Introduction

Diarrhoeal diseases continue to be a global public health problem, ranking among the top five causes of death in all age groups, mainly in children under 10 years of age where it is the third leading cause of death (Abbafati et al., 2020). (Abbafati et al., 2020).

In Mexico, during the period 2010-2019, 57,498,657 cases were reported, with the most affected age groups being those under 5 and over 60 years of age, especially among females. In 2020, a significant decrease is observed, with 2,815,586 cases reported, compared to the previous year when the number of reports was 5,756,174. (General Directorate of Epidemiology, 2022; Ministry of Health, 2020).

In Mexico, with the introduction of the Rotavirus vaccine to the national vaccination schedule in 2006, the mortality rate was reduced by 46% and during the years 2008-2010 a decrease from 18 to 9 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants was observed. The vaccines currently in use are the monovalent vaccine Rotarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and the pentavalent vaccine RotaTeq (Merck and Co), both of which have reduced mortality rates from this pathogen in Latin America. However, as risk factors for acute diarrhoeal diseases such as poverty, consumption of unsafe water and poor sanitation remain in the population, the number of cases remains high (Amin Blanco & Fernández Castillo, 2002). (Amin Blanco & Fernández Castillo, 2016; Olaiz-Fernández et al., 2020).

The aetiological agents of this condition include a wide range of viruses, bacteria and protozoa. In our country in 2019, Rotavirus, Norovirus, Salmonella spp. and Shigella spp. stood out as causative agents of diarrhoeal diseases in children under 5 years of age; while in older age groups, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio cholerae also presented high percentages. Other pathogens gaining importance worldwide are Norovirus, Escherichia coli and its subtypes, Yersinia spp. and Cryptosporidium spp. (Bonkoungou et al., 2013; Ministry of Health, 2020; Zhang et al., 2016).

The state of Baja California was positioned during the period 2014-2016, together with Chiapas, as one of the states with the highest incidence of acute diarrhoeal disease due to Rotavirus. However, there are currently no reports describing the causes during those years in the aforementioned states. (Palacio-Mejía et al., 2020).

Mexicali, the capital of Baja California, is distinguished by its unique gastronomic offerings, the result of a fusion between Mexican cuisine and the influences of Chinese gastronomy, a reflection of its rich migratory history. In this city, the famous “Baja Californian-Chinese” is highlighted by dishes such as carne asada tacos and delicious burritos, which are often complemented with fresh ingredients and spicy sauces. In addition, the proximity to the desert and access to the region’s agricultural products allow for a variety of flavours including fresh seafood and quality vegetables. Wine culture also flourishes in Baja California, with vineyards offering local options that perfectly complement the cuisine. This unique blend of traditions and local products makes the culinary experience in Mexicali truly different from the rest of the country.

The study population consists of a select group that has access to the FilmArray GI Panel test, an advanced but expensive diagnostic method. This access is mainly limited to high socio-economic sectors of the population, meaning that only those individuals or families who can afford the cost of the test, either through private health insurance or their own resources, have the opportunity to benefit from this technology. This creates a disparity in access to accurate and timely diagnoses, as other sectors, lacking the necessary financial resources, are excluded from this advance in medical care. Thus, the study focuses on a privileged group.

Several studies have been published describing a high number of cases of co-infection of two or more enteric pathogens, especially in developing countries. Several clinical investigations have found evidence of a strong association between Rotavirus and Escherichia coli, where patients suffer from a more severe picture compared to infections with a single micro-organism. The association between Shigella and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) has also been reported to increase the frequency of stools during diarrhoea. Unfortunately, in most of the population studied, the presence of more than one pathogen is common even in asymptomatic patients, making it difficult to establish a direct relationship (Andersson et al., 2006). (Andersson et al., 2018; Grimprel et al., 2008; Vergadi et al., 2021).

