Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

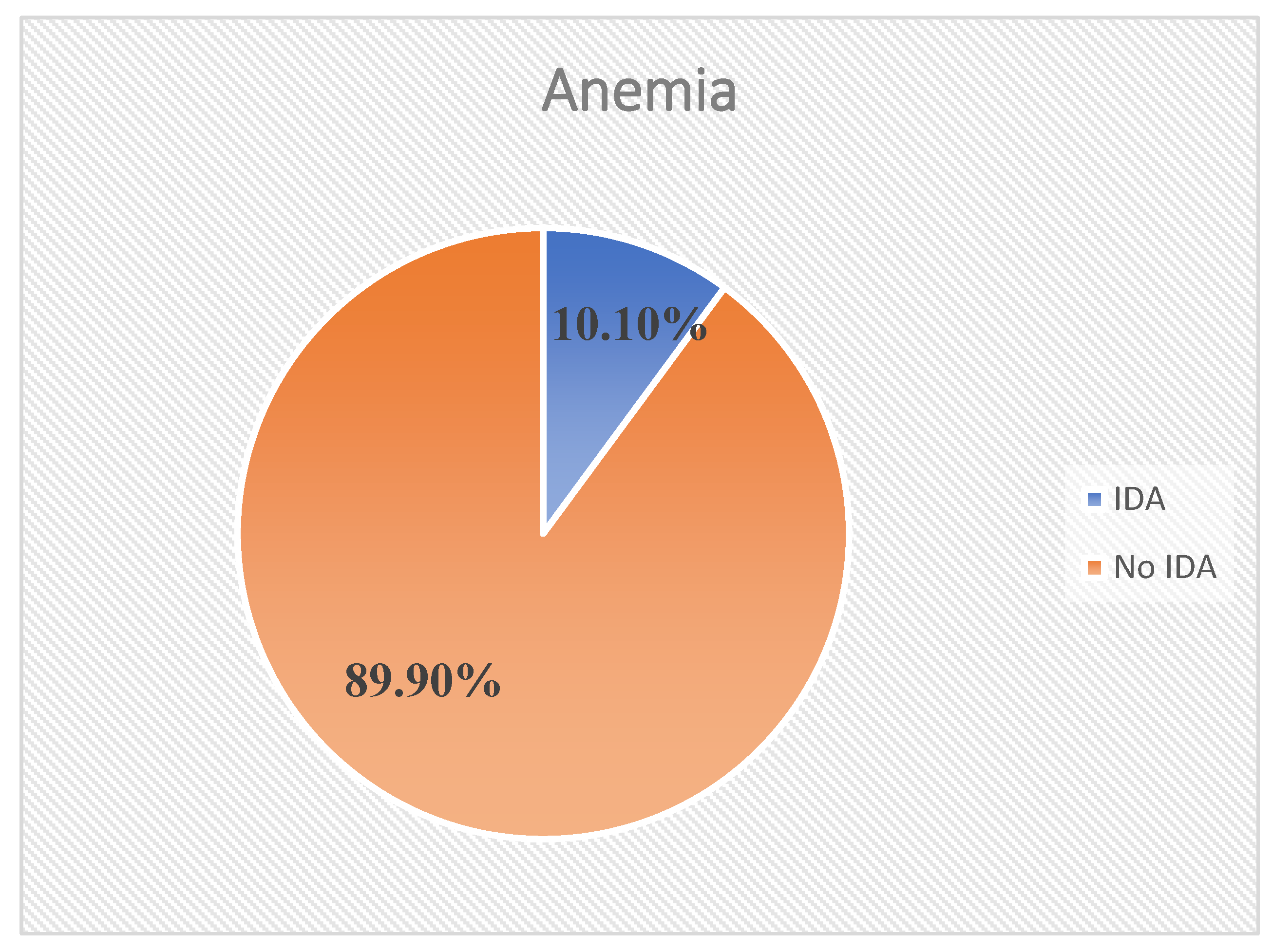

Purpose: Iron deficiency Anemia (IDA) is the most widespread nutritional problem in the world causing 75% of anemia among pregnant women. Despite the wider scope of the problem, limited evidence has been documented to disclose the magnitude of Iron deficiency anemia and associated factors in women attending Antenatal care unit in Ethiopia, including the study area. Methods: Facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted among randomely selected 169 pregnant women attending antenatal care unit from July 01 to August 30, 2023 in Nekemte Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Nekemte, Western Oromia. The data was collected using pretested structured questionnaires. Hemolobin, mean cell volume and mean cell hemoglobin concentration were measured using automated, quality-controled hematology analyzer (Japan, Sysmex corporation). After collection, the data was entered into Epi Data version 4.6 and analyzed using Statistical Software for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24. Bi-variable and multivariable binary logistic regression analysis were performed to identify predictors of IDA. Adjusted odd ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed to measure the strength of the association between dependent and independent variables. Level of statistical significance was declared at pvalue <0.05. Finally, the results were presented using text, tables, and charts. Result: The magnitude of iron deficiency anemia using a cut off level mean cell volume (MCV)<80fl and mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) < 32g/dl was 10.06% (95%CI: 6.2%-15.3%). History of chronic illness (AOR=4.62; 95%CI: 1.54-13.81), undernutrition (MUAC<23) (AOR=3.84; 95%CI: 1.14-12.94)] and initiation of ANC at second trimester (AOR=4.94; 95%CI: 1.37, 17.79) showed significant association with iron deficiency anemia among pregnant Women. Conclusion: The magnitude of iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women in this study was mild. Having history of chronic illness, mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) <23cm and initiation of antenatal care at second trimester were significant predictors of IDA among pregnant women. Thus, regular medical checkup, early initiation of antenatal care and providing information on dietary diversity practice are vital to prevent IDA among pregnant women in the study area.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods And Materials

Study Area, Period and Design

Population and Eligibility Criteria

Study Variables

Data Collection Tool and Procedure

