Submitted:

05 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

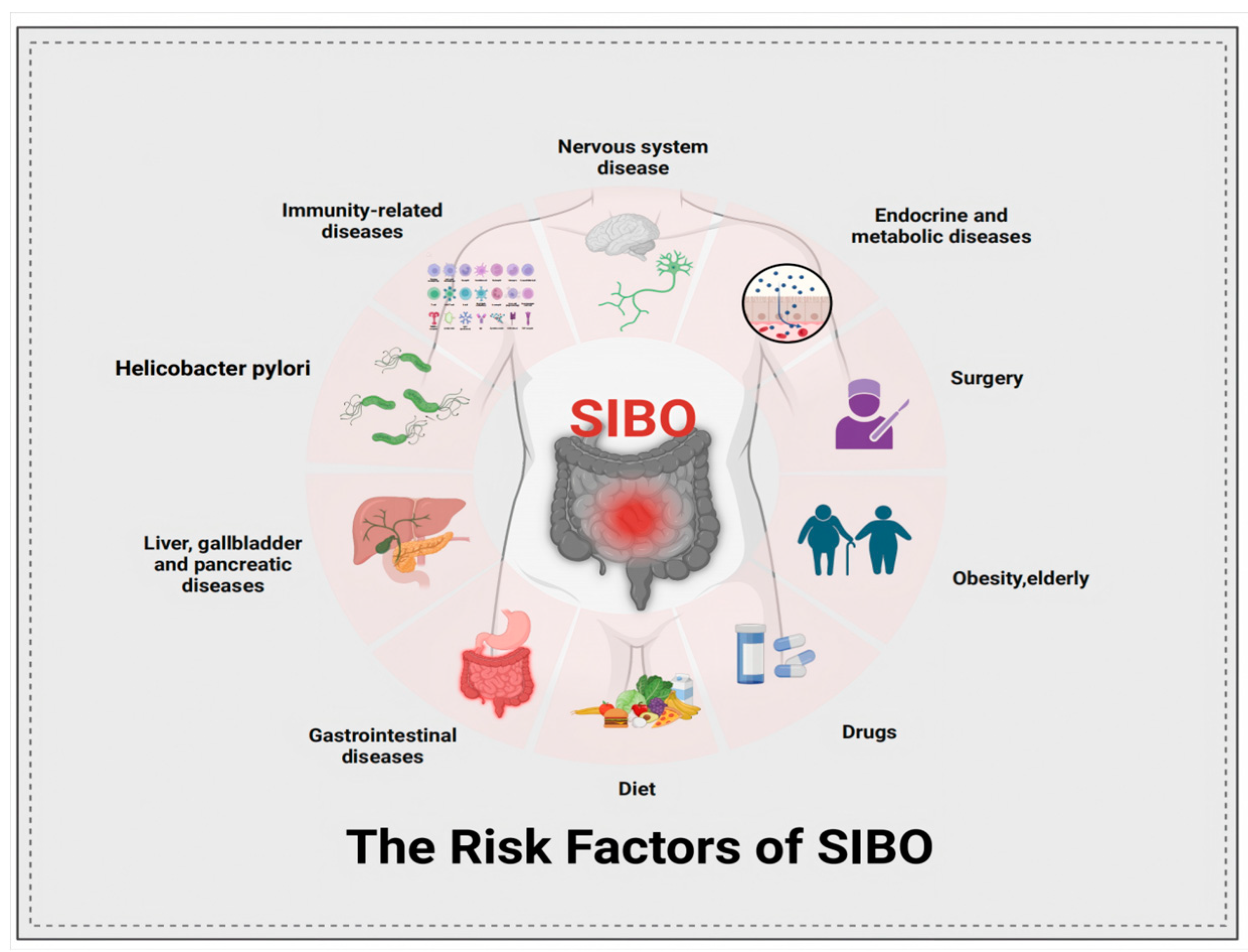

2. Pathophysiology and Influence on SIBO

2.1. The Pathophysiology of SIBO

2.1.1. Abnormalities in GI Structure and Motility

2.1.2. Dysfunction of Gut Defense and Immunity Regulation

2.1.3. Drug, Diseases and Other

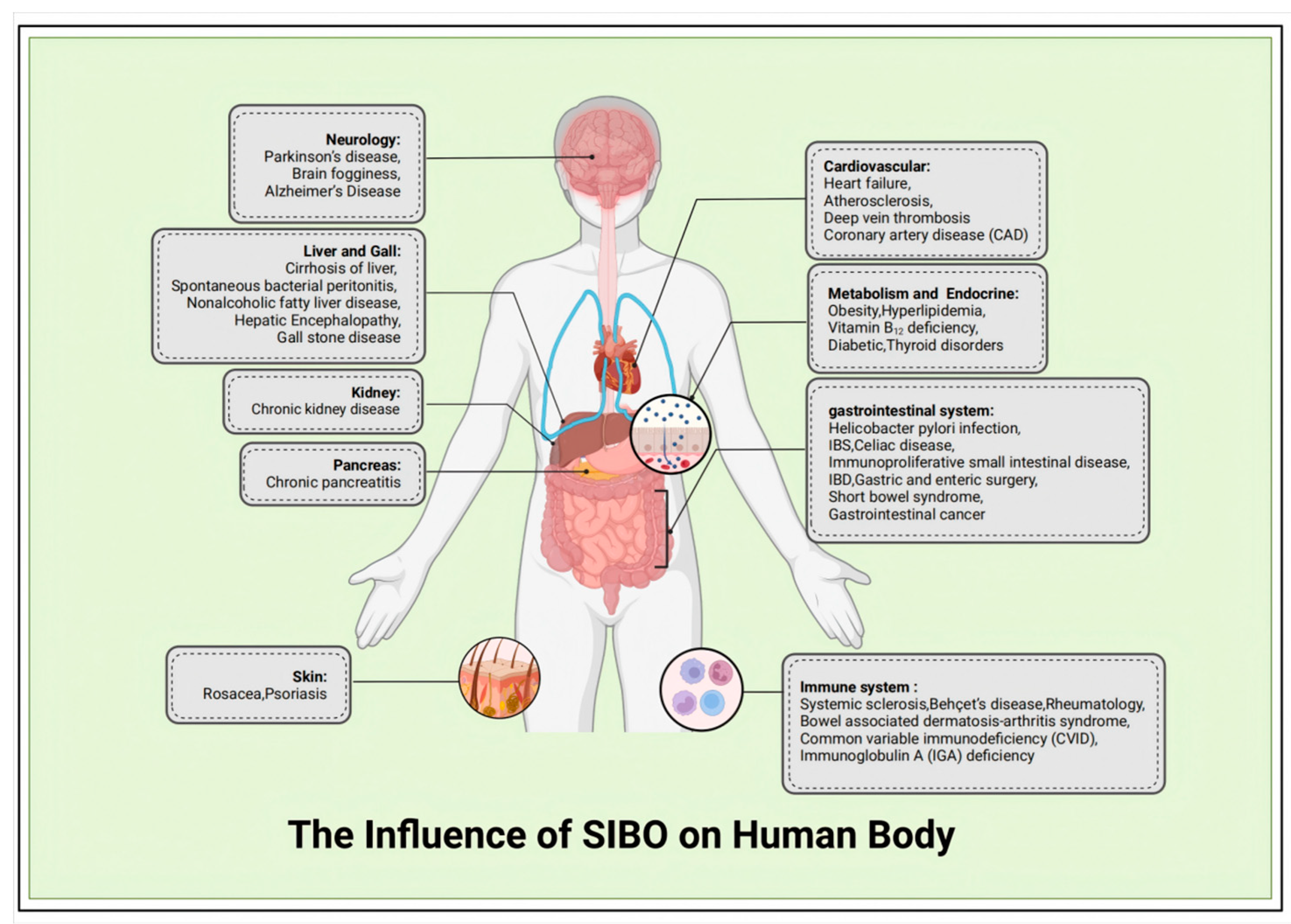

2.2. The Influence of SIBO on Human Body

3. The Diagnosis of SIBO and Current Challenges

3.1. Duodenal/Jejunal Fluid Aspirate Culture

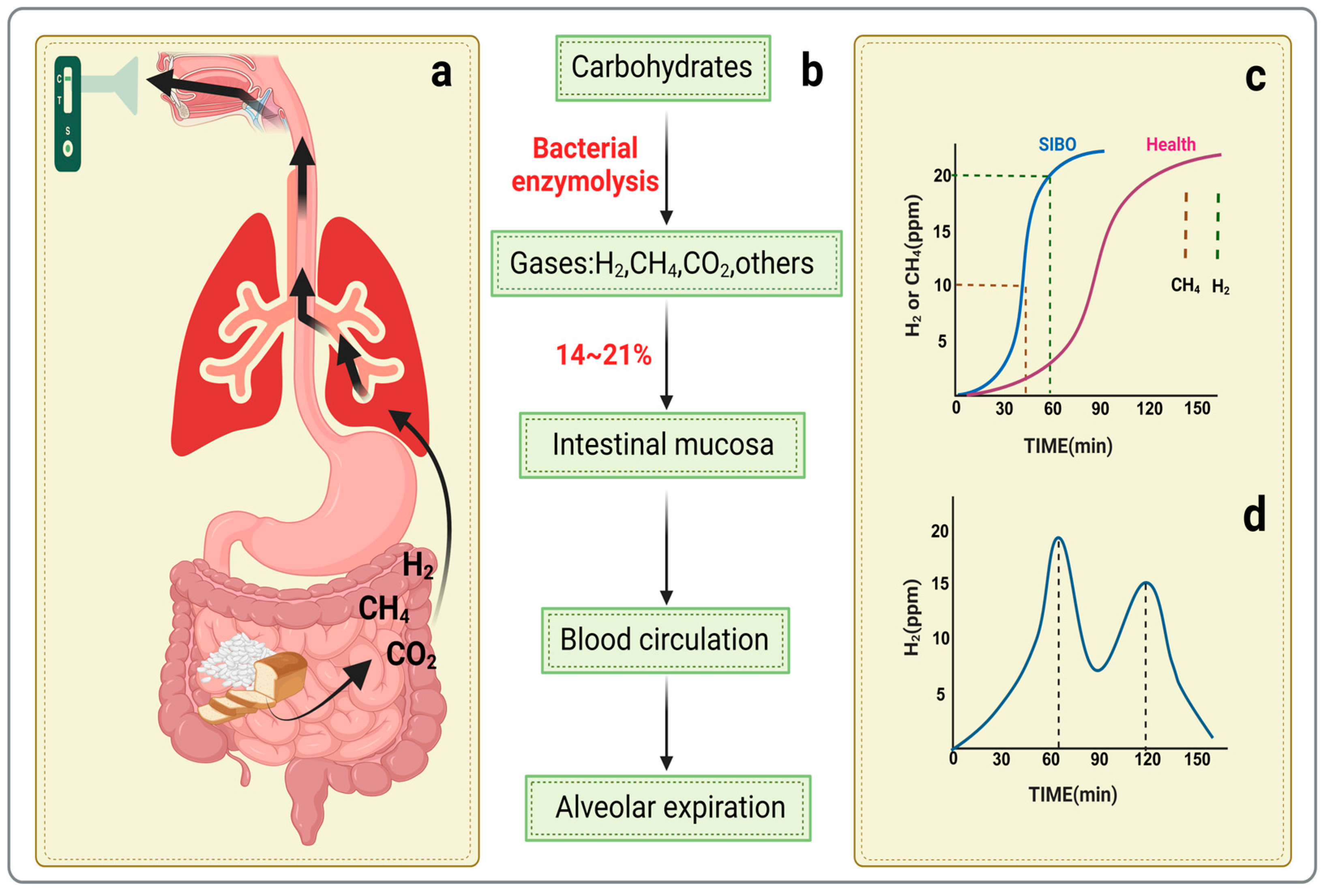

3.2. Hydrogen Breath Tests

3.3. Methane Breath Tests

3.4. More New Testing Methods of SIBO

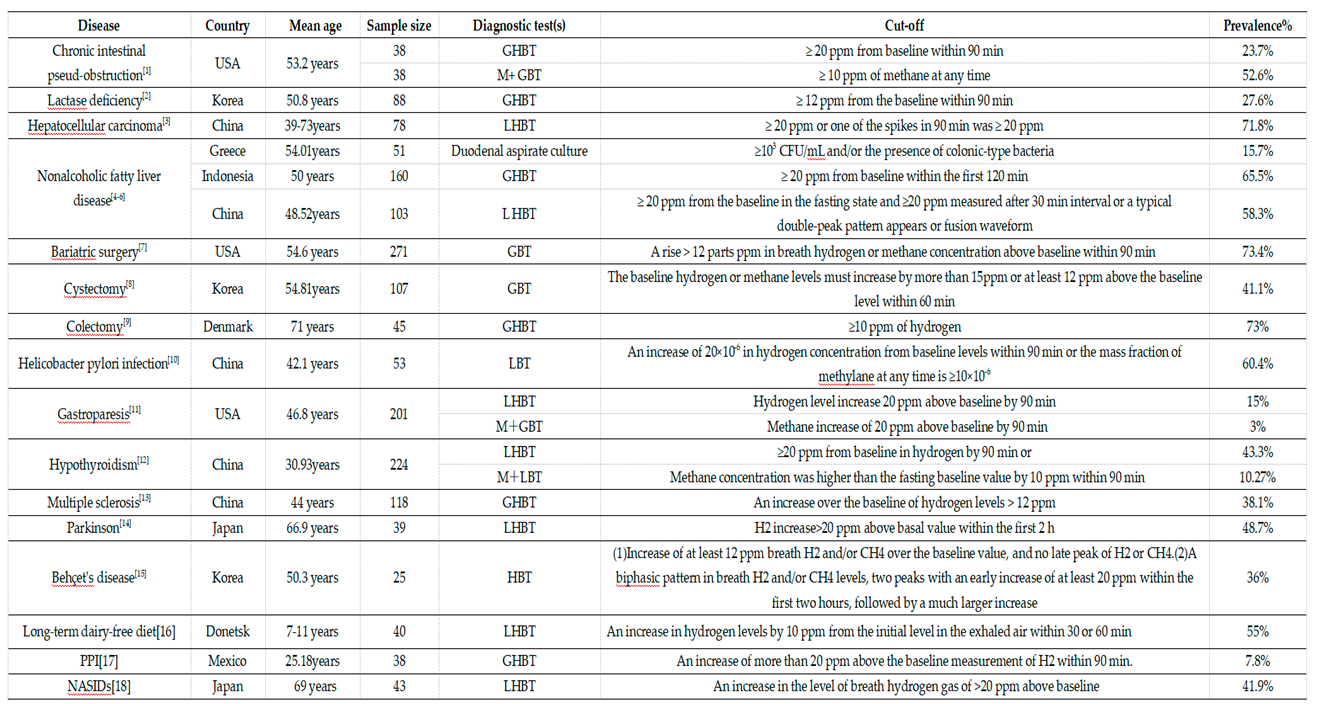

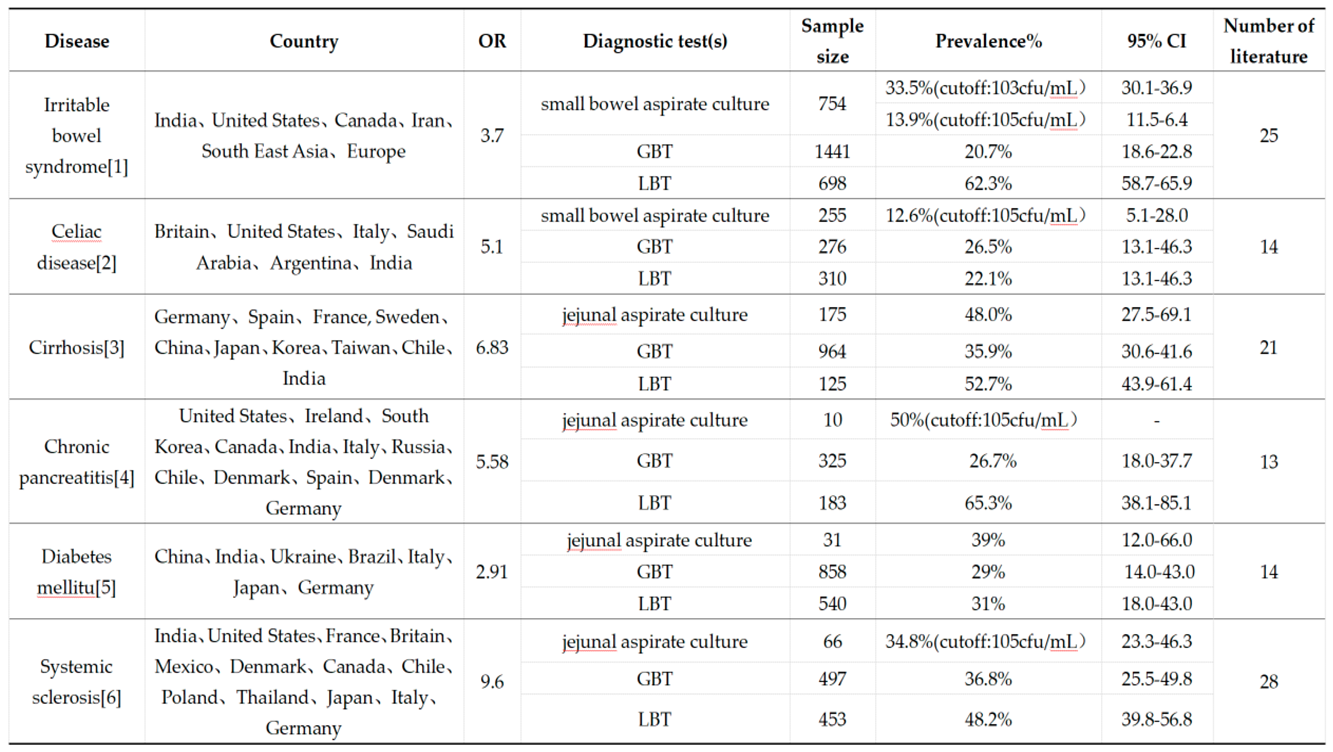

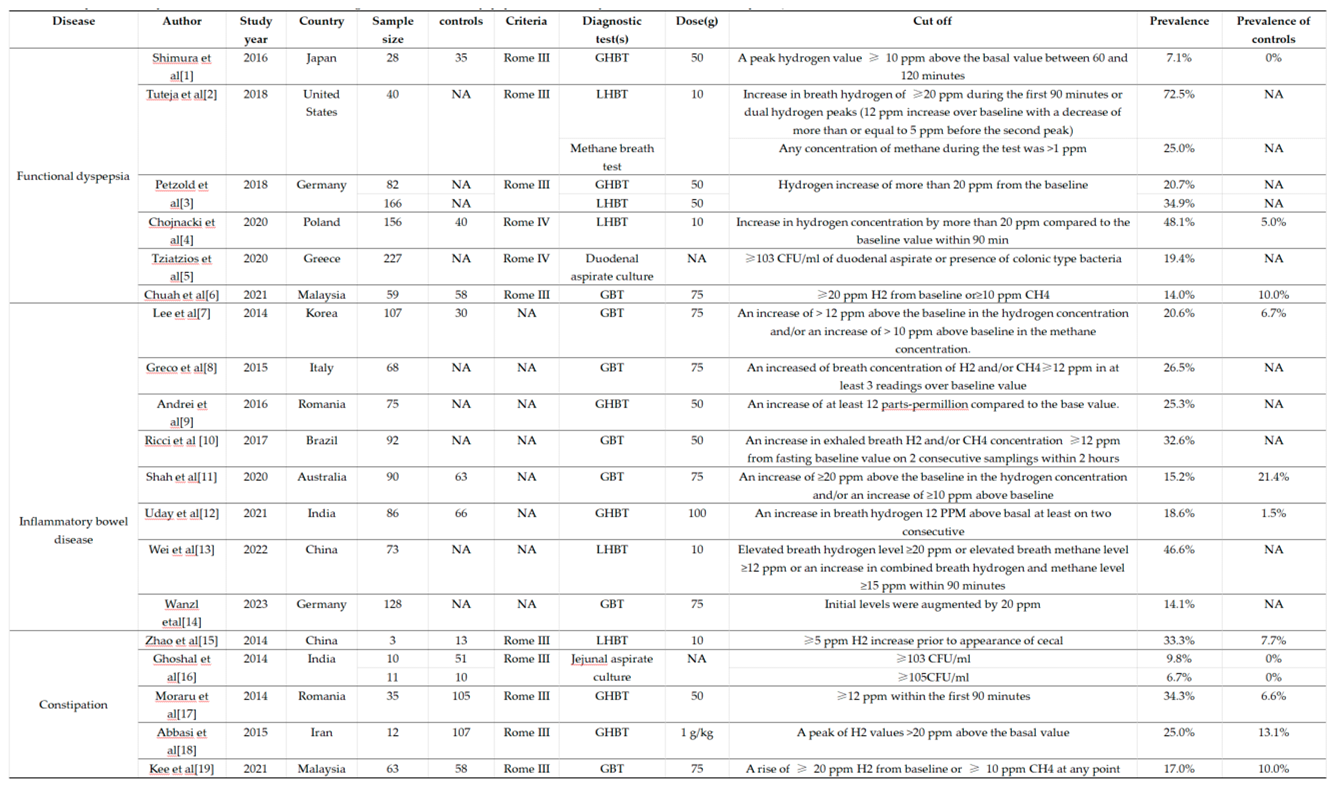

4. Diverse Influences Associated with SIBO

4.1. Dietary Standards Vary Before the Methane-Hydrogen Breath Test

4.2. No Standard Diagnostic Methods

4.3. Sensitivity and Specificity of Diagnosis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SIBO | small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

| GIT | gastrointestinal tract |

| BAs | bile acids |

| ILCs | lymphoid cells |

| SCFA | short-chain fatty acid |

| CAZymes | carbohydrate-active enzymes |

| SBTT | small bowel transit time |

| LBT | lactulose breath test |

| GBT | glucose breathtest |

| CD | Crohn's disease |

| RYGBS | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery |

| PPIs | proton pump inhibitors |

| HP | Helicobacter pylori |

| CP | chronic pancreatitis |

| FD | functional dyspepsia |

| IBS | irritable bowel syndrome |

| UC | ulcerative colitis |

| MAFLD | metabolic-associated fatty liver |

| NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| MBT | methane breath testing |

