1. Introduction

In recent decades, there has been a growing concern among teachers and educators about understanding students' attempts to manage their learning processes and their relentless efforts to achieve success. This effort is manifested through activities that influence these processes' initiation, direction and persistence. The self-regulation of learning among school-aged students stands out as a fundamental developmental process, anticipating the outcomes of their educational journey over time and across various areas of knowledge [

1]. The self-regulation of learning skills naturally evolves as students mature and are exposed to diverse environmental variables, such as the classroom context. Given the significance of self-regulation in school environments, it is essential to understand how academic time management planning in school activities (short-term and long-term), when interlinked with procrastination (in daily study or for tests), can shape and influence the self-regulatory learning processes.

The Programme for International Student Assessment [

2] report highlighted a troubling global issue: students' lack of engagement and motivation. This reality has led to a concerning decline in proficiency in essential areas of knowledge (Reading, Mathematics, and Science) with significant social implications. So, it is necessary to seek immediate answers and results, prompting us to reflect on the link between self-regulation of learning and the variables that influence the organization of students’ study time and other school activities.

This issue is vital in an era marked by rapid technological development and numerous distractions, where student motivation and engagement are crucial for school success. In the dynamic contemporary educational context, the research seeks to understand the factors that drive school performance, with particular attention to students’ active role in cognitive, behavioral, and motivational domains [

3].

The European Commission has noted that the Portuguese educational system, although unique in this issue, needs to improve in its areas regarding students' academic performance [

4]. Goal 4 of the 17 SDGs also points out quality education. This underscores the importance of exploring the relationship between the constructs of the present study. Educational research demonstrates an increasing concern with the dynamics that influence the improvement of academic performance, emphasizing the active role of students in cognitive, behavioral, and motivational dimensions [

5].

One of the fundamental objectives of self-regulation of learning is to investigate how students become active agents of their learning, guiding and regulating cognition, motivation, and behavior towards established goals [

6]. This approach highlights the need to develop an educational culture that positions self-regulation of learning as a crucial objective in the psycho-pedagogical projects of schools [

7]. This orientation underscores the importance of student activity in controlling their learning process from a sociocognitive perspective, emphasizing its foundational concepts and revealing the imperative need to incorporate strategies that promote self-regulation of learning, aiming for more effective learning. In this context, the literature review assigns paramount significance to the self-regulation of learning study, emphasizing the individual and contextual conditions that promote school success. The focus falls on crucial variables such as academic time management planning and attitudes and behaviors related to procrastination, with these multidimensional constructs being highlighted as determinants for achieving desired mastery in learning processes. The literature review on these variables underscores the importance of these constructs for a comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to educational success [

3,

8].

Considering the sociocognitive framework and according to Zimmerman [

9], the self-regulation of learning construct is intrinsically linked to the thoughts, feelings, and actions that students systematically generate and direct to achieve their goals. For this purpose, and according to the authors, students must continually employ cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral strategies. Among the necessary behaviors in the self-regulatory process of their learning are setting realistic and timely goals, developing a plan to guide their study, and applying various learning strategies [

10].

Thus, to be considered self-regulated, students must perceive themselves as metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral agents in their learning process [

6]. According to Zimmerman [

9], if students cannot accurately discern the level of their cognitions, it is uncertain whether they will engage in advanced metacognitive activities, such as realistically evaluating their learning or effectively planning its control. From this perspective, guiding students to acquire knowledge about their learning and develop skills to manage and regulate it is essential. The author mentions that this activity can occur independently, cooperatively, or collaboratively, promoting changes in knowledge, beliefs, and strategies that students can transfer to new contexts.

The importance of exploring the connection between these constructs stems from the fact that academic time management planning is considered a vital tool for students' self-regulation of learning. It directly impacts the quality of the learning process and promotes a more organized and structured approach to studying [

3,

8]. On the other hand, procrastination, when controlled and minimized through academic time management planning [

3], positively influences the self-regulation of learning [

11], contributing to successful learning outcomes [

12].

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Self-Regulated Learning

Three decades of research on self-regulation of learning reveal that this construct is crucial in learning processes and profoundly influences students' academic proficiency [

6]. Self-regulation of learning, inherently multidimensional, describes how individuals guide and control their cognitions, emotions, motivations, and behaviors, aiming to achieve goals and adapt to environmental demands [

13].

The theoretical framework suggests several targets for individuals' self-regulation, such as emotional regulation and self-regulated learning, are intertwined by the mutual dependence of underlying processes, such as executive functions and metacognition. Empirical studies in Developmental Psychology have revealed that the early self-regulatory abilities of young students, often assessed through executive functioning, are associated with high levels of effortful control, positive relationships with teachers and peers, and favorable school adjustment [

7,

14].

