Submitted:

22 February 2024

Posted:

29 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Live Cell Imaging

2.3. PrestoBlue Cell Viability Assay

2.4. Measurement of GSH Levels

2.5. Immunoblotting

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Mitochondrial Depolarization in FUS -Mutated Cells

3.2. Increased Sensitivity to Ferroptosis in FUS Mutated Cells

3.3. Liproxstatin-1 Suppressed Ferroptosis in HeLa-FUS Cells

3.4. FUS Mutated Cells Exhibit Misregulation of Key Factors of Ferroptosis

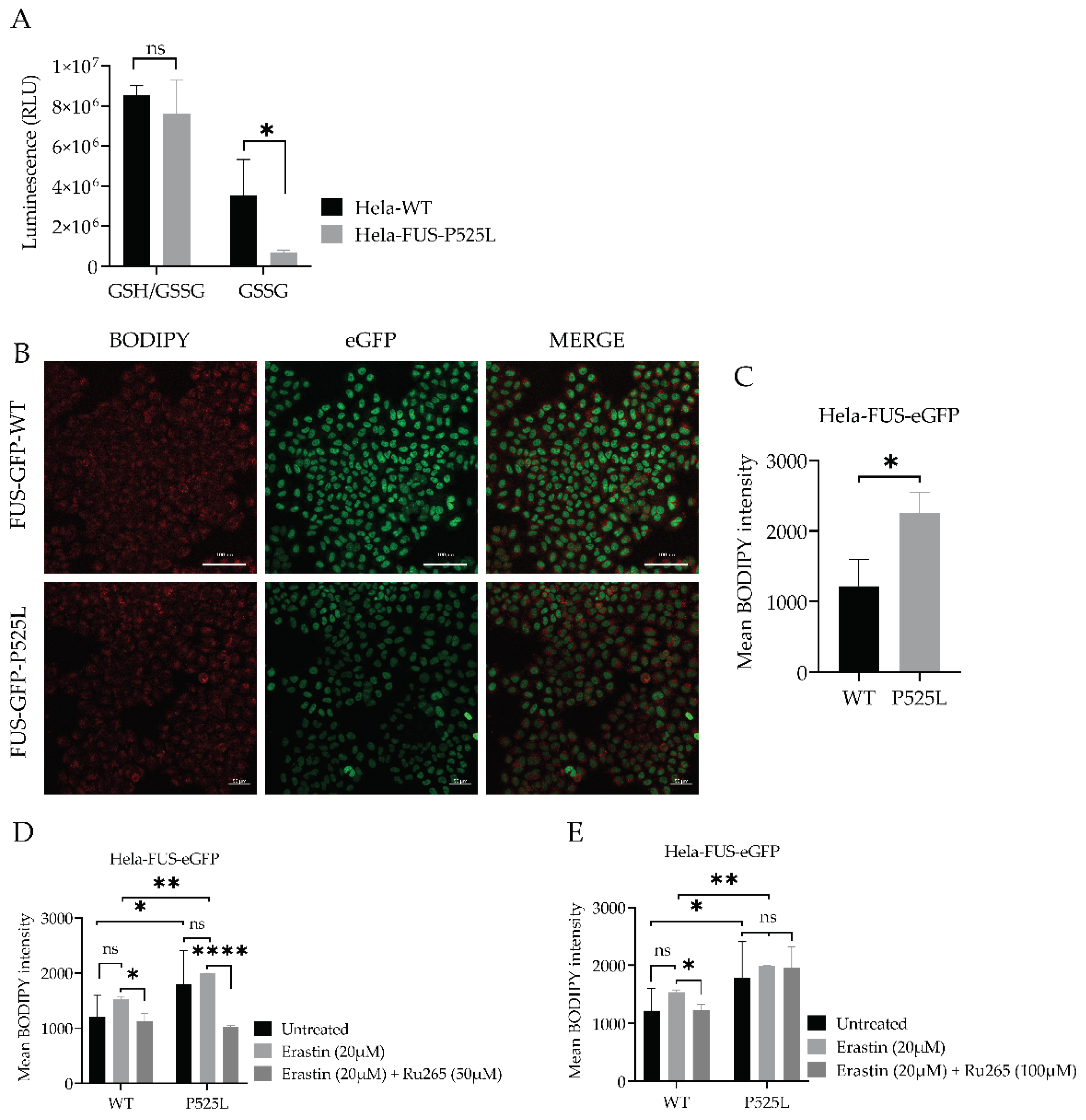

3.5. FUS Mutations Lead to Disturbance of Cellular Redox Defense System Downstream of xCT

3.6. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Alleviates Lipid Peroxidation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Angeli, J. P. F., R. Shah, D. A. Pratt and M. Conrad (2017). "Ferroptosis Inhibition: Mechanisms and Opportunities." Trends Pharmacol Sci 38(5): 489-498. [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A., M. F. Munoz and S. Arguelles (2014). "Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal." Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014: 360438. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. H. and A. Al-Chalabi (2017). "Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis." N Engl J Med 377(2): 162-172. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. Y. and S. J. Dixon (2016). "Mechanisms of ferroptosis." Cell Mol Life Sci 73(11-12): 2195-2209. [CrossRef]

- Carracedo, A., J. M. Prieto, L. Concheiro and J. Estefania (1987). "Isoelectric focusing patterns of some mammalian keratins." J Forensic Sci 32(1): 93-99. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., W. S. Hambright, R. Na and Q. Ran (2015). "Ablation of the Ferroptosis Inhibitor Glutathione Peroxidase 4 in Neurons Results in Rapid Motor Neuron Degeneration and Paralysis." J Biol Chem 290(47): 28097-28106. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. W., T. J. Wardill, Y. Sun, S. R. Pulver, S. L. Renninger, A. Baohan, E. R. Schreiter, R. A. Kerr, M. B. Orger, V. Jayaraman, L. L. Looger, K. Svoboda and D. S. Kim (2013). "Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity." Nature 499(7458): 295-300. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., C. Yu, R. Kang and D. Tang (2020). "Iron Metabolism in Ferroptosis." Front Cell Dev Biol 8: 590226. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M. and J. P. Friedmann Angeli (2015). "Glutathione peroxidase 4 (Gpx4) and ferroptosis: what’s so special about it?" Mol Cell Oncol 2(3): e995047. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S. J., K. M. Lemberg, M. R. Lamprecht, R. Skouta, E. M. Zaitsev, C. E. Gleason, D. N. Patel, A. J. Bauer, A. M. Cantley, W. S. Yang, B. Morrison, 3rd and B. R. Stockwell (2012). "Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death." Cell 149(5): 1060-1072. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S. J., D. N. Patel, M. Welsch, R. Skouta, E. D. Lee, M. Hayano, A. G. Thomas, C. E. Gleason, N. P. Tatonetti, B. S. Slusher and B. R. Stockwell (2014). "Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis." Elife 3: e02523. [CrossRef]

- Do Van, B., F. Gouel, A. Jonneaux, K. Timmerman, P. Gele, M. Petrault, M. Bastide, C. Laloux, C. Moreau, R. Bordet, D. Devos and J. C. Devedjian (2016). "Ferroptosis, a newly characterized form of cell death in Parkinson’s disease that is regulated by PKC." Neurobiol Dis 94: 169-178. [CrossRef]

- Doll, S., B. Proneth, Y. Y. Tyurina, E. Panzilius, S. Kobayashi, I. Ingold, M. Irmler, J. Beckers, M. Aichler, A. Walch, H. Prokisch, D. Trumbach, G. Mao, F. Qu, H. Bayir, J. Fullekrug, C. H. Scheel, W. Wurst, J. A. Schick, V. E. Kagan, J. P. Angeli and M. Conrad (2017). "ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition." Nat Chem Biol 13(1): 91-98. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K. C., E. J. O’Reilly, G. J. Falcone, M. L. McCullough, Y. Park, L. N. Kolonel and A. Ascherio (2014). "Dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and risk for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis." JAMA Neurol 71(9): 1102-1110. [CrossRef]

- Fleury, C., B. Mignotte and J. L. Vayssiere (2002). "Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in cell death signaling." Biochimie 84(2-3): 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Forcina, G. C. and S. J. Dixon (2019). "GPX4 at the Crossroads of Lipid Homeostasis and Ferroptosis." Proteomics 19(18): e1800311. [CrossRef]

