1. Introduction

There is a growing concern about the increase in polluting emissions gases due to their impact on human health, the environment, and the economy of affected or polluted regions. However, their implications are so extensive that it is challenging to accurately assess the effects of pollution (Lima et al., 2021). In this context, and given that it is a problem that cannot be ignored or left to future generations, it is essential to take action to minimize its impacts. One option for mitigating the emissions is the implementation or replacement of conventional fuels with cleaner alternatives, commonly referred to as environmentally friendly fuels or simply advanced fuels (Müller-langer et al., 2014). The Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO), also known as renewable diesel, green diesel, or paraffinic diesel, stands out as a clean and renewable alternative to replace fossil diesel fuel. Together with biodiesel, HVO represents one of the primary solutions for decarbonizing fleets equipped with CI engines, which are widely employed in heavy-duty transportation. These engines are significant contributors to urban pollution due to the high emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter (PM) associated with fossil diesel. It is also considered that until the imminent electrification of urban mobility, large vehicles will be more difficult to electrify and advanced renewable fuels are the best option.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA, 2023), the transport sector was responsible for approximately 23% of the global CO2 emissions in 2022, totaling 7.98 Gt, with road transport being the main contributor at around 75% of these total emissions, including both passenger and freight transport. This underscores the need to promote a cleaner vehicle fleet with lower environmental impact, adopting fuels that emit less Net CO2, such as biofuels, which have significant decarbonization potential for the transport sector. The adoption of sustainable fuels is a global concern, continuously highlighted in recent studies (Austin et al., 2022). To facilitate the comparison of the impacts of different pollutant gases, CO2 is often used as a standard, associated with factors that reflect the effects of each gas over a given period of time.

In Brazil, the vehicle fleet has experienced constant growth. According to data from National Traffic Secretariat (SENATRAN, 2024) -the institution responsible for providing in Brazil the national mobility statistics-, in January 2024, the fleet reached 119.55 million units across all categories. This growth intensifies the demand for cleaner, low-emission options. Recent legislation, offering tax incentives, is driving the production and adoption of biofuels in Brazil. It is therefore crucial to ensure that the vehicle fleet is adaptable to the use of a range of biofuels, fostering a diversified energy matrix that reduces dependency on a single fuel source.

This work investigates the environmental benefits of using HVO in internal combustion engines (ICE) in Brazil, particularly in relation to Net CO2 emissions, in comparison with other fuels in the Brazilian fuel matrix. In recent years, biodiesel has been the primary renewable substitute for fossil diesel. However, the advantages of HVO over conventional biodiesel have been widely discussed and demonstrated in the literature, and it is increasingly recognized as a promising alternative to reduce fossil diesel consumption and so do CO2 emissions. The CO2 emissions are examined from the Brazilian diesel vehicle fleet over the past 10 years, comparing fossil fuels, traditional biofuels, and the impending introduction of HVO into the Brazilian market. Various scenarios are modeled with the replacement of diesel by mixtures of HVO and biodiesel for use in CI engines. The triple blend consisted of fossil diesel, biodiesel, and HVO, with the HVO content gradually increased up to 50%, while the biodiesel blend remained fixed at the current concentration in Brazil (B13), progressively reducing the percentage of fossil diesel. To complement the study an economic analysis regarding the influence of future costs of HVO compared with conventional diesel is carried out.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Production and Properties of HVO

Over the years, countries around the world have made commitments to reduce greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions, aiming at mitigating the impacts of climate change. The first significant milestone was the Kyoto Protocol, signed in 1997, in which industrialized countries committed to mandatory emissions reduction targets. However, developing countries were excluded from these obligations, which led to criticism and challenges in securing their participation. The Conference of the Parties (COP) takes place annually, where countries party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) meet. For example, at COP26 in 2021, countries like India and Brazil committed to reaching carbon neutrality by 2070 and 2050, respectively. In 2015, the Paris Agreement was signed, which stipulates that countries must work to limit the global average temperature rise to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels. This means that the temperature increase should not exceed 2°C compared with temperatures recorded before the Industrial Revolution. The following sections review HVO properties, its comparison with diesel and biodiesel, its performance in ICE, and its role in emission reduction through biofuels, considering the life cycle.

HVO is a fuel obtained through the hydrogenation of vegetable oils, residual oils, or animal fats. It consists primarily of paraffinic hydrocarbons (C15 to C18), is free of sulfur, oxygen, and aromatics, and exhibits a high cetane number (EPE, 2020; ETIP BIOENERGY, 2020; Neste Corporation, 2020). HVO is recognized as a renewable fuel capable of partially or fully replacing fossil diesel in CI engines. Many studies highlight its potential to contribute significantly to the transformation of the transport sector energy matrix (EPE, 2020; NTU, 2019).

One of the main advantages of this fuel is its compatibility with existing CI engines (drop-in fuel), allowing its use without modifications. It can be employed either in its pure form or blended with conventional diesel and/or biodiesel. Additionally, it has been shown to deliver performance comparable to, or in some cases superior to, that of fossil diesel and biodiesel (No, 2014; Vignesh et al., 2021).

HVO is produced through hydrogenation and hydrocracking processes that convert vegetable oils and animal fats into a mixture of paraffinic hydrocarbons. These processes utilize high temperatures, high pressures, hydrogen, and catalysts (ETIP BIOENERGY, 2020). The main raw materials include canola, palm, soybean, and sunflower oils, as well as tall oil (a by-product of the Kraft process used in cellulose production), residual frying oils, and animal fats (Douvartzides et al., 2019; Soam & Hillman, 2019). HVO production typically begins with a pretreatment step to clean the raw material by removing contaminants and impurities (Hilbers et al., 2015; Pérez-Rangel et al., 2025). Next, the hydrogenation process saturates the double and triple bonds of the unsaturated triglycerides in the raw material. This is achieved through reactions with hydrogen under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions, aided by a catalyst, to produce diesel-like hydrocarbons (A. A. V. Julio et al., 2022; Sonthalia & Kumar, 2019). According to the IEA (2019), HVO was expected to represent the largest share of growth in advanced biofuel production by 2024, accounting for one-fifth of the anticipated expansion in biofuel production, highlighting its increasing importance in global biofuel markets. A key factor driving this growth is the ability of fossil fuel refineries to be converted for HVO production or to operate in tandem with fossil diesel production, thereby generating a co-processed product. This approach reduces investment costs and accelerates the deployment of new facilities (Cárdenas-Guerra et al., 2023; IEA, 2019; Lorenzi et al., 2020).

