1. Introduction

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have seen widespread adoption in the civilian, commercial and military sectors due to their ability to operate autonomously or remotely in complex and often hazardous environments. Applications range from surveillance and disaster response to infrastructure inspection and logistics support [

1]. As the operational scope of UAVs expands, so does the demand for reliable, cost-effective, and proactive maintenance solutions that can ensure flight safety and extend the useful life of the system [

2,

3].

Structural failures in UAVs can occur due to cyclic mechanical stress, environmental conditions, or wear and tear over time. If undetected, these faults may lead to catastrophic failures. Traditionally, visual inspection techniques have been employed to assess structural health; however, such methods are time-consuming, operator-dependent, and often inadequate for early-stage fault detection [

4]. Consequently, there is growing interest in sensor-based structural health monitoring (SHM) approaches that offer objective, automated, and real-time diagnostics [

5].

Among sensor-based techniques, vibration analysis has emerged as a powerful nondestructive method for detecting mechanical anomalies in UAV components, particularly during the preflight stage when the vehicle is stationary but powered. Accelerometers embedded in UAV flight controllers can capture time-series vibration data indicative of structural integrity. Recent studies have demonstrated the viability of vibration-based SHM using Fourier analysis and spectrum-based classifiers for identifying specific component failures, such as damaged propellers or loose fittings [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Building upon these advances, this study presents the development of a domain-specific software application that integrates vibration-based SHM with a closed-loop Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) system. PLM refers to the comprehensive management of product-related data and processes throughout the entire lifecycle, from initial concept and design to operation, maintenance, and disposal [][Wi2008]. When extended with real-time feedback and embedded sensing technologies, PLM evolves into a Closed-Loop Lifecycle Management (CL2M) system, enabling dynamic updates, predictive analytics, and enhanced stakeholder collaboration [

11,

12,

13,

14].

In this work, vibration data collected during UAV preflight checks are classified using state-of-the-art deep learning models, including Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), to detect structural faults. A custom application interfaces with the UAV through the DroneKit-Python API and integrates with the Aras Innovator PLM platform via RESTful web services to support predictive maintenance operations. The resulting closed-loop architecture facilitates automated decision-making, lifecycle traceability, and multi-stakeholder access to maintenance data.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II describes the methodology for vibration data collection and classification. Section III presents the system architecture and PLM integration. Section IV discusses experimental results and predictive performance, and Section V concludes with key findings and future directions for UAV maintenance systems.

2. Predictive Fault Classification Using Vibration Data

This section presents the development and implementation of vibration-based fault classification models for the structural health monitoring of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Mechanical failures resulting from cyclic loading or external disturbances often lead to abnormal vibration patterns in UAV components. If not identified in a timely manner, these anomalies can cause severe structural damage or mission-critical failures. To mitigate this risk, a predictive maintenance methodology is proposed, utilizing time-domain vibration data collected during the UAV’s pre-flight stage. This data is employed to train multiple deep learning models capable of detecting and classifying structural faults. The resulting trained models are integrated into a customized UAV information management system, developed within the Aras Innovator Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) platform. The architecture and integration of this system are described in detail in Section III.

2.1. Data Collection and System Overview

The UAV system used in this study is equipped with a Pixhawk 2.4.8 flight controller, which manages motor operation and overall flight control. Communication between the flight controller and an external computer is facilitated through MAVLink (Micro Air Vehicle Link), a lightweight communication protocol widely used for telemetry and command exchange between unmanned vehicles and ground control stations.

The Pixhawk features an onboard MPU6000 inertial measurement unit (IMU), which captures three-axis acceleration data critical for vibration-based monitoring. In this implementation, vibration data is collected in real time using the DroneKit-Python API and transmitted directly to the processing environment, eliminating the need to retrieve logs from the flight controller’s internal memory. DroneKit-Python provides a high-level interface for both sending commands and receiving telemetry via MAVLink.

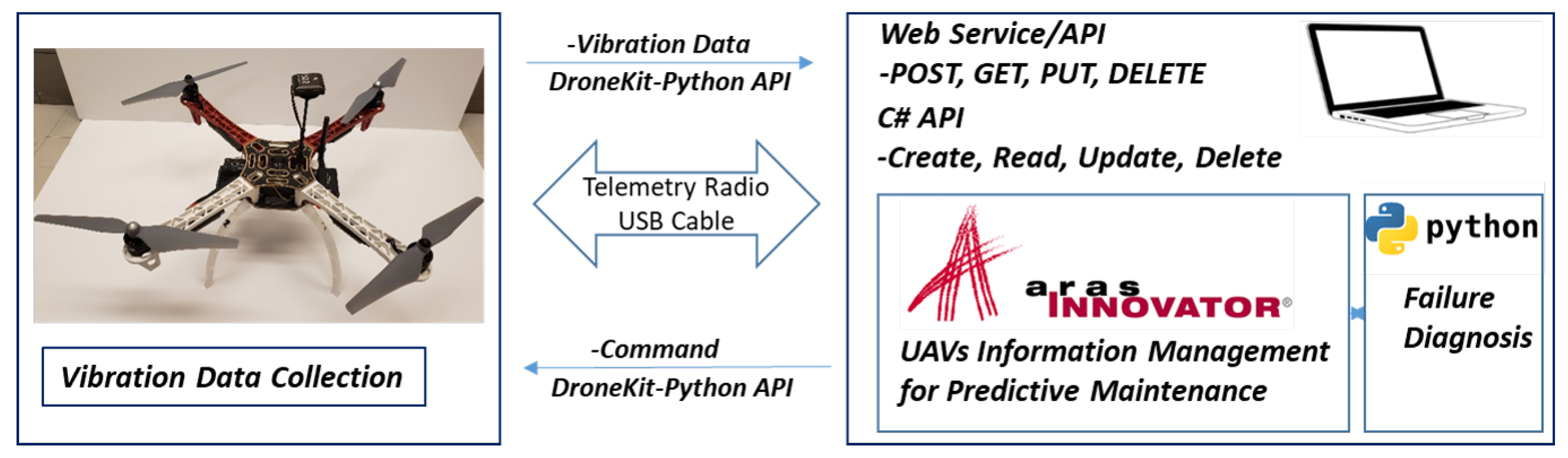

As illustrated in

Figure 1, vibration data is transmitted from the UAV to the computer via either a USB cable or telemetry radio. In this study, a USB connection is used during the pre-flight stage to ensure reliable, high-bandwidth data transfer. Once the UAV is armed and stabilized, the system enters a five-second initialization period, during which telemetry parameters such as battery level, attitude, and velocity are checked to ensure stable conditions. Following this brief delay, vibration data is recorded for 30 seconds while the UAV remains stationary. The collected time-series data is then used to train fault classification models within a Python-based environment. To train the predictive models, vibration data was collected under eight structural conditions representing both healthy and faulty scenarios:(I) Healthy (no structural issue), (II) Propeller missing on motor 1, (III) Damaged propeller 1, (IV) Damaged propeller 2, (V) Damaged propeller 3, (VI)Damaged propeller 4, (VII) Loose screws on leg 1, and (VIII) Loose screws on motor 1.

