Introduction

Over the past decade, there has been a significant increase in the number of studies that have examined the cognitive and emotional factors that contribute to learning in higher education (Vermunt & Donche, 2017). Contemporary studies in higher education emphasize a number of emotional factors that either facilitate or hinder student learning (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2020; Rentzios & Karagiannopoulou, 2021).

Motivation and emotions are crucial in learning and performance (Kim & Pekrun, 2014). While some scholars (Hannula, 2006) view emotions as a component of motivation processes, others (Op't Eynde et al., 2006) view motivation as a component of emotion processes. Consequently, motivation and emotion are regarded as two facets of the same process (Kim & Pekrun, 2014). Thus, an integrative perspective on motivation and emotions is required to facilitate learning and performance (Kim & Hodges, 2012; Miele et al., 2024).

Moreover, given that both positive and negative emotions students encounter in demanding settings, such as universities, may promote and/or hinder performance, it is reasonable for university students to attempt to regulate them (Harley et al., 2019). Literature suggests that academic emotions and emotion regulation strategies should be examined in tandem in order to elucidate the complexity and nuances of emotion regulation in achievement contexts (Harley et al., 2019). In particular, Harley et al. (2019) propose that various emotion regulation strategies can be implemented and integrated to manage emotions effectively in learning and educational contexts (Frenzel et al., 2024; Harley et al., 2019).

The present study employs a person-centered approach to acquire a deeper comprehension of student profiles, especially considering recent research that highlights an increase in dissonant profiles in educational environments (Parpala et al., 2022). This method provides a chance to explore the distinct characteristics of various student groups and their impact on learning behavior and their academic performance. The simultaneous presence of these characteristics, namely, academic emotions, emotion regulation strategies, types of academic motivation and approaches to learning, has not been previously examined by profile, leading us to investigate this connection further. Most studies in the educational field examine students’ profiles focusing mainly on emotional (Robinson et al., 2017) or cognitive factors (Lonka et al., 2021; Tuononen et al., 2023); here, we propose a combination of both of them adding the motivation facet. A person-centered approach has the potential to enhance our understanding of the complexities of intersecting components, therefore providing new insights into the interaction regarding emotional factors and learning (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2020; Milienos et al., 2021). Koenka (2020) suggests that using new data-analysis tools (e.g. person-centered approach) facilitates the detection of significant processes in learning. Moreover, in order to justify and enhance the extracted profiles we consider the grade point average (GPA) as an outcome of these profiles to identify if any differences exist regarding their scores.

The current study attempts to explore the joint co-occurrence of these crucial components of the learning process. That is, emotion regulation strategies (reappraisal and suppression), academic emotions (enjoyment, anxiety and boredom), academic motivation-regulation (external, introjection, identification and intrinsic) and approaches to learning (deep, surface and organized).

Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation (ER) is the explicit or implicit attempts individuals engage to affect the feelings they experience, the timing of these emotions, and their expression and perception of them (Gross, 2015). A considerable amount of research has concentrated on cognitive reappraisal and suppression. Reappraisal comprises recontextualizing a situation to modify one's emotional reaction, whereas suppression involves restraining the external manifestation of emotion (McRae & Gross, 2020). Reappraisal is frequently seen as adaptive, whereas suppression is considered maladaptive. Recent evidence, however, suggests that the context in which the emotion arises is critical (Rottweiler et al., 2018). In educational setting for example, suppression has been associated with beneficial outcomes in learning environment (Webster & Hadwin, 2015). Moreover, the consistent use of reappraisal has been demonstrated to correlate with increased positive emotions, reduced negative emotions during learning, increased motivation associated with learning, and improved self-regulation of learning, hence facilitating deeper knowledge acquisition and academic achievement (Losenno et al., 2020; Spann et al., 2019).

Furthermore, students seldom deployed reappraisal, reflecting Suri et al.’s (2015) conclusion that this approach is implemented less frequently than anticipated, despite its adaptiveness. Indeed, reappraisal may be highly demanding, particularly during situations of extreme stress. Consequently, it may not be beneficial in performance-focused contexts such as tests, which inherently place significant cognitive demands on students (Frenzel et al., 2024). While reappraisal is predominantly seen as a cognitive regulation skill, it is conceivable that developmental alterations in these social processes lead to an increased frequency of reappraisal throughout development (McRae et al., 2012). The capacity for emotion regulation is linked to the activation of specific prefrontal brain regions that are crucial to cognitive control and executive functioning, which emerge later in the maturation process (Martin et al., 2016). On the other hand, suppressing emotions denotes a highly regulated kind of emotion regulation in which individuals deny and downplay the intensity and significance of their feelings regarding oneself (Kim & Pekrun, 2014; Roth et al., 2019). Along with this experiencing suppression, individuals feel forced to conceal their negative emotions towards others, therefore inhibiting emotional expression (Roth et al., 2019). In general, reappraisal is more commonly utilized when emotional intensity is moderate, whereas suppression is employed when intensity is high (McRae & Gross, 2020).

According to Self Determination Theory (SDT) the way individuals regulate their emotions is related to different types of motivation: e.g., autonomous motivation or controlled motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Academic Motivation

SDT is a macromotivational theoretical framework that focuses on the traditional distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and it has been extensively utilized in educational research (Ryan & Deci, 2020). SDT posits that the form of motivation among university students influences the extent of energy they may apply to learning and managing academic challenges (Ryan & Deci, 2020; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006). To determine the quality of students’ motivation, SDT distinguishes between two forms: autonomous and controlled motivation. When students are driven by autonomous motivation, they experience a sense of volition and their reasons for studying are perceived as self-directed and self-endorsed. When autonomously motivated, students find the learning material to be interesting and enjoyable (intrinsic motivation) or personally valuable and meaningful (identified regulation). Intrinsic motivation reflects the most optimal type of motivation, as it is fully autonomous and self-determined (Vansteenkiste et al., 2009). Most studies suggest that higher levels of identified and intrinsic motivation are associated with a number of positive outcomes, such as more positive emotions, better self-concept and optimal academic achievement (Sutter-Brandenberger et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2014). In fact, these two forms of motivation are also in positive relation with the use of deep learning strategies (Pekrun, 2013). In contrast, controlled motivation refers to behavior that is driven by pressure to behave in a certain way. With controlled motivation, students experience their study efforts as stemming from internal forms of pressure such as feelings of guilt, shame or anxiety or the striving for contingent self-approval, and pride (introjected regulation) or from externally pressuring forces, such as high environmental demands or expectations, the threat of punishments, or the promise of rewards (external regulation; Koole et al., 2019; Ryan & Deci, 2017). In the case of more controlled forms of motivation (external and introjected regulation) the results lack clarity. For example, introjection is related positively to behavioral engagement yet negatively to emotional engagement and predicts the use of more superficial learning strategies, procrastination and test anxiety (Boncquet et al., 2024; Van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2016). We should consider that controlled motivation is not necessarily incompatible to autonomous motivation. It can exist alongside autonomous motivation, as seen in students who exhibit a high level of overall motivation (Vansteenkiste et al., 2009). Controlled motivation presents a somewhat paradoxical impact on students' learning. While it may yield certain short-term benefits, particularly when it serves as the primary driving force behind university students' efforts, it ultimately leads to lower-quality learning outcomes compared to autonomous motivation (Boncquet et al., 2024). To sum up, a large number of studies have shown that these distinct forms of academic motivation are related to students’ learning behaviour and academic achievement (Vansteenkiste et al., 2022).

Motivation and academic emotions are also correlated and studied in educational literature (Kim & Pekrun, 2012). In fact, the relative research on these constructs has been developed almost completely independently, although there is a consensus that motivation and emotions are strongly related within the educational environment (Pekrun. 2013; Sutter-Brandenberger et al., 2018). Only a few studies have examined academic emotions within the framework of SDT, and these have primarily focused on educational levels other than higher education (Sutter-Brandenberger et al., 2018) or on adults outside the education context (Vandercammen et al., 2013).

Academic Emotions

Academic emotions refer to emotions that arise during learning and achievement situations, including discrete emotions such as enjoyment, anxiety and boredom (Pekrun et al., 2011). These emotions are in the core of Pekrun’s Control Value Theory (CVT; Pekrun, 2018), who argues that they could directly affect students’ achievement through motivational mechanisms, self-regulation and learning strategies (Pekrun, 2006).

