Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

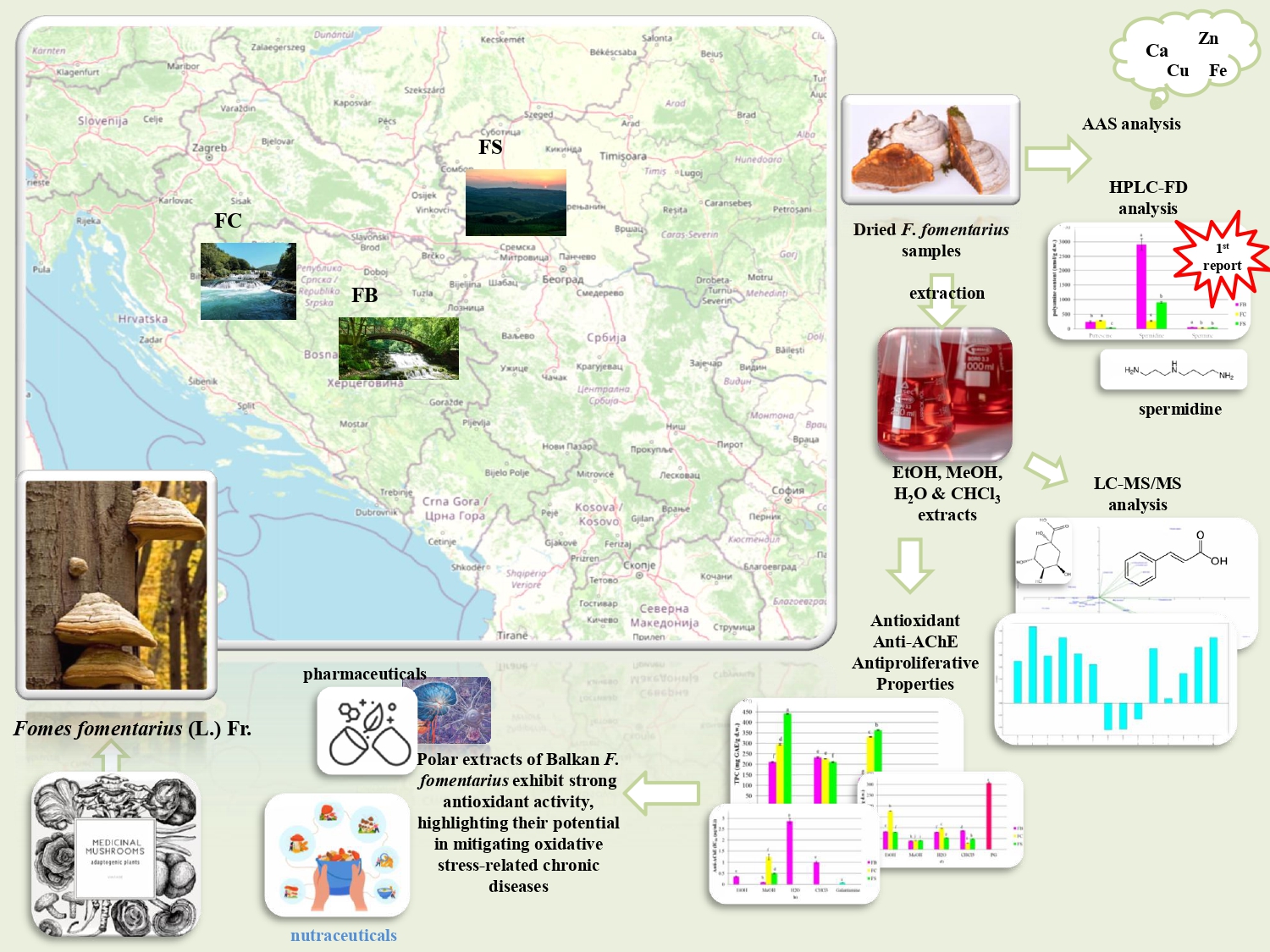

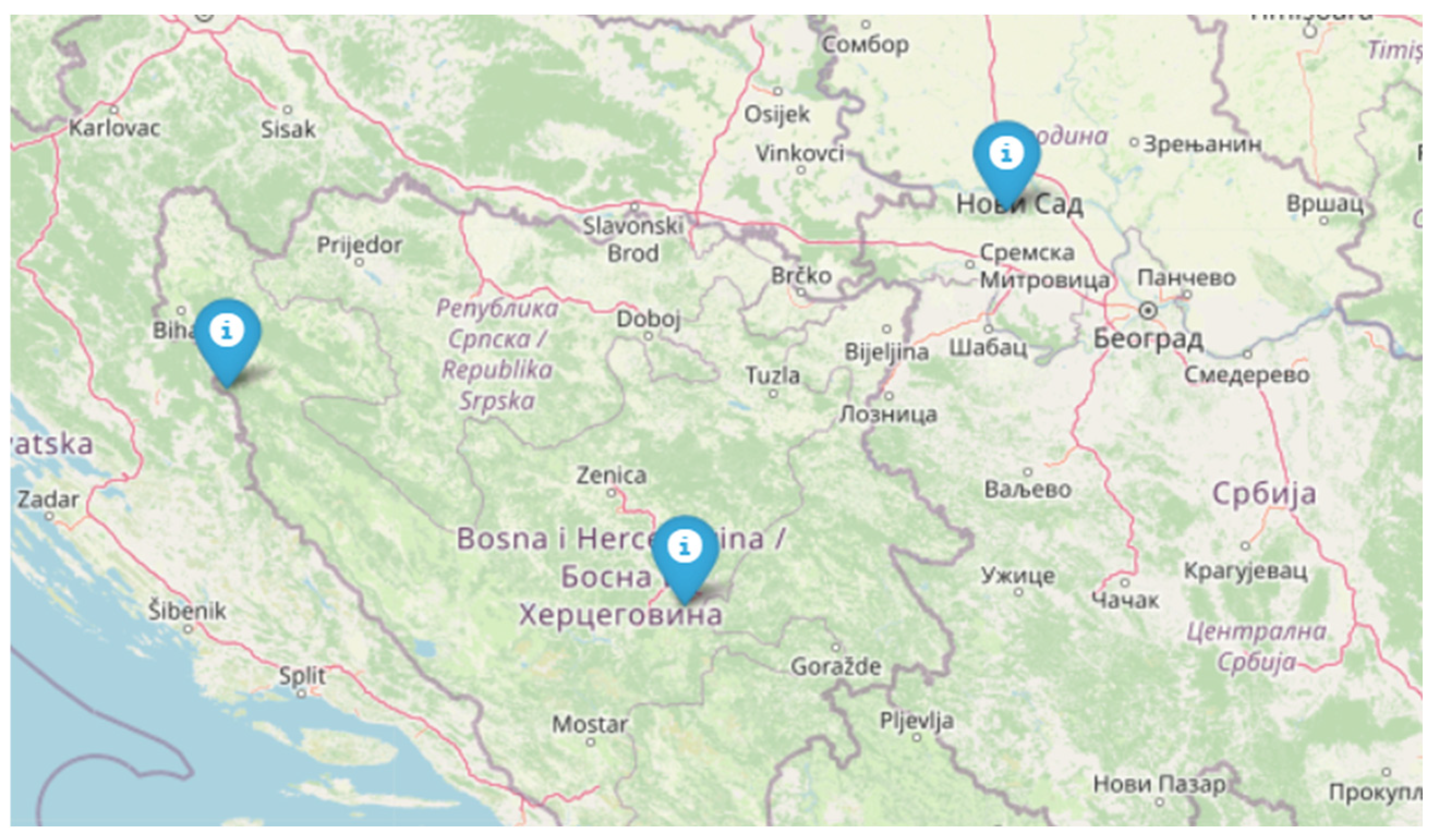

2.1. Mushroom Material

2.2. Extracts Preparation

2.3. Mycochemical Characterization

2.3.1. Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (AAS)

2.3.2. HPLC-FD Determination of Selected Polyamines Content

2.3.3. LC/MS-MS Quantification of Phenolic Compounds and Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Determination

