK | M. mediterraneum UPM-Ca36T harboring pRK415 | This work |

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Modifying Mesorhizobia Strains with an Extra EnvZ-Like Gene

2.4. Evaluation of the Symbiotic Performance

2.5. Bacterial Growth in Salt Stress Conditions

2.6. Motility Assay and Mucoid Phenotype

2.7. Evaluation of Nodulation Kinetics

2.8. Analysis of Rhizobia Infection Process

3. Results

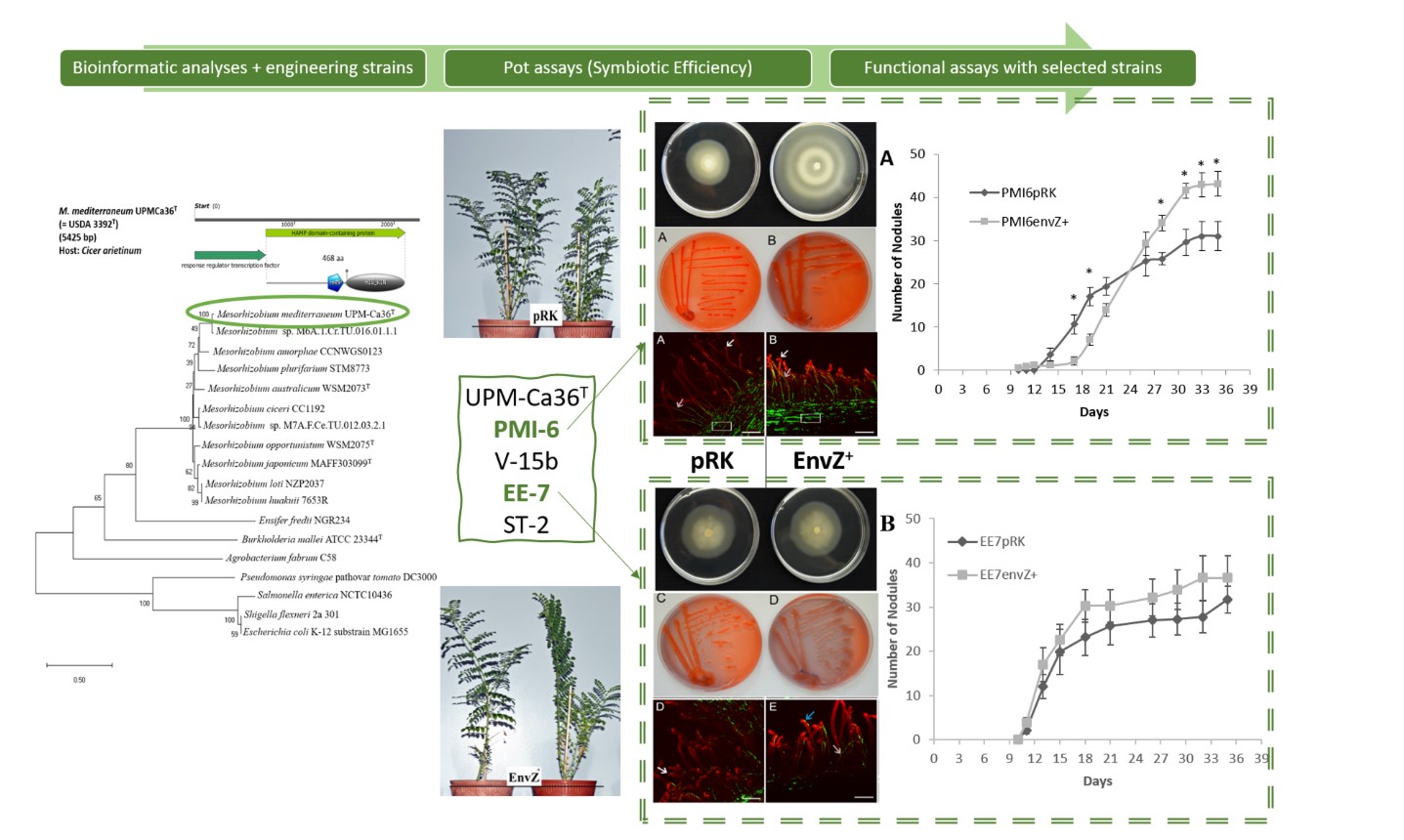

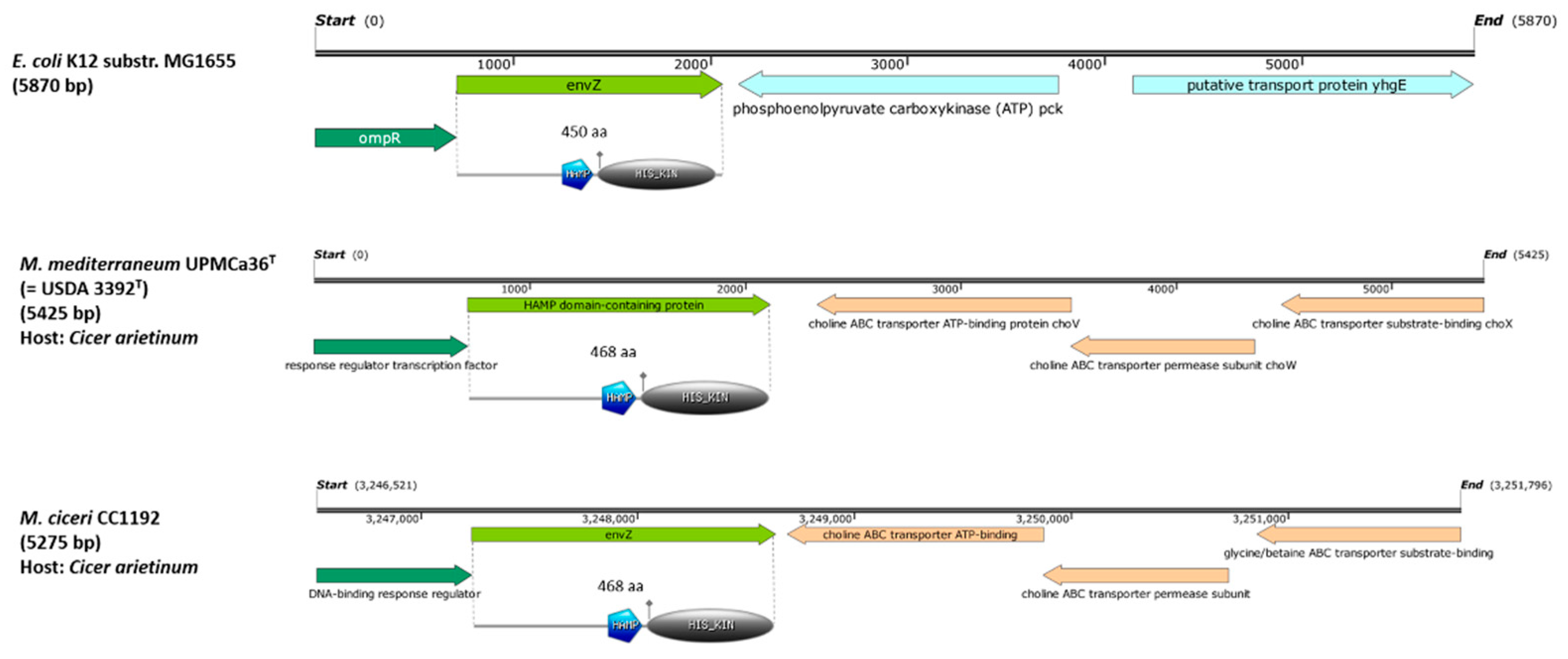

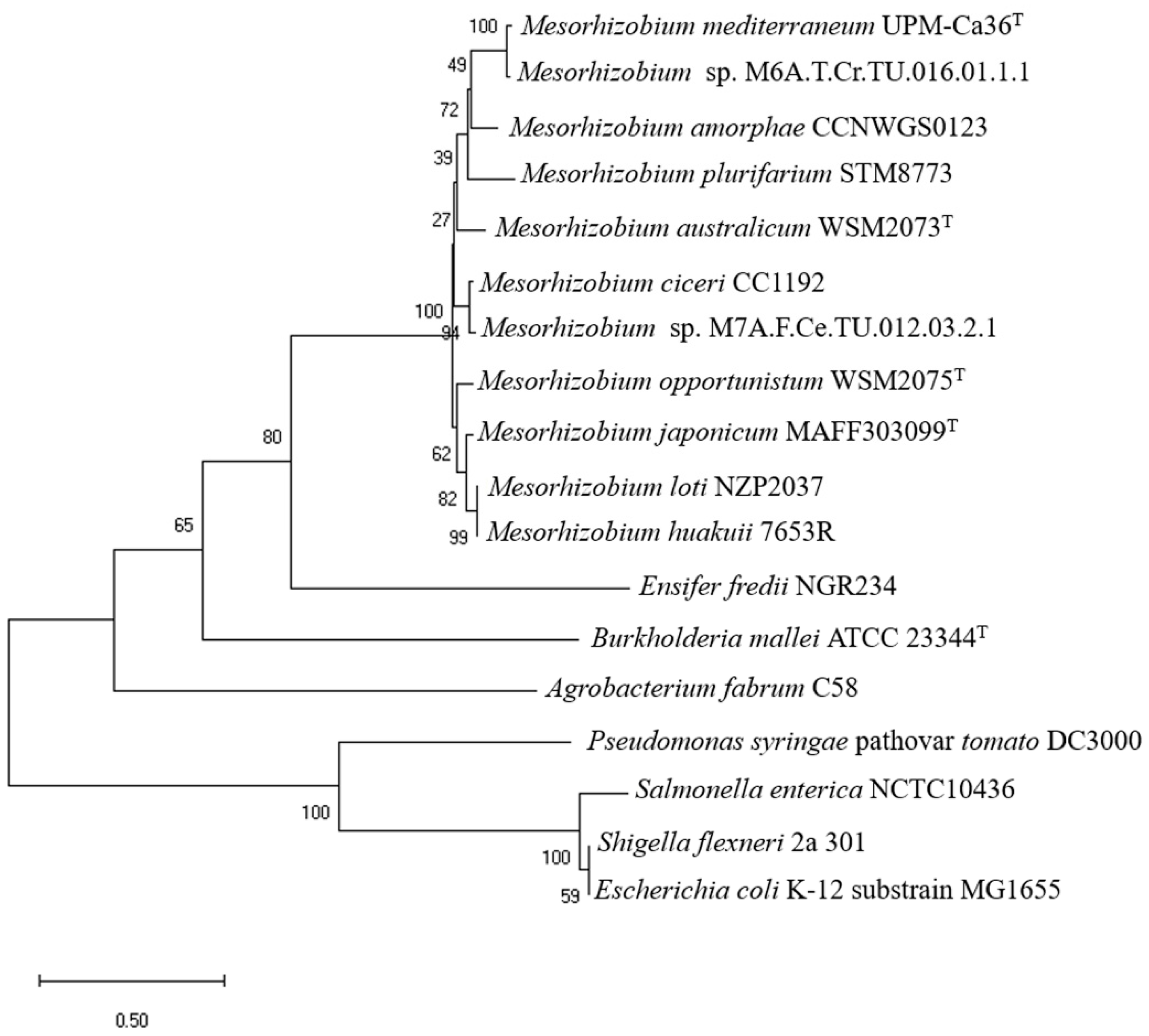

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis of EnvZ/envZ-Like Genes in the Genus Mesorhizobium

