1. Introduction

Currently, the most prominent example of a fluctuation-induced force is the force due to quantum or thermal fluctuations of the electromagnetic field, leading to the so-called QED Casimir effect, named after the Dutch physicist H.B. Casimir who first realized that in the case of two perfectly-conducting, uncharged, and smooth plates parallel to each other in vacuum, at

these fluctuations lead to an

attractive force between them [

1]. Thirty years after Casimir, Fisher and De Gennes [

2] showed that a very similar effect exists in critical fluids, today known as critical Casimir effect. A summary of the results available for this effect can be found in the recent reviews [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The description of the critical Casimir effect is based on finite-size scaling theory [

7,

8,

9]. Let us envisage a system with a film geometry

,

, and with boundary conditions

imposed along the spatial direction of finite extent

L. Take

to be the total free energy of such a system within the grand canonical ensemble (GCE). Then, if

is the free energy per area

A of the system, one can define the Casimir force for critical systems in the grand-canonical

-ensemble, see, e.g. Refs. [

4,

9,

10,

11]::

where

is the so-called excess (over the bulk) free energy per area and per

. Here we suppose a system at temperature

T is exposed to an external ordering field

h, which couples linearly to its order parameter

—such as the number density, the concentration difference, the magnetization etc. Actually, the thermodynamic Casimir force

per area is the excess pressure over the bulk one due to the finite size

of that system:

Here

is the pressure in the finite system under boundary conditions

, while

is the one in the infinite, i.e., macroscopically large, system. The above definition is actually equivalent to Eq. (1.1). Note that

is the excess grand potential per area,

is the grand canonical potential per area of the finite system, while

has the meaning of the grand potential per volume

V for the macroscopically large system. The equivalence between the definitions in Eqs. (1.1) and (1.3) stems from the observation that for the finite system one has

, while for the bulk one and

.

When the excess pressure is inward towards the system, i.e., there is an attraction of the surfaces of the system towards each other and a repulsion if .

2. The Casimir Force Within the Continuum Gaussian Model

The continuum version of the Gaussian model with a scalar order parameter consists of the linear and bilinear terms in the Ginzburg-Landau-Wilson formulation of a system in

d dimensions that undergoes a continuous symmetry-breaking phase transition at low temperatures. The partition function of this system is the functional integral

where

In (2.2)

t is the reduced temperature, proportional to

, and

h is the spatially constant ordering field. Because of the Gaussian nature of the free energy functional

the partition function resolves into the product

where

is the partition function of the system with

. The geometry of the system under consideration is a slab of large—ultimately infinite—cross section and finite thickness

L.

With regard to scaling considerations, there are two combinations of parameters that reflect the predictions of finite size scaling. They are

where

, the correlation length exponent, is equal to 1/2 in the Gaussian model, and as noted above

d is the dimensionality of the system. Our end results for the Casimir forces acting upon the systems will depend on the boundary conditions imposed. In all cases, the form of the Casimir force is

All results reported in this portion of the article rely on two results, which can be obtained with the use of contour integration techniques; see also [

12]. The two results are

In order to carry out the evaluation of the free energy of the Gaussian model we turn to the basis set of functions that will be used to construct the free energy with and without an ordering field. These functions allow us to evaluate the partition function by integrating over the amplitudes of the contributions of each member of the set to the order parameter. Here, we focus on the case of periodic boundary conditions. Ignoring the dependence on position in the “plane” of the slab, the functions are the orthonormal set

with

n a positive integer. It is straightforward to show that this set is orthonormal as a function of

z in that

The three function types are all mutually orthogonal. In the case of higher dimensions, we construct a new basis set by multiplying the functions (2.9)–(2.11) by suitable functions of the orthogonal position variables. Those functions can be taken to be of the form

, where

is a

-dimensional position vector in the plane of the slab and

is in its reciprocal space.

We then express the order parameter as follows

The free energy for a given configuration of the Gaussian order parameter, in terms of the amplitudes in the expansion of the order parameter in the basis set (2.12)–(2.14), is

The last term in brackets above reflects the fact that the only basis function that the constant external field couples to is the constant function in (2.11)

The next step is to exponentiate the expression in (2.16), multiply by either

, or setting

, by -1, and, after that, to perform the Gaussian integrals over the

’s, the

’s, and

. The resulting partition function is given by

The coefficient

A in (2.17) is the

dimensional area of the slab.

As our next step we evaluate the sum over

n on the right hand side of the expression for the partition function. To achieve this, we take the

t-derivative of the logarithm of the summand, perform the sum over

n and then integrate the resulting expression with respect to

t. Taking the derivative of the summand in (2.17) with respect to

t leaves us with the sum

which follows from (2.7). This integrates up to

The large-

L limit of (2.19) is

To find the contribution to the Casimir force per unit area, we take the

L-derivative of the difference between (2.20) and (2.19) and then integrate over

. The derivative yields

The sum over values of

is expressible as an integral, which takes the form

where, to get to the last line of (2.22) we defined a new integration variable

and then made use of the definition (2.4) of

. The implication of (2.22) is that we can express the

contribution to the Casimir force as

times a function of the scaling temperature variable

. The coefficient

in the equations above is the geometric factor

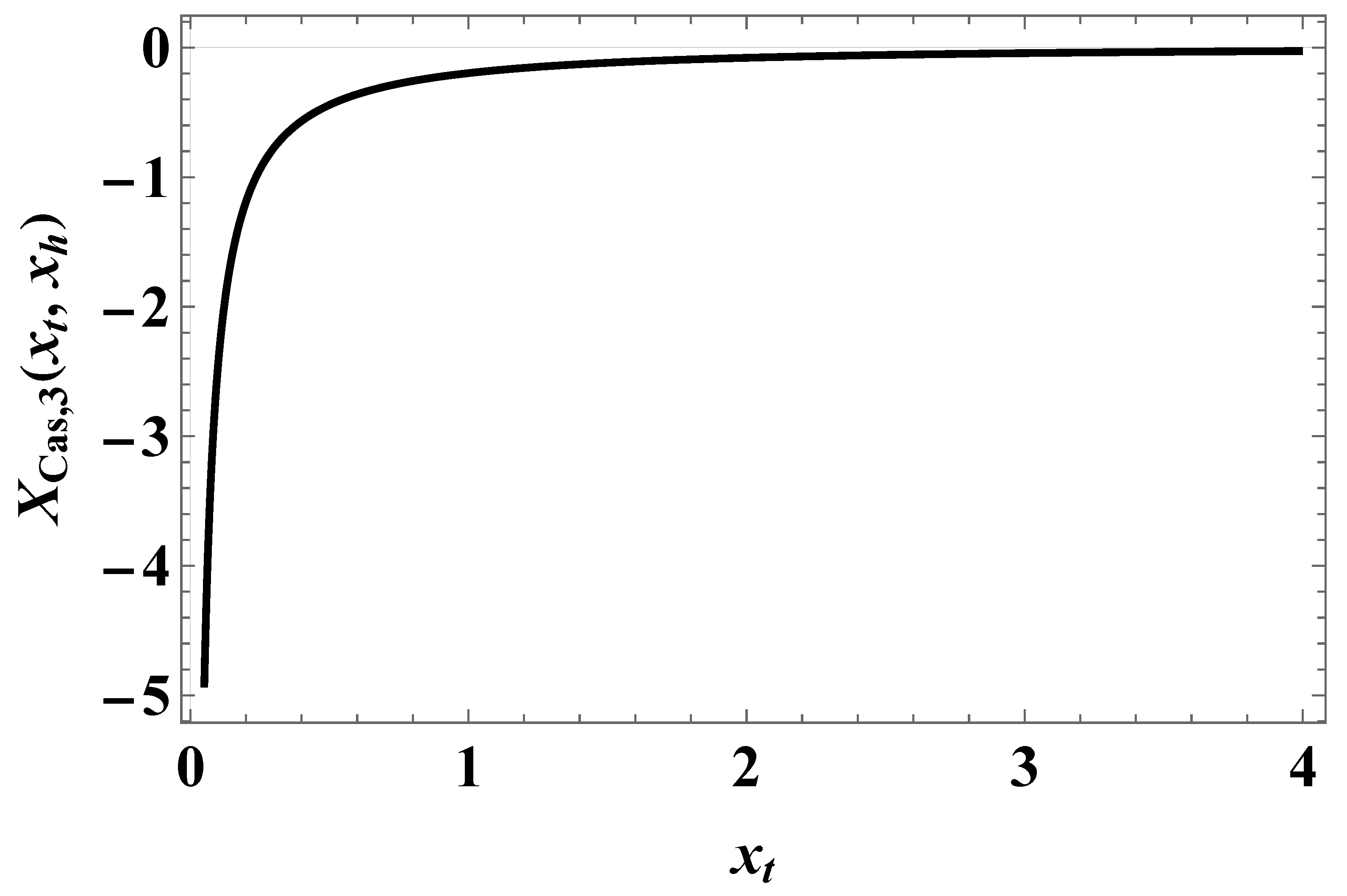

In the case of three dimensions, further processing of the result (2.22) is possible. We find

