Submitted:

11 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have demonstrated significantly improved clinical efficacy in a minority of patients with advanced melanoma, whereas non-responders potentially suffer from severe side effects and delays in other treatment options. Predicting the response to anti-PD1 treatment in melanoma remains a challenge because the current FDA-approved gold standard, the nonsynonymous tumor mutation burden (nsTMB), offers limited accuracy. Methods: In this study, we developed a multi-omics-based machine learning model that integrates genomic and transcriptomic biomarkers to predict the response to anti-PD1 treatment in patients with advanced melanoma. We employed least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression with 49 biomarkers extracted from tumor-normal whole-exome and RNA sequencing as input features. The performance of the multi-omics AI model was thoroughly compared to that of nsTMB alone, and to models that use only genomic or transcriptomic biomarkers. Results: We used publicly available DNA and RNA-seq datasets of melanoma patients for the training and validation of our model, forming a meta-cohort of 449 patients for which the outcome was recorded as RECIST score. The model substantially improved the prediction of anti-PD1 outcomes compared to nsTMB alone. Using SHAP values, we demonstrated the explainability of the model’s predictions on a per-sample basis. Conclusion: We demonstrated that models using only RNA-seq or multi-omics biomarkers outperformed nsTMB in predicting the response of melanoma patients to ICI. Furthermore, our AI improves clinical usability by providing explanations of its predictions on a per-patient basis. Our findings underscore the utility of multi-omics data for selecting patients for treatment with anti-PD1 drugs. However, to train clinical-grade AI models for routine applications, prospective studies collecting larger melanoma cohorts with consistent application of exome and RNA sequencing are required.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