There are expectations that the production and commercialization of HVO in Brazil will begin in the coming years (de Souza et al., 2022), especially after ANP Resolution No. 842 of 2021, which includes hydrotreated vegetable oils in the group of fuels labeled as green diesel and establishes the requirements for their commercialization in Brazil (ANP, 2021). Petrobras has been conducting tests to evaluate the production of hydrotreated biofuels in Brazil, resulting in the formulation of Diesel R, a fuel that incorporates 5% to 10% renewable content in its composition (Pinto, 2025).

HVO is a paraffinic fuel with a chemical structure of CnH2n+2, which has a higher cetane number than both diesel and biodiesel. It is free of aromatics and sulfur, and its physicochemical properties are quite similar to those of fossil diesel (Aatola et al., 2008). HVO exhibits high oxidation stability, one of the main issues observed with biodiesel (Rangel et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2015). Additionally, HVO has a higher energy content (MJ/kg) than both diesel and biodiesel (Pechout et al., 2019). Another advantage of HVO over biodiesel is its lower viscosity, which results in better injection characteristics (Pinto et al., 2025; No, 2014).

The density of HVO is lower than that of fossil diesel and biodiesel, allowing it to be blended with heavier diesel oils while still meeting the specific mass limits set by regulations (Hartikka et al., 2012). The compressibility modulus of HVO is slightly lower than that of fossil diesel, which may result in a delayed injection timing compared with the latter (Boehman et al., 2004). However, this delay is less pronounced in newer engines equipped with common-rail injection systems (high injection pressure) (Tilli et al., 2009).

On the other hand, due to HVO high cetane number, its combustion ignition is advanced at low and medium loads, while at higher loads, there are no significant differences compared with fossil diesel combustion (Millo et al., 2025). Moreover, it has been observed that operating with HVO results in lower noise and smoke compared with fossil diesel (Hartikka et al., 2012).

Table 1 presents a comparison between the three fuels proposed to dominate the Brazilian diesel matrix in the coming years regarding urban mobility.

2.3. Emissions in Internal Combustion Engines

HVO is a fuel that presents several environmental benefits when compared with fossil diesel (Cremonez et al., 2021; de Souza et al., 2022; Pinto et al., 2023b; Sonthalia & Kumar, 2019). Its combustion results in lower emissions of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HC), and nitrogen oxides (NOx) (Bortel et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2015; Sonthalia & Kumar, 2019), as well as a notable decrease in particulate matter (PM) emissions, as its aromatic-free composition prevents the development of this pollutant (McCaffery et al., 2022; Vignesh et al., 2021). Furthermore, it exhibits lower net CO2 emissions (Bortel et al., 2019; da Costa et al., 2022), making it capable of significantly reducing the carbon footprint associated with its use when compared with fossil diesel (Götz et al., 2016; Roque et al., 2023).

Hartikka et al. (2012) observed that the use of pure HVO in heavy-duty engines allows for reductions in NOx, PM, CO, and HC emissions. Similar results were observed when HVO was used in passenger vehicles. In terms of spray characteristics, the authors stated that there are no significant differences between HVO and fossil diesel, and that despite the lower density of HVO, its operation does not lead to any loss of power. Finally, the authors concluded that operating with HVO results in similar energy efficiencies compared with commercial diesel.

Pechout et al. (2019) and Kim et al. (2014) conducted a study comparing the use of HVO, biodiesel, and diesel in a passenger vehicle equipped with a four-cylinder CI engine. The authors observed that HVO exhibited a shorter ignition delay compared with the other fuels, resulting in better combustion development. The authors reported that HVO offers considerable advantages over both biodiesel and fossil diesel.

Singh et al. (2015) investigated the use of HVO in a six-cylinder engine, comparing performance and emission results with those obtained during operation with pure diesel and biodiesel. The authors observed a significant reduction in PM, HC, and CO emissions when using HVO compared with diesel. They attribute this to the absence of sulfur and mainly aromatics in the composition of this biofuel and a possible improvement in combustion associated with its higher cetane number. Finally, the authors noted a reduction in specific fuel consumption on a mass basis, associated with HVO higher heating value compared with diesel and biodiesel. They concluded that HVO is a promising biofuel with significant potential to replace biodiesel.

On the other hand, Pinto et al. (2025) showed that the NOx emissions obtained in compression engine tests during operation in conventional mode with fossil diesel and with HVO, there is an average reduction of 6.63% in specific NOx emissions by replacing fossil fuel with renewable fuel. The authors commented that this is probably due to the higher cetane number which ended up reducing the ignition delay time.

The effects of using a triple blend of HVO, biodiesel from used cooking oil (UCO) and fossil diesel were experimentally studied by Götz et al., (2016). The blend was called Diesel R33 by the authors. For this study, five different passenger vehicles were used and, in addition to Diesel R33, tests with commercial European diesel (containing 5% biodiesel, at the time of the studies) were carried out as comparisons. The authors observed that Diesel R33 was able to reduce HC emissions (on average 26%) and CO emissions (on average 38%) compared with fossil diesel, attributing this to the better ignition characteristics of Diesel R33, especially due to its higher cetane number. Conversely, an increase in NOx emissions was observed when the vehicles operated on Diesel R33, while PM emissions were similar for both fuels. In an analysis of well-to-wheel CO2 emissions, the authors indicated that Diesel R33 is capable of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by about 18.2% compared with fossil diesel.

One drawback of HVO noted by some authors (Arguelles-Arguelles et al., 2021; No, 2014) is its poor performance at low temperatures, which may necessitate the use of additives or an isomerization process during production to enhance its properties in cold climates (Hartikka et al., 2012; Lapuerta et al., 2011). Another disadvantage is HVO low lubricity due to the absence of aromatics, also requiring the addition of lubricating additives (Lapuerta et al., 2011; Puricelli et al., 2021).

