Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Essential azoheterocyclic core

- N-methyl group for optimized GABA-A receptor binding

- Strategically positioned cycloalkyl/heterocyclyl rings for receptor pocket compatibility

- Azapirone structure with piperazine linker

- Specific alkylated terminal rings (pyrimidine, piperidine, pyridine, etc.)

- Optimal four-carbon spacing between cyclic systems

- Cycloalkyl/alkyl groups for metabolic stability

- Multiple hydrogen bond donors/acceptors

- Flexible alkyl chains for conformational adaptation

- Balanced lipophilicity for blood-brain barrier penetration

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. In Silico Analysis of Nootropic Potential

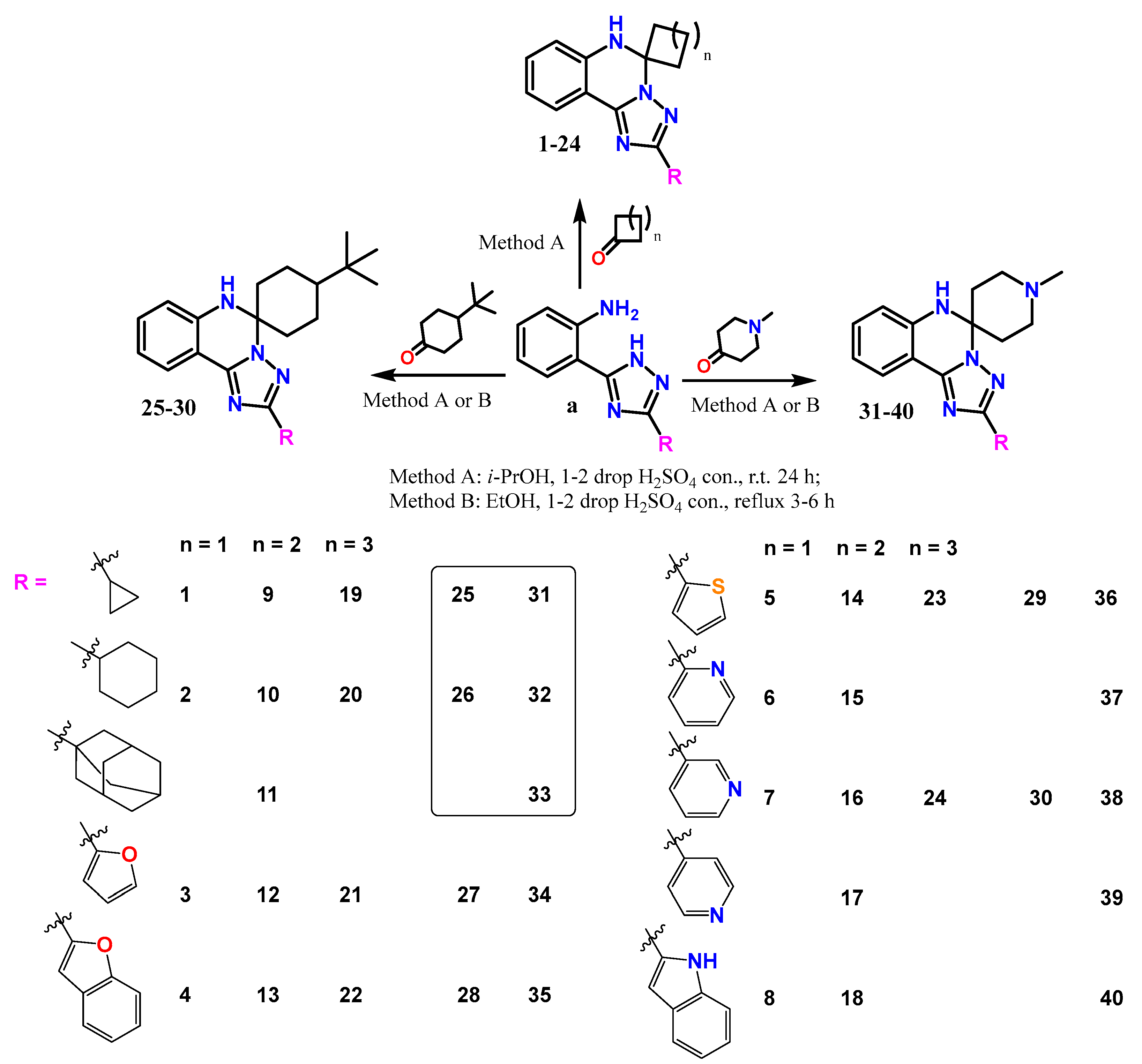

2.2. Synthesis

2.3. In Silico ADMET Studies

2.4. In Silico Analysis of Nootropic Potential

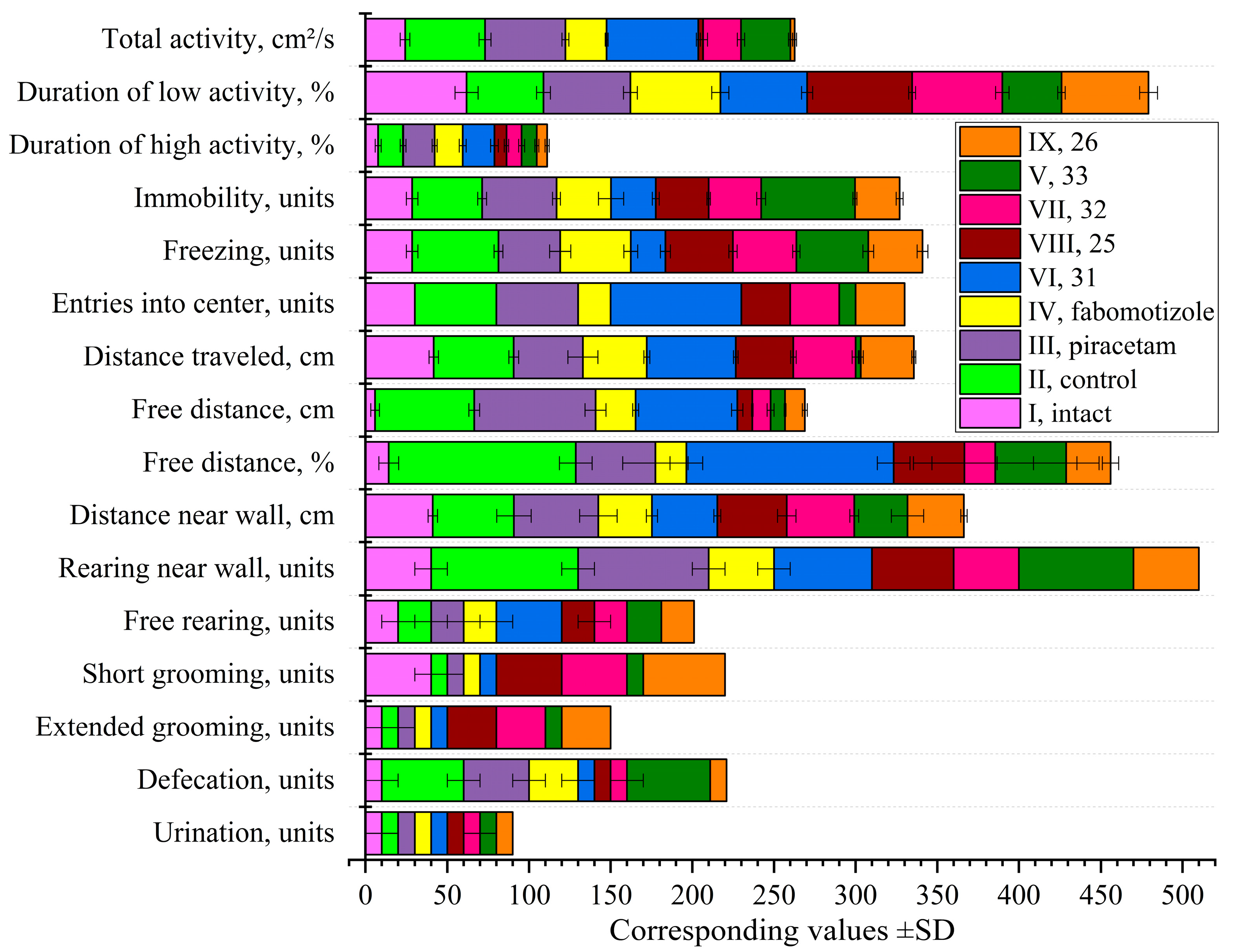

2.4.1. Open Field Test Following Ketamine Anesthesia

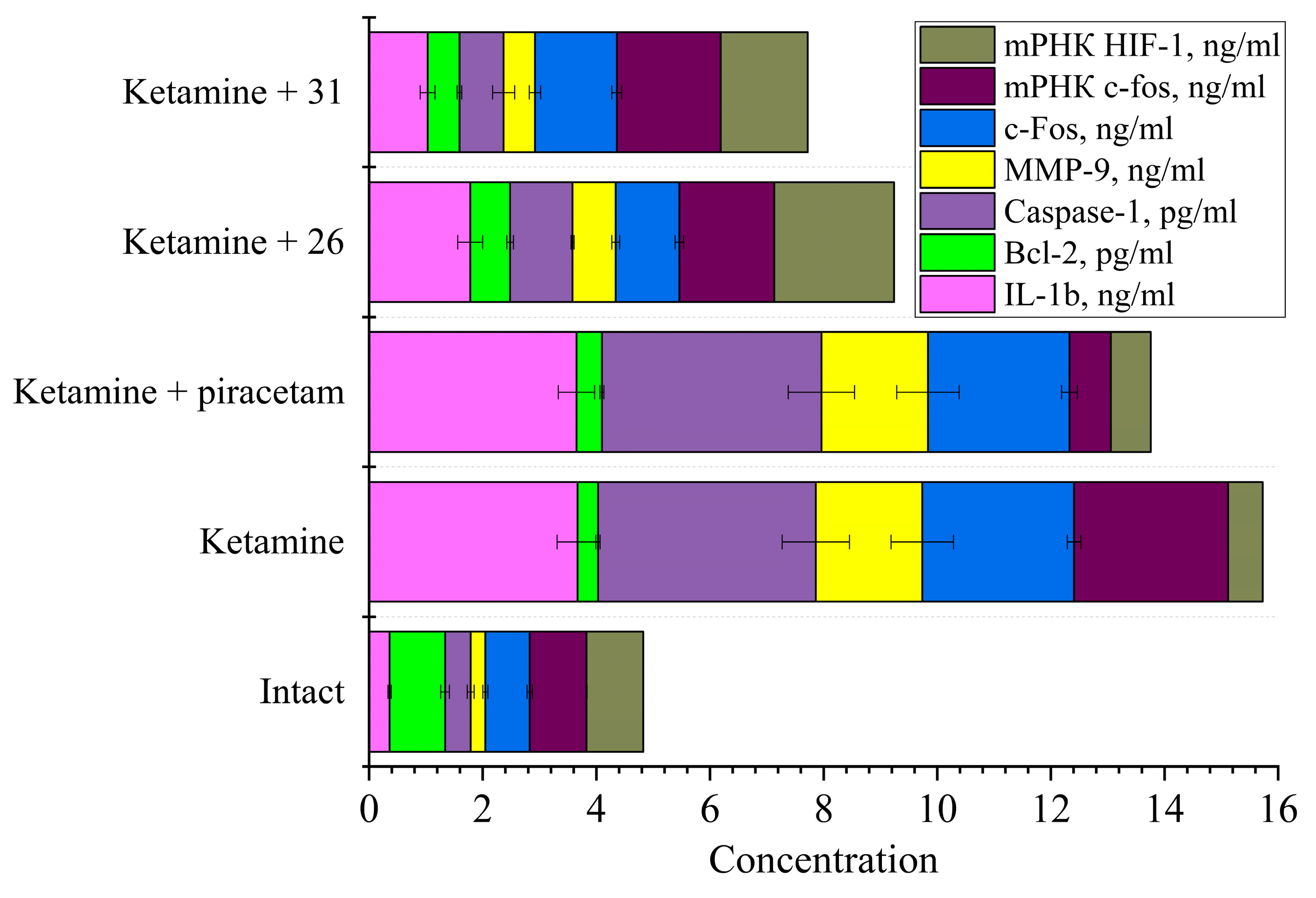

2.4.2. Study of Markers of Neuronal Damage

2.5. Structure-Activity Relationships

2.5.1. Correlation Molecular Structure and Behavioral Profiles

| Sub. | Structural features |

Behavioral profile |

Key effects | Potential applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | spiro cyclohexane 2'-cyclopropyl 4-(tert-butyl) |

