Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Moina macrocopa and Chlorella vulgaris Maintenance

2.2. Preparation of ABS Microplastics

2.3. Ingestion of Moina macrocopa to ABS-MPs

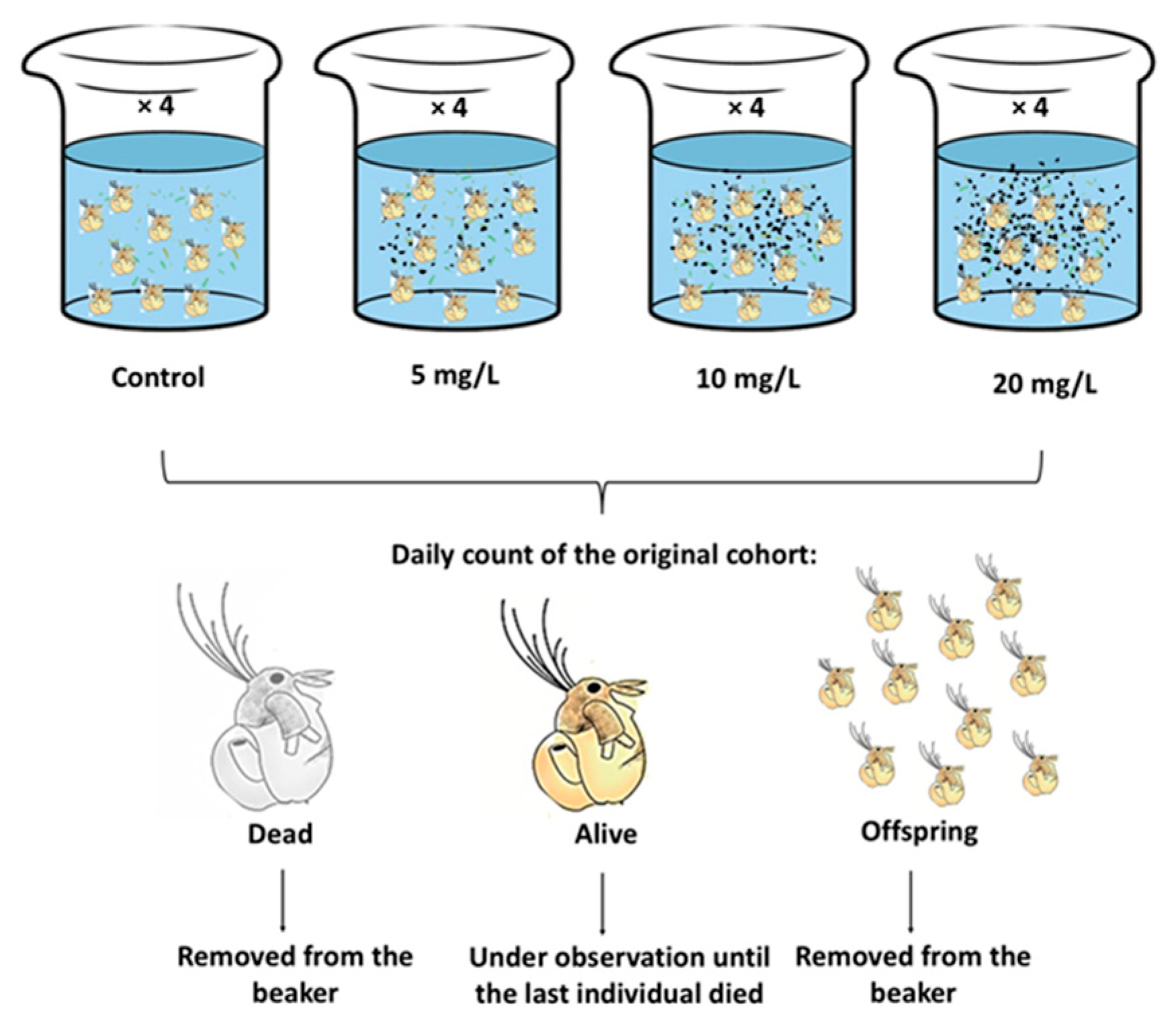

2.4. Exposure of Moina macrocopa to ABS-MPs

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