Academic emotions can be elicited during different academic settings such as attending a classroom (classroom-related emotions), during learning (learning-related emotions) and taking exams (exams-related emotions) (Pekrun, 2006). Three emotions are most frequently experienced in Higher Education, namely, enjoyment (positive, activating), anxiety (negative, activating) and boredom (negative, deactivating) during learning. The reasons for selecting these emotions are twofold. Firstly, these emotions are frequently experienced by university students in achievement settings (Respondek et al., 2017; Pekrun et al., 2002) and secondly all these three emotions are considered as the prime emotions related to academic achievement (Niculescu et al., 2015; Pekrun et al., 2011). In general, positive emotions tend to have a positive impact on students’ achievement and success, by strengthening learning strategies and motivation (Goetz et al., 2012). For example, enjoyment related negatively to high task focus, to effective self-regulation of learning, and to overall deeper learning (Frenzel et al., 2024; Obergriesser & Stoeger, 2020). On the other hand, negative emotions usually undermine motivation and interest, cause irrelevant thinking and reduce the cognitive resources for task performance (Daniels et al., 2009; Trigwell et al., 2012). For example, emotions like anger, anxiety, boredom and shame are related with shallow learning strategies and less frequent use of metacognitive strategies (Frenzel et al., 2024; Silaj et al., 2021). However, these associations are not always in the expected directions. For instance, positive emotions could lead to the adoption of superficial learning strategies, while some negative emotions may even boost learning (Pekrun et al., 2002; Goetz, et al., 2006). For these reasons, the research should be expanded and investigate more factors that could contribute to the relationship between emotions and learning. Moreover, it would be wise to explore discrete academic emotions in undergraduates’ learning, rather than examining general positive and negative emotions, in order to shed light on a more detailed manner.

In particular, enjoyment is considered to be a positive activating emotion that is classified as an activity emotion (Pekrun, 2018). When a student’s personal goals and learning task are in congruence, then they experience the academic emotion of enjoyment (Linnenbrink, 2007). Moreover, during enjoyment students consider the learning situation as positively valued and controllable (Camacho-Morles et al., 2021). The academic emotion of enjoyment has been found to positively predict students’ academic performance (Daniels et al., 2009). Anxiety is thought to be a negative activating emotion that is also ranked as an activity emotion (Pekrun, 2018) and is frequently reported among university students (Pekrun & Stephens, 2010). The academic emotion of anxiety is experienced when a student values negatively an achievement situation whereas they have moderate control over it. In general, anxiety may impair students’ task-irrelevant thinking and consequently, performance, but it could induce motivation to study harder, facilitating overall success, especially in individuals who are more resilient in particular emotion (Pekrun & Stephens, 2012). Boredom, a negative, deactivating emotion is also classified as an activity emotion (Pekrun, 2018). A student may experience boredom when there are no specific goals, or when the student’s personal goals and the given task do not match, and finally, when a learning activity is not valued as a positive one or negative one (Pekrun, 2011). Moreover, the lack of control and value over an activity may lead to an increase of boredom (Niculescu et al., 2015). The emotion of boredom goes hand in hand with negative feelings, lack of interest and stimulation and superficial approaches to learning (Pekrun et al., 2010; Sharp et al., 2017).

Pekrun (2018) proposes that students' academic emotions are primarily shaped by their achievement, control-related appraisals (such as competence beliefs, e.g., self-concept), and value appraisals (beliefs about the intrinsic or extrinsic worth of a subject area, e.g., achievement outcomes). Research has demonstrated that emotions play a crucial role not only in academic achievement but also in motivation (Sutter-Brandenberger et al., 2018). Emotions also influence individuals' intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Positive emotions, especially enjoyment, are crucial catalysts, of intrinsic motivation (Isen & Reeve, 2005). On the other hand, negative emotions like anxiety establish a positive correlation with extrinsic motivation or, more broadly, less autonomous forms of motivation. It is important to highlight that studies on emotions and intrinsic/extrinsic motivation from the perspective of self-determination theory have seldom been integrated (for exceptions, see Schwab et al., 2022). University settings generate intense emotions that are directly related to learning processes (Pekrun, 2019)

Student Approaches to Learning

The “student approaches to learning” tradition consists of one of the main frameworks for comprehending learning in higher education (Entwistle, 2018). Approaches to learning depict the different ways students go about learning, and they emerge from students’ perceptions of their academic activities that are influenced by their personal characteristics (Biggs, 1987). Approaches are categorized in three distinct types: deep, surface and organised approach (Marton & Säljö, 1997; Entwistle, McCune & Walker, 2001). During deep approach, motivation is intrinsic; the student is engaged with the new knowledge, seeking personal meaning and understanding. The deep approach has been positively associated with academic achievement and study success (Richardson et al., 2012), although, these associations have not been significant in all cases (Herrmann et al., 2017). During surface approach, the motivation is mainly extrinsic to the task; the student is focused on rote learning, usually memorizing fragmented parts of the given knowledge, while investing the minimum effort. Recent studies have revealed the negative association between the surface approach to learning and academic achievement (Chamorro-Premuzic et al., 2007; Karagiannopoulou & Milienos, 2015; Karagiannopoulou et al., 2019; Karagiannopoulou et al., 2022). However, the surface approach in specific demanding learning contexts may actually function as an effective coping mechanism (Kember, 2004). The third approach, the strategic, also known as organized studying, is considered as an approach to studying, organizing time and effort and is similar as a concept to self-regulation (Lindblom-Ylänne et al., 2018; Postareff et al., 2017). Most recent studies have revealed the beneficial effect of strategic approach on academic achievement (Herrmann et al., 2017; Richardson et al., 2012). Research suggests that strategic approaches can complement deep learning, while a lack of organization can affect both deep and surface learning styles (Haarala-Muhonen et al., 2017; Karagiannopoulou & Milienos, 2013). It can be argued that different combinations of approaches to learning are frequently employed among university students (Asikainen et al., 2020).

Until now, few studies have been studied approaches to learning along with academic emotions (Rentzios et al., 2019; Karagiannopoulou et al., 2022) and individual factors involved in learning (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2019; Vlachopanou & Karagiannopoulou, 2021). Students who feel positive emotions during their studies may prompt a deep approach to learning, while those who experience negative emotions during learning may adopt a more surface approach (Trigwell et al., 2012). Although the results of the aforementioned studies are in the expected directions, Postareff et al. (2017) clearly point the complex “web” of associations among academic emotions, approaches to learning and study success.

Learning, Emotional, Motivational Factors and University Students’ Profiles

There has been an increasing research interest in the study of different characteristics in the same groups of individuals. A range of studies show profiles of university students that correspond to adaptive, maladaptive, and dissonant groups of students (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2020; Milienos et al., 2021; Fryer & Vermunt, 2018). Most studies demonstrate three or four profiles that share specific characteristics. These studies suggest that different factors may coexist that contribute to students’ academic achievement and performance. For example, Parpala et al. (2010) found four discrete profiles based on approaches to learning. The first profile focuses on the strategic approach; they self-regulate their learning based on available time and prioritize their academic tasks. The second profile consists of students who take a deep approach to learning, while the third profile consists mainly of university students who opt for the surface approach to learning. The last profile, which is less distinct, consists of students who do not organise their studies but exhibit some characteristics of the deep approach. This profile is an example of a “dissonant” group of students whose common variables do not theoretically match (Lindblom-Ylänne & Lonka, 2000). These profiles are frequently identified in the relative literature (Parpala et al., 2021); it seems that temporary research needs to expand the range of factors that should be studied in order to explore this complex phenomenon of “dissonant” profiles. Moreover, Haarala-Muhonen et al. (2017) emphasised that the relationship between approaches to learning and academic achievement is not straightforward. On the same wavelength, Heikkilä et al. (2011) acknowledge the need to examine a combination of cognitive and emotional factors when researching the quality of learning. In their study, they found three groups of students: the “non-academic” students, the “self-directed” students and the “helpless” students. The first of the three profiles, the “non-academic”, was the most intriguing of all. This profile combines several facets that theoretically do not match and are not usually associated with positive academic performance. Nevertheless, students in this group seem to be successful in their academic tasks, they make progress, but they do it in a "relaxed" way and without achieving a high GPA (Heikkilä et al. 2011). This "relaxed" profile was also found in another study where students had low valence in their emotions but did well on their studies (Jarrell et al., 2017). In another relative study, Postareff et al. (2017) found a group of students who expressed negative emotions but still engaged in a deep approach to learning and made significant progress.

