Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

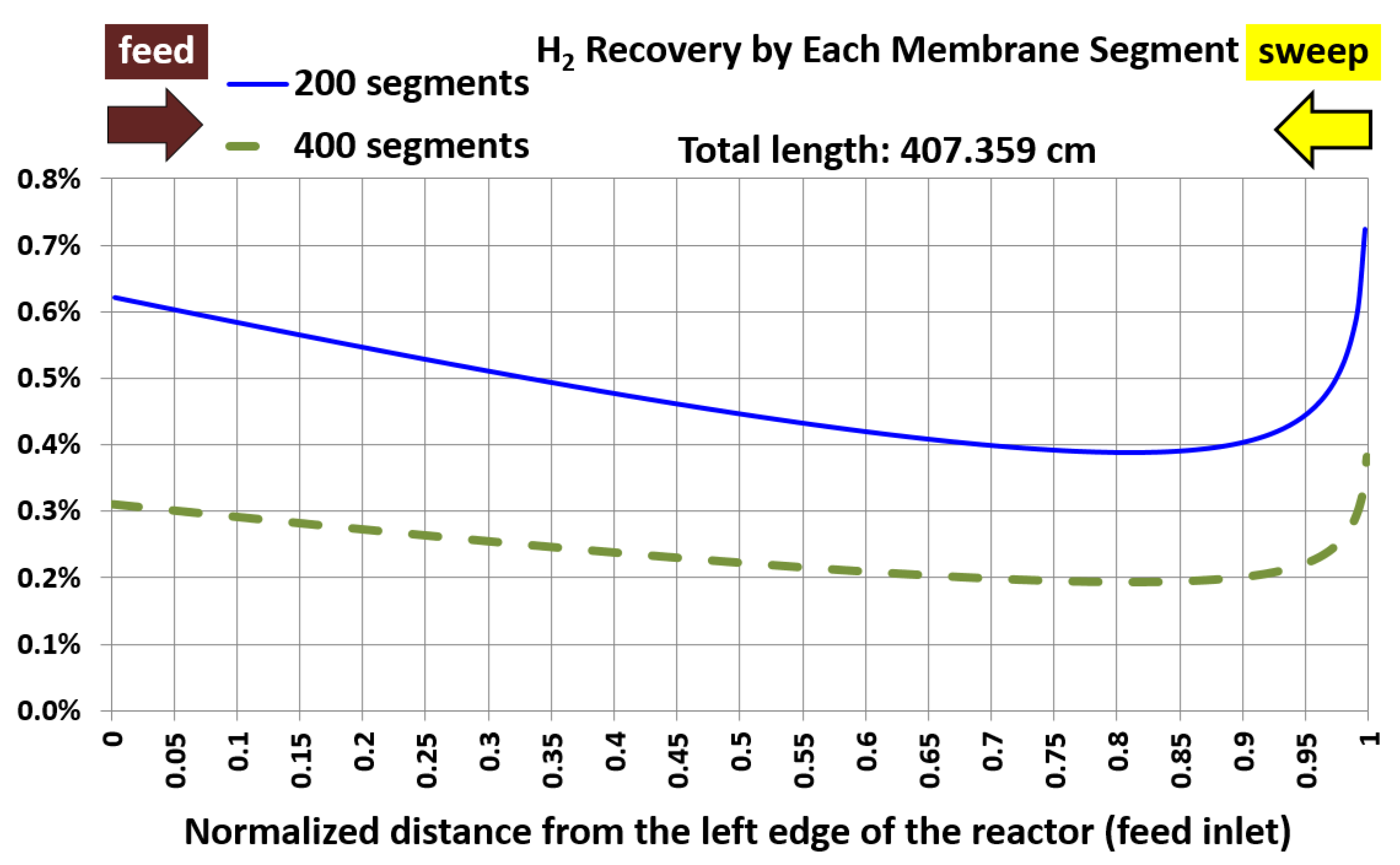

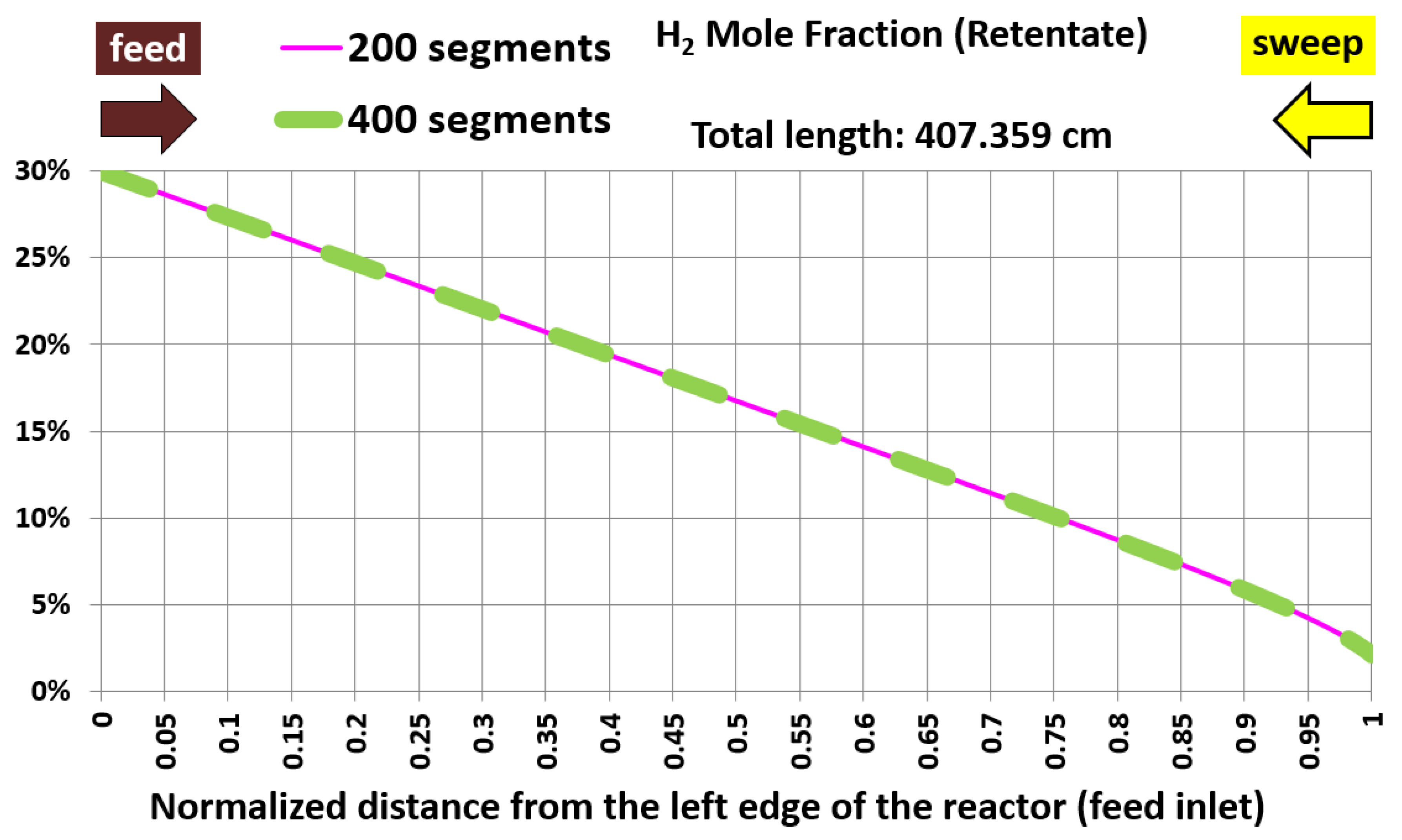

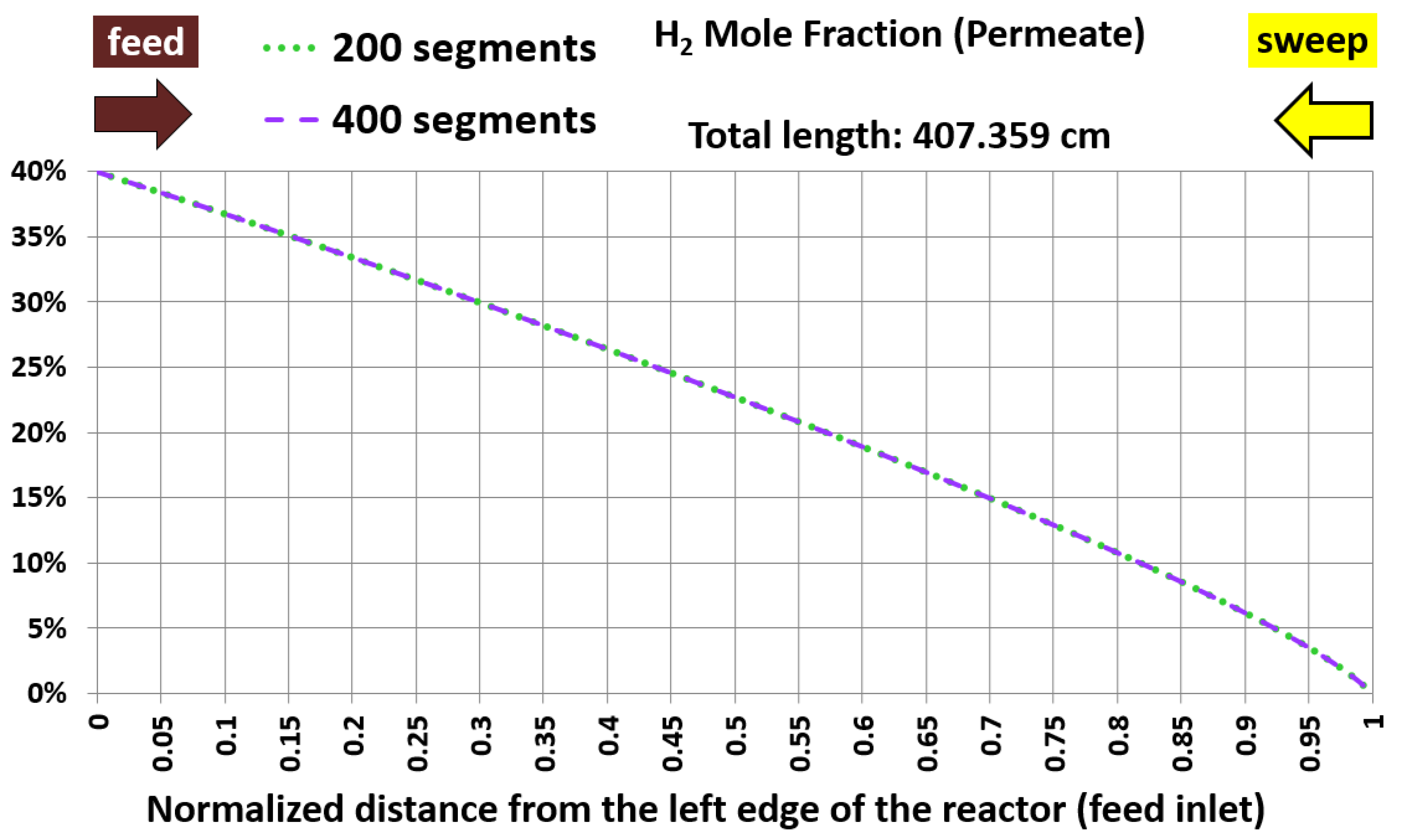

- Presenting a simple plug-flow reactor computational model for the membrane-based hydrogen separation, which takes a short time to give rough predictions as a precursor of time-consuming three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models. The simple plug-flow reactor model can be automated using spreadsheet software without the resorting to complicated computer programming or expensive software packages. It was checked for accuracy in terms of spatial resolution, and it passed successfully a resolution-independence test.

- Providing results of a representative case of hydrogen separation out of a feedstock flow of pressurized syngas, giving insights about the distribution of the permeation flux along the unit, when 95% hydrogen recovery is attained

- Demonstrating examples of consolidated metrics for comparing and judging the permeation performance of hydrogen. This can guide researchers when analyzing or interpreting similar problems.