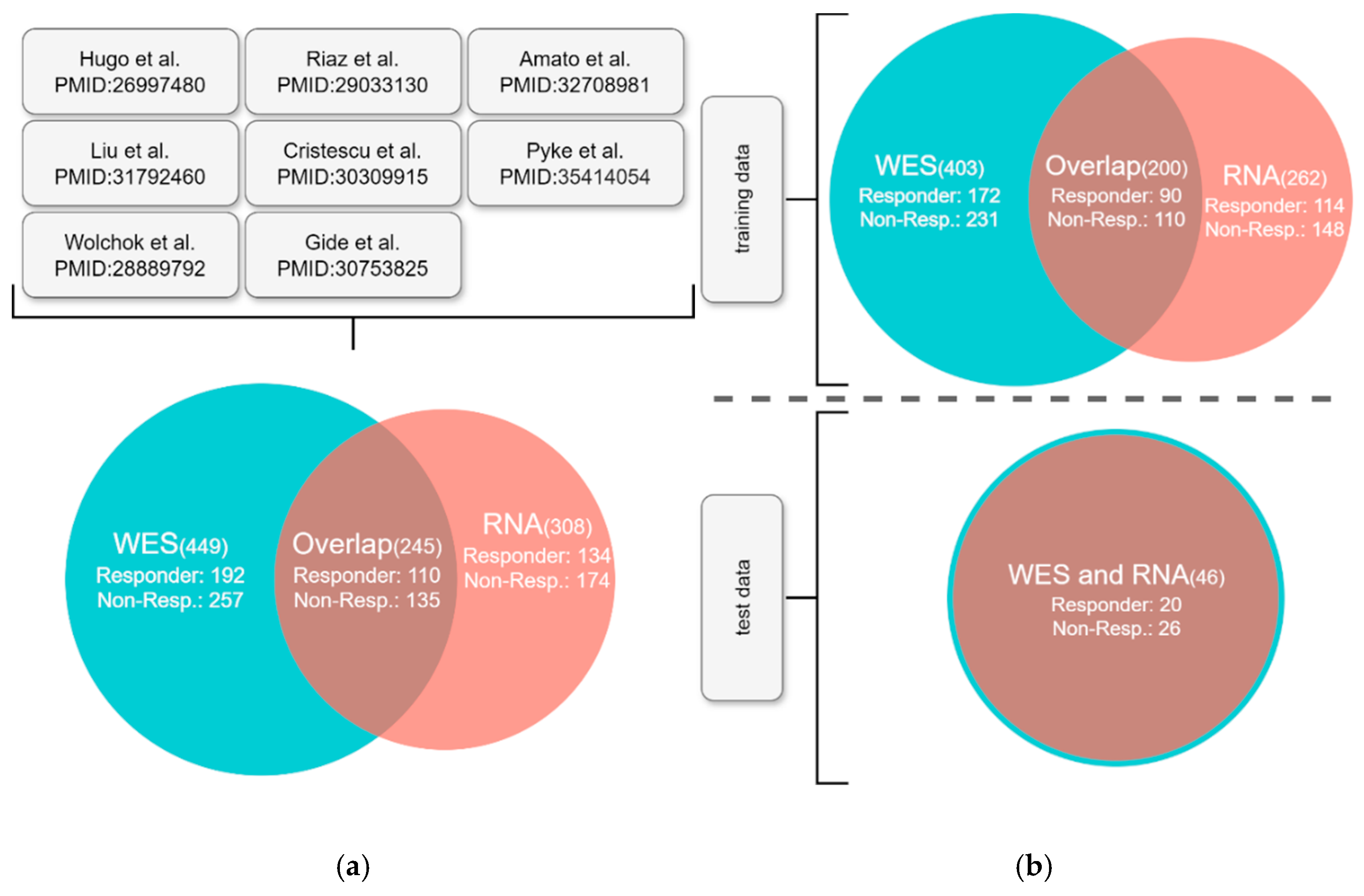

Patient Collective

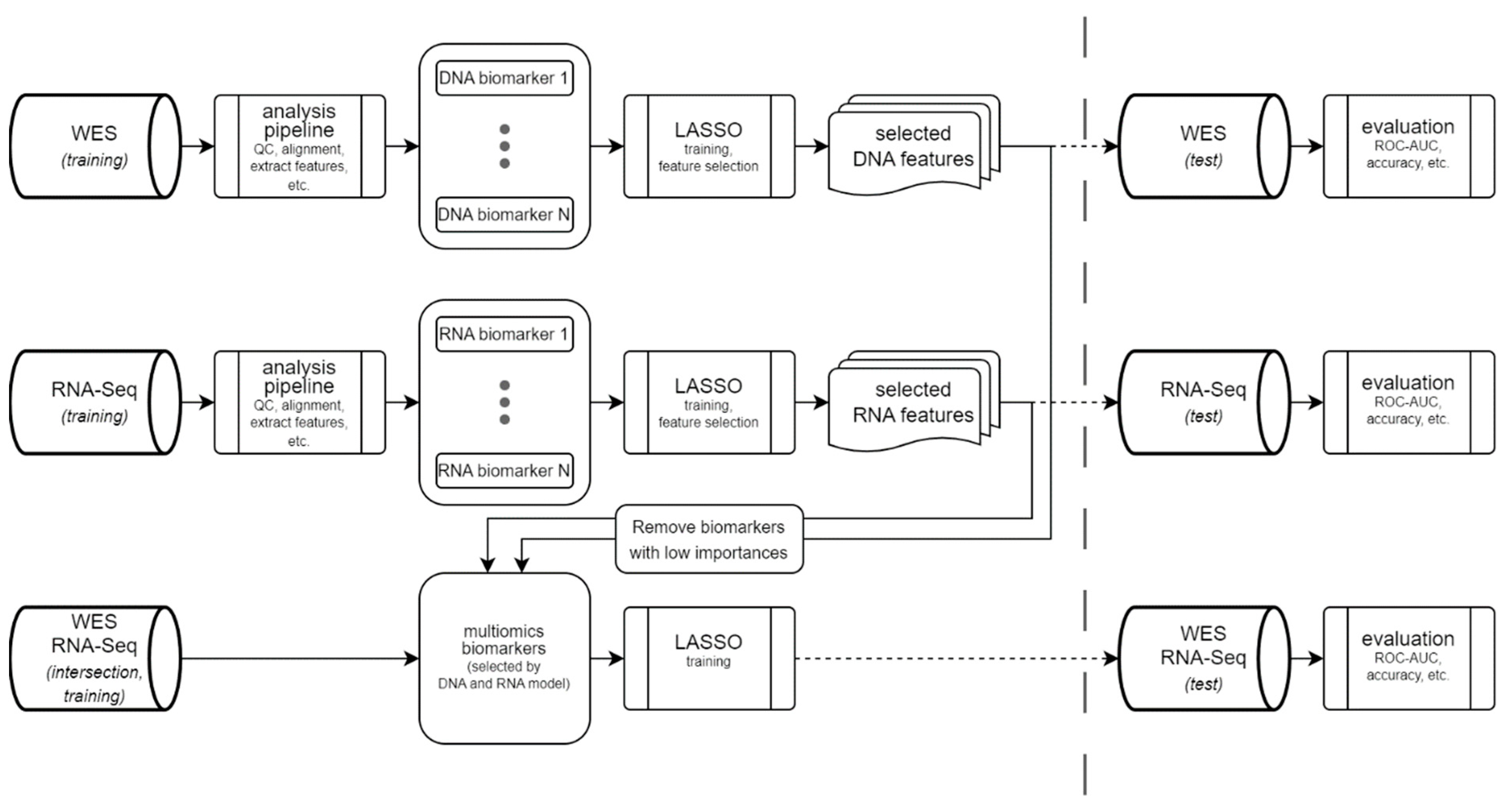

Machine Learning Model

- Somatic features: BRAF:V600E status, tumor purity, nsTMB, insertion and deletion (indel) burden, frameshift indel (fsIndel) burden, in-frame indel burden, splice burden, missense burden, synonymous burden, multiple amino acid burden, frameshift mutation proportion, nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution ratio (dN/dS ratio), copy number variant (CNV) burden, deletion burden, neoantigen burden, maximum neoantigen-binding affinity, mean differential agretopicity index (DAI), median DAI, maximum DAI, upper decile DAI, maximum recognition potential, maximum HEX alignment score, and maximum dissimilarity score.

- Germline features: mean HLA evolutionary divergence (HED), HLA-B27 supertype, HLA-B44 supertype, HLA-B62 supertype, homozygous HLA-B, and homozygous HLA-C.

- Mechanisms of ICI resistance (enriched in non-responders): alterations in B2M, alterations in TP53, alterations in STK11, alterations in PTEN, alterations in KRAS, alterations in MDM2, alterations in MDM4, and alterations in EGFR.

- Mechanisms of ICI response (enriched in responders) were sparse in the training dataset and merged into one biomarker: alterations in JAK1/JAK2, deletions at chr6p21.3 (this locus contains HLA class I-related genes), alterations in CTNNB1