Although research suggests that self-regulation of learning is an evolving process that becomes more coordinated over time [

15,

16] and predicts academic outcomes from preschool to university [

17], doubts persist about how different aspects of self-regulation of learning develop together to support student learning. In particular, the relationship between self-regulation of learning, academic time management planning, and procrastination in elementary and secondary students, both in the classroom and over time, still needs more clarification.

According to the theoretical models of Schunk and Zimmerman, and the extensive bibliography produced by these authors on the subject [

6,

9], the main objectives of self-regulation of learning include [

10]: Defining specific and challenging goals: Students should outline clear and ambitious goals to guide their learning efforts; Monitoring progress toward goals: It is crucial for students to regularly track their progress against set objectives, assess their performance, and adjust their strategies as needed; Applying effective self-regulation strategies: Students must identify and use effective strategies to achieve their learning goals, such as study organization, memorization techniques, and self-reflection; Managing time and resources effectively: Students should learn to manage their time and resources efficiently, prioritizing tasks, setting schedules, and utilizing available resources effectively; and Controlling and regulating emotions: self-regulation of learning also involves controlling and regulating emotions, including managing stress, anxiety, and motivation to persist in facing challenges.

Therefore, it is imperative to understand how the various targets of self-regulation of learning develop and manifest in students across different learning domains and classroom contexts. There are gaps in the research on the strategies used in students' self-regulation of learning processes in other areas of knowledge and the impact of pedagogical practices on their self-regulation skills. Thus, it becomes vital to uncover how self-regulation processes unfold in students and find ways to foster these self-regulatory abilities across various fields of learning [

7].

2.2. Academic Time Management Planning

Whenever we examine the school environment, we inevitably encounter pertinent questions: How do young students manage their academic time? Why do some diligently commit to school tasks while others delay them until the last minute or do not complete them? Today, one of the essential challenges for teachers is encouraging students to engage more constructively and participative in the learning processes to achieve school excellence [

12].

Research on study skills considers academic time management planning a central pillar of learning strategies [

3]. This time management, described by Casiraghi et al. (2020) [

18] as a planning behavior, is linked to the perception of the effort required to face various learning challenges, improving with motivation and goal setting. According to Lourenço and Paiva [

7], self-regulation of learning strategies, including time management planning, should guide school activity. Understanding the students who populate the classrooms and adopting varied approaches and techniques that meet their needs is crucial in helping them organize their study and personal time management.

The authors emphasize that the difference between academic success and failure is intrinsically linked to variables such as academic time management, study methods, and the relationship between performance and effort. Thus, it can be said that the greater the student's perception of control over the time spent on all school activities, the lower the stress they experience. Several studies highlight the positive influence of time management skills on student learning and outcomes [

3,

18], providing them with the means to structure and control their activities.

Students who adapt best to academic experiences cultivate proper study habits, demonstrate effective time management combined with content organization, and employ learning resources and strategies [

19]. The author also notes that academic performance is explained by the ability to engage, plan, and meet deadlines for proposed activities and the perception of good study habits.

The results of Noro and Moya [

20] study indicate the impact of study hours on academic performance, showing that students who dedicated more weekly time to studying achieved better exam results. Casiraghi et al. [

18] add that, in addition to effective time management for school tasks, students must adopt learning strategies to achieve good academic performance. Among these strategies are self-assessment, organization and transformation of content, goal setting and planning, seeking and properly recording information, self-monitoring, organizing the study environment, seeking help and continuous review.

Some studies highlight factors that can hinder the management of study time, such as study organization, test preparation, and the study environment [

3,

21]. Difficulties in concentration, the absence of a conducive study space at home, closely linked to distraction, and the lack of planning and preparation of activities to achieve learning goals are equally relevant [25]. Lourenço and Paiva [

7] study indicate that by using appropriate resources, students develop satisfactory study habits associated with good organization and planning of learning. It is important to note that how students manage their time can be seen as an essential condition for using self-regulated learning strategies.

Time planning is a purpose-driven process involving assessing time use, goal setting, planning, monitoring, and prioritizing tasks to achieve objectives [

22]. Specifically, the authors describe steps to assist in personal time management, including diagnosing time use, developing strategies to address challenges, setting goals and objectives, and implementing and evaluating changes. These efforts result in increased individual proficiency, culminating in better school outcomes.

In this line of research, Thibodeaux et al. [

11] assert that students with high school performance often set clear goals, calculate the time needed to complete tasks and maintain a rigorous study routine. Additionally, these students frequently assess the progress made in the learning process, thus mitigating the impact of procrastination on their school activities.

2.3. Procrastination

Procrastination is a recurring phenomenon characterized by the tendency to delay or postpone tasks [

23]. It can be understood as the intentional postponement of a task perceived as unstimulating, even in the face of potential negative consequences or harm from that action [

24]. The author further notes that procrastinators may exhibit behaviors such as task avoidance, delaying action, and postponing task completion; and, at the cognitive or decision-making level, indecision and deliberate delay in making decisions. Both types of procrastination appear to be positively associated with affective responses and time perception and negatively related to internal stimulation [

25]. This behavior manifests in various daily tasks and contexts, with particular emphasis on school procrastination, which, despite its potential disadvantages for students, is frequently experienced [

3,

26].

