Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Casimir Force Within the Continuum Gaussian Model

3. The Casimir Force Within the Lattice Gaussian Model

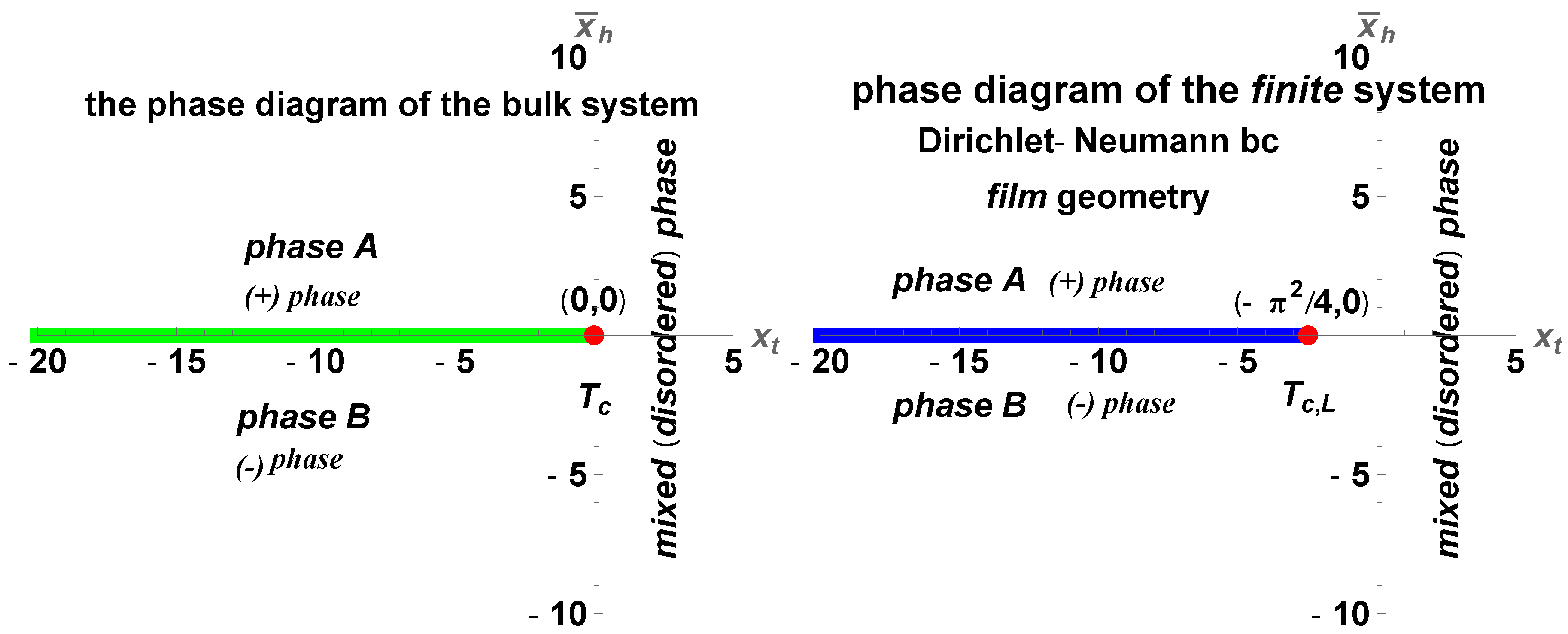

- periodic (p) boundary conditions

- Neumann - Dirichlet (ND) boundary conditions

- under fully periodic (p) boundary conditions, , one has , hence .

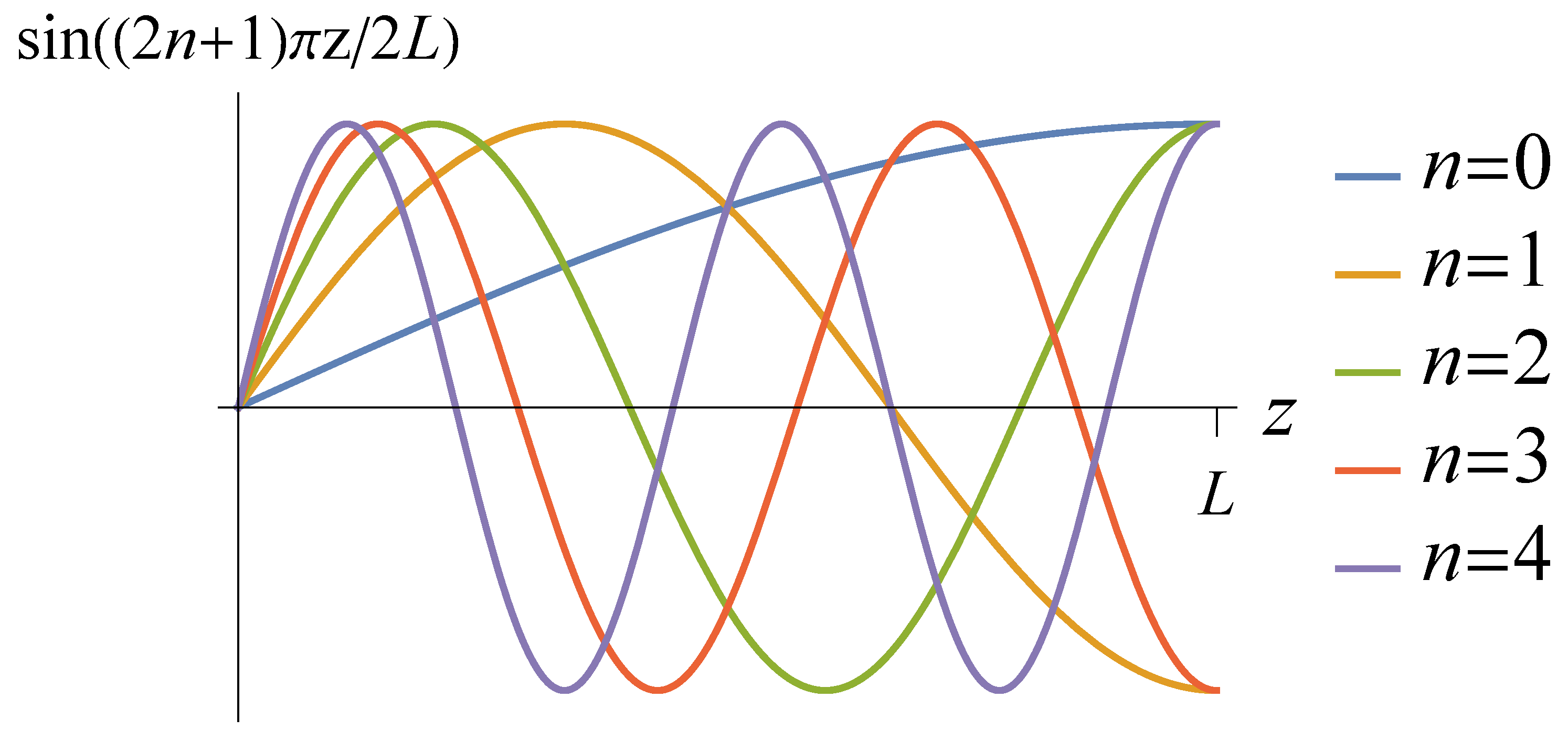

- under Neumann-Dirichlet boundary conditions along z direction, i.e., , one has , hence .

3.1. The Gaussian Model on a Lattice for the Case

The Behavior of the Interaction Term

The Behavior of the Interaction Term in the Bulk System

The Behavior of the Interaction Term in the Film System with Neumann-Dirichlet Boundary Conditions