Anti-hyperactivity | Normalized total activity Reduced high activity duration Increased low activity duration Normalized immobility Increased grooming behavior |

Ketamine recovery Potential anxiolytic |

| 26 | spiro cyclohexane 2'-cyclohexyl 4-(tert-butyl) |

Anti-hyperactivity | Normalized total activity Reduced high activity duration Normal low activity Reduced immobility Increased grooming behavior |

Ketamine recovery Mild anxiolytic |

| 31 | spiro N-methylpiperidine 2'-cyclopropyl |

Stimulatory / Anxiolytic | Increased total activity Increased high activity duration Maximum center entries Increased distance traveled High free distance |

Anxiolytic Potential anti-depressant Enhanced recovery |

| 32 | spiro N-methylpiperidine 2'-cyclohexyl |

Anti-hyperactivity | Normalized total activity Reduced high activity duration Normal low activity Increased grooming behavior |

Ketamine recovery Anxiolytic |

| 33 | spiro N-methylpiperidine 2'-adamantyl |

Sedative-like | Moderately reduced activity Minimal center entries Highest immobility Reduced distance traveled Maintained elevated defecation |

Sedative Potential hypnotic Different mechanism than traditional anxiolytics |

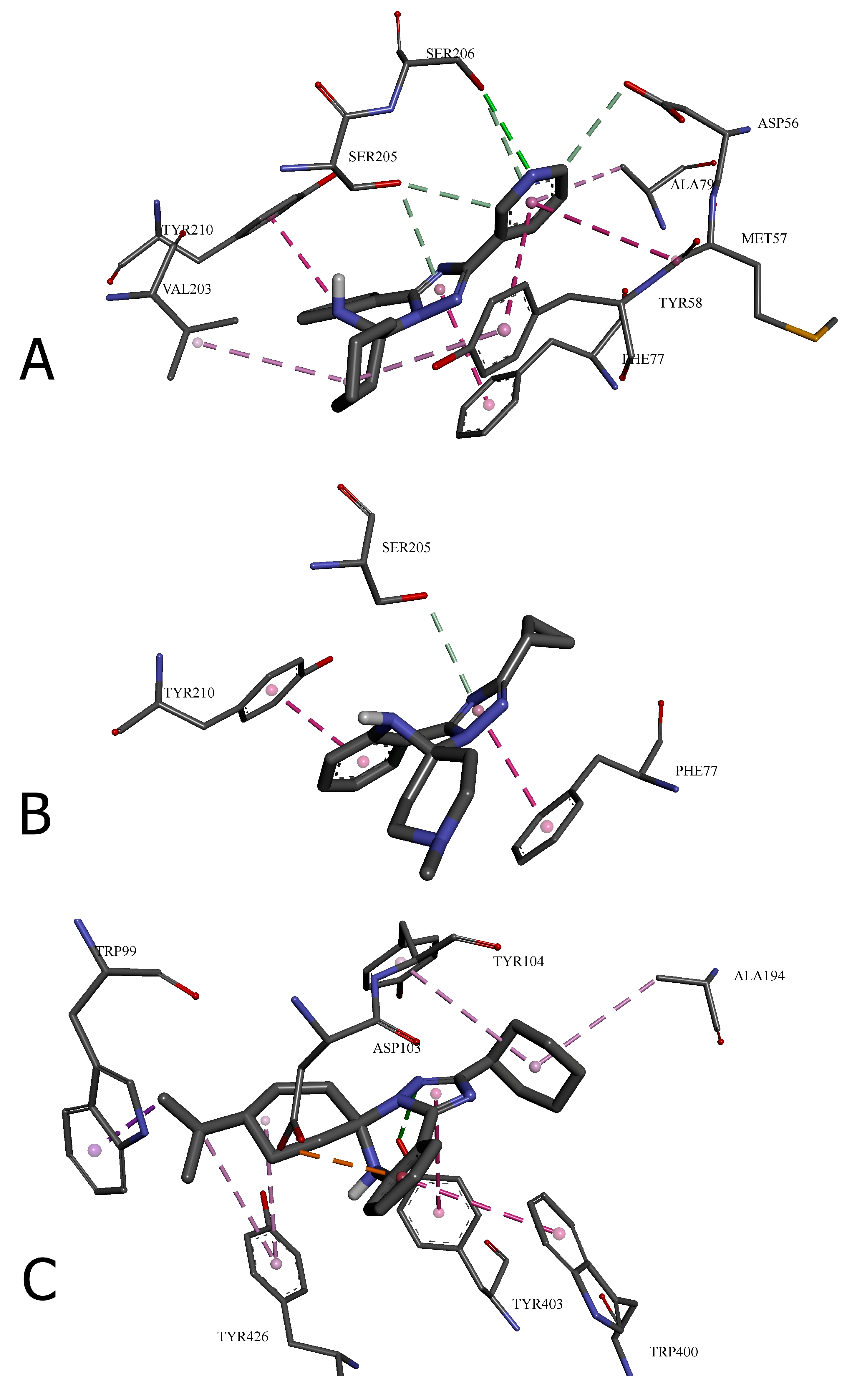

| Amino acid residue | Distance, ų | Bond category | Bond type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 with GABA(A) receptor (6HUP) | |||

