Submitted:

14 February 2023

Posted:

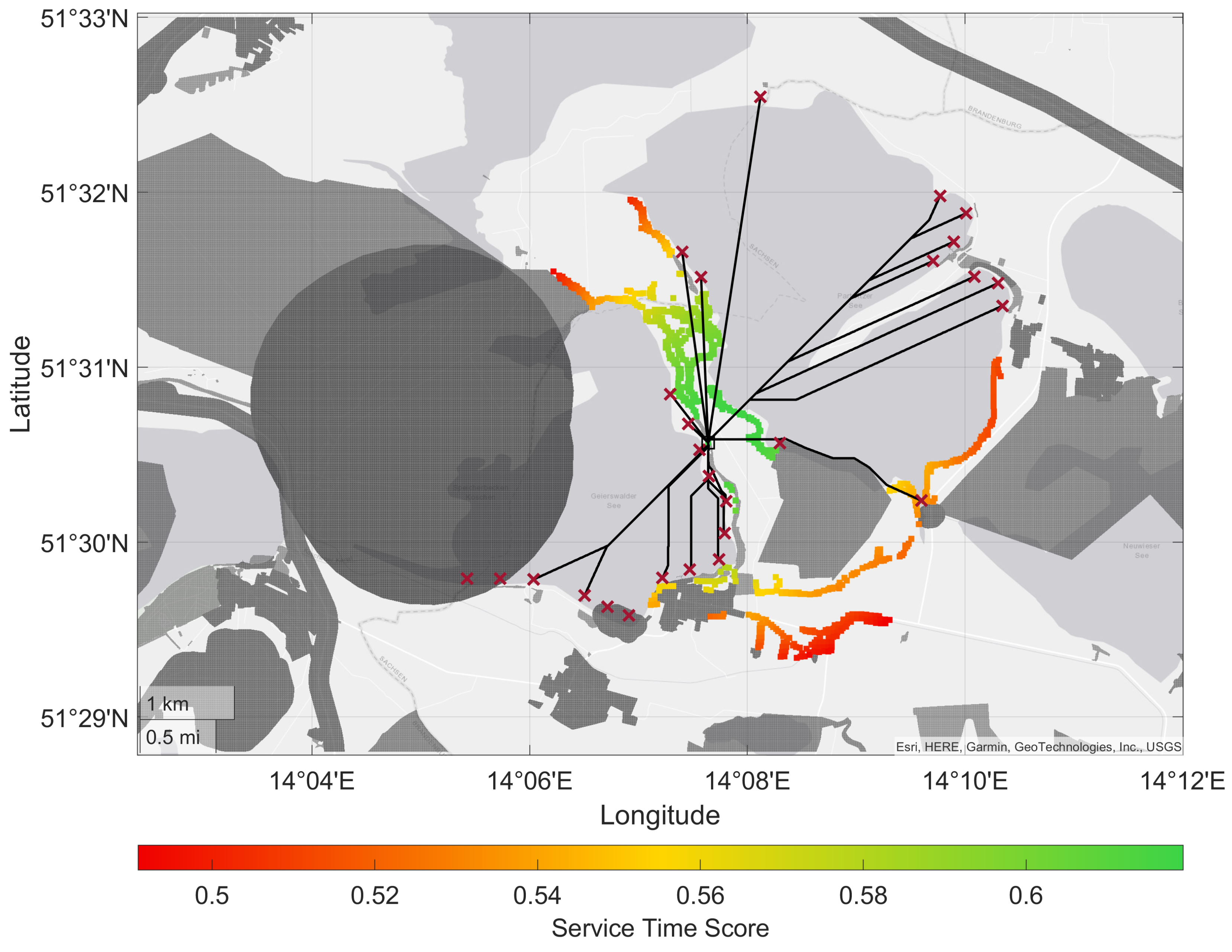

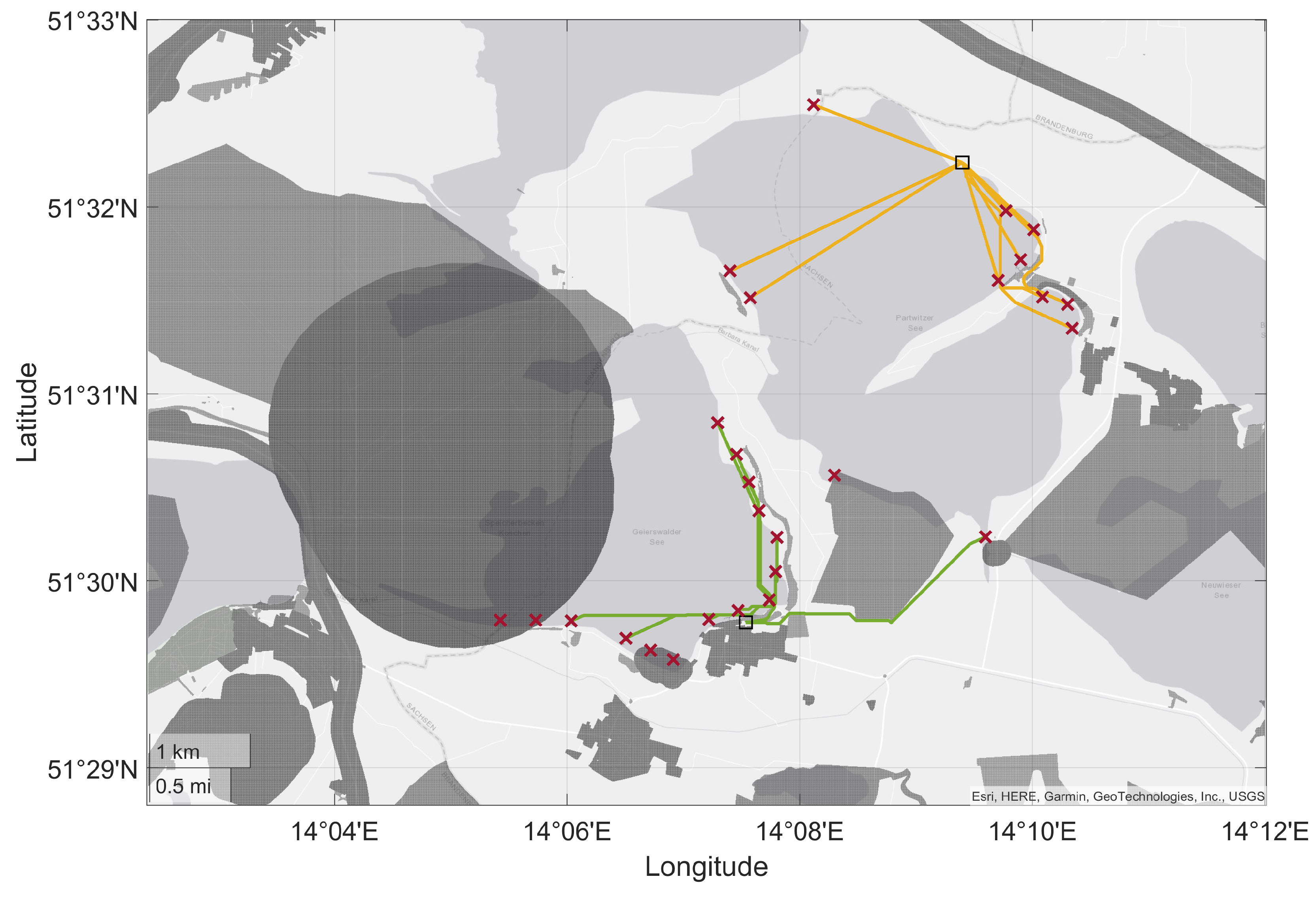

17 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. SAR Concepts with UAS

1.2. UAV Flight Path Planning for SAR

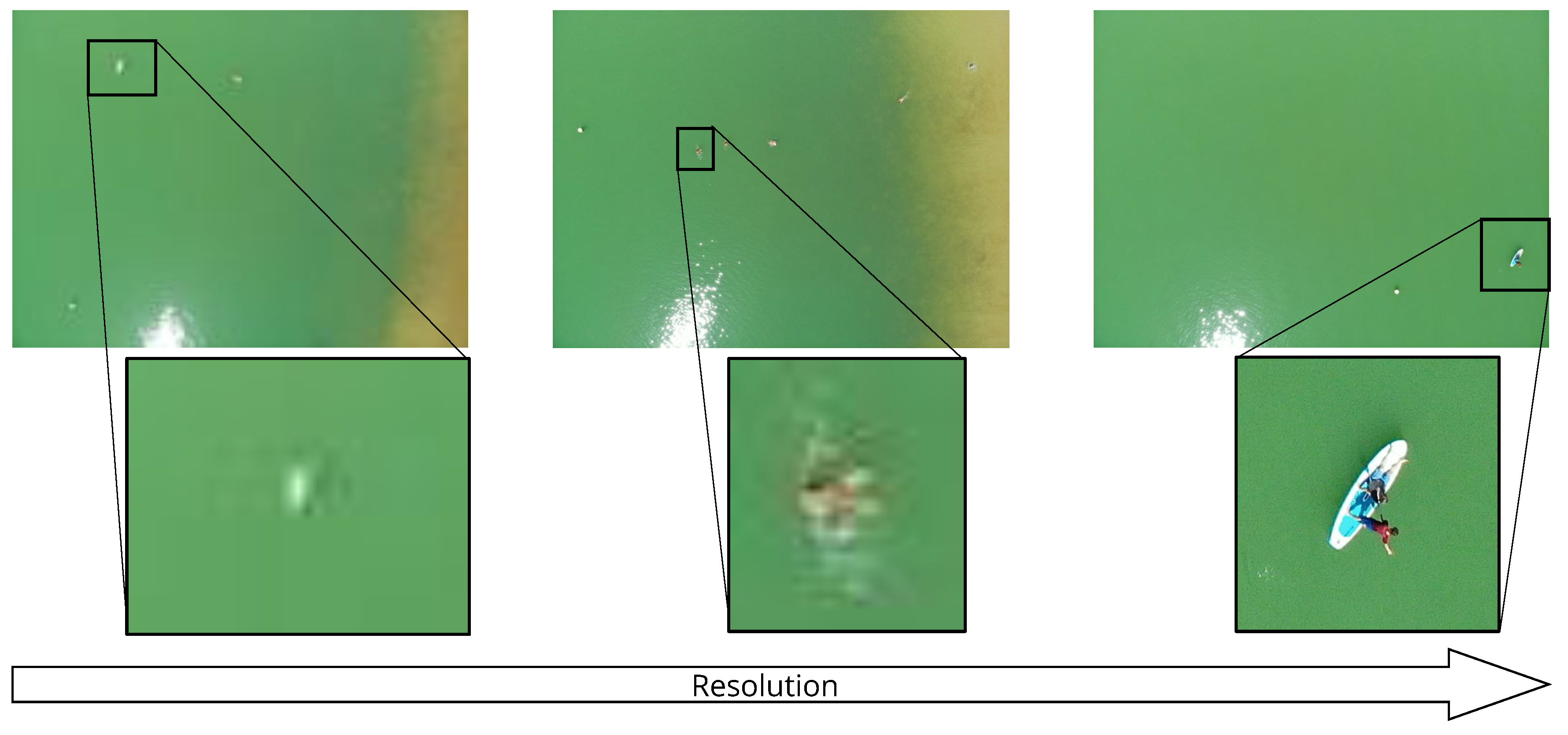