3.2. Evaluation of the Symbiotic Performance

| Strain | SDW (g) | RDW (g) | NN | AWN (mg) | SE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V15bpRK | 0.699 + 0.062 a | 0.335 + 0.039 a | 67 + 17 a | 1.567 + 0.246 a | 32.22 + 6.1 a |

| V15benvZ+ | 0.756 + 0.044 a | 0.432 + 0.027 a | 73 + 11 a | 1.332 + 0.123 a | 37.78 + 4.3 a |

| Ca36pRK | 0.789 + 0.085 a | 0.342 + 0.035 a | 57 + 7 a | 1.994+ 0.256 a | 41.07 + 8.4 a |

| Ca36envZ+ | 0.848 + 0.036 a | 0.296 + 0.021 a | 77 + 3 a | 1.333+ 0.054 a | 46.78 + 3.5 a |

| ST2pRK | 1.469 + 0.096 a | 0.478 + 0.033 b | 52 + 6 a | 2.546 + 0.314 b | 38.76 + 4.6 a |

| ST2envZ+ | 1.724 + 0.132 a | 0.603 + 0.023 a | 47 + 4 a | 3.754 + 0.257 a | 51.15 + 6.4 a |

| PMI6pRK | 1.325 + 0.113 b | 0.436 + 0.032 b | 66 + 13 a | 2.411 + 0.440 a | 31.78 + 5.5 b |

| PMI6envZ+ | 1.728 + 0.079 a | 0.527 + 0.020 a | 55 + 8 a | 3.405 + 0.734 a | 51.40 + 3.8 a |

| EE7pRK | 0.680 + 0.041 b | 0.319 + 0.011 b | 65 + 9 a | 1.099 + 0.440 b | 30.3 + 4.1 b |

| EE7envZ+ | 0.973 + 0.027 a | 0.556 + 0.034 a | 63 + 6 a | 1.707 + 0.734 a | 59.1 + 2.7 a |

