Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.1. Cholera Detection

2.1. Multi-Pathogen Amplification and Detection of Other Enteric Pathogens

2.1. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

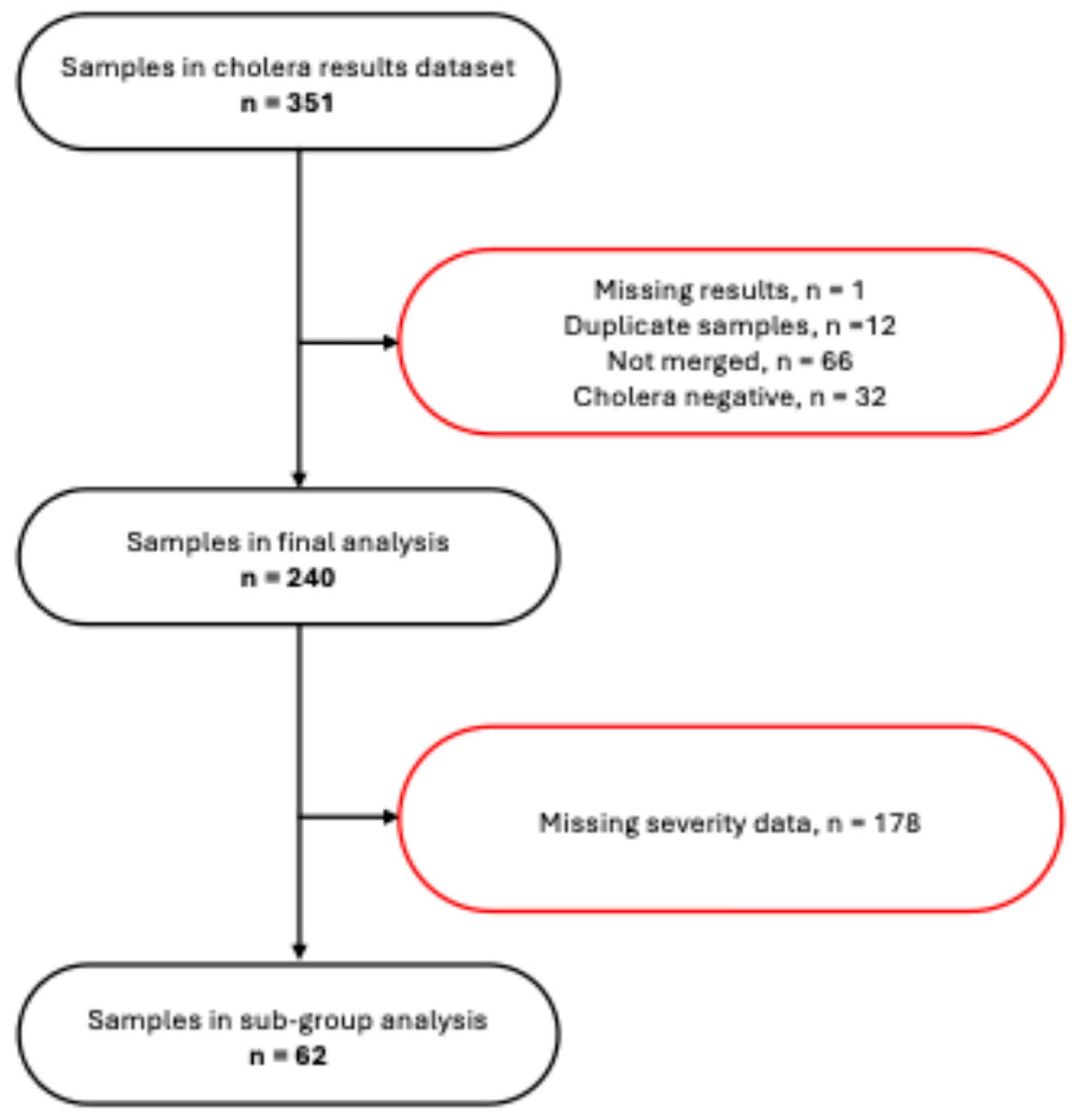

3.1. Participants’ Flow and Background Characteristics

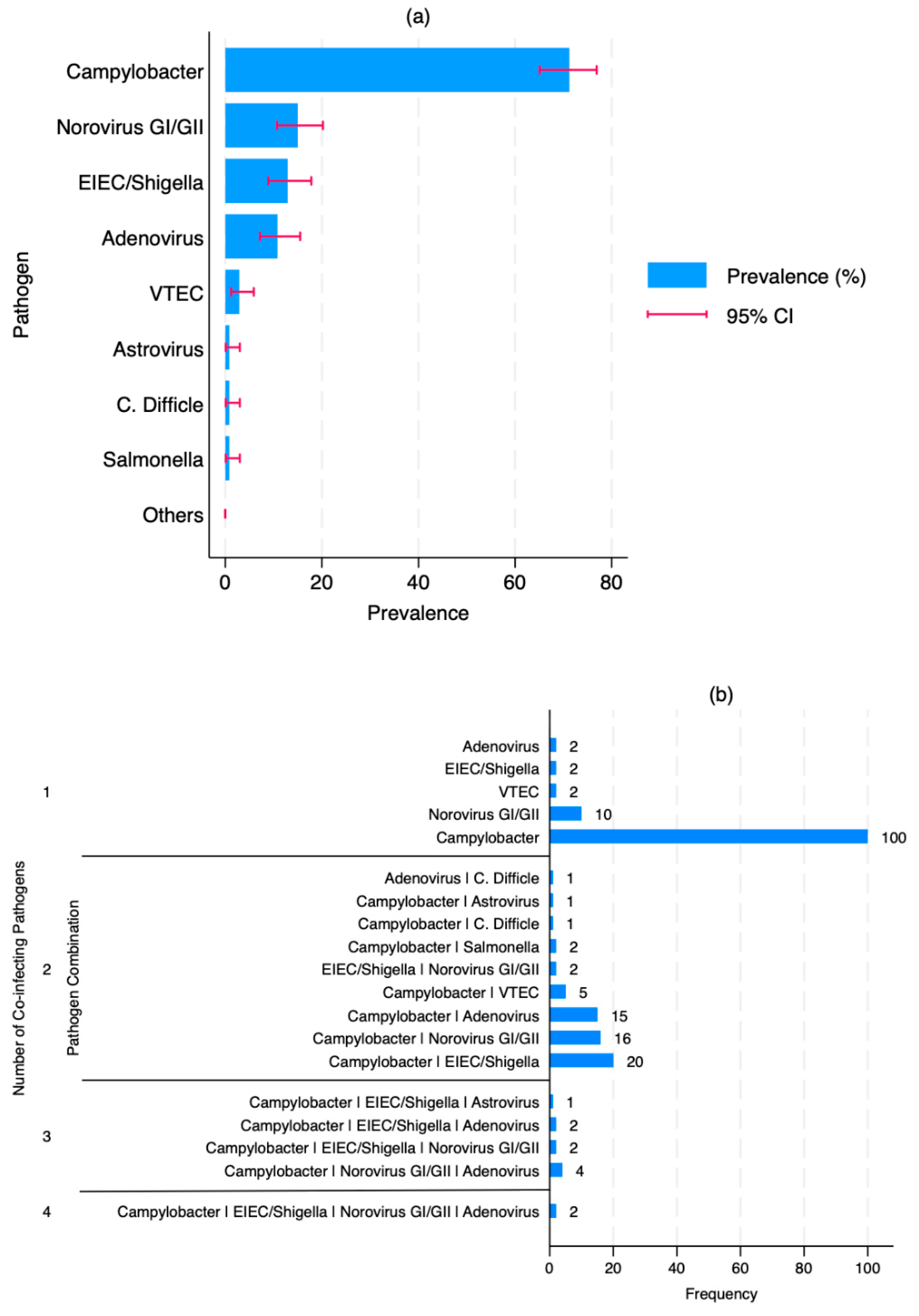

3.2. Prevalence and Patterns of Enteric co-Infections

3.2. Risk Factors of Co-Infection

3.2. Relationship Between Infection Status and Disease Severity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO) Cholera Annual Report 2023; 2024; pp. 481–496.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) TEAM Multi-Country Outbreak of Cholera, External Situation Report; 2024.

- World Health Organization (WHO-AFRO) Monthly Regional Cholera Bulletin; 2024.

