1. Introduction

Naphthoquinones (NQs) are bioactive compounds structurally derived from naphthalene, and their numerous natural and synthetic derivatives have been extensively investigated for diverse biological effects and therapeutic potential. Among them, 1,4-NQs have attracted particular attention for their neuroprotective properties across various models of neurological disorders. Recently, a previous study has demonstrated that certain 1,4-NQ derivatives prevent Amyloid β (Aβ) aggregation, with their anti-Aβ activities being highly dependent on structural modifications [

1]. In addition, structural analogues of 1,4-NQs have been shown to alleviate motor deficits and inhibit apoptosis reducing oxidative stress in rotenone-induced Parkinsonism models [

2]. Moreover, synthetic vitamin K analogues, which are also 1,4-NQs, have been reported to reduce seizure activity in pentylenetetrazole-induced seizure models [

3]. Extending their pharmacological scope to ferroptosis regulation, fully reduced forms of vitamin K have been identified as potent ferroptosis inhibitors by scavenging lipid radicals in a glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)-independent manner in mouse hippocampal HT22 cells and brain tissues [

4].

Ferroptosis is a distinct, non-apoptotic form of regulated cell death characterized by the excessive accumulation of intracellular iron and lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS). It has been implicated in various acute and chronic central nervous system (CNS) disorders [

5]. During ferroptosis, iron overload amplifies lipid ROS generation, triggering extensive lipid peroxidation and cell death [

6,

7]. GPX4 plays a central antioxidant role by using glutathione (GSH) to detoxify lipid ROS, thereby protecting cells from ferroptotic damage [

8]. In addition, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) promotes the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), a key step in ferroptosis progression [

9]. GPX4-independent pathways also contribute to ferroptosis regulation; for example, ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) uses coenzyme Q10 to neutralize lipid radicals [

10,

11].

Recent transcriptomic and functional studies have identified the lysosomal cysteine protease cathepsin-B as an executive mediator of ferroptosis in the CNS. Elevated expression and activity of cathepsin-B have been observed under ferroptotic conditions both in vitro and in vivo [

12]. In HT22 neuronal cells, cathepsin-B promotes ferroptotic cell death by inducing lysosomal membrane permeabilization and enhancing lipid peroxidation, independently of GPX4 [

13]. In non-neuronal systems, cathepsin-B expression is regulated by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3); the ferroptosis inducer erastin has been shown to cause lysosomal dysfunction and cathepsin-B upregulation via aberrant STAT3 activation in pancreatic cancer cells [

14].

Additionally, N-cadherin, a classical cadherin and calcium-dependent adhesion molecule, has emerged as another modulator of ferroptosis. Under ferroptotic stress, N-cadherin degradation via autophagy reduces intercellular adhesion and increases susceptibility to cell death [

15]. Ke et al. [

16] also demonstrated that increased extracellular matrix stiffness decreases N-cadherin expression in nucleus pulposus cells, thereby enhancing lipid ROS, subsequent ferroptosis through upregulation of ACSL4.

Although several 1,4-NQ derivatives have been reported to regulate ferroptosis, 8-hydroxy-2-anilino-1,4-naphthoquinone (8-HANQ), which contains an aniline group on the 1,4-NQ backbone, has not been studied for its anti-ferroptotic neuroprotective effects or its underlying mechanisms. To address this, the present study aims to elucidate the neuroprotective role of 8-HANQ against ferroptosis in vitro and evaluate its potential anti-seizure effects in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Glutamate, RAS-selective lethal 3 (RSL3), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Iron(II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4), 3-(2-Pyridyl)-5,6-diphenyl-1,2,4-triazine-4′,4′′-disulfonic acid sodium salt (Ferrozine), Iron(III) sulfate (iron (III)), deferoxamine (DFO), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), ferrostatin-1, valproate, BGJ398 and C11-BODIPY581/591 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Antibodies against pSTAT3(Y705), STAT3, cathepsin-B, heme oxygenease-1 (HO-1), synapsin-1, N-cadherin, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA), pFGFR1(Y653/654) from Thermo Scientific (USA), postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) from SantaCruz (USA), FSP1 from Proteintech (USA), GPX4 from Abcam (USA) and ACSL4, PSD95 for HT22 cells from ABclonal Technology (USA). Kainate (KA) was purchased from MedChemExpress (USA).

2.2. NQ-Derived Compounds

2.2.1. 8-HANQ and 5-HANQ

2.2.1.1. General Chemistry

The reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich, USA; Thermo Fisher, USA; TCI, Japan) and used as provided, unless otherwise indicated. Reactions were monitored via analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using glass sheets pre-coated with silica gel 60 F254 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light (254 nm). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H NMR) spectra of the compounds dissolved in CDCl₃ and deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d₆) were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, USA). Chemical shifts were expressed as δ-values in parts per million (ppm) using residual solvent peaks (CDCl₃: ¹H, 7.26 ppm; DMSO: ¹H, 2.50 ppm) as a reference. Coupling constants are given in hertz (Hz). Peak patterns are indicated by the following abbreviations: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quadruplet; m, multiplet. HRMS was performed on a system consisting of an electrospray ionization (ESI) source in an Agilent 6230B time-of-flight (TOF) liquid chromatography–mass spectrometer equipped at the Ewha Drug Development Research Core Center (Agilent Technologies, USA; NFEC-2021-08-272459). Column chromatography was performed using silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh). The purity of the final compounds was determined by HPLC on an Agilent 1260 system (Agilent Technologies) using an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 µm) with UV absorbance detection at 254 nm. HPLC conditions were as follows: mobile phase, ACN/Water (60:40); flow rate, 1.0 mL/min; column temperature, ambient; injection volume, 10 μL. All compounds were >95% pure by HPLC analysis.

2.2.1.2. Synthesis

A solution of Juglone (200 mg, 1.1 mmol, 1 equiv.) and AlCl₃(0.1 mmol, 0.1 equiv.) in ethanol (11 mL) was stirred at room temperature under dark conditions. Aniline (1.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was then added, and the resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h. After the reaction was complete, the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate and washed with brine. The organic phase was collected, dried over anhydrous MgSO₄, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using a gradient elution of hexane and ethyl acetate (30:1 to 20:1), yielding an orange-red compound (8-HANQ; 42 mg, 11% yield) and a dark red compound (5-Hydroxy-2-(phenylamino)naphthalene-1,4-dione, 5-HANQ; 5 mg, 2% yield)

[17].

8-HANQ (compound #1) : Orange red solid;

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 11.53 (s, 1H), 9.27 (s, 1H), 7.74 (q,

J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t,

J = 4.0 Hz, 3H), 7.38 (d,

J = 4.3 Hz, 2H), 7.27-7.21 (m, 2H), 6.04 (s, 1H);

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 11.56 (s, 1H), 7.65-7.62 (m, 2 H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 7.43 (t,

J = 3.2 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (d,

J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.24-7.17 (m, 2H), 6.38 (s, 1H); The NMR data are identical to the previously reported data [

17] ;

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 185.57, 181.89, 160.48, 146.27, 137.95, 137.55, 132.95, 129.32, 125.41, 123.89, 122.26, 117.60, 114.33, 102.14); HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C

16H

12NO

3 [M+H]

+ : 266.0812; found : 266.0812. HPLC purity : 99.8%.

5-HANQ (compound #2) : Dark red solid;

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 13.06 (s, 1H), 9.60 (s, 1H), 7.66 (t,

J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d,

J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t,

J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (d,

J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d,

J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (t,

J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.00 (s, 1H); The NMR data are identical to the previously reported data [

18];

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 189.05, 180.84, 160.00, 147.49, 137.62, 134.72, 130.57, 129.37, 125.84, 125.10, 124.06, 118.77, 114.27, 100.58; HRMS (ES+) m/z calculated for C

16H

12NO

3 [M+H]

+ : 266.0812; found : 266.0811. HPLC purity : 96.4%.

2.2.2. Other NQ-Derived Compounds

NQ-derived analogs, 6-anilino-5,8-quinolinedione (compound #3; [

19]), 2,3-dimethyl-6-(3,5-difluoroanilino)-5,8-quinoxalinedione (compound #4), 2,3-dimethyl-6-(3-fluoroanilino)-5,8-quinoxalinedione (compound #5), and 2,3-dimethyl-6-(4-ethoxyanilino)-5,8-quinoxalinedione (compound #6) [

20], were included in the initial compound screening and these 4 compounds were provided by Prof. Chung-Kyu Ryu.

2.3. HT22 Mouse Hippocampal Cell Culture

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator under 5% CO₂ and subcultured every 2-3 days using trypsin/EDTA solution.

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was assessed using the Quanti-Max™ WST-8 Cell Viability Assay Kit (Biomax, Korea), following the manufacturer's protocol. HT22 cells were placed in 96-well plates and pre-treated with varying concentrations of each test compound including 8-HANQ (0.01-10 μM), 5-HANQ (10 μM), BGJ398 (1-5 nM) or ferrostatin-1 (1 μM) for 30 minutes and subsequently exposed to cytotoxic agents such as a combination of 5 mM glutamate and 100 μM iron (III), 50 nM RSL3 or 20 mM glutamate at 37 °C for 24 hours. To test toxicity of 8-HANQ and 5-HANQ, both compounds (10-100 μM) were treated to HT22 cells and incubated for 24 hours. WST-8 reagent was added and incubated for 1 hour in the dark and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Tecan Infinite 200 PRO microplate reader (Tecan, Switzerland; NFEC-2024-09-299675) at the Ewha Drug Development Research Core Center.

2.5. Lipid ROS Detection with C11-BODIPY581/591

HT22 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and pretreated with 8-HANQ or 5-HANQ (5-10 μM) for 30 minutes, followed by stimulation with either 30 mM glutamate or 200 nM RSL3 for 24 hours. Cells were then fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature and stained with 1.5 μM C11-BODIPY581/591 at 37 °C for 30 minutes in the dark. After washing, cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and analyzed by flow cytometry NovoCyte 2060R system (ACEA Biosciences, USA; NFEC-2019-03-254735). Fluorescence data from 100,000 events were recorded per sample. For fluorescence imaging, cells stained with 1.5 μM C11-BODIPY581/591 for 30 minutes were washed thoroughly with PBS and visualized using an Axio Observer 7 inverted fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany; NFEC-2021-08-272462). All flow cytometric and fluorescence imaging analyses were conducted at the Ewha Drug Development Research Core Center.

