1. Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a prevalent and debilitating mood disorder that extends beyond individual suffering, significantly impairing social and professional functioning. With relapse rates ranging from 50% to 85% [

1], MDD presents a substantial burden on both individuals and healthcare systems, necessitating effective long-term management strategies. Beyond its emotional and psychological toll, MDD is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality, increasing the risk of suicide and a range of comorbid medical conditions [

2]. Individuals with MDD often experience severe functional impairments, negatively affecting interpersonal relationships and overall quality of life. Moreover, depression is frequently associated with cardiovascular, metabolic, and endocrine disorders, as well as substance use disorders, all of which contribute to increased mortality rates and a shortened life expectancy in affected individuals. Depression has also been recognized as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, particularly coronary heart disease (CHD). Studies indicate that individuals with depression are at a significantly higher risk of developing CHD, with anxiety and depression prevalence rates of 21% and 13%, respectively, in CHD patients [

3]. The complex interplay between MDD and these medical comorbidities highlights the urgent need for integrated treatment approaches that address both mental and physical health to improve overall patient outcomes.

Recent evidence underscores the global burden of mental disorders among children and adolescents, emphasizing the early onset and persistence of these conditions. A comprehensive analysis based on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 data [

4] estimates that approximately 293 million individuals aged 5 to 24 years—representing 11.63% of this population—experience at least one mental disorder. The prevalence rises with age, increasing from 6.80% in children (5–9 years) to 12.40% in early adolescence (10–14 years), 13.96% in mid-adolescence (15–19 years), and 13.63% in young adulthood (20–24 years). These findings highlight the critical need for early intervention strategies to prevent long-term psychological and functional impairments. Given the high prevalence of depression within this demographic, developing innovative, scalable, and accessible therapeutic approaches remains a pressing global mental health priority.

Despite extensive research and the availability of multiple treatment modalities, response rates for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) remain suboptimal. Pharmacotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are standard first-line interventions; however, recent evidence suggests their effectiveness may be overestimated due to methodological limitations such as publication bias and researcher allegiance. For instance, studies have found that the efficacy of psychological interventions for depression has been overestimated in the published literature, just as it has been for pharmacotherapy [

5]. Additionally, researcher allegiance has been identified as a potential source of bias in randomized clinical trials of psychological interventions [

6]. Moreover, head-to-head comparisons of psychotherapies versus pharmacotherapies reveal negligible differences, while combined treatment offers only a modest benefit over monotherapy [

7]. These findings highlight the urgent need for novel or adjunctive therapeutic strategies to enhance treatment outcomes.

One promising alternative intervention is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). tDCS is a non-invasive brain stimulation technique that modulates cortical excitability and has shown promise in alleviating depressive symptoms, with current level of evidence A [

8]. Growing evidence from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses suggests that tDCS may serve as an effective adjunct to conventional treatments for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Meta-analyses have further corroborated the efficacy of tDCS in treating depression. A comprehensive review encompassing multiple randomized controlled trials found that tDCS interventions effectively alleviate depressive symptoms, with specific parameters—such as a 2-mA current and 30-minute sessions—enhancing treatment outcomes [

9]. Additionally, tDCS has demonstrated the potential to reduce suicidal ideation and provide sustained antidepressant effects [

10]. Studies have shown that targeting the left DLPFC can significantly improve depressive symptoms for a month or longer, indicating the durability of tDCS benefits. These findings position tDCS as a promising alternative or adjunctive intervention for MDD, particularly for patients who have not responded adequately to traditional therapies.

One of the key neurobiological rationales for using tDCS in MDD is based on electrophysiological evidence of frontal alpha asymmetry observed in resting electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings. Individuals with MDD often exhibit reduced activity in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) relative to the right, a pattern associated with emotional dysregulation and depressive symptomatology [

11]. This imbalance is hypothesized to underlie vulnerability to depression, as greater left DLPFC activation correlates with approach motivation, whereas greater right DLPFC activity is associated with withdrawal and avoidance behaviors [

12]. Recent research has examined the correlation between frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) and major depressive disorder (MDD). A 2023 meta-analysis investigated resting FAA as a prospective biomarker for MDD, evaluating data from 23 studies with 1,928 MDD subjects and 2,604 controls. The research showed that individuals with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) displayed increased right frontal EEG alpha asymmetry relative to non-depressed individuals, indicating that frontal alpha asymmetry may function as a biomarker for MDD [

13]. The findings corroborate the idea that diminished activity in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) compared to the right is linked to emotional dysregulation and depressive symptoms. This imbalance may predispose individuals to depression, as heightened left DLPFC activation coincides with approach desire, whereas increased right DLPFC activity is linked to withdrawal and avoidance tendencies.

By delivering a low-intensity direct current (typically 1–2.5 mA) through scalp electrodes for 10–30 minutes, tDCS can depolarize or hyperpolarize neuronal membranes, effectively modulating cortical excitability [

14]. The most common electrode montage involves placing the anode (excitatory) over the left DLPFC and the cathode (inhibitory) over the right DLPFC or positioning the anode over the left DLPFC and the cathode over the right supraorbital region, therefore restoring the inter-hemispheric imbalance [

15]. While tDCS has been shown to alleviate MDD symptoms, its synergistic potential as an adjunct to psychotherapy remains largely unexplored. Given that both CBT and tDCS target overlapping neurocognitive mechanisms—specifically, prefrontal regulation of affect and cognition—there is a strong theoretical basis for combining these interventions to enhance therapeutic outcomes. A study protocol by Carvalho et al. (2020) proposed investigating the clinical and mechanistic effects of combining CBT and tDCS in MDD treatment. Building on this foundation, the present study aims to investigate the repetitive effects of tDCS combined with individualized CBT in alleviating depressive symptoms in individuals with mild to moderate MDD who are CBT-naïve. We hypothesize that combining tDCS with CBT will produce a synergistic effect, enhancing the efficacy of CBT and leading to greater clinical improvements compared to CBT alone. Additionally, we aim to examine the long-term effects of these interventions, assessing their sustained impact over a three-month follow-up period

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Study Registration

This study was conducted in accordance with the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Subcommittee on Ethics for Life and Health Sciences (SECVS) at the University of Minho (Approval No. SECVS 174/2017). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The study protocol was registered with the United States National Library of Medicine Clinical Trials Registry (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03548545) on June 7, 2018 (Protocol Version 1). Further methodological details are available in the published protocol by Carvalho et al. (2020): clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03548545.