- Friedmann Angeli, J. P., M. Schneider, B. Proneth, Y. Y. Tyurina, V. A. Tyurin, V. J. Hammond, N. Herbach, M. Aichler, A. Walch, E. Eggenhofer, D. Basavarajappa, O. Radmark, S. Kobayashi, T. Seibt, H. Beck, F. Neff, I. Esposito, R. Wanke, H. Forster, O. Yefremova, M. Heinrichmeyer, G. W. Bornkamm, E. K. Geissler, S. B. Thomas, B. R. Stockwell, V. B. O’Donnell, V. E. Kagan, J. A. Schick and M. Conrad (2014). "Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice." Nat Cell Biol 16(12): 1180-1191. [CrossRef]

- Gleitze, S., A. Paula-Lima, M. T. Nunez and C. Hidalgo (2021). "The calcium-iron connection in ferroptosis-mediated neuronal death." Free Radic Biol Med 175: 28-41. [CrossRef]

- Greco, V., P. Longone, A. Spalloni, L. Pieroni and A. Urbani (2019). "Crosstalk Between Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage: Focus on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis." Adv Exp Med Biol 1158: 71-82. [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, D., N. Malburg, H. Glass, V. Weeren, V. Sondermann, J. F. Pfeiffer, J. Petters, J. Lukas, P. Seibler, C. Klein, A. Grunewald and A. Hermann (2023). "Mitochondria-Endoplasmic Reticulum Contact Sites Dynamics and Calcium Homeostasis Are Differentially Disrupted in PINK1-PD or PRKN-PD Neurons." Mov Disord 38(10): 1822-1836. [CrossRef]

- Gunther, R., A. Pal, C. Williams, V. L. Zimyanin, M. Liehr, C. von Neubeck, M. Krause, M. G. Parab, S. Petri, N. Kalmbach, S. L. Marklund, J. Sterneckert, P. Munch Andersen, F. Wegner, J. D. Gilthorpe and A. Hermann (2022). "Alteration of Mitochondrial Integrity as Upstream Event in the Pathophysiology of SOD1-ALS." Cells 11(7). [CrossRef]

- He, L., T. He, S. Farrar, L. Ji, T. Liu and X. Ma (2017). "Antioxidants Maintain Cellular Redox Homeostasis by Elimination of Reactive Oxygen Species." Cell Physiol Biochem 44(2): 532-553. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., S. N. MacMillan and J. J. Wilson (2023). "A Fluorogenic Inhibitor of the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter." Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 62(6): e202214920. [CrossRef]

- Kreiter, N., A. Pal, X. Lojewski, P. Corcia, M. Naujock, P. Reinhardt, J. Sterneckert, S. Petri, F. Wegner, A. Storch and A. Hermann (2018). "Age-dependent neurodegeneration and organelle transport deficiencies in mutant TDP43 patient-derived neurons are independent of TDP43 aggregation." Neurobiol Dis 115: 167-181. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D. H., H. J. Cha, H. Lee, S. H. Hong, C. Park, S. H. Park, G. Y. Kim, S. Kim, H. S. Kim, H. J. Hwang and Y. H. Choi (2019). "Protective Effect of Glutathione against Oxidative Stress-induced Cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 Macrophages through Activating the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor-2/Heme Oxygenase-1 Pathway." Antioxidants (Basel) 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Lewerenz, J., G. Ates, A. Methner, M. Conrad and P. Maher (2018). "Oxytosis/Ferroptosis-(Re-) Emerging Roles for Oxidative Stress-Dependent Non-apoptotic Cell Death in Diseases of the Central Nervous System." Front Neurosci 12: 214. [CrossRef]

- Lewerenz, J., S. J. Hewett, Y. Huang, M. Lambros, P. W. Gout, P. W. Kalivas, A. Massie, I. Smolders, A. Methner, M. Pergande, S. B. Smith, V. Ganapathy and P. Maher (2013). "The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(-) in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities." Antioxid Redox Signal 18(5): 522-555. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., F. Cao, H. L. Yin, Z. J. Huang, Z. T. Lin, N. Mao, B. Sun and G. Wang (2020). "Ferroptosis: past, present and future." Cell Death Dis 11(2): 88. [CrossRef]