Bioinformatics Pipeline

Basic Analysis Pipeline

Target Regions

Quality Control

Results

AI Model for prediction of Anti-PD1 Response

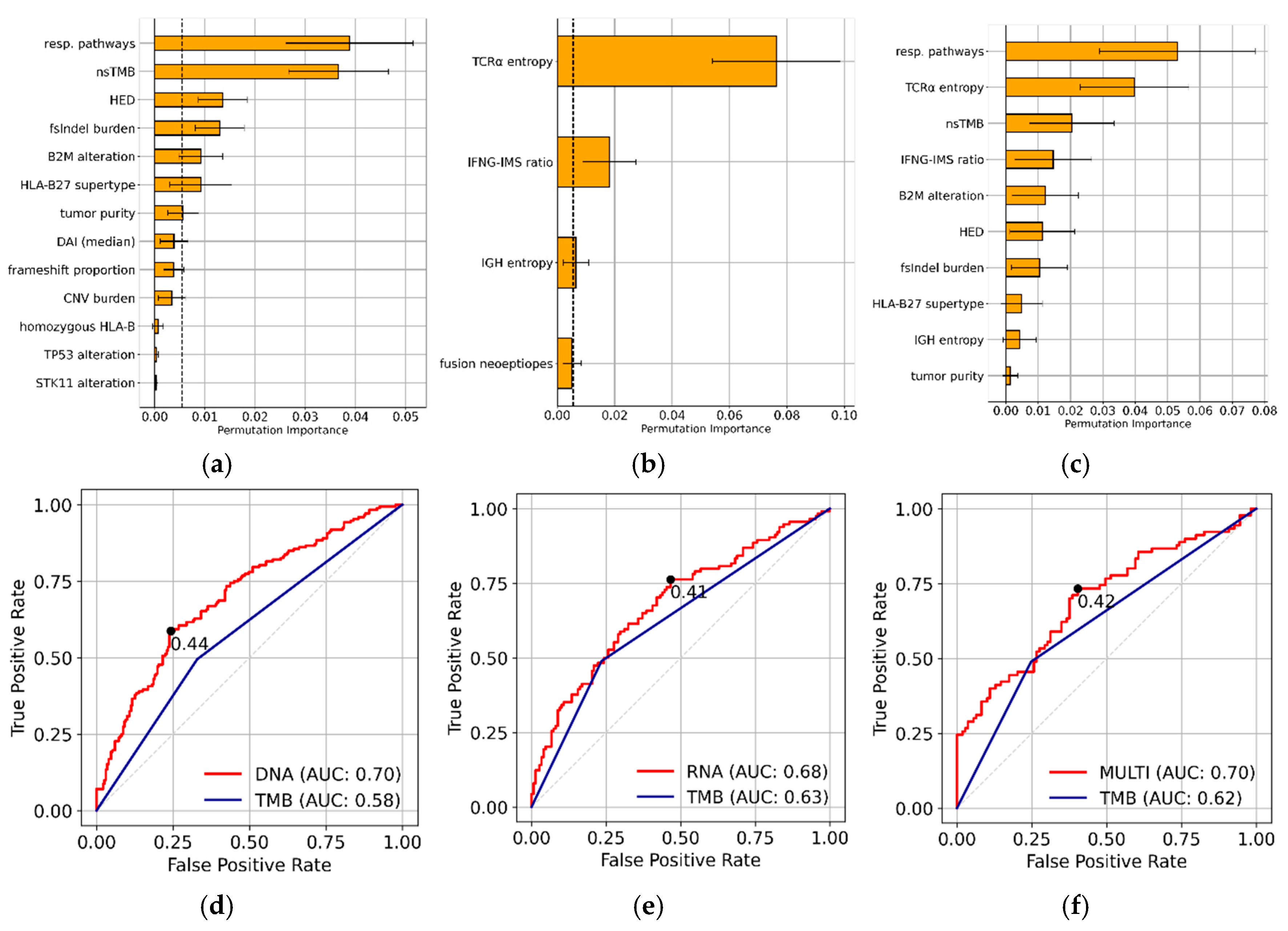

Feature Selection and Feature Importance

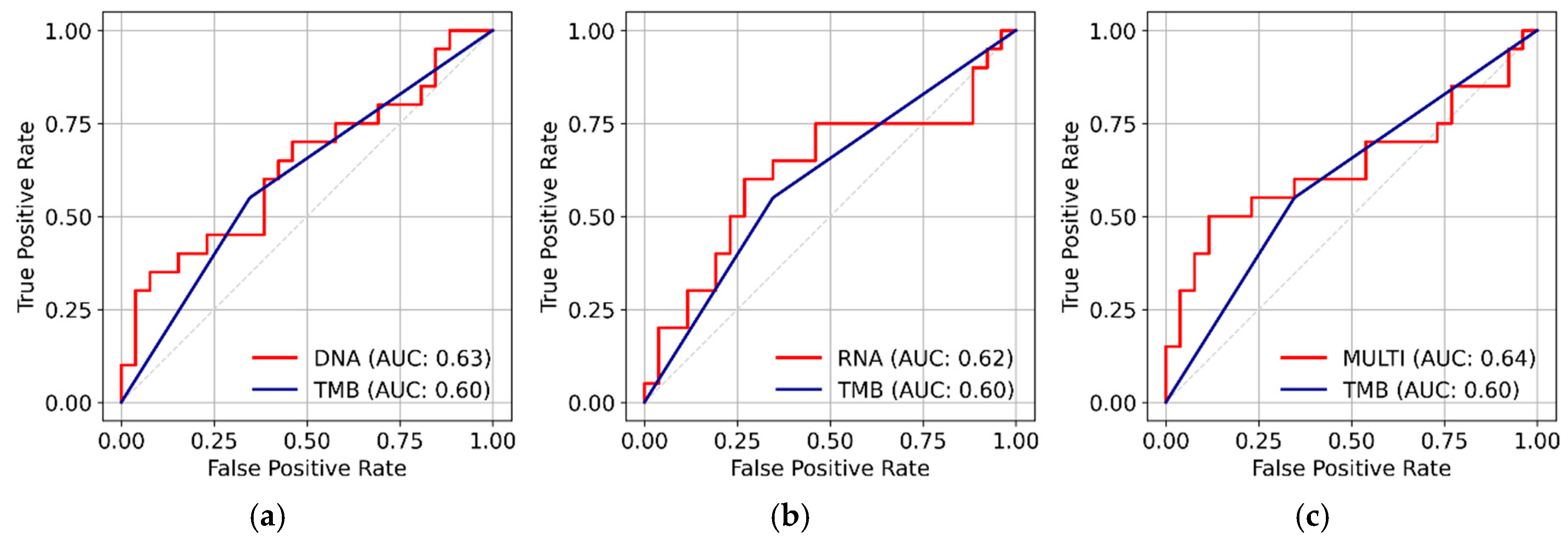

Model Performance on Training and Test Set

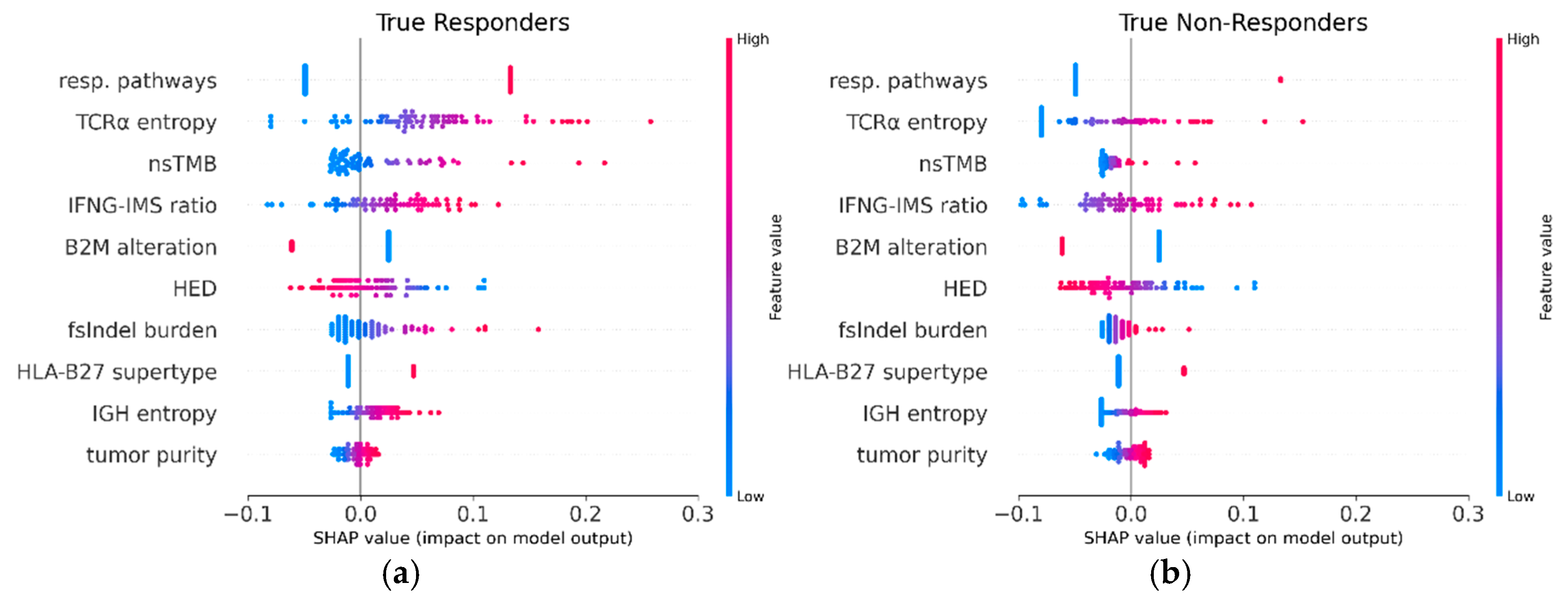

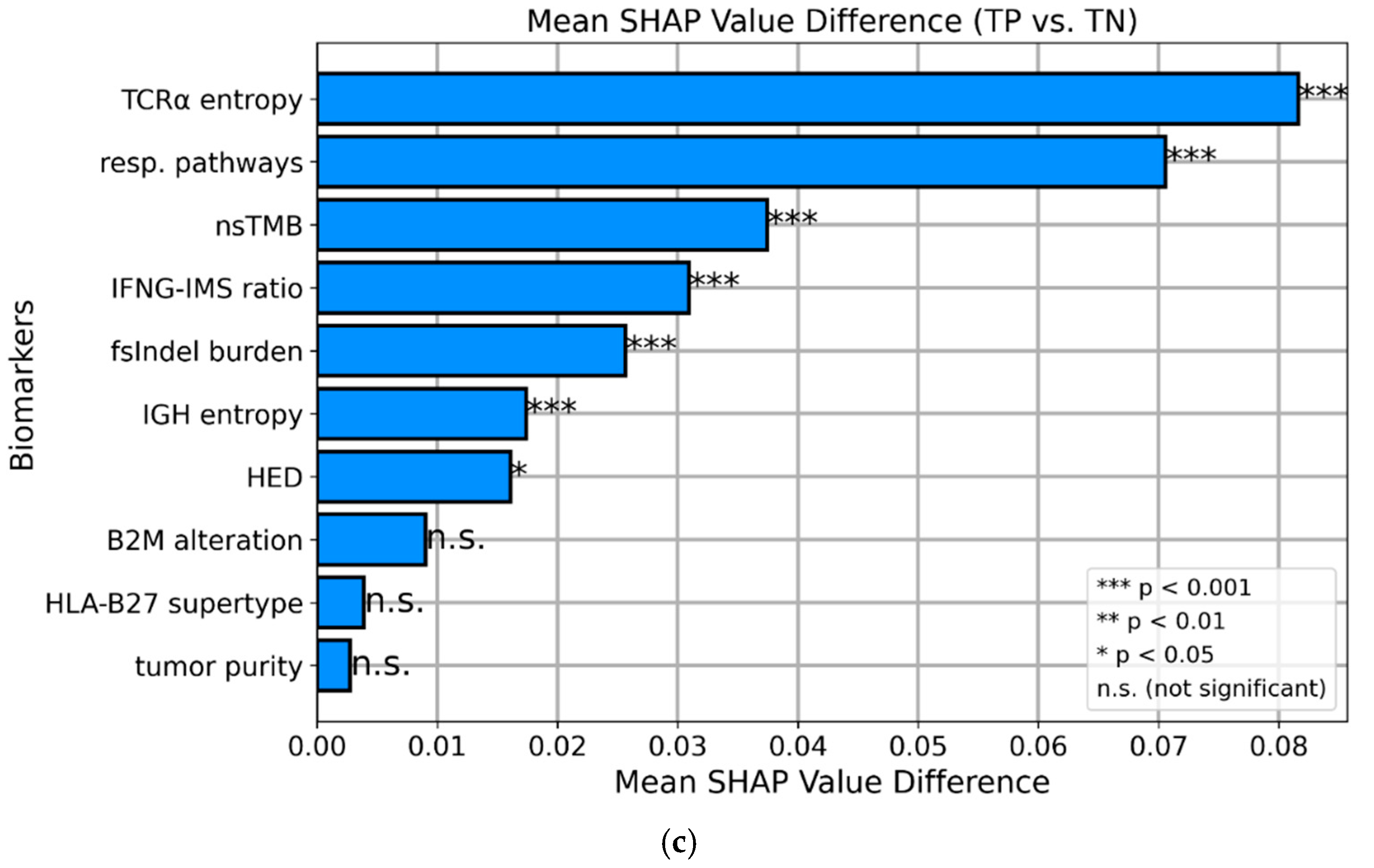

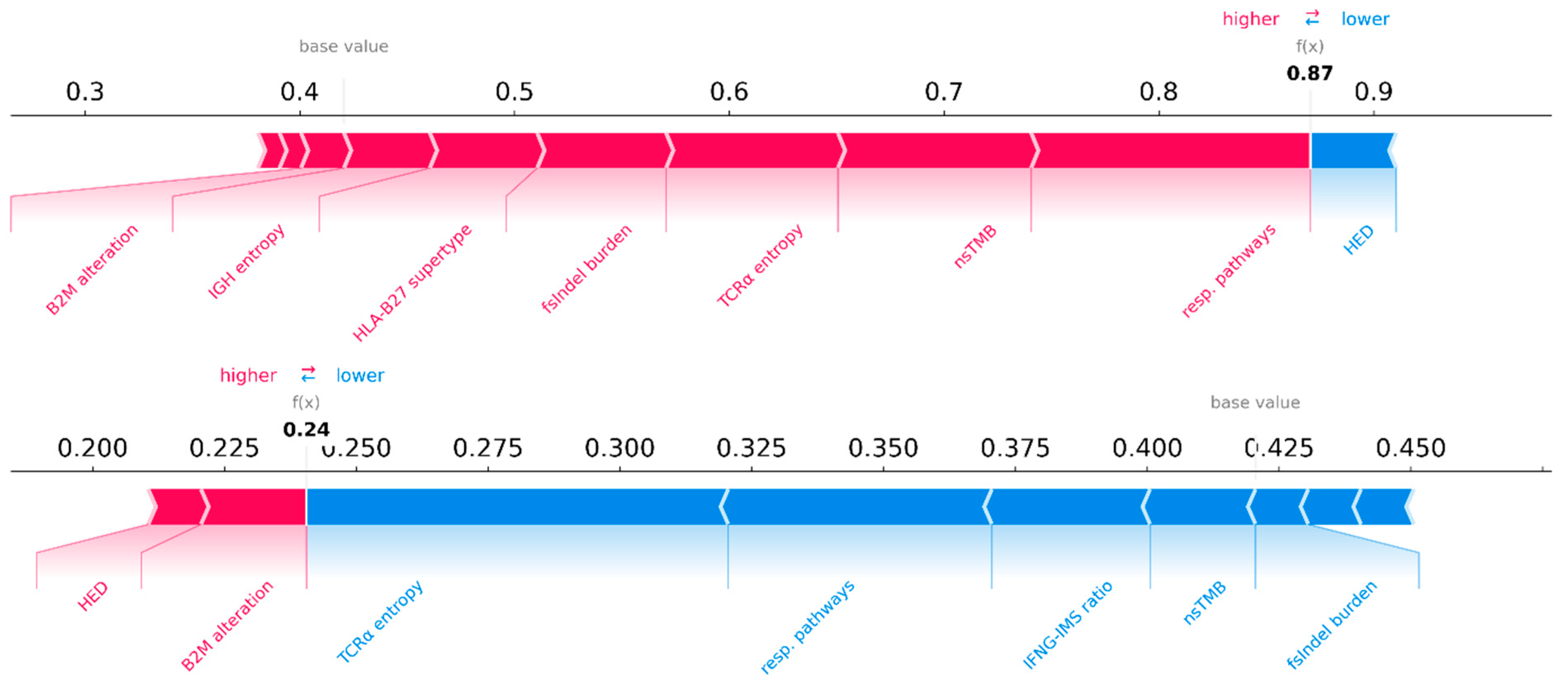

SHAP values

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statement

Appendix A

DNA Biomarkers

Tumor Mutational Burden and Related Mutation Count Metrics

Neoantigen and Neoepitope Analysis

- HEX alignment score: This score describes the similarity of tumor peptides to known viral-derived peptides[48]. High scores reflect a high similarity of the neopeptide with viral pathogens, and could be more likely recognized by the immune system. We used the maximum HEX score in the sample as a biomarker.

- Recognition potential: A fitness model that uses binding affinities and sequence similarity of neoantigens to known pathogens of human infectious diseases to estimate the likelihood of a neoantigen interacting with the immune system[49]. Its maximum value was used as a biomarker for our model.