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Eligibility Criteria

Participants were recruited through multiple sources, including social media advertisements, flyers distributed throughout the city of Braga, and institutional mailing lists from the University of Minho. Eligibility was restricted to individuals experiencing an acute major depressive episode who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). To ensure a well-characterized sample, the following inclusion criteria were applied: participants had to be between 18 and 75 years of age, present a diagnosis of unipolar, non-psychotic MDD, and score ≥7 on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and ≥10 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Additionally, all participants were required to demonstrate low suicide risk as assessed during a structured clinical interview, and to possess the cognitive and legal capacity to provide written informed consent. Exclusion criteria encompassed any contraindications to transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), such as the presence of metal implants in the head or implanted cranial medical devices. Participants were also excluded if they had significant or unstable neurological or psychiatric disorders other than MDD, including but not limited to epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, eating disorders, or obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Additional exclusion criteria included a history of substance abuse within the previous six months, a diagnosis of personality disorders, or any severe medical condition likely to impair functional status during the study period (e.g., active cancer, or serious cardiac, renal, or hepatic conditions). Although the original study protocol excluded individuals receiving psychopharmacological treatment, an amendment was implemented to include participants undergoing stable pharmacotherapy. This adjustment was made to enhance the external validity and clinical relevance of the findings, while maintaining methodological integrity.

2.3. Study design

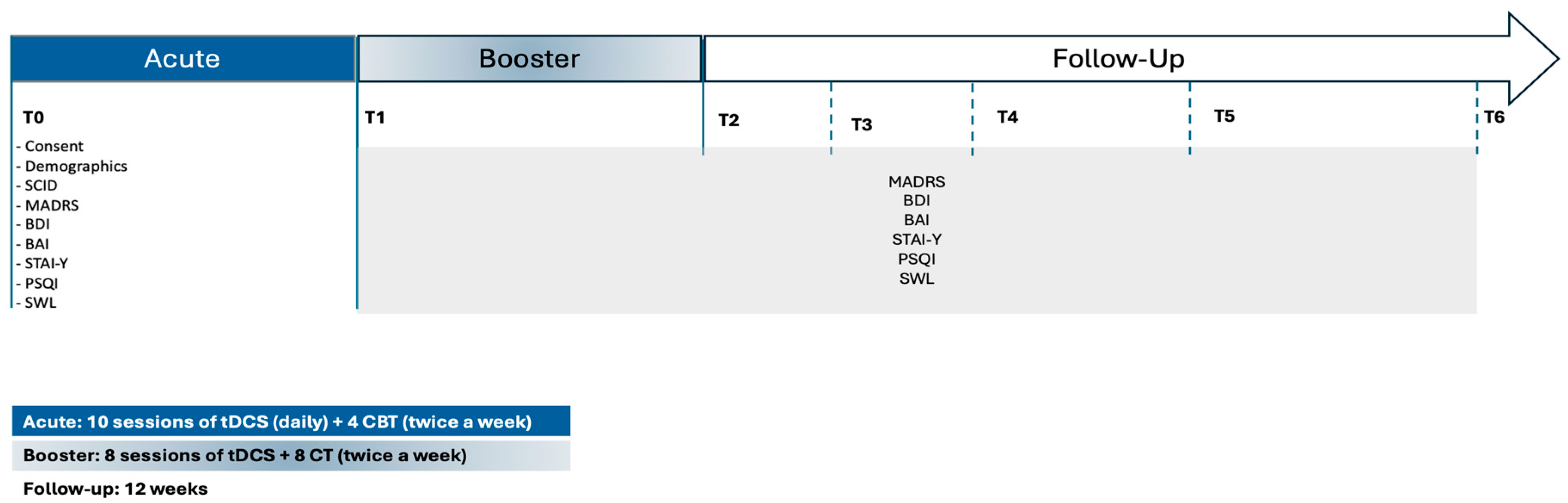

The present randomized, double-blind, controlled pilot trial was designed to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of combining transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in adults diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). The intervention spanned a total duration of six weeks. Participants were randomly allocated to one of two conditions: active tDCS paired with CBT or sham tDCS paired with CBT. Each participant completed 18 sessions of tDCS (active or sham) and 12 sessions of CBT, implemented in accordance with a standardized treatment protocol (

Figure 1).

The intervention was structured into two consecutive phases. The acute treatment phase, corresponding to the first two weeks, consisted of 10 consecutive weekday sessions of tDCS (Monday to Friday). During this period, no CBT sessions were administered. The reinforcement phase, covering weeks three to six, incorporated two weekly tDCS sessions (on Mondays and Fridays), each lasting 30 minutes. CBT was introduced during this phase, with participants attending a total of four individual therapy sessions delivered by a licensed clinical psychologist. Clinical assessments were conducted at seven key time points: baseline (prior to randomization), end of the acute phase (week 2), end of the reinforcement phase (week 6), and at four post-intervention follow-up intervals (2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks). This schedule allowed for the evaluation of both immediate and sustained treatment effects. All study procedures—including clinical evaluations, neuromodulation sessions, and psychotherapy—were carried out at the Clinical Service of the School of Psychology, University of Minho. Participants were referred by Primary Care Physicians, ensuring a clinically representative cohort of individuals actively seeking treatment for depressive symptoms.

2.4. Randomization and Blinding Procedures

Randomization procedures followed the protocol outlined by Carvalho et al. (2020). After confirming eligibility and obtaining written informed consent, participants were randomly assigned to one of two intervention arms—active tDCS combined with CBT or sham tDCS combined with CBT—using a computer-generated, web-based randomization system. A 1:1 allocation ratio was applied to ensure balanced group distribution. To preserve allocation concealment and ensure methodological rigor, the randomization sequence was stored in sealed, opaque envelopes and accessed only at the time of assignment. Blinding was maintained across multiple levels of the study: participants, CBT therapists, clinical assessors, and data analysts were all blinded to group allocation throughout the trial. Due to the technical requirements of stimulation delivery, the research staff responsible for administering tDCS were not blinded, as they were required to implement specific stimulation parameters. No serious adverse events were observed during the course of the study. In the event of an adverse event requiring unblinding, the Principal Investigator was authorized to disclose the participant’s group allocation and report the incident to the Ethics Committee within 24 hours, in accordance with institutional and ethical safety protocols.

2.5. Screening and Baseline Assessment

Individuals who expressed interest in participating were initially screened through a structured intake process to evaluate eligibility for study inclusion. During this initial contact, a standardized questionnaire was administered to assess compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as suitability for transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and electroencephalogram (EEG) procedures. Potential participants were fully informed of the study’s aims, procedures, and potential risks, and had the opportunity to ask questions prior to providing written informed consent. Eligible participants were then scheduled for the baseline assessment (T0). During this session, participants completed standardized demographic and medical history questionnaires, followed by administration of the primary clinical outcome measures: the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Individuals who met the eligibility criteria based on these assessments proceeded to complete the secondary outcome measures, including the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). To confirm the presence of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) according to DSM-5 criteria, participants underwent a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5), conducted by a trained clinician. The entire baseline assessment protocol required approximately two hours to complete.

