1. Introduction

Nowadays, trauma of maxillofacial complex following different events is one of the most frequent clinical conditions observed in the Emergency Departments (ED), often requiring a treatment, conservative or surgical, which can be complex and invasive, depending on trauma and patients’ characteristics. Maxillofacial fractures often have an impact on people’s quality of life, causing long time to recover fully or mostly (up to 90 days or more) [1], since they can have implications on daily life activities when involving maxillary bones, such as eating and speaking, and they can affect facial aesthetics. A preliminary study by Hull et al. [2] has highlighted how psychological morbidities commonly follow maxillofacial injuries, showing that up 41% of patients had appreciable specific post-traumatic symptoms, such as anxiety and hyperarousal. This should be considered when facing some fragile categories of patients.

A systematic study on the burden of facial fractures across the world, made in 2020 by Lalloo et al. [3], analyses different parameters to quantify health loss, such as incidence and prevalence of facial fractures around the world, their causes and the years lived with disability (YLD) after facial traumas. The results show two peaks of incidence of facial traumas, one around 5 to 20 and the other one in the 70+ age.

Mandible is the most frequent bone injured in maxillofacial district [6] following a trauma, and most of its fractures are due to road traffic accidents (RTA); other frequent causes are interpersonal violence and falls, and the epidemiology changes from one country to another.

Among the most frequent active treatments of mandible’s fractures are closed reduction, intermaxillary fixation (IMF), open reduction internal fixation (ORIF), external fixation, and each of them finds its own indications.

ORIF is generally indicated for the most symphyseal and parasymphyseal fractures, displaced body and angle fractures, and certain condylar fractures: it usually involves an open reduction phase, obtained manually or through IMF, and a rigid fixation phase, based on the use of leg screws, tension band plates (Champy technique), reabsorbable or non-reabsorbable locking and no locking plates and screws [7].

Fracture fixation can be divided into either load bearing or load sharing [8]: the “bearing” concept refers to the force needed to oppose to the tensional forces involved in mandible fractures carried out by masticatory muscles.. When a load bearing fixation is carried out, the plate and screws applied fully respond and withstand these tractional forces and “bear” all the functional load, while a load sharing fixation relies also on the underlying bone.

Choosing which type of approach is indicated depends on many factors: a load bearing fixation is generally indicated in presence of multiply comminuted fratures, fractures with loss of substance and/or bony fragments and in structurally compromised bones, such as the edentulous mandibles.

Fractures of the edentulous mandible, yet infrequent, are still a surgical concern nowadays for several factors: reduced bone volume, poor blood supply, absence of teeth intermaxillary fixation or as an occlusion guide and lack of anatomic landmarks, shallowness of inferior alveolar nerve ( with subsequent higher risk of damage), general higher age of patients to be treated.

It is known that in the atrophic mandible blood supply is generally centripetal coming from the periosteum and surrounding soft tissues, rather than from the cancellous bone: this implicates the need of minimal periosteal disruption in the reduction and fixation manoeuvres and determines the importance of rigid fixation, without any micro-mobility between the bony fragments.

Two classifications are commonly used to assess atrophy of the mandible: Cawood and Howell [9] first proposed the classification of edentulous mandibles according to the height of the residual ridge following resorption of alveolar bone, describing 6 classes.

According to Luhr’s classification [10], specific for degree of atrophy in fractures of the atrophic edentulous mandible, atrophy can be divided into Class I (height at the fracture site 16 to 20 mm), Class II (height 11 to 15 mm) and Class III (height ≤10 mm).

The higher the class or grade of atrophy we encounter, the more rigid and stable the fixation should be, to prevent mobility of bony fragments, malunion, infection, pseudoarthrosis, breaking of the plate(s).

To minimize complications following fractures and their surgical treatment, basic principles should be followed in order to obtain a stable, rigid and biocompatible fixation: in this landscape, modern technologies such as CAD-CAM technique aim to develop and provide more specific and predictable solutions for these kind of patients, especially with patient-specific implants.The aim of this case report is to enlight the potential of CAD-CAM technique for a complex secondary reconstruction of a severely atrophic mandible after the failure of a less invasive surgical procedure using a single reconstructive patient-specific plate.

2. Materials and Methods

A 75-year-old female patient presented at our Maxillofacial Surgery Unit for the evaluation the clinical outcomes of a multifocal fracture of the mandible.

More specifically, she was involved in a car crash in March 2023, reporting polytrauma with both a mandibular and a tibial fracture. The preoperative CT scan showed a severely atrophic edentulous mandible (Luhr’s Class III [10], height of the bone at the lowest point of 4.14 mm) affected by a displaced bifocal fracture of the mandibular body both on the right and left side, causing the detachment of the symphyseal area, without comminution or exposed areas. The detachment of symphyseal fragment caused a clockwise rotational movement and its pulling downward caused by the action of digastric muscles, producing a yaw rotation of mandibular rami in a medial direction.

The patient was admitted in another Maxillofacial Unit the day of the trauma and underwent a surgical intervention consisting in an ORIF (Open Reduction Internal Fixation) with reduction of the fractures, repositioning of the edentulous bony fragments of the mandible and fixation through 2 titanium miniplates and monocortical screws (2.0 mandibular system).

The patient was transferred 20 days after surgery in a rehabilitation center where she started physiotherapy for the tibial fracture; during this hospitalization, she started complaining pain in the left side of the mandible and mobility of the bony fragments.