Blood Sample Collection and Analysis

Data Management and Quality Assurance

Data Management

Operational Definitions

Quality Assurance

Data Processing and Analysis

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Subject

Reproductive Characteristics of Respondents

Nutritional and Health Related Factors of Respondents

Laboratory Findings

Magnitude and Severity of Iron Deficiency Anemia among Pregnant Women

Factors Associated with Iron deficiency Anemia among Pregnant Women

Discussion

Limitations

- ❖ Serum ferritin level which is the most appropriate test for the diagnosis of IDA was not measured, because of its cost and unavailability of the test in our set up.

- ❖ Dietary intake was assessed by using food frequency questionnaire which is less sensitive to measures absolute intake of specific nutrients and it mostly relies on respondent’s memory so it is prone to recall bias.

- ❖ As this study was institutional-based and cross-sectional nature of the study design, an adjustment was not made for altitude because the participants come from different areas.

Conclusions

Recommendations

- ❖ Nekemte Comprehensive Specialized Hospital management should strengthen a follow up mechanism to ensure quality service given to pregnant women attending ANC.

- ❖ They should provide information on the importance of regular medical checkup in order to take preventive measures and stay health throughout pregnancy.

- ❖ They should provide timely and appropriate information on the importance of timely initiation of ANC and diversified feeding practice for all pregnant women attending ANC at their Hospital.

- ❖ Appropriate information on the importance of timely initiation of ANC, regular medical checkup and diversified feeding practices for the community especially for all reproductive age groups should be provided.

- ❖ Health education and counseling services should be provided for all pregnant women at the community level to stay health throughout pregnancy.

- ❖ They should strictly follow the information provided by Health Professionals on identified interventions.

- ❖ Further research on risk factors of IDA which include micro-nutrient deficiencies to identify the underlying problems and its effect on pregnant women and fetal outcome is needed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations/Acronyms

| ANC | Antenatal Care |

| AOR | Adjusted Ods Ratio |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CBC | Complete Blood Count |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| EDTA | Ehylene Diamine Tetra Acetate |

| Hgb | Hemoglobin |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IDA | Iron Deficiency Anemia |