2.6. Intervention Phases and Follow-Up Assessments

Following the baseline assessment (T0), participants entered the acute treatment phase, which spanned two weeks. During this phase, individuals received 10 consecutive weekday sessions of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), administered Monday through Friday. Each session consisted of either active or sham stimulation at 2 mA for 30 minutes. In parallel, participants began cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), attending two sessions per week (Monday and Friday), totaling four sessions during this initial phase. At the end of the acute treatment phase (T1; week 2), participants underwent a comprehensive reassessment that included the same battery of primary and secondary clinical outcome measures administered at baseline. Participants then transitioned into the reinforcement phase, which covered weeks 3 to 6. During this period, they continued to receive two tDCS sessions per week (30 minutes each, on Mondays and Fridays), alongside CBT sessions at the same frequency. Upon completing this phase (T2; week 6), participants underwent a post-treatment evaluation, using the same clinical outcome measures. In addition to clinical assessments, three-minute resting-state EEG recordings were obtained at T0, T1, and T2. As EEG analyses fall outside the scope of the present manuscript, those data will be reported in a separate publication (Carvalho et al., 2020). To evaluate the durability of treatment effects, participants were further assessed at four follow-up time points: 2 weeks (T3), 4 weeks (T4), 8 weeks (T5), and 12 weeks (T6) after the conclusion of the intervention. This follow-up period enabled a longitudinal evaluation of symptom trajectories and maintenance of therapeutic outcomes.

2.7. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Protocol

The cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) component of the intervention was structured in accordance with Aaron T. Beck’s cognitive theory of depression and delivered following evidence-based clinical guidelines. Each session lasted approximately 60 minutes and was conducted individually to allow for personalized therapeutic engagement. The intervention was tailored to the severity and specific symptom profile of each participant, with an emphasis on identifying, evaluating, and restructuring maladaptive cognitive patterns, dysfunctional beliefs, and associated behavioral responses contributing to depressive symptomatology. Therapeutic strategies included cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, thought monitoring, and emotion regulation techniques. Sessions also incorporated psychoeducation regarding the cognitive model of depression and relapse prevention strategies in later phases of treatment. The therapeutic process was designed to enhance participants’ coping skills, promote insight into negative automatic thoughts, and foster the development of adaptive problem-solving approaches. All CBT sessions were delivered by a licensed clinical psychologist registered with the Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses (OPP - the official regulatory body for the psychology profession in Portugal), with formal training in cognitive-behavioral therapy. To ensure consistency, fidelity to the treatment model, and adherence to protocol guidelines, weekly supervision meetings were held between the treating psychologist and a senior clinical supervisor (SC), who possessed extensive clinical experience in CBT for mood disorders. Supervision focused on case conceptualization, treatment planning, session content, and addressing therapeutic challenges, thereby ensuring the quality and integrity of the intervention across participants.

2.8. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) Administration

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) was administered using the Eldith DC Stimulator Plus (NeuroConn GmbH, Ilmenau, Germany), a CE-certified device widely employed in clinical and experimental neuromodulation research. Stimulation was delivered through two saline-soaked sponge electrodes (25 cm² each), secured using elastic headbands to ensure consistent placement and contact. Electrode montage followed the international 10–20 EEG system: the anodal electrode was positioned over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) at site F3, and the cathodal electrode over the right DLPFC at site F4. This bilateral frontal configuration is supported by neurophysiological evidence linking prefrontal asymmetry to affective regulation and has been frequently used in studies targeting depressive symptoms. In the active tDCS condition, participants received a constant current of 2 mA (resulting in a current density of 0.80 A/m²) for a total duration of 30 minutes. Stimulation included a 15-second ramp-up and ramp-down to minimize discomfort and prevent sudden perceptual sensations associated with abrupt current onset or offset. In the sham condition, the electrode montage and ramp-up/down parameters were identical to those of the active condition; however, the device automatically discontinued stimulation after 15 seconds of 2 mA current. This brief stimulation period is considered sufficient to mimic the initial tingling sensation experienced in active stimulation, thereby preserving the integrity of the blinding protocol. Each tDCS session lasted approximately 40 minutes, accounting for preparation, electrode placement, and stimulation time. All sessions were conducted in a quiet, controlled environment, with participants seated comfortably in a semi-reclined position to minimize movement and ensure optimal electrode contact. Importantly, tDCS was administered by a trained research assistant who was not involved in any aspect of clinical assessment or cognitive-behavioral therapy delivery. This procedural separation was implemented to preserve the double-blind design, ensuring that therapists, assessors, and participants remained blinded to stimulation condition throughout the study.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Given the small sample size and the non-normal distribution of the data in this pilot study, only non-parametric statistical analyses were performed. To explore potential group differences in sociodemographic characteristics between the active and sham tDCS groups, Chi-Square tests were used for categorical variables, while Mann-Whitney U test was applied to continuous variable. Group differences in psychiatry symptoms across the seven assessment time points were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test, with effect sizes were calculated by Rank-Biserial correlation. Additionally, a secondary analysis was conducted to explore the percentage of symptom improvement over time for each group relative to T0, as well as between-group differences in these percentages. The percentage change score was calculated by dividing each individual’s symptom scores at T1 to T6 by the average symptoms scores of their respective group at T0. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for group comparisons, with effect sizes calculated using the Rank-Biserial Correlation (r). Bivariate correlations between symptoms were analyzed at each assessment time using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Descriptive statistics, group differences, and correlation analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 23. Additionally, all result graphs and effect size calculations were performed using R software.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data

Therefore, from the 13 (n = 13) participants who were initially screened, one participant was excluded due to regular substance use; one participant was excluded due to the additional diagnosis of Tourette Syndrome; and one participant was excluded because he/she started taking psychopharmacological treatment with sertraline.

Ten adults diagnosed with MDD participated in this clinical trial (age:

Mdn = 31,

IQR = 20.5; 60% female). Participants were allocated into either the active group (

n = 6) or the sham group (

n = 4). Overall, 60% of participants had completed high school education, 80% were single, and 50% were employed at the time of the first assessment.

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of participants, comparing the both active and sham groups. All variables presented non-significant differences between the two groups.