where

is the polylogarithm function; see [

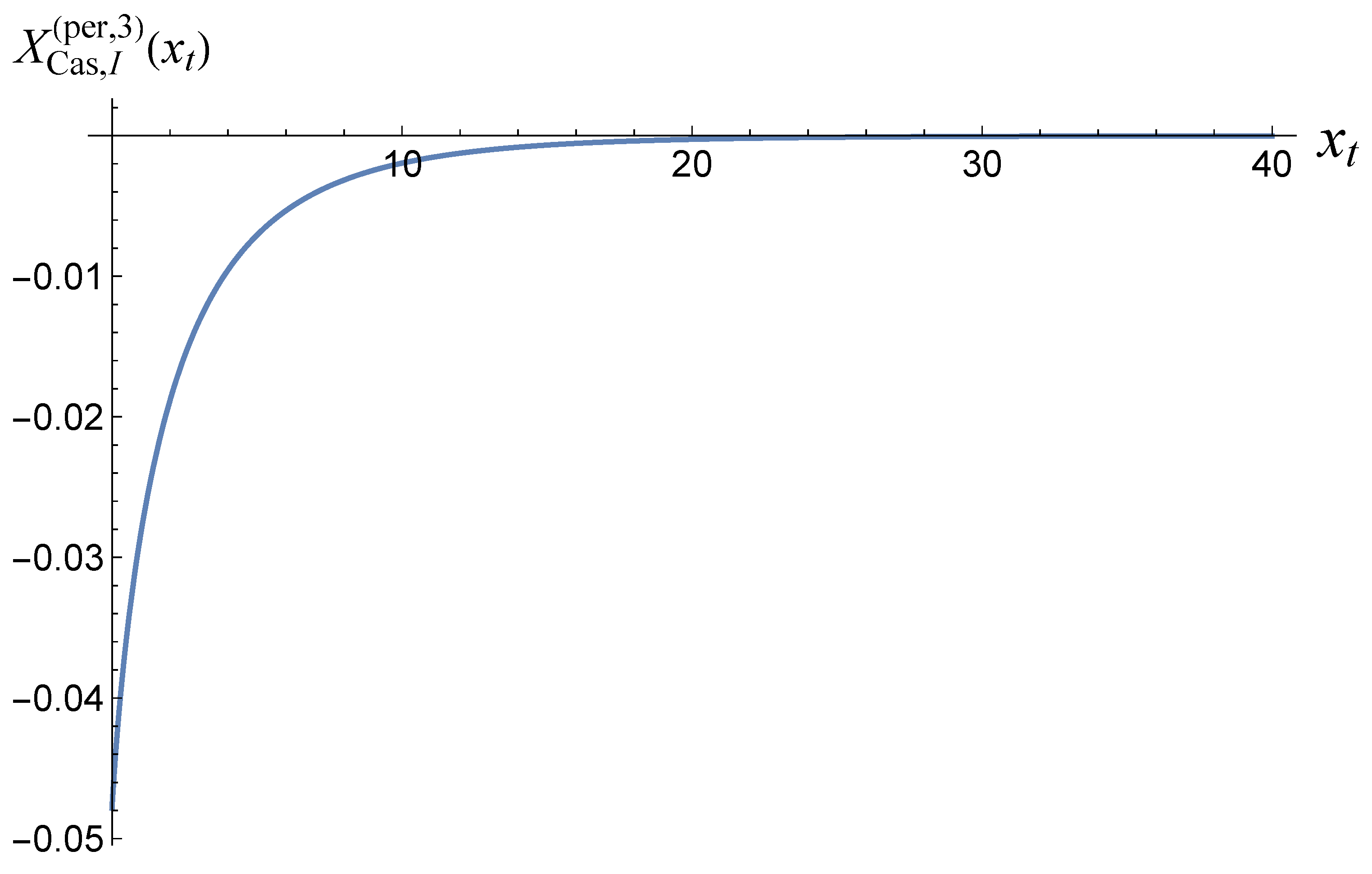

13]. A plot of the function

is shown in

Figure 1.

The first term in parentheses in Eq. (2.17) gives us the h-dependent contribution to the free energy: . This is to be compared to the corresponding free energy of a neighboring bulk phase, which goes as , where is an extent that will ultimately be taken to go to infinity. If you add the two free energies, the dependence on L, the thickness of the slab, disappears. This means that there is no h-dependent free energy when slab boundary conditions are periodic, and hence no h-dependent contribution to the Casimir force.

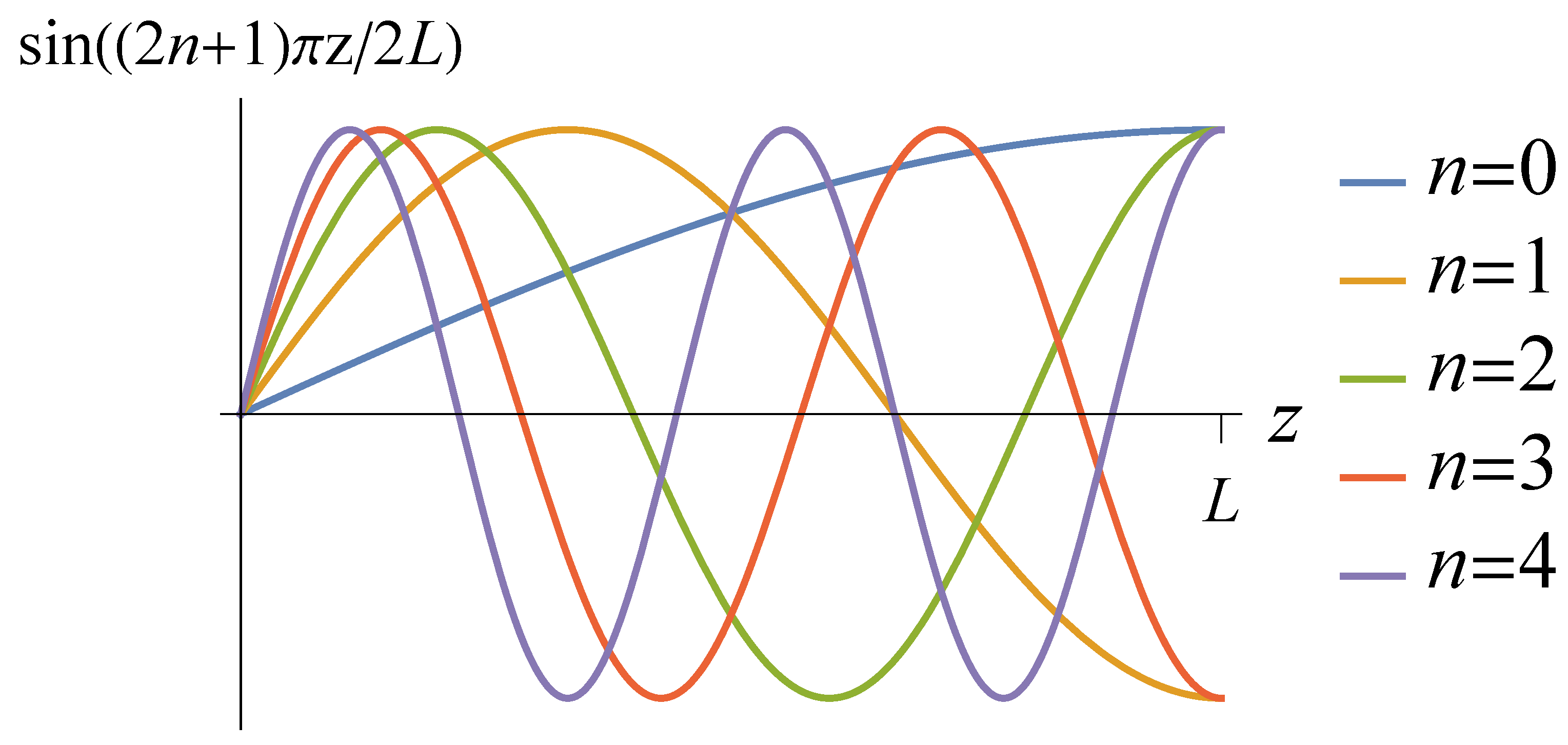

The calculations in the case of periodic boundary conditions point the way to evaluating the partition function and the Casimir force of the case of Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions.

