Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

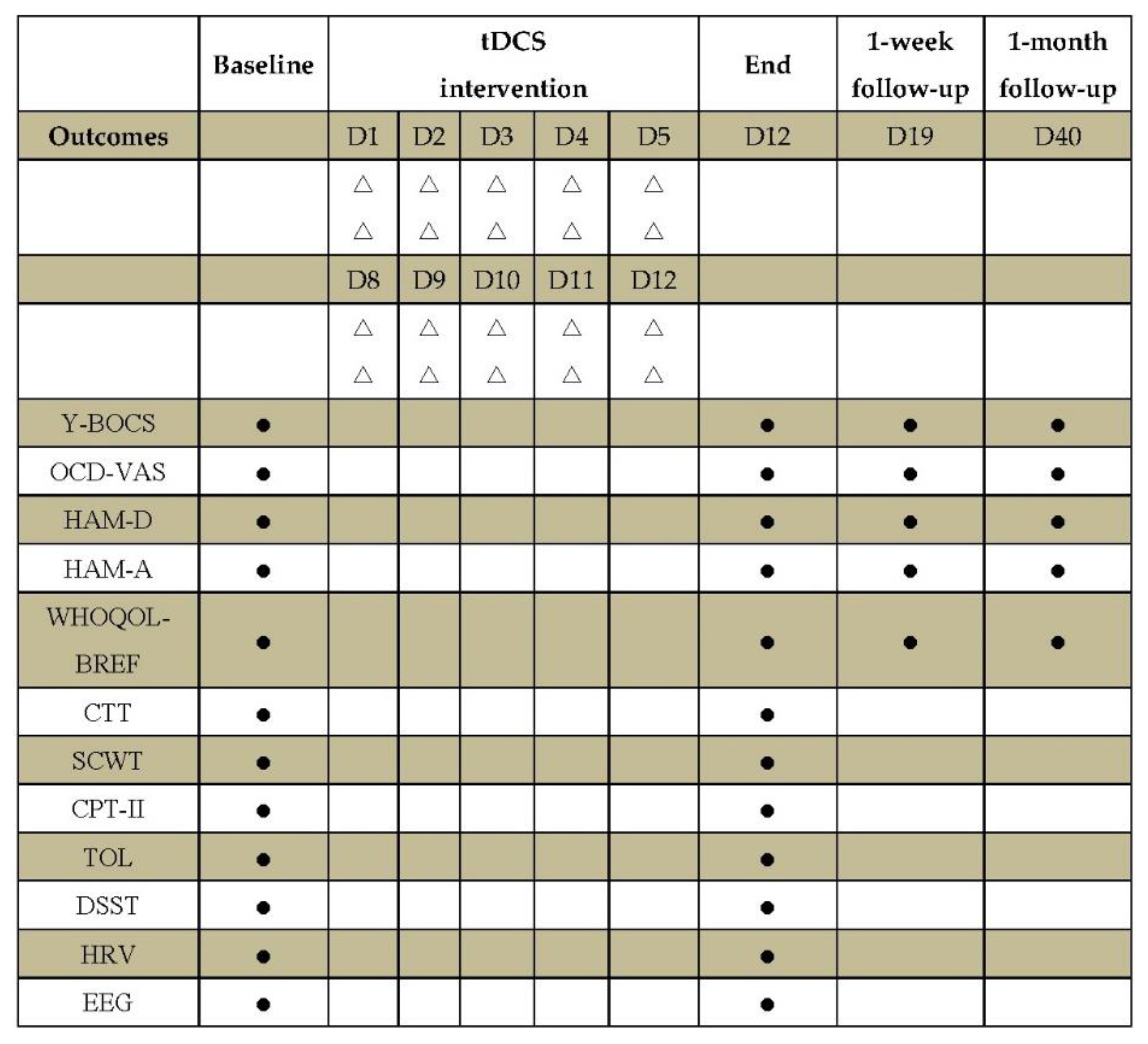

2.3. Clinical Outcome Measures

2.4. Neuropsychological Outcomes

2.5. Neurophysiological Outcomes

2.5.1. Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

2.5.2. Electroencephalogram (EEG)