2.4. Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) with HVO

Biofuels derived from biomass contribute to CO2 reduction in the atmosphere by integrating into a rapid and renewable biological carbon cycle. Unlike fossil fuels, whose combustion releases carbon stored in the Earth's crust for millions of years, biofuels offset their CO2 emissions through the capture of the same gas during the growth of the plants used as raw materials. In this cycle, the CO2 released by burning biofuels is reabsorbed by plants through photosynthesis, reducing carbon accumulation in the atmosphere and consequently mitigating climate impact (Coronado et al., 2009; Sheehan et al., 1998).

One of the earliest evaluations of biodiesel was the life cycle analysis (LCA) by Sheehan et al. (1998), partially funded by the U.S. government to assess the potential benefits of biodiesel implementation in vehicle fleets. The study concluded that biodiesel reduces net CO2 emissions by 78.45% compared with petroleum-based diesel.

Kalnes et al. (2009), when comparing HVO with petroleum diesel, reported fossil emission savings ranging from 66% to 84% and greenhouse gas emission reductions between 41% and 85%.

Permpool & Gheewala (2017) conducted an LCA of three biofuels using palm seed oil as feedstock for biodiesel, partially hydrotreated biodiesel (H-FAME), and HVO. The approach used was well-to-wheels (WTW), contextualized in Thailand, one of the world largest palm oil producers. The authors found greenhouse gas emission reductions of 67% for biodiesel, 65% for H-FAME, and 70% for HVO compared with petroleum diesel. They also highlighted that, in the case of petroleum diesel, the highest emissions occur during combustion, whereas for biofuels the emissions are mainly associated with the plantation stage.

Xu et al. (2020) in their LCA study of palm oil HVO, found that it can reduce GHG emissions by 66.9% to 85.4% compared with fossil diesel. Xu et al. (2022), also conducted an LCA, analyzing various feedstocks, including plant, animal, and residual sources, for the production of biodiesel and renewable diesel, comparing them to fossil diesel. Using the GREET model and a WTW approach, the authors assessed CO2 equivalent emissions with and without including land use change (LUC) emissions. The results showed that LUC has a significant impact on the total emissions of biofuels from oilseed crops. Without LUC emissions, reductions ranged from 63% to 77% for biodiesel and renewable diesel compared with fossil diesel; when LUC emissions were included, these reductions dropped to 42%–67%, depending on the reference used for calculating LUC. Biofuels such as biodiesel and renewable diesel from residual or animal sources showed significant GHG emission reductions, ranging from 79% to 86% compared with petroleum diesel.

Arguelles-Arguelles et al. (2021) analyzed the production of HVO from palm oil by conducting a LCA in the “cradle-to-grave” mode, excluding LUC emissions. The authors found CO2 reductions of up to 108.3% when comparing the results obtained with bibliographic data on emissions from fossil diesel processing. However, the experimentally produced HVO did not meet the Mexican standard for cold flow properties. To overcome this limitation, the authors recommend a blend of 25% HVO and 75% Mexican ultra-low sulfur diesel, which ensures compliance with cold flow requirements and allows for up to a 27% reduction in emissions compared to fossil diesel.

A widely recognized study in Europe is the JEC Well-To-Wheels Report v5 (JRC, 2020), which addresses the LCA of different vehicles. This study was conducted in collaboration by experts from the JRC (Joint Research Centre of the European Commission), EUCAR (European Council for Automotive R&D), and Concawe (Conservation of Clean Air and Water in Europe).

Table 2 illustrates the reduction in carbon equivalent emissions depending on the type of fuel used, considering three categories of vehicles: passenger cars, heavy duty type 4, and type 5. The CO₂eq reduction values depend significantly on the source of the feedstock, as well as the adoption of optimized practices in the biofuel production process, such as heat recovery, methane recovery, among others.

2.5. HVO Cost and Future Trends

The cost of HVO is expected to decline relative to fossil diesel in the upcoming years due to several factors. Advances in HVO production technology and its increasing industrial acceptance, along with governmental policies that incentivize environmentally friendly fuels while penalizing fossil fuel consumption, contribute to this trend. Julio (2020) analyzed the production of aeronautical biofuels from palm oil, emphasizing that plants with optimized processes and cogeneration throughout the production chain achieve significant cost reductions. In his study, HVO produced as a byproduct of Alcohol to Jet (ATJ) and Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids (HEFA) had a production cost of 0.2 USD/L, up to four times lower than that of biodiesel in the Brazilian market. This low cost is attributed to HVO being an excess output rather than the primary product, with its pricing reflecting cost allocation strategies that differ from standalone HVO production facilities.

Martinez-Hernandez et al. (2019) assessed the profitability of HVO using Monte Carlo simulations, determining that a plant with a capacity of 63,000 bbl/y year requires a minimum selling price (MSP) of 1 USD/L to mitigate financial risks. Feedstock costs represent the largest share of production expenses, and the MSP varies with production scale and crude oil prices. For plants with capacities ≥63,000 bbl/y, the MSP decreases to 0.92 USD/L (for these conditions subsidies are not necessary to reduce the price of HVO), enabling competition with fossil diesel in Mexico (0.95 USD/L). The authors concluded that renewable diesel production is more economically viable than biojet fuel production.

Glisic et al. (2016) simulated the production of HVO, conventional biodiesel, and biodiesel under supercritical conditions (300°C, 20MPa), estimating an HVO production cost of 0.631 USD/L. To lower production costs, authors used waste vegetable oil as feedstock. Economic viability improves when HVO production is integrated into an oil refinery rather than operating as a standalone unit. For plants with capacities below 100,000 t/y, the net present value (NPV) after 10 years is negative, whereas at scales ≥200,000 t/y, catalytic hydroprocessing becomes economically viable. Consistent with other studies, HVO profitability is highly sensitive to feedstock costs and production scale.

Lorenzi et al. (2020) investigated HVO production from UCO in an HDT plant with a capacity of 100,000 t/y, using high-temperature electrolysis cells (SOECs) as a hydrogen source. The levelized cost of fuel (LCOF) was estimated at approximately 0.79 USD/L for a non-integrated UCO hydrogenation unit. Reducing the income tax rate to 10% increased the average NPV by 37%, the authors suggest that tax incentives enhance HVO competitiveness. Economic analysis also indicates that the plant would reach the break-even point in less than four years under baseline conditions.