These scenarios represent realistic mechanical fault conditions, and the corresponding time-domain acceleration signals serve as the foundation for developing and validating deep learning-based fault classification models.

2.2. Vibration Data Set and Properties

The dataset used in this study was collected from a quadcopter via an inertial measurement unit (IMU) integrated into the flight controller. The recorded vibration data consists of raw acceleration values along the X, Y, and Z axes and is stored in the time domain, where vibration amplitude is plotted against time. The unit of measurement for all acceleration data is meters per second squared (m/s²).

Unlike many traditional structural health monitoring approaches that transform vibration signals into the frequency domain for spectral analysis, this study retains the original time-domain data format. This decision allows for the direct application of deep learning-based time series classification techniques.

Table 1 presents a sample excerpt of the raw dataset, showing four columns: time, and acceleration values along the X, Y, and Z axes.

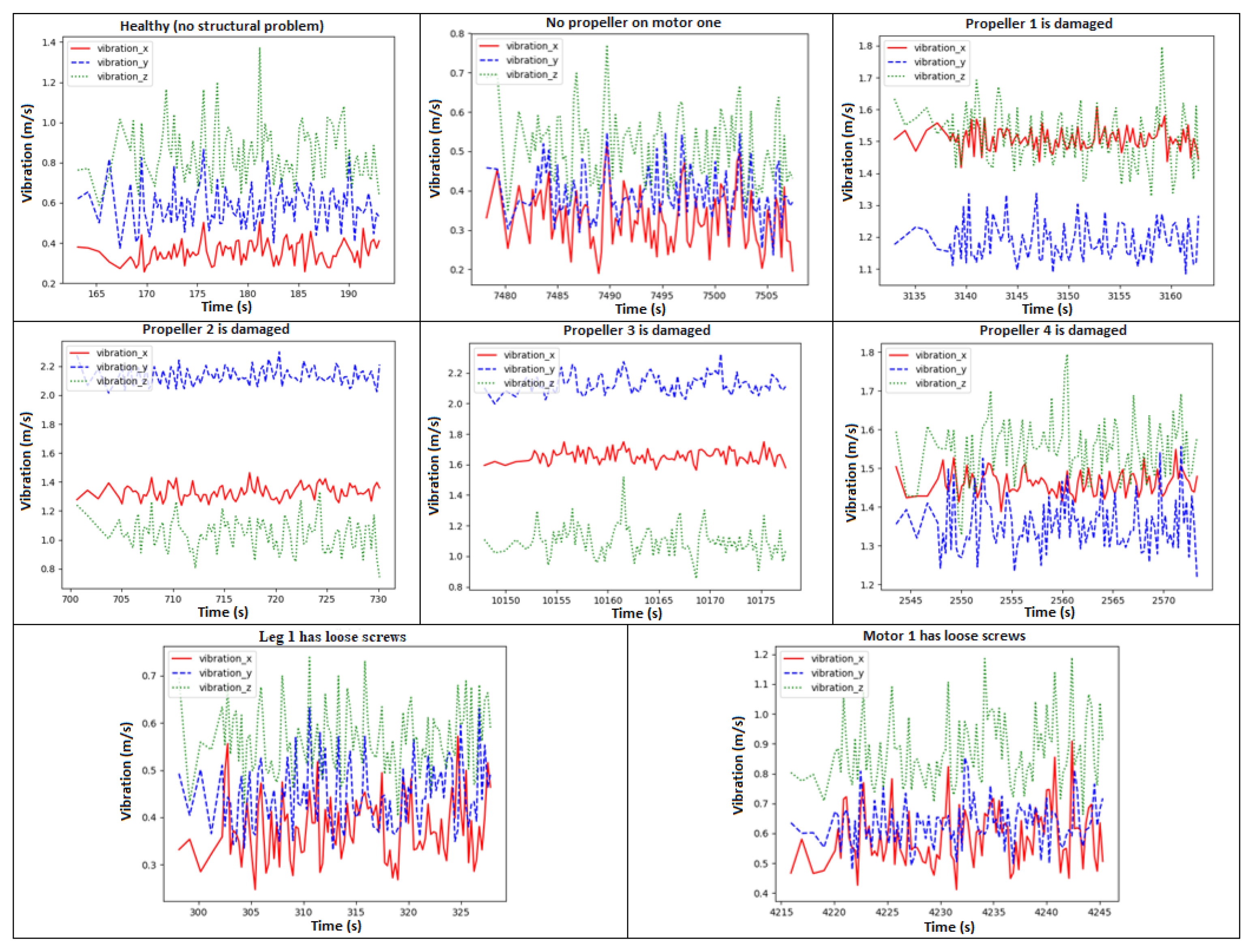

To characterize the effects of various mechanical faults, data was collected across eight predefined structural scenarios, including healthy and damaged conditions. The vibration profiles associated with each fault exhibit distinct patterns across the three axes. As visualized in

Figure 2, removing propeller 1 leads to a noticeable decrease in vibration across all directions, with the largest reduction observed along the Z-axis. Conversely, when propeller 1 is clipped, the vibration amplitude increases significantly across all axes, most prominently in the X-direction. Damage to propeller 4 shows a similar trend to that of propeller 1, though with slightly more vibration in the Y-axis. Damage on propellers 2 and 3 primarily affects the Y-direction, while propeller 3 also exhibits an elevated response in the X-direction. Structural loosening faults behave differently: motor 1 with loose screws generates high vibration in both X and Y directions, while leg 1 with loose screws leads to a slight decrease in overall vibration but increased signal irregularity.

These observed patterns confirm that different structural faults result in unique time-domain vibration signatures, which can be effectively leveraged for model training and fault classification using deep learning algorithms.

2.3. Model Training and Deployment

This section presents the development and deployment of deep learning models for UAV fault classification using the time-domain vibration dataset. While many time-series classification methods are available, this study employs three well-established deep neural network architectures: Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). These models are widely recognized for their ability to learn complex temporal patterns and have demonstrated strong performance across a range of sequential data applications.

LSTM networks, introduced by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber [

15], enhance traditional recurrent neural networks (RNNs) with memory cells capable of retaining long-term dependencies. GRUs, introduced by Cho et al. [

16], simplify the LSTM architecture with fewer parameters while maintaining comparable performance. CNNs, although originally developed for image processing tasks [

17], have been successfully adapted for time-series classification [

18,

19] due to their capacity to extract local patterns in sequential data.