3.2. Groups differences on psychiatric symptoms over time

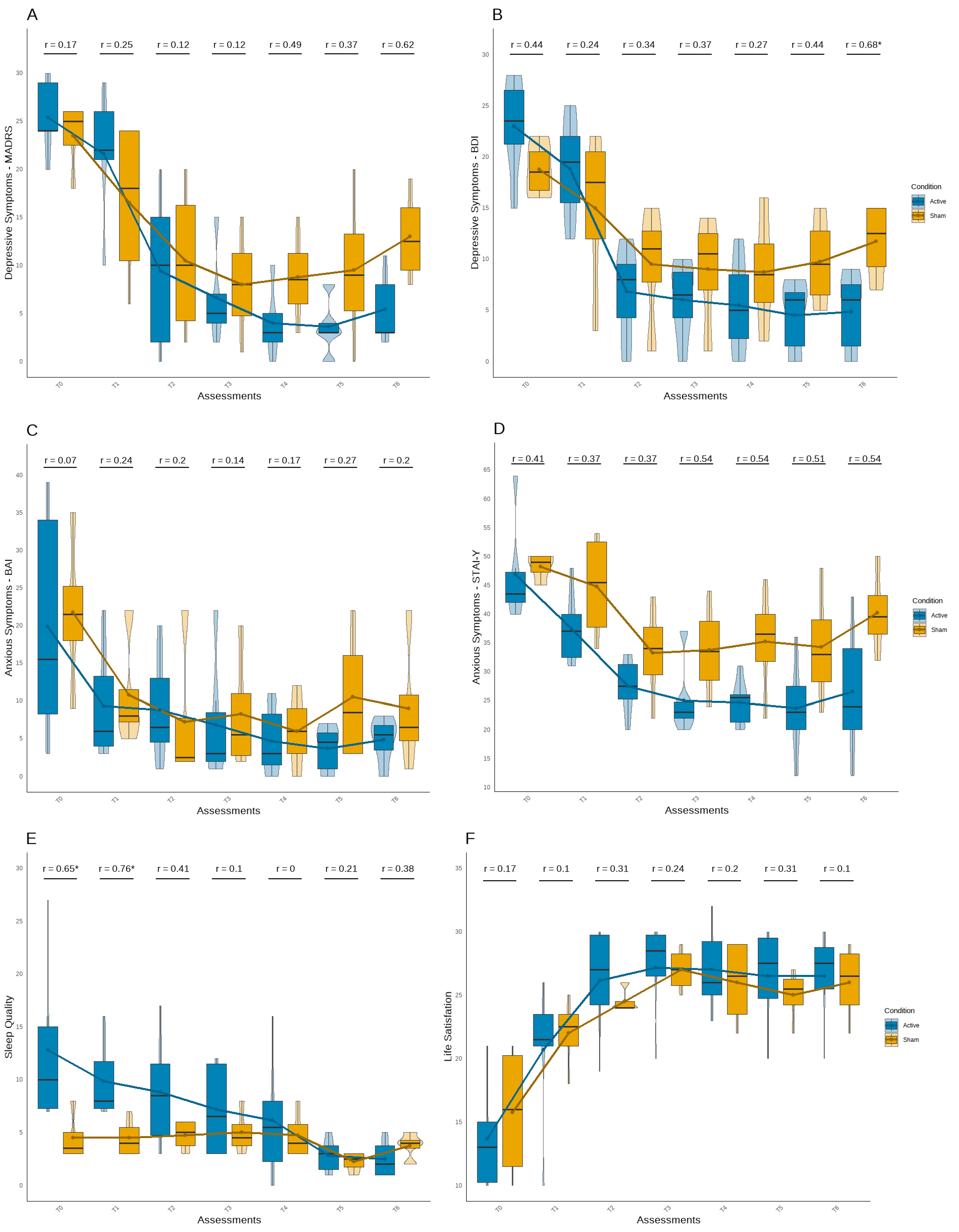

Based on the analysis of differences between the active and sham tDCS groups over time (

Figure 2), symptom improvement was observed in both groups. As expected, the active tDCS group showed greater long-term benefits on most psychological symptoms. Although no significant differences were found in depression symptoms until last follow-up assessment (U = 2.00, Z = -2.15,

p < .05) (

Figure 2A;

Figure 2B), the active tDCS group started with higher mean scores on both instruments. From T2 assessment, this group presented fewer symptoms compared to the sham group, showing scores below the cut-offs for minor depressive symptoms (MADRS < 6; BDI < 9). The effect sizes also suggested a stronger and more consistent group difference at the end of the follow-up period in both questionaries.

Despite no significant differences was verified in anxiety symptoms (

Figure 2C;

Figure 2D), an interesting but non-significant pattern was observed in the STAI-Y1 (

Figure 2D), in which the active tDCS group maintained a decrease in symptoms across all post-baseline assessment points until the end of the experiment, with medium to large effect size values. Although sleep quality scores were better in the sham tDCS group at baseline and T1, with a significant difference (U = 2.50, Z = -2.04,

p < .05; U = 1.00, Z = -2.39,

p < .05), the active tDCS group showed a continuous improvement in sleep quality throughout the experiment, reporting fewer sleep difficulties in last follow-up assessment, but not significant (

Figure 2E). Additionally, both groups demonstrated an improvement in life satisfaction, with no significant group differences or robust effect sizes observed.