Conventional screening methods for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal infections include stool culture and stool parasitoscopy, which are laborious and by the time the result is obtained the patient’s clinical picture has usually resolved. Molecular techniques such as the polymerase chain

reaction (PCR), which amplifies specific double-stranded DNA sequences, with their high specificity and sensitivity as well as their rapidity, have improved the microbiological diagnosis of these diseases. Nowadays, there are variants of the polymerase chain reaction such as reverse transcription (RT-PCR), real-time PCR and multiplex PCR (Balsalobre-Arenasa & Alarcón- Cavero, 2017).

However, an obstacle to the detection of gastrointestinal co-infections is the lack of resources and techniques to confirm the presence of more than one micro-organism in the processed samples, as the classic microbiological culture, in addition to the time required for the growth of the micro- organism, only detects one at a time. On the other hand, PCR uses specific molecular panels of viruses, bacteria or parasites requested on the basis of the patient’s clinical picture, which generally does not guide us to the aetiological agent. The Gastrointestinal (GI) Film-Array Panel allows detection of the 22 most common gastrointestinal pathogens with a single panel in approximately one hour: Campylobacter (jejuni, coli and upsaliensis), Clostridioides difficile (Toxin A/B), Plesiomonas shigelloides, Salmonella, Yersinia enterocolitica, Vibrio spp, Vibrio cholerae, Escherichia coli O157, Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC), EPEC, Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella/Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC), Adenovirus, Astrovirus, Norovirus, Rotavirus, Sapovirus, Cryptosporidium spp, Cyclospora cayatenensis, Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia, thus providing a rapid accurate diagnosis and being able to detect polymicrobial infections (Machiels et al., 2020).

The objective of this study was to determine the main microorganisms detected in samples from patients with suspected gastrointestinal infection processed by Panel GI FilmArray during the months of January to October 2023, sent to Laboratorio Lozano and Laboratorio Dorado. These clinical analysis laboratories have been providing services to the community for a long period of time and practically cover most of the cultures in the city of Mexicali, Baja California.

In the present study, we have considered a population with available resources that allow them to access the GI FilmArray Panel technique. This tool, although expensive, offers an effective diagnostic tool that can be crucial for the detection of gastrointestinal diseases. By focusing on this sector of the population, we sought to assess not only the efficacy of the technique, but also the willingness and capacity of these individuals to invest in advanced health services.

Material and Methods

This is an observational and retrospective study verified with the STROBE epidemiological checklist, using data collected from the databases provided by two private laboratories, Laboratorio Dorado and Laboratorio Lozano in the city of Mexicali, Baja California; where patients were selected with clinical data of gastrointestinal infection and who obtained a positive result to some of the microorganisms identified by the GI FilmArray Panel requested by their treating physician in the period from January to October 2023.

Faecal samples should be collected in a clean bottle with an airtight lid, avoid mixing with water, urine or disinfectants. It is sent to the laboratory after collection in a refrigerated box, ideally in liquid Cary-Blair transport medium. If immediate transport is not possible, it should be refrigerated at 4 °C (Buss et al., 2015).

The Film-Array is a rapid multiplex PCR platform that performs nucleic acid extraction, amplification and analysis in approximately one hour. The Film-Array GI Panel was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the detection of 22 pathogens at the same time. A research-only version (IUO version) is available that includes Aeromonas spp. It is able to detect

the genes encoding the heat-labile and heat-stable enterotoxins of ETEC, toxins A and B (tcdA and tcdB) of Clostridioides difficile, Shiga toxins 1 and/or 2 (Stx 1 and Stx 2) of STEC; as well as the following genes: intimin (eae) in EPEC, aagR and aatA in EAEC and plasmid invasion H antigen (ipah) in EIEC and Shigella (Stockmann et al., 2017).

Statistical Analysis

The basic statistical analysis used in the article included the description of variables using frequencies and percentages for demographic characteristics and microorganisms detected. In addition, chi-square tests were used to assess the association between co-infections and categorical variables, allowing for the identification of significant patterns in the study population.

Ethical considerations:

No written informed consent was requested from patients for this article as the data provided to the laboratories from which the database was constructed were used.