- Amin, M.A.; Akhtar, M.; Khan, Z.H.; Islam, M.T.; Firoj, Md.G.; Begum, Y.A.; Rahman, S.I.A.; Afrad, M.H.; Bhuiyan, T.R.; Chowdhury, F.; et al. Coinfection and Clinical Impact of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli Harboring Diverse Toxin Variants and Colonization Factors: 2017-2022. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 151, 107365. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; Lin, Y.E. Recent Advances in the Epidemiology of Pathogenic Agents. Pathogens 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Labbate, M.; Djordjevic, S.P.; Alam, M.; Darling, A.; Melvold, J.; Holmes, A.J.; Johura, F.T.; Cravioto, A.; Charles, I.G.; et al. Indigenous Vibrio Cholerae Strains from a Non-Endemic Region Are Pathogenic. Open Biol. 2013, 3, 120181. [CrossRef]

- Montero, D.A.; Vidal, R.M.; Velasco, J.; George, S.; Lucero, Y.; Gómez, L.A.; Carreño, L.J.; García-Betancourt, R.; O’Ryan, M. Vibrio Cholerae, Classification, Pathogenesis, Immune Response, and Trends in Vaccine Development. Front. Med. 2023, 10.

- Arnaout, A.Y.; Nerabani, Y.; Sawas, M.N.; Alhejazi, T.J.; Farho, M.A.; Arnaout, K.; Alshaker, H.; Shebli, B.; Helou, M.; Mobaied, B.B.; et al. Acute Watery Diarrhoea Cases during Cholera Outbreak in Syria: A Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e082385. [CrossRef]

- Kuma, G.K.; Opintan, J.A.; Sackey, S.; Nyarko, K.M.; Opare, D.; Aryee, E.; Dongdem, A.Z.; Antwi, L.; Ofosu-Appiah, L.H.; Owusu-Okyere, G. Antibiotic Resistance Patterns amongst Clinical Vibrio Cholerae O1 Isolates from Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Infect. Control 2014, 10.

- Phiri, T.M.; Imamura, T.; Mwansa, P.C.; Mathews, I.; Mtine, F.; Chanda, J.; Salasini, M.; Funaki, T.; Otridah, K.; Musonda, K.; et al. Increased Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Vibrio Cholerae in the Capital and Provincial Areas of Zambia, January 2023–February 2024. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2025, 112, 845–848. [CrossRef]

- Chisenga, C.; Bosomprah, S.; Laban, N.M.; Mwila-K, M.J.; Simuyandi, M.; Chilengi, R. Aetiology of Diarrhoea in Children under Five in Zambia Detected Using Luminex xTAG Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel. Pediatr Infect Dis 2018, 3, 1–6.

- Bliem Rupert; Schauer Sonja; Plicka Helga; Obwaller Adelheid; Sommer Regina; Steinrigl Adolf; Alam Munirul; Reischer Georg H.; Farnleitner Andreas H.; Kirschner Alexander A Novel Triplex Quantitative PCR Strategy for Quantification of Toxigenic and Nontoxigenic Vibrio Cholerae in Aquatic Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3077–3085. [CrossRef]

- Kırdar, S.; Başara, T.; Ömürlü, İ.K. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Norovirus in Acute Gastroenteritis Cases in the Southwest Province of Turkey. Balk. Med. J. 2022, 39, 153.

- Liu, J.; Platts-Mills, J.A.; Juma, J.; Kabir, F.; Nkeze, J.; Okoi, C.; Operario, D.J.; Uddin, J.; Ahmed, S.; Alonso, P.L. Use of Quantitative Molecular Diagnostic Methods to Identify Causes of Diarrhoea in Children: A Reanalysis of the GEMS Case-Control Study. The Lancet 2016, 388, 1291–1301.

- Fletcher, S.M.; Stark, D.; Ellis, J. Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Pathogens in Sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Public Health Afr. 2011, 2, e30.

- Hlashwayo, D.F.; Sigauque, B.; Noormahomed, E.V.; Afonso, S.M.; Mandomando, I.M.; Bila, C.G. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Reveal That Campylobacter Spp. and Antibiotic Resistance Are Widespread in Humans in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0245951.

- Gahamanyi, N.; Mboera, L.E.G.; Matee, M.I.; Mutangana, D.; Komba, E.V.G. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Thermophilic Campylobacter Species in Humans and Animals in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 2092478. [CrossRef]

- Corcionivoschi, N.; Gundogdu, O. Foodborne Pathogen Campylobacter. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1241.