Students tend to adopt behaviors such as delaying the preparation and submission of assignments, neglecting activities, and leaving exam study until the last moment [

27]. They highlight that, in general, procrastination tends to be more common in situations where the volume and complexity of demands increase. Additionally, Fior et al. [

28] assert that some reasons that can be pointed out as causes for procrastination include poor time management dedicated to school tasks, environmental context, difficulty in concentration, anxiety regarding assessment, dysfunctional beliefs and thoughts, difficulty in dealing with obstacles, fear of failure, low frustration tolerance, and difficulty in task execution. The authors reinforce that the main variables involving academic procrastination behavior are self-efficacy, autonomous learning regulation, and perfectionism.

According to Furlan and Martínez-Santos [

29] procrastination behavior can be closely linked to how an individual behaves in assessment situations, including both adaptive behaviors (e.g., maintaining focus during a test) and maladaptive behaviors (e.g., avoidance or task postponement). In this sense, individuals with maladaptive perfectionist traits tend to resort to task avoidance strategies, often manifesting through procrastination.

Procrastination is a maladaptive situational behavior, namely, a failure of self-regulation resulting in actively dysregulating conduct. Through this, students postpone or avoid academic tasks perceived as aversive, aiming to obtain temporary relief [

25]. They also mention that these anxiety-inducing behaviors tend to delay academic progress, accumulate materials, and result in potential failures, leading to dissatisfaction and unsatisfactory academic performance. Thus, procrastination, characterized by task postponement, is linked to poor academic time management and students' self-regulatory processes. This behavior, typical in academic contexts, results from anxiety, perfectionism, and fear of failure, leading to delays in task preparation and submission, compromising performance, and causing academic dissatisfaction [

26].

2.4. Study Objective

Given the significance of self-regulation in school environments, it is essential to understand how planning time management in school activities, both in the short and long term, when interlinked with procrastination (in daily study or for tests), influences self-regulatory learning processes. Thus, this study aims to analyze the predictability of academic time management and procrastination in students' self-regulated learning. In this way, the following hypotheses were defined: H1) Students who show more planning of academic time management, both in the short and long term, tend to have higher levels of self-regulation of learning; H2) Students who show a greater tendency to procrastinate tend to have lower levels of self-regulation of learning; H3) Students who show more planning of academic time management in school activities, both in the short and long term, tend to have lower levels of procrastination.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The study included 690 students (365 are girls) from public schools in northern Portugal (third-cycle: 7th, 8th, and 9th grades). The participants were between 12 and 15 years old (Mage=12.9). Of the sample collected, 48.7% were in the 7th, 29.9% in the 8th, and 21.4% in the 9th. Convenience sampling, a non-probabilistic technique, was used to gather the sample.

3.2. Instruments

Self-Regulated Learning Processes Inventory (SRLPI) [

30]: This questionnaire consists of 9 items, organized into three dimensions: Planning, 3 items (α=.80; e.g., I make a plan before starting a task. I think about what I'm going to do and what is necessary to complete it); Execution, 3 items (α=.87; e.g., During classes or while studying at home, I think about specific aspects of my behavior to change and achieve my goals); and Evaluation, 3 items (α=.84; e.g., When I receive a grade, I think about specific things I need to do to improve). A five-point Likert scale ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Time Management Planning Inventory (TMPI) [

10]: This questionnaire consists of 12 items, distributed across two dimensions of equal number: short-term, 6 items (α=.89; e.g., I make a daily list of things I need to do) and long-term, 6 items (α =.90; e.g., I organize my study according to the test schedule). It uses a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Student Perceived Academic Procrastination (SPAP) [

31]: This questionnaire includes 10 items divided into two dimensions: Daily study procrastination, 5 items (α=.80; e.g., When the teacher assigns a task in class, I start doing it immediately); and Test study procrastination, 5 items (α=.82; e.g., When a task is very difficult, I give up and move on to another task). A five-point Likert format ranges from 1 (never or rarely) to 5 (always or almost always).

All instruments were validated in the Portuguese context, and the values presented refer to the present study. A questionnaire was also used to assess personal and academic data (age, gender, and school year) to characterize the sample.

3.3. Procedures

With approval from the school directors and guardians of the participants, every procedure in this study adhered to the ethical guidelines specified in the Helsinki Declaration [

32]. Researchers collected the data in a single session per school, during which they informed the students about the study's aim and assured them of the ethical procedures (anonymity, confidentiality of responses, and voluntary participation). Participants in this study had to be third-cycle (7th, 8th, and 9th grades) from public schools to meet the inclusion criteria. The battery of instruments took the students about 20 minutes to complete. Only questionnaires that were filled out were deemed suitable for analysis.