| SER206 | 3.09118 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond |

| ASP56 | 3.2852 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| SER205 | 3.28938 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon Hydrogen Bond |

| SER205 | 3.67482 | Hydrogen Bond | π-Donor Hydrogen Bond |

| SER206 | 3.90775 | Hydrogen Bond | π-Donor Hydrogen Bond |

| TYR58 | 5.76264 | Hydrophobic | π-π Stacked |

| TYR210 | 4.04531 | Hydrophobic | π-π Stacked |

| PHE77 | 4.01868 | Hydrophobic | π-π Stacked |

| MET57 | 5.04132 | Hydrophobic | Amide-π Stacked |

| VAL203 | 4.58572 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl |

| TYR58 | 4.9221 | Hydrophobic | π-Alkyl |

| ALA79 | 4.92852 | Hydrophobic | π-Alkyl |

| 31 with GABA(A) receptor (6HUP) | |||

| SER205 | 3.7526 | Hydrogen Bond | π-Donor Hydrogen Bond |

| PHE77 | 3.96894 | Hydrophobic | π-π Stacked |

| TYR210 | 3.99648 | Hydrophobic | π-π Stacked |

| 26 with M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (5ZKB) | |||

| TYR403 | 2.87801 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond |

| ASP103 | 3.70202 | Electrostatic | π-Anion |

| TRP99 | 3.93043 | Hydrophobic | π-Sigma |

| TRP400 | 4.88215 | Hydrophobic | π-π T-shaped |

| TYR403 | 5.0193 | Hydrophobic | π-π T-shaped |

| ALA194 | 4.93091 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl |

| TYR104 | 5.41339 | Hydrophobic | π-Alkyl |

| TYR426 | 5.13581 | Hydrophobic | π-Alkyl |

| TYR426 | 5.27219 | Hydrophobic | π-Alkyl |

2.5.2. Behavioral Markers and Neurobiochemical Correlates

2.5.3. Structure-Based Optimization Strategies

2.5.4. Molecular Mechanisms and Target Hypotheses

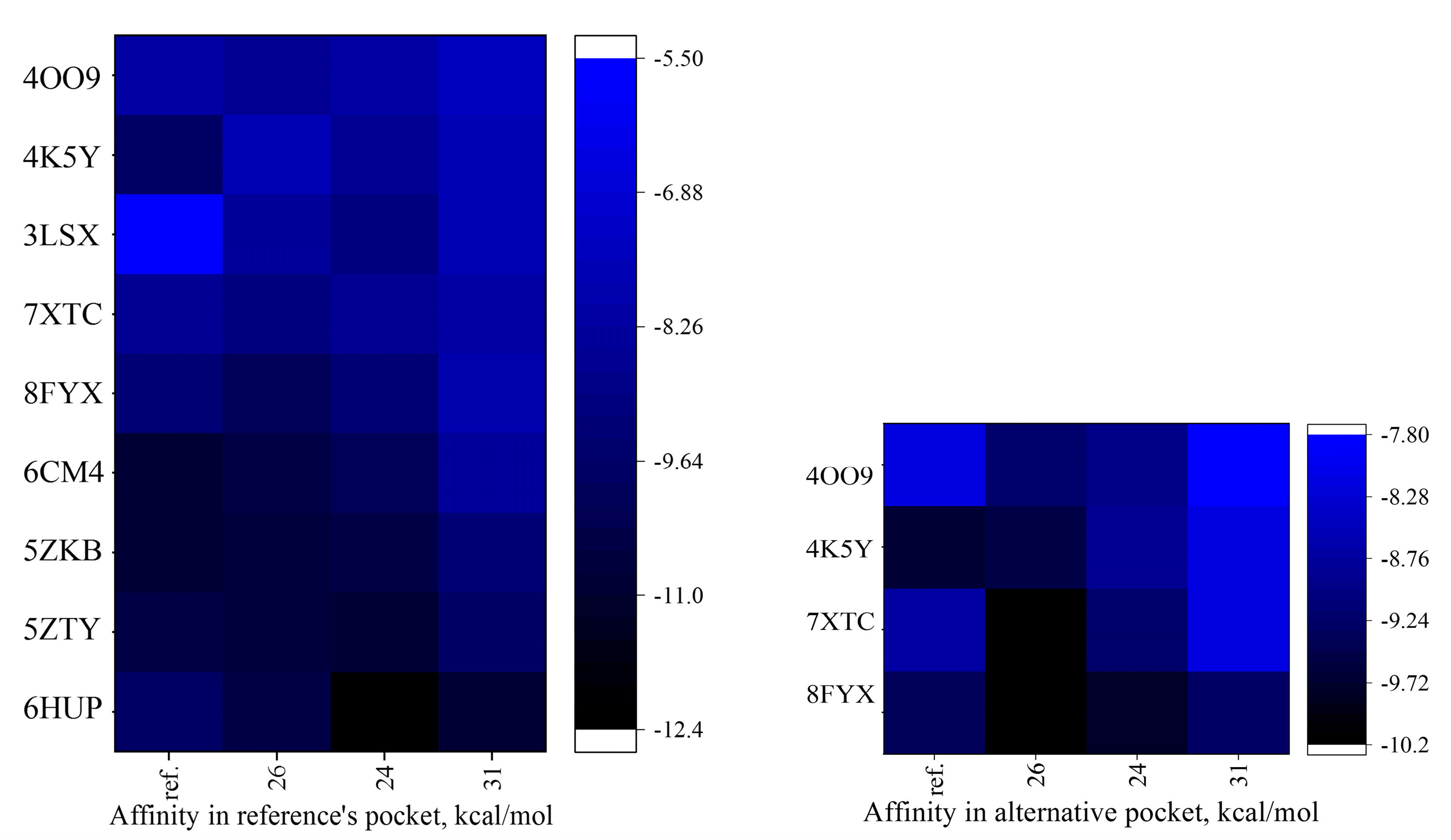

2.6. In Silico Molecular Docking to Nootropic and Anxiolytic Targets

2.6.1. Molecular Docking General Results

2.6.2. Structural Comparison and Binding Site Interactions

2.6.3. Refined Structure-Activity Relationships

2.7. Mechanistic Framework and Polypharmacology

2.8. Therapeutic Implications and Optimization Strategies

2.9. Therapeutic Implications and Optimization Strategies

2.10. Limitations of The Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Molecular Docking

3.2. Synthesis

3.3. Toxicity Studies

3.4. SwissADME Analysis

3.5. Biological Assay

3.5.1. Animals

3.5.2. Behavioral Tests

- Total distance traveled (cm)