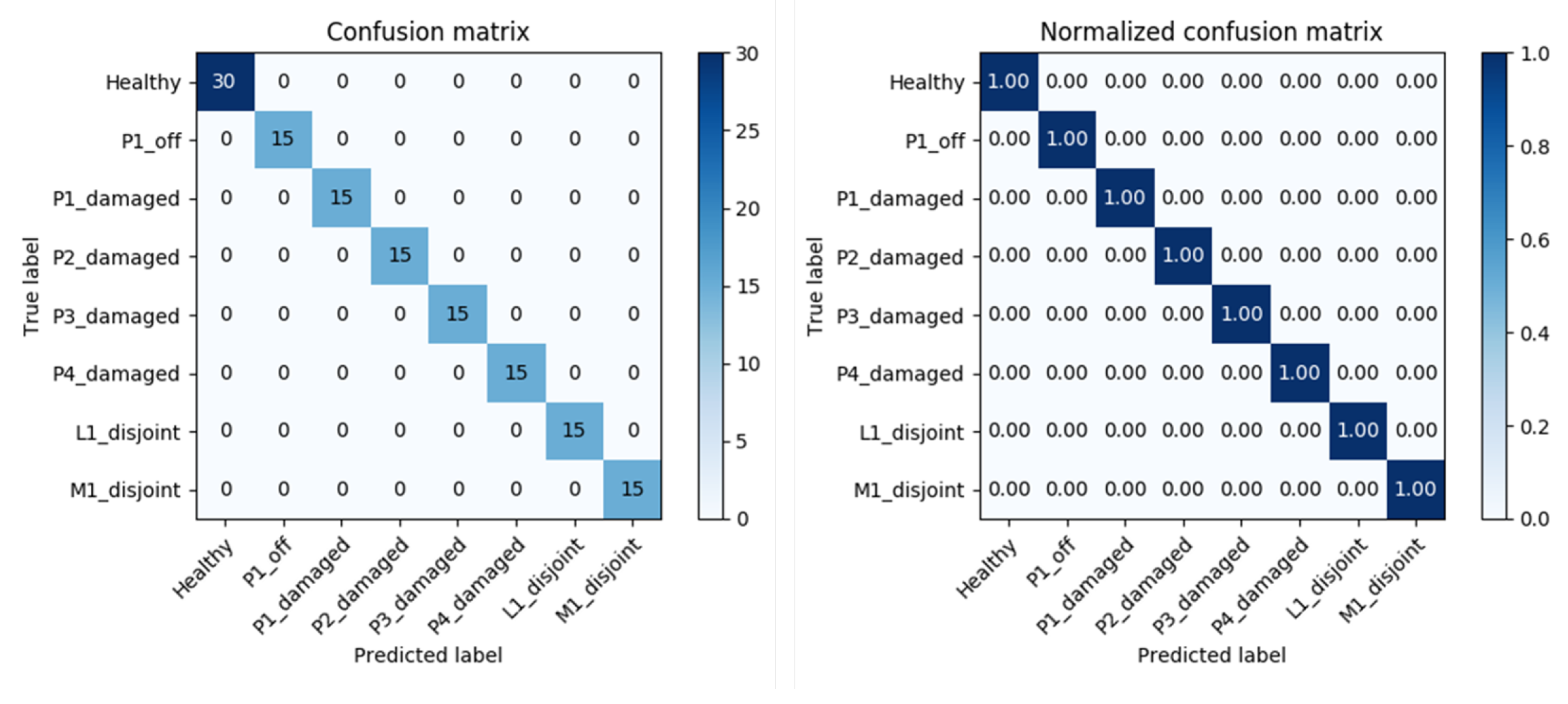

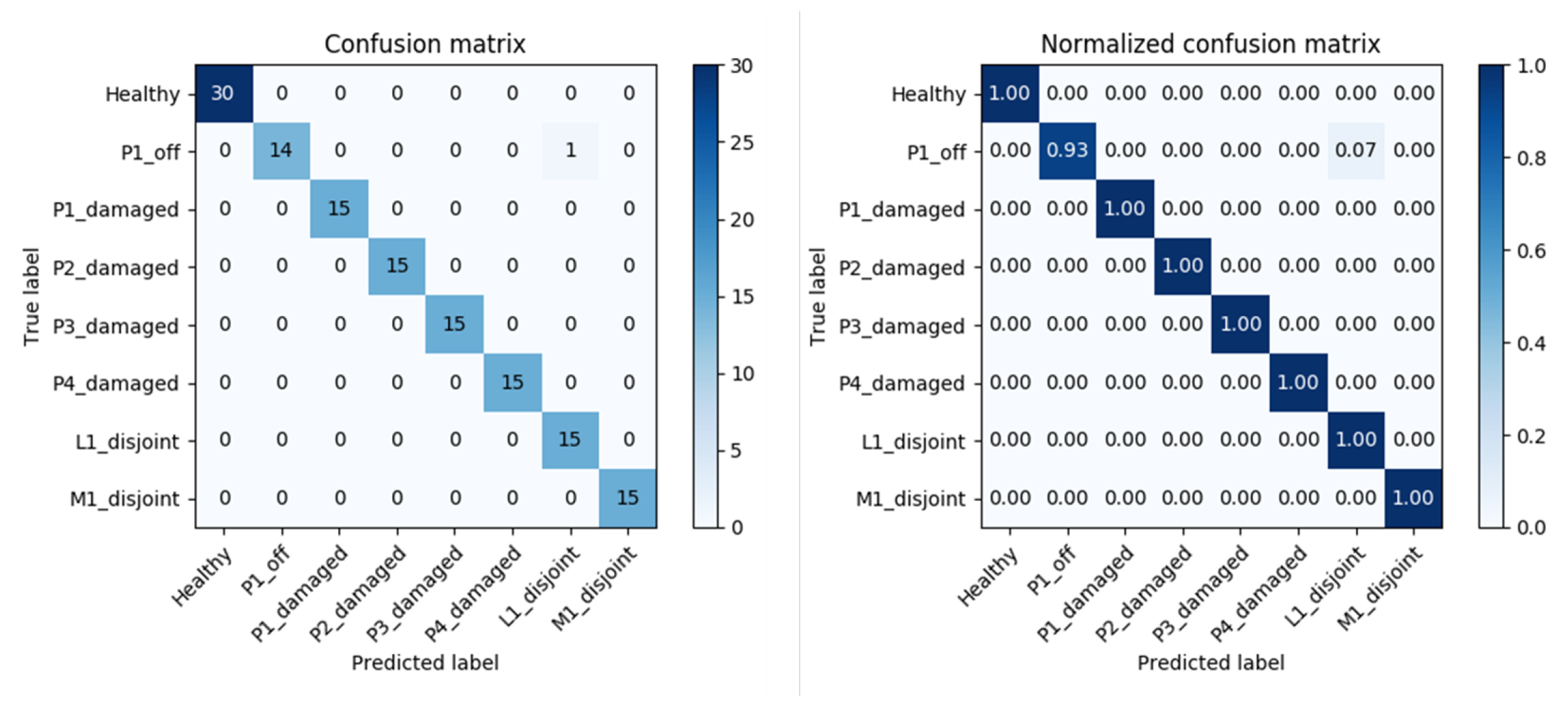

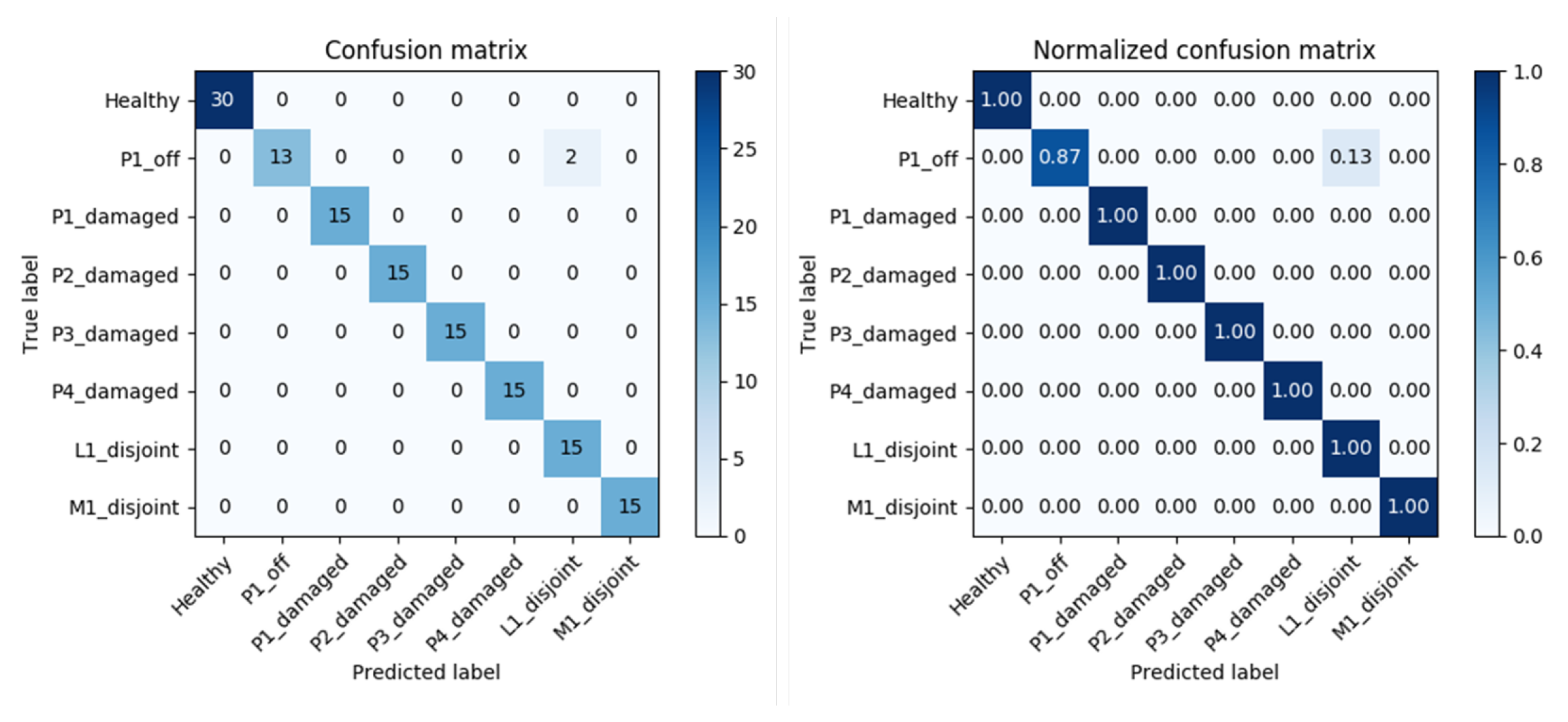

In this study, a total of 487 vibration data samples were used to train the GRU, CNN, and LSTM models. The models were developed and trained using the PyTorch framework in Python. For evaluation, 30 test data sets from the healthy class and 15 test data sets from each of the seven fault categories were used. The classification performance of each model is presented in the form of a confusion matrix and a normalized confusion matrix. These matrices illustrate the prediction accuracy across all fault classes, with rows representing true labels and columns representing predicted labels.

Figure 3 shows the results of the GRU model, which achieved 100% classification accuracy, correctly identifying all instances in the eight classes,

Figure 4 presents the results of the CNN model, which achieved a 99.3% test accuracy, with a slight misclassification in the "propeller off" category, and

Figure 5 illustrates the performance of the LSTM model, which achieved 98.9% accuracy, showing minor confusion between similar fault classes.

Rather than selecting a single best-performing model, all three trained models are integrated into the UAV information management system developed within the Aras Innovator PLM platform. This multimodel approach provides flexibility, allowing users to select the most appropriate model based on context, such as computational resources or mission-critical constraints. The ability to store, manage, and apply multiple models directly from the PLM platform supports robust and adaptable predictive maintenance workflows. Further details on the PLM-based model management and system architecture are provided in the following section.

3. System Architecture of the UAS Predictive Maintenance Platform

The proposed system represents a closed-loop Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) application specifically designed for the vibration-based structural health monitoring of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Unlike conventional PLM systems that focus primarily on engineering design and documentation [

20], Closed-Loop Lifecycle Management (CL2M) emphasizes real-time data integration, model-driven diagnostics, and continuous information feedback throughout the product lifecycle. This facilitates collaboration among all stakeholders, including UAV users, engineers, service operators, and supply chain managers, by offering on-demand access to up-to-date and actionable information.