2.3.4. Determination of Total Carbohydrate Content

2.4. Biological Activities

2.4.1. Determination of the Antioxidant Activity

2.4.2. Determination of Anti-Acetylcholinesterase Activity (Anti-AChE)

2.4.3. Determination of Antiproliferative Activity

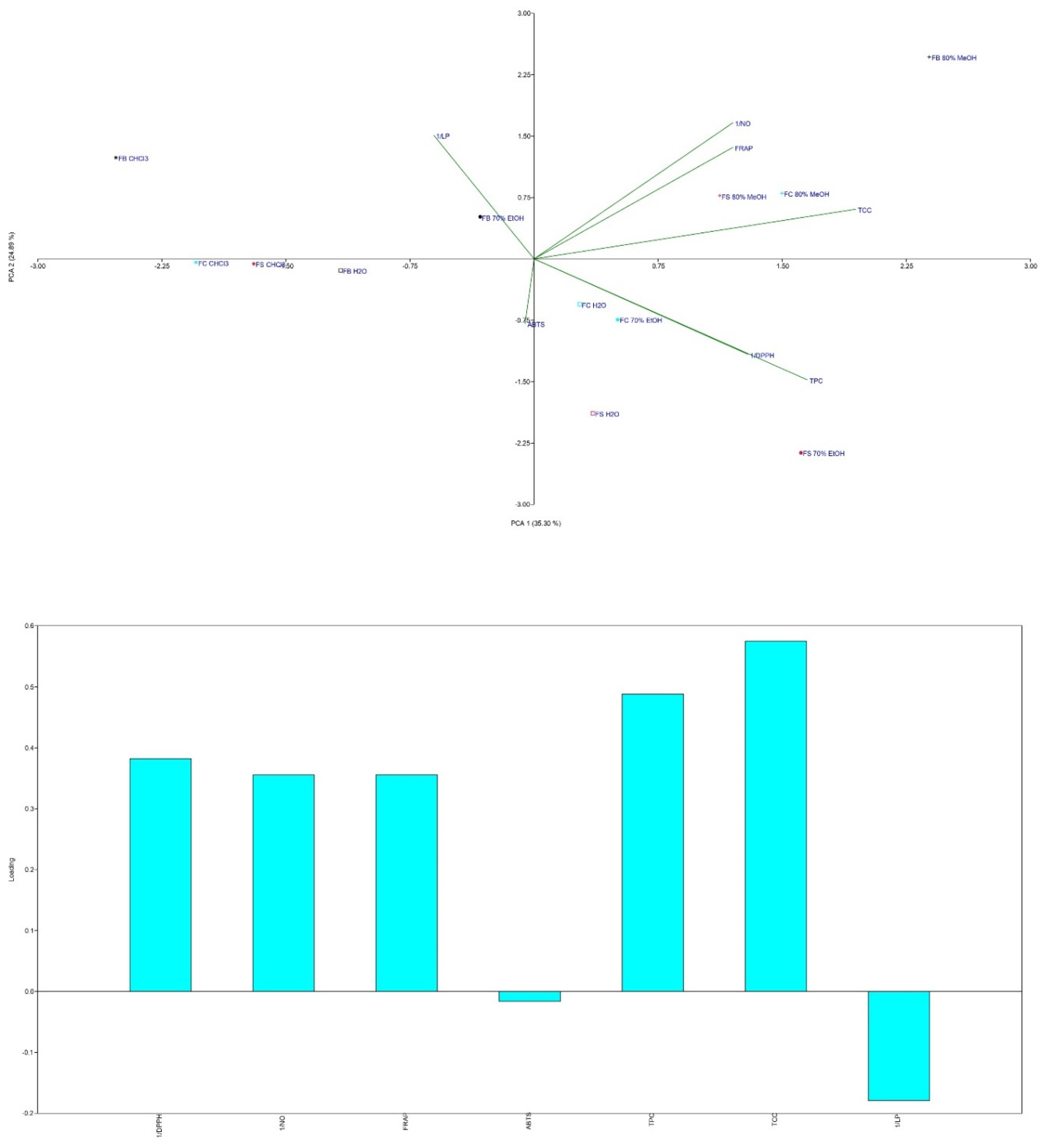

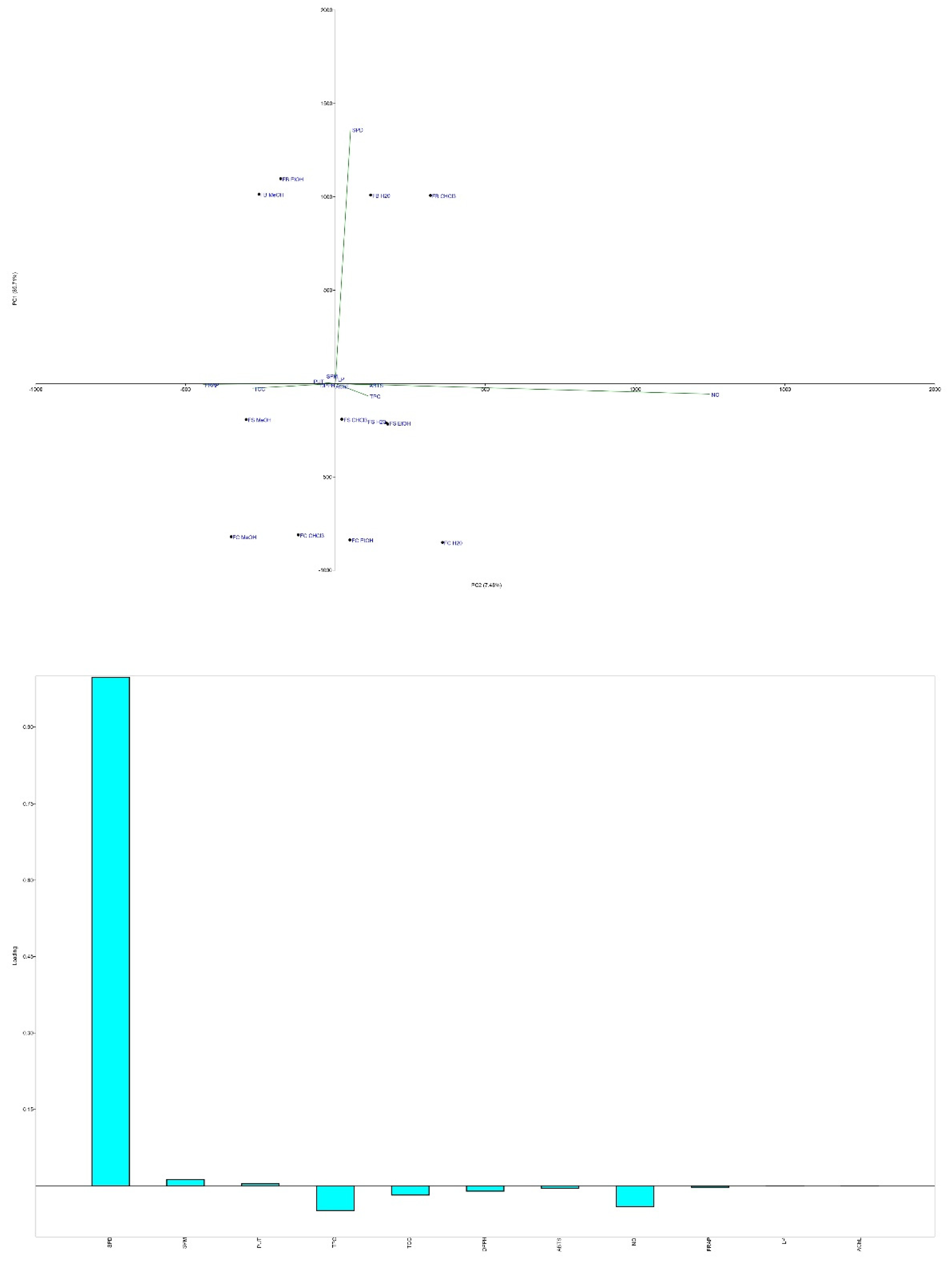

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mycochemical Profile

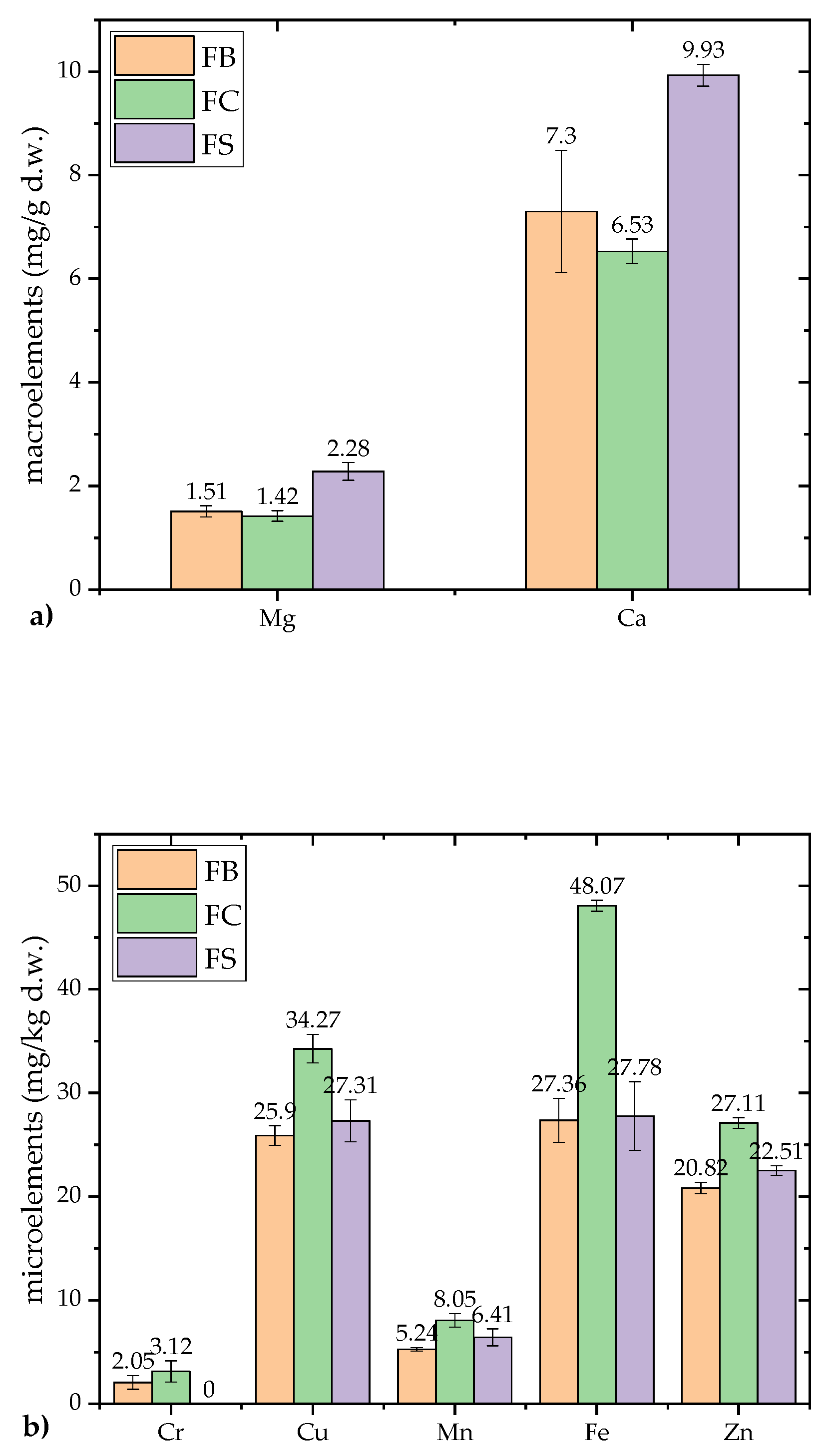

3.1.1. Macro- and Microelements Content

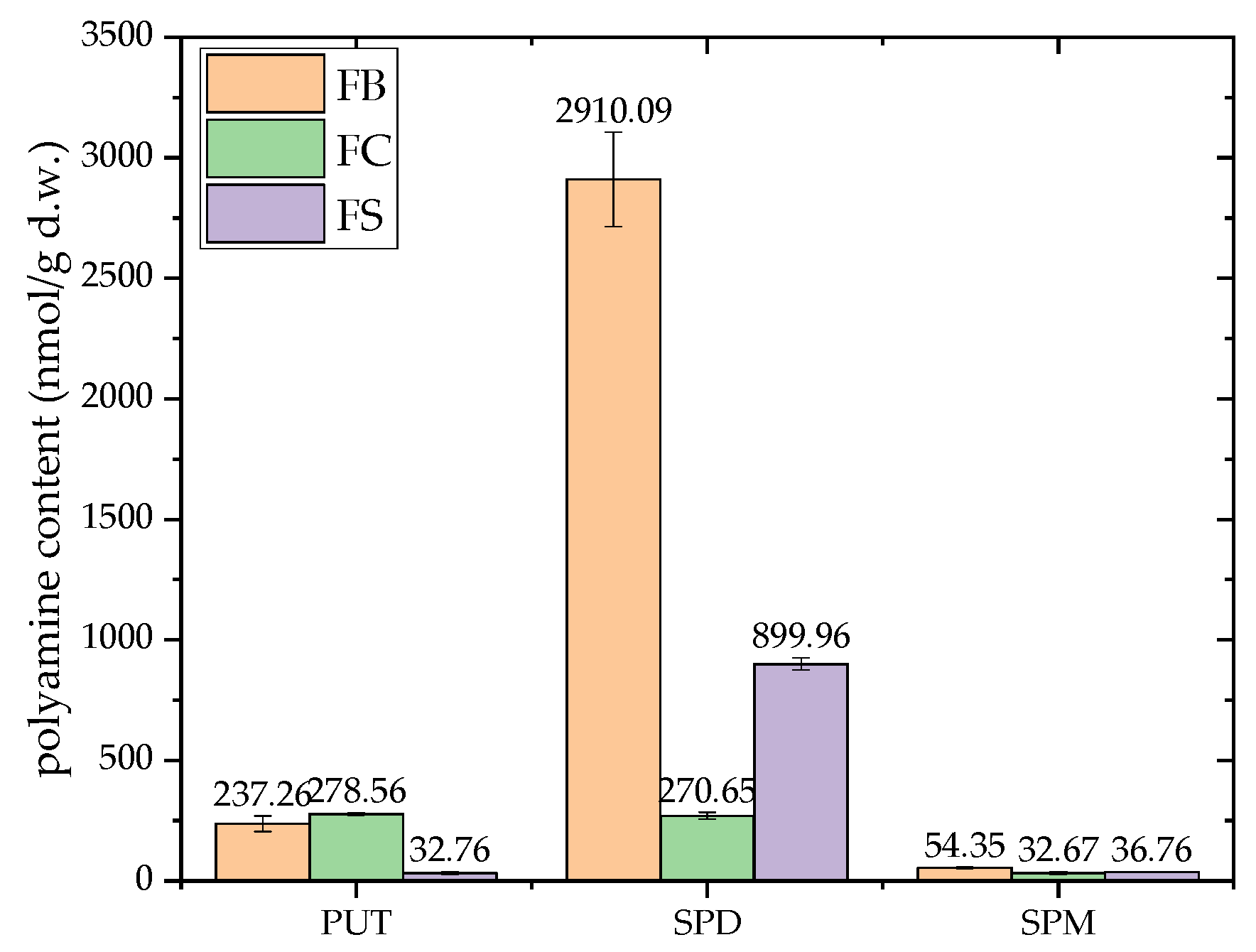

3.1.2. Polyamines Content

