1. Introduction

The specific or small-scale research gap concerns whether the NBS [Nature-Based Solutions] [

2] traditional design approach could be replicated in another area. The study considers three pillars: Energy, Nature, and Built. Energy is represented by solar photovoltaics, Nature by blue and green, and Built by the cultural Heritage of traditional landscapes. Hundertwasser outlined the relevance of Tradition as a well-known quote: "If we do not honor our past, we lose our future. If we destroy our roots, we cannot grow," and maybe the "The Big Way"[

3] painting inspired the Holistic Visual Framework[

4].

The rural regions to be analysed are located in three distinct areas of Romania: Zerindu polder, Arad County, Romania [Z-AR], replicated in the nearby [T-BH] Tămaşda polder, Bihor County, Romania, both as agricultural plots; and a traditional family plot from Săcuţa locality, Boroaia, Suceava County, Romania [S-SV], one author's family heritage photos & stories as the research base, nowadays the ongoing natural almost wildening area.

The research offers a conceptual analysis of various technologies, including agrivoltaics with potential for green hydrogen production and fish-friendly micro-hydro hydropower, as complementary energy storage solutions.

On the humanistic side, the preservation of cultural landscapes and traditional farming knowledge is highlighted. The paper presents a comprehensive study on integrating indigenous and conventional agricultural practices with modern renewable energy systems. The study examines how cultural Heritage and local Knowledge can influence sustainable energy solutions, focusing on agrivoltaics and restoring the existing polder systems with nature-based solutions. The humanist side and the conceptual technical side are the relevant issues assumed in the research focus area.

The research question: Can a holistic framework methodology be used to enhance traditional design in small-scale solar solutions for agricultural landscapes? The gap that needs to be addressed is in research and utilising ancestral wisdom to develop culturally integrated technological solutions.

2. Holistic Framework - Methodology

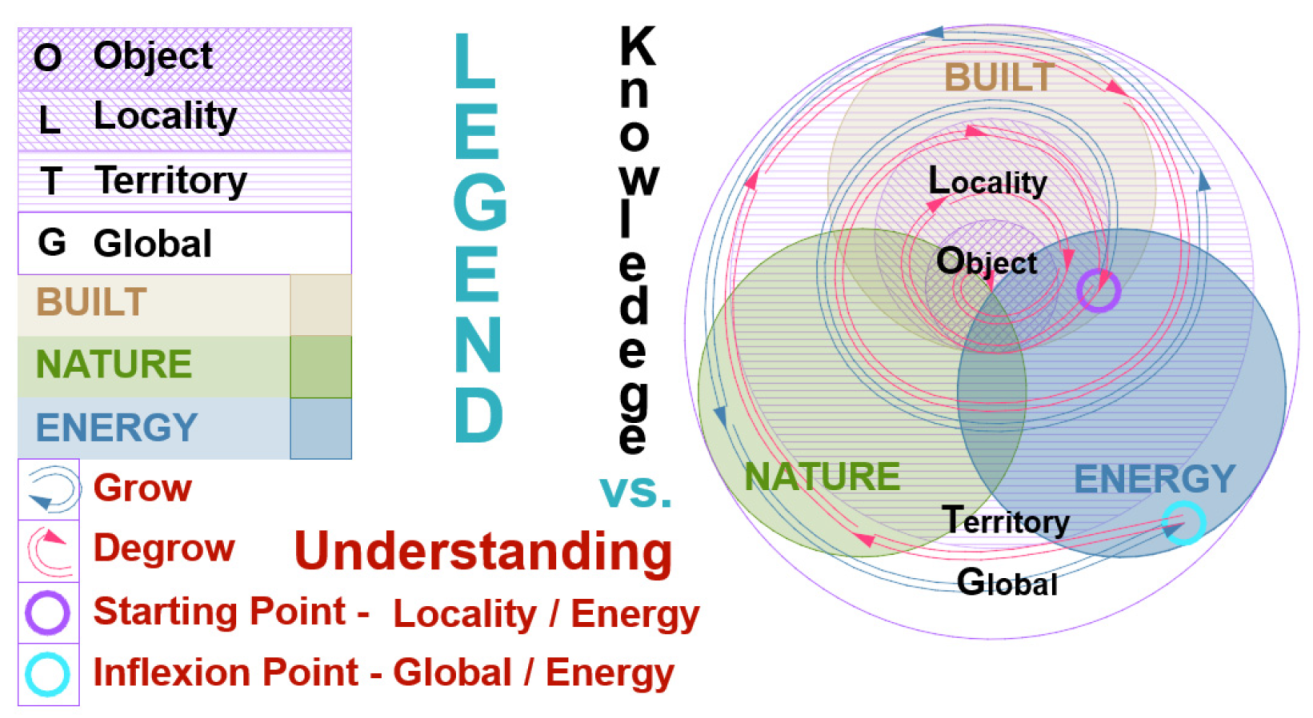

The paper begins by establishing the study's theoretical foundation, drawing on Bennett's Systematics and the concept of the Solar Regeneration Monad4. The research introduces three key dyads to guide their analysis: Technology vs. Tradition, Technical vs. Humanist, and Active vs. Passive. These dyads are presented not as contradictory forces but as complementary elements that must be understood and balanced for effective and sustainable development. The methodology section outlines the research approach to analysing these dyads across multiple scales, from individual agricultural plots to global contexts. They emphasise the importance of integrating traditional Knowledge and modern technical Understanding, using a spiral process to move from "Knowledge" to "Understanding" in each domain.

The chapter on the NATURE dyad explores the relationship between traditional and technological approaches in environmental management. The research focuses on biodiversity metrics, carbon sequestration potential, and integrating conventional and indigenous water management systems with modern agricultural technologies. A particular focus is placed on the role of wetlands and their preservation in the face of Anthropocene-driven changes. The BUILT dyad examines the intersection of humanistic and technical approaches in agricultural infrastructure and energy production. The research examines the assessment of cultural Heritage, traditional building practices, and the adaptation of rural structures to integrate renewable Energy. Case studies of traditional rural plots in [S-SV] Boroaia and Anthropocene agricultural plots in the [Z-AR] Zerind Polder and [T-BH] Tămaşda polder, Bihor County, also highlight how this balance can be achieved. The ENERGY dyad explores the relationship between passive and active energy systems, analysing carbon footprint, water footprint, and the potential for renewable energy generation.

The research presents detailed assessments of agrivoltaic systems, translucent photovoltaic coverings for irrigation canals, and the integration of fish-friendly micro-hydropower. Dyad proposed it related to a Monad after Bennett Systematics was introduced, specifically in the context of "Knowledge vs Understanding".

Dyads proposed related to a "Solar Regeneration" Monad are as follows:

"Technical vs Humanist" as BUILT Criteria;

"Technology vs. Tradition"asNATURE Criteria;

"Active vs. Passive" as ENERGY Criteria.