In this case the (unnormalized) basis functions are, exclusive of their dependence on the in-plane coordinates,

Examples of these functions are shown in

Figure 2. Focusing on the

h-independent contribution to the partition function, the sum to perform in this case is (see (2.28))

Note that in the limit of large

L the right hand side goes to the expected asymptotic form. If we subtract that limiting form, and integrate with respect to

t, we are left with

Finally, we take minus the derivative of this with respect to

L, leaving us with

Making use of the analysis of previous sections, this leaves us with the following result for the Casimir force in the case of the

d-dimensional Gaussian model with Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions

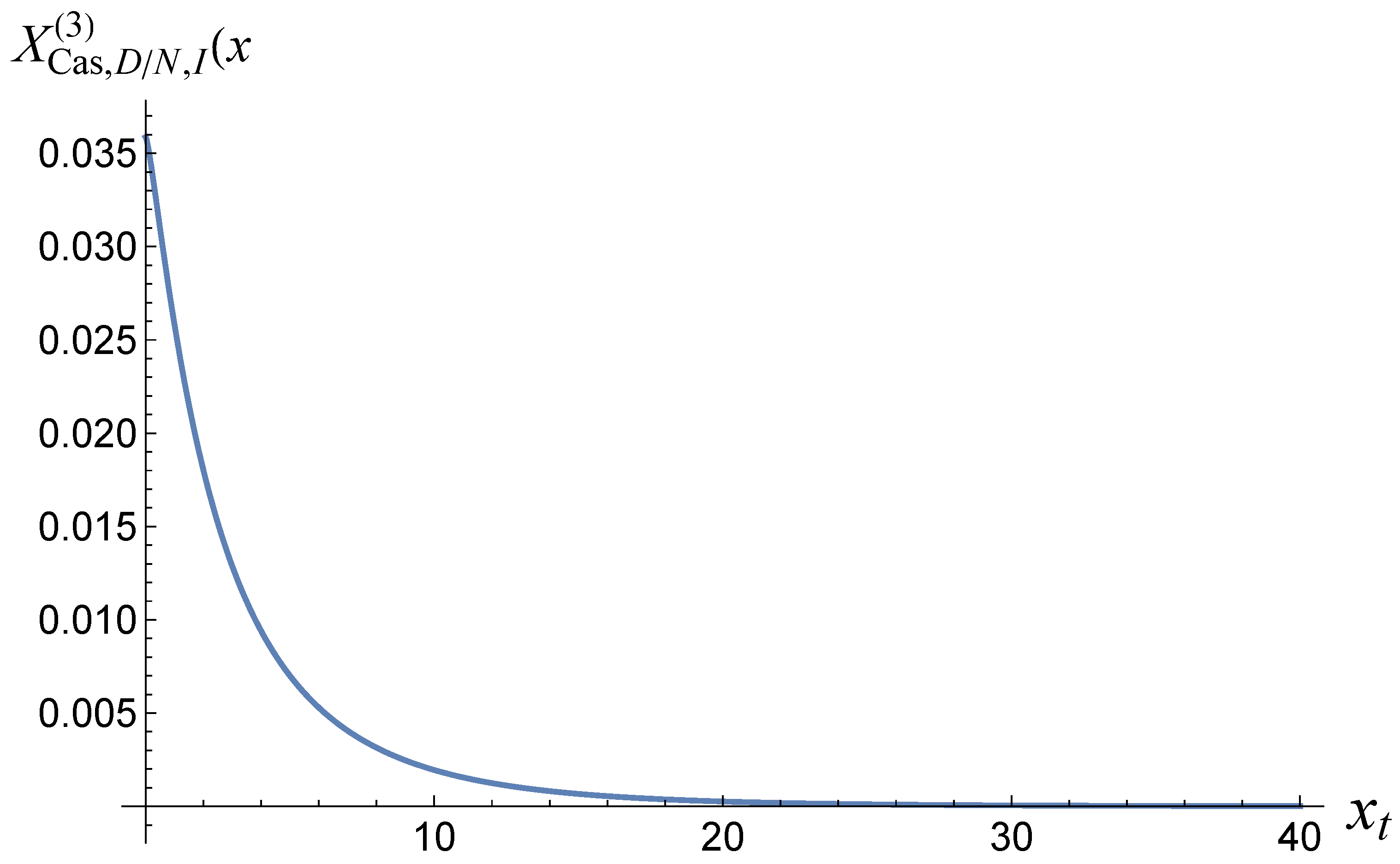

When

, we have

Figure 3 shows what the function

looks like when

.

In order to find the

h-dependent contribution to the Casimir force we turn to the normalized the basis set in the case of Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions. Assuming that the boundary conditions are Dirichlet at

and Neumann at

, this basis set is

with

n an integer and

It is straightforward to establish that

while

As it turns out there is no need to take into account any dependence of the basis set on coordinates in the plane of the slab. This is because a constant ordering field couples only to order parameter configurations that are independent of those coordinates.

With this in mind, we expand the order parameter as follows

The Gaussian integrations over the

’s leaves us with the summation over

n for the

h-dependent contribution to the partition function

where the evaluation of the sum over

n in (2.36) is accomplished with the use of (2.8) and a partial fraction decomposition of the summand. The first term in parentheses on the last line of (2.36) gives us exactly the same expression as the

h-dependent contribution to the partition function of the slab with periodic boundary conditions. Its influence on the Casimir force is exactly canceled by the influence of the bulk. What remains is