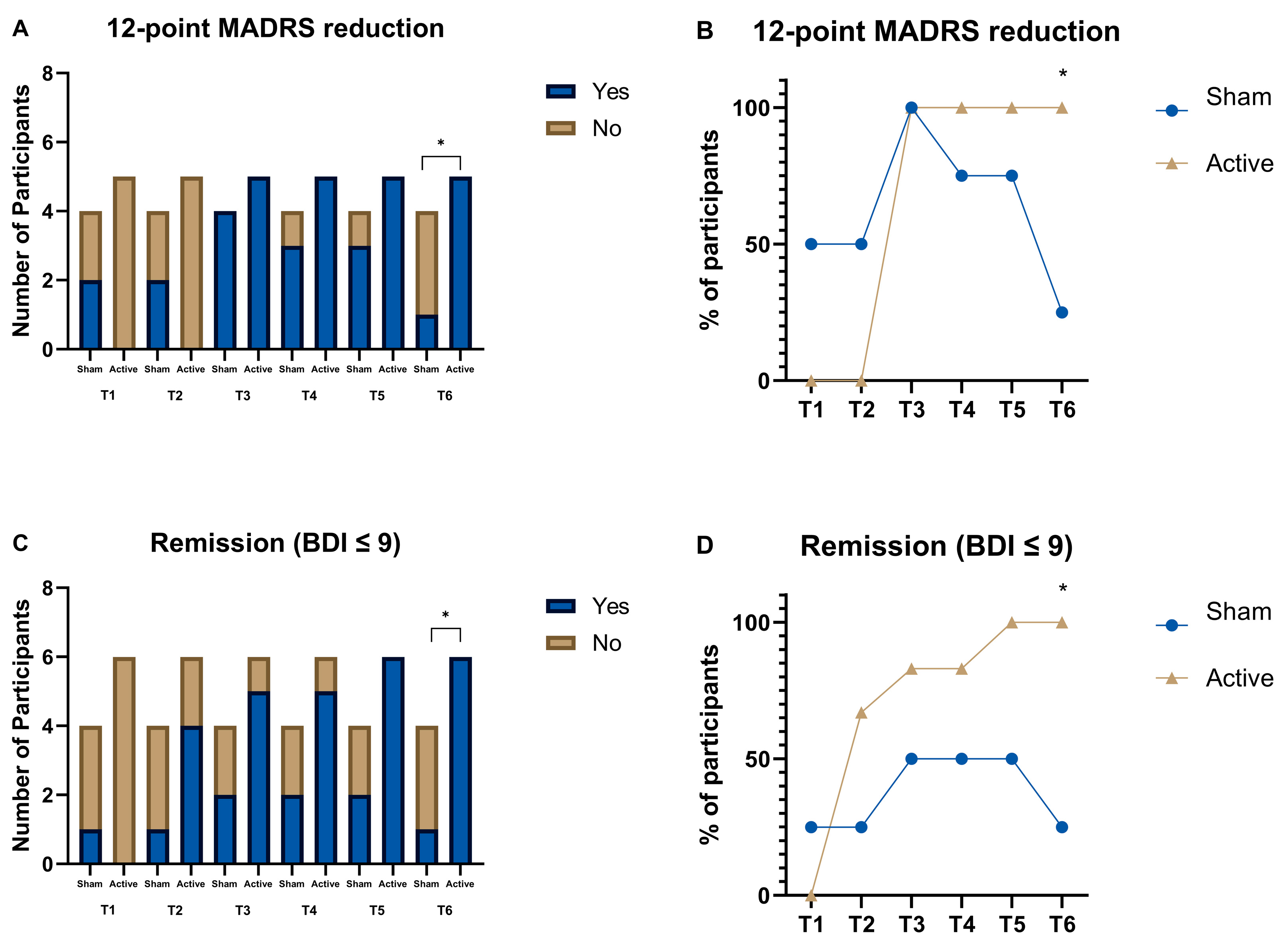

Despite the small sample size, we performed two additional analyses (

Figure 3). The first analysis was based on a 12-point reduction in the MADRS from baseline. This value was chosen because it has been associated in literature with a substantial change in the scores [

16]. Data was categorized as Yes or No, and a Chi-square test was performed for each of the Timepoints. On the last follow-up (T6), there was a substantial change in the scores of those who received active, when comparing to those who received sham tDCS (χ2(1,

n = 9) = 5.625,

p = .018) (

Figure 3A;

Figure 3B). Similarly, when looking at the BDI scores and using as cutoff point of 9 as an indicator of remission [

17], on the last follow-up, those who received active tDCS showed higher remission rates than those that received sham tDCS (χ2(1,

n = 10) = 6.429, p=.011) (

Figure 3C;

Figure 3D). Furthermore, if we look at the eight week follow-up we find a similar trend for the BDI remission scores (χ2(1,

n = 10) = 3.750,

p = .053).

