1. Introduction

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a prevalent and potentially serious condition that affects a significant number of pregnant women worldwide. It affects nearly 2 billion people worldwide, out of a global population of 7.5 billion, making it the most prevalent micronutrient deficiency [

1]. 52% of pregnant women in India are anemic, according to the NFHS-5, and in Karnataka, the prevalence of anemia was reported to be 45.7% in pregnant women and 47.8% in non-pregnant women. The prevalence of anaemia in Belgaum was found to be 44.1 % among non-pregnant women and 37.3 % among pregnant women [

2]. During pregnancy, a woman's body undergoes profound physiological changes, including an expansion of mother's blood volume and plasma to support the developing fetus [

3]. 3.46 milligrams of iron are needed for every gram of hemoglobin the mother synthesizes.

The fetus also needs iron to support metabolism, oxygen transport and relatively large accumulations of iron which will be used during the first six months of postnatal life [

4]. The placenta is an organ with a high iron requirement that is metabolically active. It can store iron in the reticuloendothelial cells. This provides a buffer during times when the mother's iron supply is insufficient [

5]. An additional gram of iron is required during pregnancy which is distributed more evenly between mother and fetus. This increased demand for red blood cells and hemoglobin can strain the body's iron reserves, which leaves pregnant women more susceptible to IDA. This can lead to maternal fatigue, weakness and a compromised immune system making the woman more susceptible to infections and illnesses. This can disrupt her ability to carry out daily activities and negatively impact her overall well-being. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the causes, risk factors and consequences of iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy as well as effective prevention and treatment strategies. The primary reasons for maintaining adequate iron levels throughout pregnancy are to safeguard the health of the mother, enhance the quality of the pregnancy and promote the development of the fetus.

Oral iron supplements are generally the first line treatment for “iron deficiency” for most women [

6]. It is recommended to take 60–120 mg of iron daily on an empty stomach in the morning to enhance absorption, preferably accompanied by ascorbic acid [

7,

8]. Previous literature suggests that the maternal indices improved after oral iron supplementation [

9]. There is limited evidence on how oral iron supplementation in anaemia affects the iron indices at specific time intervals during pregnancy. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to present a brief overview regarding oral iron treatment throughout pregnancy and to understand which phase of pregnancy could result in maximum changes in the iron indices. Hence the objective of this paper is to study the trajectories of iron indices in moderately anemic pregnant women receiving oral iron supplementation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population

All pregnant women who visited Community Health Centre (CHC) and its Primary Health Centres (PHCs) in the rural areas of Belgaum, Karnataka, India were screened at around 12–16 weeks of pregnancy. The inclusion criteria were: pregnant women with gestational age of 12-16 weeks, age between 18–40 years, hemoglobin level between 7–9.9 g/dL (moderate anaemia), and serum ferritin < 30 ng/mL and/or TSAT < 20%. Participants with twin pregnancy, any congenital anomaly, anemia other than iron deficiency were excluded. Out of 367 eligible pregnant women, 315 women who consented to the study were enrolled using a consecutive sampling technique.

2.2. Sample Size

The sample size of 315 was determined by assuming a prevalence of 37.3% of anemia among pregnant women, a 95% confidence interval corresponding to 1.96 alpha, and the margin of error to be 15%, with 10% attrition [

2].

2.3. Study Procedure

This prospective cohort study was conducted from August 2021 to September 2023 according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving humans were approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of KLE Academy of Higher Education and Research (KAHER), Belgaum (KAHER/EC/21-22/001) nested within the RAPIDIRON Trial conducted at the Women's and Children's Health Research Unit of Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Karnataka [

10]. Informed written consent was taken from every individual participating in the study in local languages (Kannada and Marathi). Blood samples were collected and a questionnaire about sociodemographic characteristics with vital statistics and iron-folic acid compliance were also noted.

2.4. Treatment Dosage

All participants enrolled for this study were given single dose of deworming medication (Albendazole–400 mg) as per government guidelines and also received Iron (60 mg Ferrous sulphate) and folic acid (400 mcg) tablets consistent with the most recent Anemia Mukt Bharat treatment guideline [

11]. The administration of tablets for the treatment of anaemia involved, twice a day regimen. However, if the hemoglobin levels reached a normal range suitable for pregnancy by 26-30 weeks, specifically >11 g/dL, the tablets were then given at a prophylactic dose of once daily.