- Overall motor activity (cm²/s)

- Activity structure (high activity, low activity, inactivity, %)

- Number of freezing episodes and entries into the center

- Distance traveled near the wall (cm) and in the central area of the arena (cm, %)

- Vertical exploratory activity (number of rearing on hind limbs near the wall and in the center)

- Number of short and long grooming events

- Number of defecation and urination acts

3.5.3. Removal of Animals from the Experiment

3.5.4. Preparation of Biological Material

3.5.5. Polymerase Chain Reaction in Real Time

3.5.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| POCD | Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| AMPA | α-Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazole Propionic Acid |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| 5-HT | 5-Hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin) |

| mGluR5 | Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 5 |

| CRF1R | Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Receptor 1 |

| CB₂ | Cannabinoid Receptor Type 2 |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-Aspartate |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| i-NOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| n-NOS | Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| SAR | Structure-Activity Relationship |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| n-ROTB | Number of Rotatable Bonds |

| n-HBA | Number of Hydrogen Bond Acceptors |

| n-HBD | Number of Hydrogen Bond Donors |

| TPSA | Topological Polar Surface Area |

| logP | Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient |

| MMP-9 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell Lymphoma 2 |

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity |

| GluA3 | Glutamate Receptor AMPA Type Subunit 3 |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| M2 | Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor M2 |

| D2 | Dopamine Receptor D2 |

References

- Leslie, E.; Pittman, E.; Drew, B.; Walrath, B. Ketamine Use in Operation Enduring Freedom. Mil. Med. 2021, 186, e720–e725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, F.K. Tactical Combat Casualty Care: Beginnings. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2017, 28, S12–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, J.; Fraser, G.L.; Puntillo, K.; Ely, E.W.; Gélinas, C.; Dasta, J.F.; Davidson, J.E.; Devlin, J.W.; Kress, J.P.; Joffe, A.M.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 41, 263–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, B.; Talmy, T.; Gelikas, S.; Radomislensky, I.; Kontorovich-Chen, D.; Cohen, B.; Bar-Or, D.; Almog, O.; Glassberg, E. Opioid sparing effect of ketamine in military prehospital pain management-A retrospective study. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022, 93, S71–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, A.; Guarino, M.; Serra, S.; Spampinato, M.D.; Vanni, S.; Shiffer, D.; Voza, A.; Fabbri, A.; De Iaco, F. Low-Dose Ketamine for Pain Management. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Vlisides, P.E. Ketamine: 50 Years of Modulating the Mind. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K. Detrimental Side Effects of Repeated Ketamine Infusions in the Brain. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 1044–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Antunes, M.V.; Teles, D.; Pereira, L.G.; Abelha, F. Association between intraoperative ketamine and the incidence of emergence delirium in laparoscopic surgeries: an observational study. Braz. J. Anesthesiol. 2024, 74, 744414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viderman, D.; Aubakirova, M.; Nabidollayeva, F.; Yegembayeva, N.; Bilotta, F.; Badenes, R.; Thorat, A.A.; Yeseuleukova, S.; Baynazar, D.; Yerkinova, A.; et al. Effect of Ketamine on Postoperative Neurocognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenichev, I.; Burlaka, B.; Puzyrenko, A.; Ryzhenko, O.; Kurochkin, M.; Yusuf, J. Management of amnestic and behavioral disorders after ketamine anesthesia. Georgian Med. News 2019, 294, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Han, Y.; Que, B.; Zhou, R.; Gan, J.; Dong, X. Prophylactic Effects of Sub-anesthesia Ketamine on Cognitive Decline, Neuroinflammation, and Oxidative Stress in Elderly Mice. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Dou, X.; Yao, S.; Dong, X.; Luo, J. The Effect of Low-Dose Esketamine on Postoperative Neurocognitive Dysfunction in Elderly Patients Undergoing General Anesthesia for Gastrointestinal Tumors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2023, 17, 1945–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Park, J.S.; Lee, K.W.; Jeon, S.Y. Influence of Ketamine on Early Postoperative Cognitive Function After Orthopedic Surgery in Elderly Patients. Anesth. Pain Med. 2015, 5, e28844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, G.; Chan, M.T.V.; Combescure, C.; Lopez, U.; Pichon, I.; Licker, M.; Baele, P.; Bailie, R.; de Haever, G.; Ellerkmann, R.; et al. The international ENIGMA-II substudy on postoperative cognitive disorders (ISEP). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Hu, W.; Yang, J.; Yi, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, S. Effect of piracetam on the cognitive performance of patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery: A meta-analysis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 7, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belenichev, I.F.; Burlaka, B.S.; Ryzhenko, O.I.; Ryzhenko, V.P.; Aliyeva, O.G.; Makyeyeva, L.V. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic activity of the IL-1 antagonist RAIL-gel in rats after ketamine anesthesia. Pharmakeftiki 2021, 33, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Belenichev, I.; Popazova, O.; Bukhtiyarova, N.; Savchenko, D.; Oksenych, V.; Kamyshnyi, O. Modulating Nitric Oxide: Implications for Cytotoxicity and Cytoprotection. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenko, L.; Krishtafor, A.; Polinchuk, I.; Tiutiunnik, A.; Usenko, A.; Petrashenok, Y. Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction as a Complication of General Anesthesia. The Importance of Early Pharmacological Neuroprotection. EMERGENCY MEDICINE 2015, 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, L.; Bosco, M.; Rosario Ziello, A.; Rea, R.; Amenta, F.; Fasanaro, A.M. Effectiveness of nootropic drugs with cholinergic activity in treatment of cognitive deficit: a review. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012, 4, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, B.; Seibert, A.; Sperling, G.; Krieglstein, J. Vergleich der Wirkungen von Piracetam und Methohexital auf den zerebralen Energiestoffwechsel [Comparison of the effects of piracetam and methohexital on cerebral energy metabolism]. Arzneimittelforschung 1984, 34, 258–266. [Google Scholar]

