1. Introduction

In Japan, natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis and typhoons occur frequently. These disasters may cause significant damage to communication infrastructure such as base stations and cables. In 2011, approximately 29,000 base stations were reported being shut down after the Great East Japan Earthquake [

1]. In addition, damages to the access to the outside world result in the occurrence of isolated disaster areas [

2]. Due to the cutoff of the national highway, Yamamoto, Miyagi was completely isolated until 4 days after the disaster [

3].

Because of the difficulty in obtaining disaster information from the isolated disaster areas, the early deployment of rescue events is hindered. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce communication systems which do not rely on existing communication infrastructures on the ground.

Non-terrestrial networks (NTN), which include platforms operating between 0.1 to 2000 km altitudes such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), high altitude platforms (HAPs), low earth orbit satellites (LEO) etc., are nowadays popular as post-disaster communication solutions. For non-real-time temporary data collection mission in isolated disaster areas, the use of UAVs, which are also commonly known as drones, is considered suitable because of their low cost, high mobility and high flexibility.

2. Related Works

UAV-based data collection has been discussed in several previous studies as summarized in

Table 1. In [

4], the article dealt with the issue of improving rural connectivity. Path planning and UAV relays were conducted to improve quality in rural area. Unfortunately, the paper only focused on the connectivity. In [

5], the authors considered an obstacle-aware deployment of UAV, where path optimization in obstacle-heavy environments was conducted. UAV in this paper was employed as a relay rather than a data collector as considered in this paper. In [

6], the authors proposed a disaster monitoring system via multi-UAV coordination. The paper only focused on UAV coordination but did not consider how to optimize data collection. In [

7], UAV-based surveillance system was introduced where multi-UAV collaboration was done via Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL). Since this system was specific to surveillance, it is not generally applicable for the scenario of data collection considered in this paper.

There were also works that focused on the use of UAVs for data collection. The author of [

8] optimized the 2-dimensional trajectory with multi-armed bandit (MAB) algorithm, considering the energy consumption of the UAV and the UEs, to maximize the throughput. In [

9], the throughput maximization problem is transformed to a constrained Markov decision-making process (CMDP), considering the energy consumption of the UEs. In addition, the author of [

10] aimed to minimize the mission completion time by optimizing the transmission power of UEs and the flight trajectory. In [

11], flight altitude, trajectory, velocity and link scheduling are considered for completion time minimization. Unfortunately, all these works were restricted to the 2D optimization of trajectory as compared to the 3D trajectory optimization in this paper. The relation between the flight altitude and the coverage is shown in [

12] that higher altitude brings larger coverage via a high-altitude platform (LAP) rather than a UAV. In [

13], 3-dimensional locations of the UAV are decided with k-means clustering, without the discussion on data transmission. In [

14], a 3-dimensional trajectory is optimized to maximize the energy efficiency, considering the presence of wind. The author of [

15] proposed a maximal weighted area (MWA) algorithm to solve the 3-dimensional placement problem of UAV base stations. Unfortunately, these works did not discuss on the completion time or the time restriction of collecting data.

Different from the above-mentioned conventional works, in this article, we focus on the 3D optimization of the flight altitude of the UAV, examining the completion time reduction effect by adopting the 3-dimensional trajectory and a scheduling mechanism to minimize the time required for the data collection process.