Results

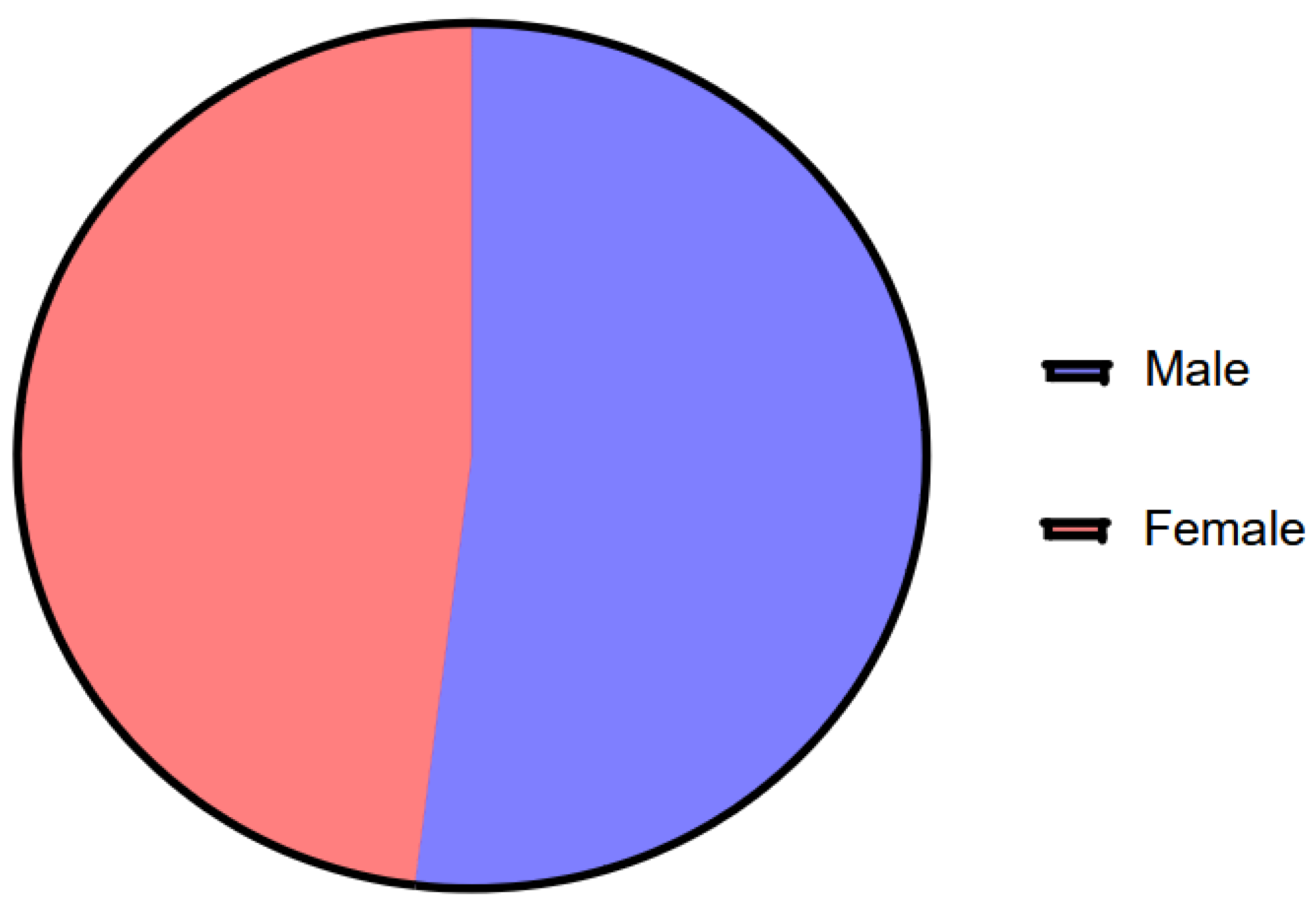

Data from 208 patients whose samples were processed by the GI Film-Array Panel in the indicated laboratories were analysed. The information was organised in Excel documents by laboratory, including sample folio or number, age (missing for 4 patients in the Dorado Laboratory), sex and microorganisms detected. Of the total, 79 patients were negative and 129 patients were positive for at least one micro-organism and were selected for further analysis. Of the 129 positive samples, 72 were from male patients and 57 from female patients (

Figure 1). Additionally, 50 patients with more than one microorganism (co-infections) were identified, classifying the information by sex, age group and microorganisms involved, which facilitated the understanding of the microbiological diversity.