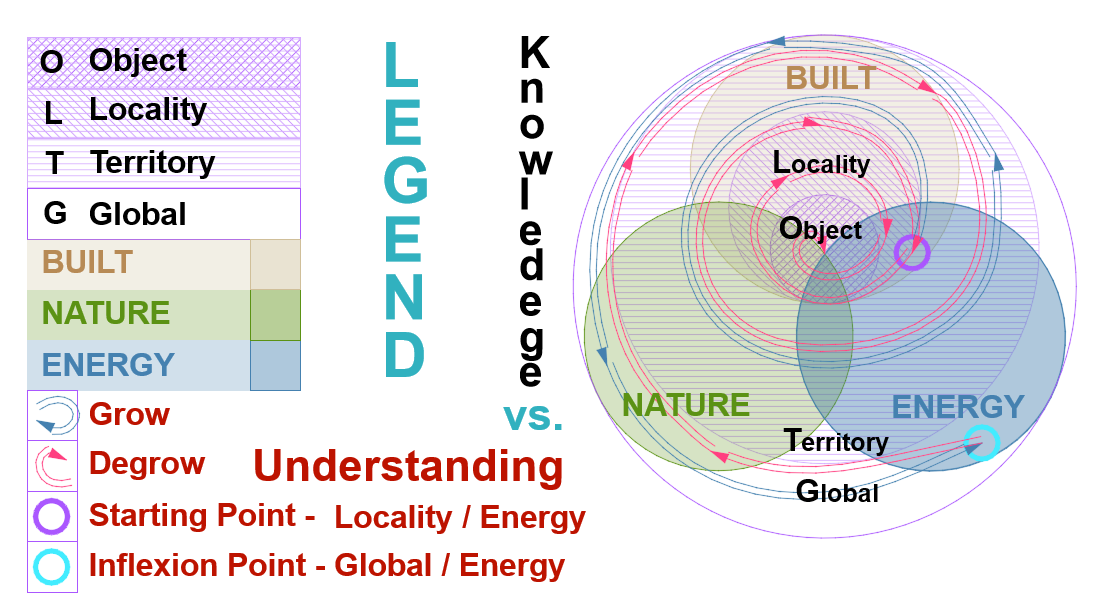

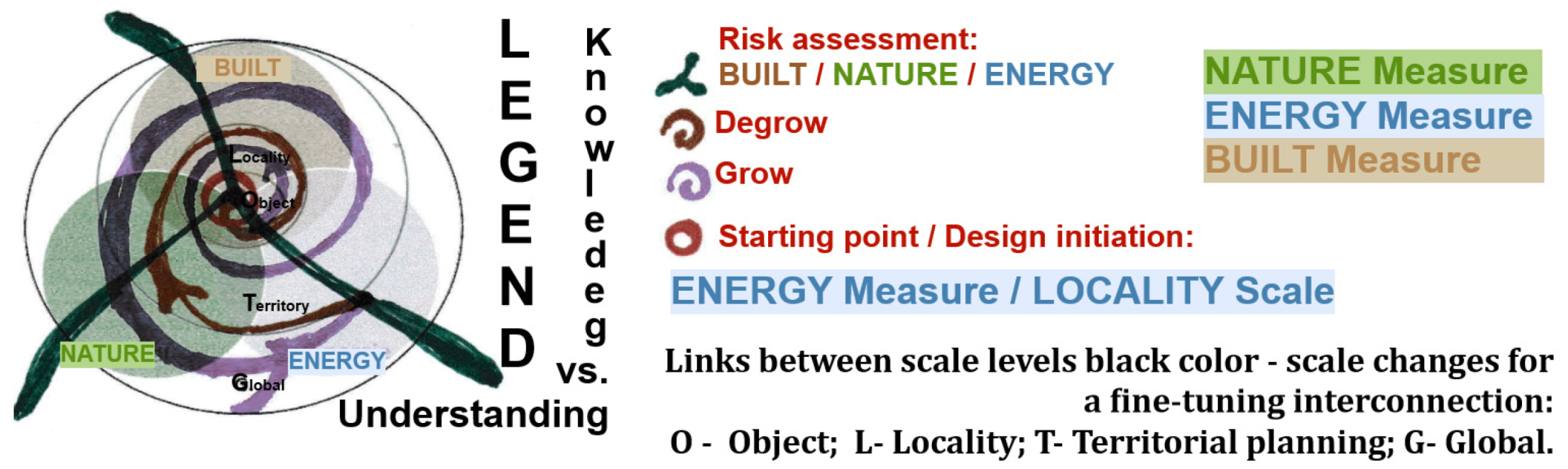

The theme relevant in the DYAD-related context is "vs/versus" or "Together despite opposites". "Knowledge" without "Understanding" is somewhat equivalent to "Technical" / "Technology" / "Active" without their opposites: "Humanist" /" Tradition"/"Passive", all opposites together without prioritisation. The Dyad needs the impulse to move in a Triad understanding process. The spiral is proposed as a process to achieve a Monad; the impulse required, in addition to the Dyad opposing terms, is the grow-degrow impulse. Translating the "Knowledge" criteria into "Understanding" requires a process. Bennett's systematics offers a set of regulations applicable to the abstract, an academic way of reaching "Understanding" - through the antithesis-thesis (Dyad) to the Hegelian dialectic (thesis, antithesis, synthesis), similar to the impulses of Bennett's Triad.

The Hegelian dialectic provides a framework for developing in a one-way spiral. But Bennett's Triads give a way of gaining and re-gaining through a double-way spiral covering the "Knowledge" necessary for achieving "Understanding" and making a multicriteria decision essential in any holistic solution. The spiral way sketches note the equal weight of the knowledge metaphors in the creation of the rosette: B—BUILT + N—NATURE + E—ENERGY on the scales from small to large, O—Object, L—Locality, T—Territory, G—Global, applied for projects on any starting points.

2.1. Methodology - Knowledge vs. Understanding Solar Regeneration-Related Dyads

Dyads - Knowledge vs Understanding as Technology vs Tradition / Technical vs Humanist / Active vs Passive. "Knowledge vs. Understanding" is the Dyad according to the views of Bennett, who detailed systematics to make the transition from "Knowledge" to "Understanding", which usually requires experimentation.

So the "vs/versus" inside the main Dyads means "opposite but together" and represents the research Gaps of the "Solar Regeneration" Monad we try to whole. We can develop a "3 Active vs Passive" Dyad related to the Energy transition from Energy Criteria or the same "2—Technology vs. Tradition" Dyad in the Ecological transition of Nature Criteria; a "1—Technical vs. Humanist" Dyad related to an Urban metabolism for the Built Criteria. KNOWLEDGE is defined through TECHNICAL criteria for NATURE - BUILT – ENERGY 4 and is somewhat partially related to ENVIRONMENT-SOCIAL-GOVERNANCE in many ways.

Figure 1.

Visual Holistic Framework - Methodology; Diagrams of Dyads related to the double-way spiral / Grow-Degrow Process.

Figure 1.

Visual Holistic Framework - Methodology; Diagrams of Dyads related to the double-way spiral / Grow-Degrow Process.

Figure

2 Visual Holistic Framework 4 - Methodology; Dyads related + growth-degrow process required as follows: Regenerative Monad Dyad, according to Bennett[

5] "—Knowledge" learned or transmitted requires a grow-degrow process for achieving "—Understanding" that typically involves experimentation. After the criteria related to Knowledge in

Table 1 are determined, three dyads:

1—Nowadays, Regenerative, the New Dyad "1—Tradition" needs to be perfected after many "1—Technology" implementations on different scales in a growth-degrow fine-tuning process.

2—Nowadays, Regenerative, the New Dyad "2—Humanist" needs more "2—Technical" accomplishments, which are often repeated in the same fine-tuning grow-degrow process.

3—Nowadays, Regenerative, the New Dyad "3—Passive" achievement is flawless through an optimal "3—Active" after a growth-degrow fine-tuning process.

Figure 2.

Visual Holistic Framework4 - Methodology; Diagram Dyad Knowledge vs. Understanding. Legend Scales: O Object; L Locality; T Territory; G Global / N Nature + B Built + E Energy; Grow – Degrow process from a Starting point, as Locality scale – polder.

Figure 2.

Visual Holistic Framework4 - Methodology; Diagram Dyad Knowledge vs. Understanding. Legend Scales: O Object; L Locality; T Territory; G Global / N Nature + B Built + E Energy; Grow – Degrow process from a Starting point, as Locality scale – polder.

Table 2.

[6] [DNSH] Do No Significant Harm principle.

Table 2.

[6] [DNSH] Do No Significant Harm principle.

| 1 |

Climate change mitigation |

Renewable energy production |

Substantial contribution |

| 2 |

Climate change adaptation |

Flood protection [NBS]2

|

Substantial contribution |

| 3 |

DNSH: The sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources |

Polder - wetland |

Substantial contribution |

| 4 |

DNSH The transition to a circular economy |

Recycled materials, preserved built works |

Substantial contribution |

| 5 |

DNSH Pollution prevention and control |

Attention needed for Materials |

DNSH |

| 6 |

DNSH The protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems |

Wildlife corridors with biocapacity/biodiversity - wetland impact |

Substantial contribution |

2.2. NATURE[7] — Regenerative Dyad "Tradition vs Technology"

The Dyad examines the relationship between traditional and technological approaches in natural contexts, with a focus on biodiversity, agriculture, and environmental management. The research analyses how conventional agricultural practices and modern technological solutions can be integrated to enhance biodiversity and ecological sustainability. The analysis is conducted across different scales, from individual plots to entire ecosystems. Specific attention is given to the role of wetlands, traditional water management systems, and their integration with modern agricultural technologies.

Table 3.

Nature 1—Nowadays, the New "1—Tradition" needs to be perfected after many "1—Technology" implementations on different scales in a growth-degrowth process.

Table 3.

Nature 1—Nowadays, the New "1—Tradition" needs to be perfected after many "1—Technology" implementations on different scales in a growth-degrowth process.

| Scale Global |

correct assessment |

| Green |

Increased biodiversity of local species measures (after invasive species issues) |

| Agriculture |

Following the Anthropocene-specific era of industrial agriculture, locally adapted cultures are emerging for regenerative agriculture. Pesticide-free European agriculture |

| Blue |

Water management - longitudinal connectivity & transversal connectivity related to wild corridors (after Anthropocene excessive Hydropower measures, excessive micro hydro number) |

| Biodiversity |

Wetland areas and longitudinal watercourse connectivity (following the Antropocene's decreased biodiversity) |

| Soil |

Soil health measures are necessary in the Anthropocene, particularly in addressing specific forms of soil degradation. |

| Risks related |

Water Scarcity / Risks relevant to energy production are to be evaluated. |

| Scale Object |

plot |

| Green |

Increasing biocapacity/ biodiversity, as well as the biophilic design of buildings [8] |

| Agriculture |

Pesticide-free crop rotation, Increasing Biodiversity |

| Blue |

Irrigation canals are needed/ ponds are required. |

| Biodiversity |

Increasing biodiversity measures, connectivity related to wild corridors |

| Soil |

Pesticide-free crop rotation |

| Risks related |

Water footprint/ Energy production to be evaluated |

| Scale Locality |

dam/polder |

| Green |

Increasing biocapacity/ biodiversity |

| Agriculture |

Pesticide-free crop rotation, Increasing Biodiversity |

| Blue |

Irrigation canals needed/ ponds&dams needed, longitudinal connectivity & transversal connectivity related to wild corridors. |

| Biodiversity |

Biodiversity improvement measures, such as meander renaturation, connectivity related to wild corridors |

| Soil |

Pesticide-free crop rotation in an agricultural community |

| Risks related |

Water footprint/ Energy production to be evaluated |

| Scale Territory |

Hydrological Basin |

| Green |

Increasing biocapacity/ biodiversity |

| Agriculture |

Pesticide-free crop rotation, Increasing Biodiversity |

| Blue |

Wetland areas, dams needed, longitudinal connectivity & transversal connectivity related to wild corridors |

| Biodiversity |

Increasing Biodiversity measures for local species, connectivity related to wild corridors |

| Soil |

Soil health improvement measures |

| Risks related |

Water Scarcity /Biodiversity issues/ Energy production to be evaluated |

The related paragraph includes a more detailed assessment of biodiversity metrics, carbon sequestration potential, and the impact of different land management approaches on natural systems.

