1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been mounting interest in improving the psychosocial integration of people with

reduced mobility [

1,

2,

3]. One factor, in particular, has gained relevance in intervention programmes to improve the group’s psychosocial integration, strength and quality of life generally, and that factor is empowerment [

4].

1.1. The Role of Empowerment and Functional Diversity

While "empowerment" can mean to give power, it commonly refers to a person’s strengthening of capabilities [

4]. The concept thus refers to each person’s potential to achieve self-defined objectives and goals, approaching life in terms of personal and social opportunities [

5,

6].

For other authors [

7,

8,

9,

10], the empowerment construct includes personal attributes such as a sense of competence, influence, and self-efficacy, which drive behaviours aimed at achieving specific results and goals. Therefore, the empowerment process means overcoming a situation of powerlessness and gaining control over one's own life through individual capabilities and resources [

4], with the aim of enhancing self-determination, autonomy, decision-making, and quality of life, generally.

Based on this description, Deere and Leon [2002] specify that empowerment is not a linear process, i.e., it does not have a clearly defined beginning and end and it is not identical for all individuals. Instead, empowerment is experienced in a different, somewhat unique way by each person and develops in a distinct way according to personal history and context. It may thus result from various experiences, such as educational, organisational, work processes, etc. For example, empowerment has been studied in various disciplines to understand and promote the integration of disadvantaged or socially vulnerable groups, such as ethnic minorities [

12], women [

13] and the role of accounting in supporting familyand people with functional diversity [

14].

Functional diversity can be defined as the difference in a person's functioning compared to most of the population when performing everyday tasks (moving, reading, holding, going to the bathroom, communicating, relating, etc.). The impact on quality of life depends on a large array of variables, including contextual factors, and on the type of functional diversity in question [

15].

In relation to functional diversity and quality of life, a number of authors have focused their efforts on studying the influence of different constructs, such as empowerment.

For example, Suriá [

16] analysed the empowerment of university students with and without disabilities and its association with academic performance. The results reflected that students without disabilities were more greatly empowered compared to students with disabilities.

For comparative purposes, another study analysed the degree of empowerment of a group of young people according to the type of disability and the stage at which the disability was acquired. High levels of empowerment were observed among young people, and to a greater extent in young people with acquired disabilities, as well as with motor and visual disabilities [

15]. Focusing on the related literature, empowerment has been linked to many other theories that also refer to self-improvement e.g.: behaviours oriented towards achieving results and defined goals, for example, the theory of competencies based on basic knowledge; the theories of process and/or intervention evaluation; and the theory of resilience.

1.2. The Study of Empowerment and Resilience

There has been mounting interest in the resilience construct in the scientific community. The term is borrowed form the field of physics and is defined as the ability of a material or substance to return to its original shape [

17]. Thus, in the context of psychology, the resilience construct refers essentially to an individual's ability to face adversity or negative life experiences and to emerge stronger from them, leading them to develop social, academic and vocational skills, despite exposure to stress and serious difficulties [

18].

The theory of resilience is related to the concept of empowerment because it focuses on a person’s potential and development. The relationship between being resilient and being empowered is established in Grottberg’s now classic formula of resilience [

19]: I have (networks of belonging), I am (body-mind-spirit integration), and I can (I am powerful in the sense that I am able to face, to be, to enjoy, to resolve, to bond, to protect myself, to take care of, to work, to feel, etc.).

The capacity for resilience is made up of personal and environmental factors that help people to face and overcome the different obstacles emerging in their lives [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. We can infer that resilience is a dynamic feature, composed of a series of social and intrapsychic processes that take place over time, giving rise to combinations of individual attributes and the person’s environment. The concept therefore refers to an interactive process in which several components intervene, notably Acceptance of Self and of Life, Social Competence and Self-Discipline [

20,

22,

23].

