Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

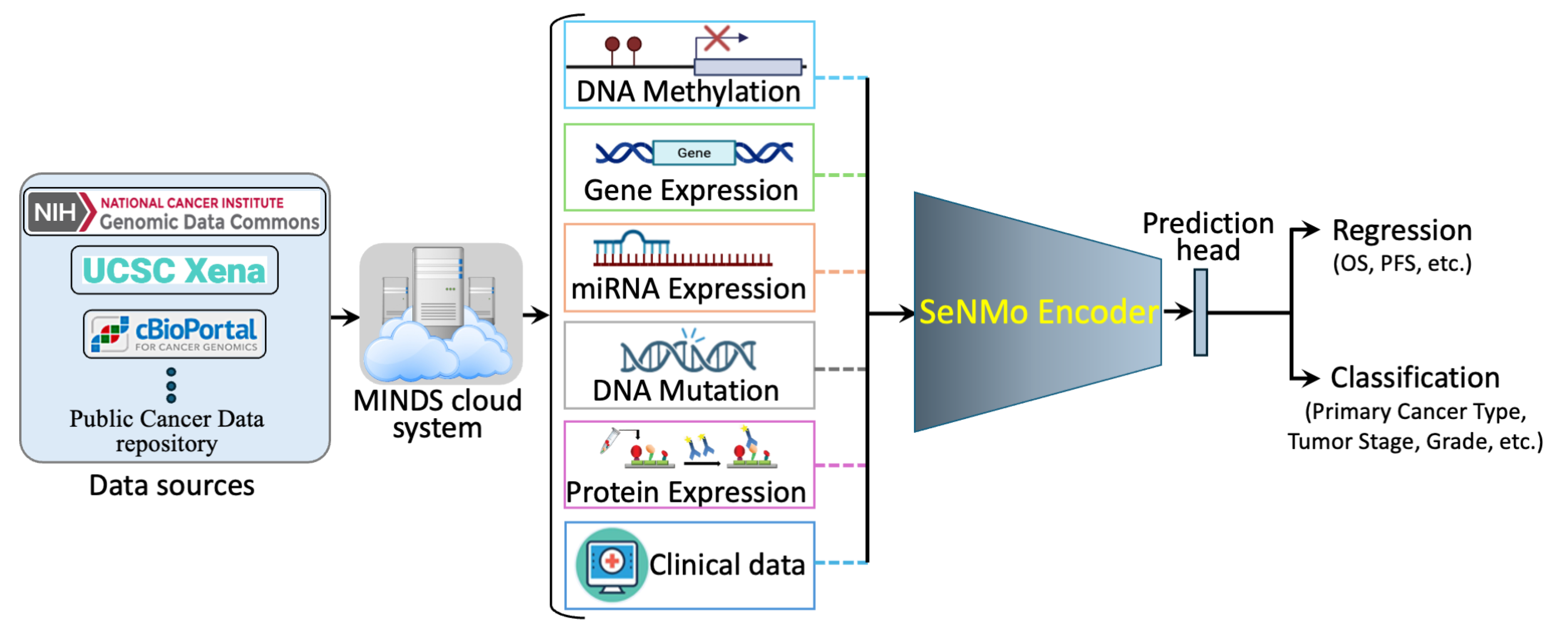

- The SeNMo framework represents the first initiative to analyze 33 cancer types using five molecular data modalities: gene expression, miRNA expression, DNA methylation, DNA mutations, and protein expression, along with the clinical data.

- We created a multi-omics, pan-cancer framework with minimal and essential preprocessing steps, eliminating the need for complex, custom-engineered methods, thereby allowing a greater focus on the learning aspect.

- We developed a deep learning model capable of generalizing across different tasks and to unseen data through fine-tuning.

- Our findings indicate that MLP-based networks are highly susceptible to catastrophic forgetting. We demonstrate that fine-tuning should involve a fraction of the epochs (), while adjusting the learning rate, weight decay, and dropout to fractionally update all layers of the trained model.

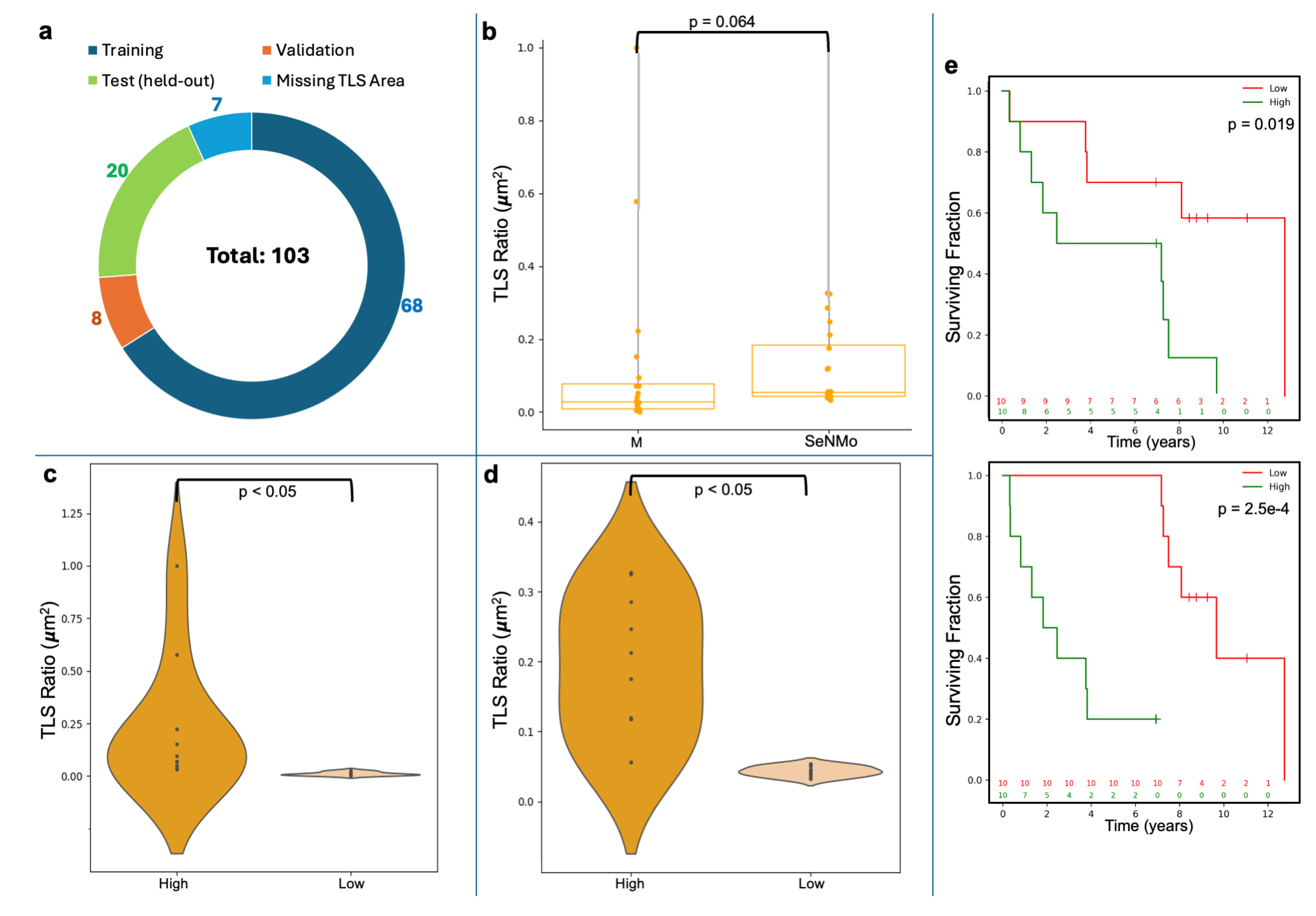

- We present the first effort to predict tertiary lymph structures (TLS) ratio from multi-omic data only.

- We provide the latent feature vectors (embeddings) learned by SeNMo as an open-access vector database system, HoneyBee, available through Hugging Face and GitHub, and separately through Zenodo.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Acquisition

3.2. Data Modalities

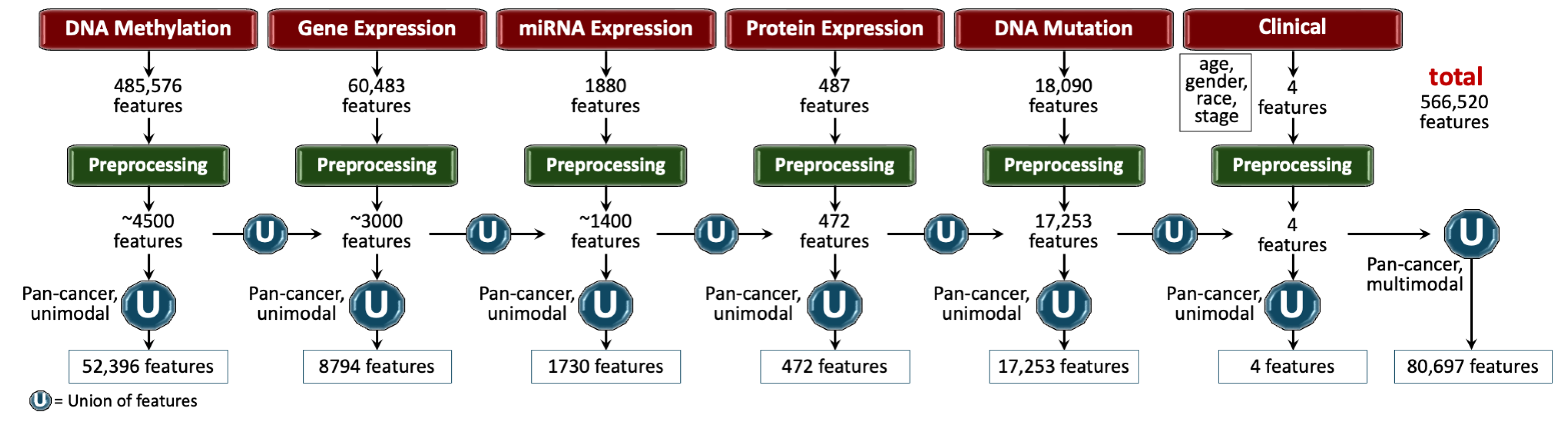

3.3. Pre-Processing

- Remove NaNs. First, we removed the features that had NaNs across all the samples. This reduced the dimension, removed noise, and ensured continuous-numbered features to work with.