2.3. BUILT[9] — Regenerative Dyad "Humanist vs Technical"

This Dyad analyses the intersection of humanistic and technical approaches in built environments. The research examines how cultural Heritage, traditional building practices, and modern technical solutions can be integrated into agricultural and Energy infrastructure. The analysis encompasses heritage value assessment and the preservation of cultural landscapes. Particular attention is paid to adapting traditional rural structures for modern energy production while maintaining their cultural significance.

Table 4.

BUILT 2—Nowadays, the New "2—Humanist" needs more "2—Technical" accomplishments, which are often repeated in the same grow-degrow process.

Table 4.

BUILT 2—Nowadays, the New "2—Humanist" needs more "2—Technical" accomplishments, which are often repeated in the same grow-degrow process.

| Scale Global |

correct assessment |

| Recyclable |

The existing built environment that supports PV systems |

| Heritage Value |

Revitalising the traditional household after vernacular heritage-specific degradation in the Anthropocene |

| Cultural Landscape |

Revitalising the cultural landscape after a possible Anthropocene-specific degradation |

| Social |

Traditional agricultural plots for energy communities and agrarian communities: circular metabolism[10] |

| Degrowth |

Revitalising an intangible heritage through measures specific to traditional culture encompasses daily life routines that follow the circadian cycle and agricultural activities that follow the lunar cycle. |

| Risks related |

Risks relevant to energy production are to be evaluated/Cultural Heritage. |

| Scale Object |

Plot |

| Recyclable |

Built environment rehabilitation - photovoltaic support |

| Heritage Value |

Cultural landscape preserved on traditional plots, particular heritage elements, as fences or others |

| Cultural Landscape |

Traditional landscape design |

| Social |

Social Impact of Agrarian/ Energy Communities |

| Degrowth |

Agrarian/Energy communities according to a traditional design |

| Risks related |

Risk of aggressive intervention in the cultural landscape/Cultural heritage |

| Scale Locality |

dam/polder related to flood risks in a rural/urban locality |

| Recyclable |

Circular metabolism on a large scale, as a metropolitan/ basin scale10

|

| Heritage Value |

Industrial dams – evaluated as industrial/technical heritage value |

| Cultural Landscape |

Cultural heritage preservation |

| Social |

Human-centred measures large-scale, infrastructure interventions with social impact, evaluated |

| Degrowth |

Degrowth and interconnectivity in large-scale infrastructure interventions |

| Risks related |

Energy production/biodiversity to be evaluated/Cultural Heritage |

| Scale Territory |

Metropolitan area, hydrological basin |

| Recyclable |

Heritage preservation as a circular economy measure |

| Heritage Value |

Heritage studies, thematic heritage visit route, basinal scale |

| Cultural Landscape |

Cultural landscape studies |

| Social |

Circular metabolism 10 / Energy / Agrarian communities |

| Degrowth |

Heritage preservation as a degrowth measure |

| Risks related |

Biodiversity issues / Energy production to be evaluated /Cultural Heritage |

The chapter thoroughly examines how indigenous and traditional property boundaries and land use patterns can be preserved while incorporating modern renewable energy systems. The measures are related to a dam/polder that protects against flood risk in both urban and rural areas, as well as the geographical and environmental factors that influenced the locality's development[

11]. The built Heritage also responded to the same factors through the impressive vernacular bioclimatic architecture and traditional landscape, which over time developed the specific cultural landscape. The influence of technologies on this cultural landscape is reasonably well controlled, as indicated by the „Risks related” line across all scales. And generates the answer in a returning way of the holistic spiral. So redefines the proper answer over and over until it is achieved in an optimal solution to all issues identified.

2.4. ENERGY[12,13]—Regenerative Dyad "Passive vs. Active"

The Dyad explores the relationship between passive and active energy systems in agricultural contexts.

Table 5.

ENERGY 3—Nowadays, the New "3—Passive" achievement is achieved through an optimal "3—Active" process after a growth-degrowth process.

Table 5.

ENERGY 3—Nowadays, the New "3—Passive" achievement is achieved through an optimal "3—Active" process after a growth-degrowth process.

| Scale Global |

correct assessment |

| Carbon footprint |

Carbon sequestration through nature-based solutions measures |

| Water footprint |

Related to hydrogen production and hydropower production |

| Renewable Energy |

Agrivoltaics, translucent solar panels or spaced bifacial panels on irrigation canals, micro-hydro, and fish-friendly |

| Energy Consumption |

Hydrogen production, Built environment consumption |

| Risks related |

Water / Energy / Built / Biodiversity risks related. |

| Scale Object |

plot |

| Carbon footprint |

Plot Carbon footprint / Carbon storage to be assessed |

| Water footprint |

Irrigation needed |

| Renewable Energy |

PV production to be assessed |

| Energy Consumption |

Irrigation pump consumption to be evaluated, Hydrogen consumption to be evaluated |

| Risks related |

Water / Biodiversity issues /Energy / Built risks related. |

| Scale Locality |

dam/polder |

| Carbon footprint |

Carbon footprint / Carbon storage to be assessed |

| Water footprint |

Hydrogen and hydropower production to be evaluated. Irrigation is needed for the biodiversity of the wetland. |

| Renewable Energy |

Hydrogen production/PV production to be assessed |

| Energy Consumption |

Irrigation pumps consumption/Consumption in Hydrogen production to be evaluated |

| Risks related |

Water / Biodiversity issues /Energy / Built risks related. |

| Scale Territory |

hydrological basin |

| Carbon footprint |

Carbon storage to be assessed |

| Water footprint |

Hydrogen and hydropower production, as well as other consumers, are to be evaluated. |

| Renewable Energy |

Production to be assessed/ potential production |

| Energy Consumption |

Consumers/potential consumers |

| Risks related |

Water / Biodiversity issues /Energy / Built risks related. |

The research analyses different energy generation and consumption approaches, examining carbon footprint, water footprint, renewable energy potential, and energy consumption patterns across various scales. The study includes a detailed assessment of how traditional passive energy systems can be integrated with active solar power generation[

14]. The analysis encompasses specific metrics for energy efficiency and environmental impact, including carbon sequestration potential and water use efficiency in various agricultural systems.

3. New BUILT [S-SV] vs. [Z-AR] [T-BH] Regenerative Dyad "Humanist vs. Technical"

The conventional wetland in Arad County was designed as a non-permanent water accumulation area. [Z-AR] [

15]

vs. [S-SV] Săcuța village, Boroaia, Suceava County, an area at the confluence of two watercourses with fluctuating flows, naturally creates a temporary wetland. The connection between the two sites seems coincidental, but it was related to an exodus in the Suceava area of over 150 families from a village in Banat, which occurred due to a plague epidemic in the 15th century. We can only assume that some of them or their know-how was transmitted by some C. family members, according to the words of some old Boroaia teacher and details that are not very specific in the village monograph.

The area of the village of Boroaia [S-SV] has relatively unproductive agricultural lands. For this reason, and due to the morphological environment, some risk management works related to the watercourse are considered risk management according to current norms. However, the hydrotechnical works in [S-SV] Boroaia, Suceava County, were determined by the eloquently named watercourse, Seaca/tr. Drought/Dry, which presents torrent-like flow fluctuations. Such techniques are not specific to the Moldova River basin's ethnological or morphological geographical area. They seem to have emerged by acquiring technical Knowledge from migrants from a traditional wetland area, such as Arad County. The migrants implemented secular agricultural practices, including water management systems, which were traditional in the distinct support areas with a Neolithic history. However, they could find this locally, having transferred know-how from the Arad area, specifically from or near the Zerind polder area. So, the other location to be analysed, Zerind Polder [Z-AR] 15, is a temporary dam area enclosed by dikes, demonstrating human adaptation to wetland conditions through traditional Anthropocene engineering. However, this can also be historically documented in the Banat area (Figure 4) as the implementation of landscape-specific techniques (ditches as crop boundaries, plots linked to dwellings/households delimited by arranged ditches). A network of rivers and streams characterises both sites, and the creation and management of water channels have shaped a cultural landscape with a specific set of traditional activities over time.

Traditional property boundaries mark the landscape, and agricultural plots reflect historical land use patterns through the design and management of indigenous ditches versus modern Anthropocene adaptations of flood risk management, such as the construction of dikes and polders. The Boroaia traditional rural plots and the Zerind Polder case studies offer a rich contrast, showcasing how traditional Knowledge can design modern sustainable practices.

The Boroaia (Figure 3) case examines historical land use patterns, water management systems, and indigene cultural practices conserved in a vernacular village, Săcuța. At the same time, the Zerind Polder [Z-AR]15 represents a more contemporary approach to agricultural production within the Anthropocene era.

3.1. Traditional Rural Plots [S-SV] vs [Z-AR] Anthropocene Agricultural Plots

This Dyad presents detailed case studies of two contrasting agricultural settings: traditional rural plots in Boroaia, Suceava County [S-SV] vs [Z-AR] Anthropocene agricultural plots of Zerindu Polder.

The research examines historical land use patterns, traditional water management systems, and cultural practices in Boroaia, dating back to ancient times. The Zerind Polder [Z-AR] examines contemporary agricultural practices, water management systems, and the potential for integrating renewable energy. The comparison highlights how traditional Knowledge can inform modern sustainable practices while addressing contemporary agrarian production and energy generation challenges. Romanian history significantly shaped the region's rural settlement patterns and agricultural traditions.

