Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

- (b)

- is dominated by a point () with respect to (MOP) if and .

- (c)

- is called a Pareto point or Pareto optimal if there is no that dominates x.

- (d)

- The set of Pareto optimal solutionsis called the Pareto set.

- (e)

- The image of the Pareto set is called the Pareto front.

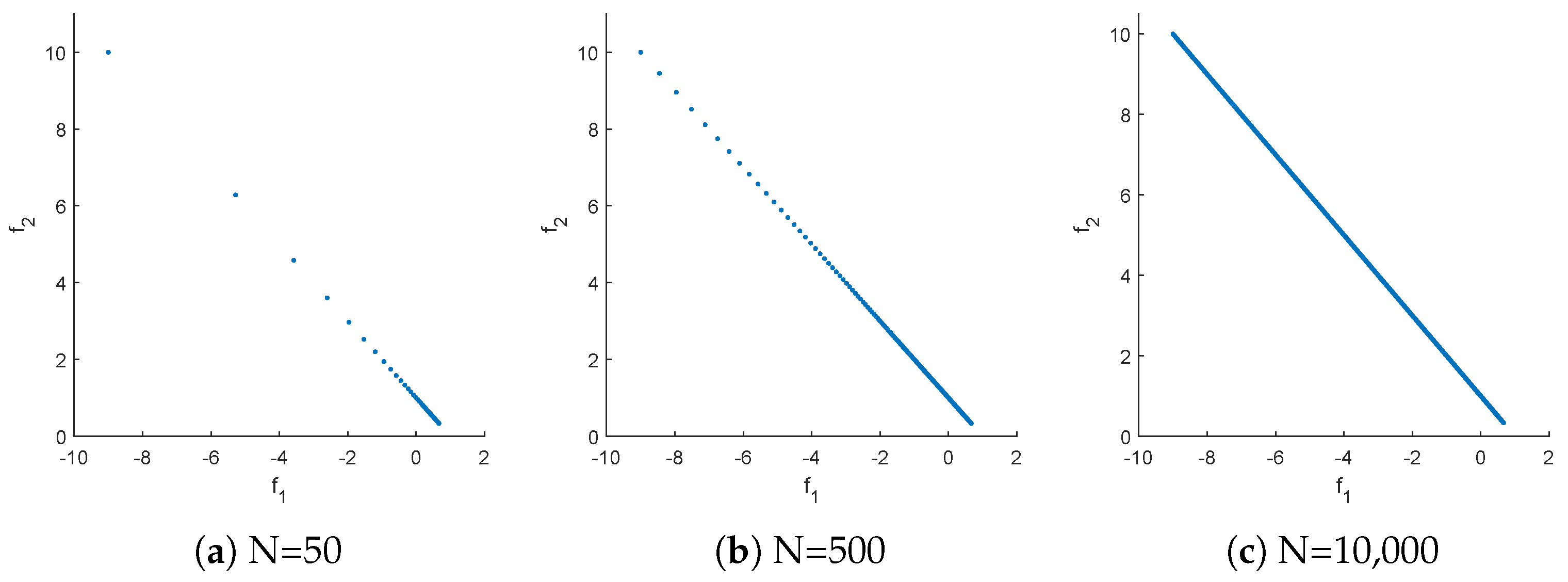

3. Reference Set Generator (RSG)

3.1. Motivation

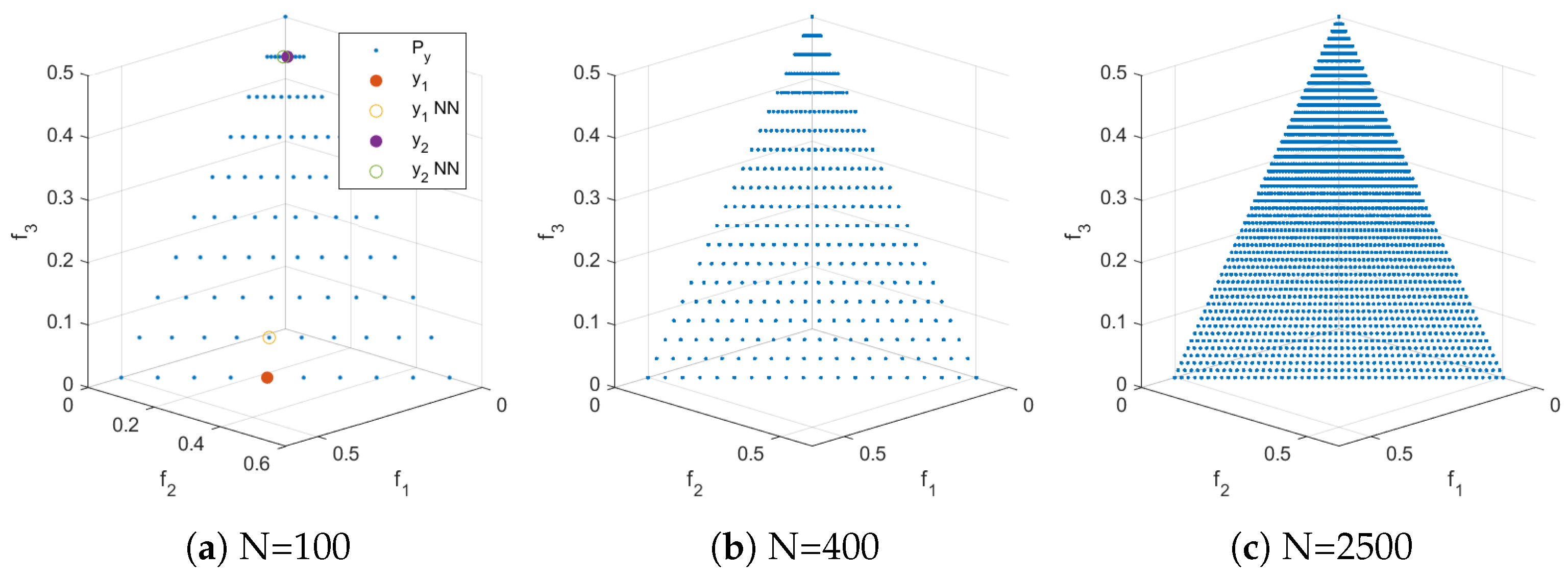

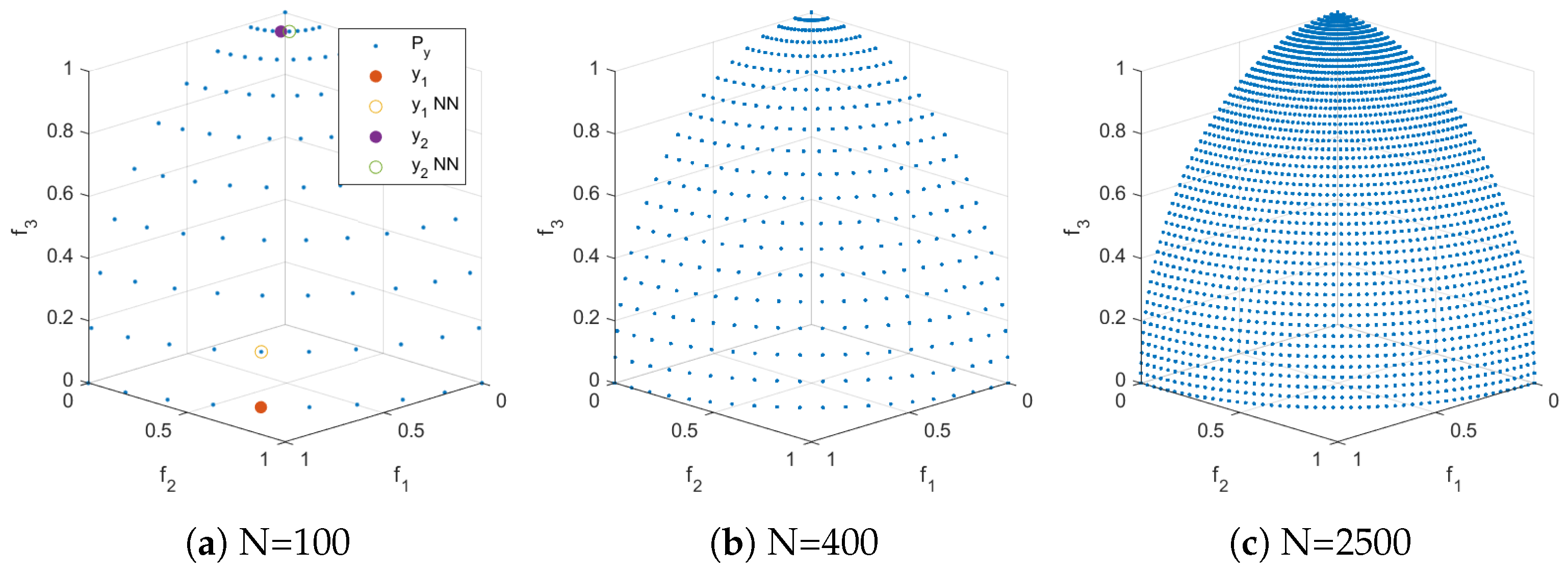

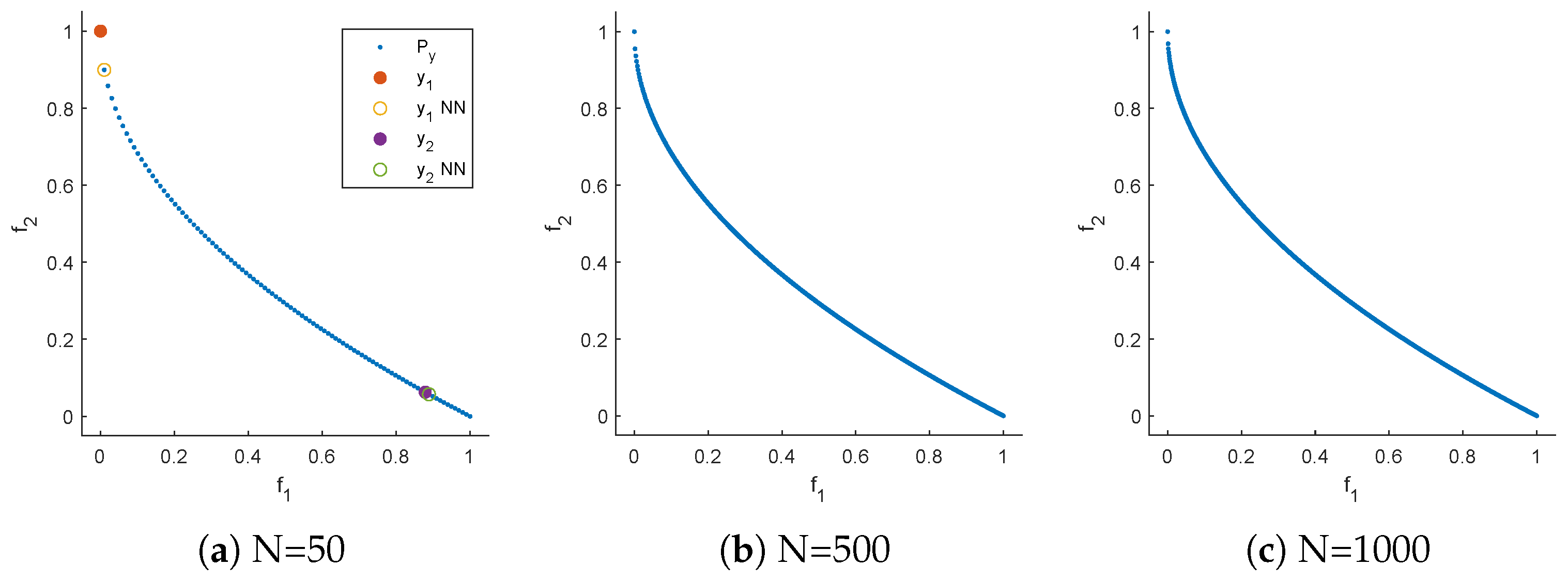

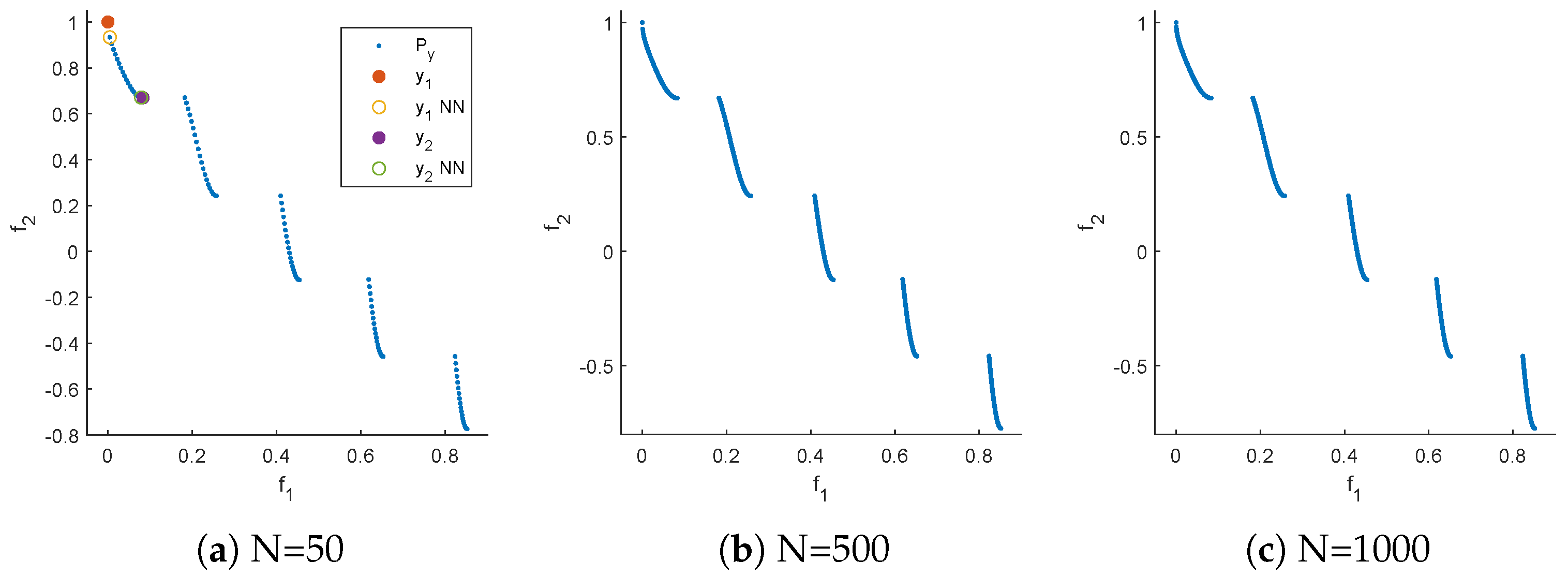

3.2. RSG

| Algorithm 1 Reference Set Generation (RSG) |

|

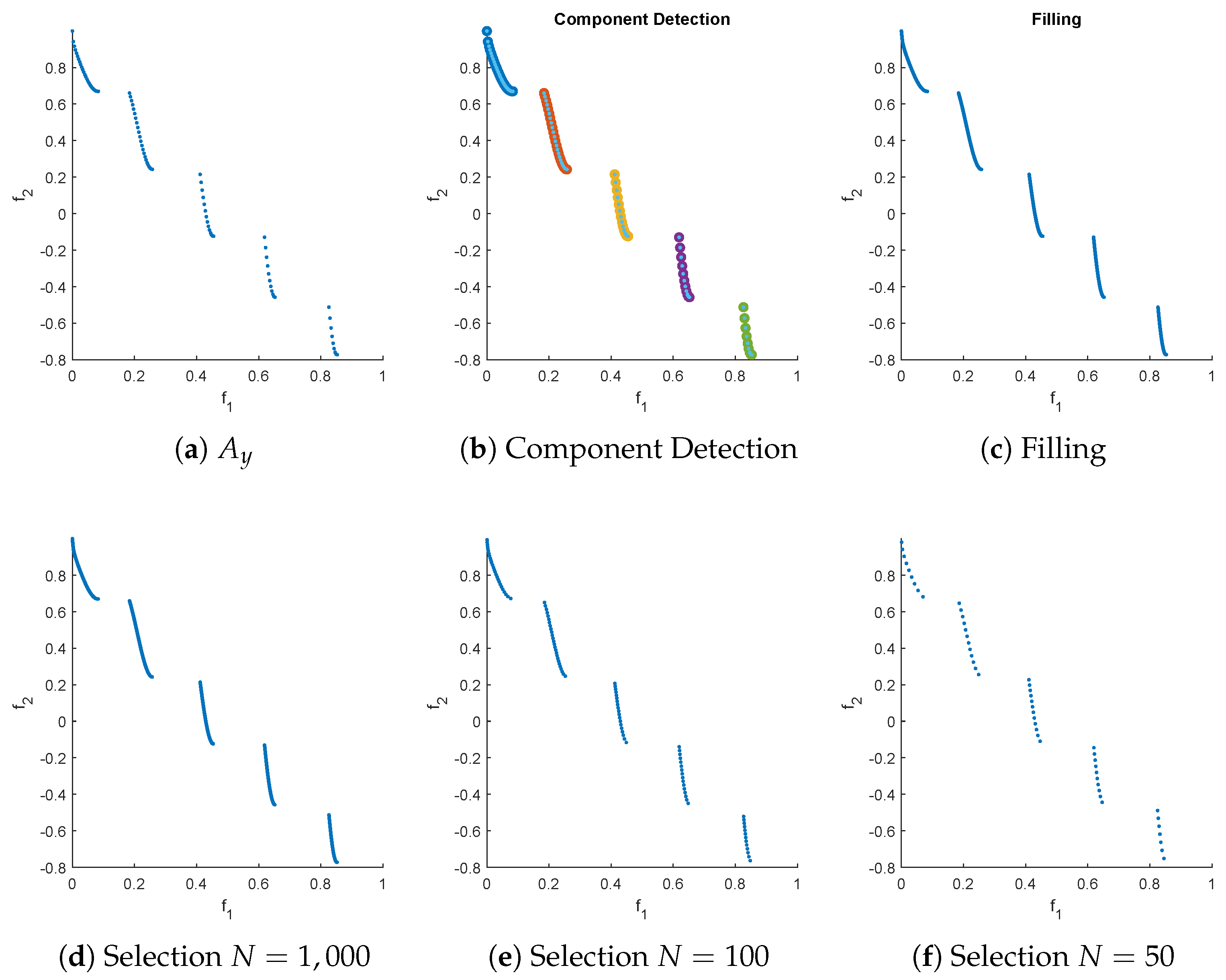

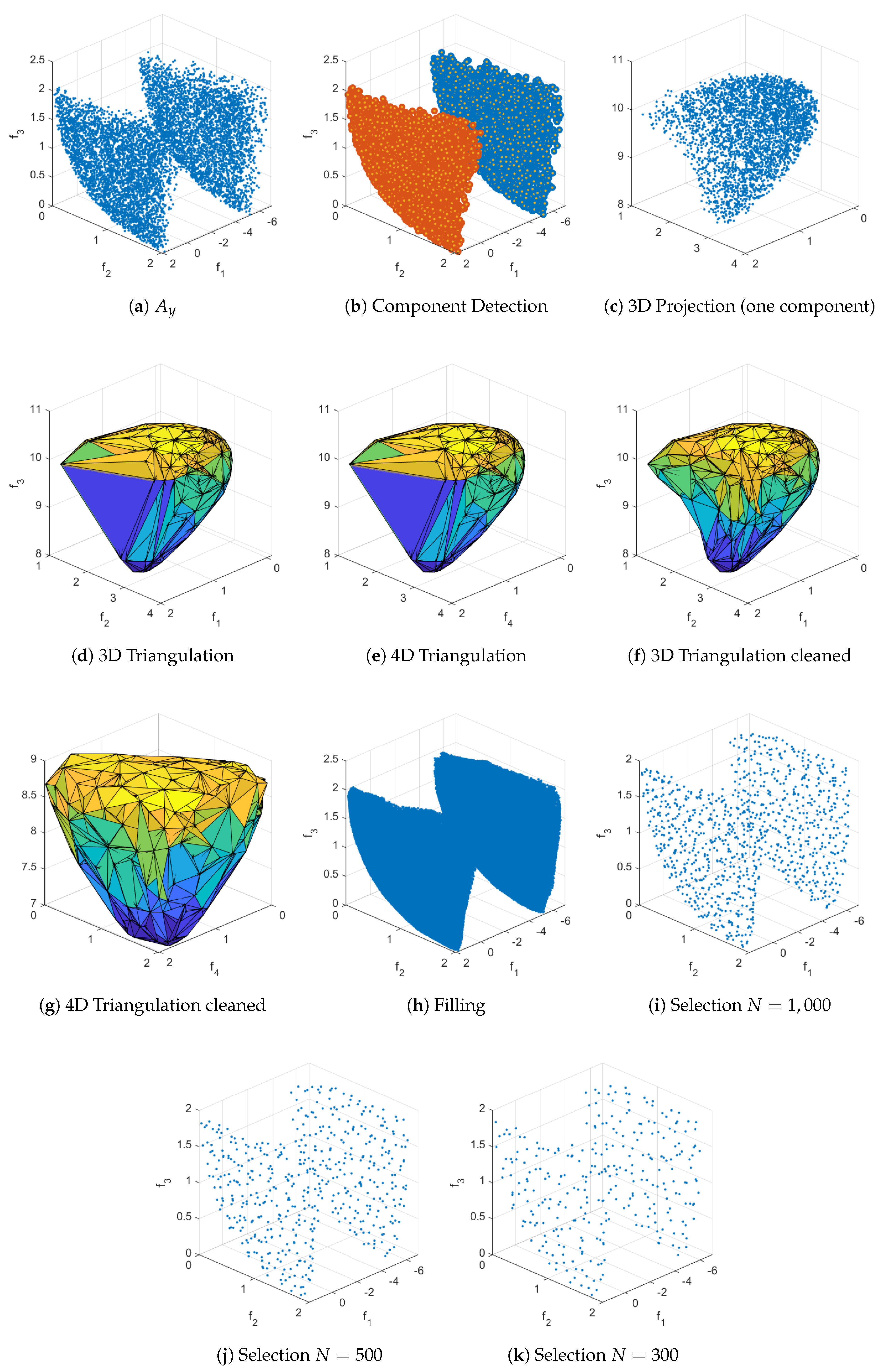

3.3. Component Detection

| Algorithm 2 Component Detection |

|

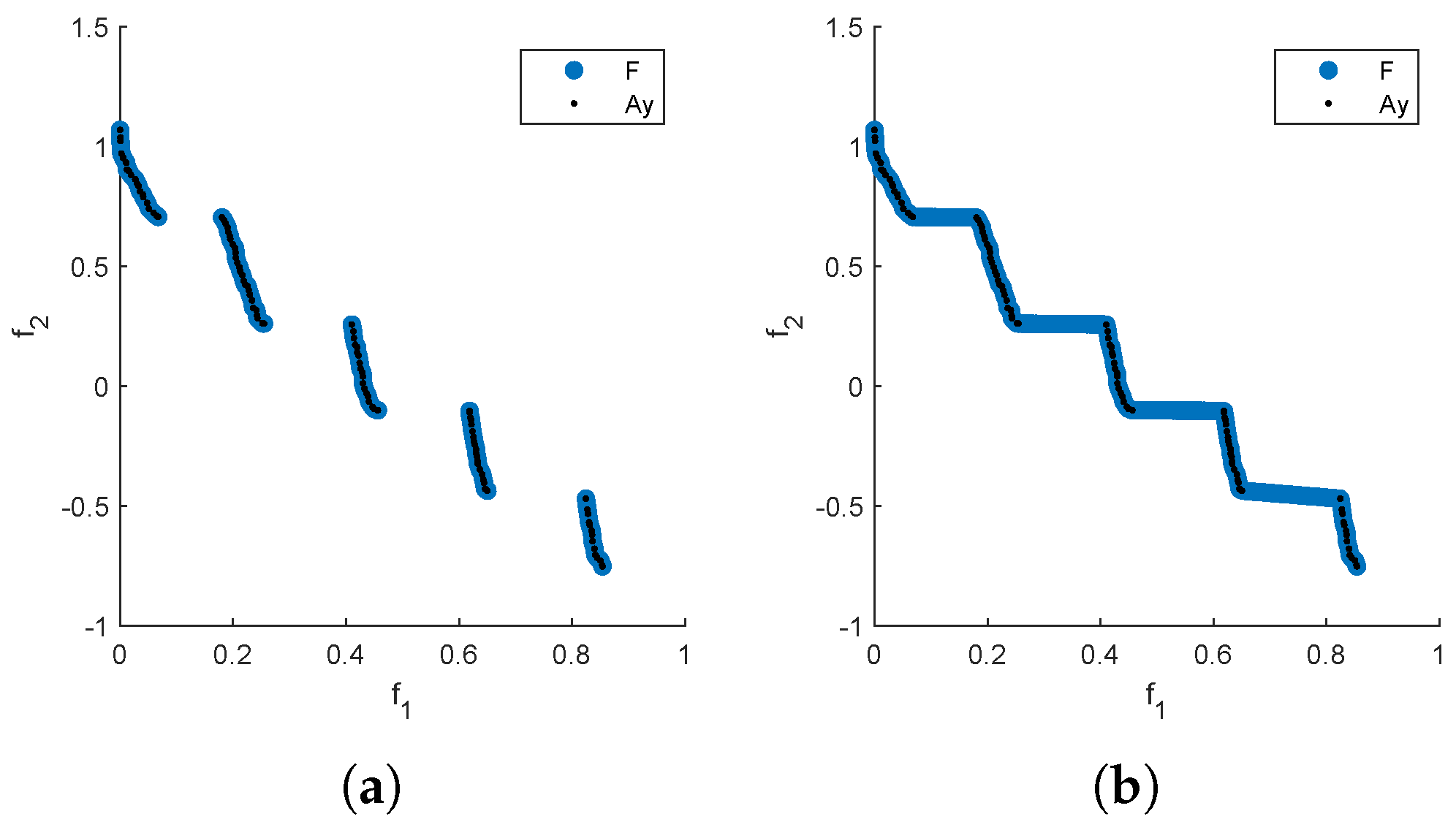

3.4. Filling

