2.1. Background

Due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2), the global average surface temperature (both land and sea) of the earth increased; and this rise reached about 1.2 °C in 2020 compared to 1850 as a baseline for the pre-industrial periods (Marzouk, 2021; Matthews and Wynes, 2022; Meinshausen et al., 2022; Marzouk, 2022). In relation to this, the global average atmospheric CO2 concentration in 2020 reached 415 ppm (parts per million), compared to its pre-industrial level of 285 ppm, around 1850 (Chen, 2021). When the average temperature increases by an amount, the local temperature (especially on the land rather than the sea) may actually increase by a multiple of that amount. Thus, the relatively small amount of the average surface temperature rise can be misleading in terms of describing the size of the global warming problem (NASA, 2024; IPCC, 2024), which extends to the broader problem of climate change through altered pattern of other climate variables besides the temperature (Vitousek, 1994). In order to properly combat CO2 emissions that cause global warming, it is important to understand the dependence of these CO2 emissions on their source activities, such as electricity generation and industrial processes.

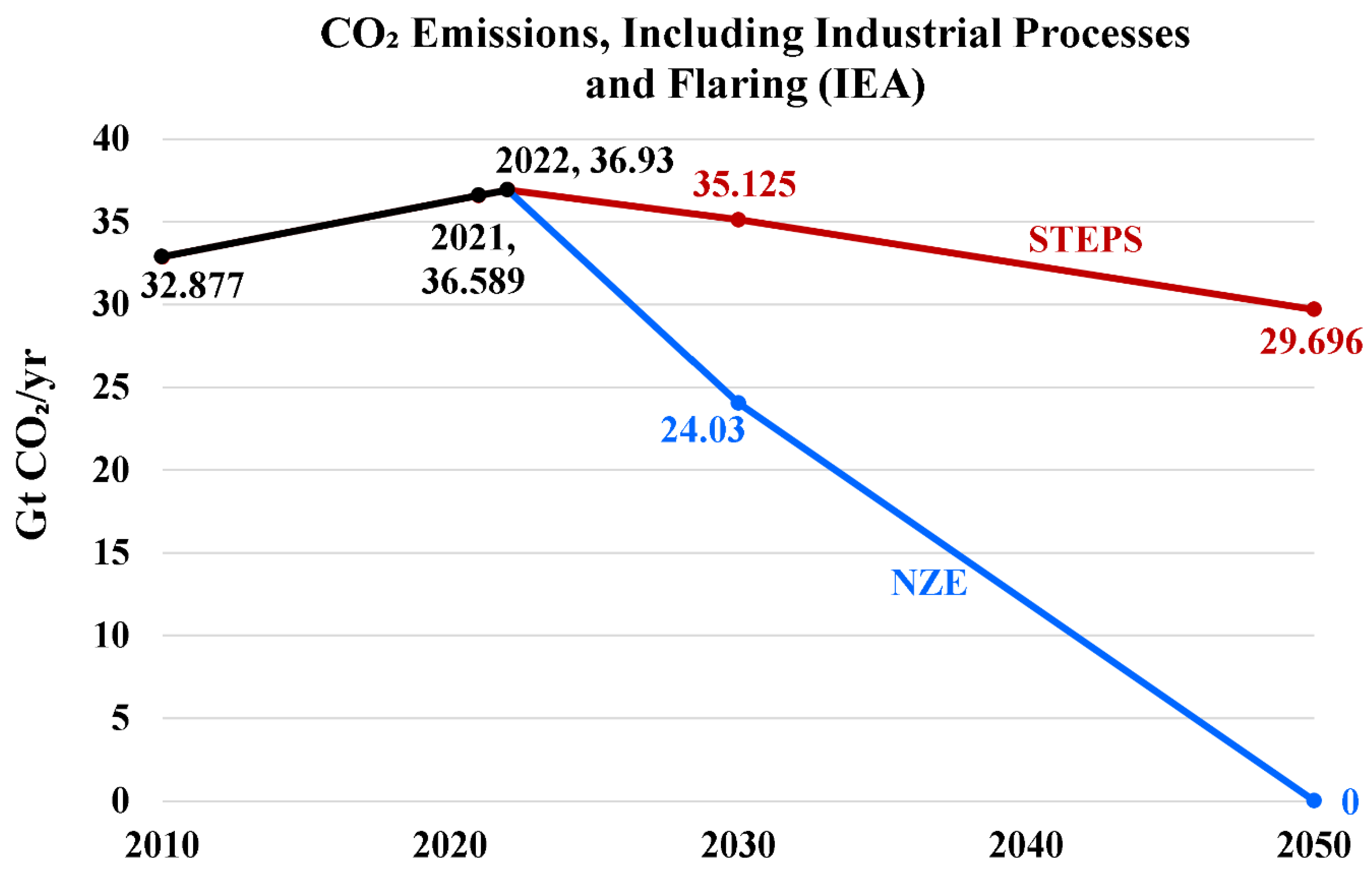

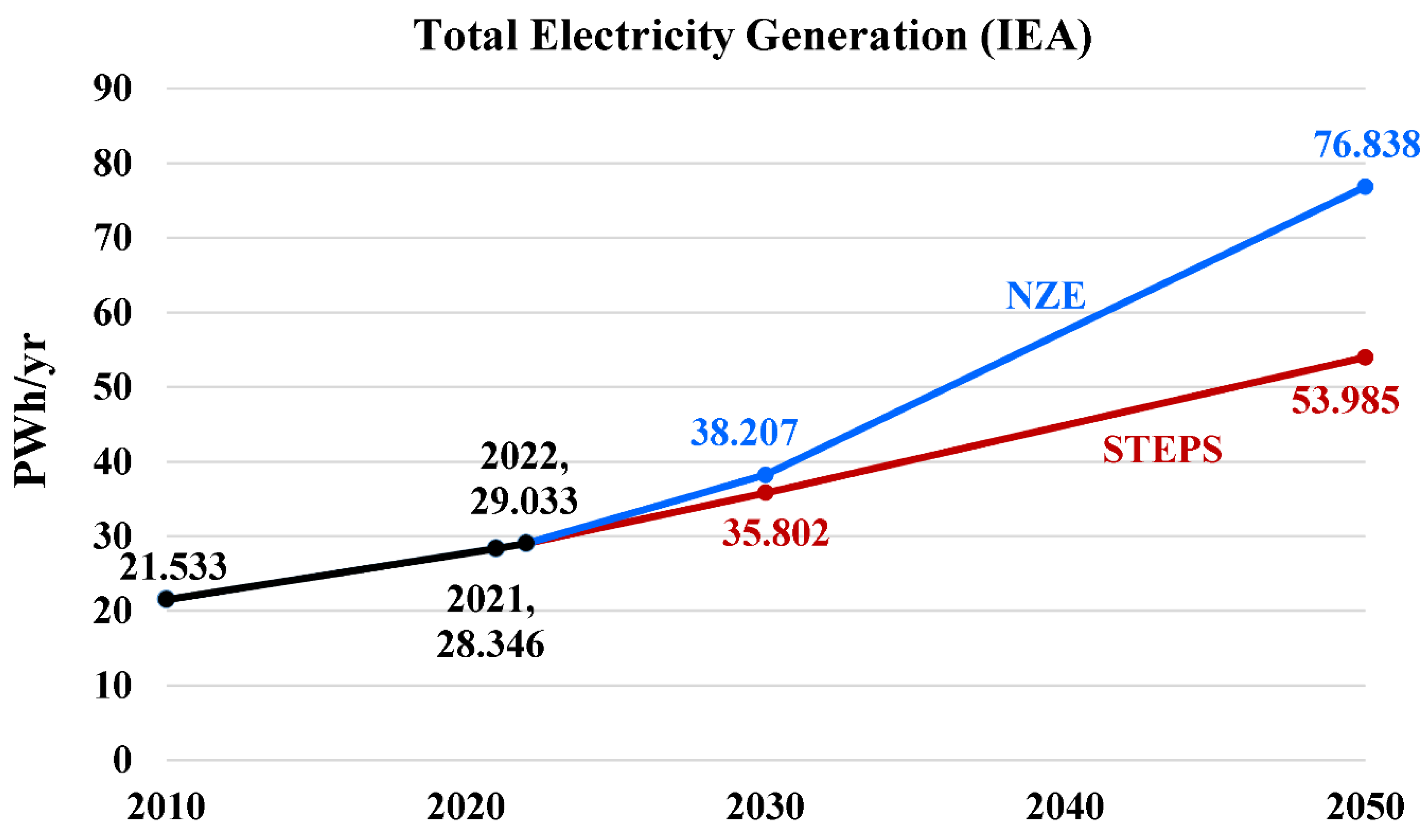

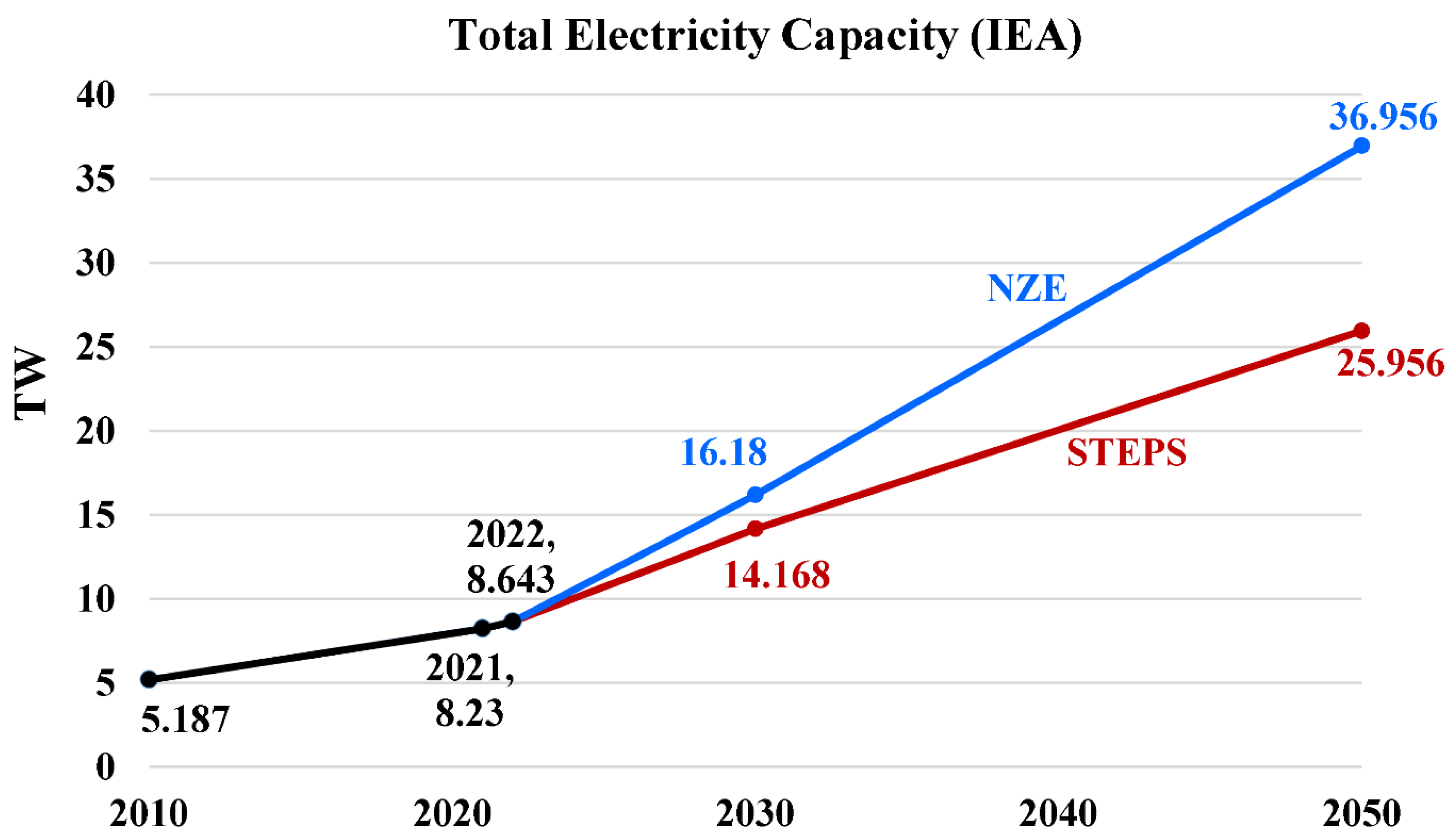

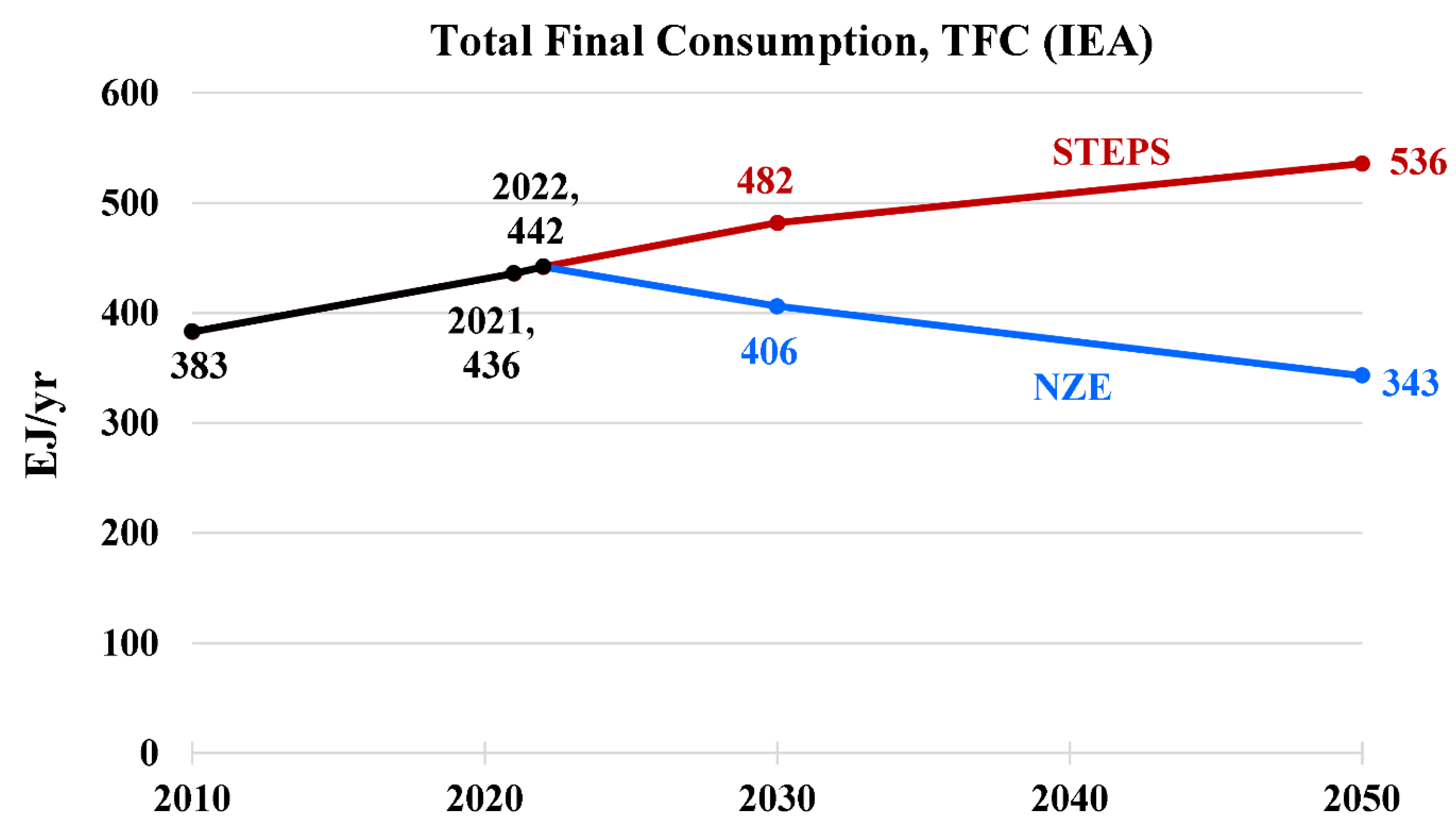

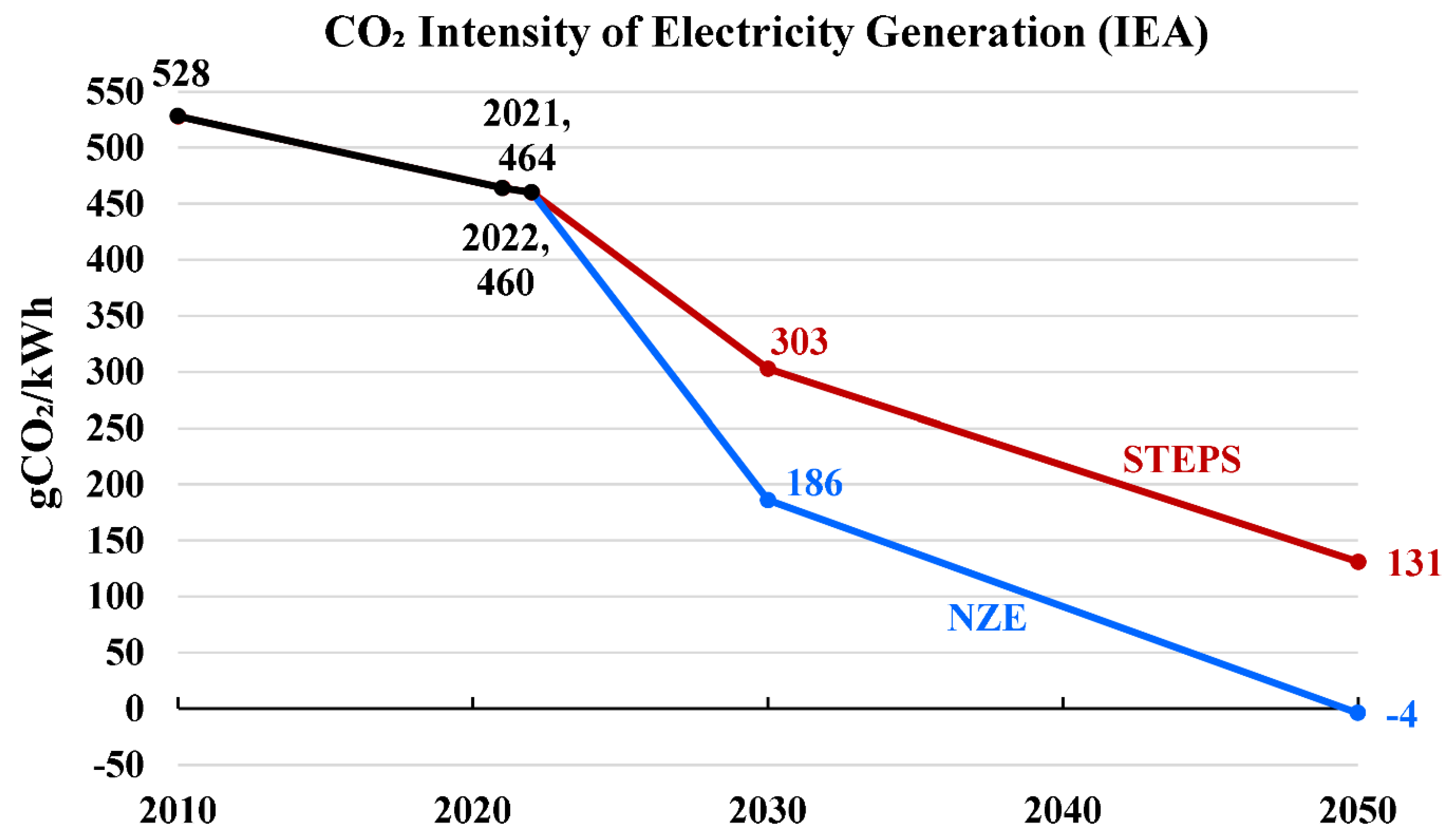

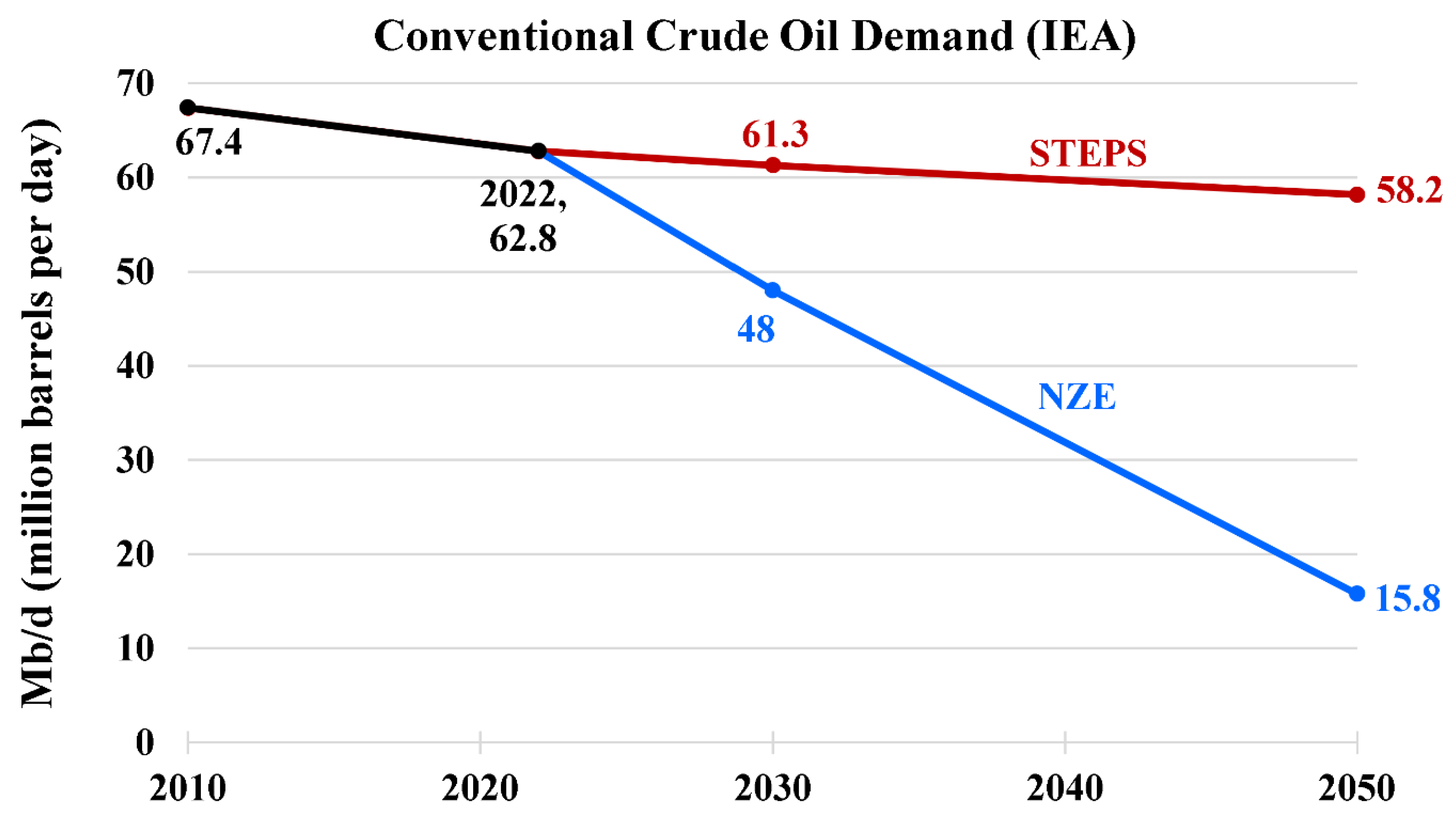

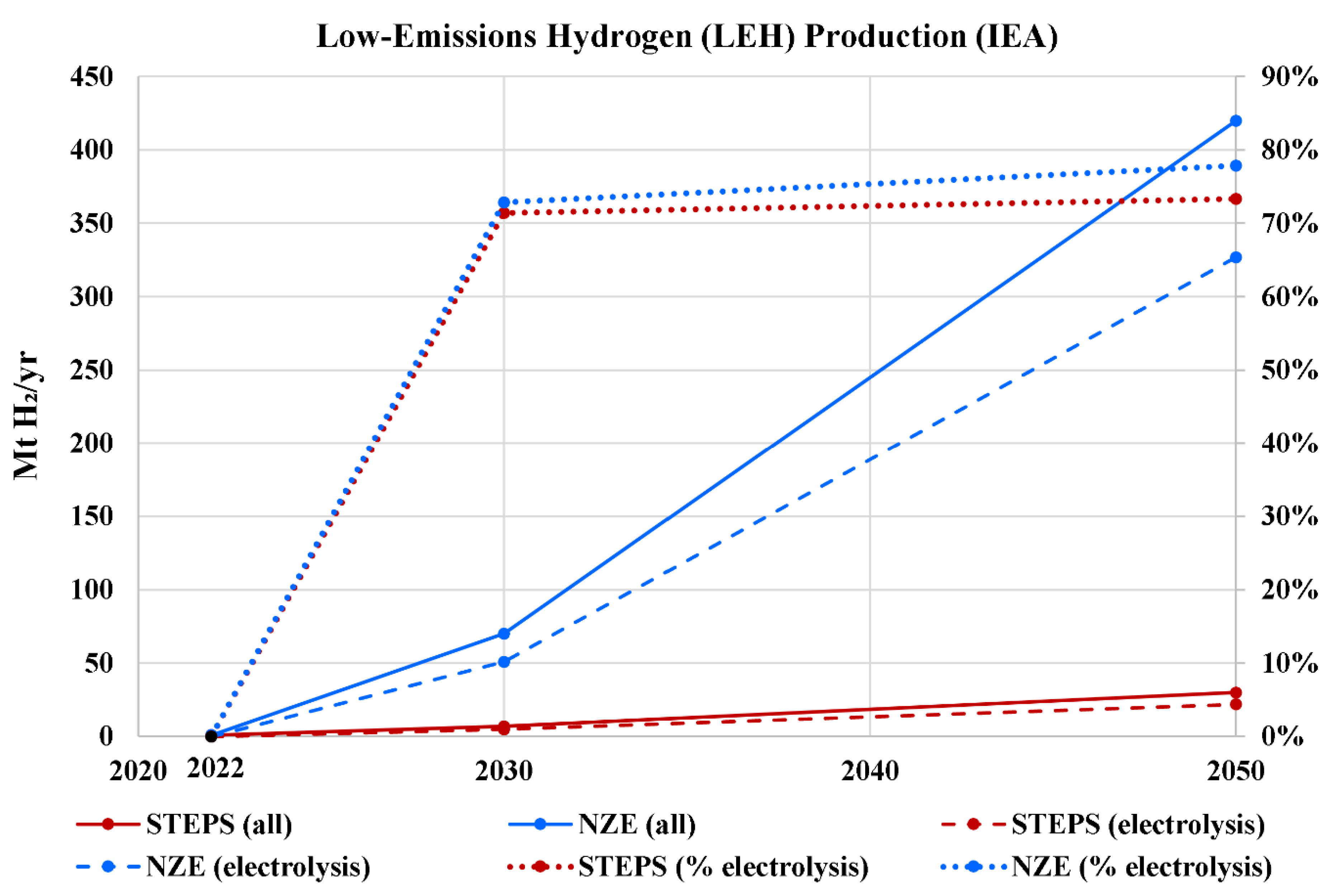

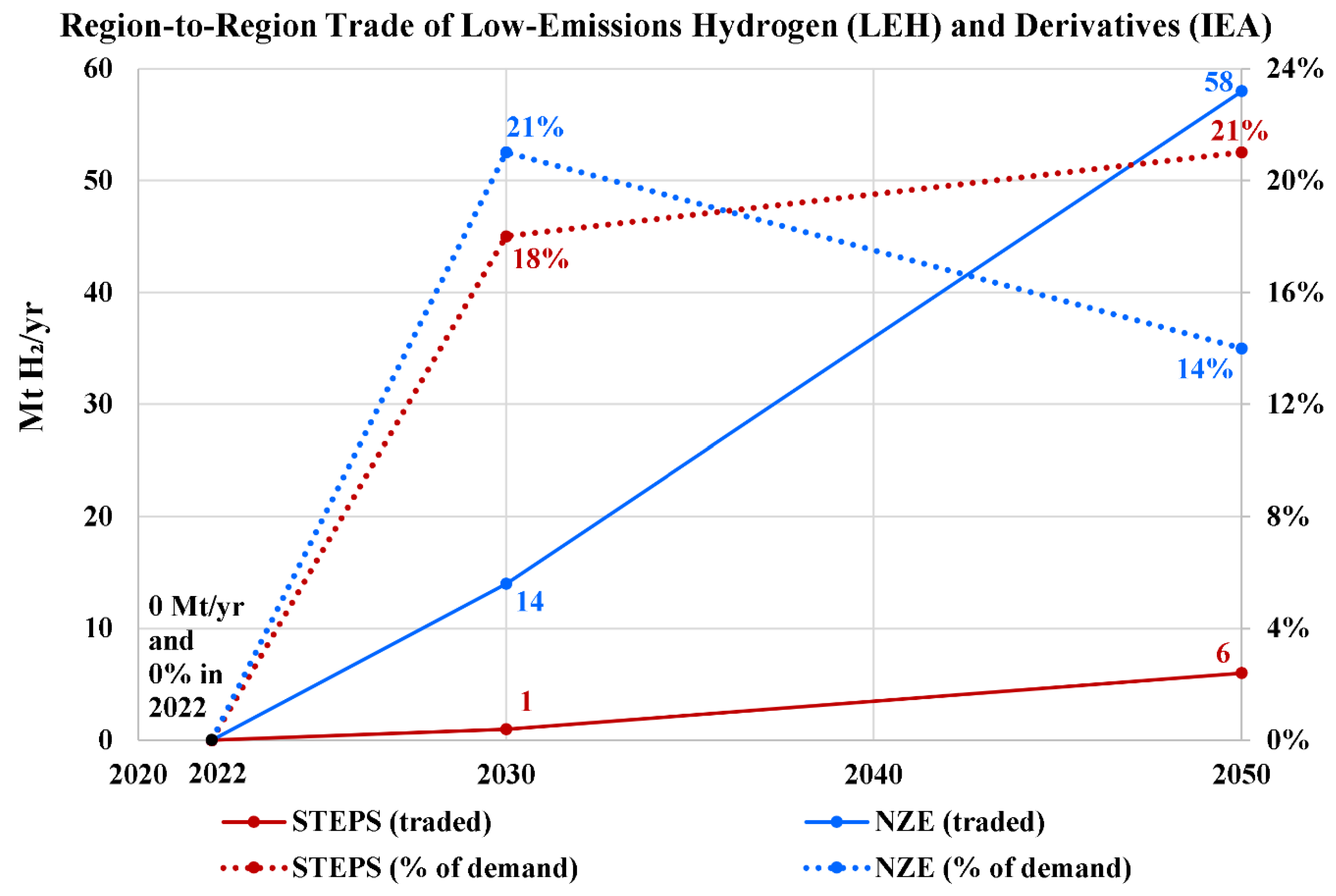

The International Energy Agency (IEA) adopts the Global Energy and Climate (GEC) model as a large-scale simulation tool to replicate how energy markets function and to generate detailed long-term scenarios for the global energy system as well as the dependent emissions. The IEA’s GEC model replaced in 2021 a couple of older models that used to be implemented in parallel to each other, which are the IEA’s World Energy Model (WEM), and the IEA’s Energy Technology Perspectives (ETP) model (IEA, 2023a). The specific energy-emissions scenarios (or pathways) covered by GEC include (1) the Stated Policies Scenario, or Stated Energy Policies Scenario (STEPS) and (2) the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario (NZE). STEPS predicts the direction of energy system progression assuming that the current policies remain in action and no additional mitigating changes are seriously taken to curb the climate change through limiting energy-based and process-based emissions (IEA, 2023b). Such type of forecasting that has a clear starting point and a clear assumption that guides the progression path but does not aim to reach a specific target is described as "exploratory". On the other hand, NZE shows a predicted set of changes for the global energy sector that enable reaching the global target of net zero CO2 emissions by 2050. Additionally, NZE is consistent with limiting the global average temperature rise to 1.5 °C, with at least a 50% probability (IEA, 2023c). Such type of forecasting that has a clear starting point and a clear end point (target), while it predicts a path to reach that target is described as "normative". The World Energy Outlook (WEO) is an annual public report published by IEA, where modeling is used to provide in-depth analysis for different aspects of the global energy system. Although an edition of WEO was published in 1977, it became a regular annual publication in 1998 (IEA, 2023d; FAO, 2023). Thus, the 1st edition is considered here to be the first one in the series form, which is the 1998 edition. The 2023 edition of IEA’s WEO is the 26th edition (released in October 2023). It is the latest edition at the time of preparing the current study (IEA, 2023e).

