1. Introduction

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) remains a significant public health concern, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Pregnant women are at increased risk of IDA due to specific pathophysiological mechanisms [

1]. Those affected by IDA during pregnancy are more susceptible to complications such as perinatal infections, preeclampsia, cardiac failure and hemorrhagic events, which in severe cases may lead to maternal mortality [

2,

3]. Moreover, IDA is associated with high rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality [

4,

5]. A recent meta-analysis reported that maternal anemia is linked to an 18% increase in perinatal mortality and a 20% rise in maternal mortality in South Asian countries, including India [

6].

Iron plays a crucial role in fetal development, facilitating rapid cellular proliferation and brain myelination [

7,

8]. Maternal iron deficiency is associated with adverse neonatal outcomes, including preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction, as well as increased risks of cognitive delays [

9], autism, learning disabilities, neurodevelopmental disorders [

10], and metabolic syndrome in adulthood [

2]. Newborns with low iron stores require immediate evaluation and intervention, as untreated iron deficiency can have long-term consequences, diminished cognitive function, and impaired immune system development [

11,

12]. However, the impact of maternal IDA on fetal iron status remains controversial. Previous evidence suggests that the fetus absorbs iron from the mother regardless of her iron levels, [

7,

8] while others reported that maternal iron deficiency leads to lower fetal and neonatal iron stores [

13,

14]. As maternal iron serves as the primary source of iron for the fetus, assessing the prevalence of IDA and its consequences is crucial [

15]. Research indicates that term infants born to mothers with IDA often have inadequate iron stores, increasing their risk of anemia [

15,

16].

Additionally, evidence consistently highlights a strong correlation between maternal hemoglobin levels and adverse birth outcomes [

17]. A recent systematic review found that iron deficiency during the first and second trimesters significantly heightens the risk of unfavorable pregnancy outcomes and maternal morbidity [

18]. Several studies have investigated the impact of maternal hematological status, particularly hemoglobin and serum ferritin levels on the iron reserves of newborns and pregnancy outcomes; however, the findings have been inconsistent. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to correlate maternal iron indices in the second trimester with cord blood indices and pregnancy outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The present study was a prospective cohort study nested within the RAPIDIRON Trial [

19] at Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College-Women’s and Children’s Health Research unit, Karnataka, India. Pregnant women who had moderate anaemia and subsequently receiving oral iron supplementation were eligible for enrolment. This study (KAHER/EC/21-22/001) was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of KLE Academy of Higher Education and Research (KAHER), Belagavi.

2.2. Participants

We included consenting pregnant women between ages 18-40 years from the rural CHC and PHC in and around Belgaum in the early second trimester. Hb concentration of 7.0-9.9g/dL defined moderate anemia and represented an inclusion criterion. Maternal participants with a twin pregnancy or any congenital anomaly diagnosed at dating ultrasound were excluded.

2.3. Sample Size

The sample size was estimated assuming a prevalence of 37.3% of anemia in pregnant women [

20], with confidence interval of 95% corresponding to 1.96 alpha, and 15% margin of error resulting in a calculated sample size of 287.

2.4. Study Procedure

All pregnant women were screened initially in the first trimester and blood samples were collected in the early second trimester at 12-16 weeks of gestation. Pregnant women with hemoglobin levels ranging from 7.0 to 9.9 g/dL, serum ferritin < 30 ng/mL and/or TSAT < 20% were eligible for this study. As a part of RAPIDIRON Trial, participants were recommended to take 60 mg ferrous sulphate twice a day and 400 mcg folic acid once a day throughout pregnancy. A pregnant participant who consented for the study were contacted in the mid (20-24 weeks) and late (26-30 weeks) second trimester and maternal blood sample as well as cord blood sample was collected following delivery. Also, a detailed history of maternal and neonatal outcome was noted. The term “Pregnancy outcomes” encompass instances where current pregnancies result in low birth weight, preterm birth or stillbirth. All the anthropometric measurements data including, birth weight, birth length was retrieved from data in the RAPIDIRON Trial [

19].

2.5. Laboratory Investigation

A 2 mL sample of both maternal and cord blood was collected in EDTA and plain vacutainers for whole blood and serum analysis in respective visits. Serum aliquots were separated and stored at -80ºC for sTfR assay until analysis. sTfR concentrations were measured by Sandwich ELISA method. Serum analysis included Ferritin, transferrin saturation (TSAT) were immediately analysed by Roche-Cobas-6000 [ECLIA]. Whole blood analysis included hemoglobin, reticulocyte- hemoglobin (Ret-Hb), immature reticulocyte fraction (IRF), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) were analysed in Sysmex-Hematology analyser.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All the categorical variables were summarized using frequency and percentages. All the continuous variables were summarized using Mean (SD)/Median (Q1, Q3) depending upon the normality of the data. The normality assumption was assessed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Karl Pearson’s/Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to find the association between maternal iron indices and cord blood iron indices. Mixed ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) was used to compare the trend in maternal Hb, TSAT, Ferritin, and sTfR over time across different group. Mauchly’s test was employed to assess the sphericity of the data and Greenhouse-Geisser corrected significance values were used when sphericity was lacking. Post hoc analysis was performed with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. All the statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 16. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance for all analyses. Outcomes were categorized as following: Neonatal anemia as anemic (Hb <13.0 g/dL) and non-anemic (Hb ≥ 13.0 g/dL), Birth weight as low birth weight (<2.5 Kgs) and normal birth weight (≥2.5 Kgs), Gestational age at time of birth as preterm birth (<37 weeks) and term birth (≥37weeks).