where we have made use of the definition of the scaling combination

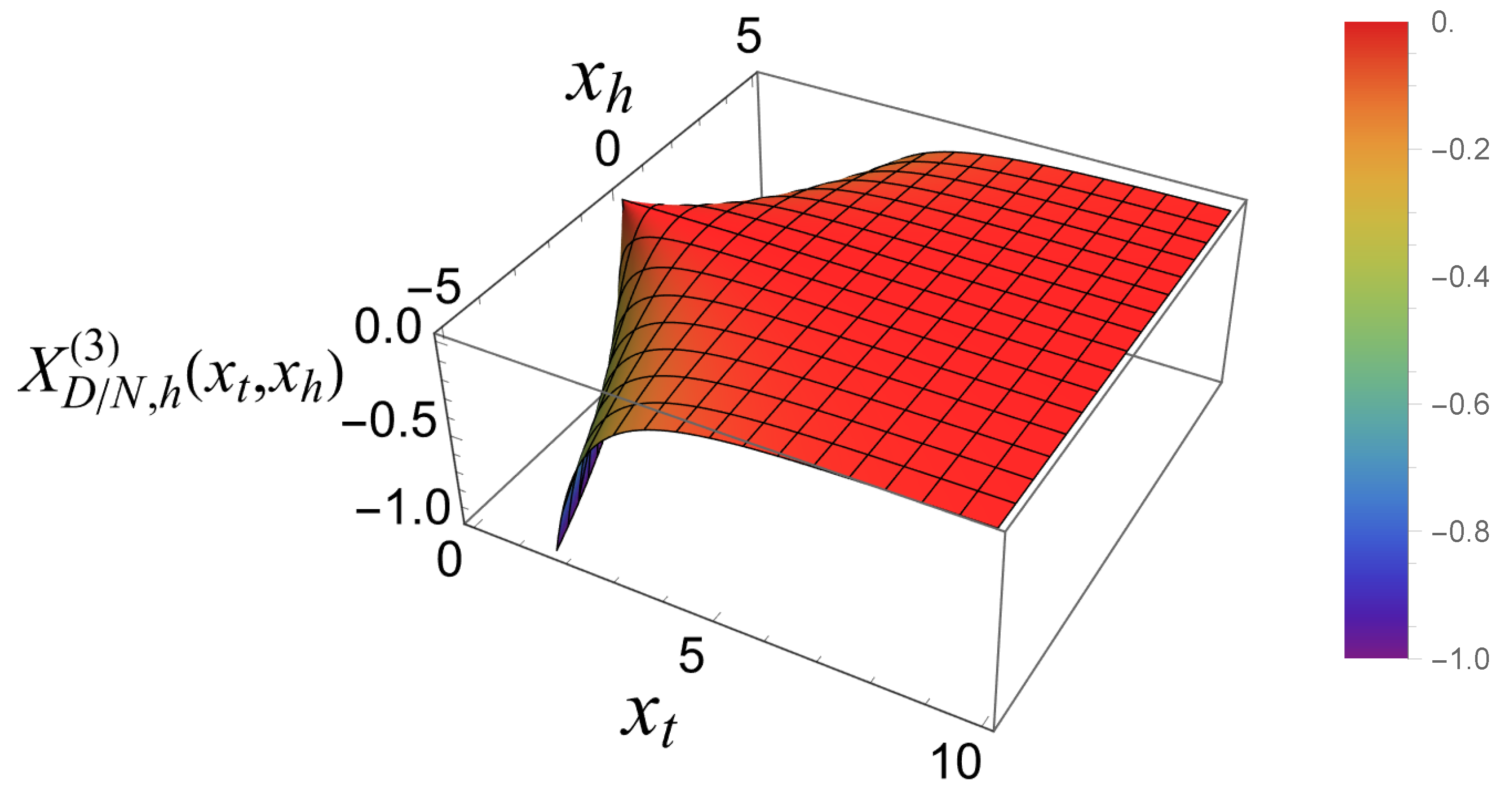

in (2.5). The scaling form of the contribution to the Casimir force is, then

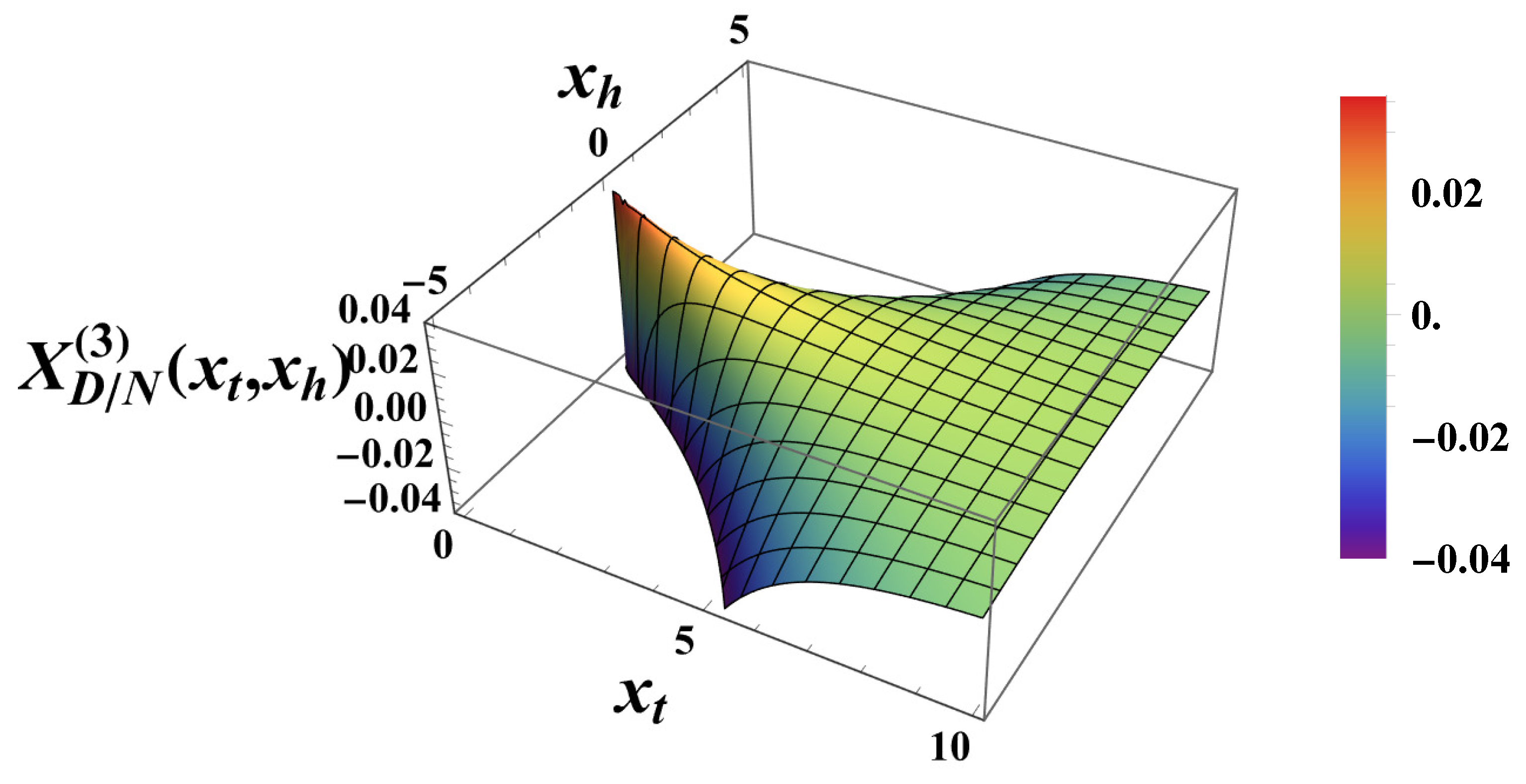

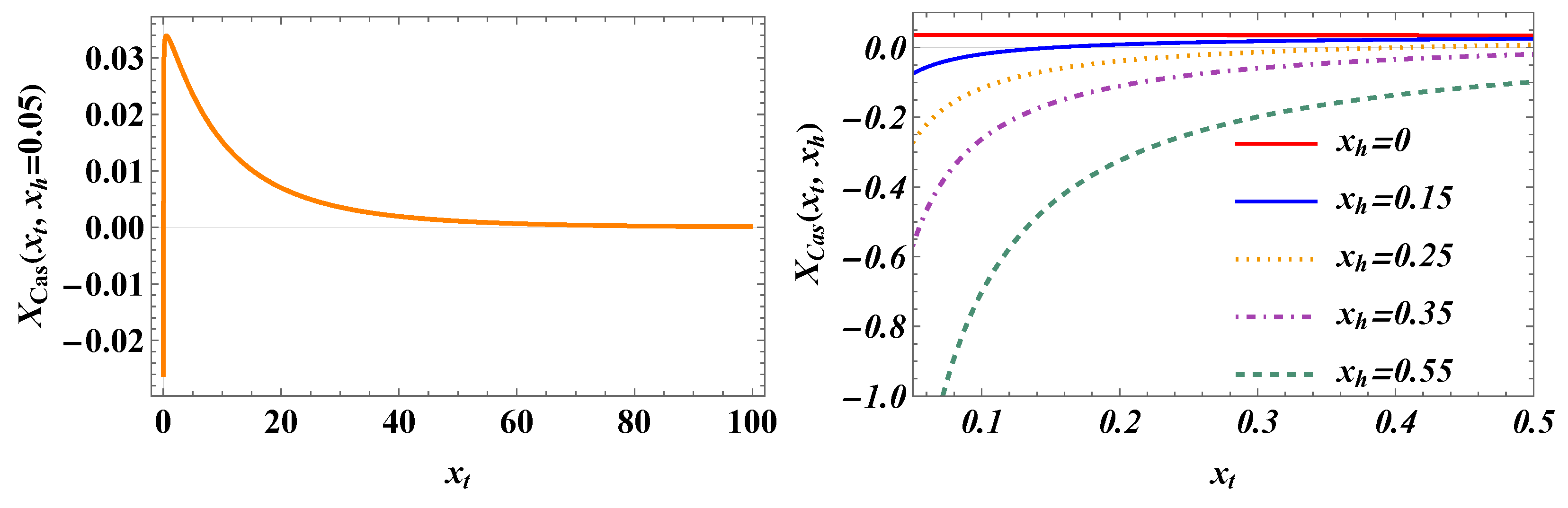

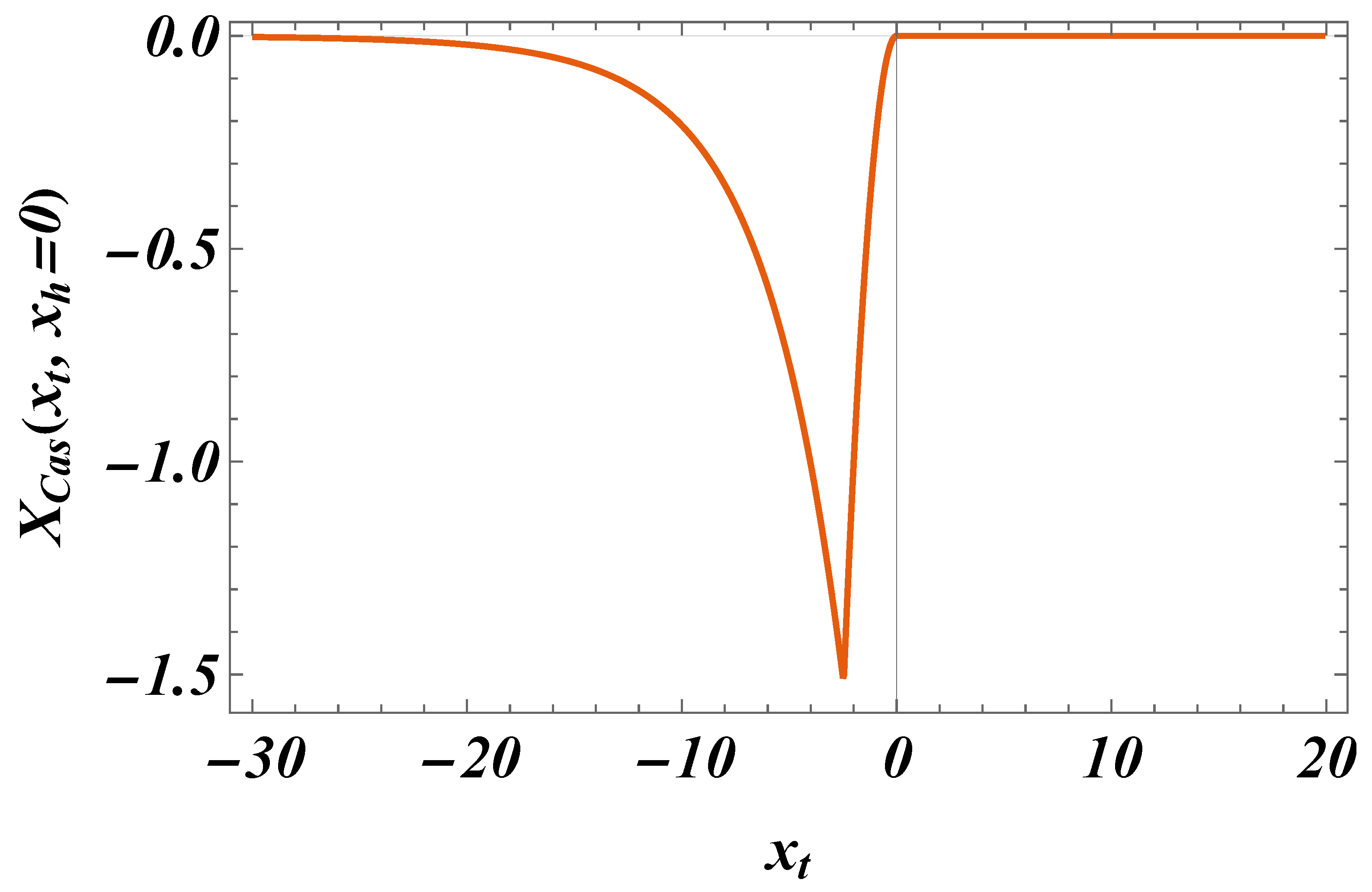

This function is shown in

Figure 4. Note that this function is

aways attractive.

