Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ1 : To what extent do different smoothing techniques influence risk-adjusted returns of single asset type portfolios of different asset classes?

- RQ2 : Which selection criteria best identify representative assets from clusters formed using risk-return characteristics of smoothed data?

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Portfolio Optimisation Techniques

2.1.1. Markowitz Mean - Variance (MV) Theory

2.1.2. Sharpe and Sortino Ratio

2.2. Portfolio Optimisation Using Meta Heuristic Algorithms

2.3. Clustering of Financial Assets

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Description

3.2. Dataset Pre-Processing

3.2.1. Handling Missing Values

3.2.2. Implementation of Smoothing Algorithms

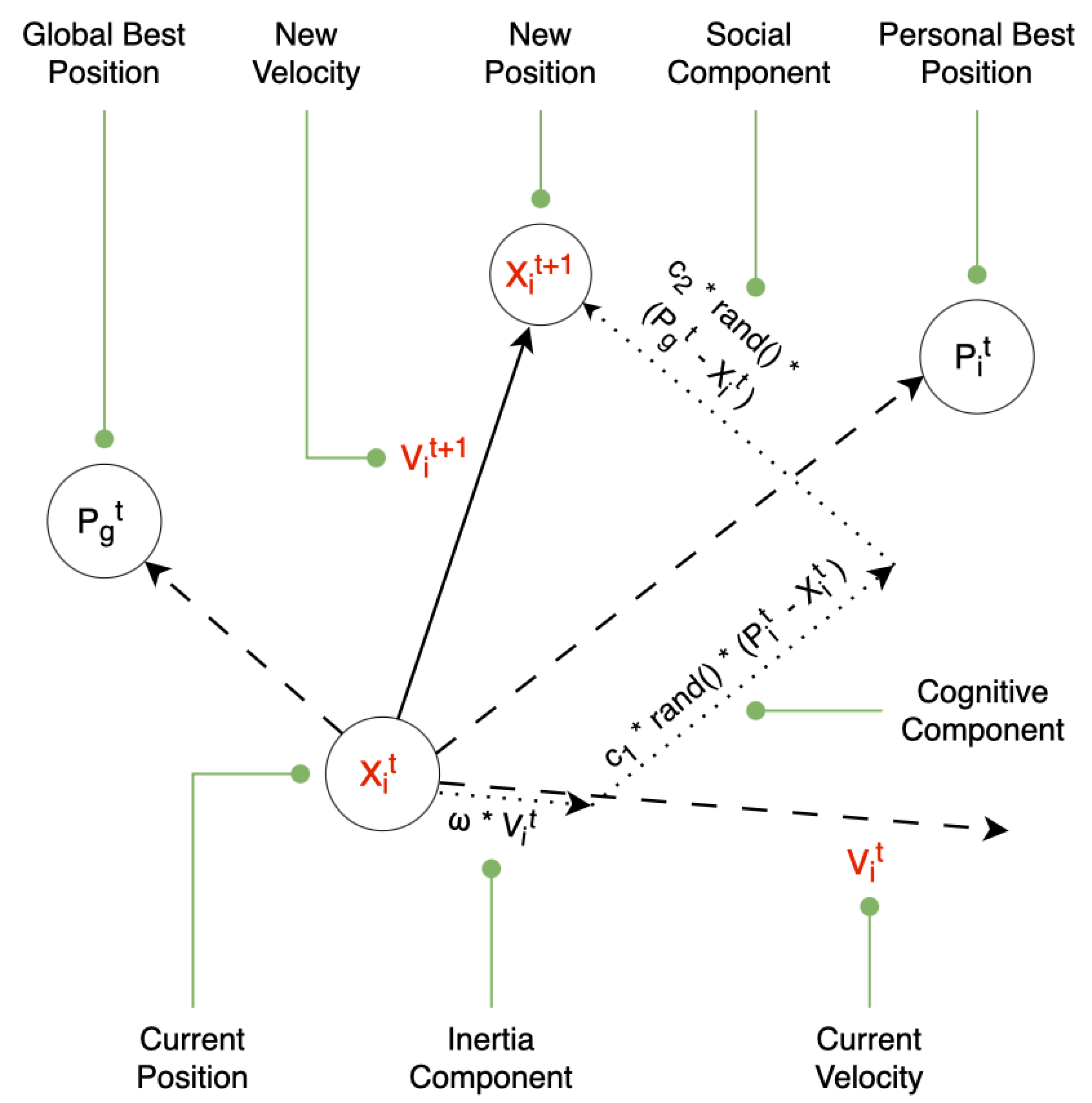