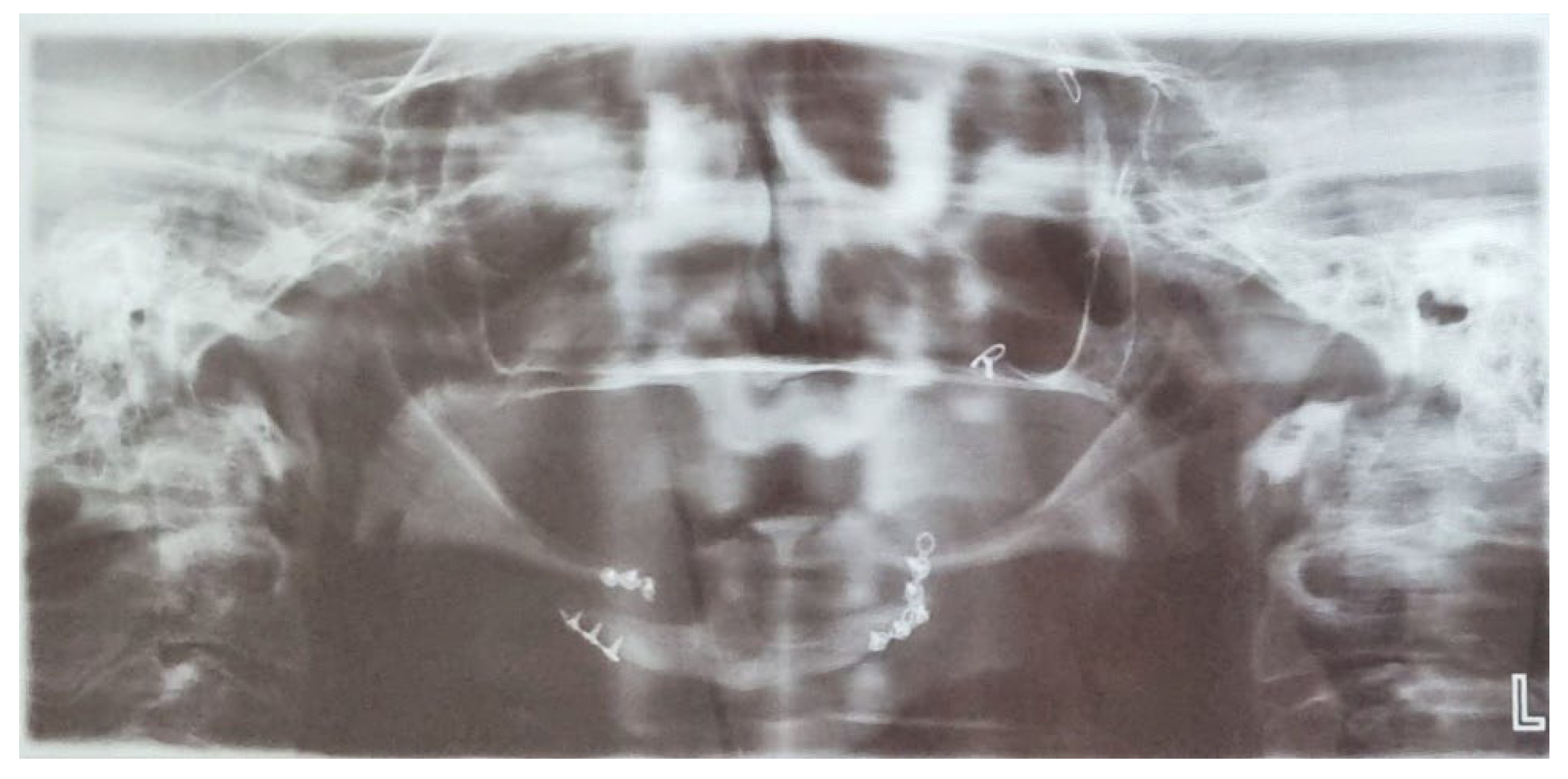

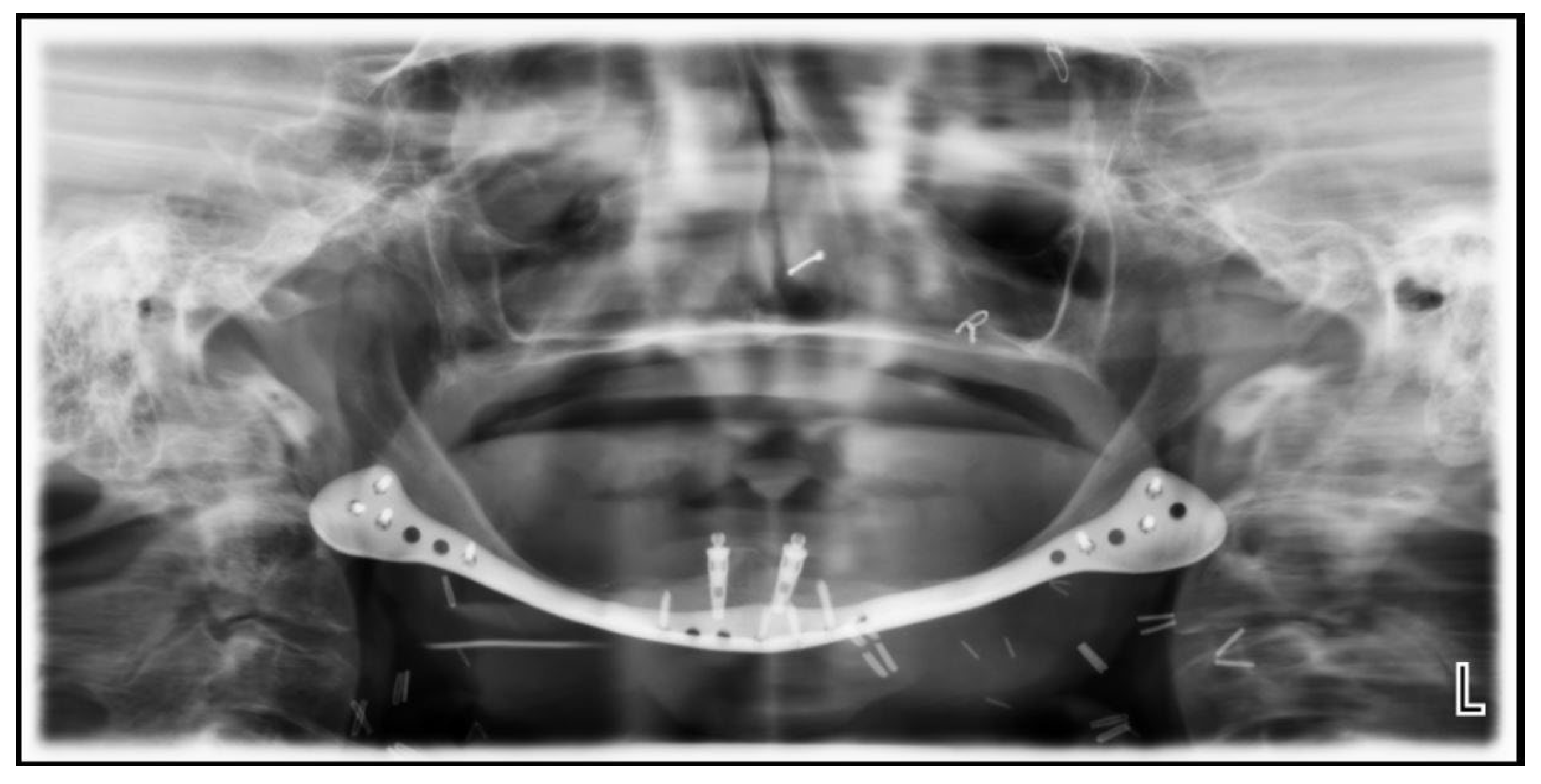

She then underwent a control OPT (

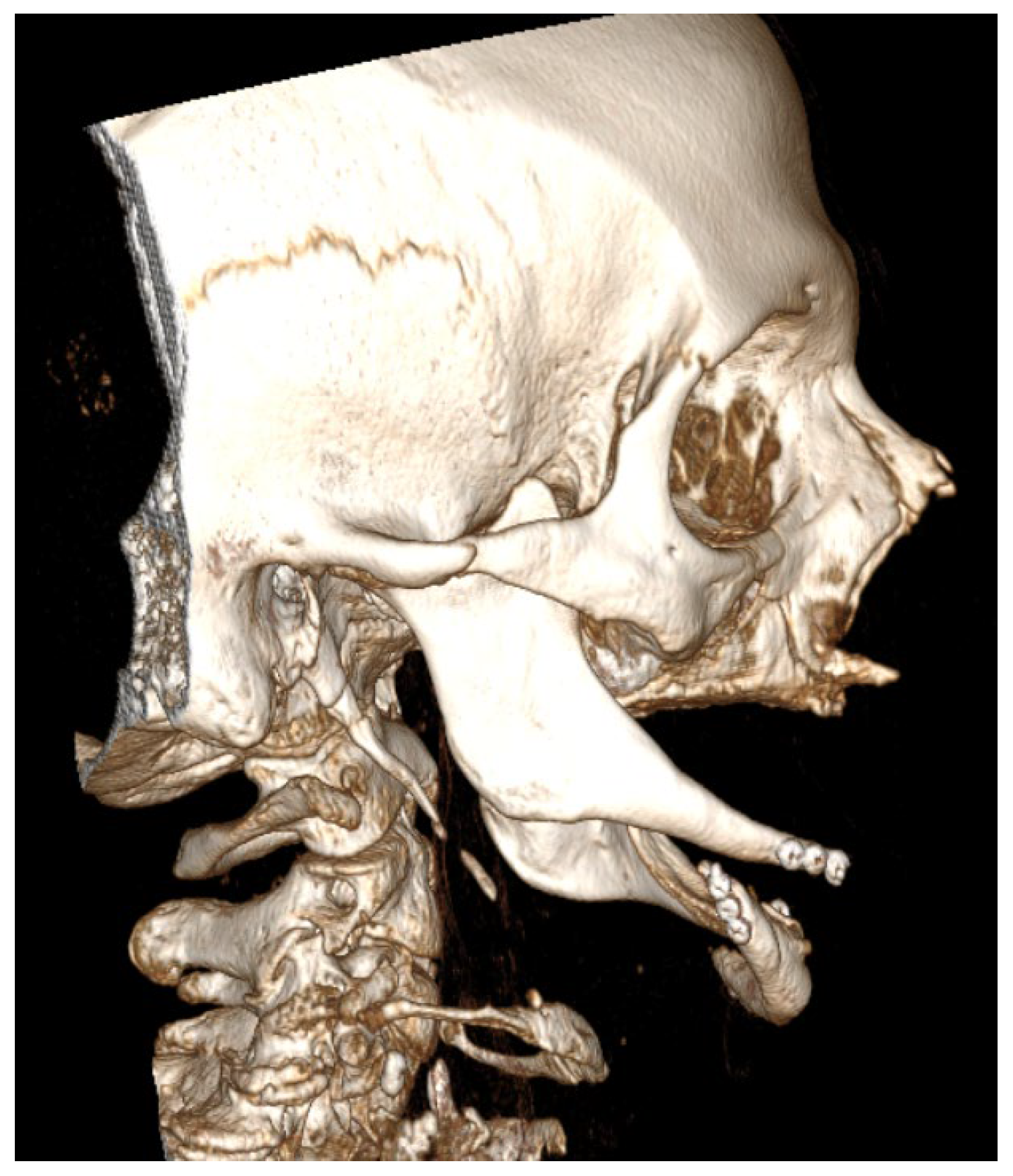

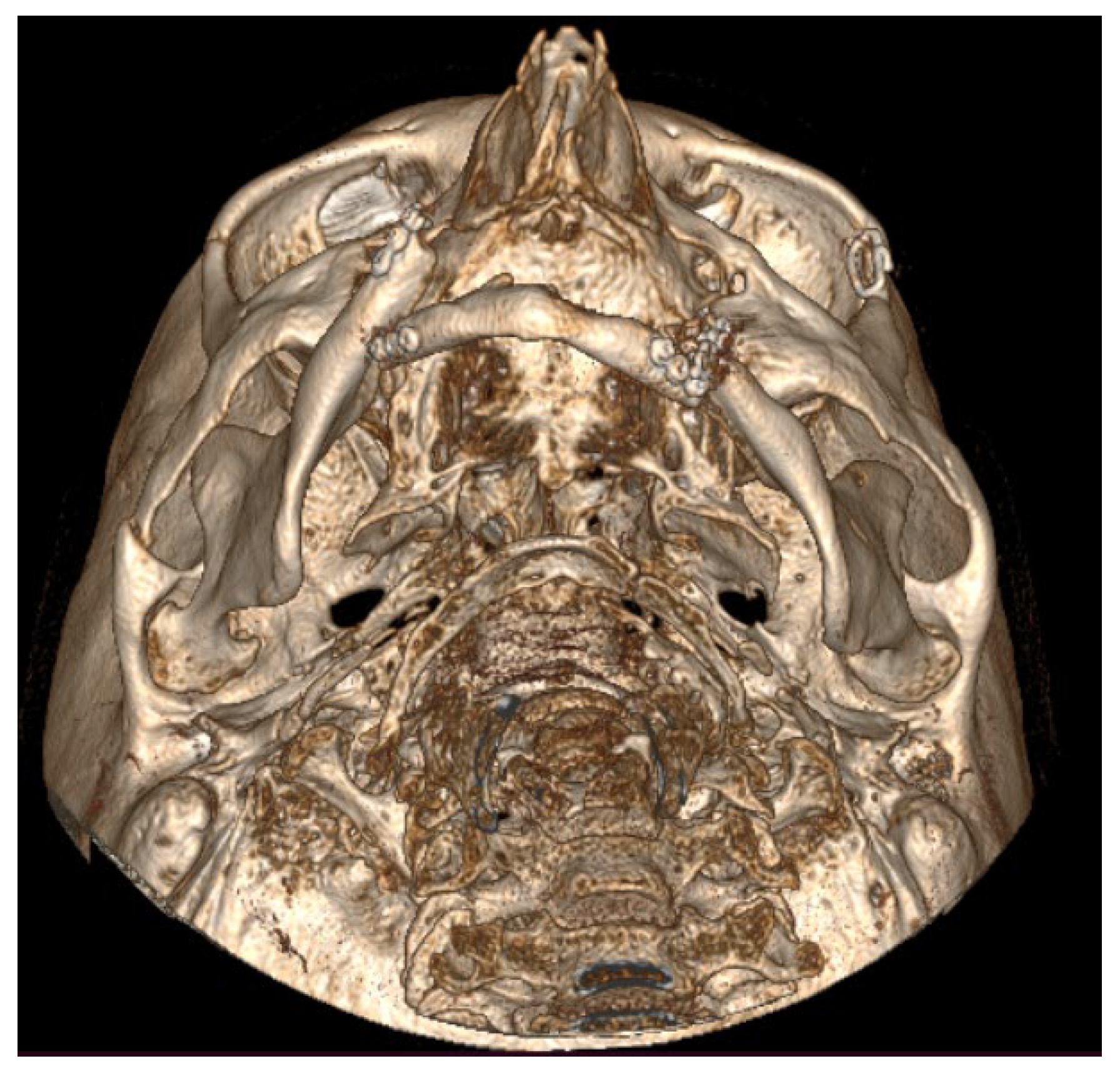

Figure 1) and CT scan (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), that showed fracture of the titanium plates and the consequent dislocation of mandibular fragments, leading to non-union and fibrous healing without formation of the bone callus.

She finally referred to our Maxillofacial Unit asking for the possibility to make a secondary reduction of the fractures and reconstruction.