3.3. Psychiatric changes overtime in relation to baseline

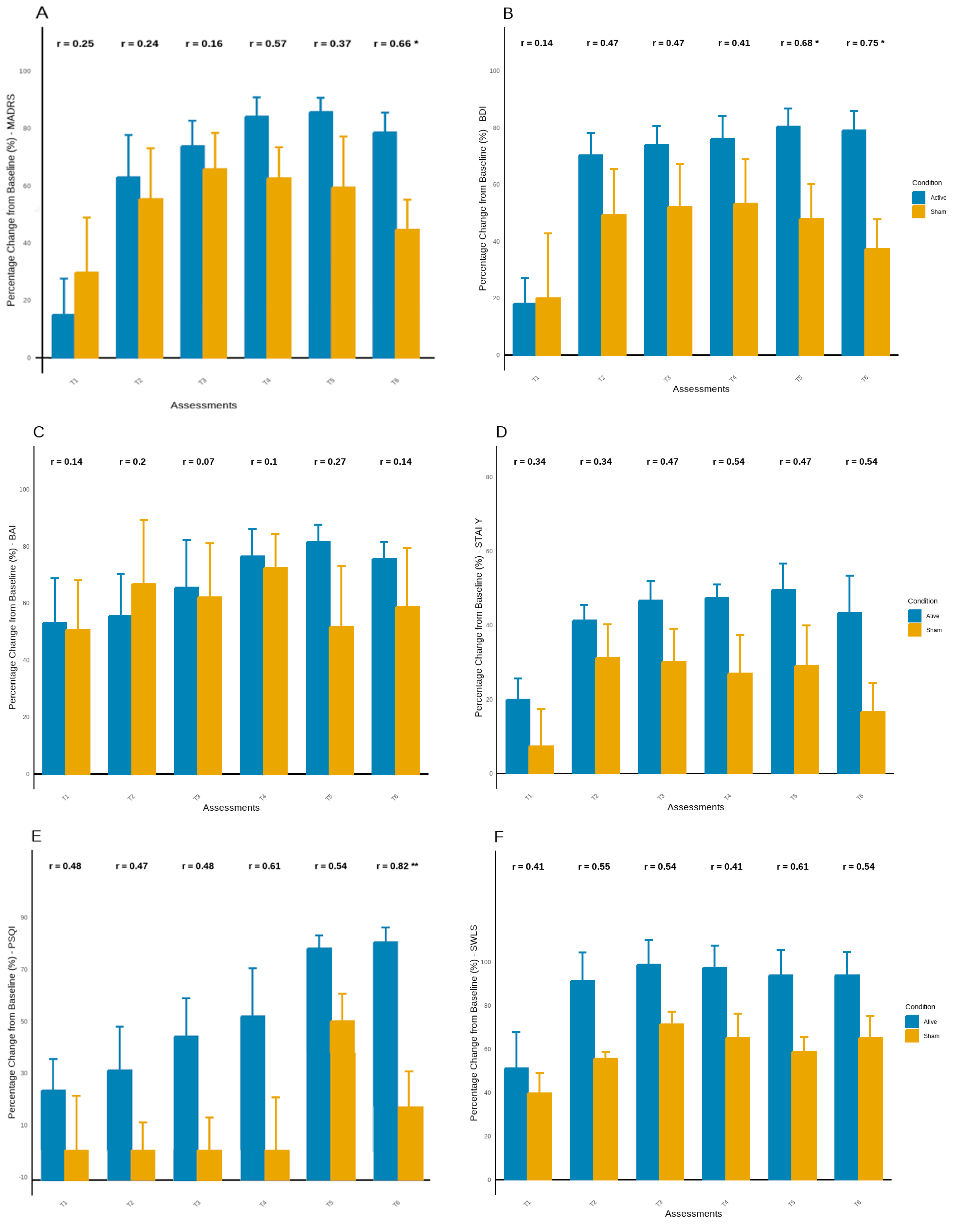

The percentage change in symptoms across each assessment relative to T0 showed consistent improvement in most symptoms in both groups. However, this improvement appears to be more consistent in the active tDCS group, mainly in the latest assessments (

Figure 4). Before the 8-weeks follow-up (T5), the active tDCS group demonstrated an improvement of over 85%, while the sham group improved by approximately 50% to 60%, with significant between-group differences observed in BDI scores (U = 2.00, Z = -2.15,

p < .05) (

Figure 4A;

Figure 4B). Similarly, at the 12 weeks follow-up (T6), the active tDCS group showed an improvement of about 80% in depressive symptoms, while the sham group improved by about 40%, with significant between-group differences found on the MADRS and BDI scores (U = 2.00, Z = -1.97,

p < .05; U = 1.00, Z = -2.37,

p < .05) (

Figure 4A;

Figure 3B). Thus, in addition to the higher improvement in depressive symptoms observed in the active group, this group maintained better results until the last assessment (T6), whereas the sham group experienced an increase in symptoms of more than 20%.

Although no significant findings were observed in anxiety symptoms, results suggest greater improvement in the active tDCS group, with increasing effect sizes between groups during follow-up assessments, mainly in STAI (

Figure 4C;

Figure 4D). Additionally, the active tDCS group showed continuous improvement in sleep quality until the last assessment, with a significant difference at the last time point and an improvement of over 80% from baseline (

p < .05). In contrast, the sham tDCS group ended the experiment with an improvement of around 15% (

Figure 4E). No significant findings were observed in life satisfaction, however the active tDCS group maintained higher levels compering with sham group until the end of experiment, with higher effect sizes (

Figure 4F). No significant findings were observed in life satisfaction. However, the active tDCS group maintained higher levels compared to the sham group until the end of the experiment, with larger effect sizes (

Figure 4F).

3.4. Correlations in psychiatric symptoms over time

Correlations Between Depression, Anxiety, Sleep, and Life Satisfaction Over Time

The correlations between symptoms emerged from the last assessment after the intervention (tabele 2). In addition to the positive relationship between changes in depressive and anxiety symptoms during these assessments (

p < .001 to

p < .05), a negative relationship was found at T2 between changes in life satisfaction perception and anxiety levels (

p < .05). Two weeks after the intervention, a positive relationship was observed between changes in depressive symptoms and life satisfaction (

p < .05) (

Table 2). At the second follow-up assessment, a positive relationship was found between changes in depressive symptoms and sleep quality perception (

p < .05) (

Table 2). Eight weeks after the intervention, results indicated a negative relationship between changes in anxiety symptoms and self-satisfaction with life (

p < .05) (

Table 2). At the final assessment, 12 weeks post-intervention, a negative relationship was also observed between life satisfaction and sleep quality (

p < .05) (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

The present pilot study investigated the prospective long-term advantages of integrating tDCS with individualized CBT in persons diagnosed with MDD. In accordance with our hypothesis and previous research, participants undergoing CBT plus a-tDCS exhibited more significant reductions in depressive symptoms over time compared to those receiving CBT with sham stimulation. Significantly, these effects intensified throughout subsequent follow-up evaluations (especially at 8 and 12 weeks), substantiating the idea that the advantages of neuromodulation may develop progressively and endure beyond the active treatment period.

Consistent with prior research indicating improved results from the combination of neuromodulation and pharmaceuticals in depression [

18,

19,

20], our findings broaden this evidence to encompass psychological therapies, particularly CBT. Previous studies have repeatedly demonstrated that active tDCS, when administered in conjunction with antidepressants like sertraline, escitalopram, or venlafaxine, yields better results than either treatment alone. This indicates a synergistic effect of tDCS when combined with therapies that influence neurochemical or neurocognitive pathways. Nevertheless, the literature examining the synergistic potential of tDCS alongside psychotherapy is still very limited. Nejati et al. (2017) [

21] conducted one of the few research in this domain, finding that the integration of tDCS with short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy resulted in significant and enduring decreases in depressive symptoms. Although promising, that study utilized a distinct therapeutic modality, thereby constraining the generalizability of its findings to evidence-based procedures such as CBT.

Alongside the primary goal of depression, the active tDCS group demonstrated incremental enhancements in sleep quality and anxiety symptoms, although these improvements did not achieve statistical significance at every assessment interval. Nonetheless, a trend of consistent improvement was noted, especially in subsequent evaluations. Furthermore, strong relationships between depressed symptoms and secondary domains—such as anxiety, sleep, and life satisfaction—indicate a cascading effect of symptom alleviation. These findings corroborate previous studies [

22,

23,

24], suggesting that therapies aimed at core depressed symptoms may indirectly mitigate comorbid psychiatric issues. Consequently, our data endorse the perspective that symptom alleviation in one area (e.g., depression) can facilitate more extensive psychological enhancements.

These results are also provided in

Figure 3 which shows that response and remission rates increased progressively over time for participants receiving active tDCS. By the last follow-up (T6), markedly more people in the active group clinically responded (defined as a minimum 12-point reduction in MADRS) and ended up in remission (BDI score ≤ 9). This affirms the therapeutic benefit of the combined intervention is both sustained and accumulating. Also, correlational patterns depicted in Figure 5 showed consistent relationships with reduction of depressive symptoms and improvement of anxiety and sleep quality. This suggests that there might be some kind of dependency in symptom alleviation, where the early mitigation of depression benefits comorbid domains and, in turn, significantly expands the effects of treatment over time.