- Drop constant features. Next, constant/quasi-constant features with a threshold of 0.998 were filtered out using Feature-engine, a Python library for feature engineering and selection [47]. This eliminated features with no expression at all across every sample along with features that were noise, since the expression value was the same across every sample.

- Remove duplicates features. Next, duplicate features between genes were identified that contained the same values across two seperate genes, and one of the genes was kept. This may reveal gene-gene relationships between the two genes stemming from an up-regulation pathway or could simply reflect noise.

- Remove colinear features. Next, we filtered the features having low variance (≈0.25) because the features having high variance hold the maximum amount of information [48]. We used VarianceThreshold feature selector of scikit learn library that removes low-variance features based on the defined threshold [49]. We chose a threshold for each data modality so that the resulting features have matching dimensions, as shown in Figure 2.

- Remove low-expression genes. The gene expression data originally contained 60,483 features, with FPKM transformed numbers ranging from 0 to 12. Roughly 30,000 features remained after the above-mentioned preprocessing steps, which was still a very high number of features. High expression values reveal important biological insights due to an indication that a certain gene product is transcribed in large quantities, revealing their relevance. Features containing an expression value greater than 7 (127 FPKM value) were kept, while the rest were discarded.

- Handle missing features. We handled missing features at two levels of data integration. First, for the features within each modality and cancer type, the missing values were imputed with the mean of the samples for that feature. This resulted in the full-length feature vector for each sample. Second, across different cancers and modalities, we padded the missing features with zeros. In deep learning, the zero imputation technique shows the best performance compared to other imputation techniques and deficient data removal techniques [50,51,52].