According to Brown et al. (2020), the production cost of HVO is primarily influenced by raw material expenses, which account for 65% to 80% of the total. Given the limited availability of sustainable feedstocks and increasing demand, costs are expected to rise or remain volatile. The authors considered that HVO technology is already well established, therefore significant cost reductions in the medium term are unlikely. Currently, production costs range from 51 to 91 €/MWh, with estimates suggesting that a reduction in capital costs could lower the minimum to 50 €/MWh, while the maximum could decrease to 88 €/MWh, representing 0.55 USD/L and 0.97 USD/L respectively. In the short term, prices are likely to remain high due to constraints in raw material supply. In the medium to long term, regulatory policies and greater integration of the production chain may help stabilize or reduce costs. In Brazil, RenovaBio could enhance HVO competitiveness by promoting the trade of Decarbonization Credits (CBIOs), contributing to price stabilization.

Over the past three years, the production price of HVO has decreased significantly. In January 2022, HVO in the Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp (ARA) region was priced at 2.88K USD/t, peaking at 3.53K USD/t in June of the same year, and dropping to 1.8K USD/t in February 2025. Similarly in California, the price of HVO from used cooking oil (UCO) was 0.770 USD/gal in January 2022, rising to 0.943 USD/gal in June, and reaching 0.457 USD/gal by February 2025. These changes represent a reduction of approximately 42% to 37% in HVO prices between 2022 and 2025 in ARA and California, respectively (Argus, 2025 apud Neste, 2025). The reduction in HVO production costs enhances its competitiveness compared with fossil diesel and biodiesel, offering a more economically viable and sustainable alternative, thus promoting its growing adoption in the market. This price decline is in line with market growth projections, which forecast a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.95% through 2030 and 26.8% between 2025 and 2034. Sources such as Fortune, (2023) and Market Research Future (2025) forecast significant market growth, driven primarily by government incentives, technological advancements, and the increasing demand for renewable fuels.

Available projections for the next 20 years indicate that the price of HVO could range from 0.55 USD/L to 0.92 USD/L. Lower costs are associated with processes integrated into fossil fuel refining and larger-scale production facilities, which benefit from economies of scale and increased operational efficiency. The data in

Table 3 presents the production costs of HVO are influenced by different feedstocks, production capacities, and economic considerations, reflecting the findings discussed above.

3. Methodology

The emission factors for CO2 were calculated for the fuels commonly used in the Brazilian market, including HVO and biodiesel (both pure and blended with commercial diesel). Next, the average CO2 emissions per automobile per year were computed for these fuels. Using data reported by SENATRAN (2024), the CO2 emissions of the diesel vehicle fleet in Brazil and the associated reductions when using HVO and biodiesel (either pure or blended) were determined. Projections for the CO2 emissions of automotive vehicles in Brazil were made for 2030 and 2035. The emission results from these two fuels will be discussed and integrated into future scenario projections. Based on the reviewed literature, and considering an average in net CO2 reductions with the use of HVO, this paper will adopt a 75% reduction in net CO2 emissions compared to fossil diesel, considering the LCA of HVO produced from UCO and the WTW methodologies widely used in the studies reviewed in section 2.4.

The average molecular weight of soybean oil methyl ester, HVO and diesel was assumed to be 292.2, 198 e 170 g/gmol, respectively.