In this sense, empirical evidence suggests that resilience is positively associated with the individual’s correct functioning in childhood [

19], in adolescence [

18] as well as in adulthood [

22]. Nevertheless, these relationships become more complex when considering the different dimensions that make up resilience. For example, different authors have analysed the relationship between this construct and the proper functioning of people across various personal domains, such as subjective well-being [

3], optimism [

24], and happiness [

25]. Although positive relationships have been found between some resilience dimensions, such as Acceptance of Self and of Life and Optimism, or between Social Competence and Social Skills, the relationship between Self-Discipline and these domains is not so clear [

26]. This fact suggests that not all the dimensions that make up resilience act in the same way on an individual’s well-being. It thus appears that differential resilience patterns must be considered when analysing the relationship with other variables associated with quality of life.

Based on the concept of resilience and focusing on empowerment, similarities with the resilience dimensions mentioned above can be found in several empowerment components such as: Self-Esteem-Self-Efficacy, Community Activism-Autonomy, Appropriate Anger, and lastly, Optimism-Control over the Future. A direct link may therefore exist between empowerment and resilience. In turn, the fact that both constructs are composed of different factors could imply that the resilience dimensions do not share the same significance and, thus, that each dimension has a different weight in the development of empowerment.

In relation to people with functional diversity, different authors emphasize the relationship between empowerment and resilience [

8,

27,

28,

29]. The literature on the subject, however, has focused mainly on people with mental diversity [

29,

30], overlooking the issue of empowerment of people with other types of functional diversity, such as reduced mobility. Moreover, focusing on resilience in adults with reduced mobility, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have hitherto been conducted on the possible relationship between different profiles of resilience and empowerment. Finally, no study seems to have been published either on the different levels of empowerment found in the distinct resilience profiles of adults with reduced mobility, addressing not only the empowerment construct as a whole, but also each empowerment sub-dimension (e.g., Self-Esteem-Self-Efficacy, Power/Powerlessness, Community Activism-Autonomy, Optimism-Control over the Future, and Appropriate Anger).

Based on all the above, the aim of the study was to further explore the relationship between empowerment and resilience in adults with reduced mobility. To this end, two objectives were proposed. The first was to identify in a sample of people with reduced mobility whether there were any possible combinations of different resilience dimensions that gave rise to different profiles depending on the weight of each resilience dimension. Based on this objective, we expected that:

H1. A group of adults with reduced mobility presents a variety of resilience profiles depending on the weight of each resilience component.

Subsequently, we analysed whether the resilience profiles obtained presented any statistically significant differences in the various empowerment factors. This second objective would, to a certain extent, validate the criteria of the encountered profiles. It would also confirm their usefulness to elaborate intervention programmes directed towards improving the resilience and empowerment of people with reduced mobility. This objective led to the following second hypothesis:

H2. Statistically significant empowerment differences exist based on the resilience profiles obtained. Specifically, the group with high resilience will score high on the empowerment dimensions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

For reasons of accessibility, the sample was intentional. It consisted of 94 people with reduced mobility belonging to the ASPAYM association (Association of Paraplegics and People with Great Physical Disabilities) in the Valencian Community, a Spanish association with 900 members. The eligible population was initially made up of the 142 members aged over 18 years who attended one of the meetings periodically convened by the association in Alicante (Spain). Of these, 51% were female and 49% male, aged between 21 and 62 years (M= 29.35; SD= 6.43). Regarding education levels, 44.00% had primary education, 30.00% secondary education, 17.20% university education and 8.80% indicated that they had no education. In terms of their occupation, 37.90% indicated that they were neither studying nor working at the time, 35.40% that they were in active employment, 15.30% that they were studying, and 11.30% performed housework.

To check that there were no statistically significant differences between the participants, we used the Chi-square test for homogeneity of the frequency distribution, sex x age, (χ2 = 10.09; p = .17).

2.2. Procedure

The data collection procedure consisted of applying the scales to the participant sample. These were administered to 94 members of the association. The latter had expressed their wish to collaborate after attending presential meetings in which the researcher, linked to the association, had explained the study objective. The questionnaires used to collect the information were administered in person at the same meetings once the participants had given their consent in writing. The scales were administered adapting to the participant’s conditions and the application time was approximately 20 minutes. The data was collected between January and September 2024.

2.3. Instruments

- An ad hoc sociodemographic questionnaire to collect the sociodemographic data: sex, age, level of education, and employment status.