1.3. Automated Detection of a Person in Distress

1.4. Facility Location Problem

2. Materials and Methods

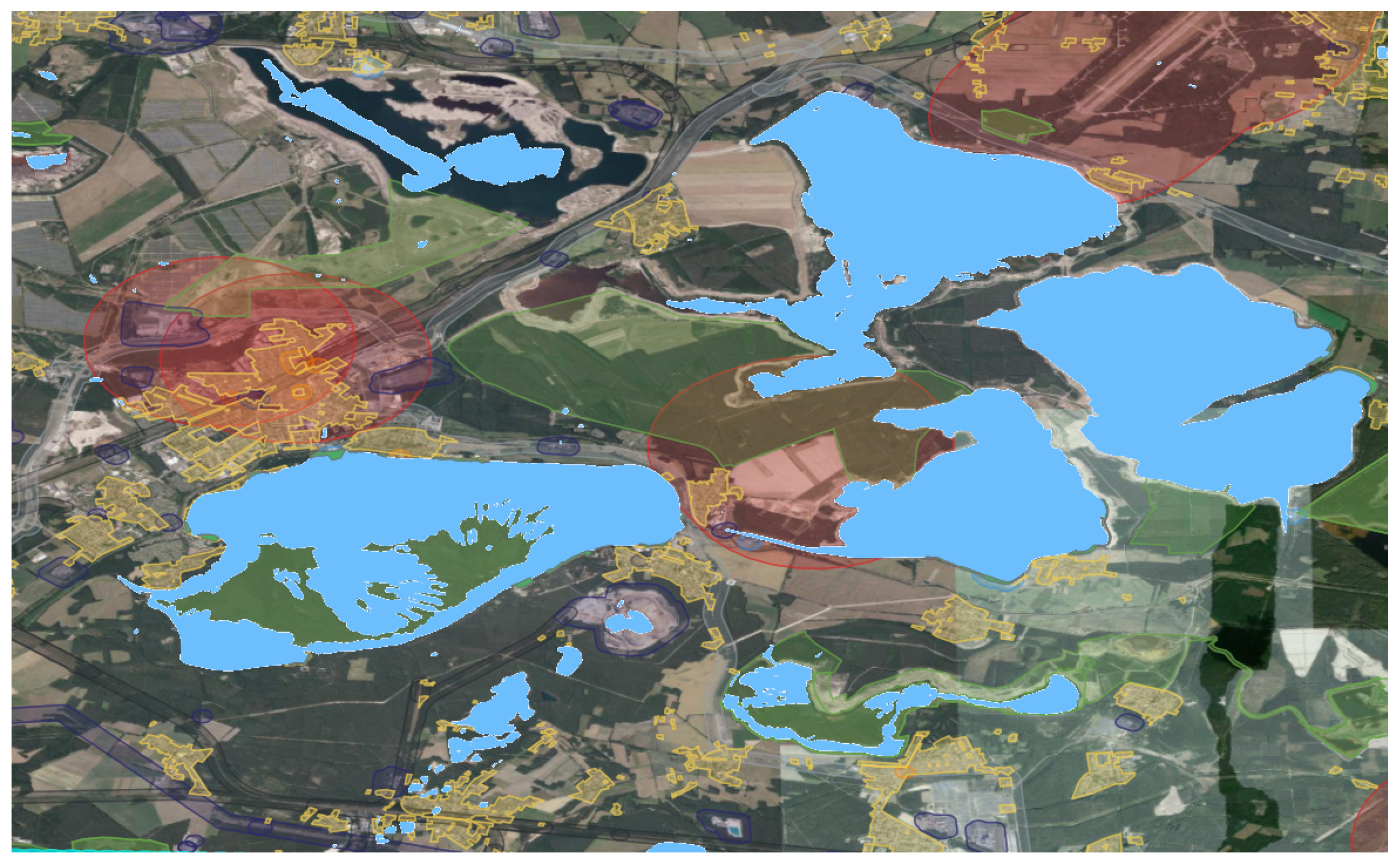

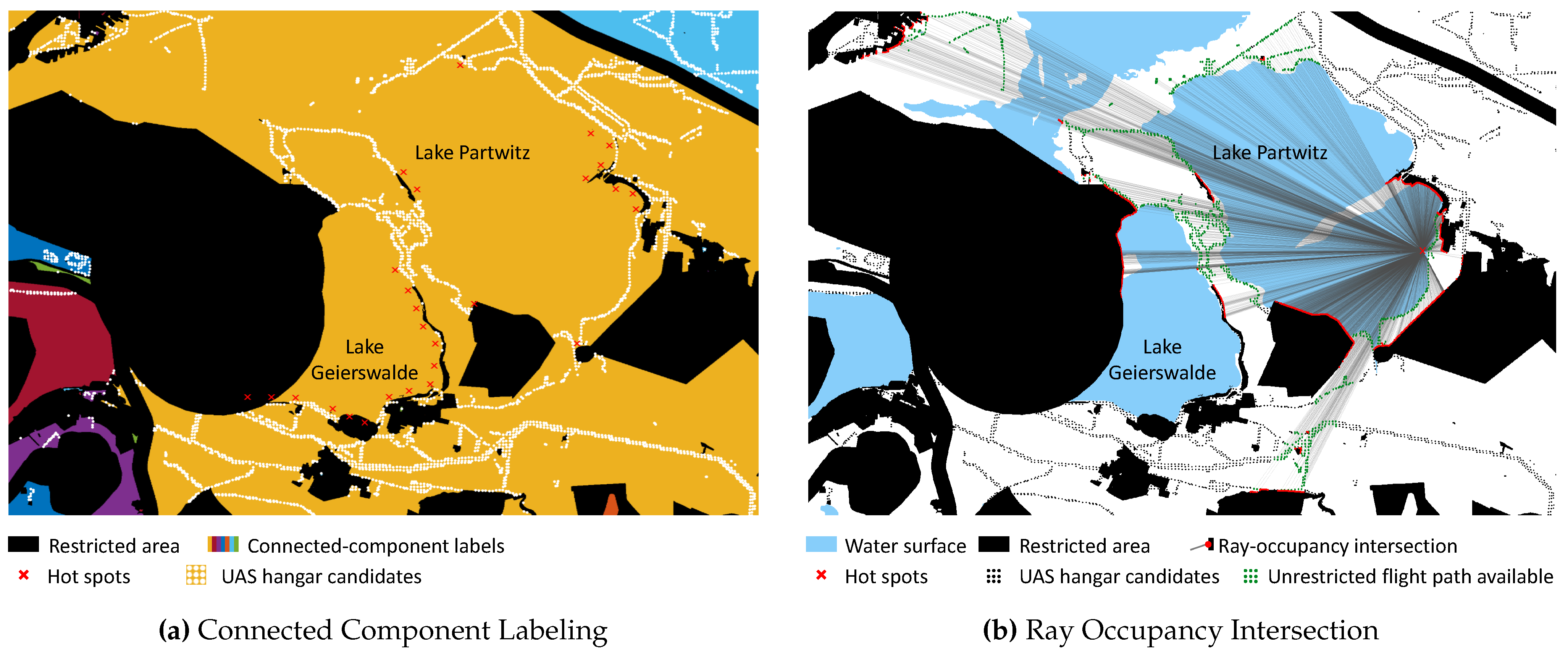

2.1. Overview of the Approach

- Restriction-free flight from the hangar to the hotspot by invoking the special rights of authorities conducting SAR missions according to § 21k LuftVO [35];

- Compliance with specified air and ground risk relevant UAS geographical zones;

- Compliance with all specified UAS geographical zones; and

- Compliance with all specified UAS geographical zones and avoidance of potentially crowded areas.