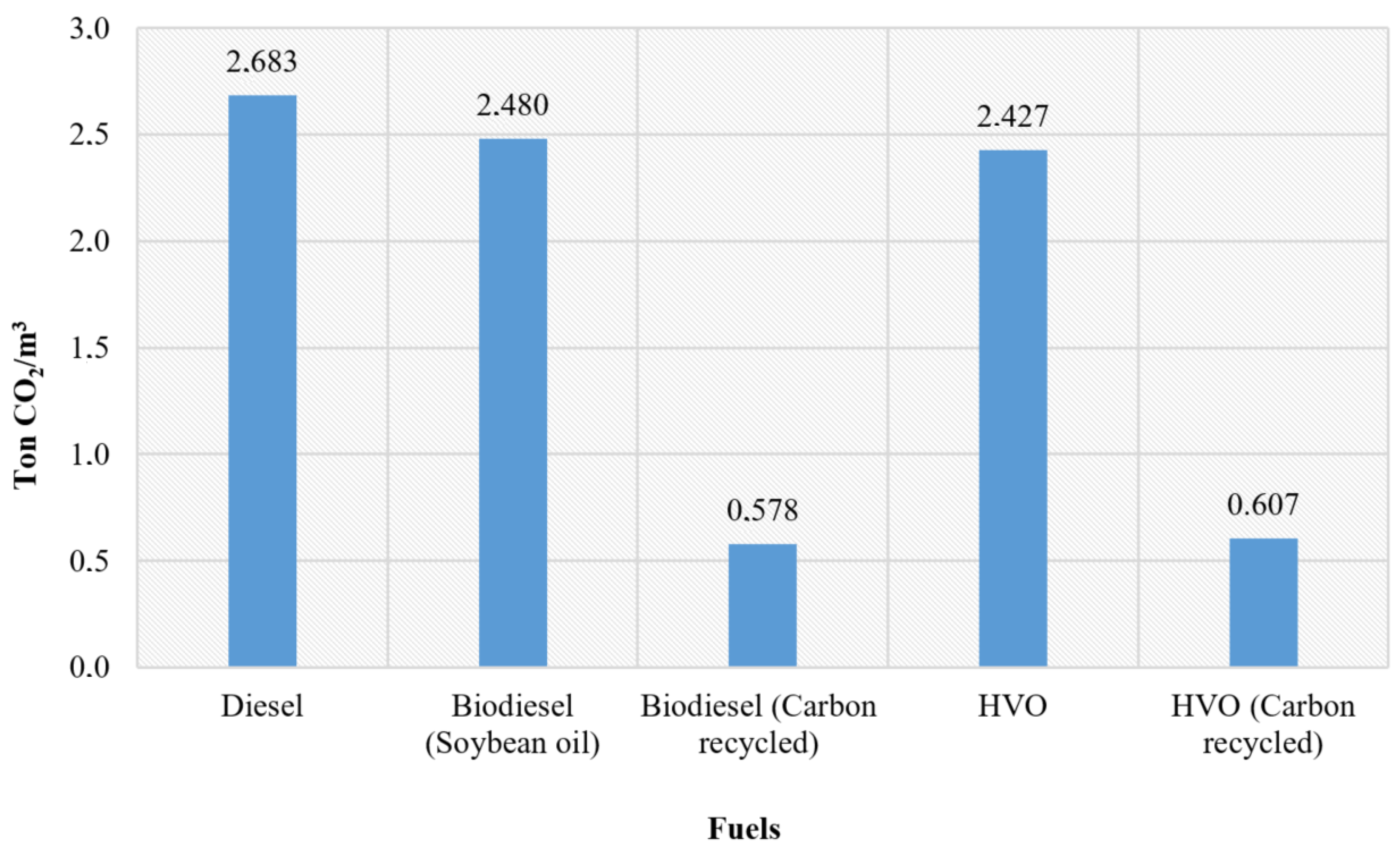

Thus, carrying out a direct combustion, starting with fossil Diesel (C12H26) with a density of 0.864 ton/m3, from a stoichiometric reaction, there would be 528 tons of CO2 for 196.76 (170/0.864) m3 of Diesel, which would emit 2,683 tons of CO2/m3. On the other hand, HVO (C14H30) with a density of 0.78 ton/m3, following the same calculation as Diesel and also for a stoichiometric reaction, would emit 2,427 tons of CO2/m3. Finally, considering Biodiesel from soybean oil, whose chemical formulation is well known and with a density of 0.9679 ton/m3, it would emit 2.48 tons of CO2/m3. Thus, it can be observed that the three fuels emit similar amounts of CO2 even though the last two have a renewable origin.

For B100 (pure biodiesel), Sheehan et al. (1998), one of the main references regarding life cycle analysis of biofuels, with regard to the reduction of net CO2 emissions, estimate a 78.45% reduction in CO2 emissions compared with diesel. Regarding HVO, based on the literature reviewed in section 2.4 (which considers the closed carbon cycle and LCA studies), this article adopts a reduction of 75%.

Therefore, considering the environmental benefit, due to the absorption of CO2 by the fields of crops of the raw material of renewable origin of both HVO and Biodiesel, the CO2 emitted in the exhaust of motor vehicles, considering the percentages to be reduced by the life cycle analyses mentioned (75% for HVO and 78.45% for Biodiesel), HVO would emit 0.607 tons of CO2/ m3 and biodiesel would emit 0.578 tons of CO2/m3.

4. Results

4.1. CO2 LCA Emissions

Figure 1 summarizes the CO

2 emissions by fuel type already considering the reduction in net CO

2 emissions over the life cycle of both fuels.

Regarding annual Net CO

2 emissions, it was estimated that each diesel vehicle covers an average of 100,000 km per year (U.S. Department of Energy, 2021), with a fuel consumption rate of 5 km/L (ANP, 2023). Combining these data with stoichiometric calculations, each vehicle consuming fossil diesel emits 53,670 tons of CO

2 annually.