- The Spanish version [

31] of the Resilience Scale [

32]. This scale is made up of 25 items that are answered on a seven-point Likert scale (from 1 = "strongly disagree", to 7 = "strongly agree"). Higher scores are indicators of greater resilience, and scores range from 25 to 175 points. The internal consistency index obtained was high (α= 0.93) and two differentiated factors were found (as in the original version): Factor 1. Personal competence, understood as the recognition of factors of personal ability, independence, mastery, perseverance, ability, etc. — this factor explained 44.00% of the variance; and Factor 2. Acceptance of Self and of Life, which equates to adaptation, flexibility, etc., with an explained variance of 42.00%.

To make sure the scale was suitable for the characteristics of the specific study sample, the psychometric properties of the scale were checked using Factor Analysis with Principal Components (AFECP). As previously reported in other works that used the original scale [30, 33-35), a third factor was found in the present study. It was coined Factor 3. Self-discipline: self-control, which enables the person to avoid emotional exhaustion and to channel emotional energy in difficult situations. The Bartlett sphericity test [[χ2 = 103,552 (p< ,001] and the sample adequacy measure KMO (0.62) was previously favourable towards performing the AFECP. Thus, the total scale variance was explained by 78.46%. Factor 1 explains 36.6% of the variance; Factor 2 explains 25.24% of the variance; and Factor 3 explains 16.84% of the variance. The internal scale consistency (Cronbach's alpha) was high (α = 0.89).

- "Empowerment scale", developed by Rogers et al., [

36], designed to measure the level of this potential capacity. It was translated into Spanish. The scale has a total of 28 items, answered on a 4-point Lickert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). The information requested includes aspects related to the subject's self-perceived decision-making capacity. The maximum score is 112 points, but the score was divided into three ranges based on thresholds in the following way: low level = from 29 to 56; medium level = from 57 to 84; and high level = from 85 to 112.

This scale was chosen according to several criteria: because its application is brief; because it is validated for the young and adult population; and finally, because of the psychometric properties shown in the original version [

36]. Thus, a reliability of 86% (α= .86) and an explained variance of 53.9% were found for the original scale, defined by five factors: Factor 1. Self-esteem-Self-efficacy (explains 24.5% of the total variance; Factor 2. Power/Powerlessness (12.4% of total variance explained); Factor 3. Community Activism-Autonomy (explains 7.6% of the total variance); Factor 4. Optimism-Control over the future (explains 5.4% of the total variance); Factor 5. Appropriate anger (explains 4% of the total variance).

To verify whether the scale was suitable for this study, the psychometric properties of the scale were checked in the sample. To this end, the Factor Analysis with Principal Components (AFECP) was used, showing an explained variance of 52.60%, distributed in 5 factors. Previously, Barlett's sphericity test [χ2 = 102.514 (p<.001)] and the sample adequacy measure KMO (0.58) was favourable towards performing the AFECP. Reliability was tested using Cronbach's alpha, which indicated a reliability of 82.00% (α= .82).

2.4. Data Analysis

Cluster analysis (the quick cluster analysis method) was used to identify the resilience profiles. A non-hierarchical method was chosen because it permitted reassignment, in other words, it allowed an individual who had been assigned to one group at a certain stage of the process to be reassigned to another group if this reassignment optimised the selection criteria.

The profiles were defined based on the different combinations of the three resilience factors assessed through the "Resilience Scale" [

32]: Personal Competence, Acceptance of Self and Life, and Self-Discipline. The criterion followed to define the number of clusters was to maximise intergroup differences in order to establish the largest possible number of groups with different combinations in the two dimensions of the construct. In addition, the theoretical viability and psychological significance of each group representing the different resilience profiles was also added to this criterion.

After establishing the different groups through cluster analysis, analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed to examine the statistical significance of the differences between the groups in the empowerment dimensions. The η2 index was applied to analyse the magnitude or size of the effect of these differences.

Finally, for the analyses in which comparisons were statistically significant, post hoc tests were conducted to identify the groups that presented the differences. The Scheffé method was followed because the number of participants varied in each group and this test does not require the sample sizes to be equal. We also calculated the effect size (standard mean difference or d-index [

37] to calculate the magnitude of the observed differences. Data were analysed using the SPSS statistical package version 19.0.