| HBT | hydrogen breath test |

| IMO | intestinal methane producing bacteria overgrowth |

| SMM | single fasting breath methane measurement |

| SCBDS | Smart Capsule Bacteria Detection System |

| TBC | total bacterial count |

| ScLBT | scintigraphy-lactulose hydrogen breath test |

| OCTT | orocecal transit times |

| NCT | radiation-free nutrient challenge test |

| FODMAP | fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols |

References

- de Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, C.; Hendry, C.; Farley, A.; McLafferty, E. The digestive system: part 1. Nurs. Stand. 2014, 28, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Gordon, J.I. Commensal Host-Bacterial Relationships in the Gut. Science 2001, 292, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijay, A.; Valdes, A.M. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Role of the gut microbiome in chronic diseases: a narrative review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 76, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.L.; Weir, T.L. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science 2018, 362, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaiss, C.A.; et al. The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature 2016, 535, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.T.; Leite, G.; Romano, A.E.; Sedighi, R.; Chang, C.; Celly, S.; Rezaie, A.; Mathur, R.; Pimentel, M.; Ismagilov, R.F. Quantitative sequencing clarifies the role of disruptor taxa, oral microbiota, and strict anaerobes in the human small-intestine microbiome. Microbiome 2021, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, J.M.; Schellekens, R.C.A.; van Rieke, H.M.; Wanke, C.; Iordanov, V.; Stellaard, F.; Wutzke, K.D.; Dijkstra, G.; van der Zee, M.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; et al. Gastrointestinal pH and Transit Time Profiling in Healthy Volunteers Using the IntelliCap System Confirms Ileo-Colonic Release of ColoPulse Tablets. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0129076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiela, P.R.; Ghishan, F.K. Physiology of Intestinal Absorption and Secretion. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLOS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, A.; Takagi, T.; Okayama, T.; Katada, K.; Uchiyama, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Handa, O.; Itoh, Y.; Nakagawa, M.; Naito, Y.; et al. Higher Levels of Streptococcus in Upper Gastrointestinal Mucosa Associated with Symptoms in Patients with Functional Dyspepsia. Digestion 2020, 101, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seekatz, A.M.; Schnizlein, M.K.; Koenigsknecht, M.J.; Baker, J.R.; Hasler, W.L.; Bleske, B.E.; Young, V.B.; Sun, D. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of the Stomach and Small-Intestinal Microbiota in Fasted Healthy Humans. mSphere 2019, 4, e00126-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalon, D.; Culver, R.N.; Grembi, J.A.; Folz, J.; Treit, P.V.; Shi, H.; Rosenberger, F.A.; Dethlefsen, L.; Meng, X.; Yaffe, E.; et al. Profiling the human intestinal environment under physiological conditions. Nature 2023, 617, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Gao, R.; Wu, X.; Sun, J.; Wan, J.; Wu, T.; Fichna, J.; Yin, L.; Chen, C. Characterization of Specific Signatures of the Oral Cavity, Sputum, and Ileum Microbiota in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 864944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.-F.; Liang, S.-P.; Zhong, Z.-S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Liu, J.-B.; Huang, S.-P. Duodenal microbiota makes an important impact in functional dyspepsia. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 162, 105297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmora, N.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Suez, J.; Mor, U.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Bashiardes, S.; Kotler, E.; Zur, M.; Regev-Lehavi, D.; Brik, R.B.-Z.; et al. Personalized Gut Mucosal Colonization Resistance to Empiric Probiotics Is Associated with Unique Host and Microbiome Features. Cell 2018, 174, 1388–1405.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Hong, G.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Qian, W.; Xiong, H.; Bai, T.; Song, J.; Hou, X. Duodenal and rectal mucosal microbiota related to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 35, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.-X.; Huang, C.-L.; Luo, S.-Z.; Zhang, X.-M.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, Y.-Y. Characterization of the duodenal bacterial microbiota in patients with pancreatic head cancer vs. healthy controls. Pancreatology 2018, 18, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Zai, H.; Fukui, Y.; Kato, Y.; Kumade, E.; Watanabe, T.; Furusyo, N.; Nakajima, H.; Arai, K.; Ishii, Y.; et al. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on fluid duodenal microbial community structure and microbial metabolic pathways. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiepatti, A.; Bacchi, S.; Biagi, F.; Panelli, S.; Betti, E.; Corazza, G.R.; Capelli, E.; Ciccocioppo, R. Relationship between duodenal microbiota composition, clinical features at diagnosis, and persistent symptoms in adult Coeliac disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panelli, S.; Capelli, E.; Lupo, G.F.D.; Schiepatti, A.; Betti, E.; Sauta, E.; Marini, S.; Bellazzi, R.; Vanoli, A.; Pasi, A.; et al. Comparative Study of Salivary, Duodenal, and Fecal Microbiota Composition Across Adult Celiac Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Fuhrer, T.; Morgenthaler, D.; Krupka, N.; Wang, D.; Spari, D.; Candinas, D.; Misselwitz, B.; Beldi, G.; Sauer, U.; et al. Plasticity of the adult human small intestinal stoma microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1773–1787.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoetendal, E.G.; Raes, J.; van den Bogert, B.; Arumugam, M.; Booijink, C.C.G.M.; Troost, F.J.; Bork, P.; Wels, M.; De Vos, W.M.; Kleerebezem, M. The human small intestinal microbiota is driven by rapid uptake and conversion of simple carbohydrates. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Repiso, C.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Martín-Núñez, G.M.; Ho-Plágaro, A.; Rodríguez-Cañete, A.; Gonzalo, M.; García-Fuentes, E.; Tinahones, F.J. Mucosa-associated microbiota in the jejunum of patients with morbid obesity: alterations in states of insulin resistance and metformin treatment. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonaesch, P.; Araújo, J.R.; Gody, J.-C.; Mbecko, J.-R.; Sanke, H.; Andrianonimiadana, L.; Naharimanananirina, T.; Ningatoloum, S.N.; Vondo, S.S.; Gondje, P.B.; et al. Stunted children display ectopic small intestinal colonization by oral bacteria, which cause lipid malabsorption in experimental models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, G.G.S.; Weitsman, S.; Parodi, G.; Celly, S.; Sedighi, R.; Sanchez, M.; Morales, W.; Villanueva-Millan, M.J.; Barlow, G.M.; Mathur, R.; et al. Mapping the Segmental Microbiomes in the Human Small Bowel in Comparison with Stool: A REIMAGINE Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 2595–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agamennone, V.; Abuja, P.M.; Basic, M.; De Angelis, M.; Gessner, A.; Keijser, B.; Larsen, M.; Pinart, M.; Nimptsch, K.; Pujos-Guillot, E.; et al. HDHL-INTIMIC: A European Knowledge Platform on Food, Diet, Intestinal Microbiomics, and Human Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushyhead, D.; Quigley, E.M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth—Pathophysiology and Its Implications for Definition and Management. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittipo, P.; Shim, J.-W.; Lee, Y.K. Microbial Metabolites Determine Host Health and the Status of Some Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yersin, S.; Vonaesch, P. Small intestinal microbiota: from taxonomic composition to metabolism. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 970–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Wong, M.H.; Thelin, A.; Hansson, L.; Falk, P.G.; Gordon, J.I. Molecular Analysis of Commensal Host-Microbial Relationships in the Intestine. Science 2001, 291, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folz, J.; Culver, R.N.; Morales, J.M.; Grembi, J.; Triadafilopoulos, G.; Relman, D.A.; Huang, K.C.; Shalon, D.; Fiehn, O. Human metabolome variation along the upper intestinal tract. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Guryn, K.; Hubert, N.; Frazier, K.; Urlass, S.; Musch, M.W.; Ojeda, P.; Pierre, J.F.; Miyoshi, J.; Sontag, T.J.; Cham, C.M.; et al. Small Intestine Microbiota Regulate Host Digestive and Absorptive Adaptive Responses to Dietary Lipids. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 458–469.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.R.; Tazi, A.; Burlen-Defranoux, O.; Vichier-Guerre, S.; Nigro, G.; Licandro, H.; Demignot, S.; Sansonetti, P.J. Fermentation Products of Commensal Bacteria Alter Enterocyte Lipid Metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 358–375.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Saad, R.J.; Long, M.D.; Rao, S.S.C. ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasbarrini, A.; Lauritano, E.C.; Gabrielli, M.; Scarpellini, E.; Lupascu, A.; Ojetti, V.; Gasbarrini, G. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Diagnosis and Treatment. Dig. Dis. 2007, 25, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.S. Ileocecal valve dysfunction in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A pilot study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 6801–6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vantrappen, G.; Janssens, J.; Hellemans, J.; Ghoos, Y. The Interdigestive Motor Complex of Normal Subjects and Patients with Bacterial Overgrowth of the Small Intestine. J. Clin. Investig. 1977, 59, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husebye, E.; Skar, V.; Høverstad, T.; Iversen, T.; Melby, K. Abnormal intestinal motor patterns explain enteric colonization with gram-negative bacilli in late radiation enteropathy. Gastroenterology 1995, 109, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, B.C.; Ciarleglio, M.M.; Clarke, J.O.; Semler, J.R.; Tomakin, E.; Mullin, G.E.; Pasricha, P.J. Small Intestinal Transit Time Is Delayed in Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 49, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, I.; Ducrotté, P.; Denis, P.; Menard, J.-F.; Levesque, H. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2009, 48, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojetti, V.; Pitocco, D.; Scarpellini, E.; Zaccardi, F.; Scaldaferri, F.; Gigante, G.; Gasbarrini, G.; Ghirlanda, G.; Gasbarrini, A. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth and type 1 diabetes. . 2010, 13, 419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Cohen, S.; Mehendiratta, V.; Mendoza, F.; Jimenez, S.A.; Dimarino, A.J.; Rattan, S. Effects of Scleroderma Antibodies and Pooled Human Immunoglobulin on Anal Sphincter and Colonic Smooth Muscle Function. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 1308–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.; Haberberger, R.V.; Gordon, T.P.; Jackson, M.W. Antibodies interfering with the type 3 muscarinic receptor pathway inhibit gastrointestinal motility and cholinergic neurotransmission in Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Matsumoto, I.; Nishimagi, E.; Satoh, T.; Kuwana, M.; Sumida, T.; Hara, M. Muscarinic-3 acetylcholine receptor autoantibody in patients with systemic sclerosis: contribution to severe gastrointestinal tract dysmotility. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritano, E.C.; Bilotta, A.L.; Gabrielli, M.; Scarpellini, E.; Lupascu, A.; Laginestra, A.; Novi, M.; Sottili, S.; Serricchio, M.; Cammarota, G.; et al. Association between Hypothyroidism and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 4180–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strid, H.; Simrén, M.; Stotzer, P.-O.; Ringström, G.; Abrahamsson, H.; Björnsson, E.S. Patients with Chronic Renal Failure Have Abnormal Small Intestinal Motility and a High Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Digestion 2003, 67, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; et al. Jejunal diverticulosis. A heterogenous disorder caused by a variety of abnormalities of smooth muscle or myenteric plexus. Gastroenterology 1983, 85, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Wallace, D.; Hallegua, D.; Chow, E.; Kong, Y.; Park, S.; Lin, H.C. A link between irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia may be related to findings on lactulose breath testing. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2004, 63, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.H.; Mahadeva, S.; Thalha, A.M.; Gibson, P.R.; Kiew, C.K.; Yeat, C.M.; Ng, S.W.; Ang, S.P.; Chow, S.K.; Tan, C.T.; et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson's disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2014, 20, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, J.L.; Okun, M.S.; Moshiree, B. The treatment of gastroparesis, constipation and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome in patients with Parkinson's disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2015, 16, 2449–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrone, P.; Sarkisyan, G.; Coloma, E.; Akopian, G.; Ortega, A.; Kaufman, H.S. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients With Lower Gastrointestinal Symptoms and a History of Previous Abdominal Surgery. Arch. Surg. 2011, 146, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaus, J.; Spaniol, U.; Adler, G.; A Mason, R.; Reinshagen, M.; C, C.v.T. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth mimicking acute flare as a pitfall in patients with Crohn's Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhani, S.V.; Shah, H.N.; Alexander, K.; Finelli, F.C.; Kirkpatrick, J.R.; Koch, T.R. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and thiamine deficiency after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in obese patients. Nutr. Res. 2008, 28, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, N.H. Paneth cell defensins and the regulation of the microbiome: detente at mucosal surfaces. Gut Microbes 2010, 1, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantis, N.J.; Forbes, S.J. Secretory IgA: Arresting Microbial Pathogens at Epithelial Borders. Immunol. Investig. 2010, 39, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, N.; Xie, J.; Li, D.; Shan, T.; Fan, L. Structural and quantitative alterations of gut microbiota in experimental small bowel obstruction. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0255651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M.; Neish, A.S. Recognition of bacterial pathogens and mucosal immunity. Cell. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignata, C.; Budillon, G.; Monaco, G.; Nani, E.; Cuomo, R.; Parrilli, G.; Ciccimarra, F. Jejunal bacterial overgrowth and intestinal permeability in children with immunodeficiency syndromes. . Gut 1990, 31, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.; Chan, W.W. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and the Risk of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Morrison, M.; Burger, D.; Martin, N.; Rich, J.; Jones, M.; Koloski, N.; Walker, M.M.; Talley, N.J.; Holtmann, G.J. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 49, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, L.; Foti, M.; Ruggia, O.; Chiecchio, A. Increased Incidence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth During Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.S.C.; Rehman, A.; Yu, S.; de Andino, N.M. Brain fogginess, gas and bloating: a link between SIBO, probiotics and metabolic acidosis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2018, 9, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslennikov, R.; Ivashkin, V.; Efremova, I.; Poluektova, E.; Kudryavtseva, A.; Krasnov, G. Gut dysbiosis and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth as independent forms of gut microbiota disorders in cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capurso, G.; Signoretti, M.; Archibugi, L.; Stigliano, S.; Fave, G.D. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in chronic pancreatitis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2016, 4, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucheryavyy, Y.A.; Andreev, D.N.; Maev, I.V.; Александрoвич, К.Ю. Prevalence of small bowel bacterial overgrowth in patients with functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Ter. arkhiv 2020, 92, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Nehra, A.; Mathur, A.; Rai, S. A meta-analysis on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with different subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 35, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Thite, P.; Hansen, T.; Kendall, B.J.; Sanders, D.S.; Morrison, M.; Jones, M.P.; Holtmann, G. Links between celiac disease and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 37, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A.; Shah, A.; Jones, M.P.; Koloski, N.; Talley, N.J.; Morrison, M.; Holtmann, G. Methane positive small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1933313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudan, A.; Jamioł-Milc, D.; Hawryłkowicz, V.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Stachowska, E. The Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Liver Diseases: NAFLD, NASH, Fibrosis, Cirrhosis—A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Ghoshal, U. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Other Intestinal Disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2017, 46, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, A.H.; Pimentel, M. Gastrointestinal bacterial overgrowth: pathogenesis and clinical significance. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2013, 4, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.C.; Zaidel, O.; Hum, S. Intestinal transit of fat depends on accelerating effect of cholecystokinin and slowing effect of an opioid pathway. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2002, 47, 2217–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannella, R.A.; Broitman, S.A.; Zamcheck, N. Influence of Gastric Acidity on Bacterial and Parasitic Enteric Infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 1973, 78, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, B.C.; Mullin, G.E.; Passi, M.; Zheng, X.; Salem, A.; Yolken, R.; Pasricha, P.J. A Prospective Evaluation of Ileocecal Valve Dysfunction and Intestinal Motility Derangements in Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 3525–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Shukla, R.; Ghoshal, U. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Bridge between Functional Organic Dichotomy. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.V.; Sharma, S.; Malik, A.; Kaur, J.; Prasad, K.K.; Sinha, S.K.; Singh, K. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Orocecal Transit Time in Patients of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 2594–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Brandimarte, G.; Giorgetti, G. High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in celiac patients with persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms after gluten withdrawal. Am J Gastroenterol 2003, 98, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, S.; Duseja, A.; Sharma, B.K.; Singla, B.; Chakraborti, A.; Das, A.; Ray, P.; Dhiman, R.K.; Chawla, Y. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and toll-like receptor signaling in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 31, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyger, G.; Baron, M. Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Scleroderma: Recent Progress in Evaluation, Pathogenesis, and Management. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2011, 14, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjogren, R.W. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1994, 37, 1265–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Tandon, P.; Gohel, T.; Corrigan, M.L.; Coughlin, K.L.; Shatnawei, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Kirby, D.F. Gastrointestinal Manifestations, Malnutrition, and Role of Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition in Patients With Scleroderma. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 49, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadpanich, K.; Soison, P.; Chunlertrith, K.; Mairiang, P.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Sangchan, A.; Suttichaimongkol, T.; Foocharoen, C. Prevalence and associated factors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth among systemic sclerosis patients. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 22, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.; De Palma, G.; Zou, H.; Bazzaz, A.H.Z.; Verdu, E.; Baker, B.; Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Khalidi, N.; Larché, M.J.; Beattie, K.A.; et al. Fecal microbiome differs between patients with systemic sclerosis with and without small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2021, 6, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chu, M.; Wang, D.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J. Risk factors for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. J. Med Microbiol. 2023, 72, 001666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvit, K.B.; Kharchenko, N.V.; Kharchenko, V.V.; Chornenka, O.I.; Chornovus, R.I.; Dorofeeva, U.S.; Draganchuk, O.B.; Slaba, O.M. THE ROLE OF SMALL INTESTINAL BACTERIAL OVERGROWTH IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF HYPERLIPIDEMIA. Wiadomosci Lek. (Warsaw, Pol. : 1960) 2019, 72, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, L.; Dumitrascu, D.L. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in endocrine diseases. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 121, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kim, C.J.; Go, Y.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, M.-G.; Oh, S.W.; Cho, W.Y.; Im, S.-H.; Jo, S.K. Intestinal microbiota control acute kidney injury severity by immune modulation. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodpoor, F.; Rahbar Saadat, Y.; Barzegari, A.; Ardalan, M.; Zununi Vahed, S. The impact of gut microbiota on kidney function and pathogenesis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 93, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; et al. Oral psoriasis and SIBO: is there a link? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018, 32, e368–e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Ciccarese, G.; Indemini, E.; Savarino, V.; Parodi, A. Psoriasis and small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Feng, X.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, Z. Association of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Pathog. 2021, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, G.; Su, S. Effect of Compound Lactic Acid Bacteria Capsules on the Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Depression and Diabetes: A Blinded Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 6721695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossewska, J.; Bierlit, K.; Trajkovski, V. Personality, Anxiety, and Stress in Patients with Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome. The Polish Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, C.; Konrad, P.; Błońska, A.; Medrek-Socha, M.; Przybylowska-Sygut, K.; Chojnacki, J.; Poplawski, T. Altered Tryptophan Metabolism on the Kynurenine Pathway in Depressive Patients with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, C.; Popławski, T.; Konrad, P.; Fila, M.; Błasiak, J.; Chojnacki, J. Antimicrobial treatment improves tryptophan metabolism and mood of patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Xu, L.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Z. Effect of probiotics on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 27, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; et al. Asian-Pacific consensus on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in gastrointestinal disorders: An initiative of the Indian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association. Indian J Gastroenterol 2022, 41, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshini, R.; Dai, S.-C.; Lezcano, S.; Pimentel, M. A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Tests for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007, 53, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanner, S. The small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Irritable bowel syndrome hypothesis: implications for treatment. Gut 2008, 57, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniewicz-Luzenczyk, K.; et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome in children. Prz Gastroenterol 2015, 10, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cangemi, D.J.; Lacy, B.E.; Wise, J. Diagnosing Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Comparison of Lactulose Breath Tests to Small Bowel Aspirates. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 66, 2042–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, G.; Morales, W.; Weitsman, S.; Celly, S.; Parodi, G.; Mathur, R.; Barlow, G.M.; Sedighi, R.; Millan, M.J.V.; Rezaie, A.; et al. The duodenal microbiome is altered in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0234906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamba, S.; Imai, T.; Sasaki, M.; Ohno, M.; Yoshida, S.; Nishida, A.; Takahashi, K.; Inatomi, O.; Andoh, A. Altered gut microbiota in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 38, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achufusi, T.G.; Sharma, A.; A Zamora, E.; Manocha, D. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment Methods. Cureus 2020, 12, e8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, X.-Q. The prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging 2022, 14, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, D.L.; Disbrow, M.B.; Kahn, A.; Koepke, L.M.; Harris, L.A.; Harrison, M.E.; Crowell, M.D.; Ramirez, F.C. Duodenal Aspirates for Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth: Yield, PPIs, and Outcomes after Treatment at a Tertiary Academic Medical Center. Gastroenterol. Res. Pr. 2015, 2015, 971582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, M.; D'Angelo, G.; Di Rienzo, T.; Scarpellini, E.; Ojetti, V. Diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in the clinical practice. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sundin, O.H.; Mendoza-Ladd, A.; Zeng, M.; Diaz-Arévalo, D.; Morales, E.; Fagan, B.M.; Ordoñez, J.; Velez, P.; Antony, N.; McCallum, R.W. The human jejunum has an endogenous microbiota that differs from those in the oral cavity and colon. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S.C.; Bhagatwala, J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Management. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, e00078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginnebaugh, B.; Chey, W.D.; Saad, R. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth How to Diagnose and Treat (and Then Treat Again). Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2020, 49, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, N.; Rydzewska-Rosołowska, A.; Kakareko, K.; Rosołowski, M.; Głowińska, I.; Hryszko, T. Show Me What You Have Inside—The Complex Interplay between SIBO and Multiple Medical Conditions—A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 15, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaie, A.; Buresi, M.; Lembo, A.; Lin, H.; McCallum, R.; Rao, S.; Schmulson, M.; Valdovinos, M.; Zakko, S.; Pimentel, M. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Talley, N.J.; Jones, M.; Kendall, B.J.; Koloski, N.; Walker, M.M.; Morrison, M.; Holtmann, G.J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez Teran, J. and F. Guarner Aguilar, Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), a clinically overdiagnosed entity? Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 47, 502190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maeda, Y.; Murakami, T. Diagnosis by Microbial Culture, Breath Tests and Urinary Excretion Tests, and Treatments of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasbarrini, A.; Corazza, G.R.; Gasbarrini, G.B.; Montalto, M.; di Stefano, M.; Basilisco, G.; Parodi, A.; Usai-Satta, P.; Satta, P.U.; Vernia, P.; et al. Methodology and Indications of H2-Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Diseases: The Rome Consensus Conference. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29 (Suppl. 1), 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.C.; Massey, B.T. Scintigraphy Demonstrates High Rate of False-positive Results From Glucose Breath Tests for Small Bowel Bacterial Overgrowth. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, R.J.; Chey, W.D. Breath Testing for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Maximizing Test Accuracy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 1964–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhang, R. Comparison of jejunal aspirate culture and methane and hydrogen breath test in the diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Ir. J. Med Sci. (1971 -) 2023, 193, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnuolo, J.; Schiller, D.; Bailey, R.J. Using breath tests wisely in a gastroenterology practice: an evidence-based review of indications and pitfalls in interpretation. Am J Gastroenterol 2002, 97, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaie, A.; Pimentel, M.; Rao, S.S. How to Test and Treat Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: an Evidence-Based Approach. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2016, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, B.P.J.d.L.; Ledochowski, M.; Ratcliffe, N.M. The importance of methane breath testing: a review. J. Breath Res. 2013, 7, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuteja, A.K.; Talley, N.J.; Stoddard, G.J.; Samore, M.H.; Verne, G.N. Risk factors for upper and lower functional gastrointestinal disorders in Persian Gulf War Veterans during and post-deployment. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 31, e13533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.Z.; Lyu, R.; McMichael, J.; Gabbard, S. Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction Is Associated with Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 4834–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyleris, E.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Tzivras, D.; Koussoulas, V.; Barbatzas, C.; Pimentel, M. The Prevalence of Overgrowth by Aerobic Bacteria in the Small Intestine by Small Bowel Culture: Relationship with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz-Grochowska, J.P.; Domanski, N.; Drywień, M.E. Efficacy of an Irritable Bowel Syndrome Diet in the Treatment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takakura, W.; Pimentel, M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome – An Update. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, P.; Moayyedi, P.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Simren, M.; Vanner, S. Critical appraisal of the SIBO hypothesis and breath testing: A clinical practice update endorsed by the European society of neurogastroenterology and motility (ESNM) and the American neurogastroenterology and motility society (ANMS). Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2024, 36, e14817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, K.E.; Bundy, R.; Weinberg, R.B. Distinctive Clinical Correlates of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth with Methanogens. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1598–1605.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegenauer, C.; Hammer, H.F.; Mahnert, A.; Moissl-Eichinger, C. Methanogenic archaea in the human gastrointestinal tract. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takakura, W.; Pimentel, M.; Rao, S.; Villanueva-Millan, M.J.; Chang, C.; Morales, W.; Sanchez, M.; Torosyan, J.; Rashid, M.; Hosseini, A.; et al. A Single Fasting Exhaled Methane Level Correlates With Fecal Methanogen Load, Clinical Symptoms and Accurately Detects Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efremova, I.; Maslennikov, R.; Poluektova, E.; Vasilieva, E.; Zharikov, Y.; Suslov, A.; Letyagina, Y.; Kozlov, E.; Levshina, A.; Ivashkin, V. Epidemiology of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 3400–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshini, R.; Dai, S.-C.; Lezcano, S.; Pimentel, M. A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Tests for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007, 53, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; et al. Evaluation of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 17, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, K.H.; Wong, M.S.; Tan, P.O.; Lim, S.Z.; Beh, K.H.; Chong, S.C.S.; Zulkifli, K.K.; Thalha, A.M.; Mahadeva, S.; Lee, Y.Y. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth In Various Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Case–Control Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 67, 3881–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, S.R.; Shah, A.; Talley, N.J.; Koloski, N.; Jones, M.P.; Walker, M.M.; Morrison, M.; Holtmann, G. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Functional Dyspepsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, C.K.; Farmer, A.D.; Haworth, J.J.; Treadway, S.; Hobson, A.R. Performance and Interpretation of Hydrogen and Methane Breath Testing Impact of North American Consensus Guidelines. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 5571–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, M.; Mayer, A.G.; Park, S.; Chow, E.J.; Hasan, A.; Kong, Y. Methane Production During Lactulose Breath Test Is Associated with Gastrointestinal Disease Presentation. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2003, 48, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovski, A.; Doré, J.; Levenez, F.; Alric, M.; Brugère, J. Molecular evaluation of the human gut methanogenic archaeal microbiota reveals an age-associated increase of the diversity. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2010, 2, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, E.; et al. Additional Value of CH(4) Measurement in a Combined (13)C/H(2) Lactose Malabsorption Breath Test: A Retrospective Analysis. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7469–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, H.F.; Fox, M.R.; Keller, J.; Salvatore, S.; Basilisco, G.; Hammer, J.; Lopetuso, L.; Benninga, M.; Borrelli, O.; Dumitrascu, D.; et al. European guideline on indications, performance, and clinical impact of hydrogen and methane breath tests in adult and pediatric patients: European Association for Gastroenterology, Endoscopy and Nutrition, European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, and European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition consensus. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2021, 10, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, F.; et al. Does Single Fasting Methane Levels Really Detect Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth? Am J Gastroenterol 2023, 118, 1299–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.N.; Rahimian, P.; Stork, C.; Moshiree, B.; Jones, M.; Chuang, E.; Wahl, C.; Singh, S.; Rao, S.S.C. Evaluation of a Novel Smart Capsule Bacterial Detection System Device for Diagnosis of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2024, 37, e14965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, J.Z.; Yao, C.; Rotbart, A.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Human intestinal gas measurement systems: in vitro fermentation and gas capsules. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Yao, C.K.; Berean, K.J.; Ha, N.; Ou, J.Z.; Ward, S.A.; Pillai, N.; Hill, J.; Cottrell, J.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; et al. Intestinal Gas Capsules: A Proof-of-Concept Demonstration. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, M.; Al-Bahadly, I.; Thomas, D.G.; Young, W.; Cheng, L.K.; Avci, E. Smart capsules for sensing and sampling the gut: status, challenges and prospects. Gut 2023, 73, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, P.A.; Yao, C.K.; Maggo, J.; John, J.; Chrimes, A.F.; Burgell, R.E.; Muir, J.G.; Parker, F.C.; So, D.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; et al. Comparison of gastrointestinal landmarks using the gas-sensing capsule and wireless motility capsule. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 56, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, R. Editorial: Interaction between fibre and colonic fermentation assessed with a novel gas-sensing capsule. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 58, 828–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; A Thwaites, P.; Gibson, P.R.; Burgell, R.; Ho, V. Comparison of Gas-sensing Capsule With Wireless Motility Capsule in Motility Disorder Patients. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2024, 30, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Thwaites, P.; Slater, R.; Probert, C.; Gibson, P.R. Recent advances in measuring the effects of diet on gastrointestinal physiology: Sniffing luminal gases and fecal volatile organic compounds. JGH Open 2024, 8, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, D.; Yao, C.K.; Gill, P.A.; Thwaites, P.A.; Ardalan, Z.S.; McSweeney, C.S.; Denman, S.E.; Chrimes, A.F.; Muir, J.G.; Berean, K.J.; et al. Detection of changes in regional colonic fermentation in response to supplementing a low FODMAP diet with dietary fibres by hydrogen concentrations, but not by luminal pH. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 58, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonu, I.; Oh, S.J.; Rao, S.S.C. Capsules for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders- A Game Changer. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2024, 26, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Yao, C.K.; Berean, K.J.; Ha, N.; Ou, J.Z.; Ward, S.A.; Pillai, N.; Hill, J.; Cottrell, J.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; et al. Intestinal Gas Capsules: A Proof-of-Concept Demonstration. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of General 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene PCR Primers for Classical and Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Diversity Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Fan, X.; Shi, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J.; Su, X. Comprehensive Assessment of 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing for Microbiome Profiling across Multiple Habitats. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0056323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, Y. Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Analysis Using Long-Read Nanopore Sequencing for Rapid Identification of Bacteria from Clinical Specimens. Methods Mol Biol 2023, 2632, 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Moorlag, S.J.C.F.M.; Coolen, J.P.M.; Bosch, B.v.D.; Jin, E.H.-M.; Buil, J.B.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Melchers, W.J.G. Targeting the 16S rRNA Gene by Reverse Complement PCR Next-Generation Sequencing: Specific and Sensitive Detection and Identification of Microbes Directly in Clinical Samples. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0448322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Spakowicz, D.J.; Hong, B.-Y.; Petersen, L.M.; Demkowicz, P.; Chen, L.; Leopold, S.R.; Hanson, B.M.; Agresta, H.O.; Gerstein, M.; et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E.M. Exploring the Small Intestinal Microbiome: Relationships to Symptoms and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 22, 241–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, G.; Rezaie, A.; Mathur, R.; Barlow, G.M.; Rashid, M.; Hosseini, A.; Wang, J.; Parodi, G.; Villanueva-Millan, M.J.; Sanchez, M.; et al. Defining Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth by Culture and High Throughput Sequencing. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 22, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslennikov, R.; Ivashkin, V.; Efremova, I.; Poluektova, E.; Kudryavtseva, A.; Krasnov, G. Gut dysbiosis and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth as independent forms of gut microbiota disorders in cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Hong, G.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Qian, W.; Xiong, H.; Bai, T.; Song, J.; Hou, X. Duodenal and rectal mucosal microbiota related to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 35, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundin, J.; Aziz, I.; Nordlander, S.; Polster, A.; Hu, Y.O.O.; Hugerth, L.W.; Pennhag, A.A.L.; Engstrand, L.; Törnblom, H.; Simrén, M.; et al. Evidence of altered mucosa-associated and fecal microbiota composition in patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, A.S.; Gao, X.; Bohm, M.; Lin, H.; Gupta, A.; Nelson, D.E.; Toh, E.; Teagarden, S.; Siwiec, R.; Dong, Q.; et al. Characterization of Proximal Small Intestinal Microbiota in Patients With Suspected Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, e00073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Ma, J.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wan, J. Mucosa-Associated Microbial Profile Is Altered in Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Dong, W.; Lu, S.; Du, Y.; Duan, L. Fecal Coprococcus, hidden behind abdominal symptoms in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, V.; Huellner, M.; Murray, F.; Schnurre, L.; Becker, A.S.; Bordier, V.; Pohl, D. Nutrient Challenge Testing Is Not Equivalent to Scintigraphy−Lactulose Hydrogen Breath Testing in Diagnosing Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 26, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zheng, X.; Chu, H.; Cong, Y.; Fried, M.; Fox, M.; Dai, N. A study of the methodological and clinical validity of the combined lactulose hydrogen breath test with scintigraphic oro-cecal transit test for diagnosing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS patients. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Parkman, H.P.; Urbain, J.-L.C.; Brown, K.L.; Donahue, D.J.; Knight, L.C.; Maurer, A.H.; Fisher, R.S. Comparison of Scintigraphy and Lactulose Breath Hydrogen Test for Assessment of Orocecal Transit (Lactulose Accelerates Small Bowel Transit). Dig. Dis. Sci. 1997, 42, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, I. Breath test for differential diagnosis between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel disease: An observation on non-absorbable antibiotics. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Cheeseman, F.; Vanner, S. Combined oro-caecal scintigraphy and lactulose hydrogen breath testing demonstrate that breath testing detects oro-caecal transit, not small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with IBS. Gut 2010, 60, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, A.; Solomons, N.W. Time-course of cigarette smoke contamination of clinical hydrogen breath-analysis tests. Clin. Chem. 1983, 29, 1980–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattio, N.; Pradat, P.; Machon, C.; Mialon, A.; Roman, S.; Cuerq, C.; Mion, F. Glucose breath test for the detection of small intestine bacterial overgrowth: Impact of diet prior to the test. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2024, 36, e14801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadesse, K.; Eastwood, M. BREATH-HYDROGEN TEST AND SMOKING. Lancet 1977, 310, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, A.; Solomons, N.W. Time-course of cigarette smoke contamination of clinical hydrogen breath-analysis tests. Clin. Chem. 1983, 29, 1980–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perman, J.; Modler, S.; Engel, R.; Heldt, G. Effect of ventilation on breath hydrogen measurements. J Lab Clin Med 1985, 105, 436–439. [Google Scholar]