3. Results

Of 315 participants enrolled, a cohort of 292 mothers was included in the final analysis of the study as 23 cord blood samples could not be collected and were lost to follow-up. A subsample of 105 subjects were analysed to determine Soluble Transferrin Receptor (sTfR) at each time point. Key maternal and newborn characteristics, complications and cord blood variables are outlined in

Table 1.

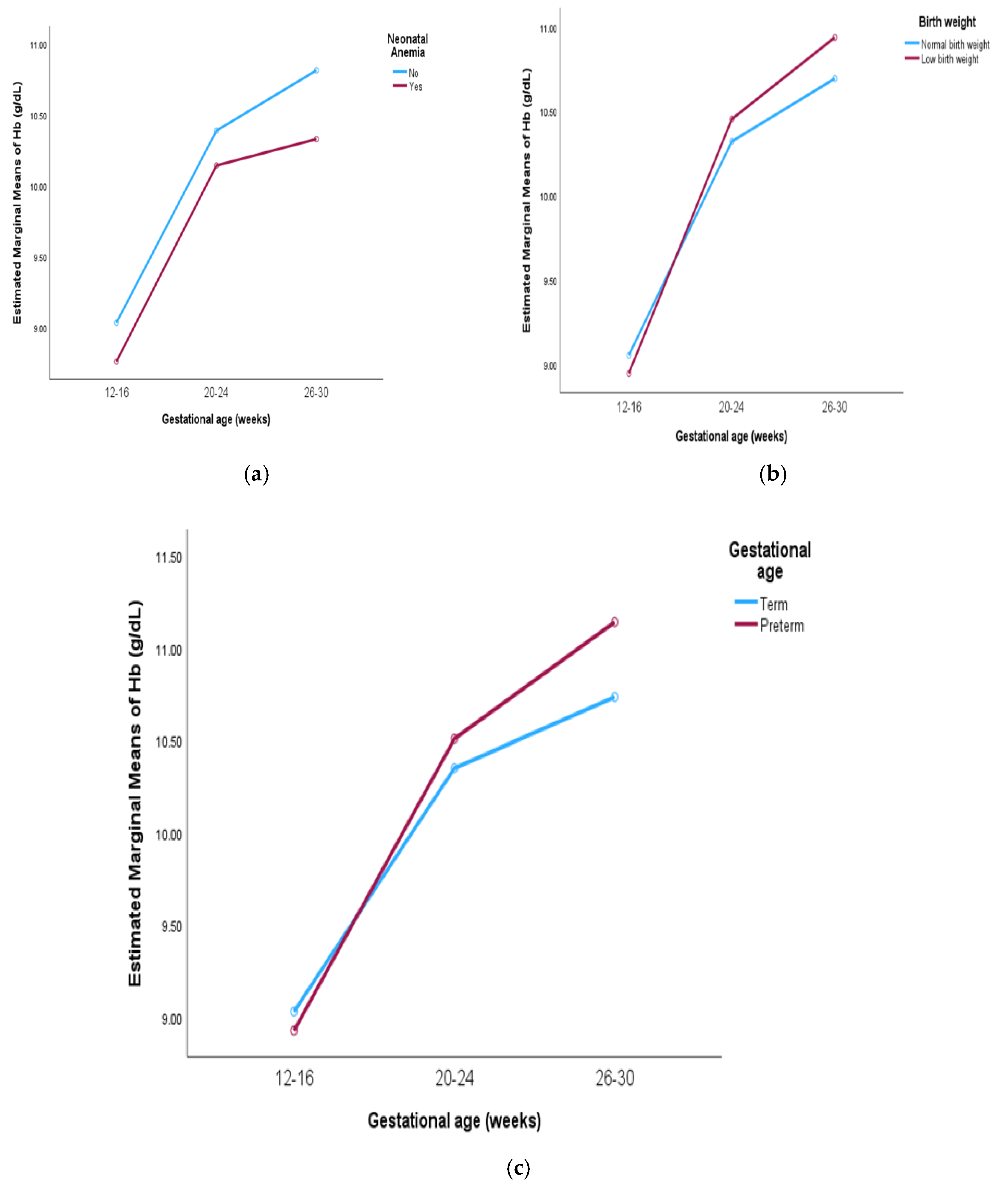

The comparison of trends in maternal hemoglobin levels across gestational age and pregnancy outcomes is represented in