| MCH | Maternal and Child Health |

| MCHC | Mean Cell Hemoglobin Concentration |

| MCV | Mean Cell Volume |

| MDD | Minimum Dietary Diversity |

| MUAC | Mid Upper Arm Circumference |

| RBC | Red Blood Cell |

| SPSS | Statististical Software for Social Science |

References

- B. M. Labib, H.; K. Ahmed, A.; A. Abd El-Moaty, M. Effect of Moderate Iron Deficiency Anemia During Pregnancy on Maternal and Fetal Outcome. Al-Azhar Med. J. 2022, 51, 1075–1086. [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.A.; Rashid, N.; Mengal, M.A.; Hasni, M.S.; Khan, G.M.; Shawani, N.A.; Ali, I.; Sheikh, I.S.; Khan, N. Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Women of Reproductive Age in Urban Areas of Quetta District, Pakistan. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khaffaf, A.; Frattini, F.; Gaiardoni, R.; Mimiola, E.; Sissa, C.; Franchini, M. Diagnosis of anemia in pregnancy. J. Lab. Precis. Med. 2020, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rets, A. Laboratory approach to investigation of anemia in pregnancy. Int. J. Lboratory Hematol. 2021, 43, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, E.; Marley, A.; Samaan, M.A.; Brookes, M.J. Iron deficiency anaemia: Pathophysiology, assessment, practical management. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, S.; Cacciato, P.M.; Certelli, C.; Salvaggio, C.; Magliarditi, M.; Rizzo, G. Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy: Novel approaches for an old problem. Oman Med. J. 2020, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Ouf, N.M.; Jan, M.M. The impact of maternal iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia on child’s health. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hospital, S.M.; Hospital, J.R. Anaemia in pregnancy. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2016, 77, 584–588. [Google Scholar]

- Resseguier, A.; Guiguet-auclair, C.; Debost-legrand, A.; Gerbaud, L.; Vendittelli, F.; Ruivard, M. Prediction of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Third Trimester of Pregnancy Based on Data in the First Trimester : A Prospective Cohort Study in a High-Income Country. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fite, M.B.; Assefa, N.; Mengiste, B. Prevalence and determinants of Anemia among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Arch. Public Heal. 2021, 79, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, S.L.; Lim, L.M.; Chan, S.; Tan, P.T.; Chee, Y.L.; Quah, P.L.; Kok, J.; Chan, Y.; Tan, K.H.; Yap, F.; et al. Iron status and risk factors of iron deficiency among pregnant women in Singapore : a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Huo, C. Risk factors for iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women from plateau region and their impact on pregnancy outcome. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 4146–4153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jamnok, J.; Sanchaisuriya, K.; Sanchaisuriya, P.; Fucharoen, G.; Fucharoen, S. Factors associated with anaemia and iron deficiency among women of reproductive age in Northeast Thailand : a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayyari, A.; Public, B.M.C.; Bayyari, N. Al; Sabbah, H. Al; Hailat, M.; Aldahoun, H.; Samra, H.A. Dietary diversity and iron deficiency anemia among a cohort of singleton pregnancies : a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashi Bhushan Kumar, Shanvanth R. Arnipalli, Priyanka Mehta, S.C. and O.Z.* Iron Deficiency Anemia : Efficacy and Limitations of Nutritional and Comprehensive Mitigation Strategies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, J.P.; Sesay, F.; Mbai, J.; Ali, S.I.; Donkor, W.E.S.; Woodruff, B.A.; Pilane, Z.; Mohamed, K.; Ahmed, M.; Hamda, M.; et al. Risk factors of anaemia and iron deficiency in Somali children and women : Findings from the 2019 Somalia Micronutrient Survey. Matern. Child Nutr. 2022, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiu, O.R.; Dada-adegbola, H.; Kosoko, A.M.; Falade, C.O.; Arinola, O.G.; Odaibo, A.B.; Ademowo, O.G. Contributions of malaria, helminths, HIV and iron deficiency to anaemia in pregnant women attending ante-natal clinic in SouthWest Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2020, 20, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serbesa, M.L.; Maleda, S.; Iffa, T. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Prevention of Iron Deficiency Anemia Among Pregnant Women Attending Ante-Natal Care Unit at Public Hospitals of Harar Town, Eastern Ethiopia : Institutional Based Cross-Sectional Study. Med. andBiophysics 2019, 53, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fite, M.B.; Bikila, D.; Habtu, W.; Tura, A.K.; Yadeta, T.A. Beyond hemoglobin : uncovering iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia using serum ferritin concentration among pregnant women in eastern Ethiopia : a community - based study. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessalegn, F.N. iMedPub Journals Prevalence of Iron Deficiency Anemia and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Follow up at Dodola General Hospital West Arsi Zone Oromia Region South East Ethiopia Abstract Prevalence of iron deficiency anemia. iMedPub J. 2021, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Laelago, F.; Paulos, W.; Handiso, Y.H. Prevalence and predictors of iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women in Bolosso Bomibe district, Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia Community-based cross-sectional study public health Prevalence and predictors of iron deficiency anemia among pregnant w. Cogent Public Heal. 2023, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, W.; Belachew, T.; Wolide, A.D. Burden and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care in southern Ethiopia : cross sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argaw, D.; Kabthymer, R.H.; Birhane, M. Magnitude of anemia and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J. Blood Med. 2020, 11, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensa, T.; Id, G.; Id, S.G.; Omigbodun, A.O. Prevalence and predictors of anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia : Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2022, 61, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NI Ugwu, C.U. Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnancy in Nigeria—A Systematic Review. 2020, 889–896.