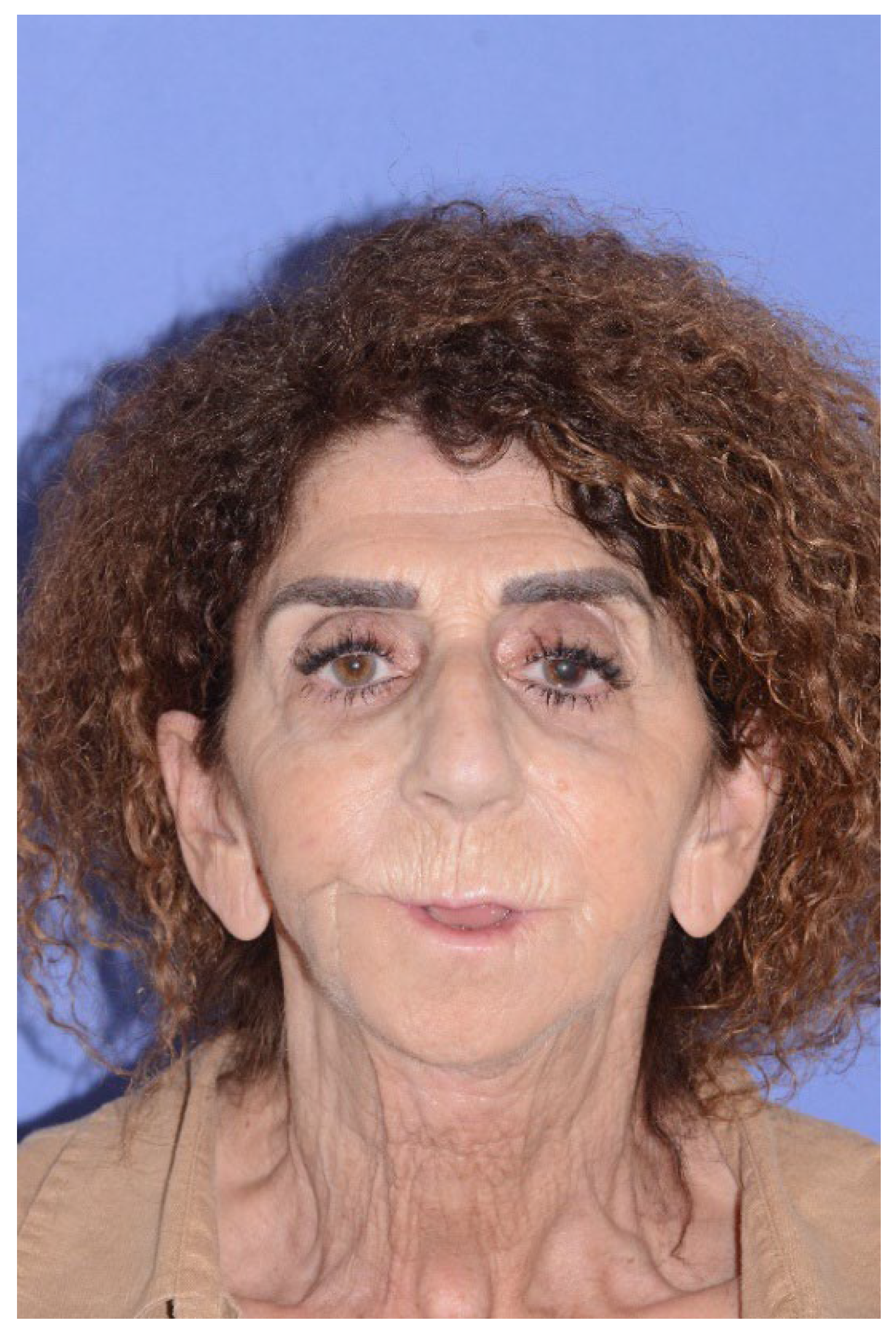

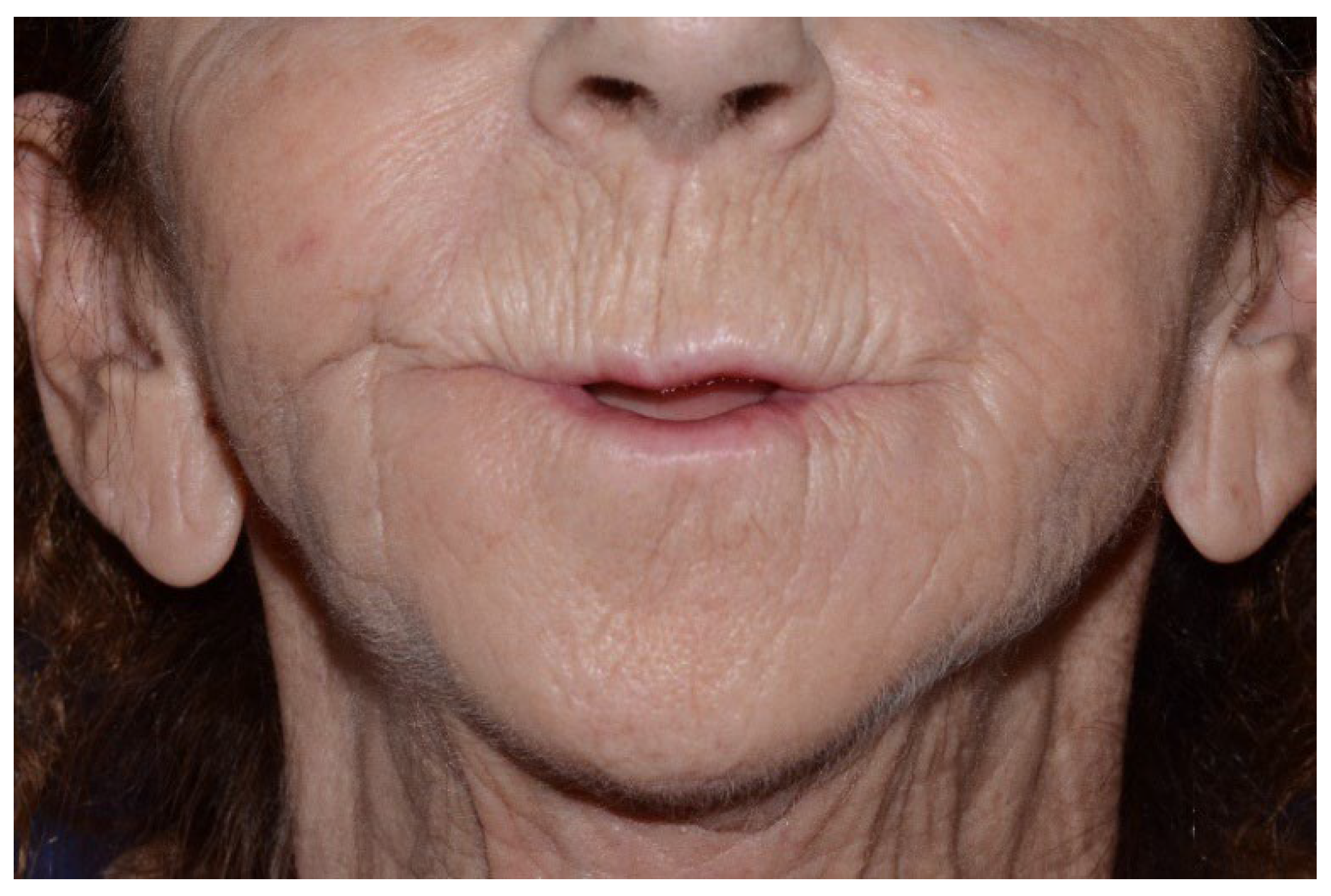

The main complaint of the patient, over the occasional pain, was the lip incompetence due to the dislocation of the symphyseal area of the mandible which pulled down the chin and lower lip, leading to the need of forced contraction of the mentalis muscle and orbicularis oris muscle to totally close the mouth (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The patient reported no sensory impairment.

After a clinical and radiologic examination, it was decided to propose a mandibular reconstruction with a CAD-CAM plate after repositioning of the bony fragments through a cervicotomic approach, which the patient accepted.