- Dissimilarity score: This score compares the mutated peptide to the non-mutated self-proteome[50]. Neopeptides with higher dissimilarity scores are more likely to be recognized by the immune system. Therefore, we used the maximum dissimilarity score as the biomarker.

Resistance Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Description | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Defects at the HLA locus* | Any deletion or LOH event that overlaps chr6p21.3, chr6:29941259-33314212. This locus contains the majority of HLA class I-related genes. | [51] |

| Defects in B2M | B2M is an integral part of both MHC class I and II complexes. Dysfunctional B2M proteins lead to the formation of dysfunctional MHC complexes. However, the loss of both functional alleles is uncommon since such cancer clones are eradicated by NK cells. Hence, we counted heterozygous deletions, LOH events, mutations with a high VEP effect, or COSMIC tiers 1, 2, and 3 as defects in B2M. | [53] |

| JAK1/JAK2 alteration* | Homozygous deletions, VEP-high or CMC tier 1,2, and 3 somatic variants of JAK1 and JAK2. Other genes of the JAK-STAT pathway were not included because JAK3 is not expressed in solid tissue and alterations in most STAT genes are difficult to interpret because STATs are at the same time both TSG and oncogenes. | [54] |

| CTNNB1 pathway alteration* | CTNNB1 is an oncogene. Its pathway includes the negative regulators APC, AXIN1, and HNF1A, which are present in our intersecting target region. Thus, we counted the COSMIC tier 1, 2, and 3 mutations of CTNNB1. For its negative regulators, which act as TSG, we considered any somatic mutation with a high VEP effect or COSMIC tiers 1,2, and 3 as well as homozygous deletions. | [55] |

| TP53 alteration | TP53 is frequently mutated in many tumors. Defects in this TSG have manifold effects on cancer cells, including immunosuppression and evasion. Thus, we considered any deletion, LOH, mutation with a high VEP effect or COSMIC tiers 1,2, and 3 in TP53. | [56] |

| PTEN alteration | Deleterious events in the TSG PTEN were described as a resistance mechanism previously. Thus, we considered any deletion, LOH, mutations with a high VEP effect or COSMIC tiers 1, 2, and 3 in PTEN as deleterious. | [57,58] |