2.5. Analysis of Samples

Venous blood samples (2 mL in EDTA and 2 mL in a clot activator tube) were collected at multiple time points during pregnancy to assess the trajectories of blood iron indices. Sampling began at 12–16 weeks of gestation, followed by subsequent collections at 20–24 weeks, 26–30 weeks and 30–34 weeks with the final sample obtained on the day of delivery. After the sample collection, samples were transported to the tertiary care hospital laboratory by specimen transport box with ice-packs ensuring the quality of samples is not compromised. The blood parameters include serum iron, transferrin saturation (TSAT), total iron Binding capacity (TIBC), ferritin and were immediately analysed by Roche-Cobas-6000. Hemoglobin, reticulocyte-hemoglobin (Ret-Hb), immature reticulocyte fraction (IRF), Complete blood count were analysed in Sysmex-Hematology analyser. A subset of 105 samples of serum sTfR (soluble transferrin receptor) was also analysed using a sandwich ELISA method.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All the continuous variables were summarized using Mean/SD or Median (Q1, Q3) depending upon normality of the data. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality. All the categorical variables were summarized using frequency and percentage. Parameters with Two-time point were analysed using Paired-t-test or Wilcoxon Matched-pair signed-rank test. One way Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (RM-ANOVA)/ Friedman’s nonparametric test was used to compare the average maternal indices more than two time points. Post hoc analysis was carried out to adjust for Bonferroni corrections. Box plots were constructed to visualize the trends in the average maternal indices over the period. Imputation for missing data of continuous variables was done using a mean imputation method and assuming missing of 5-10%. All the statistical analyses were done using R software version 4.2.3 and a p-value less than 5% was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

The baseline and socio-demographic characteristics of the 315 pregnant women who participated in the study is represented in

Table 1. Most participants were between 18-25 years old (73.3%), with smaller proportions aged between 26–30 years (19.0%) and 31 years or older (7.6%). Maternal Hb at 12-16 weeks or recruitment showed median Hb of 9.36 (Q1: Q3, 8.55: 9.74). Based on body mass index (BMI), 33.7% of pregnant women were underweight, 58.1% had a normal weight, 7.0% were overweight and 1.3% of the pregnant women were classified as obese. Blood pressure readings showed a median systolic and diastolic blood pressure of 101 (Q1:Q3, 94:109) and 64 (Q1:Q3, 60:70) mm Hg respectively. 42.5% of the women were nulliparous, 28.6% were Primiparous, and 28.9% were multiparous. Based on dietary habits, 7.3% were vegetarians, 14.9% were lacto-vegetarians, 17.1% were ova-vegetarians and 60.6% predominantly ate a mixed diet.

Our study of 315 participants demonstrates a complete adherence (>75%) of 95.3% for iron and 97.8% to folic acid supplementation throughout pregnancy. Moderate adherence (50–75%) was observed in 15 (4.7%) of the pregnant women who used oral iron and 7 (2.2%) for ingestion of folic acid tablet. A majority of pregnant women were compliant to oral and folic acid tablets. However, a small percentage of pregnant women 17 (5.39%) and 11 (3.49%) were non-adherent to iron and folic acid respectively.

The predominant reason for not taking iron tablets was that the tablets made them feel sick, reported by 14 women (4.44%). Similarly, 8 women (2.54 %) reported the same for folic acid tablets. 2 women (0.63%) reported forgetting to take both iron and folic acid tablets. Only one woman (0.32%) stated that she was unable to understand the instructions for taking both tablets. No participant reported losing or misplacing their tablets as a reason for non-compliance. These findings highlight the necessity of managing side effects and improving the awareness to increase 100% adherence among pregnant women which are depicted in

Table 2.

Various side effects experienced by participants after taking iron tablets were also noted. 118 of the 315 pregnant women reported side effects, of those, 43 (13.65%) indicated vomiting, 38 (12.06%) experienced nausea or stomach upset, 13(4.13%) had diarrhea and 6 (1.90%) reported faintness. In addition, 15 (4.76%) experienced constipation, while 3 (0.95%) complained of vaginal bleeding.