- Maher, P., K. van Leyen, P. N. Dey, B. Honrath, A. Dolga and A. Methner (2018). "The role of Ca(2+) in cell death caused by oxidative glutamate toxicity and ferroptosis." Cell Calcium 70: 47-55. [CrossRef]

- Marmolejo-Garza, A., I. E. Krabbendam, M. D. A. Luu, F. Brouwer, M. Trombetta-Lima, O. Unal, S. J. O’Connor, N. Majernikova, C. R. S. Elzinga, C. Mammucari, M. Schmidt, M. Madesh, E. Boddeke and A. M. Dolga (2023). "Negative modulation of mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex protects neurons against ferroptosis." Cell Death Dis 14(11): 772. [CrossRef]

- Munoz, P., A. Humeres, C. Elgueta, A. Kirkwood, C. Hidalgo and M. T. Nunez (2011). "Iron mediates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent stimulation of calcium-induced pathways and hippocampal synaptic plasticity." J Biol Chem 286(15): 13382-13392. [CrossRef]

- Naguib, Y. M. (2000). "Antioxidant activities of astaxanthin and related carotenoids." J Agric Food Chem 48(4): 1150-1154. [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M., A. Pal, A. Goswami, X. Lojewski, J. Japtok, A. Vehlow, M. Naujock, R. Gunther, M. Jin, N. Stanslowsky, P. Reinhardt, J. Sterneckert, M. Frickenhaus, F. Pan-Montojo, E. Storkebaum, I. Poser, A. Freischmidt, J. H. Weishaupt, K. Holzmann, D. Troost, A. C. Ludolph, T. M. Boeckers, S. Liebau, S. Petri, N. Cordes, A. A. Hyman, F. Wegner, S. W. Grill, J. Weis, A. Storch and A. Hermann (2018). "Impaired DNA damage response signaling by FUS-NLS mutations leads to neurodegeneration and FUS aggregate formation." Nat Commun 9(1): 335. [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M., K. Peikert, R. Gunther, A. J. van der Kooi, E. Aronica, A. Hubers, V. Danel, P. Corcia, F. Pan-Montojo, S. Cirak, G. Haliloglu, A. C. Ludolph, A. Goswami, P. M. Andersen, J. Prudlo, F. Wegner, P. Van Damme, J. H. Weishaupt and A. Hermann (2019). "Phenotypes and malignancy risk of different FUS mutations in genetic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis." Ann Clin Transl Neurol 6(12): 2384-2394. [CrossRef]

- Nita, M. and A. Grzybowski (2016). "The Role of the Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in the Pathomechanism of the Age-Related Ocular Diseases and Other Pathologies of the Anterior and Posterior Eye Segments in Adults." Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016: 3164734. [CrossRef]

- Pal, A., H. Glaß, M. Naumann, N. Kreiter, J. Japtok, R. Sczech and A. Hermann (2018). "High content organelle trafficking enables disease state profiling as powerful tool for disease modelling." Sci Data 5: 180241. [CrossRef]

- Pal, A., B. Kretner, M. Abo-Rady, H. Glabeta, B. P. Dash, M. Naumann, J. Japtok, N. Kreiter, A. Dhingra, P. Heutink, T. M. Bockers, R. Gunther, J. Sterneckert and A. Hermann (2021). "Concomitant gain and loss of function pathomechanisms in C9ORF72 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis." Life Sci Alliance 4(4). [CrossRef]

- Patel, A., H. O. Lee, L. Jawerth, S. Maharana, M. Jahnel, M. Y. Hein, S. Stoynov, J. Mahamid, S. Saha, T. M. Franzmann, A. Pozniakovski, I. Poser, N. Maghelli, L. A. Royer, M. Weigert, E. W. Myers, S. Grill, D. Drechsel, A. A. Hyman and S. Alberti (2015). "A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation." Cell 162(5): 1066-1077. [CrossRef]

- Pedrera, L., R. A. Espiritu, U. Ros, J. Weber, A. Schmitt, J. Stroh, S. Hailfinger, S. von Karstedt and A. J. Garcia-Saez (2021). "Ferroptotic pores induce Ca(2+) fluxes and ESCRT-III activation to modulate cell death kinetics." Cell Death Differ 28(5): 1644-1657. [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G., N. Irrera, M. Cucinotta, G. Pallio, F. Mannino, V. Arcoraci, F. Squadrito, D. Altavilla and A. Bitto (2017). "Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health." Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017: 8416763. [CrossRef]