3.3.1. Features Integration

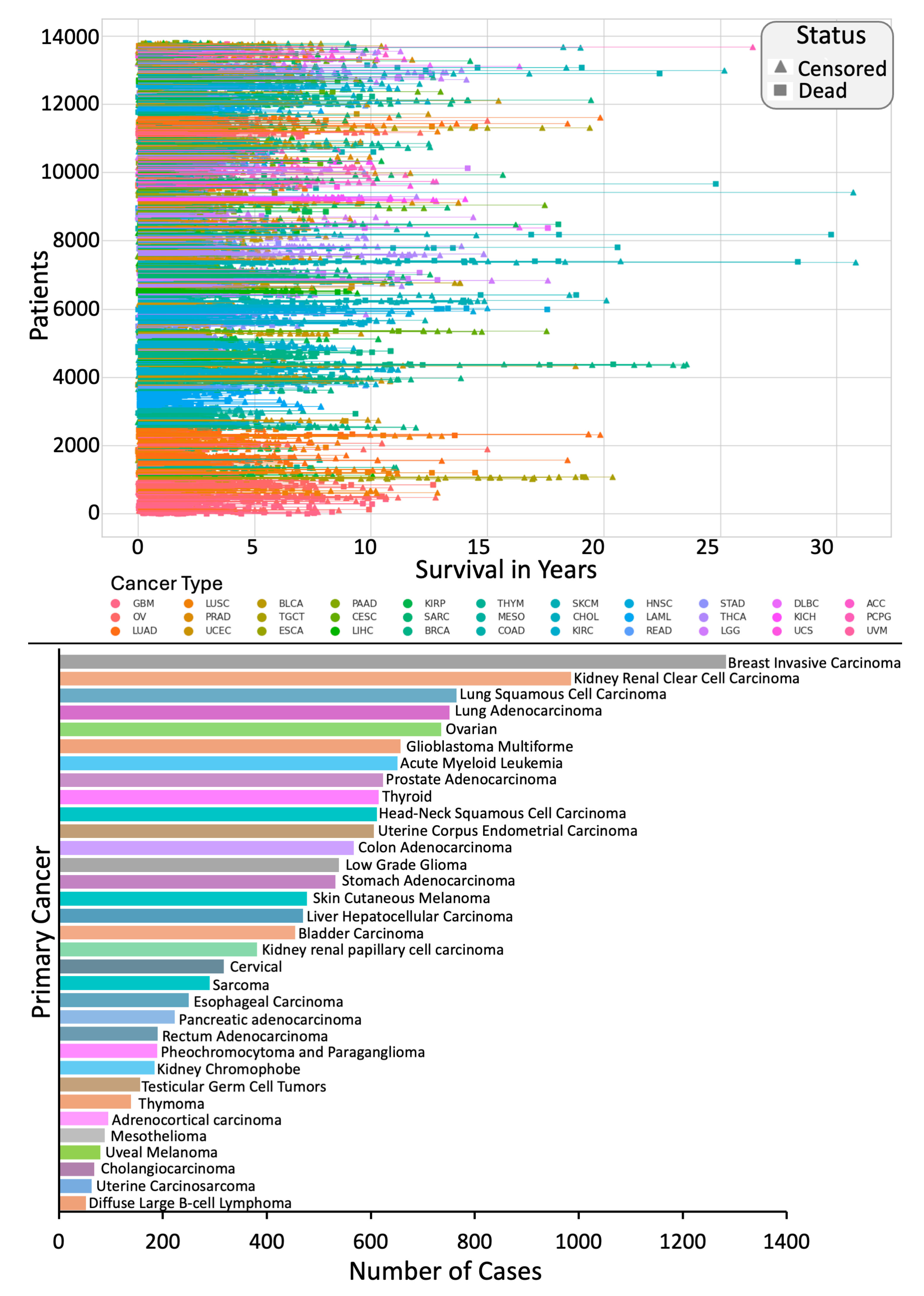

3.4. Clinical End-Points

3.4.1. Overall Survival (OS)

3.4.2. Primary Cancer Type

3.4.3. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures (TLS) Ratio

3.5. SeNMo Deep Learning Model

3.6. Training and Evaluation

3.6.1. Data Splits

3.6.2. Evaluation

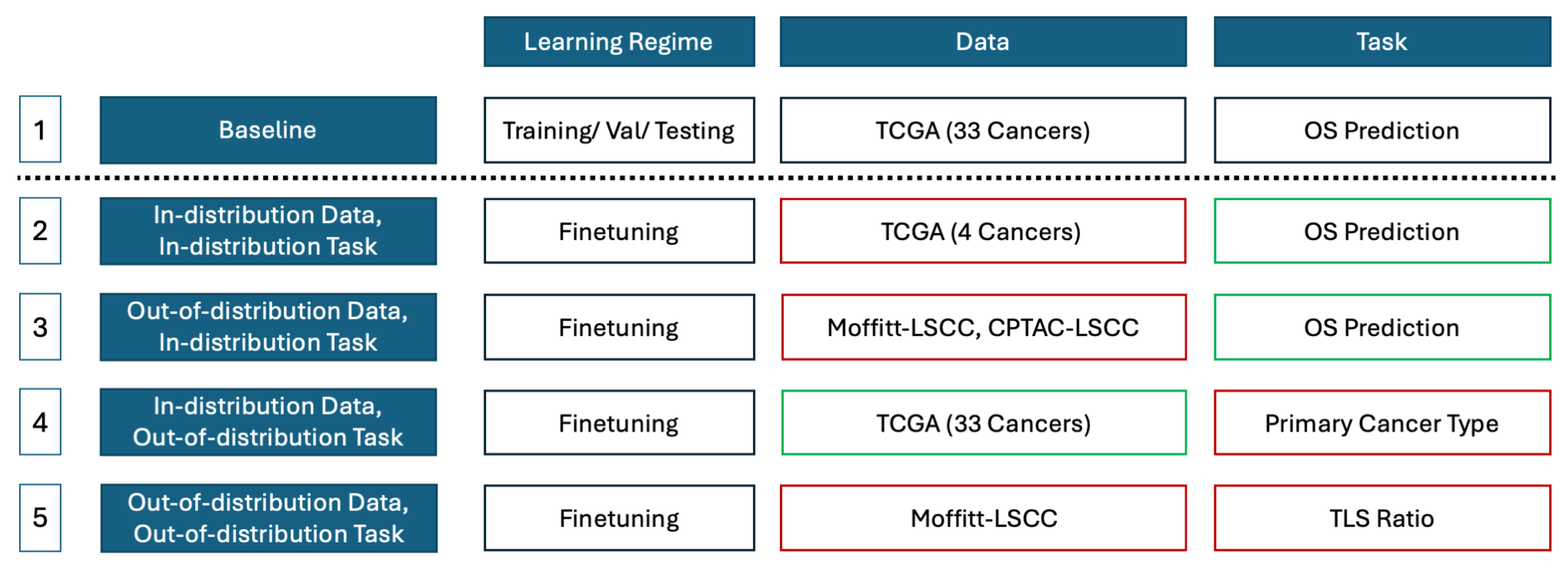

3.7. Study Design

4. Results

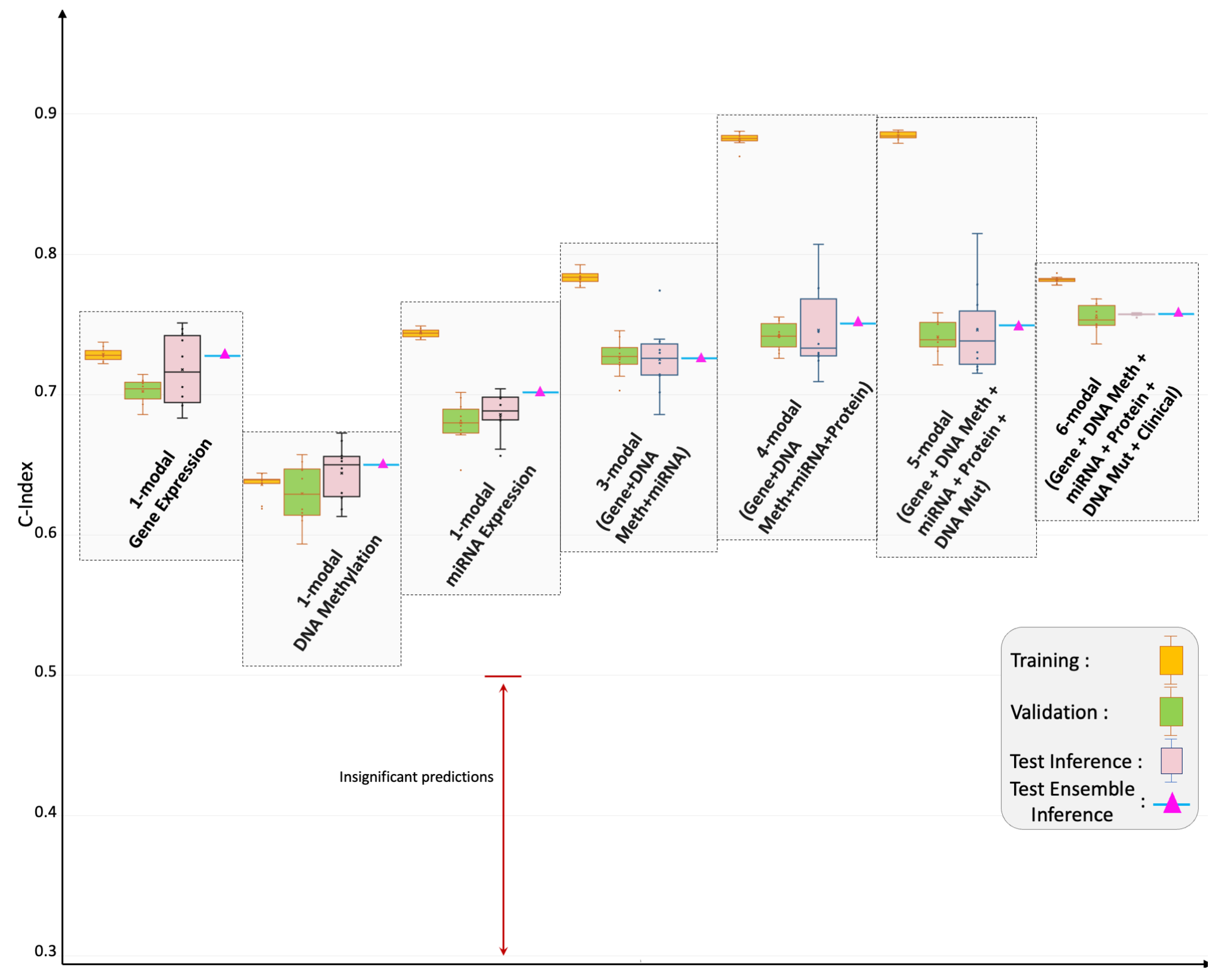

4.1. Pan-Cancer Multimodal Analysis for Predicting OS

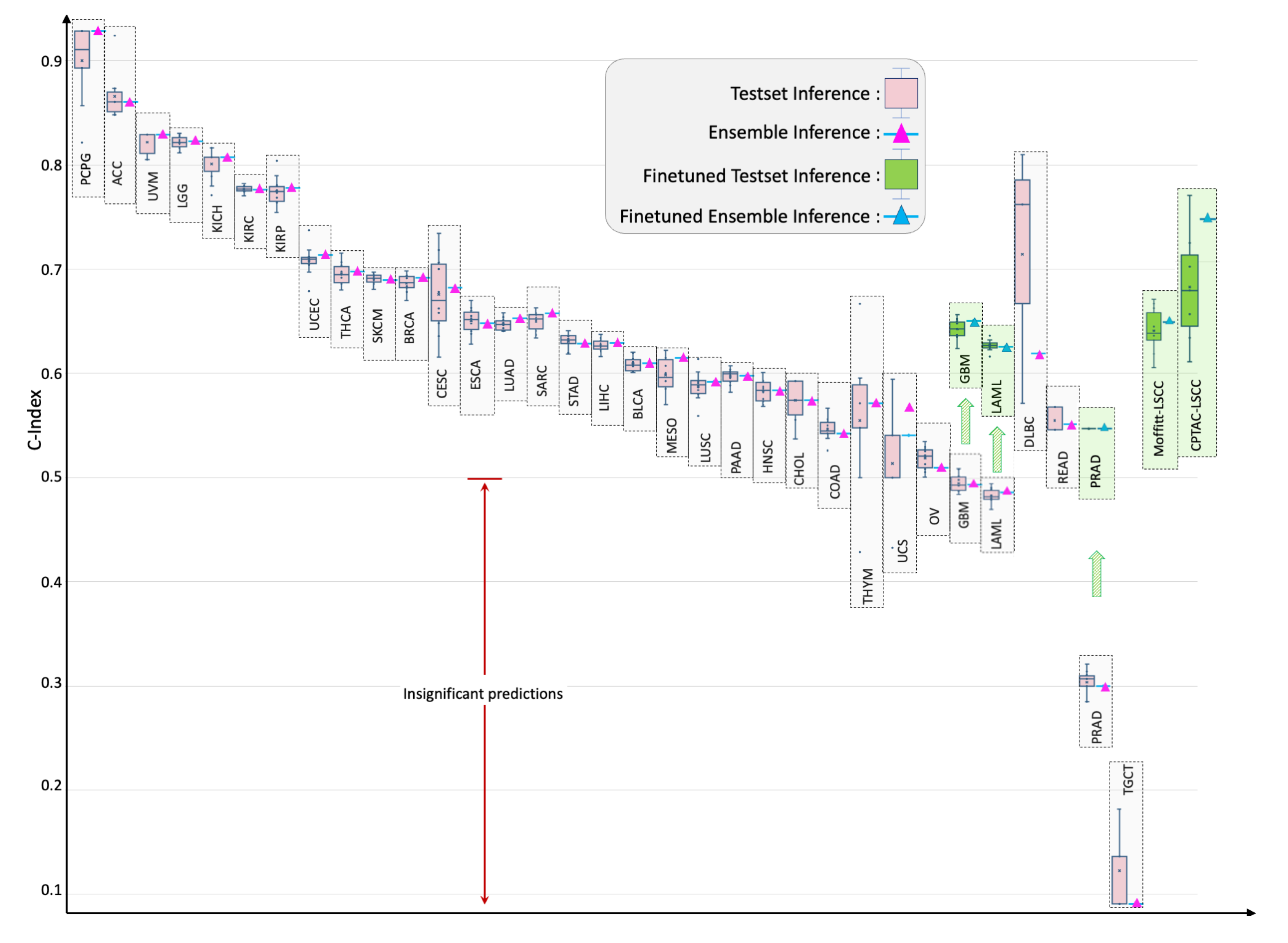

4.2. Individual Cancer Multimodal Analysis for Predicting OS

4.3. Out-of-Distribution Evaluation and Fine-Tuning

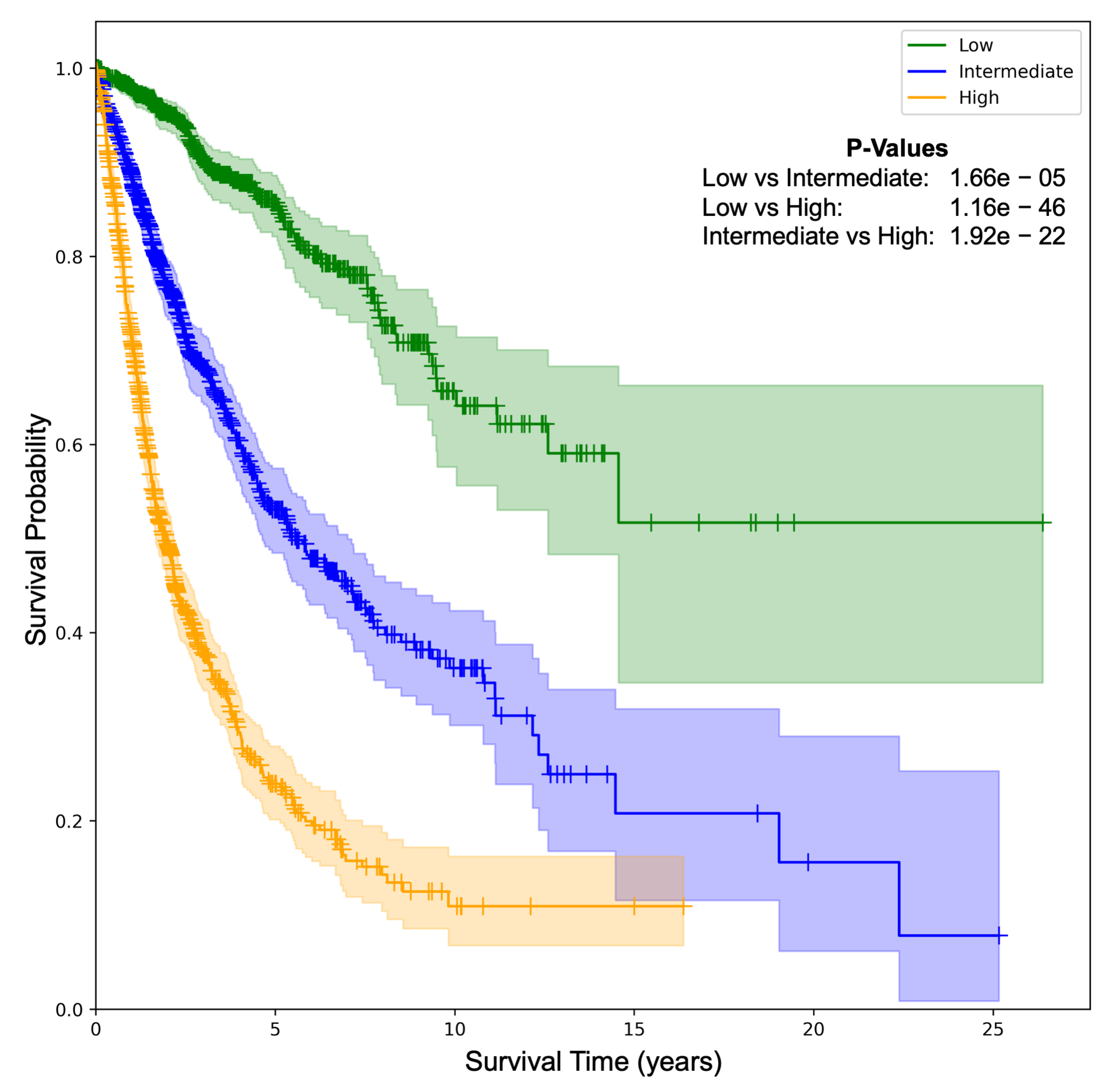

4.4. Patient Stratification

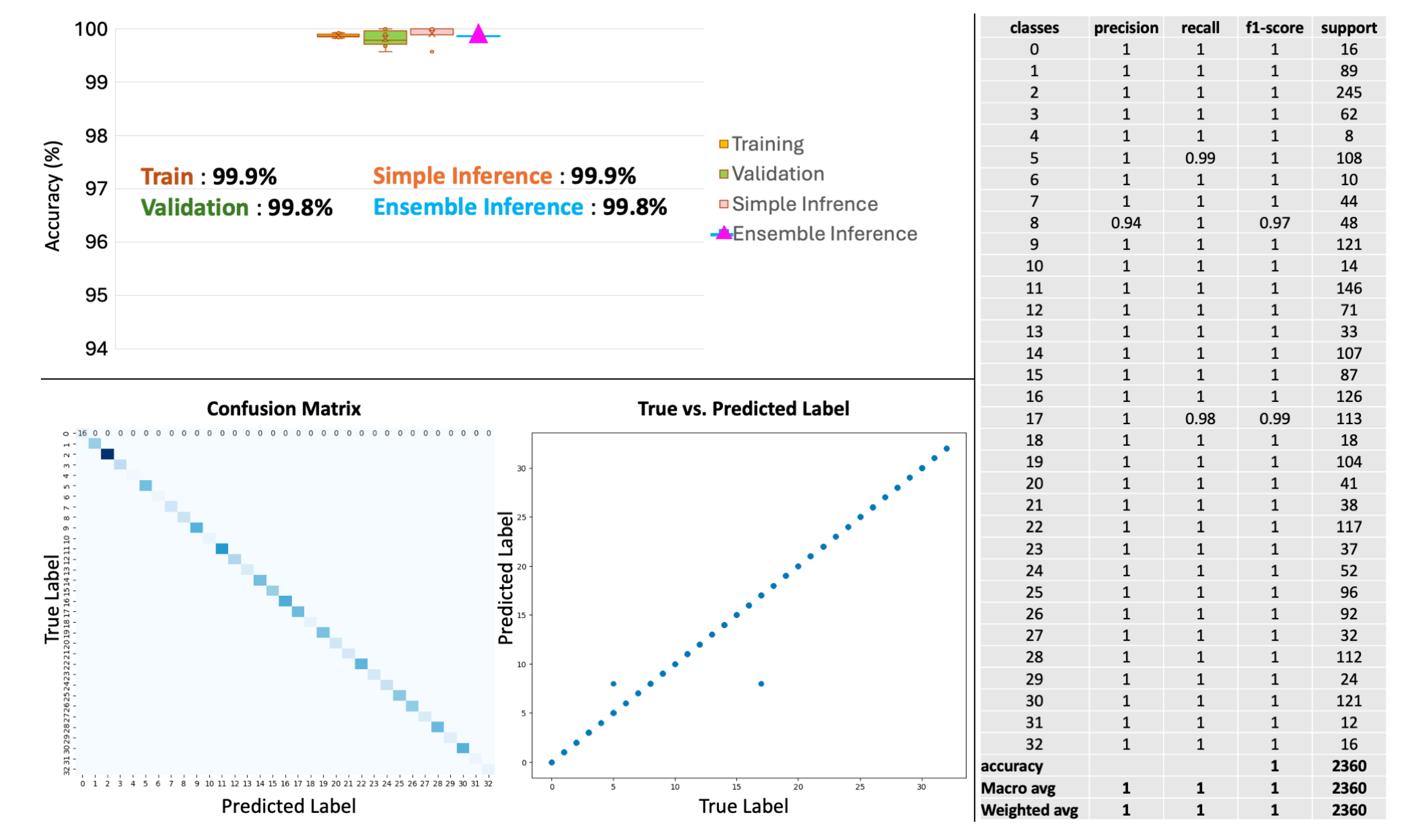

4.5. Primary Cancer Type Prediction

4.6. Tertiary Lymph Structures (TLS) Ratio

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Multi-Omic Data Modalities

- DNA methylation: DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification involving the addition of methyl groups to the DNA molecule, typically at cytosine bases adjacent to guanine, known as CpG sites [63]. This modification plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [63]. In cancer, aberrant methylation can lead to the silencing or activation of genes, contributing to oncogenesis and tumor progression [64]. Analyzing methylation profiles across different cancer types helps identify risk and diagnostic markers, predict disease progression, and support personalized treatment strategies [64]. DNA methylation is quantified through beta values ranging from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating increased methylation [65]. The beta values for TCGA-GDC methylation data were obtained using the Illumina Human Methylation 450 platform, which provides detailed methylation profiling [66]. The dataset contains 485,576 unique cg and rs methylation sites across multiple tumor types [66].

- Gene expression (RNAseq): Gene expression analysis through RNA sequencing (RNAseq) is a powerful modality in cancer research, providing insights into the transcriptomic landscape of tumors [67]. This technique quantifies the presence and quantity of RNA in a biological sample, giving a detailed view of transcriptional activity in a cell [67]. RNAseq helps identify genes that are upregulated or downregulated in cancer cells compared to normal cells, offering clues about oncogenic pathways and potential therapeutic targets [68]. TCGA-GDC gene expression data was obtained from RNAseq, utilizing High-throughput sequence Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (HTseq-FPKM) for normalization [69]. This approach normalizes raw read counts by gene length and the number of mapped reads, with further processing involving incrementing the FPKM value by one followed by log transformation to stabilize variance and enhance statistical analysis [70]. The dataset includes 60,483 genes, with FPKM values indicating gene expression levels. Values above 1000 signify high expression, while values between 0.5 and 10 indicate low expression [69,71]. Importantly, TCGA-GDC uses annotation sources such as GENCODE or Ensembl, which catalog various gene types beyond just protein-coding ones, resulting in a comprehensive transcriptome dataset rather than a protein-coding gene-only dataset [33].