2.5.3. Functional Connectivity Analysis in EEG Source Space

2.6. Sample Size Calculation

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

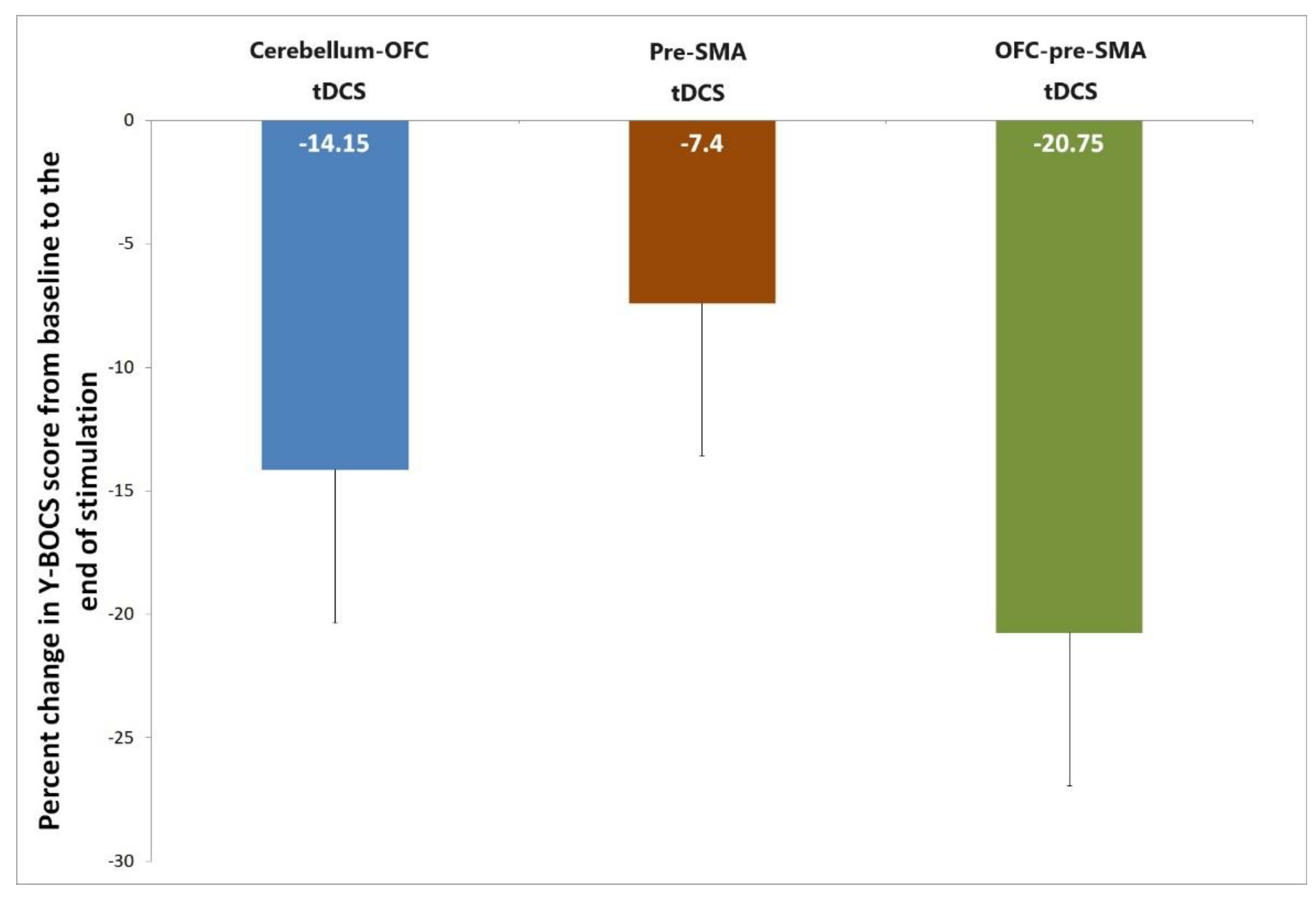

3.2. Primary Outcome

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