- Le Nevé, B.; Derrien, M.; Tap, J.; Brazeilles, R.; Portier, S.C.; Guyonnet, D.; Ohman, L.; Störsrud, S.; Törnblom, H.; Simrén, M. Fasting breath H2 and gut microbiota metabolic potential are associated with the response to a fermented milk product in irritable bowel syndrome. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0214273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korterink, J.J.; Benninga, M.A.; van Wering, H.M.; Deckers-Kocken, J.M. Glucose Hydrogen Breath Test for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Children With Abdominal Pain–Related Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Misra, A.; Ghoshal, U.C. Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome Exhale More Hydrogen Than Healthy Subjects in Fasting State. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 16, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, L.; Foti, M.; Ruggia, O.; Chiecchio, A. Increased Incidence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth During Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.; Lai, S.; Lee, A.; He, X.; Chen, S. Meta-analysis: proton pump inhibitors moderately increase the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 53, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revaiah, P.C.; Kochhar, R.; Rana, S.V.; Berry, N.; Ashat, M.; Dhaka, N.; Reddy, Y.R.; Sinha, S.K. Risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients receiving proton pump inhibitors versus proton pump inhibitors plus prokinetics. JGH Open 2018, 2, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.X.; Tang, S.; Li, C.M.; Wan, J. [The effects of continuous proton pump inhibitor therapy on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in elderly]. . 2020, 59, 706–710. [Google Scholar]