- miRNA stem loop expression: miRNA stem-loop expression plays a pivotal role in understanding the regulatory mechanisms of miRNAs (microRNAs) in gene expression [72]. miRNAs are small, non-coding RNA molecules that function by binding to complementary sequences on target mRNA transcripts, leading to silencing [72]. The expression of miRNAs involves multiple steps to ensure specific targeting and effective modulation of gene expression, which is crucial for normal cellular function as well as pathological conditions like cancer [72]. miRNA expression values for TCGA-GDC were measured using stem-loop expression through Illumina, and values were log-transformed after the addition of one [73,74]. The data represents 1880 features across hsa-miRNA sites, with expression levels varying between high and low.

- Protein expression: Reverse Phase Protein Array (RPPA) is a laboratory technique similar to western blotting, used to quantify protein expression in tissue samples [75]. The method involves transferring antibodies onto nitrocellulose-coated slides to bind specific proteins, forming quantifiable spots via a DAB calorimetric reaction and tyramide dye deposition, analyzed using “SuperCurve Fitting" software [75,76]. RPPA effectively compares protein expression levels in tumor and benign samples, highlighting aberrant protein levels that define the molecular phenotypes of cancer [75,77]. RPPA data in TCGA was derived from profiling nearly 500 antibody-proteins for each patient and deposited in The Cancer Proteome Atlas portal [78]. Each dataset includes the antigen ID, peptide target ID, gene identifier that codes for the protein, and antigen expression levels. Protein expression levels were normalized through log transformation and median centering after being calculated by SuperCurve fitting software [79].

- DNA mutation: Analyzing DNA sequences involves identifying mutated regions compared to a reference genome, resulting in Variant Calling Format (VCF) files detailing these differences [80,81]. Aggregating VCF files to exclude low-quality variants and include only somatic mutations produces Mutation Annotation Format (MAF) files [82]. Unlike VCF files, which consider all reference transcripts, MAF files focus on the most affected references and include detailed characteristics and quantifiable scores that assess a mutation’s translational impact and clinical significance [82]. This information is critical because clinically significant mutations often result in major defects in protein structure, severely impacting downstream functions and contributing to cancer development [83]. The MAF files from TCGA-GDC contain 18,090 mutational characteristics [82].

- Clinical data: Clinical and patient-level data play a crucial role in cancer research, providing the foundation for identifying and characterizing patient cohorts [84]. Clinical data includes detailed patient information that is instrumental in understanding cancer epidemiology, evaluating treatment responses, and improving prognostic assessments [84]. Integrating clinical data with genomic and proteomic analyses can uncover relationships between molecular profiles and clinical manifestations of cancer [6]. Key clinical and patient-level covariates such as age, gender, race, and disease stage are particularly important in cancer research due to their impact on disease presentation, progression, and treatment efficacy [85,86,87,88]. Age is a critical factor as cancer incidence and type often vary significantly with age, influencing both the biological behavior of tumors and patient prognosis [85]. Gender also plays an important role, with certain cancers being gender-specific and others differing in occurrence and outcomes between genders due to biological, hormonal, and social factors [86]. Race and ethnicity are linked to differences in cancer susceptibility, mortality rates, and treatment outcomes, which reflect underlying genetic, environmental, and socioeconomic factors [87]. Finally, cancer stage and histology at diagnosis are paramount for determining disease extent, guiding treatment decisions, and correlating directly with survival rates [88].