This atypical combination of emotional and cognitive factors has provided new insights regarding both learning outcomes and academic performance (Karagiannopoulou & Milienos, 2013; Rentzios, 2021). For example, Karagiannopoulou et al. (2019) identified three profiles based on approaches to learning and defence styles. They found a profile that is named “restricted maturity-dissonant unorganized students” with the lowest GPA, another that is called “defensive-reproduction-oriented students” with mid-low GPA, and lastly, the third that is named “mature and learning-advanced students” with the highest GPA. These profiles correspond to dissonant, surface and deep learners, with similar scores on adaptive and maladaptive defence styles. In a similar vein, Vlachopanou & Karagiannopoulou (2021) explored defense styles, academic procrastination, and well-being together with approaches to learning. They found three profiles: (a) "psychologically stable and adaptive" with the greatest GPA, (b) "immature and unstable at risk" with a low GPA, and (c) "defensively dissonant" with a mid-high GPA. It can be argued that we have also a similar learning pattern of deep, surface and dissonant respectively. The findings suggest that the stable adaptive deep/strategic group achieves the highest GPA, while surface and low dissonant students report the lowest.

The Present Study

This study aligns with current research indicating that academic emotions, emotion regulation, and academic motivation must be considered in research in educational contexts (Pekrun, 2024). Research clearly suggests that academic settings at universities emerge intense emotions, and it is feasible to explain them under conceptual frameworks such as CVT or theories of emotion regulation (Pekrun, 2019) or within the SDT (Sutter-Brandenberger et al., 2018). Therefore, the aims of the study are twofold: (a) the first aim is to analyze emotion regulation, academic emotions, academic motivation and approaches to learning that individual students experience during their learning process by clustering them on the basis of these variables, and (b) the second aim is to explore how students in distinct clusters differ regarding their GPA.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and Procedure

Employing a convenient sampling method, the sample consisted of 509 Greek university undergraduates, attending a fourth-year full degree program at the University of Ioannina in a Greek university. The participants were from two departments, social sciences and primary education, of whom 72 were men (13.5%) and 437 were women (86.3%). In Greece, there is a great imbalance between women and men in Social Sciences and Education departments (Eurostat, 2018). The age mean for the total sample was M = 20.5 years, with 93% of the sample to be under the age of 22 years old. In terms of years of study, 136 (25.8%) were first year students, 139 (26.4%) were second year students, 95 (18%) were third year students, 157 (29.8%) were fourth year or higher students.

Regarding procedure, the study took consideration of all ethical protocols. Students anonymously and voluntarily completed the questionnaires in their classes before or during an ordinary lecture, the completion of which lasted approximately 30 minutes on average. Prior to the administration, a written consent form was obtained from all participants. The purpose and the aims of the study were also explicitly stated. Besides, authors informed in a class meeting the scope and the aim of the present study. The data were collected during the 2019 winter semester. After this, all questionnaires were transferred, encoded and analyzed with SPSS 23.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Demographics

A short demographic questionnaire was filled out in order to collect some basic information about the students’ gender, age, department and year of study.

3.2.3. Academic Emotions

The discrete academic emotions of enjoyment, anxiety, boredom and hopelessness were each measured with the four learning-related scales of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (Pekrun et al., 2011). Students answered items on a five-point Likert scale (1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree) that referred to emotions that are experienced before, during, or after studying for a course. The enjoyment scale (10 items, e.g. “I enjoy dealing with the course material”), the anxiety scale (11 items, e.g. “I worry whether I’m able to cope with all my work”), the boredom scale (11 items, e.g. “Studying for my course bores me”). High scores on each emotion represent that the emotion is being experienced more strongly. The Cronbach’s alpha for this study was .79 for the academic emotion of Enjoyment, .82 for the academic emotion of Anxiety, .92 for the academic emotion of Boredom.

3.2.4. Approaches to Learning

In order to measure approaches to learning the Finish version of the Approaches to Learning and Studying Inventory (ALSI, Parpala et al., 2013) was implemented. The questionnaire consists of 16 items forming three approaches to learning: the deep approach (8 items, e.g. “I look at evidence carefully to reach my own conclusion about what I’m studying”), the surface approach (4 items, e.g. “Often I have to learn over and over things that don’t really make sense to me”) and the strategic approach (4 items, e.g. “I organize my study time carefully to make the best use of it”). Correspondents answered each item on a five-point Likert scale (1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree). High scores on each subscale reflect students’ preference for each approach. The inventory has been translated into Greek and used in studies showing good psychometric properties (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2014; Rentzios et al., 2019). In the present study internal consistency reliability was .74 for the Deep approach, .75 for the Surface approach and, .82 for the Strategic approach.

Emotion regulation

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) (Gross & John, 2003) was used to measure cognitive emotion regulation. It is a 10-item measure that assesses two common emotion regulation strategies: cognitive reappraisal (6 items) and expressive suppression (4 items). Responses are on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (=1) to “strongly agree” (=7). Example items for cognitive reappraisal include statements like “When I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I’m thinking about,” while for expressive suppression, an example is “I keep my emotions to myself.”

Academic self-regulation/motivation

The motivations of students for studying were evaluated using a modified version of the Academic Self-Regulation Scale (Ryan & Connell, 1989). The 16-item scale, which contains 4 items per regulation, ask participants to state their reason for studying. The measure consists of four subscales, tapping four different types of motivation for studying, that is, external regulation (e.g., “Because I’m supposed to do so”; 4 items); introjected regulation (e.g., “Because I want others to think I’m smart”; 4 items); identified regulation (e.g., “b Because I want to learn new things”; 4 items) and intrinsic motivation (e.g., “Because I enjoy doing it”; 4 items). Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Statistical Analysis

The latent structure of the variables of interest, was assessed by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to measure the correlation among the variables. Moreover, Cronbach’s α was also calculated in order to evaluate the reliability of the data.

A hierarchical cluster analysis was performed to identify groups of individuals with similar profiles across the selected variables. Prior to clustering, all variables were standardized using z-score normalization to ensure comparability across scales. Pairwise distances between observations were then calculated, using the Euclidean distance metric.

Several agglomerative methods were tested, including average, single, complete, and Ward’s linkage, and the method that yielded the highest agglomerative coefficient, indicating stronger clustering structure, was selected for further analysis.

The optimal number of clusters was determined using two complementary approaches: the gap statistic and a multi-index approach based on a comprehensive evaluation of established clustering indices, including the Hubert index and the D index (Hubert et al., 1985; 2. Tibshirani et al., 2001). Following the majority rule across these indices, we identified the most appropriate number of clusters.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to examine differences of the variables of interest among clusters, and as well as, the difference of GPA of the participants, among clusters. Post-hoc multiple tests examined the pairwise comparisons in case of statistically significant results from ANOVA. Furthermore, ANOVA was also used to explore the age differences between the clusters and Pearson’s chi-square was used to examine the sex differences among clusters. Discriminant Analysis was used to provide a detailed understanding of the findings from ANOVA, and finally, a Decision Tree model using the Exhaustive CHAID as growing method, with GPA as the dependent variable, explored the association among the variables of interest and the cluster membership with the GPA of the participants.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the Academic emotion variables (Enjoyment, Anxiety and Boredom), the Emotion regulation variables (Reappraisal and Suppression), the Academic self-regulation variables (External, Introjected, Identified and Intrinsic), and the Approaches to Learning variables (Deep, Surface and Organized) can be found in

Table 1. CFA results for the aforementioned variables are presented in

Table 2. Overall, the majority of the indices fall within acceptable value ranges, confirming the validity of the instruments' latent structures. More particularly, CFI, GFI, NFI and TLI exhibit high values (>0.90), whereas RMSEA and SRMR demonstrate low values (most of them <0.05).