2.6. Ferrous Iron Chelation Assay

Ferrous iron binding capacity of 8-HANQ was measured by the ferrozine-based colorimetric assay, as described by Soriano-Castell et al. [

21]. Briefly, 8-HANQ (1-200 μM) was incubated with 5 μM FeSO4 in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) for 2 minutes at room temperature in a 96-well plate, followed by the addition of 2.5 mM ferrozine. Absorbance at 562 nm was measured using a microplate reader. Each dose was tested in duplicate and iron binding capacities are presented as vehicle controls with or without iron.

2.7. Measurement of Soluble N-cadherin Release

soluble N-cadherin was quantified as previously described by Nitsch et al. [

22], with slight modifications. Briefly, cells were incubated in 6-well plates overnight, followed by treatment with 8-HANQ (2.5-10 μM) for 30 minutes prior to the addition of 200 nM RSL3. After 24 hours, culture media were collected, centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 minutes with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail and subsequently the supernatants were desalted using PD-10 desalting columns (Cytiva, USA). The desalted solution from the columns was dried using a speed vacuum evaporator ScanSpeed 40 (Alex Red Ltd, Israel) and resuspended in 20 μl of loading buffer. Equal volumes of each sample were separated with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and probed with anti-N-cadherin primary antibody overnight. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 hours, immunoactive bands were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents and detected with a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad, USA). Band intensities were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, USA).

2.8. Animal Experiments

2.8.1. Animals

Male ICR mice (25-30 g) were obtained from Orient Bio (Korea) and housed under a 12/12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to standard chow and water. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Ewha Womans University (approval number: Ewha-IACUC 23-061-4) and conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

2.8.2. Stereotaxic Drug Administration and KA-Induced Seizure Induction

For intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration, mice were anesthetized with tiletamine-zolazepam (Zoletil, 20 mg/kg) and xylazine (9.5 mg/kg) and positioned in a stereotaxic frame. Injections were performed using a Hamilton microsyringe at the following stereotaxic coordinates relative to bregma: anteroposterior -1.0 mm, mediolateral ±1.0 mm, and dorsoventral -2.0 mm. Animals received a 1 μl injection of either 8-HANQ (0.5 or 1 μg), valproate (150 μg), or vehicle (40 or 80% DMSO in saline) with/without KA (0.2 μg).

Mice were intraperitoneally or intracerebroventricularly administered KA, as previously described by Rusina et al. [

23]. In the intraperitoneal (i.p.) KA administration experiment, animals were randomly divided into four groups. The vehicle control group received an i.c.v. injection of vehicle 2 hours prior to an i.p. injection of saline. The KA group received vehicle i.c.v., followed 2 hours later by KA (40 mg/kg, i.p.). The KA + 8-HANQ group was administered 8-HANQ (0.5 or 1 μg, i.c.v.), and the KA + valproate group received valproate (150 μg, i.c.v.), both 2 hours before KA injection.

In the i.c.v. KA administration experiment, a separate cohort of animals was randomly assigned into three groups. In this scheme, KA was co-administered with 8-HANQ via i.c.v. injection. The vehicle control group received an i.c.v. injection of vehicle (40% DMSO in 1 μl saline). The KA group received a mixture of KA (0.2 μg) and vehicle (in 1 μl total volume). The KA + 8-HANQ group was administered a combination of KA (0.2 μg) and 8-HANQ (1 μg) in a total volume of 1 μl. All animals were sacrificed 72 hours after KA administration.

2.8.3. Behavioral Seizure Assessment

To evaluate the anti-seizure effects of 8-HANQ in a KA-induced seizure model, mice were monitored every 10 minutes for 150 minutes by observers blinded to the treatment conditions. Behavioral seizure severity was scored between 30 and 180 minutes following systemic administration of KA. In the i.c.v. KA administration model, seizure behavior was evaluated from 60 to 210 minutes after i.c.v. injection of 8-HANQ and KA, as mice recovered from anesthesia approximately 60 minutes post-injection. Seizure severity was assessed using a modified Racine scale [

24], as follows: Stage 0, no behavioral changes; Stage 1, facial muscle clonus; Stage 2, head nodding; Stage 3, forelimb clonus; Stage 4, rearing and falling with fore-limb clonus; Stage 5, generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

2.9. Sample Preparation and Western Blot Analysis

HT22 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with 8-HANQ (2.5-20 μM) or BGJ398 (10-100 nM) for 30 minutes and then co-treated with 30 mM glutamate, 200 nM RSL3, or combinations of 10/20 mM glutamate or 100 μM arachidonate and 25/100 μM iron (III) for designated times. For in vivo analysis, mice were sacrificed 72 hours after KA administration. Cells and brain hippocampal tissues were lysed in cold RIPA buffer containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4 °C, protein concentrations were determined using a protein quantification kit - BCA (Biomax, Korea). Equal protein amounts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in 0.1% TBST and incubated overnight with primary antibodies and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence. Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis were performed using unpaired t-tests, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test, or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc correction, as appropriate. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.11. Generative AI Assistance in Manuscript Preparation

Generative AI tools, specifically OpenAI’s ChatGPT (USA), were partially used to assist in the literature review and revision of the original manuscript. All AI-assisted content was carefully reviewed and edited by the authors to ensure accuracy.

4. Discussion

Due to their structural versatility, 1,4-NQ derivatives exert diverse biological effects on ferroptosis in both cancer and neuronal systems [

1,

4,

35,

36]. However, the role of 8-HANQ in ferroptosis has not been investigated, and no notable function has been described in the neuronal system. To date, only one prior study reported a negligible anti-Aβ aggregation effect of 8-HANQ in a cell-free assay [

17], without subsequent evaluation in disease-relevant models.

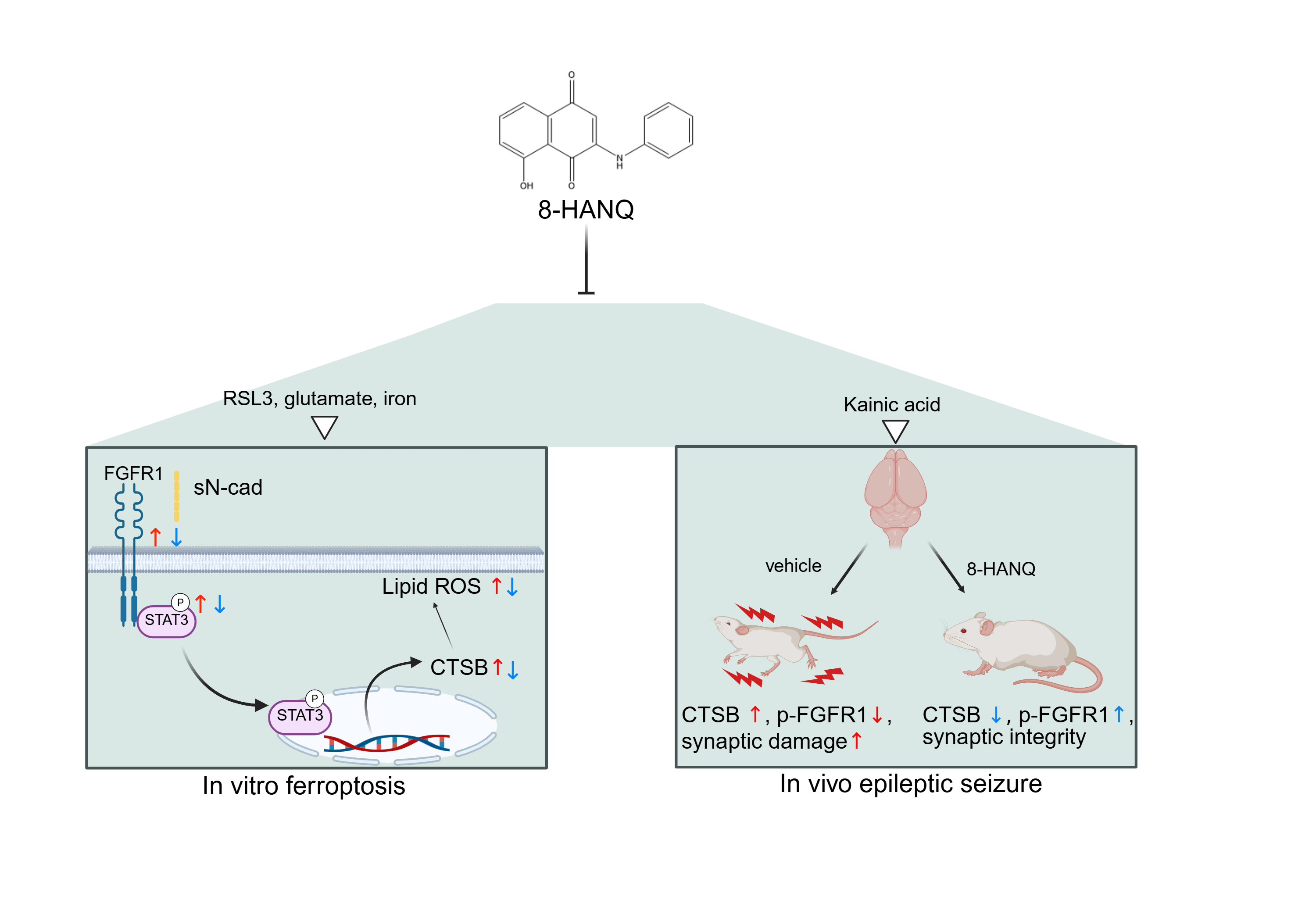

In the present study, we demonstrated that 8-HANQ attenuates neuronal ferroptosis in vitro, potentially by suppressing aberrant STAT3/cathepsin-B activation downstream of soluble N-cadherin/FGFR1 signaling in hippocampal neurons. Furthermore, in a KA-induced seizure model, 8-HANQ reduced seizure severity in vivo, underscoring the translational relevance of this mechanism.