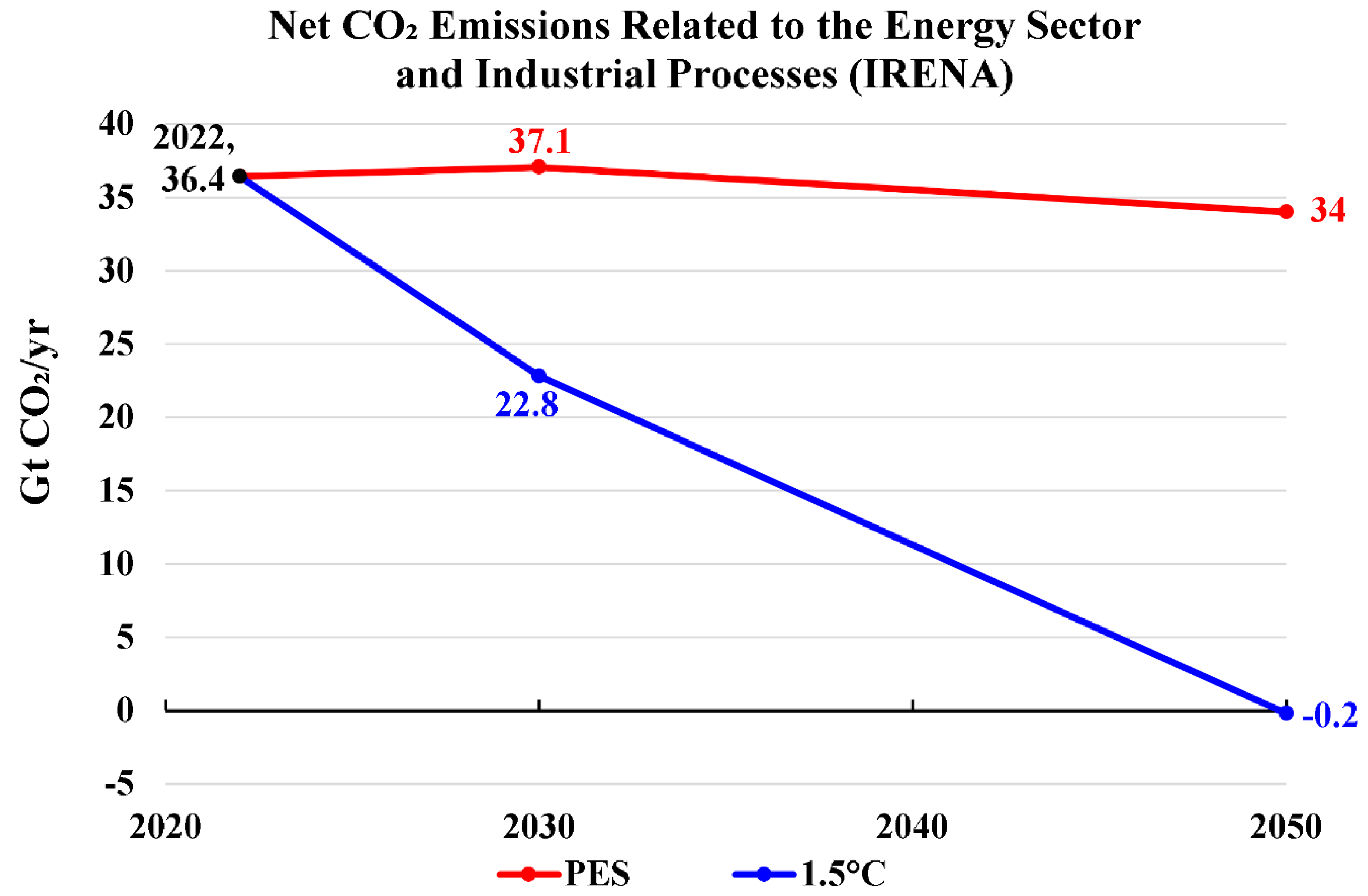

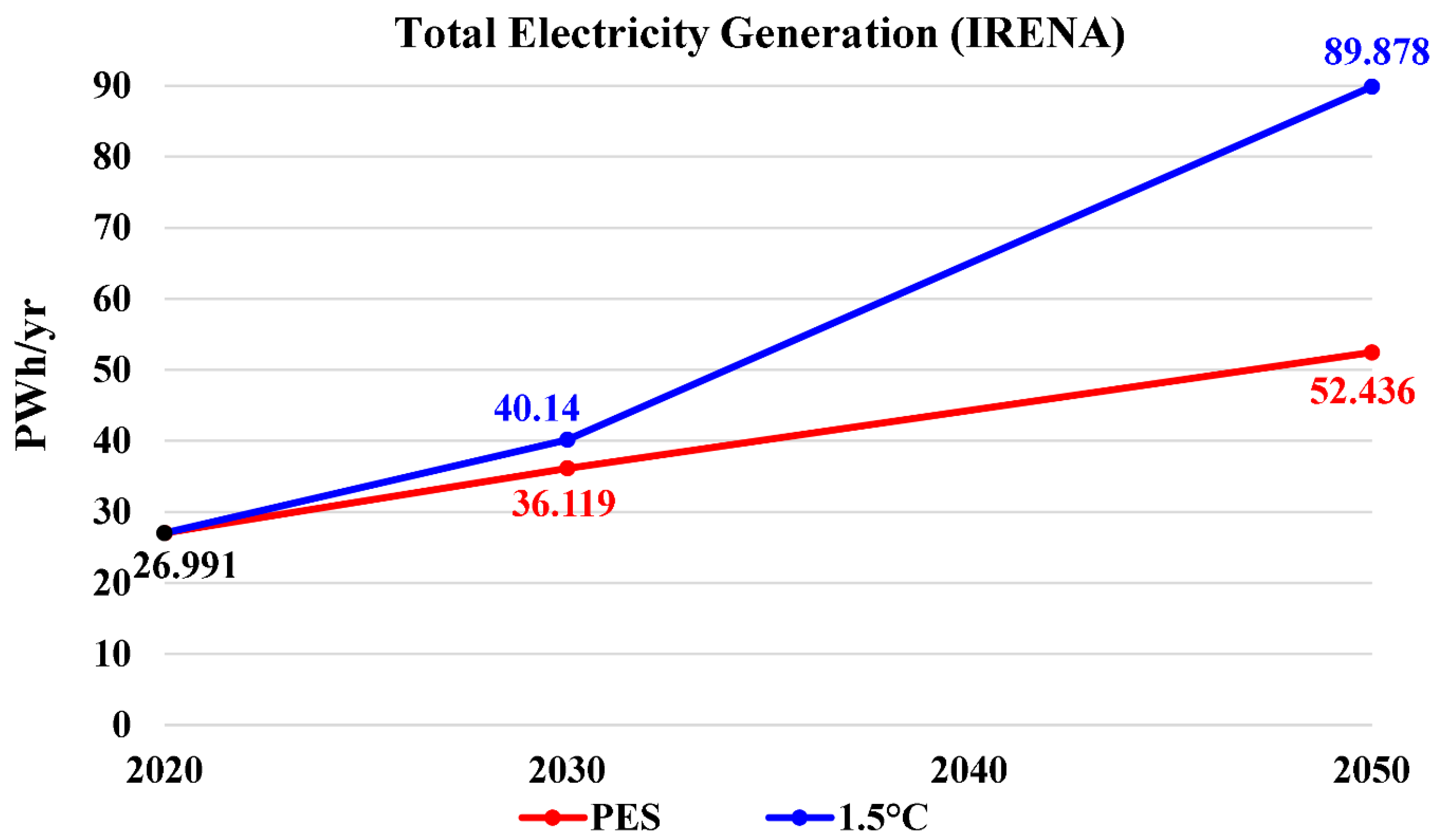

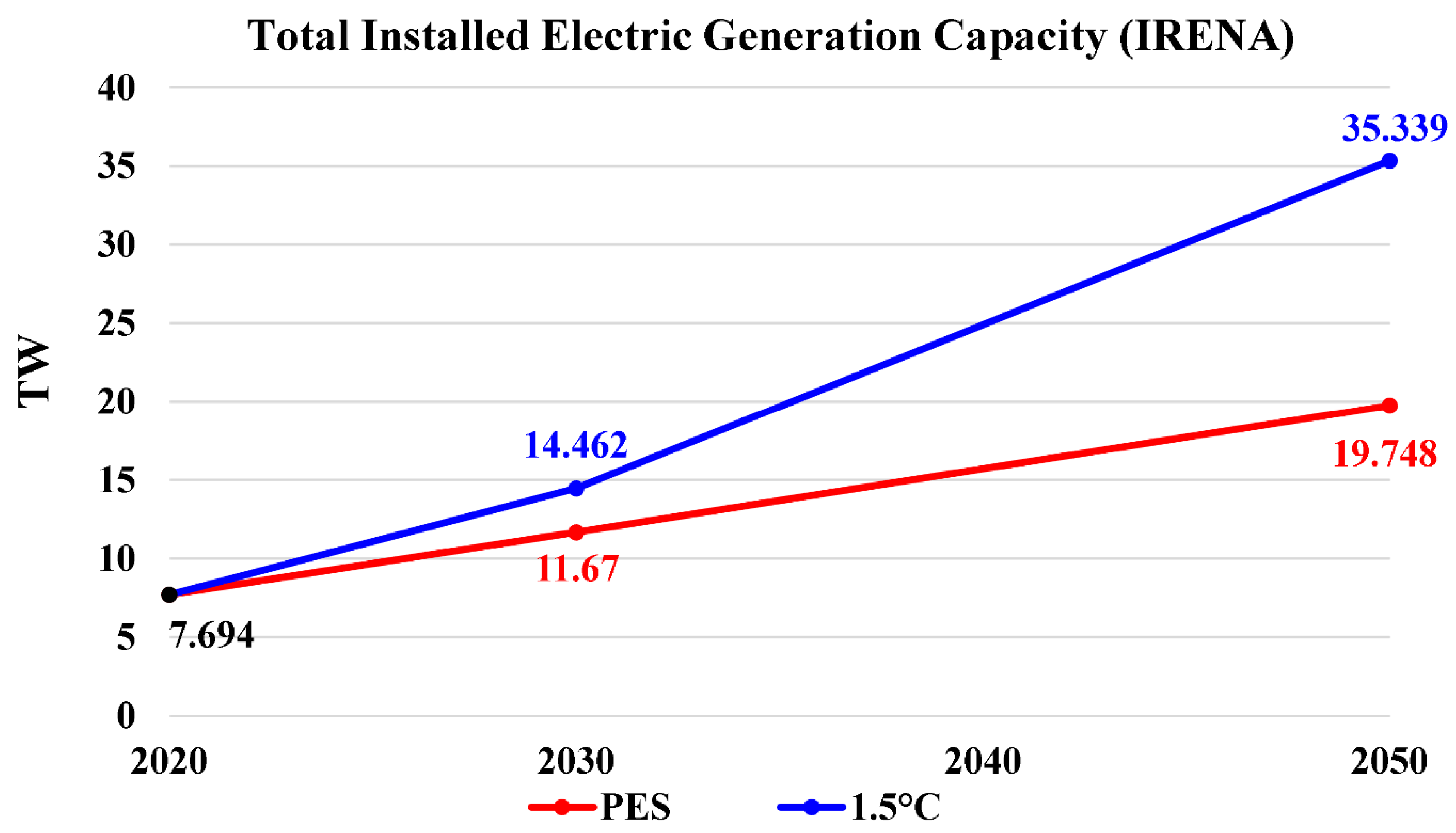

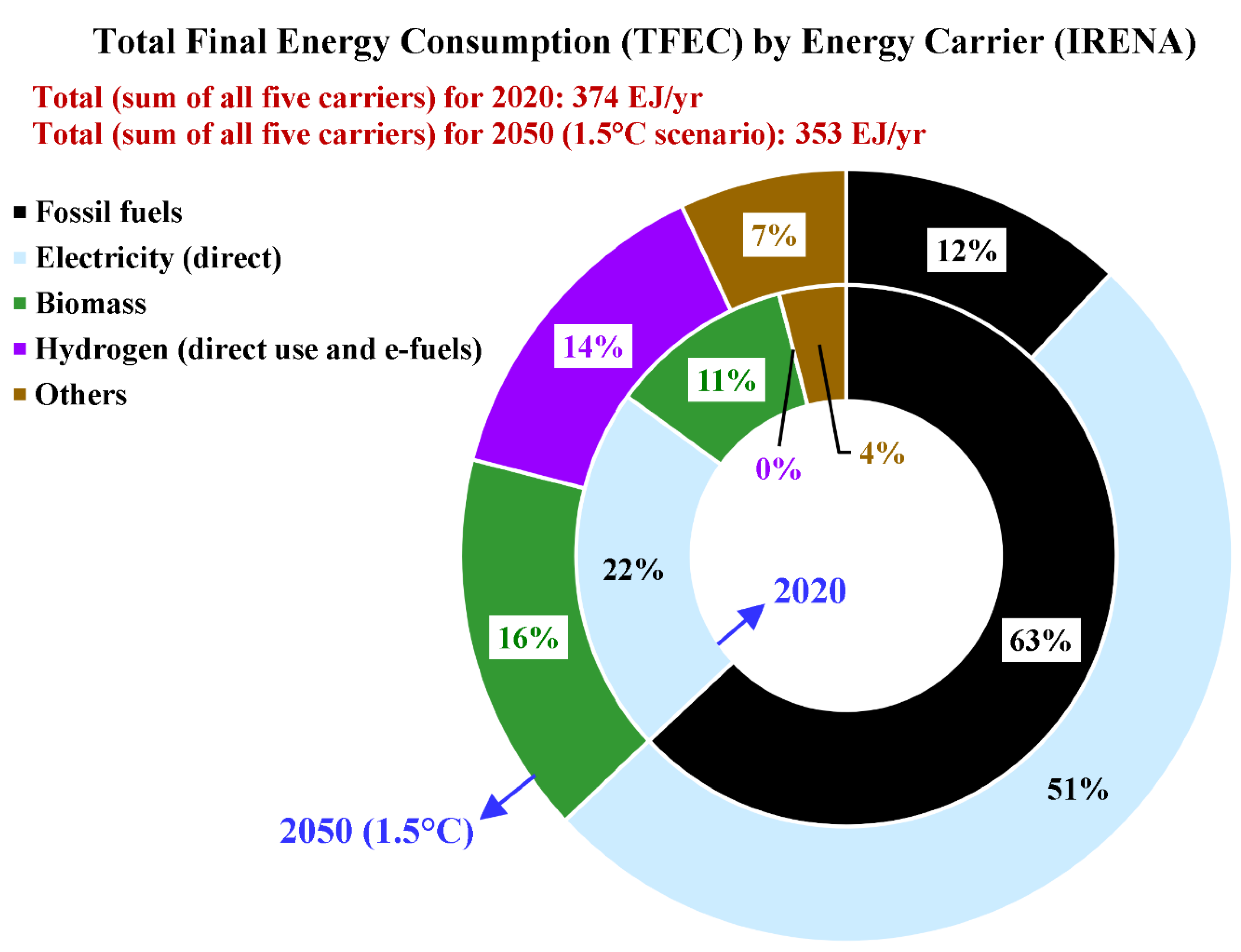

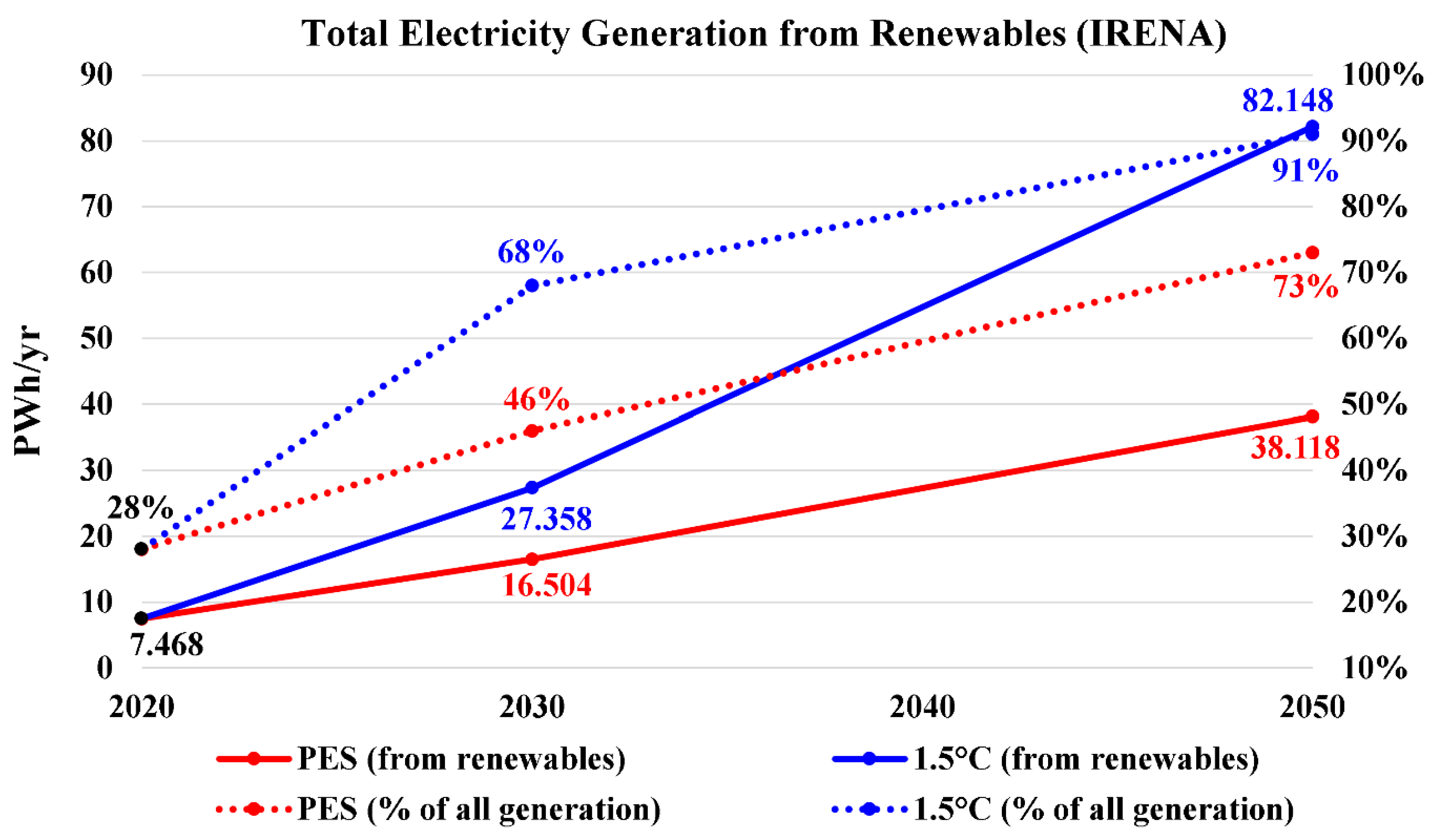

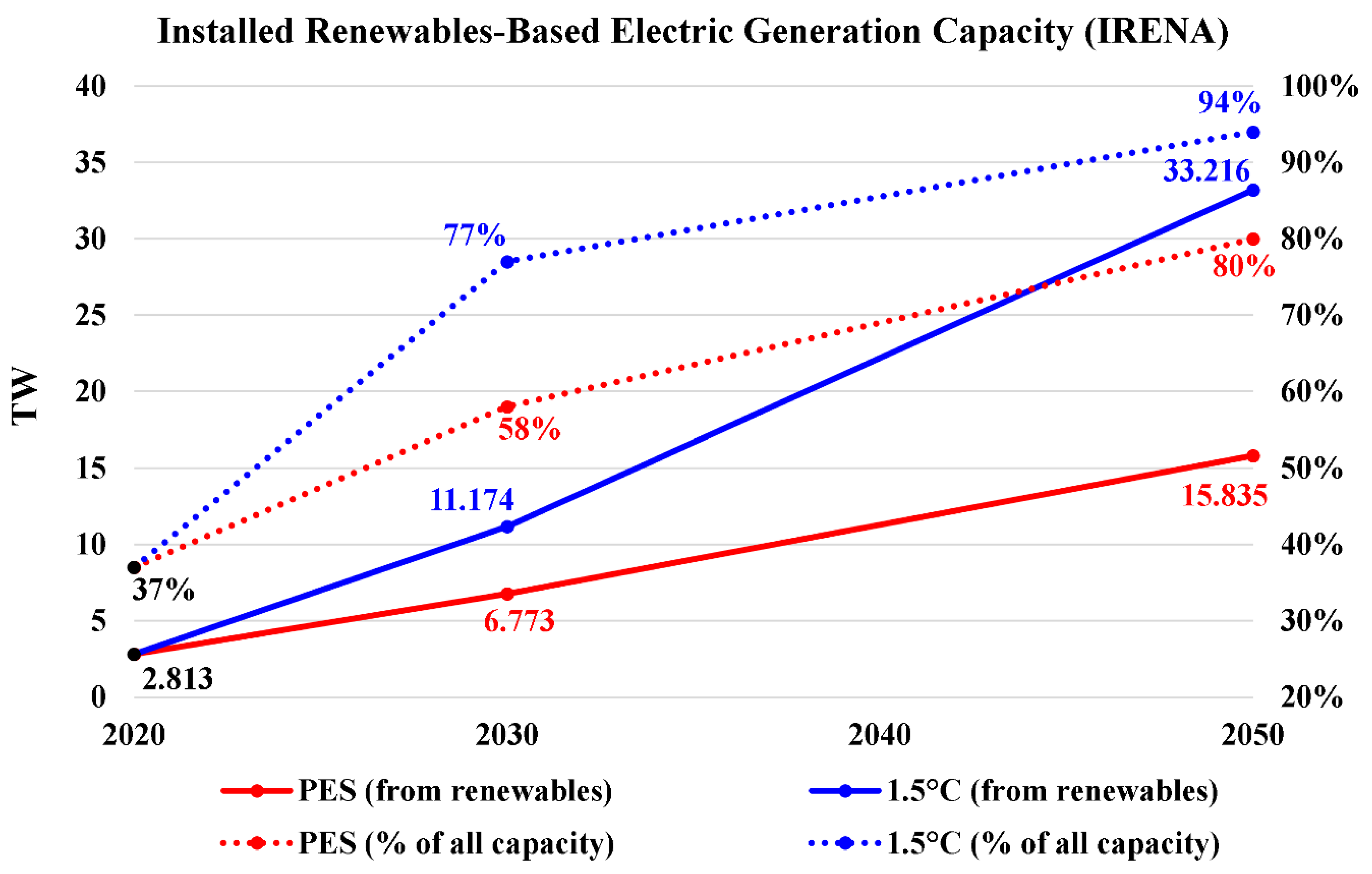

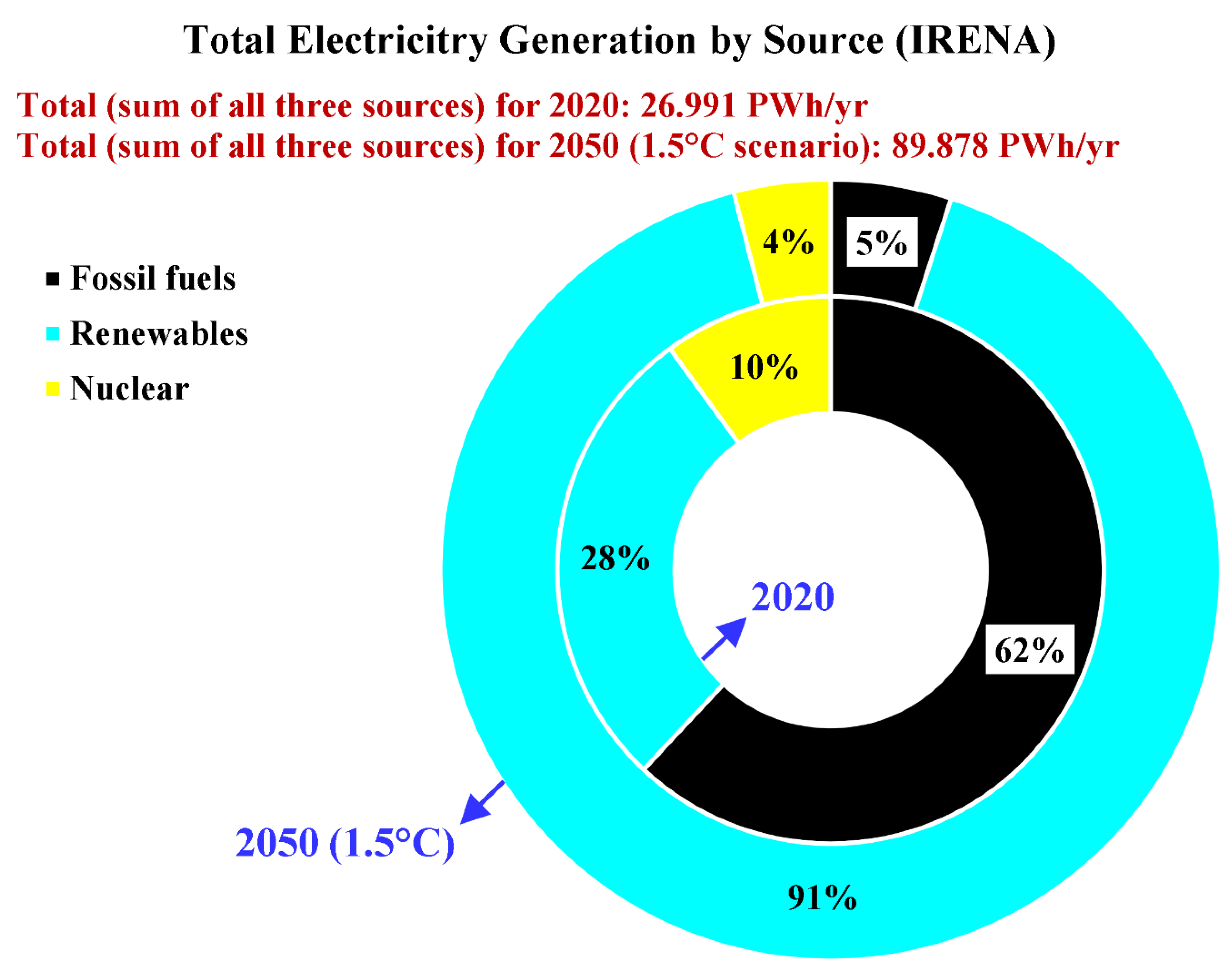

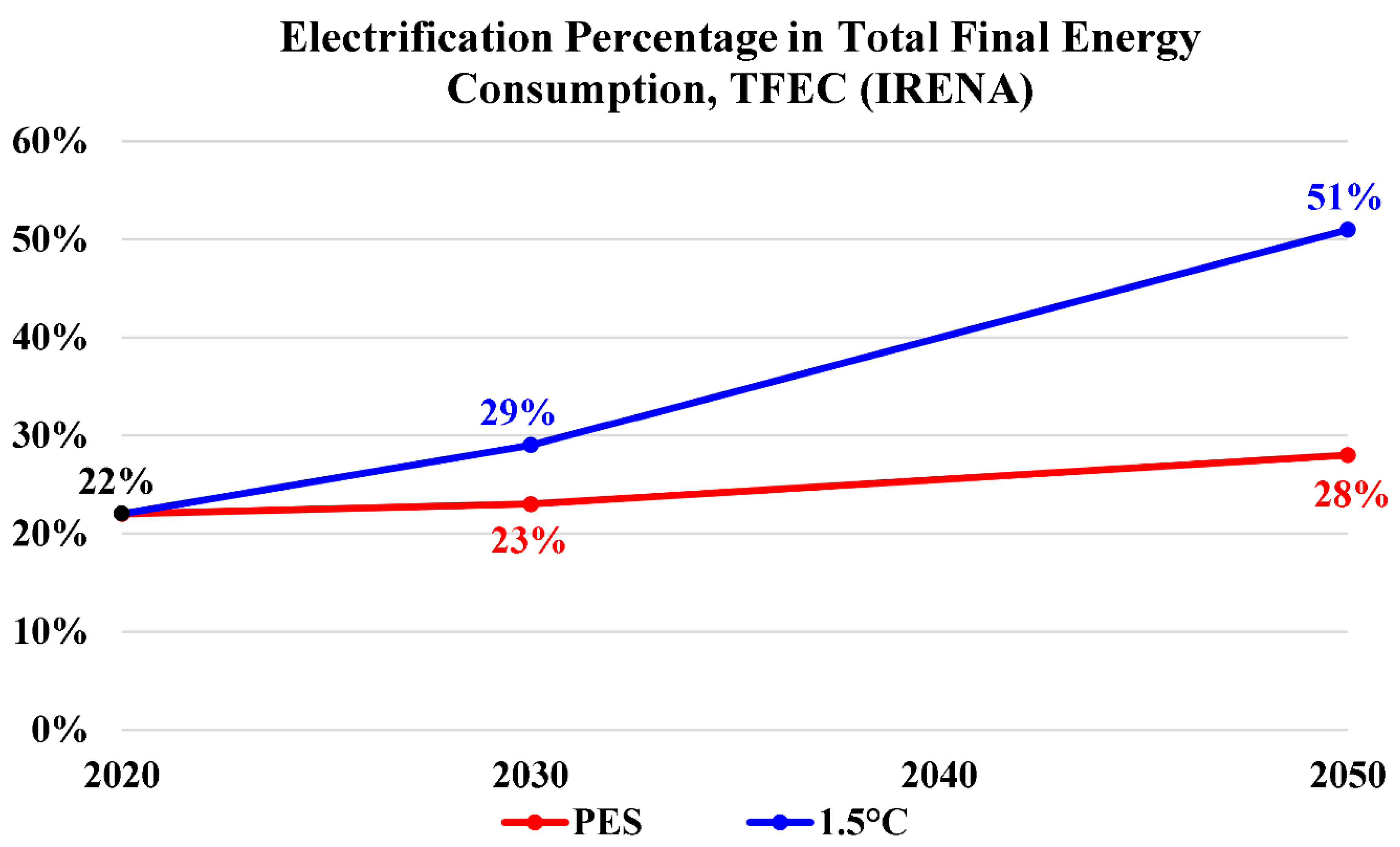

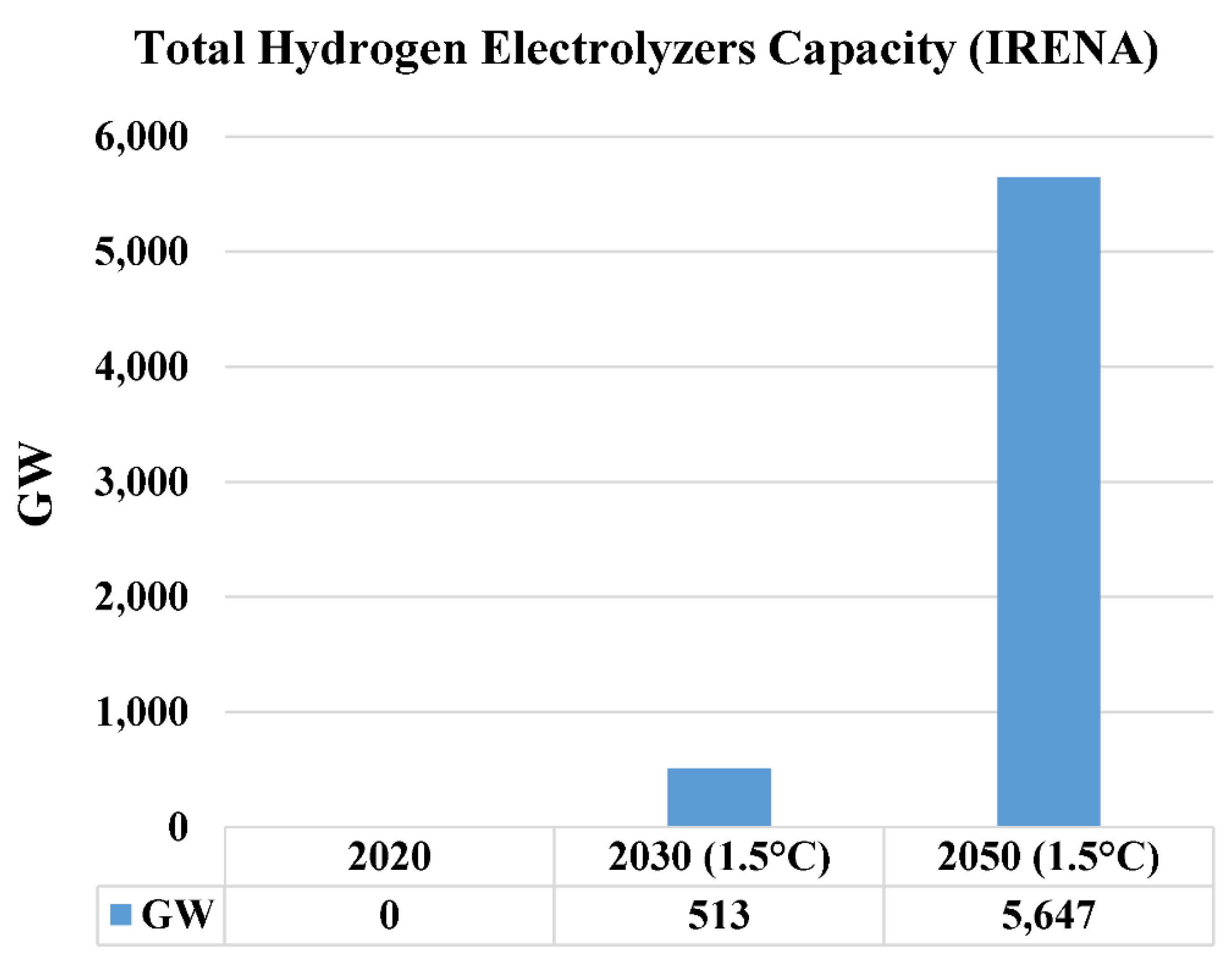

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) started an annual report series in 2021, which is titled World Energy Transitions Outlook (WETO). Thus, WETO-2021 was the 1st edition, while WETO-2023 is the 3rd edition. It is the latest edition at the time of preparing the current study (IRENA, 2023). In its 3rd edition, the WETO publication has been divided into two volumes, with volume 1 focusing on the progress across all energy sectors, and suggests (based on available technologies) a set of actions that need to be implemented by 2030 in order to limit the global average temperature rise to 1.5 °C by 2100 relative to