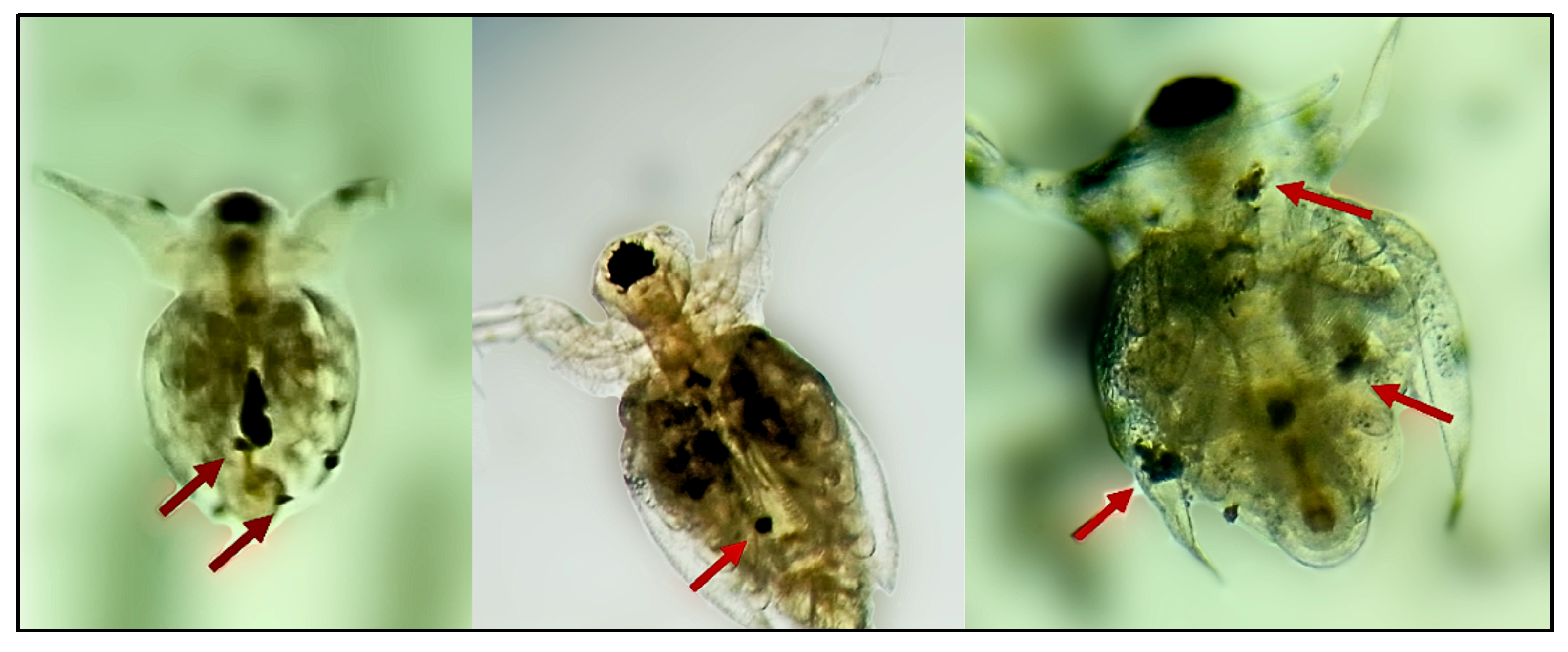

3.1. Cells Ingestion of Moina macrocopa

3.2. Survivorship

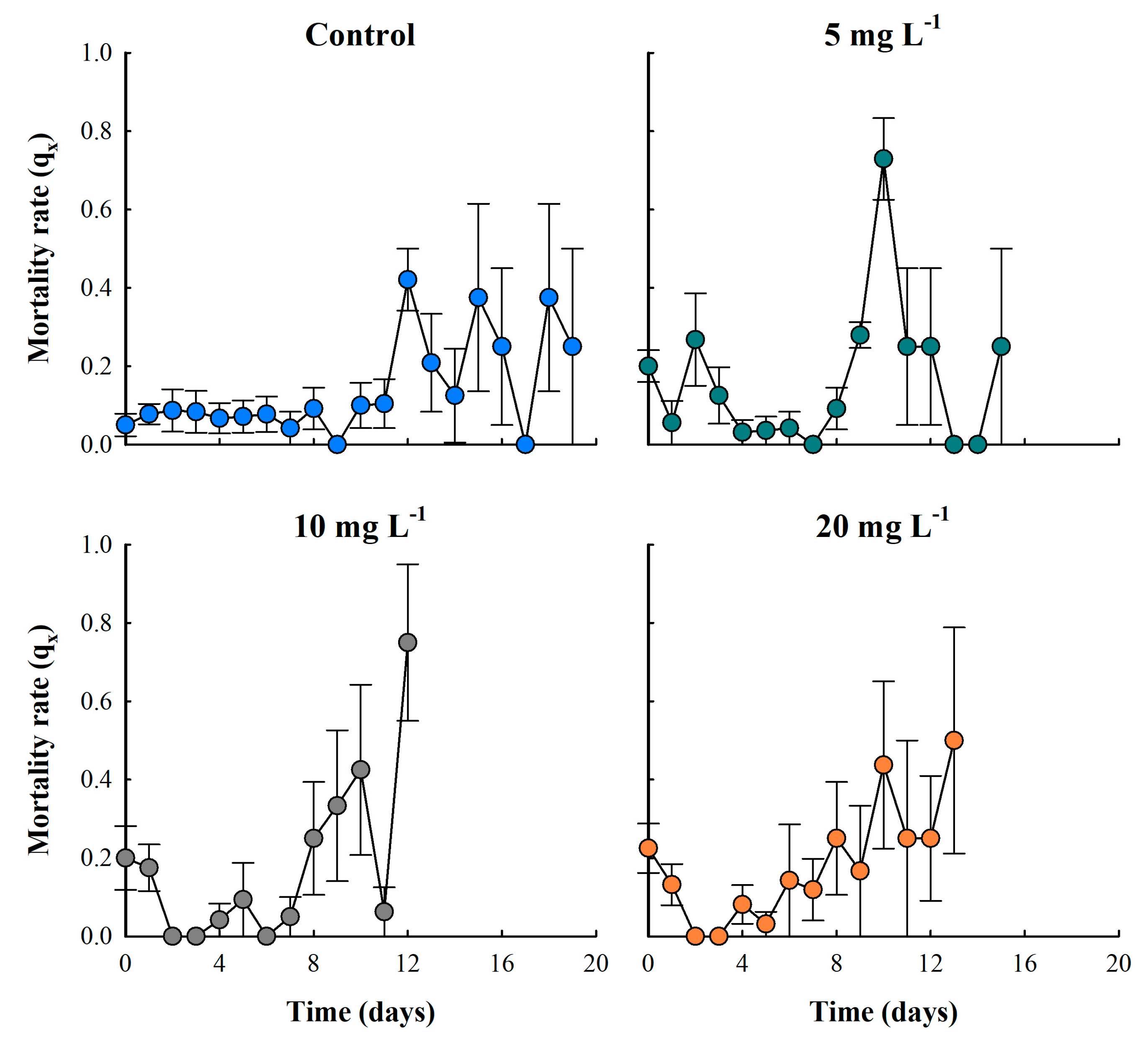