Appendix B. Model Evaluation

-

Loss Function: TThe loss being used for backpropagation in the model is a combination of three components: Cox loss, cross-entropy loss, and regularization loss. This combined loss function aims to simultaneously optimize the model’s ability to predict survival outcomes (Cox loss), encourage model-simplicity or sparsity (regularization loss), and model the likelihood of cancer types (cross-entropy loss). The overall loss is a weighted sum of these three components, where each component is multiplied by a corresponding regularization hyperparameter (, , ). This weighted sum allows for balancing the influence of each loss component on the optimization process. Mathematically, the overall loss can be expressed as:

- Cox proportional hazards loss (): Cox loss is a measure of dissimilarity between the predicted hazard scores and the true event times in survival analysis. It is calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model and penalizes deviations between predicted and observed survival outcomes of all individuals who are at risk at time , weighted by the censoring indicator [89]. The function takes a vector of survival times for each individual in the batch, censoring status for each individual (1 if the event occurred, 0 if censored), and the predicted log hazard ratio for each individual from the neural network, and returns the Cox loss for the batch, which is used to train the neural network via backpropagation. This backpropagation encourages the model to assign higher hazards to high-risk individuals and lower predicted hazards to censored individuals or those who experience the event later. Mathematically, the Cox loss is expressed as:where N is the batch size (number of samples), is the predicted hazard for sample i, is the indicator function that equals 1 if the survival time of sample j is greater than or equal to the survival time of sample i, and 0 otherwise, and is the censoring indicator for sample i, which equals 1 if the event is observed for sample i and 0 otherwise.

- Cross-entropy loss (): The cross-entropy loss is a common loss function used for multi-class classification problems, particularly when each sample belongs to one of the C classes. When combined with a LogSoftmax layer, the function measures how well a model’s predicted log probabilities match the true distribution across various classes. For a multi-class classification problem having C classes, the model’s outputs (raw class scores or logits) are transformed into log probabilities using a LogSoftmax layer. The cross-entropy loss compares these log probabilities to the true distribution, which is usually represented in a one-hot encoded format. The loss is calculated by negating the log probability of the true class across all samples in a batch and then averaging these values. For the given output of LogSoftmax, for each class c in each sample n, the cross-entropy loss for a multi-class problem can be defined as:where N is the total number of samples, C are the total classes, and is the target label for sample n and class c, typically 1 for the true class and 0 otherwise.

- Regularization loss (): The regularization loss encourages the model’s weights to remain small or sparse, thus preventing overfitting and improving generalization. We used regularization to the SeNMo’s parameters, which penalizes the absolute values of the weights.

- Concordance Index (C-index): The C-index is a key metric in survival analysis that evaluates a model’s predictive accuracy for time-to-event outcomes by measuring how well it ranks subjects based on predicted survival times [55]. It represents the probability that, in a randomly selected pair, the subject experiencing the event first has a higher predicted risk score. We used the function from Lifelines, which computes the fraction of correctly ordered event pairs among all comparable pairs [90]. The C-index ranges from 0 to 1, where 0.5 indicates random predictions, 1.0 perfect concordance, and 0.0 perfect anti-concordance [55]. Mathematically,where concordant pairs are those where predicted survival times correctly align with observed outcomes, while tied pairs occur when predictions or survival times are identical. Total number of evaluable pairs excludes cases with censoring or other exclusions. Predicted risks or survival probabilities for individuals i and j are and , respectively. A true event ordering () means individual i experienced the event before j, and indicates that the event for i was observed (not censored).

-

Cox log-rank function: The Cox log-rank function calculates the p-value using the log-rank test based on predicted hazard scores, censor values, and true OS times. The log-rank test is a statistical method to compare the survival distributions of two groups or more groups, where the null hypothesis is that there is no difference between the groups. For the hazard ratio of group i at time t, the hypotheses are given by,The log-rank test statistic is computed by summing the squared differences between observed and expected events, divided by the expected events, across all time points. The resulting p-value indicates the significance of survival differences between groups. Under the null hypothesis, the test statistic follows a chi-squared distribution [90].where is the observed number of events at time point i in the sample, is the expected number of events at time point i under the null hypothesis, and N is the total number of observed time points.

- Huber Loss: For TLS ratio prediction, we used Huber Loss, a loss function commonly used in regression tasks, known for combining the advantages of both the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and the Mean Squared Error (MSE). It behaves differently based on the magnitude of the error; it is quadratic for small errors and linear for large errors. This characteristic makes it less sensitive to outliers than MSE and more sensitive to small errors than MAE. Huber loss function is defined as follows:where represents the residual, which is the difference between the actual value and the predicted value, and is a positive threshold parameter that determines the point at which the loss function transitions from quadratic to linear behavior [91].

- Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test: We used the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test to evaluate the agreement between the manually annotated TLS ratio and the model’s predictions. This non-parametric test considers both the magnitude and direction of differences in paired values. The null hypothesis assumes no significant difference between the distributions, with a two-sided p-value < 0.05 indicating a statistically significant discrepancy.