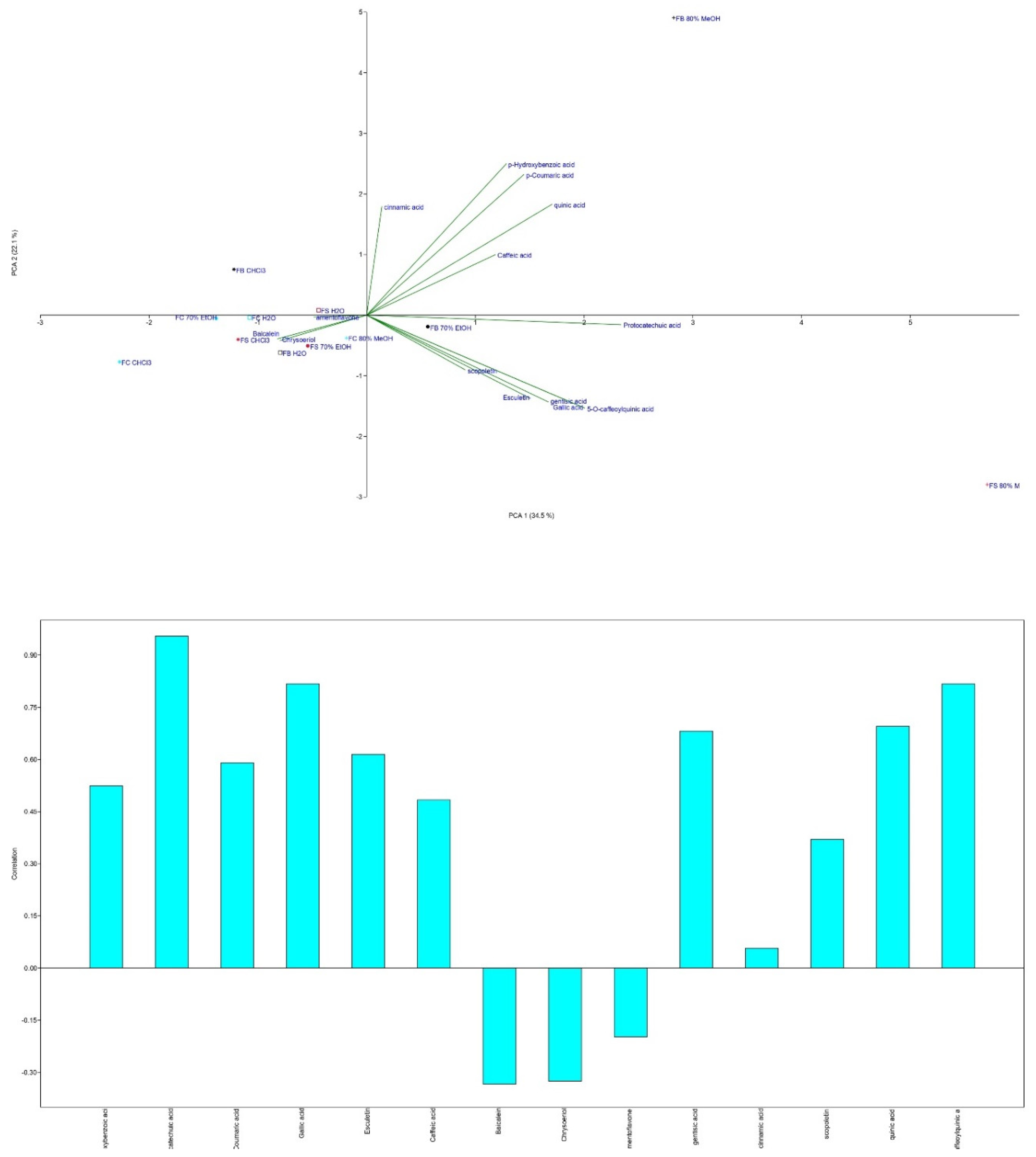

3.1.3. Phenolic Content Determined by LC-MS/MS

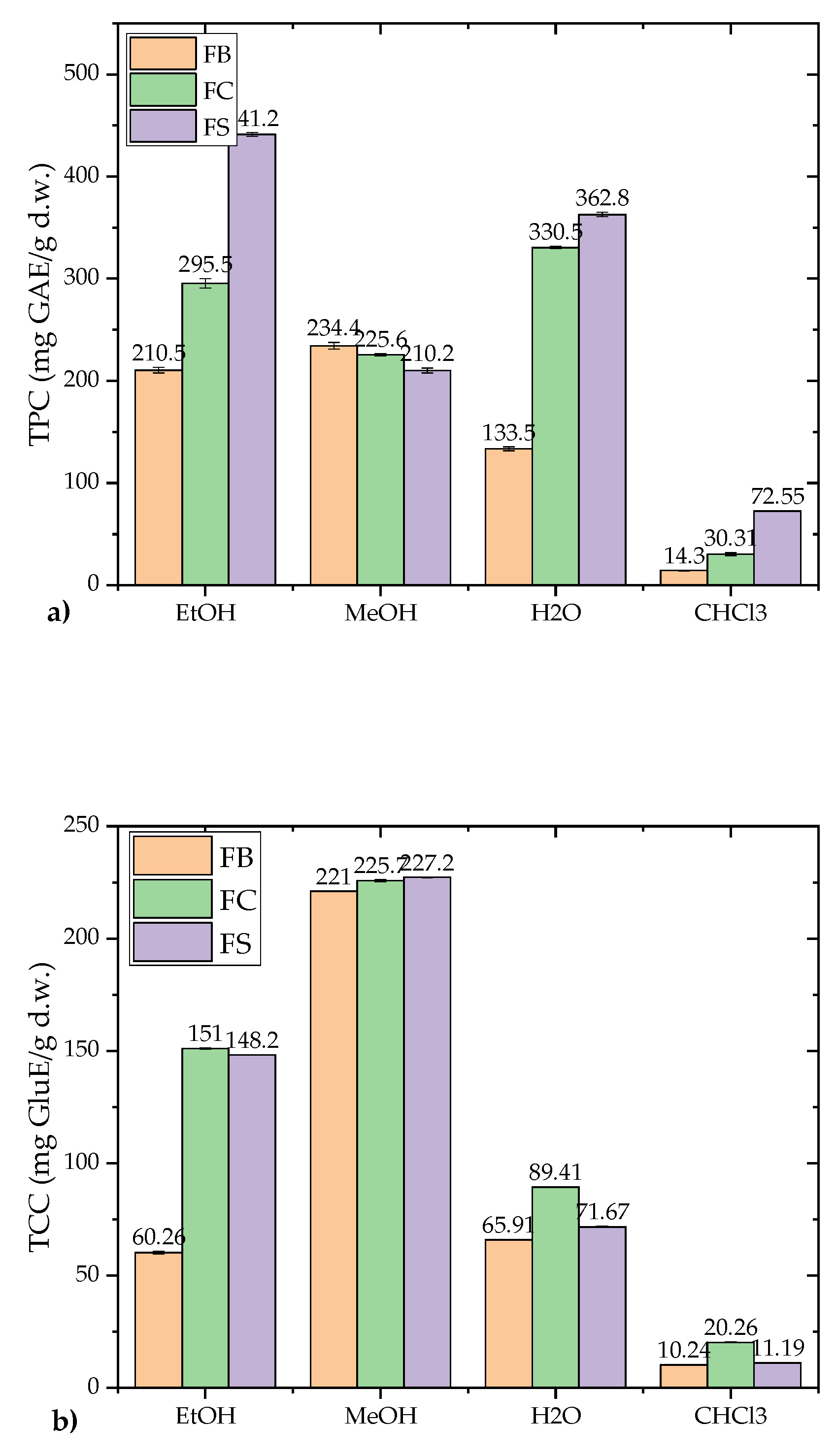

3.1.4. TPC and TCC Content

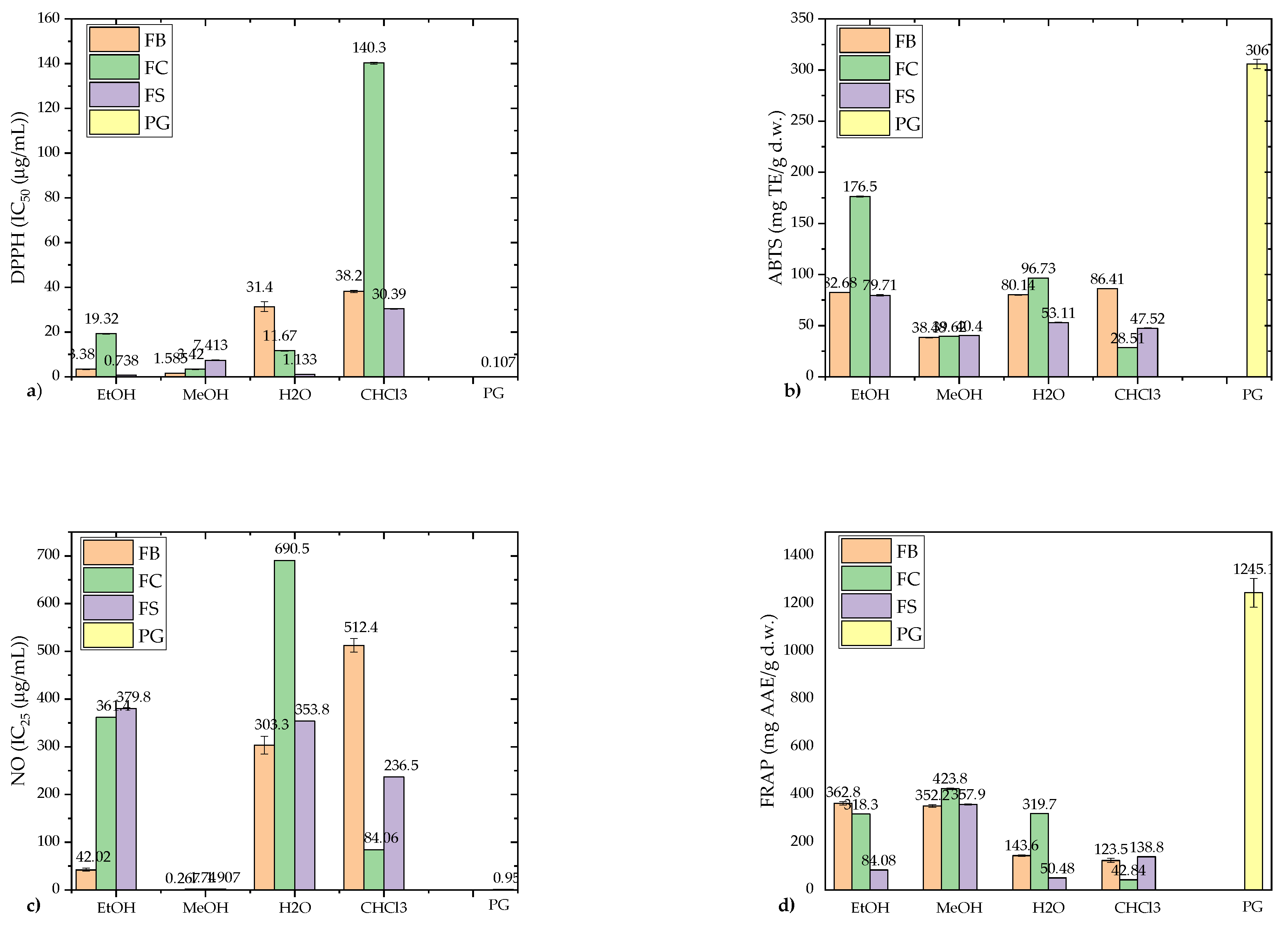

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

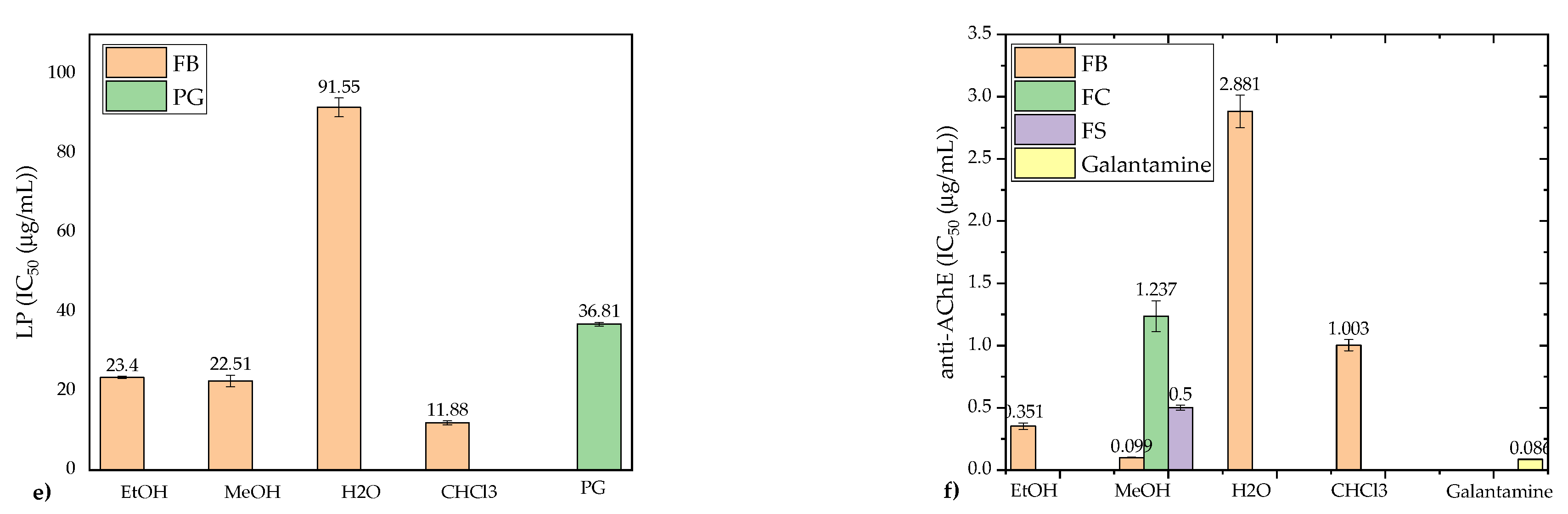

3.3. Anti-Acetylcholinesterase Activity

3.4. Antiproliferative Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FC | Fomes fomentarius strains sampled from Croatia |

| FB | Fomes fomentarius strains sampled from Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| FS | Fomes fomentarius strains sampled from Serbia |

| H2O | Hot water extract |

| EtOH | Hydroethanolic extract prepared with 70% ethanol |

| MeOH | Hydromethanolic extract prepared with 80% methanol |

| CHCl3 | Chloroform extract |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| AChE | Achetylcholinesterase |

| AAS | Atomic absorption spectrophotometry |

| HPLC-FD | High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with fluorescent detector |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass-spectrometric detection |

| PA | Polyamine |

| PUT | Putrescine |

| SPD | Spermidine |

| SPM | Spermine |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| TCC | Total carbohydrate content |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical, DPPH• |

| ABTS | 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid, ABTS•+ |

| NO | Nitric oxid radical, NO• |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| FC | Folin-Ciocalteu |

| AAE | Ascorbic acid equivalents |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents |

| GluE | Glucose equivalents |

| TE | Trolox equivalents |

| d.w. | Dry weight |

| dH2O | Distilled water |

| PG | Propyl gallate |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Gafforov, Y.; Rašeta, M.; Rapior, S.; Yarasheva, M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Wan-Mohtar, W. A. A. Q. I.; Zafar, M.; Lim, Y. W.; Wang, M.; Abdullaev, B.; Bussmann, R. W.; Zengin, G.; Chen, J. Macrofungi as medicinal resources in Uzbekistan: biodiversity, ethnomycology, and ethnomedicinal practices. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, D. Fomes fomentarius: an underexplored mushroom as source of bioactive compounds. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, I. E.; Üstün, O. Determination of total phenol content, antioxidant activity and acetylcholinesterase inhibition in selected mushrooms from Turkey. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Karaman, M.; Jakšić, M.; Šibul, F.; Kebert, M.; Novaković, A.; Popović, M. Mineral composition, antioxidant and cytotoxic biopotentials of wild-growing Ganoderma species (Serbia): G. lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst vs. G. applanatum (Pers.) Pat. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 2583–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, J.; Vrbaški, S.; Bošković, V. E.; Popović, M.; Mimica-Dukić, N. M.; Karaman, A. M. Comparison of antioxidant capacities of two Ganoderma lucidum strains of different geographical origins. Matica Srpska Journal of Natural Science 2017, 133, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Popović, M.; Beara, I.; Šibul, F.; Zengin, G.; Krstić, S.; Karaman, M. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and enzyme inhibition activities in correlation with mycochemical profile of selected indigenous Ganoderma spp. from Balkan region (Serbia). Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2000828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Mišković, J.; Čapelja, E.; Zapora, E.; Petrović Fabijan, A.; Knežević, P.; Karaman, M. Do Ganoderma species represent novel sources of phenolic based antimicrobial agents? Molecules 2023, 28, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Kebert, M.; Mišković, J.; Rakić, M.; Kostić, S.; Čapelja, E.; Karaman, M. Polyamines in edible and medicinal fungi from Serbia: a novel perspective on neuroprotective properties. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojimatov, O.K.; Gafforov, Y.; Bussmann, R.W. Ethnobiology of Uzbekistan: Ethnomedicinal Knowledge of Mountain Communities, 1st ed.; Springer Nature, Basel, Switzerland, 2023; 1564 pages.

- Grienke, U.; Zöll, M.; Peintner, U.; Rollinger, J. M. European medicinal polypores-a modern view on traditional uses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 564–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H.; Jakhar, R.; Kang, S. C. Apoptotic properties of polysaccharide isolated from fruiting bodies of medicinal mushroom Fomes fomentarius in human lung carcinoma cell line. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafforov, Y.; Kalitukha, L.; Tomšovský, M.; Angelini, P.; Venanzoni, R.; Angeles Flores, G.; Yarasheva, M.; Wan-Mohtar, W. A. A. Q. I.; Rapior, S. Fomes fomentarius (L.) Fr. – POLYPORACEAE. In Ethnobiology of Uzbekistan: Ethnomedicinal Knowledge of Mountain Communities, 1st ed.; Khojimatov, O. K., Gafforov, Y., Bussmann, R. W., Eds.; Springer Nature: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1045–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Tubić Vukajlović, J.; Djordjević, K.; Tosti, T.; Simić, I.; Grbović, F.; Milošević-Djordjević, O. In vitro effect of Lenzites betulinus mushroom against therapy-induced DNA damage in peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with acute coronary syndrome. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 335, 118640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardaweel, S. K.; Gul, M.; Alzweiri, M.; Ishaqat, A.; ALSalamat, H. A.; Bashatwah, R. M. Reactive oxygen species: The dual role in physiological and pathological conditions of the human body. Eurasian J. Med. 2018, 50, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, R. O.; Wilson, R. Essential, deadly, enigmatic: polyamine metabolism and roles in fungal cells. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2019, 33, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makletsova, M. G.; Syatkin, S. P.; Poleshchuk, V. V.; Urazgildeeva, G. R.; Chigaleychik, L. A.; Sungrapova, C. Y.; Illarioshkin, S. N. Polyamines in Parkinson’s disease: their role in oxidative stress induction and protein aggregation. J. Neurol. Res. 2019, 9 (1–2), 1–7.

- Đorđievski, S.; Vukašinović, E. L.; Čelić, T. V.; Pihler, I.; Kebert, M.; Kojić, D.; Purać, J. Spermidine dietary supplementation and polyamines level in reference to survival and lifespan of honey bees. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazirian, M.; Dianat, S.; Manayi, A.; Ziari, R.; Mousazadeh, A. R.; Habibi, E.; Saeidnia, S.; Amanzadeh, Y. Anti-inflammatory effect, total polysaccharide, total phenolics content and antioxidant activity of the aqueous extract of three basidiomycetes. Res. J. Pharmacogn. 2014, 1, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kolundžić, M.; Grozdanić, N. Đ.; Dodevska, M.; Milenković, M.; Sisto, F.; Miani, A.; Farronato, G.; Kundaković, T. Antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of wild mushroom Fomes fomentarius (L.) Fr., Polyporaceae. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 79, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, N.; Rudolf, K.; Bencsik, T.; Czégényi, D. Ethnomycological use of Fomes fomentarius (L.) Fr. and Piptoporus betulinus (Bull.) P. Karst. in Transylvania, Romania. Genetic Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasailiuk, M. V. Total flavonoid content, lipid peroxidation and total antioxidant activity of Hericium coralloides, Fomes fomentarius and Schizophyllum commune cultivated by the method of direct confrontation. Ital. J. Mycol. 2020, 49, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, Y. Optimization for the production of exopolysaccharide from Fomes fomentarius in submerged culture and its antitumor effect in vitro. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3187–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundar, A.; Okumuş, V.; Ozdemir, S.; Çelik, K. S.; Boğa, M. S.; Ozcagli, E. Determination of cytotoxic, anticholinesterase, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of some wild mushroom species. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1178060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáper, J.; Gáperová, S.; Pristaš, P.; Náplavová, K. Medicinal value and taxonomy of the tinder polypore, Fomes fomentarius (Agaricomycetes): a review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2016, 18, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gründemann, C.; Reinhardt, J. K.; Lindequist, U. European medicinal mushrooms: do they have potential for modern medicine? - An update. Phytomedicine 2020, 66, 153131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortić, M. Gljive kao lijek. Priroda: Popularni časopis hrvatskog prirodoslovnog društva 1961, 9, 272–275. [Google Scholar]

- Uzunov, B. A.; Stoyneva-Gärtner, M. P. Mushrooms and lichens in Bulgarian ethnomycology. J. Mycol. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, J.; Ivanov, M.; Stojković, D.; Glamočlija, J. Ethnomycological investigation in Serbia: astonishing realm of mycomedicines and mycofood. J. Fungi 2021, 75, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peintner, U.; Schwarz, S.; Mešić, A.; Moreau, P.; Moreno, G.; Saviuc, P. Mycophilic or mycophobic? Legislation and guidelines on wild mushroom commerce reveal different consumption behaviour in European countries. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Mišković, J.; Kebert, M.; Berežni, S.; Krstić, S.; Gojgić-Cvijović, G.; Pirker, T.; Bauer, R.; Karaman, M. Mycochemical profiles and bioactivities of Fistulina hepatica and Volvopluteus gloiocephalus from Serbia: antioxidant, enzyme inhibition, and cytotoxic potentials. Food Biosci. 2025, 66, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsecka, M.; Mleczek, M.; Siwulski, M.; Niedzielski, P. Phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus eryngii enriched with selenium and zinc. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebert, M.; Kostić, S.; Vuksanović, V.; Gavranović Markić, A.; Kiprovski, B.; Zorić, M.; Orlović, S. Metal- and organ-specific response to heavy metal-induced stress mediated by antioxidant enzymes’ activities, polyamines, and plant hormones levels in Populus deltoides. Plants 2022, 11, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramagli, S.; Biondi, S.; Torrigiani, P. Methylglyoxal(bis-guanylhydrazone) inhibition of organogenesis is not due to S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase inhibition/polyamine depletion in tobacco thin layers. Physiol. Plant. 1999, 107, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orčić, D.; Francišković, M.; Bekvalac, K.; Svirčev, E.; Beara, I.; Lesjak, M.; Mimica-Dukić, N. Quantitative determination of plant phenolics in Urtica dioica extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass-spectrometric detection. Food Chem. 2014, 143, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V. L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R. M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Espín, J. C.; Soler-Rivas, C.; Wichers, H. J. Characterization of the total free radical scavenger capacity of vegetable oils and oil fractions using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnao, M. B.; Cano, A.; Acosta, M. The hydrophilic and lipophilic contribution to total antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2001, 73, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C. E.; Wagner, D. A.; Glogowski, J.; Skipper, P. L.; Wishnok, J. S.; Tannenbaum, S. R. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite and nitrate in biological fluids. Anal. Biochem. 1982, 243, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J. Iron and free radical reactions: two aspects of antioxidant protection. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1986, 11, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I. F. F.; Strain, J. J. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid and concentration. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman, G. L.; Courtney, K. D.; Andrés, V.; Featherstone, R. M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintać, D.; Četojević-Simin, D.; Berežni, S.; Orčić, D.; Mimica-Dukić, N.; Lesjak, M. Investigation of the chemical composition and biological activity of edible grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) leaf varieties. Food Chem. 2019, 286, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. R. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65 (1–2), 55–63.