A 2.4 mm thick titanium plate was planned and produced in collaboration with Sintac (Sintac Srl, GPI, Trento, Italy) involving and reproducing the inferior border of the mandibular body, extending to one angle to another. This solution was thought to give stability to this very thin and fragile bone, and to promote bone healing through the fragments after cutting their margins to make them cruent. The robustness of this reconstructive plate allowed to plan rotational movements of the fragments, especially the symphyseal one, generating a higher crestal height (6.56 mm).

The prosthesis was designed after a project based on the patient’s specific anatomy, through a Virtual Surgical Planning (VSP) obtained through the CT scan’s files (.DICOM format) using Mimics (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) and Geomagic Freeform softwares.

VSP considered not just reapproximating the bone fragments respecting the patient’s anatomy, but the correct position of the mandibular condyles into the glenoid fossa in both sides and the correct yaw repositioning of mandibular rami.

Each bony fragment was stabilized with 4 2.0 mm bicortical locking screws, except for the left ramus, fixed with only 3 bicortical screws.

Both inferior alveolar nerves were isolated and respected, not causing any macroscopic injury.

She underwent surgical intervention in the month of July 2023, with no intraoperative or acute complications; she was hospitalised for 10 days and reported paramandibular bilateral oedema (compatible with post-operative sequelae) without any other complication. After dismissal, a regular clinical and radiologic follow-up was carried out: no acute or delayed complications were reported, except the bilateral edema of the sub- and peri-mandibular region, totally resolved approximately 6 weeks after surgery without any further medication.

The patient had developed anxiety and some depressive symptoms due to the previous trauma and all the medications related to it, carried out for a long time. She was referred to our Psychology Department and then taken on charge for four psychotherapeutic sessions with a diagnosis of PTSD due to the traumatic accident itself and the functional and morphological sequelae deriving from the failure of the first surgery.

3. Results

No delayed complication was registered: the patient started self-rehabilitation exercises through movements of opening/closing, lateral and forward shifts starting from 4 weeks after surgery to avoid tempura-mandibular ankylosis due to the lack of mobilization of the mandible.

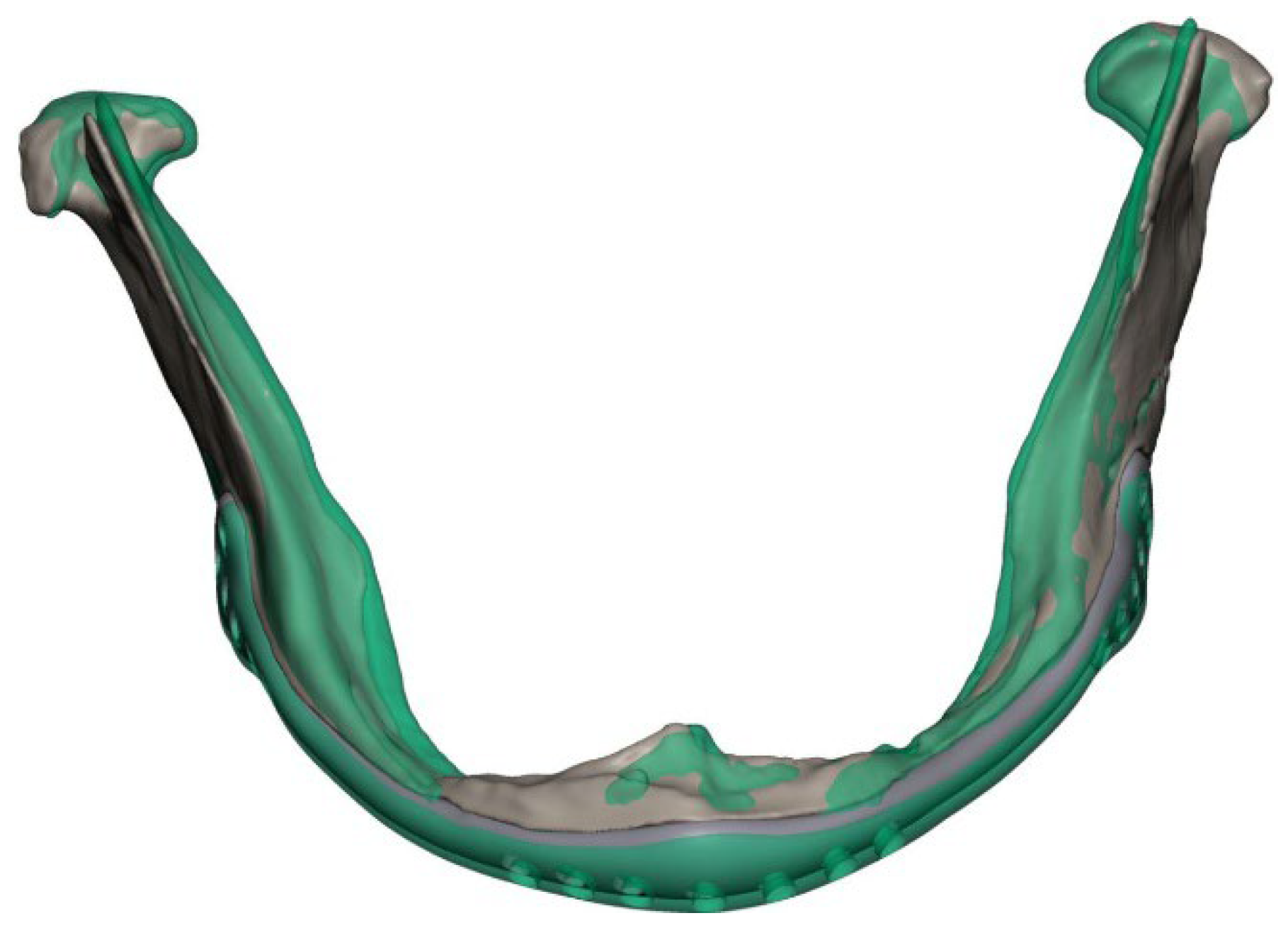

Post-operative CT scan was recorded 7 days after surgery, showing good positioning and fixation of reconstructive plate and screws on the mandible, as well as an optimal juxtaposition of bony fragments, guaranteeing optimal contact. .stl files were extrapolated from CT scan’s files, generating a 3D model, which was superimposed and compared with .stl files of the preoperative planning for volumetric accuracy’s analysis: the result of this qualitative analysis shows satisfying overlapping of the VSP with post-operative actual results (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), with just a mild external repositioning of mandibular rami compared to the planned; condylar heads were located in the correct antero-posterior and latero-lateral position.

Finally, she received a prosthodontic evaluation for rehabilitation of the edentulous mandible: after a new CT scan and 3D planning, it was decided to put 2 implants, regions 32 and 42, with a length of 5 mm (

Figure 9).