3.4. Data Analysis

Validity and reliability assessment of the instruments were conducted by checking the adequacy values of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index and Bartlett’s sphericity test. Given the Likert nature of the items, the reliability of scores and construct was assessed respectively with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α) and its confidence intervals, where values above 0.70 at the lower limit are considered acceptable. Pearson’s linear correlation (r) was used to analyze the strength of associations between constructs. Thus, values below 0.200 indicate a very low association, values between 0.200–0.399 indicate a low association, values between 0.400–0.699 indicate a moderate association, values between 0.700–0.899 indicate a high association, and values between 0.900–1 indicate a very high association.

Data analysis was conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and the SPSS/AMOS 29 software [

33]. Preliminary evaluation involved the analysis of univariate normality through skewness coefficients (< 2) and kurtosis (< 7). SEM models are considered well-fitting when GFI ≥ 0.90; AGFI ≥ 0.90; TLI ≥ 0.90); Critical N > 200; CFI > 0.90; and RMSEA between 0.05 and 0.08 with a lower limit of the 90% confidence interval less than 0.05. Factor loadings ≥ 0.40 were considered significant.

4. Results

The SRLPI had a KMO value of 0.818, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2(36) = 3317.214; p<0.001), and an explained variance of approximately 76.7%. The TMPI had a KMO index of 0.883, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2(66) = 5322.362; p<0.001), and an explained variance of approximately 67.3%. The SPAP had a KMO index of 0.789, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2(45) = 2527.678; p<0.001), and an explained variance of approximately 58.3%.

Table 1 presents the descriptive data of the variables composing the SEM model. In this sample, no variable meets extreme criteria, confirming the suitability of the proposed model fit estimation.

About the overall fit indices of the proposed SEM model, the obtained values prove to be robust [χ2(11) = 17.772; p = 0.087; χ²/df = 1.616; GFI = 0.993; AGFI = 0.982; TLI = 0.985; CFI = 0.992; RMSEA =0 .030 (90% CI: 0.000-0.054); CN (0.05/763; 0.01/959)]. These results support the hypothesis that the proposed model effectively represents the relationships among the variables in the empirical matrix, thereby validating its theoretical framework.