pre-industrial levels, through achieving net zero emissions by 2050. Volume 2 of WETO-2023 is based on econometric modeling by IRENA, and it focuses on socio-economic impacts of the proposed 1.5°C pathway by IRENA, compared to current policy settings, which is referred to as Planned Energy Scenario (PES) by IRENA. Thus, volume 1 of WETO-2023 aims at addressing the technological and regulatory aspects of the energy transition, while volume 2 of WETO-2023 gives attention to the socio-economic implications of such energy transition (like its effect on employment and on welfare). In the present study, only volume 1 is covered, because volume 2 is outside the scope of the present study. It might be useful to add that WETO-2021, WETO-2022, and WETO-2023 (volume 1 only) were made available in an interactive online version in addition to the offline version (in the form of a PDF document). WETO-2021 was released in June 2021, WETO-2022 was released in March 2022, volume 1 of WETO-2023 was released in June 2023, and volume 2 of WETO-2023 was released in November 2023.

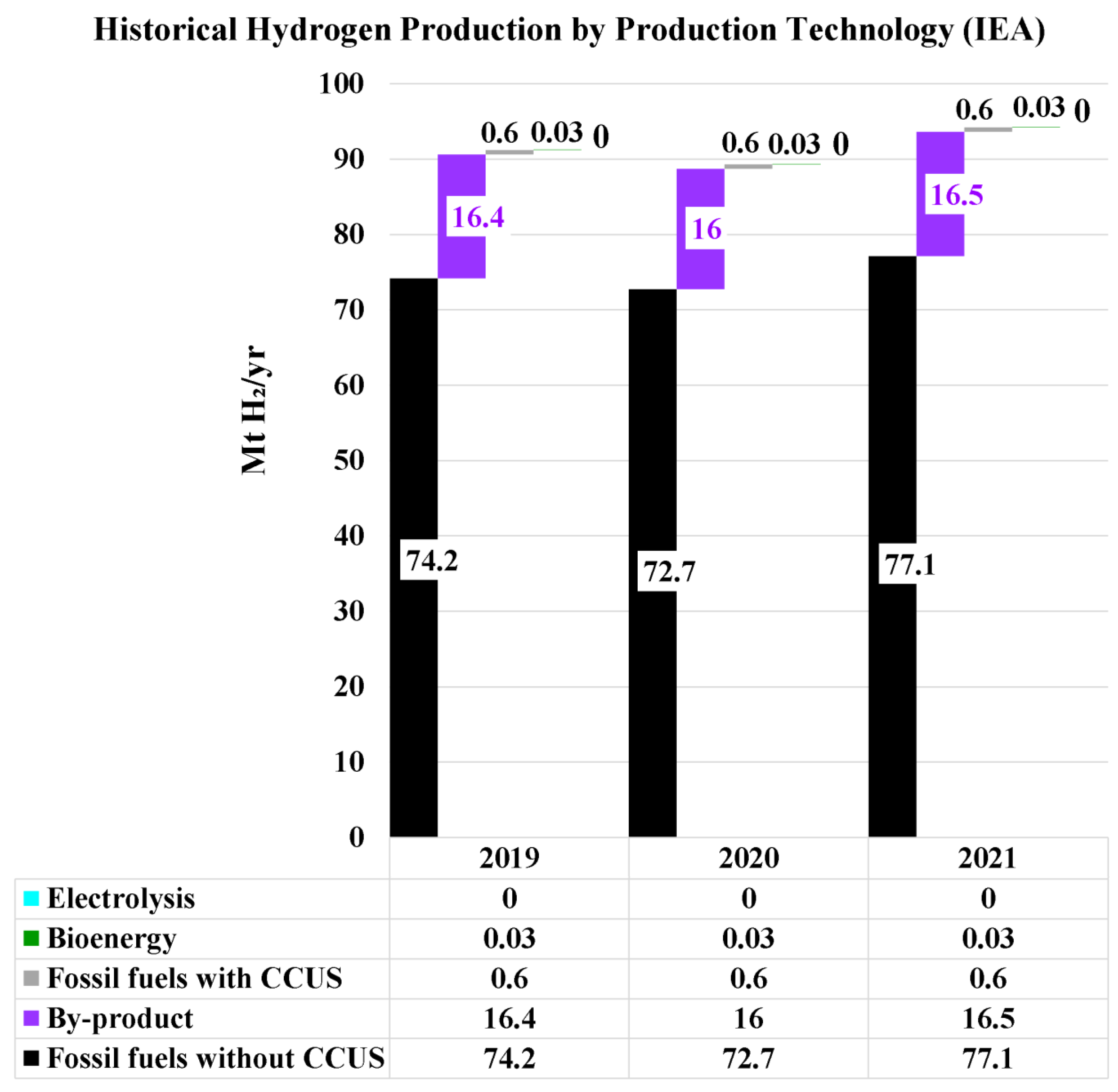

While hydrogen and its derived synthetic fuels (or e-fuels, electrofuels) do not currently represent a significant part of the energy market, efforts have been made toward more exploitation of these emerging energy carriers, particularly for environmental reasons, and thus to establish a large-scale hydrogen economy with alternatives to conventional fossil fuels (Tseng et al., 2005; Bockris, 2013; Oliveira et al., 2021; Squadrito et al., 2023; Marzouk, 2023a; Fajín and Cordeiro, 2024; Garlet et al., 2024).

Hydrogen can be produced in a clean way that releases no or little emissions. Electrolysis-based green hydrogen requires electricity to power water electrolyzers that split water into molecular hydrogen and molecular oxygen. The electricity should be from a renewable energy source, such as solar energy or wind energy, in order for the produced hydrogen to be described as green (Kakoulaki et al., 2021; Marzouk, 2022a; Schrotenboer et al., 2022). Furthermore, derived products from green hydrogen can be also described as green (or electricity-based), such as green ammonia (or e-ammonia), green methanol (or e-methanol), and green kerosene (or e-kerosene), which may also be called e-SAF: electricity-based sustainable aviation fuel (Salmon and Bañares-Alcántara, 2021; Schmidt et al., 2023). Blue hydrogen is produced from a fossil fuel, but with reduced CO2 emissions through a carbon capture technology. Environmentally, electrolysis-based green hydrogen is a preferable option than blue hydrogen, where a complete elimination of indirect CO2 emissions is not possible, because the extraction of the feedstock fossil fuels itself is a source of CO2 emissions (Longden et al., 2022). On the other hand, green hydrogen is more expensive than blue hydrogen, although this may be reversed if green hydrogen electrolyzers and renewable energy costs sufficiently drop in the future (Newborough and Cooley, 2021; Yu et al., 2021).

