Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

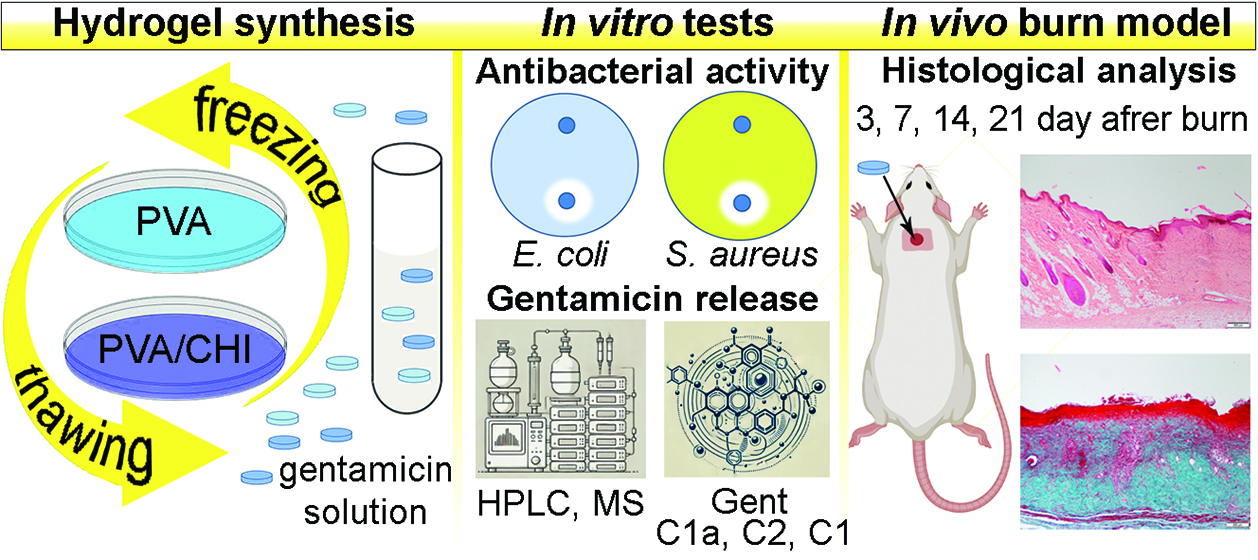

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

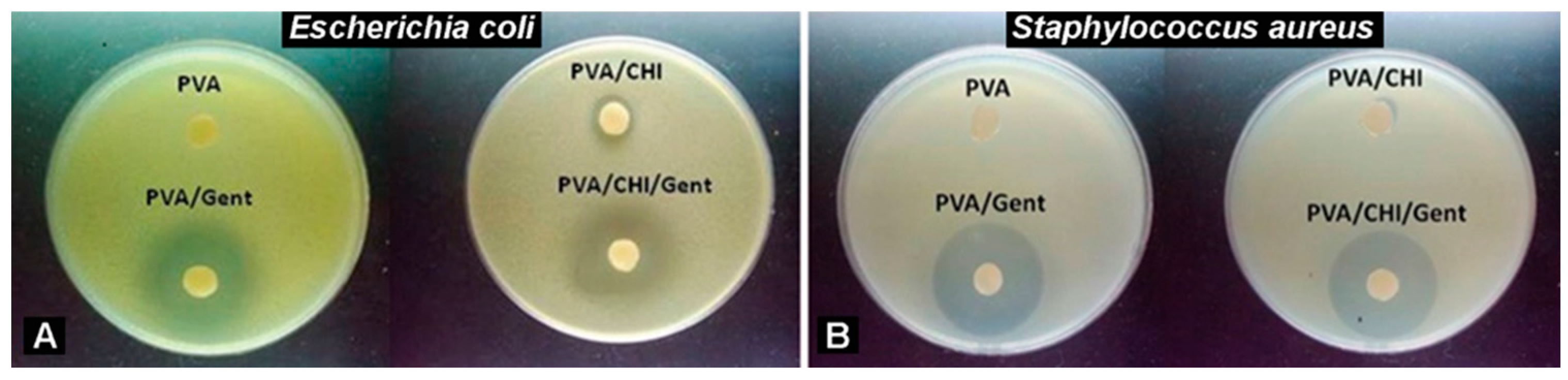