- Muraki, M.; Fujiwara, Y.; Machida, H.; Okazaki, H.; Sogawa, M.; Yamagami, H.; Tanigawa, T.; Shiba, M.; Watanabe, K.; Tominaga, K.; et al. Role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in severe small intestinal damage in chronic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 49, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Misra, A.; Ghoshal, U.C. Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome Exhale More Hydrogen Than Healthy Subjects in Fasting State. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 16, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Mahon, M.; et al. Are hydrogen breath tests valid in the elderly? Gerontology 1996, 42, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flourie, B.; Turk, J.; Lemann, M.; Florent, C.; Colimon, R.; Rambaud, J. Breath hydrogen in bacterial overgrowth. Gastroenterology 1989, 96, 1225–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendino, T.; Sandúa, A.; Calleja, S.; González, Á.; Alegre, E. Lactose tolerance test as an alternative to hydrogen breath test in the study of lactose malabsorption. Adv. Lab. Med. / Av. en Med. de Lab. 2020, 1, 20200102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Kumar, S.; Chourasia, D.; Misra, A. Lactose hydrogen breath test versus lactose tolerance test in the tropics: does positive lactose tolerance test reflect more severe lactose malabsorption? Trop Gastroenterol 2009, 30, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, M.; Kong, Y.; Park, S. Breath testing to evaluate lactose intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome correlates with lactulose testing and may not reflect true lactose malabsorption. Am J Gastroenterol 2003, 98, 2700–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misselwitz, B.; et al. Lactose malabsorption and intolerance: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. United European Gastroenterol J 2013, 1, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer, A.D.; McGill, D.B.; Thomas, P.J.; Hofmann, A.F. Prospective Comparison of Indirect Methods for Detecting Lactase Deficiency. New Engl. J. Med. 1975, 293, 1232–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.V.; Malik, A. Hydrogen Breath Tests in Gastrointestinal Diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 29, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerlein, L.; et al. Correlation between symptoms developed after the oral ingestion of 50 g lactose and results of hydrogen breath testing for lactose intolerance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008, 27, 659–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, J.H.; Levitt, M.D. Quantitative Measurement of Lactose Absorption. Gastroenterology 1976, 70, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, L.; Priefer, R. Lactose Intolerance: What Your Breath Can Tell You. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, M.; et al. Mixing of the intestinal content and variations of fermentation capacity do not affect the results of hydrogen breath test. Am J Gastroenterol 2003, 98, 1584–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corazza, G.R.; Strocchi, A.; Gasbarrini, G. Fasting breath hydrogen in celiac disease. Gastroenterology 1987, 93, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansaldi-Balocco, N.; Malorgio, E.; Faussone, D.; Dell'Olio, D.; Morra, I.; Forni, M.; Oderda, G. [Hydrogen breath test in celiac disease: relationship to histological changes in jejunal mucosa]. Minerva Pediatr. 1994, 46, 569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Millan, M.J.; Leite, G.; Wang, J.; Morales, W.; Parodi, G.; Pimentel, M.L.; Barlow, G.M.; Mathur, R.; Rezaie, A.; Sanchez, M.; et al. Methanogens and Hydrogen Sulfide Producing Bacteria Guide Distinct Gut Microbe Profiles and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Subtypes. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 2055–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Wutzke, K.D.; Däbritz, J. Methane breath tests and blood sugar tests in children with suspected carbohydrate malabsorption. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casellas, F.; Guarner, L.; Antolín, M.; Malagelada, J.-R. Hydrogen Breath Test With Low-Dose Rice Flour for Assessment of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency. Pancreas 2004, 29, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, N.A.; Al-Ani, M.R.; Lafta, A.M.; Kassir, Z.A. Value of breath hydrogen test in detection of hypolactasia in patients with chronic diarrhoea. J. Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1990, 530, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Lee, K.; Chung, Y.Y.; Lee, Y.W.; Kim, D.B.; Sung, H.J.; Chung, W.C.; Paik, C. Clinical significance of the glucose breath test in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 30, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkin, D.; Boston, F.M.; Blank, D.; Yalovsky, M.; Mishkin, S. The Glucose Breath Test: A Diagnostic Test for Small Bowel Stricture(s) in Crohn's Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2002, 47, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, K.; Shimizu, M.; Nishimura, Y.; Nakagawa, Y.; Ichikawa, T. Simultaneous Determination of Hydrogen, Methane and Carbon Dioxide of Breath Using Gas-Solid Chromatography. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 1992, 38, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Mengoli, C.; Bergonzi, M.; Miceli, E.; Pagani, E.; Corazza, G.R. Hydrogen breath test in patients with severe constipation: the interference of the mixing of intestinal content. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, P.G.; Parthasarathy, G.; Chen, J.; O'Connor, H.M.; Chia, N.; Bharucha, A.E.; Gaskins, H.R. Assessing the colonic microbiome, hydrogenogenic and hydrogenotrophic genes, transit and breath methane in constipation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Rezaie, A. Pros and Cons of Breath Testing for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2023, 19, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaie, A.; Buresi, M.; Lembo, A.; Lin, H.; McCallum, R.; Rao, S.; Schmulson, M.; Valdovinos, M.; Zakko, S.; Pimentel, M. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, H.K.; Schober, P.; Scheurlen, C.; Marklein, G.; Horré, R.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Sauerbruch, T. Use of the lactose-[13C]ureide breath test for diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth: comparison to the glucose hydrogen breath test. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 44, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, O.H.; et al. Does a glucose-based hydrogen and methane breath test detect bacterial overgrowth in the jejunum? Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018, 30, e13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stotzer, P.; Brandberg, A.; Kilander, A.F. Diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in clinical praxis: a comparison of the culture of small bowel aspirate, duodenal biopsies and gastric aspirate. Hepatogastroenterology 1998, 45, 1018–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, G.; Morales, W.; Weitsman, S.; Celly, S.; Parodi, G.; Mathur, R.; Barlow, G.M.; Sedighi, R.; Millan, M.J.V.; Rezaie, A.; et al. The duodenal microbiome is altered in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0234906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y. and T. Murakami, Diagnosis by Microbial Culture, Breath Tests and Urinary Excretion Tests, and Treatments of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Talley, N.J.; Holtmann, G. Current and Future Approaches for Diagnosing Small Intestinal Dysbiosis in Patients With Symptoms of Functional Dyspepsia. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 830356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Dutta, U.; Noor, M.T.; Taneja, N.; Kochhar, R.; Sharma, M.; Singh, K. Endoscopic jejunal biopsy culture: a simple and effective method to study jejunal microflora. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 29, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuteja, A.K.; Talley, N.J.; Stoddard, G.J.; Samore, M.H.; Verne, G.N. Risk factors for upper and lower functional gastrointestinal disorders in Persian Gulf War Veterans during and post-deployment. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 31, e13533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, S.; Ishimura, N.; Mikami, H.; Okimoto, E.; Uno, G.; Tamagawa, Y.; Aimi, M.; Oshima, N.; Sato, S.; Ishihara, S.; et al. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Refractory Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 22, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, G.; Amanzada, A.; Gress, T.M.; Ellenrieder, V.; Neesse, A.; Kunsch, S. High Prevalence of Pathological Hydrogen Breath Tests in Patients with Functional Dyspepsia. Digestion 2018, 100, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzl, J.; Gröhl, K.; Kafel, A.; Nagl, S.; Muzalyova, A.; Gölder, S.K.; Ebigbo, A.; Messmann, H.; Schnoy, E. Impact of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Other Gastrointestinal Disorders—A Retrospective Analysis in a Tertiary Single Center and Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, Z.; Tao, H.; Li, L.; Xuan, J.; Wang, F. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with clinical relapse in patients with quiescent Crohn’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 784–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Talley, N.J.; Koloski, N.; Macdonald, G.A.; Kendall, B.J.; Shanahan, E.R.; Walker, M.M.; Keely, S.; Jones, M.P.; Morrison, M.; et al. Duodenal bacterial load as determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in asymptomatic controls, functional gastrointestinal disorders and inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 52, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, J.E.; Chebli, L.A.; Ribeiro, T.C.; Castro, A.C.; Gaburri, P.D.; Pace, F.H.; Barbosa, K.V.; Ferreira, L.E.; Passos, M.D.; Malaguti, C.; et al. Small-Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth is Associated With Concurrent Intestinal Inflammation But Not With Systemic Inflammation in Crohn’s Disease Patients. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 52, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; et al. Breath tests in the diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome in comparison with quantitative upper gut aspirate culture. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 26, 753–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zheng, X.; Chu, H.; Cong, Y.; Fried, M.; Fox, M.; Dai, N. A study of the methodological and clinical validity of the combined lactulose hydrogen breath test with scintigraphic oro-cecal transit test for diagnosing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS patients. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, J.; Sinha, S.; Singh, K. Comparison of Lactulose and Glucose Breath Test for Diagnosis of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Digestion 2012, 85, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C. How to Interpret Hydrogen Breath Tests. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 17, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a framework for understanding irritable bowel syndrome. JAMA 2004, 292, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, G.D.; De, A.; Som, S.; Jana, S.; Daschakraborty, S.B.; Chaudhuri, S.; Pradhan, M. Hydrogen sulphide in exhaled breath: a potential biomarker for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS. J. Breath Res. 2016, 10, 026010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, P.; Moayyedi, P.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Simren, M.; Vanner, S. Critical appraisal of the SIBO hypothesis and breath testing: A clinical practice update endorsed by the European society of neurogastroenterology and motility (ESNM) and the American neurogastroenterology and motility society (ANMS). Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2024, 36, e14817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Kim, J.J.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Du, L.; Dai, N. Prevalence and predictors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraru, I.G.; Portincasa, P.; Moraru, A.G.; Diculescu, M.; Dumitraşcu, D.L. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth produces symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome which are improved by rifaximin. A pilot study.. 2014, 51, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; et al. Breath tests in the diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome in comparison with quantitative upper gut aspirate culture. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014, 26, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshini, R.; Dai, S.-C.; Lezcano, S.; Pimentel, M. A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Tests for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007, 53, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; et al. Evaluation of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 17, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, I.H.; Paik, C.-N.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, J.M.; Choi, S.Y.; Hong, K.P. Lactase Deficiency Diagnosed by Endoscopic Biopsy-based Method is Associated With Positivity to Glucose Breath Test. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2023, 29, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.X.; Ma, Y.J.; Chen, G.Y.; Gao, X.; Yang, L. [Relationship of TLR2 and TLR4 expressions on the surface of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to small intestinal bacteria overgrowth in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2019, 27, 286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Gkolfakis, P.; Tziatzios, G.; Leite, G.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Xirouchakis, E.; Panayiotides, I.G.; Karageorgos, A.; Millan, M.J.; Mathur, R.; Weitsman, S.; et al. Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriakusumah, Y.; Lesmana, C.R.A.; Bastian, W.P.; Jasirwan, C.O.M.; Hasan, I.; Simadibrata, M.; Kurniawan, J.; Sulaiman, A.S.; Gani, R.A. The role of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) patients evaluated using Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) Transient Elastography (TE): a tertiary referral center experience. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Mao, L.; Wang, L.; Quan, X.; Xu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Dai, F. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and orocecal transit time in patients of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, e535–e539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, R.D.; Baker, J.; Harer, K.; Lee, A.; Hasler, W.; Saad, R.; Schulman, A.R. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Clinical Presentation in Patients with Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes. Surg. 2020, 31, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.B.; Paik, C.-N.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.M.; Jun, K.-H.; Chung, W.C.; Lee, K.-M.; Yang, J.-M.; Choi, M.-G. Positive Glucose Breath Tests in Patients with Hysterectomy, Gastrectomy, and Cholecystectomy. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H.M.; Krogh, K.; Borre, M.; Gregersen, T.; Hansen, M.M.; Arveschoug, A.K.; Christensen, P.; Drewes, A.M.; Emmertsen, K.J.; Laurberg, S.; et al. Chronic loose stools following right-sided hemicolectomy for colon cancer and the association with bile acid malabsorption and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Color. Dis. 2022, 25, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; et al. Influence of Helicobacter pylori infection and its eradication treatment on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022, 102, 3382–3387. [Google Scholar]