3.4. Safety and Tolerability

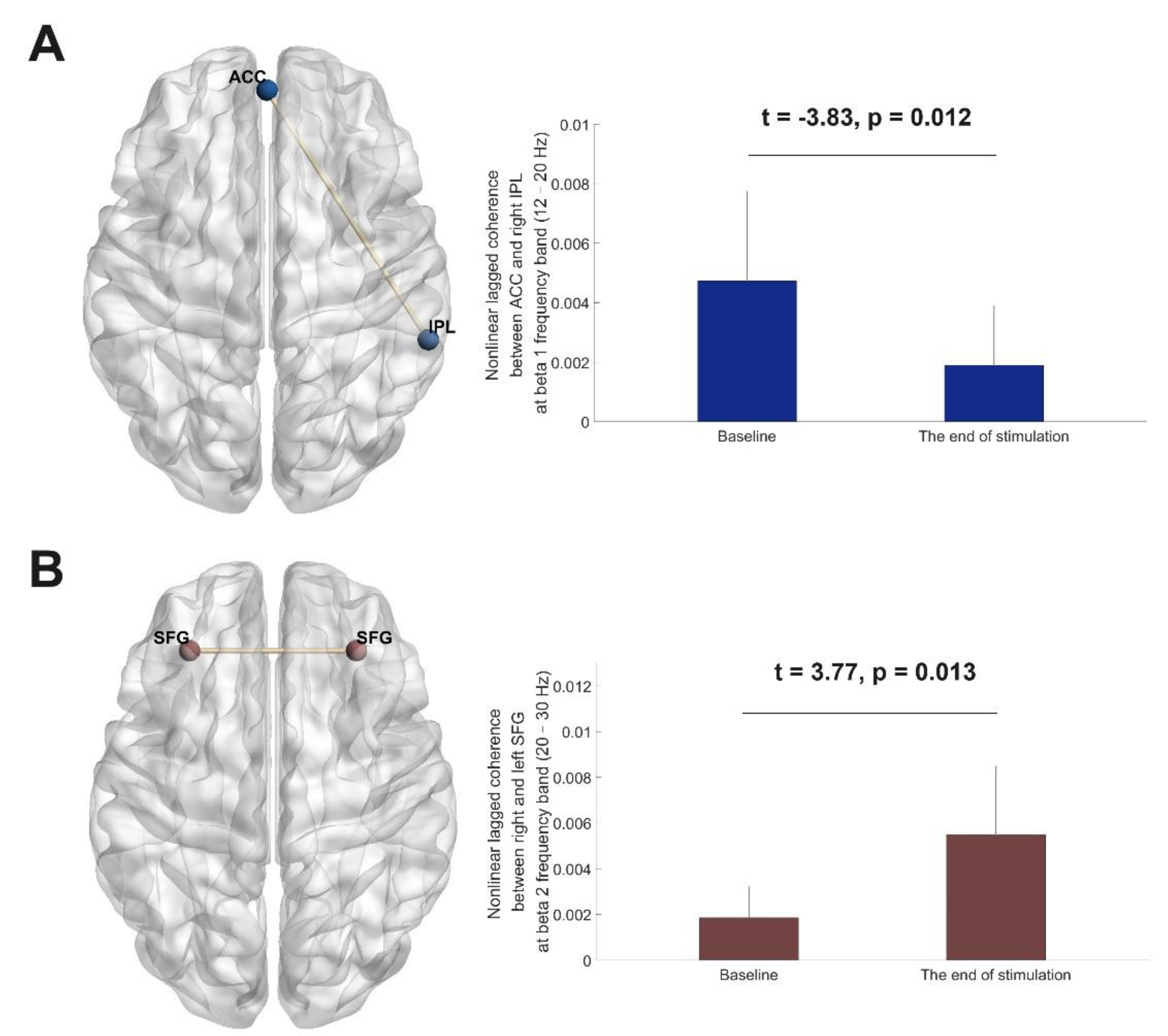

3.5. EEG Source Functional Connectivity Analyses

| Network | Anatomic structure | Side | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| data | Anterior cingulate gyrus (ACC) | Mid | 0 | 53 | 0 |