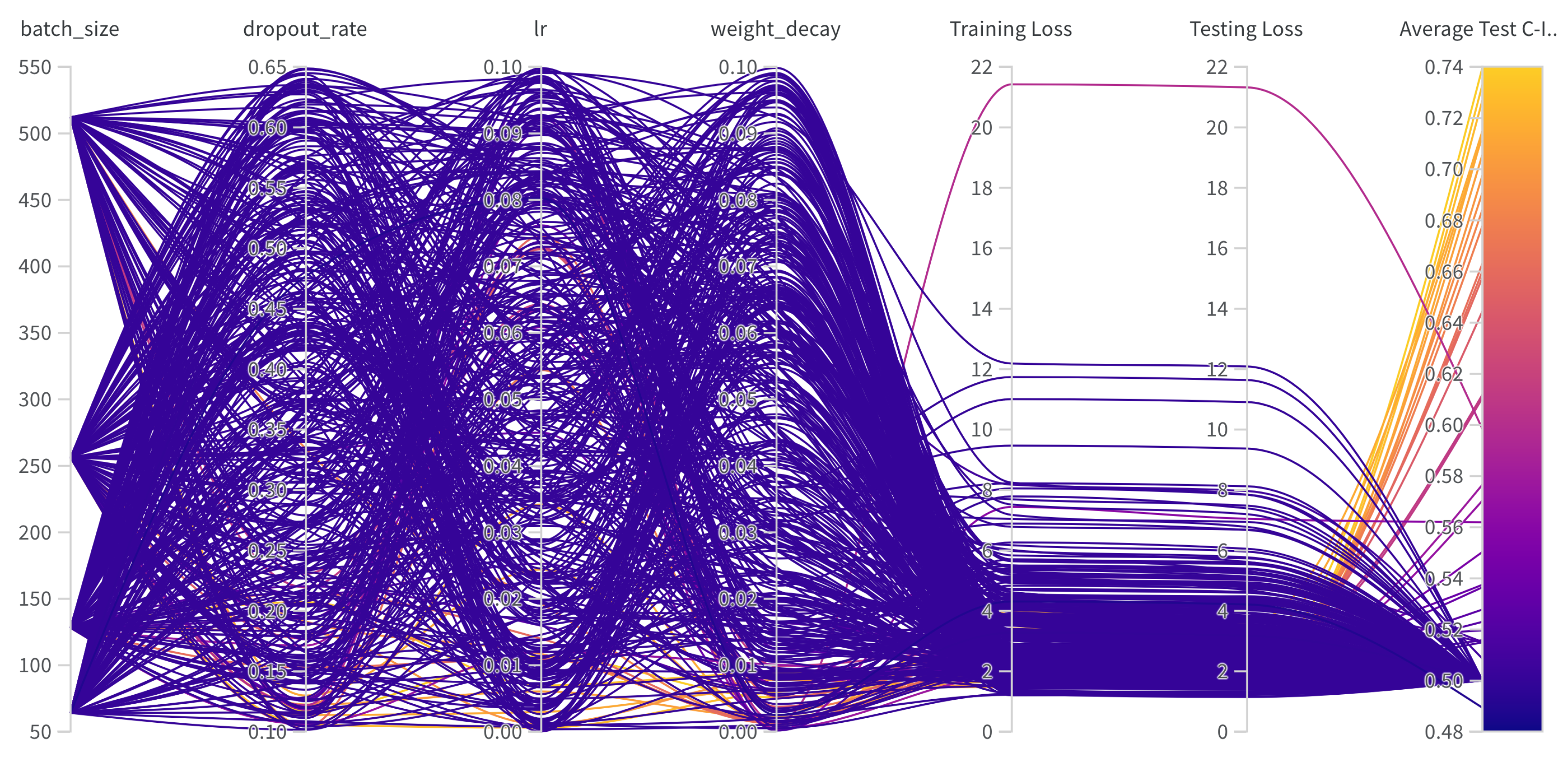

Appendix C. Hyperparameters Search

| Hyperparams | Training (range) |

|---|---|

| Learning Rate | [1e-6, 1e-1] |

| Weight Decay | [1e-6, 1e-1] |

| Dropout | [0.1, 0.65] |

| Batch Size | [64, 128, 256, 512] |

| Epochs | [50, 100] |

| Hidden Layers | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] |

| Hidden Neurons | [2048, 1024, 512, 256, 128, 48, 32] |

| Optimizer | [adam, sgd, rmsprop, adamw] |

| Learning Rate Policy | [linear, exp, step, plateau, cosine] |

Appendix D. Frameworks, Compute Resources, and Wall-Clock Times

| Package name | Version | |

|---|---|---|

| Operating systems | Ubuntu | 20.04.4 |

| Programming languages | Python | 3.10.13 |

| Deep learning framework | Pytorch | 2.2.0 |

| torchvision | 0.17.0 | |

| feature-engine | 1.6.2 | |

| imbalanced-learn | 0.12.0 | |

| Miscellaneous | scipy | 1.12.0 |

| scikit-learn | 1.4.0 | |

| numpy | 1.26.3 | |

| PyYaml | 6.0.1 | |

| jupyter | 1.0.0 | |

| pandas | 2.2.0 | |

| pickle5 | 0.0.11 | |

| protobuf | 4.25.2 | |

| wandb | 0.16.3 |

References

- Jiang, P.; Sinha, S.; Aldape, K.; Hannenhalli, S.; Sahinalp, C.; Ruppin, E. Big data in basic and translational cancer research. Nature Reviews Cancer 2022, 22, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, J.N.; Falcone, G.J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Topol, E.J. Multimodal biomedical AI. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatsirisupachai, K.; Lesluyes, T.; Paraoan, L.; Van Loo, P.; De Magalhães, J.P. An integrative analysis of the age-associated multi-omic landscape across cancers. Nature communications 2021, 12, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D. Next-generation sequencing and its clinical application. Cancer biology & medicine 2019, 16, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Waqas, A.; Tripathi, A.; Ramachandran, R.P.; Stewart, P.; Rasool, G. Multimodal data integration for oncology in the era of deep neural networks: a review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.06471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistyakov, D.V.; Guryleva, M.V.; Stepanova, E.S.; Makarenkova, L.M.; Ptitsyna, E.V.; Goriainov, S.V.; Nikolskaya, A.I.; Astakhova, A.A.; Klimenko, A.S.; Bezborodova, O.A.; et al. Multi-omics approach points to the importance of oxylipins metabolism in early-stage breast cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, I.; Yang, L.; Yin, F.T.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.H.; Li, J.; Wang, X.J. Multi-omics approaches in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis, recent updates and future perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Hsu, C.L.; Wang, H.M.; Wu, S.G.; Chang, Y.L.; Chen, J.S.; Wu, Y.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Yang, C.Y.; Lin, M.W.; et al. Multiomics Analysis Reveals Molecular Changes during Early Progression of Precancerous Lesions to Lung Adenocarcinoma in Never-Smokers. Cancer Research 2025, 85, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Deshpande, A.; Verma, B.K.; Wang, H.; Mi, H.; Yuan, L.; Ho, W.J.; Jaffee, E.M.; Zhu, Q.; Anders, R.A.; et al. Integration of clinical trial spatial multiomics analysis and virtual clinical trials enables immunotherapy response prediction and biomarker discovery. Cancer Research 2024, 84, 2734–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, T. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 2020, 578, 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zgura, A.; Chipuc, S.; Bacalbasa, N.; Haineala, B.; Rodica, A.; Sebastian, V. Evaluating Tumour Mutational Burden as a Key Biomarker in Personalized Cancer Immunotherapy: A Pan-Cancer Systematic Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divate, M.; Tyagi, A.; Richard, D.J.; Prasad, P.A.; Gowda, H.; Nagaraj, S.H. Deep learning-based pan-cancer classification model reveals tissue-of-origin specific gene expression signatures. Cancers 2022, 14, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.J.; Park, U.H.; Goh, C.J.; Park, D.; Lim, Y.G.; Lee, I.K.; Do, W.J.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, H.; Yun, S.Y.; et al. Enhancing lung cancer classification through integration of liquid biopsy multi-omics data with machine learning techniques. Cancers 2023, 15, 4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Nielsen, I.E.; Tripathi, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Ramachandran, R.P.; Rasool, G. Transformers in time-series analysis: A tutorial. Circuits, Systems, and Signal Processing 2023, 42, 7433–7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Dera, D.; Rasool, G.; Bouaynaya, N.C.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. Brain tumor segmentation and surveillance with deep artificial neural networks. Deep Learning for Biomedical Data Analysis: Techniques, Approaches, and Applications 2021, pp. 311–350.

- Ahmed, S.; Dera, D.; Hassan, S.U.; Bouaynaya, N.; Rasool, G. Failure detection in deep neural networks for medical imaging. Frontiers in Medical Technology 2022, 4, 919046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Farooq, H.; Bouaynaya, N.C.; Rasool, G. Exploring robust architectures for deep artificial neural networks. Communications Engineering 2022, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, S.; Pizurica, M.; Nagaraj, D.; Khandelwal, P.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Gentles, A.J.; Gevaert, O. Multimodal data fusion for cancer biomarker discovery with deep learning. Nature machine intelligence 2023, 5, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, Q.; Wu, M.; Huang, T.; Wang, Y. Pan-cancer classification based on self-normalizing neural networks and feature selection. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, 8, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Lu, M.Y.; Williamson, D.F.; Chen, T.Y.; Lipkova, J.; Noor, Z.; Shaban, M.; Shady, M.; Williams, M.; Joo, B.; et al. Pan-cancer integrative histology-genomic analysis via multimodal deep learning. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirion, O.B.; Jing, Z.; Chaudhary, K.; Huang, S.; Garmire, L.X. DeepProg: an ensemble of deep-learning and machine-learning models for prognosis prediction using multi-omics data. Genome medicine 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadirnaikar, S.; Shukla, S.; Prasanna, S. Integration of pan-cancer multi-omics data for novel mixed subgroup identification using machine learning methods. Plos one 2023, 18, e0287176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, A. Integrate multi-omics data with biological interaction networks using Multi-view Factorization AutoEncoder (MAE). BMC genomics 2019, 20, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellen, J.G.; Jacob, E.; Nikolaou, N.; Markuzon, N. Autoencoder-based multimodal prediction of non-small cell lung cancer survival. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 15761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Guo, M.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X. Identification of pan-cancer prognostic biomarkers through integration of multi-omics data. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, 8, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, N.; Salazar, D.; RaviPrakash, H.; Goncalves, M.; Mulla, R.; Burlutskiy, N.; Markuzon, N.; Jacob, E. Quantifying the advantage of multimodal data fusion for survival prediction in cancer patients. bioRxiv 2024, pp. 2024–01.

- Rong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Song, J.; Cao, L.; Yu, Y.; Qiu, M.; Hou, Y. MCluster-VAEs: an end-to-end variational deep learning-based clustering method for subtype discovery using multi-omics data. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 150, 106085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Liu, D.; Dou, Y.; Wang, L.; Feng, Z.; Rong, P.; Xu, L.; Peng, S. Multi-Head Attention Mechanism Learning for Cancer New Subtypes and Treatment Based on Cancer Multi-Omics Data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.04075. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W.; Sun, M.; Lian, J.; Hou, S. Feature dimensionality reduction: a review. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2022, 8, 2663–2693. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczuk, J.; ukaszuk, T. The feature selection bias problem in relation to high-dimensional gene data. Artificial intelligence in medicine 2016, 66, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guo, X.; Yu, K.; Huang, X.; Jiang, T.; He, J.; Gu, L. Causal feature selection in the presence of sample selection bias. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2023, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Collisson, E.A.; Mills, G.B.; Shaw, K.R.; Ozenberger, B.A.; Ellrott, K.; Shmulevich, I.; Sander, C.; Stuart, J.M. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nature genetics 2013, 45, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, M.J.; Gillette, M.; Carr, S.A.; Paulovich, A.G.; Smith, R.D.; Rodland, K.K.; Townsend, R.R.; Kinsinger, C.; Mesri, M.; Rodriguez, H.; et al. Connecting Genomic Alterations to Cancer Biology with Proteomics: The NCI Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium. Cancer Discovery 2013, 3, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Wang, C.; Maan, H.; Pang, K.; Luo, F.; Duan, N.; Wang, B. scGPT: toward building a foundation model for single-cell multi-omics using generative AI. Nature Methods, 2024; 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Chen, Y.; Nie, S.; Yang, H. SAMMS: Multi-modality Deep Learning with the Foundation Model for the Prediction of Cancer Patient Survival. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). IEEE; 2023; pp. 3662–3668. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Hu, Z.; Sun, S.; Tan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zong, L.; Hong, L.; Xiao, J.; Shen, T.; et al. Interpretable RNA foundation model from unannotated data for highly accurate RNA structure and function predictions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.00300 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Gu, P.; Sapkota, N.; Chen, D.Z. Path-GPTOmic: A Balanced Multi-modal Learning Framework for Survival Outcome Prediction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.11375 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, A.; Waqas, A.; Venkatesan, K.; Yilmaz, Y.; Rasool, G. Building Flexible, Scalable, and Machine Learning-ready Multimodal Oncology Datasets. Sensors 2024, 24, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M.; Craft, B.; Hastie, M.; Repečka, K.; McDade, F.; Kamath, A.; Banerjee, A.; Luo, Y.; Rogers, D.; Brooks, A.N.; et al. The UCSC Xena platform for public and private cancer genomics data visualization and interpretation. biorxiv 2018, p. 326470.