3. System Architecture

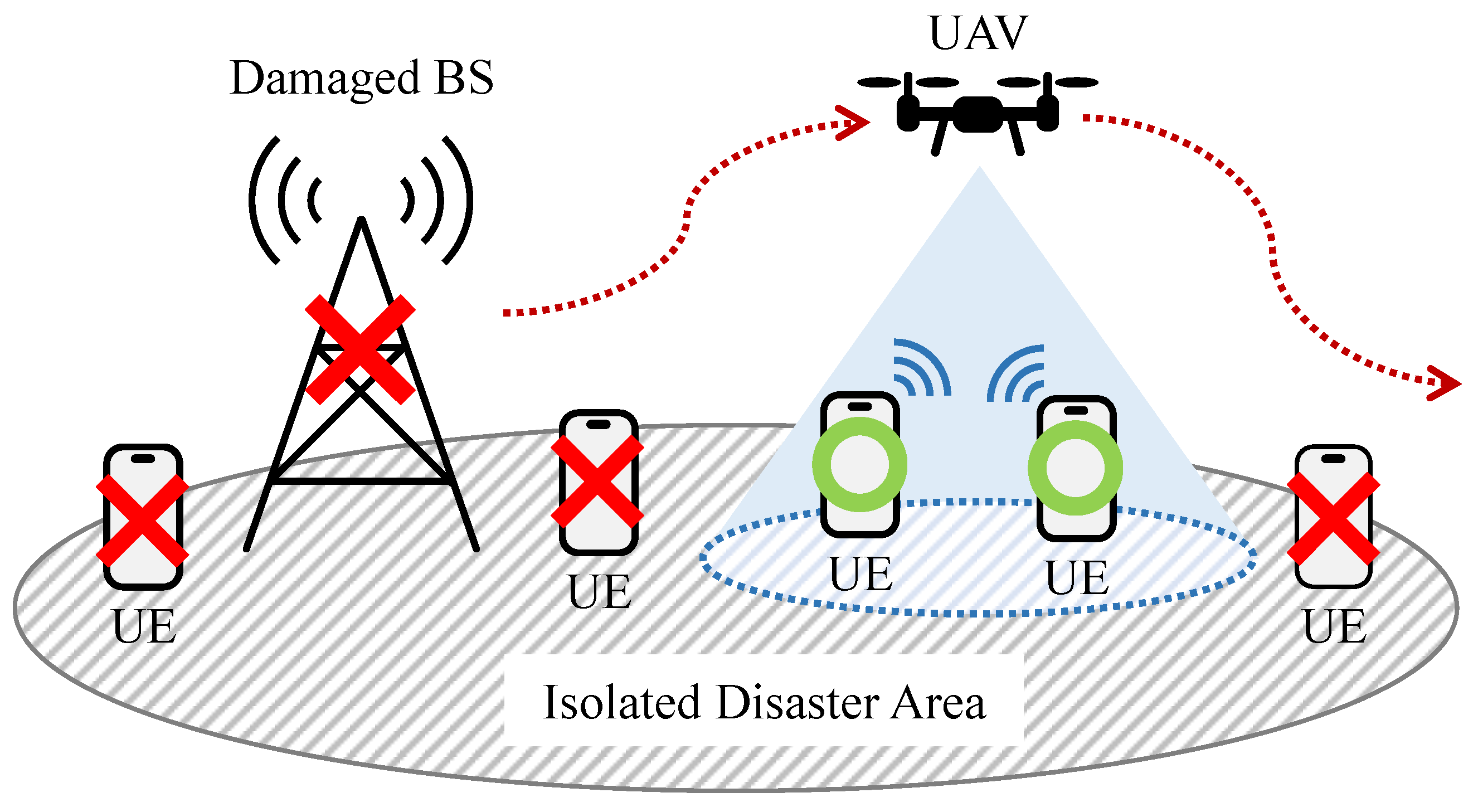

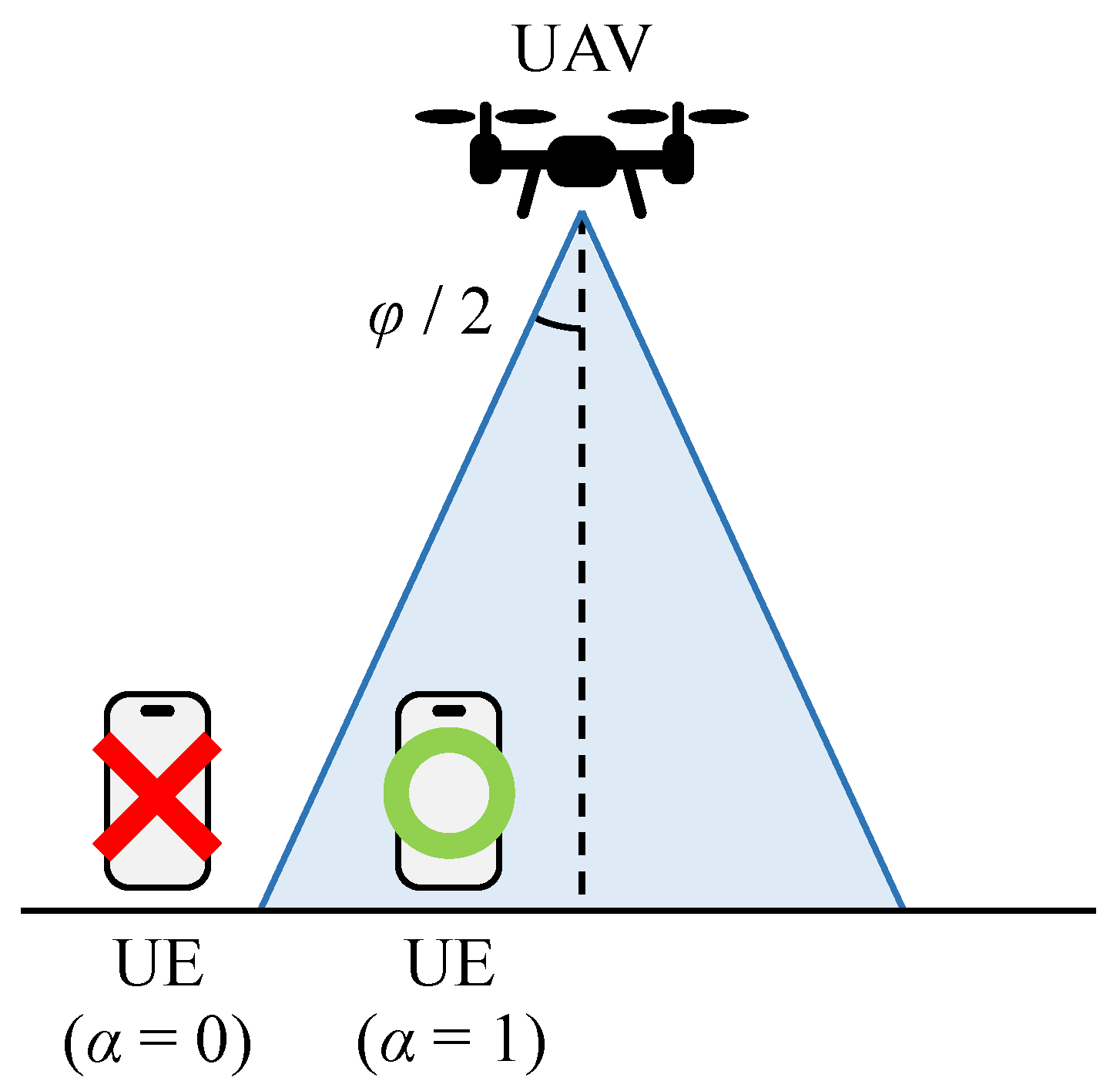

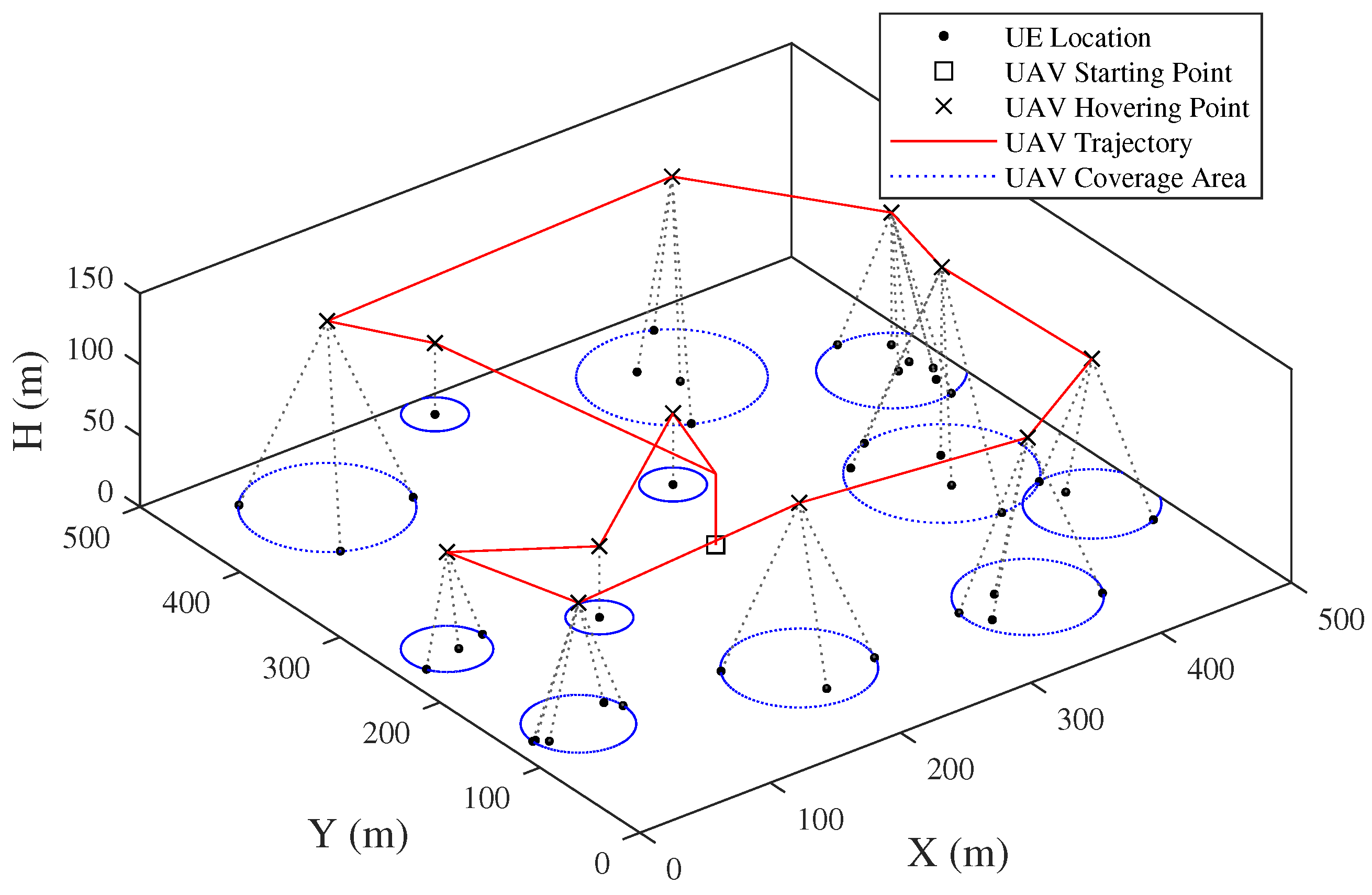

As shown in

Figure 1, the simulation scenario in this article is that a single UAV collects data from user equipments (UE) such as smartphones and tablets owned by users in the isolated disaster area.

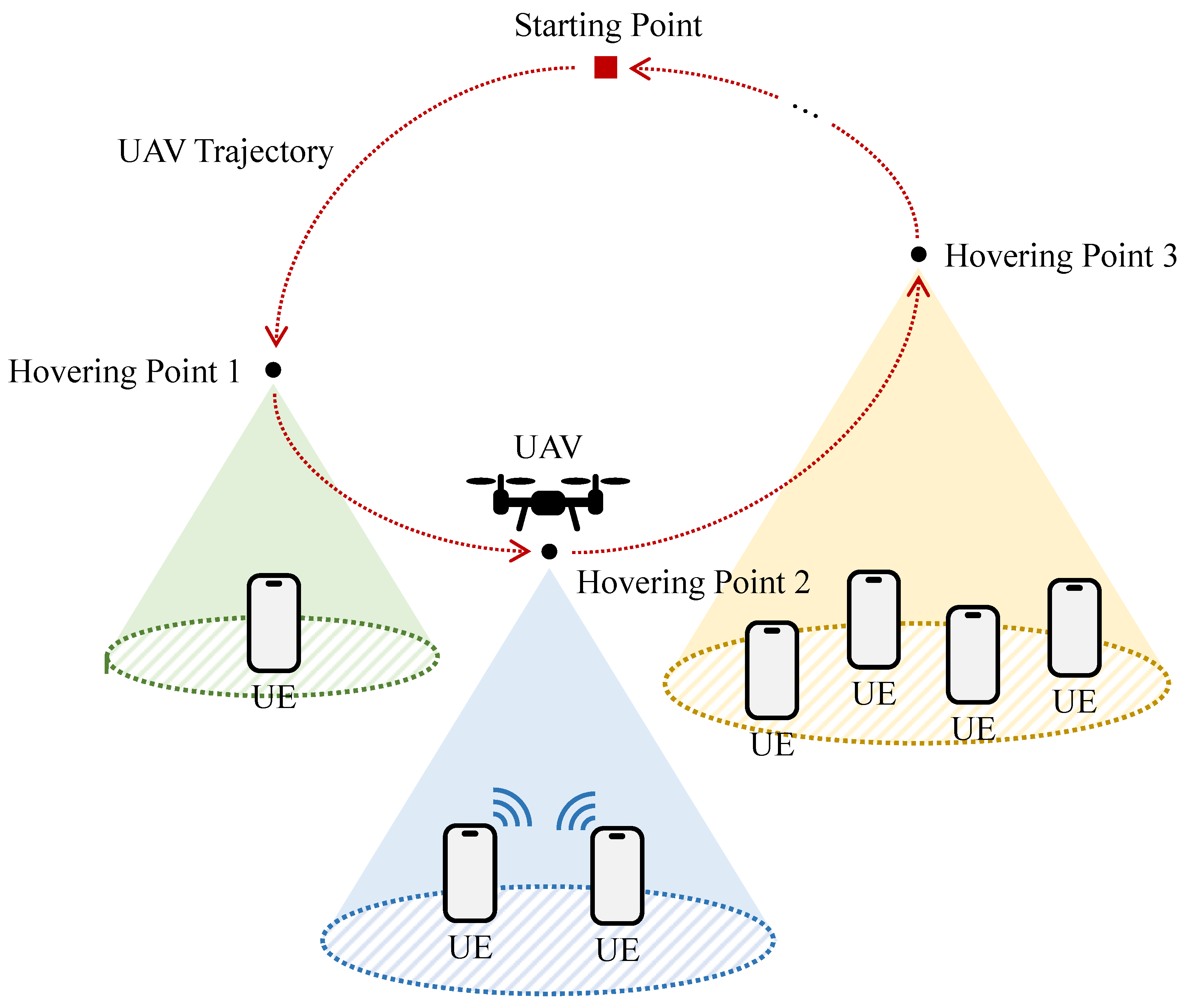

The UAV is assumed to collect data from the UEs when hovering, and there is no data transmission between the UAV and the UEs during flight. As shown in

Figure 2, the 3-dimensional trajectory proposed by this article optimizes the UAV’s flight altitude. In areas with dense UE distribution, the UAV’s flight altitude is increased to achieve a larger coverage area. In contrast, in areas with scattered UE distribution, the UAV’s flight altitude is reduced to achieve higher throughput.

The detailed process of the data collection mission is shown as below:

- 1.

Collect location information of UEs by other systems such as HAPS, LEO etc.;

- 2.

The UAV departures from the starting point;

- 3.

The UAV flies to the next hovering point;

- 4.

The UAV collects data from all covered UEs;

- 5.

Repeat 3~4 until all UEs’ data is collected;

- 6.

The UAV return to the starting point;

- 7.

Send the collected data to the disaster response headquarter.

Note that for simplicity, 1 and 7 are not covered in this article.