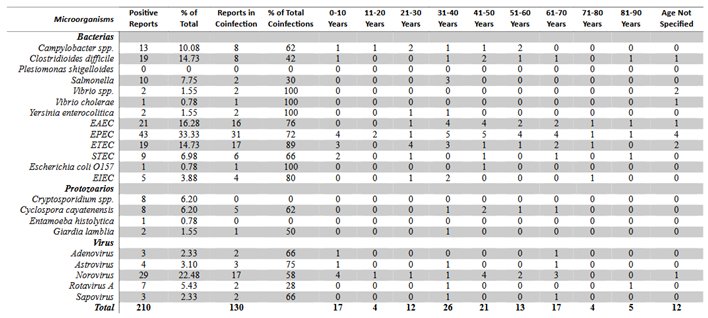

Table 1.

Total number of microorganisms detected by GI Film-Array Panel by age group

Figure 1: Number of reported patients with gastrointestinal co-infection by sex.

Table 1.

Total number of microorganisms detected by GI Film-Array Panel by age group

Figure 1: Number of reported patients with gastrointestinal co-infection by sex.

The Film-Array panel identified a total of 145 bacteria, 19 protozoa and 46 viruses. The most common microorganisms associated with gastrointestinal infections by one microorganism were enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (33.3%), Norovirus (22.48%), enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (16.28%), enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (14.73%) and Clostridioides difficile A/B (14.73%). The least frequent included Astrovirus (3.10%), Sapovirus (2.33%), Adenovirus (2.33%), Vibrio spp. (1.55%), Giardia lamblia (1.55%), Vibrio cholerae (0.78%), Escherichia coli O157 (0.78%) and Entamoeba histolytica (0.78%). Plesiomonas shigelloides was not detected in any sample.