The uprising led to the widespread reorganisation of rural communities, establishing distinctive property boundaries and traditional farming plots that remain visible in today's cultural landscape. In its aftermath, many communities adopted specific agricultural practices and land management approaches, particularly in areas like Boroaia, where traditional plot layouts and water management systems reflect this historical influence.

The uprising's legacy is evident in the spatial organisation of rural settlements, the preservation of communal farming traditions, and the cultural emphasis on maintaining traditional agricultural Knowledge alongside technological advancement.

This historical event created enduring patterns in how local communities approach land use, water management, and the balance between traditional practices and modern development, making it particularly relevant to contemporary discussions about sustainable agricultural development and cultural preservation in Romanian rural areas. The ancestral agricultural and water management practices, developed over many years in Romania's rural wetlands, represent sophisticated environmental adaptations and sustainable resource management systems.

These practices evolved over generations through careful observation and the accumulation of wisdom. The agricultural system features carefully planned field patterns following natural topography, utilising terraced slopes and drainage channels. Farmers traditionally divide the land into small, irregular plots that work with rather than against the natural water flow patterns. This approach helps prevent soil erosion while maximising water retention in drier periods. Water management practices are particularly noteworthy in wetland regions, where communities developed intricate networks of channels, retention ponds, and natural filters. These systems demonstrate remarkable efficiency in managing seasonal flooding, directing excess water away from crops while retaining enough moisture for dry periods. Traditional Knowledge includes precise water release and retention timing based on seasonal patterns and crop needs.

The practices incorporate sophisticated crop rotation patterns that maintain soil fertility naturally, with specific combinations of plants chosen for their mutual benefits and adaptation to local conditions. Traditional field boundaries often feature specific vegetation for multiple purposes: marking property lines, providing windbreaks, and supporting local wildlife. These systems represent more than mere practical solutions - they form an integral part of the cultural Heritage, with specific traditions, customs, and ceremonies associated with different agricultural activities throughout the year.

Knowledge is traditionally passed down through generations, with each community maintaining its unique variations adapted to its specific microclimate and terrain. After historical maps, both sites are archaeological Heritage [S-SV] Secuta Cimec archaeological map Tumular necropolis, Daco-Roman period (3rd - 4th century) RAN 147081.01 LMI code SV-I-s-B-05398[

16]

vs [Z-AR] Zerindu/[T-BH] Tămaşda Cimec archaeological map, the Josephine Map, 1782-1785[

17].

3.2. BUILT [S-SV] Study Case Traditional Rural Plots – Boroaia, Suceava County, Romania Traditional Rural Plot - Historical Assessment [18,19]

The origin of the Boroaia village name is based on the "hypothesis of transfer from Transylvania". This hypothesis is also mentioned in the monograph on the locality, which considers it reasonably certain. The Banat area is remembered for the 150 families that left the village of Macea, Arad County, for Moldova, near Suceava, 19. Boroaia and Săcuţa are known to have been established around 1772-1774, but the documentation is unavailable.

Historical village monography reveals some dates: "Boroaia is also a prehistoric locality (...) and on the terrace of the Tîrziu stream, (...) Neolithic (Cucuteni phase A)"[

20], archaeological protected – near Boroaia village Tumular necropolis Daco-Roman period (3rd - 4th century) [

21].

"Hydrological data". The Săcuţa village[

22] / Secuţa map in Moldavia (1892-1898) is related to the Romanian Seaca River (meaning "dry, drained"), a temporary river that flows intermittently. On a smaller scale, a family plot area, "the names of some families (...) C. family name," appears, and teacher Nicolae Cercel[

23] remembered that this family’s origin is from the Banat area, in Transylvania[

24]. The plot for the first family member, named C., dated 1899[

25], bears the same name as that of other villages in the same county, such as SV3-Brosteni, a village with inhabitants of Transylvanian origin. The same origin of the relocated inhabitants was noted for Fundu Moldovei village, Mălini, where the ditches appear as plot limits, a particular measure for a wetland landscape, as seen in Păltinoasa, Stuplicani, Vatra Moldoviţei and Brodina de Sus[

26]. Banat is a known wetland that is scarce in warm periods. The family origin appears to have imported the know-how for managing a related confluence of rivers with wetland areas during rainy times of the year and scarcity in warm periods.

26

The period related to the Anthropocene was well focused on agricultural production, and these land works were significant in one year, with specific traditions and cultural immaterial Heritage. In the 2000s, the village's activities decreased due to relative abandonment. The reduced maintenance of land works affected the landscape and caused landslides near the watercourse. However, it also expanded vegetation to a degree of wildness that transformed wetlands into protected areas, a desirable post-Anthropocene regenerative design[

27]. This evolution is also documented on GIS maps.