3.3. Mortality Rate

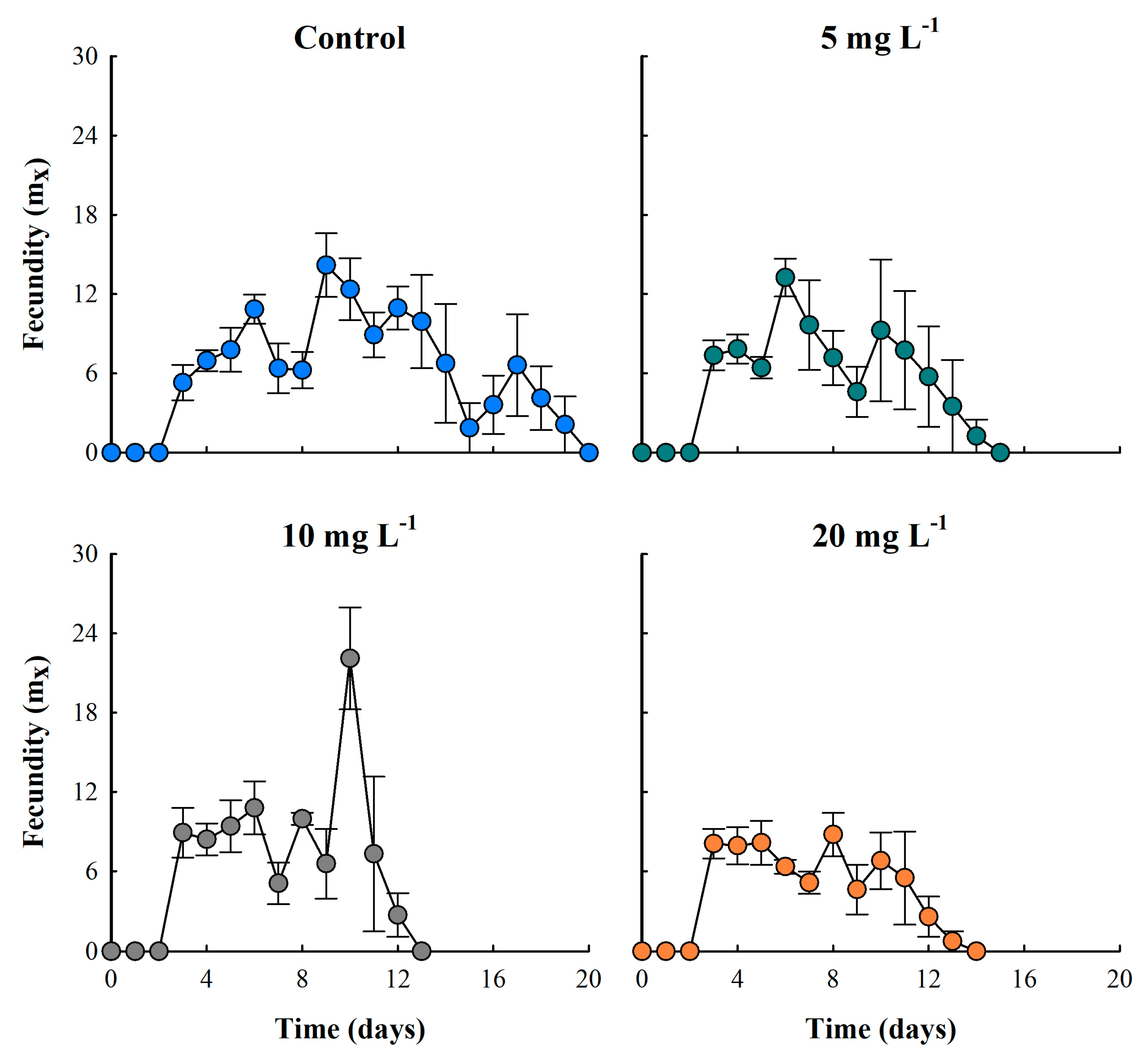

3.4. Fecundity

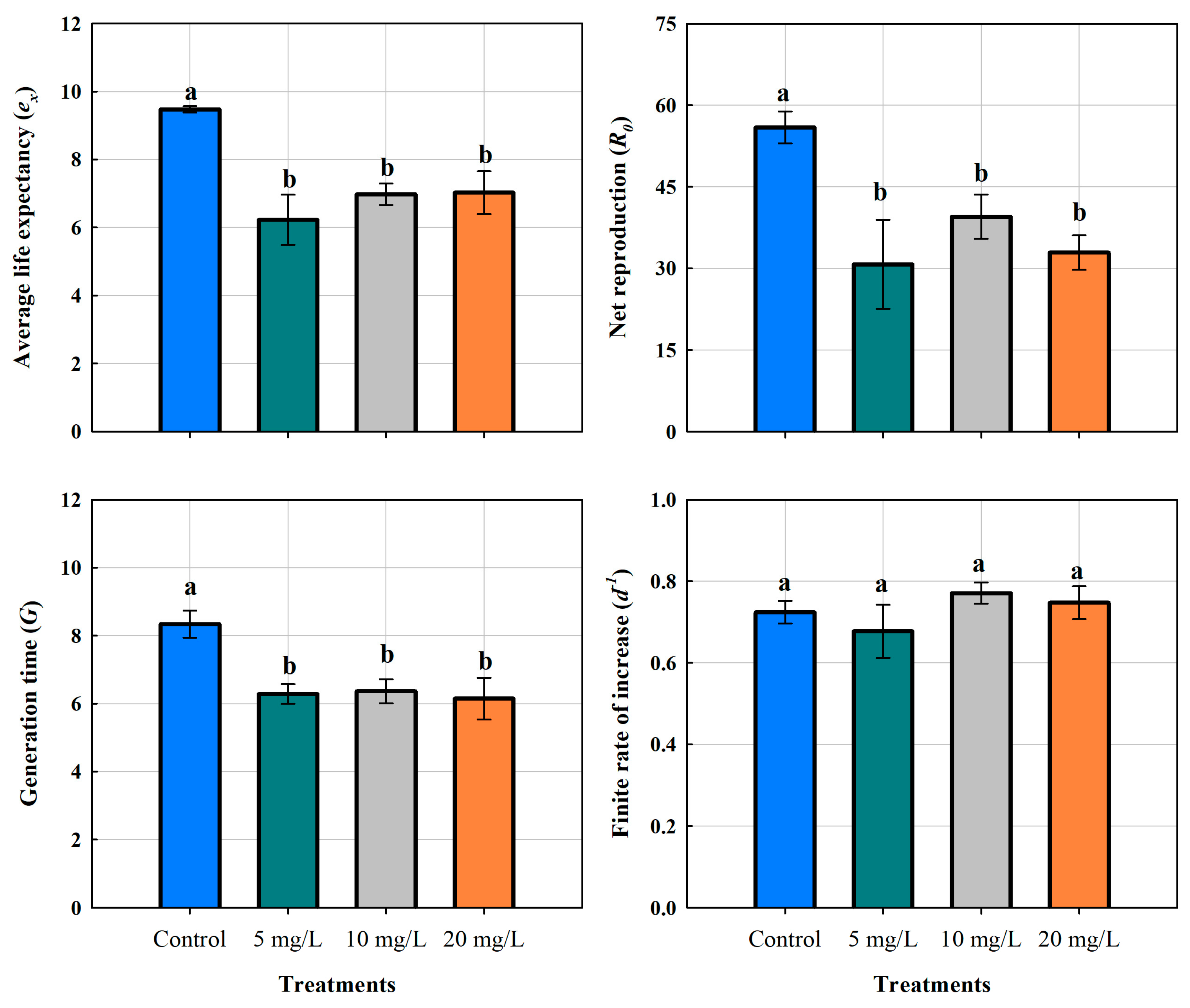

3.5. Life Table Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPs | Microplastics |

| ABS-MPs | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene microplastics |