3.1. Changes in Maternal Red Cell Indices During Pregnancy

The significant changes observed in red cell indices in early second trimester and 26–30 weeks of pregnancy are represented in

Table 3. Red Blood Cell (RBC) count decreased significantly from 4.19 million cells/µL at 12–16 weeks GA to 4.05 million cells/µL at 26–30 weeks GA (p < 0.001). Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) showed a notable increase from 72.16 to 83.47 fL. Similarly, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) rose from 22.44 to 26.77 pg, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) from 31.03 to 32.01 g/dL between 12–16 weeks and 26–30 weeks of gestation, all changes being statistically significant (p<0.001). Red cell distribution width (RDW) percentage remained similar at both time points. Hematocrit (HCT) levels were higher at 26–30 weeks (33.71%) compared to 12–16 weeks (29.93%), reticulocyte hemoglobin (Ret-Hb) assay showed significant rise from 23.30 to 27.84 pg, Additionally, immature reticulocyte fraction (IRF) slightly increased from 6.90% to 7.30% over the same period, with all increases being significant (p<0.001). The most marked changes occurred in blood concentrations of MCV, MCH and in reticulocyte hemoglobin (Ret-Hb).

3.2. Trajectory or Trends of Maternal Iron Indices During Pregnancy

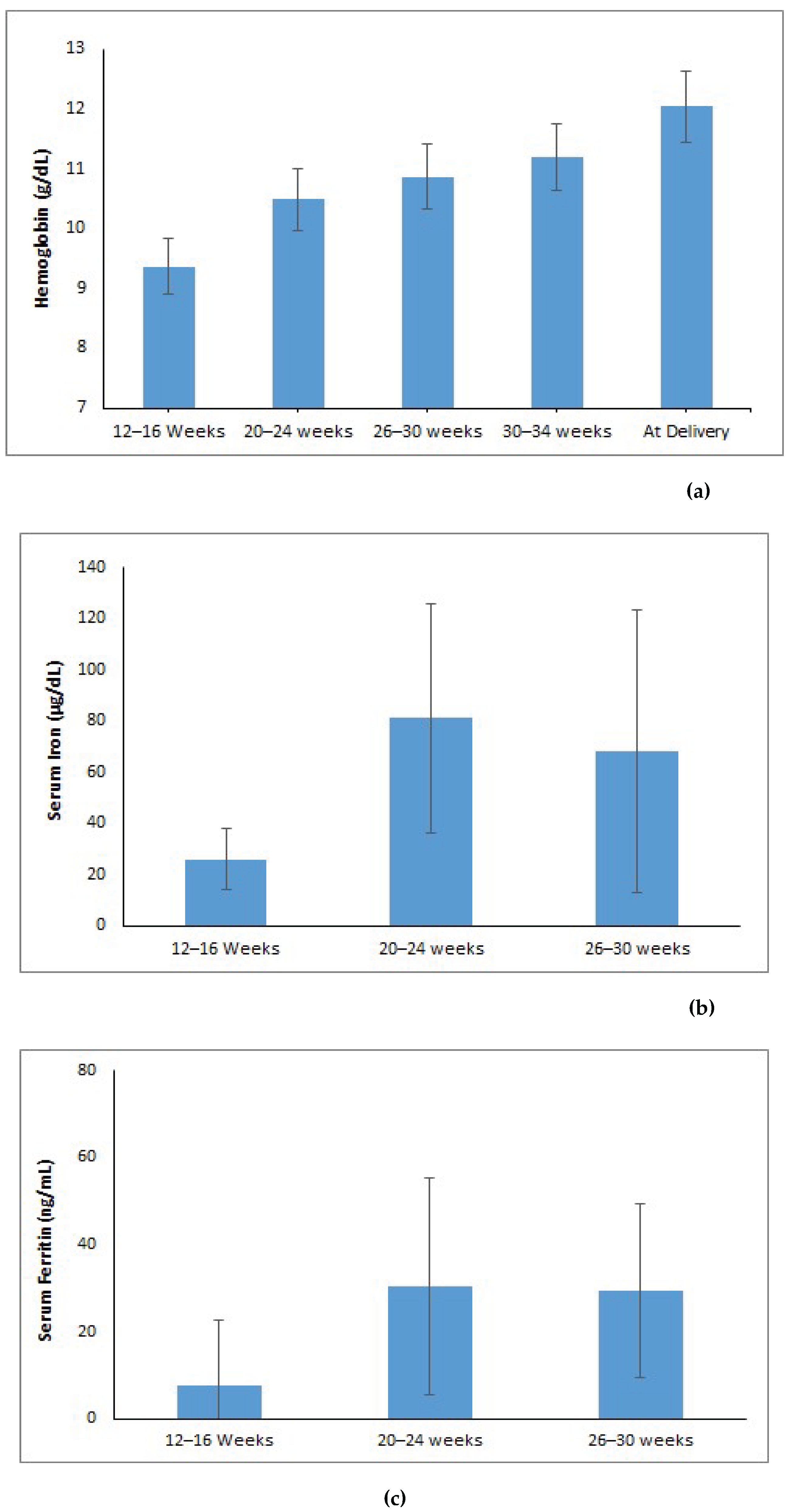

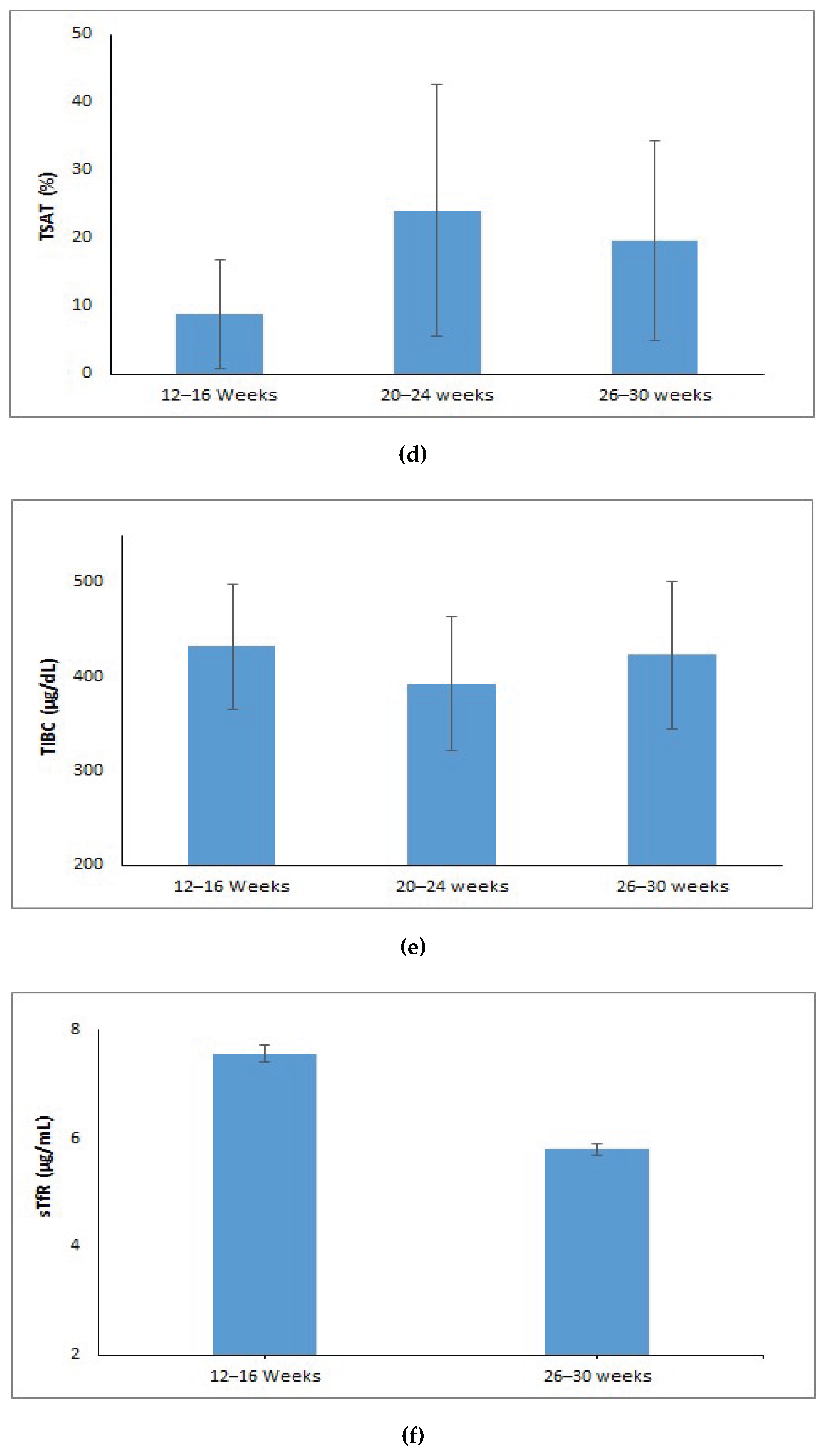

The hemoglobin levels showed a notable increase from 9.36 g/dL at 12–16 weeks gestational age (GA) to 12.03 g/dL at delivery (p < 0.001) (Figure 1a). Serum iron levels dropped to 68 µg/dL at 26–30 weeks gestational age after increasing significantly from 26 µg/dL during the 12–16 week period to 81 µg/dL in the 20–24 week period (p < 0.001) (Figure 1b). The levels of serum ferritin increased significantly from 7.58 ng/mL at 12–16 weeks to 30.35 ng/mL at 20–24 weeks and then stabilized at 29.45 ng/mL at 26–30 weeks (p < 0.001) (Figure1c). Transferrin saturation (TSAT) improved from 5.88% at 12–16 weeks to 20.58% at 20–24 weeks, then slightly decreased to 16.58% at 26-30 weeks GA (p < 0.001) (Figure 1d). Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) decreased from 432 µg/dL at 12–16 weeks to 392 µg/dL at 20–24 weeks, and then increased to 423 µg/dL at 26–30 weeks (p < 0.001) (Figure 1e). Soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) levels significantly dropped from 7.55 µg/mL at 12–16 weeks to 5.79 µg/mL by 26–30 weeks GA (p < 0.001) (Figure 1f).

Post hoc comparisons adjusted for Bonferroni corrections were performed for those maternal iron indices (hemoglobin, iron, ferritin, TIBC, TSAT) which were statistically significant. The post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in the average hemoglobin, iron, TSAT between the gestational ages of 12–16 week and 20–24 week (p <0.05), whereas, TIBC showed significant differences across 20–24 and 26–30 weeks of gestation, but showed no substantial difference between 12–16 week and 26–30 week (p=1.00). Additionally, analysis for ferritin showed no significant difference at 20–24 week and 26–30week of gestational age (p=0.98), but did show a statistical difference across other gestational ages (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Trends of maternal iron indices over different gestational age (weeks): (a) Hemoglobin (g/dL); (b) Serum Iron (µg/dL); (c) Ferritin (ng/mL); (d) TSAT (%); (e) Serum TIBC (µg/dL); (f) sTfR (µg/mL).

Figure 2.

Trends of maternal iron indices over different gestational age (weeks): (a) Hemoglobin (g/dL); (b) Serum Iron (µg/dL); (c) Ferritin (ng/mL); (d) TSAT (%); (e) Serum TIBC (µg/dL); (f) sTfR (µg/mL).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Main Findings