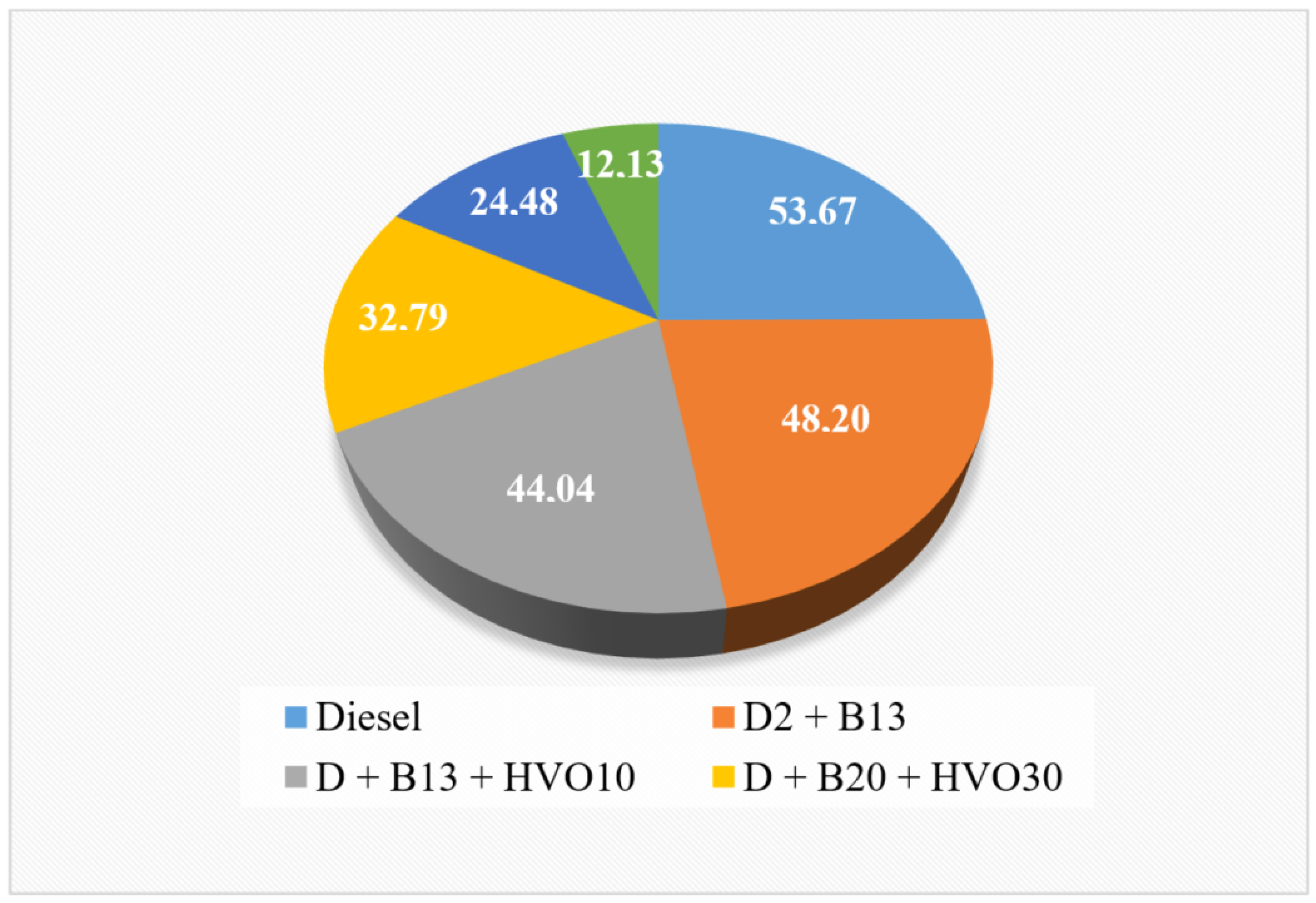

Figure 2 presents Net CO

2 emissions in tons/year for the diesel substitute fuels (blends). For calculations involving biodiesel (B100) and HVO, emission reductions of 78.45% and 75%, respectively, were applied due to the closed carbon cycle effect, as discussed in previous sections.

4.2. Net CO2 emissions from Brazilian diesel fleets

As an example, the cumulative number of diesel vehicles over the last ten years in Brazil is 1,210,990, based on data from January 2015 and January 2025 (SENATRAN, 2025). In Brazil, CI engines are only permitted in specific types of vehicles, including buses, minibuses, trucks, tractor-trucks, and pickup trucks with a load capacity exceeding 1 ton. Additionally, only utility vehicles with 4×4 traction or an ultra-short first gear are allowed. For the purposes of this paper, the Brazilian diesel fleet is assumed to include only trucks, tractor-trucks, minibuses, and buses.

Considering that the Brazilian diesel fleet (1,210,990) covers an average of 100,000 km/year (U.S. Department of Energy, 2021) with a fuel consumption of 5 km/l for fossil diesel fleets (ANP, 2023) as already pointed out in the previous section,, CO2 emissions would amount to 639.383 Mton of direct CO2 over ten years. Alternatively, this study proposes blending fossil diesel with HVO and biodiesel in various proportions, considering the following combinations. The blends are arbitrary and proposed for this study considering a decrease in the use of fossil diesel and an increase in the use of HVO for the coming years in Brazil, maintaining the biodiesel blend at a maximum of 20%.

D + B13 (13% biodiesel in fossil diesel (D))

D + B13 + HVO10 (13% biodiesel + 10% HVO in fossil diesel)

D + B20 + HVO30 (20% biodiesel + 30% HVO in fossil diesel)

D + B20 + HVO50 (20% biodiesel + 50% HVO in fossil diesel)

Significant reductions in CO

2 emissions, considering the carbon life cycle, i.e. Net CO

2, are observed under these blend scenarios.

Figure 3 compares Net CO

2 emissions in tons and the percentage reduction achieved when using 100% fossil diesel versus blends with HVO and biodiesel, based on data from the last ten years in Brazil. The results demonstrate a clear decline in Net CO

2 emissions as the share of HVO and biodiesel in the blend increases.

Since the introduction of biodiesel in Brazil in 2004, with a mandatory 2% blend in fossil diesel, significant environmental benefits have been observed from the increasing adoption of this substitute fuel. However, with the emergence of HVO as a promising diesel alternative, a remarkable opportunity now exists to further increase the share of renewable components in fossil diesel. Moreover, researchers have highlighted potential challenges associated with increasing the current biodiesel blend beyond 13% in fossil diesel. These issues, however, could be mitigated by incorporating HVO. Due to the advantageous physicochemical properties of HVO, as discussed in previous sections, higher biodiesel proportions in the blend could achieve greater stability and performance.