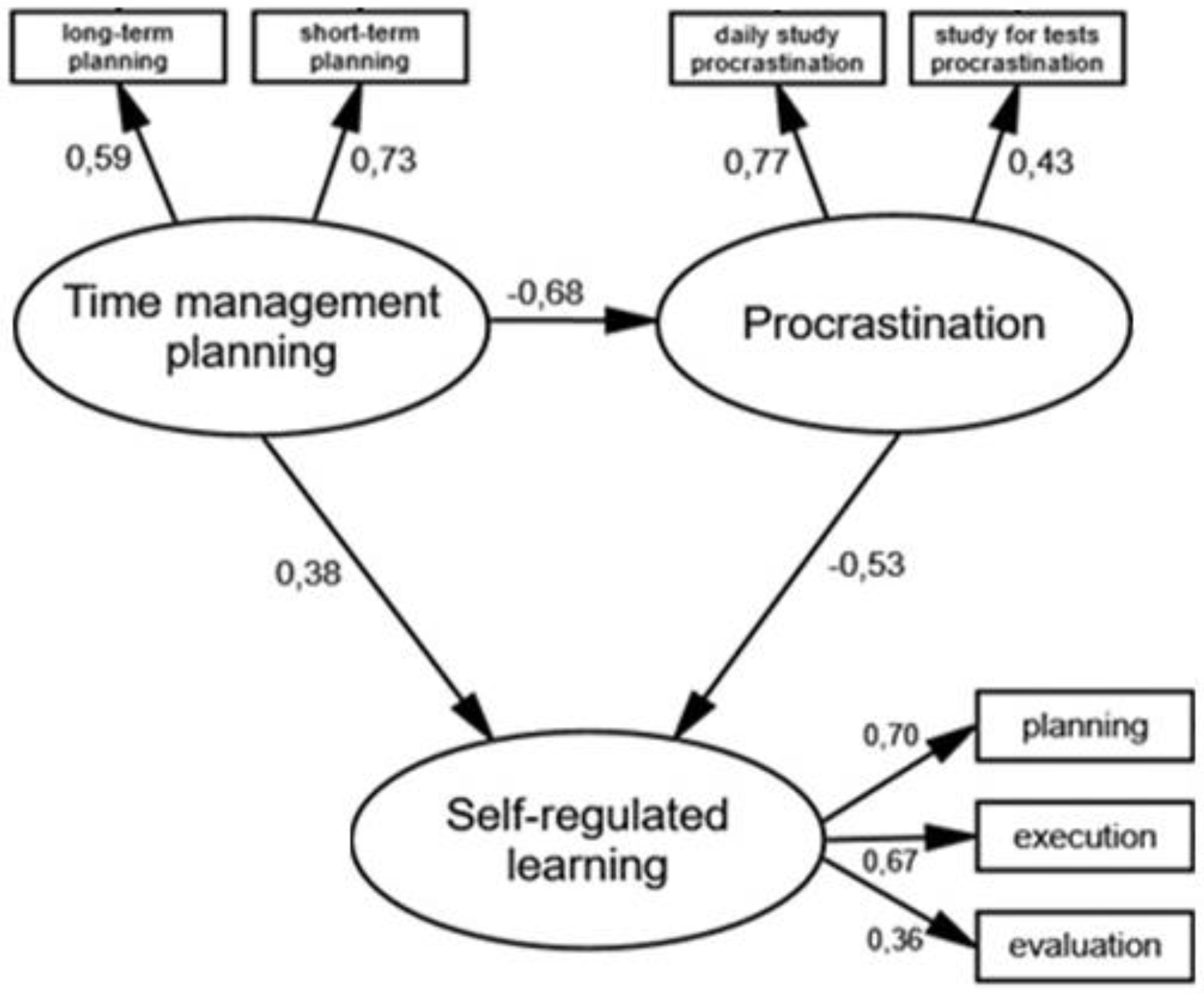

Analysis of

Figure 1 and

Table 2 confirms the formulated hypotheses with statistical significance. Therefore, students who dedicate more time to planning and managing their school activities are more self-regulated in their learning process (β = 0.38;

p < 0.001) and tend to procrastinate less, both in daily study and test preparation (β = -0.68;

p < 0.001). In contrast, students with a greater tendency for procrastination are less likely to be self-regulated in their learning (β = -0.53;

p < 0.001).

About the variances explained by the constructs, the squared multiple correlations (η²) reveal that self-regulation of learning is directly explained by academic time management planning and indirectly by procrastination in about 70% (η² = 0.689). Conversely, procrastination is directly explained by academic time management planning in approximately 47% (η² = 0.466). Both values illustrate the explanatory solid capacity of the proposed model.

An additional analysis was performed to assess the strength and direction of the linear relationship between the variables (

Table 3). The relationship between two variables arises when a change in one leads to a change in the other, which can be measured using Pearson's linear correlation coefficient (r). Considering the variables in the model, all variables showed statistically significant associations. However, these can range from very low (r < 0.200), low (r= 0.200 to 0.399), and moderate (r= 0.400 to 0.699). This suggests an evident cohesion among the variables studied. The most relevant and moderate associations are found between the dimensions of self-regulation of learning, planning and execution (r= 0.463;

p < 0.01), between the short- and long-term dimensions of academic time management planning (r= 0.433;

p<0.01), and between the planning dimension of self-regulation of learning and daily study procrastination (r = -0.420;

p < 0.01), the latter being negative.

5. Discussion

Regarding H1, the results prove it, so students who show more planning of academic time management, both in the short and long term, tend to have higher levels of self-regulation of learning. Thus, this study's results indicate that academic time management planning positively influences students' self-regulation of learning processes. This result aligns with previous studies [

1,

22]. We can interpret this study’s results as meaning that time management in school activities is a purpose-orientated process that includes students' ability to evaluate their time use, set goals, plan their studies, and thus achieve the proposed objectives. As a result of these efforts, students become more self-regulated in their learning. Time management between school tasks and subjects is fundamental to promoting efficient learning.

In the present study, the items with the highest scores on this scale reflect perceptions such as "what I do today determines what will happen to me tomorrow" and "I am clear about the grades I want to achieve in the next term," underscoring the importance of this connection. However, the question with the lowest score, "I make a daily list of the things I need to do," reveals that self-regulation of learning strategies for managing school time needs a more guiding role in school activities. It is, therefore, essential to understand students and be able to implement approaches and strategies adapted to their specific needs to help them organize their studies and plan their school time effectively. Lourenço and Paiva [

7] also emphasize that the distinction between successful and unsuccessful students is linked to variables such as the structuring of academic time, study methods and the correlation between performance and effort. Thus, time management should be considered essential for efficient and successful learning.

The Marcílio et al. [

22] study clarifies this issue, emphasizing how proper time planning is positively associated with students' self-discipline and motivational control. The ability to anticipate the temporal demands of academic activities and adopt strategies to avoid procrastination are crucial elements underpinning effective learning self-regulation. Also, Thibodeaux et al. [

11] suggest that high-performing students tend to set clear goals, estimate the time needed to complete tasks and maintain a rigorous study routine both in the short and long term. They frequently evaluate learning progress, reducing the negative impact of continuously postponing their school activities. Thus, time management goes beyond merely allocating study hours and includes the quality and depth of involvement in school activities. Conscientious planning allows students to focus on meeting deadlines and understanding content in depth, thus promoting meaningful learning.