| Posterior cingulate gyrus (PCC) | Mid | 0 | -53 | 29 | |

| Inferior parietal lobule (IPL) | R | 60 | -40 | 27 | |

| Inferior parietal lobule (IPL) | L | -60 | -40 | 27 | |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus (ACC) | Mid | 0 | 41 | 0 | |

| Superior/middle frontal gyrus (SFG) | R | 31 | 36 | 38 | |

| Superior/middle frontal gyrus (SFG) | L | -31 | 36 | 38 | |

| Medial frontal gyrus (MFG) | R | 14 | 48 | -4 | |

| data | Medial frontal gyrus (MFG) | L | -14 | 48 | -4 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Ethics approval:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, S.; Fang, Y. Efficacy of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation for Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Fricke, K.; Henschke, U.; Schlitterlau, A.; Liebetanz, D.; Lang, N. , et al. Pharmacological modulation of cortical excitability shifts induced by transcranial direct current stimulation in humans. J Physiol. 2003, 553, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehatpour, P.; Dondé, C.; Hoptman, M.J.; Kreither, J.; Adair, D.; Dias, E. , et al. Network-level mechanisms underlying effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on visuomotor learning. Neuroimage. 2020, 223, 117311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanía, R.; Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Modulating functional connectivity patterns and topological functional organization of the human brain with transcranial direct current stimulation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011, 32, 1236–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.; Hooley, J.M.; Camprodon, J.A. Transcranial direct current stimulation of default mode network parietal nodes decreases negative mind-wandering about the past. Cognit Ther Res. 2020, 44, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Cohen, L.G.; Wassermann, E.M.; Priori, A.; Lang, N.; Antal, A. , et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 2008, 1, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, B.S.; Cavendish, B.A.; da Silva, P.H.R.; Suen, P.J.C.; Marinho, K.A.P.; Valiengo, L.; et al. The Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis and Integrated Electric Fields Modeling Analysis. Biomedicines 2022, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bation, R.; Mondino, M.; Le Camus, F.; Saoud, M.; Brunelin, J. Transcranial direct current stimulation in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Eur Psychiatry. 2019, 62, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Brunoni, A.R.; Goerigk, S.; Batistuzzo, M.C.; Costa, D.; Diniz, J.B. , et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial direct current stimulation as an add-on treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021, 46, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, G.; Moradei, C.; Cecchelli, C. Will Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Improve the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Current Targets and Clinical Evidence. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, N.; Bosanac, P.; Pikoos, T.; Rossell, S.; Castle, D. Therapeutic Neurostimulation in Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzina, N.; Mallet, L.; Burguière, E.; N'Diaye, K.; Pelissolo, A. Cognitive Dysfunction in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veale, D.M.; Sahakian, B.J.; Owen, A.M.; Marks, I.M. Specific cognitive deficits in tests sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychol Med. 1996, 26, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolub, D.; Vibert, N.; Botta, F.; Razmkon, A.; Bouquet, C.; Wassouf, I. , et al. High treatment resistance is associated with lower performance in the Stroop test in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2023, 14, 1017206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbrich, H.; Jahn, I.; Stengler, K.; Seifritz, E.; Colla, M. Heart rate variability in obsessive compulsive disorder in comparison to healthy controls and as predictor of treatment response. Clin Neurophysiol. 2022, 138, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, R.; Poletti, S.; Prestifilippo, D.; Attanasio, F.; Barbini, B.; Colombo, C. Transcranial direct current stimulation: A novel approach in the treatment of vascular depression. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Yu, K.; Zhuang, W.; Zhu, H.; Xu, W. , et al. Impact of twice-a-day transcranial direct current stimulation intervention on cognitive function and motor cortex plasticity in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Gen Psychiatr. 2023, 36, e101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Amadera, J.; Berbel, B.; Volz, M.S.; Rizzerio, B.G.; Fregni, F. A systematic review on reporting and assessment of adverse effects associated with transcranial direct current stimulation. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 14, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, W.K.; Price, L.H.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Mazure, C.; Fleischmann, R.L.; Hill, C.L.; The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I.; et al. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989, 46, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmerswaal, K.C.P.; Batelaan, N.M.; Hoogendoorn, A.W.; van der Wee, N.J.A.; van Oppen, P.; van Balkom, A. Four-year course of quality of life and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, M.; D'Elia, L.; Satz, P.; Janssen, R.; Zaudig, M.; Uchiyama, C. , et al. Evaluation of two new neuropsychological tests designed to minimize cultural bias in the assessment of HIV-1 seropositive persons: a WHO study. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1993, 8, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpina, F.; Tagini, S. The Stroop Color and Word Test. Front Psychol. 2017, 8, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Luengo, B.; González-Andrade, A.; García-Cobo, M. Not All Differences between Patients with Schizophrenia and Healthy Subjects Are Pathological: Performance on the Conners' Continuous Performance Test. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Alba, J.; Esteba-Castillo, S.; Castellanos López, M.; Janssen, R.; Zaudig, M.; Uchiyama, C. , et al. Validation and Normalization of the Tower of London-Drexel University Test 2nd Edition in an Adult Population with Intellectual Disability. Span J Psychol. 2017, 20, E32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods. 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Hsu, S.H.; Pion-Tonachini, L.; Jung, T.P. Evaluation of Artifact Subspace Reconstruction for Automatic Artifact Components Removal in Multi-Channel EEG Recordings. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2020, 67, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pion-Tonachini, L.; Kreutz-Delgado, K.; Makeig, S. ICLabel: An automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. Neuroimage. 2019, 198, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Marqui, R.D.; Lehmann, D.; Koukkou, M.; Kochi, K.; Anderer, P.; Saletu, B. , et al. Assessing interactions in the brain with exact low-resolution electromagnetic tomography. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2011, 369, 3768–3784. [Google Scholar]