3.3. Meta - Heuristic Algorithm Used for Portfolio Optimisation - Particle Swarm Optimisation

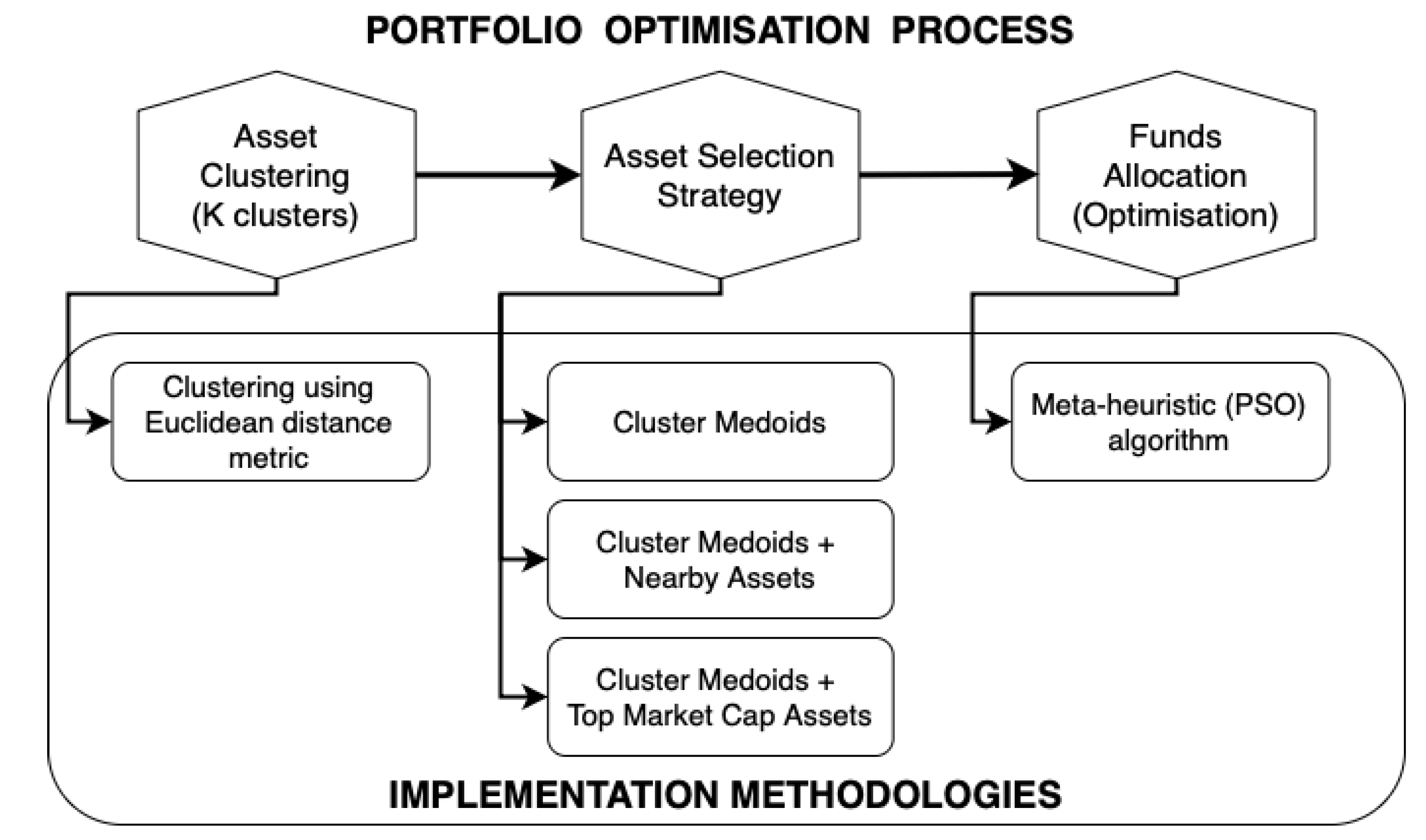

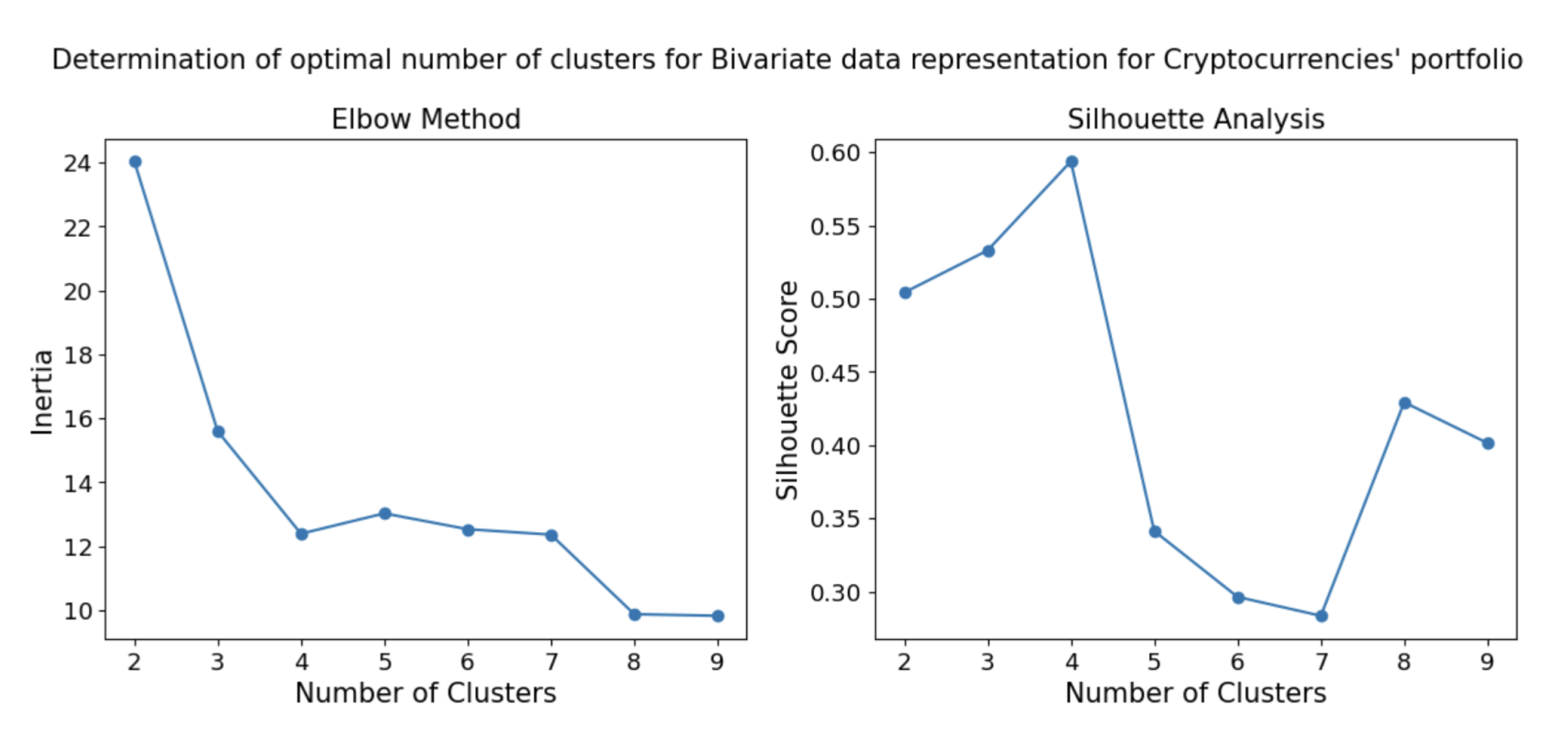

3.4. K-Medoids Based Clustering and Optimal Selection of Financial Assets

4. Results

4.1. Missing Value Handling Techniques

4.2. Analysis of Different Smoothing Strategies

4.3. Hyperparameter Optimisation for the Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO) Algorithm

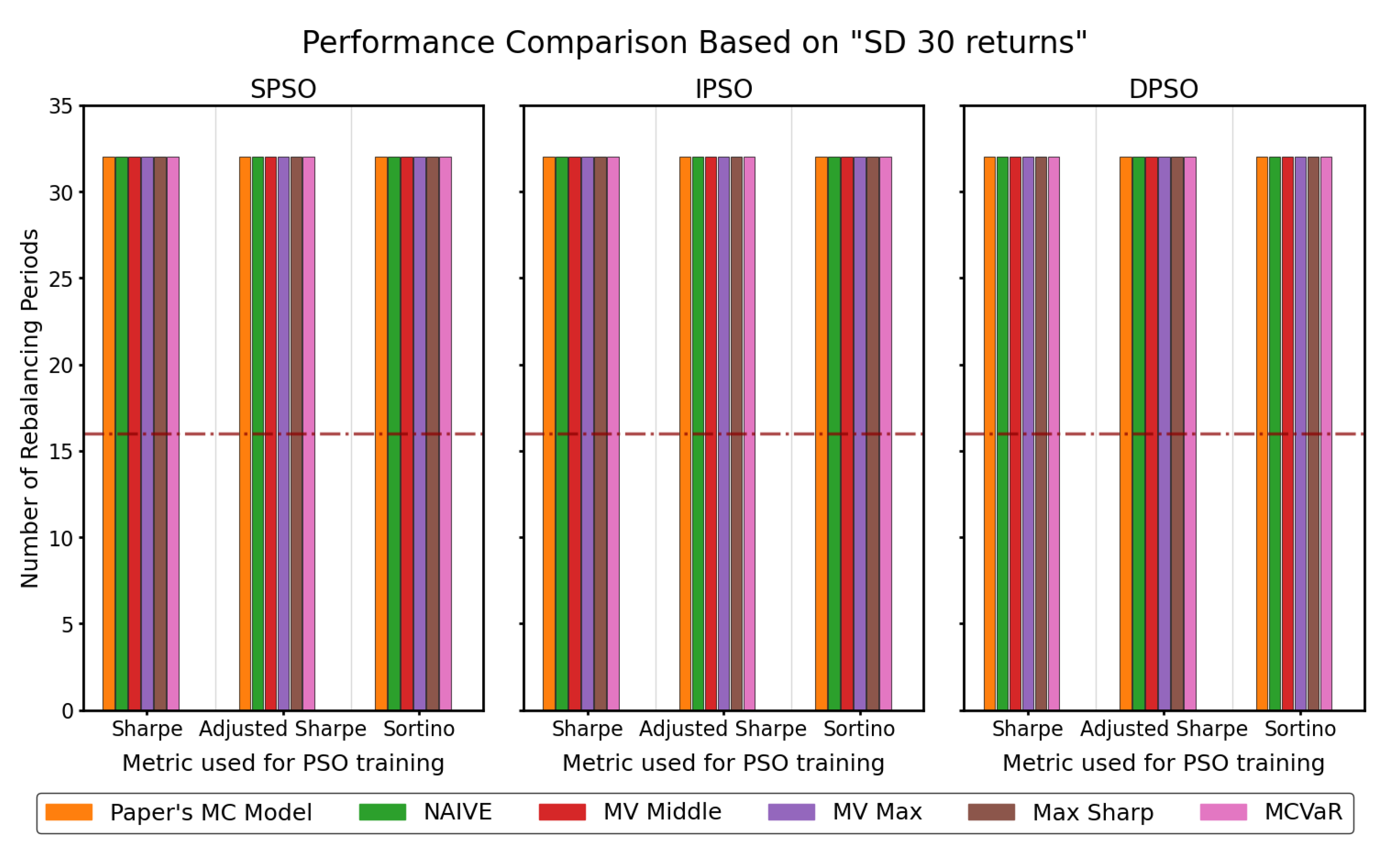

4.4. Benchmarking PSO with Previous Works

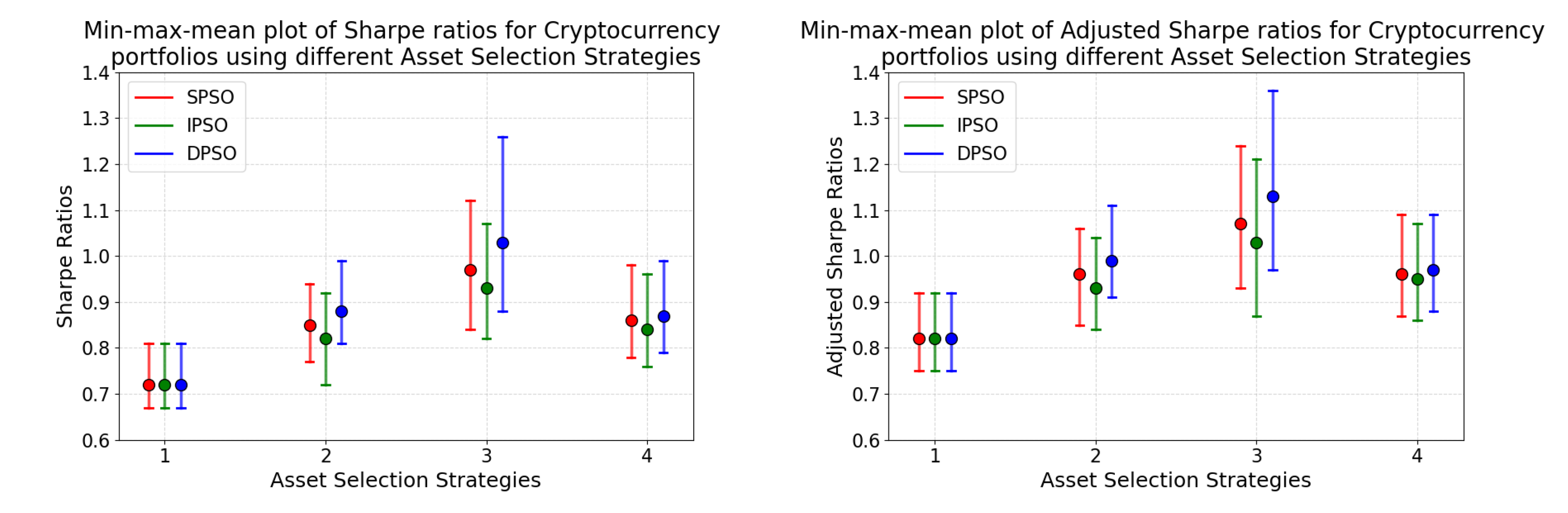

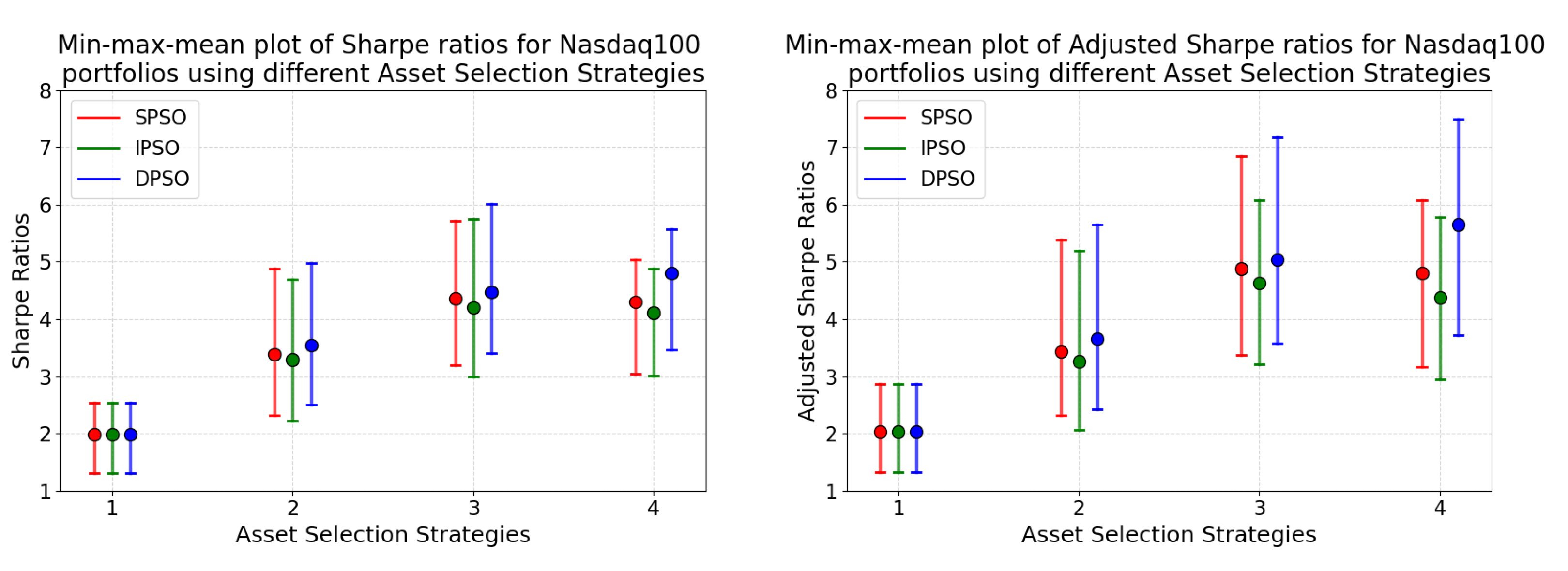

4.5. Analysis of the Effect of Clustering and Different Asset Selection Techniques

4.5.1. Comparison of the Effect of Clustering and Asset Selection Strategy Against Non-Clustered Approach on the Corresponding Portfolios