The results of Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Cronbach’s α are presented in

Table 3. Overall, Cronbach’s α was greater than 0.74 for all variables of interest. Regarding the correlations among the variables of interest, Enjoyment was highly positive correlated with Identified, Intrinsic and Deep, and highly negative correlated with Boredom. Anxiety was highly positive correlated with Boredom and Surface. External regulation was highly positive correlated with Introjected, and Identified was highly positive correlated with Intrinsic.

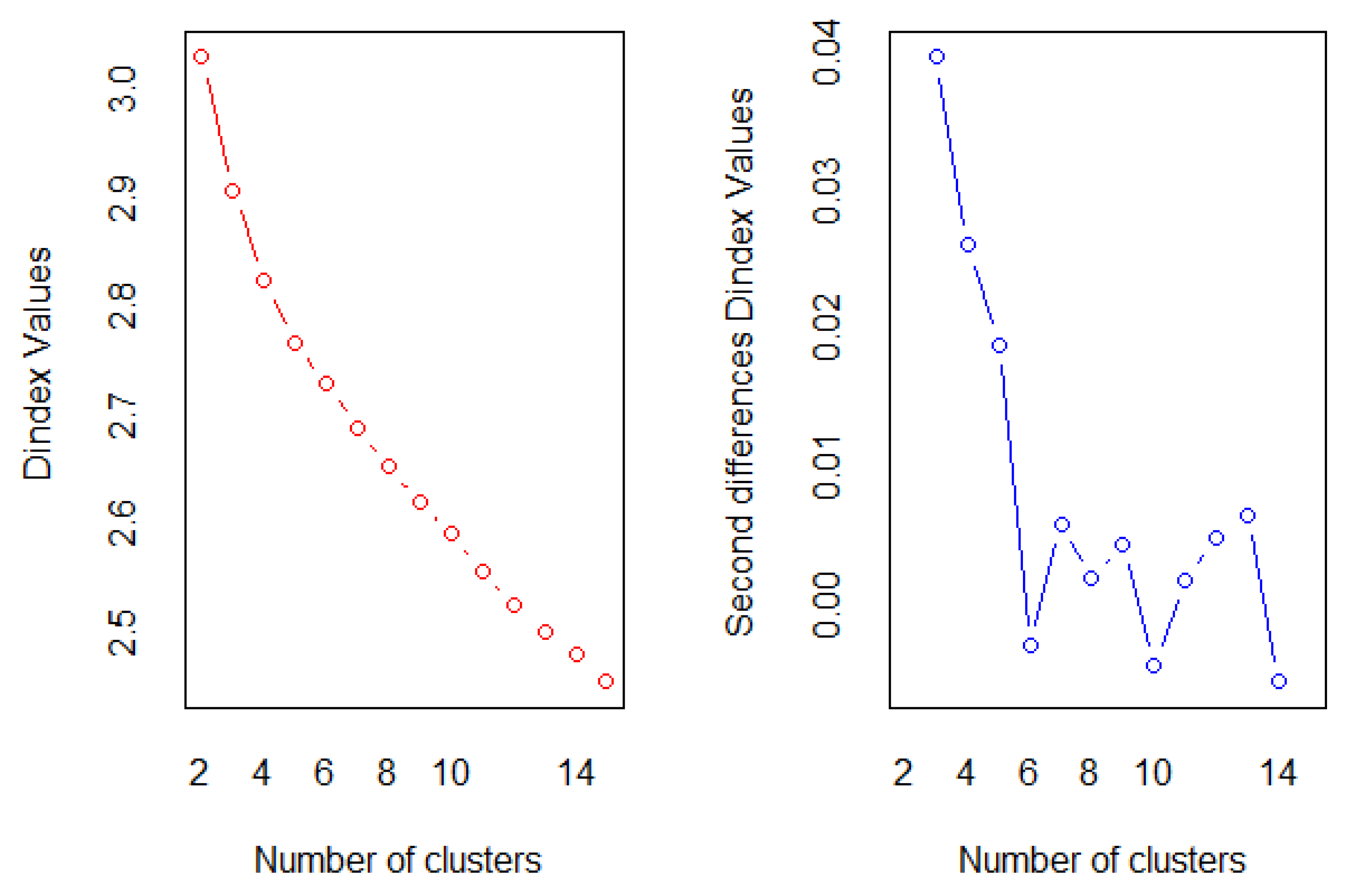

Using the Agglomerative Nesting Hierarchical Clustering we classified the participants into homogeneous groups based on their scores on variables associated with Academic emotions, Emotion regulation, Academic self-regulation and Approaches to Learning. Clustering was based on the dissimilarity matrix computed by the Euclidean distance, and the Ward method was performed. The Hubert and the D indexes that used for determining the optimal number of clusters, suggested that the 3-cluster is the best solution (

Figure 1).

Table 4 presents the mean values of the study variables across the three clusters. ANOVA ANOVA followed by post-hoc comparisons revealed statistically significant differences between clusters for all variables (p-value < 0.05).). In more detail, participants in cluster 2 had significantly higher mean scores in Enjoyment, Intrinsic and Deep, and significantly lower scores in Anxiety, Boredom, External Regulation, Introjected and Surface. Cluster 3 was characterized by significantly higher mean scores in Boredom and significantly lower scores in Enjoyment, Reappraisal, Identified, Intrinsic, Deep and Organized. Finally, cluster 1 contains participants with significantly higher scores in Introjected. ANOVA was also used to examine statistically significant differences in GPA and Performance across the three clusters. For both variables, there are statistically significant differences across the three clusters (p-value<0.05 for both variables).

Regarding the age of the participants, ANOVA showed statistically significant differentiations of the mean age among the clusters (p-value<0.05). Post-hoc comparisons demonstrated that there is a statistically significant difference in mean age among Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (19.51 years vs 19.97 years; p-value=0.024;

Table 5). Moreover, Pearson’s Chi-square test revealed that sex was not equally distributed among the clusters (p-value=0.008). Male participants were distributed as 16.2%, 42.6% and 41.2% among the three clusters, respectively, and female participants were distributed as 24%, 52.4% and 23.6% among the three clusters, respectively (

Table 4). More specifically, 83.8% of the males are placed in clusters 2 and 3, and regarding female participants, 52.4% are placed in cluster 2 and the rest 47.6% in clusters 1 and 3.

Discriminant analysis was performed to offer a more detailed insight into the ANOVA findings. The two discriminant functions were statistically significant, meaning that they both contribute to participant classification and should be interpreted (p-values<0.01;

Table 5). The first function explains 76.8% while the second explains 23.2% of the variance. The first function is mainly affected by boredom, organized (negatively), deep (negatively), external regulation and anxiety, whereas the second function is mainly affected by introjected and identified. Additionally, based on the classification results, 88% of cases are correctly classified to their clusters. Moreover, in

Table 5 we can observe that cluster 1 consists of students who have a positive mean at both functions (0.667, 1.263). This means that that students in cluster 1 have large values at anxiety, boredom, introjected, identified. Cluster 2 contains those who have a negative mean at both functions (-1.22, -0.216). This means that students in cluster 2 have large values at enjoyment, intrinsic, deep and organized. Finally, cluster 3 is consisted of students who have a positive mean at the first and a negative at the second function (1.817, -0.701). This means that students in cluster 3 have low values at enjoyment, reappraisal, identified, intrinsic, deep and organized.