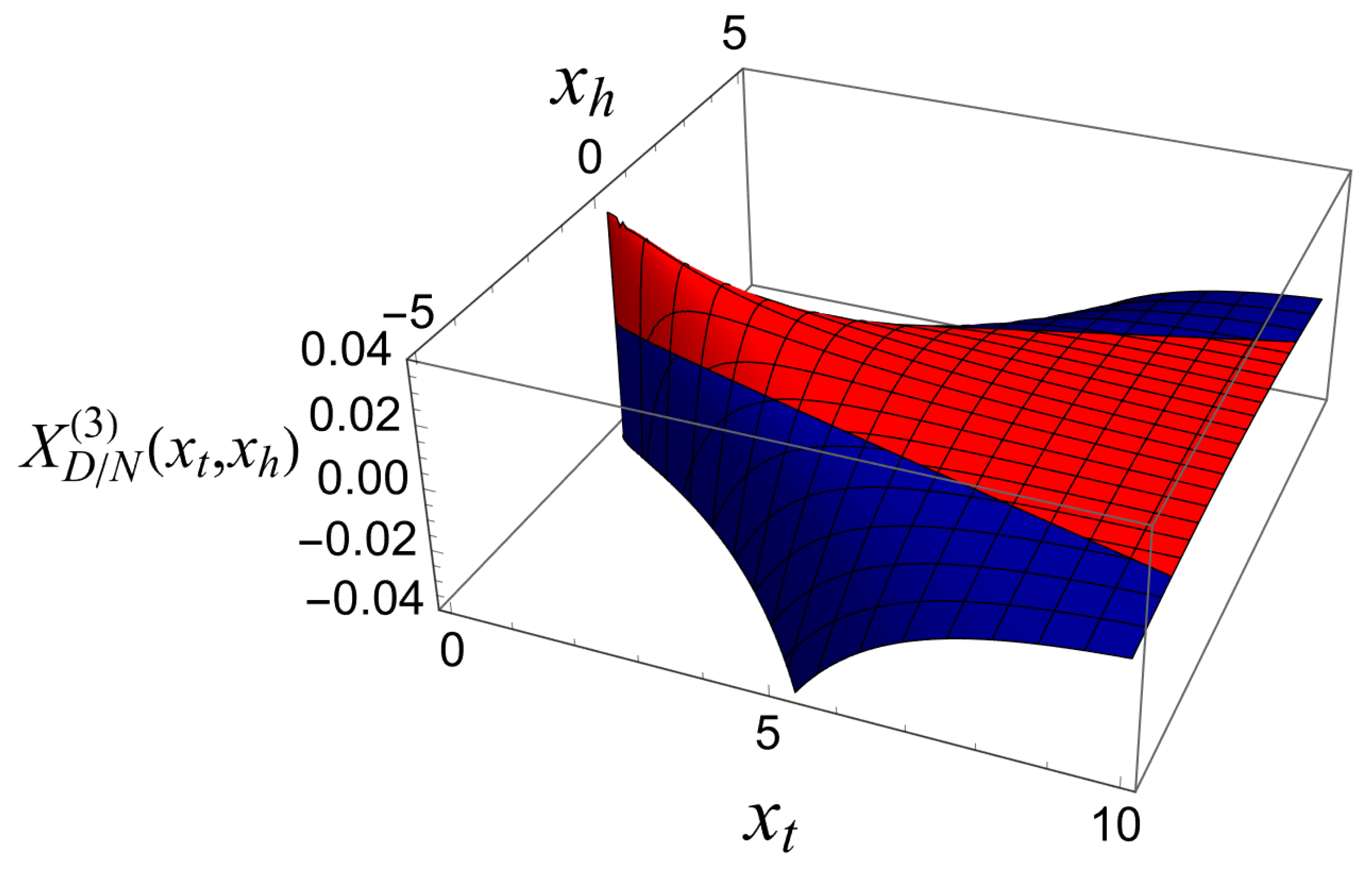

The total scaling function

is given by

Figure 5 shows what this function looks like.

Another depiction of the scaling contribution to the Casimir force for Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions in the three dimensional Gaussian model with a scalar order paremeter,

,

Figure 6, highlights the regions in which the function is attractive and repulsive.

3. The Casimir Force Within the Lattice Gaussian Model

We consider a ferromagnetic model with nearest-neighbor interactions on a fully finite d-dimensional hypercubic lattice of sites. Let us take to be the parallelepiped , where × denotes the direct (Cartesian) product of the finite sets .

It is convenient to consider the configuration space

as an Euclidean vector space in which each configuration is represented by a column-vector

with components labeled according to the lexicographic order of the set

. Let

be the corresponding transposed row-vector and let the dot (·) denote matrix multiplication. Then, for given boundary conditions

, specified for each pair of opposite faces of

by some

takes the form

Here

, where

J is the interaction constant (to be set to

in the remainder), and the

interaction matrix

can be written as

where

is the one-dimentional discrete Laplacian defined on the finite chain

under boundary conditions

, and

is the

unit matrix.

By using the results of [

9], we can write down the eigenfunctions of the interaction matrix (3.2) in the form

and obtain the corresponding eigenvalues of it

Obviously,

. Note that the interaction Hamiltonian (3.1) has negative eigenvalues, which makes necessary the inclusion of a positive-definite quadratic form in the Gibbs exponent, to ensure the existence of the corresponding partition function. Thus, we consider the Hamiltonian

Here

is a column-vector representing (in units of

) the inhomogeneous magnetic field configuration acting upon the system, and let

be the transposed row-vector.

In order to ensure the existence of the partition function, all the eigenvalues

,

, of the quadratic form in

, ought to be positive. Hence, the field

must satisfy the inequality

with

defining the critical temperature of the

finite system. Since, as stated above

, it is clear that for the infinite system

The free energy density of a

finite system in a region

is

In Eq. (3.9) the first two terms do not depend on the size of the system, i.e., they are the same in both finite and infinite systems. The other two terms do depend, however on the size of the system. The function

is due to the spin-spin interaction (and will be called "interaction term"); it depends on

s, but does not depend on

h. It is equal to

and is obtained after performing the corresponding Gaussian integrals in the free energy of the finite system. The dependence of the free energy on the field variables

h is given by the "field term"

Here

denotes the projection of the magnetic field configuration

on the eigenfunction

( by

we denote the complex conjugate of

):

Defining

so, that

the above expressions can be rewritten in the form

and

Using the notations of [

9], below we give a list of the complete sets of orthonormal eigenfunctions,

,

, of the one-dimensional discrete Laplacian under the Neumann - Dirichlet (ND) boundary conditions:

periodic (p) boundary conditions

Neumann - Dirichlet (ND) boundary conditions

The quantities

,

, are defined as follows

Now we are ready to find the finite-size behavior of the Gaussian model under the Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions. According to Eq. (3.17), , i.e., one has there realization of Neumann boundary conditions, while , which corresponds to Dirichlet boundary conditions. Thus, in the envisaged one-dimensional chain one has L independent spin variables .

We start with the consideration of dimensional system. Note that:

under fully periodic (p) boundary conditions, , one has , hence .

under Neumann-Dirichlet boundary conditions along z direction, i.e., , one has , hence .

3.1. The Gaussian Model on a Lattice for the Case

We recall that for this model

and

[

9,

14].

The behavior of the interaction term

We set

and use the short-hand notation

for these boundary conditions. Then, we perform in Eq. (3.10) the limits

, keeping

fixed. For the interaction term one then obtains

where

The behavior of the interaction term in the bulk system

In accord with Eq. (3.20), one has

The behavior of the interaction term in the film system with Neumann-Dirichlet boundary conditions

Explicitly, from Eq. (3.19) one obtains

with

This sum is of the form

where

is defined as

The summations in Eq. (3.24) can be performed using [

12] the identity

With the help of the identity one derives

Obviously

. Thus, the part of the excess free energy under Neumann – Dirichlet boundary conditions that depends only on the interaction term is

Thus,

can be decomposed in the sum of

and

where

and

Let us consider the behavior of

and

in the scaling regime

Let us first start with the function

. Obviously, if

then

will be exponentially small. Thus, we need to consider the regime

. It follows that

. From Eq. (3.25) we obtain

It follows that

where we have introduced polar coordinates. In terms of them

becomes

where

R can be defined from the constraint

, i.e.,

.

Next, we deal with

. Taking into account that

is small we derive

Note that for

one has that for the

L-dependent part

of

one has

, i.e.,

is one order of magnitude

smaller that

. Because of that,

contributes only sub-leading contributions to

L-dependent part of the excess free energy and, therefore, to the Casimir force. Based on the above, we will no longer be interested in the function

.

Summarizing the above, we conclude that the excess free energy can be written in a scaling form

where

is a non-universal constants, and

is an universal scaling function,

, where

T has the meaning of the temperature of the system, and

is its bulk temperature. From Eq. (3.34), taking into account that with

one has

, we identify that

The behavior of the field term

The dependence of the free energy on the field variable is given by the "field term", given by Eq. (3.15). For a homogeneous filed h and for and boundary conditions, it is easy to obtain that

-

for

boundary conditions

and

for

boundary conditions

Thus, setting

and

, for a film geometry we arrive at

It is easy to show that

Thus, one has

Let us consider the small

k behavior of the above sum. One derives

In the limits

and

for the behavior of the field term one obtains

When

, then

, we obtain that

which indeed equals the bulk expression - see Eq. (3.40).