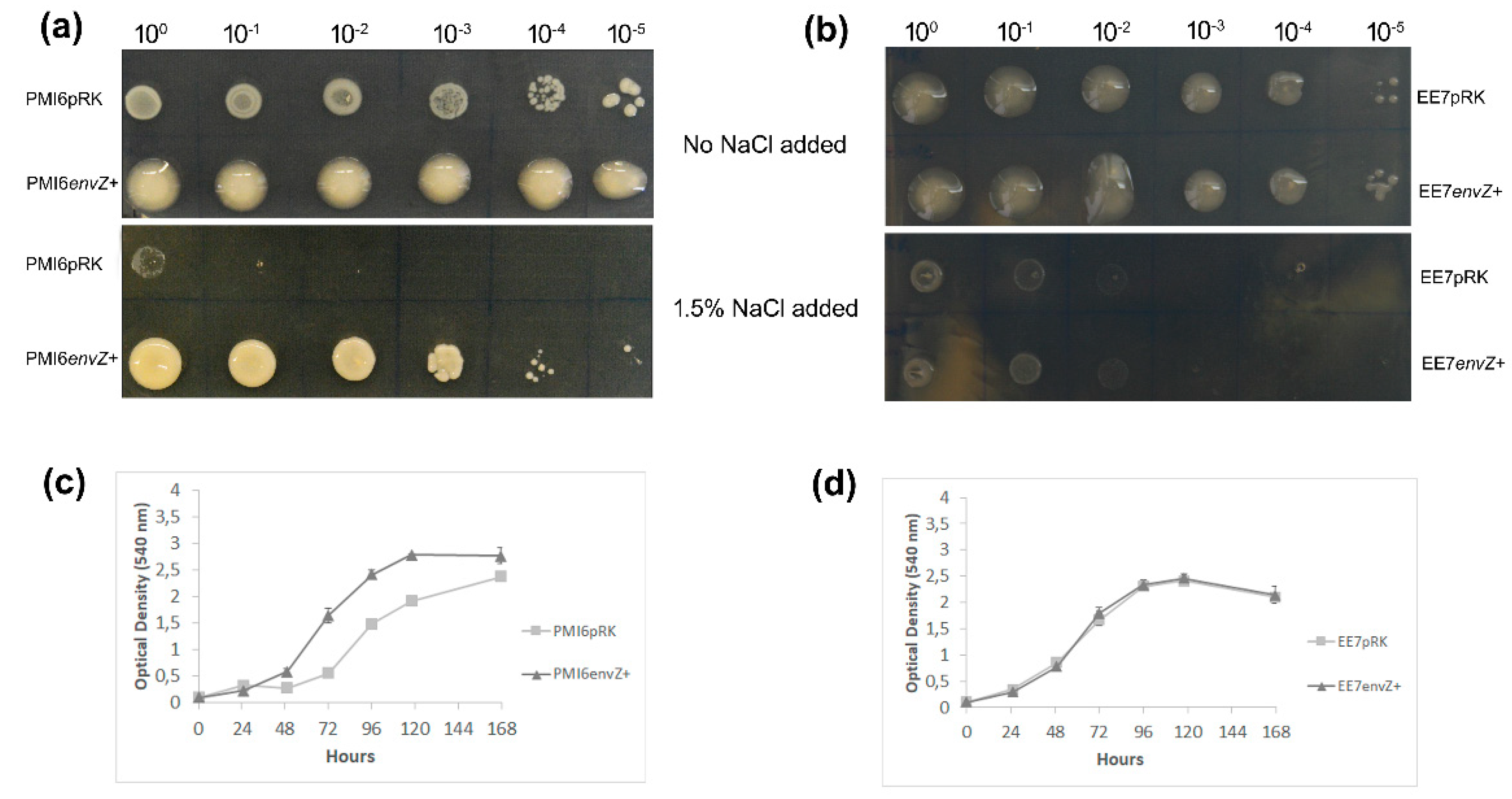

3.3. Bacterial Growth Under Salt Stress Conditions

3.4. Swimming

3.5. Exopolysaccharides Production

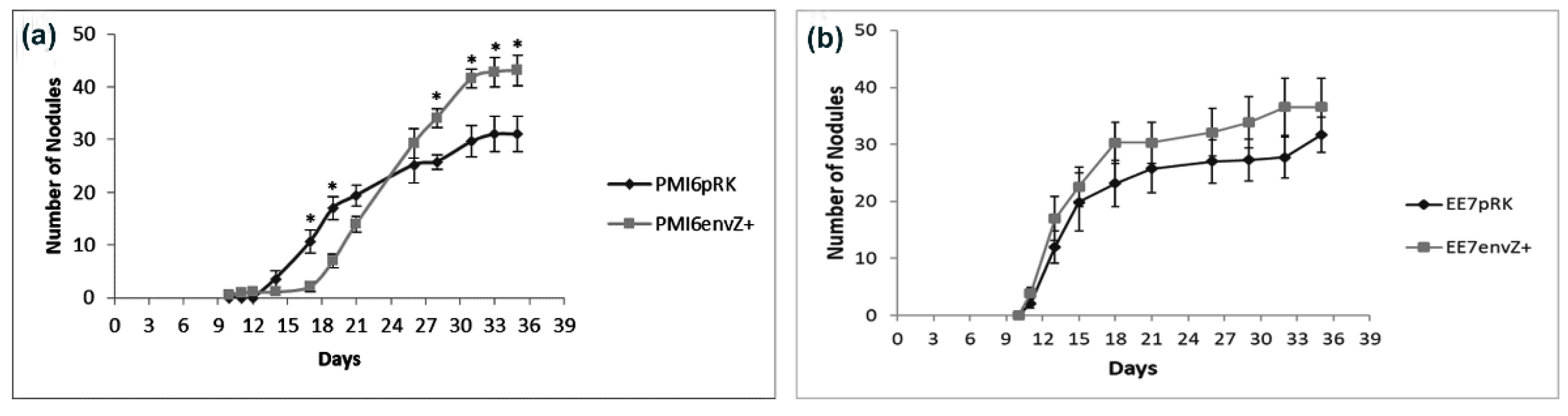

3.6. Nodule Formation

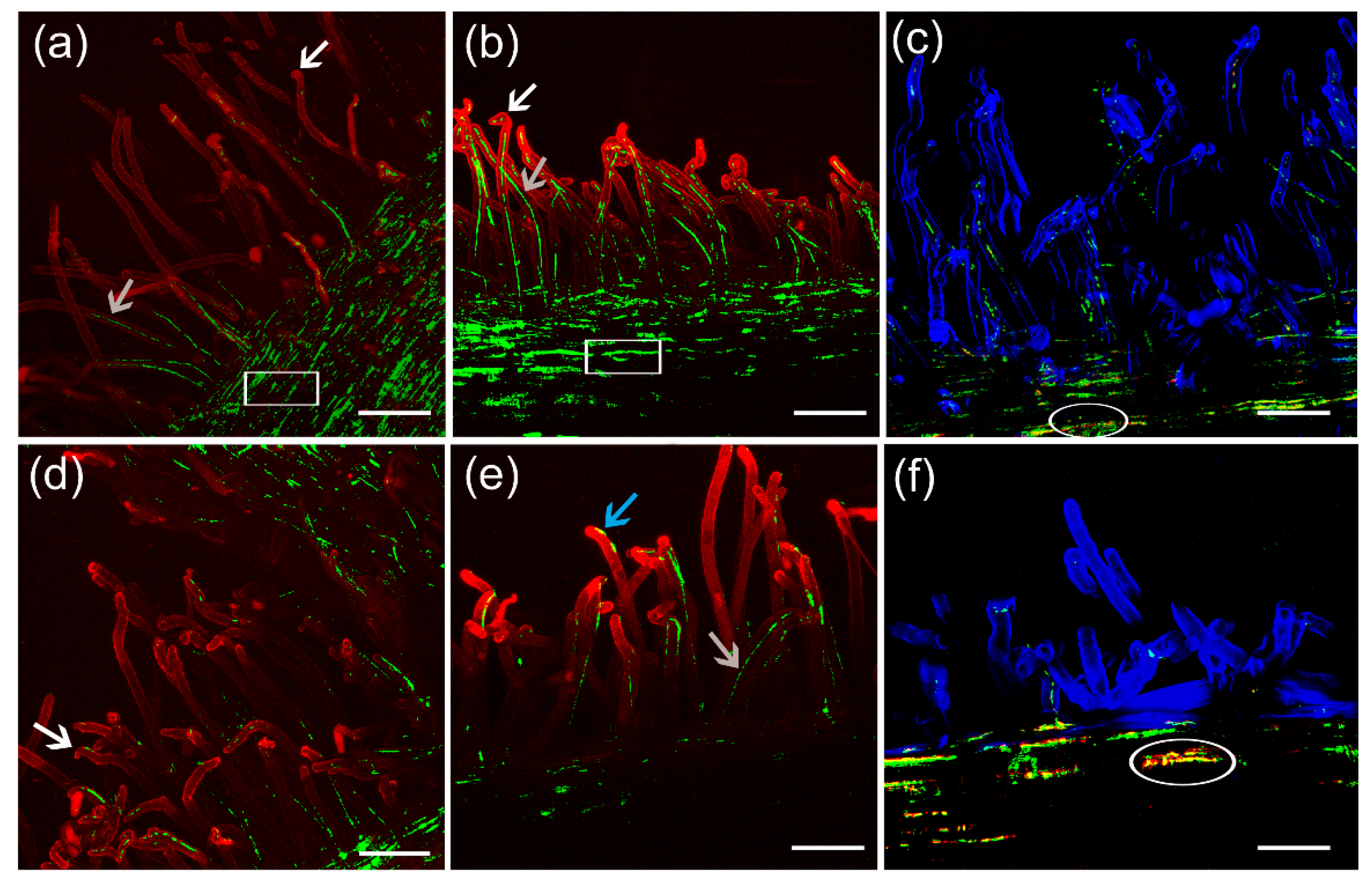

3.7. Colonization and Infection Thread Formation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tschauner, K.; Hörnschemeyer, P.; Müller, V.S.; Hunke, S. Dynamic interaction between the CpxA sensor kinase and the periplasmic accessory protein CpxP mediates signal recognition in E. Coli. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, M.; Epstein, B.; Badgley, B.D.; Unno, T.; Xu, L.; Reese, J.; Gyaneshwar, P.; Denny, R.; Mudge, J.; Bharti, A.K.; et al. Comparative genomics of the core and accessory genomes of 48 Sinorhizobium strains comprising five genospecies. Genome Biol 2013, 14, R17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.-T.; Tyler, B.M.; Setubal, J.C. Protein secretion systems in bacterial-host associations, and their description in the gene ontology. BMC Microbiol 2009, 9, S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boor, K.J. Bacterial Stress Responses: What doesn’t kill them can make Them stronger. PLoS Biol 2006, 4, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, Y.H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Kenney, L.J. Cytoplasmic sensing by the inner membrane histidine kinase EnvZ. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2015, 118, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.C.; Morgan, L.K.; Godakumbura, P.; Kenney, L.J.; Anand, G.S. The inner membrane histidine kinase EnvZ senses osmolality via helix-coil transitions in the cytoplasm: The mechanism of EnvZ osmosensing. The EMBO Journal 2012, 31, 2648–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqua, M.; Coluccia, M.; Eguchi, Y.; Okajima, T.; Grossi, M.; Prosseda, G.; Utsumi, R.; Colonna, B. Roles of two-component signal transduction systems in Shigella virulence. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Cai, S.J.; Inouye, M. Interaction of EnvZ, a sensory histidine kinase, with phosphorylated OmpR, the cognate response regulator. Molecular Microbiology 2002, 46, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wei, B.; Shi, M.; Gao, H. Functional assessment of EnvZ/OmpR two-component system in Shewanella oneidensis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattison, K.; Kenney, L.J. Phosphorylation alters the interaction of the response regulator OmpR with its sensor kinase EnvZ. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 11143–11148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, T.; Aiba, H.; Masuda, Y.; Kanaya, S.; Sugiura, M.; Wanner, B.L.; Mori, H.; Mizuno, T. Transcriptome analysis of all two-component regulatory system mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. Molecular Microbiology 2002, 46, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z.; Tan, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhou, D.; Yang, R. Phenotypic and transcriptional analysis of the osmotic regulator OmpR in Yersinia pestis. BMC Microbiol 2011, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerken, H.; Shetty, D.; Kern, B.; Kenney, L.J.; Misra, R. Effects of pleiotropic ompR and envZ alleles of Escherichia Coli on envelope stress and antibiotic sensitivity. J Bacteriol 2024, 206, e00172–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Oropeza, R.; Kenney, L.J. Dual regulation by phospho-OmpR of ssrA/B Gene Expression in Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 2. Molecular Microbiology 2003, 48, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Shi, A.