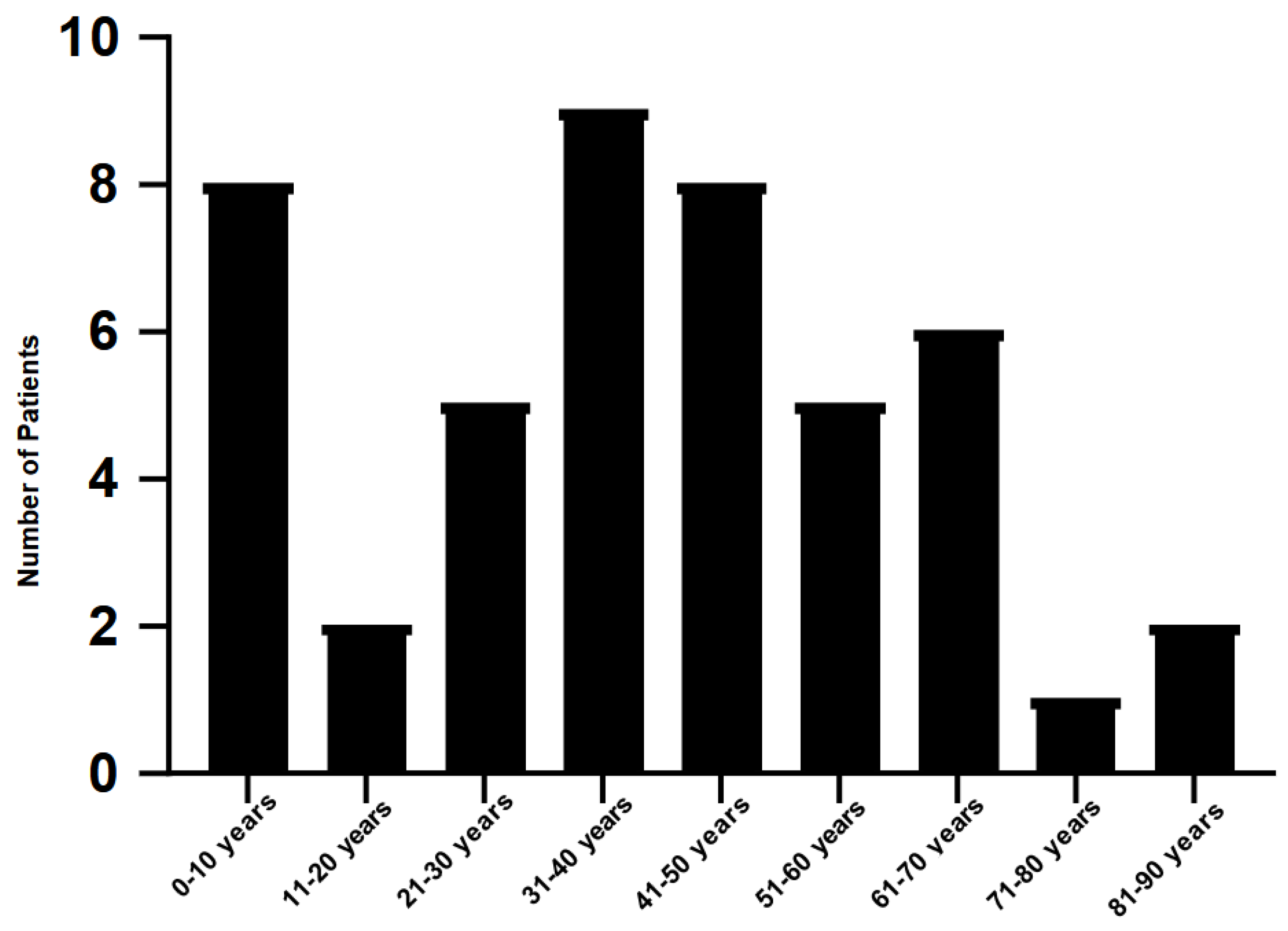

Among the 50 patients with co-infections, 24 were female and 26 were male. The age groups most represented in coinfections were 31-40 years (9 patients), 41-50 years (8 patients) and 0-10 years (8 patients), while the 71-80 years’ age group had only 1 patient (