| PS | polystyrene |

| PE | polyethylene |

| PVC | polyvinyl chloride |

| PET | polyethylene terephthalate |

References

- Barnes, D.K.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 1985, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuoka, T.; Sakane, F.; Kinoshita, C.; Sato, K.; Mizukawa, K.; Takada, H. Covid-19-derived plastic debris contaminating marine ecosystem: alert from a sea turtle. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 175, 113389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, J.P.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2019, 138, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; Hamid, A.K.; Krebsbach, S.A.; He, J.; Wang, D. Critical review of microplastics removal from the environment. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.; Berenstein, G.; Hughes, E.A.; Zalts, A.; Montserrat, J.M. Polyethylene film incorporation into the horticultural soil of small periurban production units in Argentina. Science of the Total Environment 2015, 523, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, N.M.; Berry, K.L.E.; Rintoul, L.; Hoogenboom, M.O. Microplastic ingestion by scleractinian corals. Marine Biology 2015, 162, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, E.M.; Ehlers, S.M.; Dick, J.T.; Sigwart, J.D.; Linse, K.; Dick, J.J.; Kiriakoulakis, K. High abundances of microplastic pollution in deep-sea sediments: evidence from Antarctica and the Southern Ocean. Environmental Science & Technology 2020, 54, 13661–13671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, A.R.; Hoellein, T.J.; London, M.G.; Hittie, J.; Scott, J.W.; Kelly, J.J. Microplastic in surface waters of urban rivers: concentration, sources, and associated bacterial assemblages. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Avignon, G.; Gregory-Eaves, I.; Ricciardi, A. Microplastics in lakes and rivers: an issue of emerging significance to limnology. Environmental Reviews 2022, 30, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, V. , Chandra, S., Aherne, J., Alfonso, M. B., Antão-Geraldes, A. M., Attermeyer, K., & Leoni, B. (2023). Plastic debris in lakes and reservoirs. Nature 2023, 619, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Tassin, B. Sources and fate of microplastics in urban areas: a focus on Paris Megacity. In Freshwater microplastics: emerging environmental contaminants?. M. Wagner; S. Lambert Eds.; Springer, Heidelberg, 2017; pp. 69-84. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.; Wagner, M. Microplastics are contaminants of emerging concern in freshwater environments: an overview. In Freshwater microplastics: emerging environmental contaminants? M. Wagner & S. Lambert Eds.; Springer, Heidelberg, 2018; pp. 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.R.; Woodward, J.C.; Rothwell, J.J. Ingestion of microplastics by freshwater tubifex worms. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51, 12844–12851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T.S.; Cole, M.; Lewis, C. Interactions of microplastic debris throughout the marine ecosystem. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2017, 1, 0116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yu, C.; Chu, Q.; Wang, F.; Lan, T.; Wang, J. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of five pesticides on microplastics from agricultural polyethylene films. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Ma, X.; Song, Y.; Zuo, S.; Li, H.; Deng, W. A critical review on the interactions of microplastics with heavy metals: mechanism and their combined effect on organisms and humans. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 788, 147620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.T. Zooplankton fecal pellets, marine snow, phytodetritus, and the ocean’s biological pump. Progress in Oceanography, 2015, 130, 205–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.M.; Elliott, M.; Almeida, C.M.R.; Ramos, S. Microplastics and plankton: Knowledge from laboratory and field studies to distinguish contamination from pollution. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 417, 126057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cera, A.; Scalici, M. Freshwater wild biota exposure to microplastics: A global perspective. Ecology and Evolution 2021, 11, 9904–9916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, R.; Wei, Y. ,Xue, R. Uptake of polystyrene microplastics by marine rotifers under different experimental conditions. Environmental Earth Sciences 2021, 687, 012071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H. , Chu, T.W., Kuo, C.H., Hong, M.C., Chen, Y.Y., & Chen, B. Effects of microplastics on reproduction and growth of freshwater live feeds Daphnia magna. Fishes 2022, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Barrios, C. A.; Nandini, S.; Sarma, S. S. S. Effect of microplastics on the demography of Brachionus calyciflorus Pallas (Rotifera) over successive generations. Aquatic Toxicology 2024, 275, 107061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frydkjær, C. K.; Iversen, N.; Roslev, P. Ingestion and egestion of microplastics by the cladoceran Daphnia magna: Effects of regular and irregular shaped plastic and sorbed phenanthrene. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2017, 99, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemec, A.; Horvat, P.; Kunej, U.; Bele, M.; Kržan, A. Uptake and effects of microplastic textile fibers on freshwater crustacean Daphnia magna. Environmental Pollution 2016, 219, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sighicelli, M.; Pietrelli, L.; Lecce, F.; Iannilli, V.; Falconieri, M.; Coscia, L.; Di Vito, S.; Nuglio, S.; Zampetti, G. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of Italian Subalpine Lakes. Environmental Pollution 2018, 236, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithner, D.; Larsson, Å.; Dave, G. Environmental and health hazard ranking and assessment of plastic polymers based on chemical composition. Science of the Total Environment 2011, 409, 3309–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Nag, R. ; Cummins, E Ranking of potential hazards from microplastic polymers in the marine environment. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 429, 128399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignatti, A. M.; Cabrera, G. C.; Echaniz, S. A. Distribution and biological aspects of the introduced species Moina macrocopa (Straus, 1820) (Crustacea, Cladocera) in the semi-arid central region of Argentina. Biota Neotropica 2013, 13, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C. I. Methods for measuring the acute toxicity of effluents and receiving waters to freshwater and marine organisms (4th ed.). United States Environmental Protection Agency, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1993, EPA/600/4-90/027F, xv.