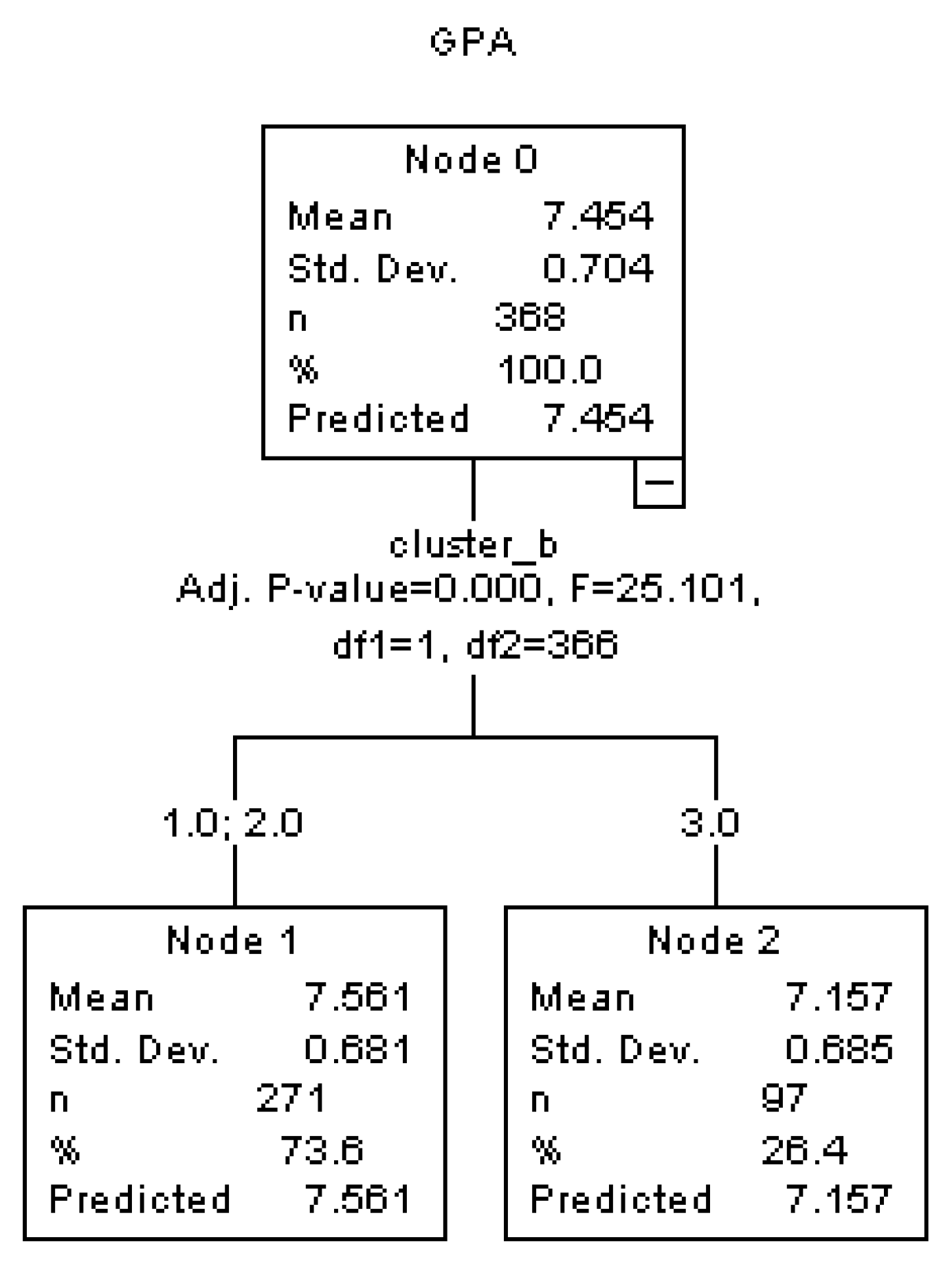

At last, a decision tree model with the GPA as dependent variable, examined the contribution of the variables of interest and the cluster membership to the GPA. The results of the decision tree indicated that only the cluster membership influence the GPA, showing the prime grade of the clustering (

Figure 2). In more detail, participants in cluster 3 (n=97), have a mean GPA of 7.157, while participants of the first two clusters (n=271) have a higher mean GPA of 7.561

Discussion

This study examines the emotional-learning profiles of university students, integrating approaches to learning with academic emotions, emotion regulation strategies and academic motivation. It draws on recent perspective about the combination of emotion regulation and academic emotions (Harley et al., 2019; Pekrun, 2018) while also, it involves SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2020) and approaches to leaning. The findings are aligned with current research indicating that to obtain a more holistic understanding of university students' learning and academic performance, it is essential to concurrently examine academic emotions, emotion regulation, and motivation within educational contexts (Pekrun, 2024). The study suggests three distinct profiles: the "Anxious, effectively-engaged, and organized learners" (Cluster 1), the "Deep, Happy and intrinsic motivated learners" (Cluster 2), and the " The Disengaged, Bored, and Suppressing Learners " (Cluster 3). This three-profile solution, which focuses on a combination of emotional, motivational, and learning factors corroborate previous studies that highlight the importance of emotions and emotion regulation variables in the learning process (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2020; Rentzios & Karagiannopoulou, 2021).

“Anxious, Effectively-Engaged, and Organized Learners: Cluster 1”

The first cluster, (Cluster 1), the “Anxious, effectively-engaged, and organized learners” provides new insights into the relationship between the academic emotion of anxiety, academic motivation, and learning behavior. This group is characterized by high scores in anxiety, that not surprisingly comes along with middle scores in a deep approach and high scores in surface, and organized approaches to learning. Interestingly, the use of these approaches to learning is followed by high extrinsic and identified regulation alongside intermediate introjected regulation. This profile highlights the complexity of learning in the presence of demanding academic settings (Postareff et al., 2017) and reveals a mixture of both motivation and learning approaches. It depicts a “dissonant” group of university students; the variables comprising this cluster do not theoretically fit together (Lindblom-Ylänne & Lonka, 2000; Parpala et al., 2022). Inconsistently with previous studies, these students reported a high GPA.

Possibly, the middle score in a deep approach to learning demonstrates an inherent interest in understanding new material and assimilating knowledge deeply (Hailikari et al., 2022). However, this comes along with the highest scores in surface and organized approaches. Such a dissonant combination of approaches to learning is possibly underpinned by individuals' high scores in both external and identified motivation along with middle scores in introjected motivation. Students seem to use a reproduction orientation (Vermunt & Donche, 2017) followed by some degree of personal understanding while they appear to have reached identified motivation which implies a degree of personal engagement with learning and understanding the rationale of studying as their own. The effective use of this combination of approaches to learning is depicted in high GPA (similarly high to that reported by students in cluster 2), and in the experience of a degree of enjoyment about their learning. However, the lack of intrinsic motivation and a degree of introjected motivation may lead to academic anxiety, which can be seen to be corroborated in the use of a surface approach. ANOVA and discriminant analysis consistently highlighted this pattern, indicating particularly high scores for anxiety, introjected and identified motivation in this group of students. This result is further supported by their poor use of emotion regulation strategies; they scored the lowest in suppression and reported a middle score in reappraisal. We suggest that the poor ER strategies may reflect that their emotion regulation skills have not fully developed yet (Martin et al., 2016); this group reported the lower average age.

In conclusion, the “Anxiously, effectively-engaged, and organized learners”, comprising a dissonant profile, strive to maintain a high score in GPA utilizing all approaches to learning and sustain an introjected motivation that is likely to support this goal. However, the second score in academic enjoyment, combined with the highest score in anxiety during learning, suggests an emotional burden that comes at a cost in their effort to achieve good grades, or even to acquire the ability to deeply engage and understand the learning material. It could be suggested that the need and the demanding motive to succeed may yield immediate results but also may undermine long-term well-being and the ability to self-regulate their learning (Vansteenkiste et al., 2018).

“Deep, Happy and intrinsic motivated learners”: Cluster 2

The second profile of our study, “the Deep, Happy and intrinsic motivated learners” was marked by the highest levels of the academic emotion of enjoyment, intrinsic motivation for learning, deep approach to learning, and organized studying. Not surprisingly, students in this cluster scored the lowest in surface approach and also in anxiety and boredom during studying. This profile represents an emotionally adaptive and highly self-regulated group of deep learners who engage effectively with academic demands, reflecting an emotionally and cognitively well-balanced deep profile. This profile is consistent with previous studies that explore similar variables (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2020; Milienos et al., 2021; Postareff et al., 2017).

The combination of deep and organized approaches is the most typical combination in every discipline at the university (Parpala et al., 2022); university students typically achieve the highest scores on the deep and the lowest on the surface approach (Herrmann et al., 2017). In our study, this group is the largest group. Furthermore, the highest level of intrinsic motivation in this group signifies that these students are motivated by a genuine interest followed by enjoyment for the engagement with the learning material depicted in deep learning. Intrinsic motivation drives a deep learning approach (Kyndt et al., 2010), while the positive activating emotion of enjoyment sustains persistence and effort, ultimately leading to a better understanding of the learning process that is possibly depicted in high score in organized study. Enjoyment remains a pivotal affective component associated to students’ motivation and engagement while keeping the level of focus in high standards in academic settings (Pekrun & Perry, 2014). This, when combined with an organized study (Enwistle, 2018), results in a higher GPA. ANOVA and discriminant analysis confirmed that these individuals demonstrated large values in enjoyment, deep and organized study. In our study, this group of students who scored high in both deep and organized approach reported the highest GPA, a result that is corroborated in other studies too (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2019; Ning & Downing, 2015).