The behavior of the field term

-

for boundary conditionsandObviously

-

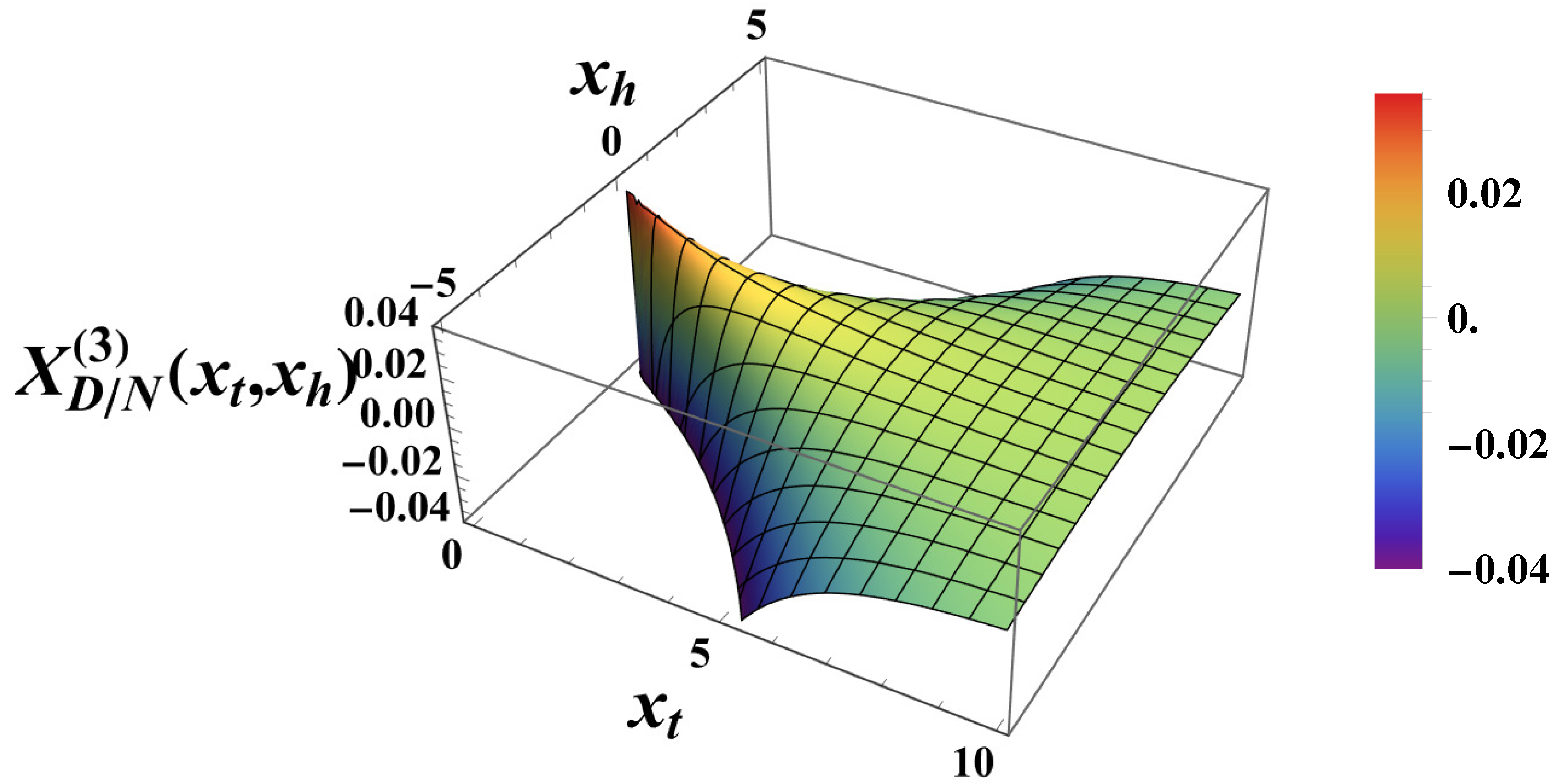

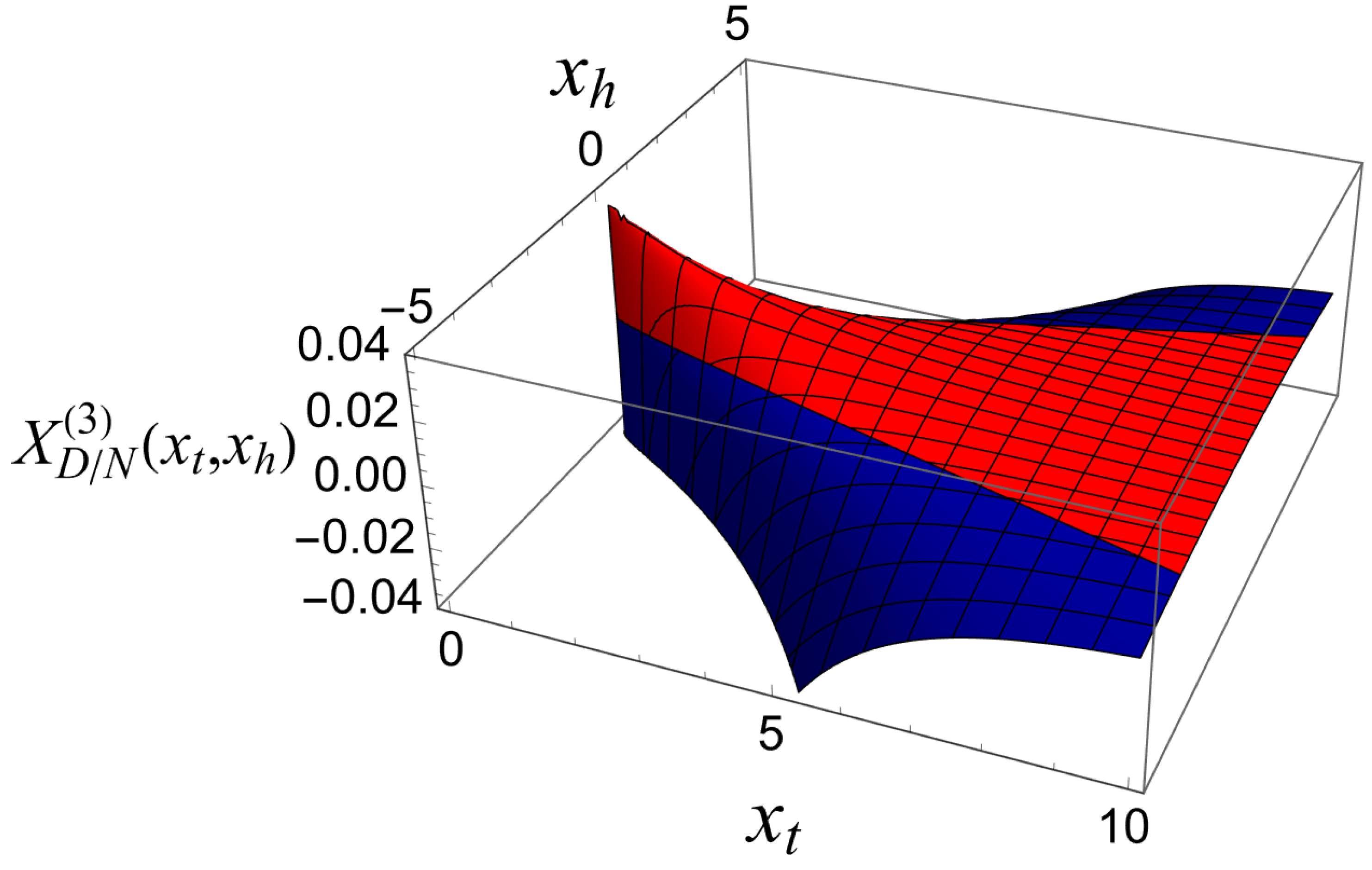

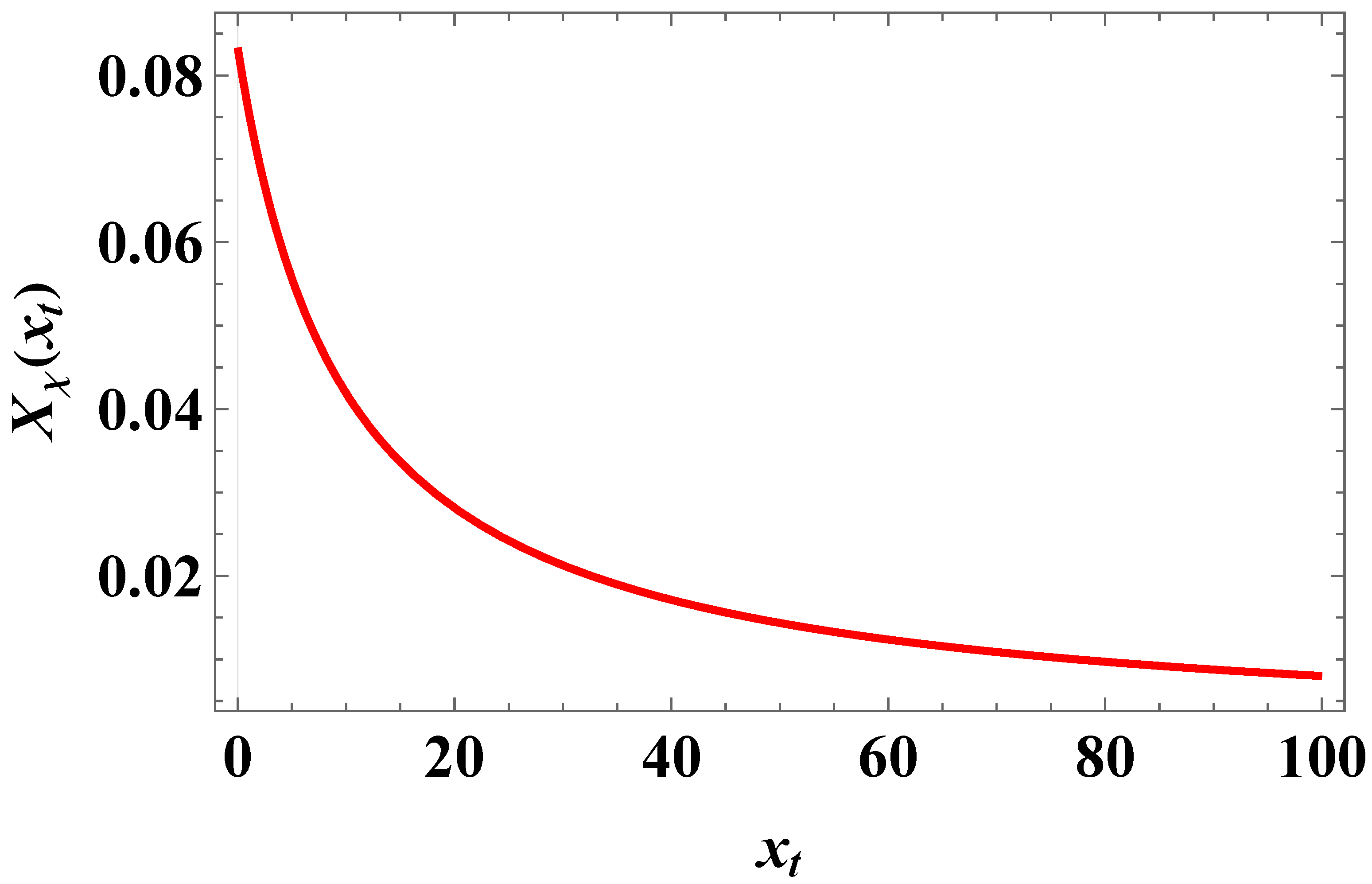

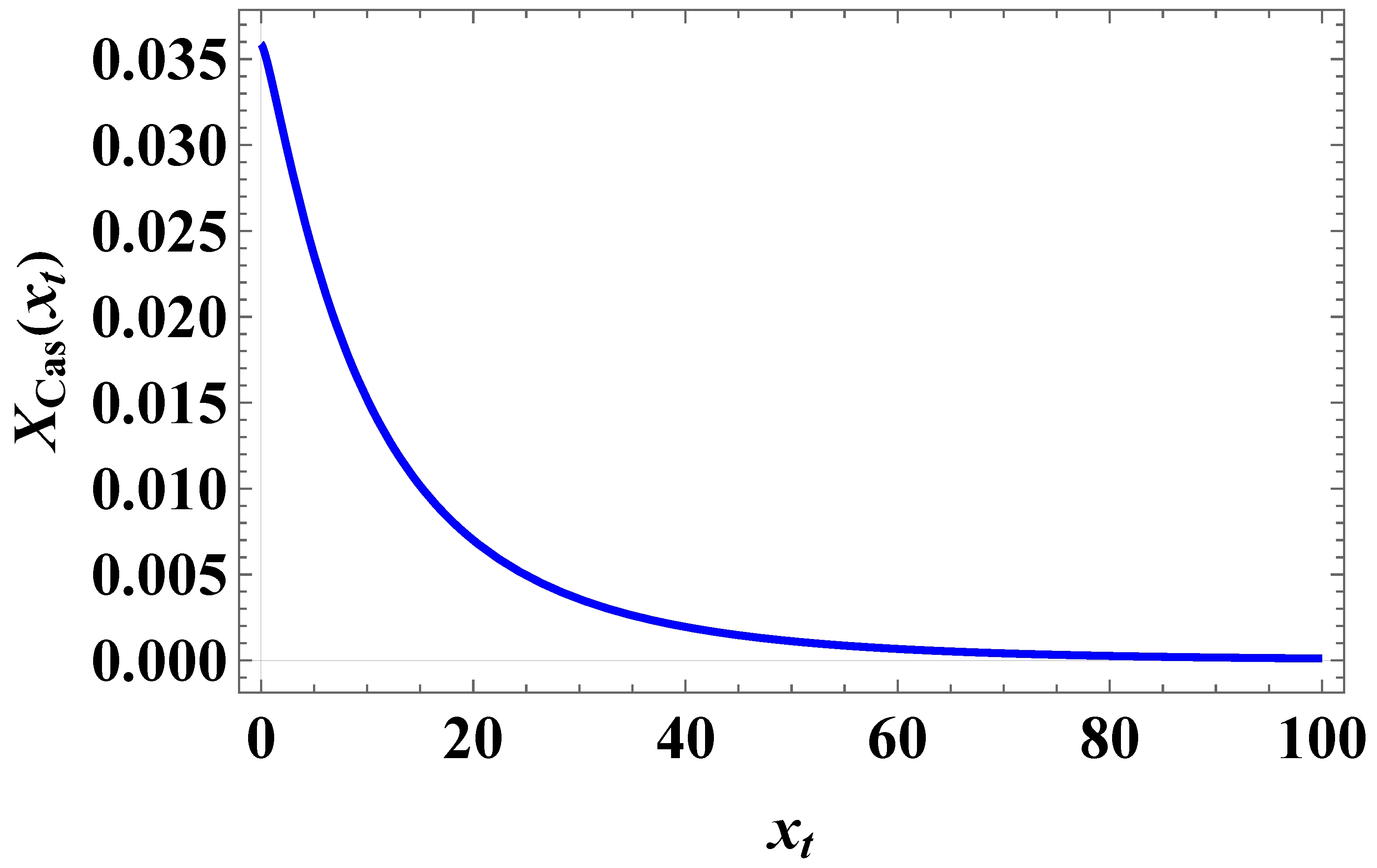

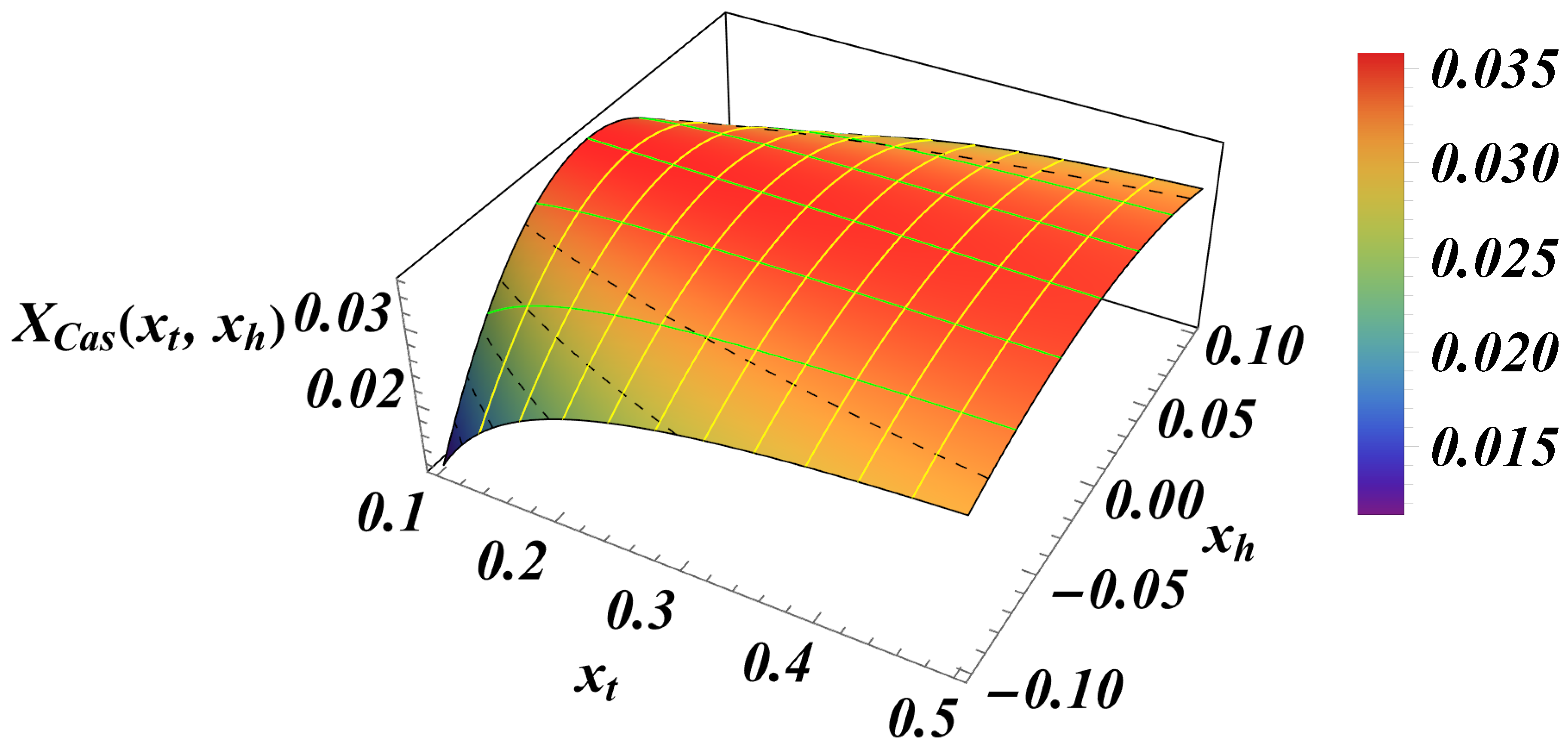

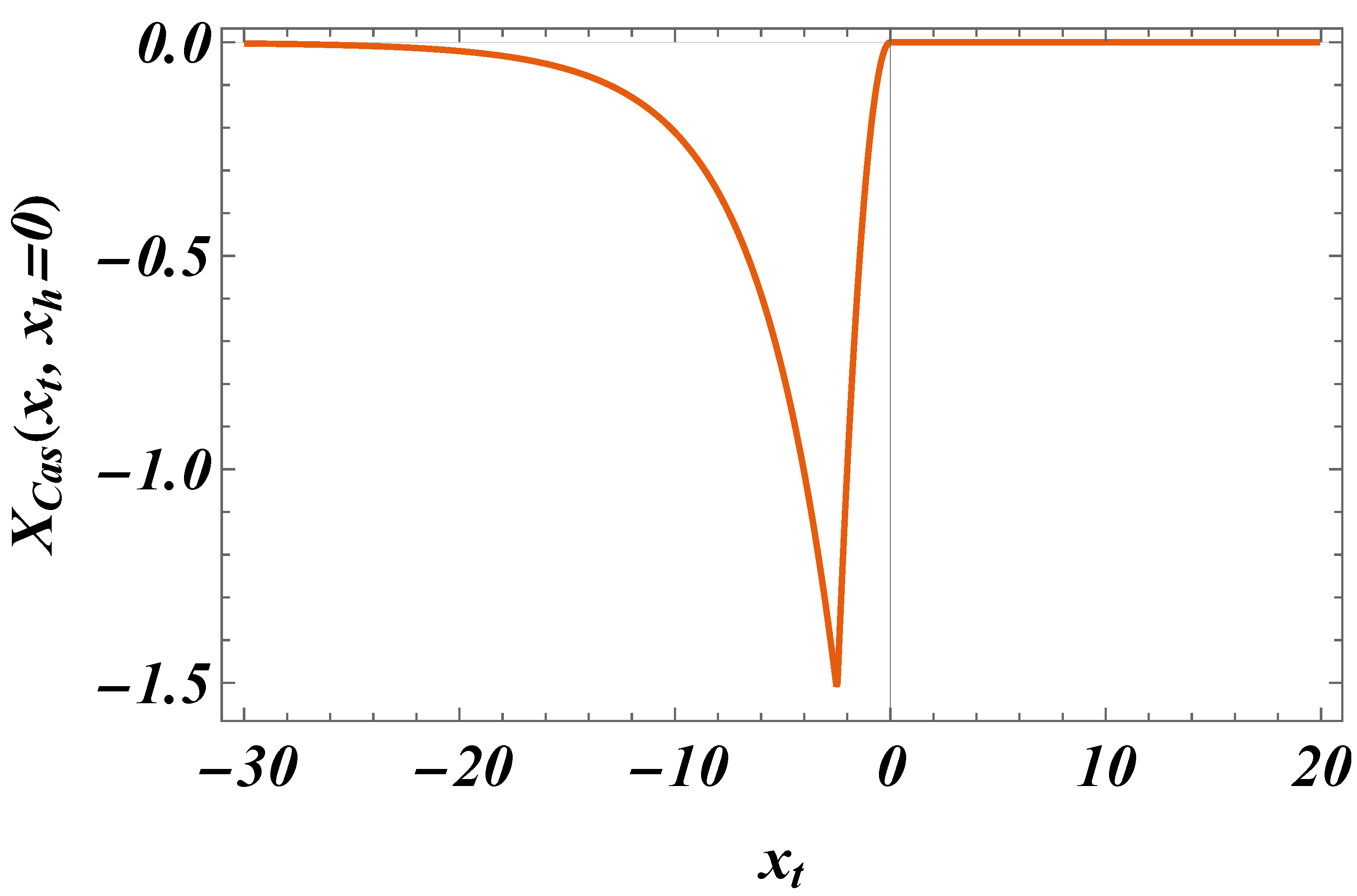

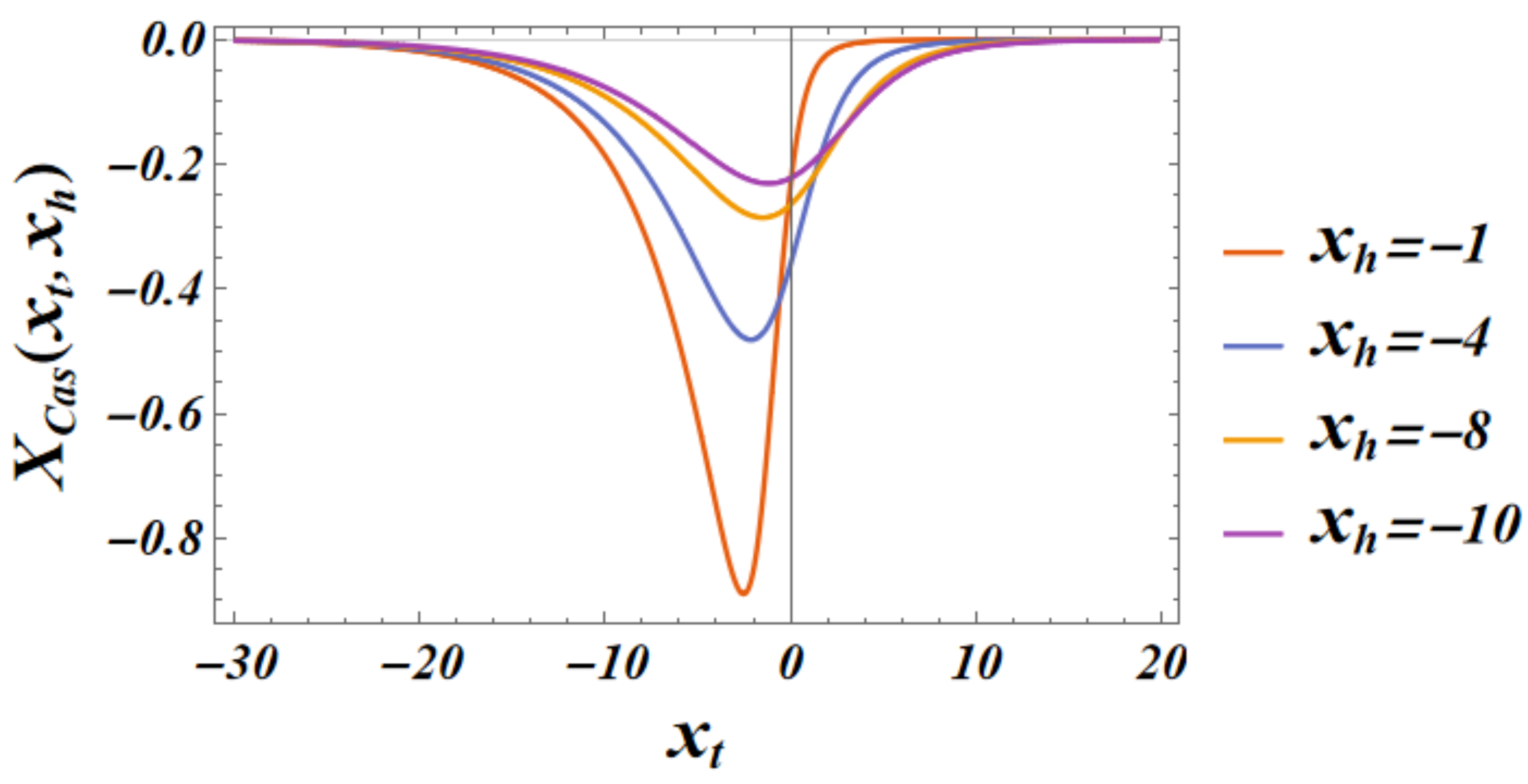