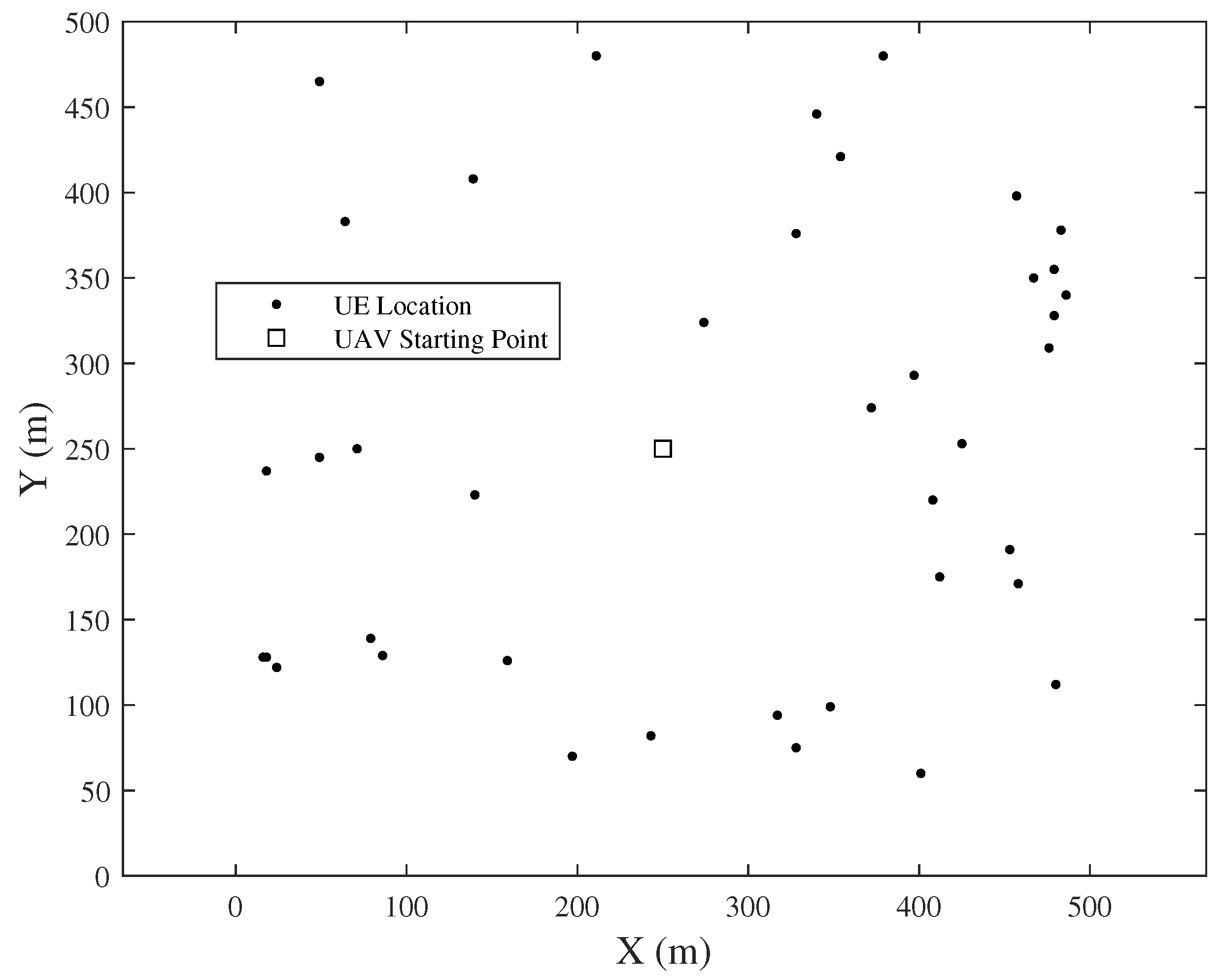

For simulation, a

m flat urban area is assumed as the simulation environment. As the sample shown in

Figure 3,

M UEs are randomly distributed in this area. The starting point of the UAV is set in the center of the area as

, and the location of the UAV at time

t is assumed as

, the location of the

-UE is assumed as

. Note that for simplicity, the UEs are assumed not to change their location.

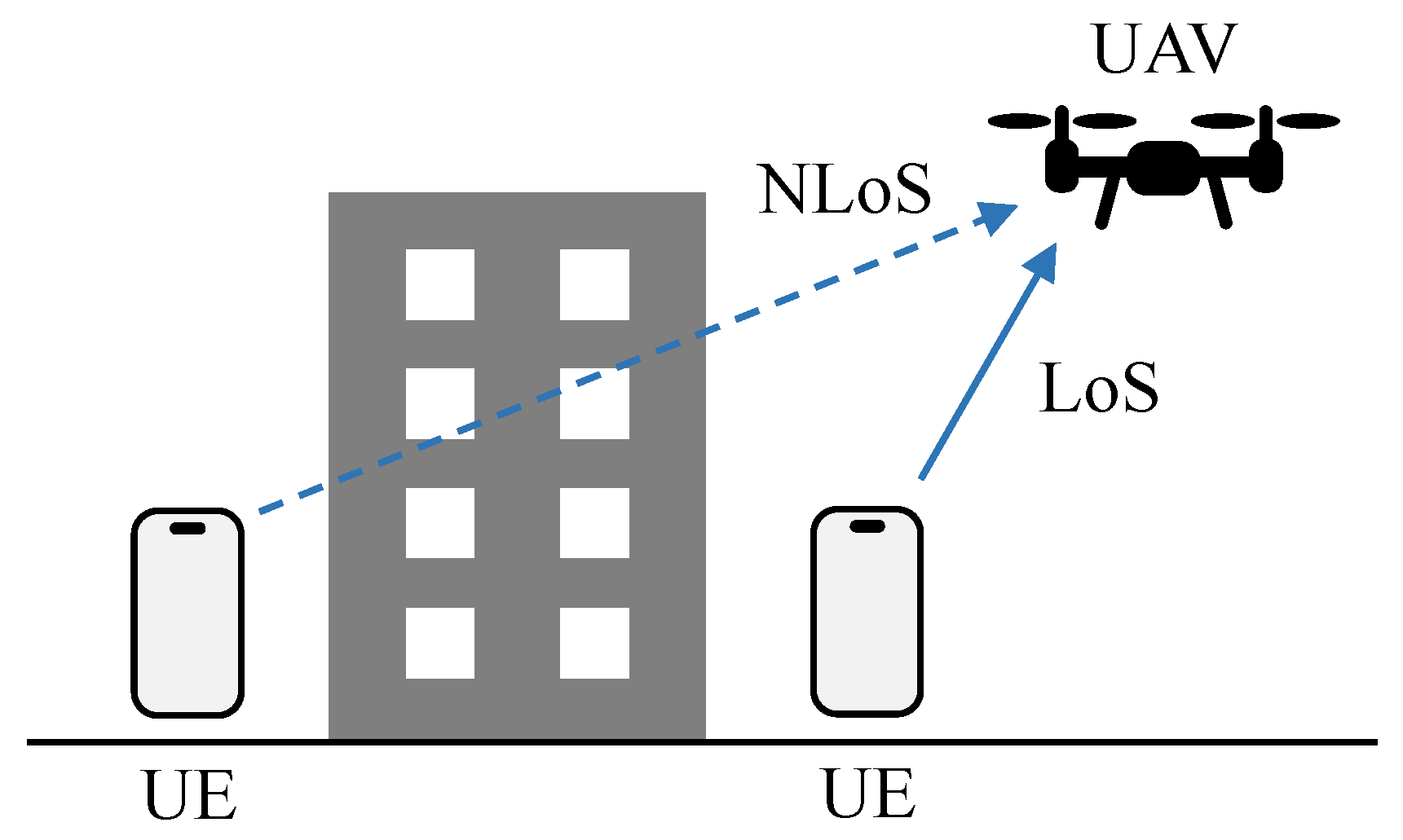

We adopt the 2.4 GHz band for data transmission, because it can be easily integrated with the hardware of UEs nowadays. For simplicity, the shape of the buildings is ignored. Thus, the data transmission model between the UAV and the UEs is defined with the possibilities of Line-of-Sight (LoS) and Non-Line-of-Sight (NLoS) propagation. As shown in

Figure 4, LoS propagation occurs only when there is no obstacle between the UAV and the UE.

The LoS and NLoS propagation loss between the UAV and the

m-UE at time

t ,

are given below:

where

is the free space propagation loss (FSPL),

,

are respectively the LoS and NLoS excessive loss,

is the Euclidean distance between the UAV and the

m-UE at time

t.

According to [

12], the possibilities of LoS and NLoS propagation

,

are given below:

where

a,

b are environment S-curve parameters,

is the elevation angle from the

m-UE to the UAV.

Thus, the propagation loss between the UAV and the

m-UE at time

t can be calculated by:

From the Shannon–Hartley Theorem [

16], the maximum data rate between the UAV and the

m-UE at time

t can be calculated by:

where

is the signal noise ratio (SNR) between the UAV and

m-UE, the

is an indicator decided by the connection status between the UAV and

m-UE, which is defined as below:

In addition, the simulation parameters used in this article are shown in

Table 2.

4. Methods

The 3-dimensional trajectory optimization is divided into 2 parts: hovering points placement and trajectory decision. The locations of the hovering points are decided by the distribution of the UEs. After the hovering points are decided, the trajectory which passes through all hovering points with the minimum time is needed to be decided, which can be considered as a classic traveling salesman problem (TSP).

4.1. K-Means Clustering for Placement of Hovering Points

The k-means clustering is known as a non-hierarchical cluster analysis method, classifying multiple elements into

k clusters. K-means has been adopted by related studies to UAV communication networks, such as [

17], where it is used to solve the placement problem of multiple UAV base stations. In this article, k-means is considered feasible to solve the placement problem of the UAV hovering points.