Students in this cluster seem emotionally adaptive and effective in emotion regulation. They scored the highest in enjoyment and the lowest in anxiety and boredom. Moreover, they scored the highest in reappraisal and the lowest in suppression. They seem to adequately regulate their negative emotions while they keep enjoyment during learning. Effective emotion regulation during learning helps university students remain calm and focused on their tasks (Harley et al., 2019; Webster and Hadwin, 2015). Possibly, they pursue learning for its own sake, finding personal meaning in academic tasks rather than being influenced by external demands or internalized pressures. This intrinsic motivation aligns with high enjoyment and low boredom, as these individuals experience mostly positive emotions that keep their curiosity and commitment in the learning material. From this perspective, adaptive emotion regulation and dominance of positive emotion in comparison to negative ones (anxiety and boredom) allow students to analyse and interpret knowledge through comprehending the bigger picture (Parpala et al., 2022) free from inhibition imposed by negative emotions. We suggest that an adaptive emotional state is what enhances both learning and achievement; it allows the employment of deep learning, along with the use of effective time management skills and goal-setting strategies to maximize the learning process that results in the highest GPA. Such an interpretation sheds light on marginal differences in GPA with students in cluster 2 reporting the highest.

Overall, the " Deep, Happy and intrinsic motivated learners " show a typical mix of the best characteristics for academic emotions, emotion regulation, academic motivation, and learning styles. A profile that proves, in a way, that combining adaptive, motivation and cognitive strategies along with positive emotional facets may be beneficial not only for academic success but also for an emotional balance in university life.

"The Disengaged, Bored, and Suppressing Learners": Cluster 3

This profile is marked by the highest scores in boredom and suppression and the lowest score in enjoyment, reappraisal, identified and intrinsic motivation, deep and organized approach. It is a cluster that comprises negative qualities of emotional, motivational and learning constructs. Not surprisingly, these students reported the lowest GPA. We suggest that this group of students is at risk both in terms of learning and emotional experiences (Milienos et al., 2021).

In this context of interplay between learning and emotions, these students scored high in the surface approach to learning while the lowest in deep and organized approach. Such a reproducing approach came along with distinctively high boredom and high anxiety; anxiety in learning has been found to go hand in hand with the surface approach (Rentzios & Karagiannopoulou, 2021; Trigwell et al., 2012). Recent studies associate negative academic emotions with suppression (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2022; Rentzios & Karagiannopoulou, under review). In our study, students in this group scored the highest in suppression, while they scored the lowest in reappraisal. Although, in some cases, suppression may act as a beneficial factor helping individuals control their emotions and be essential in the academic context (Burić et al., 2016), in our study the use of suppression comes along with lower levels of both deep and organized approaches to learning. A similar pattern was found in the study of Ben-Eliyahu & Linnenbrink-Garcia (2015); they reported that suppressing emotions may hinder the effectiveness of learning strategies, as it demands greater regulatory resources. Possibly, students in order to regulate negative emotions, deploy suppression at the cost of a deep approach which demands an interrogative stance in learning as a prerequisite for curiosity and exploration (Desatnik et al., 2023; Karagiannopoulou et al., 2025 under review). Moreover, this interplay between learning and emotion is further supported by the lowest GPA, the dominance of boredom followed by the lowest score in enjoyment, in identified motivation and intrinsic motivation. Boredom, a “silent emotion” in comparison to other emotions, in academic environments has been widely associated with low intrinsic motivation and lack of interest (Pekrun et al., 2010). Moreover, it affects a wide range of constructs such as cognition, motivation, learning strategies, and academic performance (Pekrun, 2018; Tze et al., 2013). In fact, the highest score in boredom possible affects organized studying; the last is considered a critical factor in supporting university students’ well-being and academic achievement (Asikainen et al., 2014).

Their very restricted experience of enjoyment compared to other groups may further undermine their engagement with the learning material. This emotional detachment possibly depicts disengagement from the learning process; they scored the lowest in organized approach and intrinsic motivation. Research has shown that unorganized students could experience more study-related burnout (Asikainen et al., 2020). Besides, intrinsic motivation encourages individuals to engage in learning willingly, with interest, enthusiasm, and curiosity, considering this the most desirable form of motivation (Vansteenkiste et al., 2018). Students in this group scored the lowest in intrinsic motivation, suggesting that they lack a sense of volitional motivation toward the pursuit of their academic goals. The high scores on both external and introjected regulations demonstrate that their motivation stems from internalized demands and external pressure, a combination that usually undermines long-term objectives (Ryan & Deci, 2020). With the absence of intrinsic motivation, these university students are perceiving the academic activities as meaningless; possibly experiencing a strong emotional burden, which further intensifies their academic boredom and disengagement from learning depicted in the lowest GPA. ANOVA and discriminant analysis revealed that participants in this group have low values in enjoyment, reappraisal, intrinsic, deep and organized study.

In conclusion, the “The Disengaged, Bored, and Suppressing Learners” depicts a mix of maladaptive learning and motivational characteristics along with the dominant presence of boredom and suppression. These students approach learning with the minimum enjoyment and enthusiasm, with no organized techniques or the need to meaningfully understand learning material; they rely mainly on the surface approach to learning and struggle to manage their emotions through the emotion regulation of suppression. We suggest that this group of students, due to lack of interest and a combination of anxiety and high boredom can be a target group for intervention to ensure their support.

Limitations

Although, the study provides novel insights into the complex relations among academic emotions, emotion regulation, motivation, and approaches to learning, nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the self-report methodology, although widely recognized, fails to provide a more nuance picture of the interaction between the constructs examined in this study. Experimental or longitudinal studies may yield further information. Another restriction is the unbalanced representation of female participants in the study, resulting to the considerable gender imbalance favoring women; unfortunately, this imbalance is the norm in the social sciences departments from which the participants were drawn (Eurostat, 2018). Future research may further explore dissonance, frequently noted in educational literature (Karagiannopoulou et al., 2019; 2020; Parpala et al., 2022; Rentzios, 2021), by analyzing additional individual factors that appear more distal and are not seen to align theoretically, such as attachment, mentalizing, and epistemic trust, and their relationship to learning.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the importance of creating supportive learning environments that focus on academic emotions and their regulation while they foster intrinsic motivation. Moreover, our study sheds light on the value of a person-centered approach to comprehend the complex interplay among emotions, emotion regulation, motivation and learning. Each profile highlights distinct emotional and motivational dynamics, emphasizing that seeing the “one way approach” to support and teaching is not enough. The way students deal with their emerged academic emotions matters not only for their academic achievement, but also for their psychical health and well-being; the importance of emotions and emotion regulation in learning settings is critical and thus should be addressed in earlier educational stages (Stockinger et al., 2024). Through psychoeducational interventions, universities should foster intrinsic motivation and enhance emotion regulation strategies. These measures will help students, tutors, and academic advisors understand the complex interplay of emotions, and learning behaviors that emerge under demanding academic settings.