4.3. Future Projections

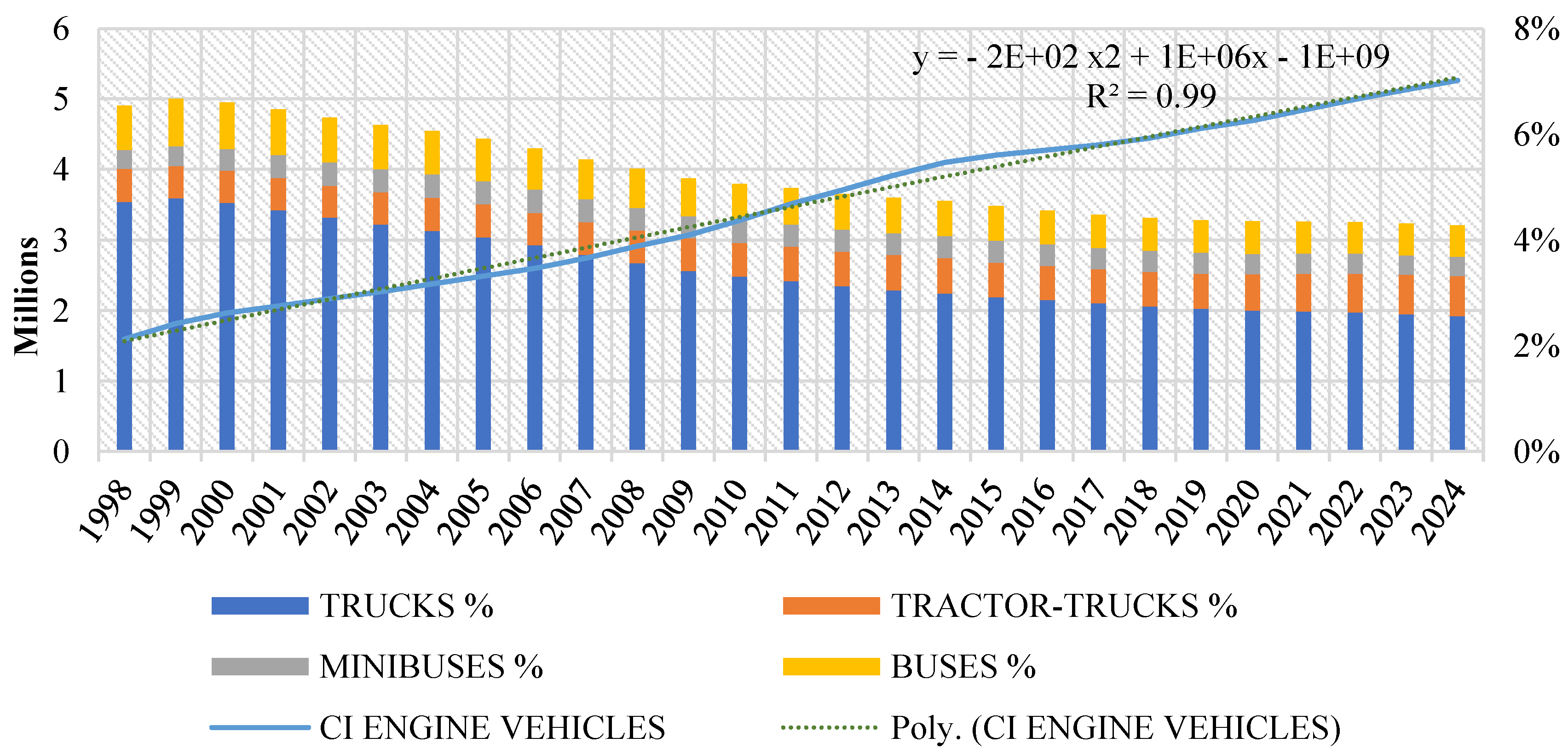

Figure 4 shows the evolution of diesel vehicles in Brazil over the past 26 years, categorized by type. The percentage share of diesel vehicles within the total fleet has declined since 1999. However, their total count, which includes trucks, truck tractors, minibuses, and buses, has more than tripled, from approximately 1.59 million in 1998 to nearly 5.27 million as of mid-2024 (SENATRAN, 2024).

Based on data collected from the website of the SENATRAN (2024), a trend function was developed using historical data from the vehicle fleet over the past 26 years. This function allows for projections of the share of diesel vehicles in the coming years. A second-degree polynomial trendline, with a high coefficient of determination (R² = 0.99), was applied to describe the behavior of the dataset. The resulting equation is:

According to this equation, Brazil diesel vehicle fleet is estimated to reach approximately 6.13 million units by 2030, potentially increasing to around 6.8 million units by 2035.

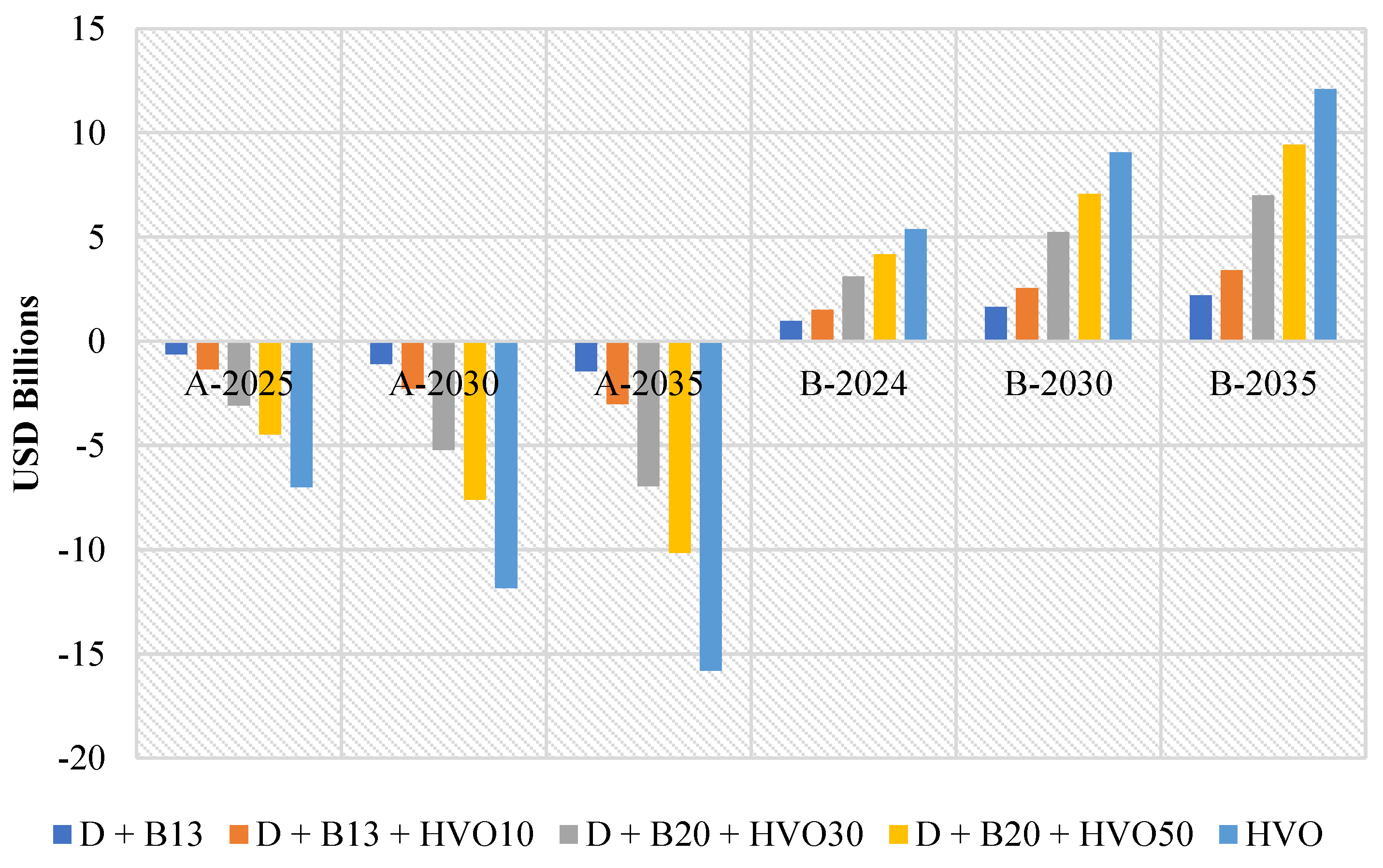

As mentioned in section 2.5, the production cost of HVO could range from 0.55 USD/L to 0.97 USD/L over the next 20 years, with lower costs associated with processes integrated into fossil fuel refining and larger-scale plants. To estimate the projected costs of fossil diesel, HVO and biodiesel blends until 2035, two scenarios were considered, in which the costs of the previously analyzed blends D+B13, D+B13+HVO10, and D+B20+HVO30 were evaluated. The first, referred to as 'Scenario A', projects the future costs of the blends, with prices based on the historical average of each fuel. 'Scenario B', representing an optimistic scenario, estimates the future prices of HVO based on the forecast of a potential cost reduction.