- Olbrich, S.; Olbrich, H.; Adamaszek, M.; Jahn, I.; Hegerl, U.; Stengler, K. Altered EEG lagged coherence during rest in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 2421–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Axmacher, N. The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011, 12, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bation, R.; Poulet, E.; Haesebaert, F.; Saoud, M.; Brunelin, J. Transcranial direct current stimulation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: An open-label pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016, 65, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugarman, M.A.; Kirsch, I.; Huppert, J.D. Obsessive-compulsive disorder has a reduced placebo (and antidepressant) response compared to other anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017, 218, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senço, N.M.; Huang, Y.; D'Urso, G.; Parra, L.C.; Bikson, M.; Mantovani, A. , et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: emerging clinical evidence and considerations for optimal montage of electrodes. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2015, 12, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szechtman, H.; Woody, E. Obsessive-compulsive disorder as a disturbance of security motivation. Psychol Rev. 2004, 111, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhong, M.; Gan, J.; Liu, W.; Niu, C.; Liao, H. , et al. Altered connectivity within and between the default mode, central executive, and salience networks in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2017, 223, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.; Reeß, T.J.; Rus, O.G.; Gürsel, D.A.; Wagner, G.; Berberich, G. , et al. Increased Default Mode Network Connectivity in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder During Reward Processing. Front Psychiatry. 2018, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, T.P.; Gong, Z.; Ivanova, M.; Fedele, T.; Nikulin, V.; Herrojo Ruiz, M. Anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex oscillations underlie learning alterations in trait anxiety in humans. Commun Biol. 2023, 6, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, O.M.; Kale, E.; Çiçek, M. Default Mode Network Connectivity Differences in Obsessive-compulsive Disorder. Activitas Nervosa Superior. 2012, 54, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boedhoe, P.S.W.; Schmaal, L.; Abe, Y.; Alonso, P.; Ameis, S.H.; Anticevic, A. , et al. Cortical Abnormalities Associated With Pediatric and Adult Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Findings From the ENIGMA Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Working Group. Am J Psychiatry. 2018, 175, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Yang, Z.; Robbins, T.W. , et al. Pathological Networking of Gray Matter Dendritic Density With Classic Brain Morphometries in OCD. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, e2343208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, K.; Aardema, F. Fusion or confusion in obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychol Rep. 2003, 93, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Urso, G.; Brunoni, A.R.; Mazzaferro, M.P.; Anastasia, A.; de Bartolomeis, A.; Mantovani, A. Transcranial direct current stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized, controlled, partial crossover trial. Depress Anxiety. 2016, 33, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harika-Germaneau, G.; Heit, D.; Chatard, A.; Thirioux, B.; Langbour, N.; Jaafari, N. Treating refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder with transcranial direct current stimulation: An open label study. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, S.M.; Narayanaswamy, J.C.; Hazari, N.; Bose, A.; Chhabra, H.; Balachander, S. , et al. Efficacy of pre-supplementary motor area transcranial direct current stimulation for treatment resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: A randomized, double blinded, sham controlled trial. Brain Stimul. 2019, 12, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardolino, G.; Bossi, B.; Barbieri, S.; Priori, A. Non-synaptic mechanisms underlie the after-effects of cathodal transcutaneous direct current stimulation of the human brain. J Physiol. 2005, 568, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | cerebellum-OFC tDCS | pre-SMA tDCS | OFC-pre-SMA tDCS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| Females (%) | 2(33.30%) | 1(16.70%) | 2(33.30%) | 0.76 |