- For , we sort the points of in increasing order of , i.e., the first objective. Then, we consider the piecewise linear curve formed by the segments between and , and , and so on. The total length of this curve is given by , where . To perform the filling, we arrange the desired points along the curve L such that the first point is and the subsequent points are distributed equidistantly along L. This is achieved by placing each point at a distance of from the previous one along L. See Algorithm 3 for details.

-

The filling process for consists of several intermediate steps that must be described first; see Algorithm 4 for a general outline of the procedure. The procedure is as follows: First, to better represent (particularly for the filling step), we triangulate this set in dimensional space. This is done because the PF for continuous MOPs forms a set whose dimension is at most . To achieve this, we compute a “normal vector” to using equation 9, and then we project it onto the hyperplane normal to , obtaining the projected set . After this, we compute the Delaunay triangulation [64] of , which provides a triangulation that can be used in the original k-dimensional space. For concave PFs, the triangulation may include triangles (or simplex for ) that extend beyond (Figure 12(d)), so a removal strategy is applied to eliminate these triangles and obtain the final triangulation T. Finally, each triangle is uniformly filled at random with a number of points proportional to its area (or volume for ), resulting in the filled set F of size .We will now describe each step in more detail in the following:

- −

- Computing “normal vector” . Since the front is not known, we compute the normal direction orthogonal to the convex hull defined by the minimal elements of . More precisely, we compute as follows: if , choosewhere denotes the i-th element of , and setNext, compute a QR-factorization of M, i.e.,where is an orthogonal matrix with column vectors , and is a right upper triangular matrix. Then, the vectoris the desired shifting direction. Since Q is orthogonal, the vectors form an orthonormal basis of the hyperplane that is orthogonal to . That is, these vectors can be used for the construction of .

- −

- Projection . We use as the first axis of a new coordinate system , where the vectors are defined as above. In this coordinate system, the orthonormal vectors form the basis of a hyperplane orthogonal to . The projection of onto this hyperplane () is achieved by first expressing in this new coordinate system as , and then removing the first coordinate, yielding .

- −

- Delaunay Triangulation . Compute the Delaunay triangulation of . This returns , a list of size containing the indices of that form the triangles (or simplices for ). The list serves as the triangulation for the k-dimensional set , which is possible because consists of indices, making it independent of the dimension. We use to denote the number of triangles obtained, the indices of the vertices forming triangle i and to denote the corresponding vertices of triangle i.