- .Alaofè, H.; Burney, J.; Naylor, R.; Taren, D. Prevalence of anaemia, de fi ciencies of iron and vitamin A and their determinants in rural women and young children : a cross-sectional study in Kalalé district of northern Benin. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; He, G.; Qi, Y.; Yang, H.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Zou, K.; Lee, A.H.; Sun, X.; et al. Prevalencia de anemia y anemia por deficiencia de hierro en mujeres embarazadas chinas (IRON WOMEN): una encuesta transversal nacional. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shams, S.; Ahmad, Z.; Wadood, A. Prevalence of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnant Women of District Mardan, Pakistan. J. Pregnancy Child Heal. 2017, 04, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Rahman, R.; Idris, I.B.; Isa, Z.M.; Rahman, R.A.; Mahdy, Z.A. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Iron Deficiency Anemia Among Pregnant Women in Malaysia: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayasari, N.R.; Bai, C.; Hu, T.; Chao, J.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Huang, L.; Wang, F.; Tinkov, A.A.; Skalny, A. V; Chang, J. Associations of Food and Nutrient Intake with Serum Hepcidin and the Risk of Gestational Iron-Deficiency Anemia among Pregnant Women : A Population-Based Study. Nutrients 2021, 069, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salokhiddinovna, X.Y. Anemia of Chronic Diseases. Res. J. Trauma Disabil. Stud. 2023, 2, 364–372. [Google Scholar]

- Tibambuya, B.A.; Ganle, J.K. ; Ibrahim Anaemia at antenatal care initiation and associated factors among pregnant women in west Gonja district, Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deriba, B.S.; Bulto, G.A.; Bala, E.T. Nutritional-Related Predictors of Anemia among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care in Central Ethiopia: An Unmatched Case-Control Study. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years)Mean(±SD) | 25.38(±4.44) 18-24 |

76 | 45.0 |

| 25-35 | 85 | 50.3 | |

| >35 | 8 | 4.7 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 165 | 97.6 |

| Single | 4 | 2.4 | |

| Occupation | House wife | 86 | 50.9 |

| Employed | 43 | 25.4 | |

| Merchant | 31 | 18.3 | |

| Student | 9 | 5.3 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 31 | 18.3 |

| Muslim | 16 | 9.5 | |

| Protestant | 122 | 72.2 | |

| Educational Level | Unable to read and write | 6 | 3.6 |

| Primary education (1-8grade) | 35 | 20.7 | |

| Secondary education (9-12) | 53 | 31.4 | |

| College and above | 75 | 44.4 | |

| Family size | <5 | 147 | 87.0 |

| ≥5 | 22 | 13.0 |

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravidity (1.72(±0.45) | Primigravida | 44 | 26.0 |