| Age, years | 37.67±11.84 | 35.83±13.32 | 30.67±9.20 | 0.57 |

| Education level, years | 15.00±1.10 | 14.83±2.04 | 15.33±3.72 | 0.94 |

| Handedness(right-left) | 0/6 | 2/4 | 0/6 | 0.11 |

| Length of illness, years | 18.67±12.47 | 16.17±11.20 | 13.83±7.19 | 0.73 |

| Current pharmacological treatment | 0.55 | |||

| Monotherapy with SSRI or clomipramine, or combination of SSRI and clomipramine | 2 (33.30%) | 2 (33.30%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| SSRI or clomipramine | ||||

| augmented with an antipsychotic | 2 (33.30%) | 4 (66.70%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Combination of SSRI and SNRI | 1 (16.70%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Combination of SSRI and NDRI | 1 (16.70%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Y-BOCS | 31.67±5.47 | 28.67±6.74 | 26.00±4.52 | 0.25 |

| OCD-VAS | 2.62±2.06 | 3.67±1.51 | 2.58±1.02 | 0.43 |

| HAMD | 10.67±7.45 | 9.00±5.10 | 7.00±4.38 | 0.56 |

| HAMA | 10.67±6.41 | 8.00±4.43 | 11.67±8.57 | 0.63 |

| WHOQOL-BREF | ||||

| Physical health | 18.83±2.64 | 18.17±2.99 | 17.17±3.31 | 0.63 |

| Psychology | 17.00±2.19 | 14.83±2.23 | 13.83±2.48 | 0.08 |

| Social relationships | 10.67±1.37 | 10.17±1.33 | 9.67±3.88 | 0.79 |

| Environment | 28.17±2.04 | 30.00±4.98 | 28.33±6.80 | 0.79 |

| TOL accuracy | 4.50±1.87 | 3.17±2.64 | 2.83±1.33 | 0.35 |

| TOL time | 233.17±52.97 | 240.67±77.59 | 233.67±88.17 | 0.98 |

| TOL score | 1.00±1.67 | 0.33±0.52 | 0.50±0.55 | 0.54 |

| DSST | 2.50±2.17 | 3.17±4.26 | 1.50±2.74 | 0.51 |

| CTT Color 1 time | 45.64±11.30 | 38.61±14.50 | 40.41±9.23 | 0.58 |

| CTT Color 2 time | 97.49±40.00 | 91.88±22.05 | 80.52±15.14 | 0.57 |

| CPT-II HRT | 434.70±56.06 | 401.84±68.95 | 383.78±78.38 | 0.45 |

| CPT-II Var | 11.56±11.77 | 8.12±6.37 | 6.82±2.26 | 0.57 |

| CPT-II d’ | 0.55±0.25 | 0.49±0.39 | 0.58±0.52 | 0.92 |

| SCWT Naming interference tendency | 0.16±0.15 | 0.44±0.34 | 0.31±0.35 | 0.28 |

| SCWT Reading interference tendency | 0.22±0.15 | 0.44±0.5 | 0.12±0.05 | 0.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).