From Eq. (3.45) for the behavior of the susceptibility in the finite system we derive

According to the finite-size scaling theory [

9,

15]

where

and

are non-universal constants, and

is an universal scaling function,

, where

T has the meaning of the temperature of the system, and

is its bulk temperature. From Eq. (3.48), taking into account that

, we identify that

It is clear that the field term in the free energy of the finite system will be of the same order as the field term, i.e.,

if

. In order to achieve that, we define a field dependent scaling variable

In terms of it, Eq. (3.45) becomes

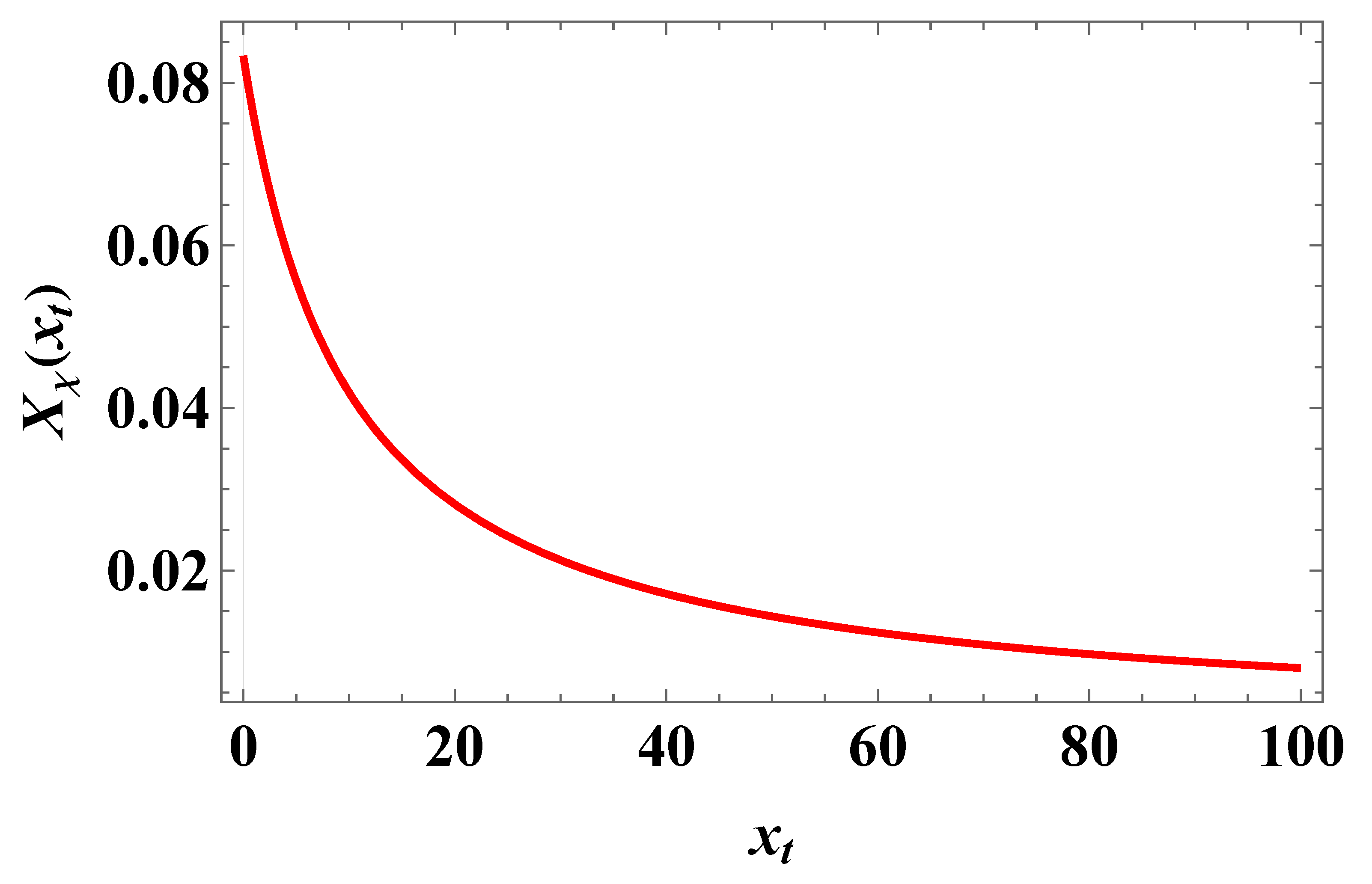

The behavior of the scaling function

is given in

Figure 7.

Then for the excess free energy related to the field term, see Eq. (3.9), one derives

3.2. The Behavior of the Casimir Force

Let us determine the contributions of the interaction term

and of the field term

. Obviously, one has

We start with determining the behavior of

. By definition, it is equal to

From Eq. (3.28) we derive the

exact expression

Here we did not make any assumption bout

L. Naturally, we will obtain a scaling form of

only for

. Then Eq. (3.32) is valid and, after performing the integration, we arrive at

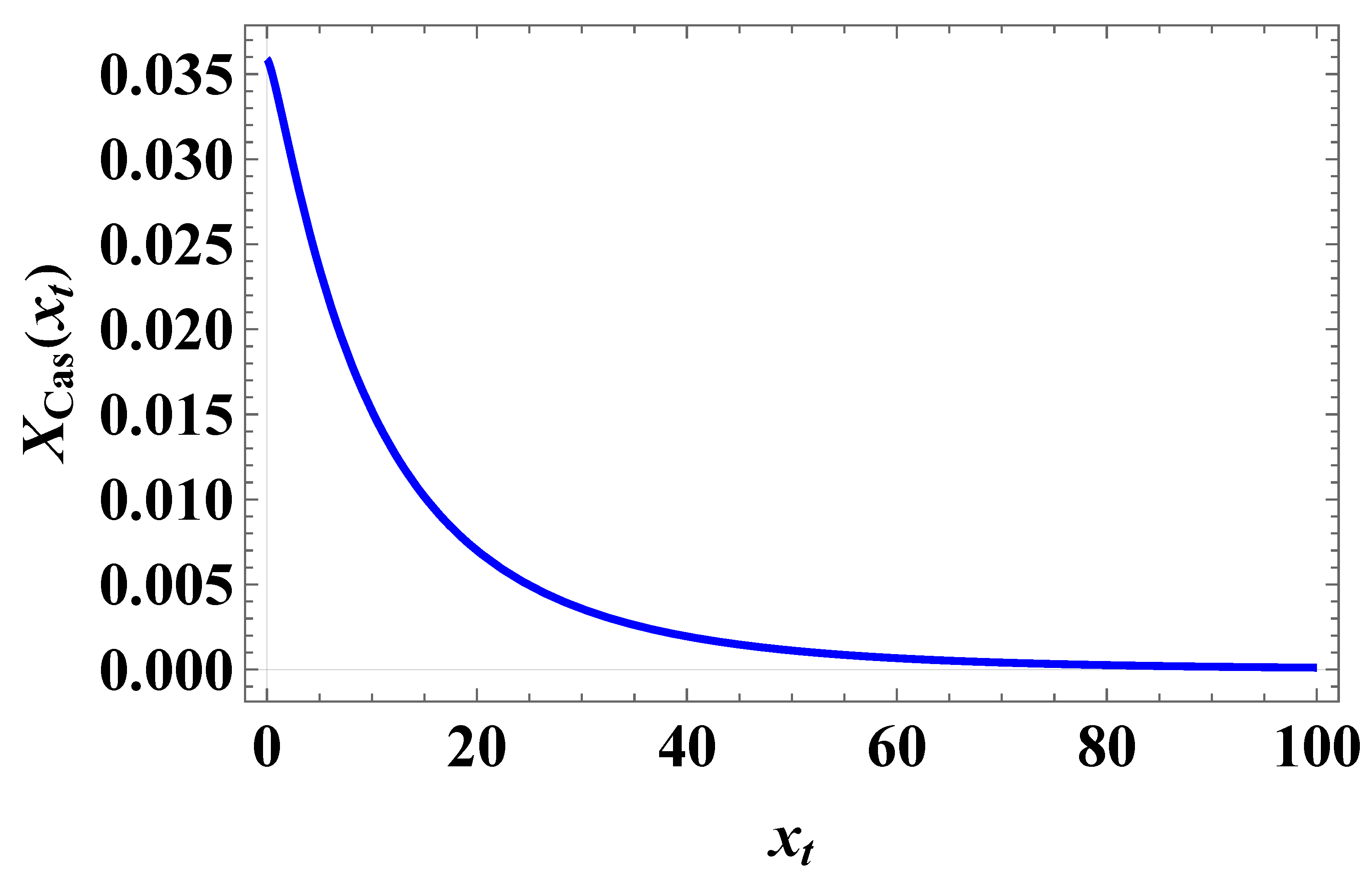

where

The behavior of the scaling function

is given in

Figure 8. Obviously, the function is positive, which means that the Casimir force is repulsive when the external field is zero. For the Casimir amplitude we obtain

Obviously, Eq. (3.59) coincides with the corresponding result for the Gaussian model obtained via studying the

,

model — see [

4, Eq.(6.99)]. Analogically, after proper renaming of the scaling variable the expression Eq. (3.58) of the scaling function of the force coinsides with the corresponding one for the

,

model — see [

4, Eq.(6.104)].