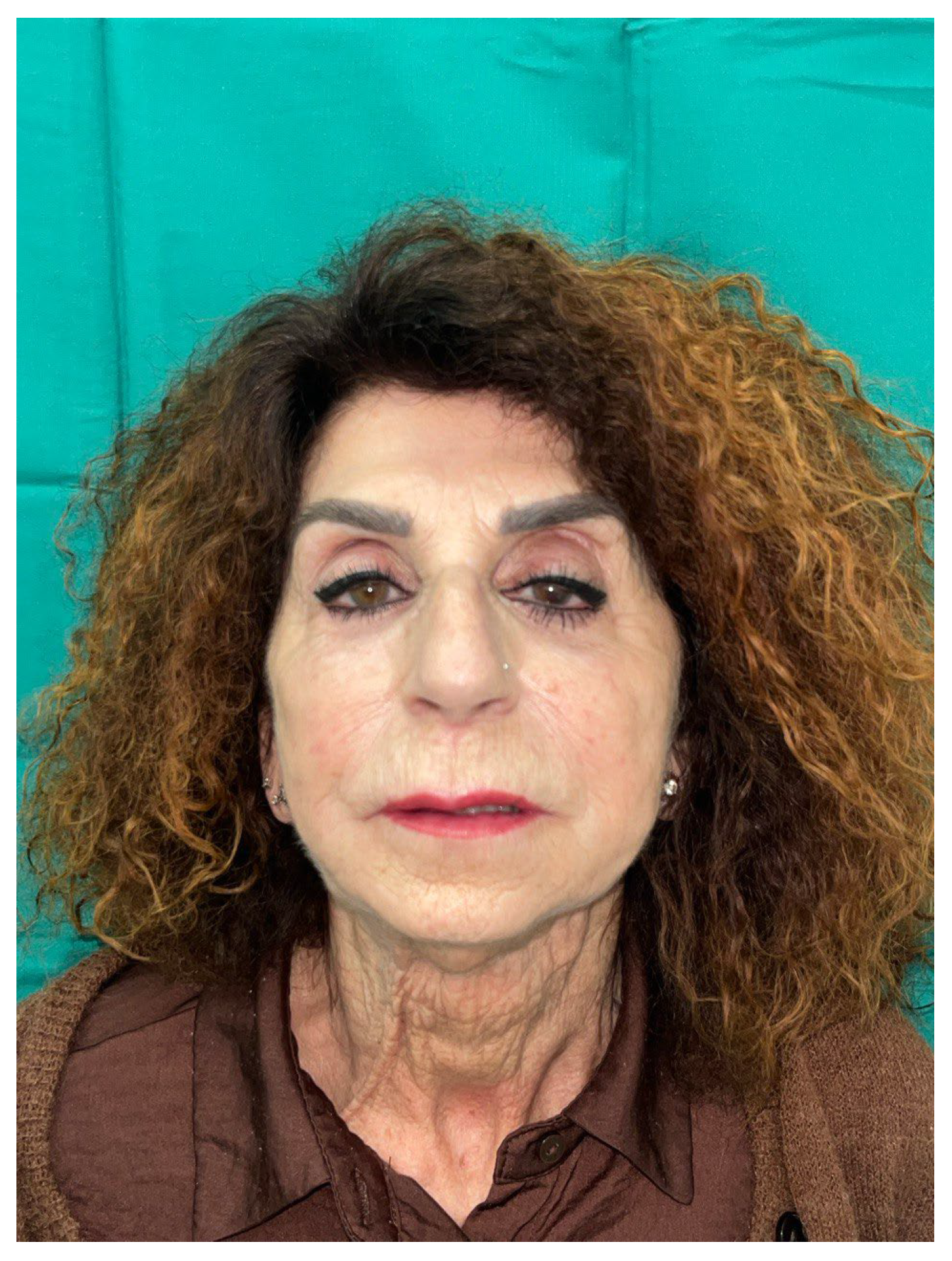

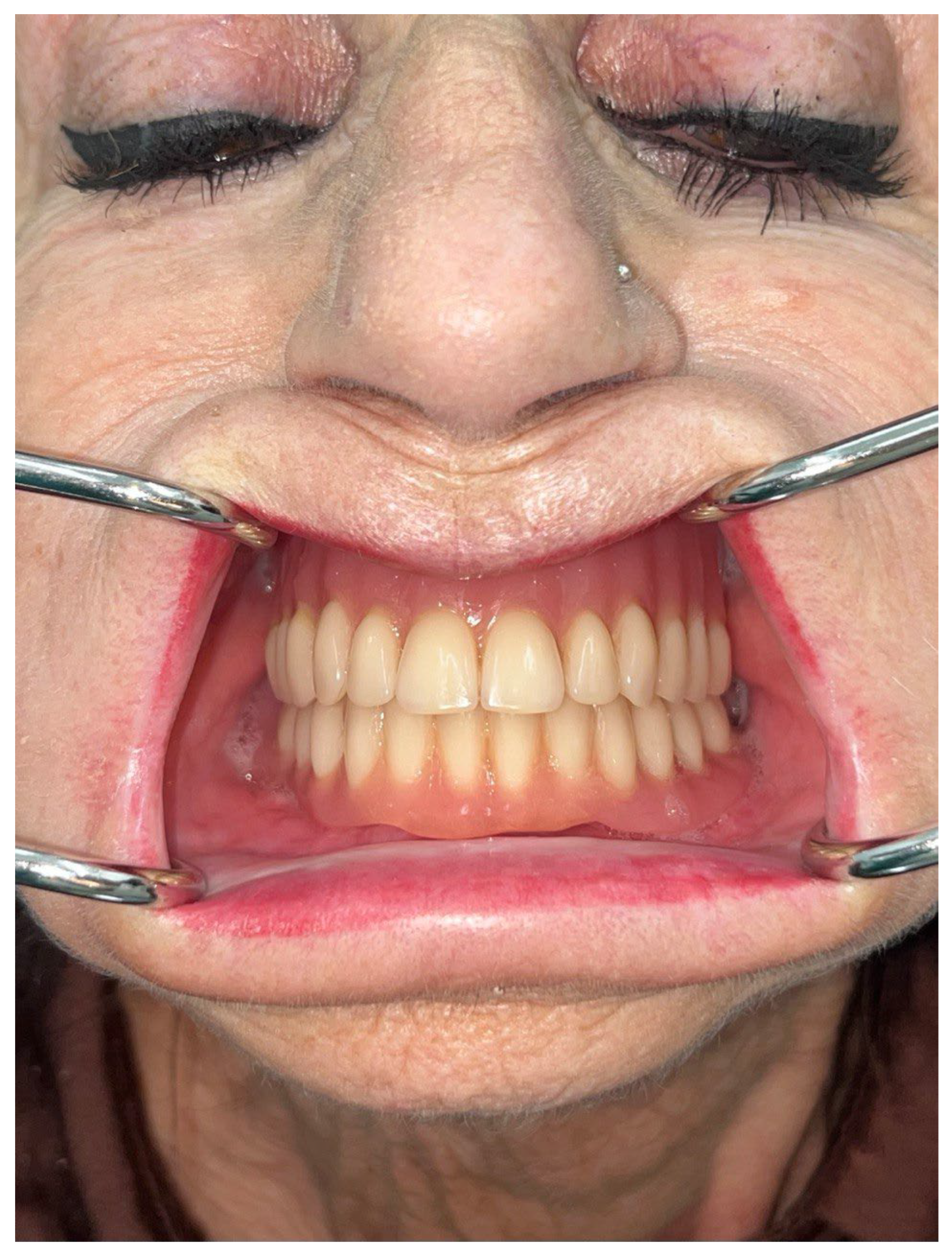

The patient currently has re-gained a fulfilling condition in terms of both function and morphology: labial competence has been restored, as well as mandibular kinetics, and no paresthesia or dysesthesia of both inferior alveolar nerves has been reported (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

The rehabilitation was completed with a mobile acrylic overdenture with ball attachments covering dental area from tooth 37 to tooth 47 (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

After making the patient fill out the general and extensively used General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), it was observed that she felt a satisfying recovery in terms of speech, chewing, swallowing and aesthetics.