This study's results reveal that procrastination negatively impacts the students' self-regulation of the learning process, corroborating H2. This detrimental effect manifests in the decreased capacity for self-discipline and efficient time management, intensifying students' challenges in achieving academic excellence. So, procrastination emerges as an obstacle in students' self-regulation of learning processes, impairing their academic performance. This can occur when students experience excessive fear of error or failure, preventing them from completing their work and procrastinating more, directly impacting learning behavior. In this study, the items "not keeping up with the material because I don't study daily" and "interrupting study to engage in other activities (such as watching TV, listening to music, talking on the phone)" are particularly noteworthy, supporting the findings of Silva et al. [

25]. These authors emphasize that procrastination is evident in various daily tasks and environments, with the continual postponement of school tasks being particularly significant.

According to Júnior et al. [

26], procrastination generates multiple problems and adverse effects individually and collectively: reduced performance, increased stress, negative impacts on physical and mental health, and a waste of resources. The authors emphasize that the crucial elements for understanding and combating procrastination lie in the concepts of self-efficacy and self-regulated learning, which significantly influence students' motivation, behavior and habits.

Although the item "when the teacher assigns a task in the classroom, I don't start it immediately" was the least scored by students, this indicates that, in the presence of academic procrastination behaviors, there may be a failure in the process of self-regulated learning, affecting the student's ability to manage their performance and meet school requirements. Such procrastinator behaviors tend to emerge more frequently when the intensity and difficulty of demands increase [

27]. The most cited reasons for procrastination include poor time management, an unfavorable environment, difficulty concentrating, anxiety about assessments, dysfunctional beliefs, fear of failure, low frustration tolerance, and difficulty executing tasks [

28]. So, procrastination hinders students' ability to set clear goals, plan effectively, and remain focused on school activities, negatively impacting their learning regulation. Therefore, it is urgent to implement effective intervention strategies, highlighting the importance of raising awareness of procrastination and encouraging more productive work habits. The educational community can significantly improve students' ability to self-regulate their learning processes and, as a result, their academic performance by tackling this phenomenon.

Regarding H3, the results show that students who dedicate time to planning their academic activities, both short-term and long-term, demonstrate a lesser tendency to procrastinate tasks, in line with the Valente et al. [

3] study. Academic time management planning in school activities, both the short and long term, corresponds to students' ability to evaluate the use of their time, set goals, plan studies and thus achieve the proposed objectives. Procrastination is associated with difficulty concentrating and the absence of a favorable study environment, which leads to constant interruptions and the postponement of tasks, resulting in the dispersion of attention and neglect of the preparation needed to achieve learning objectives. So, the results show that students with more time management planning tend to procrastinate less in their schoolwork. Thus, following appropriate methodologies, students develop satisfactory study practices marked by efficient organization and meticulous planning of learning, which means they are less prone to school procrastination.

In an integrative view of the three constructs being analyzed, it becomes clear that students' ability to self-regulate their learning is closely linked to effective academic time management and procrastination. Thus, it becomes increasingly important to identify the variables that define the framework of understanding where self-regulated learning occurs, as this is a crucial concept for achieving more profound and meaningful learning approaches. This observation assumes that students with self-regulated learning are aware of learning strategies and apply them appropriately, avoiding procrastination. Thus, these students contemplate their learning process and have strategies to monitor, control, and intervene in their behavior to achieve the desired academic success.

5.1. Implications for Theory and Practice

Regarding theoretical implications, this study reinforces socio-cognitive theories that consider self-regulation of learning to be a process that integrates cognitions, emotions, and behaviors. The results emphasize the essential role of planning academic time in supporting self-regulation processes. It also confirms theories that highlight procrastination as maladaptive behavior, which harms students' self-regulation abilities and underscores the importance of strategies to combat it.

About practical implications based on the results, the following are emphasised: Schools should integrate time management training programs to enhance self-regulation and reduce procrastination; Specific strategies for short- and long-term task planning should be taught to students, helping them organize their school goals; Teachers should be trained to recognize procrastination signs and apply teaching methods that promote student initiative; and Educational campaigns should address the effects of procrastination, emphasizing practical strategies to combat it.

5.2. Limitations and Future Studies

The proposed model identifies key variables influencing students' self-regulation in the learning process; however, future research should aim to expand the sample size and adopt a multilevel study approach. Furthermore, the data was collected using self-report questionnaires, which may not provide adequate real-time responses in the context of teaching and learning processes. Therefore, future studies should utilize qualitative methodologies like interviews or focus groups to examine self-regulation of learning among students with a history of success and failure to compare potential disparities. This study's results reveal a solid explanatory variance. However, other variables should be analyzed in future studies. For example, personal variables (e.g., motivation, anxiety, stress) and contextual variables (e.g., social environment, physical environment). Additional limitations relate to the sample size and the fact that it only included students from public schools in the northern part of the country. It is suggested that future studies have a larger sample and include students from different country regions, including private and public schools.