- KREBS.

- Uurasjärvi, E.; Hartikainen, S.; Setälä, O. , Lehtiniemi, M.; Koistinen, A. Microplastic concentrations, size distribution, and polymer types in the surface waters of a northern European lake. Water Environment Research 2020, 92, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokalj, A. J.; Kunej, U.; Skalar, T. Screening study of four environmentally relevant microplastic pollutants: Uptake and effects on Daphnia magna and Artemia franciscana. Chemosphere 2018, 208, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. , Hwang, J. S. Ontogenetic shifts in the ability of the cladoceran, Moina macrocopa Straus and Ceriodaphnia cornuta Sars to utilize ciliated protists as food source. International Review of Hydrobiology, 2008, 93, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M0.; Lindeque, P. K.; Fileman, E.; Halsband, C.; Goodhead, R.; Moger, J., Galloway, T. S. Microplastic ingestion by zooplankton. Environmental Science & Technology 2013, 47, 6646–6655. [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P. K.; Fileman, E.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T. S. The impact of polystyrene microplastics on feeding, function, and fecundity in the marine copepod Calanus helgolandicus. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Santillán, M. C., Nandini, S., Sarma, S. S. S. The combined effect of temperature and microplastics on Daphnia pulex Leydig, 1860 (Cladocera). Inland Waters, 2025 (just-accepted), 1.

- De Felice, B.; Sabatini, V.; Antenucci, S.; Gattoni, G.; Santo, N.; Bacchetta, R.; Ortenzi, M. A. , Parolini, M. Polystyrene microplastics ingestion induced behavioral effects to the cladoceran Daphnia magna. Chemosphere 2019, 231, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehse, S.; Kloas, W.; Zarfl, C. Short-term exposure with high concentrations of pristine microplastic particles leads to immobilization of Daphnia magna. Chemosphere 2016, 153, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D. G. D.; Destro, A. L. F.; Coimbra, E. C. L.; Silva, A. L. L. D.; Mounteer, A. H. Effects of PET microplastics on the freshwater crustacean Daphnia similis Claus, 1976. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensis 2023, 35, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, M.; Schür, C.; Jarsén, Å.; Gorokhova, E. The effects of natural and anthropogenic microparticles on individual fitness in Daphnia magna. PLOS ONE, 2016, 11, e0155063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, X.; Yin, J.; Han, Y.; Yang, J.; Lu, X.; Xie, T.; Akbar, S.; Lyu, K.; Yang, Z. Molecular characterization of thioredoxin reductase in waterflea Daphnia magna and its expression regulation by polystyrene microplastics. Aquatic Toxicology 2019, 208, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziajahromi, S.; Kumar, A.; Neale, P. A. , Leusch, F. D. Impact of microplastic beads and fibers on waterflea (Ceriodaphnia dubia) survival, growth, and reproduction: Implications of single and mixture exposures. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51, 13397–13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enserink, L.; de la Haye, M.; Maas, H. Reproductive strategy of Daphnia magna: Implications for chronic toxicity tests. Aquatic Toxicology 1993, 25, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of Variation | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 3 | 179587.383 | 59862.461 | 22.398 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 12 | 32071.468 | 2672.622 | ||

| Total | 15 | 211658.851 |

| Source of Variation | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average life span | |||||

| Between Groups | 3 | 25.007 | 8.336 | 10.474 | 0.001 |

| Residual | 12 | 9.550 | 0.796 | ||

| Total | 15 | 34.557 | |||

| Net reproductive rate | |||||

| Between Groups | 3 | 2114.262 | 704.754 | 10.429 | 0.001 |

| Residual | 12 | 810.915 | 67.576 | ||

| Total | 15 | 2925.177 | |||

| Generation time | |||||

| Between Groups | 3 | 12.974 | 4.325 | 5.826 | 0.011 |

| Residual | 12 | 8.908 | 0.742 | ||

| Total | 15 | 21.882 | |||

| Population growth rate | |||||

| Between Groups | 3 | 0.0191 | 0.00638 | 0.872 | 0.483 |

| Residual | 12 | 0.0879 | 0.00732 | ||

| Total | 15 | 0.107 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).