Scenario A, The HVO price of 1.11 USD/L was considered for scenario calculations, based on medium retail prices data from California state U.S since January 2017. Additionally, the influence of marketing prices in other tree states, where HVO is also commercialized, was accounted for $0.011 USD/L reduction (U.S. Department of Energy, 2024). For the value of biodiesel and fossil diesel, the average commercialization values in the United States were considered, in the same period of time as HVO.

Scenario B, represents a more favorable projection regarding the reduction in HVO prices. A minimum HVO sales price of 0.92 USD/L was considered, based on the calculations by Martinez-Hernandez et al. (2019). The fossil diesel price was set at 1.15 USD/L, reflecting the average price in California (U.S. Department of Energy, 2024), the state with the most stringent atmospheric emissions policies, whose regulations often influence national environmental policies. The biodiesel price was set at 0.83 USD/L, the projected minimum future value according to Brown et al., (2020).

The values of the Brazilian vehicle fleet were considered according to Eq. 1 for the years 2030 and 2035, taking into account the accumulation of the fleet since 2015, based on data from (SENATRAN, 2024) and according to fuel consumption calculated for this fleet.

It should be noted that international cost data for fossil diesel and HVO were used, and not the cost in Brazil, because HVO in Brazil, despite already having regulations, is not yet used and sold 100% at gas stations, so the price may not be correct for a forecast for the next 20 years. On the other hand, it is expected that in the next 20 years the price of fossil diesel will increase not because of the costs associated with its production, but because of environmental fines and incentives to stop selling this fossil fuel. However, in this analysis, to avoid any speculation, the price of diesel was kept fixed for the next few years.

Figure 5 presents the results for Scenarios A and B, illustrating the financial impact of replacing fossil diesel with HVO and biodiesel, expressed in billions of dollars. Negative values represent additional costs incurred due to the replacement, while positive values indicate cost savings. The zero line represents the cost of fossil diesel.

In Scenario A, where HVO prices remain high (1.11 USD/L), the transition is not economically viable, leading to increasing additional costs over time, with costs reaching 15.80 USD billion by 2035 for a complete replacement of fossil diesel with HVO. In contrast, Scenario B, which assumes a reduction in HVO costs (0.92 USD/L), presents a more favorable projection, with positive values for all blends and pure HVO, indicating economic feasibility. In this scenario, the full replacement of fossil diesel with HVO could generate savings of 12.11 USD billion by 2035, reinforcing the importance of reducing production costs and adopting policy incentives to support the transition to this renewable fuel.

The results underscore the sensitivity of the economic viability of the transition to the price of HVO, suggesting that with price reductions and potential government incentives, biofuel adoption could become economically advantageous in the long term. Technological innovations will also be critical to reducing HVO production costs and enhancing its market competitiveness.

The expansion of the HVO production chain would involve sectors such as agribusiness, vegetable oil and waste collection, and distribution infrastructure. As demand rises, investments will be directed toward these sectors, generating employment opportunities and stimulating the local economy. Furthermore, a larger market share for HVO could enhance the issuance of carbon credits, thereby strengthening the carbon market and providing additional revenue streams for biofuel producers.

For transportation and logistics companies, adopting HVO could lower operational costs, subsequently reducing the final price of products and services, which benefits consumers. In Brazil, where road transport accounts for over 60% of cargo movement, replacing fossil diesel with HVO could provide significant economic and environmental benefits. Since fuel expenses can account for up to 47% of operating costs on long-distance trips (ILOS, 2023)(Victor, 2022), a more cost-efficient fuel alternative would enhance logistical competitiveness by reducing sector expenditures.

5. Conclusion

The use of HVO in CI engines effectively reduces net CO2 emissions, playing a crucial role in minimizing greenhouse gases that harm human health and the environment. As a "green" fuel, HVO early adoption has the potential to prevent pollutant emissions from diesel vehicles. In the heavy-duty transportation sector, HVO is rapidly gaining support for many investors as it will play an integral role in decarbonization efforts. This study does not aim to discourage biodiesel use; rather, it seeks to encourage and demonstrate that biodiesel + HVO blends, with increasingly higher proportions in fossil diesel, clearly present environmental benefits by reducing CO2 emissions from Brazil diesel fleet.

Considering the reduction by Net CO2 emissions of both HVO and biodiesel, remarkable differences were revealed: pure HVO resulted in 12.13 tons of CO2 per year, while a blend of 50% HVO, 20% biodiesel, and 30% diesel emitted 24.48 tons per year. In contrast, the use of petroleum diesel alone resulted in 53.67 tons of CO2 per year, illustrating significant potential for emission reduction with HVO-based fuels.

Considering the Brazilian diesel fleet of the last ten years (2015-2025), running entirely on 100% HVO could have reduced CO2 emissions by 77.4%. Similarly, using the 50% HVO blend could have achieved a 54.4% reduction.

Projections indicate significant CO2 emissions from the Brazilian diesel fleet, only burning fossil diesel, with estimates of 1,621.53 Mton by 2030 and 2,885.99 Mton by 2035. However, a full transition to HVO could reduce these figures to 366.58 million and 652.44 Mton, respectively. In addition to its environmental benefits, HVO adoption could generate substantial economic advantages. In Brazil, replacing Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel with HVO in the diesel fleet could lower fuel expenditures by up to 12.11 USD billion by 2035 under the scenario B. However, in the projected maximum price scenario A, costs could increase by up to 15.80 USD billion. Given that fuel costs account for nearly half of operating expenses in long-distance cargo transport, adopting HVO could improve logistical competitiveness while contributing to decarbonization efforts.