We investigated the hematologic response to oral iron supplementation in moderate iron-deficient pregnant women and observed significant improvements in the concentrations of both hematologic and biochemical parameters during pregnancy. The current study reported an adherence rate of 95.3% for iron and 97.8% to folic acid supplementation throughout the pregnancy. Moderate adherence was observed in 4.7% of the pregnant women for iron and 2.2% for folic acid tablet. This high adherence is crucial for the effectiveness of supplementation programs. A similar adherence rates has been reported in study conducted in another region [

12]. Although we did not examine the relationship between antenatal care visits and adherence to iron tablets, previous research has shown that attending four or more prenatal care visits is associated with improved adherence of iron supplements during pregnancy [

13].

A study conducted in Northern Ghana reported an adherence rate of 84.5% for iron and folic acid supplementation (IFAS) among pregnant women [

14]. An evaluation of adherence to IFAS among pregnant women at a tertiary care centre found that 63.8% of participants followed the recommended supplementation guidelines [

15]. However, one study reported a much lower adherence rate of 28.7% for IFA tablets, adding that adherence rates were lower due to socioeconomic differences, data collection methods, healthcare professional training and varying healthcare institution standards across facilities [

16]. These variations highlight the need to address region-specific barriers to improve adherence rates universally. Given that, side effects reported by participant (tablets made me feel sick) was the main reason for small number of non-compliance with iron supplementation in this population. Encouraging them to take the pills with food may alleviate these symptoms [

17]. Furthermore, forgetfulness is a barrier to iron supplementation for some women, it is very important to provide education during prenatal visits on strategies to assist study participants to take their tablets. For instance, placing the tablets in a daily visible location, such as on a kitchen counter or night table, as advised by earlier authors can be beneficial [

18].