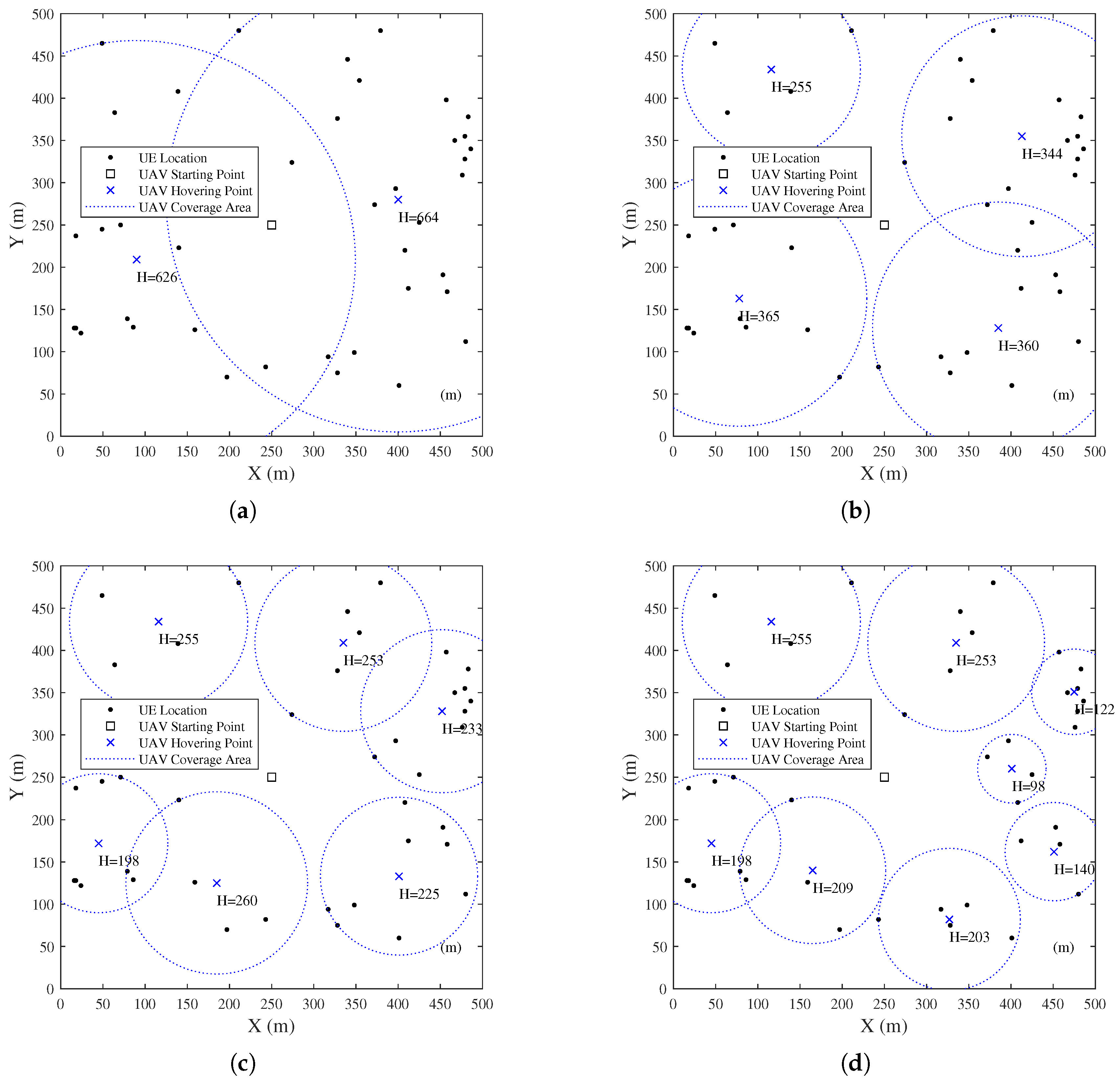

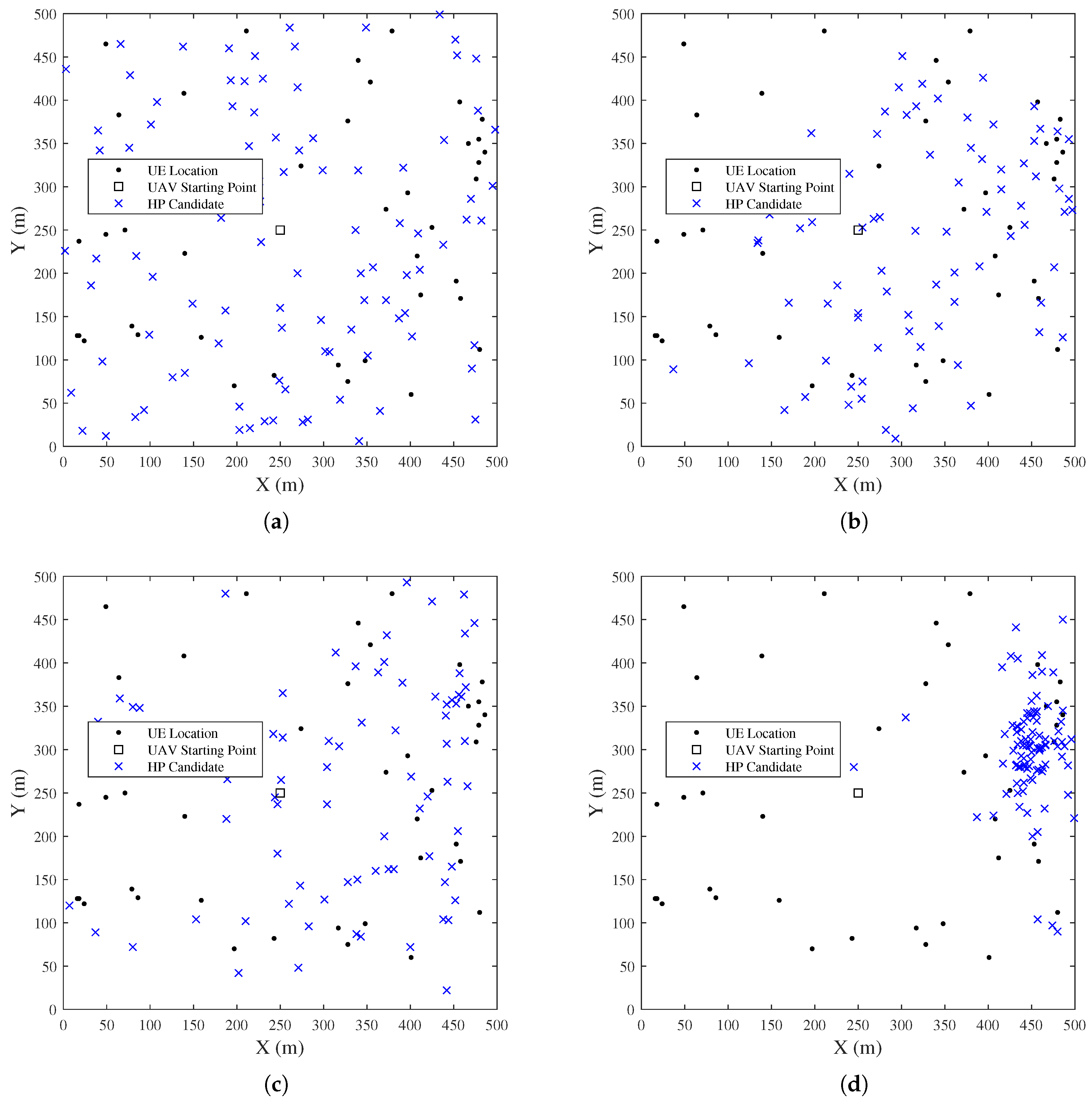

Now apply k-means to the UE distribution shown in

Figure 3, the UE clustering by k-means with varying number of clusters

k is shown in

Figure 6. The dotted circles represent the required coverage area to cover all UEs belonging to each cluster, while the locations of the hovering points are assumed as the center points of the clusters. However, it is suggested from [

17] that the center points of the clusters are not the optimal locations for the hovering points. As the results shown in

Figure 6, there are empty areas with no UE covered in the coverage areas. To enhance the transmission efficiency, a geometric method, the minimum inclusion circle, was introduced by [

17], while it only works when the UEs are all on the same plane.

In this article, we proposed to search for the optimal location of hovering points through numerical computation. Hill climbing algorithm (HC), a simple local search method, is adopted. Minimum SNRs between the UAV and the UEs from each candidate point are calculated. And then the location of the hovering points will be updated to the new location with the largest minimum SNR, until the minimum SNR does not change any more.

However, the k-means clustering has 2 critical problems:

Therefore, we proposed a sequential k-means clustering method to search for the minimum k. If the result of the UE clustering satisfies the condition of the UAV’s flight altitude, the present k will be adopted. Otherwise, the operation will continue by increasing k.

4.2. Genetic Algorithm for Placement of Hovering Points

To fundamentally solve the problems of traditional clustering methods, we transform the hovering points placement problem to a location set covering problem (LSCP) [

18], which is commonly used to solve the placement problems of public facilities. The definition of LSCP is given as follows:

According to the definition of LSCP, the problem can be described as searching for the minimum number of hovering points that enable covering all UEs in a certain area. The coverage radius of the facility is defined as the maximum coverage radius of the UAV, which is 62.132 m, based on the limitation of UAV’s flight altitude in this article.

The basic strategy to solve the LSCP in this article is the greedy algorithm, which continues to select the location of the hovering point that can cover the largest number of UEs until all UEs have been covered. Although method that calculates all candidate points is simple for implementation, large number of candidates are needed to obtain the accurate solution, bringing huge amount of calculation.

Therefore, in this section, we use the genetic algorithm (GA) to search for the optimal locations for hovering points. The genetic algorithm is a search algorithm based on the principles of biological evolution, incorporating genetic operations such as selection, crossover and mutation.

Selection

Roulette wheel selection is adopted for selection. The probability of the individual

i being selected

is given as follows:

where

is the fitness function of

i, which is defined as the number of UEs that can be covered from the location indicated by

i. Parents of the next generation are selected according to the magnitude of the fitness function. Individuals with better fitness function are more likely to survive in the next generation.