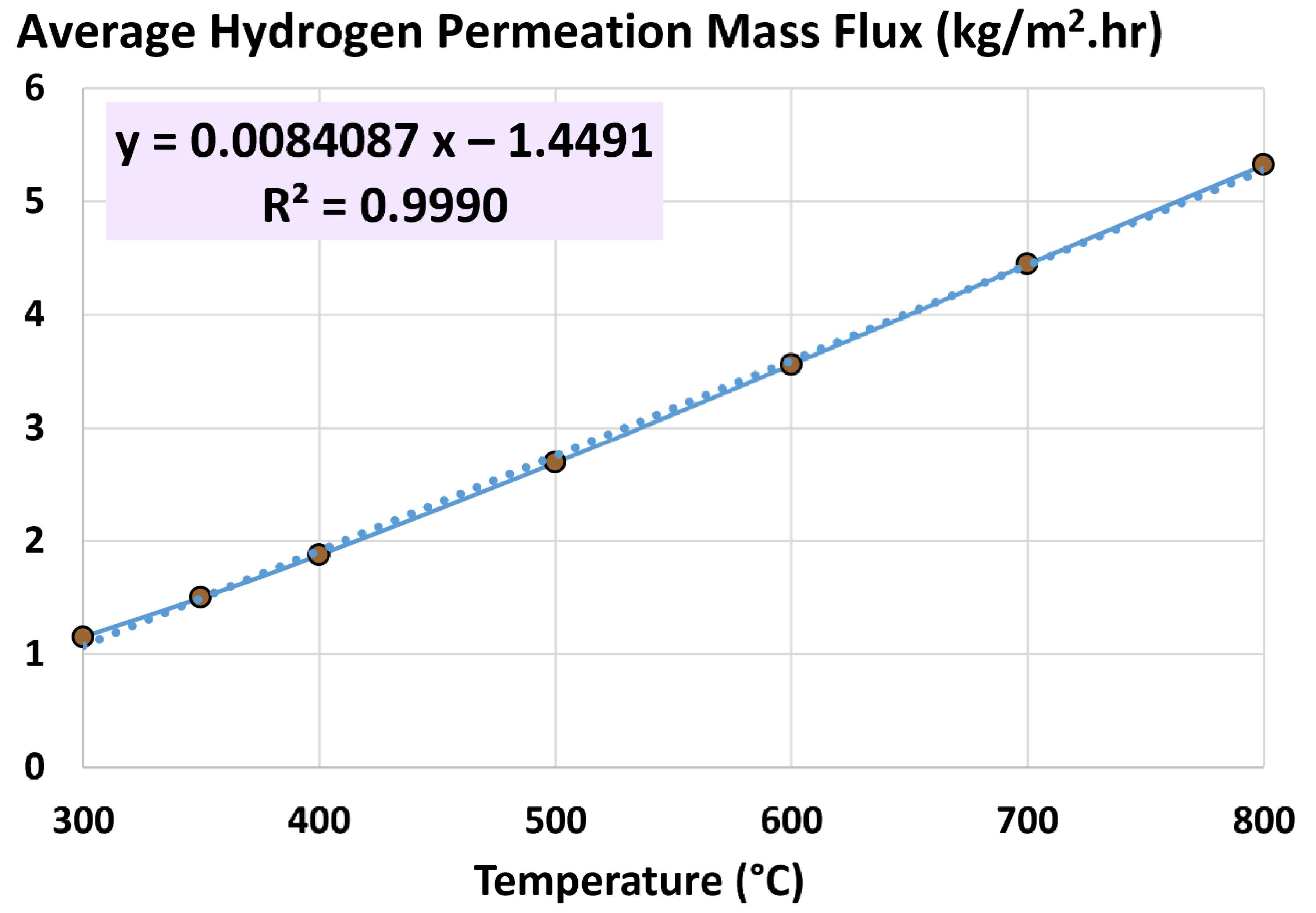

- Showing the impact of three different design variables on the hydrogen permeation performance, accompanied by good-fit regression models. This step helps in having a broad estimation of the advantage of manipulating each of these variable, which can be weighed against the expenses or practical difficulty in a realistic setting, thus helps in selecting optimum operational conditions.

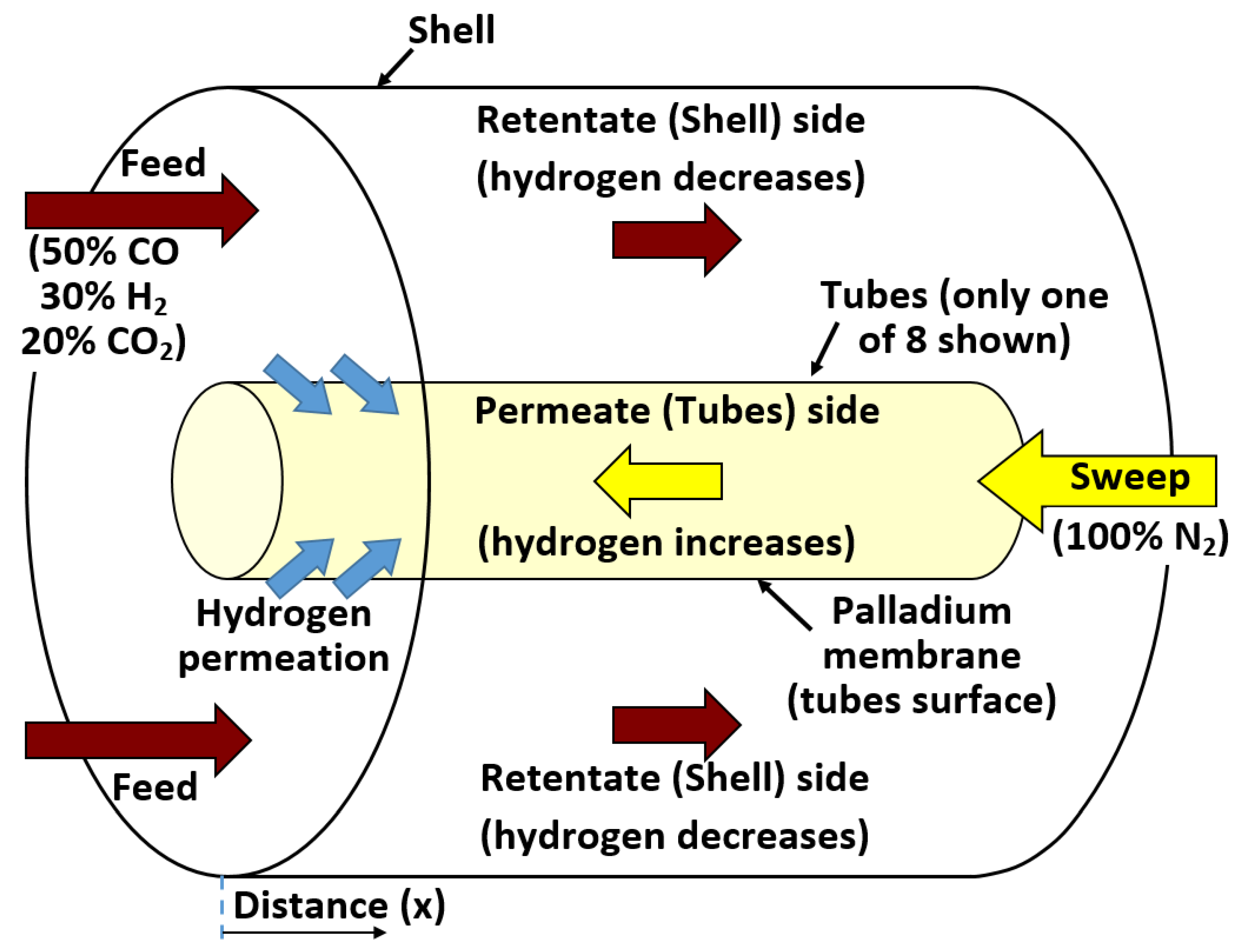

- Facilitating the validation of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models for membrane reactors, by making available necessary details about geometric, inlet, and mass transport conditions with results from a plug-flow reactor model. While the CFD results may not agree perfectly with the presented plug-flow reactor results (due the additional complexity in the CFD models), the results of the plug-flow reactor model can still guide a researcher or modeler while validating their CFD models through approximate matching of aggregate scalar quantities or distribution profiles. Although specific cross-section details are not necessary for the performing the plug-flow reactor simulations, an imagined geometric configuration in the form of a shell-and-tube reactor is proposed, making the model upgradable to three-dimensional simulation by the interested reader. The expected high slenderness ratio (length-to-width ratio), lack of turbulators, and symmetry in the model here are advantageous in terms in reducing the gap between the plug-flow reactor performed here, and a three-dimensional CFD model.

2. Research Method

- The temperature of the membrane reactor (while keeping the retentate-side pressure and the permeate-side pressure at reference values of a base case)

- The retentate-side pressure (while keeping the temperature and the permeate-side pressure at reference values of a base case)

- The permeate-side pressure (while keeping the temperature and the retentate-side pressure at reference values of a base case)

3. General Model Settings

3.1. Fixing Common Parameters

3.2. Underlying Geometry

3.3. Fixed Conditions

4. Modelling Hydrogen Permeation

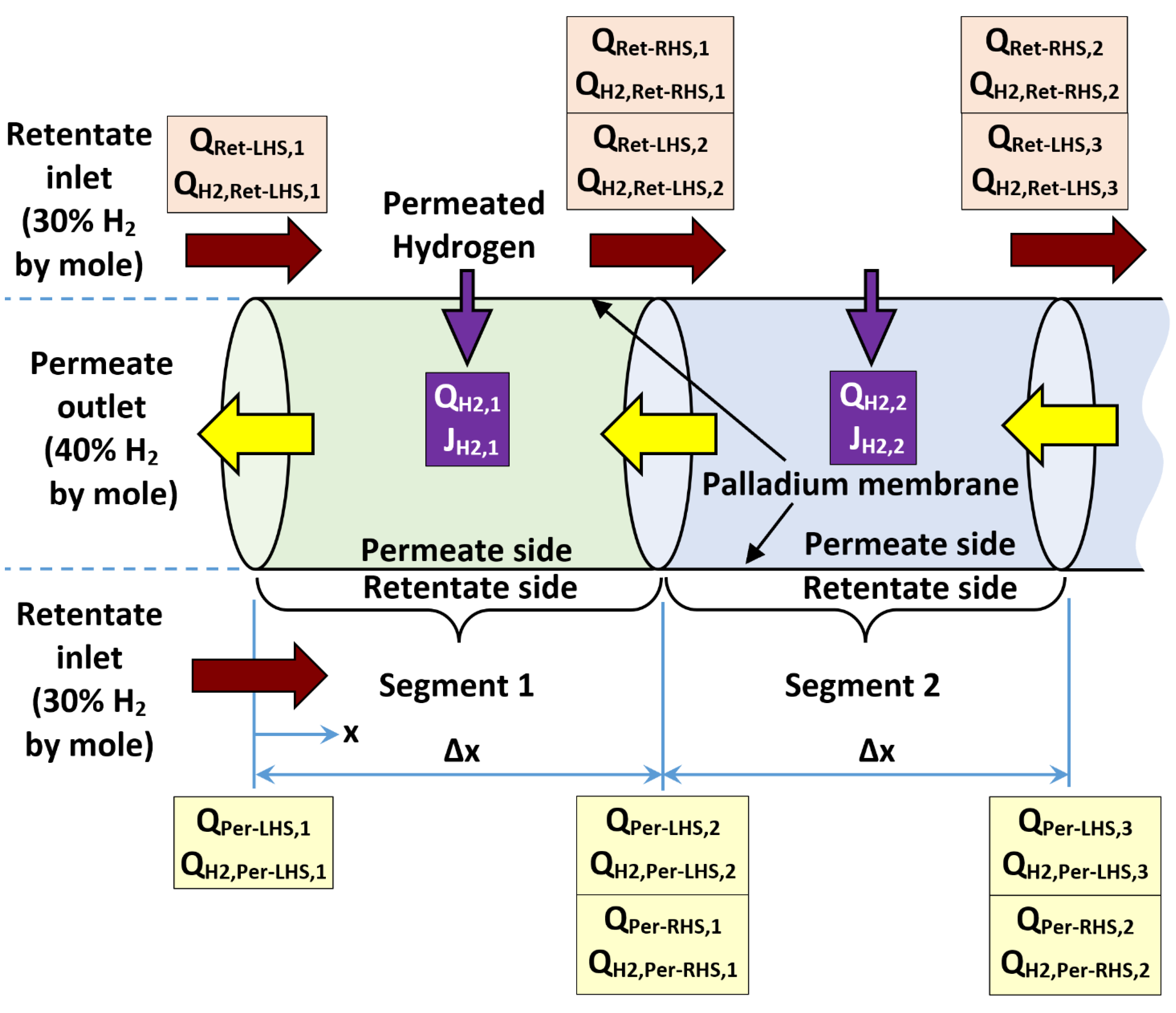

4.1. Segmental Plug-Flow Reactor

4.2. Modeling Algorithm

- a)

- Start with a known hydrogen mole fraction in the retentate at the LHS (XH2,Ret-LHS,i), standard volume flow rate of retentate at the LHS (QRet-LHS,i), hydrogen mole fraction of permeate at the LHS (XH2,Per-LHS,i), and standard volume flow rate of permeate at the LHS (QPer-LHS,i) of the segment (say segment number i).

- b)

- Compute (QH2,Per-LHS,i), which is the standard volume flow rate of the hydrogen content in the permeate stream at the LHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- c)

- Compute (ΔPH20.5)LHS,i, which is the difference in the partial pressures of hydrogen raised to the power of 0.5 (which is the driving force for hydrogen permeation through the palladium membrane) at the LHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- d)

- Compute (JH2,i), which is a predicted (first-iteration) segment-level molar flux of permeating hydrogen through the palladium membrane based on the conditions at LHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- e)

- Convert the LHS-based first-iteration molar flux (JH2,i) to a predicted (first-iteration) segment-level standard volume flow rate of permeating hydrogen (QH2,i) for the current segment being analyzed (say segment i).