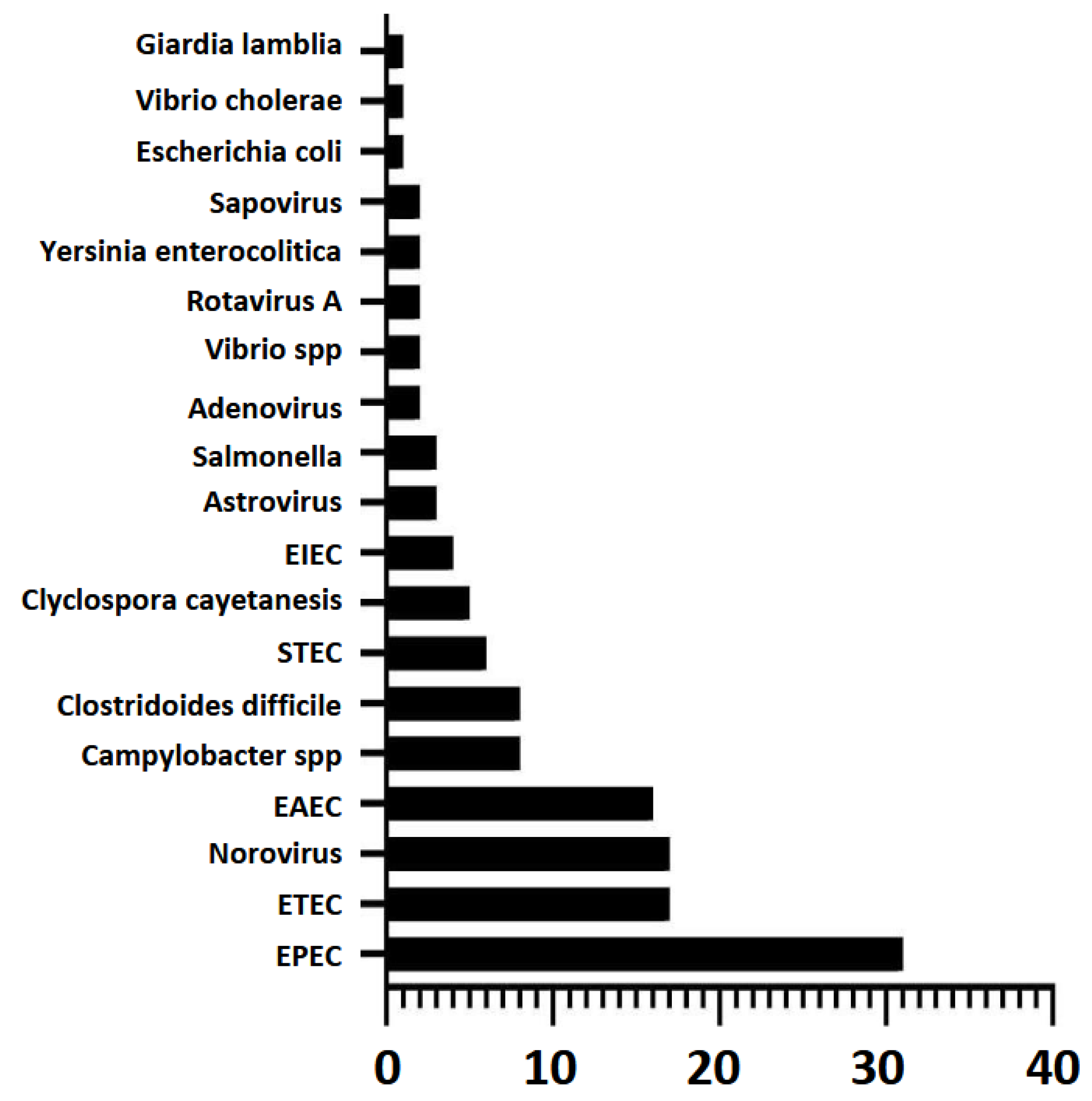

Figure 2). The most common microorganisms in coinfections were

EPEC, ETEC, Norovirus, EAEC, Clostridioides difficile A/B and Campylobacter, while

Cryptosporidium and Entamoeba histolytica were not associated with coinfections.

Figure 2.

Number of patients with gastrointestinal co-infection by age group.

Figure 2.

Number of patients with gastrointestinal co-infection by age group.

Figure 3.

Micro-organisms present in gastrointestinal co-infections and number of positive samples reported by GI Film-Array Panel.

Figure 3.

Micro-organisms present in gastrointestinal co-infections and number of positive samples reported by GI Film-Array Panel.

By age group, the main micro-organism involved in patients aged 0-10 years was Norovirus as well as EPEC. In the 11-20, 31-40, 41-50, 51-60 and 61-70-year age groups it was EPEC. In patients aged 21-30 years, ETEC was prominent. In the 71-80 and 81-90 age groups, no microorganism was prominent but EAEC, EPEC, ETEC, EIEC, Clostridioides difficile, STEC and Rotavirus A were present. In the four patients with unknown age group, EPEC was present in all.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, the different strains of Escherichia coli were the most reported in patients with gastrointestinal infections, as well as co-infections, and were mainly present in the 31-40 and 41-50 age groups; this may indicate a relationship with the dietary habits of these patients, as adults have greater access to the consumption of various types of food. In our country, the consumption of raw foods or unpasteurised dairy products is popular, which increases the risk of contracting a polymicrobial gastrointestinal infection due to multidrug-resistant strains. One of the limitations of this study was not having the clinical history of the patients to obtain the characteristics of their clinical picture and their diet for a more in-depth analysis.