- Belenichev, I.; Gorchakova, N.; Kuchkovskyi, O.; Ryzhenko, V.; Varavka, I.; Varvanskyi, P.; Levchenko, K.; Yusuf, J. Principles of metabolithotropic therapy in pediatric practice. Сlinical and pharmacological characteristics of modern metabolithotropic agents (part 2). Phytother. J. 2022, 4, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenichev, I.; Popazova, O.; Bukhtiyarova, N.; Ryzhenko, V.; Pavlov, S.; Suprun, E.; Tykhomyrov, A.; Zadoya, A.; Kaplaushenko, A.; Belenichev, I.; et al. Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cerebral Ischemia: Advances in Pharmacological Interventions. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarawagi, A.; Soni, N.D.; Patel, A.B. Glutamate and GABA Homeostasis and Neurometabolism in Major Depressive Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 637863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, S.; Hervig, M.-S. The 5-HT2A serotonin receptor in executive function: Implications for neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 64, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.A.; Bales, N.J.; Myers, S.A.; Bautista, A.I.; Roueinfar, M.; Hale, T.M.; Handa, R.J. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis: Development, Programming Actions of Hormones, and Maternal-Fetal Interactions. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 601939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Gentleman, S.M.; Leclercq, P.D.; Murray, L.S.; Griffin, W.S.; Graham, D.I.; Nicoll, J.A. The neuroinflammatory response in humans after traumatic brain injury. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2013, 39, 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suno, R.; Lee, S.; Maeda, S.; Yasuda, S.; Yamashita, K.; Hirata, K.; Horita, S.; Tawaramoto, M.S.; Tsujimoto, H.; Murata, T.; et al. Structural insights into the subtype-selective antagonist binding to the M2 muscarinic receptor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winblad, B. Piracetam: A Review of Pharmacological Properties and Clinical Uses. CNS Drug Rev. 2005, 11, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouhie, F.A.; Barbosa, K.O.; Cruz, A.B.R.; Wellichan, M.M.; Zampolli, T.M. Cognitive effects of piracetam in adults with memory impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2024, 243, 108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, J.J.; Price, G.W.; Jeffrey, P.; Deeks, N.J.; Stean, T.; Piper, D.; Smith, M.I.; Upton, N.; Medhurst, A.D.; Middlemiss, D.N.; et al. Characterization of SB-269970-A, a selective 5-HT(7) receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 130, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doré, A.S.; Okrasa, K.; Patel, J.C.; Serrano-Vega, M.; Bennett, K.; Cooke, R.M.; Errey, J.C.; Jazayeri, A.; Khan, S.; Tehan, B.; et al. Structure of class C GPCR metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 transmembrane domain. Nature 2014, 511, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MedKoo Biosciences [Internet]. fabomotizole dihydrochloride | CAS# 189638-30-0 (2HCl) | Anxiolytic | MedKoo; [cited 2025 Mar 17]. Available online: https://www.medkoo.com/products/32719 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Seymour, P.A.; Schmidt, A.W.; Schulz, D.W. The pharmacology of CP-154,526, a non-peptide antagonist of the CRH1 receptor: a review. CNS Drug Rev. 2003, 9, 57–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivy, D.; Palese, F.; Vozella, V.; Fotio, Y.; Yalcin, A.; Ramirez, G.; Mears, D.; Winder, D.G.; Cristino, L.; Piomelli, D.; et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors mediate the anxiolytic-like effects of monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition in a rat model of predator-induced fear. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Luo, T.; Jiang, X.; Wang, J. Anxiolytic effects of 5-HT₁A receptors and anxiogenic effects of 5-HT₂C receptors in the amygdala of mice. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Che, T.; Levit, A.; Shoichet, B.K.; Wacker, D.; Roth, B.L. Structure of the D2 dopamine receptor bound to the atypical antipsychotic drug risperidone. Nature 2018, 555, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Tice, C.M.; Singh, S.B. The use of spirocyclic scaffolds in drug discovery. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 3673–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, V.F.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Recent in vivo advances of spirocyclic scaffolds for drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2022, 17, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraja, D.; Doddamani, S.V.; Athira, C.S.; Siby, A.; Sreelakshmi, V.; Ancy, A.; Azeez, S.; Babu, T.S.; Manjula, S.N.; Rangappa, K.S.; et al. Spiro-heterocycles: Recent advances in biological applications and synthetic strategies. Tetrahedron 2025, 173, 134468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomoets, O.; Voskoboynik, O.; Antypenko, O.; Berest, G.; Nosulenko, I.; Palchikov, V.; Karpenko, O.; Andronati, S.; Kovalenko, S. Design, synthesis and anti-inflammatory activity of derivatives 10-R-3-aryl-6,7-dihydro-2H-[1,2,4]triazino[2,3-c]quinazolin-2-ones of spiro-fused cyclic frameworks. Acta Chim. Slov. 2017, 64, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodnyak, S.V.; Schabelnyk, K.P.; Аntypenko, O.M.; Кovalenko, S.I.; Palchykov, V.A.; Okovyty, S.I.; Shishkina, S.V. 5,6-Dihydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-с]quinazolines. Message 4. Spirocompounds with [1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolines moieties. Synthesis and spectral characteristics. J. Org. Pharm. Chem. 2016, 14, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodnyak, S.V.; Bukhtiarova, N.V.; Shabelnyk, K.P.; Berest, G.G.; Belenichev, I.F.; Kovalenko, S.I. Targeted search for anticonvulsant agents among spiroderivatives with 2-aryl-5,6-dihydro[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline fragment. Pharmacol. Drug Toxicol. 2016, 1(47), 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.H.; Oswald, R.E. Piracetam defines a new binding site for allosteric modulators of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2197–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimukai, H.; Kudo, T.; Tanaka, T.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K.; Takeda, M. Novel therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative disease. Psychogeriatrics 2009, 9, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Gan, J.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Z.X.; Cao, Y. CB-Dock2: Improved Protein-Ligand Blind Docking by Integrating Cavity Detection, Docking and Homologous Template Fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W159–W164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jędrejko, K.; Catlin, O.; Stewart, T.; Anderson, A.; Muszyńska, B.; Catlin, D.H. Unauthorized ingredients in "nootropic" dietary supplements: A review of the history, pharmacology, prevalence, international regulations, and potential as doping agents. Drug Test. Anal. 2023, 15, 803–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antypenko, L.; Shabelnyk, K.; Antypenko, O. Anxiolytic potential of 1-methyl/4-(tert-butyl)-2'-(cycloalkyl/hetaryl)-6'H-spiro[piperidine/cycloalkane-4,5'/1,5'-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolines]. In Proceedings of the VII International Scientific and Theoretical Conference "Scientific forum: theory and practice of research", Valencia, Spain, 31 January 2025; pp. 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko, O.O.; Sviatenko, L.K.; Shabelnyk, K.P.; Kovalenko, S.I.; Okovytyy, S.I. Reaction of [2-(3-hetaryl-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)phenyl]amines with ketones. DFT study. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2024, 143, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitmaier, E. Structure Elucidation by NMR in Organic Chemistry: A Practical Guide, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Antypenko, L.; Shabelnyk, K.; Antypenko, O.; Kovalenko, S.; Arisawa, M. In silico identification and characterization of spiro[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolines as next-generation diacylglycerol kinase α modulators. 2025, under submission.