- f)

- Compute (H2,Ret-RHS,i) and (H2,Per-RHS,i), which are predicted (first-iteration) mole fractions of hydrogen in the retentate stream and the permeate stream, respectively at the RHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- g)

- Compute (ΔPH20.5)RHS,i, which is the difference in the partial pressures of hydrogen raised to the power of 0.5 (as the driving force for hydrogen permeation) at the RHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- h)

- Compute (ΔPH20.5)i, which is the difference in the partial pressures of hydrogen raised to the power of 0.5 assigned to the current segment being analyzed (say segment i). It is taken as the arithmetic average of the LHS value and the RHS value, as follows:

- i)

- Compute (JH2,i), which is a corrected (second-iteration) segment-level molar flux of permeating hydrogen through the palladium membrane, which includes driving forces for permeation at both sides of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- j)

- Convert the corrected, segment-level molar flux (JH2,i) to a corresponding updated (refined) segment-level standard volume flow rate of permeating hydrogen (QH2,i) for the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- k)

- Compute (RH2,i), which is the hydrogen recovery due to the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- l)

- Optional: Compute (H2,i), which is the cumulative hydrogen recovery, due to all previous segments of the membrane reactor in addition to the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- m)

- Compute (QRet-RHS,i) and (QH2,Ret-RHS,i), which are the standard volume flow rate of the retentate stream and the hydrogen content in that retentate stream, respectively at the RHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- n)

- Compute (XH2,Ret-RHS,i), which is the corrected (second-iteration) mole fraction of hydrogen in the retentate stream at the RHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- o)

- Compute (QPer-RHS,i) and (QH2,Per-RHS,i), which are the standard volume flow rate of the permeate stream and the hydrogen content in that permeate stream, respectively at the RHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- p)

- Compute (XH2,Per-RHS,i), which is the corrected (second-iteration) mole fraction of hydrogen in the permeate stream at the RHS of the current segment being analyzed (say segment i), as follows:

- q)

- Set the obtained RHS conditions of current segment being analyzed (say segment i) as LHS conditions at the next adjacent segment to be analyzed (segment i+1), and repeat the computation procedure sequentially for all remaining segments until the last membrane segment (segment n).

- (ΔPH20.5)LHS,i

- H2,i

- H2,i

- H2,Ret-RHS,i and XH2,Per-RHS,i

- (ΔPH20.5)RHS,i

- (ΔPH20.5)i

- JH2,i

- QH2,i

- RH2,i

- Optional: ∙∙

- H2,i

- QRet-RHS,i and QH2,Ret-RHS,i

- XH2,Ret-RHS,i

- QPer-RHS,i and QH2,Per-RHS,i

- XH2,Per-RHS,i

- r)

- Compute (H2,n), which is the cumulative hydrogen recovery at the last segment. It is the overall hydrogen recovery by the entire membrane reactor, and it is obtained by simply adding the segment-level hydrogen recovery (RH2,i) for all the (n) segments of the membrane reactor. The total cumulative value is itself the target hydrogen recovery (β). Therefore