Table 2. A significant increase in maternal hemoglobin levels was observed in mothers of both anemic and non-anemic neonates. In mothers of anemic neonates, hemoglobin levels increased from 8.76 to 10.32 g/dL, while in mothers of non-anemic neonates, levels rose from 9.03 to 10.81 g/dL (p < 0.001). Despite the overall increase, the rise in hemoglobin levels was gradual in mothers of anemic neonates, with no significant difference between group (

Figure 1a). Additionally, mothers of low birth weight neonates exhibited a significant increase in hemoglobin levels from 8.94 to 10.93 g/dL, compared to an increase from 9.05 to 10.69 g/dL in mothers of normal weight neonates (p < 0.001). Interaction F value of 3.28 (p = 0.05) is also observed (

Figure 1b). A significant increase in hemoglobin levels was also observed in mothers of both preterm and term neonates (p < 0.001), with a trend toward higher levels in mothers of preterm neonates (

Figure 1c).

Post hoc comparisons adjusted using Bonferroni corrections were performed on maternal iron indices (hemoglobin, TSAT, ferritin, sTfR) across gestational periods (12-16, 20-24, 26-30) weeks over pregnancy outcome group. A significant difference in hemoglobin levels was observed across pregnancy outcome group (p<0.001). However, for mothers of anemic neonates, there was no significant difference in hemoglobin levels between the 20-24 and 26-30 weeks (p=0.69).