This study advances prior research by integrating CBT, acknowledged as a primary intervention for MDD due to its robust empirical backing and systematic, skills-oriented methodology. Our findings indicated that the integration of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with active transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) led to a more significant reduction in symptoms, especially during the follow-up phase, implying that neuromodulation may augment the acquisition, retention, or application of cognitive and behavioral techniques acquired during therapy. This is particularly pertinent given the shared neurocognitive aims of both therapies, including the modulation of prefrontal cortex activity and enhancement of cognitive control over emotional reactions. The observation that these advantages were most significant at 8 and 12 weeks post-treatment further substantiates the concept that tDCS may promote neuroplastic alterations that reinforce and prolong the effects of CBT over time.

This pattern of postponed clinical benefit aligns with our previous research with tDCS in several domains. A randomized controlled experiment including persons with spinal cord injury shown that motor cortex (M1) stimulation led to a delayed reduction in pain symptoms, which became meaningful only after the conclusion of the stimulation phase [

25]. The findings indicate that the therapeutic effects of tDCS may entail prolonged neurophysiological changes rather than instantaneous symptom alleviation, thereby elucidating the sustained improvements noted in the current trial. These combined observations support the notion that tDCS can enhance short-term therapeutic results and facilitate enduring alterations in brain function that persist after treatment concludes.

From a mechanistic standpoint, our findings substantiate the hypothesis that diminished activity in the left DLPFC, associated with deficiencies in emotion regulation, can be influenced by focused anodal stimulation [

11,

26,

27]. The bilateral DLPFC montage employed in this investigation aligns with previous evidence affirming its effectiveness in improving cognitive control and emotional processing [

28,

29].The observation of improvements weeks after the cessation of stimulation indicates the potential for brain plasticity and the reinforcement of abilities learned through cognitive-behavioral therapy via better prefrontal functioning.

Despite the promising outcomes, this study presents numerous significant limitations that necessitate careful interpretation of the results. The limited sample size, resulting from recruiting and procedural difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic, substantially restricted the statistical power of our analyses. Consequently, we could not utilize more advanced statistical techniques, such as linear mixed-effects models, which are more effective for identifying small temporal changes and managing missing data in longitudinal studies. This constraint may have resulted in type II errors, especially in the examination of secondary outcomes, when potentially significant trends did not achieve statistical significance.

In addition to the small sample size, the absence of a waitlist or treatment-as-usual control group limits our ability to isolate the specific effects of CBT from natural recovery or placebo influences. While steady medication use was allowed, the absence of categorization for pharmacological treatment presents possible confounding variables. The uniformity of our relatively youthful, CBT-naïve cohort with mild to moderate symptoms limits the generalizability to wider or more intricate clinical populations. Moreover, the 12-week follow-up may inadequately reflect the enduring benefits of the intervention. Ultimately, despite the collection of EEG data, the lack of neurobiological investigation in this publication precludes any inferences regarding the underlying processes of therapy success. Subsequent research should use larger, more heterogeneous samples and multimodal outcome metrics to improve interpretability and translational significance. Furthermore, future research should also include other types of stimulation procedures, such as alternating or random noise stimulation, in order to optimize target engagment [

30,

31,

32]. Recent studies underscore the significance of stimulation parameters—such as duration—in influencing brain activity, as evidenced by transcranial pulsed current stimulation (tPCS) research indexed by EEG. These findings underscore the significance of electrophysiological monitoring in customizing neuromodulatory therapies and enhancing individual responses [

33]. In this regard, future studies should prioritize the identification and monitoring of reliable neurophysiological and neuroimaging biomarkers of transcranial electrical stimulation, as summarized in the comprehensive review by Irwin (2023) [

34]to better elucidate the mechanisms of action and guide personalized interventions.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study suggests that the integration of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may improve treatment efficacy for patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), especially in the long-term relief of symptoms. While both groups were able to achieve benefits from CBT, those who were given active tDCS were able to achieve even greater and longer-lasting reductions in depressive symptoms. Most importantly, these effects were not restricted to the intended therapeutic target of depression, but also included lower levels of anxiety, better sleep, improved satisfaction with life, and overall heightened sense of well-being which supports the idea of enhanced therapeutic effects that, after initial treatment, emerge in an accelerated manner.

The findings support the theory where neuromodulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may synergize with CBT by providing enhancement to neuroplasticity and cognitive control processes. The effects that were noted during follow up assessments highlight the need to consider longer time frames, particularly in reference to measuring the effectiveness of multi-pronged therapy approaches.

Despite these drawbacks, the conclusions drawn from the study add strength to existing literature while simultaneously creating opportunities for further research. Future trials will need to recruit more participants, especially from different ethnic groups, and add neurobiological instruments such as EEG or neuroimaging in order to better understand the theory’s relations and refine treatment approaches. In turn, these results could help develop faster-acting, tailored treatment plans for individuals with Major Depressive Disorder, especially those who do not respond well to traditional treatment methods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and J.L.; Methodology, S.C.; Formal analysis, C.G.C.; Investigation, S.C., J.L., and C.G.C.; Data curation, C.G.C.; Writing – original draft, S.C.; Writing – review and editing, C.G.C. and J.L.; Visualization, S.C.; Supervision, S.C. and J.L.; Project administration, S.C. and J.L.; Funding acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and the Portuguese Ministry of Science, through national funds and co-financed by FEDER through COMPETE2020 under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007653) and is also funded by the FCT grant PTDC/PSI-ESP/29701/2017. This work was conducted at the Psychology Research Centre – CIPsi (PSI/01662), School of Psychology, University of Minho, supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT; UID/01662/2020) through the Portuguese State Budget.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Subcommittee on Ethics for Life and Health Sciences, SECVS) of the University of Minho (protocol code SECVS 174/2017; approved on 20 December 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to ethical and privacy restrictions related to sensitive clinical information, the dataset is not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to all participants who generously gave their time and effort to take part in this study. The authors would like to sincerely thank Patricia Coelho for her valuable assistance with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

| MDD |

Major Depressive Disorder |

| CBT |

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy |

| tDCS |

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| DLPFC |

Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex |

| MADRS |

Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| BDI |

Beck Depression Inventory |

| BAI |

Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| STAI |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| PSQI |

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| SWLS |

Satisfaction With Life Scale |

| EEG |

Electroencephalogram |

| SCID-5 |

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 |

| SECVS |

Subcommittee on Ethics for Life and Health Sciences |

| RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

References

- Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for Recurrence in Depression. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:959–85. [CrossRef]

- Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in Mental Disorders and Global Disease Burden Implications: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:334–41. [CrossRef]

- Bitter I, Szekeres G, Cai Q, Feher L, Gimesi-Orszagh J, Kunovszki P, et al. Mortality in patients with major depressive disorder: A nationwide population-based cohort study with 11-year follow-up. European Psychiatry 2024;67:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kieling C, Buchweitz C, Caye A, Silvani J, Ameis SH, Brunoni AR, et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Disability From Mental Disorders Across Childhood and Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2024;81:347–56. [CrossRef]