2.1. Antibacterial Activity

2.2. Gentamicin Release

2.3. In Vivo Testing

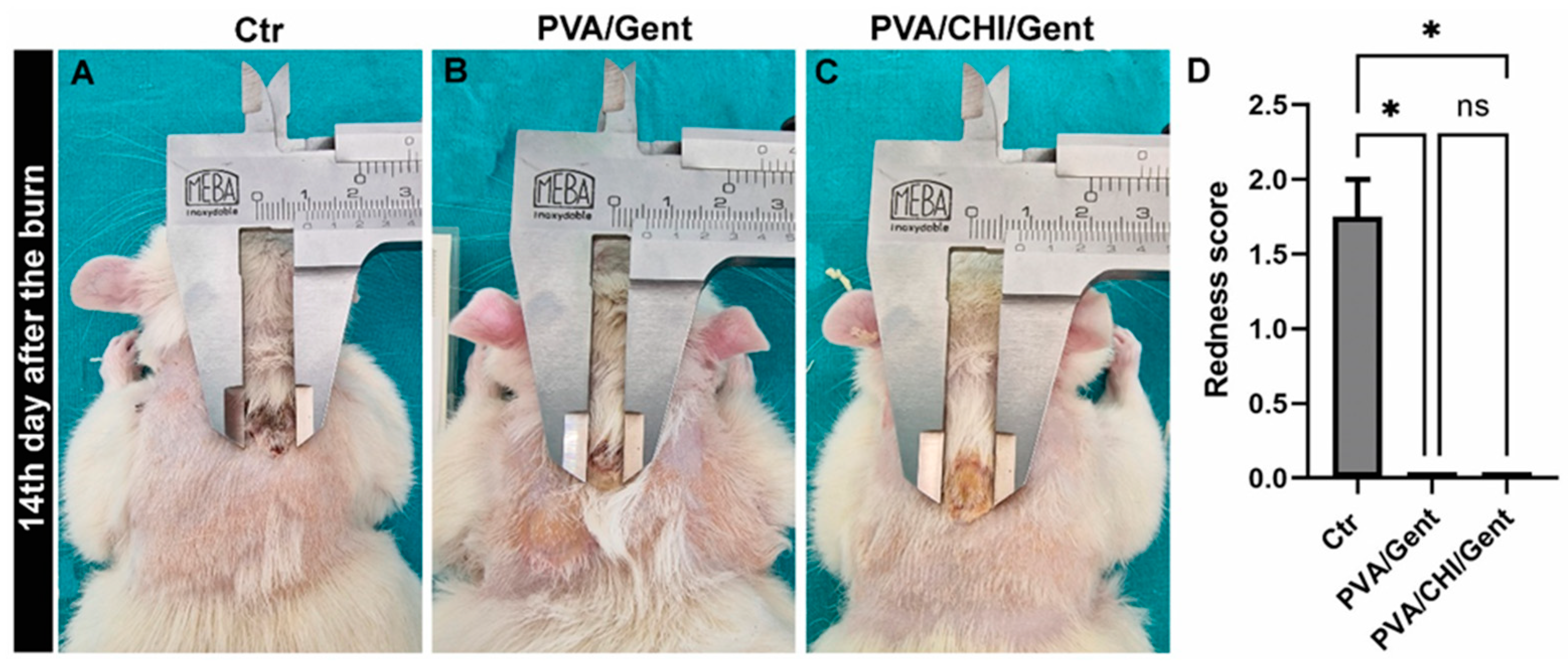

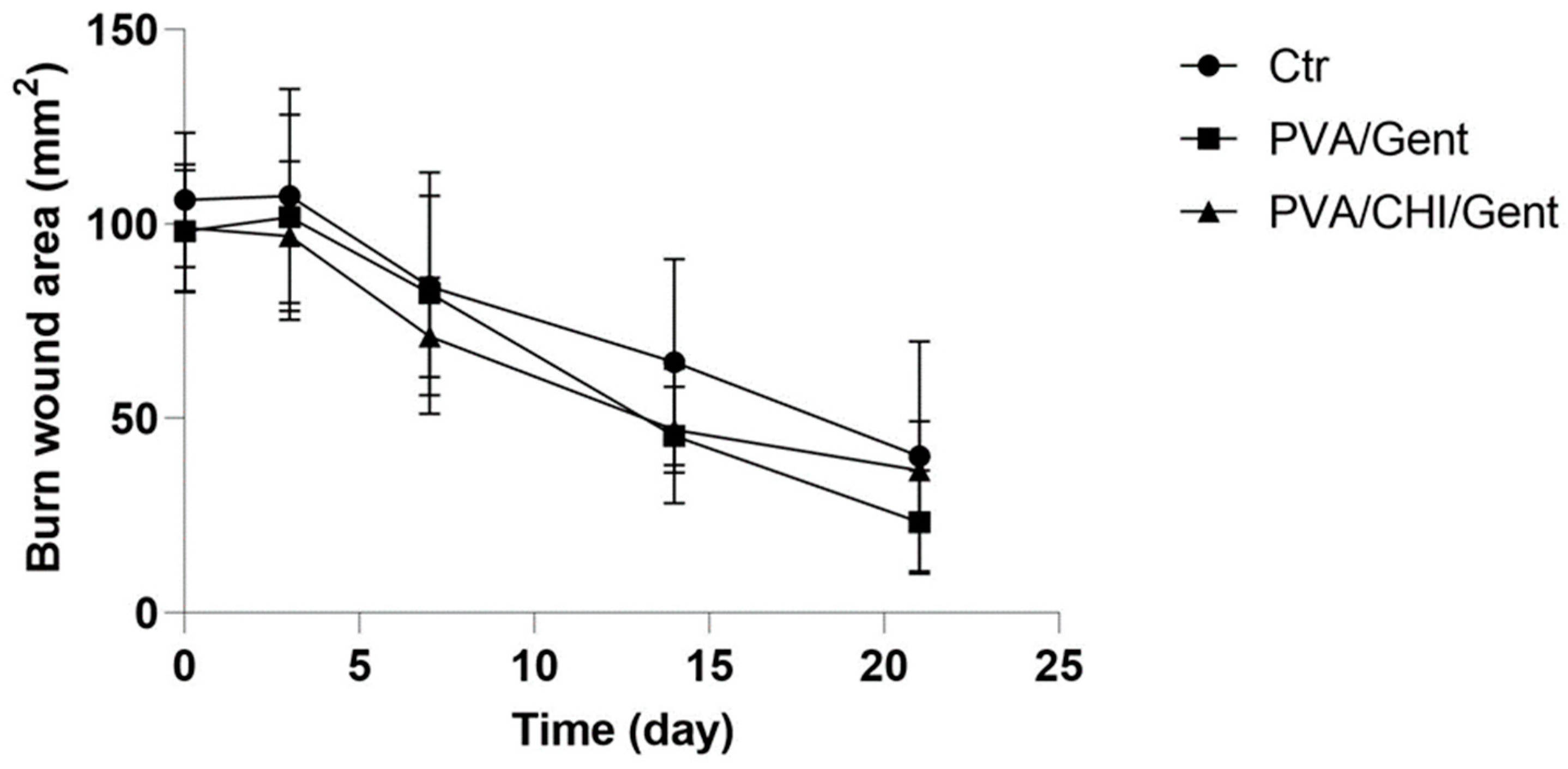

2.4. Clinical evaluations of the burn wound and wound contraction

2.5. Histological Analysis

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.1.1. Synthesis of PVA/Gent Hydrogel