Let us now determine the

h-dependent part of the Casimir force. By definition, one has

Then, from Eq. (3.53) one obtains

where

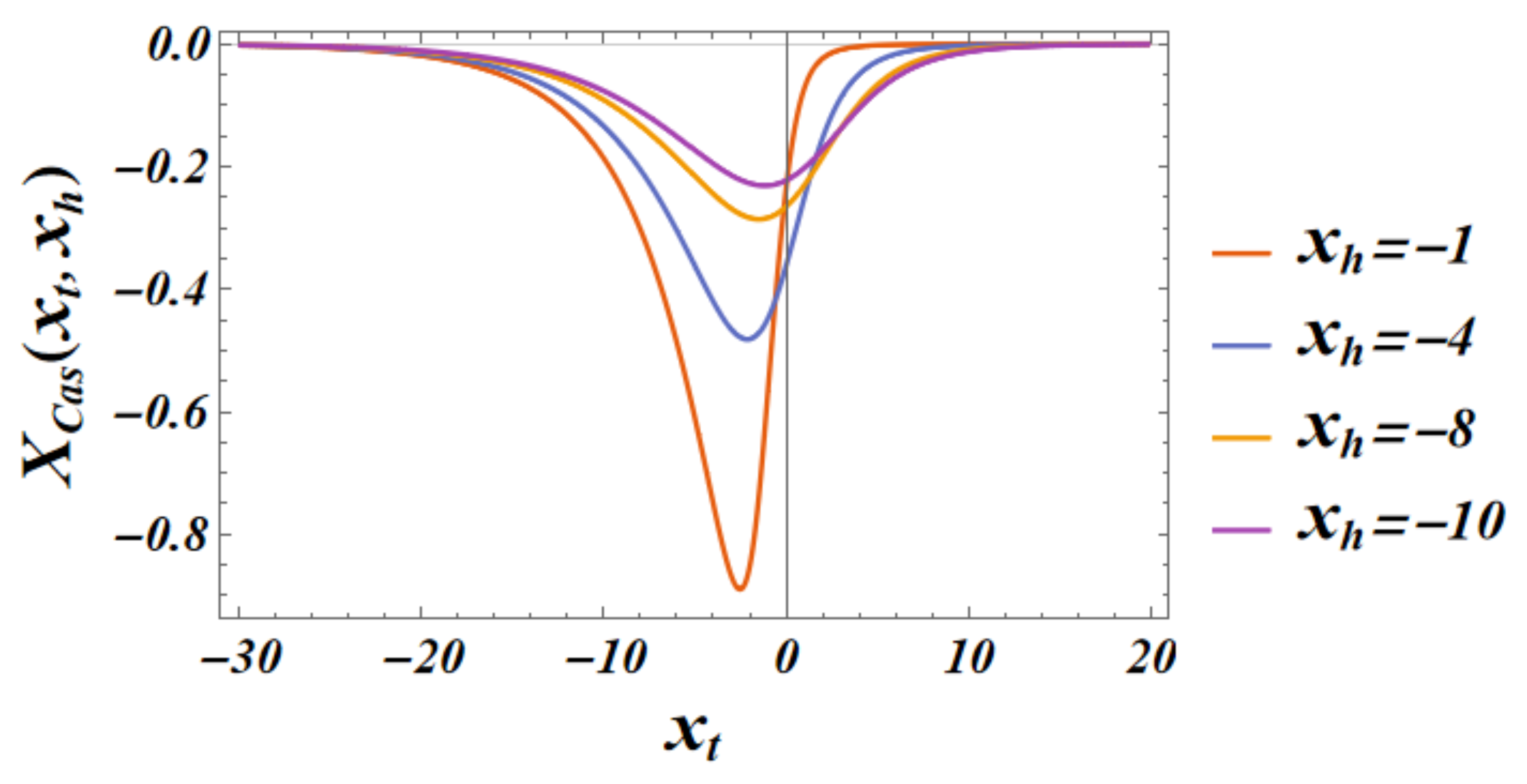

A visualization of

as a function of

y for

is shown in

Figure 9.

The total Casimir force is a sum of

, see Eq. (3.58), and

given by Eq. (3.63). The plot of the result as a function of

for

is shown in

Figure 10. As we see, the force can be both positive and negative, i.e.,

repulsive and

attractive.