- Satpathy, S.; Krug, K.; Beltran, P.M.J.; Savage, S.R.; Petralia, F.; Kumar-Sinha, C.; Dou, Y.; Reva, B.; Kane, M.H.; Avanessian, S.C.; et al. A proteogenomic portrait of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Cell 2021, 184, 4348–4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.A.; Welsh, E.A.; Slebos, R.J.; Fang, B.; Izumi, V.; Chambers, M.; Zhang, G.; Cen, L.; Pettersson, F.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Proteogenomic landscape of squamous cell lung cancer. Nature communications 2019, 10, 3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhadi, V.K.; Armengol, G. Molecular biomarkers in cancer. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Tokheim, C.; Bailey, M.H.; Yaron, T.M.; Stathias, V.; Geffen, Y.; Imbach, K.J.; Cao, S.; Anand, S.; et al. Pan-cancer proteogenomics connects oncogenic drivers to functional states. Cell 2023, 186, 3921–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wendl, M.C.; Wyczalkowski, M.A.; Bailey, M.H.; Li, Y.; Ding, L. Moving pan-cancer studies from basic research toward the clinic. Nature cancer 2021, 2, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Chin, K.V. Logistic regression for disease classification using microarray data: model selection in a large p and small n case. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1945–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, S. Feature-engine: A Python package for feature engineering for machine learning. Journal of Open Source Software 2021, 6, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommert, A.; Welchowski, T.; Schmid, M.; Rahnenführer, J. Benchmark of filter methods for feature selection in high-dimensional gene expression survival data. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 23, bbab354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Anggraeny, F.T.; Purbasari, I.Y.; Munir, M.S.; Muttaqin, F.; Mandyarta, E.P.; Akbar, F.A. Analysis of Simple Data Imputation in Disease Dataset. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST 2018). Atlantis Press; 2018; pp. 471–475. [Google Scholar]

- Ulriksborg, T.R. Imputation of missing time series values using statistical and mathematical strategies. Department of Informatics 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.J.; Hwang, S.J.; Yang, E. Why not to use zero imputation? correcting sparsity bias in training neural networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.00150 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.J.; Lu, M.Y.; Wang, J.; Williamson, D.F.; Rodig, S.J.; Lindeman, N.I.; Mahmood, F. Pathomic fusion: an integrated framework for fusing histopathology and genomic features for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2020, 41, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, J.; Roncador, G.; Hamoudi, R. Artificial intelligence predicted overall survival and classified mature B-cell neoplasms based on immuno-oncology and immune checkpoint panels. Cancers 2022, 14, 5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zobolas, J.; Zucknick, M.; Aittokallio, T. Tutorial on survival modeling with applications to omics data. Bioinformatics 2024, btae132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Mariotto, A.B.; Rowland, J.H.; Yabroff, K.R.; Alfano, C.M.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.L.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2019, 69, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rijthoven, M.; Obahor, S.; Pagliarulo, F.; van den Broek, M.; Schraml, P.; Moch, H.; van der Laak, J.; Ciompi, F.; Silina, K. Multi-resolution deep learning characterizes tertiary lymphoid structures and their prognostic relevance in solid tumors. Communications Medicine 2024, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Jin, Z.; Li, B.; Jiang, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, D.; Yuan, P.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Deep learning on tertiary lymphoid structures in hematoxylin-eosin predicts cancer prognosis and immunotherapy response. NPJ Precision Oncology 2024, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klambauer, G.; Unterthiner, T.; Mayr, A.; Hochreiter, S. Self-normalizing neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, M.; Li, R.; Xia, Y. Survival prediction via hierarchical multimodal co-attention transformer: A computational histology-radiology solution. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Vaidya, S.; Ruehle, F.; Halverson, J.; Soljačić, M.; Hou, T.Y.; Tegmark, M. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19756 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, S.; Azad, R.K. CancerNet: a unified deep learning network for pan-cancer diagnostics. BMC bioinformatics 2022, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyfer, N.; Magenheim, J.; Peretz, A.; Cann, G.; Bredno, J.; Klochendler, A.; Fox-Fisher, I.; Shabi-Porat, S.; Hecht, M.; Pelet, T.; et al. A DNA methylation atlas of normal human cell types. Nature 2023, 613, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarasimhan, R.; Liang, G. The role of DNA methylation in cancer. DNA Methyltransferases-Role and Function 2016, pp. 151–172.

- Du, P.; Zhang, X.; Huang, C.C.; Jafari, N.; Kibbe, W.A.; Hou, L.; Lin, S.M. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC bioinformatics 2010, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y. A framework for analyzing DNA methylation data from Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip. BMC bioinformatics 2018, 19, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corchete, L.A.; Rojas, E.A.; Alonso-López, D.; De Las Rivas, J.; Gutiérrez, N.C.; Burguillo, F.J. Systematic comparison and assessment of RNA-seq procedures for gene expression quantitative analysis. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 19737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazo-Pechero, S.; Alay, A.; Marín, R.; Vilariño, N.; Muñoz-Pinedo, C.; Villanueva, A.; Santamaría, D.; Nadal, E.; Solé, X. Gene expression profiling as a potential tool for precision oncology in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Leon, D.A.; Perera, Y.; Perez, R. On the gene expression landscape of cancer. Plos one 2023, 18, e0277786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, A.; Flister, M.; Rui, H.; Auer, P.L. Exploring drivers of gene expression in the Cancer Genome Atlas. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Expression, G. Expression atlas, 2024. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk.

- Peng, Y.; Croce, C.M. The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2016, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, A.; Robertson, G.; Brooks, D.; Mungall, A.J.; Birol, I.; Coope, R.; Ma, Y.; Jones, S.; Marra, M.A. Large-scale profiling of microRNAs for the cancer genome atlas. Nucleic acids research 2016, 44, e3–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhou, J.; Xiao, Y.; Neary, B.; Teng, Y.; Qiu, P. Integrative analysis of TCGA data identifies miRNAs as drug-specific survival biomarkers. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Documentation, G. Reverse Phase Protein Array. Available online: https://docs.gdc.cancer.gov/Data/Bioinformatics_Pipelines/RPPA_intro/ (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Anderson, M. RPPA Description. 2024. Available online: https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/core-facilities/Functional Proteomics RPPA Core Facility/RPPA Description2016.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Chen, M.J.M.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Akbani, R.; Lu, Y.; Mills, G.B.; Liang, H. TCPA v3. 0: an integrative platform to explore the pan-cancer analysis of functional proteomic data. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2019, 18, S15–S25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Akbani, R.; Ju, Z.; Roebuck, P.L.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.Y.; Broom, B.M.; Verhaak, R.G.; Kane, D.W.; et al. TCPA: a resource for cancer functional proteomics data. Nature methods 2013, 10, 1046–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Liu, W.; Roebuck, P.L.; Siwak, D.R.; Zhang, N.; Lu, Y.; Davies, M.A.; Akbani, R.; Weinstein, J.N.; Mills, G.B.; et al. Development of a robust classifier for quality control of reverse-phase protein arrays. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commons, G.D. Mutation Annotation Format. 2024. Available online: https://docs.gdc.cancer.gov/Encyclopedia/pages/Mutation_Annotation_Format/ (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Commons, G.D. File Format - VCF. 2024. Available online: https://docs.gdc.cancer.gov/Data/File_Formats/VCF_Format/ (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Commons, G.D. File Format - MAF. 2024. Available online: https://docs.gdc.cancer.gov/Data/File_Formats/MAF_Format/ (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Mendiratta, G.; Ke, E.; Aziz, M.; Liarakos, D.; Tong, M.; Stites, E.C. Cancer gene mutation frequencies for the US population. Nature communications 2021, 12, 5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, O.; Vallières, M.; Braunstein, S.; Ginart, J.B.; Upadhaya, T.; Woodruff, H.C.; Zwanenburg, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Valdes, G.; et al. An artificial intelligence framework integrating longitudinal electronic health records with real-world data enables continuous pan-cancer prognostication. Nature Cancer 2021, 2, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowska, A.; Rudzki, G.; Lewandowski, T.; Stryjkowska-Gora, A.; Rudzki, S. Risk factors for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Cancer Control 2022, 29, 10732748211056692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes-Ramos, C.M.; Quackenbush, J.; DeMeo, D.L. Genome-wide sex and gender differences in cancer. Frontiers in oncology 2020, 10, 597788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, V.A.; Bracci, P.M.; Carethers, J.M.; Carvajal-Carmona, L.; Coggins, N.B.; Cruz-Correa, M.R.; Davis, M.; de Smith, A.J.; Dutil, J.; Figueiredo, J.C.; et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. British journal of cancer 2021, 124, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Mu, D.; Peng, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Han, S. Research and application of artificial intelligence based on electronic health records of patients with cancer: systematic review. JMIR Medical Informatics 2022, 10, e33799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T. Cox regression. 2024. Available online: http://traversc.github.io/cox-nnet/docs/ (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Davidson-Pilon, C. lifelines, survival analysis in Python. [CrossRef]

- Documentation, P. HuberLoss. 2024. Available online: https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/generated/torch.nn.HuberLoss.html (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Biewald, L. Experiment Tracking with Weights and Biases. Software available from wandb.com. 2020. Available online: https://www.wandb.com/.

| Data (TCGA-GDC) | Primary Site | Cases | miRNA Exprn | DNA Methyl | Gene Exprn | Protein Exprn | DNA Mut | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |||

| TCGA-DLBC | Large B-cell Lymphoma | 51 | 1880 | 1060 | 485576 | 4396 | 60483 | 850 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-UCS | Uterine Carcinosarcoma | 61 | 1880 | 1101 | 485576 | 4632 | 60483 | 1231 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-CHOL | Bile Duct | 62 | 1880 | 967 | 485576 | 4479 | 60483 | 1261 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-UVM | Uveal melanomas | 80 | 1880 | 1162 | 485576 | 4019 | 60483 | 772 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-MESO | Mesothelioma | 86 | 1880 | 1158 | 485576 | 4372 | 60483 | 1278 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-ACC | Adrenocortical | 95 | 1880 | 1110 | 485576 | 4454 | 60483 | 1304 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-THYM | Thymoma | 138 | 1880 | 1245 | 485576 | 4609 | 60483 | 1337 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-TGCT | Testicular | 139 | 1880 | 1290 | 485576 | 4762 | 60483 | 1343 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-READ | Rectal | 178 | 1880 | 1314 | 485576 | 4077 | 60483 | 1547 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-KICH | Kidney Chromophobe | 182 | 1880 | 1089 | 485576 | 4333 | 60483 | 1107 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-PCPG | Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma | 189 | 1880 | 1251 | 485576 | 4550 | 60483 | 1216 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-PAAD | Pancreatic | 222 | 1880 | 1308 | 485576 | 4518 | 60483 | 1567 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-ESCA | Esophageal | 249 | 1880 | 1300 | 485576 | 4192 | 60483 | 1684 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-SARC | Sarcoma | 287 | 1880 | 1235 | 485576 | 4467 | 60483 | 2490 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-CESC | Cervical | 304 | 1880 | 1405 | 485576 | 4167 | 60483 | 2017 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-KIRP | Kidney Papillary Cell Carcinoma | 376 | 1880 | 1297 | 485576 | 4078 | 60483 | 1798 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-SKCM | Skin Cutaneous Melanoma | 436 | 1880 | 1426 | 485576 | 4427 | 60483 | 2488 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-BLCA | Bladder | 447 | 1880 | 1361 | 485576 | 4483 | 60483 | 2751 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-LIHC | Liver | 463 | 1880 | 1336 | 485576 | 4023 | 60483 | 2017 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-STAD | Stomach | 499 | 1880 | 1397 | 485576 | 4196 | 60483 | 2354 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-LGG | Lower Grade Glioma | 533 | 1880 | 1287 | 485576 | 4193 | 60483 | 1560 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-COAD | Colon | 539 | 1880 | 1460 | 485576 | 4671 | 60483 | 1931 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-UCEC | Endometrioid | 588 | 1880 | 1414 | 485576 | 4424 | 60483 | 2849 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-HNSC | Head and Neck | 611 | 1880 | 1428 | 485576 | 4358 | 60483 | 2059 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-THCA | Thyroid | 614 | 1880 | 1369 | 485576 | 4160 | 60483 | 1432 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-PRAD | Prostate | 623 | 1880 | 1334 | 485576 | 4006 | 60483 | 1635 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-LAML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | 626 | 1880 | 1140 | 485576 | 4415 | 60483 | 1032 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-GBM | Glioblastoma | 649 | 1880 | 1023 | 485576 | 4076 | 60483 | 1206 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-LUAD | Lung Adenocarcinoma | 728 | 1880 | 1360 | 485576 | 4480 | 60483 | 2562 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-OV | Ovarian | 731 | 1880 | 1430 | 485576 | 4254 | 60483 | 2116 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-LUSC | Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 752 | 1880 | 1375 | 485576 | 4302 | 60483 | 2610 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-KIRC | Kidney Clear Cell Carcinoma | 979 | 1880 | 1333 | 485576 | 4399 | 60483 | 2274 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| TCGA-BRCA | Breast | 1260 | 1880 | 1418 | 485576 | 4195 | 60483 | 3671 | 487 | 472 | 18090 | 17253 |