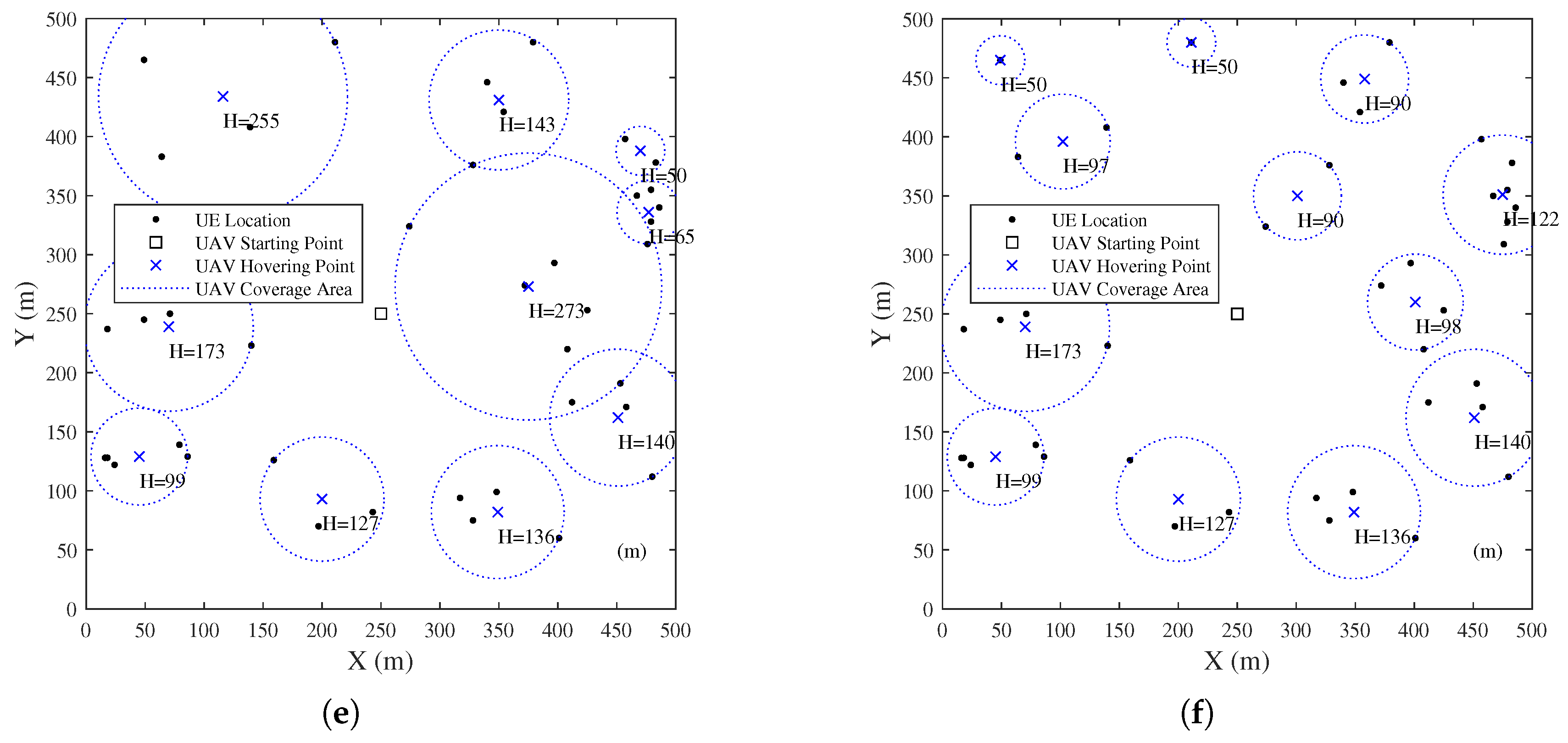

Crossover

Blend crossover (BLX-

) [

19] is adopted for crossover, with a crossover rate of 0.9. As shown in

Figure 7, the coordinates of child individuals are generated in the area decided by the coordinates of parent individuals and parameter

. If we assume the coordinates of parent individuals are (

,

), (

,

), the coordinates of child individuals (

,

), (

,

) will be generated in the rectangular area created by point A, B, C, D as follows:

where

,

,

,

,

,

are given as follows:

Mutation

Gaussian mutation is adopted for mutation, with a mutation rate of 0.005. Random individuals are generated according to the Gaussian distribution, preserving the diversity of the individuals.

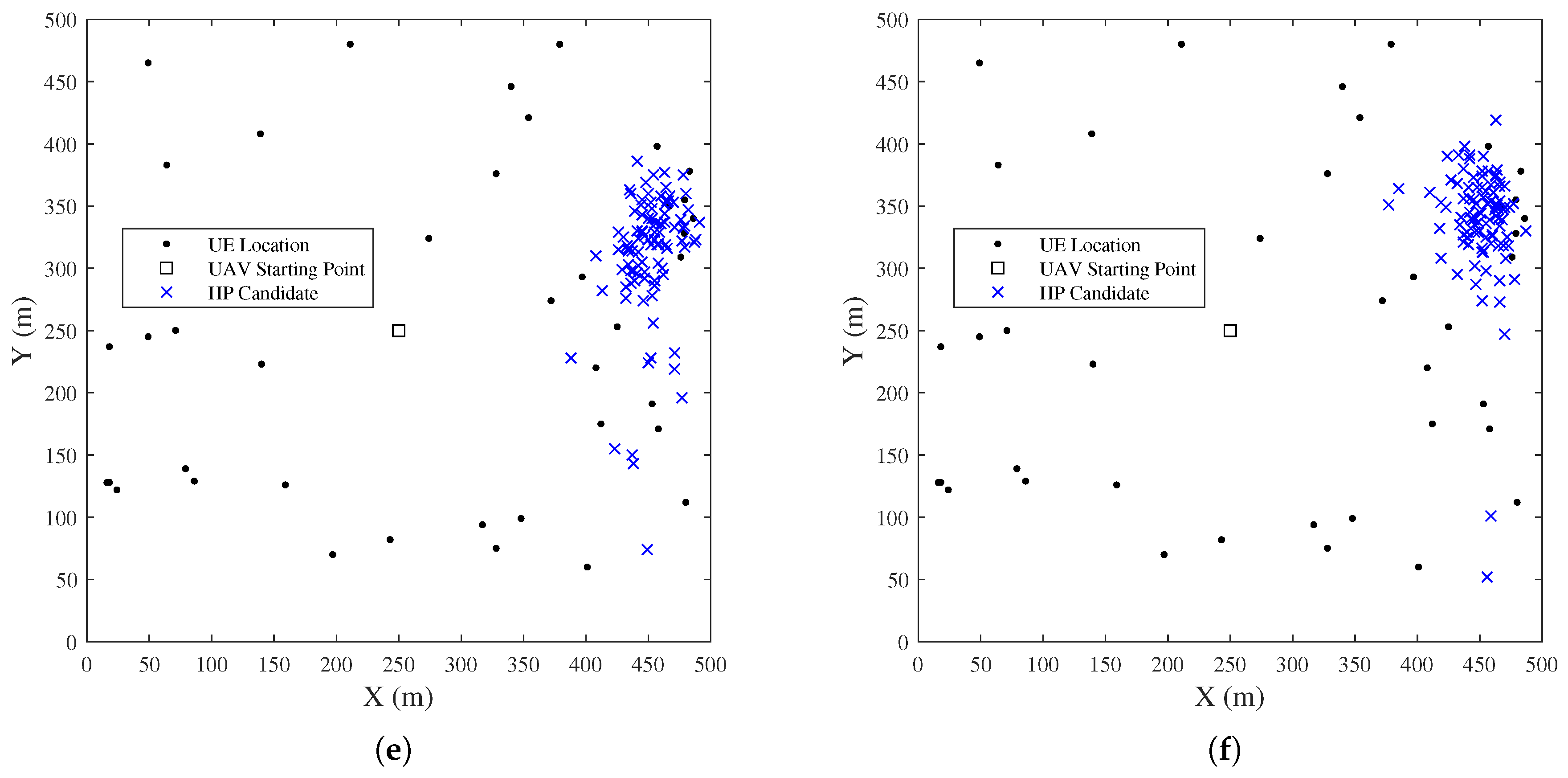

The process of searching for the optimal hovering point using GA is shown in

Figure 8. From

Figure 8, in contrast to the first generation, when the individuals are randomly distributed throughout the area, the individuals converge to where the UEs are densest after several generations. In this article, the maximum number of generations is set as 100. When it reaches the 100th generation, the individual with the highest fitness function will be selected as the hovering point. Then, the UEs which are already covered will be removed from the search by GA, and this process will be repeated until all remaining UEs are covered. While the result by GA is based on the maximum coverage radius of the UAV, i.e. the flight altitude is 150 m, it is necessary to apply the hill climbing algorithm to optimize the flight altitude.

4.3. Nearest Neighbor Search for Trajectory Decision

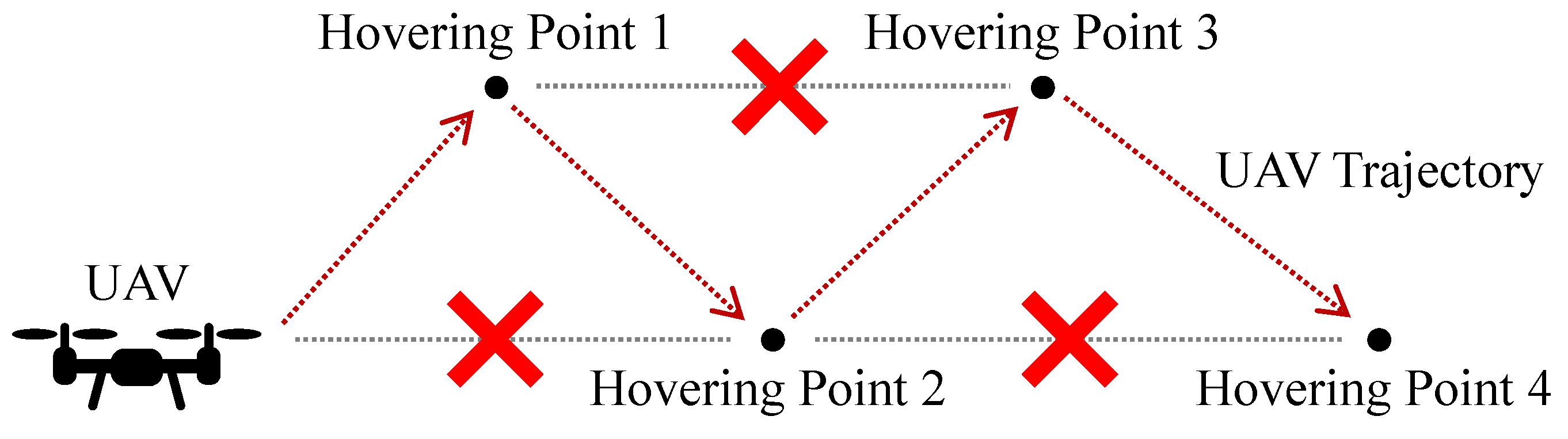

After the hovering points are decided, the trajectory which passes through all hovering points with the minimum flight time is needed to be decided. However, the TSP is known as an NP-hard problem, which needs huge amount of calculations to achieve the precise solution. Thus, for simplicity, we adopted the nearest neighbor search (NN), which is an approximate algorithm used in many applications.