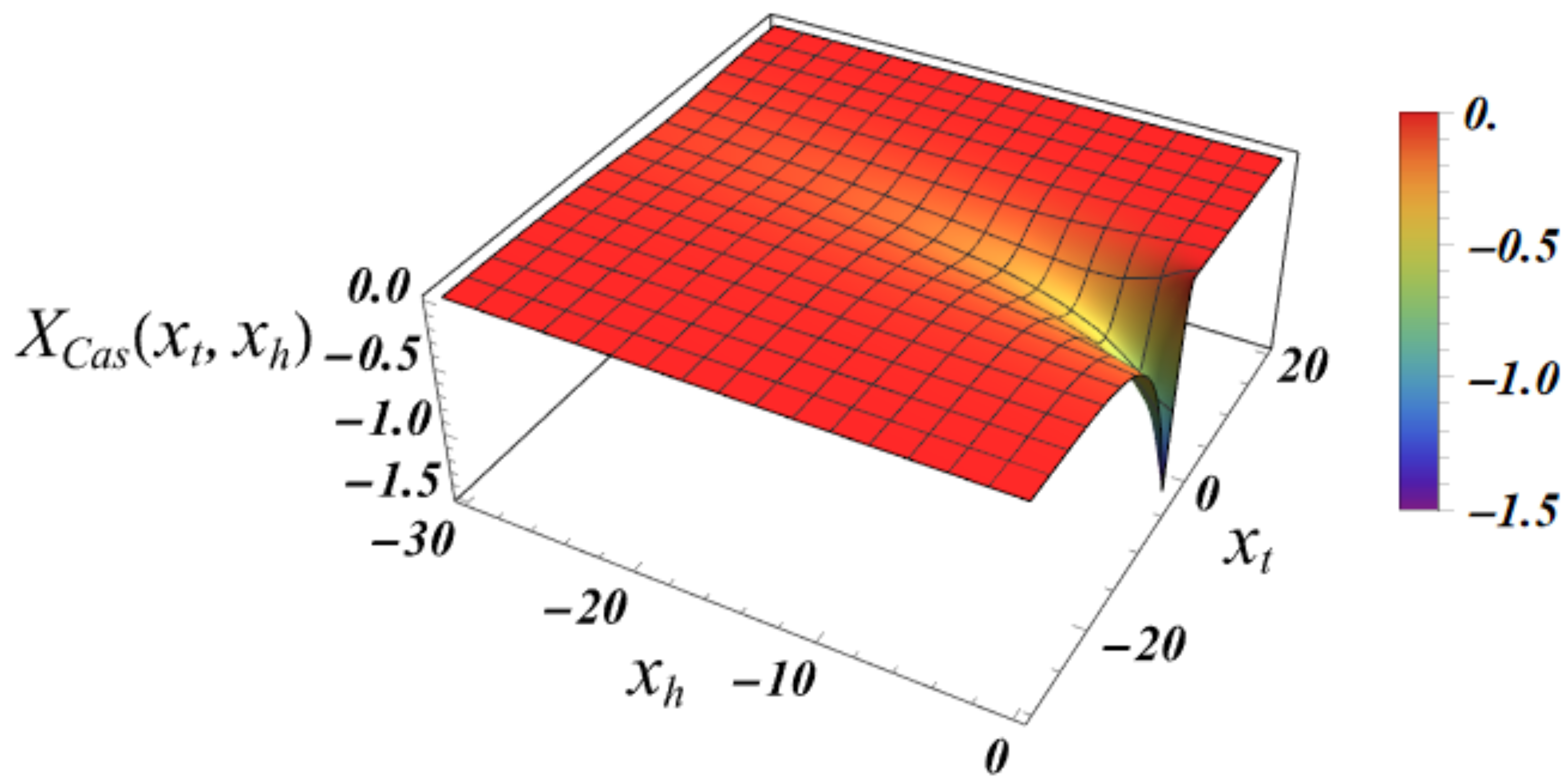

for boundary conditionsThus, setting and , for a film geometry we arrive atIt is easy to show thatThus, one hasLet us consider the small k behavior of the above sum. One derivesIn the limits and for the behavior of the field term one obtainsWhen , then , we obtain thatwhich indeed equals the bulk expression - see Equation (82).From Equation (87) for the behavior of the susceptibility in the finite system we deriveAccording to the finite-size scaling theory [34,56]where and are non-universal constants, and is an universal scaling function, , where T has the meaning of the temperature of the system, and is its bulk temperature. From Equation (90), taking into account that , we identify thatIt is clear that the field term in the free energy of the finite system will be of the same order as the field term, i.e., if . In order to achieve that, we define a field dependent scaling variableIn terms of it, Equation (87) becomesThe behavior of the scaling function is given in Figure 7.Then for the excess free energy related to the field term, see Equation (51), one derives