After concluding the psychological rehabilitation, the patient has experienced relief of the anxious and depressive symptoms related to the events, and no chronic psychological or psychiatric sequelae have been observed.

4. Discussion

Atrophic mandible fractures represent a challenge in Maxillofacial Surgery traumatology, since they are weighed down by a higher complication rate due to reduced blood flow, smaller contact surface, and a structure characterized by a highly corticalized bone with a reduced height.

As shown in a retrospective study made by Ellis at al. [11] involving 32 patients with fractures of a totally edentulous and atrophic mandible treated with ORIF, an effective approach to these kinds of fractures should involve ORIF through the positioning of a reconstructive plate with a thickness of at least 2.0 mm, with at least three bicortical screws per bone fragment; in regard to the route chosen to reach expose the fractures, extraoral approach was the primary approach. This approach was preferred to obtain a reliable and rigid fixation through the optimal visualization of the bone fragments; it is indeed nowadays considered more appropriate to perform a rigid and stable fixation of the atrophic mandible through a correct visualization of the fracture than carrying out a total sovraperiosteal dissection, which leads to a greater bleeding risk, while the blood supply of the remaining periosteum above atrophic fragments is not considered reliable.

Some severely atrophic mandibles can also benefit from bone grafts in concomitance with the ORIF surgery, with iliac crest being the most used donor site [12], with the use of recombinant bone morphogenic protein to promote osteogenesis in the recipient site.

Conversely, some authors [13] describe the use of a less invasive technique for reduction and fixation of atrophic edentulous mandible’s fractures, involving the positioning of mini (or micro) plates at the fracture site, thus minimizing the risk of complications, such as infection, exposure of the osteosynthesis plates, damage to nerves or bulging to the surrounding soft tissues. This study shows satisfying results in terms of healing and stability in the cases treated – just a sensory disturbance of the lower lip observed in one patient, advocating for the use of a single miniplates positioned according to Champy’s technique or two miniplates, positioned nearby.

As the experience of Novelli et al. [14] shows, immediate healing after ORIF of atrophic mandible fractures with a very low incidence of post-operative complications can be obtained through a rigid fixation with 2.0-mm large locking plat and 2.4-thick titanium plates through subperiostal dissection.

In the present manuscript, we have reported a complex case of secondary reconstruction following bifocal mandible fracture on a severely atrophic patients, already developing plates’ failure and subsequent non-union of the bone.

We have decided to propose and then perform a CAD-CAM surgery because of the need to restore function as soon as possible in a patient that already had a delayed healing process due to the disruption and non-union: this enhanced the risk of developing a permanent impairment of mandibular kinetics with alterations in chewing and swallowing.

Moreover, CAD-CAM reconstructive plate has given an optimal rigidity with total load bearing in absence of the capability of the extremely atrophic mandible to withstand tensional and compressive forces.

CAD-CAM technique has demonstrated to be effective in this treatment, since it has provided a strong, stable and long-lasting solution to stabilize the plurifocal fracture and to treat the non-union thanks to the cutting of the fibrous edges of the mandible prior to the positioning.

There are actually few reports in the scientific literature about atrophic mandible’s reconstruction with patient-specific plates, even though some authors have approached CAD-CAM techniques to treat this pathology. Maloney et al. [15], in 2018, highlighted the validity and accuracy of a VSP and the positioning of a patient-specific case, reporting two cases treated with the above-mentioned methods, one with a pre-bent plate and the other with a CAD-CAM fabricated plate, pointing out that production times can overcome surgical urgent needs. We believe that 3D printed PSI can be used with a high level of accuracy in non-emergent or urgent cases (up to 14 days after trauma), including bone margins curettage or resection when fibrosis has started.

Abbate et al. [16] have reported the treatment of 5 patients affected by fractures of the atrophic mandible through VSP, in-house 3D printing of a stereolithographic model and pre-plating of a 2.4 titanium plate based on patients’ anatomy, obtaining a patient-specific plate. All the patients treated healed well, and overlapping of VSP to post-operative CT scans revealed obtained discrepancies’ values inferior to 1.5 mm.

One example is the study made by Caruso et al. [17], which shows the digital workflow of CAD-CAM technique in 5 patients treated with VSP and PSI for reduction and stabilization of Luhr Class III fractures with titanium plates and screws: all the patients treated showed good healing and successful fracture reduction and implant placement compared with preoperative planning.

As shown in a case report by Duran Rodriguez et al. [18], CAD-CAM technology can be exploited in some complex case of totally (or partially) edentulous mandible for design and production of a Gunning splint to restore vertical height and symmetry in cases of condyle fractures, providing a guide to reduce the fracture and to shorten stabilization’s times.

As far as we know, there is no report of a severely atrophic mandible’s secondary reconstruction with subsequentimplant rehabilitation.

5. Conclusions

As demonstrated by our report, CAD-CAM technique and secondary reconstruction following complex fracture in severely atrophic mandible can be an optimal option in an edentulous mandible, lacking dental guide for repositioning, where condyle repositioning into glenoid fossa is fundamental to avoid articular dysfunction and/or mandibular deviation.

This can be done through a VSP, 3D printing of a stereolithographic model and, whenever possible, with CAD and 3D printing of a patient-specific reconstructive plate, in order to reduce intraoperative time and possible errors.

We believe that this application of CAD-CAM technique has great advantages that should be exploited for specific complex cases with little or no anatomic or dental reference point, providing adequate vertical and transverse positioning of mandibular bones.

Patient’s sample should be enlarged, and mandibular dynamics should be examined in depth in the future.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, F.C., A.T.; methodology, G.B., A.T.; data curation, F.C., D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C., D.D.; writing—review and editing, D.D., G.B., A.T.; supervision, G.B., A.T.; project administration, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, but required no specifical Ethical Committee approval because the patient was treated according to the Good Clinical Practice principles”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study”.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAD-CAM |

Computer-Aided Design Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| PSI |