| Multigravida | 125 | 74.0 | |

| Parity (1.99(±0.83) | Nullipara | 58 | 34.3 |

| Primipara | 54 | 32 | |

| Multipara | 57 | 33.7 | |

| History of Contraceptive use | Yes | 142 | 84.0 |

| No | 27 | 16.0 | |

| IFA supplementation | Yes | 144 | 85.2 |

| No | 25 | 14.8 | |

| History of Abortion | Yes | 30 | 17.8 |

| No | 139 | 82.2 | |

| Trimester at first ANC | 1st Trimester | 105 | 62.2 |

| 2nd trimester | 64 | 37.9 | |

| Gestational age | 1st Trimester | 11 | 6.5 |

| 2nd trimester | 58 | 34.3 | |

| 3rd trimester | 100 | 59.2 | |

| Birth interval | <2years | 26 | 15.4 |

| ≥2years | 96 | 56.8 | |

| Primigravida | 44 | 26.0 |

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malarial attack in the last 12 months |

Yes | 12 | 7.1 |

| No | 157 | 92.9 | |

| History of Chronic illnesses | Yes | 23 | 13.6 |

| No | 146 | 86.4 | |

| Deworming in the last 6 months | Yes | 47 | 27.8 |

| No | 122 | 72.2 | |

| HIV status | Positive | 2 | 1.2 |

| Negative | 161 | 95.3 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 3.6 | |

| Nutritional status | MUAC<23 | 33 | 19.5 |

| MUAC>=23 | 136 | 80.5 | |

| MDDS | Adequate | 95 | 56.2 |

| Inadequate | 74 | 43.8 | |

| Source of drinking water | Protected | 150 | 88.8 |

| Unprotected | 19 | 11.2 |

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Mean(±SD) | (25.38(±4.4) Mild Anemia(10-10.9g/dl) |

10 | 5.9 |

| Moderate Anemia(7-9.9g/dl) | 12 | 7.1 | |

| No Anemia | 147 | 87.0 | |

| MCV | Normocytic(80-100fl) | 152 | 89.9 |

| Microcytic (<80fl) | 17 | 10.06 | |

| MCHC | Normochromic(32-36g/dl) | 152 | 89.9 |

| Hypochromic(<32g/dl) | 17 | 10.06 | |

| MHCA | Microcytic & Hypochromic | 17 | 10.06 |

| NNCA | Normocytic & Normochromic | 5 | 3.0 |

| Variables | Category | IDA | COR(%CI) | AOR(%CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Family size | <5 | 10 | 137 | 1 | 1 | |

| ≥5 | 7 | 15 | 6.39 (1.27, 2.88) | 2.47 (0.47,12.93) | 0.28 | |

| Gravida | Primigravida | 5 | 42 | 1 | 1 | |

| Multigravida | 12 | 110 | 0.92 (0.63,13.062) | 1.08 (0.15,7.96) | 0.94 | |

| Parity | Nullipara | 5 | 53 | 1 | 1 | |

| Primipara | 5 | 51 | 1.04 (0.142, 2.745) | 1.19 (0.21,6.60) | 0.85 | |

| Multipara | 7 | 48 | 1.55 (0.62, 6.35) | 1.99 (0.62, 6.35) | 0.25 | |

| Birth interval | <2years | 7 | 19 | 3.46 (1.15, 13.65) | 0.84 (0.03,26.16) | 0.92 |

| ≥2years | 5 | 86 | 0.55 (0.11, 1.71) | 0.28 (0.01,8.71) | 0.47 | |

| Primigravida | 5 | 47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Trimester at 1st ANC started | First trimester | 5 | 100 | 1 | 1 | |

| Second trimester | 12 | 52 | 4.62(1.54, 13.81) | 4.94 (1.37,17.79) | 0.014* | |

| History of chronic illness | Yes | 12 | 41 | 6.49(2.16,19.58) | 4.62 (1.54,13.81) | 0.033* |

| No | 5 | 111 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Nutritional status | MUAC<23 | 11 | 22 | 10.83(1.53,12.04) | 3.84 (1.14,12.94) | 0.030* |

| MUAC≥23 | 6 | 130 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tea/Coffee consumption | 1-3(low users) | 6 | 96 | 1 | 1 | |

| >=4(heavy users) | 11 | 56 | 3.14(1.10,8.96) | 3.0 (0.66,13.71) | 0.16 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).