As shown in

Figure 9, according to the concepts of NN, the UAV always selects the nearest hovering point as the next destination.

5. Simulation Results

5.1. Placement of Hovering Points

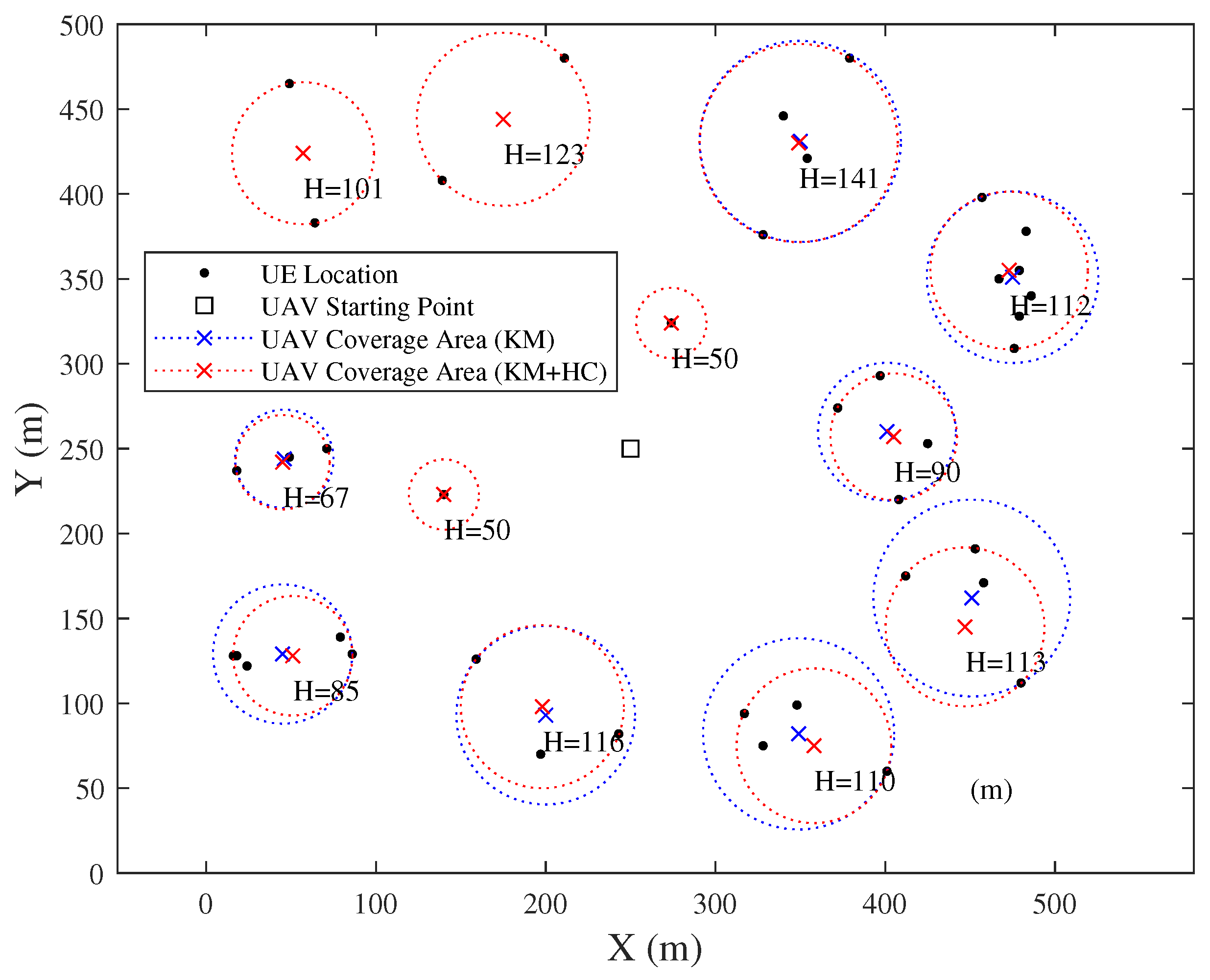

The placement of hovering points by sequenced k-means clustering is shown in

Figure 10, where the blue and red dotted circles respectively indicate the coverage area before and after adopting the hill climbing algorithm. In this case, 12 is the smallest

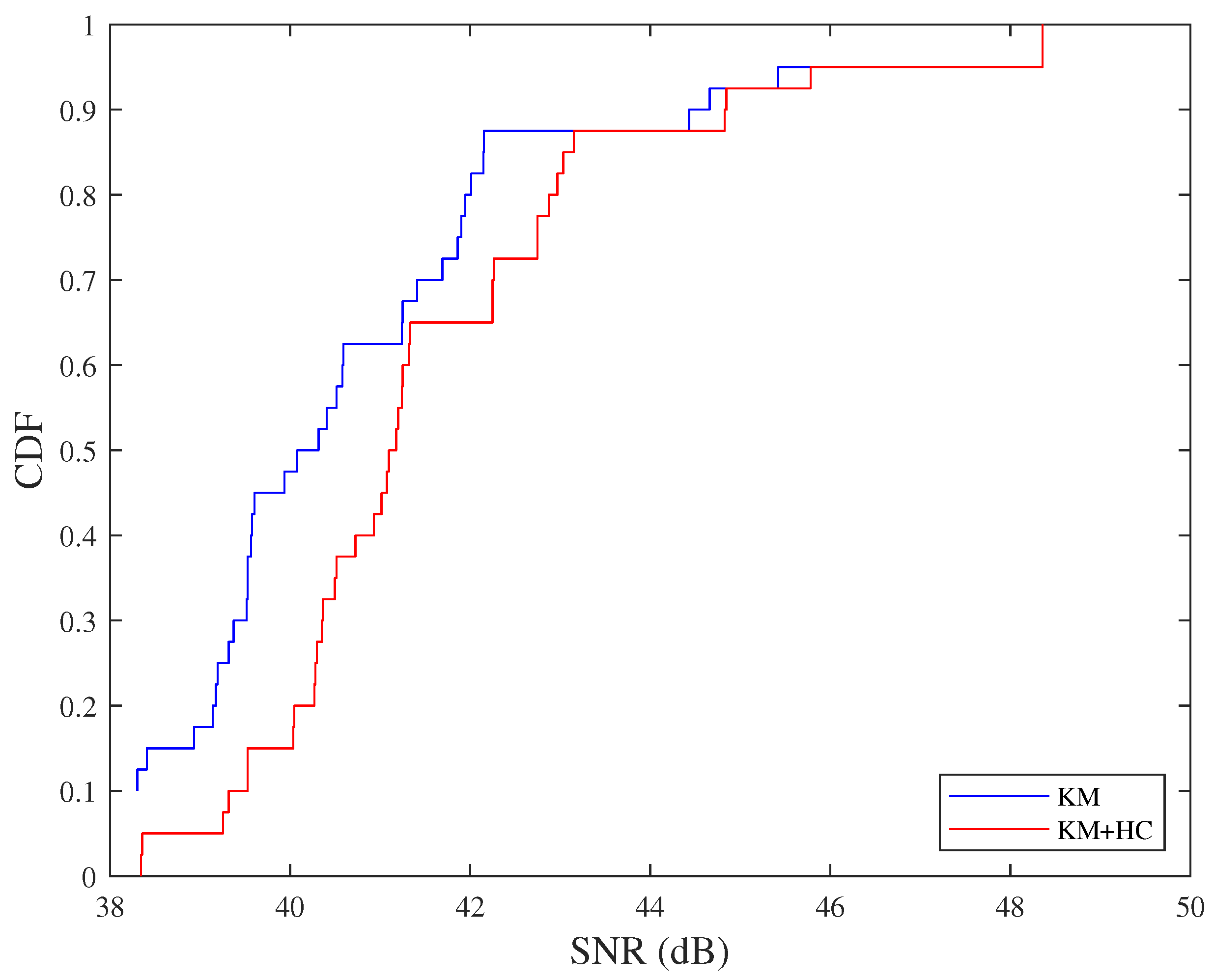

k to satisfy the flight altitude limitation. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the SNR before and after adopting the hill climbing algorithm is shown in

Figure 11. From

Figure 11, we can know that the hill climbing algorithm successfully optimized the UAV’s flight altitude, achieving larger SNRs.