2.2. Acquisition of Open Source Data

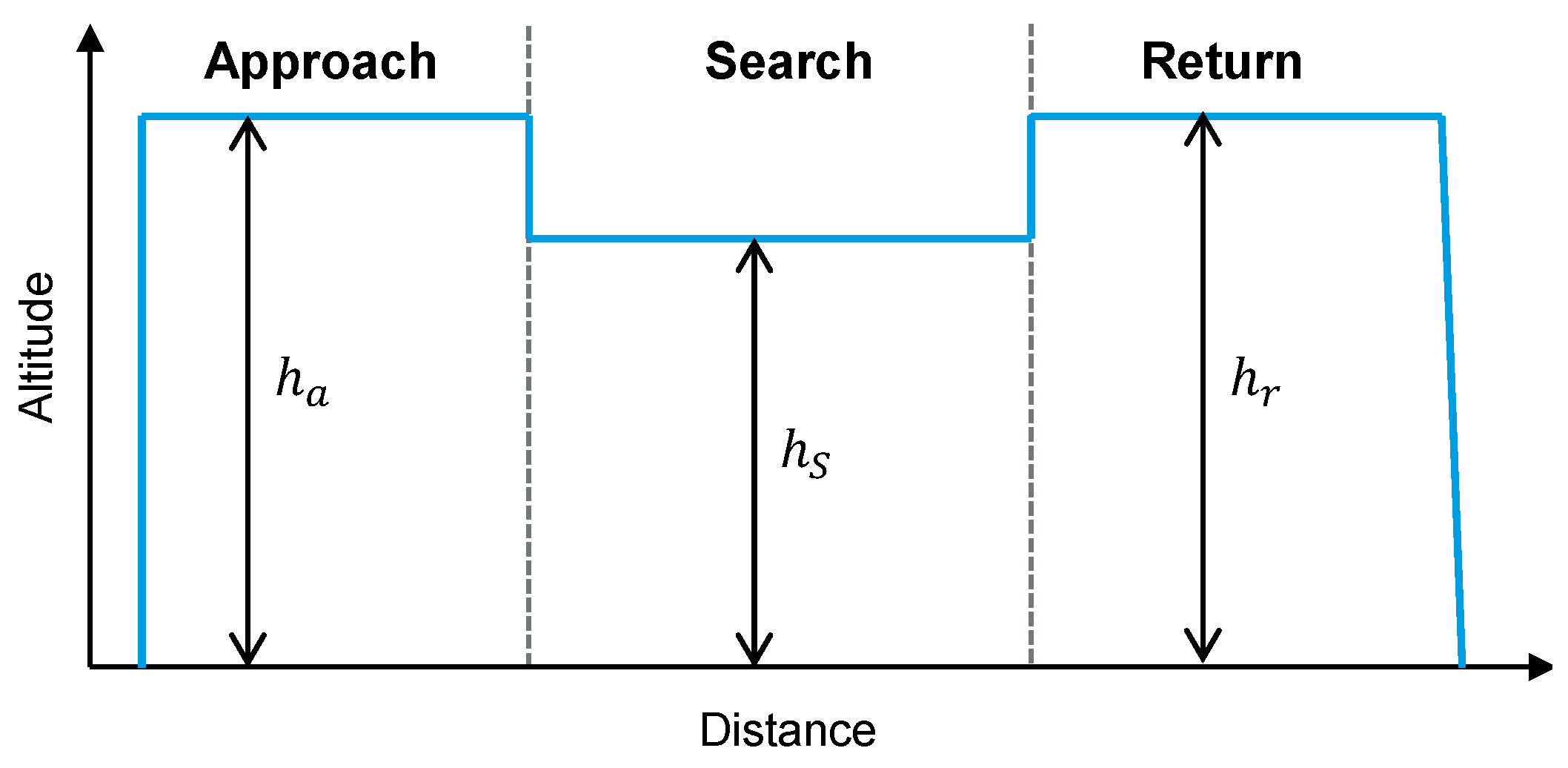

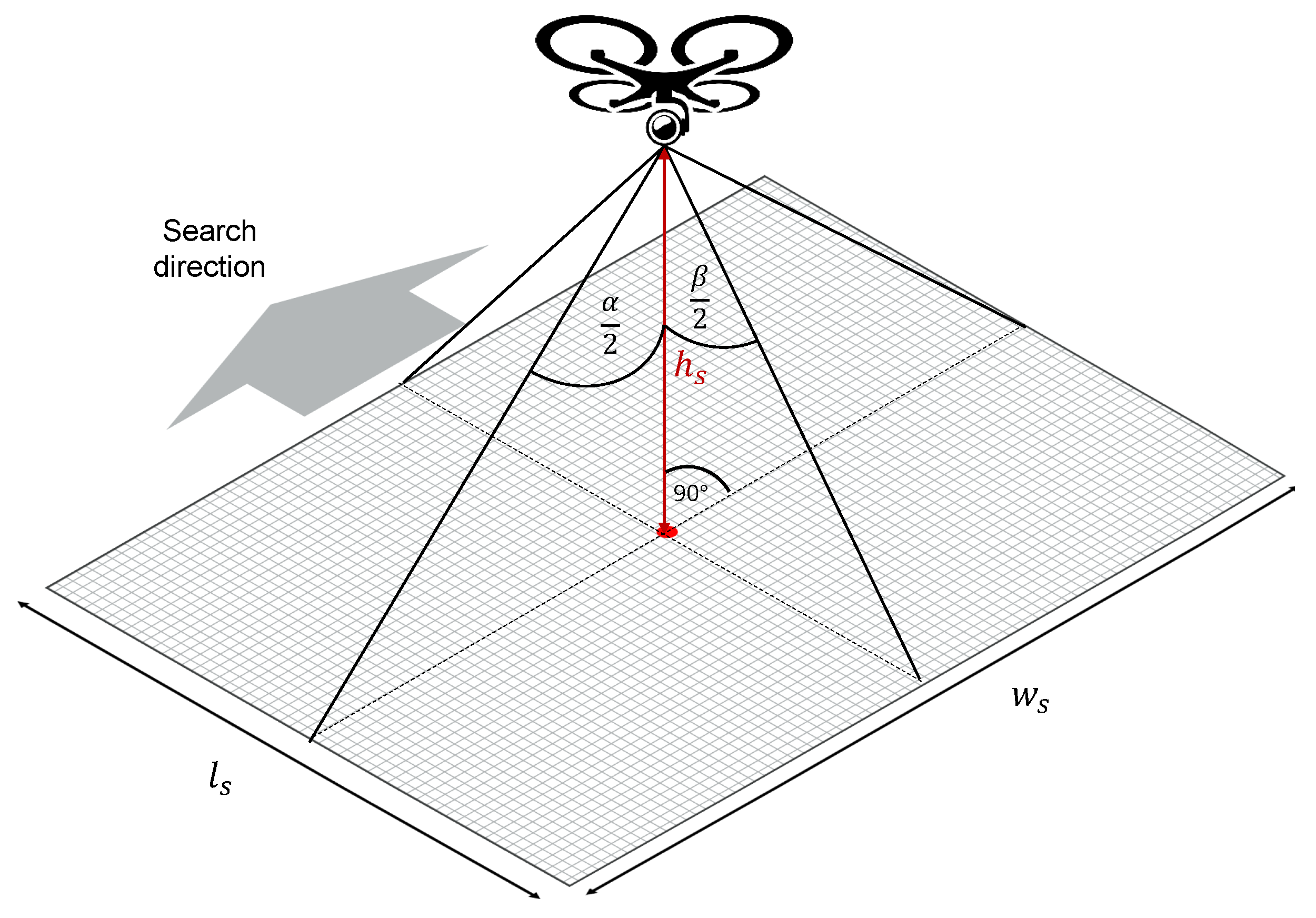

2.3. Definition of the Standard SAR Mission

2.4. Optimization Model for UAV Hangar Positions

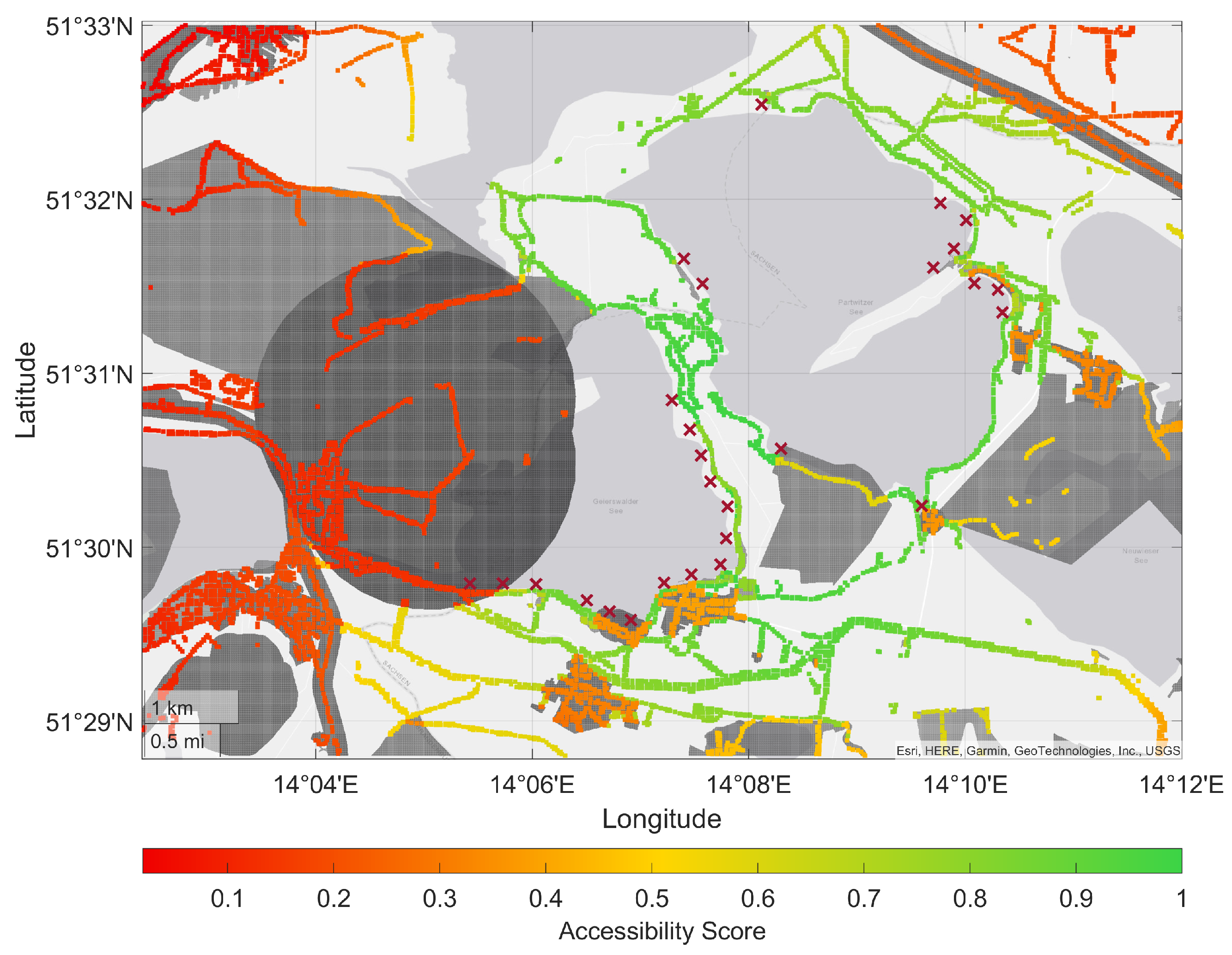

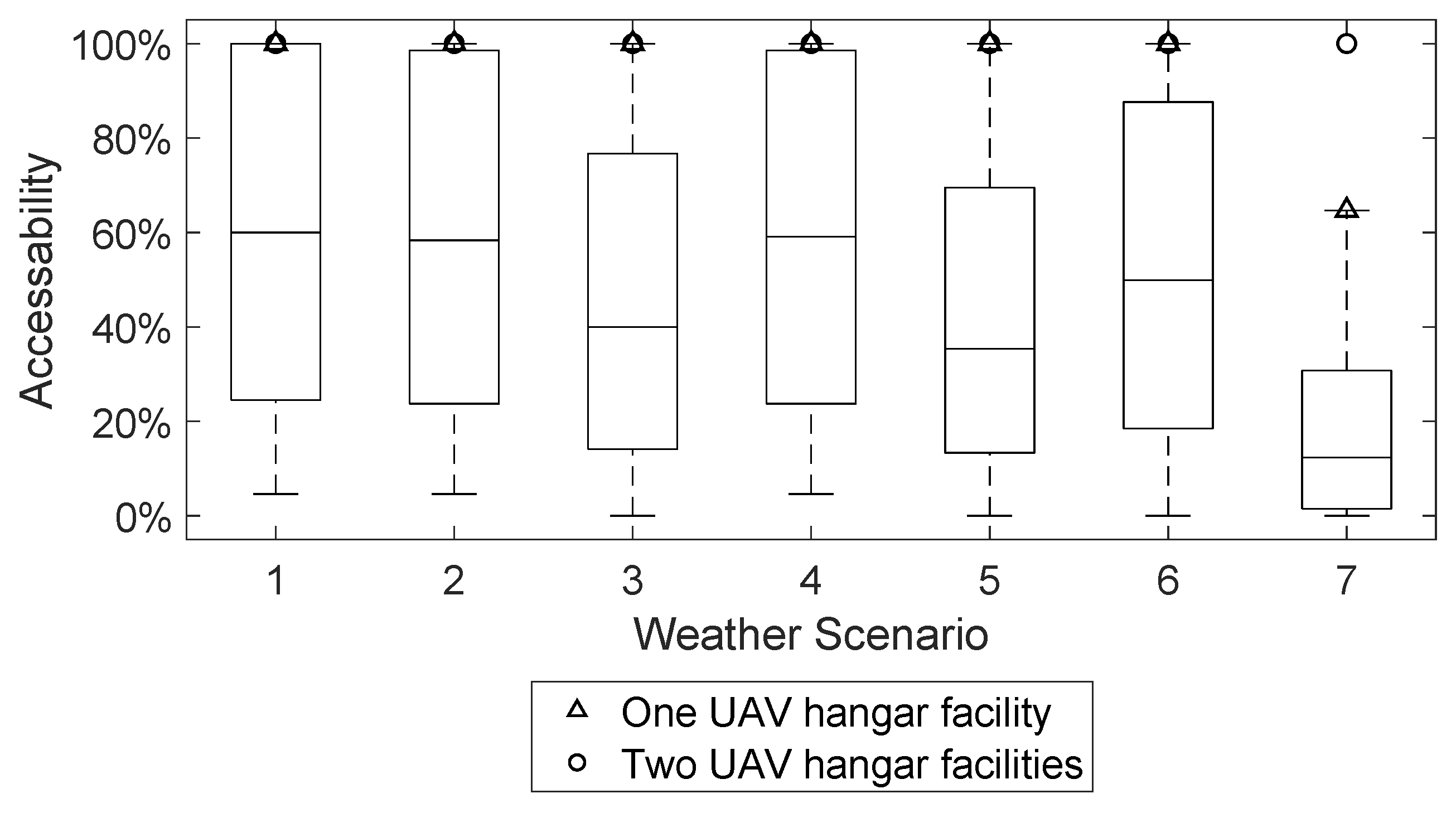

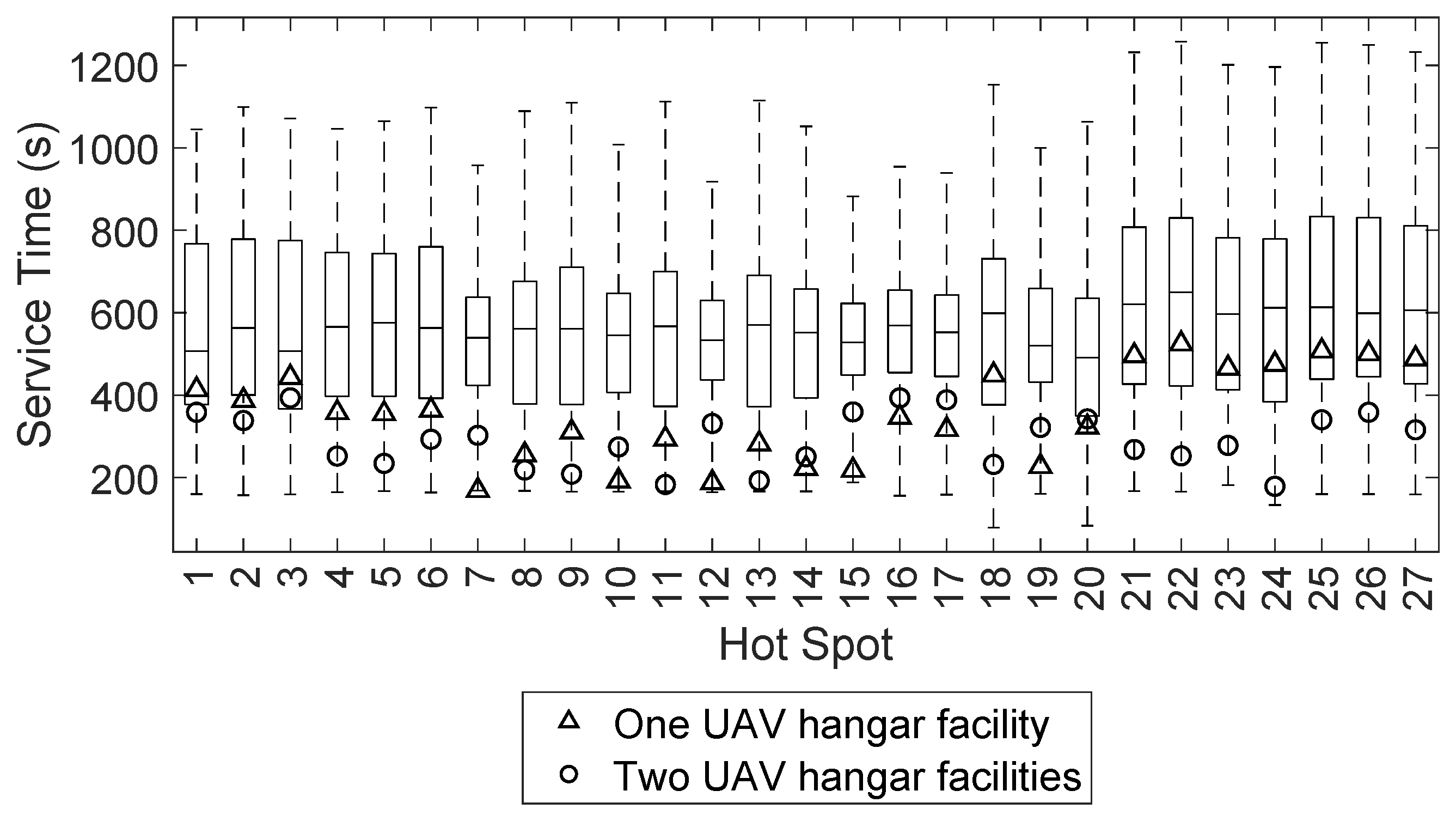

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Validation of the Hotspots Obtained from Open Source Data

4.2. Analysis of the Applicability of the Hangar Locations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | German Federal Regulation for aircraft operations, which supplements EU 2019/947. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 |

References