The GI Film-Array Panel has demonstrated advantages over conventional detection methods (Soto Ojeda et al., 2023) one of the most important being the time in which results are obtained. In a multicentre study conducted in 2015 to evaluate the performance of the GI Film-Array GI Panel in the simultaneous detection of gastrointestinal pathogens, a sensitivity of 100% was reported for 12 of the 22 microorganisms it is capable of detecting and greater than 92.5% for 7 of these; as well as a specificity greater than 97.1% for all pathogens (Buss et al., 2015). (Buss et al., 2015).

In another study conducted in 2020 in the United States to evaluate the performance of the FilmArray GI panel, EPEC, EAEC, ETEC and STEC were reported as the main bacteria present in gastrointestinal co-infections, which were also the agents found in the majority of patients with co-infections in this study. (Torres-Miranda et al., 2020).

In studies in children, a higher rate of hospitalisation has been observed in patients with gastrointestinal co-infections. However, it remains controversial whether these are actually infections by more than one micro-organism or are only the result of colonisation (Vergadi et al., 2021).

Escherichia coli is one of the main bacteria that contaminate food, and has been found in a variety of production systems from meat to vegetables all over the world. Contamination can occur at any

point in food processing and even during food preparation. This has become a public health problem as some of the strains found in food are resistant to antibiotics due to the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in animals in the food industry to prevent infection and promote growth. (Enciso- Martínez et al., 2022).

In 2018, a study was conducted in Mexico in which different types of fresh cheeses in the state of Hidalgo were analysed in search of pathogenic strains of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, as several cheese producers use unpasteurised milk for their production, which is a risk to public health. Mainly STEC, EPEC and ETEC were found, and strains reported resistance to amoxicillin- clavulanate, amikacin, erythromycin, gentamicin and colistin. (De La Rosa-Hernández et al., 2018). However, there are not many studies on other food types in our country.

The results obtained indicate that food contamination is still a problem at local level despite the measures that have been in place for years, such as the introduction of the Rotavirus vaccine. The population should be encouraged to reduce the consumption of street food because of the dangers of eating contaminated food, especially if it is a multi-drug resistant bacterium.

Surveillance of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), especially the O157:H7 strain, is critical because of its ability to cause severe gastrointestinal infections, particularly in children, is associated with food poisoning and has the potential to cause severe bloody diarrhoea. Many of its strains are multidrug-resistant, which complicates its treatment. In this context, the use of advanced technologies such as the FilmArray GI Panel offers key advantages for surveillance, such as rapid detection of multiple pathogens simultaneously. With high sensitivity and specificity, FilmArray allows to identify infections more efficiently than conventional methods, which is crucial to implement early interventions and prevent the spread of dangerous strains such as EPEC and EHEC especially the O157:H7 strain.

Source of funding

No funding was received for this study.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the staff of the Dorado Laboratory and Lozano Laboratories for their collaboration in obtaining the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Thanks to the staff of Laboratorios Lozano and Laboratorio Dorado for the execution of the Gastrointestinal (GI) Film-Array Panel assays of all samples. We thank them for their confidence in providing us with the database for academic purposes on a non-profit basis, with the sole condition of mentioning them in the study and their willingness to contribute to the development of this publication.

References

- Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin Blanco, N.; Fernández Castillo, S. Rotavirus vaccines: Current status and future trends. Vaccimonitor 2016, 25, 0. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.; Kabayiza, J.C.; Elfving, K.; Nilsson, S.; Msellem, M.I.; Mårtensson, A.; Björkman, A.; Bergström, T.; Lindh, M. Coinfection with enteric pathogens in east African children with acute gastroenteritis-Associations and interpretations. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2018, 98, 1566–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsalobre-Arenasa, L.; Alarcón-Cavero, T. Rapid diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract infections by parasites, viruses and bacteria. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica 2017, 35, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonkoungou, I.J.O.; Haukka, K.; Österblad, M.; Hakanen, A.J.; Traoré, A.S.; Barro, N.; Siitonen, A. Bacterial and viral etiology of childhood diarrhea in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. BMC Pediatrics 2013, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buss, S.N.; Leber, A.; Chapin, K.; Fey, P.D.; Bankowski, M.J.; Jones, M.K.; Rogatcheva, M.; Kanack, K.J.; Bourzac, K.M. Multicenter evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray gastrointestinal panel for etiologic diagnosis of infectious gastroenteritis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2015, 53, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Rosa-Hernández, M.C.; Cadena-Ramírez, A.; Téllez-Jurado, A.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Rangel-Vargas, E.; Chávez-Urbiola, E.A.; Castro-Rosas, J. Presence of multidrug-resistant shiga toxin-producing escherichia coli, Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, and enterotoxigenic escherichia coli on fresh cheeses from local retail markets in Mexico. Journal of Food Protection 2018, 81, 1748–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directorate General of Epidemiology Manual de procedimientos estandarizados para la vigilancia epidemiológica de la enfermedad diarreica aguda (EDA). Dirección General de Epidemiología, January 2022. Government of Mexico, 121.