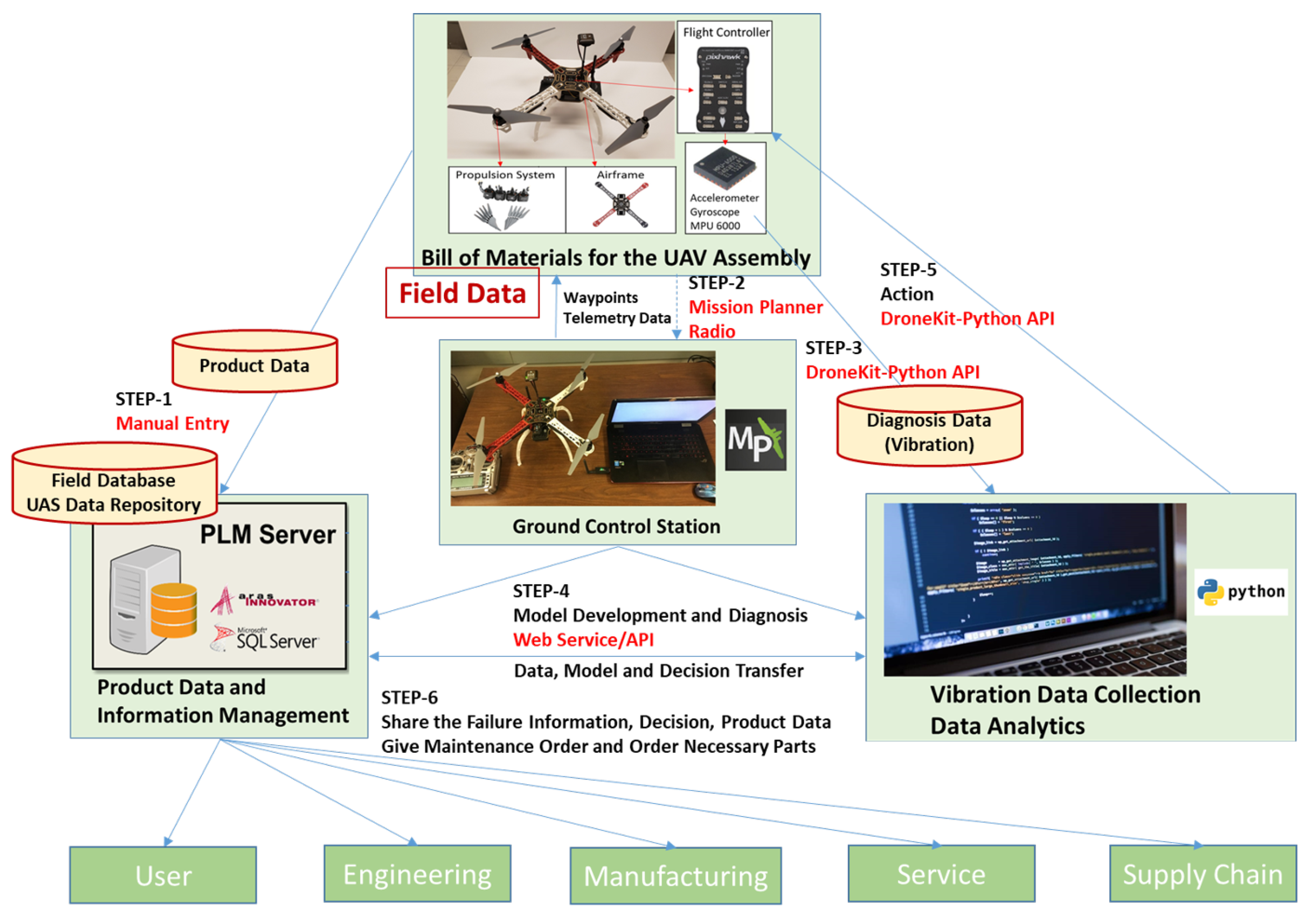

Figure 6 presents an overview of the UAS platform implemented for vibration-based structural health monitoring. The architecture comprises four main components:

The physical product—the UAV and its embedded sensors and flight control hardware,

A data analytics layer that processes time-domain vibration signals using deep learning models,

A custom-developed PLM platform, built on Aras Innovator, acting as the UAV data repository, and

A communication infrastructure that enables seamless data exchange among all system components.

The physical UAV system incorporates critical components for both flight control and monitoring of structural conditions. These include the Pixhawk 2.4.8 flight controller, an onboard MPU6000 accelerometer, four brushless motors with propellers, the airframe, and associated structural assemblies. During operation, particularly in the pre-flight stage, vibration data is acquired via the UAV’s internal IMU sensor. This data is then transmitted in real time to a computational platform using the DroneKit-Python API, enabling prompt fault detection and response.

Each UAV component is digitally mirrored within the PLM platform following a digital twin paradigm. This digital representation captures the bill of materials (BOM), component specifications, lifecycle status, supplier records, historical faults, and maintenance events. The system improves traceability, diagnostic precision, and maintenance decision-making throughout the operating lifecycle of the UAV by mapping the physical structure of the UAV to a digital environment. The subsequent subsections describe the remaining elements of the system in detail below, including:

The development and structure of the UAV PLM platform,

The data and file exchange mechanisms between the drone, computational environment, and PLM system, and

The integration of predictive models within the UAV platform to enable intelligent, automated health assessments and fault responses.

3.1. UAV Information Management System for Predictive Maintenance

The core of the proposed system is a customized Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) platform built on Aras Innovator, serving as a centralized repository and knowledge hub for UAV health monitoring and predictive maintenance. This platform integrates a relational database, file storage, and a web-based interface to manage documents, datasets, UAV system models, diagnostic outputs, and maintenance workflows. The system architecture is designed in alignment with established standards and methodologies, including: NATO STANAG 4586 [

21] for UAV architecture and metadata standardization, a PLM-UAS framework based on the work of Sassanelli et al.[

22], and the CRISP-DM [

23] methodology, embedded within the lifecycle workflow to guide data analytics processes and enable continuous model refinement.

The platform is structured around three integrated layers:

UAV Data Repository – Acts as the foundational database, storing structured information related to UAV platforms, subsystems, parts, and their associated technical documents (CAD files, BOMs, maintenance records, etc.),

Data Analytics Layer – Supports the development, deployment, and management of machine learning models used for fault detection and predictive analytics. This includes model lifecycle tracking and evaluation using datasets collected from UAV operations, and

Predictive Maintenance Layer – Provides specialized tools and workflows for health monitoring, failure prediction, and diagnostics. Connects analytics outputs to maintenance actions, linking predictive insights to physical components and maintenance documentation.

In Aras Innovator, all entities are represented as Items and interconnected via Relationships, which define the source and related items along with associated metadata. This structure enables rich and flexible modeling of UAV platforms and their components, allowing the system to represent structural hierarchies, part relationships, diagnostics history, and maintenance procedures. All models, datasets, and related documents are stored with full version control and traceability across their lifecycles.