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Hu, Y.; Lv, H.; Wu, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.-M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. EnvZ/OmpR Controls Protein expression and modifications in Cronobacter sakazakii for virulence and environmental resilience. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 18697–18707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ancona, V.; Zhao, Y. Co-regulation of polysaccharide production, motility, and expression of type III secretion Genes by EnvZ/OmpR and GrrS/GrrA systems in Erwinia amylovora. Mol Genet Genomics 2014, 289, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.D.; Ruschkowski, S.R.; Stein, M.A.; Finlay, B.B. Trafficking of porin-deficient Salmonella typhimurium mutants inside HeLa cells: ompR and envZ Mutants are defective for the formation of Salmonella -Induced Filaments. Infect Immun 1998, 66, 1806–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, D.; Li, J.; Roberts, M.; Maskell, D.; Hone, D.; Levine, M.; Dougan, G.; Chatfield, S. Characterization of defined ompR mutants of Salmonella typhi: ompR is involved in the regulation of Vi polysaccharide expression. Infect Immun 1994, 62, 3984–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Park, C. Modulation of flagellar expression in Escherichia coli by acetyl phosphate and the osmoregulator OmpR. J Bacteriol 1995, 177, 4696–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, A.V.; Verkhusha, V.V. Engineering signalling pathways in mammalian cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2024, 8, 1523–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Walthers, D.; Oropeza, R.; Kenney, L.J. The response regulator SsrB activates transcription and binds to a region overlapping OmpR binding sites at Salmonella Pathogenicity island 2. Molecular Microbiology 2004, 54, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieckarz, M.; Jaworska, K.; Raczkowska, A.; Brzostek, K. The regulatory circuit underlying downregulation of a type III secretion system in Yersinia enterocolitica by transcription factor OmpR. IJMS 2022, 23, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson-Boivin, C.; Sachs, J.L. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation by Rhizobia — the roots of a success story. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2018, 44, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, S.K.; Rajput, V.D.; Kumari, A.; Espinosa-Saiz, D.; Menendez, E.; Minkina, T.; Dwivedi, P.; Mandzhieva, S. Plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria: A potential bio-asset for restoration of degraded soil and crop productivity with sustainable emerging techniques. Environ geochem Health 2023, 45, 9321–9344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, B.; Kearsley, J.; Morton, R.; DiCenzo, C.; Finan, T. The genomes of Rhizobia. In Advances in Botanical Research; Frendo, P., Frugier, F., Masson-Boivin, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Canada, 2020; Volume 94, pp. 1–348. [Google Scholar]