We first evaluated the anti-ferroptotic effects of 8-HANQ under ferroptotic conditions induced by glutamate alone, glutamate combined with iron, and GPX4 inhibition by RSL3. Given the multifactorial nature of ferroptosis [

37], we newly established a combined subtoxic glutamate and iron model, which synergistically elicited ferroptotic stress by simultaneously inhibiting system Xc⁻ and promoting iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. 8-HANQ dose-dependently prevented HT22 neuronal death across all conditions, in association with reduced lipid ROS accumulation. Moreover, 8-HANQ markedly suppressed aberrant ACSL4 upregulation, which facilitates PUFA oxidation and subsequent lipid peroxidation [

9].

Despite these robust protective effects, 8-HANQ did not restore GPX4 protein levels under RSL3-induced stress. Because vitamin K derivatives, which also share a 1,4-NQ core, suppress ferroptosis via the GPX4-independent FSP1 pathway in HT22 cells [

4], we next examined FSP1 involvement. However, 8-HANQ failed to restore FSP1 levels suppressed by arachidonate plus iron (III), another ferroptosis-inducing condition [

38]. In addition, HO-1, whose overexpression aggravates ferroptosis through iron dysregulation [

37], remained unaffected by 8-HANQ, and the compound exhibited no iron-chelating activity (

Supplementary Figure 4). Together, these findings suggest that 8-HANQ exerts its protective effects through mechanisms distinct from canonical ferroptosis regulators such as GPX4, FSP1, or iron-handling pathways.

Instead, 8-HANQ suppressed pSTAT3 and cathepsin-B overactivation under both glutamate- and RSL3-induced ferroptosis. cathepsin-B upregulation has been consistently observed during ferroptosis across diverse cell types [

12,

13,

39]. Concomitant induction of pSTAT3 and cathepsin-B has also been reported in pancreatic cancer cells undergoing ferroptosis [

14], consistent with our findings in neuronal HT22 cells. Although STAT3 signaling in ferroptosis is context-dependent [

40], growing evidence suggests a pro-ferroptotic role of pSTAT3 in CNS disorders. For example, activation of the STAT3/HIF1α axis promoted α-synuclein-induced ferroptosis, with GPX4 suppression and iron dyshomeostasis in a Parkinson’s disease model, whereas pharmacological STAT3 inhibition reduced lipid ROS and iron accumulation in microglia [

41]. Likewise, traumatic brain injury-induced IL-23 upregulation enhanced neuronal ferroptosis through STAT3 activation, while IL-23 neutralization attenuated ferroptosis, restored GPX4 and ACSL4 expression, and normalized STAT3 overactivation [

42]. Compared with these reports, our results indicate that 8-HANQ normalizes STAT3/cathepsin-B overactivation while restoring ACSL4 and reducing lipid ROS, but without altering GPX4 levels or iron homeostasis in ferroptosis-induced HT22 neuronal cells.

The autophagic degradation of N-cadherin has recently been identified in cancer cell lines as a mechanism of ferroptosis, mediated by the selective cargo protein hippocalcin-like 1 (HPCAL1) and operating independently of GPX4 regulation or iron metabolism [

15]. Given that 8-HANQ attenuated LC3-II accumulation under ferroptotic stress, its anti-ferroptotic actions may be associated with suppression of autophagy-dependent ferroptosis, which led us to investigate N-cadherin protein level. However, intracellular levels of full-length N-cadherin and HPCAL1 remained unchanged (

Supplementary Figure 2), despite decreased GPX4 level and dysregulated iron metabolism (

Figure 4 and

Supplementary Figure 4) under our ferroptotic conditions. These results indicated that HPCAL1-mediated N-cadherin degradation is not involved in neuronal ferroptosis. Instead, we observed a robust secretion of soluble N-cadherin, which has been reported to activate FGFR1 signaling and promote neurite outgrowth in cerebellar neurons [

27]. Consistent with this interaction, our data demonstrated FGFR1 activation concomitant with elevated soluble N-cadherin under ferroptotic stress, an effect that was significantly inhibited by 8-HANQ. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that soluble N-cadherin may act as an upstream modulator of FGFR1/STAT3/cathepsin-B axis, thereby driving pathological STAT3/cathepsin-B activation during neuronal ferroptosis. Likewise, although arising from distinct cellular contexts, aberrant FGFR1/STAT3 activation has been shown to trigger cell death in breast cancer cells [

43]. Importantly, we newly found that 8-HANQ inhibits ferroptosis-induced soluble N-cadherin secretion and STAT3/cathepsin-B activation, together with its anti-ferroptotic neuroprotective effect, in a manner similar to BGJ398, an FGFR1 inhibitor. Collectively, our findings suggest that prevention of the soluble N-cadherin-mediated FGFR1 activation, and the subsequent STAT3/cathepsin-B overactivation may represent a possible mechanism underlying the anti-ferroptotic neuroprotective effects of 8-HANQ in vitro.

Previous reports have demonstrated anti-seizure effect of certain 1,4-NQ derivatives in pentylenetetrazole-induced [

3] and electroshock-induced seizures [

44]. In addition, although there have been no reports in epilepsy or seizure models, the 1,4-NQ derivative, plumbagin, was recently shown to exert its neuroprotective effects in the hippocampus of autism models, ameliorating cognitive dysfunction [

45].