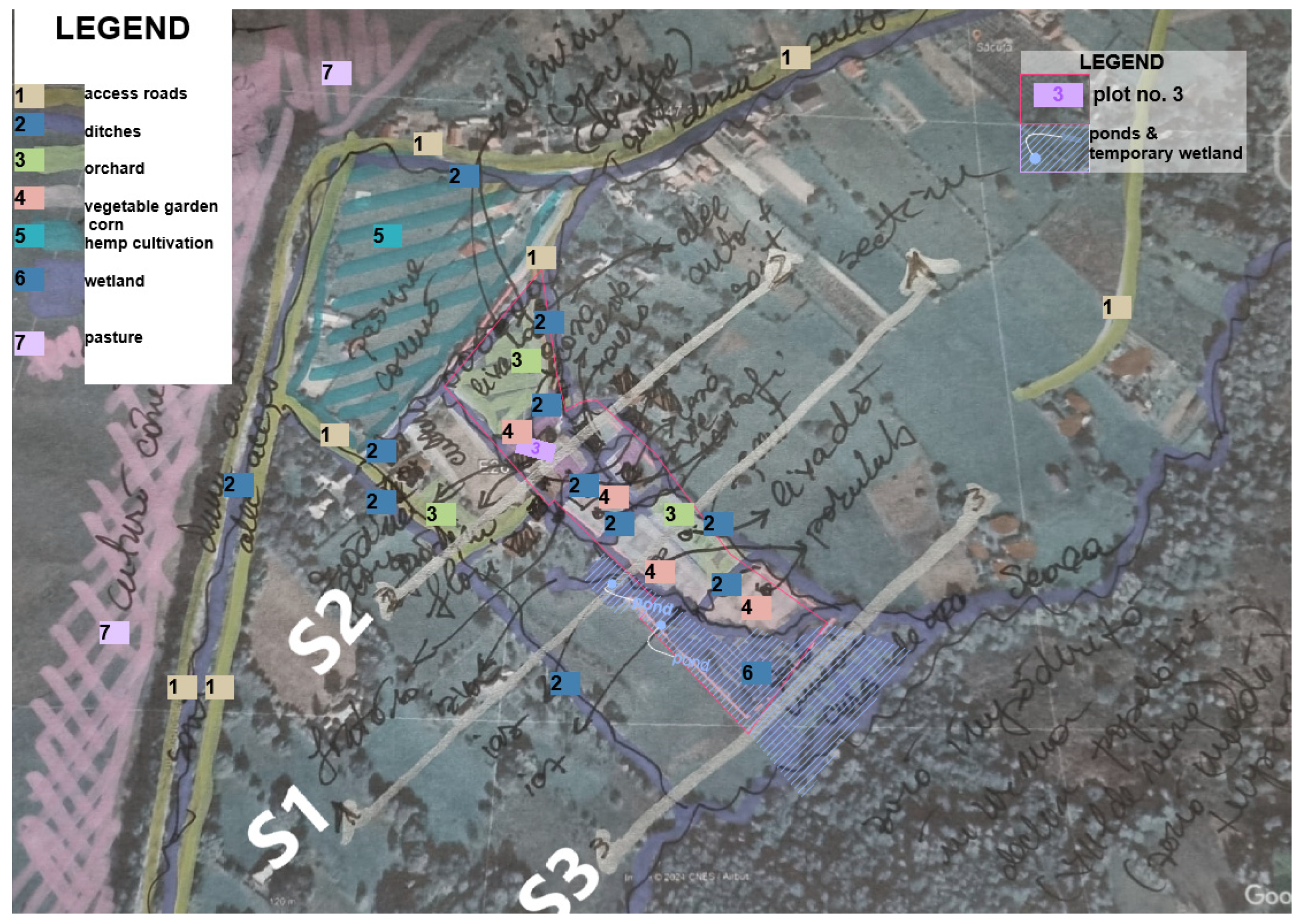

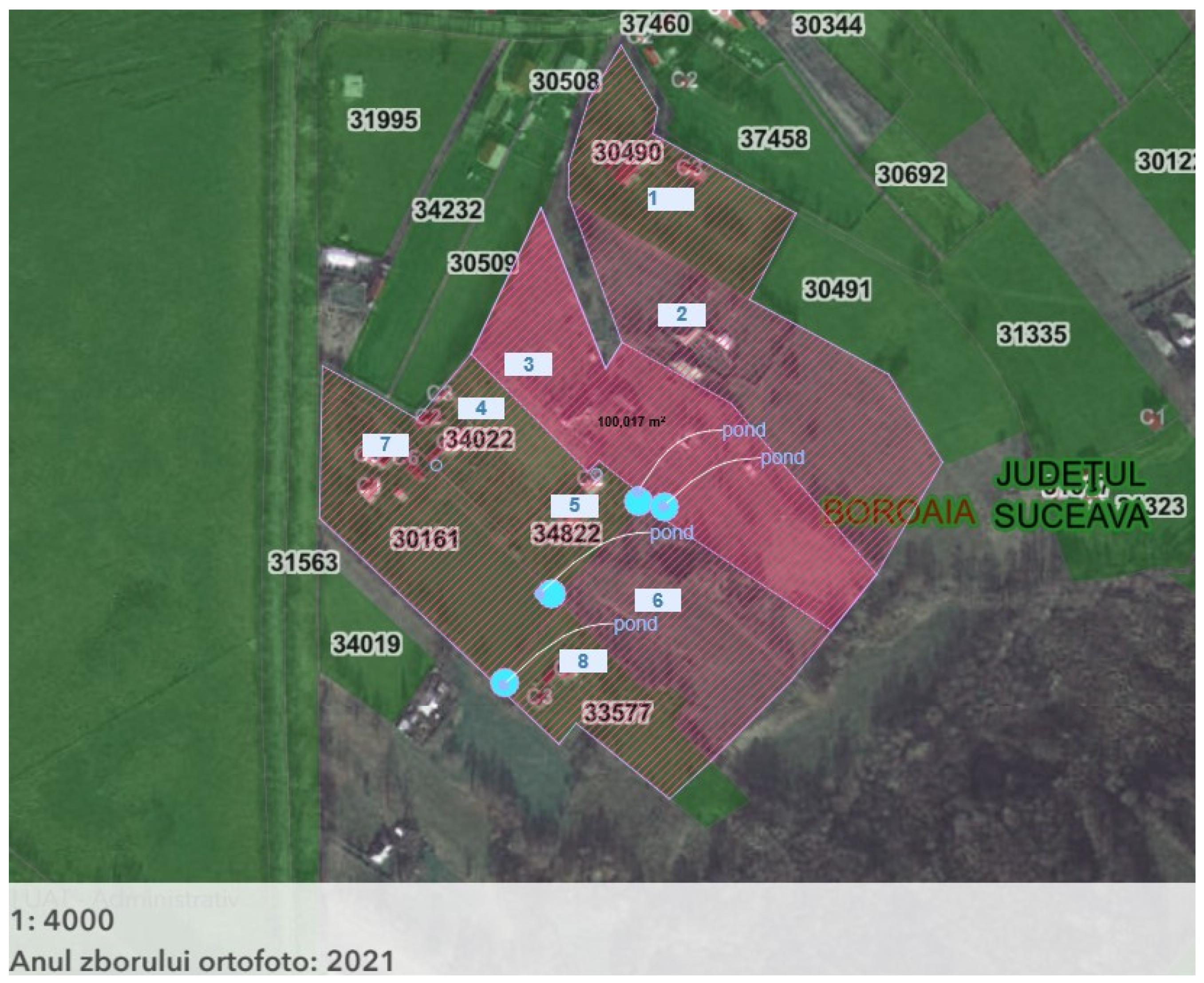

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 are displayed on the cadastral support image ancpi/geoportal map [S-SV], with areas related to the extended family marked with numbers. Ponds are also marked to define a blue-green corridor visible on the anterior map plans, with decreased or increased green spaces related to the year affiliated, as shown on GIS maps from 2005 to 2024. Sentinele 2 land cover [

28,

29] year 2017

vs. 2024 compared, land cover evolution for plot 3, No marked in the context of changed land use. If the two Sentinel 2 maps reveal a decrease in the green area for the entire Săcuţa locality, the blue-green corridor can be noticed as increasing. The edited maps in

Figure 3 indicate the ongoing natural widening area related to the [S-SV] study case.

Figures: Figure 5 [S-SV] Planimetric sketch; Figure 6.1 [S-SV] photos of the pond and watercourse wetland area; Figure 6.2 [S-SV] other sketches of the No. 3 plot, Ilie C.'s plot, traditional landscaping (sketched plan, land sections). Every part of Plot No. 3 was landscaped in a family-oriented, almost urbanistic design environment, featuring a house with a front flower garden, a yard, a vegetable garden, a beehive yard, a cornfield, and a pasture, all delimited by numerous ditches and a natural wetland with a pond area. The pond continues to be set until the watercourse, with the natural wetland for most of the year, is bounded by the Seaca watercourse.

Figure 5.

[S-SV] planimetric Dițoiu, N.C.'s sketch, edited map source30.

Figure 5.

[S-SV] planimetric Dițoiu, N.C.'s sketch, edited map source30.

Figure 6.1.

[S-SV] Dițoiu, N.C.'s family, personal dated photos.

Figure 6.1.

[S-SV] Dițoiu, N.C.'s family, personal dated photos.

Figure 6.2.

[S-SV] Dițoiu, N.C.' Sections sketch, with the ponds and ditches marked as particular measures in a wetland landscape.

Figure 6.2.

[S-SV] Dițoiu, N.C.' Sections sketch, with the ponds and ditches marked as particular measures in a wetland landscape.

3.3. BUILT [Z-AR] 15 Study Case Anthropocene Agricole Plots - Zerind Polder, Arad County, Romania

The TRIAD for small-scale regeneration proposes re-naturalisation for NATURE, rehabilitation for BUILT, and solar energy production for ENERGY in the particular Romanian polder. NATURE - As wetlands by restoring the courses of the old meanders and replacing the inner dykes space in the polders as with canals, wetland landscape works.

Depending on how the population assimilates the new measures, smaller channels along the property boundaries are proposed to delimit areas with the same agricultural culture. Changing the culture will develop communities within the polders for ecological agriculture, which avoids the use of pesticides by replacing them with temporary land flooding. Some agricultural plots will be agrivoltaics areas to achieve a proper particular for some specific cultures and renewable energy production.

[Z-AR]: The Sentinel 2 land cover map for 2024 is very similar to the Sentinel 2 land cover map since 2017. For wetland areas and Copernicus Sentinel 2 data available and cold meanders that still need to be considered for renaturation, can have an impact on biodiversity and biocapacity as wetland, a NATURE related criteria. The ENERGY areas (

Figure 7) for agriculture are marked by canals on property boundaries, which provide access to water during dry periods (Irrigation) and minimal protection against crop flooding during rainy periods, as indicated by plot boundaries in the traditional wetland area landscape. There are also well-known NBS

2 [Nature Based Solutions] that address various challenges, from food security to natural disaster risks. Among the benefits of wetlands, we can mention the increase in biodiversity, the expansion of carbon storage, the restoration of water reserves, protection against floods and drought, and the ecological agriculture seen in these polders. Polder's area dates back to the 20th century, and we have already admitted that the traditional family plot landscape with dikes is also part of the cultural Heritage of Banat wetland areas

19.

4. New NATURE [Z-AR] Regenerative Dyad "Tradition vs. Technology"

Table 6, on Biodiversity and Carbon Sequestration, is essential for a technical evaluation of different land covers. We can observe that the Wetlands area, on a per-hectare basis, has the best carbon sequestration per year, overall vegetation, and soil. Suppose the Forest is better at vegetation Sequestration, with a value of 120 tonnes of Carbon per year. In that case, soil sequestration puts the wetlands in the first and best option, with a significant difference: overall 686 tonnes per year compared to the overall 243 tonnes for temperate Forests.

Table 6.

Biodiversity & Carbon Sequestration[

31].

Table 6.

Biodiversity & Carbon Sequestration[

31].

Carbon Sequestration

(Tons of Carbon per year) |

Boreal Forest |

Temperate Forest |

Temperate Grassland |

Tropical Forest |

Desert land semi-desert |

Tundra |

Wetland |

Tropical Savana |

Croplands |

| Surface (ha) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Vegetation Carbon Sequestration |

64 |

120 |

7 |

120 |

2 |

6 |

43 |

29 |

2 |

| Soil Carbon Sequestration |

344 |

123 |

236 |

123 |

42 |

127 |

643 |

117 |

80 |

| Overall Carbon Sequestration |

408 |

243 |

243 |

243 |

44 |

133 |

686 |

146 |

82 |

Carbon Sequestration is needed and incorporates biodiversity into a budgeted plan before biodiversity credits are legislated. As measured by biodiversity metrics, in cases where biodiversity credits are not available, assume carbon credits are utilised. The "Biodiversity metrics" [

32] instrument appears to be more accurate than the "G-res tool" [

33] metric dedicated to dams and polders. The "Biodiversity metrics" reveals measures and measurements for land covers areas as Cropland, Grassland, Heathland and shrub / Tundra, Intertidal, Hard Structures, Intertidal sediment (relevant in water course landscape design as longitudinal continuity), Lakes, Sparsely vegetated land, Urban, Woodland and Forest, Coastal Saltmarsh and Rivers; similar "G-res tool metric" related to google Earth engine measurements for land covers as Cropland, Grassland/Shrubland, Bare area, Permanent snow/Ice (not appearing in the first metric, but asimilated), Waterbodies, Settlements, Forest, Drained Peatlands and Wetland. The Gres-tool is more accurate on specific blue-green design issues. It is similar to those available in the United Kingdom, but with a lower level of accuracy. There appears to be a gap in implementing local biodiversity tools and biodiversity credits. A holistic and accurate tool to score biodiversity value [

34] would be helpful in the preliminary design stage.

Figure 7 presents the Zerindu site plan [Z-AR], which includes the support drawing plan with site-protected areas, such as the Crișul Negru river, and the pink line representing the polder dikes' boundaries. The measures for the three dyads, NATURE-ENERGY-BUILT, were noted as colour codes (green, blue, pink) for increased visual visibility.