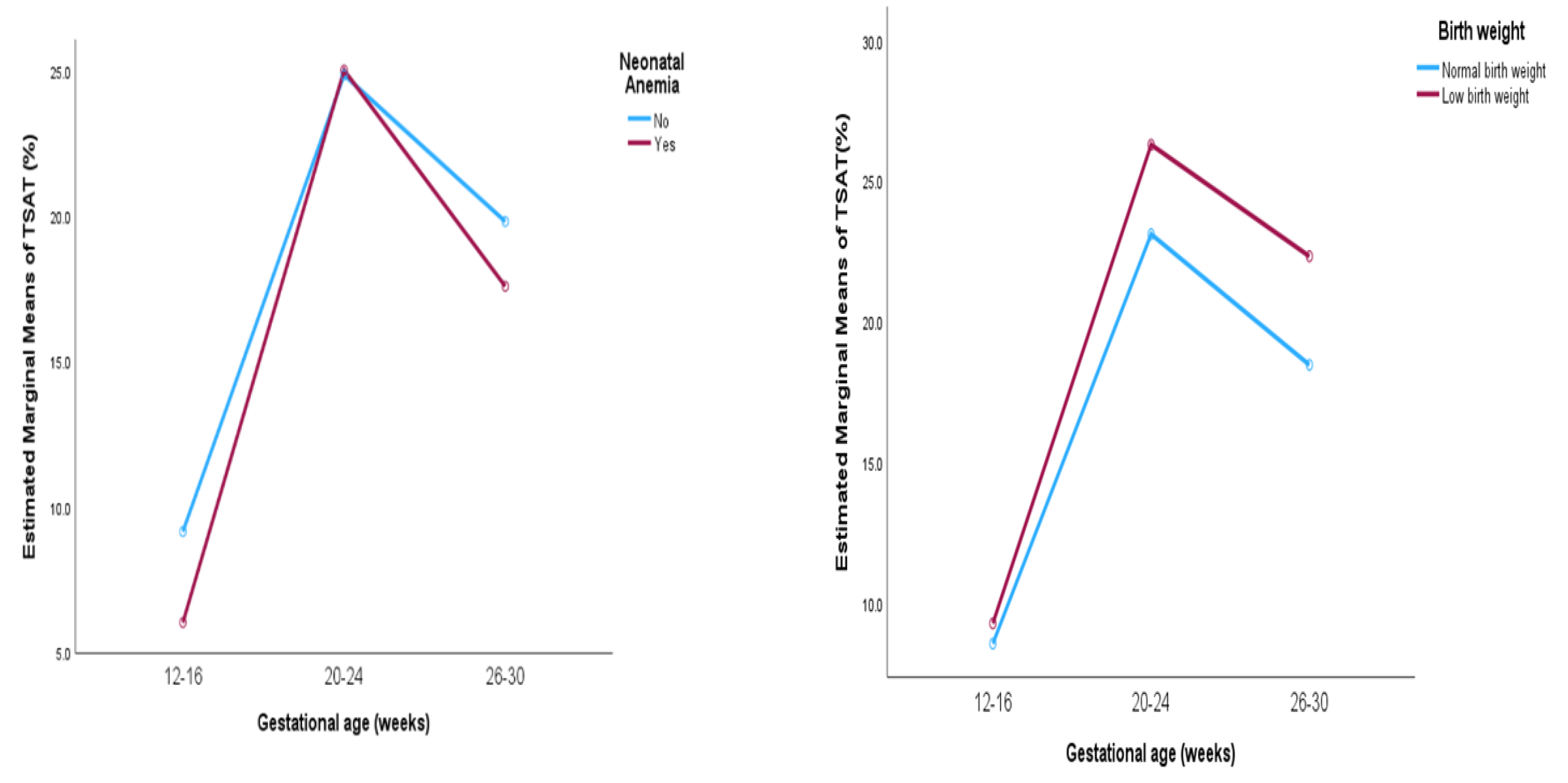

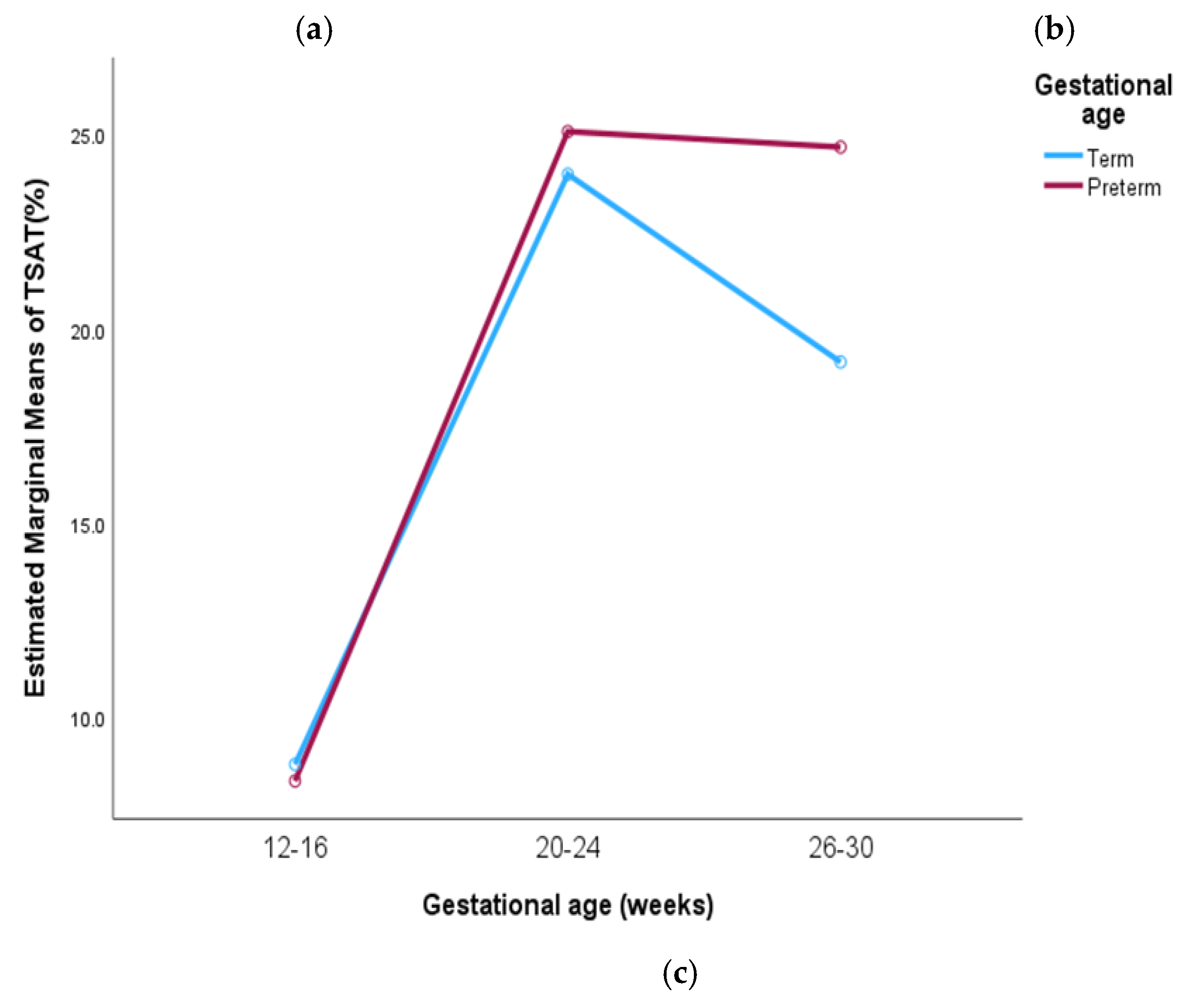

The comparison of trends in maternal transferrin saturation (TSAT) levels across gestational age and pregnancy outcomes is represented in

Table 3. A significant increase in maternal TSAT levels was observed from baseline to the mid-second trimester, followed by a slight decline in the late second trimester across all group with all changes being statistically significant (p < 0.001). In mothers of anemic neonates, TSAT levels rose significantly from 6.02% to 17.57%, while in mothers of non-anemic neonates, levels increased from 9.14% to 19.79% (

Figure 2a). For mothers delivering a low birth weight neonate, TSAT levels rose from 9.24% to 22.30%, higher compared to an increase from 8.52% to 18.44% in mothers delivering normal weight neonates (

Figure 2b). Similarly, TSAT levels were higher in mothers with preterm deliveries where it increased from 8.36% to 24.67% compared to 8.78% to 19.14% in those with term deliveries (

Figure 2c). No significant differences were observed between the group in pregnancy outcomes.