6. Conclusions

A thorough examination of the literature highlights the urgent need to explore predictive factors influencing students' self-regulation of learning. Thus, the present study aimed to understand how academic time management planning and procrastination influence the self-regulation of learning. Results indicate that students with more academic time management planning tend to be more self-regulated in learning; those with more procrastination tend to be less self-regulated, and those with more time management planning tend to procrastinate less. Therefore, assessing how we manage time in school activities presents relevant challenges as it directly affects students' engagement in the educational process. Furthermore, it is imperative to combat the school scourge of procrastination, perceived as harmful and capable of triggering a dangerous cycle with severe consequences, including low academic performance.

Knowing and understanding the variables influencing the learning process is essential to achieving students' academic success [

3]. Thus, this study indicates how time management planning and procrastination influence the self-regulation of learning. The connection between these variables is essential for accomplishing Goal 4 “Quality Education: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, thus promoting quality education.

In summary, this study highlights the need for a comprehensive understanding of the elements involved in the learning process to improve teaching quality and develop autonomous, competent students. The theoretical and practical implications of the present study can serve as a basis for developing more effective educational practices and formulating policies that encourage high-quality, sustainable, self-regulated learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.L., M.O.P. and S.V.; Methodology, S.V., A.A.L. and S.D.L.; Software, S.V., A.A.L. and SDL; Validation, S.V., A.A.L, M.O.P., H.O. and S.D.L.; Formal analysis, S.V., A.A.L, S.D.L., H.O., L.C. and F.R.; Investigation, S.V., A.A.L. and S.D.L.; Resources, A.A.L. and M.O.P; Data curation, S.V., A.A.L. and S.D.L.; Writing—original draft, S.V., A.A.L., M.O.P., S.D.L., H.O., L.C. and F.R.; Writing—review & editing, S.V., H.O., L.C. and F.R. The authors contributed equally to this work and have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Portalegre Polytechnic University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve any physical or psychological intervention with the students but only applied self-administered questionnaires that do not assess sensitive variables (violence, sexual behaviors, substance use, etc.) likely to mobilize the students emotionally. Therefore, it did not require Portalegre Polytechnic University ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lourenço, A.A.; Paiva, M.O.A. Self-regulation in academic success: exploring the impact of volitional control strategies, time management planning, and procrastination. Int. J. C. Edu. 2024, 1(3), 113-122. [CrossRef]

- PISA: O estado da nação em cinco gráficos. Available online: https://eco.sapo.pt/2023/12/05/pisa-o-estado-da-educacao-em-cinco-graficos/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Valente, S.; Dominguez-Lara, S.; Lourenço, A. Planning time management in school activities and relation to procrastination: A study for educational sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6883. [CrossRef]

- European Education Area: Removing barriers to learning and improving access to quality education for all. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Frison, L.M.B.; Boruchovitch, E. Autorregulação da aprendizagem: modelos teóricos e reflexões para a prática pedagógica. In Autorregulação da aprendizagem: cenários, desafios, perspectivas para o contexto educativo; Frison, L.M.B.; Boruchovitch E., Eds.; Vozes: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2020; pp. 17-30.

- Schunk, D.H.; Zimmerman, B.J. Self-regulation of learning and performance: Issues and educational applications; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, USA, 2023.

- Lourenço, A. A.; Paiva, M.O.A. Autorregulação da aprendizagem uma perspetiva holística 2016, 21, 33-51. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303766017.

- Fuentes, S.; Rosário, P.; Valdés, M.; Delgado, A.; Rodríguez, C. Autorregulación del aprendizaje: Desafío para el aprendizaje universitario autónomo. Rev. Lat. Educ. Inclusiva 2023, 17, 21-39. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educ. Res. J. 2008, 45, 166-183. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, A.A. Processos auto-regulatórios em alunos do 3.º Ciclo do Ensino Básico: Contributo da auto-eficácia e da instrumentalidade. Tese de doutoramento, Instituto de Educação e Psicologia/Universidade do Minho, Braga, 2008. https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/handle/1822/7631.

- Thibodeaux, J.; Deutsch, A.; Kitsantas, A.; Winsler, A. First-year college students’ time use. J. Adv. Academics 2017, 28, 5-27. https://doiorg.libproxy.cortland.edu/10.1177/1932202X16676860.

- Lourenço, A.A.; Paiva, M.O.A. Academic performance of excellence: The impact of self-regulated learning and academic time management planning. Knowledge 2024, 4, 289-301. [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A.; Schwartz, B.L.; Brown, V. Motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: Does metacognition play a role? In Educational psychology handbook series. Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance, 2nd ed.; Schunk, D. H.; Greene, J.A., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, USA, 2018; pp. 64-82. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Why assessing and improving executive functions early in life is critical. In Executive function in preschool-age children: Integrating measurement, neurodevelopment and translational research; Griffin, J.A.; McCardle, P.; Freund, L.S., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, USA, 2016; pp. 11-43. [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H.; Dent, A.L. Developmental trajectories of skills and abilities relevant for self-regulation of learning and performance. In Educational psychology handbook series. Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance, 2nd ed.; Schunk, D.H; Greene, J. A., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, USA, 2018; pp. 49-63. [CrossRef]