5. Assessing Hydrogen Permeation

5.1. Permeation Metrics

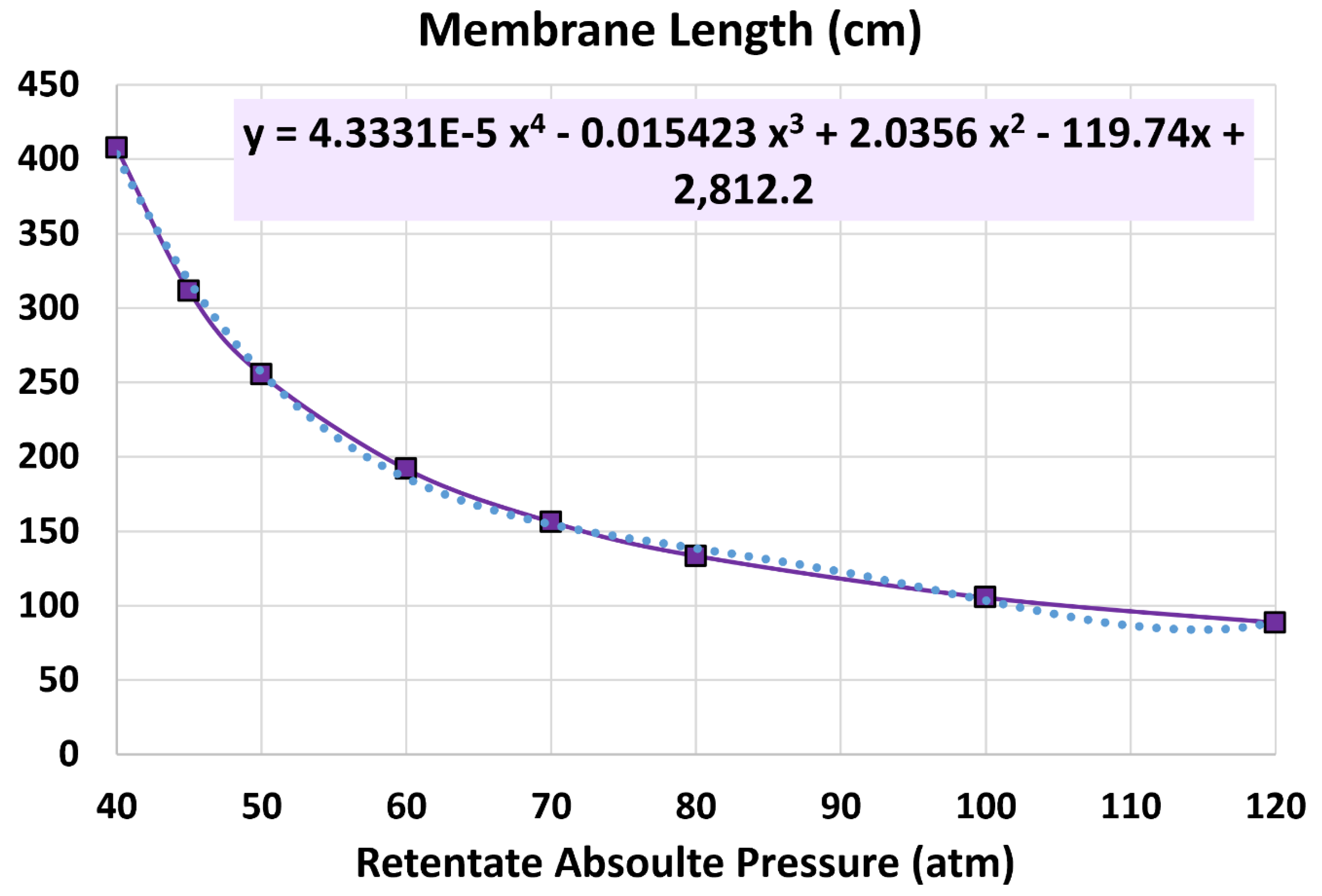

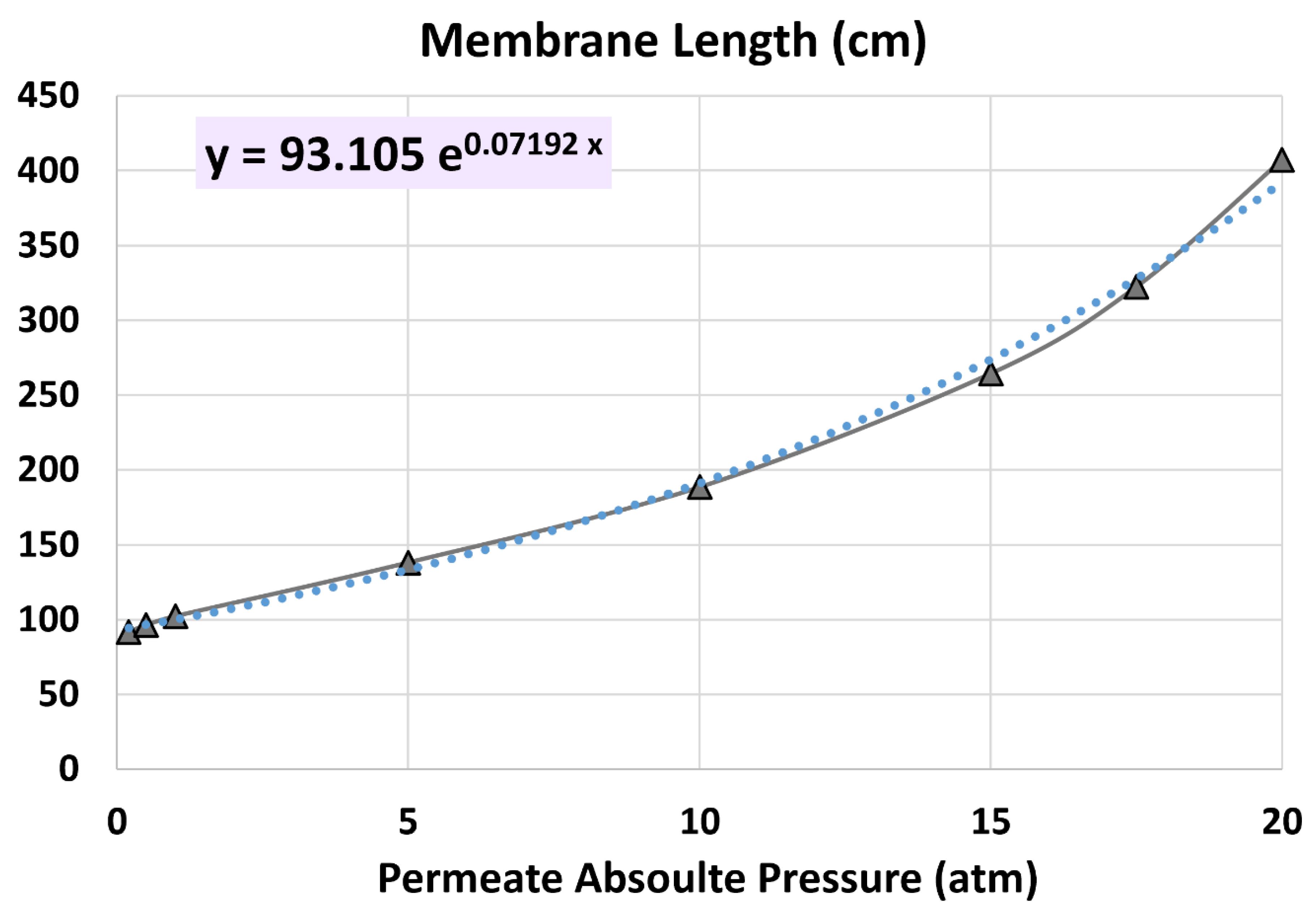

5.2. Membrane Length

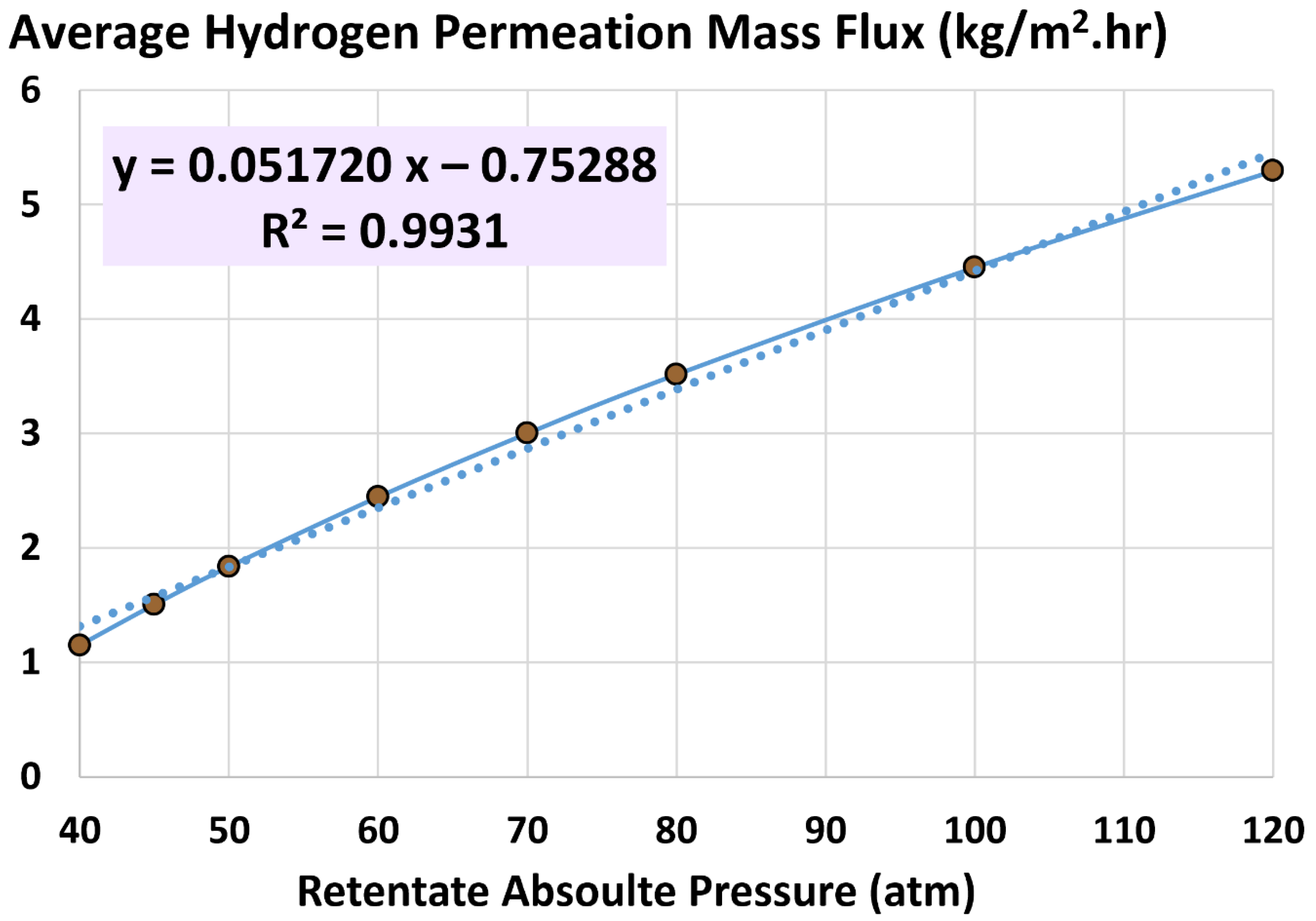

5.3. Average Hydrogen Permeation Mass Flux

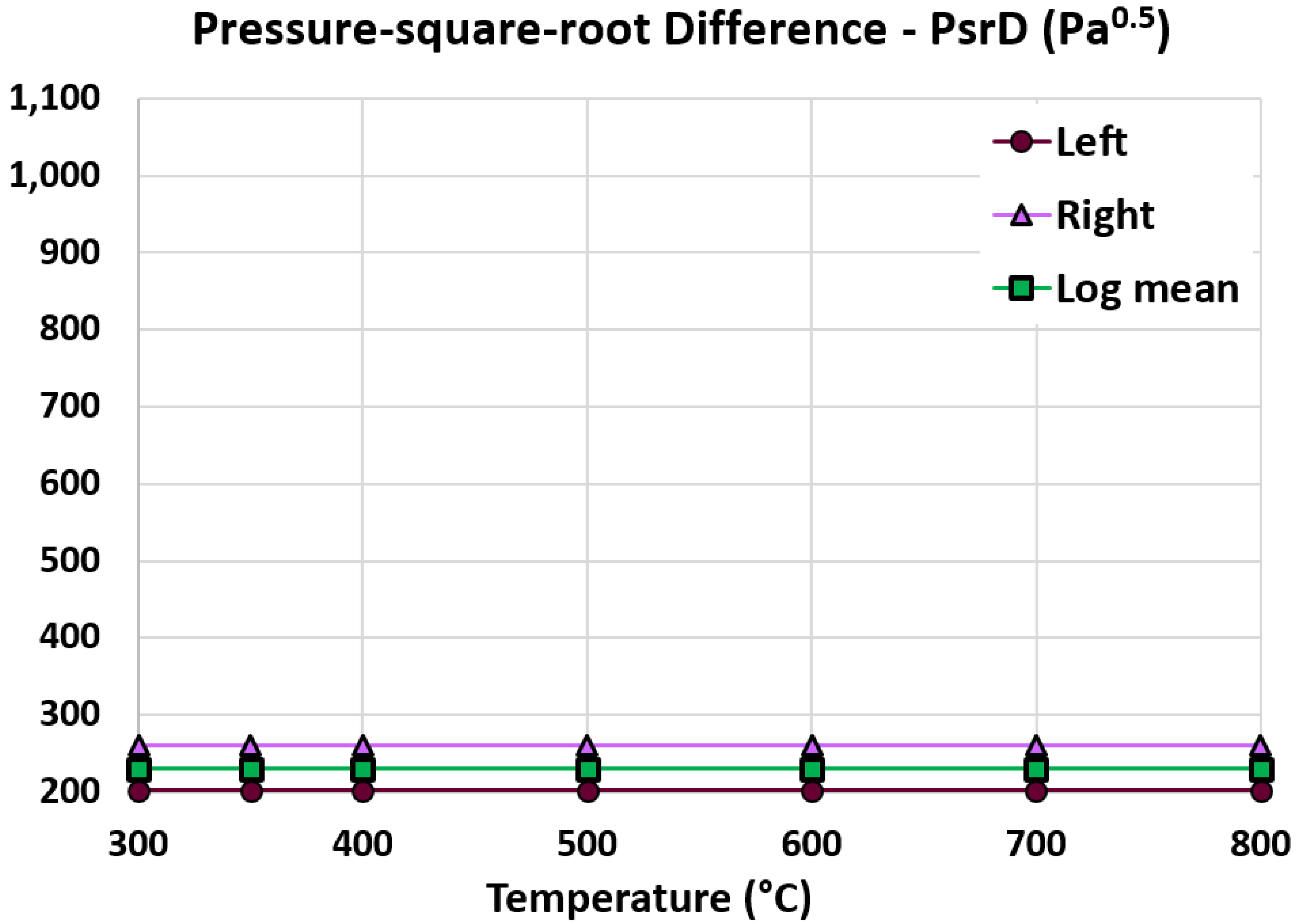

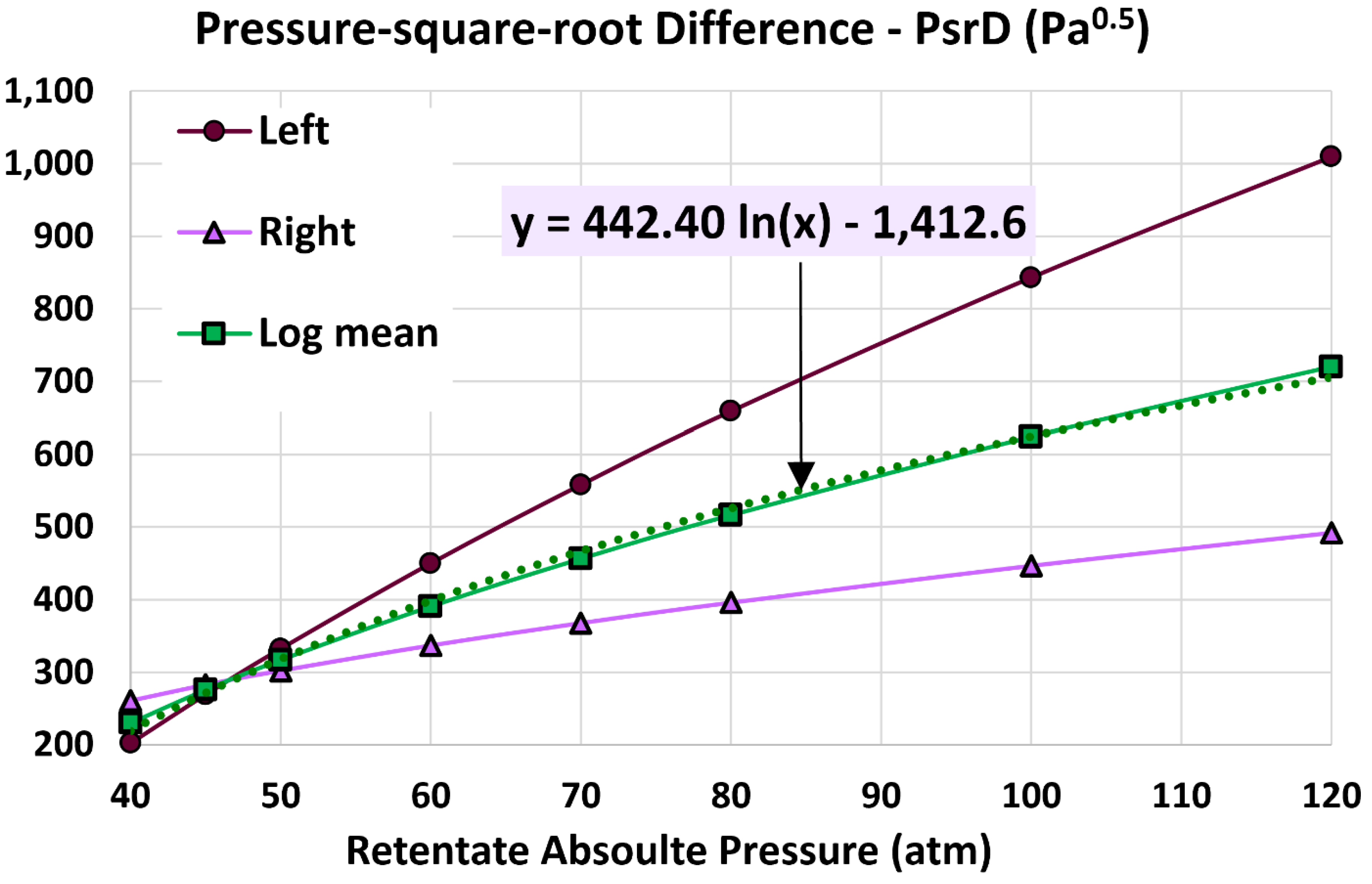

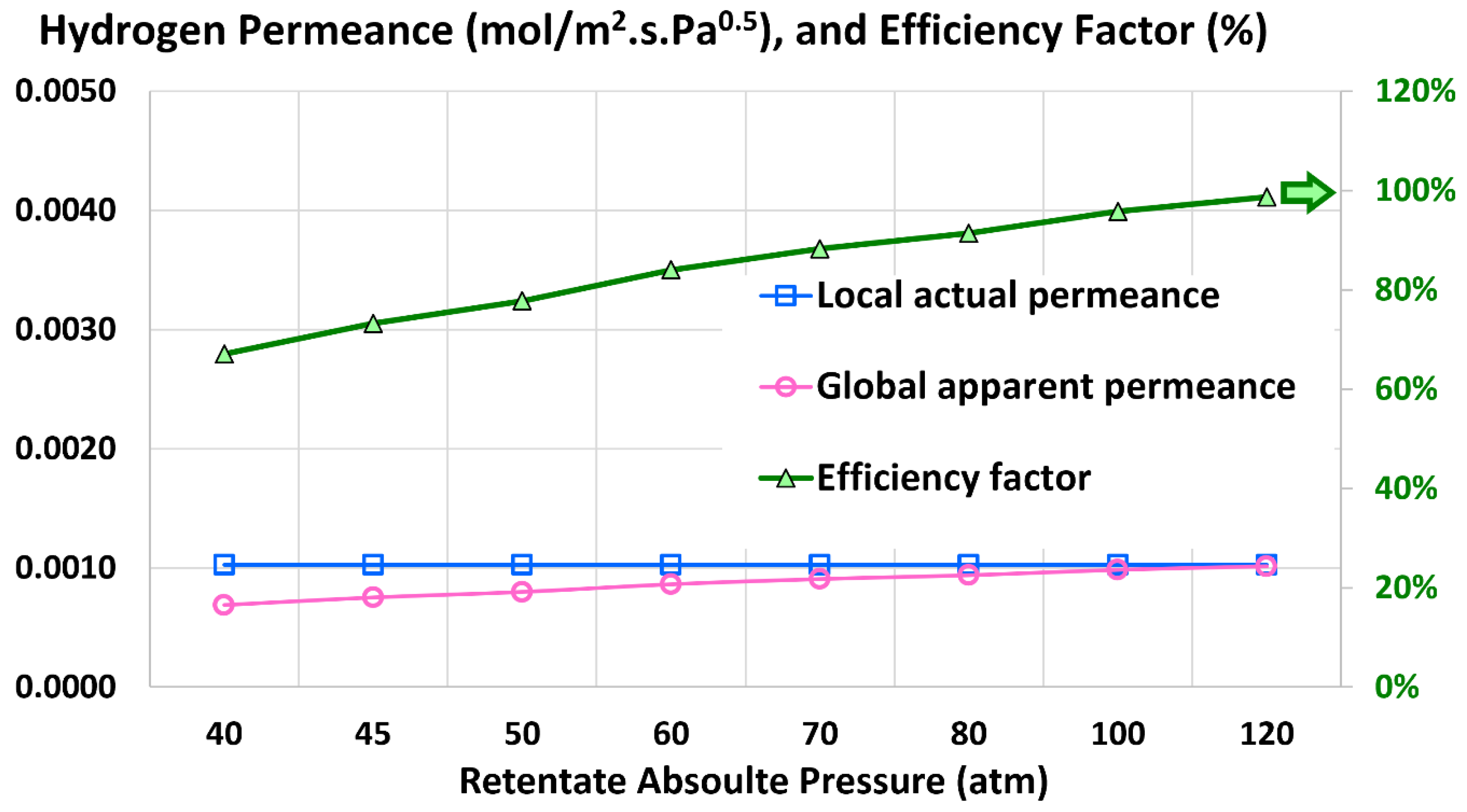