Patient-Specific Implant |

| VSP |

Virtual Surgical Planning |

References

- Conforte JJ, Alves CP, Sánchez Mdel P, Ponzoni D. Impact of trauma and surgical treatment on the quality of life of patients with facial fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 May;45(5):575-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull AM, Lowe T, Devlin M, Finlay P, Koppel D, Stewart AM. Psychological consequences of maxillofacial trauma: a preliminary study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003 Oct;41(5):317-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalloo R, Lucchesi LR, Bisignano C, Castle CD, Dingels ZV, Fox JT, Hamilton EB, Liu Z, Roberts NLS, Sylte DO, Alahdab F, Alipour V, Alsharif U, Arabloo J, Bagherzadeh M, Banach M, Bijani A, Crowe CS, Daryani A, Do HP, Doan LP, Fischer F, Gebremeskel GG, Haagsma JA, Haj-Mirzaian A, Haj-Mirzaian A, Hamidi S, Hoang CL, Irvani SSN, Kasaeian A, Khader YS, Khalilov R, Khoja AT, Kiadaliri AA, Majdan M, Manaf N, Manafi A, Massenburg BB, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Morrison SD, Nguyen TH, Nguyen SH, Nguyen CT, Olagunju TO, Otstavnov N, Polinder S, Rabiee N, Rabiee M, Ramezanzadeh K, Ranganathan K, Rezapour A, Safari S, Samy AM, Sanchez Riera L, Shaikh MA, Tran BX, Vahedi P, Vahedian-Azimi A, Zhang ZJ, Pigott DM, Hay SI, Mokdad AH, James SL. Epidemiology of facial fractures: incidence, prevalence and years lived with disability estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study. Inj Prev. 2020 Oct;26(Supp 1):i27-i35. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043297. Epub 2020 Jan 8. Erratum in: Inj Prev. 2023 Feb;29(1):e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Juncar M, Tent PA, Juncar RI, Harangus A, Mircea R. An epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures: a 10-year cross-sectional cohort retrospective study of 1007 patients. BMC Oral Health. 2021 Mar 17;21(1):128. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brasileiro BF, Passeri LA. Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures in Brazil: a 5-year prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006 Jul;102(1):28-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanala S, Gudipalli S, Perumalla P, Jagalanki K, Polamarasetty PV, Guntaka S, Gudala A, Boyapati RP. Aetiology, prevalence, fracture site and management of maxillofacial trauma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2021 Jan;103(1):18-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stacey, D Heath M.D.; Doyle, John F. D.D.S.; Mount, Delora L. M.D.; Snyder, Mary C. M.D.; Gutowski, Karol A. M.D.. Management of Mandible Fractures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 117(3):p 48e-60e, March 2006. [CrossRef]

- Panesar K, Susarla SM. Mandibular Fractures: Diagnosis and Management. Semin Plast Surg. 2021 Oct 11;35(4):238-249. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cawood JI, Howell RA. A classification of the edentulous jaws. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988 Aug;17(4):232-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luhr HG, Reidick T, Merten HA. Results of treatment of fractures of the atrophic edentulous mandible by compression plating: a retrospective evaluation of 84 consecutive cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996 Mar;54(3):250-4; discussion 254-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis E 3rd, Price C. Treatment protocol for fractures of the atrophic mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Mar;66(3):421-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Hidalgo A, Altay MA, Atencio IC, Manlove AE, Schneider KM, Baur DA, Quereshy FA. Management of fractures of the atrophic mandible: a case series. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015 Jun;119(6):619-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugino H, Takagi S, Oya R, Nakamura S, Ikemura K. Miniplate osteosynthesis of fractures of the edentulous mandible. Clin Oral Investig. 2005 Dec;9(4):266-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novelli G, Sconza C, Ardito E, Bozzetti A. Surgical treatment of the atrophic mandibular fractures by locked plates systems: our experience and a literature review. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2012 Jun;5(2):65-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reconstruction of an Atrophic Mandibular Fracture via a Customized, Intraoral Approach: A Novel Technique in the Treatment of Atrophic Mandibular Fractures Rekawek, PeterYoshikane, Frances et al. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Volume 80, Issue 9, S94 - S95.

- Abbate, V.; Committeri, U.; Troise, S.; Bonavolontà, P.; Vaira, L.A.; Gabriele, G.; Biglioli, F.; Tarabbia, F.; Califano, L.; Dell’Aversana Orabona, G. Virtual Surgical Reduction in Atrophic Edentulous Mandible Fractures: A Novel Approach Based on “in House” Digital Work-Flow. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1474. [CrossRef]

- Caruso DP, Aquino VM, Hajibandeh JT. Management of Atrophic Edentulous Mandible Fractures Utilizing Virtual Surgical Planning and Patient-Specific Implants. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2024 Jun 6:19433875241259808. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Duran-Rodriguez G, Gómez-Delgado A, López JP. Management of Bilateral Condylar Fractures in an Edentulous Patient with Atrophic Mandible Using CADCAM Technology. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2022 Mar;21(1):124-128. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Figure 1.

Preoperative OPT, showing dislocation of symphyseal area and rupture of microplates positioned in previous surgery.

Figure 1.

Preoperative OPT, showing dislocation of symphyseal area and rupture of microplates positioned in previous surgery.

Figure 2.

3D reconstruction of preoperative CT scans, showing dislocation of symphyseal area and rupture of microplates positioned in previous surgery.

Figure 2.

3D reconstruction of preoperative CT scans, showing dislocation of symphyseal area and rupture of microplates positioned in previous surgery.

Figure 3.

3D reconstruction of preoperative CT scans, showing dislocation of symphyseal area and rupture of microplates positioned in previous surgery.

Figure 3.

3D reconstruction of preoperative CT scans, showing dislocation of symphyseal area and rupture of microplates positioned in previous surgery.

Figure 4.

3D reconstruction of preoperative CT scans, showing dislocation of symphyseal area and rupture of microplates positioned in previous surgery.

Figure 4.

3D reconstruction of preoperative CT scans, showing dislocation of symphyseal area and rupture of microplates positioned in previous surgery.

Figure 5.

Clinical pictures showing lip incompetence due to the dislocation of the symphyseal area of the mandible, pulling down the chin and lower lip.

Figure 5.

Clinical pictures showing lip incompetence due to the dislocation of the symphyseal area of the mandible, pulling down the chin and lower lip.

Figure 6.

Clinical pictures showing lip incompetence due to the dislocation of the symphyseal area of the mandible, pulling down the chin and lower lip.

Figure 6.

Clinical pictures showing lip incompetence due to the dislocation of the symphyseal area of the mandible, pulling down the chin and lower lip.

Figure 7.

3D reconstruction, overlapping and comparison between preoperative (green solid) versus post-operative (grey solid) .stl models, generated from DICOM files.

Figure 7.

3D reconstruction, overlapping and comparison between preoperative (green solid) versus post-operative (grey solid) .stl models, generated from DICOM files.

Figure 8.

3D reconstruction, overlapping and comparison between preoperative (green solid) versus post-operative (grey solid) .stl models, generated from DICOM files.

Figure 8.

3D reconstruction, overlapping and comparison between preoperative (green solid) versus post-operative (grey solid) .stl models, generated from DICOM files.

Figure 9.

Postoperative OPT showing dental implant positioning in symphyseal mandibular bone and overlying acrylic overdenture (radiolucent).

Figure 9.

Postoperative OPT showing dental implant positioning in symphyseal mandibular bone and overlying acrylic overdenture (radiolucent).

Figure 10.

Clinical aspect 21 months after surgery: resolution of labial incompetence, restoration of mandibular original profile and smile, no impairment of neurological or motility function.

Figure 10.

Clinical aspect 21 months after surgery: resolution of labial incompetence, restoration of mandibular original profile and smile, no impairment of neurological or motility function.

Figure 11.

Clinical aspect 21 months after surgery: resolution of labial incompetence, restoration of mandibular original profile and smile, no impairment of neurological or motility function.

Figure 11.

Clinical aspect 21 months after surgery: resolution of labial incompetence, restoration of mandibular original profile and smile, no impairment of neurological or motility function.

Figure 12.

Final result: patient wearing her acrylic overdenture attached to the 2 implants.

Figure 12.

Final result: patient wearing her acrylic overdenture attached to the 2 implants.

Figure 13.

Final result: patient wearing her acrylic overdenture attached to the 2 implants.

Figure 13.

Final result: patient wearing her acrylic overdenture attached to the 2 implants.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).