Post hoc analysis for TSAT levels among mothers of non-anemic, normal weight, term birth neonates showed a significant difference at each gestational week (p<0.001). TSAT level in mothers of anemic, low birth weight, preterm neonates showed no significant difference across 20-24 to 26-30 weeks of gestation (p=0.19, 0.16, 1.00).

The comparison of trends in maternal ferritin levels across gestational age and pregnancy outcomes is represented in

Table 4. A pattern similar to maternal TSAT was observed with ferritin levels significantly increasing from baseline to mid-second trimester, followed by a slight decline in the late second trimester across all groups. All changes in ferritin levels were statistically significant (p < 0.001). In mothers of non-anemic neonates, ferritin levels increased throughout the second trimester from 11.15 to 35.44 ng/mL, whereas mothers of anemic neonates exhibited comparatively lower ferritin levels, increasing from 8.86 to 30.51 ng/mL.

Mothers of low birth weight neonates showed an increase from 12.93 to 36.52 ng/mL, while in mothers of normal birth weight neonates, levels rose from 11.62 to 33.51 ng/mL. Notably, ferritin levels were higher in mothers of low birth weight neonates compared to those delivering normal birth weight neonates. Similarly, ferritin levels were higher in mothers of preterm neonates, increasing from 15.64 to 40.71 ng/mL, compared to 11.67 to 33.83 ng/mL in mothers of term neonates. No significant differences were observed between pregnancy outcome group (

Supplementary Figure S1).

Post hoc analysis for Ferritin levels revealed that there was a significant difference observed between mothers of all pregnancy outcome group across all weeks of the gestation (p<0.001). However, no significant difference was observed between 20-24 and 26-30 weeks (p=1.00).

Trends in maternal soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) levels across different gestational ages and pregnancy outcomes is depicted in

Table 5. The findings indicate a statistically significant improvement in sTfR levels across all groups (p < 0.001). In mothers with anemic neonates, levels declined from 7.72 to 5.87 µg/mL, while those with non-anemic neonates showed a reduction from 7.51 to 5.76 µg/mL. Similar trends were observed in mothers of low birth weight (7.41 to 5.79 µg/mL) and normal birth weight neonates (7.62 to 5.79 µg/mL). Additionally, sTfR levels decreased in mothers of preterm (7.74 to 6.04 µg/mL) and term neonates (7.54 to 5.78 µg/mL). The graphical representation of the trend in maternal sTfR levels across gestational ages and outcomes are provided. (

Supplementary Figure S2).

Post hoc analysis for sTfR levels showed significant differences among mothers in all pregnancy outcome group across all weeks of gestation (p<0.001). Maternal iron indices showed negligible correlation with cord blood iron indices. The results are provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

4. Discussion

This study observed a substantial increase in maternal hemoglobin, TSAT, ferritin and sTfR levels throughout pregnancy. Across all three visits, maternal hemoglobin levels were higher in non-anemic neonates than in anemic neonates, suggesting that elevated prenatal hemoglobin corresponds to higher neonatal hemoglobin concentrations. Notably, term and normal birth weight neonates exhibited lower maternal hemoglobin at the second and third visits, suggesting that adverse delivery outcomes may occur despite adequate maternal hemoglobin levels. Furthermore, maternal ferritin and TSAT followed similar trends, while a significant decrease in sTfR levels indicated improved iron status and normal erythropoietic activity.

A study reported that neonates born to anemic mothers had considerably lower Hb values (p < 0.05) than those born to non-anemic mothers [

21]. Our investigation found a similar relationship between lower maternal Hb values and lower Hb in neonates. In contrast, a study found no relationship between maternal and newborn Hb levels (Pearson correlation: -0.01) [

22]. Several studies found no link between maternal Hb levels, neonatal iron status, and risk of preterm birth. Despite low Hb levels in the first trimester and an increase in the second, maternal Hb was not associated with a higher risk of preterm delivery [

23,

24] suggesting that Hb levels may not directly influence adverse birth outcomes.

Preterm births may occur in mothers with normal Hb levels due to other factors such as thyroid dysfunction, placenta previa, or a history of preterm births [

25]. Similar findings were observed in our study, that preterm neonates had higher maternal Hb levels than term newborns. Elevated Hb in the second and third trimesters was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth and small for gestational age (SGA) infants, while high Hb levels in the first and second trimesters was associated with SGA but not preterm birth [

26]. This correlates with the elevated maternal Hb levels in our study’s preterm and LBW newborns. In contrast to our study Smith et al. reported that reduced risk of spontaneous preterm birth was associated with low Hb in the third trimester [

27].

A high Hb concentration in the early third trimester may indicate insufficient plasma volume expansion, increasing blood viscosity and impairing placental perfusion [

28,

29,

30]. This reduces fetal oxygen and nutrient delivery, compromising growth and development [

31,

32]. As a result, elevated hemoglobin levels during pregnancy are linked to a higher risk of adverse outcomes. Thus, proper plasma volume expansion is crucial for promoting positive pregnancy outcomes. An inverse relationship was found between the birth weight and higher maternal ferritin levels during the second trimester [

33]. Another study reported that there is a significant correlation between low birth weight and preterm birth when there was a high serum ferritin level in the third trimester [

34]. Similarly, a Chinese study identified a correlation between elevated ferritin levels in the second trimester and an increased incidence of preterm birth and low birth weight [

35,

36]. Similar findings were also observed in our study, which showed that preterm and low birth weight neonates had higher maternal ferritin concentrations than term and normal birth weight neonates.