- da-Silva, J.R.; Alexandre, A.; Brígido, C.; Oliveira, S. Can stress response genes be used to improve the symbiotic Performance of Rhizobia? AIMS Microbiology 2017, 3, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, A.; da-Silva, J.R.; Eliziário, F.; Brígido, C.; Oliveira, S.; Alexandre, A. traG Gene Is Conserved across Mesorhizobium Spp. able to nodulate the same host plant and expressed in response to root exudates. BioMed Research International 2019, 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-P.; Walker, G.C. Succinoglycan production by Rhizobium Meliloti is regulated through the ExoS-ChvI two-component regulatory system. J Bacteriol 1998, 180, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.; Daveran, M.-L.; Batut, J.; Dedieu, A.; Domergue, O.; Ghai, J.; Hertig, C.; Boistard, P.; Kahn, D. Cascade regulation of nif gene expression in Rhizobium meliloti. Cell 1988, 54, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronson, C.W.; Astwood, P.M.; Nixon, T.B.; Ausubel, F.M. Deduced products of c4-dicarboxylate transport regulatory genes of Rhizobium leguminosarum are homologous to nitrogen regulatory gene products. Nucl Acids Res 1987, 15, 7921–7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Jurado, S.; Fuentes-Romero, F.; Ruiz-Sainz, J.-E.; Janczarek, M.; Vinardell, J.-M. Rhizobial Exopolysaccharides: Genetic Regulation of Their Synthesis and Relevance in Symbiosis with Legumes. IJMS 2021, 22, 6233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, A.; Brígido, C.; Laranjo, M.; Rodrigues, S.; Oliveira, S. Survey of chickpea Rhizobia diversity in Portugal reveals the predominance of species distinct from Mesorhizobium ciceri and Mesorhizobium Mediterraneum. Microb Ecol 2009, 58, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brígido, C.; Alexandre, A.; Oliveira, S. Transcriptional analysis of major chaperone Genes in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive Mesorhizobia. Microbiological Research 2012, 167, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjo, M.; Alexandre, A.; Rivas, R.; Velázquez, E.; Young, J.P.W.; Oliveira, S. Chickpea rhizobia symbiosis genes are highly conserved across multiple Mesorhizobium species: Mesorhizobia symbiosis genes are conserved. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2008, 66, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour, S.M.; Cleyet-Marel, J.-C.; Normand, P.; Fernandez, M.P. Genomic heterogeneity of strains nodulating Chickpeas (Cicer Arietinum L.) and description of Rhizobium mediterraneum Sp. Nov. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 1995, 45, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasegaran, P.; Hoben, H. Handbook for Rhizobia; Springer-Verlag: New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Finan, T.M.; Kunkel, B.; De Vos, G.F.; Signer, E.R. Second symbiotic megaplasmid in Rhizobium meliloti carrying exopolysaccharide and thiamine synthesis genes. J Bacteriol 1986, 167, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, N.T.; Tamaki, S.; Kobayashi, D.; Trollinger, D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 1988, 70, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fraile, P.; Carro, L.; Robledo, M.; Ramírez-Bahena, M.-H.; Flores-Félix, J.-D.; Fernández, M.T.; Mateos, P.F.; Rivas, R.; Igual, J.M.; Martínez-Molina, E.; et al. Rhizobium promotes non-legumes growth and quality in several production steps: towards a biofertilization of edible raw vegetables healthy for humans. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemberg, G.V.; Wijfjes, A.H.M.; Lamers, G.E.M.; Stuurman, N.; Lugtenberg, B.J.J. Simultaneous imaging of Pseudomonas Fluorescens WCS365 populations expressing three different autofluorescent proteins in the rhizosphere: New Perspectives for Studying Microbial Communities. MPMI 2000, 13, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da-Silva, J.R.; Menéndez, E.; Eliziário, F.; Mateos, P.F.; Alexandre, A.; Oliveira, S. Heterologous expression of nifA or nodD genes improves chickpea-Mesorhizobium symbiotic performance. Plant Soil 2019, 436, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, E.; Sigrist, C.J.A.; Gattiker, A.; Bulliard, V.; Langendijk-Genevaux, P.S.; Gasteiger, E.; Bairoch, A.; Hulo, N. ScanProsite: Detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-Associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Research 2006, 34, W362–W365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 1998, 14, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas, R.; Velázquez, E.; Valverde, A.; Mateos, P.F.; Martínez-Molina, E. A two primers random amplified polymorphic DNA procedure to obtain polymerase chain reaction fingerprints of bacterial species. Electrophoresis 2001, 22, 1086–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, A.; Brígido, C.; Laranjo, M.; Rodrigues, S.; Oliveira, S. Survey of chickpea Rhizobia diversity in Portugal reveals the predominance of species distinct from Mesorhizobium ciceri and Mesorhizobium mediterraneum. Microb Ecol 2009, 58, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, W.J.; Dilworth, M.J. Control of leghaemoglobin synthesis in snake beans. Biochemical Journal 1971, 125, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brígido, C.; Nascimento, F.X.; Duan, J.; Glick, B.R.; Oliveira, S. Expression of an exogenous 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate deaminase gene in Mesorhizobium Spp. reduces the negative effects of salt Stress in chickpea. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, A. evaluation of nitrogen fixation by legumes in the greenhouse and growth chamber. In Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation Technology; Elkan, G., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New Yor, 1987; pp. 321–363. [Google Scholar]