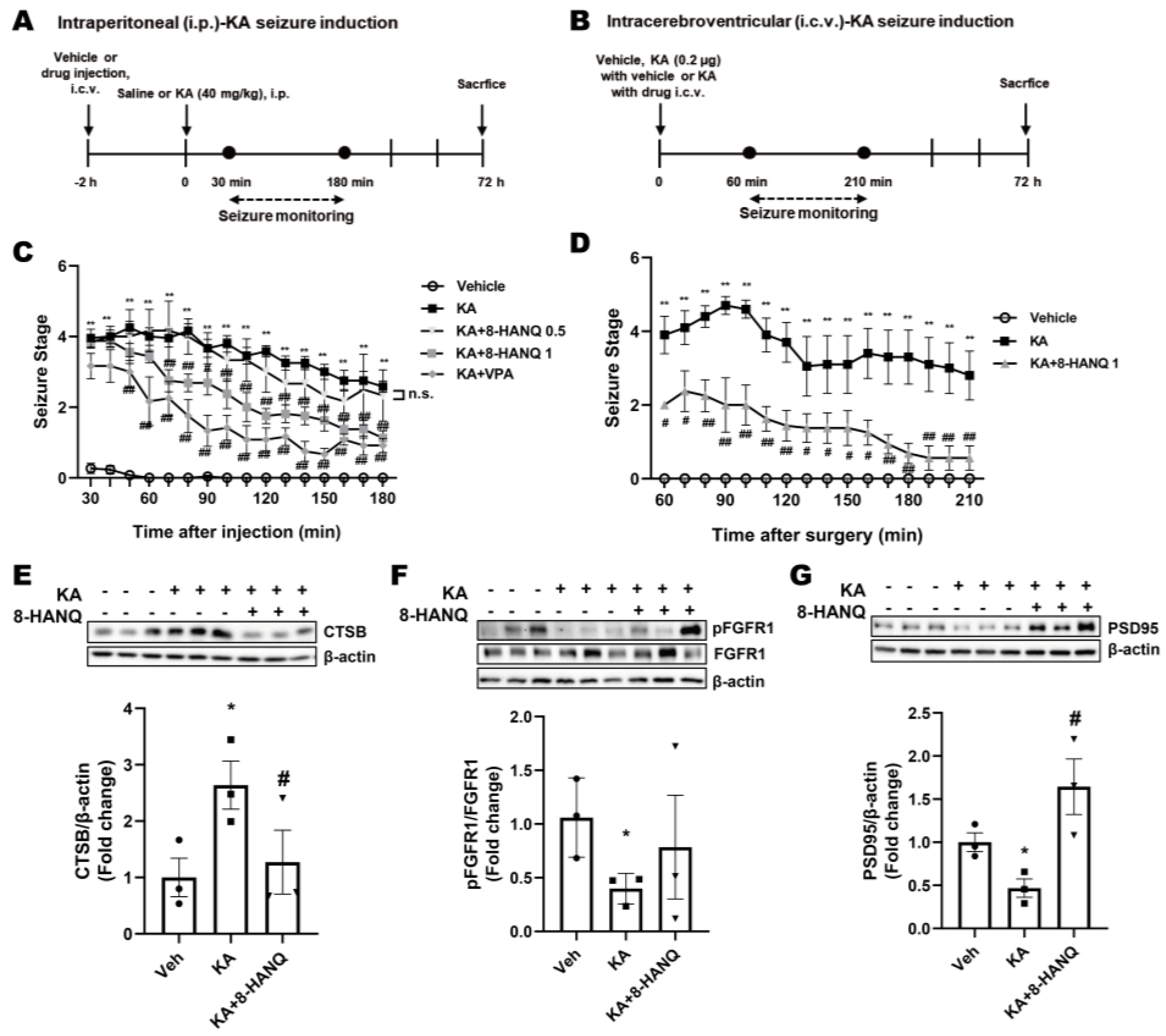

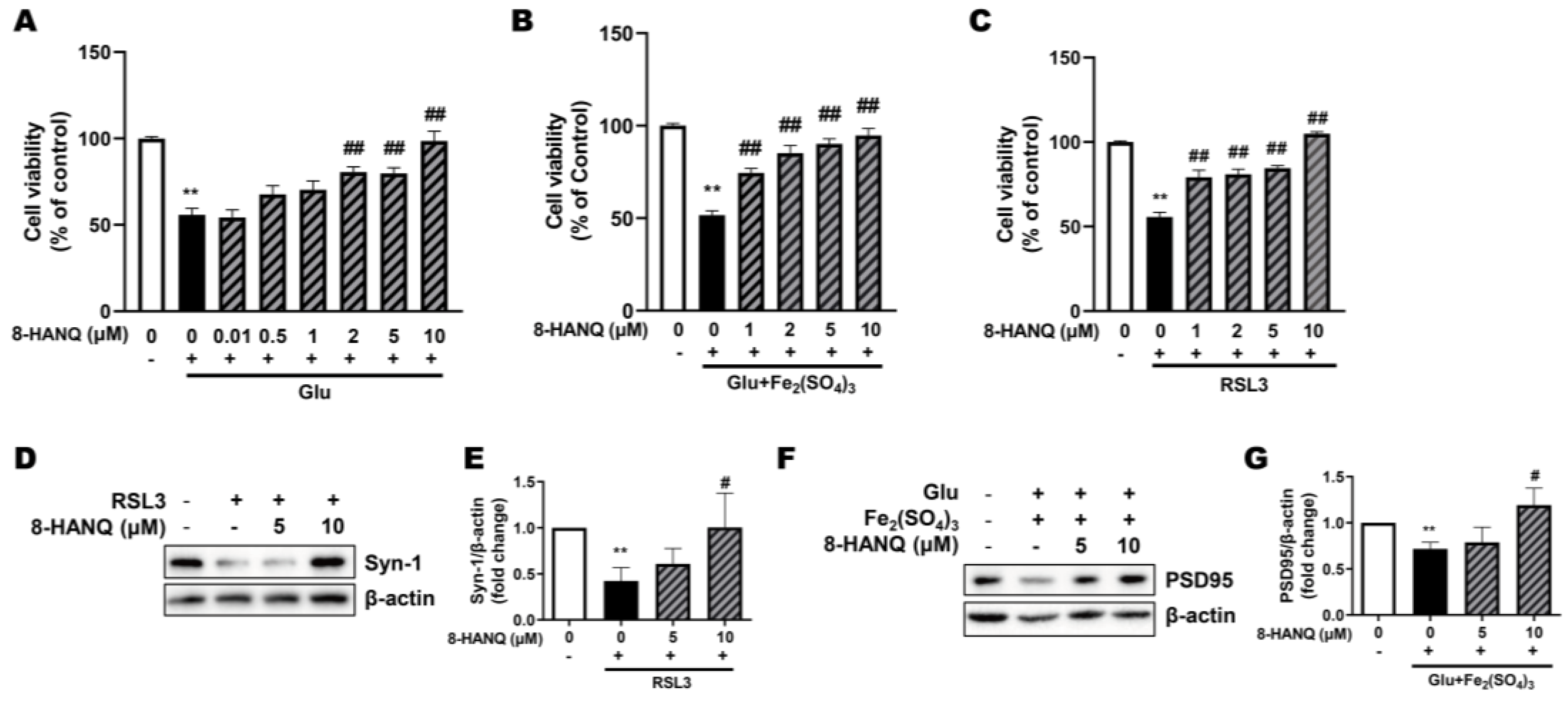

To date, the potential effects of 1,4-NQ derivatives on seizure behavior in the context of neuroprotection against ferroptosis have not been investigated in vivo seizure models. In our in vitro neuronal ferroptosis model, synaptic dysfunction, as indicated by PSD95 reduction, was recovered by 8-HANQ. Consistent with this observation, 8-HANQ attenuated hippocampal PSD95 loss in parallel with its antiseizure effect in KA-induced epileptic mice. PSD95 has been reported to decline progressively as epilepsy advances. Previous studies indicated that no significant changes were detected 24 hours after KA exposure [

46], whereas a marked reduction was observed at one week in electrically induced seizures [

47] and at six weeks after KA injection [

48], indicating chronic synaptic impairment in epilepsy. In line with these reports, we observed PSD95 reduction at 72 hours after KA injection, which was mitigated by 8-HANQ treatment.

In the KA models, 8-HANQ also attenuated seizure severity while modulating cathepsin-B levels, suggesting a potential relationship with ferroptotic processes. HO-1, a ferroptosis marker protein, was upregulated in hippocampal tissues from both intraperitoneal and intracerebroventricular KA-induced epileptic mice, which were anesthetized prior to vehicle or drug injection. In contrast, significant changes in GPX4 and ACSL4 were not detected in the same epileptic mice (unpublished data and

Supplementary Figure 3). This absence of alteration suggests incomplete ferroptotic activation, possibly due to anesthetic interference, as ketamine, mechanistically related to tiletamine, has been reported to suppress neuronal ferroptosis [

49]. Nonetheless, 8-HANQ reduced epileptic behavior while attenuating KA-induced cathepsin-B upregulation in the hippocampus, consistent with its anti-ferroptotic actions observed in vitro. Previous studies have shown that cathepsin-B is elevated following KA-induced seizures [

34] and that it promotes ferroptosis in HT22 cells, where its inhibition alleviates ferroptotic death independently of GPX4 [

13]. By integrating these observations, the present study provides an evidence for a potential link between cathepsin-B and ferroptosis in the context of epileptic seizures.

Previously, it has been demonstrated that KA-induced seizures activate STAT3 in association with glutamate excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation three days post-injection, and that a traditional herbal formula restored these pathological changes [

50]. Based on these findings, we assessed STAT3 signaling in the KA-exposed hippocampus. However, significant alterations in pSTAT3 were not observed in the KA-induced hippocampus (

Supplementary Figure 3), limiting interpretation of its contribution to the in vivo effects of 8-HANQ.

In parallel, hippocampal FGFR1 signaling was also affected by seizure induction. At 72 hours after KA injection, pFGFR1/FGFR1 ratios declined and were partially restored by 8-HANQ. These findings contrast with our in vitro data and earlier reports showing FGFR1 upregulation within 24 hours of KA-induced seizures [

51]. To date, FGFR1 signaling has not yet been examined in chronic epilepsy. Our results suggest that FGFR1 signaling downregulation may be indicative of progressive synaptic deterioration, whereas partial recovery by 8-HANQ treatment may contribute to neuroprotection.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that 8-HANQ mitigates neuronal ferroptosis, likely involving the FGFR1/STAT3/cathepsin-B axis rather than the canonical GPX4 or FSP1 defense systems. The reduction of lipid ROS and aberrant FGFR1/STAT3/cathepsin-B activation in vitro, together with the alleviation of synaptic deficits and seizure behaviors in vivo, provides preliminary support for a previously underexplored regulatory mechanism of ferroptosis associated with 8-HANQ. Taken together, these results raise the possibility that 8-HANQ may help control ferroptosis-related neuronal death and seizures.