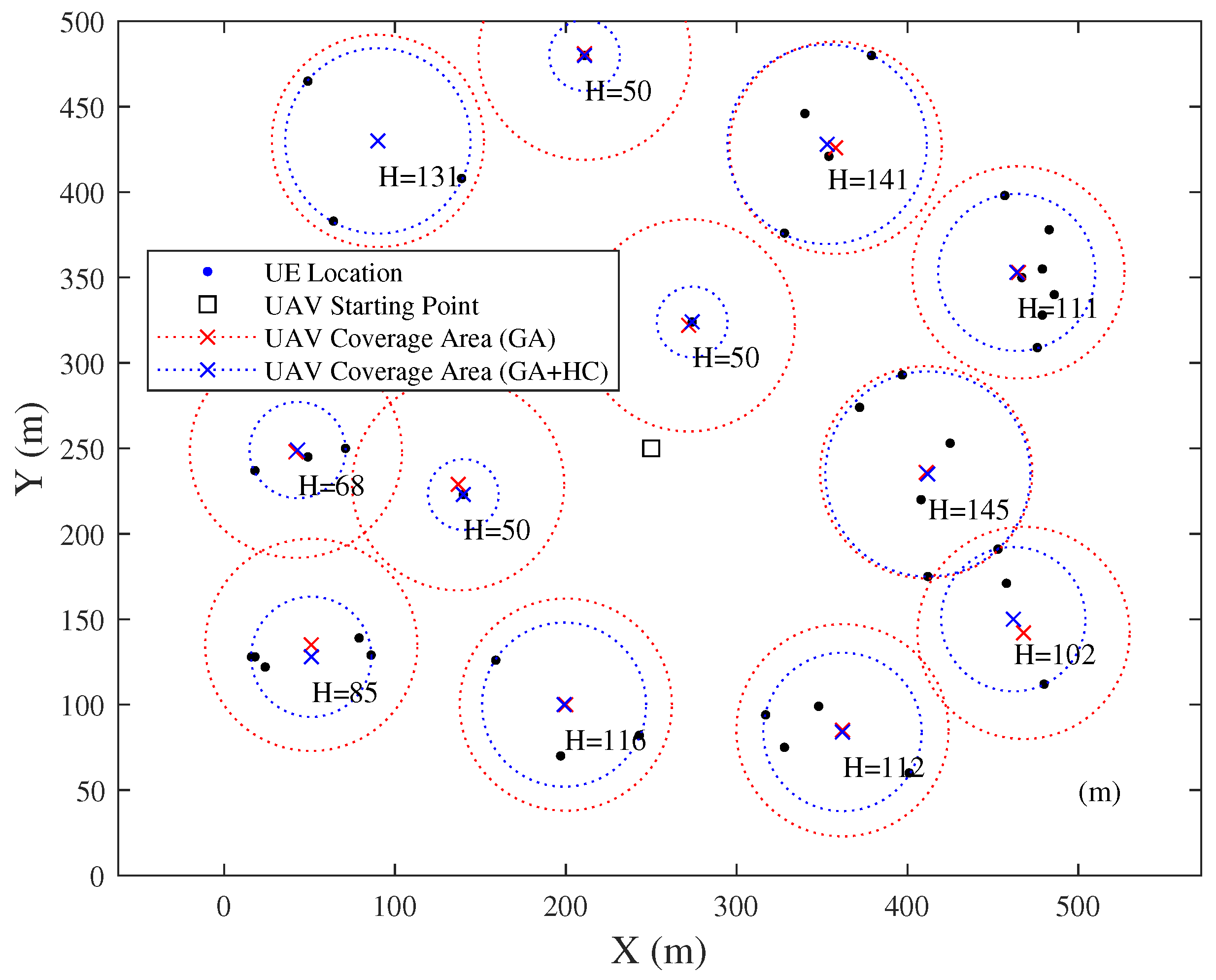

Then, the placement of hovering points by GA is shown in

Figure 12. The solution of the LSCP with the maximum flight height of 150 m, which is shown by the red dotted circles, is firstly obtained. And then, the hill climbing algorithm is adoted to optimize the UAV’s flight altitude below 150 m, which is shown by the blue dotted circles.

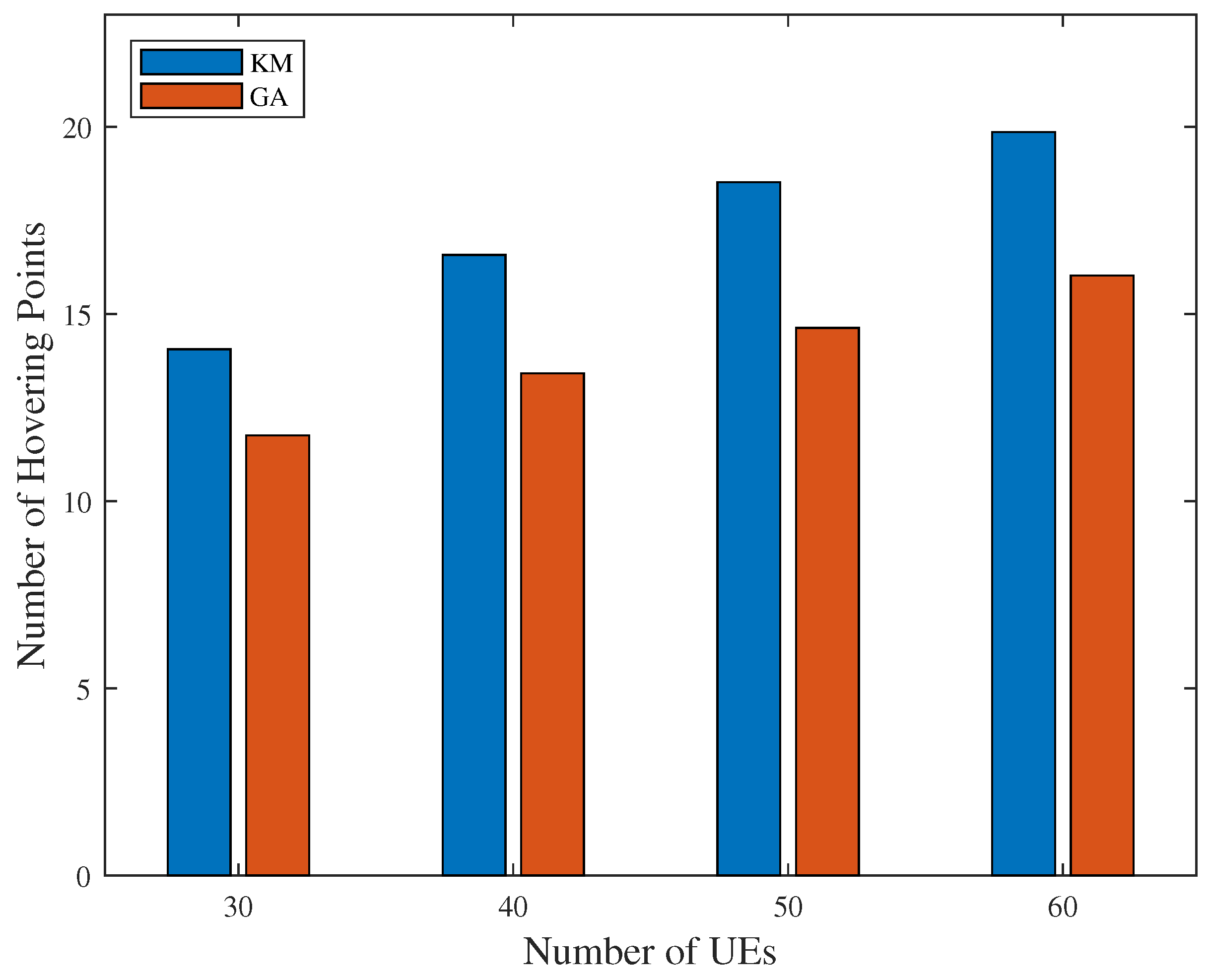

The minimum number of hovering points obtained by sequenced k-means and GA is shown in

Figure 13. From

Figure 13, comparing to the traditional k-means clustering, the result by GA covers the same number of UEs with fewer hovering points, which indicates the improvement of the efficiency.

5.2. Trajectory Optimization

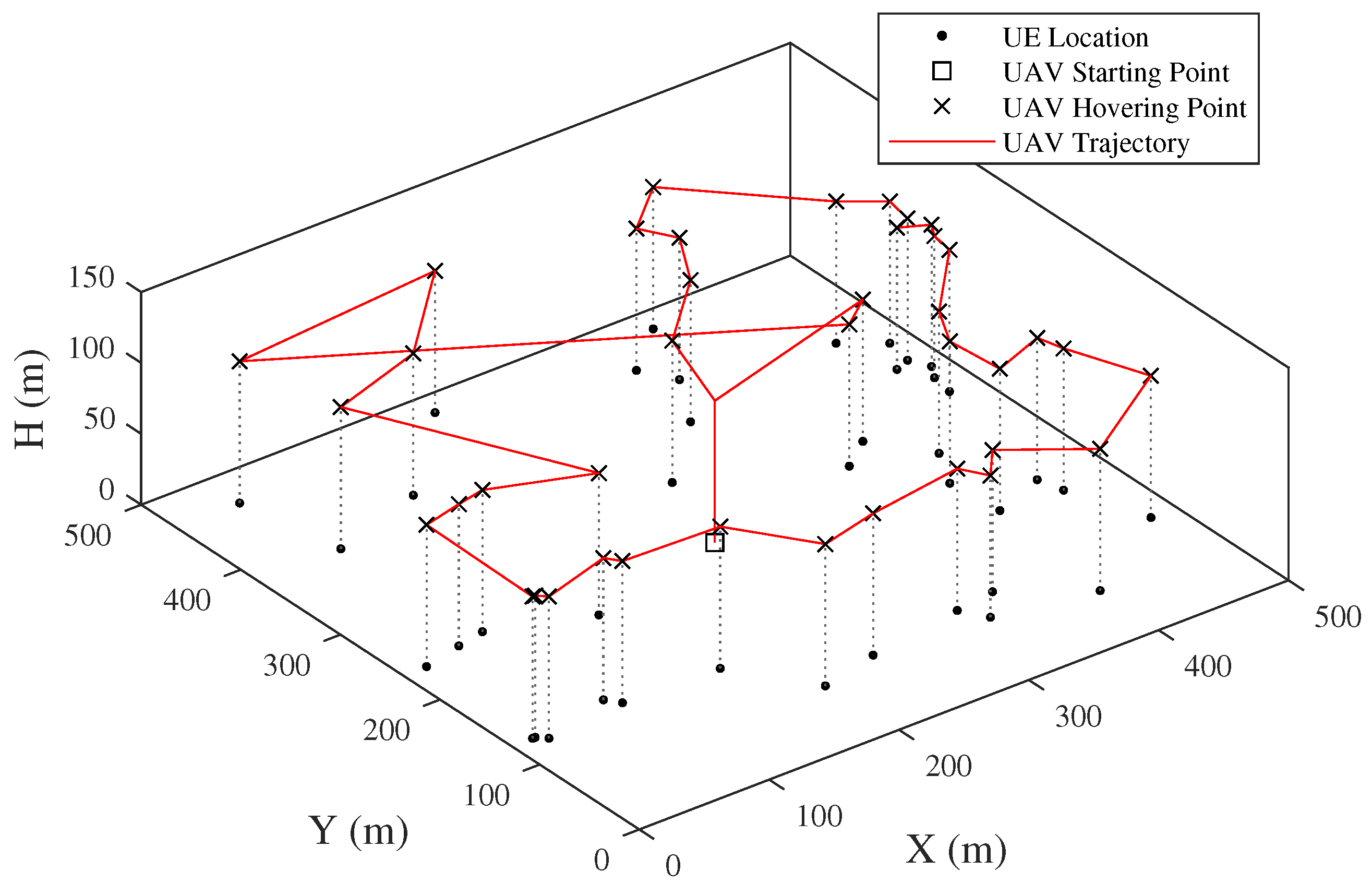

The UAV trajectories by previous method and proposed method are respectively shown in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15. In previous method, the UAV’s flight altitude is assumed as an constant, which is 100 m in

Figure 14. The UAV needs to hover above each UE for data collection. This may increase the complexity of the trajectory, especially when the number of UEs increases. In contrast, the proposed method in this article i.e. 3-dimensional trajectory finishes the data collection with fewer hovering points by optimizing the flight altitude. The UAV covers and collects data from multiple UEs at the same location each time when hovering.