- Veronese, P.; Dodi, I. Campylobacter Jejuni/Coli Infection: Is It Still a Concern? Microorganisms 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, N.; Heine, L.; Ngandu, J.P.; Ledwaba, S.E.; Zitha, T.; Mudau, L.S.; Becker, P.; Traore, A.N.; Barnard, T.G. High Burden of Co-Infection with Multiple Enteric Pathogens in Children Suffering with Diarrhoea from Rural and Peri-Urban Communities in South Africa. Pathogens 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hugho, E.A.; Kumburu, H.H.; Amani, N.B.; Mseche, B.; Maro, A.; Ngowi, L.E.; Kyara, Y.; Kinabo, G.; Thomas, K.M.; Houpt, E.R.; et al. Enteric Pathogens Detected in Children under Five Years Old Admitted with Diarrhea in Moshi, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Pathogens 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Nhampossa, T.; Mandomando, I.; Acacio, S.; Quintó, L.; Vubil, D.; Ruiz, J.; Nhalungo, D.; Sacoor, C.; Nhabanga, A.; Nhacolo, A. Diarrheal Disease in Rural Mozambique: Burden, Risk Factors and Etiology of Diarrheal Disease among Children Aged 0–59 Months Seeking Care at Health Facilities. PloS One 2015, 10, e0119824.

- Breurec, S.; Vanel, N.; Bata, P.; Chartier, L.; Farra, A.; Favennec, L.; Franck, T.; Giles-Vernick, T.; Gody, J.-C.; Luong Nguyen, L.B. Etiology and Epidemiology of Diarrhea in Hospitalized Children from Low Income Country: A Matched Case-Control Study in Central African Republic. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004283.

- François, R.; Yori, P.P.; Rouhani, S.; Siguas Salas, M.; Paredes Olortegui, M.; Rengifo Trigoso, D.; Pisanic, N.; Burga, R.; Meza, R.; Meza Sanchez, G.; et al. The Other Campylobacters: Not Innocent Bystanders in Endemic Diarrhea and Dysentery in Children in Low-Income Settings. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006200. [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Nasrin, S.; Palit, P.; Sobi, R.A.; Sultana, A.-A.; Khan, S.H.; Haque, Md.A.; Nuzhat, S.; Ahmed, T.; Faruque, A.S.G.; et al. Vibrio Cholerae in Rural and Urban Bangladesh, Findings from Hospital-Based Surveillance, 2000–2021. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6411. [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S.J.; Kommedal, Ø.; Blomberg, B.; Hanevik, K.; Tellevik, M.G.; Maselle, S.Y.; Langeland, N. Comprehensive Analysis of Prevalence, Epidemiologic Characteristics, and Clinical Characteristics of Monoinfection and Coinfection in Diarrheal Diseases in Children in Tanzania. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 186, 1074–1083. [CrossRef]

- Imbrea, A.-M.; Balta, I.; Dumitrescu, G.; McCleery, D.; Pet, I.; Iancu, T.; Stef, L.; Corcionivoschi, N.; Liliana, P.-C. Exploring the Contribution of Campylobacter Jejuni to Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kemper, L.; Hensel, A. Campylobacter Jejuni: Targeting Host Cells, Adhesion, Invasion, and Survival. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 2725–2754. [CrossRef]

- Tikhomirova, A.; McNabb, E.R.; Petterlin, L.; Bellamy, G.L.; Lin, K.H.; Santoso, C.A.; Daye, E.S.; Alhaddad, F.M.; Lee, K.P.; Roujeinikova, A. Campylobacter Jejuni Virulence Factors: Update on Emerging Issues and Trends. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 45. [CrossRef]

- Makimaa, H.; Ingle, H.; Baldridge, M.T. Enteric Viral Co-Infections: Pathogenesis and Perspective. Viruses 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.H.; Chowdhary, A. Pattern of Co-Infection by Enteric Pathogenic Parasites among HIV Sero-Positive Individuals in a Tertiary Care Hospital, Mumbai, India. Indian J. Sex. Transm. Dis. AIDS 2015, 36, 40–47.

- Tay, S.C.; Aryee, E.N.O.; Badu, K. Intestinal Parasitemia and HIV/AIDS Co-Infections at Varying CD4+ T-Cell Levels. HIVAIDS Res. Treat.-Open J. 2017, 4, 40–48.

- Caputo, V.; Libera, M.; Sisti, S.; Giuliani, B.; Diotti, R.A.; Criscuolo, E. The Initial Interplay between HIV and Mucosal Innate Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14.