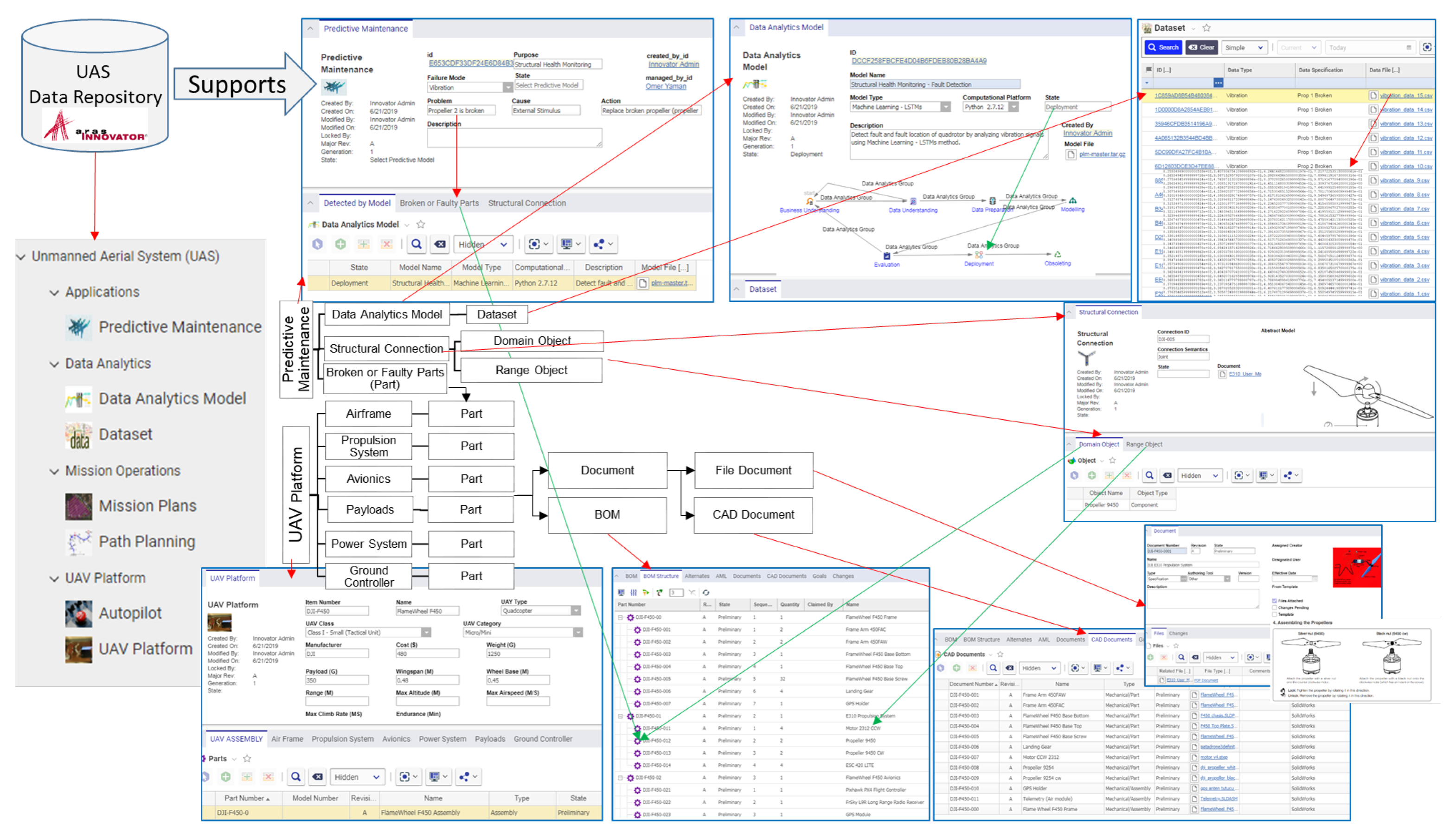

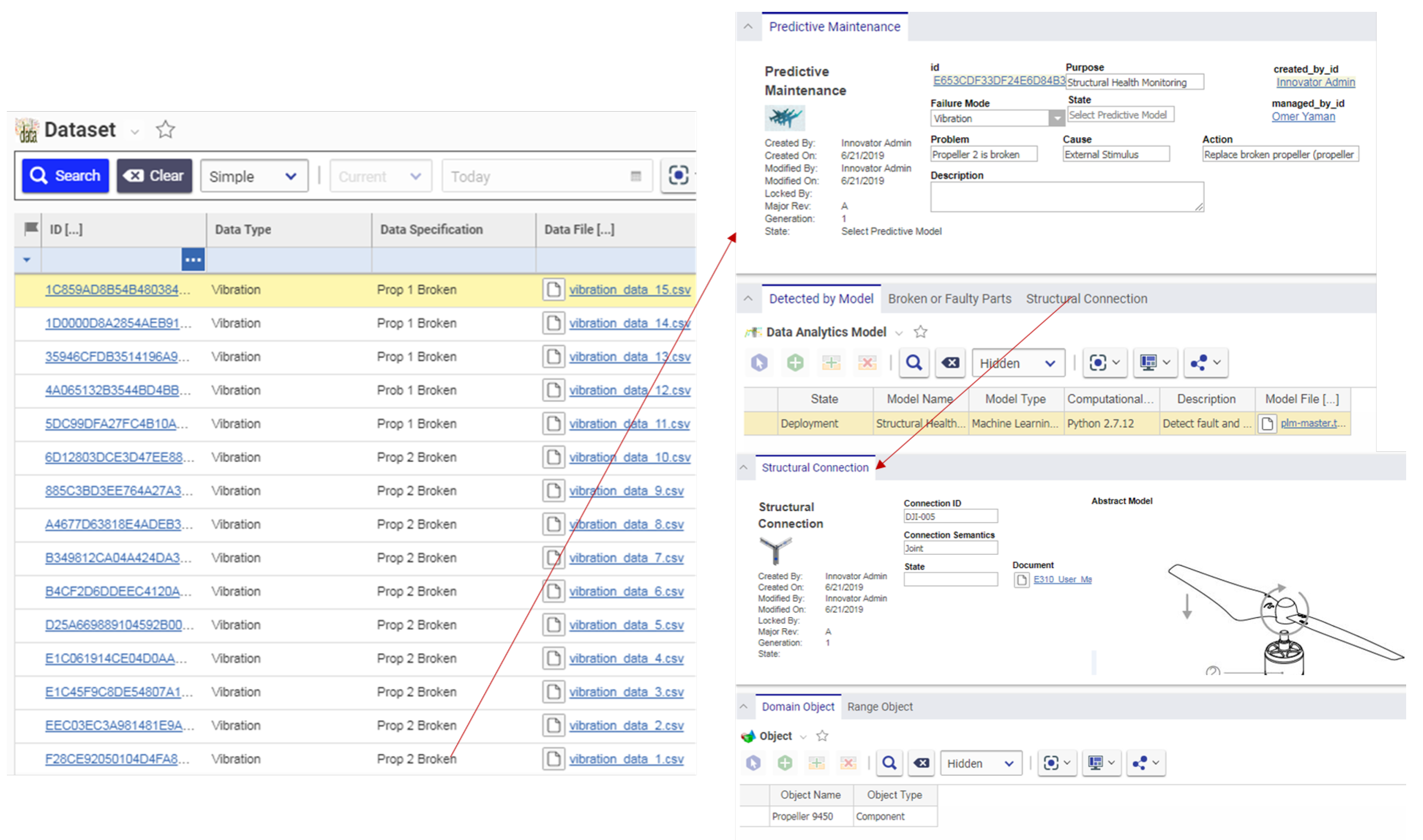

As depicted in

Figure 7, the system supports end-to-end predictive maintenance workflows. A Predictive Maintenance Item is linked to a trained Data Analytics Model, which leverages historical Datasets such as vibration data to detect potential faults. These predicted issues are mapped through Structural Connections to specific Parts, which are in turn referenced in the UAV platform’s Bill of Materials (BOM) and linked to detailed CAD documents and maintenance files. This traceability chain allows users to visualize and track the impact of a predicted failure, from initial detection to the associated physical component and supporting engineering data.

Whether handling static data (e.g., platform structure, payload specifications) or dynamic data (e.g., vibration logs and fault predictions), users interact through a CRISP-DM aligned data management layer. This process ensures the integrity, consistency, and contextual readiness of data, facilitating downstream analytics, decision-making, and iterative model improvement.

Data entry into the PLM system may occur manually or automatically via APIs, enabling real-time synchronization between UAV operations and the analytics infrastructure. Vibration data and other telemetry are transmitted to the computational layer, where analytics models process and generate diagnostic insights. These insights are then reintegrated into the PLM system and made accessible to engineers, operators, and maintenance personnel, enabling proactive fault mitigation and enhanced lifecycle decision-making.

To support the data exchange between UAVs and PLM systems, a dedicated communication mechanism is developed, serving as the integration bridge between operational data sources and the lifecycle management environment.