3. Results

3.1. Combinations of Different Resilience Dimensions

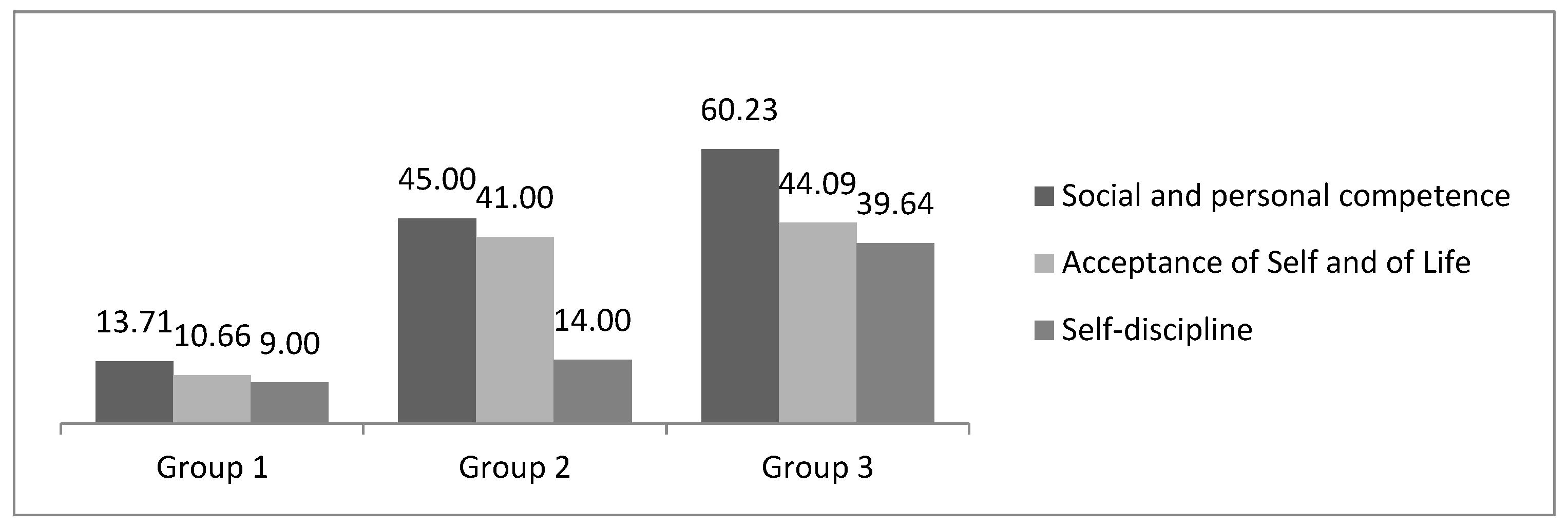

Using the clustering technique, which identifies the highest possible similarity within groups and the most pronounced differences between them, three distinct profiles based on resilience dimensions were identified (see

Figure 1). The first cluster included 26 participants (27.65%), who displayed low levels across all three resilience dimensions. The second cluster comprised 32 individuals (34.04%), showing high scores in Personal Competence and Self-Acceptance, but low scores in Self-Discipline. The third cluster, consisting of 36 participants (38.29%), was mainly defined by high scores in all three resilience dimensions.

3.2. Resilience Profile Inter-Group Differences Regarding Empowerment

As can be observed in

Table 1, participants generally presented average levels of empowerment in Group 2 (M=57.88, SD=14.82) and Group 3 (M=59.98, SD=16.59), while a low empowerment level was found in Group 1 (M=54,02, DT=13,38). Regarding the mean scores of the global scale, statistically significant differences were observed in the three clusters (F(2,94) = 7.38, p < .001, η2 = .54), and Group 3 presented higher means than Group 2 (d = 0.58) and Group 1 (d = 0.84). Group 2 also obtained higher mean scores than Group 1 (d = 0.61).