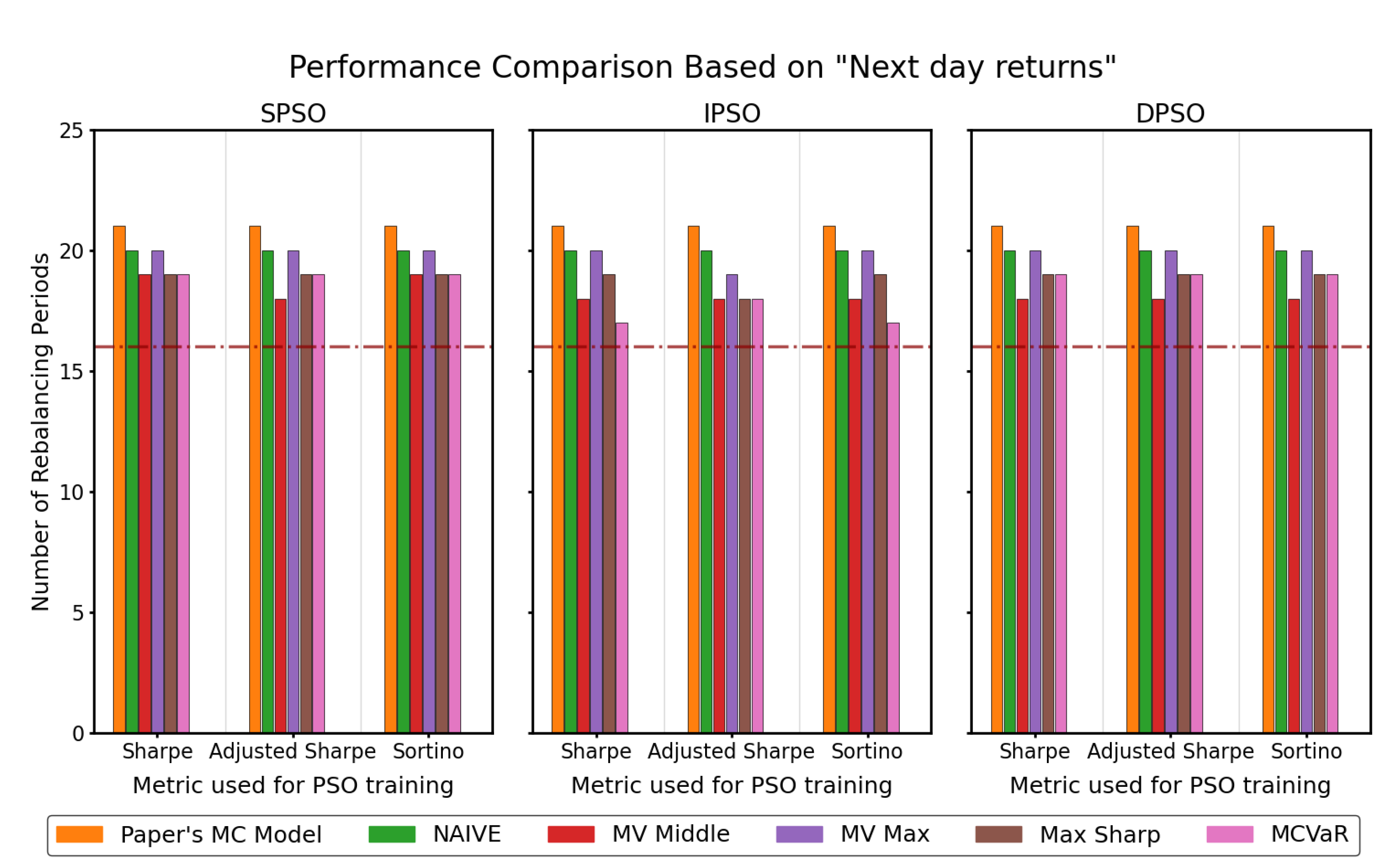

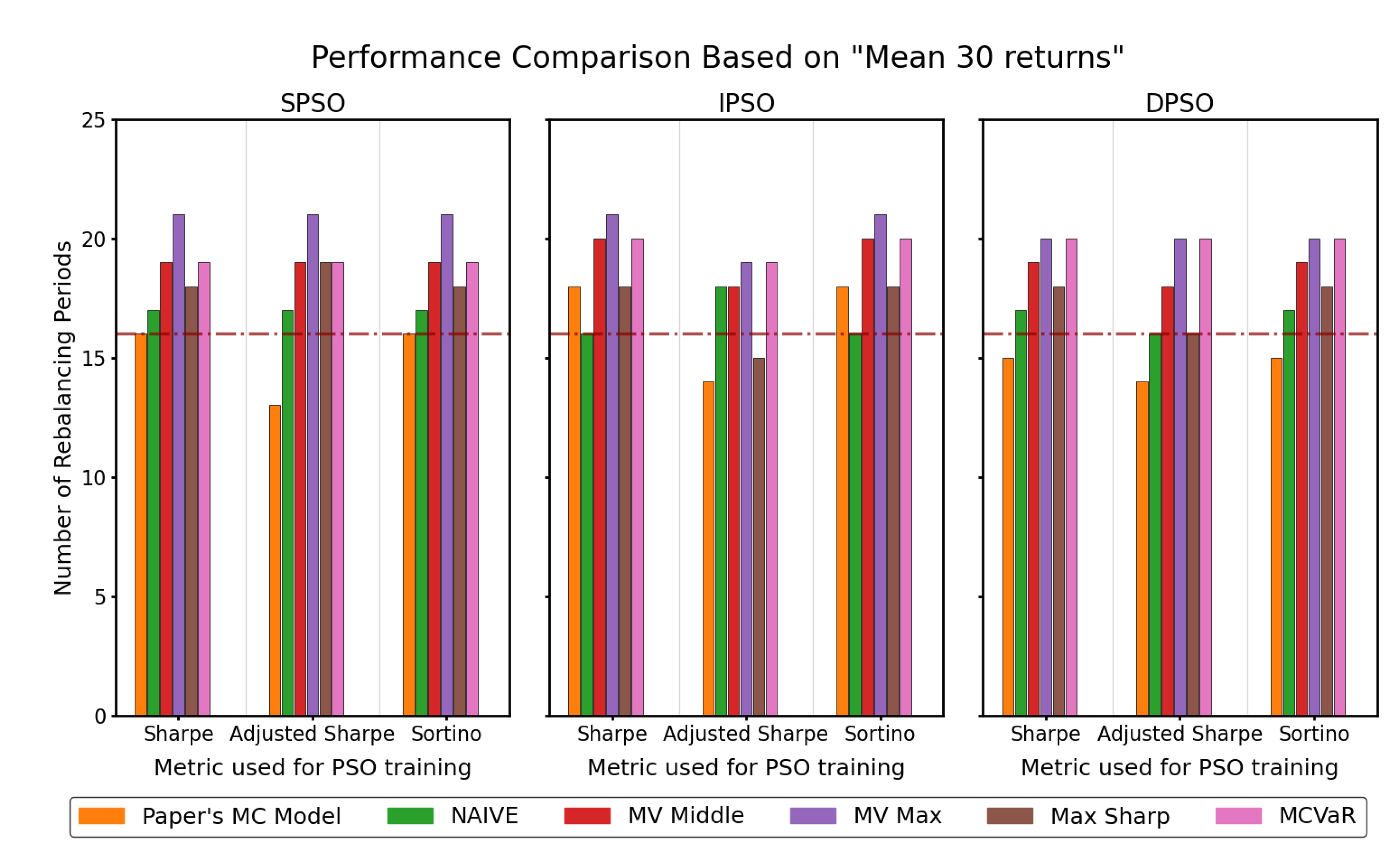

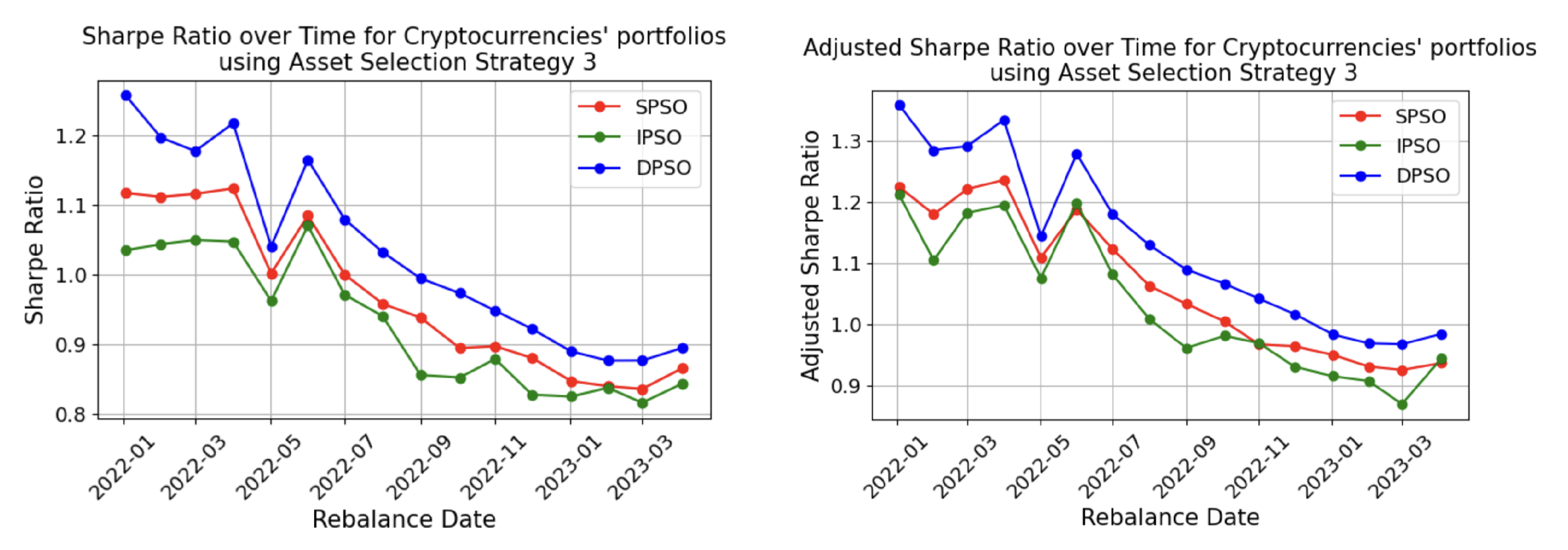

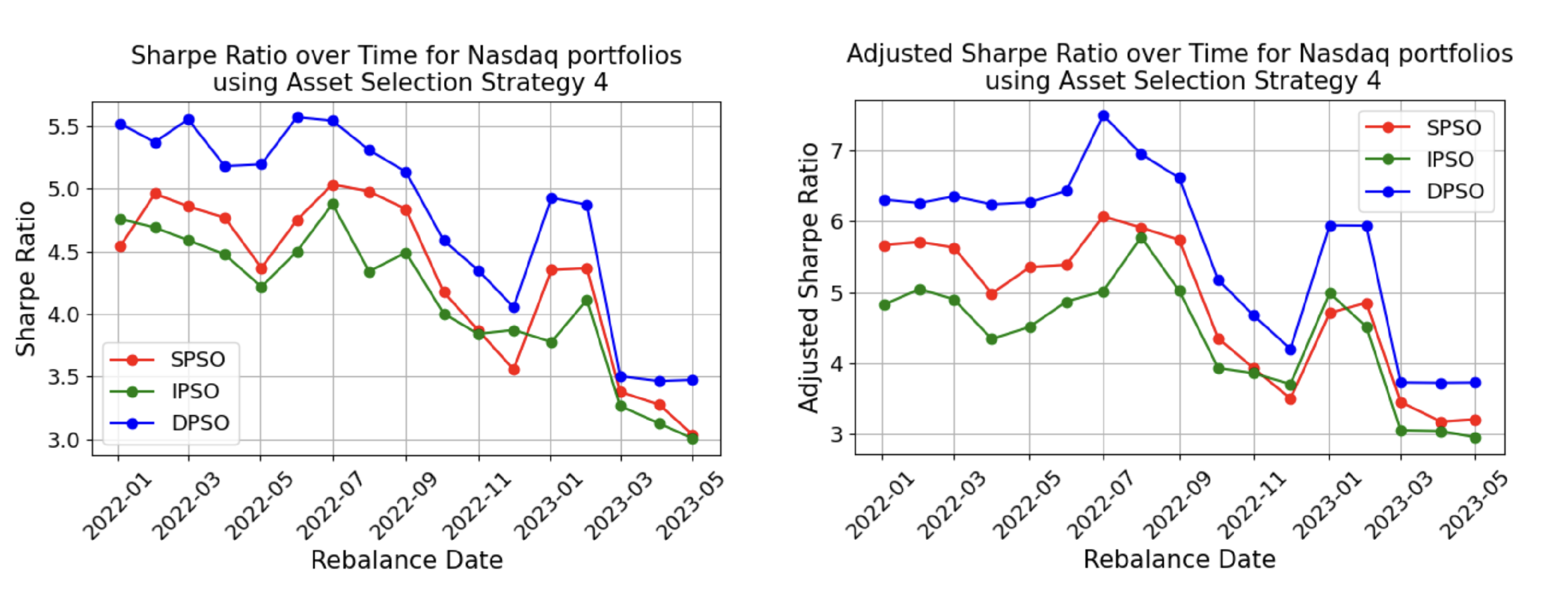

4.5.2. Comparison of Different PSO Techniques

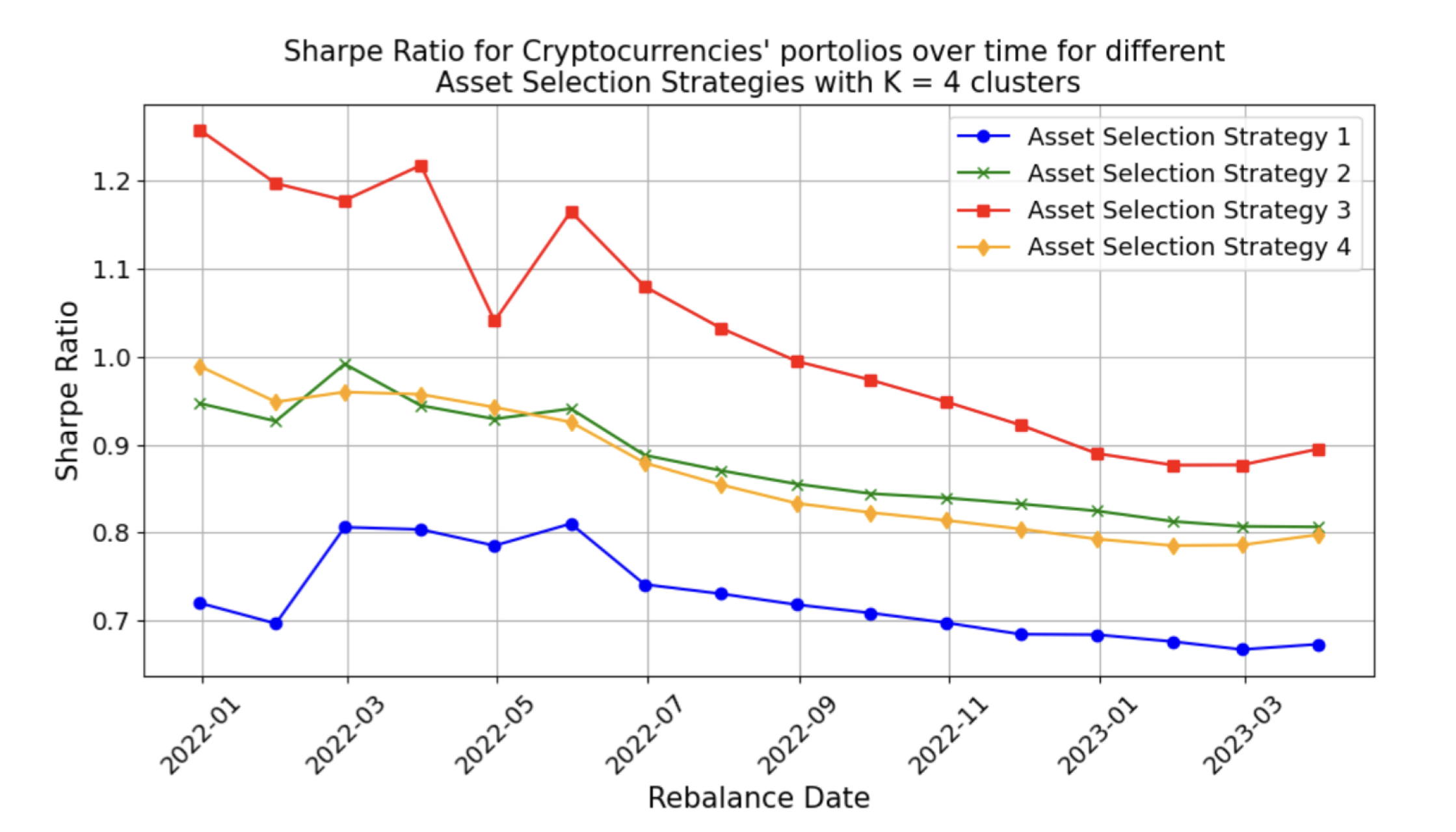

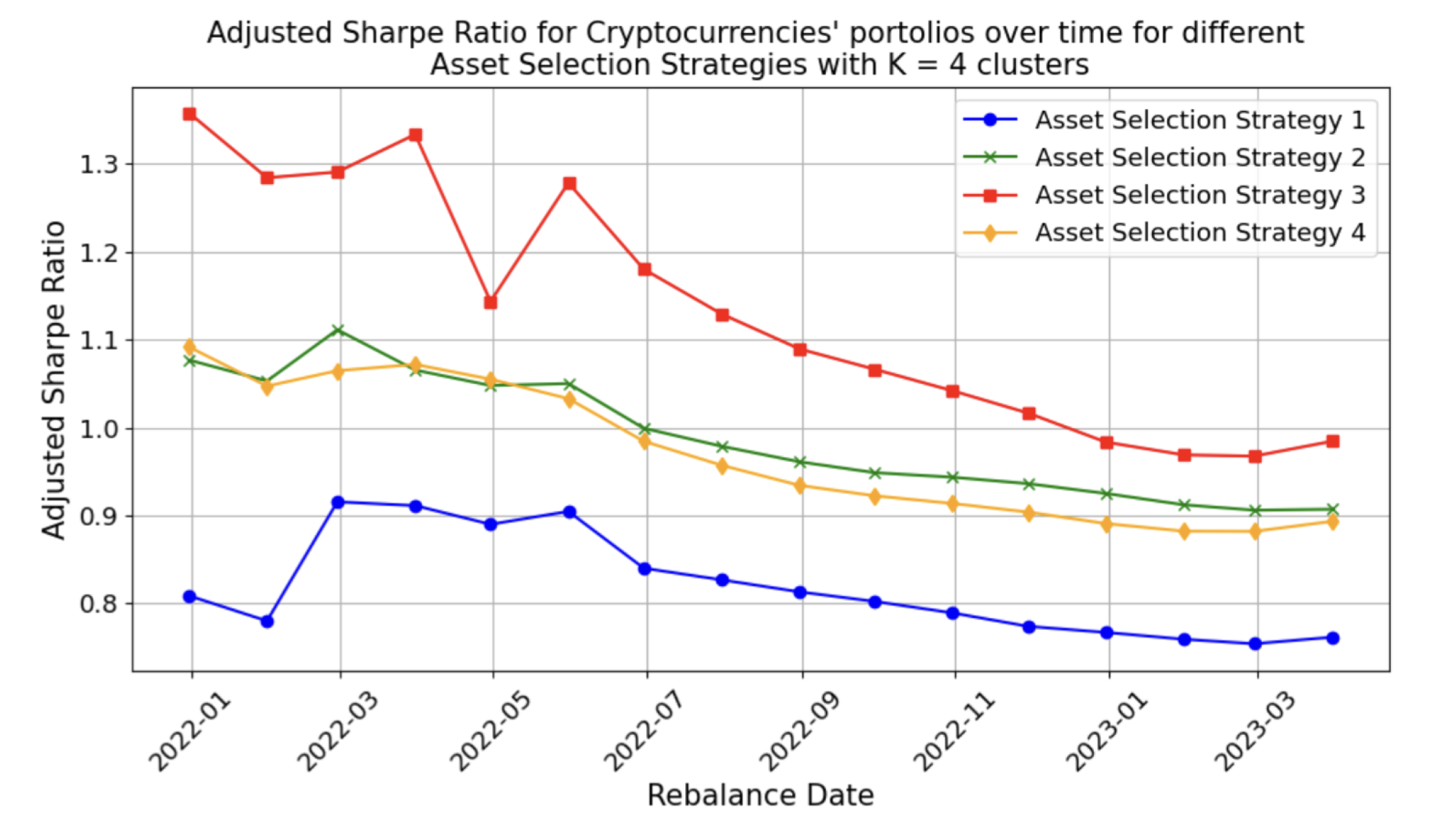

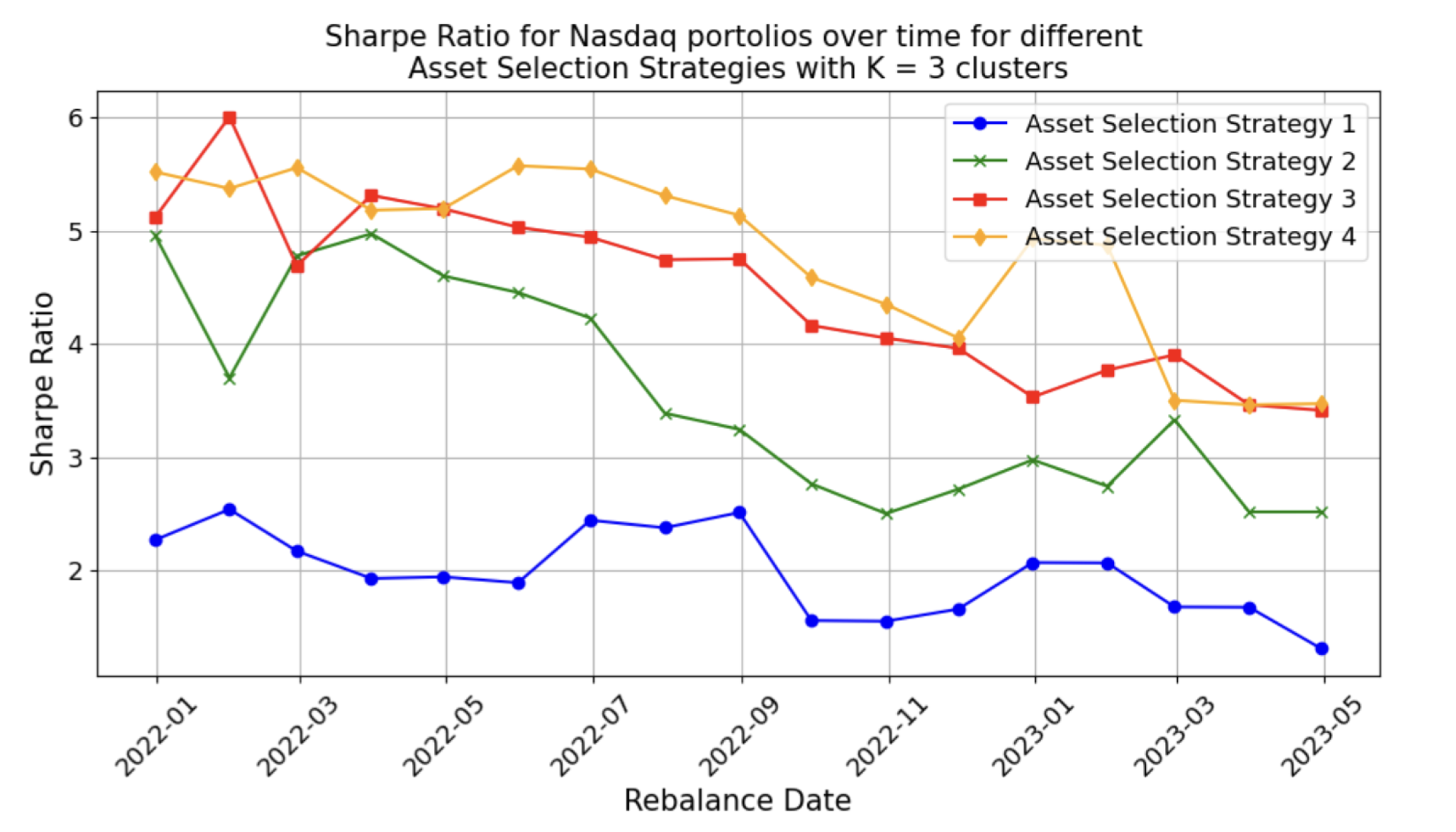

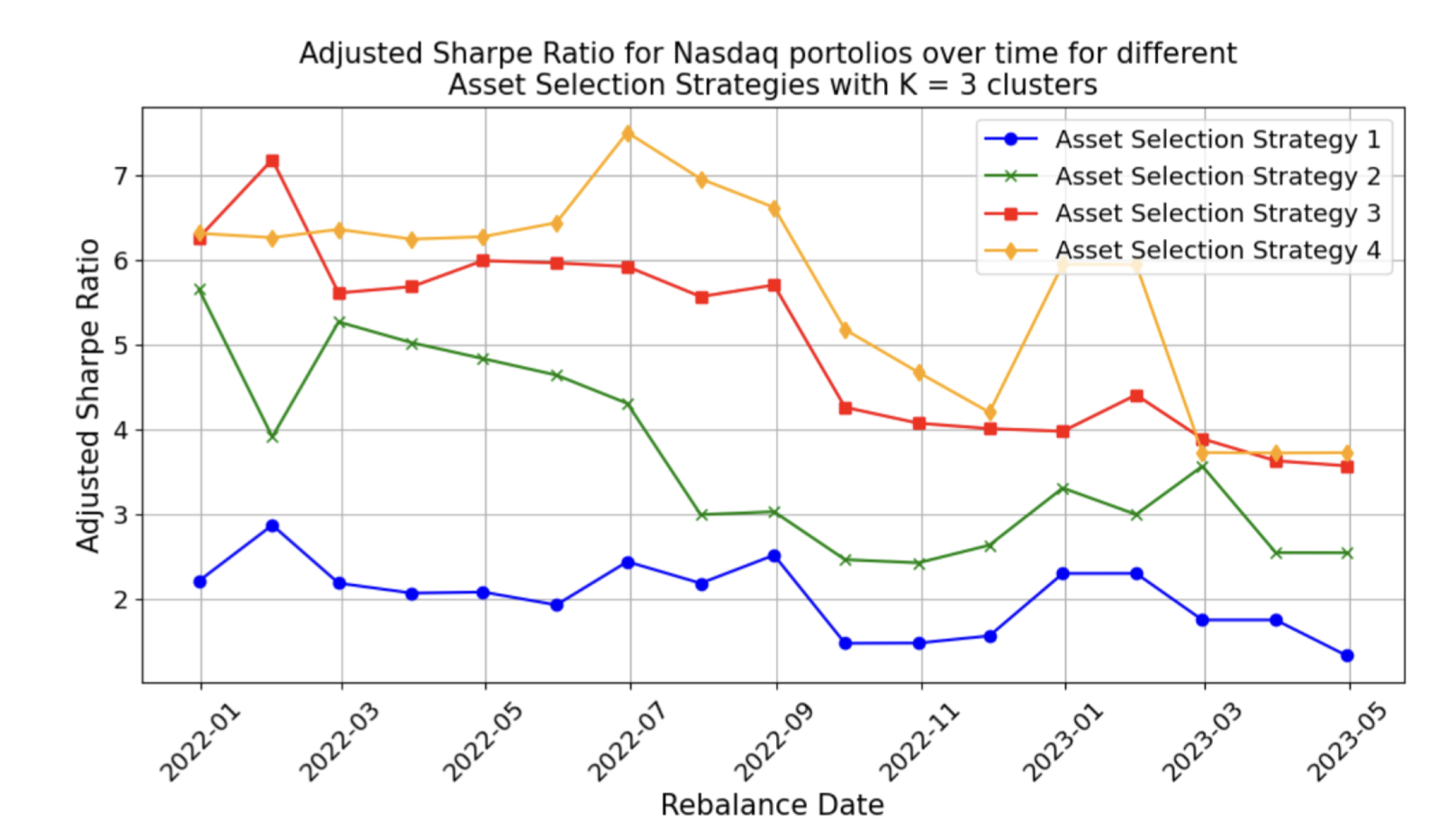

4.5.3. Comparison of Different Asset Selection Strategies

4.6. Benchmarking with Literature Review

5. Discussion and Conclusion

6. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Subset of Assets Used

| Top 10 Crypto coins | Top 20 S&P stocks | Top 20 S&P stocks |

|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin (BTC) | MICROSOFT CORP (MSFT) | APPLE INC (AAPL) |

| Ethereum (ETH) | NVIDIA CORP (NVDA) | AMAZON.COM, INC (AMZN) |