- George, N.S.; Sankineni, A.; Parkman, H.P. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Gastroparesis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 59, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Xu, Y.; Hou, X.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Hao, Y.; Ouyang, Q.; Wu, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, M.; et al. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Subclinical Hypothyroidism of Pregnant Women. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Duan, Y.; Han, X.; Dong, H.; Geng, J. Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Multiple Sclerosis: a Case-Control Study from China. J. Neuroimmunol. 2016, 301, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasuike, Y.; Endo, T.; Koroyasu, M.; Matsui, M.; Mori, C.; Yamadera, M.; Fujimura, H.; Sakoda, S. Bile acid abnormality induced by intestinal dysbiosis might explain lipid metabolism in Parkinson’s disease. Med Hypotheses 2020, 134, 109436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.H.; Park, S.J.; Cheon, J.H.; Kim, T.I.; Kim, W.H. Rediscover the clinical value of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with intestinal Behçet's disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 33, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naletov, A.V.; Svistunova, N.A. Assessment of the state of the small intestine microbiota in children on a long-term dairy-free diet. Probl. Nutr. 2022, 91, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durán-Rosas, C.; Priego-Parra, B.A.; Morel-Cerda, E.; Mercado-Jauregui, L.A.; Aquino-Ruiz, C.A.; Triana-Romero, A.; Amieva-Balmori, M.; Velasco, J.A.V.-R.; Remes-Troche, J.M. Incidence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Symptoms After 7 Days of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use: A Study on Healthy Volunteers. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 69, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraki, M.; Fujiwara, Y.; Machida, H.; Okazaki, H.; Sogawa, M.; Yamagami, H.; Tanigawa, T.; Shiba, M.; Watanabe, K.; Tominaga, K.; et al. Role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in severe small intestinal damage in chronic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 49, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Talley, N.J.; Jones, M.; Kendall, B.J.; Koloski, N.; Walker, M.M.; Morrison, M.; Holtmann, G.J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Thite, P.; Hansen, T.; Kendall, B.J.; Sanders, D.S.; Morrison, M.; Jones, M.P.; Holtmann, G. Links between celiac disease and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 37, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslennikov, R.; Pavlov, C.; Ivashkin, V. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in cirrhosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol. Int. 2018, 12, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Kurdi, B.; Babar, S.; El Iskandarani, M.; Bataineh, A.; Lerch, M.M.; Young, M.; Singh, V.P. Factors That Affect Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Chronic Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, e00072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, X.-Q. The prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging 2022, 14, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Pakeerathan, V.; Jones, M.P.; Kashyap, P.C.; Virgo, K.; Fairlie, T.; Morrison, M.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Holtmann, G.J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Complicating Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2023, 29, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, S.; Ishimura, N.; Mikami, H.; Okimoto, E.; Uno, G.; Tamagawa, Y.; Aimi, M.; Oshima, N.; Sato, S.; Ishihara, S.; et al. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Refractory Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 22, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, G.; Amanzada, A.; Gress, T.M.; Ellenrieder, V.; Neesse, A.; Kunsch, S. High Prevalence of Pathological Hydrogen Breath Tests in Patients with Functional Dyspepsia. Digestion 2018, 100, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, C.; Konrad, P.; Błońska, A.; Chojnacki, J.; Mędrek-Socha, M. Usefulness of the hydrogen breath test in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterol. Rev. 2020, 15, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziatzios, G.; Gkolfakis, P.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Mathur, R.; Pimentel, M.; Damoraki, G.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Dimitriadis, G.; Triantafyllou, K. High Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth among Functional Dyspepsia Patients. Dig. Dis. 2020, 39, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, K.H.; Wong, M.S.; Tan, P.O.; Lim, S.Z.; Beh, K.H.; Chong, S.C.S.; Zulkifli, K.K.; Thalha, A.M.; Mahadeva, S.; Lee, Y.Y. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth In Various Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Case–Control Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 67, 3881–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Lee, K.; Chung, Y.Y.; Lee, Y.W.; Kim, D.B.; Sung, H.J.; Chung, W.C.; Paik, C. Clinical significance of the glucose breath test in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 30, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Caviglia, G.P.; Brignolo, P.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Reggiani, S.; Sguazzini, C.; Smedile, A.; Pellicano, R.; Resegotti, A.; Astegiano, M.; et al. Glucose breath test and Crohn’s disease: Diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and evaluation of therapeutic response. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, M.; Gologan, S.; Stoicescu, A.; Ionescu, M.; Nicolaie, T.; Diculescu, M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome Prevalence in Romanian Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Health Sci J 2016, 42, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, J.E.; Chebli, L.A.; Ribeiro, T.C.; Castro, A.C.; Gaburri, P.D.; Pace, F.H.; Barbosa, K.V.; Ferreira, L.E.; Passos, M.D.; Malaguti, C.; et al. Small-Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth is Associated With Concurrent Intestinal Inflammation But Not With Systemic Inflammation in Crohn’s Disease Patients. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 52, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Talley, N.J.; Koloski, N.; Macdonald, G.A.; Kendall, B.J.; Shanahan, E.R.; Walker, M.M.; Keely, S.; Jones, M.P.; Morrison, M.; et al. Duodenal bacterial load as determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in asymptomatic controls, functional gastrointestinal disorders and inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 52, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Yadav, A.; Fatima, B.; Agrahari, A.P.; Misra, A. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A case-control study. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 41, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, Z.; Tao, H.; Li, L.; Xuan, J.; Wang, F. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with clinical relapse in patients with quiescent Crohn’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 784–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanzl, J.; Gröhl, K.; Kafel, A.; Nagl, S.; Muzalyova, A.; Gölder, S.K.; Ebigbo, A.; Messmann, H.; Schnoy, E. Impact of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Other Gastrointestinal Disorders—A Retrospective Analysis in a Tertiary Single Center and Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; et al. Breath tests in the diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome in comparison with quantitative upper gut aspirate culture. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 26, 753–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraru, I.G.; Moraru, A.G.; Andrei, M.; Iordache, T.; Drug, V.; Diculescu, M.; Portincasa, P.; Dumitrascu, D.L. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated to symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Evidence from a multicentre study in Romania. Rom J Intern Med. 2014, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, M.H.; et al. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: the first study in iran. Middle East J Dig Dis 2015, 7, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chuah, K.H.; Wong, M.S.; Tan, P.O.; Lim, S.Z.; Beh, K.H.; Chong, S.C.S.; Zulkifli, K.K.; Thalha, A.M.; Mahadeva, S.; Lee, Y.Y. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth In Various Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Case–Control Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 67, 3881–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).