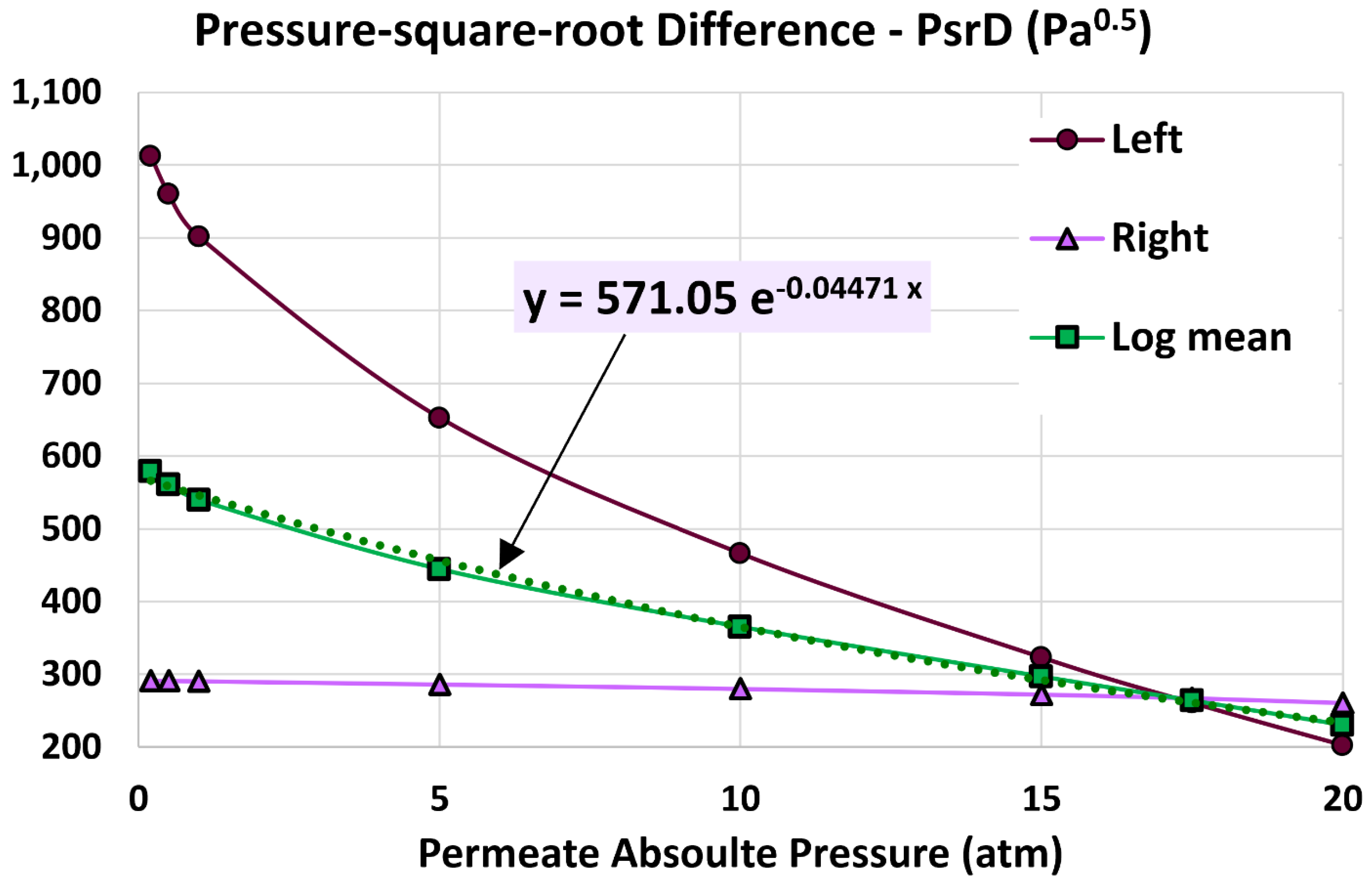

5.4. Log Mean Pressure-Square-Root Difference

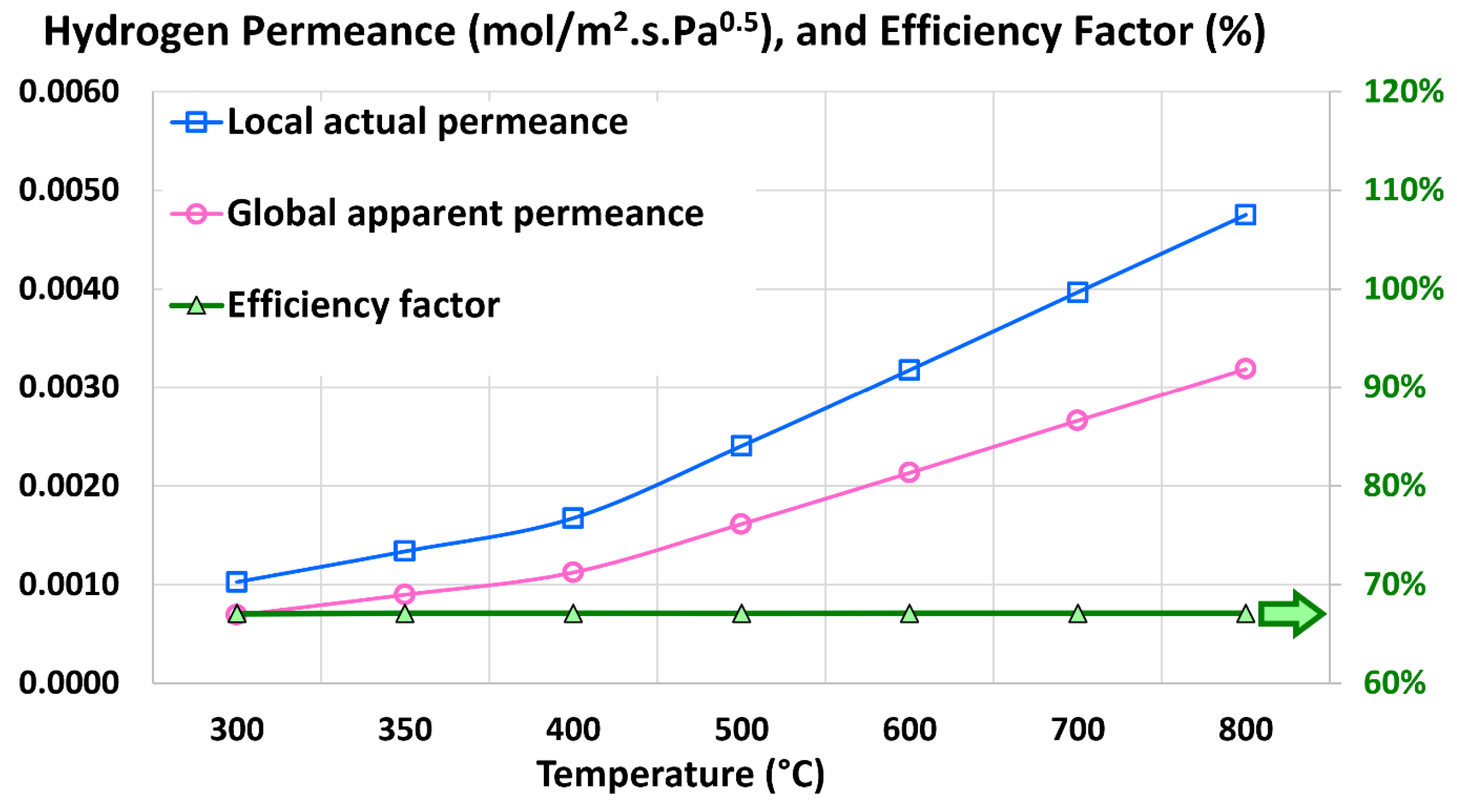

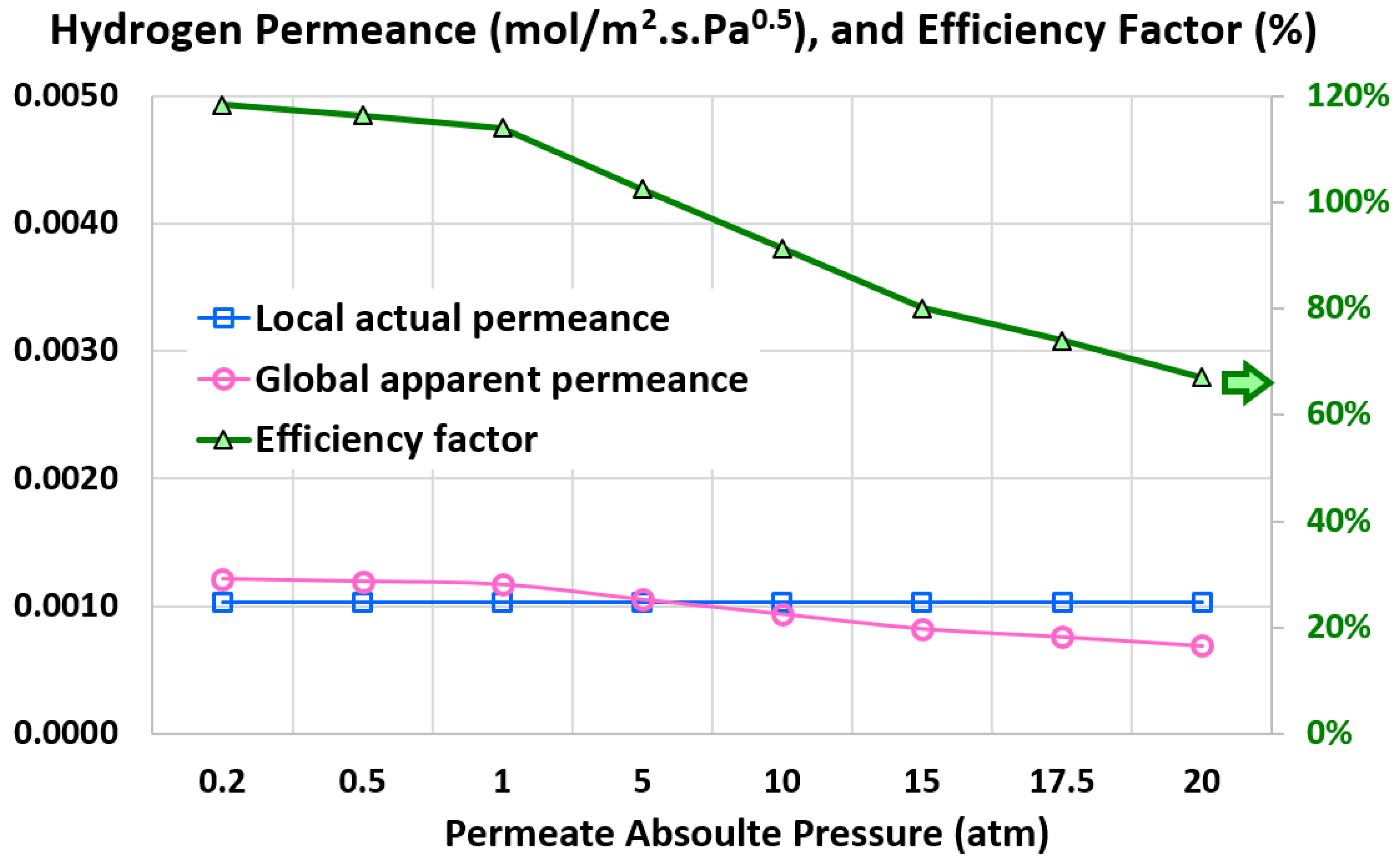

5.5. Global Apparent Permeance

5.6. Efficiency Factor

6. Results

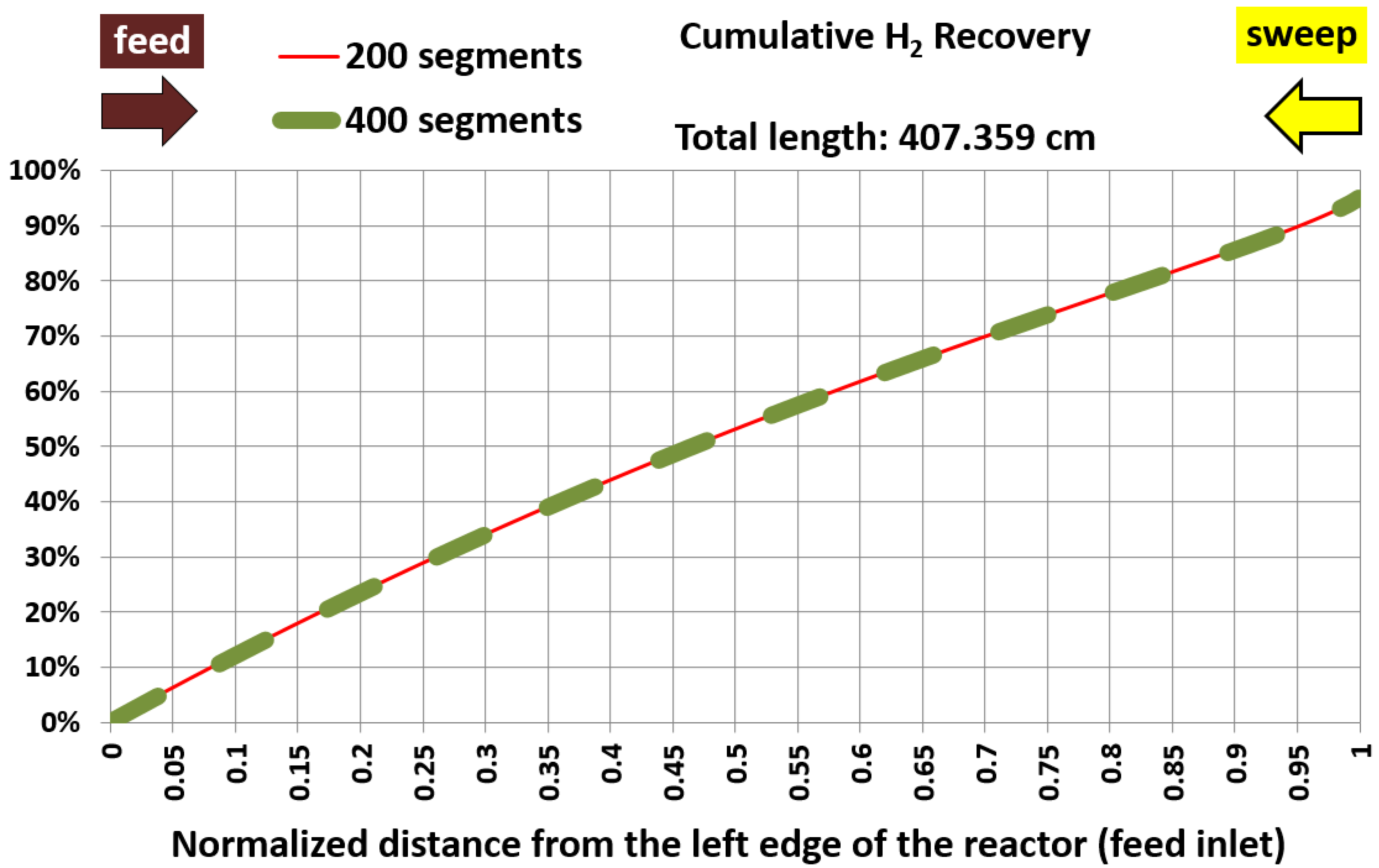

6.1. Base Case and Spatial Resolution Test

- Temperature (assumed uniform in the entire reactor)

- Retentate pressure (assumed uniform in the retentate stream)

- Permeate pressure (assumed uniform in the permeate stream)

6.2. Influence of Temperature

- 300 °C (base)

- 350 °C

- 400 °C

- 500 °C

- 600 °C

- 700 °C

- 800 °C

6.3. Influence of Retentate Pressure

- 40 atm (base)

- 45 atm

- 50 atm

- 60 atm

- 70 atm

- 80 atm

- 100 atm

- 120 atm

6.4. Influence of Permeate Pressure

- 20 atm (base)