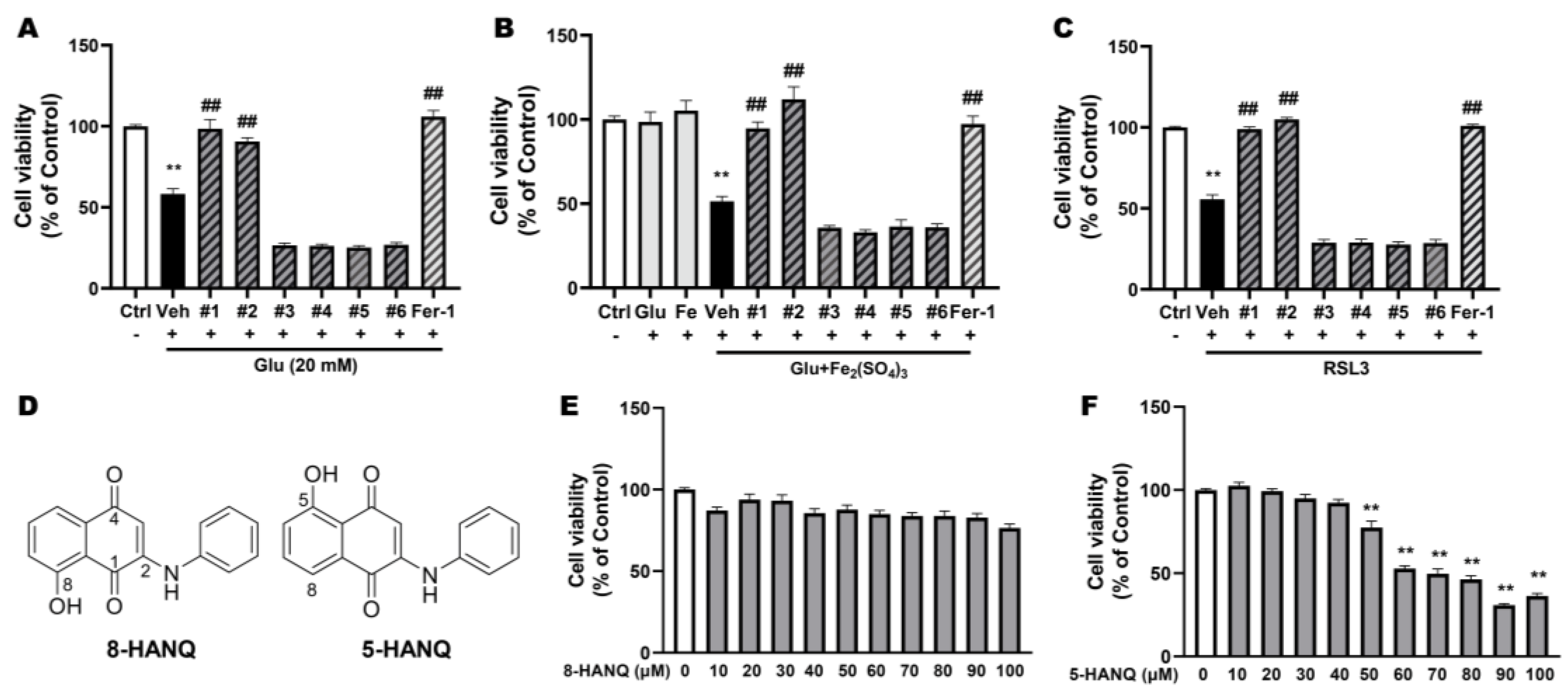

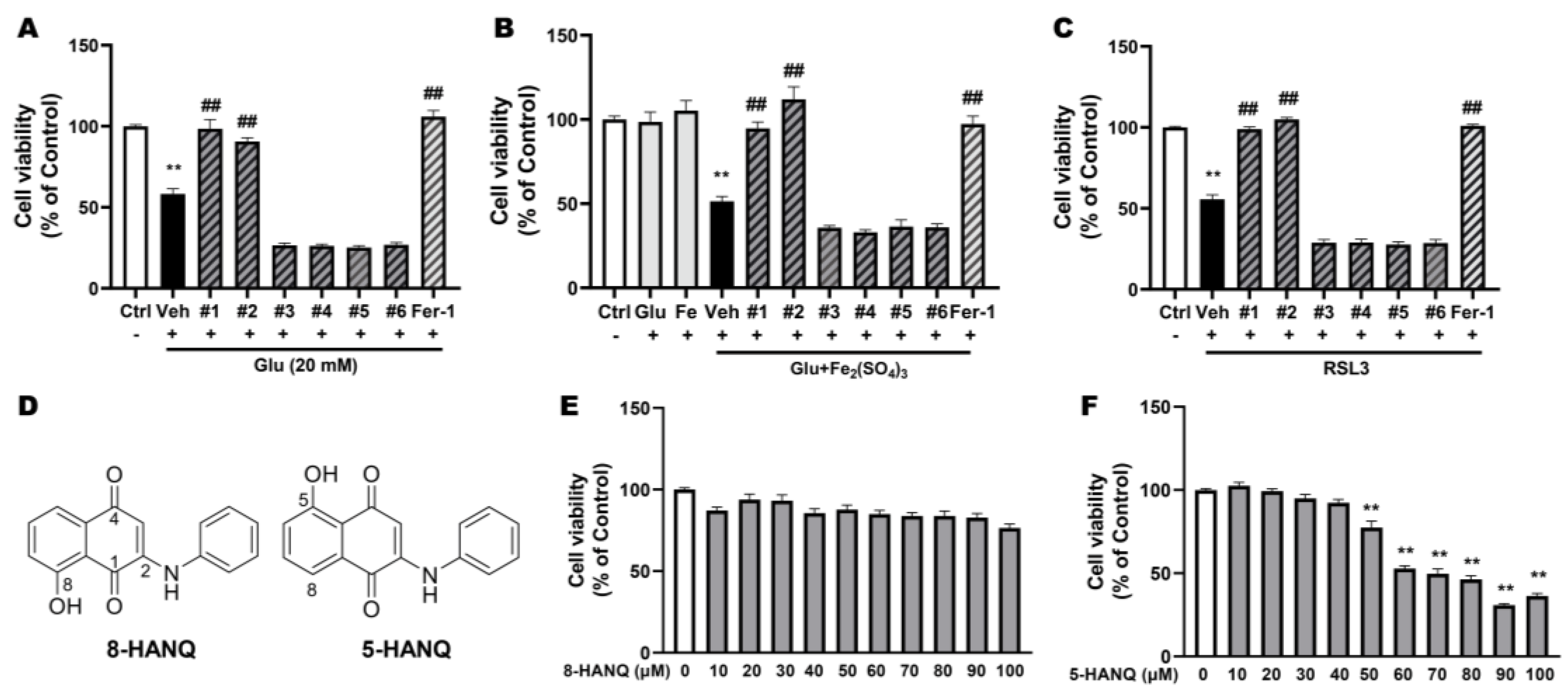

Figure 1.

Selection of novel NQ derivatives preventing ferroptotic neuronal death (A-C) Cell viability was assessed using the WST-8 assay to identify candidate for ferroptosis inhibitors. HT22 cells were pretreated with 10 μM of various NQ derivatives (compound #1-6) or 1 μM ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) for 30 min, followed by co-treatment with 20 mM glutamate (Glu; A, n=4), 5 mM Glu and 100 μM iron (III) sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃) (B, n=4) or 50 nM RSL3 (C, n=6) for 24 h. Fer-1 was used as positive control. (D) Chemical structures of 8-HANQ (compound #1) and 5-HANQ (compound #2). (E-F) Cytotoxicity of 8-HANQ (E, n=6) and 5-HANQ (F, n=4) was evaluated in the absence of ferroptosis inducers. HT22 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (10-100 μM) of each compound for 24 h, and viability was measured using the WST-8 assay. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as means ± SEM. (**p < 0.01 vs. Control (Ctrl, 0) ; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Glu, Glu+Fe₂(SO₄)₃, RSL3). n indicates independent experiments.

Figure 1.

Selection of novel NQ derivatives preventing ferroptotic neuronal death (A-C) Cell viability was assessed using the WST-8 assay to identify candidate for ferroptosis inhibitors. HT22 cells were pretreated with 10 μM of various NQ derivatives (compound #1-6) or 1 μM ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) for 30 min, followed by co-treatment with 20 mM glutamate (Glu; A, n=4), 5 mM Glu and 100 μM iron (III) sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃) (B, n=4) or 50 nM RSL3 (C, n=6) for 24 h. Fer-1 was used as positive control. (D) Chemical structures of 8-HANQ (compound #1) and 5-HANQ (compound #2). (E-F) Cytotoxicity of 8-HANQ (E, n=6) and 5-HANQ (F, n=4) was evaluated in the absence of ferroptosis inducers. HT22 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (10-100 μM) of each compound for 24 h, and viability was measured using the WST-8 assay. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as means ± SEM. (**p < 0.01 vs. Control (Ctrl, 0) ; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Glu, Glu+Fe₂(SO₄)₃, RSL3). n indicates independent experiments.

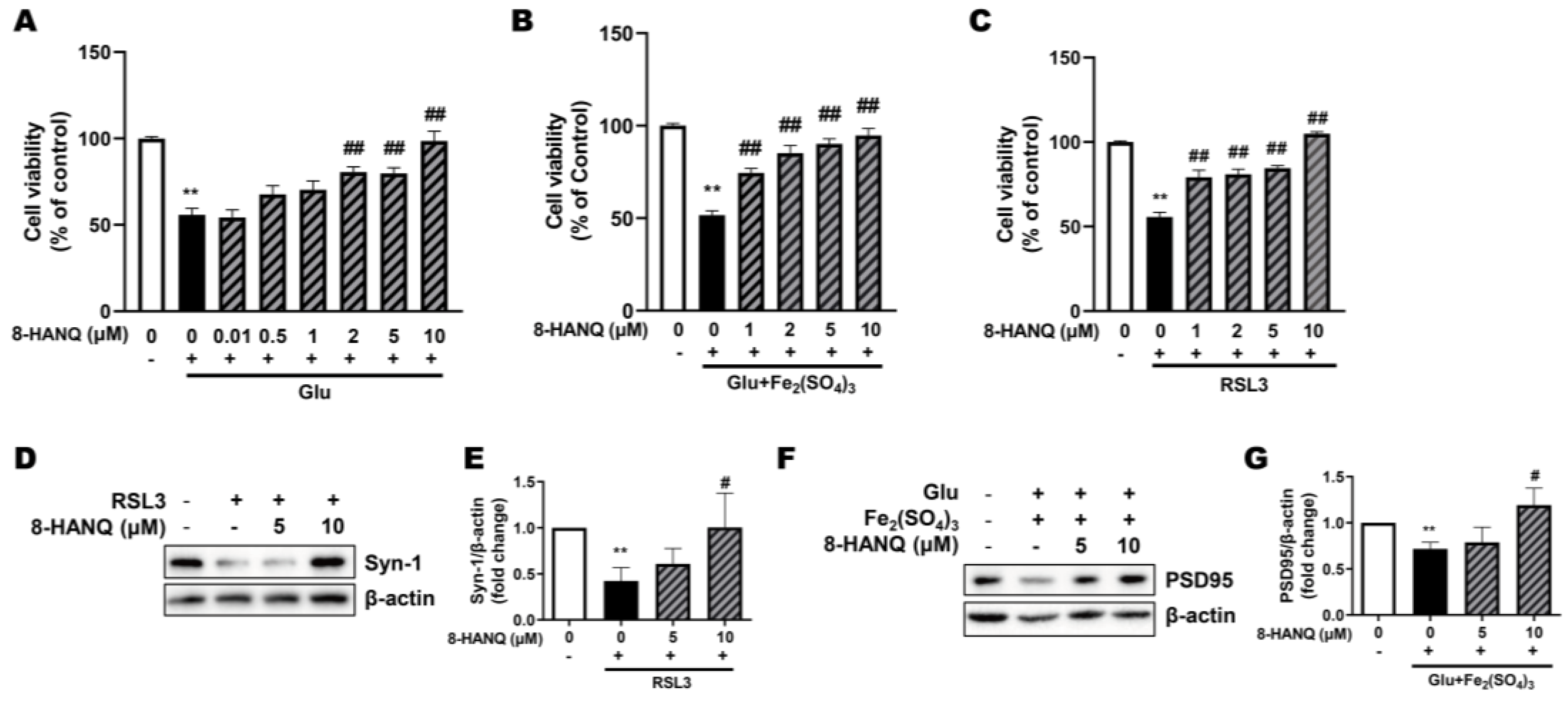

Figure 2.