3.2. Data and File Exchange

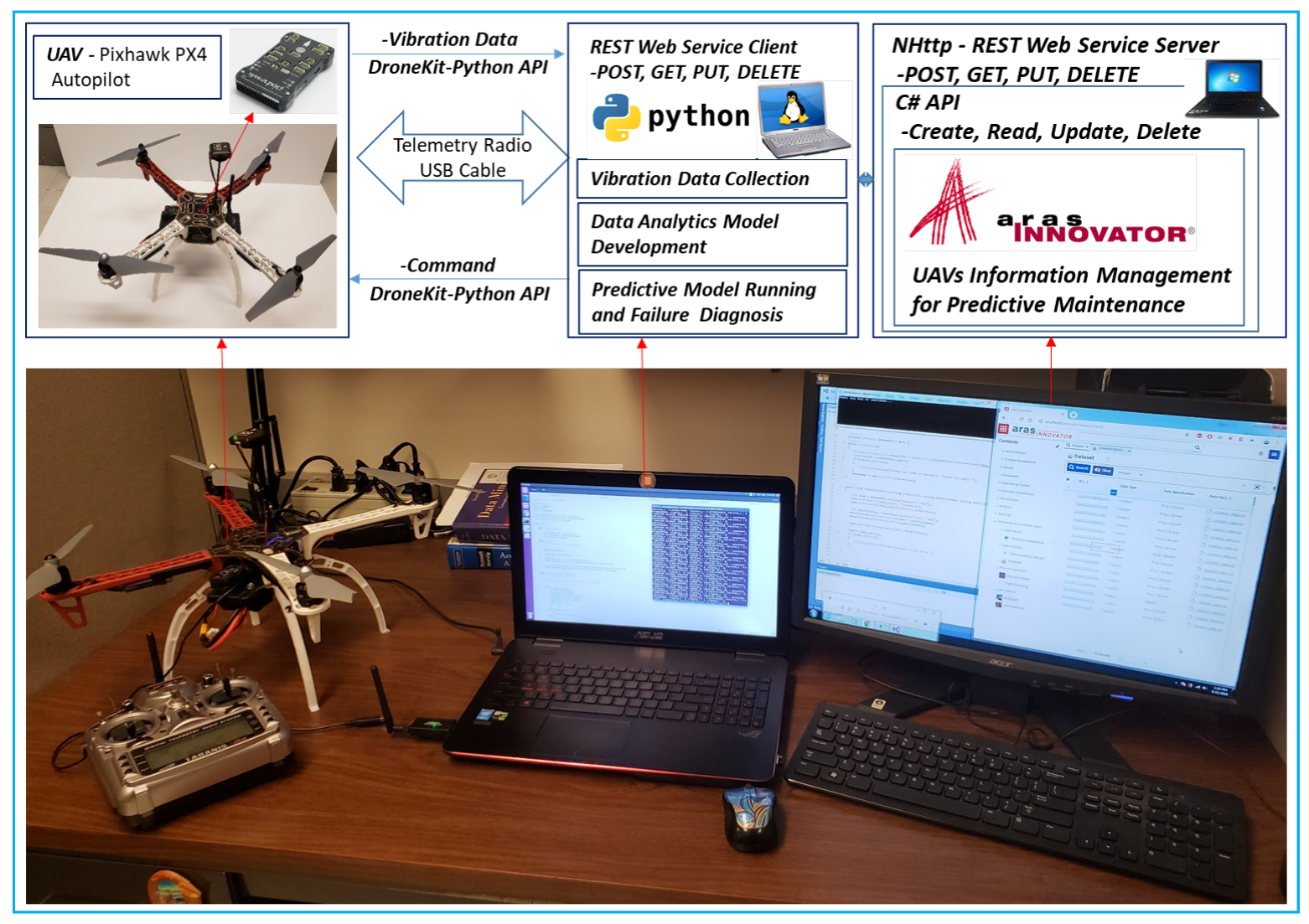

To enable seamless integration among the UAV, the computational platform, and the UAV management system, a robust two-tier communication architecture has been developed. This architecture supports real-time data acquisition, analysis, and storage, thereby reinforcing the predictive maintenance framework and enhancing operational responsiveness. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the experimental setup consists of a UAV equipped with vibration sensors, a computational platform running a Python environment, and a workstation hosting the Aras Innovator PLM system.

The UAV interfaces directly with the computational platform via telemetry or USB connection, utilizing the DroneKit-Python API. This API facilitates the collection of real-time sensor data, specifically vibration signals, and enables the transmission of control commands. The computational platform, executing deep learning models within its Python environment, interfaces with the UAV using the DroneKit API to retrieve data and, when necessary, issue commands. For instance, upon detecting a critical structural anomaly, the system can automatically issue a DISARM command to the UAV, effectively mitigating further risk. In parallel, the system logs the incident and prediction outcome within the PLM environment, ensuring full traceability and historical tracking.

The computational platform also functions as a REST client, responsible for managing interactions with the Aras Innovator system. This interaction is realized through a RESTful Web Service, developed using the NHttp framework, an open-source asynchronous HTTP server designed for the .NET platform. The service acts as a bridge between the diagnostic engine and the PLM system, transmitting data analytics outputs, including prediction results and raw sensor logs, to the centralized repository.

The RESTful interface supports standard HTTP methods—POST, GET, PUT, and DELETE—to enable full interaction with resources within the PLM system. On the server side, the Aras.IOM C# API is employed to facilitate secure communication with the Aras Innovator database. This API allows the system to construct AML (Aras Markup Language) queries and perform CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations on Items stored in the PLM. Consequently, the architecture supports the automated exchange of:

Vibration data files acquired from UAV telemetry,

Fault prediction outcomes generated by the deployed analytics models, and

Trained data analytics models used for inference and retraining.

3.3. UAV Platform Integration and Predictive Analytics Application

The integration of predictive analytics with the UAV management system is realized through a seamless workflow that connects the data acquisition, model inference, and lifecycle management components within the Aras Innovator PLM platform. As illustrated in

Figure 7, the system facilitates the retrieval, execution, and update of data analytics models via RESTful web services and C# APIs, enabling closed-loop, real-time diagnostics and decision support for UAV operations.

The user can select a desired deep learning model- GRU, LSTM, or CNN through the PLM interface, which transmits the corresponding execution file to the Python environment. If no selection is made, a GRU model is used by default. Once the vibration data is collected, it is processed using the specified model to classify the signals for potential anomalies or structural faults. The classification results are then transmitted to the UAV for operational response and to the PLM system for archival, reporting, and informed decision-making.

If a fault is diagnosed, such as "Propeller 2 is damaged", the system initiates two concurrent actions:

Operational Response: A DISARM command is immediately issued to the UAV through the DroneKit-Python API, preventing further mechanical damage and ensuring safety.

-

Lifecycle Management Response: An automated maintenance order is generated in the Aras Innovator PLM system. This maintenance record includes:

- -

Component Identification: Specifies the faulty component (e.g., Propeller 2) using structured metadata,

- -

Fault Description: Captures the nature and severity of the diagnosed problem.

- -

Replacement Instructions: Provides step-by-step visual and textual guidance for part removal and installation.

- -

Supporting Documents: Includes related CAD drawings. technical manuals, cost information, supplier references, and part numbers.

- -

Ordering Information: Lists qualified vendors, lead times, and part availability to streamline procurement.

This maintenance order is immediately accessible to all relevant stakeholders, including operators, engineers, service teams, designers, and suppliers, through the PLM web interface. The system enables these users to monitor the issue in real time, initiate corrective actions, and document service outcomes. Engineers can use this data to inform redesign efforts, while service departments gain visibility into recurring failures and part reliability.

The PLM repository also retains a detailed fault history, allowing for performance trend analysis and model refinement. Over time, the continuous accumulation of sensor data, diagnostic outputs, and maintenance records contributes to the ongoing improvement of predictive models. This forms the foundation for a closed-loop UAV lifecycle management system, where operational insights directly influence future product designs and service strategies.