- Mogensen, T.H.; Melchjorsen, J.; Larsen, C.S.; Paludan, S.R. Innate Immune Recognition and Activation during HIV Infection. Retrovirology 2010, 7, 54. [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.N.; Cravioto, A.; Sur, D.; Kanungo, S. Maximizing Protection from Use of Oral Cholera Vaccines in Developing Country Settings. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 1457–1465. [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.T.; Chowdhury, F.; Calderwood, S.B.; Qadri, F.; Ryan, E.T. Immune Responses to Cholera in Children. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2012, 10, 435–444. [CrossRef]

- Qadri, F.; Bhuiyan, T.R.; Sack, D.A.; Svennerholm, A.-M. Immune Responses and Protection in Children in Developing Countries Induced by Oral Vaccines. Vaccine 2013, 31, 452–460. [CrossRef]

- Sack, D.A.; Qadri, F.; Svennerholm, A.-M. Determinants of Responses to Oral Vaccines in Developing Countries. Ann. Nestlé Engl. Ed 2008, 66, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.M.; Ramani, S.; Lynch, J.; Cooper, L.V.; Cho, H.; Bandyopadhyay, A.S.; Kirkwood, C.D.; Steele, A.D.; Kang, G. Geographic Disparities Impacting Oral Vaccine Performance: Observations and Future Directions. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2025, 219, uxae124. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Crane, M.; Zhou, J.; Mina, M.; Post, J.J.; Cameron, B.A.; Lloyd, A.R.; Jaworowski, A.; French, M.A.; Lewin, S.R. HIV and Co-Infections. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 254, 114–142. [CrossRef]

- Lawn, S. AIDS in Africa: The Impact of Coinfections on the Pathogenesis of HIV-1 Infection. J. Infect. 2004, 48, 1–12.

- Ferreira, R.B.R.; Antunes, L.C.M.; Sal-Man, N. Pathogen-Pathogen Interactions during Co-Infections. ISME J. 2025, 19, wraf104. [CrossRef]

- Walch, P.; Broz, P. Viral-Bacterial Co-Infections Screen in Vitro Reveals Molecular Processes Affecting Pathogen Proliferation and Host Cell Viability. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8595. [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K.L.; Nataro, J.P.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Nasrin, D.; Farag, T.H.; Panchalingam, S.; Wu, Y.; Sow, S.O.; Sur, D.; Breiman, R.F. Burden and Aetiology of Diarrhoeal Disease in Infants and Young Children in Developing Countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): A Prospective, Case-Control Study. The lancet 2013, 382, 209–222.

- Munoz, G.A.; Riveros-Ramirez, M.D.; Chea-Woo, E.; Ochoa, T.J. Clinical Course of Children with Campylobacter Gastroenteritis with and without Co-Infection in Lima, Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 106, 1384.

- Valentini, D.; Vittucci, A.; Grandin, A.; Tozzi, A.; Russo, C.; Onori, M.; Menichella, D.; Bartuli, A.; Villani, A. Coinfection in Acute Gastroenteritis Predicts a More Severe Clinical Course in Children. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32, 909–915.

- Lindsay, B.; Ramamurthy, T.; Gupta, S.S.; Takeda, Y.; Rajendran, K.; Nair, G.B.; Stine, O.C. Diarrheagenic Pathogens in Polymicrobial Infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 606.

- Parker, C.T.; Schiaffino, F.; Huynh, S.; Paredes Olortegui, M.; Peñataro Yori, P.; Garcia Bardales, P.F.; Pinedo Vasquez, T.; Curico Huansi, G.E.; Manzanares Villanueva, K.; Shapiama Lopez, W.V.; et al. Shotgun Metagenomics of Fecal Samples from Children in Peru Reveals Frequent Complex Co-Infections with Multiple Campylobacter Species. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010815. [CrossRef]

- Muteeb, G.; Rehman, M.T.; Shahwan, M.; Aatif, M. Origin of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance, and Their Impacts on Drug Development: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- McArdle, A.J.; Turkova, A.; Cunnington, A.J. When Do Co-Infections Matter? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 31.

- Panda, P.K. Wrong Diagnosis—Wrong Antimicrobials: Rise in Antimicrobial Resistance in Developing Countries. IDCases 2025, 41, e02313.

- Ayomide, I.T.; Promise, L.O.; Christopher, A.A.; Okikiola, P.P.; Esther, A.D.; Favour, A.C.; Agbo, O.S.; Sandra, O.-A.; Chiagozie, O.J.; Precious, A.C. The Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance on Co-INFECTIONS: Management Strategies for HIV, TB and Malaria. Int. J. Pathog. Res. 2024, 13, 117–128.