Protection against ferroptosis and preservation of synaptic proteins by 8-HANQ (A-C) Dose-dependent neuroprotective effects of 8-HANQ were assessed in toxic concentration of glutamate- (Glu; A, n=5), subtoxic combination of Glu and iron (III) sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃)- (B, n=6), and RSL3- (C, n=4) induced ferroptosis models. 8-HANQ (0.01-10 μM) was applied 30 min prior to treatment with 20 mM Glu, 5 mM Glu and 100 μM Fe₂(SO₄)₃ or 50 nM RSL3 and incubated for 24 h. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. (D-G) Western blot analysis and quantification of synaptic markers including synapsin-1 (Syn-1; D-E, n=4) and PSD95 (F-G, n=6) expression. Cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (5-10 μM) or for 30 min following co-treatment with 200 nM RSL3 or 20 mM Glu and 25 μM Fe₂(SO₄)₃ for 24 h. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. (**p < 0.01 vs. Control (0) ; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Glu, RSL3, Glu+Fe₂(SO₄)₃). n indicates independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Protection against ferroptosis and preservation of synaptic proteins by 8-HANQ (A-C) Dose-dependent neuroprotective effects of 8-HANQ were assessed in toxic concentration of glutamate- (Glu; A, n=5), subtoxic combination of Glu and iron (III) sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃)- (B, n=6), and RSL3- (C, n=4) induced ferroptosis models. 8-HANQ (0.01-10 μM) was applied 30 min prior to treatment with 20 mM Glu, 5 mM Glu and 100 μM Fe₂(SO₄)₃ or 50 nM RSL3 and incubated for 24 h. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. (D-G) Western blot analysis and quantification of synaptic markers including synapsin-1 (Syn-1; D-E, n=4) and PSD95 (F-G, n=6) expression. Cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (5-10 μM) or for 30 min following co-treatment with 200 nM RSL3 or 20 mM Glu and 25 μM Fe₂(SO₄)₃ for 24 h. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. (**p < 0.01 vs. Control (0) ; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Glu, RSL3, Glu+Fe₂(SO₄)₃). n indicates independent experiments.

Figure 3.

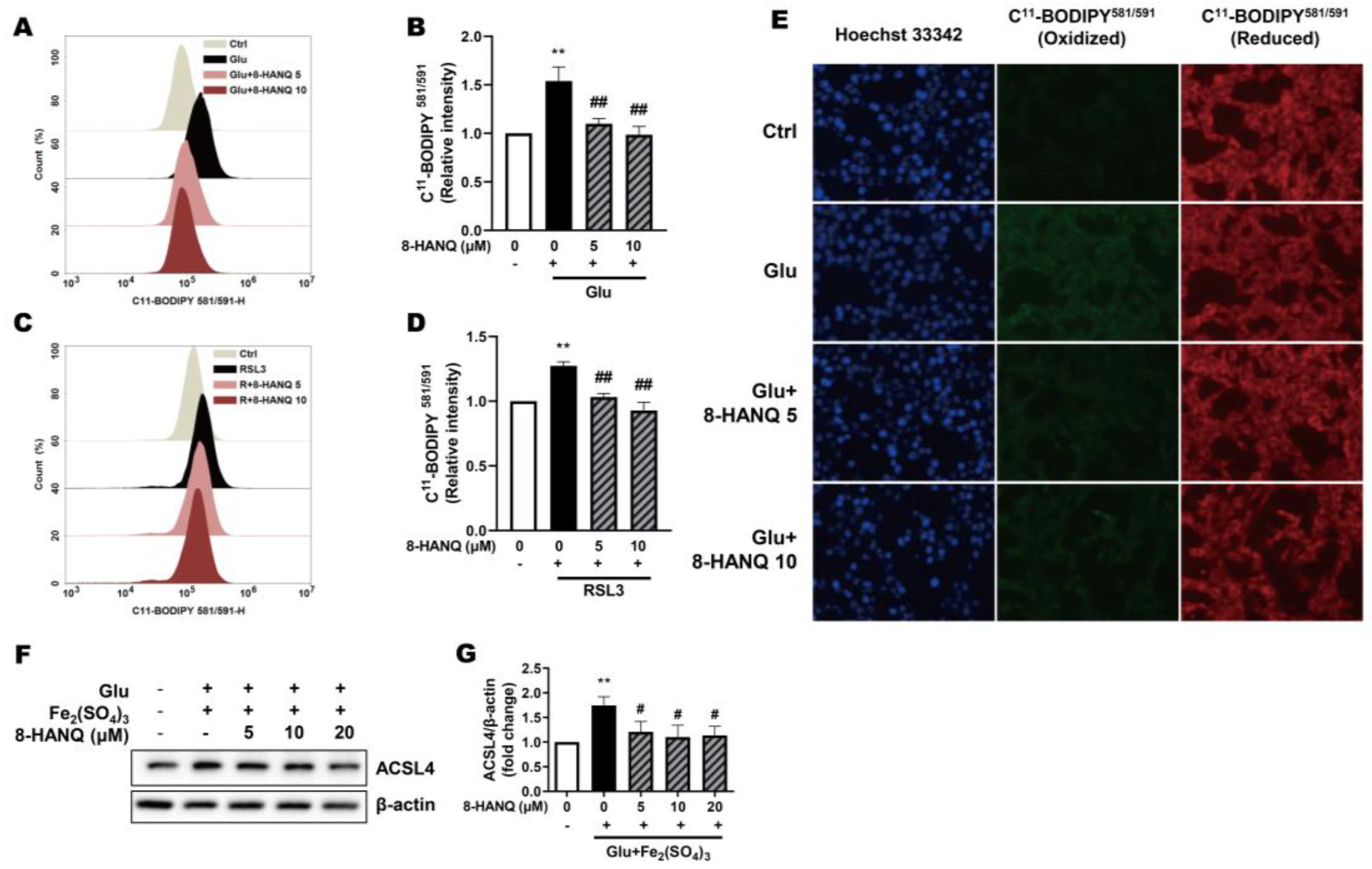

Suppression of increased ferroptosis-associated lipid ROS and ACSL4 levels by 8-HANQ. (A-D) Lipid ROS levels were measured using C11-BODIPY581/591 fluorescence with flow cytometry. 8-HANQ (5-10 μM) was applied 30 min prior to treatment with 30 mM glutamate (Glu; A-B, n=7) or 200 nM RSL3 (C-D, n=8) for 24 h. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. (E) Representative fluorescence images of C11-BODIPY581/591 staining obtained after 24 h of Glu (30 mM) exposure with or without 8-HANQ pretreatment (5-10 μM). Scale bar: 50 μm (n = 4). (F-G) Western blot analysis and quantification of ACSL4. HT22 cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (5-20 μM) 30 min, followed by exposure to 20 mM Glu and 25 μM iron (III) sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃) for 24 h (n=4). Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. (**p < 0.01 vs. Control (Ctrl, 0) ; ##p < 0.01 vs. Glu, RSL3, Glu+Fe₂(SO₄)₃). n indicates independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Suppression of increased ferroptosis-associated lipid ROS and ACSL4 levels by 8-HANQ. (A-D) Lipid ROS levels were measured using C11-BODIPY581/591 fluorescence with flow cytometry. 8-HANQ (5-10 μM) was applied 30 min prior to treatment with 30 mM glutamate (Glu; A-B, n=7) or 200 nM RSL3 (C-D, n=8) for 24 h. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. (E) Representative fluorescence images of C11-BODIPY581/591 staining obtained after 24 h of Glu (30 mM) exposure with or without 8-HANQ pretreatment (5-10 μM). Scale bar: 50 μm (n = 4). (F-G) Western blot analysis and quantification of ACSL4. HT22 cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (5-20 μM) 30 min, followed by exposure to 20 mM Glu and 25 μM iron (III) sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃) for 24 h (n=4). Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. (**p < 0.01 vs. Control (Ctrl, 0) ; ##p < 0.01 vs. Glu, RSL3, Glu+Fe₂(SO₄)₃). n indicates independent experiments.

Figure 4.