- Sanmartin, C. D., A. C. Paula-Lima, A. Garcia, P. Barattini, S. Hartel, M. T. Nunez and C. Hidalgo (2014). "Ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca(2+) release underlies iron-induced mitochondrial fission and stimulates mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake in primary hippocampal neurons." Front Mol Neurosci 7: 13. [CrossRef]

- Sato, M., R. Kusumi, S. Hamashima, S. Kobayashi, S. Sasaki, Y. Komiyama, T. Izumikawa, M. Conrad, S. Bannai and H. Sato (2018). "The ferroptosis inducer erastin irreversibly inhibits system x(c)- and synergizes with cisplatin to increase cisplatin’s cytotoxicity in cancer cells." Sci Rep 8(1): 968. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z., L. Zhang, J. Zheng, H. Sun and C. Shao (2021). "Ferroptosis: Biochemistry and Biology in Cancers." Front Oncol 11: 579286. [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B. R., J. P. Friedmann Angeli, H. Bayir, A. I. Bush, M. Conrad, S. J. Dixon, S. Fulda, S. Gascon, S. K. Hatzios, V. E. Kagan, K. Noel, X. Jiang, A. Linkermann, M. E. Murphy, M. Overholtzer, A. Oyagi, G. C. Pagnussat, J. Park, Q. Ran, C. S. Rosenfeld, K. Salnikow, D. Tang, F. M. Torti, S. V. Torti, S. Toyokuni, K. A. Woerpel and D. D. Zhang (2017). "Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease." Cell 171(2): 273-285. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D. and G. Kroemer (2020). "Ferroptosis." Curr Biol 30(21): R1292-R1297. [CrossRef]

- Turner, M. R., O. Hardiman, M. Benatar, B. R. Brooks, A. Chio, M. de Carvalho, P. G. Ince, C. Lin, R. G. Miller, H. Mitsumoto, G. Nicholson, J. Ravits, P. J. Shaw, M. Swash, K. Talbot, B. J. Traynor, L. H. Van den Berg, J. H. Veldink, S. Vucic and M. C. Kiernan (2013). "Controversies and priorities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis." Lancet Neurol 12(3): 310-322. [CrossRef]

- Valko, K. and L. Ciesla (2019). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis." Prog Med Chem 58: 63-117. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., W. Liang, D. Huo, H. Wang, Y. Wang, C. Cong, C. Zhang, S. Yan, M. Gao, X. Su, X. Tan, W. Zhang, L. Han, D. Zhang and H. Feng (2023). "SPY1 inhibits neuronal ferroptosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by reducing lipid peroxidation through regulation of GCH1 and TFR1." Cell Death Differ 30(2): 369-382. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., D. Tomas, N. D. Perera, B. Cuic, S. Luikinga, A. Viden, S. K. Barton, C. A. McLean, A. L. Samson, A. Southon, A. I. Bush, J. M. Murphy and B. J. Turner (2022). "Ferroptosis mediates selective motor neuron death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis." Cell Death Differ 29(6): 1187-1198. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. S., R. SriRamaratnam, M. E. Welsch, K. Shimada, R. Skouta, V. S. Viswanathan, J. H. Cheah, P. A. Clemons, A. F. Shamji, C. B. Clish, L. M. Brown, A. W. Girotti, V. W. Cornish, S. L. Schreiber and B. R. Stockwell (2014). "Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4." Cell 156(1-2): 317-331. [CrossRef]

- Zimyanin, V. L., A. M. Pielka, H. Glass, J. Japtok, D. Grossmann, M. Martin, A. Deussen, B. Szewczyk, C. Deppmann, E. Zunder, P. M. Andersen, T. M. Boeckers, J. Sterneckert, S. Redemann, A. Storch and A. Hermann (2023). "Live Cell Imaging of ATP Levels Reveals Metabolic Compartmentalization within Motoneurons and Early Metabolic Changes in FUS ALS Motoneurons." Cells 12(10). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).