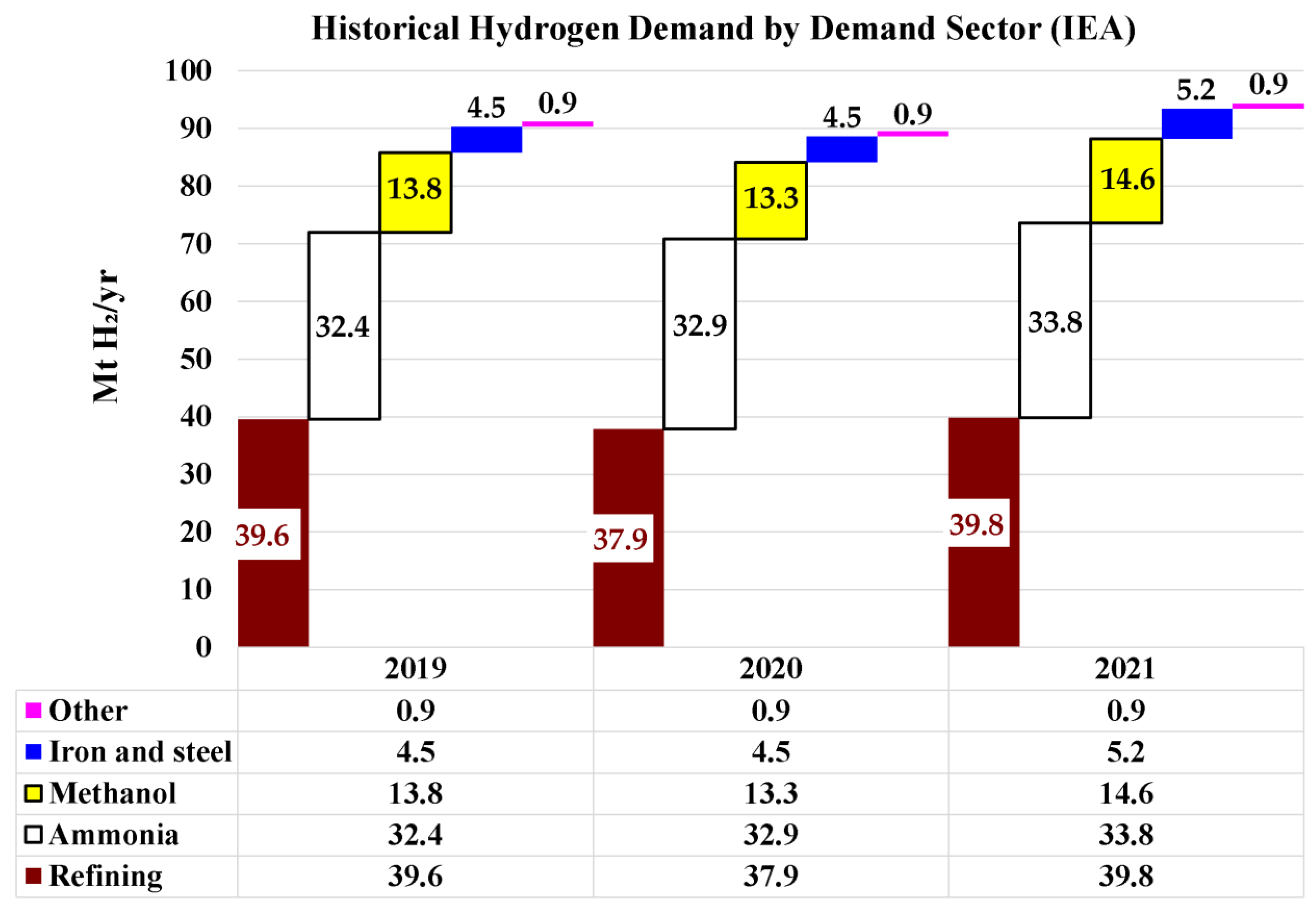

Applications of hydrogen and its derived products include electricity generation via fuel cells (Crespi et al., 2021), electricity generation via gas turbines (Pilavachi et al., 2009), fuel cell electric vehicles – FCEVs (Marzouk, 2023b), fuel cell electric unmanned aerial vehicles – UAVs (Çalışır et al., 2023), iron industry through direct reduction iron – DRI (Cavaliere et al., 2024), oil refining (Moradpoor et al., 2023), ammonia (NH3) production via the power-to-liquid (PtL) concept (Bahnamiri et al., 2022; Pagani et al., 2024), alternative synthetic non-fossil fuels derived from electrolysis-based green hydrogen (via PtL, PtG, PtX) like e-methane or e-kerosene (Ueckerdt et al., 2021; Yilmaz et al., 2022; Atsonios et al., 2023; Nemmour et al., 2023), and electricity storage by combining electrolyzers for hydrogen production and fuel cells for subsequent electricity production at the time of demand (Boretti, 2024).

The combustion of hydrogen (or its dissociation followed by oxidation in PEM fuel cells) does not release any carbon dioxide, which is an environmental advantage over any carbonaceous fuel (Zhou et al., 2006; Marzouk, 2023c). The replacement of fossil fuels with hydrogen (like replacing natural gas with gaseous hydrogen for heating homes and for cooking, or replacing gasoline/petrol with hydrogen for cars) helps in mitigating direct CO2 emissions, which in turn helps in stopping global warming and supports sustainability (Fernández et al., 2018; Field and Derwent, 2021; Marzouk, 2023d). Such decarbonization (even partial) of the energy or buildings sector improves the outdoor environment quality, and consequently the indoor environment quality (Lee and Chang, 2000; Cheng et al., 2019; Mundackal and Ngole-Jeme, 2022; Marzouk, 2022b).

Despite the apparently attractive shift toward hydrogen and its derivatives (in the electricity sector, the transport sector, the industry sector, and the buildings sector), expansion in the utilization of hydrogen and its derivatives is hampered by some barriers that need to be addressed before the investment in hydrogen and its products can be accelerated globally (Rand and Dell, 2007; Ball and Wietschel, 2009; Mazloomi and Gomes, 2012; Yue et al., 2021; Ishaq et al., 2022).

One of the barriers for large-scale hydrogen economy is the relative high cost per unit energy of hydrogen compared to other conventional energy sources. Based on the lower heating value (LHV), 1 kg of hydrogen has 120 MJ or 33.3 kWh (Chiesa et al., 2005). On the other hand, gasoline (petrol) has a volumetric LHV of 32.4 MJ/L or 9.00 kWh/L (Dupuis et al., 2019) and a gravimetric LHV of 43.0 MJ/kg or 11.9 kWh/kg (Amaral et al., 2021). Thus, for energy equivalence, 1 kg of hydrogen (1 kg H2) can replace 2.79 kg of gasoline or 3.70 L or approximately 1 U.S. gallon (Bothast and Schlicher, 2005). Based on recent data, the price of 1 U.S. gallon of regular gasoline in the USA is nearly US$ 3.1 (EIA, 2024). Thus, 1 kg H2 should be sold at this rate in order to be both economically and thermally equivalent to gasoline. In the Sultanate of Oman, the recent price of gasoline is nearly 0.23 OMR/L (NSS, 2024). Thus, 1 kg H2 should be sold at a price of OMR 0.85 (less than 1 Omani rial) in order to be both economically and thermally equivalent to gasoline. The levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) largely depends on the country, the hydrogen production technology, and the hydrogen production capacity (Khouya, 2020; Minutillo et al., 2021). However, recent studies suggest that for electrolysis-based green hydrogen, LCOH can be in the range of 1.35-7.7 USD globally (Abdin, 2022; BloombergNEF, 2020), 16.4-51.8 RMB (or 2.3-7.3 USD assuming a rate of 7.10 RMB/USD) in China (Fan et al., 2022; XE, 2024a), 2.17 OMR (or 5.63 USD assuming a rate of 2.60 USD/OMR) in Oman (Marzouk, 2023e), and €1.0 (or 1.1 USD assuming a rate of 1.1 USD/EUR) in Atacama Desert, Chile or €2.7 (or 3.0 USD assuming a rate of 1.1 USD/EUR) in Helsinki, Finland (Vartiainen et al., 2022; XE, 2024b). It is expected that the production cost of hydrogen falls down in the future, due to the increase in the electrolyzers manufacturing scale, the maturity of electrolyzers supply chains, and the decline in the cost of renewable electricity for powering electrolyzers (Hydrogen Council, 2020; Janssen et al., 2022; Hydrogen Council, 2023). However, the listed costs do not suggest that hydrogen is globally competitive compared to conventional alternatives, but also the gap is not dramatic. Green hydrogen is more expensive than blue hydrogen (about twice or trice the cost), which is partly due to the cost of the renewable electricity required for powering the electrolyzers, and partly due to the cost of electrolysis system that consists of the electrolyzers and their auxiliary components, such as cooling units (IRENA, 2020).

A second barrier for the hydrogen economy is the water consumption needed for hydrogen production regardless of the technology; such as for supplying electrolysis water, for supplying steam in the steam reforming process, for supplying liquid coolant water, or for the auxiliary carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) process. For example, PEM-based electrolysis may consume 17.5 L of water, and require about 8.2 L of additional recirculating water for producing 1 kg H2. Alkaline-based electrolysis may consume 22.3 L of water, and require about 9.9 L of additional recirculating water for producing 1 kg H2. Natural gas steam-methane reforming (SMR) combined with CCUS may consume 32.2 L of water, and require about 4.5 L of additional recirculating water for producing 1 kg H2. Without CCUS, the water requirements for SMR of natural gas may drop from 32.2 L to 17.5 L (consumption) and from about 4.5 L to about 2.5 L (reuse). Coal gasification with CCUS may consume 49.4 L of water, and require about 30.8 L of additional recirculating water for producing 1 kg H2. Without CCUS, the water requirements for coal gasification drop from 49.4 L to 31.0 L (consumption) and from about 30.8 L to about 18.8 L (reuse) (IRENA and Bluerisk, 2023). This matter can be specifically important for countries with limited access to renewable potable water. Despite this apparent concern, a recent study (Beswick et al., 2021) showed that if only electrolysis-based green hydrogen is produced (no blue hydrogen, thus no CCS/CCUS), then globally there should be no water problem even if the global production of hydrogen reaches 2,300 Mt H2/yr, with negligible amount of water consumed relative to the amount of water available. It should be noted that this mentioned study assumed that 1 kg H2 requires only 9 kg of water (consumption). This is just the theoretical demand based on stoichiometric (perfect) splitting of water, with zero water loss and with zero additional water needs for auxiliary processes. Therefore, this mentioned study assumed that the global water demand for hydrogen production does not exceed about 20,500 Mt of freshwater (or 20.5 billion m3 of freshwater) per year.

A third barrier that hinders the rapid growth of the hydrogen economy is the lack of adequate governmental regulatory framework for low-emissions hydrogen and its derivatives (as relatively new commodities). This barrier is related to licensing and coordination with local authorities for hydrogen production projects and related infrastructure, such as hydrogen pipelines and hydrogen storage facilities. This barrier is also concerned about establishing internationally recognized standards for the export/import of hydrogen and its derivatives, certification of hydrogen grade with clearly defining what low-emissions hydrogen (or clean hydrogen or sustainable hydrogen) is, and international trade of not only hydrogen and its derivatives but also electrolyzers and equipment for electricity generation using renewable energy (dena and WEC, 2022; IEA, 2023f; IRENA and WTO, 2023).

There are minor issues that affect hydrogen economy growth, such as the safety concerns regarding the handling of hydrogen (Galassi et al., 2012; Abohamzeh et al., 2021). Hydrogen is a flammable gas that has the most hazardous flammability level (level 4) in the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 704 diamond classification. This level indicates a substance that burns readily at atmospheric pressure and normal ambient temperature (NOAA, 2024). Another issue is building sufficient competence and specialized skills to ensure qualified personnel are available to work in the various stages of the hydrogen supply chain, from the production to the end-use (Beasy et al., 2023; Sandri et al., 2024). Increasing the public awareness and acceptance of the transition to hydrogen and its derivatives is a third issue, where people behavior should adapt to the alternatives provided by hydrogen and its derivatives. This include, for example, the use of a hydrogen refueling station (HRS) instead of a traditional gas station (petrol station), and the willingness to choose a fuel cell electric vehicle rather than a conventional gasoline vehicle (Ricci et al., 2008; Gordon et al., 2002).

Despite the mentioned barriers, there are also drivers that encourage the development of a hydrogen economy. Such hydrogen economy drivers include formal or voluntary aims to adopt environmentally-friendly solutions and emissions mitigation, and local (national) incentives or subsidies (Dolci et al., 2019; Bartlett and Krupnick, 2020). The H2Global Foundation (H2Global Stiftung in German) is an international incentivizing scheme for accelerating a global hydrogen market. Through the H2Global funding instruments, large green electrolysis-based green hydrogen production projects outside the European Union (EU) can apply for a 10-year fixed-price hydrogen purchase agreement (HPA) where they guarantee they can market their production of green hydrogen-derived product to the German government-backed off-taker company HINT.CO (Hydrogen Intermediary Network Company GmbH), which is a subsidiary of the German non-profit project H2Global Foundation. HINT.CO acts as an intermediary, by purchasing hydrogen-derived products (lot 1: green ammonia, lot 2: green methanol, lot 3: green kerosene or electricity-based sustainable aviation fuel – e-SAF) from a supplier outside EU through auction-based HPAs, and then selling that green hydrogen product in Germany or another EU country through auction-based hydrogen sales agreements (HSAs), whose duration is limited to a maximum of 1 year. The H2Global Foundation was established in June 2021. It was financially supported by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy in Germany (BMWi: Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie), which in December 2021 became the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK: Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz). The German ministry provides the necessary financial aid to cover any gap between the selling price of the green hydrogen product (in EU) and the production cost of it (outside EU). The initial governmental funding grant in 2021 was €900 million (BMWK, 2022a; BMWK, 2022b). In the first HPA tender (started 30 November 2022), only green ammonia (lot 1) was demanded, and the 10 contract years were 2024-2033 (TED, 2022).