- 17.5 atm

- 15 atm

- 10 atm

- 5 atm

- 1 atm

- 0.5 atm

- 0.2 atm

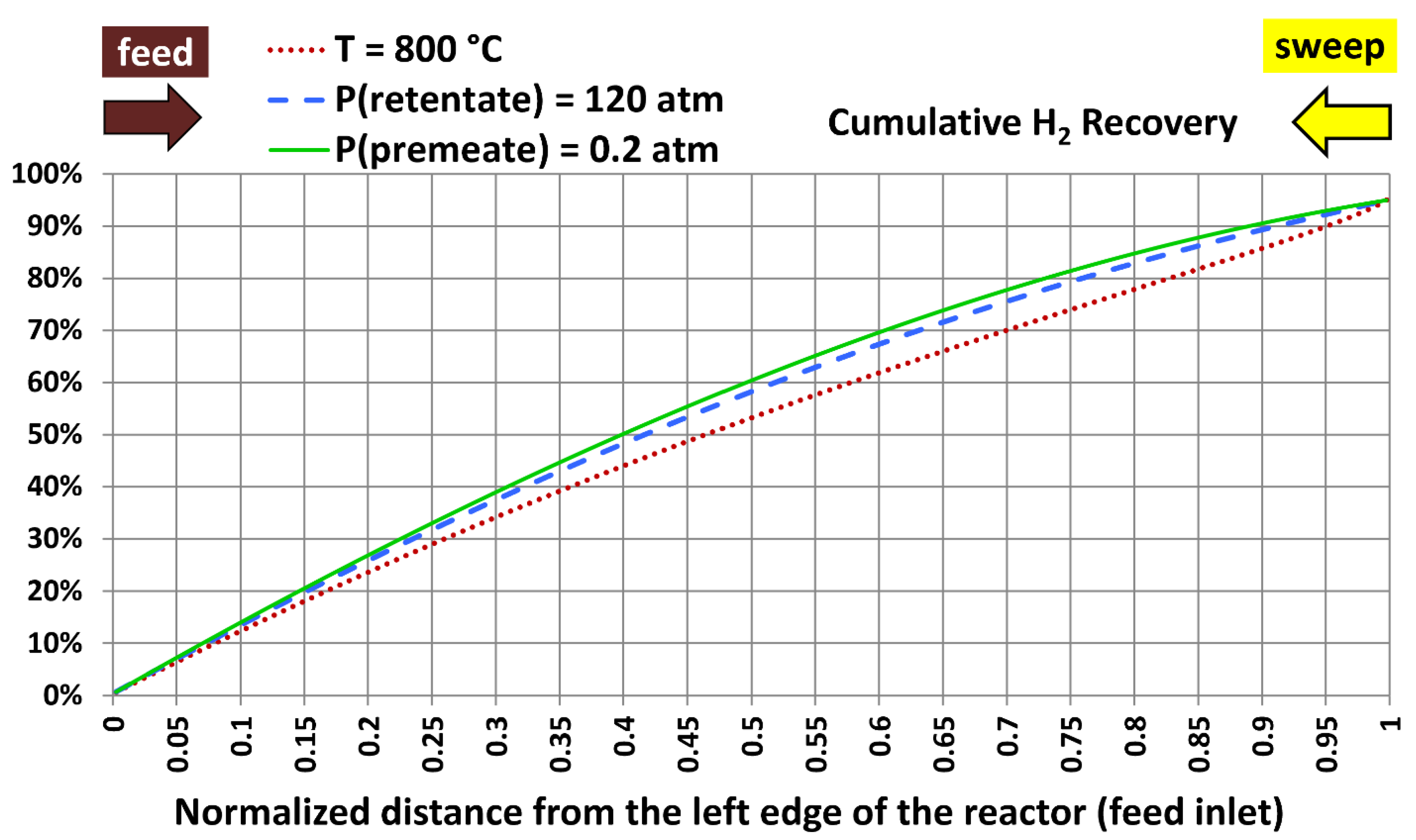

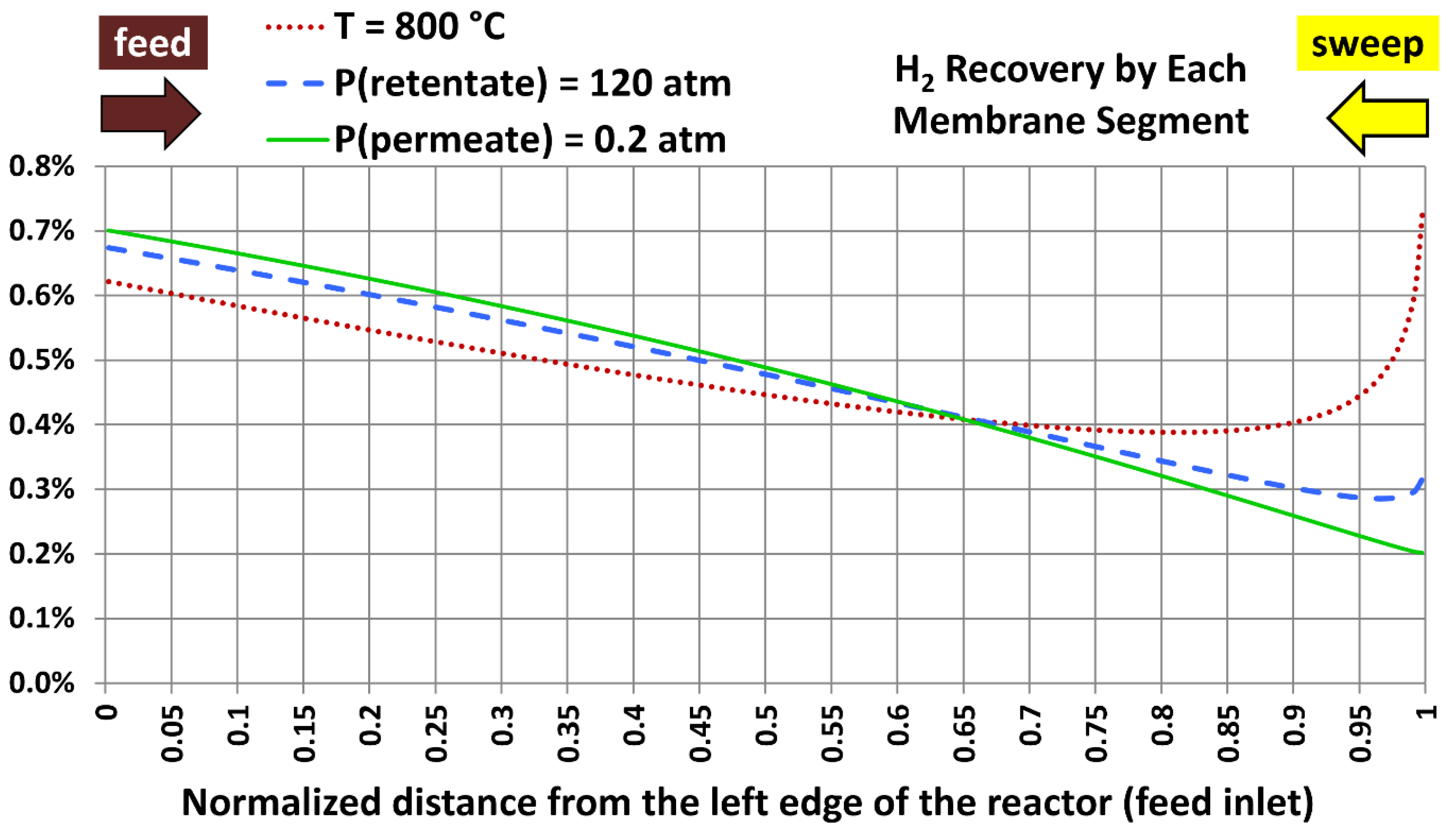

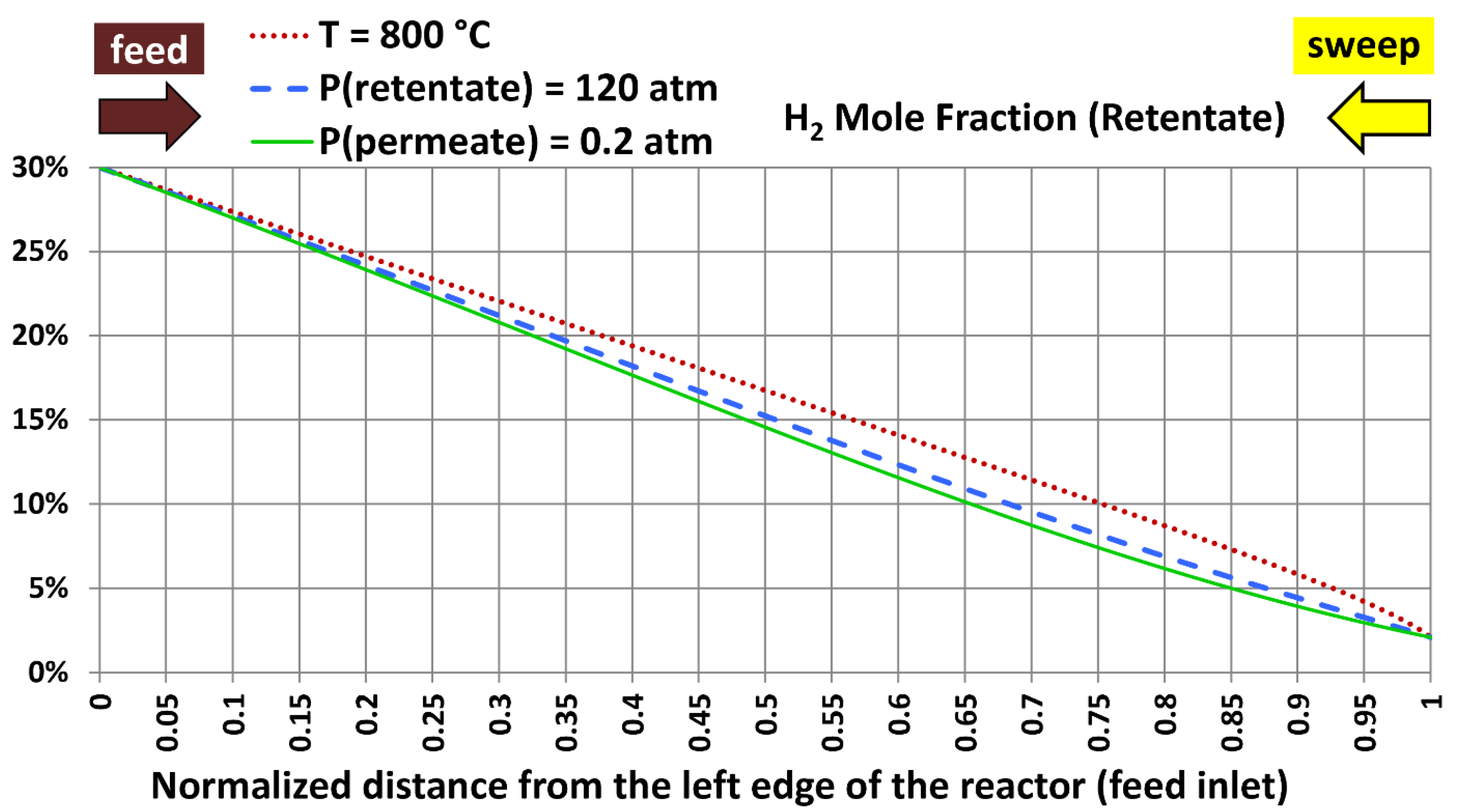

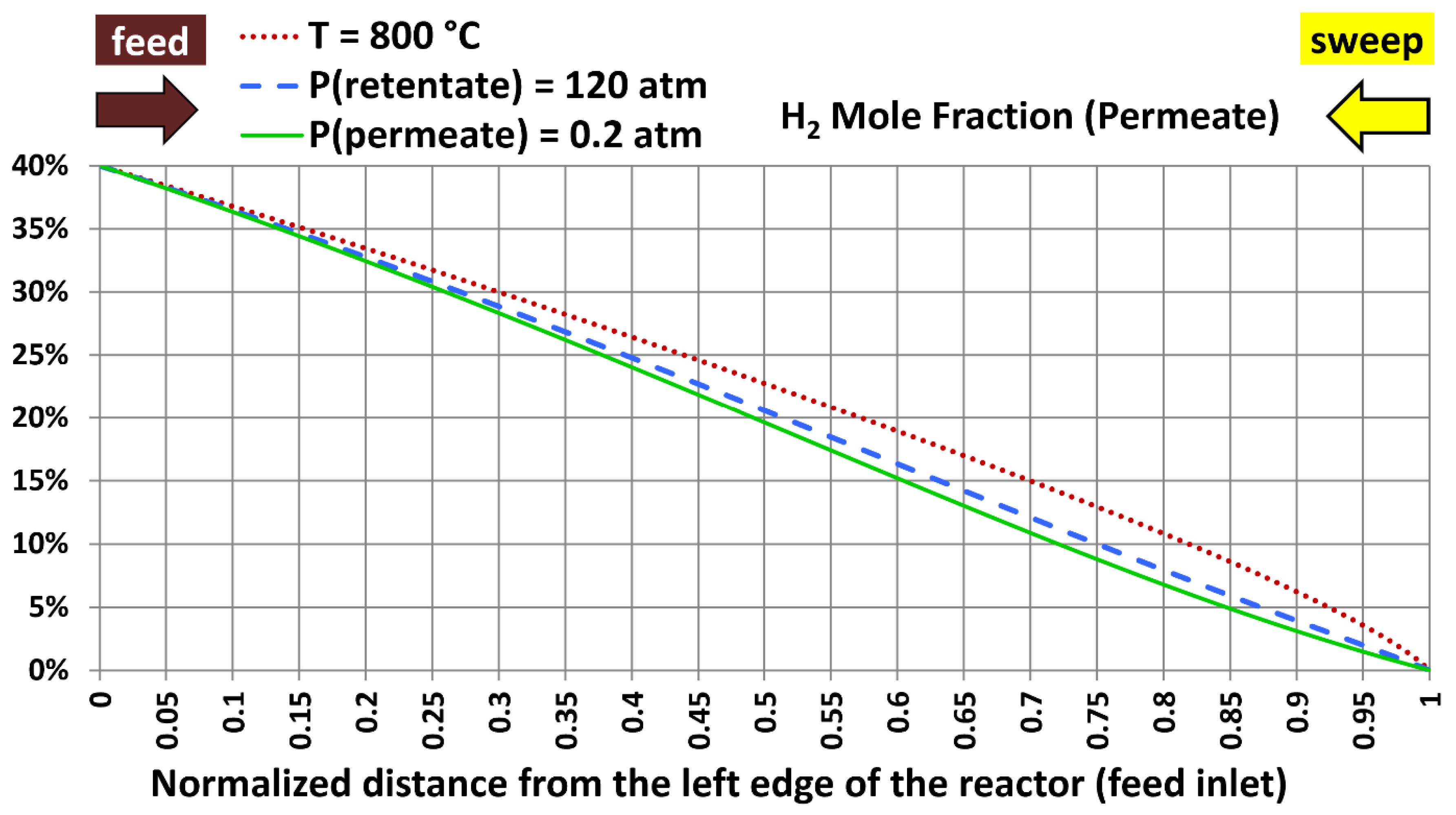

6.5. Profiles with Extreme Design Variables

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Couto, N. , Rouboa, A., Silva, V., Monteiro, E., Bouziane, K. Influence of the biomass gasification processes on the final composition of syngas. Energy Procedia 2013, 36, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafraz, M.M. , Safaei, M.R., Jafarian, M., Goodarzi, M., Arjomandi, M. High Quality Syngas Production with Supercritical Biomass Gasification Integrated with a Water–Gas Shift Reactor. Energies. 2019, 12, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NETL [National Energy Technology Laboratory of the United States Department of Energy]. (no date). Reactions & Transformations. https://netl.doe.gov/research/coal/energy-systems/gasification/gasifipedia/reaction-transformations [Accessed May 5, 2022].

- Poudel, J. , Choi, J.H., Oh, S.C. Process Design Characteristics of Syngas (CO/H2) Separation Using Composite Membrane. Sustainability 2019, 11, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.N. , and Aarthi, V. From Biomass to Syngas, Fuels and Chemicals – A Review. AIP Conference Proceedings 2020, 2225, 070007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmadge, M. , Biddy, M., Dutta, A., Jones, S., Meyer, A. (2013). Syngas Upgrading to Hydrocarbon Fuels Technology Pathway [Technical Report by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory “NREL” and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory “PNNL” of the United States Department of Energy]. Available at: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy13osti/58052.pdf.

- Matar, S. , Mirbach, M.J., Tayim, H.A. (1989). Production and Uses of Synthesis Gas. In: Catalysis in Petrochemical Processes. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, B. , Camporeale, S.M., Torresi, M. A Gas-Steam Combined Cycle Powered by Syngas Derived from Biomass. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 19, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stork. (2022). Syngas Fired Steam Boiler. https://www.stork.com/en/client-cases/syngas-fired-steam-boiler [Accessed May 6, 2022].

- Marco, R. , and Carlo, P. (2015). "9. Use of bio-sourced syngas," in Biorefineries: An Introduction, ed. M. Aresta, A. Dibenedetto, F. Dumeignil (Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter), 219–234. [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y. , Wang, K., Zhu, W., Liu, Z. Realizing high conversion of syngas to gasoline-range liquid hydrocarbons on a dual-bed-mode catalyst. Chem Catal. 2021, 1, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felseghi, R.-A. , Carcadea, E., Raboaca, M.S., TRUFIN, C.N., Filote, C. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Technology for the Sustainable Future of Stationary Applications. Energies 2019, 12, 4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiat, I. , and Al-Ansari, T. A review of carbon capture and utilisation as a CO2 abatement opportunity within the EWF nexus. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 45, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madejski, P. , Chmiel, K., Subramanian, N., Kuś, T. Methods and Techniques for CO2 Capture: Review of Potential Solutions and Applications in Modern Energy Technologies. Energies 2022, 15, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinca, C. , Slavu, N., Cormoş, C.-C., Badea, A. CO2 capture from syngas generated by a biomass gasification power plant with chemical absorption process. Energy 2018, 149, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, E. , Zhang, Y., Liu, D. Current situation of carbon dioxide capture, storage, and enhanced oil recovery in the oil and gas industry. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 97, 1048–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OFECM [Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management at the United States Department of Energy]. (no date). Pre-Combustion Carbon Capture Research. https://www.energy.gov/fecm/science-innovation/carbon-capture-and-storage-research/carbon-capture-rd/pre-combustion-carbon[Accessed May 6, 2022].

- Iulianelli, A. , Ribeirinha, P., Basile, A. Methanol steam reforming for hydrogen generation via conventional and membrane reactors: A review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2014, 29, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piemonte, V. , Di Paola, L., De Falco, M., Iulianelli, A., Basile, A. "11 - Hydrogen production using inorganic membrane reactors," in Advances in Hydrogen Production, Storage and Distribution, ed. A. Basile and A. Iulianelli (Woodhead Publishing), 2014, 283–316. [CrossRef]

- Peters, T. , and Caravella, A. Pd-Based Membranes: Overview and Perspectives. Membranes 2019, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermaak, L. , Neomagus, H.W.J.P., Bessarabov, D.G. Hydrogen Separation and Purification from Various Gas Mixtures by Means of Electrochemical Membrane Technology in the Temperature Range 100–160 °C. Membranes 2021, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alique, D. , Martinez-Diaz, D., Sanz, R., Calles, J.A. Review of Supported Pd-Based Membranes Preparation by Electroless Plating for Ultra-Pure Hydrogen Production. Membranes 2018, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.-K. , Lee, K.-Y., Park, J.-S. Hydrogen Purification from Compact Palladium Membrane Module Using a Low Temperature Diffusion Bonding Technology. Membranes 2020, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, G. , Steele, D., O'Brien, K., Callahan, R., Berchtold, K., Figueroa, J. Simulation of a Process to Capture CO2 From IGCC Syngas Using a High Temperature PBI Membrane. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 4079–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berstad, D. , Nekså, P., Gjøvåg, G.A. Low-temperature syngas separation and CO2 capture for enhanced efficiency of IGCC power plants. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GE Power Systems. (no date). GE IGCC Technology and Experience with Advanced Gas Turbines [Online resource]. Available at: https://www.ge.com/content/dam/gepower-new/global/en_US/downloads/gas-new-site/resources/reference/ger-4207-ge-igcc-technology-experience-advanced-gas-turbines.pdf (Accessed May 6, 2022).

- Wang, T. "1 - An overview of IGCC systems," in Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) Technologies, ed. T. Wang and G. Stiegel (Woodhead Publishing), 2017, 1-80. [CrossRef]

- Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. Energy Systems. (no date). IGCC Integrated coal Gasification Combined Cycle Power Plants [Catalogue document]. Available at: https://power.mhi.com/catalogue/pdf/igcc.pdf (Accessed May 6, 2022).

- Barbieri, G. (2015). "Sweep Gas in a Membrane Reactor," in: Encyclopedia of Membranes, ed. E. Drioli (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. , Polfus, J.M., Xing, W., Denonville, C., Fontaine, M.-L., Bredesen, R. Factors Limiting the Apparent Hydrogen Flux in Asymmetric Tubular Cercer Membranes Based on La27W3.5Mo1.5O55.5−δ and La0.87Sr0.13CrO3−δ. Membranes 2019, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chein, R.Y. , Chen, Y.C., Chung, J.N. Sweep gas flow effect on membrane reactor performance for hydrogen production from high-temperature water-gas shift reaction. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 475, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, U. , Dorris, S.E., Emerson, J.E., Lee, T.H., Lu, Y., Park, C.Y., Picciolo, J.J. (2011). Hydrogen Separation Membranes [Annual Report by the Argonne National Laboratory “ANL” of the United States Department of Energy for FY 2010]. Available at: https://publications.anl.gov/anlpubs/2011/03/69523.pdf.

- Chiesa, P. , Romano, M.C., Kreutz, T.G. "10 - Use of membranes in systems for electric energy and hydrogen production from fossil fuels," in Handbook of Membrane Reactors, Reactor Types and Industrial Applications, ed. A. Basile (Woodhead Publishing), 2013, 416–455. [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, A. , Caravella, A., Drioli, E., Barbieri, G. (2017). "CHAPTER 1: Membrane Reactors for Hydrogen Production," in Membrane Engineering for the Treatment of Gases: Volume 2: Gas-separation Issues Combined with Membrane Reactors: Edition 2, ed. E. Drioli, G. Barbieri, A. Brunetti (The Royal Society of Chemistry), 1–29. [CrossRef]

- GTI [Gas Technology Institute] (2007). Direct Hydrogen Production from Biomass Gasifier Using Hydrogen-Selective Membrane [Final Report, prepared for Xcel Energy]. Available at: https://www.xcelenergy.com/staticfiles/xe/Corporate/RDF-DirectHydrogenProduction-Report%5B1%5D.pdf.