4.1.2. Synthesis of PVA/CHI/Gent Hydrogel

4.1.3. Antibacterial Activity

4.1.4. Gentamicin Release

4.2. Animals

4.2.1. Experimental Design

4.2.2. Histological Analysis

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baglio, S.R.; Pegtel, D.M.; Baldini, N. Mesenchymal stem cell secreted vesicles provide novel opportunities in (stem) cell-free therapy. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gantwerker, E.A.; Hom, D.B. Skin: histology and physiology of wound healing. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2012, 39, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Shu, W.; Yu, Q.; Qu, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, R. Functional biomaterials for treatment of chronic wound. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2020, 8, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Baker, A.B. Biomaterials and nanotherapeutics for enhancing skin wound healing. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2016, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickelson, M.A.; Mans, C.; Colopy, S.A. Principles of Wound Management and Wound Healing in Exotic Pets. Ve.t Clin. North. Am. – Exot. Anim. Pract. 2016, 19, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebhodaghe, S.O. Hydrogel–based biopolymers for regenerative medicine applications: a critical review. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2022, 71, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderibigbe, B.; Buyana, B. Alginate in wound dressings. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, A.; Tian, W.X.; Farooq, M.A.; Khan, D.H. An overview of hydrogels and their role in transdermal drug delivery. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2021, 70, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanshan, J.; Newton, M.A.A.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, W.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, Z.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, J. Progress of Hydrogel Dressings with Wound Monitoring and Treatment Functions. Gels 2023, 9, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suflet, D.M.; Popescu, I.; Pelin, I.M.; Ichim, D.L.; Daraba, O.M.; Constantin, M.; Fundueanu, G. Dual cross-linked chitosan/PVA hydrogels containing silver nanoparticles with antimicrobial properties. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lužajić Božinovski, T.; Todorović, V.; Milošević, I.; Prokić, B.B.; Gajdov, V.; Nešović, K.; Mišković-Stanković, V.; Marković, D. Macrophages, the main marker in biocompatibility evaluation of new hydrogels after subcutaneous implantation in rats. J. Biomater. Appl. 2022, 36, 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamloo, A.; Aghababaie, Z.; Afjoul, H.; Jami, M.; Bidgoli, M.R.; Vossoughi, M.; Ramazani, A.; Kamyabhesari, K. Fabrication and evaluation of chitosan/gelatin/PVA hydrogel incorporating honey for wound healing applications: An in vitro, in vivo study. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 2021, 592, 120068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, M.; Nokhodchi, A. An overview on antimicrobial and wound healing properties of ZnO nanobiofilms, hydrogels, and bionanocomposites based on cellulose, chitosan, and alginate polymers. Carbohyd. Polym. 2020, 227, 115349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, A.E.; Chircov, C.; Grumezescu, A.M. Nanomaterials for Wound Dressings: An Up-to-Date Overview. Molecules 2020, 25, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Kong, S.; Ouyang, Q.; Li, C.; Hou, T.; Chen, Y.; Li, S. Chitosan-Gentamicin Conjugate Hydrogel Promoting Skin Scald Repair. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannuccelli, V.; Maretti, E.; Bellini, A.; Malferrari, D.; Ori, G.; Montorsi, M.; Bondi, M.; Truzzi, E.; Leo, E. Organo-modified bentonite for gentamicin topical application: Interlayer structure and in vivo skin permeation. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 158, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, H.K.; Park, N.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Meyers, S.P. Antibacterial activity of chitosans and chitosanoligomers with different molecular weights. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 74, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumar, P.; Rohilla, A.; Thangathirupathi, A. Gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity: Do we have a promising therapeutic approach to blunt it? Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 62, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forge, A.; Schacht, J. Aminoglycoside antibiotics. Audiol. Neurotol. 2000, 5, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, N.; Martins, M.; Martins, A.; Fonseca, N.A.; Moreira, J.N.; Reis, R.L.; Neves, N.M. Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanofiber meshes with liposomes immobilized releasing gentamicin. Acta Biomater. 2015, 18, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalavras, C.G.; Patzakis, M.J.; Holtom, P. ; Local Antibiotic Therapy in the Treatment of Open Fractures and Osteomyelitis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. R. 2004, 427, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mišković-Stanković, V.; Janković, A.; Grujić, S.; Matić-Bujagić, I.; Radojević, V.; Vukašinović-Sekulić, M.; Kojić, V.; Djošić, M.; Atanacković, T.M. Diffusion models of gentamicin released in poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan hydrogel. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2024, 89, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, S. Structural origins of gentamicin antibiotic action. EMBO J 1998, 17, 6437–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makoid, M. C.; Dufour, A.; Banakar U., V. Modelling of Dissolution Behaviour of Controlled Release Systems. S.T.P. Pharma Pratiques 1993, 3, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Korsmeyer, R.W.; Gurny, R.; Doelker, E.; Buri, P.; Peppas, N.A. Mechanisms of Solute Release from Porous Hydrophilic Polymers. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 1983, 15, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopcha, M.; Lordi, N.G.; Tojo, K.J. Evaluation of Release from Selected Thermosoftening Vehicles. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1991, 43, 382–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritger, P.L.; Peppas, N.A. A Simple Equation for Description of Solute Release I. Fickian and Non-Fickian Release from Non-Swellable Devices in the Form of Slabs, Spheres, Cylinders or Discs. J. Control. Release 1987, 5, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišković-Stanković, V.; Atanackovic, T. Novel antibacterial biomaterials for medical applications and modeling of drug release process, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis/CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2024; pp. 1–288, https://www.routledge.com/Novel-Antibacterial-Biomaterials-for-Medical-Applications-and-Modeling-of-Drug-Release-Process/Miskovic-Stankovic-Atanackovic/p/book/9781032668864. [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren, G.; Sletten, G.; Dahl, E.J. Cytotoxicity of dental alloys, metals, and ceramics assessed by Millipore filter, agar overlay, and MTT tests. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000, 84, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares Pereira, D.D.S.; Lima-Ribeiro, M.H.M.; de Pontes-Filho, N.T.; Carneiro-Leão, A.M.D.A.; Correia, M.T.D.S. Development of animal model for studying deep second-degree thermal burns. BioMed Res. Int. 2012, 1, 460841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkovska, J.; Djurdjevic, Z.; Jancic, I.; Bufan, B.; Milenkovic, M.; Jankovic, R.; Mišković-Stanković, V.; Obradovic, B. Comparative in vivo evaluation of novel formulations based on alginate and silver nanoparticles for wound treatments. J. Biomater. Appl. 2018, 32, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, C.; Samdanci, E.; Erbatur, S.; Aytekin, A.H.; Ak, M.; Turtay, M.G.; Coban, Y.K. β-Glucan treatment prevents progressive burn ischaemia in the zone of stasis and improves burn healing: an experimental study in rats. Burns 2013, 39, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gal, P.; Kilik, R.; Mokry, M.; Vidinsky, B.; Vasilenko, T.; Mozes, S.; Bobrov, N.; Tomori, Z.; Bober, J.; Lenhardt, L. Simple method of open skin wound healing model in corticosteroid-treated and diabetic rats: standardization of semi-quantitative and quantitative histological assessments. Vet. Med-Czech 2008, 53, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.S.; Albuquerque Jr, R.L.; Cavalcante, D.R.; Dantas, M.D.M.; Cardoso, J.C.; Bezerra, M.S.; Souza, J.C.C.; Serafini, M.R.; Quitans, L.J.; Bonjardim Jr, L.R.; Araújo, A.A.S. Collagen-based films containing liposome-loaded usnic acid as dressing for dermal burn healing. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabol, F.; Dancakova, L.; Gal, P.; Vasilenko, T.; Novotny, M.; Smetana, K.; Lenhardt, L. Immunohistological changes in skin wounds during the early periods of healing in a rat model. Vet. Med-Czech 2012, 57, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedgui, A. Focus on inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 958–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.C.F.; Ng, T.B.; Wong, J.H.; Chan, W.Y. Chitosan: An update on potential biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5156–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhu, X.K.; Xue, X.T.; Wu, D.Y. Hydrogel sheets of chitosan, honey and gelatin as burn wound dressings. Carbohyd. Polym. 2012, 88, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Ling, P.X.; He, Y.L.; Zhang, T.M. Effects of chitosan and heparin on early extension of burns. Burns 2007, 33, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Hadisi, Z.; Ismail, A.F.; Aziz, M.; Akbari, M.; Berto, F.; Chen, X.B. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of chitosan-alginate/gentamicin wound dressing nanofibrous with high antibacterial performance. Polym. Test. 2020, 82, 106298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.R.; Kim, J.O.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.I.; Kim, J.H.; Chang, S.W.; Jin, S.G.; Kim, J.A.; Lyoo, W.S.; Han, S.S.; Ku, S.K.; Yong, C.S.; Choi, H.G. Gentamicin-loaded wound dressing with polyvinyl alcohol/dextran hydrogel: gel characterization and in vivo healing evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, G.D.; Scales, J.T. Effect of air drying and dressings on the surface of a wound. Nature 1963, 197, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodja, A.N.; Mahlous, M.; Tahtat, D.; Benamer, S.; Youcef, S.L.; Chader, H.; Mouhoub, L.; Sedgelmaci, M.; Ammi, N.; Mansouri, M.B.; Mameri, S. Evaluation of healing activity of PVA/chitosan hydrogels on deep second degree burn: pharmacological and toxicological tests. Burns 2013, 39, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankari, L.; Fernandes, B.; Rebelatto, C.; Brofman, P. Evaluation of PVA hydrogel as an extracellular matrix for in vitro study of fibroblast proliferation. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2019, 69, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diller, R.B.; Tabor, A.J. The Role of the Extracellular Matrix (ECM) in Wound Healing: A Review. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.; Lin, E.J.; Tartar, D. Immunology of Wound Healing. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2018, 7, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, T.; Tanaka, M.; Huang, Y.Y.; Hamblin, M.R. ; Chitosan preparations for wounds and burns: antimicrobial and wound-healing effects. Expert Rev. Anti-Infe. 2011, 9, 857–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bārzdiņa, A.; Plotniece, A.; Sobolev, A.; Pajuste, K.; Bandere, D.; Brangule, A. From Polymeric Nanoformulations to Polyphenols—Strategies for Enhancing the Efficacy and Drug Delivery of Gentamicin. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potara, M.; Jakab, E.; Damert, A.; Popescu, O.; Canpean, V.; Astilean, S. Synergistic antibacterial activity of chitosan-silver nanocomposites on Staphylococcus aureus. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 135101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Okamoto, Y.; Kojima, K.; Miyatake, K.; Fujise, H.; Shigemasa, Y.; Minami, S. Effects of chitin and chitosan on collagen synthesis in wound healing. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2004, 66, 1595–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.; Djošić, M.; Janković, A.; Kojić, V.; Stojanović, J.; Grujić, S.; Matić Bujagić, I.; Rhee, K.Y.; Mišković-Stanković, V. The Chitosan-Based Bioactive Composite Coating on Titanium. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 4461–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).