- Banerjee, P.; Kemmler, E.; Dunkel, M.; Preissner, R. ProTox 3.0: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W513–W520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Li, N.; Liu, R.J.; Duric, V.; Aghajanian, G. Signaling pathways underlying the rapid antidepressant actions of ketamine. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanos, P.; Gould, T.D. Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystal, J.H.; Abdallah, C.G.; Sanacora, G.; Charney, D.S.; Duman, R.S. Ketamine: A Paradigm Shift for Depression Research and Treatment. Neuron 2019, 101, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Dudek, H.; Miranti, C.K.; Greenberg, M.E. Calcium influx via the NMDA receptor induces immediate early gene transcription by a MAP kinase/ERK-dependent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 5425–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, A.P.; Silva, C.G.; Marques, J.M.; Pochmann, D.; Porciúncula, L.O.; Ferreira, S.; Carvalho, A.R.; Canas, P.M.; Andrade, G.M.; Fontes-Ribeiro, C.A.; et al. Glutamate-induced and NMDA receptor-mediated neurodegeneration entails P2Y1 receptor activation. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrooz, A.B.; Nasiri, M.; Adeli, S.; Jafarian, M.; Pestehei, S.K.; Babaei, J.F. Pre-adolescence repeat exposure to sub-anesthetic doses of ketamine induces long-lasting behaviors and cognition impairment in male and female rat adults. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2024, 16, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, J. Mechanistic Insights into Neurotoxicity Induced by Anesthetics in the Developing Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 6772–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, C. Identifying c-fos Expression as a Strategy to Investigate the Actions of General Anesthetics on the Central Nervous System. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massara D., L.; Osuru, H.P.; Oklopcic, A.; Milanovic, D.; Joksimovic, S.M.; Caputo, V.; DiGruccio, M.R.; Ori, C.; Wang, G.; Todorovic, S.M.; et al. General Anesthesia Causes Epigenetic Histone Modulation of c-Fos and Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor, Target Genes Important for Neuronal Development in the Immature Rat Hippocampus. Anesthesiology 2016, 124, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidalgo, A.R.; Cibelli, M.; White, J.P.; Nagy, I.; Maze, M.; Ma, D. Systemic inflammation enhances surgery-induced cognitive dysfunction in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 498, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Li, Q.; Guo, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Guo, D.; Yang, H.; Yang, L. Ketamine induces hippocampal apoptosis through a mechanism associated with the caspase-1 dependent pyroptosis. Neuropharmacology 2018, 128, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, K.; Sun, L.; Bai, J.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, J. Laminin degradation by matrix metalloproteinase 9 promotes ketamine-induced neuronal apoptosis in the early developing rat retina. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2020, 26, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenichev, I.F.; Aliyeva, O.G.; Popazova, O.O.; Bukhtiyarova, N.V. Involvement of heat shock proteins HSP70 in the mechanisms of endogenous neuroprotection: the prospect of using HSP70 modulators. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1131683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahmandfar, M.; Akbarabadi, A.; Bakhtazad, A.; Zarrindast, M.R. Recovery from ketamine-induced amnesia by blockade of GABA-A receptor in the medial prefrontal cortex of mice. Neuroscience 2017, 344, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, A.; deGraaff, J.C. Anesthesia and Apoptosis in the Developing Brain: An Update. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2013, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisek, M.; Mackiewicz, J.; Sobolczyk, M.; Ferenc, B.; Guo, F.; Zylinska, L.; Boczek, T. Early Developmental PMCA2b Expression Protects From Ketamine-Induced Apoptosis and GABA Impairments in Differentiating Hippocampal Progenitor Cells. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 890827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, S.; Hashemi-Firouzi, N.; Afshar, S.; Asl, S.S.; Komaki, A. Protective Effects of 5-HT1A Receptor Inhibition and 5-HT2A Receptor Stimulation Against Streptozotocin-Induced Apoptosis in the Hippocampus. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 26, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Gardier, A.M. Fast-acting antidepressant activity of ketamine: highlights on brain serotonin, glutamate, and GABA neurotransmission in preclinical studies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 199, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frans, Ö.; Rimmö, P.A.; Ǻberg, L.; Fredrikson, M. Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2005, 111, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CB-Dock2. Cavity Detection Guided Blind Docking. Available online: https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/index.php (accessed on 07 January 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 5ZTY: Crystal structure of human G protein coupled receptor. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/5ZTY (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 6HUP: CryoEM structure of human full-length α1/β3/γ2L GABA(A)R in complex with diazepam (Valium), GABA and megabody Mb38. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6hup (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 5ZKB: Crystal structure of rationally thermostabilized M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor bound with AF-DX 384. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/5ZKB (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 6CM4: Structure of the D2 Dopamine Receptor Bound to the Atypical Antipsychotic Drug Risperidone. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6CM4 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 8FYX: Buspirone-bound serotonin 1A (5-HT1A) receptor-Gi1 protein complex. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8FYX (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 7XTC: Serotonin 7 (5-HT7) receptor-Gs-Nb35 complex. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7XTC (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 3LSX: Piracetam bound to the ligand binding domain of GluA3. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3LSX (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 4K5Y: Crystal structure of human corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 (CRF1R) in complex with the antagonist CP-376395. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/4K5Y (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- RCSB PDB - 4OO9: Structure of the human class C GPCR metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 transmembrane domain in complex with the negative allosteric modulator mavoglurant. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/4OO9 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Shabelnyk, K.; Fominichenko, A.; Antypenko, O.; Gaponov, O.; Kamyshnyi, O.; Belenichev, I.; Yeromina, H.; Antypenko, L.; Kovalenko, S. Antistaphylococcal triazole-based molecular hybrids: design, synthesis and activity. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProTox-II - Prediction Of Toxicity Of Chemicals. Available online: https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/index.php?site=home.-do (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- SwissADME. Available online: http://www.swissadme.ch/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Belenichev, I.; Bukhtiyarova, N.; Ryzhenko, V.; Makyeyeva, L.; Morozova, O.; Oksenych, V.; Ryzhenko, O.; Suprun, E.; Kamyshnyi, O. Methodological Approaches to Experimental Evaluation of Neuroprotective Action of Potential Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | Structural features | Mechanism of activity* | Pharmacological effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diazepam | benzodiazepine | GABA-A receptor positive allosteric modulator (α1/β3/γ2L) | sedative and muscle relaxant (anxiolytic) [26] |