With respect to the factors composing empowerment, statistically significant differences were found for four of the five empowerment factors, the exception being self-efficacy-self-esteem. We then examined the empowerment factor scores that presented differences and the post hoc comparisons to determine the groups between which the differences existed. We thus found that statistically significant differences existed between the clusters with respect to Factor 2, "Power/Powerlessness", (F(2,94) = 3,78, p< ,05, η2 = ,28), and that the group with high scores in the three resilience dimensions (Group 3) obtained higher scores than Group 2 as well as higher scores than the group with low scores in these dimensions (Group 1) for this factor. Thus, Group 3 had higher mean scores than Group 2 (d = 0.44) as well as higher mean scores than Group 1 (d = 0.52).

In relation to Factor 3, related to "Community Activism", Group 3 presented higher scores than Group 2 (F(2.94) = 17.40, p < .001, η2 = .39), (d = 0.46) and than Group 1 (d = 0.52). Similarly, Group 2 showed higher means than Group 1 (d = 0.39).

With regard to Factor 4, concerning "Optimism-Control over the future", statistically significant differences were also observed between the three clusters, Group 3 notably presenting mean scores above that of Group 1, (F(2,94) = 9,22, p < ,001, η2 = ,42, d = 0,53) and of Group 2 (d = 0,40).

A similar trend was found in the post hoc analysis regarding Factor 5, "Appropriate anger", in which statistically significant differences were observed between the clusters (F(2.94) = 3.86, p<.05, η2 = .21). Thus, the group that reported high scores on the three resilience dimensions (Group 3) showed higher scores than Group 2 and than the group with low scores on these dimensions (Group 1). The effect size of these differences ranged from (d = 0.34 to 0.39).

4. Discussion

In this paper, we explored the relationship between resilience and empowerment in people with reduced mobility. To this end, different objectives were proposed. The first was to analyse the possible combinations of the participants’ resilient dimensions to determine the weight of these resilient profiles in the development of empowerment.

Regarding the first objective, distinct resilience profiles were identified, each characterized by different combinations of resilience dimensions. Through a cluster analysis, three resilience profiles emerged, confirming the first hypothesis. These profiles included:

Group 1, consisting of individuals with low scores across all three resilience components. Group 2, characterized by high scores in Social Competence and Acceptance of Life and Self, but low scores in Self-Discipline. Group 3, which exhibited high scores in all three resilience dimensions, namely Social Competence, Self-Discipline, and Acceptance of Self and Life. These findings validate the first hypothesis of the study.

From these results, several key observations can be made. First, Group 1 represents individuals with disabilities who demonstrate low resilience levels across all dimensions. This profile is associated with poorer psychological adjustment and overall lower quality of life, reinforcing the notion that not all individuals with reduced mobility adapt positively to living with a disability [

2]. Second, Group 2 presents a distinct resilience pattern, with notable strengths in Acceptance of Self and Life, as well as Social Competence, but low levels of Self-Discipline. These results suggest that not all dimensions of resilience contribute equally to the development of resilient capacity [

26,

30]. Finally, Group 3, as well as Group 2 (which displayed high scores in Acceptance of Self and Life and Social Competence), supports previous theories suggesting that living with reduced mobility can foster personal strength and enhance coping abilities [

1]. This aligns with findings from other studies indicating that individuals with functional diversity often exhibit high levels of resilience [

8,

9].

Regarding the second objective, the findings support the second hypothesis, which proposed that statistically significant differences in empowerment would be observed among the identified clusters. The results confirmed this hypothesis, as four out of the five empowerment factors showed significant differences, with Self-Efficacy/Self-Esteem being the only exception.

These findings contribute to validating the existence of distinct resilience profiles while also enhancing the understanding of the relationship between resilience and empowerment. Overall, participants demonstrated moderate levels of empowerment. This aligns with previous research suggesting that individuals with functional diversity, particularly those with reduced mobility, often develop a sense of control over their lives and exhibit relatively indifferent reactions to stigma [

28,

38].

However, it is important to note that these findings do not suggest that individuals with disabilities do not experience negative emotions. Rather, they indicate that positive and negative emotions coexist in challenging circumstances, with negative emotions potentially serving as a catalyst for developing coping mechanisms and adapting effectively [

38].