The improvements in maternal iron indices observed in our study are consistent with findings from other research. A steep increase in hemoglobin levels of participants was observed from the early second trimester to delivery. This is in line with the study by Fisher and Nemeth, who reported significant increases in hemoglobin levels following iron supplementation in pregnant women with IDA [

3]. Our study findings support the evidence that iron supplementation effectively enhances maternal hematologic status. Our study documented that in the early third trimester of pregnancy, there is a notable increase in hematocrit, hemoglobin concentration and other red cell indices. This rise can be linked to a reduced expansion of plasma volume, and is particularly evident in pregnant women who use iron supplements. A study has shown that pregnant women who take iron supplementation tend to have elevated levels of hematocrit, hemoglobin concentration, and red cell count compared to those who do not consume iron supplements. These findings emphasize the importance of considering iron intake for maternal health during pregnancy [

19].

We found MCV, MCH and MCHC values were low in the early second trimester and observed a significant increase during early third trimester. Similarly, a gradual rise in MCV and MCH from early pregnancy until delivery was observed in another study [

20]. The expansion of plasma volume and higher nutritional demands are the main causes of the initial lower level of MCV, MCH and MCHC values during the early first trimester. These parameters rise as pregnancy progresses into the early third trimester (enhanced erythropoiesis, iron supplementation, and other physiological adaptations) in order to support the developing demands of the fetus and get the mother's body ready for delivery [

21]. This study found that RDW (%) remained stable during pregnancy, aligning with study on Sudanese pregnant women which reported RDW as less sensitive to iron status changes than serum ferritin [

22]. The study also noted no significant variations in MCV, MCH and RDW as these parameters reflect averages and may not capture minor cell size changes especially in early iron deficiency. A Cochrane review suggested that the lack of RDW response to oral iron supplementation (daily or intermittent) may result from the body's homeostatic regulation of red cell production during pregnancy [

23].

IRF and Ret-Hb are newer, sensitive measures of erythropoiesis [

24]. IRF reflects bone marrow activity but does not indicate iron incorporation into developing RBCs. In cases like bleeding, IRF may increase without a corresponding rise in hemoglobin [

25]. Ret-Hb, on the other hand measures hemoglobin content in newly produced RBCs serving as a real-time indicator of iron availability for erythropoiesis. Unlike acute-phase reactants, Ret-Hb is effective in detecting responses to iron therapy and is a more reliable measure of iron supply [

26]. Our study showed a drastic increase in Ret-Hb and IRF levels from baseline to the early third trimester. Use of Ret-Hb as a parameter to predict early response to exclusive oral iron therapy in children revealed that the mean Ret-Hb before treatment was 18.20 pg. After iron supplementation, it increased to 21.48 pg and then to 25.43 pg at two different time points. The researchers concluded that an increase in Ret-Hb implies that iron supplementation improves erythropoiesis [

27]. Our study we found an initial rise in median iron, ferritin, and TSAT from baseline to 20–24 weeks of gestation. Ferritin remained stable at 26–30 weeks, while iron and TSAT decreased to a smaller extent. TIBC slightly decreased during 20–24 weeks and raised significantly during 26–30 weeks. In contrast with our findings a study reported that ferritin, iron, and TSAT levels decreased, and TIBC increased from early to late pregnancy [

28]. There was an initial increase in serum iron and TSAT with daily iron supplementation, these levels plateaued or slightly decreased in the later stages of pregnancy [

7].

A study revealed that hemoglobin concentration, serum iron, ferritin levels and red blood cell count all experienced a significant decline in the third trimester of pregnancy compared to the first and second trimesters. On the other hand, compared to the first and second trimesters, the third trimester had significantly greater levels of TIBC, transferrin and sTfR: ferritin ratio [

29]. It is established that serum sTfR levels is a sensitive and specific indicator of cellular iron need. Because it increases in situations where erythropoiesis is enhanced and tissue iron levels are low, this marker is especially helpful for identifying iron deficiency during pregnancy [

30]. A study by Carriaga et al. reported that pregnant women's sTfR levels elevated from 5.36 mg/L around 28–32 weeks to 6.21 mg/L around 36–40 weeks of gestation [

31]. However, in this study, we found a decrease in the sTfR levels from 7.55 µg/mL at 12–16 weeks to 5.79 µg/mL at 26–30 weeks. The possible reason for decrease in the sTfR level may be related to how the body might utilize and store iron during second and third trimester. A haemodilution effect, enhanced overall nutrition or good adherence for the oral iron supplementation which can lead to improved body iron status.