- World Health Organization. Drowning. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning, 2021.

- Jahresbericht 2021. Technical report, Deutsche Lebens-Rettungs-Gesellschaft e.V. (DLRG), Bad Nenndorf, 2021.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947 of 24 May 2019 on the Rules and Procedures for the Operation of Unmanned Aircraft, 2019.

- Esri. "World Imagery" [Basemap]. Scale Not Given. https://www.arcgis.com/apps/mapviewer/index.html?layers=10df2279f9684e4a9f6a7f08febac2a9, Janary 19, 2023.

- Land Brandenburg. Geoportal Brandenburg: Start. https://geoportal.brandenburg.de/de/cms/portal/start, 2023.

- Bundesministerium für Digitales und Verkehr. Digital Platform for Unmanned Aviation (Dipul). https://maptool-dipul.dfs.de/, 2023.

- Ajgaonkar, K.; Khanolkar, S.; Rodrigues, J.; Shilker, E.; Borkar, P.; Braz, E. Development of a Lifeguard Assist Drone for Coastal Search and Rescue. In Proceedings of the Global Oceans 2020: Singapore – U.S. Gulf Coast, 2020, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Seguin, C.; Blaquière, G.; Loundou, A.; Michelet, P.; Markarian, T. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (Drones) to Prevent Drowning. Resuscitation 2018, 127, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufek, J.; Murphy, R. Visual Pose Estimation of USV from UAV to Assist Drowning Victims Recovery. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), 2016, pp. 147–153. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Wen, Y.; Xiao, C.; Chen, Y.; Sui, Z. Mode Design and Experiment of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Search and Rescue in Inland Waters *. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), 2021, pp. 917–922. [CrossRef]

- Ruetten, L.; Regis, P.A.; Feil-Seifer, D.; Sengupta, S. Area-Optimized UAV Swarm Network for Search and Rescue Operations. In Proceedings of the 2020 10th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), 2020, pp. 0613–0618. [CrossRef]

- Brühl, R.; Fricke, H.; Schultz, M. Air Taxi Flight Performance Modeling and Application. In Proceedings of the USA/Europe ATM R&D Seminar, 2021.