References

- Asikainen, H., Salmela-Aro, K., Parpala, A., & Katajavuori, N. (2020). Learning profiles and their relation to study-related burnout and academic achievement among university students. Learning and Individual Differences, 78. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Eliyahu, A., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2015). Integrating the regulation of affect, behavior, and cognition into self-regulated learning paradigms among secondary and post-secondary students. Metacognition and Learning, 10(1), 15–42. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. (1987). Student approaches to learning and studying. Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Boncquet, M., Flamant, N., Lavrijsen, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Verschueren, K., & Soenens, B. (2024). The unique importance of motivation and mindsets for students’ learning behavior and achievement: An examination at the level of between-student differences and within-student fluctuations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 116(3), 448–465. [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., Sorić, I., & Penezić, Z. (2016). Emotion regulation in academic domain: Development and validation of the academic emotion regulation questionnaire (AERQ). Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Morles, J., Slemp, G. R., Pekrun, R., Loderer, K., Hou, H., & Oades, L. G. (2021). Activity Achievement Emotions and Academic Performance: A Meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, . [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Furnham, A., & Lewis, M. (2007). Personality and approaches to learning predict preference for different teaching methods. Learning and Individual Differences, 17(3), 241-250. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, L. M., Stupnisky, R. H., Pekrun, R., Haynes, T. L., Perry, R. P., & Newall, N. E. (2009). A longitudinal analysis of achievement goals: From affective antecedents to emotional effects and achievement outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(4), 948. [CrossRef]

- Desatnik, A., Bird, A., Shmueli, A., Venger, I., & Fonagy, P. (2023). The mindful trajectory: Developmental changes in mentalizing throughout adolescence and young adulthood. PLoS ONE, 18(6), e0286500. [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, N. J. (2018). Student Learning and Academic Understanding: A Research Perspective and Implications for Teaching. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Entwistle, N. J., McCune, V. & Walker, P. (2001). Conceptions, styles and approaches within higher education: analytical abstractions and everyday experience, in: Sternberg and Zhang (Eds) Perspectives on cognitive, learning and thinking styles (pp. 103-136). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Eurostat. (2018). Distribution of Tertiary Education Graduates by Broad Field of Education, 2018 (%). Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Distribution_of_tertiary_education_ graduates_by_broad_field_of_education,_2018_(%25)_ET2020.png (accessed September 13, 2020).

- Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., & Stockinger, K. (2024). Emotion and emotion regulation. In K. R. Muis & P. A. Schutz (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (4th ed., pp. 219–244). Routledge.

- Fryer, L. K., & Vermunt, J. D. (2018). Regulating approaches to learning: Testing learning strategy convergences across a year at university. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(1), 21–41. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, T., Pekrun, R., Hall, N., & Haag, L. (2006). Academic emotions from a social-cognitive perspective: Antecedents and domain specificity of students’ affect in the context of Latin instruction. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(2), 289–308. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, T., Nett, U. E., Martiny, S. E., Hall, N. C., Pekrun, R., Dettmers, S., & Trautwein, U. (2012). Students' emotions during homework: Structures, self-concept antecedents, and achievement outcomes. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(2), 225-234. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. [CrossRef]

- Haarala-Muhonen, A., Ruohoniemi, M., Parpala, A., Komulainen, E., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2017). How do the different study profiles of first-year students predict their study success, study progress and the completion of degrees? Higher Education, 74(6), 949–962. [CrossRef]

- Harley, J. M., Pekrun, R., Taxer, J. L., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Emotion regulation in achievement situations: An integrated model. Educational Psychologist, 54(2), 106-126. [CrossRef]

- Hannula, M. S. (2006). Motivation in Mathematics: goals reflected in emotions. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 63(2), 165–178. [CrossRef]

- Hailikari, T., Virtanen, V., Vesalainen, M., & Postareff, L. (2022). Student perspectives on how different elements of constructive alignment support active learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 23(3), 217–231. [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, A., Niemivirta, M., Nieminen, J., & Lonka, K. (2011). Interrelations among university students’ approaches to learning, regulation of learning, and cognitive and attributional strategies: a person oriented approach. Higher Education, 61(5), 513–529. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, K. J., A. Bager-Elsborg, and V. McCune. 2017. Investigating the Relationships between Approaches to Learning, Learner Identities and Academic Achievement in Higher Education. Higher Education 74, 385–400. [CrossRef]

- Hubert, L., & Arabie, P. (1985). Comparing partitions. Journal of Classification, 2, 193–218.

- Jarrell, A., Harley, J. M., Lajoie, S., & Naismith, L. (2017). Success, failure and emotions: examining the relationship between performance feedback and emotions in diagnostic reasoning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(5), 1263–1284. [CrossRef]

- Karagiannopoulou, E., & Milienos, F. S. (2013). Exploring the relationship between experienced students' preference for open-and closed-book examinations, approaches to learning and achievement. Educational Research and Evaluation, 19(4), 271-296. [CrossRef]

- Karagiannopoulou, E., Milienos, F. S., Kamtsios, S., & Rentzios, C. (2019). Do defence styles and approaches to learning ‘fit together’ in students’ profiles? Differences between years of study. Educational Psychology, 40(5), 570–591. [CrossRef]

- Karagiannopoulou, E., Milienos, F. S., & Rentzios, C. (2020). Grouping learning approaches and emotional factors to predict students’ academic progress. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 10(2), 258–275. [CrossRef]

- Karagiannopoulou, E., Desatnik, A., Rentzios, C., & Ntritsos, G. (2022). The exploration of a ‘model’ for understanding the contribution of emotion regulation to students learning. The role of academic emotions and sense of coherence. Current Psychology, 42(30), 26491–26503. [CrossRef]

- Karagiannopoulou, E., Ntritsos, G., Rentzios, C. & Fonagy, P. (Under review). Taking a mentalizing and epistemic stance perspective of the three attachment styles. Psychological Reports.

- Kember, D. (2004). Interpreting student workload and the factors which shape students' perceptions of their workload. Studies in higher education, 29(2), 165-184.

- Kim, C., & Hodges, C. B. (2012). Effects of an emotion control treatment on academic emotions, motivation and achievement in an online mathematics course. Instructional Science, 40(1), 173–192. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C., & Pekrun, R. (2014). Emotions and motivation in learning and performance. In Springer eBooks (pp. 65–75). [CrossRef]

- Koole, S. L., Schlinkert, C., Maldei, T., & Baumann, N. (2019). Becoming who you are: An integrative review of self-determination theory and personality systems interactions theory. Journal of Personality, 87(1), 15–36. [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, E., Dochy, F., Struyven, K., & Cascallar, E. (2010). The direct and indirect effect of motivation for learning on students’ approaches to learning through the perceptions of workload and task complexity. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(2), 135–150. [CrossRef]

- Koenka, A. C. (2020). Academic motivation theories revisited: An interactive dialog between motivation scholars on recent contributions, underexplored issues, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101831. [CrossRef]

- Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Lonka, K. (2000). Dissonant study orchestrations of high-achieving university students. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 15(1), 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Lindblom-Ylänne, S., Parpala, A., & Postareff, L. (2018). What constitutes the surface approach to learning in the light of new empirical evidence?. Studies in Higher Education, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Linnenbrink, E. A. (2007). The role of affect in student learning: A multi-dimensional approach to considering the interaction of affect, motivation, and engagement. In P. A. Schutz & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 107–124). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Lonka, K., Ketonen, E., & Vermunt, J. D. (2021). University students’ epistemic profiles, conceptions of learning, and academic performance. Higher Education, 81(4), 775–793. [CrossRef]

- Losenno, K. M., Muis, K. R., Munzar, B., Denton, C. A., & Perry, N. E. (2020). The dynamic roles of cognitive reappraisal and self-regulated learning during mathematics problem solving: A mixed methods investigation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101869. [CrossRef]

- Marton, F., & Saljo, R. (1997). Approaches to learning. In F. Marton, D. Hounsell, & N. J. Entwistle (Eds.), The experience of learning. Implications for teaching and studying in higher education (2nd ed.), pp. 39–58. Scottish Academic Press.

- Martin, R. E., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). The neuroscience of emotion regulation development: implications for education. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 10, 142–148. [CrossRef]

- McRae, K., & Gross, J. J. (2020). Emotion regulation. Emotion, 20(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- McRae, K., Gross, J. J., Weber, J., Robertson, E. R., Sokol-Hessner, P., Ray, R. D., Gabrieli, J. D., & Ochsner, K. N. (2012). The development of emotion regulation: an fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal in children, adolescents and young adults. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(1), 11–22. [CrossRef]

- Miele, D. B., Rosenzweig, E. Q., & Browman, A. S. (2024). Motivation. In P. Schutz & K. Muis (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Milienos, F. S., Rentzios, C., Catrysse, L., Gijbels, D., Mastrokoukou, S., Longobardi, C., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (2021). The contribution of learning and mental health variables in first-year students’ profiles. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1259. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, A.C., Tempelaar, D., Dailey-Hebert, A., Segers, M., & Gijselaers, W. (2015). Exploring the antecedents of learning-related emotions and their relations with achievement outcomes. Frontline Learning Research, 3(1), 1-17.