| Cancer Type | Age (Mean ± SD) |

Gender (M/F) |

Race (White/Asian/Black/NA/ American Indian/Alaska) |

Stage (0/I/IA/IB/IC/II/IIA/IIB/IIC/III/ IIIA/IIIB/IIIC/IV/IVA/IVB/IVC/NA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA-ACC | 47.46 ± 16.20 | 33/62 | 79/3/1/12/0 | 0/9/0/0/0/46/0/0/0/20/0/0/0/17/0/0/0/3 |

| TCGA-BLCA | 67.92 ± 10.39 | 326/121 | 363/43/23/18/0 | 0/3/0/0/0/136/0/0/0/159/0/0/0/148/0/0/0/1 |

| TCGA-BRCA | 57.94 ± 13.11 | 13/1247 | 915/59/198/87/1 | 0/114/94/7/0/6/404/307/0/2/176/30/74/22/0/0/0/24 |

| TCGA-CESC | 48.04 ± 13.70 | 0/304 | 211/19/32/30/9 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/304 |

| TCGA-CHOL | 64.37 ± 12.21 | 30/32 | 55/3/3/1/0 | 0/30/0/0/0/16/0/0/0/5/0/0/0/2/3/6/0/0 |

| TCGA-COAD | 66.93 ± 12.67 | 288/251 | 261/11/67/198/2 | 0/87/1/0/0/46/150/13/2/26/9/69/47/56/18/3/0/12 |

| TCGA-DLBC | 56.76 ± 13.68 | 24/27 | 32/18/1/0/0 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/51 |

| TCGA-ESCA | 64.22 ± 12.11 | 208/41 | 162/46/6/35/0 | 0/14/9/7/0/1/56/43/0/41/16/10/9/7/6/0/0/30 |

| TCGA-GBM | 57.74 ± 14.32 | 399/250 | 547/13/53/36/0 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/649 |

| TCGA-HNSC | 61.02 ± 11.92 | 443/168 | 522/12/58/17/2 | 0/29/0/0/0/93/0/0/0/97/0/0/0/0/302/13/1/76 |

| TCGA-KICH | 51.61 ± 14.12 | 99/83 | 154/6/19/3/0 | 0/75/0/0/0/59/0/0/0/34/0/0/0/14/0/0/0/0 |

| TCGA-KIRC | 60.67 ± 11.95 | 641/338 | 876/16/73/14/0 | 0/475/0/0/0/102/0/0/0/237/0/0/0/161/0/0/0/4 |

| TCGA-KIRP | 61.98 ± 12.20 | 278/98 | 275/6/75/16/4 | 0/219/0/0/0/25/0/0/0/77/0/0/0/21/0/0/0/34 |

| TCGA-LAML | 54.82 ± 15.87 | 345/281 | 564/8/49/5/0 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/626 |

| TCGA-LGG | 42.71 ± 13.32 | 293/240 | 492/8/22/10/1 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/533 |

| TCGA-LIHC | 60.44 ± 13.71 | 305/158 | 255/168/25/14/1 | 0/211/0/0/0/105/0/0/0/6/78/12/11/2/1/3/0/34 |

| TCGA-LUAD | 65.20 ± 10.08 | 329/399 | 580/14/84/48/2 | 0/7/194/195/0/2/67/103/0/0/101/12/0/37/0/0/0/10 |

| TCGA-LUSC | 67.28 ± 8.62 | 548/204 | 530/12/47/163/0 | 0/4/127/243/0/4/87/138/0/3/94/33/0/12/0/0/0/7 |

| TCGA-MESO | 63.01 ± 9.78 | 70/16 | 84/1/1/0/0 | 0/7/2/1/0/15/0/0/0/45/0/0/0/16/0/0/0/0 |

| TCGA-OV | 59.60 ± 11.44 | 0/731 | 626/25/43/33/3 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/731 |

| TCGA-PAAD | 64.87 ± 11.36 | 123/99 | 195/13/8/6/0 | 0/1/6/15/0/0/36/148/0/6/0/0/0/7/0/0/0/3 |

| TCGA-PCPG | 47.02 ± 15.15 | 84/105 | 157/7/20/4/1 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/189 |

| TCGA-PRAD | 60.93 ± 6.80 | 623/0 | 510/13/81/18/1 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/623 |

| TCGA-READ | 63.83 ± 11.85 | 98/80 | 90/1/7/80/0 | 0/37/0/0/0/7/40/2/1/6/7/25/14/21/7/0/0/11 |

| TCGA-SARC | 60.70 ± 14.38 | 129/158 | 253/5/20/9/0 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/287 |

| TCGA-SKCM | 57.84 ± 15.41 | 289/174 | 441/12/1/9/0 | 6/30/18/30/0/39/18/28/61/44/16/46/68/23/0/0/0/36 |

| TCGA-STAD | 65.44 ± 10.53 | 320/179 | 311/108/15/64/0 | 0/1/21/46/0/37/54/71/0/4/88/67/39/47/0/0/0/24 |

| TCGA-TGCT | 31.87 ± 9.19 | 139/0 | 124/4/6/5/0 | 0/69/26/11/0/4/6/1/1/2/1/6/5/0/0/0/0/7 |

| TCGA-THCA | 47.17 ± 15.83 | 166/448 | 413/59/35/106/1 | 0/350/0/0/0/64/0/0/0/134/0/0/0/4/52/0/8/2 |

| TCGA-THYM | 58.12 ± 13.00 | 72/66 | 115/13/8/2/0 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/138 |

| TCGA-UCEC | 63.74 ± 11.06 | 0/588 | 402/21/120/32/4 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/588 |

| TCGA-UCS | 70.07 ± 9.24 | 0/61 | 50/1/9/1/0 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/0/61 |

| TCGA-UVM | 61.65 ± 13.95 | 45/35 | 55/0/0/25/0 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/12/27/0/0/25/10/1/4/0/0/0/1 |

| Moffitt-LSCC | 69.14 ± 8.34 | 72/36 | 105/0/3/0/0 | 0/0/24/25/0/0/31/15/0/0/12/1/0/0/0/0/0/0 |

| Cancer Type | C-Index {Test, Ensemble} |

Cancer Type | C-Index {Test, Ensemble} |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA-PCPG | {0.900, 0.929} | TCGA-DLBC | {0.714, 0.619} |

| TCGA-ACC | {0.866, 0.861} | TCGA-MESO | {0.599, 0.615} |

| TCGA-UVM | {0.822, 0.829} | TCGA-LUSC | {0.588, 0.592} |

| TCGA-LGG | {0.821, 0.823} | TCGA-PAAD | {0.597, 0.598} |

| TCGA-KICH | {0.801, 0.807} | TCGA-HNSC | {0.583, 0.583} |

| TCGA-KIRC | {0.777, 0.776} | TCGA-CHOL | {0.574, 0.574} |

| TCGA-KIRP | {0.775, 0.778} | TCGA-COAD | {0.546, 0.542} |

| TCGA-UCEC | {0.708, 0.713} | TCGA-THYM | {0.555, 0.571} |

| TCGA-THCA | {0.696, 0.698} | TCGA-UCS | {0.514, 0.541} |

| TCGA-SKCM | {0.691, 0.689} | TCGA-OV | {0.518, 0.509} |

| TCGA-BRCA | {0.687, 0.692} | TCGA-READ | {0.550, 0.551} |

| TCGA-CESC | {0.676, 0.682} | TCGA-GBM | {0.495, 0.493}* |

| TCGA-ESCA | {0.650, 0.648} | TCGA-GBM (finetuning) | {0.642, 0.650} |

| TCGA-LUAD | {0.647, 0.653} | TCGA-LAML | {0.482, 0.485}* |

| TCGA-SARC | {0.650, 0.658} | TCGA-LAML (finetuning) | {0.627, 0.626} |

| TCGA-STAD | {0.631, 0.628} | TCGA-PRAD | {0.304, 0.300}* |

| TCGA-LIHC | {0.627, 0.629} | TCGA-PRAD (finetuning) | {0.541, 0.542}* |

| TCGA-BLCA | {0.609, 0.609} | TCGA-TGCT | {0.123, 0.091}* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).