| STK11 alteration | STK11 is a tumor suppressor gene. It was predictive of anti-PD1 resistance in a study on another cancer entity. Hence, we counted any deletions, mutations with a high VEP effect or COSMIC tiers 1,2, and 3 in STK11. | [59] |

| KRAS alteration | KRAS is an oncogene. The predictive potential of KRAS mutations in anti-PD1 treatment has been previously described in another cancer entity. Thus, we considered any amplification ≥ 4 and mutations with COSMIC tiers 1, 2, and 3 in KRAS deleterious. | [60] |

| MDM2 alteration | MDM2 is an oncogene. Activating mutations led to the hyperprogression of melanoma in a previous study. Thus, we counted any amplification ≥ 4 and COSMIC tiers 1, 2, and 3 in MDM2 as resistance mechanisms. | [61] |

| MDM4 alteration | MDM4 is an oncogene. Activating mutations led to the hyperprogression of melanoma in a previous study. Thus, we counted any amplification ≥ 4 and COSMIC tiers 1, 2, and 3 in MDM4 as resistance mechanisms. | [61] |

| EGFR alteration | EGFR is an oncogene. Activating mutations led to the hyperprogression of melanoma in a previous study. Thus, we counted any amplification ≥ 4 and COSMIC tiers 1, 2, and 3 in EGFR as resistance mechanisms. | [61] |

Tumor Purity and Heterogeneity

CNV Burden

RNA Biomarkers

TCR and BCR Repertoires

Immune Cell Infiltration

IFNG-IMS Ratio

Gene Expression Profiles

References

- Hodi, F.S.; O'Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved Survival with Ipilimumab in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 363, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, A.; Hazarika, M.; Theoret, M.R.; Mishra-Kalyani, P.; Chen, H.; He, K.; Sridhara, R.; Subramaniam, S.; Pfuma, E.; Wang, Y.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2017, 23, 5661–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazarika, M.; Chuk, M.K.; Theoret, M.R.; Mushti, S.; He, K.; Weis, S.L.; Putman, A.H.; Helms, W.S.; Cao, X.; Li, H.; et al. U.S. FDA Approval Summary: Nivolumab for Treatment of Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma Following Progression on Ipilimumab. Clinical Cancer Research 2017, 23, 3484–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, C.; Lee, M.; Hoen, D.; Zehir, A.; Berger, M.F.; Seshan, V.E.; Chan, T.A.; Morris, L.G.T. Response Rates to Anti–PD-1 Immunotherapy in Microsatellite-Stable Solid Tumors With 10 or More Mutations per Megabase. JAMA Oncology 2021, 7, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, L.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.A.; Donoghue, M.; Yuan, M.; Rodriguez, L.; Gallagher, P.S.; Philip, R.; Ghosh, S.; Theoret, M.R.; Beaver, J.A.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Tumor Mutational Burden–High Solid Tumors. Clinical Cancer Research 2021, 27, 4685–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marabelle, A.; Fakih, M.; Lopez, J.; Shah, M.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Chung, H.C.; Kindler, H.L.; Lopez-Martin, J.A.; Miller, W.H.; et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. The Lancet Oncology 2020, 21, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Sofiya, L.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Lamine, F.; Maillard, M.; Fraga, M.; Shabafrouz, K.; Ribi, C.; Cairoli, A.; Guex-Crosier, Y.; et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2019, 16, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltussen, J.C.; Welters, M.J.P.; Verdegaal, E.M.E.; Kapiteijn, E.; Schrader, A.M.R.; Slingerland, M.; Liefers, G.-J.; van der Burg, S.H.; Portielje, J.E.A.; de Glas, N.A. Predictive Biomarkers for Outcomes of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs) in Melanoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; McCue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nature methods 2008, 5, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.B.; Turner, E.H.; Robertson, P.D.; Flygare, S.D.; Bigham, A.W.; Lee, C.; Shaffer, T.; Wong, M.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Eichler, E.E. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature 2009, 461, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). European Journal of Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, K.; Shutov, O.; Lapoint, R.; Kimelman, M.; Brister, J. R.; O’Sullivan, C. The Sequence Read Archive: a decade more of explosive growth. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 50, D387–D390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryka, K.A.; Hao, L.; Sturcke, A.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ziyabari, L.; Lee, M.; Popova, N.; Sharopova, N.; Kimura, M. NCBI’s Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes: dbGaP. Nucleic acids research 2014, 42, D975–D979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, C.M.; Hintzsche, J.D.; Wells, K.; Applegate, A.; Gorden, N.T.; Vorwald, V.M.; Tobin, R.P.; Nassar, K.; Shellman, Y.G.; Kim, J.; et al. Pre-Treatment Mutational and Transcriptomic Landscape of Responding Metastatic Melanoma Patients to Anti-PD1 Immunotherapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1943–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, R.; Mogg, R.; Ayers, M.; Albright, A.; Murphy, E.; Yearley, J.; Sher, X.; Liu, X.Q.; Lu, H.; Nebozhyn, M.; et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gide, T.N.; Quek, C.; Menzies, A.M.; Tasker, A.T.; Shang, P.; Holst, J.; Madore, J.; Lim, S.Y.; Velickovic, R.; Wongchenko, M.; et al. Distinct Immune Cell Populations Define Response to Anti-PD-1 Monotherapy and Anti-PD-1/Anti-CTLA-4 Combined Therapy. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 238–255.e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugo, W.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Sun, L.; Song, C.; Moreno, B.H.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Berent-Maoz, B.; Pang, J.; Chmielowski, B.; Cherry, G.; et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Features of Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma. Cell 2016, 165, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Schilling, B.; Liu, D.; Sucker, A.; Livingstone, E.; Jerby-Arnon, L.; Zimmer, L.; Gutzmer, R.; Satzger, I.; Loquai, C.; et al. Integrative molecular and clinical modeling of clinical outcomes to PD1 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 1916–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, R.M.; Mellacheruvu, D.; Dea, S.; Abbott, C.W.; McDaniel, L.; Bhave, D.P.; Zhang, S.V.; Levy, E.; Bartha, G.; West, J.; et al. A machine learning algorithm with subclonal sensitivity reveals widespread pan-cancer human leukocyte antigen loss of heterozygosity. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 1925–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, N.; Havel, J.J.; Makarov, V.; Desrichard, A.; Urba, W.J.; Sims, J.S.; Hodi, F.S.; Martín-Algarra, S.; Mandal, R.; Sharfman, W.H.; et al. Tumor and Microenvironment Evolution during Immunotherapy with Nivolumab. Cell 2017, 171, 934–949.e916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Rutkowski, P.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Wagstaff, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Ferrucci, P.F.; et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Camblor, P.; Pardo-Fernández, J.C. The Youden Index in the Generalized Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Context. The International Journal of Biostatistics 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Scheffler, K.; Halpern, A.L.; Bekritsky, M.A.; Noh, E.; Källberg, M.; Chen, X.; Kim, Y.; Beyter, D.; Krusche, P.; et al. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nature Methods 2018, 15, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidov, G.; Ossowski, S. ClinCNV: novel method for allele-specific somatic copy-number alterations detection. bioRxiv 2019, 837971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.G.; Bamford, S.; Jubb, H.C.; Sondka, Z.; Beare, D.M.; Bindal, N.; Boutselakis, H.; Cole, C.G.; Creatore, C.; Dawson, E.; et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 47, D941–D947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S.E.; Riat, H.S.; Ritchie, G.R.S.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biology 2016, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, J.J. The prediction of HLA genotypes from next generation sequencing and genome scan data. Dissertation, Boston University, Boston, 2014.