- Rouws, L.F.M.; Simões-Araújo, J.L.; Hemerly, A.S.; Baldani, J.I. Validation of a Tn5 transposon mutagenesis system for Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus through characterization of a flagellar mutant. Arch Microbiol 2008, 189, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, M.; Rivera, L.; Jiménez-Zurdo, J.I.; Rivas, R.; Dazzo, F.; Velázquez, E.; Martínez-Molina, E.; Hirsch, A.M.; Mateos, P.F. Role of Rhizobium endoglucanase CelC2 in cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm formation on plant roots and abiotic surfaces. Microb Cell Fact 2012, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brígido, C.; Robledo, M.; Menéndez, E.; Mateos, P.F.; Oliveira, S. A ClpB chaperone knockout mutant of Mesorhizobium Ciceri shows a delay in the root nodulation of chickpea plants. MPMI 2012, 25, 1594–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Félix, J.; Menéndez, E.; Marcos-García, M.; Celador-Lera, L.; Rivas, R. Calcofluor white, an alternative to propidium iodide for plant tissues staining in studies of root colonization by fluorescent-tagged Rhizobia. JABB 2015, 2, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anolles, G.; Wall, L.; De Micheli, A.; Macchi, E.; Baur, W.; Favelukes, G. Role of motility and chemotaxis in efficiency of nodulation by Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol 1988, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay-Fraret, J.; Ardissone, S.; Kambara, K.; Broughton, W.J.; Deakin, W.J.; Quéré, A. Cyclic-β-glucans of Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) sp. strain NGR234 are required for hypo-osmotic adaptation, motility, and efficient symbiosis with host plants. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2012, 333, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphen, W.V.; Lugtenberg, B. Influence of osmolarity of the growth medium on the outer membrane protein Pattern of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 1977, 131, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bontemps-Gallo, S.; Madec, E.; Robbe-Masselot, C.; Souche, E.; Dondeyne, J.; Lacroix, J.-M. The opgC gene is required for OPGs succinylation and is osmoregulated through RcsCDB and EnvZ/OmpR in the phytopathogen Dickeya dadantii. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravind, L.; Ponting, C.P. The cytoplasmic helical linker domain of receptor histidine kinase and methyl-accepting proteins is common to many prokaryotic signalling proteins. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1999, 176, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, A.H.; Stock, A.M. Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2001, 26, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncompagni, E.; Østerås, M.; Poggi, M.-C.; Le Rudulier, D. Occurrence of choline and glycine betaine uptake and metabolism in the family Rhizobiaceae and their roles in osmoprotection. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999, 65, 2072–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.M.; Kobayashi, H.; Davies, B.W.; Taga, M.E.; Walker, G.C. How Rhizobial symbionts invade plants: the Sinorhizobium–medicago model. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007, 5, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S. Interaction of Nod and Exo Rhizobium Meliloti in Alfalfa Nodulation. MPMI 1988, 1, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.M. Increased production of the exopolysaccharide succinoglycan enhances Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 symbiosis with the host plant Medicago truncatula. J Bacteriol 2012, 194, 4322–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.M.; Sharopova, N.; Lohar, D.P.; Zhang, J.Q.; VandenBosch, K.A.; Walker, G.C. Differential response of the plant Medicago truncatula to its symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti or an exopolysaccharide-deficient mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.K.; Maiti, T.K. Structure of Extracellular Polysaccharides (EPS) produced by rhizobia and their functions in legume–bacteria symbiosis: — a review. Achievements in the Life Sciences 2016, 10, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehelin, C.; Forsberg, L.S.; D’Haeze, W.; Gao, M.-Y.; Carlson, R.W.; Xie, Z.-P.; Pellock, B.J.; Jones, K.M.; Walker, G.C.; Streit, W.R.; et al. Exo-oligosaccharides of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 are required for symbiosis with various legumes. J Bacteriol 2006, 188, 6168–6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janczarek, M.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J.; Skorupska, A. Multiple copies of rosR and pssA genes enhance exopolysaccharide production, symbiotic competitiveness and clover nodulation in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. Trifolii. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2009, 96, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forst, S.; Tabatabai, N. Role of the histidine kinase, envz, in the production of outer membrane proteins in the symbiotic-pathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Boylan, B.; George, N.; Forst, S. Inactivation of ompR promotes precocious swarming and flhDC expression in Xenorhabdus Nematophila. J Bacteriol 2003, 185, 5290–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüß, B.M. Involvement of two-component signaling on bacterial motility and biofilm development. J Bacteriol 2017, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, K.A.; Rather, P.N. An ompR-envZ Two-component system ortholog regulates phase variation, osmotic tolerance, motility, and virulence in Acinetobacter baumannii strain AB5075. J Bacteriol 2017, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soby, S.; Bergman, K. Motility and chemotaxis of Rhizobium Meliloti in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 1983, 46, 995–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Mao, Y.; Teng, J.; Zhu, Q.; Ling, J.; Zhong, Z. Flagellar-dependent motility in Mesorhizobium tianshanense is involved in the early stage of plant host interaction: Study of an flgE Mutant. Curr Microbiol 2015, 70, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, H.Y.; Glenn, A.R.; Arwas, R.; Dilworth, M.J. Symbiotic and competitive properties of motility mutants of Rhizobium trifolii TA1. Arch. Microbiol. 