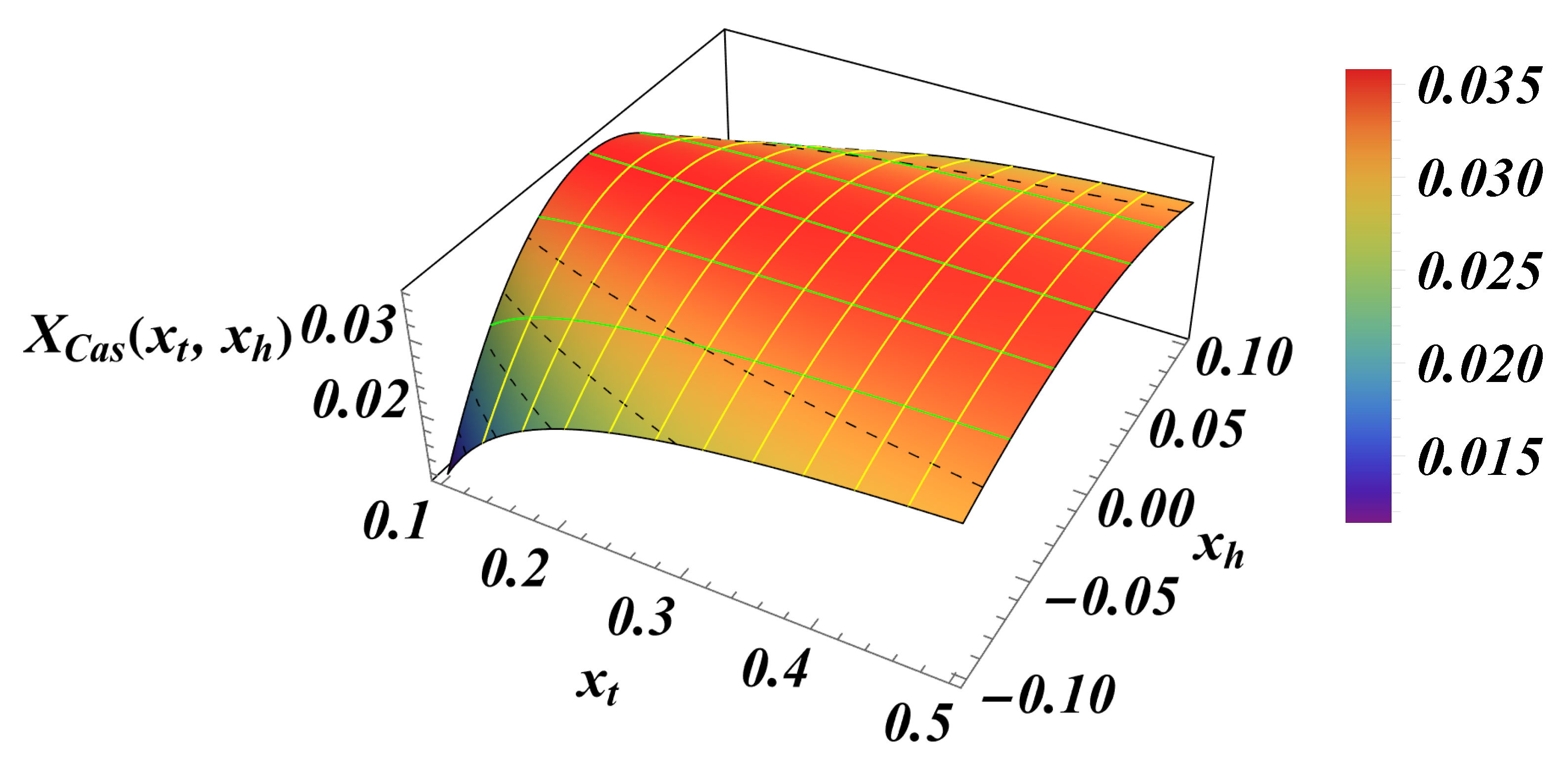

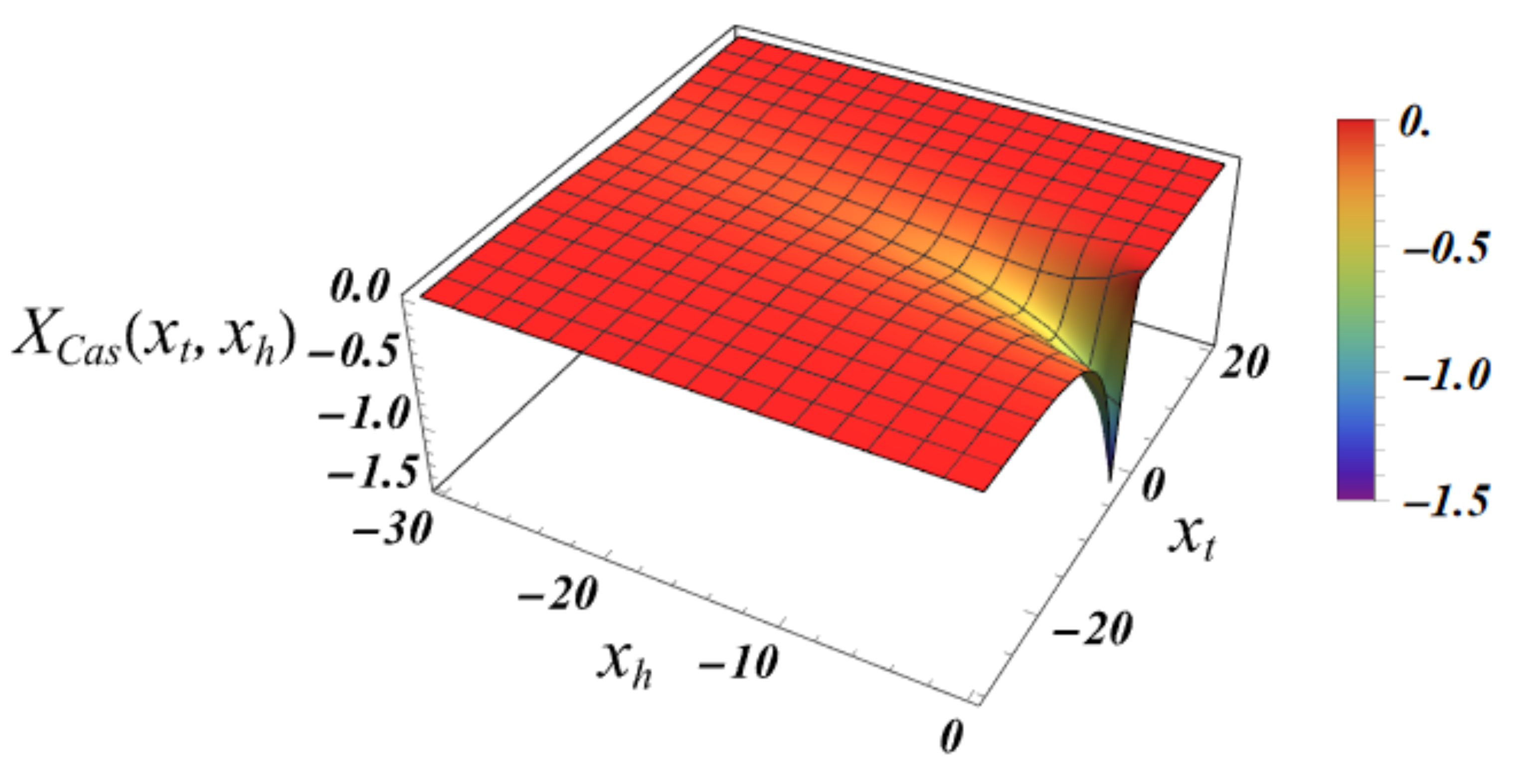

The overall

behavior of the force as a function both on

and

is given in

Figure 11.

Figure 1.

The function , plotted versus

Figure 1.

The function , plotted versus

Figure 2.

The functions in (2.25)

Figure 2.

The functions in (2.25)

Figure 3.

The function , as given in (2.30).

Figure 3.

The function , as given in (2.30).

Figure 4.

The function , as given by (2.38).

Figure 4.

The function , as given by (2.38).

Figure 5.

The total scaling contribution to the Casimir force for Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions in the three dimensional Gaussian model with a scalar order parameter,. Note that this function can be both positive (repulsive) and negative (attractive).

Figure 5.

The total scaling contribution to the Casimir force for Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions in the three dimensional Gaussian model with a scalar order parameter,. Note that this function can be both positive (repulsive) and negative (attractive).

Figure 6.

The total scaling contribution to the Casimir force for Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions in the three dimensional Gaussian model with a scalar order parameter,. The red region in the figure corresponds to a repulsive force, and the blue region corresponds to an attractive force.

Figure 6.

The total scaling contribution to the Casimir force for Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions in the three dimensional Gaussian model with a scalar order parameter,. The red region in the figure corresponds to a repulsive force, and the blue region corresponds to an attractive force.

Figure 7.

The behavior of the scaling function .

Figure 7.

The behavior of the scaling function .

Figure 8.

The behavior of the scaling function when .

Figure 8.

The behavior of the scaling function when .

Figure 9.

The behavior of the scaling function . We observe that the force is attractive.

Figure 9.

The behavior of the scaling function . We observe that the force is attractive.

Figure 10.

The behavior of the scaling function of the total Casimir force as a function of y for several values of . Left panel: We see that for the force is attractive very near the critical temperature, then becomes repulsive with increase of (i.e., of T). Right panel: It is clear, that for zero field the force is repulsive, then — for small values of — the force changes sign from attractive to repulsive with the increase of (i.e., of the temperature), while for large values of the force becomes attractive for all values of T (i.e., ).

Figure 10.

The behavior of the scaling function of the total Casimir force as a function of y for several values of . Left panel: We see that for the force is attractive very near the critical temperature, then becomes repulsive with increase of (i.e., of T). Right panel: It is clear, that for zero field the force is repulsive, then — for small values of — the force changes sign from attractive to repulsive with the increase of (i.e., of the temperature), while for large values of the force becomes attractive for all values of T (i.e., ).

Figure 11.

The behavior of the scaling function . Here and .

Figure 11.

The behavior of the scaling function . Here and .

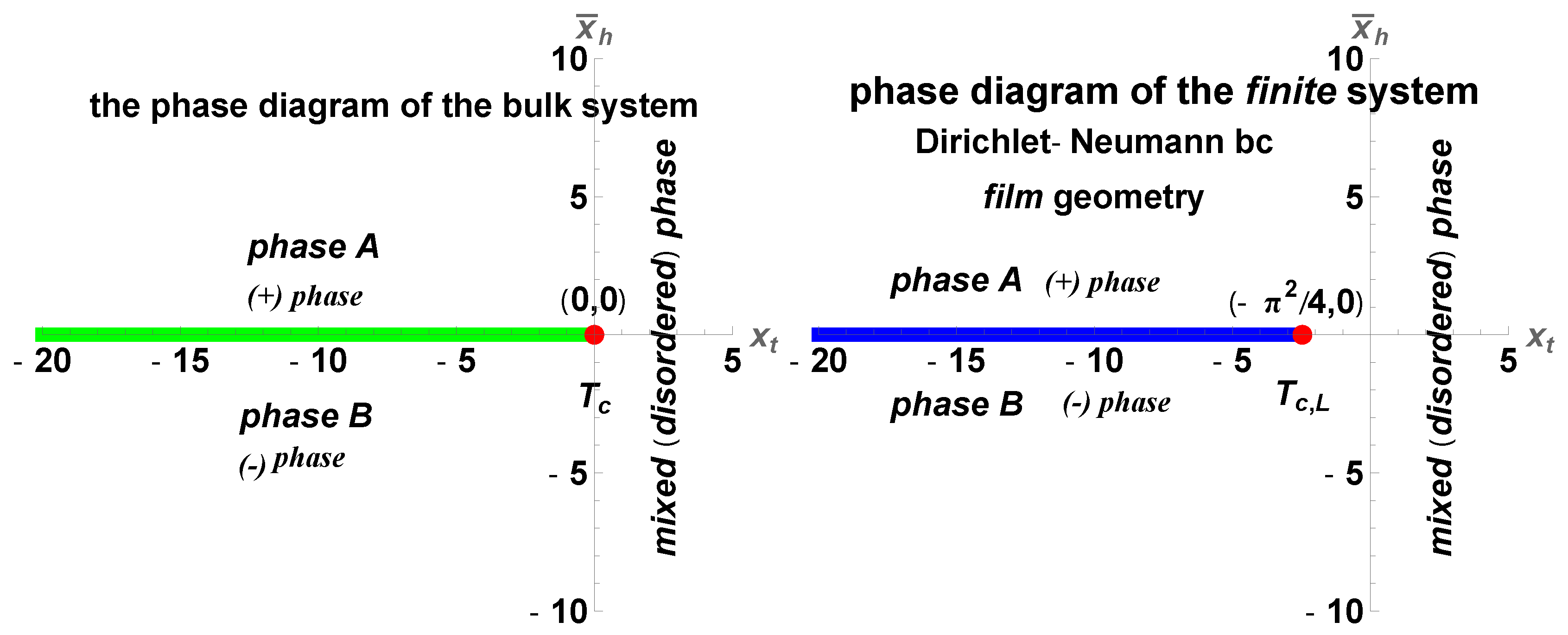

Figure 12.

Phase diagrams. Left panel: The phase diagram of the bulk system. Right panel: The phase diagram of the finite system with Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions. In the bulk system a phase transition of first order happens when crossing the phase coexistence line that is at and spans for . At the system exhibits a second order phase transition. In the finite system the coexistence line is at and spans for . The second order phase transition happens at . Note the change with Dirichlet-Dirichlet boundary conditions where the critical point is at .

Figure 12.

Phase diagrams. Left panel: The phase diagram of the bulk system. Right panel: The phase diagram of the finite system with Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions. In the bulk system a phase transition of first order happens when crossing the phase coexistence line that is at and spans for . At the system exhibits a second order phase transition. In the finite system the coexistence line is at and spans for . The second order phase transition happens at . Note the change with Dirichlet-Dirichlet boundary conditions where the critical point is at .

Figure 13.

The behavior of the scaling function for . We observe that the force is attractive, contrary to the corresponding result for the Gaussian model.

Figure 13.

The behavior of the scaling function for . We observe that the force is attractive, contrary to the corresponding result for the Gaussian model.

Figure 14.

The behavior of the scaling function , for several values of . We observe that the force is attractive.

Figure 14.

The behavior of the scaling function , for several values of . We observe that the force is attractive.

Figure 15.

The behavior of the scaling function , , . We observe that the force is attractive.

Figure 15.

The behavior of the scaling function , , . We observe that the force is attractive.