When examining the resilience-based groups and their average empowerment levels, it is particularly noteworthy that Group 3, which scored high across all three resilience dimensions, also achieved the highest empowerment scores across most factors. This finding aligns with existing research suggesting that resilience is shaped by a variety of personal and contextual variables and tends to develop through experiences of adversity—such as living with a physical disability. Thus, it is reasonable to expect a connection between the components of resilience and the dimensions of empowerment [

3].

Further support for this relationship can be found in the distribution of participants: Group 3 (high resilience) included more individuals than the groups with lower resilience, indicating that a generalised resilient profile may be more common than a low-resilience one within the studied population.

Additionally, the strength of the association between empowerment and resilience is underscored by the effect sizes observed. Group 3 consistently outperformed Group 1 (low resilience) on empowerment measures, with notably large effect sizes in several key areas: Factor 2: Power/Powerlessness, Factor 3: Community Activism, Factor 4: Optimism and Future Control and Factor 5: Appropriate Expression of Anger

These results indicate that individuals with higher levels of Social Competence, Acceptance of Self and Life, and Self-Discipline—the three core dimensions of resilience—are also more likely to exhibit higher empowerment in these domains.

Several scholars [

39,

40] have pointed out that empowerment is driven by behaviors aimed at achieving specific personal or collective goals. In this context, the resilience dimensions appear to function as internal enablers—skills and attitudes that promote a stronger sense of agency and goal-directed action.

Along the same lines, Zimmerman (41) points out that the intrapersonal dimension of empowerment comprises attributes of the self as a sense of social and personal competence. Thus, the resilient dimension of Social and Personal Competence would encompass behaviours necessary for interpersonal relationships, such as expressing feelings, attitudes, desires, opinions, or rights in a way that is appropriate to the situation, respecting those behaviours in others (39). In turn, Personal Competence embraces aspects related to a person's capacity, mastery, perseverance, and ability, among other constructs (42). This is most reflected in the empowering factors related to power/powerlessness, optimism/control over the future, and appropriate anger.

On the other hand, Factor 1: Self-Esteem/Self-Efficacy did not show significant differences between the resilience groups. One possible explanation is the persistent influence of societal beauty standards and stereotypes, which may negatively affect the self-perception of individuals with disabilities [

26]. This could account for consistently lower scores on self-esteem-related items across all groups, regardless of resilience level.

Taken together, the findings support the notion that resilience and empowerment are closely interlinked, with Acceptance of Self and Life and Social Competence appearing to be the most influential resilience components in fostering empowerment.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite these valuable insights, the study has several limitations. The small sample size limits generalizability. Although access to a larger group of participants with reduced mobility can be challenging, the promising nature of these results suggests it would be worthwhile to pursue further research in this area with expanded samples.

Additionally, the use of a self-selected sample—participants volunteered to complete the questionnaire—may have introduced bias. Those who chose to participate might have had different motivations or expectations than those who did not. Future research should aim to control for self-selection effects to enhance internal validity.

It would also be beneficial to complement this quantitative approach with qualitative methods. Doing so would allow researchers to gain a more nuanced understanding of how resilience influences empowerment from the perspective of individuals living with reduced mobility.

5. Conclusions and Implications

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study contribute significantly to a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between resilience and empowerment. The results indicate that fostering specific resilience profiles could play a crucial role in enhancing empowerment, particularly among individuals with reduced mobility. By identifying the key characteristics and factors that support resilience in this population, this study opens new avenues for tailored interventions.

Moreover, these insights have practical implications for the development of policies, programs, and support services that aim not only to improve resilience but also to promote greater autonomy, participation, and overall quality of life. Strengthening resilience could serve as a foundational strategy in empowering individuals to better navigate daily challenges, reduce vulnerability, and increase their capacity to achieve personal goals.

Future research should explore these dynamics further, ideally through longitudinal and culturally diverse studies, to validate and expand upon these findings. In the meantime, practitioners and policymakers are encouraged to integrate resilience-building strategies into their approaches, ensuring they address both psychological and structural barriers faced by people with reduced mobility.