- Birger, R.B.; Kouyos, R.D.; Cohen, T.; Griffiths, E.C.; Huijben, S.; Mina, M.J.; Volkova, V.; Grenfell, B.; Metcalf, C.J.E. The Potential Impact of Coinfection on Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and Drug Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 537–544.

- Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Rossolini, G.M.; Schultsz, C.; Tacconelli, E.; Murthy, S.; Ohmagari, N.; Holmes, A.; Bachmann, T.; Goossens, H.; Canton, R. Key Considerations on the Potential Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Antimicrobial Resistance Research and Surveillance. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 115, 1122–1129.

| Characteristic | Total N=240 |

| n (% of total) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 112 (46.7) |

| Female | 77 (32.1) |

| Missing | 51 (21.2) |

| Age (Years), Median (IQI*) | 26 (14-38) |

| Age group (Years) | |

| < 15 | 47 (19.6) |

| 15-24 | 41 (17.1) |

| 25-34 | 41 (17.1) |

| 35+ | 59 (24.6) |

| Missing | 52 (21.7) |

| Facility | |

| Chipata | 26 (10.8) |

| George | 62 (25.8) |

| Heroes | 54 (22.5) |

| Levy | 8 (3.3) |

| Matero | 90 (37.5) |

| Vaccinated against cholera | |

| No | 18 (7.5) |

| Yes | 4 (1.7) |

| Missing | 218 (90.8) |

| HIV Status | |

| Negative | 215 (89.6) |

| Positive | 19 (7.9) |

| Missing | 6 (2.5) |

| * Interquartile Interval |

| Characteristic | Co-Infection (n=190, 79.2%) | p-Value | Unadjusted PR* | p-Value | Adjusted PR | p-Value |

| n (% of row total) | Ratio (95% CI) | Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 87/112 (77.7) | 0.865 a | Reference | 0.866 | ||

| Female | 59/77 (76.6) | 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) | ||||

| Age group (Years) | ||||||

| < 15 | 41/47 (87.2) | 0.080 a | Reference | 0.098 | Reference | 0.068 |

| 15-24 | 28/41 (68.3) | 0.78 (0.62, 0.99) | 0.75 (0.58, 0.96) | |||

| 25-34 | 29/41 (70.7) | 0.81 (0.65, 1.02) | 0.80 (0.64, 1.00) | |||

| 35+ | 49/59 (83.1) | 0.95 (0.81, 1.12) | 0.92 (0.78, 1.09) | |||

| Vaccinated against cholera | ||||||

| No | 14/18 (77.8) | 1.000 b | Reference | 0.910 | ||

| Yes | 3/4 (75.0) | 0.96 (0.51, 1.81) | ||||

| HIV Status | ||||||

| Negative | 166/215 (77.2) | 0.084 b | Reference | 0.002 | Reference | |

| Positive | 18/19 (94.7) | 1.23 (1.08, 1.40) | 1.27 (1.07, 1.51) | 0.008 | ||

| * PR = Prevalence Ratio | ||||||

| a = Chi2 | ||||||

| b = Fisher's exact |

| Characteristic | Total N=62 |

| n (% of total) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 30 (48.4) |

| Female | 32 (51.6) |

| Age, Median (IQI*) | 27 (20-40) |

| Age group | |

| < 15 | 1 (1.6) |

| 15-24 | 9 (14.5) |

| 25-34 | 15 (24.2) |

| 35+ | 16 (25.8) |

| Vaccinated against cholera | |

| No | 14 (22.6) |

| Yes | 4 (6.5) |

| Missing | 44 (71.0) |

| HIV Status | |

| Negative | 53 (85.5) |

| Positive | 9 (14.5) |

| Infection status | |

| Mono-infection | 14 (22.6) |

| Co-infection | 48 (77.4) |

| * Interquartile Interval |

| Characteristic | Moderate-to-severe (n=33, 53.2%) | p-Value | Unadjusted PR* | p-Value | Unadjusted PR* | p-Value |

| n (% of row total) | Ratio (95% CI) | Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Infection status | ||||||

| Mono-infection | 10 (71.4) | 0.121 | Reference | 0.080 | Reference | 0.014 |

| Co-infection | 23 (47.9) | 0.67 (0.43, 1.05) | 0.59 (0.38, 0.90) | |||

| * PR = Prevalence Ratio | ||||||

| Ratios adjusted for sex, age group, and HIV status | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).