| Tether (USDT) | META PLATFORMS INC, CLASS A (META) | ALPHABET INC CL C (GOOG) |

| Ripple (XRP) | BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC. CL B (BRK.B) | ELI LILLY AND COMPANY (LLY) |

| USD Coin (USDC) | BROADCOM INC. (AVGO) | TESLA, INC (TSLA) |

| Dogecoin (DOGE) | JPMORGAN CHASE & COMPANY (JPM) | UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC (UNH) |

| Cardano (ADA) | VISA INC. (V) | EXXON MOBIL CORP (XOM) |

| Tron (TRX) | JOHNSON & JOHNSON (JNJ) | MASTERCARD INC (MA) |

| Litecoin (LTC) | THE PROCTER & GAMBLE COMPANY (PG) | HOME DEPOT, INC. (HD) |

| Dai (DAI) | MERCK COMPANY. INC. (MRK) | COSTCO WHOLESALE CORP (COST) |

Appendix B. Pseudocodes

Appendix B.1. Standard Particle Swarm Optimisation (SPSO) Algorithm

Appendix B.2. K-Medoids Clustering Algorithm

References

- Ta, V.D.; Liu, C.M.; Tadesse, D.A. Portfolio Optimization-Based Stock Prediction Using Long-Short Term Memory Network in Quantitative Trading. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, H.M.; Markowitz, H.M. Portfolio selection: efficient diversification of investments; J. Wiley, 1967.

- Sharpe, W.F. Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of Market Equilibrium Under Conditions of Risk. The Journal of Finance 1964, 19, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockafellar, R.T.; Uryasev, S. Optimization of conditional value-at-risk. The Journal of Risk 2000, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmakani, H.R.; Fazel, M. Constrained Portfolio Selection using Particle Swarm Optimization. Expert Systems with Applications 2011, 38, 8327–8335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Fan, Y.; Xiao, H.; Xue, B. Bacterial foraging based approaches to portfolio optimization with liquidity risk. Neurocomputing 2012, 98, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxiotis, K.; Liagkouras, K. Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithms for Portfolio Management: A comprehensive literature review. Expert Systems with Applications 2012, 39, 11685–11698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aithal, P.K.; Geetha, M.; U, D.; Savitha, B.; Menon, P. Real-Time Portfolio Management System Utilizing Machine Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 32545–32559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunjan, A.; Bhattacharyya, S. A brief review of portfolio optimization techniques. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 3847–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinold, R.C.; Kahn, R.N. Active portfolio management 2000.