Elevated ferritin levels in the second or third trimester have been linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes [

37,

38] possibly indicating inflammation or inadequate plasma volume expansion. Excess iron surpasses transferrin capacity, leading to non-transferrin bound iron, which induces oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and DNA damage in placental cells. This disrupts immune responses and fetal growth, contributing to adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes [

39,

40]. A comparative study investigating the iron status of pregnant and non-pregnant women found a significant increase in iron and TSAT levels from the first to the third trimester [

41]. Similarly, in our study, we observed a significant increase in maternal TSAT levels from early to mid-second trimester, followed by a slight decline in the late second trimester across all outcome groups.

Serum sTfR levels are raised when membrane transferrin receptors are activated to improve iron uptake into cells when tissue iron availability is low [

42]. A study on iron supplementation in women with iron deficiency without anemia found significant reductions in sTfR and rise in serum ferritin and hemoglobin levels [

43]. Similarly, another study reported improved sTfR and TIBC [

44]. In our study, sTfR levels significantly improved from early to late second trimester of pregnancy. We found only a negligible correlation between maternal and cord blood iron indices. Similarly, findings were also observed in another study [

21]. However, in contrast with our findings another study demonstrated a significant relationship between maternal and cord blood iron, ferritin, sTfR, and the sTfR/log ferritin index [

45,

46].

A key strength and limitation of this study is its exclusive focus on pregnant women with moderate anemia receiving oral iron supplementation., providing valuable insights into maternal and neonatal outcomes. Unlike most studies assessing iron parameters (Hb/Ferritin) at limited time points, we evaluated iron indices longitudinally across pregnancy, incorporating maternal and cord blood variables. The inclusion of sTfR enhances understanding of erythropoiesis and iron status. Our comprehensive analysis of maternal, neonatal, and obstetric characteristics distinguishes this research. However, we did not assess socio-economic, environmental, or genetic factors, other micronutrients, or hepcidin levels which is a key regulator of placental iron transport and materno-fetal iron transfer.

5. Conclusions

This study observed a positive trend in all the maternal iron indices in the early to mid-second trimester and a slight decline in the late second trimester among each outcome groups. Surprisingly, we found higher levels of iron indices in mothers of preterm and low birth weight neonates than mothers of term and normal birth weight neonates. Our findings emphasize the importance of monitoring and managing iron levels in pregnant women throughout pregnancy in the hope of improving maternal and neonatal health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Comparison of trends in maternal ferritin over different gestational ages across pregnancy outcomes.; Figure S2: Comparison of trends in maternal sTfR over different gestational ages across pregnancy outcomes. Table S1: Correlation between maternal iron indices at each gestational age in the second trimester with cord blood iron indices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D., M.S.S., M.B.B., S.S. G; methodology, R.D., M.S.S., M.B.B., S.S.G.; software, D.S.; validation, M.S.S.; formal analysis, J.P., D.S.; investigation, J.P., M.S.S.; resources, M.S.S.; data curation, J.P., D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.; writing—review and editing, R.D., S.YK., U.S.C., A.P.; visualization, J.P., M.S.S.; supervision, M.S.S.; project administration, S.S.G., M.B.B., M.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding; however, it was conducted as a sub-study within the RAPIDIRON Trial, which was funded by the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of KLE Academy of Higher Education and Research, Belagavi (Approval number: KAHER/EC/21-22/001).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of Women’s and Children’s Health Research Unit, Belagavi for their contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, E.; Marley, A.; Samaan, M. A.; Brookes, M. J. 1. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022, 9, e000759. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P. B.; Patel, N.; Hedges, M. A.; Benson, A. E.; Tomer, A.; Lo, J. O. Hematologic complications of pregnancy. Eur. J. Haematol. 2025,114,596-614. [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C. Iron deficiency. Blood. 2019,133,30–39. [CrossRef]

- Maršál, K. Intrauterine growth restriction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002,14,127-135. [CrossRef]

- Barker, D. J. P.; Clark, P. M. Fetal Undernutrition and Disease in Later Life. Rev Reprod. 1997,2,105-112. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M.; Abe, S. K.; Rahman, M. S.; Kanda, M.; Narita, S.; Bilano, V.; Ota, E.; Gilmour, S.; Shibuya, K. Maternal Anemia and Risk of Adverse Birth and Health Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 495–504. [CrossRef]

- Rios, E.; Lipschitz, D. A.; Cook, J. D.; Smith, N. J. Relationship of maternal and infant iron stores as assessed by determination of plasma ferritin. Pediatrics. 1975,55,694-699. PMID: 1128991.