4.2. Strength and limitations

This study included multiple hematological and biochemical markers to assess the response to oral iron supplementation, thus providing a thorough understanding of iron status during pregnancy. Our study found statistically significant changes in key hematological indices including hemoglobin, hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC and sTfR with a high adherence rate to IFA supplementation, confirming its efficacy. The study was conducted on a moderately anemic participant who were iron deficient in a single location, and the heterogeneity in adherence and responsiveness to iron supplementation observed might limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population and to other geographic areas. Additionally, this study did not follow up with participants until 6 weeks postpartum to assess the long-term impact of iron supplementation on maternal and infant health.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated progressive improvement in iron and red cell indices among moderately anemic pregnant women receiving daily IFA supplementation, with significant gains from the second to early third trimester and stabilization towards term. These findings highlight the need for trimester-specific monitoring of iron status, early initiation of antenatal care, and strengthened adherence counselling. Implementing these strategies may improve maternal hematologic status and may contribute to better pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D., M.S.S., M.B.B., and S.S.G.; methodology, R.D., M.S.S., M.B.B., and S.S.G.; software, M.S.D.; validation, M.S.S.; formal analysis, J.P.A. and M.S.D.; investigation, J.P.A. and M.S.S.; resources, M.S.S.; data curation, J.P.A. and M.S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.A.; writing—review and editing, R.D., S.Y., U.C., and A.P.; visualization, J.P.A. and M.S.S.; supervision, M.S.S.; project administration, S.S.G., M.B.B., and M.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding; however, it was conducted as a sub-study within the RAPIDIRON Trial, which was funded by the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the KLE Academy of Higher Education and Research, Belagavi (approval number: KAHER/EC/21-22/001).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to all members of the Women’s and Children’s Health Research Unit, Belagavi and especially thank Dr. Kiran P. Nadgauda and Mr. Rama Magdum for their valuable contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Iron deficiency anemia. assessment, prevention, and control. A guide for programme managers. 2001,47-62.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India (2021) National Family Health Survey 5. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-OF43-Other-Fact-Sheets.cfm (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Fisher, A.L.; Nemeth, E. Iron Homeostasis during Pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr 2017, 106, 1567S-1574S. [CrossRef]

- Fa, O.; Naiman, J.L. Hematologic Problems in the Newborn. Major Probl Clin Pediatr 1982, 4, 1–360. PMID: 6182425.

- McArdle, H.J.; Gambling, L.; Kennedy, C. Iron Deficiency during Pregnancy: The Consequences for Placental Function and Fetal Outcome. Proc Nutr Soc 2013, 73, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Brittenham, G. Disorders of iron metabolism: iron deficiency and overload. Hematology: basic principles and practice. 7th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2018, pp. 478-490.

- Stoffel, N.U.; von Siebenthal, H.K.; Moretti, D.; Zimmermann, M.B. Oral Iron Supplementation in Iron-Deficient Women: How Much and How Often?. Mol Aspects Med 2020, 75, 100865. [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, M. Optimizing Diagnosis and Treatment of Iron Deficiency and Iron Deficiency Anemia in Women and Girls of Reproductive Age: Clinical Opinion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2023, 162, 68–77. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rosas, J.P.; De-Regil, L.M.; Garcia-Casal, M.N.; Dowswell, T. Daily Oral Iron Supplementation during Pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, 7. [CrossRef]

- Derman, R.J.; Goudar, S.S.; Thind, S.; Bhandari, S.; Aghai, Z.; Auerbach, M. RAPIDIRON: Reducing Anaemia in Pregnancy in India—a 3-Arm, Randomized-Controlled Trial Comparing the Effectiveness of Oral Iron with Single-Dose Intravenous Iron in the Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Pregnant Women and Reducing Low Birth Weight Deliveries. Trials 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Anemia Mukt Bharat. Available online: https://anemiamuktbharat.info/programme/interventions#link-1 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Beressa, G.; Lencha, B.; Bosha, T.; Egata, G. Utilization and Compliance with Iron Supplementation and Predictors among Pregnant Women in Southeast Ethiopia. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1, 16253. [CrossRef]