Figure

7 presents the concept for the polder, incorporating all relevant works proposed in a regenerative design – NATURE with Biodiversity works. ENERGY measures also noted (

Table 7): 1. Watercourse's longitudinal connectivity with minimal interventions like fish-friendly micro hydropower; 2. polder boundary preservation of built dykes - internal polder contour channel; 3. old meander renaturation; 4. The old internal polder dike was abolished and redesigned as a canal with a wetland landscape area 5. Agricultural landscape inner polder with dykes on property boundaries - specific New / ReBuild as "cultural" boundaries also as irrigation canals (Green Concrete material irrigation canals covered by translucent photovoltaic panels Energy Production & Energy Consumption through pumped water irrigation); 6. agrivoltaic properties with trees and specific culture need solar shading- Solar PV Energy

Production; 7. Fish-friendly micro hydropower as Solar PV Energy

Storage & Energy

Production/ Green Hydrogen Production - PV Energy

Consumption.

Figure 7.

ENERGY & NATURE & BUILT[

35].

Figure 7.

ENERGY & NATURE & BUILT[

35].

5. New ENERGY [Z-AR] Regenerative Dyad "Passive vs Active"

Table 7 presents the proposal with Energy measures related to the "Passive vs. Active" Dyad.

5.1. Agrivoltaics Production

Agrivoltaics is a land use practice that warrants further study.

As shown in Table

5 for the ENERGY dyad "Passive

vs Active," renewable energy options include agrivoltaics, translucent solar panels on irrigation canals, micro-hydro systems designed to be fish-friendly, and the potential for smaller-scale green hydrogen production. The relevant energy consumers include agriculture-specific installations, irrigation pumps, and facilities for producing green hydrogen. A Moroccan research study[

38] proposes a solar-powered single-stage distillation system for treating domestic wastewater.

Additionally, polders, which typically help prevent flooding in rural villages, could also be utilised to supply wastewater as a feedwater source. Solar power generation can be further enhanced by creating rural energy communities that use local energy resources, such as Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) or agrivoltaics within polders.

The approach to cultivating different crops on the same land supports nature-related measures, including biodiversity conservation and sustainable farming practices [

39]. Agrivoltaic panels are generally oriented in an east-west direction, rather than south-facing. Without energy storage implemented in a polder that uses east-west-oriented agrivoltaic panels, vertical photovoltaic (PV) systems, including bifacial solar panels, can achieve capacity factors comparable to those of traditional ground-mounted solar farms, despite their orientation.

While colocating solar energy production with farming might decrease yields in certain areas, studies have indicated that it can increase yields for specific types of plants, depending on the location and weather conditions. Research has shown that some crops are more sensitive to shading than others. Land-use efficiency[

40] is assessed by comparing the total solar electricity generation with that of a traditional ground-mounted solar farm, as well as comparing the crop yield with that of an unshaded reference.

5.2. Photovoltaic Covering Irrigation Canals

Originally developed to address water loss by reducing evaporation in agricultural regions, the panels covering irrigation canals evolved into canal-covering technologies in the late Anthropocene.

The technology is adapted for areas with extensive irrigation networks, mainly where traditional water management systems require modernisation without complete reconstruction, and for aquatic biodiversity. Translucent photovoltaics were chosen, or simply spaced bifacial panels, for Agricultural communities, such as those in polders, which are becoming both energy and agricultural communities. This can also introduce unique, adapted design modalities that better fit local farming practices and/or traditional irrigation patterns.

Semi-transparent photovoltaic panels or spaced bifacial panels, designed for covering irrigation canals, are recommended in arid areas, as noted in [Z-AR], but are not necessarily recommended for covering meanders that have been re-naturalised to increase biodiversity. Implementing translucent solar panels is transforming water management in agriculture while generating green Energy. These panels reduce water evaporation from covered canals, thereby conserving water in agricultural regions that are vulnerable to severe drought. Reduced evaporation and algae growth in the covered canals have improved water quality. The electricity generated supports the local farming community, which becomes an energy community while maintaining traditional farming practices that a family can implement on a specific rural plot within an indigenous traditional landscape design.

At the same time, as can be seen in Figure 9, a replicability study in [T-BH] Tămaşda polder, Bihor county, reveals that the NATURE area for biodiversity is not similar to the ENERGY area, where this type of covered irrigation channel is observed.

5.3. Solar Storage Potential

Solar storage could include green hydrogen production and fish-friendly micro hydropower, but a more detailed technical design is needed to be implemented in a future design proposal. The Dyad related to ENERGY may examine various approaches to solar energy storage in agricultural settings, as in Figure 9. A fish-friendly micro-hydro power plant associated with a lateral dam or water reserve area near the watercourse could be considered for one of the two discussed polders. However, this research stage analyses the possible and desirable aspects without detailing technical solutions, focusing solely on the potential for green hydrogen production and the potential of fish-friendly micro-hydropower systems. The study includes a comprehensive list, along with technical specifications. It analyses the potential, rather than the feasibility, of green hydrogen production for implementing fish-friendly micro-hydropower systems without detailing technical solutions or specifications for different storage methods. Figure 8 is a concept sketch of the case study [Z-AR] Zerindu polder, Arad county, and the related replicability case study – [T-BH} Tămaşda polder, Bihor county, with measures noted, both on the Crişul Negru river.

Figure 8.

[Z-AR] [T-BH] Dițoiu, N.C.'s sketch[

41], replicability case study; [T-BH] Tămaşda polder, Bihor county & [Z-AR] Zerind polder, Arad county. Planimetric sketch, Polders Zerind & Tămaşda, with solving related to the legend: 1. watercourse;.2. polder boundary dike with inner polder contour channel; 3. old rehabilitated canal; 4. old pier inside the polder dismantled and arranged as a canal/wetland; 5. Inland agricultural land for polders; 6. Biodiversity /water level digitalisation.

Figure 8.

[Z-AR] [T-BH] Dițoiu, N.C.'s sketch[

41], replicability case study; [T-BH] Tămaşda polder, Bihor county & [Z-AR] Zerind polder, Arad county. Planimetric sketch, Polders Zerind & Tămaşda, with solving related to the legend: 1. watercourse;.2. polder boundary dike with inner polder contour channel; 3. old rehabilitated canal; 4. old pier inside the polder dismantled and arranged as a canal/wetland; 5. Inland agricultural land for polders; 6. Biodiversity /water level digitalisation.

Figure 9.

Replicability study case - [T-BH] Tămaşda polder, Bihor county, and study case – [Z-AR] [T-BH] 15 Zerindu polder, Arad county, with the same proposed measures.

Figure 9.

Replicability study case - [T-BH] Tămaşda polder, Bihor county, and study case – [Z-AR] [T-BH] 15 Zerindu polder, Arad county, with the same proposed measures.

ENERGY AREA: APV plots, fish-friendly micro-hydropower, and existing irrigation canal—semi-transparent photovoltaic covering;

NATURE AREA: Renaturation for meanders with wetland/pond areas. The old internal polder dike was removed to transform the canal into a wetland area.

6. Discussions

The primary practical findings on integrating traditional agricultural approaches with modern renewable energy systems primarily focus on the case studies of the traditional residential plot [S-SV] Boroaia, Suceava county, and the related agrarian plots in Polderul Zerindu Mic, Arad county [Z-AR], with replicability in [T-BH] Tămaşda, the polder in Bihor county.

The final similar SWOT (

Table 8) analysis of the humanistic side highlights strengths, including the preservation of cultural landscapes and traditional agricultural Knowledge, while weaknesses include potential resistance to change from local communities. Opportunities highlighted in the SWOT analysis include the potential for extending these approaches to other regions and the possibility of developing new technological solutions that better integrate with traditional practices. Threats are examined from both technical and humanistic perspectives (such as the impact of climate change and the loss of indigenous Knowledge).

David Seamon's Place Monad[

64], accepted in the Place Petal of the Living Building Challenge regenerative system, was inspiring as a Bennettțs methodology. Another assumed date-in is the European taxonomy with DNSH (

Table 2) principles applied to energy, water, and recyclable materials, as well as Mitigation (water floods) and Adaptation (renewable Energy) environmental criteria.

The fundamental relationships explored in the Dyads related to the double-way Spiral methodology are Technology vs Tradition (Nature), Technical vs Humanistic (Built), and Active vs. Passive (Energy). Each Dyad can effectively combine traditional Knowledge and modern technological solutions to create sustainable and culturally appropriate systems. A similar SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis assesses the technical and humanistic aspects of the studied systems. The technical strengths identified include successfully integrating agrivoltaic systems with traditional agricultural practices and efficient water management through modernised older systems. The technical weaknesses focus on the higher initial costs and the complexity of implementing hybrid systems.

The research highlights the importance of traditionally inspired design, which assumes replicability and local acceptance, supported by ethnographic evidence from historical studies, as seen in the BUILT. Underscoring the need to balance technical and humanistic approaches, as well as the importance of ENERGY & NATURE principles, following DNSH. The research aims to demonstrate the replicability of the holistic framework in related design-built projects, such as the Double-ways Spiral design framework, as well as the replicability of the solar energetic community [Z-AR] [T-BH] polders researched areas, and relevant to specifically the Romanian Agricultural wetlands. Any dam protects against flood risk in both urban and rural localities. And also significant defines a geographical environment where the same locality developed. To research the most significant Anthropocene settlements, urban localities, one must understand the history and environment that generated them. To transform an Anthropocene settlement with regenerative measures, you need to scale up and down in a grow-degrow spiral all the measures until you reach the optimal, non-invasive measure for both humans and Nature.

7. Conclusion

The research question about the visual holistic framework methodology used to enhance traditional design was targeted. The gap that needed to be addressed regarding culturally integrated technological solutions was touched on in various ways, in a conceptual technical view; more detailed, technical elements will be addressed as the next step.