- El Bernoussi, R.; Rockinger, M. Rebalancing with transaction costs: theory, simulations, and actual data. Financial Markets and Portfolio Management 2023, 37, 121–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, K. SECURITY ANALYSIS AND PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT, THIRD EDITION; PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd., 2022.

- Thakkar, A.; Chaudhari, K. A Comprehensive Survey on Portfolio Optimization, Stock Price and Trend Prediction Using Particle Swarm Optimization. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2021, 28, 2133–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nti, I.K.; Adekoya, A.F.; Weyori, B.A. A systematic review of fundamental and technical analysis of stock market predictions. Artificial Intelligence Review 2020, 53, 3007–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.; Chaudhari, K. CREST: Cross-Reference to Exchange-based Stock Trend Prediction using Long Short-Term Memory. Procedia Computer Science 2020, 167, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbalagan, T.; Maheswari, S.U. Classification and Prediction of Stock Market Index Based on Fuzzy Metagraph. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 47, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Yang, Z.; Song, Y.; Jia, P. Automatic stock decision support system based on box theory and SVM algorithm. Expert systems with Applications 2010, 37, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudys, A.; Lenčiauskas, V.; Malčius, E. Moving averages for financial data smoothing. In Proceedings of the Information and Software Technologies: 19th International Conference, ICIST 2013, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2013, October 2013. Proceedings 19. Springer; pp. 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cesarone, F.; Scozzari, A.; Tardella, F. A new method for mean-variance portfolio optimization with cardinality constraints. Annals of Operations Research 2013, 205, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Q.Y.E.; Cao, Q.; Quek, C. Dynamic portfolio rebalancing through reinforcement learning. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 7125–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ahmad, F.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z. Portfolio optimization in the era of digital financialization using cryptocurrencies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2020, 161, 120265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, L.; Arroyo, J. Online risk-based portfolio allocation on subsets of crypto assets applying a prototype-based clustering algorithm. Financial Innovation 2023, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menvouta, E.J.; Serneels, S.; Verdonck, T. Portfolio optimization using cellwise robust association measures and clustering methods with application to highly volatile markets. The Journal of Finance and Data Science 2023, 9, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoodi, A.I. Cryptocurrency portfolio allocation using a novel hybrid and predictive big data decision support system. Omega 2023, 115, 102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.G. Cross-asset relations, correlations and economic implications. Global Finance Journal 2019, 41, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeevi, A.; Mashal, R. Beyond correlation: Extreme co-movements between financial assets. Available at SSRN 317122 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Koumou, G.B. Diversification and portfolio theory: a review. Financial Markets and Portfolio Management 2020, 34, 267–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolun Tayalı, S. A novel backtesting methodology for clustering in mean–variance portfolio optimization. Knowledge-Based Systems 2020, 209, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. Available online: https://home.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/interest-rates/TextView?type=daily_treasury_bill_rates&field_tdr_date_value=2023. Accessed on 24. 20 April.

- Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for the constrained portfolio optimization problem. Expert Systems with Applications 2011, 38, 10161–10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, K.B.; Abd Aziz, M.I.B.; Kashif, A.N.; Raza, S.M.M. Two stage portfolio selection and optimization model with the hybrid particle swarm optimization. Matematika.

- Sun, J.; Fang, W.; Wu, X.; Lai, C.H.; Xu, W. Solving the multi-stage portfolio optimization problem with a novel particle swarm optimization. Expert Systems with Applications 2011, 38, 6727–6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortino, F.A.; Price, L.N. Performance measurement in a downside risk framework. the Journal of Investing 1994, 3, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.H.; Lopez de Prado, M. The Sharpe ratio efficient frontier. Journal of Risk 2012, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Shah, J. Dealing with the limitations of the Sharpe ratio for portfolio evaluation. Journal of Commerce and Accounting Research 2013, 2, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Cuchieri, N. Deep reinforcement learning for financial portfolio optimisation. Master’s thesis, University of Malta, 2021.

- Sharma, A.; Mehra, A. Financial analysis based sectoral portfolio optimization under second order stochastic dominance. Annals of Operations Research 2017, 256, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.J.; Meade, N.; Beasley, J.E.; Sharaiha, Y.M. Heuristics for cardinality constrained portfolio optimisation. Computers & Operations Research 2000, 27, 1271–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaerf, A. Local Search Techniques for Constrained Portfolio Selection Problems. Computational Economics 2002, 20, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks, 1995, Vol. [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Maniezzo, V.; Colorni, A. Ant system: optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 1996, 26, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikhar, P.A. Evolutionary algorithms: A critical review and its future prospects. In Proceedings of the 2016 International conference on global trends in signal processing, information computing and communication (ICGTSPICC). IEEE; 2016; pp. 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.L.; Horng, S.J.; Kao, T.W.; Chen, Y.H.; Run, R.S.; Chen, R.J.; Lai, J.L.; Kuo, I.H. An efficient job-shop scheduling algorithm based on particle swarm optimization. Expert Systems with Applications 2010, 37, 2629–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Zhang, M.; Johnston, M.; Tan, K.C. Automatic Programming via Iterated Local Search for Dynamic Job Shop Scheduling. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2015, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernbumroong, S.; Cang, S.; Yu, H. Genetic Algorithm-Based Classifiers Fusion for Multisensor Activity Recognition of Elderly People. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2015, 19, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Liu, T.K.; Chou, J.H. A Novel Crowding Genetic Algorithm and Its Applications to Manufacturing Robots. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2014, 10, 1705–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S.; Talatahari, S.; Alavi, A.H. Metaheuristic Applications in Structures and Infrastructures; Newnes, 2013.

- Ertenlice, O.; Kalayci, C.B. A survey of swarm intelligence for portfolio optimization: Algorithms and applications. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2018, 39, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, J. Swarm intelligence algorithms for portfolio optimization problems: Overview and recent advances. Mobile Information Systems 2022, 2022, 4241049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, K.; Engelbrecht, A. Meta-heuristics for portfolio optimization. Soft Computing 2023, 27, 19045–19073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.F.; Lin, W.T.; Lo, C.C. Markowitz-based portfolio selection with cardinality constraints using improved particle swarm optimization. Expert Systems with Applications 2012, 39, 4558–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Dai, H. A Simple and Fast Particle Swarm Optimization and Its Application on Portfolio Selection. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Workshop on Intelligent Systems and Applications; 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ni, Q.; Zhai, Y. A novel PSO for portfolio optimization based on heterogeneous multiple population strategy. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC); 2015; pp. 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, B.y. Complex portfolio selection using improving particle swarm optimization approach. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications; 2018, IEEE 16th International Conference on Smart City; IEEE 4th International Conference on Data Science and Systems (HPCC/SmartCity/DSS). IEEE; pp. 828–835.

- Chang, T.J.; Meade, N.; Beasley, J.E.; Sharaiha, Y.M. Heuristics for cardinality constrained portfolio optimisation. Computers & Operations Research 2000, 27, 1271–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Koshino, M.; Murata, H.; Kimura, H. Improved particle swarm optimization and application to portfolio selection. Electronics and Communications in Japan (Part III: Fundamental Electronic Science) 2007, 90, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsich, A.; Jaimes, A.L.; Coello, C.A.C. A survey on multiobjective evolutionary algorithms for the solution of the portfolio optimization problem and other finance and economics applications. IEEE Transactions on evolutionary computation 2012, 17, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, S.; Lai, K.K. Portfolio optimization using evolutionary algorithms. In Reflexing Interfaces: The Complex Coevolution of Information Technology Ecosystems; IGI Global, 2008; pp. 235–245.

- Chen, A.H.L.; Liang, Y.C.; Liu, C.C. Portfolio optimization using improved artificial bee colony approach. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence for Financial Engineering &, 2013, Economics (CIFEr); pp. 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Kalayci, C.B.; Polat, O.; Akbay, M.A. An efficient hybrid metaheuristic algorithm for cardinality constrained portfolio optimization. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2020, 54, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machdar, N.M. The Effect of Capital Structure, Systematic Risk, and Unsystematic Risk on Stock Return. Business and Entrepreneurial Review 2015, 14, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.Z.; Comin, C.H.; Casanova, D.; Bruno, O.M.; Amancio, D.R.; Costa, L.d.F.; Rodrigues, F.A. Clustering algorithms: A comparative approach. PloS one 2019, 14, e0210236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine learning: Algorithms, real-world applications and research directions. SN computer science 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenkam, H.M.; Mba, J.C.; Mwambi, S.M. Optimization and Diversification of Cryptocurrency Portfolios: A Composite Copula-Based Approach. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 6408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rdusseeun, L.; Kaufman, P. Clustering by means of medoids. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the statistical data analysis based on the L1 norm conference, Neuchatel, Switzerland, 1987, Vol.