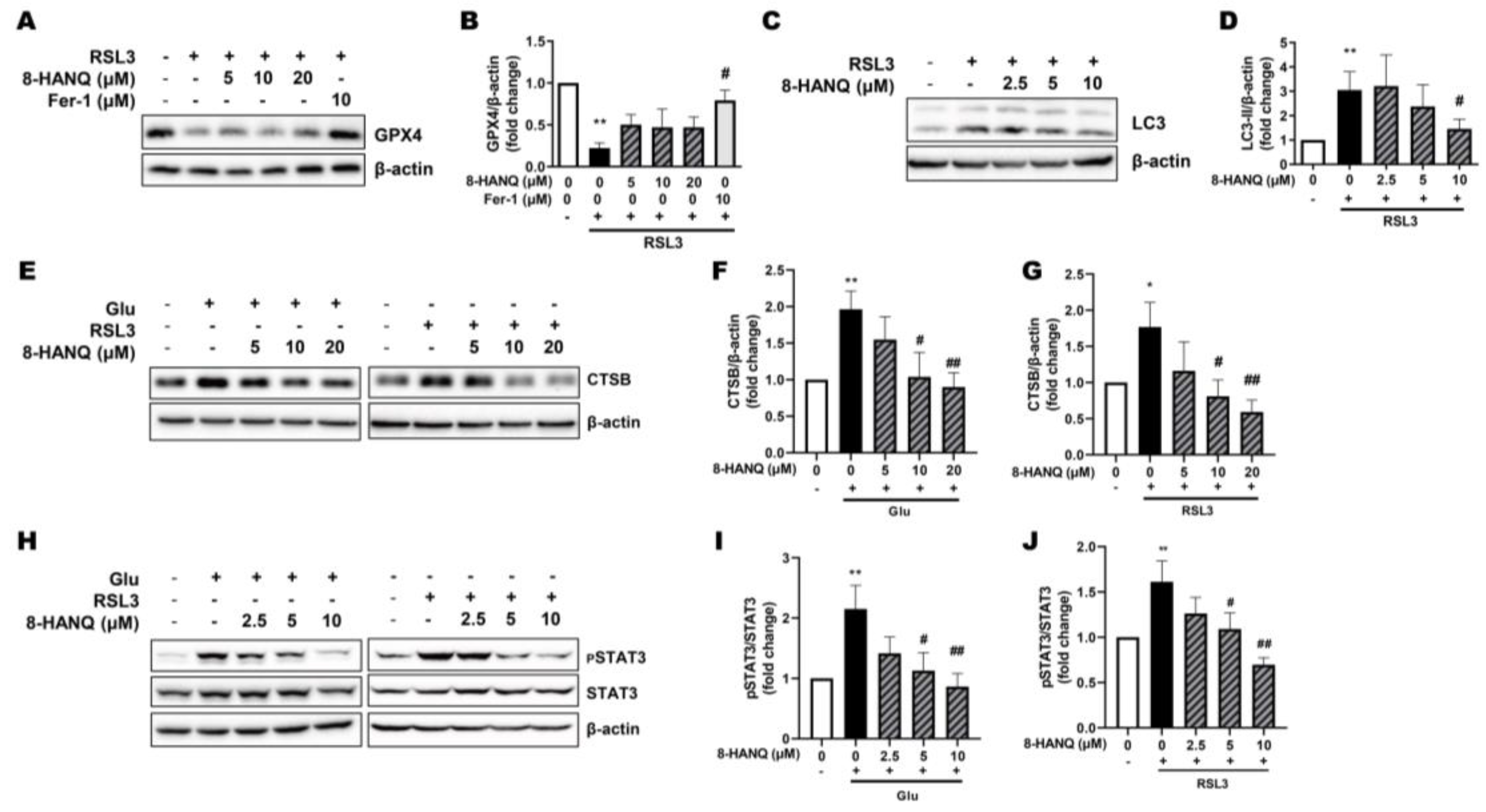

Modulation of STAT3-dependent cathepsin-B overexpression by 8-HANQ independently of GPX4 regulation. (A-D) Western blot analysis of GPX4 (A-B, n=3) and LC3-II (C-D, n=5) expression in RSL3-induced ferroptotic HT22 cells. Cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (2.5-20 μM) or 10 μM ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) for 30 min, followed by co-treatment with 200 nM RSL3 for 24 h. (E-J) Western blot images and quantification of cathepsin-B (CTSB) levels (E-G; F, n=4; G, n=5) and pSTAT3/STAT3 (H-J; I, n=5; J, n=6). Cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (2.5-20 μM) for 30 min, followed by co-incubation with either 30 mM glutamate (Glu) or 200 nM RSL3 for 24 h. Data represent means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA (A-B) or Student’s t-test (C-J). (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. Control (0) ; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Glu, RSL3). n indicates independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Modulation of STAT3-dependent cathepsin-B overexpression by 8-HANQ independently of GPX4 regulation. (A-D) Western blot analysis of GPX4 (A-B, n=3) and LC3-II (C-D, n=5) expression in RSL3-induced ferroptotic HT22 cells. Cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (2.5-20 μM) or 10 μM ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) for 30 min, followed by co-treatment with 200 nM RSL3 for 24 h. (E-J) Western blot images and quantification of cathepsin-B (CTSB) levels (E-G; F, n=4; G, n=5) and pSTAT3/STAT3 (H-J; I, n=5; J, n=6). Cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (2.5-20 μM) for 30 min, followed by co-incubation with either 30 mM glutamate (Glu) or 200 nM RSL3 for 24 h. Data represent means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA (A-B) or Student’s t-test (C-J). (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. Control (0) ; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Glu, RSL3). n indicates independent experiments.

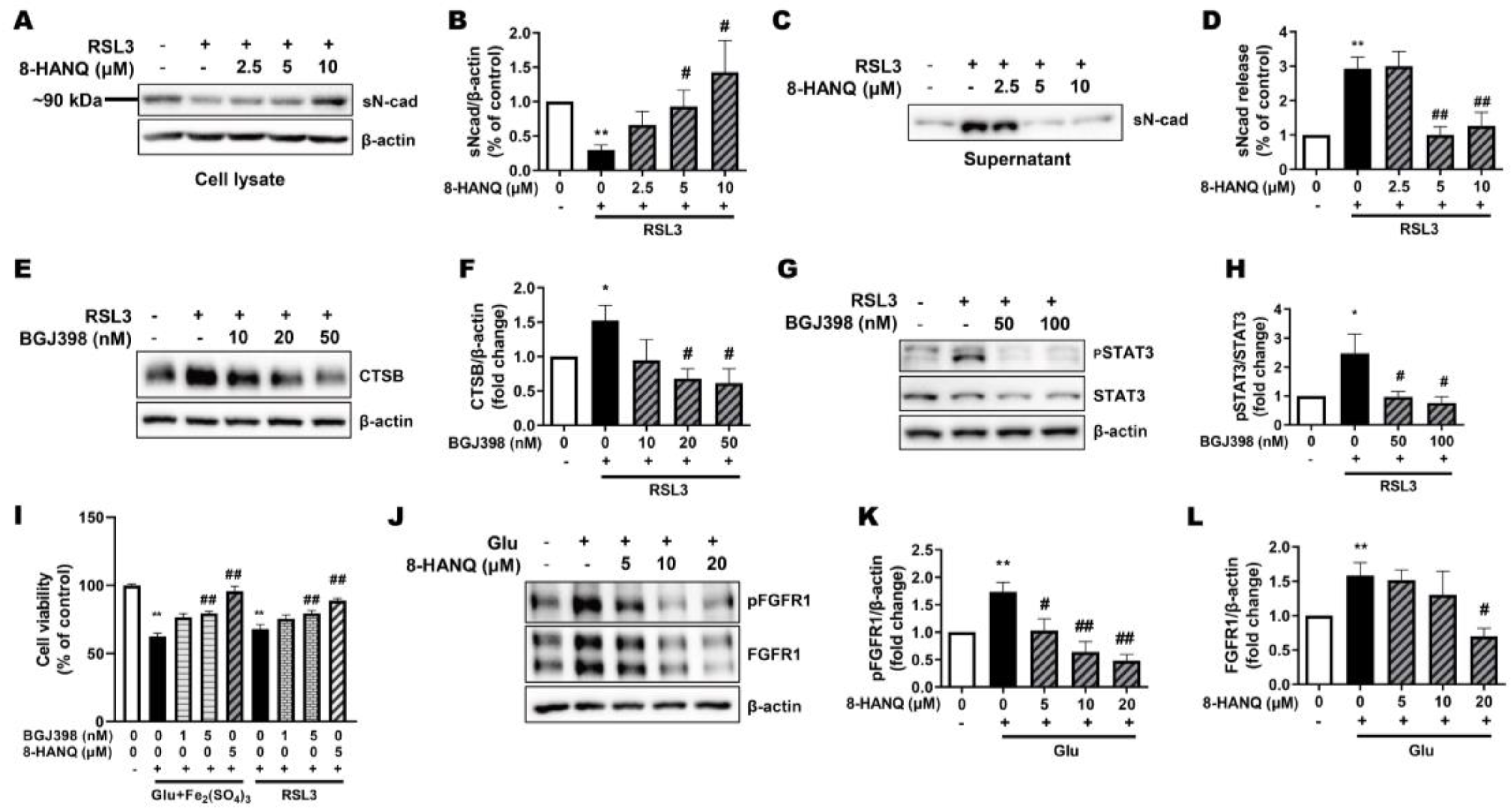

Figure 5.