The spiral concept is a framework model that provides a holistic approach to managing multiple distinct criteria in a more creative, two-way, visual spiral, serving as a methodology essential to and associated with design work. The framework can be integrated into the concept phase of any built design project, on any design scale, from "Object" building to" Territory"[

65]

, such as a watercourse landscape or a church restoration

60.

The future gaps that need to be closed are the implementation of solar regenerative Monad with their dyads in detailed, distinct built environments, the expansion of Built—new BIPV focus to Built—Heritage on a larger scale, or the integration of BUILT—new BIPV in a new energetic community, and the development of NATURE - Blue-Green watercourse works.

The primary research weakness is the lack of technical studies, which represent only a conceptual framework for a preliminary design that can be assumed in the subsequent stage of a more detailed technical project. The following is to be researched: the Solar Regeneration Monad is related to the visual holistic framework for new study cases and also associated with the detailed study cases, specifically the ENERGY dyad — agrivoltaics or Micro-Hydropower supported with technical studies, at the detailed technical stage; but also the BUILT dyad - related to Urban development and NATURE dyad - maybe with the most reserch needed in Biodiversity or associated with a biophilic urban regeneration, mantaining life well-being both for wildlife and humans. The Solar Regeneration Monad with " ENERGY– BUILT – NATURE " measures is a holistic visual framework replicable to any built environment for a "Built" Regenerative Culture that enables the identification of almost the best solution for the conservation of cultural heritage values in an "Energy" transition context with "Nature", biodiversity, or other water-related issues, as risks to be managed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, original draft preparation, visualisation, investigation, N.-C.D.; review and supervision, A.A.; review and supervision, Energy, Agrivoltaics production paragraph R.S.T.; [Z-AR] [T-BH] case studies, Aqua Prociv Proiect design team coordination D.S.S.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The case studies related to this research, the Renaturation of [Z-AR] Zerind Polder, Arad County, and the replicable case study of [T-BH] Tămaşda Polder, Bihor County, were conducted by the Aqua Prociv Proiect Company, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, and underscore the significant relevance of the Aqua Prociv Proiect team's specific research on design 15.

Acronyms

[DNSH] Do No Significant Harm; [NBS] Nature-Based Solutions; [N] Nature; [E] Energy; [B] Built; [O] Object; [L] Locality; [T] Territory; [G] Global; [S-SV] Săcuţa locality, Boroaia, Suceava county, Romania; lat. 47o31’ N, long. 26o28’ E, +423m –residential plots, traditional landscape, ongoing natural wildening area; [Z-AR] Zerindu Mic polder, Arad County, Romania; lat. 46o63’ N, long. 21°56’ E, +91m – The anthropocentric landscape also proposes regenerative measures in the current research; [T-BH] Tămaşda Polder, Bihor County, Romania; lat. 46o65’ N, long. 21°63’ E, +92m - Currently, an anthropocentric landscape, this study serves as a replicability case in the research.

References

- John, G. Bennett, Elementary systematics: A Tool for Understanding Wholes (Bennett Books, the Estate of J.G. Bennett, United States of America, 1993), 27.

- Carla S. S. Ferreira, Milica Kašanin-Grubin, Marijana Kapović Solomun, Svetlana Sushkova, Tatiana Minkina, Wenwu Zhao and Zahra Kalantari, Wetlands as nature-based solutions for water management in different environments (Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health: Volume 33, June 2023, 100476), 6. "Wetlands have emerged as NBS in various water resources management practices, including regulating the hydrological cycle and improving water quality. However, natural wetlands worldwide continue to be threatened by anthropogenic and climate drivers" https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coesh.2023.100476 (accesed: April 2025).

- Caro Weisauer, 100 Questions about Hundertwasser (100 X Hundertwasser. Artist-Visionary-Nonconformist, METROVERLAG: 2016, ISBN 978-3-99300-261-9), 31, 35. "Hundertwasser was convinced that the creation of the earth took place in spiral form”. https://www.kunsthauswien.com/en/education/100-x-hundertwasser/ (accessed: April 2025).

- Nina Cristina Dițoiu, Ph. D. Thesis – Summary "The regenerative culture of the built environment: Multicriteria decisions in the double-way spiral",2023 https://doctorat.utcluj.ro/theses/view/OZxZ2SPxgn5edlY60K2Gi3FKCdAH5uP4XDqNfXmH.pdf (accessed: April 2025).

- John, G. Bennett, Elementary systematics: A Tool for Understanding Wholes (Bennett Books, the Estate of J.G. Bennett, United States of America, 1993), 8-17.

- https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/home (accessed: April 2025).

- https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/home Related to 4 taxonomy criteria: DNSH The protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems; DNSH Climate change mitigation; DNSH Climate change adaptation; DNSH The sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources (accessed: April 2025).

- Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., with Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, Angel, S. A pattern language - Towns, Buildings, Constructions, Oxford University Press, New York), 812-814, 764-7681977, “175- green house”, “163- outdoor room”.

- https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/home Related to 3 taxonomy criteria: DNSH Climate change mitigation; DNSH Climate change adaptation; DNSH The transition to a circular economy (accessed: April 2025).

- Aristide Athanassiadis, https://www.circularmetabolism.com/ (accessed: April 2025).

- Dabija, Ana- Maria, Building with the Sun. Passive Solar Daylighting Systems in Architecture (printer Internationaș Publishing Switzerland, I Visa (ed), Nearly Zero Energy Communities, Springer Productionin Energy, 2017) ”One conclusion that can be drawn (...) is that if we pay attention to the past, we may find solutions for the present. In other words, what we invent today may very well have been invented and forgot centuries ago. It is true for many other architectural technologies, it is true for the solar architecture as well. Passive solar design implies the attentive observation and understanding of Nature and nature rules that lead to a philosophy of building with Nature and not against- or in spite of- it.” https://www.researchgate.net/ (accessed: 2018).

- https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/home Related essential to one taxonomy criteria: DNSH Climate change mitigation (accessed: April 2025).

- Peter Droege, ed., URBAN ENERGY TRANSITION Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2018), 31-49, 85-113.

- Krippnner, Roland– ed., Gerd Becker, Ralf Haselhuhn, Claudia Hemmerle, Beat Kampfen, Roland Krippner, Tilmann E. Kuhn, Christoph Maurer, Georg W. Reinberg, Thomas Seltmann, Building-Integrated Solar technology-Architectural design with Photovoltaics and Solar Thermal Energy (Detail Green Books, Munch, Germany, 2017), 64.

- Aqua Prociv Proiect, Company, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, "Renaturation of Zerind & Tămaşda polders, Arad and Bihor counties” (Romania Team Project: Concept Sketch & cad drawing landscape design - Arch. Nina Cristina Dițoiu; Cad Drawings & Hidrotechnical Design - Eng. Dragoş Gros, Team Coordinator Eng. Dan Săcui).

- ran.cimec.ro cimec map Tumular necropolis Daco-Roman period (3rd - 4th century) RAN 147081.01 LMI code (List of Historical Monuments) List of Historical Monuments from 2010, SV-I-s-B-05398 (accessed: April 2025).

- ran.cimec.ro cimec map (accessed: April 2025).

- Gheorghe Scripcaru, BOROAIA O reintoarcere in spirit (Monografie reeditată comuna Boroaia ISBN 973-98476-5-X, 2013), 87-88, 90. [tr.n.]“Names of some families (...) C.” Boroaia “hypothesis of transfer from Transylvania”, “Transylvanian words among the village inhabitants (dar-ar, lual-ar, mancai-ar, basna, ciubar, flacau (...) pisti, tongue, house, amu, etc.)” (...) “from a certain Bora and Boroaia’s wife, with whom the peasants emigrated from Transylvania”.

- Ion Ghinoiu, (coordonator general), Habitatul. Răspunsuri la chestionarele Atlasului Etnografic Român (Volumul IV Moldova, ISBN 978-973-8920-23-1 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2017).

- Gheorghe Scripcaru, BOROAIA O reintoarcere in spirit (Monografie reeditată comuna Boroaia ISBN 973-98476-5-X, 2013), 25. [tr.n.] "in Drăguşeni, the archaeological excavations of V. Ciurea discovered (...) concludes that Boroaia is also a prehistoric locality (...) and on the terrace of the Tîrziu stream, N. Zaharia also found fragments of bones, anthropic and zoomorphic figurines and a flat stone axe belonging to the developed Neolithic (Cucuteni phase A)”.

- ran.cimec.ro cimec map Tumular necropolis Daco-Roman period (3rd - 4th century) RAN 147081.01 LMI code (List of Historical Monuments) List of Historical Monuments from 2010, SV-I-s-B-05398 (accessed: April 2025).

- Secuta, Moldavia (1892-1898) map https://maps.arcanum.com/en/map/romania- 1892/?layers=22&bbox=2968946.7689266833%2C6061625.993676056%2C2975910.6244568615%2C6064161.797620838 (accesed: April 2025). [tr.n.] "The groundwater is at a depth of 6-18 m, and in some places, it reaches 30 m. (...) The Moldova River has an unstable riverbed and often causes floods. Also, on the commune's territory, the Risca stream is confluent with the Moldova River, which increases the risk of these floods. The hydrographic network is formed by the Moişa and Săcuţa streams that flow into Saca, the latter into the Risca River and Risca into the Moldova River. When it rains, the flow of these streams is very high, and when there is drought, the streams dry up completely (hence the name) due to the bed formed by very permeable rocks".

- https://www.comunaboroaia.ro/muzeul-neculai-cercel/ (accesed: April 2025).