By integrating predictive analytics within the PLM environment and automating the workflow from fault diagnosis to maintenance actions, the system minimizes downtime, enhances operational safety, and supports informed, data-driven decision-making across the UAV value chain.

4. Results and Discussions

This study presents a preliminary but effective implementation of a closed-loop Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) architecture for vibration-based structural health monitoring of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). The main objectives were to develop and evaluate deep learning models for fault classification, integrate them into a customized PLM environment, and demonstrate real-time predictive maintenance capability.

Vibration datasets were collected from a quadcopter to train and evaluate three different time-series classification models: Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). These trained models were stored and versioned within the Aras Innovator PLM system, along with associated training and test datasets, making them readily accessible for users during both the development and deployment stages.

As depicted in

Figure 9, the UAV was armed and operated 15 times, with real-time vibration data being collected and analyzed during each run. The LSTM model, selected through the PLM interface, was used to process the data. The system correctly diagnosed structural faults in every instance:

10 instances identified Propeller 2 as damaged (due to edge clipping on Motor 2), and

5 instances identified Propeller 1 as damaged (from clipping on Motor 1).

In all cases, the platform successfully predicted both the existence and location of the fault with perfect accuracy. Once a failure was identified, the system issued a DISARM command via DroneKit to prevent further damage and automatically generated a maintenance order within the PLM environment.

The generated maintenance order included detailed metadata such as the damaged component (e.g., Propeller 2), description of the fault and failure mode, visual documentation (e.g., CAD drawings), replacement instructions, supplier and cost information, and ordering details with part numbers and availability.

This information was instantly accessible to all relevant stakeholders operators, engineers, designers, suppliers, and maintenance teams through the PLM system. The live sharing of diagnostic results and action plans enabled rapid decision-making, minimized downtime, and contributed to a knowledge-rich digital thread for each UAV instance. The architecture thus demonstrated its capacity to close the loop between field data collection, real-time diagnostics, and actionable maintenance workflows.

Additionally, the PLM system served as a centralized repository for all vibration data, UAV configurations, maintenance documentation, and analytics models. It not only enhanced traceability and lifecycle visibility but also provided an interoperable platform where users could execute different pre-trained models (GRU, LSTM, or CNN) based on mission context or performance preferences.

5. Conclusion

This implementation highlights the potential of integrating intelligent analytics with PLM to reduce unplanned failures, lower maintenance costs, and accelerate feedback to design and production teams. As part of future work, the following directions are proposed:

Extending data collection to include in-flight UAV operations, incorporating additional variables such as battery health, temperature, and weather conditions,

Storing and managing models using standardized formats such as PMML to improve interoperability across platforms,

Enhancing the UAS data repository to support broader computational frameworks and enable deployment in diverse mission environments.

Overall, the results validate the technical feasibility and operational value of the proposed closed-loop PLM framework for UAV predictive maintenance. The system not only empowers users with real-time diagnostic capability but also establishes a scalable foundation for intelligent, lifecycle-oriented UAV structural health management.

Data Availability Statement

DURC Statement

Current research is limited to the product lifecycle management (PLM) and predictive maintenance in the aerospace and unmanned systems domain, which is beneficial in enhancing asset reliability, reducing maintenance costs, and improving operational efficiency and does not pose a threat to public health or national security. Authors acknowledge the dual-use potential of the research involving unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and intelligent maintenance technologies and confirm that all necessary precautions have been taken to prevent potential misuse. As an ethical responsibility, authors strictly adhere to relevant national and international laws about DURC. Authors advocate for responsible deployment, ethical considerations, regulatory compliance, and transparent reporting to mitigate misuse risks and foster beneficial outcomes.

References

- Gupta, S.G.; Ghonge, M.M.; Jawandhiya, P.M. Review of Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS). Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Eng. Technol. 2013, 2, 1646–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellenberg, A.J.; Structural health monitoring using Unmanned Aerial Systems. Dissertations 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1860/idea:7565 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Pavelko, V.; Ozolinsh, I.; Kuznetsov, S.; Pavelko, I. Structural Health Monitoring of Aircraft Structure by Method of Electromechanical Impedance. Int. Workshop of NDT Experts, Prague 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chamseddine, A.; Rabbath, C.A.; Gordon, B.W.; Su, C.-Y.; Rakheja, S.; Fulford, C.; Apkarian, J.; Gosselin, P. Development of advanced FDD and FTC techniques with application to an unmanned quadrotor helicopter testbed. J. Frankl. Inst. 2013, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kressel, I.; Handelman, A.; Botsev, Y.; Balter, J.; Gud’s, P.; Tur, M.; Gali, S.; Pillai, A.C.R.; Prasad, M.H.; Yadav, A.K.; et al. Health and Usage Monitoring of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Fiber-Optic Sensors. In Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) in Aerospace Applications; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, Y.K. Structural Health Monitoring For Unmanned Aerial Systems. Master’s Thesis, EECS Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, May 2014. Available online: http://www2.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2014/EECS-2014-70.html. [Google Scholar]

- Ghalamchi, B.; Mueller, M. Vibration-Based Propeller Fault Diagnosis for Multicopters. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Dallas, TX, USA, 12–15 June 2018; pp. 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echanique, C.; Shah, S. Classification of Structural Failure for Multi-rotor UAS. CS289A Final Project 2014.

- Tibaduiza Burgos, D.; Cerón-M, H. Damage classification based on machine learning applications for an unmanned aerial vehicle. In Proceedings of the Conference on Structural Health Monitoring; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wijk, D.; Etienne, A.; Guyot, E.; Eynard, B.; Roucoules, L. Enabled virtual and collaborative engineering coupling PLM system to a product data kernel. 2008.

- Karakoyun, F. A Methodology for Holistic Lifecycle Approach as Decision Support System for Closed-loop Lifecycle Management. 2015.

- Kiritsis, D. Closed-Loop PLM for intelligent products in the era of the Internet-Of-Things. Comput.-Aided Des. 2011, 43, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M.-J.; Grozel, C.; Kiritsis, D. Closed-Loop Lifecycle Management of Service and Product in the Internet of Things: Semantic Framework for Knowledge Integration. Sensors 2016, 16, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, H.-B.; Kiritsis, D. Several Aspects of Information Flows in PLM. IFIP Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2012, 388, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.; Van Merrienboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations using RNN Encoder-Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, C.B.J. Deep learning for time-series analysis. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.01887. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Lu, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Wu, D. Convolutional neural networks for time series classification. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2017, 28, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westkämper, E. Life Cycle Management and Assessment: Approaches and Visions towards Sustainable Manufacturing (keynote paper). CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2000, 49, 501–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STANAG-4586-Ed.3-Nov-2012. Standard Interfaces of UAV Control System (UCS) for NATO UAV Interoperability, NATO Standardization Agency (NSA), 2012.

- Sassanelli, C.; Bernabei, G.; Lazoi, M.; Corallo, A. A PLM-Based Approach for Un-manned Air System Design: A Proposal. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Shearer, C. The CRISP-DM Model: The New Blueprint for Data Mining. J. Data Warehous. 2000, 5, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).