- Florou, V.; Floudas, C.S.; Maoz, A.; Naqash, A.R.; Norton, C.; Tan, A.C.; Sokol, E.S.; Frampton, G.; Soares, H.P.; Puri, S.; et al. Real-world pan-cancer landscape of frameshift mutations and their role in predicting responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancers with low tumor mutational burden. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2023, 11, e007440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Michelakos, T.; Yamada, T.; Fan, S.; Wang, X.; Schwab, J.H.; Ferrone, C.R.; Ferrone, S. Defective HLA class I antigen processing machinery in cancer. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2018, 67, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; Chan, V.; Fearon, D.F.; Merad, M.; Coussens, L.M.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Hedrick, C.C.; et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nature Medicine 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, D.H.; Bronte, V. Immune suppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment. Current Opinion in Immunology 2016, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.A.; Thomas, A.M.; Bolte, L.A.; Björk, J.R.; de Ruijter, L.K.; Armanini, F.; Asnicar, F.; Blanco-Miguez, A.; Board, R.; Calbet-Llopart, N.; et al. Cross-cohort gut microbiome associations with immune checkpoint inhibitor response in advanced melanoma. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saal, J.; Ellinger, J.; Ritter, M.; Brossart, P.; Hölzel, M.; Klümper, N.; Bald, T. Pretreatment albumin is a prognostic and predictive biomarker for response to atezolizumab across solid tumors. Clinical & Translational Immunology 2023, 12, e1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhelwa, A.Y.; Kichenadasse, G.; McKinnon, R.A.; Rowland, A.; Hopkins, A.M.; Sorich, M.J. Machine Learning for Prediction of Survival Outcomes with Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors in Urothelial Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilickap, S.; Demirci, U.; Karadurmus, N.; Dogan, M.; Akinci, B.; Sendur, M.A.N. Endpoints in oncology clinical trials. J buon 2018, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sena, L.A.; Fountain, J.; Isaacsson Velho, P.; Lim, S.J.; Wang, H.; Nizialek, E.; Rathi, N.; Nussenzveig, R.; Maughan, B.L.; Velez, M.G.; et al. Tumor Frameshift Mutation Proportion Predicts Response to Immunotherapy in Mismatch Repair-Deficient Prostate Cancer. The Oncologist 2020, 26, e270–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincorena, I.; Raine, K.M.; Gerstung, M.; Dawson, K.J.; Haase, K.; Van Loo, P.; Davies, H.; Stratton, M.R.; Campbell, P.J. Universal Patterns of Selection in Cancer and Somatic Tissues. Cell 2017, 171, 1029–1041.e1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundal, J.; Kiwala, S.; McMichael, J.; Miller, C.A.; Xia, H.; Wollam, A.T.; Liu, C.J.; Zhao, S.; Feng, Y.-Y.; Graubert, A.P.; et al. pVACtools: A Computational Toolkit to Identify and Visualize Cancer Neoantigens. Cancer Immunology Research 2020, 8, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trolle, T.; McMurtrey, C.P.; Sidney, J.; Bardet, W.; Osborn, S.C.; Kaever, T.; Sette, A.; Hildebrand, W.H.; Nielsen, M.; Peters, B. The Length Distribution of Class I–Restricted T Cell Epitopes Is Determined by Both Peptide Supply and MHC Allele–Specific Binding Preference. The Journal of Immunology 2016, 196, 1480–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, F.; Duitama, J.; Al Seesi, S.; Ayres, C.M.; Corcelli, S.A.; Pawashe, A.P.; Blanchard, T.; McMahon, D.; Sidney, J.; Sette, A.; et al. Genomic and bioinformatic profiling of mutational neoepitopes reveals new rules to predict anticancer immunogenicity. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2014, 211, 2231–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorani, E.; Rosenthal, R.; McGranahan, N.; Reading, J.L.; Lynch, M.; Peggs, K.S.; Swanton, C.; Quezada, S.A. Differential binding affinity of mutated peptides for MHC class I is a predictor of survival in advanced lung cancer and melanoma. Annals of Oncology 2018, 29, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, F.; Riesgo-Ferreiro, P.; Löwer, M.; Sahin, U.; Schrörs, B. NeoFox: annotating neoantigen candidates with neoantigen features. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 4246–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaro, J.; Kasanen, H.H.E.; Whalley, T.; Capasso, C.; Grönholm, M.; Feola, S.; Peltonen, K.; Hamdan, F.; Hernberg, M.; Mäkelä, S.; et al. Viral Molecular Mimicry Influences the Antitumor Immune Response in Murine and Human Melanoma. Cancer Immunology Research 2021, 9, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuksza, M.; Riaz, N.; Makarov, V.; Balachandran, V.P.; Hellmann, M.D.; Solovyov, A.; Rizvi, N.A.; Merghoub, T.; Levine, A.J.; Chan, T.A.; et al. A neoantigen fitness model predicts tumour response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Nature 2017, 551, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richman, L.P.; Vonderheide, R.H.; Rech, A.J. Neoantigen Dissimilarity to the Self-Proteome Predicts Immunogenicity and Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cell Systems 2019, 9, 375–382.e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggs, L.; Sadagopan, A.; Moghaddam, A.S.; Ferrone, S. HLA class I antigen processing machinery defects in antitumor immunity and immunotherapy. Trends in Cancer 2021, 7, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carapito, R.; Radosavljevic, M.; Bahram, S. Next-Generation Sequencing of the HLA locus: Methods and impacts on HLA typing, population genetics and disease association studies. Human Immunology 2016, 77, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, B.; Wei, J. Beta2-microglobulin(B2M) in cancer immunotherapies: Biological function, resistance and remedy. Cancer Letters 2021, 517, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.S.