- −

- Triangle Cleaning . We identify three types of unwanted triangles: those with large sides, those with large areas, and those where the matrix containing the coordinates of the vertices has a large condition number. The type of cleaning applied depends on the problem; however, the procedure remains the same for any problematic triangle case and is outlined in Algorithm 5. First, the property (area, largest side, or condition number) is computed for all the triangles . Next, triangles i with are removed. The parameter is also problem-dependent, and the specific values used for each problem will be detailed in the results section.

- −

- Triangle Filling . For each triangle with area , we generate points uniformly at random inside triangle , following the procedure described in [65]. That is, the number of points is proportional to the area (or volume) of each triangle (or simplex). Here, is the total area of the triangulation.

| Algorithm 3 Filling ( Objectives) |

|

| Algorithm 4 Filling ( Objectives) |

|

| Algorithm 5: Triangle Cleaning |

|

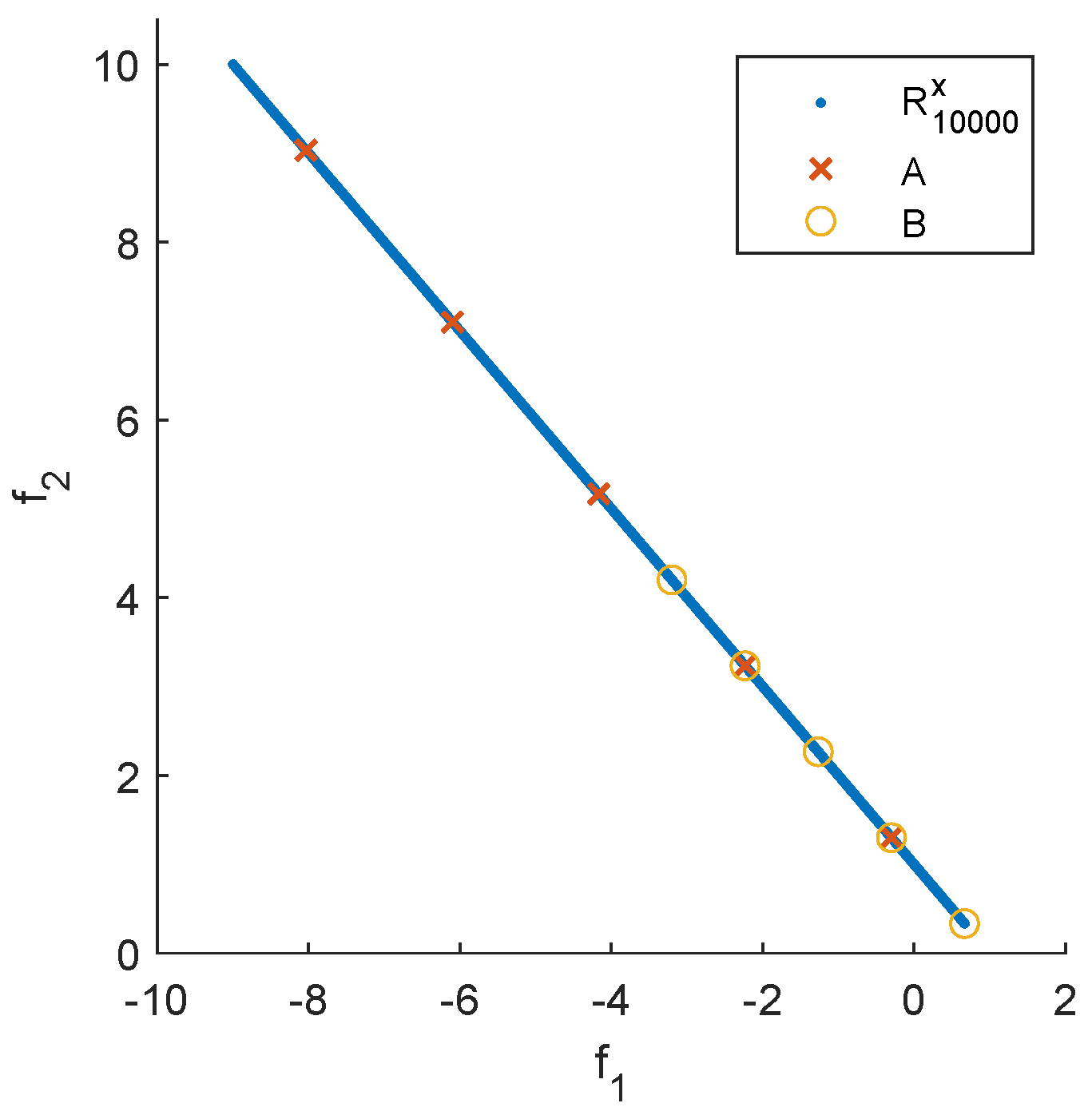

3.5. Reduction

3.6. Obtaining

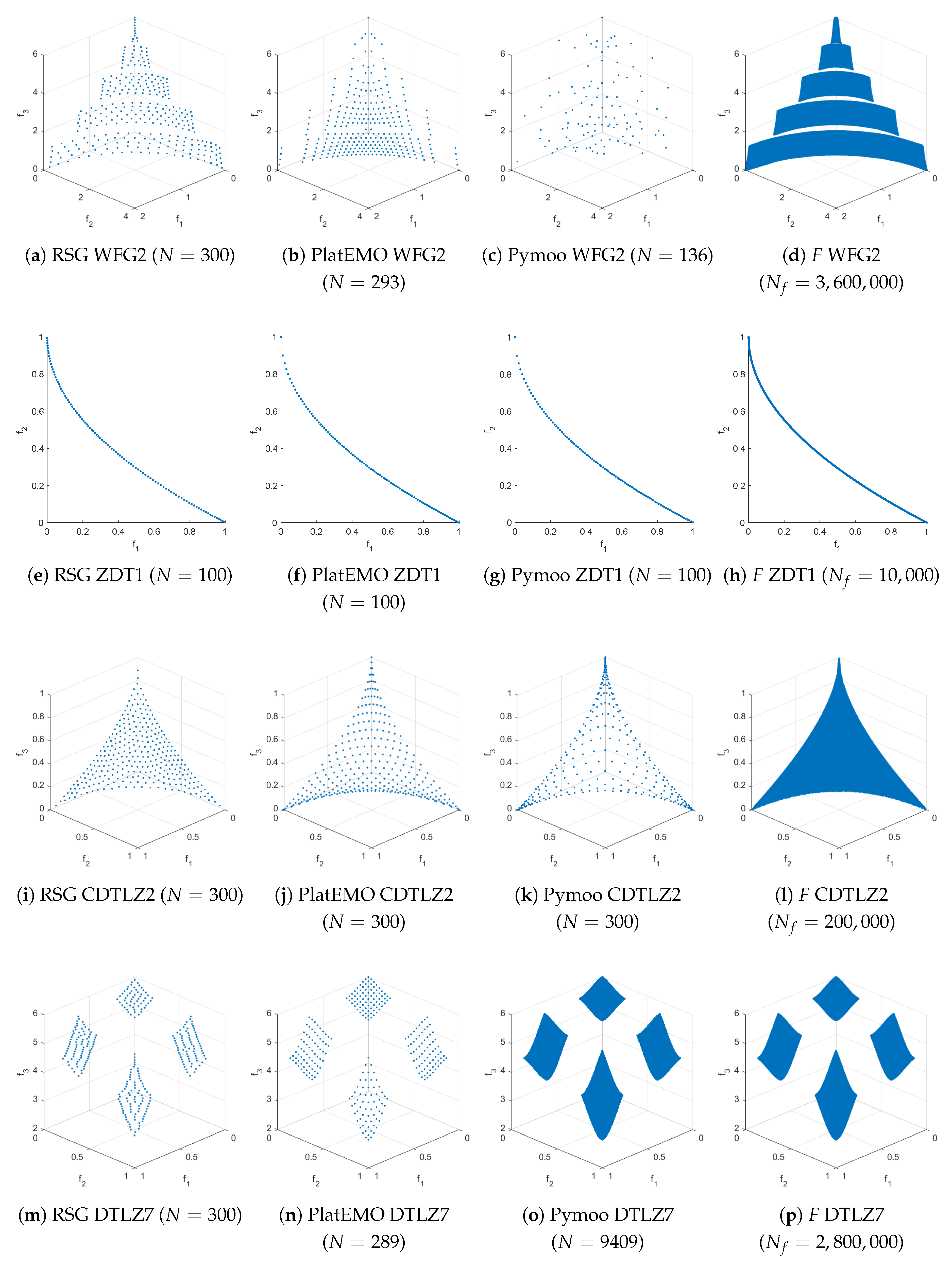

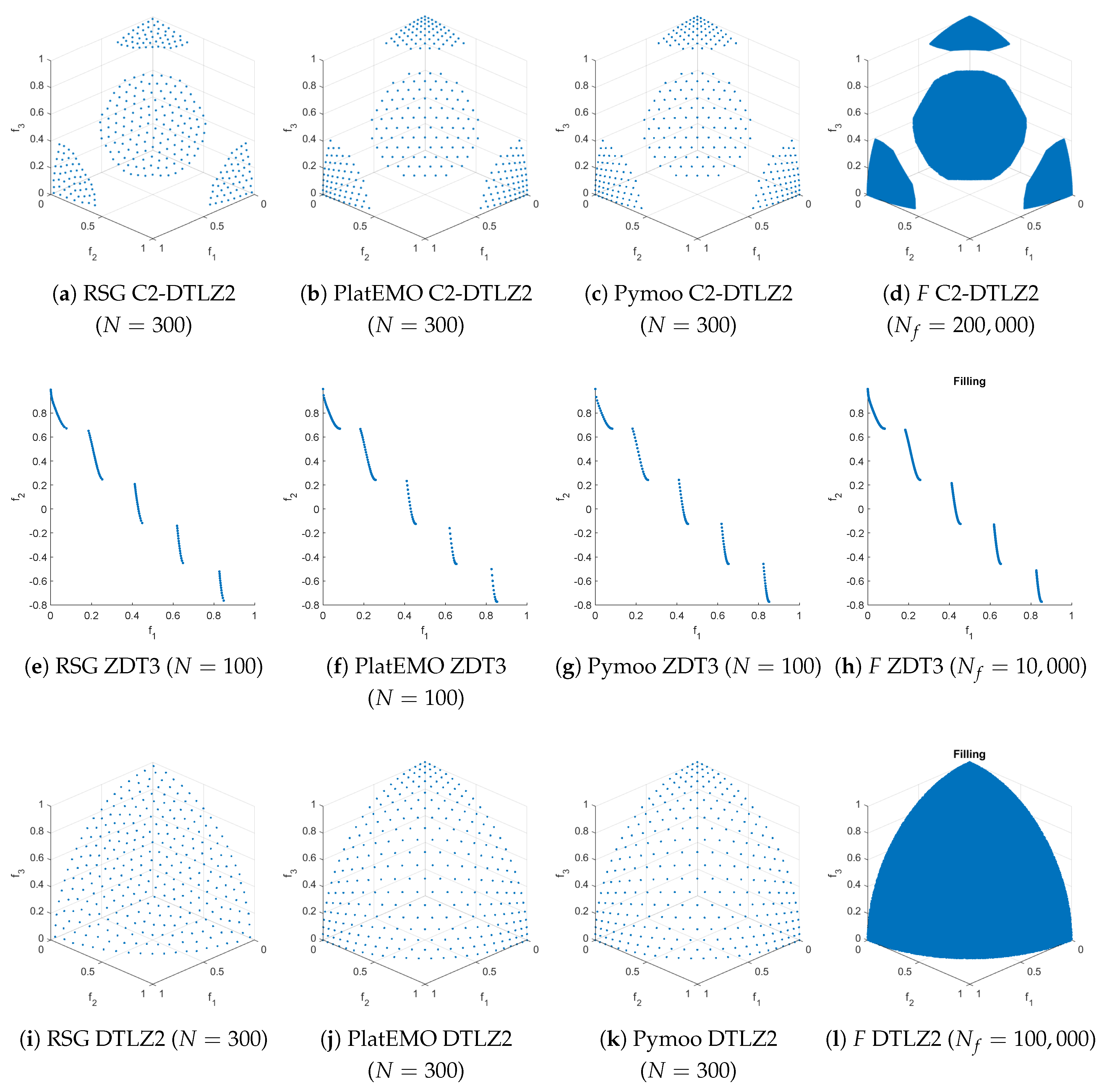

- sampling: For some benchmark problems, either the Pareto set or the Pareto front is given in analytic form. If a sampling can be performed in objective space (e.g., for linear fronts, the remaining steps of the RSG may not be needed to further improve the quality of the solution set. If the sampling is performed in decision variable space, the elements of the resulting image may not be uniformly distributed along the Pareto front as discussed above. However, in that case, the filling and reduction step will help to remove biases.