- Molla, T.; Guadu, T.; Muhammad, E.A.; Hunegnaw, M.T. Factors Associated with Adherence to Iron Folate Supplementation among Pregnant Women in West Dembia District, Northwest Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional Study. BMC Res Notes 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Haruna S.; Patience Kanyiri G.; Mogre, V. Adherence to Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation among Pregnant Women from Northern Ghana. Nutr Metab Insights 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Jayalakshmy, R.; Lavanya, P.; Rajaa, S.; Mahalakshmy, T. Adherence to Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation among Antenatal Mothers Attending a Tertiary Care Center, Puducherry: A Mixed-Methods Study. J Family Med Prim Care 2020, 9, 5205–5211. [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, G.; Atenafu, A.; Dagne, H.; Dagnew, B. Adherence to Iron and Folic Acid Supplement and Its Associated Factors among Antenatal Care Attendant Mothers in Lay Armachiho Health Centers, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2017. Int J Reprod Med 2019, 2019, 1–9, 5863737. [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, E.; Olibe, A.; Obi, S.; Ugwu, A. Determinants of Compliance to Iron Supplementation among Pregnant Women in Enugu, Southeastern Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2014, 17, 608–612. [CrossRef]

- Habib, F.; Habib Zein Alabdin, E.; Alenazy, M.; Nooh, R. Compliance to Iron Supplementation during Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 2009, 29, 487–492, . [CrossRef]

- Oshodi, Y.A.; Fabamwo, A.O.; Akinola, O.I. Haematological Indices in Pregnancy and Puerperium. Int J of Curr Res 2017, 9, 54712–54721.

- Davidson, R.J.; Hamilton, P.J. High Mean Red Cell Volume: Its Incidence and Significance in Routine Haematology. J Clin Pathol 1978, 31, 493–498, . [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Tripathi, A.K.; Mishra, S.; Amzarul, M.; Vaish, A.K. Physiological Changes in Hematological Parameters during Pregnancy. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2012, 28, 144–146. [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, E.G.; Gasim, G.I.; Musa, I.R.; Elbashir, L.M.; Adam, I. Red Blood Cell Distribution Width and Iron Deficiency Anemia among Pregnant Sudanese Women. Diagn Pathol 2012, 7, 168. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rosas, J.P.; De-Regil, L.M.; Gomez Malave, H.; Flores-Urrutia, M.C.; Dowswell, T. Intermittent Oral Iron Supplementation during Pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.H.; Ornvold, K.; Bigelow, N.C. Flow Cytometric Reticulocyte Maturity Index: A Useful Laboratory Parameter of Erythropoietic Activity in Anemia. Cytometry 1995, 22, 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Goyal, L.; Kaushik, D.; Gulati, S.; Sharma, N.; L Harshvardhan; Gupta, N. Reticulocyte Hemoglobin vis-à-vis Immature Reticulocyte Fraction, as the Earliest Indicator of Response to Therapy in Iron Deficiency Anemia. J Assoc Physicians India 2017, 65, 14–17. PMID: 31556266.

- Mast, A.E.; Blinder, M.A.; Lu, Q.; Flax, S.; Dietzen, D.J. Clinical Utility of the Reticulocyte Hemoglobin Content in the Diagnosis of Iron Deficiency. Blood 2002, 99, 1489–1491. [CrossRef]

- Parodi, E.; Giraudo, M.T.; Ricceri, F.; Aurucci, M.L.; Mazzone, R.; Ramenghi, U. Absolute Reticulocyte Count and Reticulocyte Hemoglobin Content as Predictors of Early Response to Exclusive Oral Iron in Children with Iron Deficiency Anemia. Anemia 2016, 1, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Noshiro, K.; Umazume, T.; Hattori, R.; Kataoka, S.; Yamada, T.; Watari, H. Hemoglobin Concentration during Early Pregnancy as an Accurate Predictor of Anemia during Late Pregnancy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 839. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jong-I. m; Kang, S.A. h; Kim, Soon-K. i; Lim, H.-S. A Cross Sectional Study of Maternal Iron Status of Korean Women during Pregnancy. Nutr Res 2002, 22, 1377–1388. [CrossRef]

- J P Akshay Kirthan; Somannavar, M.S. Pathophysiology and Management of Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Pregnancy: A Review. Ann Hematol 2023, 103, 2637–2646. [CrossRef]

- Carriaga, M.T.; Skikne, B.S.; Finley, B.; Cutler, B.; Cook, J.D. Serum Transferrin Receptor for the Detection of Iron Deficiency in Pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr 1991, 54, 1077–1081. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).