- Enciso-Martínez, Y.; González-Aguilar, G.A.; Martínez-Téllez, M.A.; González- Pérez, C.J.; Valencia-Rivera, D.E.; Barrios-Villa, E.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F. Relevance of tracking the diversity of Escherichia coli pathotypes to reinforce food safety. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2022, 374, 109736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimprel, E.; Rodrigo, C.; Desselberger, U. Rotavirus disease: Impact of coinfections. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2008, 27 (Suppl. S1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiels, J.D.; Cremers, A.J.H.; van Bergen-Verkuyten, M.C.G.T.; Paardekoper-Strijbosch, S.J.M.; Frijns, K.C.J.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Rahamat- Langendoen, J.; Melchers, W.J.G. Impact of the BioFire FilmArray gastrointestinal panel on patient care and infection control. PLoS ONE 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaiz-Fernández, G.A.; Gómez-Peña, E.G.; Juárez-Flores, A.; Vicuña-de Anda, F.J.; Morales-Ríos, J.E.; Carrasco, O.F. Historical overview of acute diarrheal disease in Mexico and the future of its prevention. Salud Publica de Mexico 2020, 62, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacio-Mejía, L.S.; Rojas-Botero, M.; Molina-Vélez, D.; García-Morales, C.; González-González, L.; Salgado-Salgado, A.L.; Hernández-Ávila, J.E.; Hernández-Ávila, M. Overview of acute diarrheal disease at the dawn of the 21st century: The case of Mexico. Salud Publica de Mexico 2020, 62, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretary of Health. Programa de Accion Especifico de Prevencion y Control de Enfermedades Diarreicas. Programa de Accion Especifica. 2020; pp. 01–50. [Google Scholar]

- Soto Ojeda, M.; Peña Camacho, D.; Martínez Miranda, R.; Rechy Iruretagoyena, D.A.; Hernández Acevedo, G.N. Comparative identification of microorganisms isolated from hospitalised patients using the BIOFIRE® FILMARRAY® pneumonia panel plus (FA-pneumo) and traditional culture. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 2023, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, C.; Pavia, A.T.; Graham, B.; Vaughn, M.; Crisp, R.; Poritz, M.A.; Thatcher, S.; Korgenski, E.K.; Barney, T.; Daly, J.; et al. Detection of 23 gastrointestinal pathogens among children who present with Diarrhea. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2017, 6, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Miranda, D.; Akselrod, H.; Karsner, R.; Secco, A.; Silva-Cantillo, D.; Siegel, M.O.; Roberts, A.D.; Simon, G.L. Use of BioFire FilmArray gastrointestinal PCR panel associated with reductions in antibiotic use, time to optimal antibiotics, and length of stay. BMC Gastroenterology 2020, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergadi, E.; Maraki, S.; Dardamani, E.; Ladomenou, F.; Galanakis, E. Polymicrobial gastroenteritis in children. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics 2021, 110, 2240–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.X.; Zhou, Y.M.; Xu, W.; Tian, L.G.; Chen, J.X.; Chen, S.H.; Dang, Z.S.; Gu, W.P.; Yin, J.W.; Serrano, E.; et al. Impact of co-infections with enteric pathogens on children suffering from acute diarrhea in southwest China. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2016, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).