- Driessen E, Hollon SD, Bockting CLH, Cuijpers P, Turner EH, Lu L. Does publication bias inflate the apparent efficacy of psychological treatment for major depressive disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis of US National Institutes of health-funded trials. PLoS One 2015;10:1–23. [CrossRef]

- Yoder WR, Karyotaki E, Cristea IA, Van Duin D, Cuijpers P. Researcher allegiance in research on psychosocial interventions: Meta-research study protocol and pilot study. BMJ Open 2019;9:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Guidi J, Fava GA. Sequential Combination of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:261–9. [CrossRef]

- Fregni F, El-Hagrassy MM, Pacheco-Barrios K, Carvalho S, Leite J, Simis M, et al. Evidence-Based Guidelines and Secondary Meta-Analysis for the Use of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2021;24:256–313. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Lam CLM, Peng X, Zhang D, Zhang C, Huang R, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of transcranial direct current stimulation for treating depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021;126:481–90. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Fu Y, Liu C, Meng Z. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex for Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Front Behav Neurosci 2022;16:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Allen JJB, Reznik SJ. Frontal EEG asymmetry as a promising marker of depression vulnerability: Summary and methodological considerations. Curr Opin Psychol 2015;4:93–7. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, RJ. Anterior electrophysiological asymmetries, emotion, and depression: Conceptual and methodological conundrums. Psychophysiology 1998;35:607–14. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, Tang M, Fan X. Meta analysis of resting frontal alpha asymmetry as a biomarker of depression. Npj Mental Health Research 2025;4:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Qi S, Cao L, Wang Q, Sheng Y, Yu J, Liang Z. The Physiological Mechanisms of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation to Enhance Motor Performance: A Narrative Review. Biology (Basel) 2024;13:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho S, Gonçalves ÓF, Brunoni AR, Fernandes-Gonçalves A, Fregni F, Leite J. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation as an Add-on Treatment to Cognitive-Behavior Therapy in First Episode Drug-Naïve Major Depression Patients: The ESAP Study Protocol. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, Tang M, Fan X. Meta analysis of resting frontal alpha asymmetry as a biomarker of depression. Npj Mental Health Research 2025;4:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Guiomar R, Samarra S, Rodrigues M, Martins A, Martins V, Jesus M, et al. Adaptation and preliminary validation of the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) using the Structured Interview Guide (SIGMA) for European Portuguese. Psychologica 2023;66:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Brunoni AR, Moffa AH, Sampaio-Junior B, Borrione L, Moreno ML, Fernandes RA, et al. Trial of Electrical Direct-Current Therapy versus Escitalopram for Depression. New England Journal of Medicine 2017;376:2523–33. [CrossRef]

- Bares M, Brunovsky M, Stopkova P, Hejzlar M, Novak T. Transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) versus venlafaxine ER in the treatment of depression: A randomized, double-blind, single-center study with open-label, follow-up. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019;15:3003–14. [CrossRef]

- Brunoni AR, Machado-Vieira R, Sampaio-Junior B, Vieira ELM, Valiengo L, Benseñor IM, et al. Plasma levels of soluble TNF receptors 1 and 2 after tDCS and sertraline treatment in major depression: Results from the SELECT-TDCS trial. J Affect Disord 2015;185:209–13. [CrossRef]

- Nejati V, Salehinejad MA, Shahidi N, Abedin A. Psychological intervention combined with direct electrical brain stimulation (PIN-CODES) for treating major depression: A pre-test, post-test, follow-up pilot study. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res 2017;25:15–23. [CrossRef]

- Ashworth DK, Sletten TL, Junge M, Simpson K, Clarke D, Cunnington D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: An effective treatment for comorbid insomnia and depression. J Couns Psychol 2015;62:115–23. [CrossRef]

- Carney CE, Edinger JD, Kuchibhatla M, Lachowski AM, Bogouslavsky O, Krystal AD, et al. Cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy for those with insomnia and depression: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Sleep 2017;40:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Groen RN, Ryan O, Wigman JTW, Riese H, Penninx BWJH, Giltay EJ, et al. Comorbidity between depression and anxiety: Assessing the role of bridge mental states in dynamic psychological networks. BMC Med 2020;18:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Thibaut A, Carvalho S, Morse LR, Zafonte R, Fregni F. Delayed pain decrease following M1 tDCS in spinal cord injury: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Neurosci Lett 2017;658:19–26. [CrossRef]

- Brunoni AR, Ferrucci R, Fregni F, Boggio PS, Priori A. Transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of major depressive disorder: A summary of preclinical, clinical and translational findings. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2012;39:9–16. [CrossRef]

- Wolkenstein L, Plewnia C. Amelioration of cognitive control in depression by transcranial direct current stimulation. Biol Psychiatry 2013;73:646–51. [CrossRef]

- Moreno ML, Vanderhasselt MA, Carvalho AF, Moffa AH, Lotufo PA, Benseñor IM, et al. Effects of acute transcranial direct current stimulation in hot and cold working memory tasks in healthy and depressed subjects. Neurosci Lett 2015;591:126–31. [CrossRef]

- Segrave RA, Arnold S, Hoy K, Fitzgerald PB. Concurrent cognitive control training augments the antidepressant efficacy of tDCS: A pilot study. Brain Stimul 2014;7:325–31. [CrossRef]

- Lema A, Carvalho S, Fregni F, Gonçalves ÓF, Leite J. The effects of direct current stimulation and random noise stimulation on attention networks. Sci Rep 2021;11:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Pan R, Ye S, Zhong Y, Chen Q, Cai Y. Transcranial alternating current stimulation for the treatment of major depressive disorder: from basic mechanisms toward clinical applications. Front Hum Neurosci 2023;17:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Li D, Ye F, Liu R, Feng Y, Feng Z, et al. Effect of add-on transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) in major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Stimul 2024;17:760–8. [CrossRef]

- Vasquez A, Malavera A, Doruk D, Morales-Quezada L, Carvalho S, Leite J, et al. Duration Dependent Effects of Transcranial Pulsed Current Stimulation (tPCS) Indexed by Electroencephalography. Neuromodulation 2016;19:679–88. [CrossRef]

- Irwin CL, Coelho PS, Kluwe-Schiavon B, Silva-Fernandes A, Gonçalves ÓF, Leite J, et al. Non-pharmacological treatment-related changes of molecular biomarkers in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2023;23:1–10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).