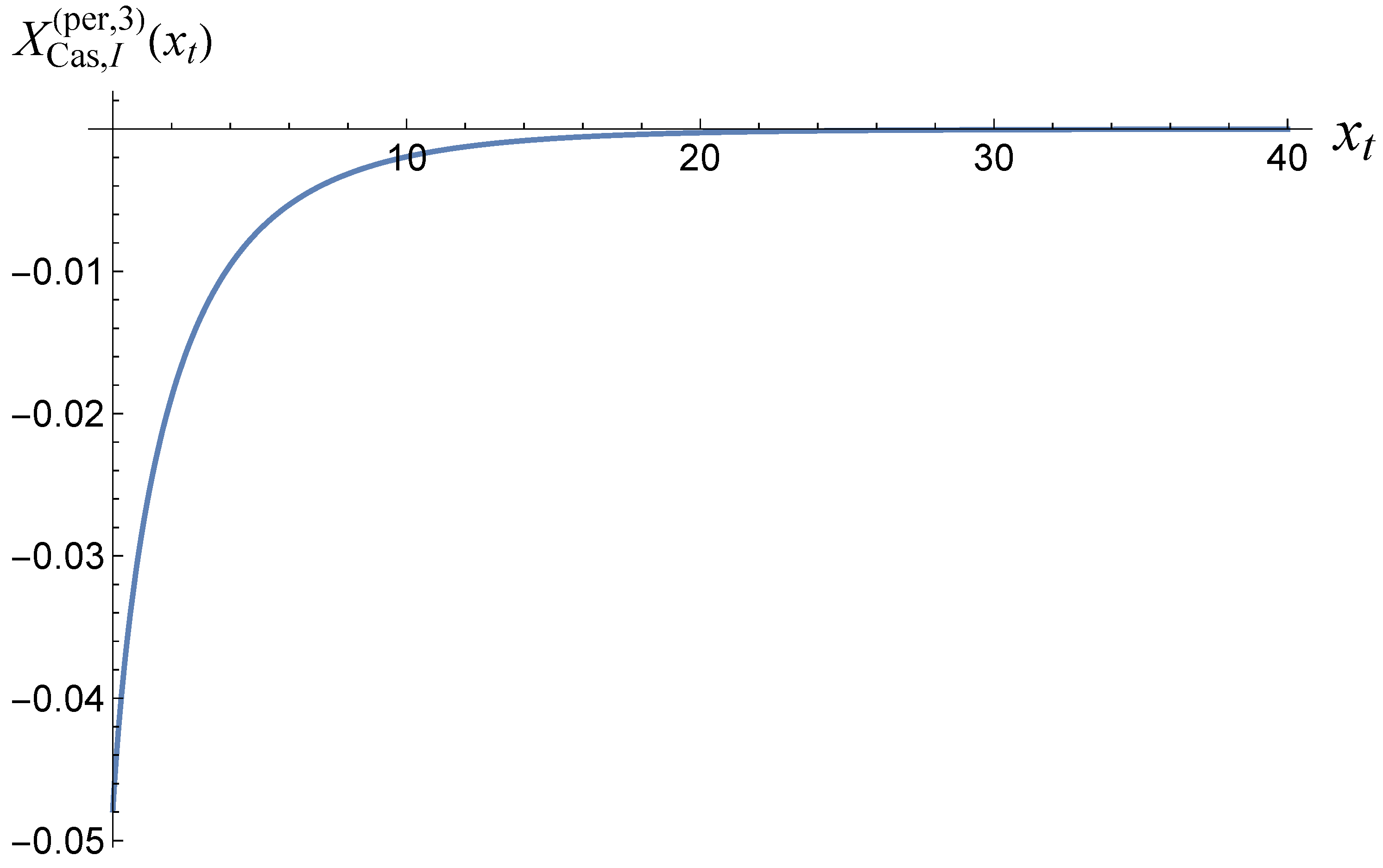

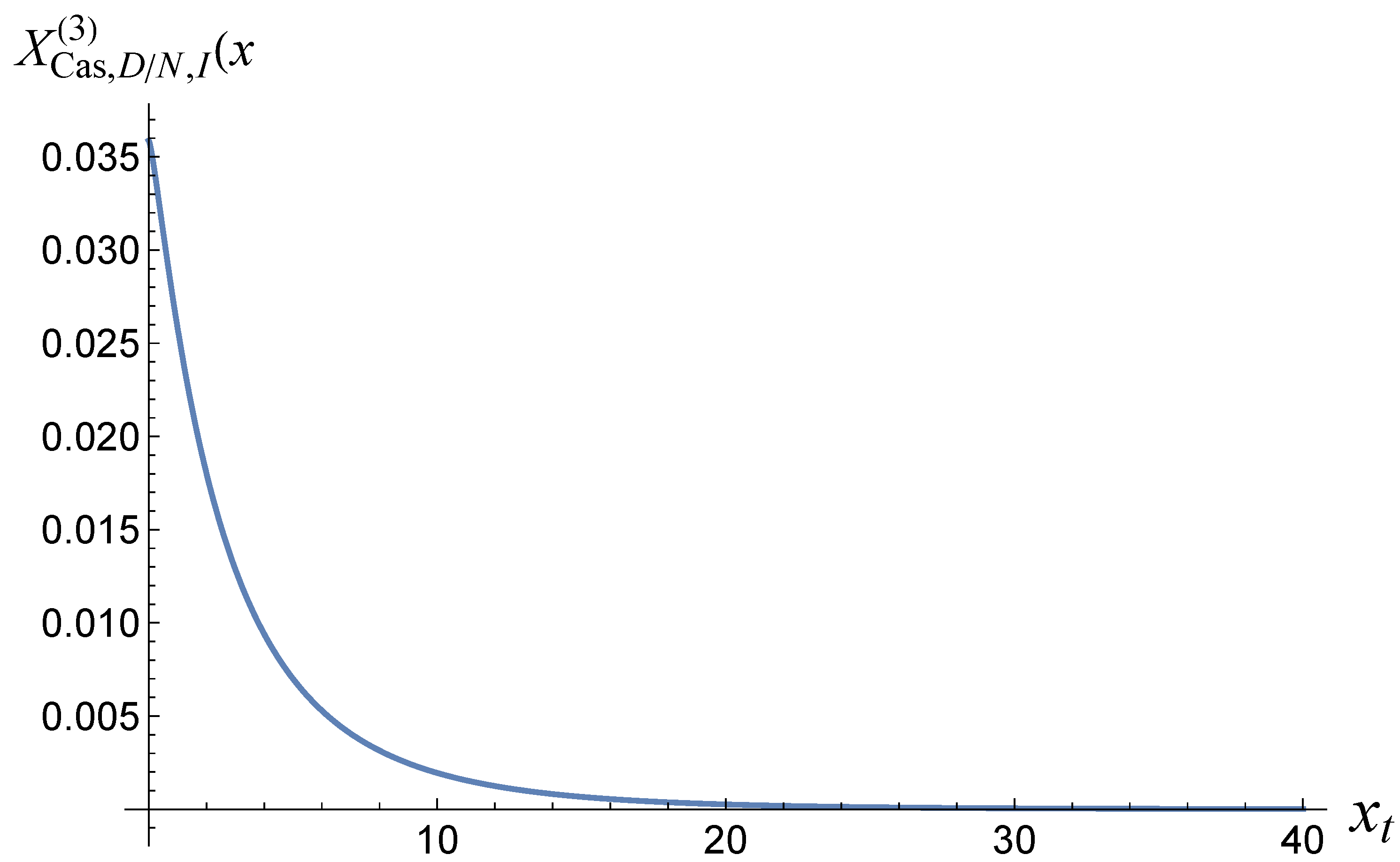

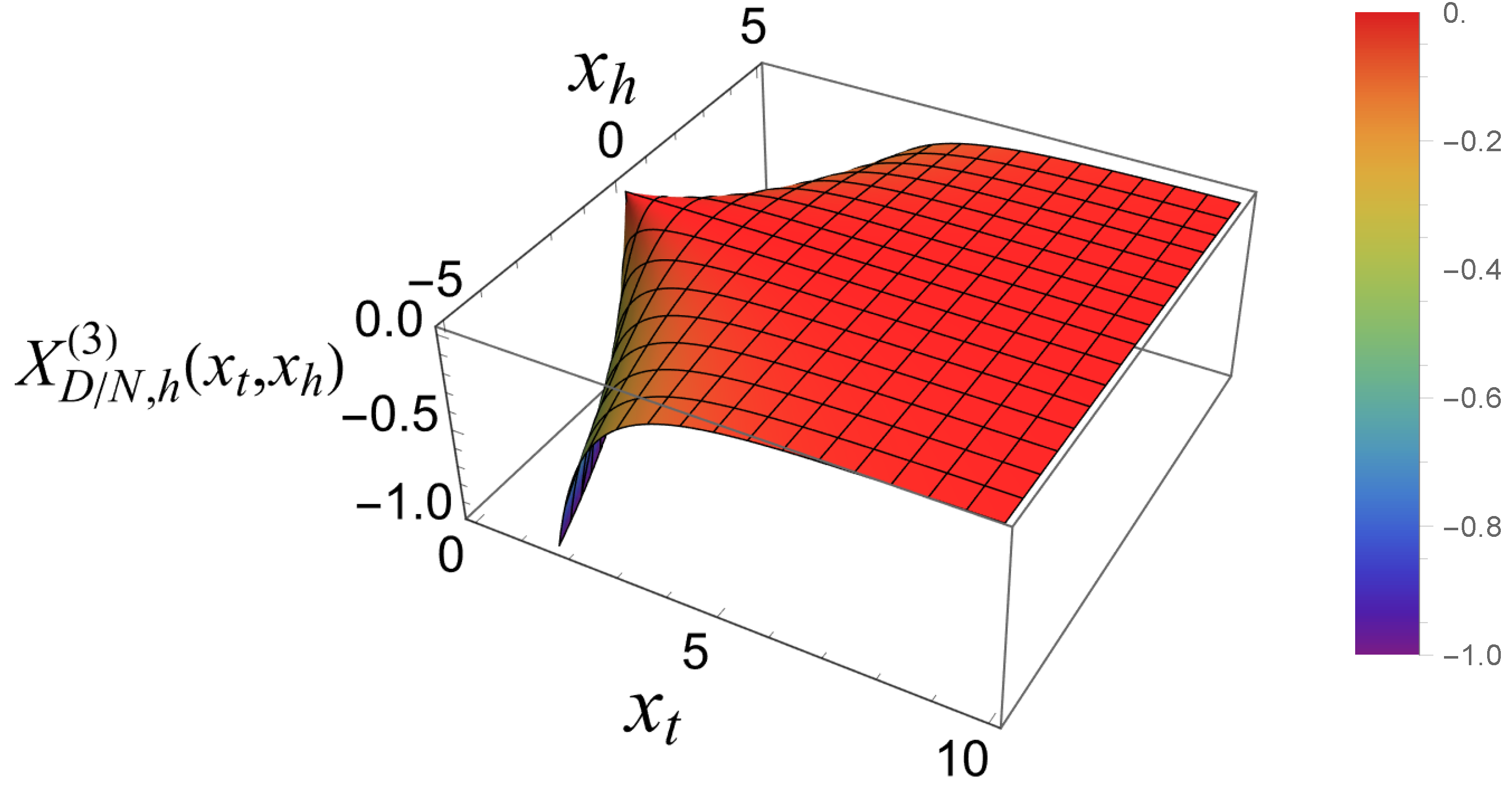

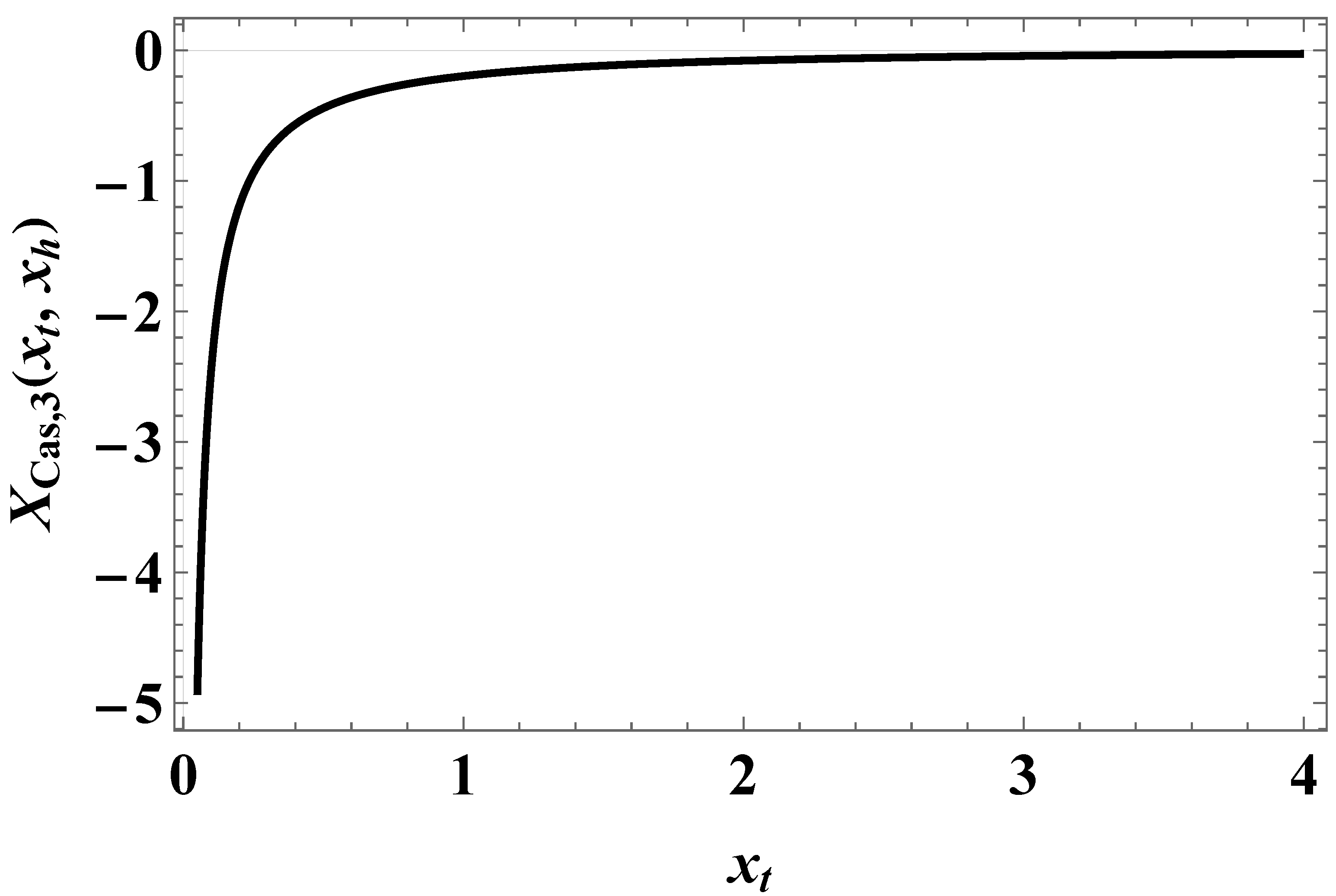

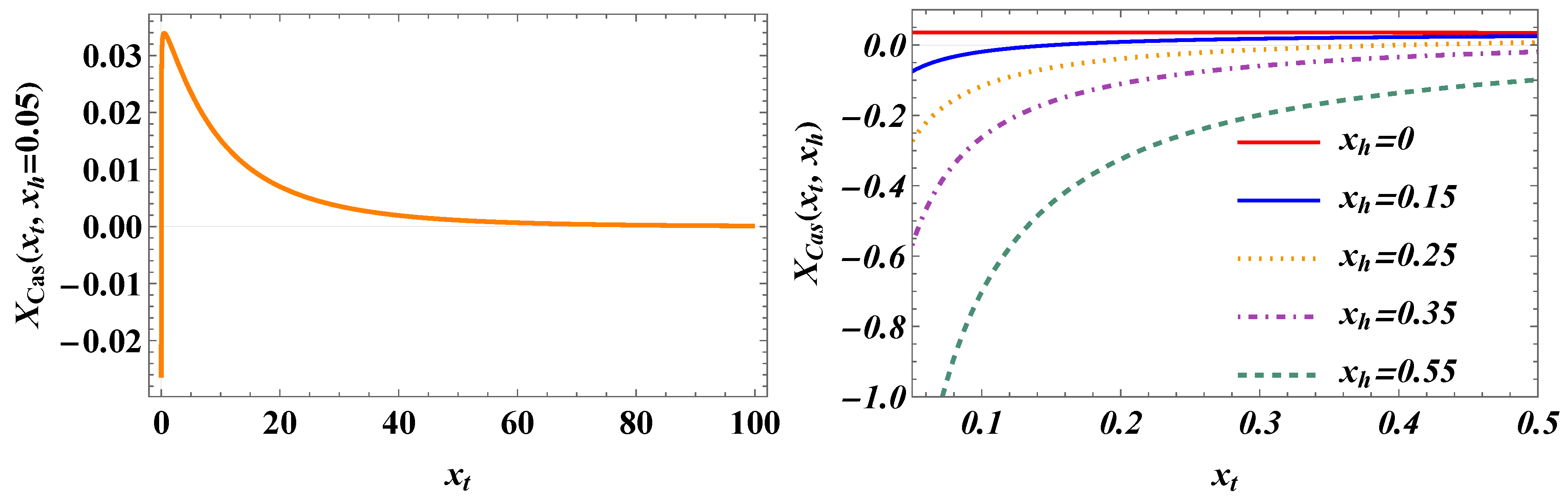

3.2. The Behavior of the Casimir Force

4. The Casimir Force Within the Mean-Field Model

4.1. The Ginzburg-Landau Functional

4.2. The Casimir Force for Zero External Field

4.3. The Casimir Force for Nonzero External Field

5. Conclusions

- I

-

We derived exact closed form expression for the free energy of the Gaussian model in both the continuum version (CGM) and the lattice formulation of the model (LGM). The results for the Casimir force can be written as a sum of

- i)

- ii)

We observe that these expression are identical, as is to be expected on the ground of the universality hypothesis, provided proper definitions of the scaling variables are used. - II

- The behavior of the Casimir force in the CGM is shown in Figure 3 and Figure 5, and the behavior for the LGM - in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. We observe that for the force is repulsive and, depending on magnitude of h, it can be both repulsive or attractive for . Contrary to this behavior, we observe that the force in the MFM is always attractive - both for , see Figure 13, as well as for – see Figure 14 and Figure 15.

- (*)

- (**)

- The predictions of the “workhorse" of statistical mechanics — the mean-field approach sometimes—in particular in the studies of the Casimir force—can be wrong even with respect to the predicted sign of the force.

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCF | critical Casimir force |

| BC’s | boundary conditions |

| DN | Dirichlet–Neumann |

| GCE | grand canonical ensemble |

| LGM | lattice Gaussian model |

| CGM | continuum Gaussian model |

References

- Casimir, H.B. On the Attraction Between Two Perfectly Conducting Plates. Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet. 1948, 51, 793–796. [Google Scholar]