- Ning, H. K., & Downing, K. (2015). A latent profile analysis of university students’ self-regulated learning strategies. Studies in Higher Education, 40(7), 1328–1346. [CrossRef]

- Obergriesser, S., & Stoeger, H. (2020). Students’ emotions of enjoyment and boredom and their use of cognitive learning strategies—How do they affect one another? Learning and Instruction, 66, 101285. [CrossRef]

- Op’t Eynde, P., & Turner, J. E. (2006). Focusing on the complexity of emotion issues in academic learning: A Dynamical Component Systems approach. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 361–376. [CrossRef]

- Parpala, A., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., Komulainen, E., Litmanen, T., & Hirsto, L. (2010). Students’ approaches to learning and their experiences of the teaching-learning environment in different disciplines. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(2), 269–282. [CrossRef]

- Parpala, A., Mattsson, M., Herrmann, K. J., Bager-Elsborg, A., &Hailikari, T. (2021). Detecting the Variability in Student Learning in Different Disciplines—A Person-Oriented Approach. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: Assumptions, Corollaries, and Implications for Educational Research and Practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2013). Emotion, motivation, and self-regulation: Common principles and future directions. In Hall, N. & Goetz, T. (Eds.), Emotion, motivation, and self-regulation: A handbook for teachers (pp. 167–188).

- Pekrun, R. (2018). Control-value theory: A social-cognitive approach to achievement emotions. In G. A. D. Liem & D. M. McInerney (Eds.), Big theories revisited 2: A volume of research on sociocultural influences on motivation and learning (pp. 162–190). Information Age Publishing.

- Pekrun, R. (2019). Inquiry on emotions in higher education: progress and open problems. Studies in Higher Education, 44(10), 1806–1811. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-Value Theory: from achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3). [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Control-value theory of achievement emotions. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 120–141). Routledge.

- Pekrun, R., & Stephens, S. J. (2010). Achievement emotions in higher education. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (vol. 25, pp. 257–306). New York, NY: Springer.

- Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. J. (2012). Academic emotions. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, S. Graham, J. M. Royer, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA educational psychology handbook, Vol. 2. Individual differences and cultural and contextual factors (p. 3–31). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students' self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational psychologist, 37(2), 91-105. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Daniels, L. M., Stupnisky, R. H., & Perry, R. P. (2010). Boredom in achievement settings: Exploring control–value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 531–549. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 36–48. [CrossRef]

- Postareff, L., Mattsson, M., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Hailikari, T. (2017). The complex relationship between emotions, approaches to learning, study success and study progress during the transition to university. Higher Education, 73(3), 441–457. [CrossRef]

- Rentzios, C. (2021). Adult attachment styles and approaches to learning: The role of emotion regulation and academic emotions (Publication No. 10.12681/eadd/51003) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Ioannina]. http://hdl.handle.net/10442/hedi/51003.

- Rentzios, C., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (2021). Rethinking Associations between Distal Factors and Learning: Attachment, Approaches to Learning and the Mediating Role of Academic Emotions. Psychology, 12(06), 899–924. [CrossRef]

- Rentzios, C., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (under review). Attachment styles, emotion regulation, academic emotions, and approaches to learning: a person-oriented approach. Trends in Psychology.

- Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Stupnisky, R., & Nett, U. E. (2017). Perceived Academic Control and Academic Emotions Predict Undergraduate University Student Success: Examining Effects on Dropout Intention and Achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students' academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 138(2), 353-387. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K. A., Ranellucci, J., Lee, Y., Wormington, S. V., Roseth, C. J., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2017). Affective profiles and academic success in a college science course. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 209–221. [CrossRef]

- Roth, G., Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). Integrative emotion regulation: Process and development from a self-determination theory perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 31(3), 945–956. [CrossRef]

- Rottweiler, A. L., Taxer, J. L., & Nett, U. E. (2018). Context Matters in the Effectiveness of Emotion Regulation Strategies. AERA Open, 4(2), 233285841877884. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749–761. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological.

-

needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, C., Frenzel, A. C., Daumiller, M., Dresel, M., Dickhäuser, O., Janke, S., & Marx, A. K. G. (2022). “I’m tired of black boxes!”: A systematic comparison of faculty well-being and need satisfaction before and during the COVID-19 crisis. PLoS ONE, 17(10), e0272738. [CrossRef]

- Sharp, J. G., Hemmings, B., Kay, R., & Atkin, C. (2017). Academic boredom, approaches to learning and the final-year degree outcomes of undergraduate students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(8), 1055–1077. [CrossRef]

- Silaj, K. M., Schwartz, S. T., Siegel, A. L. M., & Castel, A. D. (2021). Test anxiety and metacogni tive performance in the classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1809–1834. [CrossRef]

- Spann, C. A., Shute, V. J., Rahimi, S., & D’Mello, S. K. (2019). The productive role of cognitive reappraisal in regulating affect during game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 358–369. [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, K., Dresel, M., Marsh, H. W., & Pekrun, R. (2024). Strategies for regulating achievement emotions: Conceptualization and relations with university students’ emotions, well-being, and health. Learning and Instruction, 102089. [CrossRef]

- Suri, G., Whittaker, K., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Launching reappraisal: It’s less common than you might think. Emotion, 15(1), 73–77. [CrossRef]

- Sutter-Brandenberger, C. C., Hagenauer, G., & Hascher, T. (2018). Students’ self-determined motivation and negative emotions in mathematics in lower secondary education—Investigating reciprocal relations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 55, 166–175. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G., Jungert, T., Mageau, G. A., Schattke, K., Dedic, H., Rosenfield, S., & Koestner, R. (2014). A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39(4), 342–358.

- Tibshirani, R., Walther, G., & Hastie, T. (2001). Estimating the number of clusters in a data set via the gap statistic. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 63(2), 411–423.

- Trigwell, K., Ellis, R. A., & Han, F. (2012). Relations between students' approaches to learning, experienced emotions and outcomes of learning. Studies in Higher Education, 37(7), 811-824. [CrossRef]

- Tuononen, T., Hyytinen, H., Räisänen, M., Hailikari, T., & Parpala, A. (2022). Metacognitive awareness in relation to university students’ learning profiles. Metacognition and Learning, 18(1), 37–54. [CrossRef]

- Tze, V. M. C., Daniels, L.M., Klassen, R.M., & Li, J. C.-H. (2013a). Canadian and Chinese university students’ approaches to coping with academic boredom. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 32–43. [CrossRef]

- Vandercammen, L., Hofmans, J., & Theuns, P. (2013). The mediating role of affect in the relationship between need satisfaction and autonomous motivation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 62–79. [CrossRef]

- Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Wouters, S., Verschueren, K., Briers, V., Deeren, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2016). The pursuit of self-esteem and its motivational implications. Psychologica Belgica, 56(2), 143–168. [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic versus extrinsic Goal Contents in Self-Determination Theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41(1), 19–31. [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Sierens, E., Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., & Lens, W. (2009). Motivational profiles from a self-determination perspective: The quality of motivation matters. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 671–688. [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Aelterman, N., De Muynck, G., Haerens, L., Patall, E., & Reeve, J. (2018). Fostering Personal Meaning and Self-relevance: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Internalization. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(1), 30–49. [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., & Waterschoot, J. (2022). Catalyzing intrinsic and internalized motivation: The role of basic psychological needs and their support. In A. O’Donnell, N. C. Barnes, & J. Reeve (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of educational psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Vermunt, J. D., & Donche, V. (2017). A Learning Patterns Perspective on student learning in higher Education: state of the art and moving forward. Educational Psychology Review, 29(2), 269–299. [CrossRef]

- Vlachopanou, P., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (2021). Defense styles, academic procrastination, psychological wellbeing, and approaches to learning. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210(3), 186–193. [CrossRef]

- Webster, E. A., & Hadwin, A. F. (2015). Emotions and emotion regulation in undergraduate studying: examining students’ reports from a self-regulated learning perspective. Educational Psychology, 35(7), 794–818. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).