- Chu, T.; Starek, M.J.; Berryhill, J.; Quiroga, C.; Pashaei, M. Simulation and Characterization of Wind Impacts on sUAS Flight Performance for Crash Scene Reconstruction. Drones 2021, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Goodrich, M.A. UAV Intelligent Path Planning for Wilderness Search and Rescue. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2009, pp. 709–714. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Yanmaz, E.; Brown, T.X.; Bettstetter, C. Multi-Objective UAV Path Planning for Search and Rescue. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2017, pp. 5569–5574. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, P.; Zhang, T.; Sun, J. The Adaptive Vortex Search Algorithm of Optimal Path Planning for Forest Fire Rescue UAV. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 3rd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), 2018, pp. 400–403. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Han, Z. Research on Maritime Rescue UAV Based on Beidou CNSS and Extended Square Search Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Communications, Information System and Computer Engineering (CISCE), 2020, pp. 102–106. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, W.; Liang, W.; Peng, J.; Jia, X.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, L. Nonredundant Information Collection in Rescue Applications via an Energy-Constrained UAV. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019, 6, 2945–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakulović, M.; Horvatić, S.; Petrović, I. Complete Coverage D* Algorithm for Path Planning of a Floor-Cleaning Mobile Robot. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2011, 44, 5950–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.F.; Ding, Y.X.; Luo, J.C. Complete Coverage Path Planning of an Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on a Complete Coverage Neural Network Algorithm. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tan, Q.; Yan, C.; Chang, Y.; Xiang, X.; Zhou, H. Multi-UAV Coverage through Two-Step Auction in Dynamic Environments. Drones 2022, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingqing, L.; Taipalmaa, J.; Queralta, J.P.; Gia, T.N.; Gabbouj, M.; Tenhunen, H.; Raitoharju, J.; Westerlund, T. Towards Active Vision with UAVs in Marine Search and Rescue: Analyzing Human Detection at Variable Altitudes. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), 2020, pp. 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Rudol, P.; Doherty, P. Human Body Detection and Geolocalization for UAV Search and Rescue Missions Using Color and Thermal Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Aerospace Conference, 2008, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Bejiga, M.B.; Zeggada, A.; Nouffidj, A.; Melgani, F. A Convolutional Neural Network Approach for Assisting Avalanche Search and Rescue Operations with UAV Imagery. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygouras, E.; Santavas, N.; Taitzoglou, A.; Tarchanidis, K.; Mitropoulos, A.; Gasteratos, A. Unsupervised Human Detection with an Embedded Vision System on a Fully Autonomous UAV for Search and Rescue Operations. Sensors 2019, 19, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feraru, V.A.; Andersen, R.E.; Boukas, E. Towards an Autonomous UAV-based System to Assist Search and Rescue Operations in Man Overboard Incidents. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), 2020, pp. 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Szirányi, T. Real-Time Human Detection and Gesture Recognition for On-Board UAV Rescue. Sensors 2021, 21, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Han, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, G.; Du, N. A Deep-Learning-Based Sea Search and Rescue Algorithm by UAV Remote Sensing. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE CSAA Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference (CGNCC), 2018, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Cornuejols, G.; Nemhauser, G.; Wolsey, L. The uncapacitated, facility location problem. Discrete Location Theory 1990, p. 119–171.

- Shmoys, D. Approximation algorithms for facility location problems. Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Approximation Algorithms for Combinatorial Optimization 2000, p. 27–33.

- Arya, V.; Garg, N.; Khandekar, R.; Meyerson, A.; Munagala, K.; Pandit, V. Local Search Heuristic for K-Median and Facility Location Problems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-Third Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2001; STOC ’01, pp. 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, S.; Swamy, C. Improved Approximation Guarantees for Lower-Bounded Facility Location. CoRR 2011, abs/1104.3128, [1104.3128]. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Boyles, S.D.; Unnikrishnan, A. Two-stage robust facility location problem with drones. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2022, 137, 103563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynskey, J.; Thar, K.; Oo, T.; Hong, C.S. Facility Location Problem Approach for Distributed Drones. Symmetry 2019, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luftverkehrs-Ordnung Vom 29. Oktober 2015 (BGBl. I S. 1894), zuletzt geändert durch Artikel 2 Des Gesetzes Vom 14. Juni 2021 (BGBl. I S. 1766).

- Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2018 on Common Rules in the Field of Civil Aviation and Establishing a European Union Aviation Safety Agency [...], 2018.

- van Dyck, L.E.; Kwitt, R.; Denzler, S.J.; Gruber, W.R. Comparing Object Recognition in Humans and Deep Convolutional Neural Networks—An Eye Tracking Study. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesetz über den Rettungsdienst im Land Brandenburg (Brandenburgisches Rettungsdienstgesetz - BbgRettG) vom 14. Juli 2008.

| Key | Values |

|---|---|

| landuse | grass, greenfield |

| natural | grassland, heath, srub, scree |

| Key | Value(s) |

|---|---|

| boundary | forest, forest_compartment, hazard |

| landuse | forest |

| natural | tree, tree_row, wood, wetland |

| Key | Values |

|---|---|

| highway | motorway, trunk, primary, secondary, tertiary, unclassified, residential, motorway_link, trunk_link, primary_link, secondary_link, living_street, service, pedestrian, track, bus_guideway, escape, raceway, road, busway, cycleway |

| tracktype | grade1, grade2, grade3 |

| Key | Value(s) |

|---|---|

| amenity | boat_rental, boat_sharing, ferry_terminal, public_bath, parking, parking_space, lounger |

| building | beach_hut |

| emergency | lifeguard, life_ring, phone |

| landuse | grass |

| leisure | marina, slipway, swimming_area, swimming_pool, water_park, beach_resort, park, picnic_table |

| lifeguard | tower |

| man_made | pier |

| natural | beach, shingle, shoal, sand |

| sport | sailing, swimming, surfing, wakeboarding, water_polo, water_ski |

| tourism | camp_site, caravan_site |

| Wind Scenario | Windspeed | Turbulence Index | Detour Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| [] | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 0 | 1.023 |

| 3 | 10.5 | 0 | 1.237 |

| 4 | 3.5 | 10 | 1.018 |

| 5 | 10.5 | 10 | 1.311 |

| 6 | 3.5 | 20 | 1.109 |

| 7 | 10.5 | 20 | 2.199 |

| Geographical Zone | Wind Scenarios | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 17 |

| 2 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 17 |

| 3 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 15 |

| 4 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 14 |

| 5 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).