- archiving: The result of an MOEA or any other MOP solver can, of course, be taken. This could be either the final archive of the population, via merging several populations of the same or several runs ([58]), or via using external (unbounded) archives ([50]). Note that this includes taking a reference set from a given repository. We have used archiving, e.g., for the test problems WFG3-9, DTLZ1-4, DTLZ7, ZDT1-6, CONV3, CONV3-4, and CONV4-2F.

- continuation: An alternative to the above mentioned techniques is to make use of multi-objective continuation methods, probably in combination with the use of several different starting points. In particular, we have used the Pareto Tracer (PT, [68,69,70]), a state-of-the-art continuation method that is able to treat problems of in principle any dimensions (both n and k), can handle general constraints and that can even detect local degeneration of the solution set. We have used PT, e.g., for the test problem WFG1, WFG2, DTLZ5, and DTLZ6.

3.7. Complexity Analysis

- Component Detection. The time complexity is which accounts for the computation of the average distance, plus the size of the grid search () multiplied by the sum of the complexities of DBSCAN and the WeakestLink computation. Here, ℓ is the size of , and represents the number of parameter combinations of the grid search, with for and for using the default values. If it is previously known that the Pareto front is connected, then the parameters of DBSCAN can be correctly adjusted, and can be set to 1.

-

Filling. The time complexity depends on the number of objectives:

- −

- For the time complexity is , which accounts for sorting and placing the points along the line segments.