- Van Eijk, H. G.; Kroos, M. J.; Hoogendoorn, G. A.; Wallenburg, H. C. S. Serum Ferritin and Iron Stores during Pregnancy. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1978, 83, 81–91. [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, H.; Gera, T.; Nestel, P. Effect of Iron Supplementation on Mental and Motor Development in Children: Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 117–132. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Goldenberg, R. L.; Hou, J.; Johnston, K. E.; Cliver, S. P.; Ramey, S. L.; Nelson, K. G. Cord Serum Ferritin Concentrations and Mental and Psychomotor Development of Children at Five Years of Age. J. Pediatr. 2002, 140, 165–170. [CrossRef]

- Raffaeli, G.; Manzoni, F.; Cortesi, V.; Cavallaro, G.; Mosca, F.; Ghirardello, S. Iron Homeostasis Disruption and Oxidative Stress in Preterm Newborns. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1554. [CrossRef]

- Lelic, M.; Bogdanovic, G.; Ramic, S.; Brkicevic, E. Influence of Maternal Anemia During Pregnancy on Placenta and Newborns. Med. Arh. 2014, 68, 184. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A. M.; Macdonald, D. J.; McDougall, A. N. OBSERVATIONS ON MATERNAL AND FETAL FERRITIN CONCENTRATIONS AT TERM. BJOG 1978, 85, 338–343. [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, A. P,; Charlton, R. W.; Bothwell, T. H.; Torrance, J. D. The relationship between maternal and infant iron status. Scand. J. Haematol. 1981,25,141-150. [CrossRef]

- Parks, S.; Hoffman, M.; Goudar, S.; Patel, A.; Saleem, S.; Ali, S.; Goldenberg, R.; Hibberd, P.; Moore, J.; Wallace, D.; McClure, E.; Derman, R. Maternal Anaemia and Maternal, Fetal, and Neonatal Outcomes in a Prospective Cohort Study in India and Pakistan. BJOG 2019, 126, 737–743. [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.-W.; Han, Y.-J.; Ohrr, H. Anemia before Pregnancy and Risk of Preterm Birth, Low Birth Weight and Small-for-Gestational-Age Birth in Korean Women. Eur J Clin Nutr 2013, 67, 337–342. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rosas, J. P.; De-Regil, L. M.; Garcia-Casal, M. N.; Dowswell, T. Daily Oral Iron Supplementation during Pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, 7. [CrossRef]

- Dewey, K. G.; Oaks, B. M. U-Shaped Curve for Risk Associated with Maternal Hemoglobin, Iron Status, or Iron Supplementation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1694S-1702S. [CrossRef]

- Derman, R. J.; Goudar, S. S.; Thind, S.; Bhandari, S.; Aghai, Z.; Auerbach, M.; Boelig, R.; Charantimath, U. S. RAPIDIRON: Reducing Anaemia in Pregnancy in India—a 3-Arm, Randomized-Controlled Trial Comparing the Effectiveness of Oral Iron with Single-Dose Intravenous Iron in the Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Pregnant Women and Reducing Low Birth Weight Deliveries. Trials 2021, 22, 649. [CrossRef]

- Mangla, M.; Singla, D. Prevalence of Anaemia among Pregnant Women in Rural India: A Longitudinal Observational Study. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016,5, 3500–3505. [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, G. V.; Jhancy, M.; Shivappa, P.; Bernhardt, K.; Pinto, J. R. Relationship between maternal and cord blood iron status in women and their new born pairs. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2021,14,317-322. [CrossRef]

- Swetha, K.; Tarakeswararao, P.; Saisunilkishore, M. Relationship between Maternal Iron and Cord Blood Iron Status: A Prospective Study. Indian J. Child Health. 2017, 4, 595–598. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Guillet, R.; Cooper, E. M.; Westerman, M.; Orlando, M.; Kent, T.; Pressman, E.; O’Brien, K. O. Prevalence of Anemia and Associations between Neonatal Iron Status, Hepcidin, and Maternal Iron Status among Neonates Born to Pregnant Adolescents. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Jin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Ye, R.; Liu, J.; Ren, A. Maternal Haemoglobin Concentration and Risk of Preterm Birth in a Chinese Population. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 38, 32–37. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ananth, C. V.; Li, Z.; Smulian, J. C. Maternal Anaemia and Preterm Birth: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 1380–1389. [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, K. High and Low Hemoglobin Levels during Pregnancy: Differential Risks for Preterm Birth and Small for Gestational Age. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 96, 741–748. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Teng, F.; Branch, E.; Chu, S.; Joseph, K. S. Maternal and Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality Associated With Anemia in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 1234–1244. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Kang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zeng, L.; Chen, F.; Mi, B.; Qu, P.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, Z.; Yan, H.; Wang, D.; Dang, S. Maternal Hemoglobin Concentrations and Birth Weight, Low Birth Weight (LBW), and Small for Gestational Age (SGA): Findings from a Prospective Study in Northwest China. Nutrients 2022, 14, 858. [CrossRef]