1987, 148, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubber, A.M.; Sullivan, J.T.; Ronson, C.W. Symbiosis-induced cascade regulation of the Mesorhizobium loti R7A VirB/D4 type IV Ssecretion system. MPMI 2007, 20, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, S.; Kaneko, T.; Sato, S.; Saeki, K. Hijacking of leguminous nodulation signaling by the Rhizobial type III secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 17131–17136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélanger, L.; Dimmick, K.A.; Fleming, J.S.; Charles, T.C. Null mutations in Sinorhizobium meliloti exoS and chvI demonstrate the importance of this two-component regulatory system for symbiosis. Molecular Microbiology 2009, 74, 1223–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.J.; Fisher, R.F.; Perovich, V.M.; Sabio, E.A.; Long, S.R. Identification of direct transcriptional target genes of ExoS/ChvI two-component signaling in Sinorhizobium Meliloti. J Bacteriol 2009, 191, 6833–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.J.; Sanjuán, J.; Olivares, J. Rhizobia and plant-pathogenic bacteria: common infection weapons. Microbiology 2006, 152, 3167–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlon, A.; Chang, P.L.; Damtew, Z.M.; Muleta, A.; Carrasquilla-Garcia, N.; Kim, D.; Nguyen, H.P.; Suryawanshi, V.; Krieg, C.P.; Yadav, S.K.; et al. Global-level population genomics reveals differential effects of geography and phylogeny on horizontal gene transfer in soil bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 15200–15209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, F.; Diouf, D.; Klonowska, A.; Le Queré, A.; Bakhoum, N.; Fall, D.; Neyra, M.; Parrinello, H.; Diouf, M.; Ndoye, I.; et al. Genetic and genomic diversity studies of Acacia symbionts in Senegal reveal new species of Mesorhizobium with a putative geographical pattern. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasena, K.; Yates, R.; Tiwari, R.; O’Hara, G.; Howieson, J.; Ninawi, M.; Chertkov, O.; Detter, C.; Tapia, R.; Han, S.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Mesorhizobium ciceri Bv. Biserrulae type strain (WSM1271T). Stand. Genomic Sci. 2013, 9, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hao, B.; Li, J.; Gu, H.; Peng, J.; Xie, F.; Zhao, X.; Frech, C.; Chen, N.; Ma, B.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing of Mesorhizobium huakuii 7653R provides molecular insights into host specificity and symbiosis island dynamics. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.; Sullivan, J.; Ronson, C.; Tian, R.; Bräu, L.; Davenport, K.; Daligault, H.; Erkkila, T.; Goodwin, L.; Gu, W.; et al. Genome sequence of the Lotus Spp. microsymbiont Mesorhizobium loti strain NZP2037. Stand in Genomic Sci 2014, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Wei, S.; Zhao, L. Complete genome sequence of the Robinia pseudoacacia L. symbiont Mesorhizobium amorphae CCNWGS0123. Stand in Genomic Sci 2018, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskett, T.; Wang, P.; Ramsay, J.; O’Hara, G.; Reeve, W.; Howieson, J.; Terpolilli, J. Complete genome sequence of Mesorhizobium ciceri strain CC1192, an efficient nitrogen-fixing microsymbiont of Cicer Arietinum. Genome Announc 2016, 4, e00516–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenlon, A.; Chang, P.L.; Damtew, Z.M.; Muleta, A.; Carrasquilla-Garcia, N.; Kim, D.; Nguyen, H.P.; Suryawanshi, V.; Krieg, C.P.; Yadav, S.K.; et al. Global-level population genomics reveals differential effects of geography and phylogeny on horizontal gene transfer in soil bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 15200–15209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeisser, C.; Liesegang, H.; Krysciak, D.; Bakkou, N.; Le Quéré, A.; Wollherr, A.; Heinemeyer, I.; Morgenstern, B.; Pommerening-Röser, A.; Flores, M.; et al. Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 possesses a remarkable number of secretion systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009, 75, 4035–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.W.; Setubal, J.C.; Kaul, R.; Monks, D.E.; Kitajima, J.P.; Okura, V.K.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, L.; Wood, G.E.; Almeida, N.F.; et al. The genome of the natural genetic engineer Agrobacterium Tumefaciens C58. Science 2001, 294, 2317–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buell, C.R.; Joardar, V.; Lindeberg, M.; Selengut, J.; Paulsen, I.T.; Gwinn, M.L.; Dodson, R.J.; Deboy, R.T.; Durkin, A.S.; Kolonay, J.F.; et al. The complete genome sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas Syringae Pv. Tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100, 10181–10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Morooka, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Fujita, K.; Isono, K.; Choi, S.; Ohtsubo, E.; Baba, T.; Wanner, B.L.; Mori, H.; et al. Highly accurate genome sequences of Escherichia Coli K-12 Strains MG1655 and W3110. Molecular Systems Biology 2006, 2, 2006.0007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q. Genome Sequence of Shigella flexneri 2a: Insights into pathogenicity through comparison with genomes of Escherichia coli K12 and O157. Nucleic Acids Research 2002, 30, 4432–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).