- −

- For the time complexity is due to the computations involved in determining the normal vector , changing coordinates and projecting, performing the Delaunay triangulation, and filling the triangles. Here, represents the size of the cleaned Delaunay triangulation, i.e., the number of triangles. Additionally, triangle cleaning must be considered, though its complexity depends on the method used. It is given by when cleaning is based on area or the condition number (due to determinant computation), or when cleaning based on the longest side.

- Select Reference Set T. The time complexity is due to the k-means clustering algorithm. Here, is the number of iterations of k-means.

4. Results

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Current PF approximation | |

| ℓ | Size of , the starting PF approximation |

| N | Desired size of approximation |

| Z | RSG result: Reference set of size N |

| F | Filled set |

| Size of Filling | |

| i-th detected component | |

| C | Set of all detected components |

| L | Total length of 2D curve |

| Delaunay triangulation | |

| Number of triangles in | |

| T | Cleaned Triangulation |

| Number of triangles in T | |

| Normal vector | |

| Projected | |

| Selected cleaning property (area/volume, largest side, or condition number) | |

| Value of property for triangle i | |

| Threshold for removing triangles | |

| Area/volume of triangle/simplex i | |

| A | Total area/volume of the triangulation |

| r | Radius of DBSCAN |

Appendix A Function Definitions

- CONV3

- CONV3-4

- CONV4-2F

References

- Hillermeier, C. Nonlinear Multiobjective Optimization: A Generalized Homotopy Approach; Vol. 135, Springer Science & Business Media, 2001.

- Coello Coello, C.A.; Goodman, E.; Miettinen, K.; Saxena, D.; Schütze, O.; Thiele, L. Interview: Kalyanmoy Deb Talks about Formation, Development and Challenges of the EMO Community, Important Positions in His Career, and Issues Faced Getting His Works Published. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuizen, D.A.V. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: classifications, analyses, and new innovations. Technical report, Air Force Institute of Technology, 1999.

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L.; Laumanns, M.; Fonseca, C.M.; Grunert, V.D.F. Performance assessment of multiobjective optimizers: An analysis and review. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2003, 7, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello, C.A.C.; Cruz, N.C. Solving Multiobjective Optimization Problems Using an Artificial Immune System. Genetic Programming and Evolvable Machines 2005, 6, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Esquivel, X.; Lara, A.; Coello Coello, C.A. Using the averaged Hausdorff distance as a performance measure in evolutionary multi-objective optimization. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2012, 16, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibuchi, H.; Masuda, H.; Nojima, Y. A Study on Performance Evaluation Ability of a Modified Inverted Generational Distance Indicator, New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 695–702. [CrossRef]

- Bogoya, J.M.; Vargas, A.; Cuate, O.; Schütze, O. A (p,q)-Averaged Hausdorff Distance for Arbitrary Measurable Sets. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Ehrgott, M. On Generalized Dominance Structures for Multi-Objective Optimization. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Sameer, S.A.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. Evolutionary Computation, IEEE Transactions on 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Laumanns, M.; Thiele, L. SPEA2: Improving the Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm for Multiobjective Optimization. In Proceedings of the Evolutionary Methods for Design, Optimisation and Control with Application to Industrial Problems (EUROGEN 2001); Giannakoglou, K.; et al., Eds. International Center for Numerical Methods in Engineering (CIMNE), 2002, pp. 95–100.

- Fonseca, C.M.; Fleming, P.J. An overview of evolutionary algorithms in multiobjective optimization. Evolutionary Computation 1995, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, J.D.; Corne, D.W. Approximating the nondominated front using the Pareto Archived Evolution Strategy. Evolutionary Computation 2000, 8, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H. MOEA/D: A Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm Based on Decomposition. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2007, 11, 712–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Jain, H. An evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm using reference-point-based nondominated sorting approach, part I: Solving problems with box constraints. Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2014, 18, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, H.; Deb, K. An Evolutionary Many-Objective Optimization Algorithm Using Reference-Point Based Nondominated Sorting Approach, Part II: Handling Constraints and Extending to an Adaptive Approach. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2014, 18, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiani, F.; Vasile, M. Multi Agent Collaborative Search based on Tchebycheff decomposition. Computational Optimization and Applications 2013, 56, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubayed, N.A.; Petrovski, A.; McCall, J. (DMOPSO)-M-2: MOPSO Based on Decomposition and Dominance with Archiving Using Crowding Distance in Objective and Solution Spaces. Evolutionary Computation 2014, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beume, N.; Naujoks, B.; Emmerich, M.T.M. SMS-EMOA: Multiobjective selection based on dominated hypervolume. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 181, 1653–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L.; Bader, J. SPAM: Set Preference Algorithm for multiobjective optimization. In Proceedings of the Parallel Problem Solving From Nature PPSN X, 2008, pp. 847–858.

- Wagner, T.; Trautmann, H. Integration of Preferences in Hypervolume-based multiobjective evolutionary algorithms by means of desirability functions. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2010, 14, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Domínguez-Medina, C.; Cruz-Cortés, N.; de la Fraga, L.G.; Sun, J.Q.; Toscano, G.; Landa, R. A scalar optimization approach for averaged Hausdorff approximations of the Pareto front. Engineering Optimization 2016, 48, 1593–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Hernández, V.A.; Schütze, O.; Wang, H.; Deutz, A.; Emmerich, M. The Set-Based Hypervolume Newton Method for Bi-Objective Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2020, 50, 2186–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.M.; Fleming, P.J. Genetic algorithms for multiobjective optimization: formulation, discussion, and generalization. In Proceedings of the 5-th International Conference on Genetic Algorithms; 1993; pp. 416 – 423.

- Srinivas, N.; Deb, K. Multiobjective optimization using nondominated sorting in genetic algorithms. Evolutionary Computation 1994, 2, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.; Nafpliotis, N.; Goldberg, D.E. A niched Pareto genetic algorithm for multiobjective optimization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the First IEEE Conference on Evolutionary Computation, IEEE World Congress on Computational Computation. IEEE Press, 1994, pp. 82 – 87.

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: A comparative case study and the strength Pareto approach. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 1999, 3, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, G. Finite Markov Chain results in evolutionary computation: A Tour d’Horizon. Fundamenta Informaticae 1998, 35, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, G. On a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm and its convergence to the Pareto set. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation (ICEC 1998). IEEE Press, 1998, pp. 511 – 516.

- Rudolph, G.; Agapie, A. Convergence Properties of Some Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms. In Proceedings of the Evolutionary Computation (CEC), 2011 IEEE Congress on. IEEE Press, 2000.

- Rudolph, G. Evolutionary Search under Partially Ordered Fitness Sets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International NAISO Congress on Information Science Innovations (ISI 2001). ICSC Academic Press, Sliedrecht, The Netherlands, 2001, pp. 818 – 822.

- Hanne, T. On the convergence of multiobjective evolutionary algorithms. European Journal of Operational Research 1999, 117, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanne, T. Global multiobjective optimization with evolutionary algorithms: Selection mechanisms and mutation control. In Proceedings of the Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization, First International Conference, EMO 2001, Zurich, Switzerland. Springer Berlin, 2001, pp. 197 – 212.