- Steer, P. J. Maternal Hemoglobin Concentration and Birth Weight. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1285S-1287S. [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, H. A.; Voorhorst, F. J.; Robertson, E. A.; Kurver, P. H. J.; Massen, C. Is Maternal Whole Blood Viscosity a Factor in Fetal Growth? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1985, 20, 145–151. [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, H. A.; Oosting, J.; Hardeman, M. R.; Smorenberg-schoorl, M. E.; Treffers, P. E. The Influence of Maternal Whole Blood Viscosity on Fetal Growth. ? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1987, 25, 187–194. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. A.; Tikmani, S. S.; Saleem, S.; Patel, A. B.; Hibberd, P. L.; Goudar, S. S.; Dhaded, S.; Derman, R. J.; Moore, J. L.; McClure, E. M.; Goldenberg, R. L. Hemoglobin Concentrations and Adverse Birth Outcomes in South Asian Pregnant Women: Findings from a Prospective Maternal and Neonatal Health Registry. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 154. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S. M.; Siraj, Md. S.; Islam, M. R.; Rahman, A.; Ekström, E.-C. Association between Maternal Plasma Ferritin Level and Infants’ Size at Birth: A Prospective Cohort Study in Rural Bangladesh. Glob. Health Action. 2021, 14, 1870421. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T. G.; Li, L.; Lee, S. J.; Hu, Y. H.; Kim, C.; Hwang, J. Y. Serum Ferritin Concentration in the Early Third Trimester of Pregnancy and Risk of Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight Based on Gestational Age. J. Korean Soc. Matern. Child Health 2021, 25, 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Sorensen, T. K.; Frederick, I. O.; El-Bastawissi, A.; King, I. B.; Leisenring, W. M.; Williams, M. A. Maternal Second-trimester Serum Ferritin Concentrations and Subsequent Risk of Preterm Delivery. Paediatric Perinatal Epid. 2002, 16, 297–304. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Kang, J.; Liu, J.; Duan, J.; Wang, F.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Xu, D.; Qu, X.; Guo, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y. Association of Low Birthweight and Small for Gestational Age with Maternal Ferritin Levels: A Retrospective Cohort Study in China. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1002702. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, R. L.; Tamura, T.; DuBard, M.; Johnston, K. E.; Copper, R. L.; Neggers, Y. Plasma Ferritin and Pregnancy Outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 175 (5), 1356–1359. [CrossRef]

- Lao, T. T. Third Trimester Iron Status and Pregnancy Outcome in Non-Anaemic Women; Pregnancy Unfavourably Affected by Maternal Iron Excess. Human Reproduction 2000, 15, 1843–1848. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Vázquez, L.; Arija, V.; Aranda, N.; Aparicio, E.; Serrat, N.; Fargas, F.; Ruiz, F.; Pallejà, M.; Coronel, P.; Gimeno, M.; Basora, J. The Effectiveness of Different Doses of Iron Supplementation and the Prenatal Determinants of Maternal Iron Status in Pregnant Spanish Women: ECLIPSES Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2418. [CrossRef]

- Oaks, B. M.; Jorgensen, J. M.; Baldiviez, L. M.; Adu-Afarwuah, S.; Maleta, K.; Okronipa, H.; Sadalaki, J.; Lartey, A.; Ashorn, P.; Ashorn, U.; Vosti, S.; Allen, L. H.; Dewey, K. G. Prenatal Iron Deficiency and Replete Iron Status Are Associated with Adverse Birth Outcomes, but Associations Differ in Ghana and Malawi. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 513–521. [CrossRef]

- Okwara, J.; Nnabuo, L.; Nwosu, D.; Ahaneku, J.; Anolue, F.; NA, O.; UK, A.; SC, M. Iron Status of Some Pregnant Women in Orlu Town-Eastern Nigeria. Niger. J. Med. 2013, 22 (1), 15–18. PMID: 23441514.

- Günther, F.; Straub, R. H.; Hartung, W.; Fleck, M.; Ehrenstein, B.; Schminke, L. Usefulness of Soluble Transferrin Receptor in the Diagnosis of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients in Clinical Practice. Int. J. Rheumatol. 2022, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Haas, J. Response of Serum Transferrin Receptor to Iron Supplementation in Iron-Depleted, Nonanemic Women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 67, 271–275. [CrossRef]

- Næss-Andresen, M.-L.; Jenum, A. K.; Berg, J. P.; Falk, R. S.; Sletner, L. The Impact of Recommending Iron Supplements to Women with Depleted Iron Stores in Early Pregnancy on Use of Supplements, and Factors Associated with Changes in Iron Status from Early Pregnancy to Postpartum in a Multi-Ethnic Population-Based Cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023, 23, 350. [CrossRef]

- Kohli, U. A.; Rajput, M.; Venkatesan, S. Association of Maternal Hemoglobin and Iron Stores with Neonatal Hemoglobin and Iron Stores. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2021, 77, 158–164. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Srivastava, S.; Verma, G. Effect of Maternal Anemia on the Status of Iron Stores in Infants: A Cohort Study. J. Fam. Community Med. 2019, 26, 118. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).