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Escuin-Ordinas, H.; Garcia-Diaz, A.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Kalbasi, A.; Grasso, C.S.; Hugo, W.; Sandoval, S.; Torrejon, D.Y.; et al. Primary Resistance to PD-1 Blockade Mediated by JAK1/2 Mutations. Cancer Discov 2017, 7, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Bao, R.; Gajewski, T.F. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2015, 523, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, T.; Jiang, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, R. p53 mutation and deletion contribute to tumor immune evasion. Frontiers in Genetics 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, G.; Carbone, C.; Carbognin, L.; Pilotto, S.; Ciccarese, C.; Iacovelli, R.; Milella, M.; Bria, E.; Tortora, G. Revising PTEN in the Era of Immunotherapy: New Perspectives for an Old Story. Cancers 2019, 11, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, W.; Chen, P.-L.; Reuben, A.; Spencer, C.N.; Prieto, P.A.; Miller, J.P.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Wang, F.; Cooper, Z.A.; Reddy, S.M.; et al. Integrated molecular analysis of tumor biopsies on sequential CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade reveals markers of response and resistance. Science Translational Medicine 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pore, N.; Wu, S.; Standifer, N.; Jure-Kunkel, M.; de los Reyes, M.; Shrestha, Y.; Halpin, R.; Rothstein, R.; Mulgrew, K.; Blackmore, S.; et al. Resistance to Durvalumab and Durvalumab plus Tremelimumab Is Associated with Functional STK11 Mutations in Patients with Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer and Is Reversed by STAT3 Knockdown. Cancer Discovery 2021, 11, 2828–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.-Y.; Zhong, W.-Z.; Zhang, X.-C.; Su, J.; Xie, Z.; Liu, S.-Y.; Tu, H.-Y.; Chen, H.-J.; Sun, Y.-L.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Potential Predictive Value of TP53 and KRAS Mutation Status for Response to PD-1 Blockade Immunotherapy in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2017, 23, 3012–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forschner, A.; Hilke, F.J.; Bonzheim, I.; Gschwind, A.; Demidov, G.; Amaral, T.; Ossowski, S.; Riess, O.; Schroeder, C.; Martus, P.; et al. MDM2, MDM4 and EGFR Amplifications and Hyperprogression in Metastatic Acral and Mucosal Melanoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 540–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowell, D.; Morris, L.G.T.; Grigg, C.M.; Weber, J.K.; Samstein, R.M.; Makarov, V.; Kuo, F.; Kendall, S.M.; Requena, D.; Riaz, N.; et al. Patient HLA class I genotype influences cancer response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Science 2018, 359, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierini, F.; Lenz, T.L. Divergent Allele Advantage at Human MHC Genes: Signatures of Past and Ongoing Selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowell, D.; Krishna, C.; Pierini, F.; Makarov, V.; Rizvi, N.A.; Kuo, F.; Morris, L.G.T.; Riaz, N.; Lenz, T.L.; Chan, T.A. Evolutionary divergence of HLA class I genotype impacts efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oey, O.; Khattak, M.A.; Abed, A.; Meniawy, T.; Reid, A.; Calapre, L.; Millward, M.; Gray, E. Patient human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotype may predict response to anti-programmed death receptor 1 (anti-PD1) in advanced melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2021, 39, e21512–e21512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Song, Z.; Huang, L.; Guo, Z.; Tong, B.; Sun, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G. Tumor purity as a prognosis and immunotherapy relevant feature in cervical cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2021, 13, 24768–24785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Cohen, D.; Ouyang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.S. TRUST4: immune repertoire reconstruction from bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data. Nature Methods 2021, 18, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finotello, F.; Mayer, C.; Plattner, C.; Laschober, G.; Rieder, D.; Hackl, H.; Krogsdam, A.; Loncova, Z.; Posch, W.; Wilflingseder, D.; et al. Molecular and pharmacological modulators of the tumor immune contexture revealed by deconvolution of RNA-seq data. Genome Medicine 2019, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, G.; Finotello, F.; Petitprez, F.; Zhang, J.D.; Baumbach, J.; Fridman, W.H.; List, M.; Aneichyk, T. Comprehensive evaluation of transcriptome-based cell-type quantification methods for immuno-oncology. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, i436–i445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.; Xu, C.; Yang, W.; Chi, Z.; Sheng, X.; Si, L.; Xie, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, R.; et al. Ratio of the interferon-γ signature to the immunosuppression signature predicts anti-PD-1 therapy response in melanoma. npj Genomic Medicine 2021, 6, 7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayers, M.; Lunceford, J.; Nebozhyn, M.; Murphy, E.; Loboda, A.; Kaufman, D.R.; Albright, A.; Cheng, J.D.; Kang, S.P.; Shankaran, V.; et al. IFN-γ–related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017, 127, 2930–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shklovskaya, E.; Lee, J.H.; Lim, S.Y.; Stewart, A.; Pedersen, B.; Ferguson, P.; Saw, R.P.; Thompson, J.F.; Shivalingam, B.; Carlino, M.S.; et al. Tumor MHC Expression Guides First-Line Immunotherapy Selection in Melanoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L.; Hang, H.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, X. B2M gene expression shapes the immune landscape of lung adenocarcinoma and determines the response to immunotherapy. Immunology 2021, 164, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).