- Usher, E.L.; Schunk, D.H. Social cognitive theoretical perspective of self- regulation. In Educational psychology handbook series. Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance, 2nd ed.; Usher, E.L.; Schunk D. H., Eds.; Routledge/ Taylor & Francis Group: New York, USA, 2018; pp. 19-35. [CrossRef]

- Zachariou, A.; Whitebread, D. Developmental differences in young children's self- regulation. J. App. Dev. Psychology 2019, 62, 282-293. [CrossRef]

- Casiraghi, B.; Boruchovitch, E.; Almeida, L.S. Crenças de autoeficácia, estratégias de aprendizagem e o sucesso acadêmico no Ensino Superior. Rev. E-Psi 2020, 9, 27-38. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341123869.

- Matta, C.M.B.D. Influência das vivências acadêmicas e da autoeficácia na adaptação, rendimento e evasão de estudantes nos cursos de engenharia de uma instituição privada. Tese de doutoramento, Universidade Metodista de São Paulo, São Paulo – Brasil, 2019. https://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/METO_4085ec4cae669f4b052491cae9b74ca7.

- Noro, L.R.A.; Moya, J.L.M. Condições sociais, escolarização e hábitos de estudo no desempenho acadêmico de concluintes da área da saúde. Trab., Educ. e Saúde 2019, 17, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Teles, E.C.; Campana, A.; Costa, S.; Nascimento, F. O ensino remoto e os impactos nas aprendizagens. Rev. Com Sertões 2020, 9, 72-90. https://www.revistas.uneb.br/index.php/comsertoes/article/view/10091.

- Marcilio, F.C.P.; Blando, A.; Rocha, R.Z.; Dias, A.C.G. Guia de técnicas para a gestão do tempo de estudos: relato da construção. Psic.: Ciên. e Prof. 2021, 41, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- KS, V.M.; Rajkumar, E.; Lakshmi, R.; John, R.; Sunny, S.M.; George, A.J.; Pawar, S.; Abraham, J. Influence of decision-making styles and affective styles on academic procrastination among students. C. Educ. 2023, 10, 2203598. [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.S.; Reis, H.L.; Lima, V.L.M.C.; de Souza, E.T.; de Oliveira, C.F.; Chirinéa, G. Eficácia de intervenções não medicamentosas em procrastinação acadêmica: Revisão integrativa. Mos.: Est. em Psic. 2022, 10, 25-47. https://periodicos.ufmg.br/index.php/mosaico/article/view/33957.

- Silva, L.S.; Bernardes, J.R.; Nascimento, J.C.H.B.; Veras, S.L.L.; Castro, M.M.B. As relações entre o desempenho acadêmico e a procrastinação: Um estudo exploratório com acadêmicos dos cursos de graduação em ciências contábeis e administração do piauí. Cont. V. & Ver. 2022, 33, 115-143. [CrossRef]

- Júnior, J.F.C.; Bezerra, D.D.M.C.; de Araújo, A.G.; Ramos, A.S.M. Anti-procrastination strategies, techniques and tools and their interrelation with self-regulation and self-efficacy. J. Educ. and Learning 2024, 13, 72-91. [CrossRef]

- Machado, B.A.B.; Schwartz, S. Procrastinação e aprendizagem acadêmica. Rev. El. Cien. UERGS 2018, 4, 119-135. [CrossRef]

- Fior, C.A.; Sampaio, R.K.N.; do Carmo Reis, C.A.; Polydoro, S.A.J. Autoeficácia e procrastinação acadêmica em estudantes do ensino superior. Psico 2022, 53, e38943-e38943. [CrossRef]

- Furlan, L.A.; Martínez- Santos, G. Intervención en un caso de ansiedad ante exámenes, perfeccionismo desadaptativo y procrastinación. Rev. Dig. Inv. Docencia Univ. 2023, 17, e1633. [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P.; Lourenço, A.; Paiva, M.O.; Núñez, J.C.; González-Pienda, J.; Valle, A. In Avaliação Psicológica. Instrumentos validados para a população portuguesa. Inventário de processos de autorregulação da aprendizagem; Gonçalves M.M.; Simões M.R.; Almeida L.S.; Machado, C., Eds.; Almedina: Coimbra, Portugal, 2010; pp. 159-174.

- Rosário, P.; Costa, M.; Núñez, J.C.; González-Pienda, J.; Solano, P.; Valle, A. Academic procrastination: Associations with personal, school and family variables. The Span. J. of Psy. 2009, 12, 118-127. [CrossRef]

- Helsinki Declaration. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191-2194. [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. IBM®, SPSS®, Amos™ 29 User’s Guide. IBM: USA, 2022. https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB_29.0.0/pdf/IBM_SPSS_Amos_User_Guide.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).