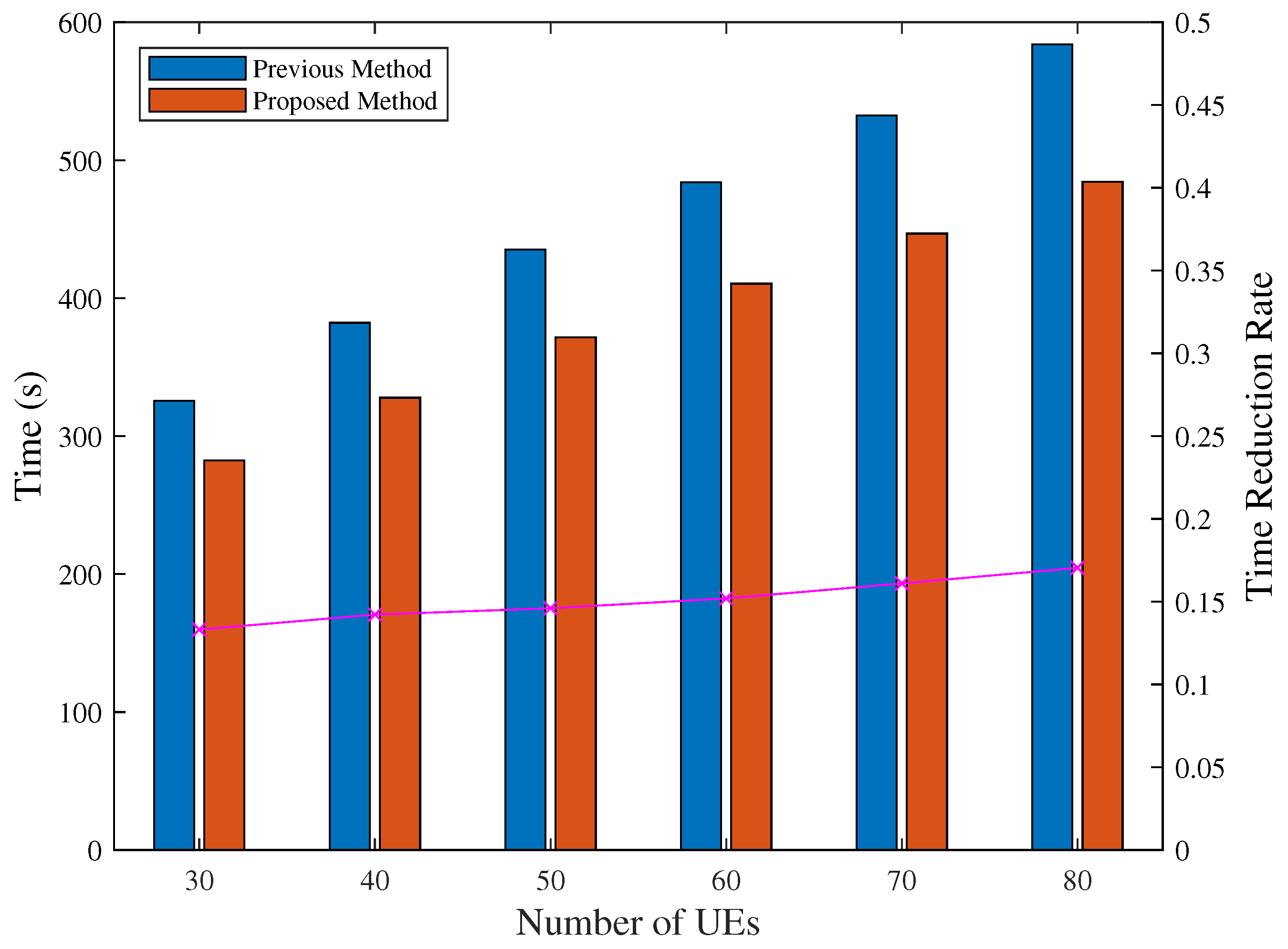

The results of the completion time with varying number of UEs are shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 16, where hovering time is the time for data transmission. From

Table 3, it is clear that flight time occupies a large proportion in the mission completion time. The completion time, especially the flight time, is reduced by the proposed method, with the reduction rate of nearly 0.2. The hovering time slightly increases because of the increasement of UAV’s flight altitude, which lowers the data rate.

6. Conclusions

In this article, we considered the feasibility of UAV-based post-disaster data collection by proposing a 3-dimensional trajectory, which optimized the UAV’s flight altitude. We transformed the problem to a LSCP solved by GA, and compared it with the traditional k-means clustering approach. From the simulation results, the proposed method showed better efficiency than the traditional k-means approach, covering all UEs with fewer number of hovering points. In addition, the effect of completion time reduction by the 3-dimensional trajectory proposed in this article is also confirmed, which indicates that the optimization of UAV’s flight altitude is effective for completion time reduction.

However, this article focused on the optimization of UAV trajectory, which mainly contributes to the reduction of flight time. Although flight time occupies a large proportion in the mission completion time, the hovering time for data collection is also needed to be considered in future studies. Additionally, in real situations, environment conditions such as obstacles like buildings, weather such as wind, rain etc. also affect the flight of UAVs. For future issues of trajectory optimization, it is necessary to adapt advanced simulation models such as wind model, building model etc., and finally demonstration experiments are needed for further discussions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z. and G.K.T.; methodology, R.Z.; software, R.Z.; validation, R.Z.; formal analysis, R.Z.; investigation, R.Z.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.K.T.; visualization, R.Z.; supervision, G.K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable..

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Communication Situation in the Great East Japan Earthquake (in Japanese). Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/whitepaper/ja/h23/pdf/n0010000.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- National Institute of Information and Communications Technology. Disaster-Resilient Communication Networks: Introduction Guidelines (in Japanese). Available online: https://www.nict.go.jp/resil/pdf/guideline202006.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Yamamoto Town. Damage from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami (in Japanese). Available online: https://www.town.yamamoto.miyagi.jp/site/fukkou/324.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- El Debeiki, M.; Al-Rubaye, S.; Perrusquía, A.; Conrad, C.; Flores-Campos, J.A. An Advanced Path Planning and UAV Relay System: Enhancing Connectivity in Rural Environments. Future Internet 2024, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wei, X.; Jia, Y.; Chen, M. UAV relay network deployment through the area with barriers. Ad Hoc Networks 2023, 149, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, I.; Vipin, K. Multi-UAV networks for disaster monitoring: Challenges and opportunities from a network perspective. Drone Systems and Applications 2024, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Kuang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Hou, F. Task Offloading and Trajectory Optimization for Secure Communications in Dynamic User Multi-UAV MEC Systems. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2024, 23, 14427–14440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrallah, A.; Mohamed, E.M.; Tran, G.K.; Sakaguchi, K. UAV Trajectory Optimization in a Post-Disaster Area Using Dual Energy-Aware Bandits. Sensors 2023, 23, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Lei, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, C.; Nallanathan, A. Trajectory Optimization for UAV Emergency Communication With Limited User Equipment Energy: A Safe-DQN Approach. IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking 2021, 5, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, H. Completion Time Minimization Considering GNs’ Energy for UAV-Assisted Data Collection. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2023, 12, 2128–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, H.; Gu, F.; Wei, J.; Yin, H.; Ren, B. Joint Optimization on Trajectory, Altitude, Velocity, and Link Scheduling for Minimum Mission Time in UAV-Aided Data Collection. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hourani, A.; Kandeepan, S.; Lardner, S. Optimal LAP Altitude for Maximum Coverage. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2014, 3, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Redhu, S.; Hegde, R.M. UAV Altitude Optimization for Efficient Energy Harvesting in IoT Networks. 2022 National Conference on Communications (NCC), Mumbai, India, 2022; pp. 350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Duo, B.; Yuan, X.; Renzo, M.D. Energy-Efficient UAV Communications in the Presence of Wind: 3D Modeling and Trajectory Design. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2024, 23, 1840–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzenad, M.; El-Keyi, A.; Yanikomeroglu, H. 3-D Placement of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Base Station for Maximum Coverage of Users With Different QoS Requirements. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2018, 7, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. The Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozasa, M.; Tran, G.K.; Sakaguchi, K. Research on the Placement Method of UAV Base Stations for Dynamic Users. 2021 IEEE VTS 17th Asia Pacific Wireless Communications Symposium (APWCS), Osaka, Japan, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Toregas, C.; Swain, R.; ReVelle, C.; Bergman, L. The Location of Emergency Service Facilities. Operations Research 1971, 19, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelman, L.J.; David Schaffer, J. Real-Coded Genetic Algorithms and Interval-Schemata. Foundations of Genetic Algorithms 1993, 2, 187–202. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).