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D. A. T.; Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis version 2. 09. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, M.; Matavulj, M. Macroelements and heavy metals in some lignicolous and tericolous fungi. Matica Srpska Journal of Natural Science 2005, 108, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallikarjuna, S. E.; Ranjini, A.; Haware, D. J.; Vijayalakshmi, M. R.; Shashirekha, M.; Rajarathnam, S. Mineral composition of four edible mushrooms. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tel-Çayan, G.; Öztürk, M.; Duru, M. E.; Yabanlı, M.; Türkoğlu, A. Content of minerals and trace elements determined by ICP-MS in eleven mushroom species from Anatolia, Turkey. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2017, 44, 939–945. [Google Scholar]

- Florencio-Silva, R.; Sasso, G. R.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Simões, M. J.; Cerri, P. S. Biology of bone tissue: structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 421746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilinović, N.; Škrbić, B.; Živančev, J.; Mrmoš, N.; Pavlović, N.; Vukmirović, S. The level of elements and antioxidant activity of commercial dietary supplement formulations based on edible mushrooms. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 3170–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilinović, N.; Čapo, I.; Vukmirović, S.; Rašković, A.; Tomas, A.; Popović, M.; Sabo, A. Chemical composition, nutritional profile and in vivo antioxidant properties of the cultivated mushroom Coprinus comatus. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašeta, M.; Rakić, M.; Čapelja, E.; Karaman, M. Chapter 2: Update on Research Data on the Nutrient Composition of Mushrooms and Their Potentials in Future Human Diets. In Food chemistry, function and analysis, Edible Fungi: Chemical Composition, Nutrition and Health Effects, edition no.1; Stojković, D., Barros, L., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2022; pp. 27–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gałgowska, M.; Pietrzak-Fiećko, R. Mineral composition of three popular wild mushrooms from Poland. Molecules 2020, 25, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnusarev, S.; Mitrofanova, N.; Churakov, B. P. The effect of mixed rot from the present tinder (Fomes fomentarius (L.:Fr.) Gill.) on the accumulation of heavy metals in the hanging birch (Betula pendula Roth.). In Materialy VIII Vserossijskoj konferencii s mezhdunarodnym uchastiem «Mediko-fiziologicheskie problemy jekologii cheloveka», Ulyanovsk, Russia, 01–04 December 2021.

- Dadáková, E.; Pelikánová, T.; Kalač, P. Content of biogenic amines and polyamines in some species of European wild-growing edible mushrooms. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 230, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G. L.; Custódio, F. B.; Botelho, B. G.; Guidi, L. R.; Glória, M. B. Investigation of biologically active amines in some selected edible mushrooms. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 86, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalač, P. Health effects and occurrence of dietary polyamines: a review for the period 2005-mid 2013. Food Chem. 2014, 161, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, C.; Akgul, H.; Sevindik, M.; Akata, I.; Yumrutas, O. Determination of the anti-oxidative activities of six mushrooms. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2017, 26, 6246–6252. [Google Scholar]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Jakovljevic, D.; Todorović, N.; Vunduk, J.; Petrović, P. M.; Nikšić, M. P.; Vrvić, M. M.; Van Griensven, L. J. Antioxidants of edible mushrooms. Molecules 2015, 20, 19489–19525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaman, M.; Stahl, M.; Vulić, J.; Vesić, M.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J. Wild-growing lignicolous mushroom species as sources of novel agents with antioxidative and antibacterial potentials. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tešanović, K.; Pejin, B.; Šibul, F.; Matavulj, M.; Rašeta, M.; Janjušević, L.; Karaman, M. A comparative overview of antioxidative properties and phenolic profiles of different fungal origins: fruiting bodies and submerged cultures of Coprinus comatus and Coprinellus truncorum. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, N.; Nowak, R.; Drozd, M.; Olech, M.; Los, R.; Malm, A. Antibacterial, antiradical potential and phenolic compounds of thirty-one Polish mushrooms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, M.; Bakır, T. K.; Ünal, S. Investigation of the antioxidant and total phenolic substance of Fomes fomentarius and Ganoderma applanatum mushrooms showing therapeutic properties. Bilge International Journal of Science and Technology Research 2024, 8, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, E.; Çayan, F.; Tel-Çayan, G.; Duru, M. E. Structural characterization and determination of biological activities for different polysaccharides extracted from tree mushroom species. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltarelli, R.; Ceccaroli, P.; Iotti, M.; Zambonelli, A.; Buffalini, M.; Casadei, L.; Vallorani, L.; Stocchi, V. Biochemical characterisation and antioxidant activity of mycelium of Ganoderma lucidum from Central Italy. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On-nom, N.; Suttisansanee, U.; Chathiran, W.; Charoenkiatkul, S.; Thiyajai, P.; Srichamnong, W. Nutritional security: carbohydrate profile and folk remedies of rare edible mushrooms to diversify food and diet: Thailand case study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyashenka, S. Biological activity of Fomes fomentarius. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, 10, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkal, A. K.; Zuraik, M. M.; Ney, Y.; Nasim, M. J.; Jacob, C. Unleashing the biological potential of Fomes fomentarius via dry and wet milling. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H. A.; Ho, T. P.; Mangelings, D.; Van Eeckhaut, A.; Vander Heyden, Y.; Tran, H. T. Antioxidant, neuroprotective, and neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) differentiation effects of melanins and arginine-modified melanins from Daedaleopsis tricolor and Fomes fomentarius. BMC Biotechnol. 2024, 24, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pero, R. W.; Lund, H.; Leanderson, T. Antioxidant metabolism induced by quinic acid. increased urinary excretion of tryptophan and nicotinamide. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.H.; Kang, H.K.; Hosseindoust, A.; Mun, J.Y.; Moturi, J.; Tajudeen, H.; Lee, H.; Cheong, E.J.; Kim, J.S. Effects of scopoletin supplementation and stocking density on growth performance, antioxidant activity, and meat quality of Korean native broiler chickens. Foods 2021, 10, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Jiang, T.; Xu, J.; Xi, W.; Shang, E.; Xiao, P.; Duan, J. The relationship between polysaccharide structure and its antioxidant activity needs to be systematically elucidated. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray Stewart, T.; Dunston, T. T.; Woster, P. M.; Casero, R. A. Jr. Polyamine catabolism and oxidative damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 18736–18745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero, R. A. Jr.; Murray Stewart, T.; Pegg, A. E. Polyamine metabolism and cancer: treatments, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018, 18, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, D. E. Improving anti-neurodegenerative benefits of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease: are irreversible inhibitors the future? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A. P.; Faraoni, M. B.; Castro, M. J.; Alza, N. P.; Cavallaro, V. Natural AChE inhibitors from plants and their contribution to Alzheimer's disease therapy. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2013, 11, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borai, I. H.; Ezz, M. K.; Rizk, M. Z.; Aly, H. F.; El-Sherbiny, M.; Matloub, A. A.; Fouad, G. I. Therapeutic impact of grape leaves polyphenols on certain biochemical and neurological markers in AlCl3-induced Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 93, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khan, S.; Zargaham, M. K.; Khan, A.; Khan, S.; Hussain, A.; Uddin, J.; Khan, A.; Al-Harrasi, A. Potential therapeutic natural products against Alzheimer's disease with reference of acetylcholinesterase. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, I.; Sankhe, R.; Mudgal, J.; Arora, D.; Nampoothiri, M. Spermidine, an autophagy inducer, as a therapeutic strategy in neurological disorders. Neuropeptides 2020, 83, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, R.; Jamwal, S.; Kumar, P. A review on polyamines as promising next-generation neuroprotective and anti-aging therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 978, 176804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cör, D.; Botić, T.; Gregori, A.; Pohleven, F.; Knez, Ž. (2017). The effects of different solvents on bioactive metabolites and “in vitro” antioxidant and anti-acetylcholinesterase activity of Ganoderma lucidum fruiting body and primordia extracts. Maced. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2017, 36, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabir, N. R.; Khan, F. R.; Tabrez, S. Cholinesterase targeting by polyphenols: a therapeutic approach for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2018, 24, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budryn, G.; Majak, I.; Grzelczyk, J.; Szwajgier, D.; Rodríguez-Martínez, A.; Pérez-Sánchez, H. Hydroxybenzoic acids as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: calorimetric and docking simulation studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J. R.; de Carvalho Júnior, R. N. Polysaccharides obtained from natural edible sources and their role in modulating the immune system: biologically active potential that can be exploited against COVID-19. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Balik, M.; Szczepkowski, A.; Trepa, M.; Zengin, G.; Kała, K.; Muszyńska, B. A review of chemical composition and bioactivity studies of the most promising species of Ganoderma spp. Diversity 2023, 15, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, G. P.; Rubin, M. A.; Mello, C. F. Modulation of learning and memory by natural polyamines. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 112, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Funes, N.; Bosch-Fusté, J.; Veciana-Nogués, M. T.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M.; Vidal-Carou, M. D. In vitro antioxidant activity of dietary polyamines. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makletsova, M. G.; Rikhireva, G. T.; Kirichenko, E. Y.; Trinitatsky, I. Y.; Vakulenko, M. Y.; Ermakov, A. M. The role of polyamines in the mechanisms of cognitive impairment. J. Neurochem. 2022, 16, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gu, C.; Liu, J. Nature spermidine and spermine alkaloids: occurrence and pharmacological effects. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnyreva, A. V.; Shnyreva, A. A.; Espinoza, C.; Padrón, J. M.; Trigos, Á. Antiproliferative activity and cytotoxicity of some medicinal wood-destroying mushrooms from Russia. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2018, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendahl, A. H.; Perks, C. M.; Zeng, L.; Markkula, A.; Simonsson, M.; Rose, C.; Ingvar, C.; Holly, J. M. P.; Jernstrom, H. Caffeine and caffeic acid inhibit growth and modify estrogen receptor and insulin-like growth factor i receptor levels in human breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Class | Compound | Amount of selected compound (μg/g d.w. ± SD) | |||||||||||