- Hanne, T. A multiobjective evolutionary algorithm for approximating the efficient set. European Journal of Operational Research 2007, 176, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanne, T. A Primal-Dual Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithm for Approximating the Efficient Set. In Proceedings of the Evolutionary Computation (CEC), 2007 IEEE Congress on. IEEE Press, 2007, pp. 3127 – 3134.

- Brockhoff, D.; Tran, T.D.; Hansen, N. Benchmarking numerical multiobjective optimizers revisited. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation, 2015, pp. 639–646.

- Wang, R.; Zhou, Z.; Ishibuchi, H.; Liao, T.; Zhang, T. Localized weighted sum method for many-objective optimization. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2016, 22, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.M.; Ishibuchi, H.; Shang, K. Algorithm Configurations of MOEA/D with an Unbounded External Archive. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.13352 2020.

- Nan, Y.; Shu, T.; Ishibuchi, H. Effects of External Archives on the Performance of Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms on Real-World Problems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), 2023, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, A.E.; Schäpermeier, L.; Hernández, C.; Kerschke, P.; Trautmann, H.; Schütze, O. Finding ϵ-Locally Optimal Solutions for Multi-Objective Multimodal Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2024, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, A.E.; Segura, C.; Hernández, C. Finding the Set of Nearly Optimal Solutions of a Multi-Objective Optimization Problem. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, Y.; Ishibuchi, H.; Pang, L.M. Small Population Size is Enough in Many Cases with External Archives. In Proceedings of the Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization; et al., H.S., Ed. Springer Nature Singapore, 2025, pp. 99–113.

- Author, P. Placehodler Title. Journal of Placeholder 1984, 42, 4200. [Google Scholar]

- Laumanns, M.; Thiele, L.; Deb, K.; Zitzler, E. Combining convergence and diversity in evolutionary multiobjective optimization. Evolutionary Computation 2002, 10, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütze, O.; Laumanns, M.; Coello Coello, C.A.; Dellnitz, M.; Talbi, E.G. Convergence of Stochastic Search Algorithms to Finite Size Pareto Set Approximations. Journal of Global Optimization 2008, 41, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Laumanns, M.; Tantar, E.; Coello Coello, C.A.; Talbi, E.G. Computing gap free Pareto front approximations with stochastic search algorithms. Evolutionary Computation 2010, 18, 65–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Lara, A.; Coello, C.A.C.; Vasile, M. On the Detection of Nearly Optimal Solutions in the Context of Single-Objective Space Mission Design Problems. Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2011, 225, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Vasile, M.; Coello, C.A.C. Computing the Set of Epsilon-Efficient Solutions in Multiobjective Space Mission Design. Journal of Aerospace Computing, Information, and Communication 2011, 8, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Hernández, C.; Talbi, E.G.; Sun, J.Q.; Naranjani, Y.; Xiong, F.R. Archivers for the Representation of the Set of Approximate Solutions for MOPs. Journal of Heuristics 2019, 5, 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Hernández, C. Archiving Strategies for Evolutionary Multi-objective Optimization Algorithms; Springer, 2021.

- Knowles, J.D.; Corne, D.W. Properties of an adaptive archiving algorithm for storing nondominated vectors. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2003, 7, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, J.D.; Corne, D.W. Bounded Pareto archiving: Theory and practice. In Proceedings of the Metaheuristics for Multiobjective Optimisation. Springer, 2004, pp. 39 – 64.

- Knowles, J.D.; Corne, D.W.; Fleischer, M. Bounded archiving using the Lebesgue measure. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation. IEEE Press, 2003, pp. 2490 – 2497.

- López-Ibáñez, M.; Knowles, J.D.; Laumanns, M. On Sequential Online Archiving of Objective Vectors. In Proceedings of the Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization (EMO 2011). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011, pp. 46 – 60.

- Laumanns, M.; Zenklusen, R. Stochastic convergence of random search methods to fixed size Pareto front approximations. European Journal of Operational Research 2011, 213, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, R.; Jin, Y. Sampling Reference Points on the Pareto Fronts of Benchmark Multi-Objective Optimization Problems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), 2018, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Y. PlatEMO: A MATLAB platform for evolutionary multi-objective optimization. IEEE Computational Intelligence Magazine 2017, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, A.E.; Uribe, L.; Deutz, A.; na, O.C.P.; Schütze, O. A Newton Method for Hausdorff Approximations of the Pareto Front Within Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2024, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Bogoya, J.M.; Vargas, A.; Schütze, O. The Averaged Hausdorff Distances in Multi-Objective Optimization: A Review. Mathematics 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, G.; Schütze, O.; Grimme, C.; Domínguez-Medina, C.; Trautmann, H. Optimal averaged Hausdorff archives for bi-objective problems: Theoretical and numerical results. Comput Optim Appl 2016, 64, 589–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilettoso, E.; Rizzo, S.A.; Salerno, N. A Weakly Pareto Compliant Quality Indicator. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the KDD; et al., E.S., Ed. AAAI Press, 1996, pp. 226–231.

- Ben-David, S.; Ackerman, M. Measures of Clustering Quality: A Working Set of Axioms for Clustering. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; et al., D.K., Ed. Curran Associates, Inc., 2008, Vol. 21.

- Delaunay, B. Sur la sphère vide. Bulletin de l’Acadeémie des Sciences de l’URSS. Classe des sciences mathématiques et na 1934, 1934, 793–800. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.A.; Tromble, R.W. Sampling uniformly from the unit simplex 2004.

- Uribe, L.; Bogoya, J.M.; Vargas, A.; Lara, A.; Rudolph, G.; Schütze, O. A Set Based Newton Method for the Averaged Hausdorff Distance for Multi-Objective Reference Set Problems. Mathematics 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ishibuchi, H.; Shang, K. Clustering-Based Subset Selection in Evolutionary Multiobjective Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, 2021, and Cybernetics (SMC); pp. 468–475. [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.; Schütze, O. Pareto Tracer: A predictor-corrector method for multi-objective optimization problems. Engineering Optimization 2018, 50, 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, F.; Cuate, O.; Schütze, O. The Pareto Tracer for General Inequality Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization Problems. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, O.; Cuate, O. The Pareto Tracer for the treatment of degenerated multi-objective optimization problems. Engineering Optimization 2024, pp. 1–26.

| 0.5118 | 0.7384 | 0.9084 | 0.9873 | 0.6423 | 0.9084 | 0.9873 | 1.3671 | |

| 0.0698 | 0.1002 | 0.4522 | 1.0744 | 0.3198 | 0.4522 | 1.0744 | 8.2024 | |

| 0.0684 | 0.0684 | 0.6835 | 0.7883 | 0.4833 | 0.6835 | 0.7883 | 1.2987 | |

| 0.0684 | 0.0684 | 2.5974 | 3.6765 | 1.8367 | 2.5974 | 3.6765 | 8.1341 | |

| 0.0028 | 0.0032 | 0.8968 | 0.9776 | 0.6341 | 0.8968 | 0.9776 | 1.3671 | |

| 0.0008 | 0.0010 | 0.4117 | 0.8792 | 0.2911 | 0.4117 | 0.8792 | 8.2024 | |

| 0.0007 | 0.0007 | 0.6835 | 0.7893 | 0.4833 | 0.6835 | 0.7893 | 1.3664 | |

| 0.0007 | 0.0007 | 2.5974 | 3.6767 | 1.8367 | 2.5974 | 3.6767 | 8.2018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).