- http://boroaia.uv.ro/5.htm (accesed: April 2025). [tr.n.]"inhabitants of Boroaia village came from Transylvania between 1742 and 1774, which constitute two certain historical references; One (1742) that does not include the Boroaia among the estates of the monasteries Râzca, Neamt and Secu, another that includes (1774) as the estates of these three monasteries, when their captain, Bora, dying, remained the woman of Boroaia (Bora's feminine)”.

- https://dragusanul.ro/povestea-asezarilor-sucevene-boroaia/ (accesed: April 2025). [tr.n.] "1899: It is published towards the general knowledge that, on November 18, 1899, 11 hours, will be held, in the premises of the City Hall of the respective communes on which each of the goods noted below, oral public auction for leasing the lands, of hay and of the mountain hollows for the pasture, by their land, Boroaia: (...) C. Family name (7 ha, 8000 sqm)".

- Ion Ghinoiu, (coordonator general), Habitatul. Răspunsuri la chestionarele Atlasului Etnografic Român (Volumul IV Moldova, ISBN 978-973-8920-23-1 Ed. Etnologică, București, 2017), 39, 140, 143-144, 451-454.

- Martin Brown, FutuRestorative: Working Towards a New Sustainability (RIBA Publishing, 2016) https://fairsnape.com/2016/03/23/futurestorative-working-towards-a-new-sustainability/ (accessed: April 2025).

- https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcoverexplorer/ (accessed: April 2025).

- https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (accessed: April 2025).

- https://geoportal.ancpi.ro/imobile.html (accessed: April 2025).

- https://www.wkcgroup.com/tools-room/carbon-sequestration-calculator/ (accessed: April 2025).

- https://www.biodiversity-metrics.org/understanding-biodiversity-metrics.html (accessed: April 2025).

- https://www.grestool.org/ (accessed: April 2025).

- Jacqueline Theis, Christopher Woolley, Philip J Seddon, Danielle F. Shanahan, The New Zealand Biodiversity Factor—Residential (NZBF-R): A Tool to Rapidly Score the Relative Biodiversity Value of Urban Residential Developments (MDPI Land, March 2025 - 14(3):526,) https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030526 (accessed: July 2025).

- Aqua Prociv Proiect, Company, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, "Renaturation of Zerind & Tămaşda polders, Arad and Bihor counties” (Romania Team Project: Concept Sketch & cad drawing landcape design - Arch. Nina Cristina Dițoiu; Cad Drawings & Hidrotechnical Design - Eng. Dragoş Gros, Team Coordinator Eng. Dan Săcui).

- Paul Hawken, Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation (Penguin Books: UK, 2021), 198-201, 212-213.

- Ibidem, 210-211.

- Laasri, S., El Hafidi, E., Mortadi, A. et al., Solar-powered single-stage distillation and complex conductivity analysis for sustainable domestic wastewater treatment (Environmental Science and Pollution Research: Volume 31, April 2024, pages 29321–29333) https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-33134-y (accessed: April 2025).

- Laasri, S., El Hafidi, E., Mortadi, A. et al., Solar-powered single-stage distillation and complex conductivity analysis for sustainable domestic wastewater treatment (Environmental Science and Pollution Research: Volume 31, April 2024, pages 29321–29333) https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-33134-y (accessed: April 2025).

- Moritz Laub, Lisa Pataczek, Arndt Feuerbacher, Sabine Zikeli, Petra Högy, Contrasting yield responses at varying levels of shade suggest different suitability of crops for dual land-use systems: a meta-analysis (Agronomy for Sustainable Development: Volume 42, June 2022).

- Dițoiu Nina Cristina’s concept sketch, coordinator Aqua Prociv Proiect team Eng. Dan Săcui. "Renaturation of Zerind polder, Arad county” & ”Renaturation of Tămaşda polder, Bihor county”.

- David Lin, Laurel Hanscom, Adeline C Murthy, Alessandro Galli, Mikel Cody Evans, Evan Neill, Maria Serena Mancini and others, Ecological Footprin Accounting for Countries: Updates and Results of the National Footprint Accounts, 2012-2018 (MPDI Resources: September 2018, 7(3):1-22, License CC BY 4.0). https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7030058 (accessed: April 2025).

- CADASTRE SOLAIRE 2.0, note no. 148, april 2019, APUR (atelier parisien d'urbanisme) Directrice de la publication: ALBA, Dominique, Note réalisée par: Gabriel SENEGAS, Sous la direction de : Olivier RICHARD, Cartographie et traitement statistique: Apur, www.apur.org. https://www.apur.org/fr/nos-travaux/vers-un-cadastre-solaire-2-0 (accessed: April 2025).

- Peter J. Kindel, Biomorphic Urbanism: A Guide for Sustainable Cities (Why ecology should be the fondationa of urban development: Medium SOM, Apr 2019). https://som.medium.com/biomorphic-urbanism-a-guide-for-sustainable-cities-4a1da72ad656 (accesed: april 2025).

- Aristide Athanassiadis, https://www.circularmetabolism.com/ (accessed: April 2025).

- similar to Apur document about Seine Valley-Agricultural and food dynamics: Vallee de la Seine, enjeux & perspectives, Dynamiques agricoles et alimentaires, Coopération des agences d’urbanisme APUR, AUCAME, AURBSE, AURH, L'INSTITUTE, Vallée de la Seine, contrat de plan inter-régional État-Régions Vallée de la Seine, 2021.

- https://www.hydrogrid.ai/g-resources/resilience-in-hydropower-operations?utm_source=p[?]m=hydro review&utm_campaign=resilience-hydropower-whitepaper (accessed: April 2025).

- Carlos Tapia, Marco Bianchi, Mirari Zaldua, Marion Courtois, Philippe Micheaux Naudet, Andrea Bassi, Philippe Micheaux Naudetand others, CIRCTER - Circular Economy and Territorial Consequences (ESPON: Applied Research, Final Report 2019), 7. https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/circter_fr_main_report.pdf (accesed: April 2025).

- Carolin Bellstedt, Gerardo Ezequiel Martín Carreño, Aristide Athanassiadis, Shamita Chaudhry, METABOLISM of CITIES (CityLoops-D4.4–Urban Circularity Assessment Method, Version 1.0 ), 35. https://cityloops.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Materials/UCA/CityLoops_WP4_D4.4_Urban_Circularity_Assessment_Method_Metabolism_of_Cities.pdf (accesed: April 2025).

- Christopher Alexander, The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe-The Phenomenon of Life (Center for Enviromental Structure, Berkeley, California, 2014, first ed. 1980), 15.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_map_of_countries_by_ecological_deficit_(2013).svg (accessed:April 2025).

- Erica Honeck, Arthur Sanguet, Martin A. Schlaepfer, Nicolas Wyler, Anthony Lehmann, Methods for identifying green infrastructure (SN: Applied science 2020). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42452-020-03575-4 (accesed: april 2025).

- https://www.turbulent.be/projects (accesed: april 2025).

- https://www.hydrogrid.ai/g-resources/resilience-in-hydropower-operations?utm_source=p[?]m=hydro review&utm_campaign=resilience-hydropower-whitepaper (accessed: April 2025).

- Peter Droege, ed., Urban Energy Transition, Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2018), 31-49, 85-113.

- Stefan Sagmeister, Jesssica Walsh, Sagmeister & Walsh – Beauty (Book: Phaidon Press Ltd, ISBN 9780714877273, Nov 2018, London), 269.

- David Seamon, Place, Place Identity, and phenomenology: a triadic Interpretation based on J.G. Bennett's Systematics (The Role of Place Identity in Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments, Editors: Hernan Casakin and Fatima Bernardo, Bentham Science Publishers, 2012).

- Dilip da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers: Alexander's Eye and Ganga's Descent (Publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, Feb. 2019) (chapter Waters of Eden), 123-136. (describes four rivers sourced in paradise), 126. (the city manipulates only the earth surface), 155, 273-294. (After rivers (...) extreme hydraulic engineering), 290.

- Stefan Sagmeister, Jesssica Walsh, Sagmeister & Walsh - Beauty (Book: Phaidon Press Ltd, ISBN 9780714877273, Nov 2018, London), 25.

- Diţoiu, Nina Cristina., Mihaela Ioana Maria Agachi, Mugur Balan, Newness touches conventional history: the research of the photovoltaic technology on a wooden church heritage building (WMCAUS 2020 IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 960 (2020) 022055 IOP Publishing Part of ISSN: 1757-899X).

- Martin Heidegger, Întrebarea privitoare la tehnică, in: Originea operei de artă, translated by Gabriel Liiceanu after: Die Frage nach der Technik (Vortrage und Aufsatze, Teil I, Neske, Pfullingen, 1967), 120-169. (reprint, Bucharest: Humanitas, 2011), 134.

- Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology (Basic Writings: Martin Heidegger, Ed. David Farrell Krell, New York: Harper Collins, 1993), 311-341.

- Neil Leach, Uitati-l pe Heidegger/Forget Heidegger (bilingv, Ed. Paideia, Bucuresti, Romania, 2006, translated by Magda Teodorescu, Dana Vais), 33-34, 66.

- David Seamon, Life take place, op. cit., 43-51.

- Nina Cristina Dițoiu, Ph. D. Thesis – Summary "The regenerative culture of the built environment: Multicriteria decisions in the double-way spiral",2023, Holistic visual methodology applied on all scales from distinct areas: 4 case studies on the Architectural OBJECT scale, including a church restoration and a bioclimatic administrative building, 2 case studies on the LOCALITY scale, and 3 case studies on the TERRITORY scale. The case studies can be extended to support other areas on both a larger and smaller scale.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).