| F. fomentariusand extract type | |||||||||||||

| FB | FC | FS | |||||||||||

| CHCl3 | H2O | EtOH | MeOH | CHCl3 | H2O | EtOH | MeOH | CHCl3 | H2O | EtOH | MeOH | ||

| Flavones | Baicalein | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | 213.9 ± 42.78a | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | 147.5 ± 29.50b | 44.63 ± 8.926c | <12.2 |

| Chrysoeriol | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | 3.410 ± 0.102a | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | |

| Biflavonoid | Amentoflavone | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | 10.97 ± 0.329a | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 | <3.05 |

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | <6.1 | <6.1 | 32.79 ± 1.967c | 420.0 ± 25.20a | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | 56.03 ± 3.362b |

| Protocatechuic acid | <6.1 | <6.1 | 10.90 ± 0.872c | 13.28 ± 1.062b | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | 25.48 ± 2.038a | |

| Gentisic acid | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | 15.91 ± 1.273b | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | 22.46 ± 1.797a | |

| Gallic acid | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | 15.30 ± 1.377a | |

| Cinnamic acid | 179.9 ± 35.98a | <97.5 | <97.5 | 106.1 ± 21.22b | <97.5 | <97.5 | <97.5 | <97.5 | <97.5 | <97.5 | <97.5 | <97.5 | |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | p-Coumaric acid | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | 83.12 ± 7.481a | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | <12.2 | 19.23 ± 1.731b |

| Caffeic acid | <6.1 | <6.1 | 22.18 ± 1.553e | 83.36 ± 5.835b | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | 6.95 ± 0.438f | <6.1 | 105.95 ± 7.416a | 63.32 ± 4.432c | 49.23 ± 3.446d | |

| Coumarins | Esculetin | <6.1 | 51.36 ± 3.082b | 73.66 ± 4.420a | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | 84.03 ± 5.042a |

| Scopoletin | <6.1 |

<6.1 |

9.770 ± 0.782g | 88.02 ± 7.042e | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | 23.63 ± 1.890f | 209.1 ± 16.73d | 511.7 ± 40.94c | 853.1 ± 68.25a | 580.8 ± 46.46b | |

| Cyclohexanecarboxylic acid | Quinic acid | <48.85 |

58.99 ± 5.589g | 414.2 ± 41.42c | 996.8 ± 99.68a | <48.85 | 207.5 ± 20.75f | 211.7 ± 21.17f | 379.3 ± 37.93d | <48.85 | 247.8 ± 24.78e | <48.85 | 454.2 ± 45.42b |

| Chlorogenic acid | 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | <6.1 | 6.740 ± 0.337a |

| Total | 179.88 | 110.35 | 563.48 | 1790.69 | 217.28 | 207.49 | 222.70 | 425.77 | 209.05 | 1012.91 | 961.02 | 1313.49 | |

| Cell line | Extract concentration (μg/mL) | Growth inhibition (% ± SEM) | |||||

| FB | FC | FS | |||||

| H2O | EtOH | MeOH | CHCl3 | MeOH | MeOH | ||

| MDA-MB-231 | 50 | 12.77±3.30d | 29.15±1.58c | 74.17±0.34a | < 10* | 12.83±0.59d | 46.55±1.79b |

| 100 | 13.05±2.57d | 89.06±0.87b | 94.98±0.78a | < 10* | 51.39±0.77c | 91.39±0.83b | |

| MCF-7 | 50 | 29.17±3.44e | 65.84±2.35c | 85.23±0.50a | 38.14±2.50d | 60.99±1.30c | 75.88±0.78b |

| 100 | 70.97±3.10e | 91.34±0.86c | 95.96±0.36a | 49.22±1.52f | 80.84±0.72d | 93.42±0.57b | |

| T47D | 50 | 17.45±2.08e | 55.38±0.72b | 51.51±1.50cd | 49.19±1.33d | 53.06±0.72bc | 68.55±0.94a |

| 100 | 20.72±1.80e | 78.62±0.83b | 82.80±1.58a | 68.40±1.19c | 63.59±1.12d | 80.79±0.90ab | |

| A2780 | 50 | < 10 | 91.12±0.43c | 100.30±0.36a | 25.07±3.29e | 69.20±1.66d | 96.35±0.72b |

| 100 | 36.95±3.79c | 100.50±0.33a | 99.94±0.34a | 52.43±0.99b | 100.20±0.31a | 99.21±0.47a | |

| SiHa | 50 | 16.44±2.02e | 66.97±0.33b | 93.13±0.92a | 44.56±1.62d | 51.43±2.86c | 68.77±0.31b |

| 100 | 20.09±1.58d | 95.42±0.76a | 95.75±0.48a | 43.25±1.82c | 73.51±1.26b | 93.13±1.02a | |

| HeLa | 50 | 15.46±2.47e | 50.25±2.04c | 60.86±3.10b | 36.87±0.54d | 62.75±2.12b | 68.69±1.35a |

| 100 | 27.81±1.07e | 92.80±3.38a | 96.31±0.50a | 50.79±1.50d | 70.31±2.96c | 82.82±2.48b | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).