- Mostepanenko, V.M.; Trunov, N.N. The Casimir effect and its applications; Energoatomizdat, Moscow, 1990, Ed.; English version: Clarendon, New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kardar, M.; Golestanian, R. The "friction" of vacuum, and other fluctuation-induced forces. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999, 71, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, K.A. The Casimir Effect: Physical Manifestations of Zero-point Energy; World Scientific: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bordag, M.; Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mohideen, U.; Mostepanenko, V.M. Advances in the Casimir effect; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Milton, K.A. The Casimir effect: Recent controversies and progress. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 2004, 37, R209–R277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genet, C.; Lambrecht, A.; Reynaud, S. The Casimir effect in the nanoworld. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2008, 160, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mohideen, U.; Mostepanenko, V.M. Control of the Casimir force using semiconductor test bodies. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2011, 25, 171–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.W.; Capasso, F.; Johnson, S.G. The Casimir effect in microstructured geometries. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhabadi, A.; Abadian, N.; Kanjouri, F.; Abadyan, M. Casimir force-induced instability in freestanding nanotweezers and nanoactuators made of cylindrical nanowires. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2014, 28, 1450129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhabadi, A.; Mokhtari, J.; Rach, R.; Abadyan, M. Modeling the influence of the Casimir force on the pull-in instability of nanowire-fabricated nanotweezers. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2015, 29, 1450245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.E.; de Gennes, P.G. Phénomènes aux parois dans un mélange binaire critique. C. R. Seances Acad. Sci. Paris Ser. B 1978, 287, 207–209. [Google Scholar]