- Kinouchi, K. , Katoh, M., Horikawa, T., Yoshikawa, T., Wada, M. Hydrogen Permeability of Palladium Membrane for Steam-reforming of Bio-Ethanol Using the Membrane Reactor. Int. J. Mod. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 6, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermex. (2022). Why counter flow heat exchangers are more efficient. http://www.thermex.co.uk/news/blog/605-why-counter-flow-heat-exchangers-are-more-efficient. (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Enerquip. (2022). What’s the difference between parallel flow, counter flow and crossflow heat exchangers? https://www.enerquip.com/whats-the-difference-between-parallel-flow-counter-flow-and-crossflow-heat-exchangers. (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- NIST [National Institute of Standards and Technology]. (2021a). NIST Chemistry WebBook - Hydrogen. https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?Name=h2&Units=SI. (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- NIST [National Institute of Standards and Technology]. (2021b). NIST Chemistry WebBook - Carbon monoxide. https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?Name=CO&Units=SI. (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- NIST [National Institute of Standards and Technology]. (2021c). NIST Chemistry WebBook - Carbon dioxide. https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C124389&Units=SI. (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Kuo, K.K. (2005). Principles of Combustion, 2nd ed. New Jersey, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Poinsot, T. , and Veynante, D. (2005). Theoretical and Numerical Combustion, 2nd ed. USA: R.T. Edwards, Inc.

- IUPAC [International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry]. (1997). Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Compiled by A.D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. Online version (2019-) made by S.J. Chalk. [CrossRef]

- NIST [National Institute of Standards and Technology]. (2018). CODATA [Committee on Data for Science and Technology] Value: molar gas constant. https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?r|search_for=gas. (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- NIST [National Institute of Standards and Technology]. (2021d). NIST Chemistry WebBook - Nitrogen. https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?Name=n2&Units=SI. (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Tuckerman, M.E. (2020). Lecture 25: Plug flow reactors and comparison to continuously stirred tank reactors. https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/New_York_University/CHEM-UA_652%3A_Thermodynamics_and_Kinetics/Lecture_25%3A_Plug_flow_reactors_and_comparison_to_continuously_stirred_tank_reactors [Accessed May 9, 2022].

- AIChE [American Institute of Chemical Engineers] (no date). Plug Flow Reactor (PFR). https://www.aiche.org/ccps/resources/glossary/process-safety-glossary/plug-flow-reactor-pfr [Accessed , 2022]. 9 May.

- Campo, M. , Tanaka, A., Mendes, A., Sousa, J.M. "3 - Characterization of membranes for energy and environmental applications," in Advanced Membrane Science and Technology for Sustainable Energy and Environmental Applications, ed. A. Basile and S.P. Nunes (Woodhead Publishing), 2011, 56–89. [CrossRef]

- Alraeesi, A. , and Gardner, T. Assessment of Sieverts Law Assumptions and ‘n’ Values in Palladium Membranes: Experimental and Theoretical Analyses. Membranes 2021, 11, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koffler, S.A. , Hudson, J.B., Ansell, G.S. Hydrogen permeation through alpha-palladium. Trans. Metall. Soc. AIME 1969, 245, 1735–1740. [Google Scholar]

- Morreale, B.D. , Ciocco, M.V., Enick, R.M., Morsi, B.I., Howard, B.H., Cugini, A.V., Rothenberger, K.S. The permeability of hydrogen in bulk palladium at elevated temperatures and pressures. J. Membr. Sci. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Performance Analysis of Shell-and-Tube Dehydrogenation Module. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M. , Lee, K., Van Campen, D.G., Liguori, S., Toney, M.F., Wilcox, J. Hydrogen Purification in Palladium-Based Membranes: An Operando X-ray Diffraction Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordio, M. , Wassie, S.A., Annaland, M.V.S., Tanaka, D.A.P., Sole, J.L.V., Gallucci, F. Techno-economic evaluation on a hybrid technology for low hydrogen concentration separation and purification from natural gas grid. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 23417–23435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft corporation. (2022). Use Goal Seek to find the result you want by adjusting an input value. https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/use-goal-seek-to-find-the-result-you-want-by-adjusting-an-input-value-320cb99e-f4a4-417f-b1c3-4f369d6e66c7. (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Bandyopadhyay, S. All forms of energy are equal, but some forms of energy are more equal than others. Clean Techn. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 2775–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.C.D. , Talmadge, M., Dutta, A., Hensley, J., Schaidle, J., Biddy, M., Humbird, D., Snowden-Swan, L.J., Ross, J., Sexton, D., Yap, R., Lukas, J. (2015). Process Design and Economics for the Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Hydrocarbons via Indirect Liquefaction Thermochemical Research Pathway to High-Octane Gasoline Blendstock Through Methanol/Dimethyl Ether Intermediates [Technical Report prepared for the United States Department of Energy - Bioenergy Technologies Office]. Available at: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy15osti/62402.pdf.

- Leonzio, G. Methanol Synthesis: Optimal Solution for a Better Efficiency of the Process. Processes 2018, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, A. , and Italiano, C. (2020). "Chapter 4 - Fuel and hydrogen related problems for conventional steam reforming of natural gas," in Current Trends and Future Developments in (Bio-) Membranes: Membranes in Environmental Applications, ed. A. Figoli, Y. Li, A. Basile (Elsevier), 71–89. [CrossRef]

- Utamura, M. , Nikitin, K., Kato, Y. A generalised mean temperature difference method for thermal design of heat exchangers. Int. J. Nucl. Energy Sci. Technol. 2008, 4, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhard IV, J.H. , and Lienhard V, J. (2019). A Heat Transfer Textbook, 5th ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Heumann, C. , Schomaker, M., Shalabh (2016). Introduction to Statistics and Data Analysis With Exercises, Solutions and Applications in R, Switzerland: Springer.

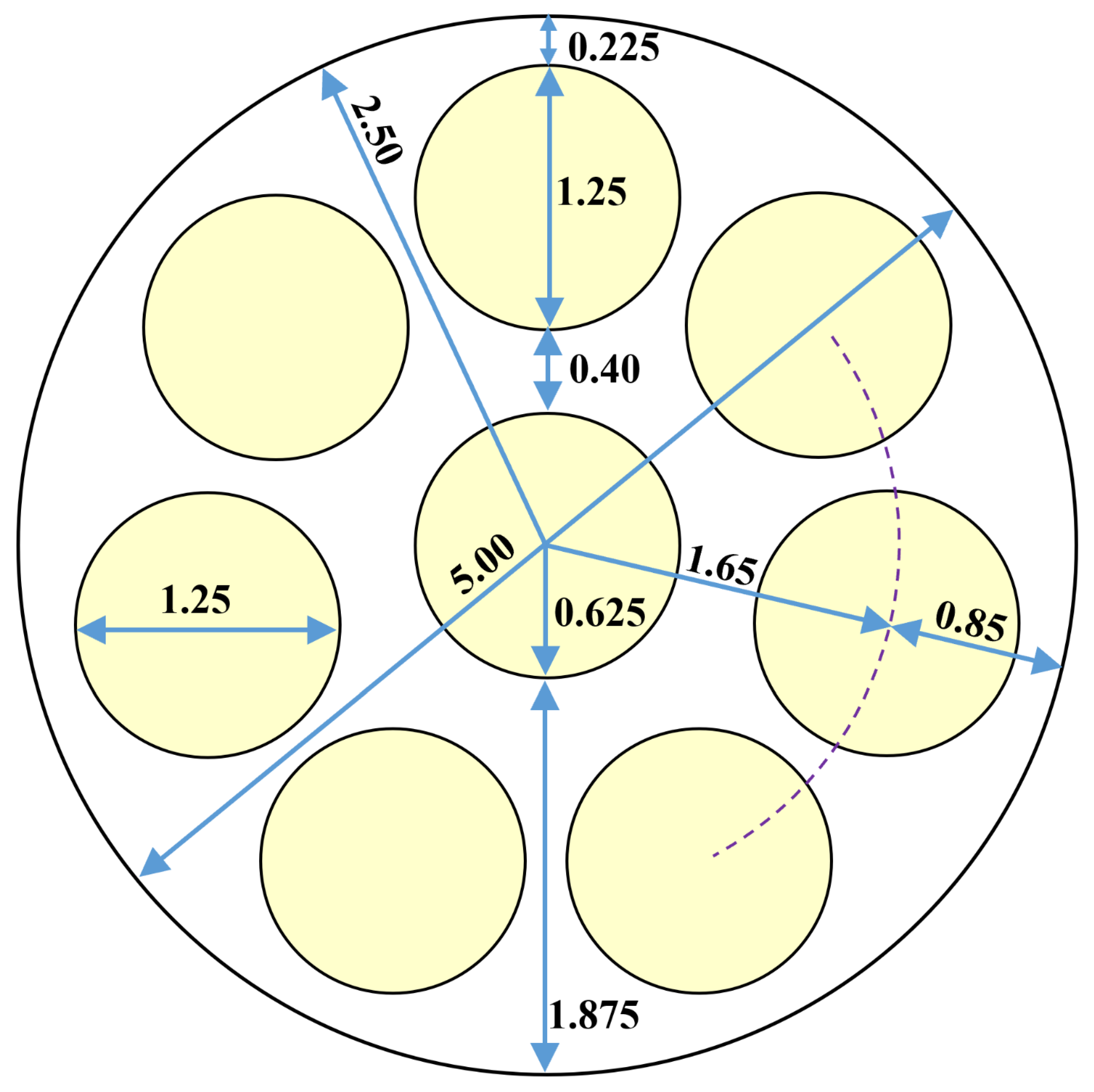

| Geometric feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Shell diameter | 5.000 cm (1.969 in) |

| Tube diameter | 1.250 cm (0.4921 in) |

| Number of tubes | 8 |

| Shell cross-section area (excluding tubes) | 9.817 cm2 (1.522 in2) |

| Tubes cross-section area (all 8 tubes) | 9.817 cm2 (1.522 in2) |

| Shell : Tube area ratio | 1 : 1 |

| Tube cross-section area (single tube) | 1.227 cm2 (0.1902 in2) |

| Condition | Value |

|---|---|

| Inlet mole fraction, H2 | 30% |

| Inlet mole fraction, CO | 50% |

| Inlet mole fraction, CO2 | 20% |

| Molecular weight, H2 | 2.01588 kg/kmol (NIST, 2021a) |

| Molecular weight, CO | 28.0101 kg/kmol (NIST, 2021b) |

| Molecular weight, CO2 | 44.0095 kg/kmol (NIST, 2021c) |

| Molecular weight, mixture | 23.412 kg/kmol |

| Inlet mass fraction, H2 | 0.025832 |

| Inlet mass fraction, CO | 0.598207 |

| Inlet mass fraction, CO2 | 0.375961 |

| Mass flow rate | 60 kg/hr (132.28 lbm/hr) |

| Standard volume flow rate | 970,068 sccm (standard cubic centimeters per minute) |

| Target hydrogen recovery | 95% (by mass, by mole, or by standard volume - identical) |

| Condition | Value |

|---|---|

| Inlet gas | 100% N2 |

| Molecular weight, N2 | 28.0134 kg/kmol (NIST, 2021d) |

| Mass flow rate | 30.692 kg/hr (67.664 lbm/hr) |

| Standard volume flow rate | 414,704 sccm (standard cubic centimeters per minute) |

| Target outlet mole fraction of H2 | 40% |

| Fluid property | Value |

|---|---|

| Temperature | 300 °C (572.00 °F) |

| Absolute retentate pressure | 40.0 atm (587.84 psia) |

| Absolute permeate pressure | 20.0 atm (293.92 psia) |

| Result | Value | Absolute percentage change | |

| n = 200 segments | n = 400 segments | ||

| Membrane length (cm) | 407.359 | 407.359 | 0% (identical) |

| Average hydrogen permeation mass flux (kg/m2.hr) | 1.151 | 1.150 | 0.01% |

| Pressure-square-root difference at the left end (Pa0.5) | 202.345 | 202.345 | 0% (identical) |

| Pressure-square-root difference at the right end (Pa0.5) | 260.655 | 268.896 | 3.16% |

| Log mean pressure-square-root difference (Pa0.5) | 230.271 | 234.05 | 1.64% |

| Global apparent hydrogen permeance (mol/m2.s.Pa0.5) | 6.8849 × 10–4 | 6.7732 × 10–4 | 1.62% |

| Efficiency factor (%) | 67.09% | 66.00% | 1.62% |

| Hydrogen recovery (%) | 95.000% | 94.991% | 0.01% |

| Extreme case | Temperature | Absolute retentate pressure | Absolute permeate pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 800 °C (1,472.00 °F) | 40.0 atm (587.84 psia) | 20.0 atm (293.92 psia) |

| 2 | 300 °C (572.00 °F) | 120.0 atm (1,763.5 psia) | 20.0 atm (293.92 psia) |

| 3 | 300 °C (572.00 °F) | 40.0 atm (587.84 psia) | 0.20 atm (2.9392 psia) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).