| AFDX-384 | benzodiazepine | muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist (M2 and M4 subtypes) | treatment of dementia and schizophrenia [27] |

| Piracetam | pyrrolidine | AMPA receptor positive modulator and influences membrane fluidity, affecting ion transport and mitochondrial function | ootropic, used in cognitive impairment and myoclonus [28] |

| Pramiracetam | pyrrolidine | glutamate receptor 3 (GluA3) | nootropic stimulant [29] |

| SB-269970 | pyrrolidine | selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist | treatment of anxiety and depression and nootropic effects [30] |

| Mavoglurant | indole | antagonist of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) | obsessive-compulsive disorder [31] |

| Fabomotizole | benzimidazole | Selective MT3 (sigma-1) receptor ligand with anxiolytic properties | anxiolytic and neuroprotective agent [32] |

| CP-154,526 | pyrrolo[3,2-e]-pyrimidine | corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 (CRF1R) | treatment of alcoholism [33] |

| JWH-133 | tetrahydrobenzo[c]–chromene | cannabinoid (СВ2) receptor agonist, G protein coupled receptor | anxiolytic [34] |

| Buspirone | azaspiro[4.5]decane | serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist | anxiolytic (treat anxiety disorders) [35] |

| Risperidone | 1,2-benzoxazol; pyrido[1,2-a]–pyrimidine | 5-HT (5-HT2C, 5-HT2A) receptors antagonist, D2 dopamine receptor | antipsychotic, anxiolytic [36] |

| Sub. | Toxicity index* | LD50, mg/kg | Pred. acc., % | HT** | CG | IT | MG | CT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | IV | 2000 | 54.26 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.92 | 0.59 | 0.53 |

| 26 | 2000 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.95 | 0.61 | 0.53 | ||

| 31 | 1200 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.96 | 0.57 | 0.60/yes | ||

| 32 | 2000 | 0.76 | 0.53 | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.60/yes | ||

| 33 | 1200 | 0.76 | 0.53 | 0.99 | 0.61 | 0.60/yes | ||

| fabomotizole | 677 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.59/yes | ||

| piracetam | 2000 | 100 | 0.95 | 0.61 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 0.62/yes |

| Descriptors and properties | Compounds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 26 | 31 | 32 | 33 | piracetam | fabomotizole | |

| MW (Da) | 336.47 | 378.55 | 295.38 | 337.46 | 389.54 | 142.16 | 307.41 |

| n-ROTB | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| n-HBA | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| n-HBD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| TPSA | 42.74 | 42.74 | 45.98 | 45.98 | 45.98 | 63.40 | 75.68 |

| Consensus | 4.21 | 5.14 | 2.20 | 3.16 | 3.71 | -0.64 | 2.30 |

| Molar refractivity | 105.28 | 119.70 | 93.12 | 107.54 | 122.42 | 38.76 | 88.93 |

| Gastrointestinal absorption | high | ||||||

| Blood–brain barrier permeation | yes | no | yes | ||||

| Drug likeness | |||||||

| Lipinski (Pfizer); Muegge (Bayer); Ghose rules | yes | ||||||

| Veber (GSK) rules | yes | no/ MW<160, WLOGP<-0.4, MR<40 | yes | ||||

| Egan filter | no/ XLOGP3>5 | yes | no/MW<200 | yes | |||

| Lead-likeness | no | yes | no | yes | |||

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | ||||||

| Brenk alert, PAINS | no alerts | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).