- Maciołek, A.; Dietrich, S. Collective behavior of colloids due to critical Casimir interactions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantchev, D.; Dietrich, S. Critical Casimir effect: Exact results. Phys. Rep. 2023, 1005, 1–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambassi, A.; Dietrich, S. Critical Casimir forces in soft matter. Soft Matter. [CrossRef]

- Dantchev, D. On Casimir and Helmholtz Fluctuation-Induced Forces in Micro- and Nano-Systems: Survey of Some Basic Results. Entropy, 26, 499. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Chan, M.H.W. Critical Fluctuation-Induced Thinning of 4He Films near the Superfluid Transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 1187–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Chan, M.H.W. Critical Casimir Effect near the 3He - 4He Tricritical Point. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 086101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganshin, A.; Scheidemantel, S.; Garcia, R.; Chan, M.H.W. Critical Casimir Force in 4He Films: Confirmation of Finite-Size Scaling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 075301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyka, F.; Zvyagolskaya, O.; Hertlein, C.; Helden, L.; Bechinger, C. Critical Casimir Forces in Colloidal Suspensions on Chemically Patterned Surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 101, 208301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertlein, C.; Helden, L.; Gambassi, A.; Dietrich, S.; Bechinger, C. Direct measurement of critical Casimir forces. Nature 2008, 451, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellen, U.; Helden, L.; Bechinger, C. Tunability of critical Casimir interactions by boundary conditions. EPL 2009, 88, 26001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagolskaya, O.; Archer, A.J.; Bechinger, C. Criticality and phase separation in a two-dimensional binary colloidal fluid induced by the solvent critical behavior. EPL 2011, 96, 28005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröndle, M.; Zvyagolskaya, O.; Gambassi, A.; Vogt, D.; Harnau, L.; Bechinger, C.; Dietrich, S. Trapping colloids near chemical stripes via critical Casimir forces. Mol. Phys. 2011, 109, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladugu, S.; Callegari, A.; Tuna, Y.; Barth, L.; Dietrich, S.; Gambassi, A.; Volpe, G. Nonadditivity of critical Casimir forces. Nat. Comm. 2016, 7, 11403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.; Magazzù, A.; Callegari, A.; Biancofiore, L.; Cichos, F.; Volpe, G. Microscopic Engine Powered by Critical Demixing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 068004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magazzù, A.; Callegari, A.; Staforelli, J.P.; Gambassi, A.; Dietrich, S.; Volpe, G. Controlling the dynamics of colloidal particles by critical Casimir forces. Soft Matter 2019, 15, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.; Callegari, A.; Daddi-Moussa-Ider, A.; Munkhbat, B.; Verre, R.; Shegai, T.; Käll, M.; Löwen, H.; Gambassi, A.; Volpe, G. Tunable critical Casimir forces counteract Casimir–Lifshitz attraction. Nat. Phys. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, P.; Bafi, N.F.; Volpe, G.; Kondrat, S.; Dietrich, S. Critical Casimir levitation of colloids above a bull’s-eye pattern. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 2409.08366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Nowakowski, P.; Bafi, N.F.; Midtvedt, B.; Schmidt, F.; Verre, R.; Käll, M.; Dietrich, S.; Kondrat, S.; Volpe, G. Nanoalignment by Critical Casimir Torques. Nature communications, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.N. Finite-size Scaling. In Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena; Domb, C.; Lebowitz, J.L., Eds.; Academic, London, 1983; Vol. 8, chapter 2, pp. 146–266.

- Binder, K. Critical Behaviour at Surfaces. In Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena; Domb, C.; Lebowitz, J.L., Eds.; Academic, London, 1983; Vol. 8, chapter 1, pp. 1–145.

- Privman, V. Finite-Size Scaling Theory. In Finite Size Scaling and Numerical Simulations of Statistical Systems; Privman, V., Ed.; World Scientific, Singapore, 1990; p. 1.

- Brankov, J.G.; Dantchev, D.M.; Tonchev, N.S. The Theory of Critical Phenomena in Finite-Size Systems - Scaling and Quantum Effects; World Scientific, Singapore, 2000.

- Evans, R. Microscopic theories of simple fluids and their interfaces. In Liquids at interfaces; Charvolin, J.; Joanny, J.; Zinn-Justin, J., Eds.; Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1990; Vol. XLVIII, Les Houches Session.

- Krech, M. Casimir Effect in Critical Systems; World Scientific, Singapore, 1994.

- Krech, M.; Dietrich, S. Free energy and specific heat of critical films and surfaces. Phys. Rev. A 1992, 46, 1886–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantchev, D.; Krech, M. Critical Casimir force and its fluctuations in lattice spin models: Exact and Monte Carlo results. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 046119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastening, B.; Dohm, V. Finite-size effects in film geometry with nonperiodic boundary conditions: Gaussian model and renormalization-group theory at fixed dimension. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81, 061106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, H.W.; Rutkevich, S.B. Fluctuation-induced forces in confined ideal and imperfect Bose gases. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 95, 062112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantchev, D.; Rudnick, J. Manipulation and amplification of the Casimir force through surface fields using helicity. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 95, 042120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M. Dynamics and steady states of a tracer particle in a confined critical fluid. J. Stat. Mech. 0632; 09, arXiv:cond-mat.stat-mech/2101.02072]. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M.; Gambassi, A.; Dietrich, S. Fluctuations of the critical Casimir force. Phys. Rev. E 2021, 103, 062118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krech, M. Casimir forces in binary liquid mixtures. Phys. Rev. E 1997, 56, 1642–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, A.O.; Evans, R. Novel phase behavior of a confined fluid or Ising magnet. Phys. A 1992, 181, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambassi, A.; Dietrich, S. Critical dynamics in thin films. J. Stat. Phys. 2006, 123, 929–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantchev, D.; Schlesener, F.; Dietrich, S. Interplay of critical Casimir and dispersion forces. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 76, 011121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, R.; Shackell, A.; Rudnick, J.; Kardar, M.; Chayes, L.P. Thinning of superfluid films below the critical point. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 76, 030601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev, O.; Maciòłek, A.; Dietrich, S. Critical Casimir forces for Ising films with variable boundary fields. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 041605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohry, T.F.; Kondrat, S.; Maciolek, A.; Dietrich, S. Critical Casimir interactions around the consolute point of a binary solvent. Soft Matter 2014, arXiv:cond-mat.soft/1403.5492]10, 5510–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantchev, D.M.; Vassilev, V.M.; Djondjorov, P.A. Exact results for the behavior of the thermodynamic Casimir force in a model with a strong adsorption. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 0932. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M.; Vasilyev, O.; Gambassi, A.; Dietrich, S. Critical adsorption and critical Casimir forces in the canonical ensemble. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 94, 022103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradshteyn, I.S.; Ryzhik, I.H. Table of Integrals, Series, and Products; Academic, New York, 2007.

- Olver, F.W.J.; Lozier, D.W.; Boisvert, R.F.; Clark, C.W. (Eds.) NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions; NIST and Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010.

- Ma, S.K. Modern theory of critical phenomena; Advanced book classics, Perseus: Cambridge, Mass, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Privman, V. Finite-size scaling theory. In Finite Size Scaling and Numerical Simulations of Statistical Systems; Privman, V., Ed.; World Scientific, Singapore, 1990; pp. 1–98.

- Gelfand, I.M.; Fomin, S.V. Calculus of variations, revised english edition translated and edited by richard a. silverman ed.; Prentice-Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963.

- Courant, R.; Hilbert, D. Methods of Mathematical Physics; Vol. 1, Wiley-VCH, 1989.

- Dickey, L.A. On the Variation of a Functional when the Boundary of the Domain is not Fixed. Lett. Math. Phys. 2007, 83, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indekeu, J.O.; Nightingale, M.P.; Wang, W.V. Finite-size interaction amplitudes and their universality: Exact, mean-field, and renormalization-group results. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 34, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesener, F.; Hanke, A.; Dietrich, S. Critical Casimir forces in colloidal suspensions. J. Stat. Phys. 2003, 110, 981–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantchev, D.; Vassilev, V.M.; Djondjorov, P.A. Analytical results for the Casimir force in a Ginzburg–Landau type model of a film with strongly adsorbing competing walls. Phys. A 2018, 510, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantchev, D.; Vassilev, V. ϕ4 model under Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, E.T.; Watson, G.N. A Course of Modern Analysis; Cambridge University Press, London, 1963.

- Krech, M.; Dietrich, S. Finite-size scaling for critical films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 66, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).