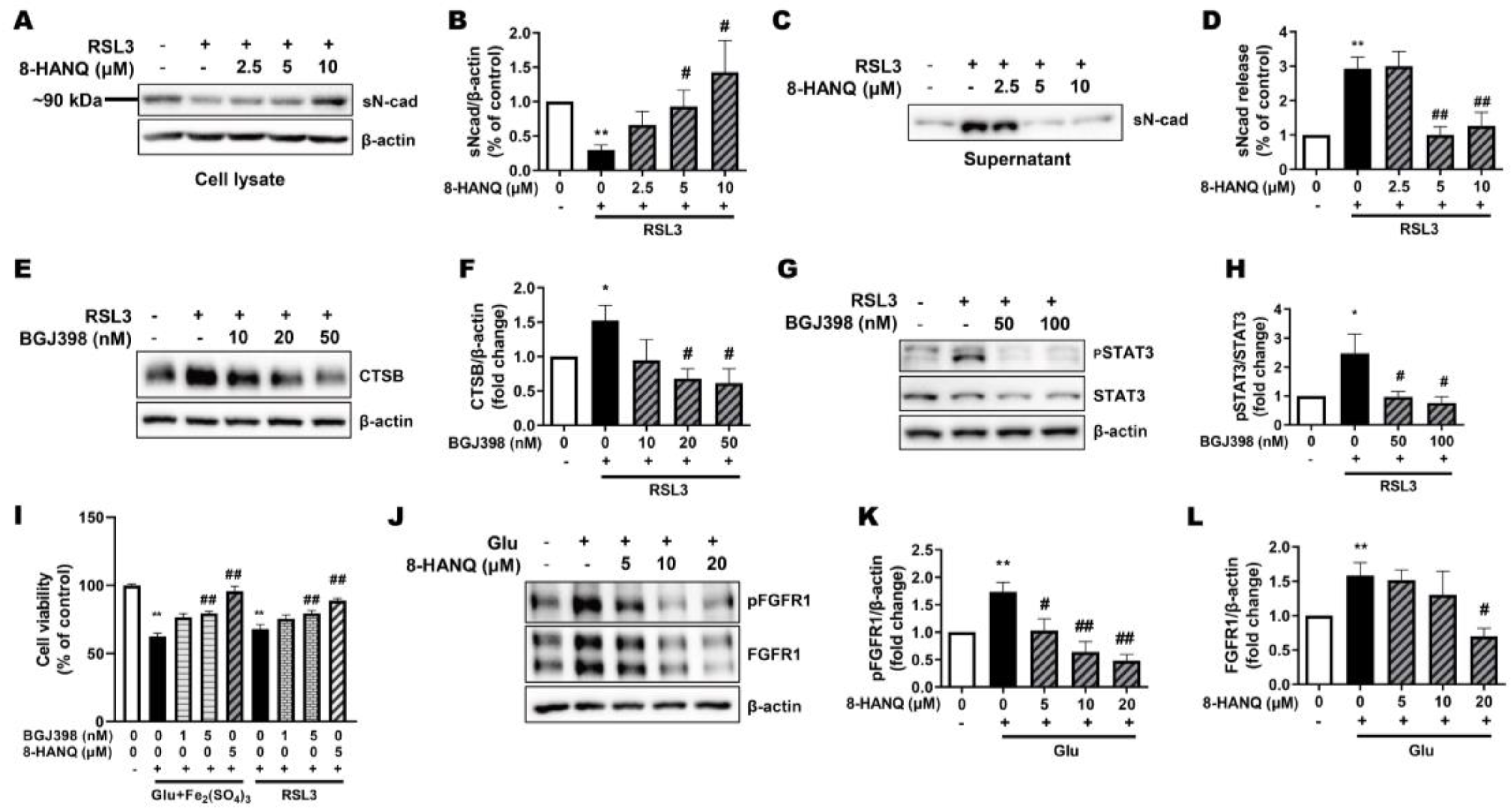

Suppressive effect of 8-HANQ on increased levels of FGFR1, pSTAT3/STAT3, cathepsin-B and soluble N-cadherin release during ferroptosis. (A-D) Western blot analysis and quantification of soluble N-cadherin in cell lysates (A-B, n=7) and culture supernatants (C-D, n=7). Cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (2.5-10 μM) for 30 min, followed by exposure to 200 nM RSL3 for 24 h. Supernatants were concentrated from cell culture media using desalting columns prior to analysis. (E-H) Western blot analysis and quantification of CTSB expression (E-F, n=3) and pSTAT3/STAT3 (G-H, n=4) following BGJ398 treatment during ferroptosis. Cells were pretreated with BGJ398 (10-100 nM) for 30 min before exposure to 200 nM RSL3 for 4 h (pSTAT3/STAT3) or 24 h (CTSB). (I) Measurement of cell protection of BGJ398 using the WST-8 assay. BGJ398 (1-5 nM) or 8-HANQ (5 μM) was added 30 min before exposure to 5 mM glutamate (Glu) and 100 μM iron (III) sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃) or 50 nM RSL3 (n=6). (J-L) Western blot analysis and quantification of pFGFR1 and total FGFR1 following 8-HANQ (5-20 μM) treatment for 2 h and 30 mM Glu exposure for 6 h (n=4). Data represent means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA (I) or Student’s t-test (A-H, J-L). (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. Control (0) ; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. RSL3, Glu+Fe₂(SO₄)₃, Glu). n indicates independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Suppressive effect of 8-HANQ on increased levels of FGFR1, pSTAT3/STAT3, cathepsin-B and soluble N-cadherin release during ferroptosis. (A-D) Western blot analysis and quantification of soluble N-cadherin in cell lysates (A-B, n=7) and culture supernatants (C-D, n=7). Cells were pretreated with 8-HANQ (2.5-10 μM) for 30 min, followed by exposure to 200 nM RSL3 for 24 h. Supernatants were concentrated from cell culture media using desalting columns prior to analysis. (E-H) Western blot analysis and quantification of CTSB expression (E-F, n=3) and pSTAT3/STAT3 (G-H, n=4) following BGJ398 treatment during ferroptosis. Cells were pretreated with BGJ398 (10-100 nM) for 30 min before exposure to 200 nM RSL3 for 4 h (pSTAT3/STAT3) or 24 h (CTSB). (I) Measurement of cell protection of BGJ398 using the WST-8 assay. BGJ398 (1-5 nM) or 8-HANQ (5 μM) was added 30 min before exposure to 5 mM glutamate (Glu) and 100 μM iron (III) sulfate (Fe₂(SO₄)₃) or 50 nM RSL3 (n=6). (J-L) Western blot analysis and quantification of pFGFR1 and total FGFR1 following 8-HANQ (5-20 μM) treatment for 2 h and 30 mM Glu exposure for 6 h (n=4). Data represent means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA (I) or Student’s t-test (A-H, J-L). (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. Control (0) ; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. RSL3, Glu+Fe₂(SO₄)₃, Glu). n indicates independent experiments.

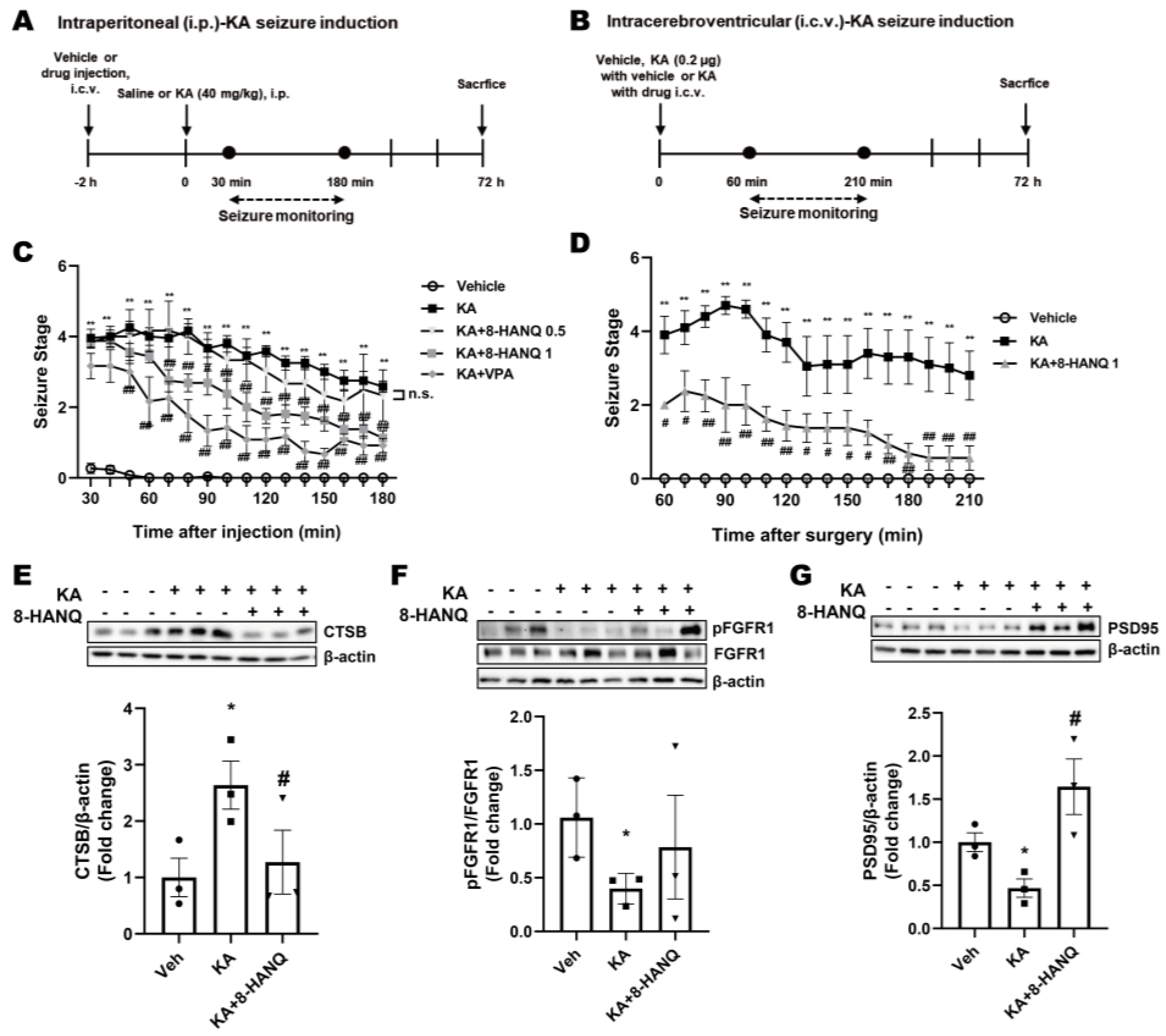

Figure 6.

Anti-seizure and neuroprotective effects of 8-HANQ in KA-induced mice. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental design for assessing the protective effect of 8-HANQ in intraperitoneal (i.p.) kainate (KA)-induced seizure model. (B) Schematic illustration of the experimental design for evaluating the protective effect of 8-HANQ in intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of KA-induced seizure model. (C) Mice received i.c.v. injections of vehicle (Veh; 80% DMSO in saline, 1 μl; n=13), 8-HANQ (0.5 μg, n=3; 1 μg, n=8), or valproate (VPA; 150 μg, n=6) 2 h prior to i.p. administration of KA (40 mg/kg; n=12). Seizure behavior was monitored every 10 min for 150 min (from 30 min to 180 min after KA injection). Valproate was used as a positive control. (D) Mice were administered Veh (40% DMSO in saline, 1 μl; n=3) or 8-HANQ (1 μg, n=4) together with 0.2 μg KA (n=4) via i.c.v. injection. Seizure scores were recorded every 10 min for 150 min (from 60 to 210 min after surgery). Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA. (E-G) Western blot analysis and quantification of cathepsin-B (CTSB; E), pFGFR1/FGFR1 ratio (F), and PSD95 (G) in hippocampal tissues collected 72 h after intracerebroventricular KA administration. Data are presented as means ± SEM from 3 mice per group. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. (*p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. Veh; #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 vs. KA).

Figure 6.

Anti-seizure and neuroprotective effects of 8-HANQ in KA-induced mice. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental design for assessing the protective effect of 8-HANQ in intraperitoneal (i.p.) kainate (KA)-induced seizure model. (B) Schematic illustration of the experimental design for evaluating the protective effect of 8-HANQ in intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of KA-induced seizure model. (C) Mice received i.c.v. injections of vehicle (Veh; 80% DMSO in saline, 1 μl; n=13), 8-HANQ (0.5 μg, n=3; 1 μg, n=8), or valproate (VPA; 150 μg, n=6) 2 h prior to i.p. administration of KA (40 mg/kg; n=12). Seizure behavior was monitored every 10 min for 150 min (from 30 min to 180 min after KA injection). Valproate was used as a positive control. (D) Mice were administered Veh (40% DMSO in saline, 1 μl; n=3) or 8-HANQ (1 μg, n=4) together with 0.2 μg KA (n=4) via i.c.v. injection. Seizure scores were recorded every 10 min for 150 min (from 60 to 210 min after surgery). Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA. (E-G) Western blot analysis and quantification of cathepsin-B (CTSB; E), pFGFR1/FGFR1 ratio (F), and PSD95 (G) in hippocampal tissues collected 72 h after intracerebroventricular KA administration. Data are presented as means ± SEM from 3 mice per group. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. (*p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. Veh; #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 vs. KA).