- Duarte, F.G.; De Castro, L.N. A Framework to Perform Asset Allocation Based on Partitional Clustering. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 110775–110788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Deepali. ; Varshney, S. Analysis of K-Means and K-Medoids Algorithm For Big Data. Procedia Computer Science 2016, 78, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez de Prado, M. Building diversified portfolios that outperform out-of-sample. Journal of Portfolio Management 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, J.; Thös, A.K. Risk reduction and portfolio optimization using clustering methods. Econometrics and Statistics 2024, 32, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, I.; Jong, H.; Rim, W.; et al. Portfolio Optimization Based on K-Means Clustering and Particle Swarm Optimization Using Financial Statements and Stock Price Data.

- Bjerring, T.T.; Ross, O.; Weissensteiner, A. Feature selection for portfolio optimization. Annals of Operations Research 2017, 256, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.R.; Mahanty, B.; Tiwari, M.K. Clustering Indian stock market data for portfolio management. Expert Systems with Applications 2010, 37, 8793–8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdek, J.C.; Pal, N.R. Cluster validation with generalized Dunn’s indices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 1995 second New Zealand international two-stream conference on artificial neural networks and expert systems. IEEE; 1995; pp. 190–193. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, M.M.; Young, M.N.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Taylar, J.V. Stock market optimization amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: Technical analysis, K-means algorithm, and mean-variance model (TAKMV) approach. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Wu, S. Construction of stock portfolios based on k-means clustering of continuous trend features. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 252, 109358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.R.; Huang, W.K.; Yeh, S.K. Particle swarm optimization approach to portfolio construction. Intelligent Systems in Accounting, Finance and Management 2021, 28, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data, F. Complete Intraday Bundle. Available online: https://firstratedata.com/cb/1/complete-us-stocks-index-etf-futures. Accessed on. 30 April.

- Ta, V.D.; Liu, C.M.; Tadesse, D.A. Portfolio optimization-based stock prediction using long-short term memory network in quantitative trading. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platanakis, E.; Urquhart, A. Should investors include bitcoin in their portfolios? A portfolio theory approach. The British accounting review 2020, 52, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOUIS, F.R.B.O.S. 3-Month Treasury Bill Secondary Market Rate, Discount Basis (TB3MS). Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TB3MS#0. Accessed on. 30 May.

- Top 25 Stocks in the S&P 500 By Index Weight for March 2025. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/best-25-sp500-stocks-8550793. Accessed on. 9 April.

- Elton, E.J. Presidential Address: Expected Return, Realized Return, and Asset Pricing Tests. The Journal of Finance 1999, 54, 1199–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily Returns Meaning. Available online: https://www.stockopedia.com/ratios/daily-volatility-12000/. Accessed on 24. 20 October.

- Peng, J.; Hahn, J.; Huang, K.W. Handling missing values in information systems research: A review of methods and assumptions. Information Systems Research 2023, 34, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, I.; Permanasari, A.E.; Ardiyanto, I.; Indrayani, R. A review of missing values handling methods on time-series data. In Proceedings of the 2016 international conference on information technology systems and innovation (ICITSI). IEEE; 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, A.; Tao, X.; Chou, C.C.; Yu, D. Are missing values important for earnings forecasts? A machine learning perspective. Quantitative finance 2022, 22, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofman, P.; Sharpe, I.G. Using multiple imputation in the analysis of incomplete observations in finance. Journal of Financial Econometrics 2003, 1, 216–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.Y.; McCoy, J. Missing values handling for machine learning portfolios. Journal of Financial Economics 2024, 155, 103815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Zeng, Y.; Yuan, J. Two-stage stock portfolio optimization based on AI-powered price prediction and mean-CVaR models. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 255, 124555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Saxena, V. Understanding stock market trends using simple moving average (SMA) and exponential moving average (EMA) indicators. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I). IEEE, Vol. 6; 2023; pp. 1931–1935. [Google Scholar]

- Time series and moving averages. Available online: https://www.accaglobal.com/ie/en/student/exam-support-resources/fundamentals-exams-study-resources/f5/technical-articles/time-series.html#:%5C~:text=The%5C%20first%5C%20four%5C%20observations%5C%20are,together%5C%20and%5C%20dividing%5C%20by%5C%20two. Accessed on 24. 20 October.

- Amal, M.A.; Napitupulu, H.; et al. Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Determining Global Optima of Investment Portfolio Weight Using Mean-Value-at-Risk Model in Banking Sector Stocks. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Chen, W.; Yang, L. Improved Particle Swarm Optimization for Realistic Portfolio Selection. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking, 2007, Vol. 1, and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD 2007); pp. 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Črepinšek, M.; Liu, S.H.; Mernik, M. Exploration and exploitation in evolutionary algorithms: A survey. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2013, 45, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Chen, W.; Yang, L. Improved particle swarm optimization for realistic portfolio selection. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking, 2007, Vol. 1, and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD 2007). IEEE; pp. 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, D.; Lopes, L.G.; Morgado-Dias, F. Particle swarm optimisation: a historical review up to the current developments. Entropy 2020, 22, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mean-Variance Optimization. Available online: https://pyportfolioopt.readthedocs.io/en/latest/MeanVariance.html. Accessed on 23. 20 July.

- Jensen, T.I.; Kelly, B.T.; Malamud, S.; Pedersen, L.H. Machine learning and the implementable efficient frontier. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.C. An analytic derivation of the efficient portfolio frontier. Journal of financial and quantitative analysis 1972, 7, 1851–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Efficient Frontier. Available online: https://pyportfolioopt.readthedocs.io/en/latest/GeneralEfficientFrontier.html. Accessed on 23. 20 July.

- Lorenzo, L.; Arroyo, J. Analysis of the cryptocurrency market using different prototype-based clustering techniques. Financial Innovation 2022, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, R.L. Who belongs in the family? Psychometrika 1953, 18, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutaywi, M.; Kachouie, N.N. Silhouette analysis for performance evaluation in machine learning with applications to clustering. Entropy 2021, 23, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- sklearn extra K-Medoids. Available online: https://scikit-learn-extra.readthedocs.io/en/stable/generated/sklearn_extra.cluster.KMedoids.html. Accessed on 24. 20 October.

- Understanding Small-Cap and Big-Cap Stocks. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/insights/understanding-small-and-big-cap-stocks/. Accessed on 24. 20 October.

- Sanderson, R.; Lumpkin-Sowers, N.L. Buy and hold in the new age of stock market volatility: A story about ETFs. International Journal of Financial Studies 2018, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.L. The random walk hypothesis, portfolio analysis and the buy-and-hold criterion. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 1968, 3, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, F.D.; Cardoso, R.T.N.; Hanaoka, G.P.; Duarte, W.M. Decision-making for financial trading: A fusion approach of machine learning and portfolio selection. Expert Systems with Applications 2019, 115, 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzokem, A.; Maposa, D. Bitcoin versus s&p 500 index: Return and risk analysis. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2024, 29, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Caferra, R.; Vidal-Tomás, D. Who raised from the abyss? A comparison between cryptocurrency and stock market dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters 2021, 43, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brini, A.; Lenz, J. A comparison of cryptocurrency volatility-benchmarking new and mature asset classes. Financial Innovation 2024, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Monsalve, S.; Suárez-Cetrulo, A.L.; Cervantes, A.; Quintana, D. Convolution on neural networks for high-frequency trend prediction of cryptocurrency exchange rates using technical indicators. Expert Systems with Applications 2020, 149, 113250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Source code for Efficient Frontier class in Python. Available online: https://pyportfolioopt.readthedocs.io/en/latest/_modules/pypfopt/efficient_frontier/efficient_frontier.html. Accessed on 24. 20 October.

- Aljinović, Z.; Marasović, B.; Šestanović, T. Cryptocurrency portfolio selection—a multicriteria approach. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoinMarketCap - Cryptocurrency Prices by Market Cap. Available online: coinmarketcap.com. Accessed on. 7 July.

- The 100 largest companies in the world by market capitalization in 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/263264/top-companies-in-the-world-by-market-capitalization/. Accessed on 25. 20 January.

- Kim, Y.B.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, W.; Im, J.H.; Kim, T.H.; Kang, S.J.; Kim, C.H. Predicting fluctuations in cryptocurrency transactions based on user comments and replies. PloS one 2016, 11, e0161197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stocks Only | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| SPSO | IPSO | DPSO | Paper |

| 4.8832 | 4.8802 | 4.8843 | 1.27 |

| SharpeSortino | Asset Select 1 | Asset Select 2 | Asset Select 3 | Asset Select 4 | Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 10 | 12.513.31 | 12.443.22 | 13.123.47 | 12.363.24 | 1.8371.81 |

| n = 25 | 12.843.50 | 13.033.44 | 14.833.79 | 11.733.10 | 2.7172.398 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).